Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 24, Issue 4

- Understanding and interpreting regression analysis

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7839-8130 Parveen Ali 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0157-5319 Ahtisham Younas 3 , 4

- 1 School of Nursing and Midwifery , University of Sheffield , Sheffield , South Yorkshire , UK

- 2 Sheffiled University Interpersonal Violence Research Group , The University of Sheffiled SEAS , Sheffield , UK

- 3 Faculty of Nursing , Memorial University of Newfoundland , St. John's , Newfoundland and Labrador , Canada

- 4 Swat College of Nursing , Mingora, Swat , Pakistan

- Correspondence to Ahtisham Younas, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL A1C 5S7, Canada; ay6133{at}mun.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2021-103425

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- statistics & research methods

Introduction

A nurse educator is interested in finding out the academic and non-academic predictors of success in nursing students. Given the complexity of educational and clinical learning environments, demographic, clinical and academic factors (age, gender, previous educational training, personal stressors, learning demands, motivation, assignment workload, etc) influencing nursing students’ success, she was able to list various potential factors contributing towards success relatively easily. Nevertheless, not all of the identified factors will be plausible predictors of increased success. Therefore, she could use a powerful statistical procedure called regression analysis to identify whether the likelihood of increased success is influenced by factors such as age, stressors, learning demands, motivation and education.

What is regression?

Purposes of regression analysis.

Regression analysis has four primary purposes: description, estimation, prediction and control. 1 , 2 By description, regression can explain the relationship between dependent and independent variables. Estimation means that by using the observed values of independent variables, the value of dependent variable can be estimated. 2 Regression analysis can be useful for predicting the outcomes and changes in dependent variables based on the relationships of dependent and independent variables. Finally, regression enables in controlling the effect of one or more independent variables while investigating the relationship of one independent variable with the dependent variable. 1

Types of regression analyses

There are commonly three types of regression analyses, namely, linear, logistic and multiple regression. The differences among these types are outlined in table 1 in terms of their purpose, nature of dependent and independent variables, underlying assumptions, and nature of curve. 1 , 3 However, more detailed discussion for linear regression is presented as follows.

- View inline

Comparison of linear, logistic and multiple regression

Linear regression and interpretation

Linear regression analysis involves examining the relationship between one independent and dependent variable. Statistically, the relationship between one independent variable (x) and a dependent variable (y) is expressed as: y= β 0 + β 1 x+ε. In this equation, β 0 is the y intercept and refers to the estimated value of y when x is equal to 0. The coefficient β 1 is the regression coefficient and denotes that the estimated increase in the dependent variable for every unit increase in the independent variable. The symbol ε is a random error component and signifies imprecision of regression indicating that, in actual practice, the independent variables are cannot perfectly predict the change in any dependent variable. 1 Multiple linear regression follows the same logic as univariate linear regression except (a) multiple regression, there are more than one independent variable and (b) there should be non-collinearity among the independent variables.

Factors affecting regression

Linear and multiple regression analyses are affected by factors, namely, sample size, missing data and the nature of sample. 2

Small sample size may only demonstrate connections among variables with strong relationship. Therefore, sample size must be chosen based on the number of independent variables and expect strength of relationship.

Many missing values in the data set may affect the sample size. Therefore, all the missing values should be adequately dealt with before conducting regression analyses.

The subsamples within the larger sample may mask the actual effect of independent and dependent variables. Therefore, if subsamples are predefined, a regression within the sample could be used to detect true relationships. Otherwise, the analysis should be undertaken on the whole sample.

Building on her research interest mentioned in the beginning, let us consider a study by Ali and Naylor. 4 They were interested in identifying the academic and non-academic factors which predict the academic success of nursing diploma students. This purpose is consistent with one of the above-mentioned purposes of regression analysis (ie, prediction). Ali and Naylor’s chosen academic independent variables were preadmission qualification, previous academic performance and school type and the non-academic variables were age, gender, marital status and time gap. To achieve their purpose, they collected data from 628 nursing students between the age range of 15–34 years. They used both linear and multiple regression analyses to identify the predictors of student success. For analysis, they examined the relationship of academic and non-academic variables across different years of study and noted that academic factors accounted for 36.6%, 44.3% and 50.4% variability in academic success of students in year 1, year 2 and year 3, respectively. 4

Ali and Naylor presented the relationship among these variables using scatter plots, which are commonly used graphs for data display in regression analysis—see examples of various scatter plots in figure 1 . 4 In a scatter plot, the clustering of the dots denoted the strength of relationship, whereas the direction indicates the nature of relationships among variables as positive (ie, increase in one variable results in an increase in the other) and negative (ie, increase in one variable results in decrease in the other).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

An Example of Scatter Plot for Regression.

Table 2 presents the results of regression analysis for academic and non-academic variables for year 4 students’ success. The significant predictors of student success are denoted with a significant p value. For every, significant predictor, the beta value indicates the percentage increase in students’ academic success with one unit increase in the variable.

Regression model for the final year students (N=343)

Conclusions

Regression analysis is a powerful and useful statistical procedure with many implications for nursing research. It enables researchers to describe, predict and estimate the relationships and draw plausible conclusions about the interrelated variables in relation to any studied phenomena. Regression also allows for controlling one or more variables when researchers are interested in examining the relationship among specific variables. Some of the key considerations are presented that may be useful for researchers undertaking regression analysis. While planning and conducting regression analysis, researchers should consider the type and number of dependent and independent variables as well as the nature and size of sample. Choosing a wrong type of regression analysis with small sample may result in erroneous conclusions about the studied phenomenon.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not required.

- Montgomery DC ,

- Schneider A ,

Twitter @parveenazamali, @@Ahtisham04

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Update librarian

Key Features

New features.

The combination from theory and applied exercises with detailed answers is very helpfull to support students transferring knwoledge in to practice

This is a well organised and provides undergraduate students with a clear understanding of statistics.

An excellent resource in statistics in health and social sciences which is also useful in physiotherapy studies; easy to read and follow and will highly recommend to students, educators and academics.

Good text for understanding statistics

Thank you. very essential

I think this book cover most of statistical subjects.

En la Facultad de Medicina Veracruz de la Universidad Veracruzana llevamos la EE Estadística por lo cual requiero revisar el libro para ver si reúne las características para se llevado al curso Agradezco el envío

Gives very good grounding in stats for year 4 and MSc students

Great for research students

Exactly what I need

Please verify your email.

We've sent you an email. Please follow the link to reset your password.

You can now close this window.

Edits have been made. Are you sure you want to exit without saving your changes?

Interpreting statistical significance in nursing research

Don’t let p values distract you from scientific reasoning..

- P values are useful to report the results of inferential statistics, but they aren’t a substitute for scientific reasoning.

- After a statistical analysis of data, the null hypothesis is either accepted or rejected based on the P value.

- Reading statistical results includes summary statistics (descriptive statistics), test statistics, and P value with other considerations such as one-tailed or two-tailed test, and sample size.

Improper interpretation of statistical analysis can lead to abuse or misuse of results. We draw valid interpretations when data meet fundamental assumptions and when we evaluate the probability of errors. Statistical analysis requires knowledge for proper interpretation, which relies on considering the null hypothesis, two-tailed or one-tailed tests, study power, type I and type II errors, and statistical vs. clinical significance. In many domains, including nursing, statistical significance ( P value) serves as an important threshold for interpretation, whether the result is statistically significant or not. However, statistical significance frequently is misunderstood and misused.

Statistical test components

In empirical research, all statistical tests begin with the null hypothesis and end with a test statistic and the associated statistical significance. A test of statistical significance determines the likelihood of a result assuming a null hypothesis to be true. Depending on the selected statistical analysis, researchers will use Z scores, t tests, or F tests. Although three methods exist for testing hypotheses (confidence intervals [CIs], P values, and critical values), essentially the P value serves as the significance level. Many researchers consider P values the most important summary of an inferential statistical analysis.

Null hypothesis

Before conducting a study, researchers propose a null hypothesis, which begins with an initial idea they want to demonstrate. It guides the statistical analysis and predicts the direction and nature of study results. Traditionally, a null hypothesis proposes no difference between two variables being studied or the characteristics of a population. An alternative hypothesis states a result that’s either not equal to, greater than, or less than the null hypothesis.

Two-tailed test vs. one-tailed test

Researchers commonly check a null hypothesis or statistical significance using a two-tailed test, which postulates that the sample mean is equal or unequal to the population. A one-tailed test postulates that the sample mean is higher or lower than the population mean. Nursing researchers rarely use a one-tailed test because of the consequences of missing an effect. (See Different distribution results .)

Study power and type I/type II errors

The possibility of error exists when testing a hypothesis. Type I errors (false alarms) occur when we reject a null hypothesis that’s true. Type II errors (misses) occur when we accept a null hypothesis that’s false. Sample size can influence the power of the study. For example, even small treatment effects can appear statistically significant in a large sample.

The alpha (α)—the probability of a type I error—refers to the likelihood that the truth lies outside the confidence interval (CI). The smaller the α, the smaller the area where we would reject the null hypothesis, which reduces the chance that will occur. The most widely acceptable α cutoff in nursing research is 0.05. Keep in mind that the confidence level and α are analogous. If the α=0.05, the confidence level is 95%. If α=0.01, the confidence level is 99%.

Confidence interval

A CI provides an idea of the range within which a value might occur by chance. It indicates the strength of the estimate by providing a range of uncertainty. Frequently, researchers use CIs without a dichotomous result of the P value. Consider the following example: On a scale between 0 and 10, patients with an advanced illness reported an average pain score of between 4.1 and 6.3 (95% CI: 4.1 to 6.3). With a 95% CI, researchers risk being wrong 5 out of 100 times.

Statistical vs. clinical significance

Statistical significance indicates the study results’ confidence in probability, while the clinical significance reflects its impact on clinical practice. Measures of statistical significance quantify the probability that a study result is due to chance rather than a real treatment effect. On the other hand, clinical significance indicates the magnitude of the actual treatment effect or impact in nursing practice.

Consider this example: Researchers compare two groups (exercise group and diet group). The mean body weight of subjects after treatment with exercise is 1 pound lower than after treatment with diet. The difference between these groups could be statistically significant, with a P value of <0.05. However, the clinical implications of a 1 pound weight loss wouldn’t be clinically significant. In this example, the mean weight—172 pounds (exercise group) vs. 173 pounds (diet group), P =0.04—is statistically significant . The 0.04 P value means only a 4% chance exists that this observed weight difference occurred randomly. However, the clinical significance of a 1 pound difference between the groups would be considered small and not clinically significant.

The results section of a quantitative research study report includes names of statistical tests, the value of the calculated statistics, and the statistical significance ( P value). After a statistical analysis of data, the null hypothesis is either accepted or rejected based on the P value. For example, if a report indicates a significant finding at the 0.05 probability level (α=0.05), the findings might have an error 5% of the time (only 5 out of 100) and a 95% confidence that the results aren’t erroneous after repeated testing. (See P value examples.)

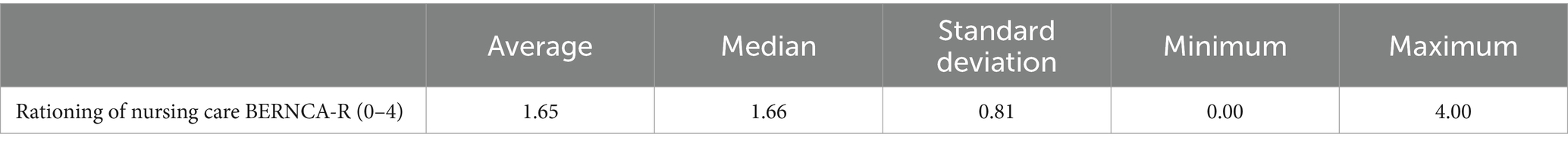

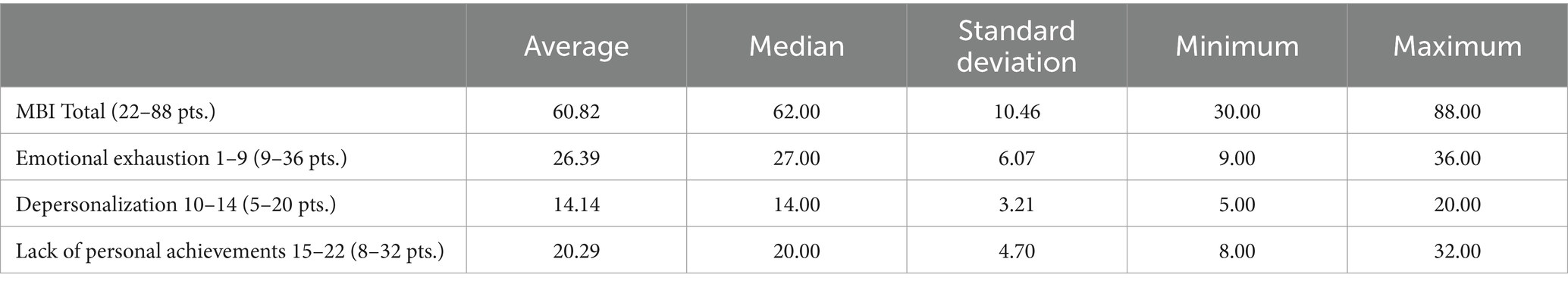

Study example: Reading results and tables

Use the mean to understand the center of the data. Most statistical analyses use the mean and/or median for a central tendency. Also, use the standard deviation (SD) to understand how widely spread the data are from the mean. As shown in Table 2, the mean of pre-intervention pain is 7.2, while the mean of post-intervention pain is 4.6. The SD in pre-intervention pain is 1.4, and the SD in post-intervention pain is 1.8. A higher SD value indicates a greater spread in the data.

Table 2—The mean and SD of pre- and post-intervention pain for 30 patients

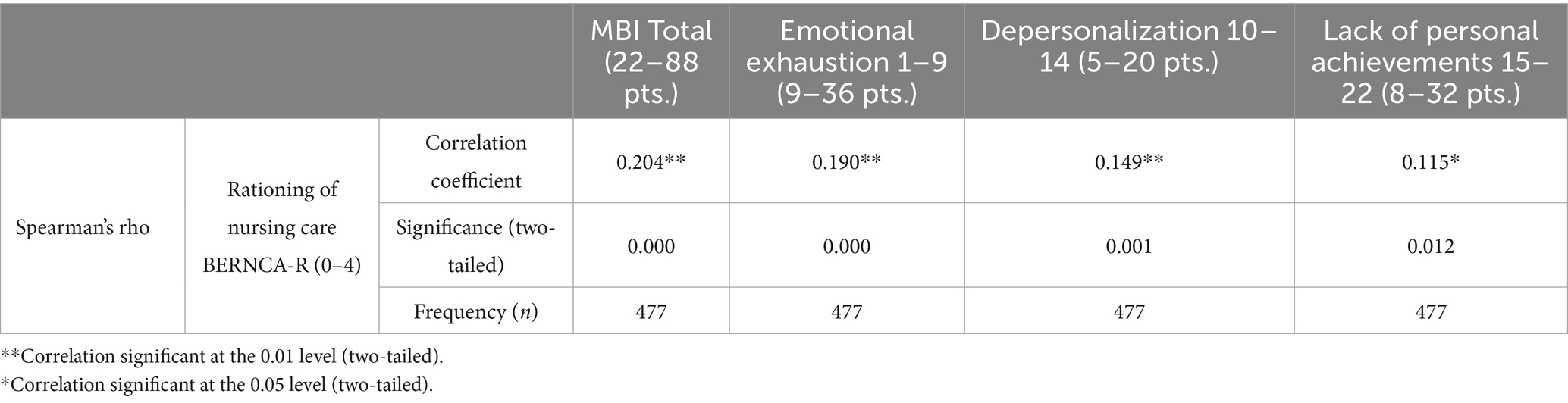

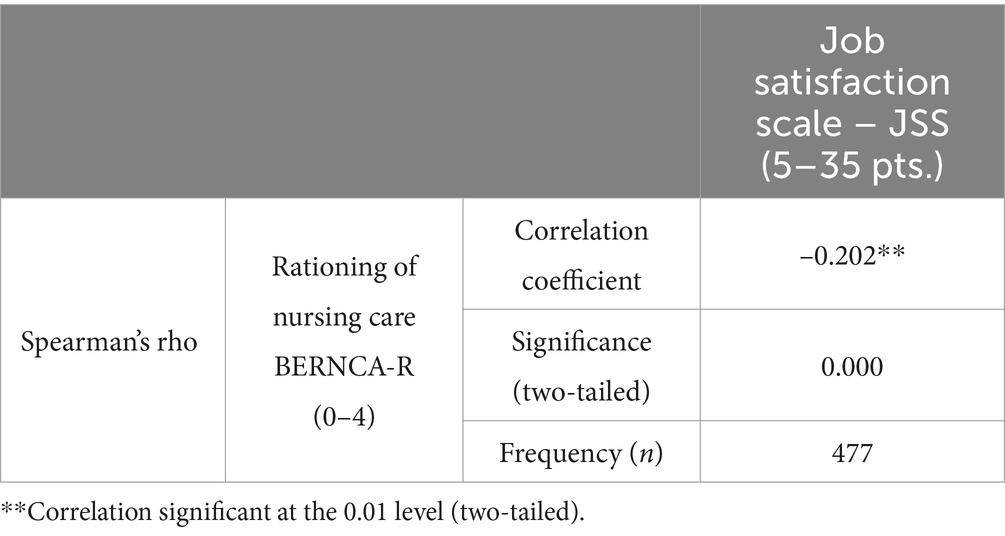

Table 3 shows a mean difference between pre- and post-intervention pain of 2.5667. Based on the t-test results, the t score is 7.92. The confidence interval (CI) is 95% for the mean difference, with pre- and post-intervention pain scores ranging from 1.41 to 2.39.

Table 3—Paired samples t-test of change score

95% CI of the difference

Next, find the associated P values

- If P <α (0.05), reject the H 0 and accept the H α .

- If P >α (0.05), accept the H 0 .

In this example, P <0.001, which means the Ho can be rejected. We accept the H α that the mean post-intervention pain score is significantly different from the mean pre-intervention pain score.

Interpreting statistical results

Reading and interpreting statistical results includes summary statistics (descriptive statistics), test statistics, and P value with other considerations such as one-tailed or two-tailed test, sample size, and multiple comparisons. We must not only understand the decision to accept or reject a hypothesis based on a test used, but also understand the descriptive statistics and other considerations such as normality and equal variance. For complex statistics, tables provide the most effective way to view the results.

Rely on scientific reasoning

Quantitative nursing research uses a testing hypothesis in decision making. P values are useful for reporting the results of inferential statistics, but we must be aware of their limitations. The P value isn’t the probability that the null hypothesis is true but the probability of the test statistics against a null hypothesis. It measures the compatibility of data with the null hypothesis but can’t reveal whether an alternative hypothesis is true. Also keep in mind that the 0.05 significance level is merely a convention. Researchers commonly use it as a threshold whether it’s statistically significant or not.

P values were never intended as a substitute for scientific reasoning. All results should be interpreted in the context of the research design (sample size, measurement validity or reliability, and study design rigor).

Joohyun Chung is a biostatistician and assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Elaine Marieb College of Nursing in Amherst.

American Nurse Journal. 2023; 18(2). Doi: 10.51256/ANJ022345;

Key words: P value, statistical significance, significance level

Andrade C. The P value and statistical significance: Misunderstandings, explanations, challenges, and alternatives. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41(3):210-5. doi:10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_193_19

Cook C. Five per cent of the time it works 100 per cent of the time: The erroneousness of the P value. J Man Manip Ther. 2010;18(3):123-5. doi:10.1179/106698110X12640740712257

Heavey E. Statistics for Nursing: A Practical Approach. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2018.

Houser J. Nursing Research: Reading, Using, and Creating Evidence . 4th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2018.

Ioannidis JPA. The importance of predefined rules and prespecified statistical analyses: Do not abandon significance. JAMA . 2019;321(21):2067-8. doi:10.1001/JAMA.2019.4582

Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice . 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2021.

Ranganathan P, Pramesh CS, Buyse M. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Clinical versus statistical significance. Perspect Clin Res . 2015;6(3):169-70. doi:10.4103/2229-3485.159943

Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA statement on p -values: Context, process, and purpose. Am Stat . 2016;70(2):129-33. doi:10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108

Let Us Know What You Think

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post Comment

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Powerful peer-to-peer networks

Knowledge of intravascular determination

Why Mentorship?

Virtual reality: Treating pain and anxiety

What is a healthy nurse?

Nurses make the difference

From data to action

Connecting theory and practice

Turning the tide

Effective clinical learning for nursing students

Leadership style matters

Innovation in motion

Nurse referrals to pharmacy

Lived experience

Elevating the voice of nurses through advocacy

Chung J. Interpreting statistical significance in nursing research. American Nurse Journal. 2023;18(2):45-48. doi:10.51256/anj022345 https://www.myamericannurse.com/interpreting-statistical-significance-in-nursing-research/

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The development and structural validity testing of the Person-centred Practice Inventory–Care (PCPI-C)

Contributed equally to this work with: Brendan George McCormack, Paul F. Slater, Fiona Gilmour, Denise Edgar, Stefan Gschwenter, Sonyia McFadden, Ciara Hughes, Val Wilson, Tanya McCance

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Faculty of Medicine and Health, Susan Wakil School of Nursing and Midwifery/Sydney Nursing School, The University of Sydney, Camperdown Campus, New South Wales, Australia

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute of Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University, Belfast, Northern Ireland

Roles Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Nursing, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, Scotland

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Nursing and Midwifery Directorate, Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District, New South Wales, Australia

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Nursing Science with Focus on Person-Centred Care Research, Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences, Krems, Austria

Roles Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Prince of Wales Hospital, South East Sydney Local Health District, New South Wales, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Brendan George McCormack,

- Paul F. Slater,

- Fiona Gilmour,

- Denise Edgar,

- Stefan Gschwenter,

- Sonyia McFadden,

- Ciara Hughes,

- Val Wilson,

- Tanya McCance

- Published: May 10, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158

- Reader Comments

Person-centred healthcare focuses on placing the beliefs and values of service users at the centre of decision-making and creating the context for practitioners to do this effectively. Measuring the outcomes arising from person-centred practices is complex and challenging and often adopts multiple perspectives and approaches. Few measurement frameworks are grounded in an explicit person-centred theoretical framework.

In the study reported in this paper, the aim was to develop a valid and reliable instrument to measure the experience of person-centred care by service users (patients)–The Person-centred Practice Inventory-Care (PCPI-C).

Based on the ‘person-centred processes’ construct of an established Person-centred Practice Framework (PCPF), a service user instrument was developed to complement existing instruments informed by the same theoretical framework–the PCPF. An exploratory sequential mixed methods design was used to construct and test the instrument, working with international partners and service users in Scotland, Northern Ireland, Australia and Austria. A three-phase approach was adopted to the development and testing of the PCPI-C: Phase 1 –Item Selection : following an iterative process a list of 20 items were agreed upon by the research team for use in phase 2 of the project; Phase 2 –Instrument Development and Refinement : Development of the PCPI-C was undertaken through two stages. Stage 1 involved three sequential rounds of data collection using focus groups in Scotland, Australia and Northern Ireland; Stage 2 involved distributing the instrument to members of a global community of practice for person-centred practice for review and feedback, as well as refinement and translation through one: one interviews in Austria. Phase 3 : Testing Structural Validity of the PCPI-C : A sample of 452 participants participated in this phase of the study. Service users participating in existing cancer research in the UK, Malta, Poland and Portugal, as well as care homes research in Austria completed the draft PCPI-C. Data were collected over a 14month period (January 2021-March 2022). Descriptive and measures of dispersion statistics were generated for all items to help inform subsequent analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using maximum likelihood robust extraction testing of the 5-factor model of the PCPI-C.

The testing of the PCPI-C resulted in a final 18 item instrument. The results demonstrate that the PCPI-C is a psychometrically sound instrument, supporting a five-factor model that examines the service user’s perspective of what constitutes person-centred care.

Conclusion and implications

This new instrument is generic in nature and so can be used to evaluate how person-centredness is perceived by service users in different healthcare contexts and at different levels of an organisation. Thus, it brings a service user perspective to an organisation-wide evaluation framework.

Citation: McCormack BG, Slater PF, Gilmour F, Edgar D, Gschwenter S, McFadden S, et al. (2024) The development and structural validity testing of the Person-centred Practice Inventory–Care (PCPI-C). PLoS ONE 19(5): e0303158. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158

Editor: Nabeel Al-Yateem, University of Sharjah, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

Received: January 26, 2023; Accepted: April 20, 2024; Published: May 10, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 McCormack et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data cannot be shared publicly because of ethical reason. Data are available from the Ulster University Institutional Data Access / Ethics Committee (contact via email on [email protected] ) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Person-centred healthcare focuses on placing the beliefs and values of service users at the centre of decision-making and creating the context for practitioners to do this effectively. Person-centred healthcare goes beyond other models of shared decision-making as it requires practitioners to work with service users (patients) as actively engaged partners in care [ 1 ]. It is widely agreed that person-centred practice has a positive influence on the care experiences of all people associated with healthcare, service users and staff alike. International evidence shows that person-centred practice has the capacity to have a positive effect on the health and social care experiences of service users and staff [ 1 – 4 ]. Person-centred practice is a complex health care process and exists in the presence of respectful relationships, attitudes and behaviours [ 5 ]. Fundamentally, person-centred healthcare can be seen as a move away from neo-liberal models towards the humanising of healthcare delivery, with a focus on the development of individualised approaches to care and interventions, rather than seeing people as ‘products’ that need to be moved through the system in an efficient and cost-effective way [ 6 ].

Person-centred healthcare is underpinned by philosophical and theoretical constructs that frame all aspects of healthcare delivery, from the macro-perspective of policy and organisational practices to the micro-perspective of person-to-person interaction and experience of healthcare (whether as professional or service user) and so is promoted as a core attribute of the healthcare workforce [ 1 , 7 ]. However, Dewing and McCormack [ 8 ] highlighted the problems of the diverse application of concepts, theories and models all under the label of person-centredness, leading to a perception of person-centred healthcare being poorly defined, non-specific and overly generalised. Whilst person-centredness has become a well-used term globally, it is often used interchangeably with other terms such as ’woman-centredness’ [ 9 ], ’child-centredness’ [ 10 ], ’family-centredness’ [ 11 ], ’client-centredness’ [ 12 ] and ’patient-centredness’ [ 13 ]. In their review of person-centred care, Harding et al [ 14 ] identified three fundamental ‘stances’ that encompass person-centred care— Person-centred care as an overarching grouping of concepts : includes care based on shared-decision making, care planning, integrated care, patient information and self-management support; Person-centred care emphasising personhood : people being immersed in their own context and a person as a discrete human being; Person-centred care as partnership : care imbued with mutuality, trust, collaboration for care, and a therapeutic relationship.

Harding et al. adopt the narrow focus of ’care’ in their review, and others contend that for person-centred care to be operationalised there is a need to understand it from an inclusive whole-systems perspective [ 15 ] and as a philosophy to be applied to all persons. This inclusive approach has enabled the principles of person-centredness to be integrated at different levels of healthcare organisations and thus enable its embeddedness in health systems [ 16 – 19 ]. This inclusive approach is significant as person-centred care is impossible to sustain if person-centred cultures do not exist in healthcare organisations [ 20 , 21 ].

McCance and McCormack [ 5 ] developed the Person-centred Practice Framework (PCPF) to highlight the factors that affect the delivery of person-centred practices. McCormack and McCance published the original person-centred nursing framework in 2006. The Framework has evolved over two decades of research and development activity into a transdisciplinary framework and has made a significant contribution to the landscape of person-centredness globally. Not only does it enable the articulation of the dynamic nature of person-centredness, recognising complexity at different levels in healthcare systems, but it offers a common language and a shared understanding of person-centred practice. The Person-centred Practice Framework is underpinned by the following definition of person-centredness:

[A]n approach to practice established through the formation and fostering of healthful relationships between all care providers , service users and others significant to them in their lives . It is underpinned by values of respect for persons , individual right to self-determination , mutual respect and understanding . It is enabled by cultures of empowerment that foster continuous approaches to practice development [ 16 ].

The Person-centred Practice Framework ( Fig 1 ) comprises five domains: the macro context reflects the factors that are strategic and political in nature that influence the development of person-centred cultures; prerequisites focus on the attributes of staff; the practice environment focuses on the context in which healthcare is experienced; the person-centred processes focus on ways of engaging that are necessary to create connections between persons; and the outcome , which is the result of effective person-centred practice. The relationships between the five domains of the Person-centred Practice Framework are represented pictorially, that being, to reach the centre of the framework, strategic and policy frames of reference need to be attended to, then the attributes of staff must be considered as a prerequisite to managing the practice environment and to engaging effectively through the person-centred processes. This ordering ultimately leads to the achievement of the outcome–the central component of the framework. It is also important to recognise that there are relationships and there is overlap between the constructs within each domain.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158.g001

In 2015, Slater et al. [ 22 ] developed an instrument for staff to use to measure person centred practice- the Person-centred Practice Inventory- Staff (PCPI-S). The PCPI-S is a 59-item, self-report measure of health professionals’ perceptions of their person-centred practice. The items in the PCPI-S relate to seventeen constructs across three domains of the PCPF (prerequisites, practice environment and person-centred processes). The PCPI-S has been widely used, translated into multiple languages and has undergone extensive psychometric testing [ 23 – 28 ].

No instrument exists to measure service users’ perspectives of person-centred care that is based on an established person-centred theoretical framework or that is designed to compare with service providers perceptions of it. In an attempt to address this gap in the evidence base, this study set out to develop such a valid and reliable instrument. The PCPI-C focuses on the person-centred processes domain, with the intention of measuring service users’ experiences of person-centred care. The person-centred processes are the components of care that directly affect service users’ experiences. The person-centred processes enable person-centred care outcomes to be achieved and include working with the person’s beliefs and values, sharing decision-making, engaging authentically, being sympathetically present and working holistically. Based on the ‘person-centred processes’ construct of the PCPF and relevant items from the PCPI-S, a version for service users was developed.

This paper describes the processes used to develop and test the instrument–The Person-centred Practice Inventory-Care (PCPI-C). The PCPI-C has the potential to enable healthcare services to understand service users’ experience of care and how they align with those of healthcare providers.

Materials and methods

The aim of this research was to develop and test the face validity of a service users’ version of the person-centred practice inventory–The Person-centred Practice Inventory-Care.

The development and testing of the instrument was guided by the instrument development principles of Boateng et al [ 29 ] ( Fig 2 ) and reported in line with the COSMIN guidelines for instrument testing [ 30 , 31 ]. An exploratory sequential mixed methods design was used to construct and test the instrument [ 29 , 30 ] working with international partners and service users. A three-phase approach was adopted to the development and testing of the PCPI-C. As phases 1 and 2 intentionally informed phase 3 (the testing phase), these two phases are included here in our description of methods.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158.g002

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was sought and gained for each phase of the study and across each of the participating sites. For phase 2 of the study, a generic research protocol was developed and adapted for use by the Scottish, Australian and Northern Irish teams to apply for local ethical approval. In Scotland, ethics approval was gained from Queen Margaret University Edinburgh Divisional Research Ethics Committee; in Australia, ethics approval was gained from The University of Wollongong and in Northern Ireland ethics approval was gained from the Research Governance Filter Committee, Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University. For phase 3 of the study, secondary analysis of an existing data set was undertaken. For the original study from which this data was derived (see phase 3 for details), ethical approval was granted by the UK Office of Research Ethics Committee Northern Ireland (ORECNI Ref: FCNUR-21-019) and Ulster University Research Ethics Committee. Additional local approvals were obtained for each partner site as required. In addition, a data sharing agreement was generated to facilitate sharing of study data between European Union (EU) sites and the United Kingdom (UK).

Phase 1 –Item selection

An initial item pool for the PCPI-C was identified by <author initials to be added after peer-review> by selecting items from the ‘person-centred processes’ sub-scale of the PCPI-S ( Table 1 ). Sixteen items were extracted, and the wording of the statements was adjusted to reflect a service-user perspective. Additional items were identified (n = 4) to fully represent the construct from a service-user perspective. A final list of 20 items was agreed upon and this 20-item questionnaire was used in Phase 2 of the instrument development.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158.t001

Phase 2 –Instrument development and refinement

Testing the validity of PCPI-C was undertaken through three sequential rounds of data collection using focus groups in Scotland, Australia and Northern Ireland. The purpose of these focus groups was to work with service users to share and compare understandings and views of their experiences of healthcare and to consider these experiences in the context of the initial set of PCPI-C items generated in phase 1 of the study. These countries were selected as the lead researchers had established relationships with healthcare partners who were willing to host the research. The inclusion of multiple countries provided different perspectives from service users who used different health services. In Scotland, a convenience sample of service users (n = 11) attending a palliative care day centre of a local hospice was selected. In Australia a cancer support group for people living with a cancer diagnosis (n = 9) was selected and in Northern Ireland, people with lived experience who were attending a community group hosted by a Cancer Charity (n = 9) were selected. All service users were current users of healthcare and so the challenge of memory recall was avoided. The type of conditions/health problems of participants was not the primary concern. Instead, we targeted persons who had recent experiences of the health system. The three centres selected were known to the researchers in those geographical areas and relationships were already established, which helped with gaining access to potential participants. Whilst the research team had potential access to other centres in each country, it was evident at focus group 3 that no significant new issues were being identified from the participants and thus we agreed to not do further rounds of refinement.

A Focus Group guide was developed ( Fig 3 ). Participants were invited to draw on their experiences as a user of the service; particularly remembering what they saw, the way they felt and what they imagined was happening [ 32 ]. The participants were invited to independently complete the PCPI-C and the purpose of the exercise was reiterated i.e. to think about how each question of the PCPI-C reflected their own experiences and their answers to the questions. Following completion of the questionnaire, participants were asked to comment on each question in the PCPI-C (20 questions), with a specific focus on their understanding of the question, what they thought about when they read the question, and any suggestions to improve readability. The focus group was concluded with a discussion on the overall usability of the PCPI-C. Each focus group was audiotaped and the audio recordings were transcribed in full. The facilitators of the focus group then listened to the audio recordings, alongside the transcripts, and identified the common issues that arose from the discussions and noted against each of the questions in the draft PCPI-C. Revisions were made to the questions in accordance with the comments and recommendations of the participants. At the end of the analysis phase of each focus group, a table of comments and recommendations mapped to the questions in the instrument was compiled and sent to the whole research team for review and consideration. The comments and recommendations were reviewed by the research team and amendments made to the draft PCPI-C. The amended draft was then used in the next focus group until a final version was agreed. Focus group 1 was held in Scotland, focus group 2 in Australia and focus group 3 in Northern Ireland. Table 2 presents a summary of the feedback from the final focus group.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158.g003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158.t002

A final stage of development involved distributing the agreed version of the PCPI-C to members of ‘The International Community of Practice for Person-centred Practice’ (PcP-ICoP) for review and feedback. The PcP-ICoP is an international community of higher education, health and care organisations and individuals who are committed to advancing knowledge in the field of person-centredness. No significant changes to the distributed version were suggested by the PcP-ICoP members, but several members requested permission to translate the instrument into their national language. PcP-ICoP members at the University of Vienna, who were leading on a large research project with nursing homes in the region of Lower Austria, agreed to undertake a parallel translation project as a priority, so they could use the PCPI-C in their research project. The instrument was culturally and linguistically adapted to the nursing home setting in an iterative process by the Austrian research team in collaboration with the international research team. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews by trained research staff. Residents of five nursing homes for older persons in Lower Austria were included. All residents who did not have a cognitive impairment or were physically unable to complete the questionnaire (because of ill-health) (n = 235) were included. 71% of these residents (N = 167) managed to complete the questionnaire. Whilst in Austria, formal ethical approval for non-intervention studies is not required, the team sought informed consent from participants. Particular attention was paid throughout the interviews to assure ongoing consent of residents by carefully guided conversations.

Phase 3: Testing structural validity of the PCPI-C

The aim of this phase was to test the structural validity of the PCPI-C using confirmatory factor analysis with an international sample of service users. The PCPI-C comprises 20 items measured on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree. The 20 items represent the 5 constructs comprising the final model to be tested, which is outlined in Table 3 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158.t003

A sample of 452 participants was selected for this phase of the study. The sample selected comprised two groups. Group 1 (n = 285) were service users with cancer (breast, urological and other) receiving radiotherapy in four Cancer Treatment Centres in four European Countries–UK, Malta, Poland and Portugal. These service users were participants in a wider SAFE EUROPE ( www.safeeurope.eu ) project exploring the education and professional migration of therapeutic radiographers in the European Union. In the UK a study information poster with a link to the PCPI-C via Qualtrics © survey was disseminated via UK cancer charity social media websites. Service user information and consent were embedded in the online survey and presented to the participant following the study link. At the non-UK sites, hard copy English versions of the surveys were available in clinical departments where a convenience sampling approach was used, inviting everyone in their final few days of radiotherapy to participate. The ‘DeepL Translator’ software (DeepL GmbH, Cologne, Germany) was used to make the necessary terminology adaptions for both the questionnaire and the participant information sheet across the various countries. Fluent speakers based in the participating sites and who were members of the SAFE EUROPE project team confirmed the accuracy of this process by checking the accuracy of the translated version against the original English version. Participants were provided with study information and had at least 24 hours to decide if they wished to participate. Willing participants were then invited to provide written informed consent by the local study researcher. The study researcher provided the hard copy survey to the service user but did not engage with or assist them during completion. Service users were informed they could take the survey home for completion if they wished. Completed surveys were returned to a drop box in the department or returned by post (data collected May 2021-March 2022). Group 2 were residents in nursing homes in Lower Austria (n = 125). No participating residents had a cognitive impairment and were physically able to complete the questionnaire. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews by trained research staff (data collected January 2021-March 2021).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and measures of dispersion statistics were generated for all items to help inform subsequent analysis. Measures of appropriateness to conduct factor analysis were conducted using The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measures of Sampling Adequacy and Bartletts Test of Sphericity. Inter-item correlations were generated to examine for collinearity prior to full analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using maximum likelihood robust extraction testing of the 5-factor model.

Acceptable fit statistics were set at Root Mean Square Estimations of Approximation (RMSEA) of 0.05 or below; 90% RMSEA higher bracket below 0.08; and Confirmation Fit Indices (CFI) of 0.95 or higher and SRMR below 0.05 [ 33 – 35 ]. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach alpha scores for factors in the accepted factor model.

The model was re-specified using the modification indices provided in the statistical output until acceptable and a statistically significant relationship was identified. All re-specifications of the model were guided by principles of (1) meaningfulness (a clear theoretical rationale); (2) transitivity (if A is correlated to B, and B correlated to C, then A should correlate with C); and (3) generality (if there is a reason for correlating the errors between one pair of errors, then all pairs for which that reason applies should also be correlated) [ 36 ].

Acceptance modification criteria of:

- The items to first order factors were initially fitted.

- Correlated error variance permitted as all items were measuring the same unidimensional construct.

- Only statistically significant relationship retained to help produce as parsimonious a model as possible.

- Factor loadings above 0.40 to provide a strong emergent factor structure.

Factor loading scores were based on Comrey and Lee’s [ 37 ] guidelines (>.71 = excellent, >.63 = very good, >.55 = good, >.45 = fair and >.32 = poor) and acceptable factor loading given the sample size (n = 452) were set at >0.3 [ 33 , 38 ].

Results and discussion

Demographic details.

The sample of 452 participants represented an international sample of respondents drawn from across five countries: UK (14.6% n = 66), Portugal (47.8%. n = 216), Austria (27.7%, n = 125), Malta (6.6, n = 30) and Poland (3.3%, n = 15). Table 4 outline the demographic characteristics of the sample. The final sample of 452 participants provides an acceptable ratio 33 of 22:1 respondent to items.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158.t004

The means scores indicate that respondents scored the items neutrally. The measures of skewness and kurtosis were acceptable and satisfied the conditions of normality of distribution for further psychometric testing. Examination of the Kaiser Meyer Olkin (0.947) and the Bartlett test for sphericity (4431.68, df = 190, p = 0.00) indicated acceptability of performing factor analysis on the items. Cronbach alpha scores for each of the constructs confirm the acceptability and unidimensionality of each construct.

Examination of the correlation matrix between items shows a range of between 0.144 and 0.740, indicating a broadness in the areas of care the questionnaire items address, as well as no issues of collinearity. The original measurement model was examined using maximum likelihood extraction and the original model had mixed fit statistics. All factor loadings (except for items 11 and 13) were above the threshold of 0.4 ( Table 3 ). Six further modifications were introduced into the original model based on highest scored modification indices until the fit statistics were deemed acceptable ( Table 5 for model fit statistics and Fig 4 for items correlated errors). Two item correlated error modifications were within factors and 4 between factors. The accepted model factor structure is displayed in Fig 4 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158.g004

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303158.t005

Measuring person-centred care is a complex and challenging endeavour [ 39 ]. In a review of existing measures of person-centred care, DeSilva [ 39 ] identified that whilst there are many tools available to measure person-centred care, there was no agreement about which tools were most worthwhile. The complexity of measurement is further reinforced by the multiplicity of terms used that imply a person-centred approach being adopted without explicitly setting out the meaning of the term. Further, person-centred care is multifaceted and comprises a multitude of methods that are held together by a common philosophy of care and organisational goals that focus on service users having the best possible (personalised) experience of care. As DeSilva suggested, “it is a priority to understand what ‘person-centred’ means . Until we know what we want to achieve , it is difficult to know the most appropriate way to measure it . (p 3)” . However, it remains the case that many of the methods adopted are poorly specified and not embedded in clear conceptual or theoretical frameworks [ 40 , 41 ]. A clear advantage of the study reported here is that the PCPI-C is embedded in a theoretical framework of person-centredness (the PCPF) that clearly defines what we mean by person-centred practice. The PCPI-C is explicitly informed by the ‘person-centred processes’ domain of the PCPF, which has an explicit focus on the care processes used by healthcare workers in providing healthcare to service-users.

In the development of the PCPI-C, initial items were selected from the Person-centred Practice Inventory-Staff (PCPI-S) and these items are directly connected with the person-centred processes domain of the PCPF. The PCPI-S has been translated, validated and adopted internationally [ 23 – 28 ] and so provides a robust theoretically informed starting point for the development of the PCPI-C. This starting point contributed to the initial acceptability of the instrument to participants in the focus groups. Like DeSilva, [ 39 ] McCormack et al [ 42 ] and McCormack [ 41 ] have argued that measuring person-centred care as an isolated activity from the evaluation of the impact of contextual factors on the care experienced, is a limited exercise. As McCormack [ 41 ] suggests “ Evaluating person-centred care as a specific intervention or group of interventions , without understanding the impact of these cultural and contextual factors , does little to inform the quality of a service . ” (p1) Using the PCPI-C alongside other instruments such as the PCPI-S helps to generate contrasting perspectives from healthcare providers and healthcare service users, informed by clear definitions of terms that can be integrated in quality improvement and practice development programmes. The development of the PCPI-C was conducted in line with good practice guidelines in instrument development [ 29 ] and underpinned by an internationally recognised person-centred practice theoretical framework, the PCPF [ 5 ]. The PCPI-C provides a psychometrically robust tool to measure service users’ perspectives of person-centred care as an integrated and multi-faceted approach to evaluating person-centredness more generally in healthcare organisations.

With the advancement of Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS) [ 43 , 44 ], Patient Reported Experience Measures (PREMS) [ 45 ] and the World Health Organization (WHO) [ 15 ] emphasis on the development of people-centred and integrated health systems, greater emphasis has been placed on developing measures to determine the person-centredness of care experienced by service users. Several instruments have been developed to measure the effectiveness of person-centred care in specific services, such as mental health [ 45 ], primary care [ 46 , 47 ], aged care [ 48 , 49 ] and community care [ 50 ]. However only one other instrument adopts a generic approach to evaluating services users’ experiences of person-centred care [ 51 ]. The work of Fridberg et al (The Generic Person-centred Care Questionnaire (GPCCQ)) is located in the Gothenburg Centre for Person-centred Care (GPCC) concept of person-centredness—patient narrative, partnership and documentation. Whilst there are clear connections between the GPCCQ and the PCPI-C, a strength of the PCPI-C is that it is set in a broader system of evaluation that views person-centredness as a whole system issue, with all parts of the system needing to be consistent in concepts used, definitions of terms and approaches to evaluation. Whilst the PCPI-S evaluates how person-centredness is perceived at different levels of the organisation, using the same theoretical framework and the same definition of terms, the PCPI-C brings a service user perspective to an organisation-wide evaluation framework.

A clear strength of this study lies in the methods engaged in phase 2. Capturing service user experiences of healthcare has become an important part of the evaluation of effectiveness. Service user experience evaluation methodologies adopt a variety of methods that aim to capture key transferrable themes across patient populations, supported by granular detail of individual specific experience [ 43 ]. This kind of service evaluation depends on systematically capturing a variety of experiences across different service-user groups. In the research reported here, service users from a variety of services including palliative care and cancer services from three countries, engaged in the focus group discussions and were freely able to discuss their experiences of care and consider them in the context of the questionnaire items. The use of focus groups in three different countries enabled different cultural perspectives to be considered in the way participants engaged with discussions and considered the relevance of items and their wording. The sequential approach enabled three rounds of refinement of the items and this enabled the most relevant wording to be achieved. The range of comments and depth of feedback prevented ‘knee-jerk’ changes being made based on one-off comments, but instead, it was possible to compare and contrast the comments and feedback and achieve a more considered outcome. The cultural relevance of the instrument was reinforced through the translation of the instrument to the German language in Austria, as few changes were made to the original wording in the translation process. This approach combined the capturing of individual lived experience with the systematic generation of key themes that can assist with the systematic evaluation of healthcare services. Further, adopting this approach provides a degree of confidence to users of the PCPI-C that it represents real service-user experiences.

The factorial validity of the instrument was supported by the findings of the study. The modified models fit indices suggest a good model fit for the sample [ 31 , 34 , 35 ]. The Confirmation Fit Indices (CFI) fall short of the threshold of >0.95. However, this is above 0.93 which is considered an acceptable level of fit [ 52 ]. Examination of the alpha scores confirm the reliability (internal consistency) of each construct [ 53 ]. All factor loadings were at a statistically significant level and above the acceptable criteria of 0.3 recommended for the sample size [ 38 ]. All but 2 of the loadings (v11 –‘ Staff don’t assume they know what is best for me’ and v13 – ‘My family are included in decisions about my care only when I want them to be’ ) were above the loadings considered as good to excellent [ 37 ]. At the level of construct, previous research by McCance et al [ 54 ] showed that all five constructs of the person-centred processes domain of the Person-centred Practice Framework carried equal significance in shaping how person-centred practice is delivered, and this is borne out by the approval of a 5-factor model in this study. However, it is also probable that there is a degree of overlap between items across the constructs, reflected in the 2 items with lower loadings. Other items in the PCPI-C address perspectives on shared decision-making and family engagement and thus it was concluded that based on the theoretical model and statistical analysis, these 2 items could be removed without compromising the comprehensiveness of the scale, resulting in a final 18-item version of the PCPI-C (available on request).

Whilst a systematic approach to the development of the PCPI-C was adopted, and we engaged with service users in several care settings in different countries, further research is required in the psychometric testing of the instrument across differing conditions, settings and with culturally diverse samples. Whilst the sample does provide an acceptable respondent to item ratio, and the sample contains international respondents, the model structure is not examined across international settings. Likewise, further research is required across service users with differing conditions and clinical settings. Whilst this is a limitation of this study reported here, the psychometric testing of an instrument is a continuous process and further testing of the PCPI-C is welcomed.

Conclusions

This paper has presented the systematic approach adopted to develop and test a theoretically informed instrument for measuring service users’ perspectives of person-centred care. The instrument is one of the first that is generic and theory-informed, enabling it to be applied as part of a comprehensive and integrated framework of evaluation at different levels of healthcare organisations. Whilst the instrument has good statistical properties, ongoing testing is recommended.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this paper acknowledge the significant contributions of all the service users who participated in this study.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 2. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America (2001) Crossing the Quality Chasm : A New Health System for the 21st Century . Washington: National Academies Press. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/10027/crossing-the-quality-chasm-a-new-health-system-for-the (Accessed 20/1/2023).

- PubMed/NCBI

- 5. McCance T. and McCormack B. (2021) The Person-centred Practice Framework, in McCormack B, McCance T, Martin S, McMillan A, Bulley C (2021) Fundamentals of Person-centred Healthcare Practice . Oxford. Wiley. PP: 23–32 https://www.perlego.com/book/2068078/fundamentals-of-personcentred-healthcare-practice-pdf?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&gclid=Cj0KCQjwtrSLBhCLARIsACh6Rmj9sarf1IjwEHCseXMsPLGeUTTQlJWYL6mfQEQgwO3lnLkUU9Gb0A8aAgT1EALw_wcB .

- 7. Nursing and Midwifery Council (2018) Future Nurse : Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses . London. Nursing and Midwifery Council. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/standards-of-proficiency/nurses/future-nurse-proficiencies.pdf (Accessed 20/1/2023).

- 14. Harding E., Wait S. and Scrutton J. (2015) The State of Play in Person-centred Care : A Pragmatic Review of how Person-centred Care is Defined , Applied and Measured . London: The Health Policy Partnership.

- 16. McCormack B. and McCance T. (2017) Person-centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care : Theory and Practice . Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- 17. Buetow S. (2016) Person-centred Healthcare : Balancing the Welfare of Clinicians and Patients . Oxford: Routledge.

- 32. Kruger R. A. and Casey M. A., (2000). Focus groups : A practical guide for applied research . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- 33. Kline P., (2014). An easy guide to factor analysis . Oxfordshire. Routledge.

- 34. Byrne B.M., (2013). Structural equation modeling with Mplus : Basic concepts , applications , and programming . Oxfordshire. Routledge.

- 35. Wang J. and Wang X., (2019). Structural equation modeling : Applications using Mplus . New Jersey. John Wiley & Sons.

- 37. Comrey A.L. and Lee H.B., (2013). A first course in factor analysis . New York. Psychology press.

- 38. Hair J.F., Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E. R.L. and Tatham , (2018). Multivariate Data Analysis . 8th Edn., New Jersey. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- 39. DeSilva (2014) Helping measure person-centred care : A review of evidence about commonly used approaches and tools used to help measure person-centred care . London, The Health Foundation. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/helping-measure-person-centred-care .

- 42. McCormack B, McCance T and Maben J (2013) Outcome Evaluation in the Development of Person-Centred Practice In B McCormack, K Manley and A Titchen (2013) Practice Development in Nursing (Vol 2 ) . Oxford. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing. Pp: 190–211.

- 43. Irish Platform for Patients Organisations Science & Industry (IPPOSI) (2018). Patient-centred outcome measures in research & healthcare : IPPOSI outcome report . Dublin, Ireland: IPPOSI. https://www.ipposi.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/PCOMs-outcome-report-final-v3.pdf (Accessed 20/1/2023).

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Data Descriptor

- Open access

- Published: 03 May 2024

A dataset for measuring the impact of research data and their curation

- Libby Hemphill ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3793-7281 1 , 2 ,

- Andrea Thomer 3 ,

- Sara Lafia 1 ,

- Lizhou Fan 2 ,

- David Bleckley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7715-4348 1 &

- Elizabeth Moss 1

Scientific Data volume 11 , Article number: 442 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

686 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Research data

- Social sciences

Science funders, publishers, and data archives make decisions about how to responsibly allocate resources to maximize the reuse potential of research data. This paper introduces a dataset developed to measure the impact of archival and data curation decisions on data reuse. The dataset describes 10,605 social science research datasets, their curation histories, and reuse contexts in 94,755 publications that cover 59 years from 1963 to 2022. The dataset was constructed from study-level metadata, citing publications, and curation records available through the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan. The dataset includes information about study-level attributes (e.g., PIs, funders, subject terms); usage statistics (e.g., downloads, citations); archiving decisions (e.g., curation activities, data transformations); and bibliometric attributes (e.g., journals, authors) for citing publications. This dataset provides information on factors that contribute to long-term data reuse, which can inform the design of effective evidence-based recommendations to support high-impact research data curation decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

SciSciNet: A large-scale open data lake for the science of science research

Data, measurement and empirical methods in the science of science

Interdisciplinarity revisited: evidence for research impact and dynamism

Background & summary.

Recent policy changes in funding agencies and academic journals have increased data sharing among researchers and between researchers and the public. Data sharing advances science and provides the transparency necessary for evaluating, replicating, and verifying results. However, many data-sharing policies do not explain what constitutes an appropriate dataset for archiving or how to determine the value of datasets to secondary users 1 , 2 , 3 . Questions about how to allocate data-sharing resources efficiently and responsibly have gone unanswered 4 , 5 , 6 . For instance, data-sharing policies recognize that not all data should be curated and preserved, but they do not articulate metrics or guidelines for determining what data are most worthy of investment.

Despite the potential for innovation and advancement that data sharing holds, the best strategies to prioritize datasets for preparation and archiving are often unclear. Some datasets are likely to have more downstream potential than others, and data curation policies and workflows should prioritize high-value data instead of being one-size-fits-all. Though prior research in library and information science has shown that the “analytic potential” of a dataset is key to its reuse value 7 , work is needed to implement conceptual data reuse frameworks 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 . In addition, publishers and data archives need guidance to develop metrics and evaluation strategies to assess the impact of datasets.

Several existing resources have been compiled to study the relationship between the reuse of scholarly products, such as datasets (Table 1 ); however, none of these resources include explicit information on how curation processes are applied to data to increase their value, maximize their accessibility, and ensure their long-term preservation. The CCex (Curation Costs Exchange) provides models of curation services along with cost-related datasets shared by contributors but does not make explicit connections between them or include reuse information 15 . Analyses on platforms such as DataCite 16 have focused on metadata completeness and record usage, but have not included related curation-level information. Analyses of GenBank 17 and FigShare 18 , 19 citation networks do not include curation information. Related studies of Github repository reuse 20 and Softcite software citation 21 reveal significant factors that impact the reuse of secondary research products but do not focus on research data. RD-Switchboard 22 and DSKG 23 are scholarly knowledge graphs linking research data to articles, patents, and grants, but largely omit social science research data and do not include curation-level factors. To our knowledge, other studies of curation work in organizations similar to ICPSR – such as GESIS 24 , Dataverse 25 , and DANS 26 – have not made their underlying data available for analysis.

This paper describes a dataset 27 compiled for the MICA project (Measuring the Impact of Curation Actions) led by investigators at ICPSR, a large social science data archive at the University of Michigan. The dataset was originally developed to study the impacts of data curation and archiving on data reuse. The MICA dataset has supported several previous publications investigating the intensity of data curation actions 28 , the relationship between data curation actions and data reuse 29 , and the structures of research communities in a data citation network 30 . Collectively, these studies help explain the return on various types of curatorial investments. The dataset that we introduce in this paper, which we refer to as the MICA dataset, has the potential to address research questions in the areas of science (e.g., knowledge production), library and information science (e.g., scholarly communication), and data archiving (e.g., reproducible workflows).

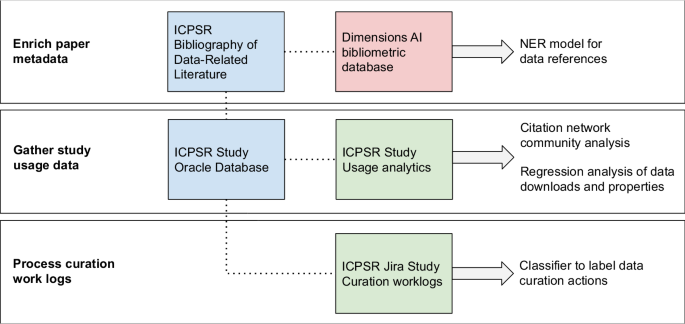

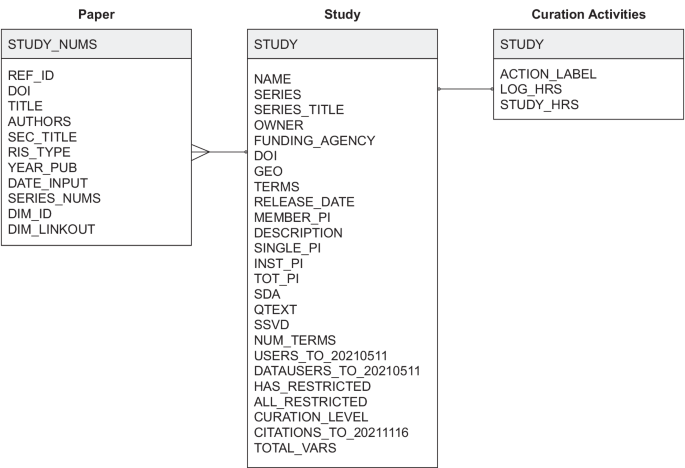

We constructed the MICA dataset 27 using records available at ICPSR, a large social science data archive at the University of Michigan. Data set creation involved: collecting and enriching metadata for articles indexed in the ICPSR Bibliography of Data-related Literature against the Dimensions AI bibliometric database; gathering usage statistics for studies from ICPSR’s administrative database; processing data curation work logs from ICPSR’s project tracking platform, Jira; and linking data in social science studies and series to citing analysis papers (Fig. 1 ).

Steps to prepare MICA dataset for analysis - external sources are red, primary internal sources are blue, and internal linked sources are green.

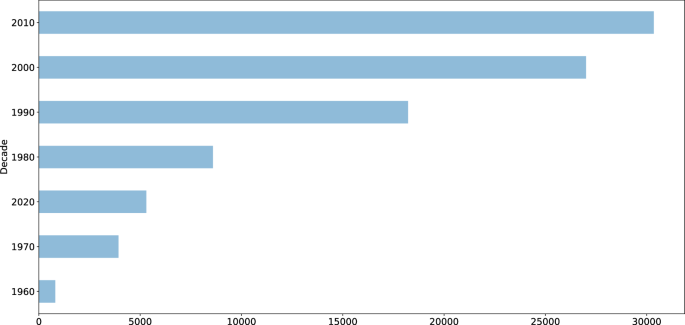

Enrich paper metadata

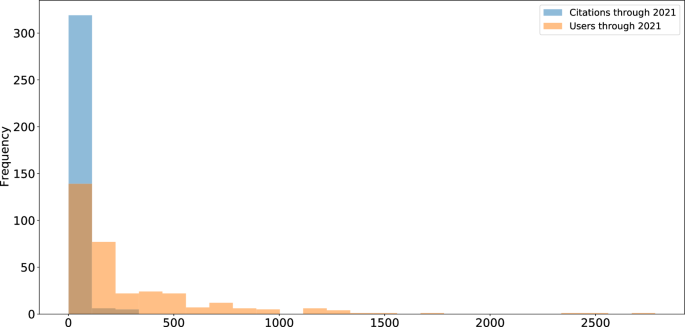

The ICPSR Bibliography of Data-related Literature is a growing database of literature in which data from ICPSR studies have been used. Its creation was funded by the National Science Foundation (Award 9977984), and for the past 20 years it has been supported by ICPSR membership and multiple US federally-funded and foundation-funded topical archives at ICPSR. The Bibliography was originally launched in the year 2000 to aid in data discovery by providing a searchable database linking publications to the study data used in them. The Bibliography collects the universe of output based on the data shared in each study through, which is made available through each ICPSR study’s webpage. The Bibliography contains both peer-reviewed and grey literature, which provides evidence for measuring the impact of research data. For an item to be included in the ICPSR Bibliography, it must contain an analysis of data archived by ICPSR or contain a discussion or critique of the data collection process, study design, or methodology 31 . The Bibliography is manually curated by a team of librarians and information specialists at ICPSR who enter and validate entries. Some publications are supplied to the Bibliography by data depositors, and some citations are submitted to the Bibliography by authors who abide by ICPSR’s terms of use requiring them to submit citations to works in which they analyzed data retrieved from ICPSR. Most of the Bibliography is populated by Bibliography team members, who create custom queries for ICPSR studies performed across numerous sources, including Google Scholar, ProQuest, SSRN, and others. Each record in the Bibliography is one publication that has used one or more ICPSR studies. The version we used was captured on 2021-11-16 and included 94,755 publications.

To expand the coverage of the ICPSR Bibliography, we searched exhaustively for all ICPSR study names, unique numbers assigned to ICPSR studies, and DOIs 32 using a full-text index available through the Dimensions AI database 33 . We accessed Dimensions through a license agreement with the University of Michigan. ICPSR Bibliography librarians and information specialists manually reviewed and validated new entries that matched one or more search criteria. We then used Dimensions to gather enriched metadata and full-text links for items in the Bibliography with DOIs. We matched 43% of the items in the Bibliography to enriched Dimensions metadata including abstracts, field of research codes, concepts, and authors’ institutional information; we also obtained links to full text for 16% of Bibliography items. Based on licensing agreements, we included Dimensions identifiers and links to full text so that users with valid publisher and database access can construct an enriched publication dataset.

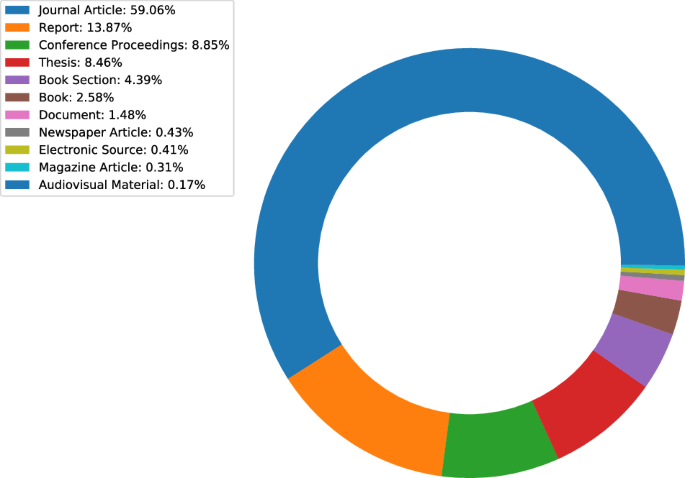

Gather study usage data

ICPSR maintains a relational administrative database, DBInfo, that organizes study-level metadata and information on data reuse across separate tables. Studies at ICPSR consist of one or more files collected at a single time or for a single purpose; studies in which the same variables are observed over time are grouped into series. Each study at ICPSR is assigned a DOI, and its metadata are stored in DBInfo. Study metadata follows the Data Documentation Initiative (DDI) Codebook 2.5 standard. DDI elements included in our dataset are title, ICPSR study identification number, DOI, authoring entities, description (abstract), funding agencies, subject terms assigned to the study during curation, and geographic coverage. We also created variables based on DDI elements: total variable count, the presence of survey question text in the metadata, the number of author entities, and whether an author entity was an institution. We gathered metadata for ICPSR’s 10,605 unrestricted public-use studies available as of 2021-11-16 ( https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/pages/membership/or/metadata/oai.html ).

To link study usage data with study-level metadata records, we joined study metadata from DBinfo on study usage information, which included total study downloads (data and documentation), individual data file downloads, and cumulative citations from the ICPSR Bibliography. We also gathered descriptive metadata for each study and its variables, which allowed us to summarize and append recoded fields onto the study-level metadata such as curation level, number and type of principle investigators, total variable count, and binary variables indicating whether the study data were made available for online analysis, whether survey question text was made searchable online, and whether the study variables were indexed for search. These characteristics describe aspects of the discoverability of the data to compare with other characteristics of the study. We used the study and series numbers included in the ICPSR Bibliography as unique identifiers to link papers to metadata and analyze the community structure of dataset co-citations in the ICPSR Bibliography 32 .

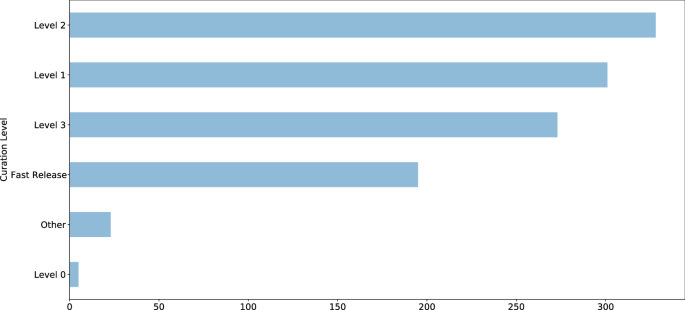

Process curation work logs

Researchers deposit data at ICPSR for curation and long-term preservation. Between 2016 and 2020, more than 3,000 research studies were deposited with ICPSR. Since 2017, ICPSR has organized curation work into a central unit that provides varied levels of curation that vary in the intensity and complexity of data enhancement that they provide. While the levels of curation are standardized as to effort (level one = less effort, level three = most effort), the specific curatorial actions undertaken for each dataset vary. The specific curation actions are captured in Jira, a work tracking program, which data curators at ICPSR use to collaborate and communicate their progress through tickets. We obtained access to a corpus of 669 completed Jira tickets corresponding to the curation of 566 unique studies between February 2017 and December 2019 28 .

To process the tickets, we focused only on their work log portions, which contained free text descriptions of work that data curators had performed on a deposited study, along with the curators’ identifiers, and timestamps. To protect the confidentiality of the data curators and the processing steps they performed, we collaborated with ICPSR’s curation unit to propose a classification scheme, which we used to train a Naive Bayes classifier and label curation actions in each work log sentence. The eight curation action labels we proposed 28 were: (1) initial review and planning, (2) data transformation, (3) metadata, (4) documentation, (5) quality checks, (6) communication, (7) other, and (8) non-curation work. We note that these categories of curation work are very specific to the curatorial processes and types of data stored at ICPSR, and may not match the curation activities at other repositories. After applying the classifier to the work log sentences, we obtained summary-level curation actions for a subset of all ICPSR studies (5%), along with the total number of hours spent on data curation for each study, and the proportion of time associated with each action during curation.

Data Records

The MICA dataset 27 connects records for each of ICPSR’s archived research studies to the research publications that use them and related curation activities available for a subset of studies (Fig. 2 ). Each of the three tables published in the dataset is available as a study archived at ICPSR. The data tables are distributed as statistical files available for use in SAS, SPSS, Stata, and R as well as delimited and ASCII text files. The dataset is organized around studies and papers as primary entities. The studies table lists ICPSR studies, their metadata attributes, and usage information; the papers table was constructed using the ICPSR Bibliography and Dimensions database; and the curation logs table summarizes the data curation steps performed on a subset of ICPSR studies.