Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, 'narnia' finds universe next door.

Now streaming on:

C. S. Lewis, who wrote the Narnia books, and J.R.R. Tolkien, who wrote the Ring trilogy, were friends who taught at Oxford at the same time, were pipe-smokers, drank in the same pub, took Christianity seriously, but although Lewis loved Tolkein’s universe, the affection was not returned. Well, no wonder. When you’ve created your own universe, how do you feel when, in the words of a poem by e. e. cummings:: "Listen: there's a hell/of a good universe next door; let's go."

Tolkien's universe was in unspecified Middle Earth, but Lewis' really was next door. In the opening scenes of "The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe," two brothers and two sisters from the Pevensie family are evacuated from London and sent to live in a vast country house where they will be safe from the nightly Nazi air raids. Playing hide-and-seek, Lucy, the youngest, ventures into a wardrobe that opens directly onto a snowy landscape where before long Mr. Tumnus is explaining to her that he is a faun.

Fauns, like leprechauns, are creatures in the public domain, unlike Hobbits, who are under copyright. There are mythological creatures in Narnia, but most of the speaking roles go to humans like the White Witch (if indeed she is human) and animals who would be right at home in the zoo (if indeed they are animals). The kids are from a tradition which requires that British children be polite and well-spoken, no doubt because Lewis preferred them that way. What is remarkable is that this bookish bachelor who did not marry until he was nearly 60 would create four children so filled with life and pluck.

That's the charm of the Narnia stories: They contain magic and myth, but their mysteries are resolved not by the kinds of rabbits that Tolkien pulls out of his hat, but by the determination and resolve of the Pevensie kids -- who have a good deal of help, to be sure, from Aslan the Lion. For those who read the Lewis books as a Christian parable, Aslan fills the role of Christ because he is resurrected from the dead. I don't know if that makes the White Witch into Satan, but Tilda Swinton plays the role as if she has not ruled out the possibility.

The adventures that Lucy has in Narnia, at first by herself, then with her brother Edmund and finally with the older Peter and Susan, are the sorts of things that might happen in any British forest, always assuming fauns, lions and witches can be found there, as I am sure they can. Only toward the end of this film do the special effects ramp up into spectacular extravaganzas that might have caused Lewis to snap his pipe stem.

It is the witch who has kept Narnia in frigid cold for a century, no doubt because she is descended from Aberdeen landladies. Under the rules, Tumnus ( James McAvoy ) is supposed to deliver Lucy ( Georgie Henley ) to the witch forthwith, but fauns are not heavy hitters, and he takes mercy. Lucy returns to the country house and pops out of the wardrobe, where no time at all has passed and no one will believe her story. Edmund ( Skandar Keynes ) follows her into the wardrobe that evening and is gob-smacked by the White Witch, who proposes to make him a prince.

But Peter ( William Moseley ) and Susan ( Anna Popplewell ) don’t believe Lucy until all four children tumble through the wardrobe into Narnia. They meet the first of the movie's CGI-generated characters, Mr. and Mrs. Beaver (voices by Ray Winstone and Dawn French ), who invite them into their home, which is delightfully cozy for being made of largish sticks. The Beavers explain the Narnian situation to them, just before an attack by computerized wolves whose dripping fangs reach hungrily through the twigs.

Edmund by now has gone off on his own and gotten himself taken hostage, and the Beavers hold out hope that perhaps the legendary Aslan (voice by Liam Neeson ) can save him. This involves Aslan dying for Edmund's sins, much as Christ died for ours. Aslan's eventual resurrection leads into an apocalyptic climax that may be inspired by Revelation. Since there are six more books in the Narnia chronicles, however, we reach the end of the movie while still far from the Last Days.

These events, fantastical as they sound, take place on a more human, or at least more earthly, scale than those in "Lord of the Rings." The personalities and character traits of the children have something to do with the outcome, which is not being decided by wizards on another level of reality but will be duked out right here in Narnia. That the battle owes something to Lewis' thoughts about the first two world wars is likely, although nothing in Narnia is as horrible as the trench warfare of the first or the Nazis of the second.

The film has been directed by Andrew Adamson , who directed both of the " Shrek " movies and supervised the special effects on both of Joel Schumacher's " Batman " movies. He knows his way around both comedy and action, and here combines them in a way that makes Narnia a charming place with fearsome interludes. We suspect that the Beavers are living on temporary reprieve and that wolves have dined on their relatives, but this is not the kind of movie where you bring up things like that.

C.S. Lewis famously said he never wanted the Narnia books to be filmed because he feared the animals would "turn into buffoonery or nightmare." But he said that in 1959, when he might have been thinking of a man wearing a lion suit, or puppets.

The effects in this movie are so skillful that the animals look about as real as any of the other characters, and the critic Emanuel Levy explains the secret: "Aslan speaks in a natural, organic manner (which meant mapping the movement of his speech unto the whole musculature of the animal, not just his mouth)." Aslan is neither as frankly animated as the Lion King or as real as the cheetah in " Duma ," but halfway in between, as if an animal were inhabited by an archbishop.

This is a film situated precisely on the dividing line between traditional family entertainment and the newer action-oriented family films. It is charming and scary in about equal measure, and confident for the first two acts that it can be wonderful without having to hammer us into enjoying it, or else. Then it starts hammering. Some of the scenes toward the end push the edge of the PG envelope, and like the "Harry Potter" series, the Narnia stories may eventually tilt over into R. But it's remarkable, isn't it, that the Brits have produced Narnia, the Ring, Hogwarts, Gormenghast, James Bond, Alice and Pooh, and what have we produced for them in return? I was going to say "the cuckoo clock," but for that you would require a three-way Google of Italy, Switzerland and Harry Lime.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

Now playing

The Long Game

Accidental Texan

Chicken for Linda!

Robert daniels.

Clint Worthington

The Listener

Matt zoller seitz.

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire

Film credits.

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005)

143 minutes

Tilda Swinton as White Witch

Georgie Henley as Lucy Pevensie

Skandar Keynes as Edmund Pevensie

William Moseley as Peter Pevensie

Anna Popplewell as Susan Pevensie

Liam Neeson as Aslan

Ray Winstone as Mr. Beaver

Dawn French as Mrs. Beaver

Rupert Everett as Mr. Fox

Directed by

- Andrew Adamson

- Ann Peacock

- Christopher Markus

- Stephen McFeely

Based on the books by

Latest blog posts.

The 2024 Chicago Palestine Film Festival Highlights

Man on the Moon Is Still the Cure for the Biopic Blues

Part of the Solution: Matthew Modine on Acting, Empathy, and Hard Miles

The Imperiled Women of Alex Garland’s Films

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe - review

We have lived now for 30 years in the era of the cinematic blockbuster. It began with the massive launch of Jaws in 1975 and has encompassed four enormous series that have provided their audiences with eye-popping special effects, a spiritually uplifting mishmash of myth, legend, religion and pop cultural homage, and the prospect of more to follow in a year's time. These series - Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter and now The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the first episode in The Chronicles of Narnia - are known as franchises, a term borrowed by the brazenly commercialised cinema from those anonymous chains of hotels and fast-food joints that spread around the world bearing identical logos.

We also live in an age where everyone is immediately informed of the financial success or otherwise of all new films. Were he alive today, Oscar Wilde would describe a movie buff as a man who knows the weekly gross of everything and the value of nothing. The big question is, will CS Lewis's Narnia books be with us in cinematic form over the next seven years? Perhaps. But in 50 years' time will today's pre-teens be bidding at auction for that Victorian wardrobe in the Professor's house or the White Witch's coach, the way an earlier generation wanted Dorothy's ruby slippers or Kane's Rosebud sledge?

Like Lord of the Rings and the Harry Potter films, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is a very English affair, aimed at young children, who I'm sure will love it. It's briskly directed for much of the way, though with no great individuality, by Andrew Adamson, a film-maker previously noted for his work in animation, most notably the Shrek movies. Drawing on what was, for the book's original readers, the vivid experience of the Second World War, the film centres on four middle-class children: Susan and Peter, who are near teenagers, Edmund, who's a year or so younger than Peter, and Lucy, who is around eight. After an expressionistic re-creation of the London blitz, they're evacuated to a large, rambling country house, home of the remote elderly Professor (who might be either CS Lewis or God) and run by a stern housekeeper. Edmund is an outsider, more sensitive, vulnerable and self-centred than the others (he risks his life during an air raid to save a picture of his father, absent on active service with the RAF), and his name derives from the cunning, manipulative brother in King Lear

Lucy is the most open to imaginative experience and it is she who enters the magical, alternative world of Narnia. One minute the kids are playing hide-and-seek to the strains of the Andrews Sisters' wartime hit 'Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny, Oh!', the next minute Lucy has walked into Narnia through the mysterious wardrobe. In this snow-covered land it is perpetual winter due to the totalitarian White Witch who rules it through her Secret Police. When originally conceived by Lewis, Narnia must have seemed like Nazi-occupied France. When he finished the book in 1950 it also suggested the Eastern Europe of the Cold War.

The children are drawn into the conflict in Narnia as part of an ancient prophecy. They are the only human beings involved in a civil war between the White Witch, the incarnation of evil, and the rebellious forces of good, led by Aslan, a large, fierce lion. Her adherents are vicious talking wolves and deformed mutants. His benign followers include fawns, centaurs and beavers. The children are initially divided, in the way citizens of most occupied countries are. While his siblings side with Aslan, the treacherous Edmund becomes a collaborator, seduced by the Witch through the offer of endless quantities of Turkish delight. We must remember that sweet rationing in Britain didn't end until February 1953. The word 'aslan' is Turkish for lion.

For the Narnia books, Lewis drew on his immense knowledge of medieval literature, as well as on Alice in Wonderland, Beatrix Potter and The Wind in the Willows. He was also influenced, I suspect, by Where the Rainbow Ends, a curiously old-fashioned patriotic play revived every Christmas from 1911 until after the Second World War, in which a party of British public schoolboys assist St George in saving Britain. Noel Coward appeared in it several times as a juvenile and for some years it was a serious rival to Peter Pan.

But it is Lewis's commitment as a Christian apologist that has proved to be the most problematic source. Surprisingly, it's the one that JRR Tolkien, who was largely responsible for his friend's conversion, found objectionable. The influence is to be found in several ways. One of these, both serious and jocular, arises when the first spring in a century comes to Narnia, heralded by the appearance of Father Christmas. The presents he gives the four children are suitable for wartime kids or Christian soldiers, and they come right out of Blake's 'Jerusalem' - a sword and shield for Peter, a bow and a quiver of arrows for Susan, a dagger for little Lucy.

But he also gives Lucy a potion for reviving the near dead, and this leads us to Aslan, the lion. Speaking in the sad, sepulchral voice of Liam Neeson, Aslan is Christ the Redeemer, who lays down his life to save humanity. Following his humiliation and death, he is very specifically resurrected, with Susan and Lucy in attendance like the two Marys. On the other hand, Aslan is very much the British lion, emblem of nation and empire, king of the jungle, the spirit of unification.

Children will not, however, leave the film after its climactic battle thinking of Aslan. The greatest impression is likely to have been made by the White Witch. 'Her face was white, not merely pale,' Lewis writes, 'but white like snow or paper or icing sugar, except for her very red mouth. It was a beautiful face in other respects, but proud and cold and stern.' He might have been describing the mature Tilda Swinton, who was born to play this role. Hers is now as indelible an impersonation of a fictional character as WC Fields's Micawber, Peter Lorre's Joel Cairo or Vivien Leigh's Scarlett O'Hara.

Read Philip French's review of King Kong

- The Observer

- Family films

- Drama films

- Science fiction and fantasy films

Most viewed

Peter Pevensie

Character analysis, leader of the pack.

Peter is the oldest of the four children who travel to Narnia in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe . As the oldest, he is the natural leader, notable for his bravery and good judgment.

But he's not 100% awesome—even though he certainly thinks he is.

Peter has high standards, which sometimes make him seem kind of self-righteous to his more flawed little brother, Edmund. Also, sometimes Peter can be blinded by his own self-importance, like when he finds it difficult to believe his little sister Lucy's story about a world called Narnia, even though he knows that she never lies.

Still, in general, Peter is upright and virtuous. When he learns that Mr. Tumnus the Faun has been arrested for protecting his sister Lucy, Peter immediately thinks that it is his duty to try and rescue Mr. Tumnus in return.

During his stay in Narnia, Peter's bravery and leadership skills only increase. When he and his sisters first meet Aslan, Peter takes the lead, speaking to Aslan first when everyone else is too overawed to say anything. Peter also takes responsibility for his failings: he admits to Aslan, without being asked, that his treatment of Edmund may have contributed to Edmund's betrayal:

"That was partly my fault, Aslan. I was angry with him and I think that helped him to go wrong." (12.19)

As Peter's destiny unfolds, he learns that he is to be High King over his brothers and sisters at the castle of Cair Paravel.

The Few, The Proud, The...Peter

In his first swordfight, Peter slays the wolf Fenris, earning the title "Sir Peter Fenris-bane" from Aslan. But Peter's bravery and success don't mean that he feels no fear. On the contrary, when Peter first sees Fenris attacking Susan, he:

[...] did not feel very brave; indeed, he felt he was going to be sick. But that made no difference to what he had to do. (12.31)

Peter's bravery consists, not in how he feels, but in how he acts. In spite of his fears, Peter pulls himself together and fights. Similarly, when Aslan leaves him in charge of the battle against the Witch, Peter rises to the occasion.

Although we learn that Peter feels "uncomfortable" about fighting the battle alone, and "the news that Aslan might not be there had come as a great shock to him," he still takes on the task and ends up fighting with the Witch in hand-to-hand combat (14.12).

And we think that's a pretty baller move.

Peter seems to know instinctively how to be a warrior—after receiving his sword from Father Christmas, he needs no training before slaying Fenris and fighting in the battle. He also instinctively begins to think like a military tactician; when Aslan leads his followers to the Fords of Beruna, Peter suggests that they camp on the far side of the river to protect them from a night attack by the Witch.

Aslan tells him this is unnecessary, but that:

"All the same it was well though of. That is how a soldier ought to think." (14.11)

Yup. Peter has what it takes.

From Zero To Hero

But still, we think that Peter's transformation from "English schoolboy" to "High King Peter the Magnificent" in little more than a blink of an eye is one of the more unrealistic aspects of the story.And yes—we know this story has mermaids and talking beavers.

Maybe part of the reason we find Peter's development hard to believe is that it happens more between the lines than that of any of the other children. The narrator delves into Edmund's and Lucy's thoughts quite a lot, and we understand how their attitudes change, but we don't focus on Peter that much.

During the final chapters of the story, the narrator chooses to follow Susan, Lucy, and Aslan, leaving Peter and Edmund "offstage" to begin the battle against the Witch. In fact, the book doesn't really narrate much of the battle—just the very end, when the Witch is killed and Good triumphs over Evil.

Tired of ads?

Cite this source, logging out…, logging out....

You've been inactive for a while, logging you out in a few seconds...

W hy's T his F unny?

The Lion, the Witch and the Allegory: An Analysis of Selected Narnia Chronicles

Matt brennan.

The Narnia Chronicles are undoubtedly the most popular works of writer C. S. Lewis. And although they are recognized as children's fantasy novels, they are also popular with students and adults, including many Christian theologians. In the Narnia Chronicles, Lewis typifies the Biblical character of Jesus Christ as the character of Aslan the lion, retelling certain events in the life of Jesus to children in a this new context in a way that is easy for them to understand; most importantly, however, children can both relate to and enjoy the fantasy of Narnia. This essay will to analyze The Magician's Nephew and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to demonstrate that the Narnia Chronicles are not so much didactic allegories, but rather are well-crafted children's fantasies that incorporate Biblical themes in a way that young readers can appreciate.

Although it was the sixth book to be written in the seven book series, the story of The Magician's Nephew takes place several decades before that of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe . It describes the creation of the land of Narnia, and how humans came to be associated with this other world. The narrative draws heavily from the creation story in Genesis, but Lewis' account of Narnian creation is clearly geared to appeal to a younger audience.

One of the the literary techniques Lewis uses to appeal to a younger audience is his use of children as the main characters; in The Magician's Nephew , for instance, Polly & Digory are present throughout the entire narrative. Lewis describes Aslan's creation of the world of Narnia as seen by these two children, immediately establishing a rapport between his young audience and the narrative. As they enter a lightless Narnia at the beginning of its creation, Lewis uses the children to describe their surroundings: "We do seem to be somewhere," said Digory. "At least I'm standing on something solid." (Lewis, 1988, p.91). Digory's first description of this new environment not only establishes a connection between the young readers and the narrative, but is also representative of a trend in Lewis' retelling of the creation story: Lewis draws on the Biblical creation story, but does not attempt to directly parallel the story of Genesis. In Genesis, after creating the heavens and earth, the first thing he does is to create light: "And God said, 'Let there be light.'" (Gen 2:4). It is not, in fact, until the second day that God creates dry land (Gen 1:9-10). The reader of The Magician's Nephew , however, learns from a child's description that even while the world of Narnia is still dark, the earth (or "something solid") has already been created. Obviously, Lewis' primary goal in writing the story of Narnia's creation was not to make an exact allegory to Genesis, but perhaps to draw from select Biblical creation images, and patterning a children's story from them.

Lewis continues to draw from Biblical creation images as he describes the introduction of light into Narnia. The singing stars are the first things to the children see in Narnia, and Lewis again uses the character of Digory to establish a connection between the text and a youthful reader: "If you had seen and heard it, as Digory did, you have felt quite certain that it was the stars themselves which were singing," (Lewis, 1988, p.93-94). Genesis, on the other hand, automatically appeals to adult sensibilities when describing the stars, relating them to such "grown-up" concerns as the calendar: "Let them serve as signs to mark seasons and days and years, and them be lights in the expanse of the sky..." (Gen 1:14-15). The singing stars image that Lewis draws from here is located in Job 38:7. Comparing these two passages, it is evident that Lewis chose to convey his creation story using the Biblical images that are not only easier for children to understand, but also easier for children to appreciate and enjoy.

Another device Lewis uses in the Narnia Chronicles is the personification of animals. Narnia is a land of talking animals, and as children usually find the concept of animals and magical creatures more interesting than that of a historical reality of long ago (i.e. the reality of Jerusalem 2000 years ago). Narnia proves to be the perfect vehicle for a captivating work of children's literature. Upon comparing the creation stories in The Magician's Nephew and the book of Genesis, Lewis' technique of making animals a central part of his narrative is readily noticeable. In Genesis, God creates animals that inhabit land on the fifth day: "God said, 'Let the land produce living creatures according to their kinds: livestock, creatures that move along the ground, and wild animals, each according to its kind.' And it was so." (Gen 1:24-25). The interesting choice of words in this verse may well have been the inspiration for Lewis to write his creative description of the creation of animals in Narnia, where the animals are literally produced by the land, out of the ground: "In all directions it [the land] was swelling into humps. They were of very different sizes some no bigger than mole-hills, some as big as wheel-barrows, two the size of cottages. And the humps move and swelled until they burst, and the crumbled earth poured out of them, and from each hump there came out an animal." (Lewis, 1988, p.105) Lewis' emphasis on the animals in his creation story is especially apparent with his use of Aslan the lion as a God figure: "The Lion opened his mouth...he was breathing out a long, warm breath; it seemed to sway all the beasts as the wind sways a line of trees." (Lewis, 1988, p.108). This image of life-giving breath directly correlates to a passage in Genesis: "The Lord God formed the man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being." (Gen 2:7). Lewis equates the significance of the creation of man in Genesis with the creation of the animals in Narnia, and thereby appeals to a child's natural attraction to animals by making them the central part of the Narnian creation story.

Since animals have taken, at least to some extent, the role of man in the creation story, the human characters of Polly and Digory (and their team) must obviously assume a slightly different role in the creation. At this point, Lewis introduces the concept of evil entering Narnia, and the concept of the introduction of sin into a new world. "Before the new, clean world I gave you is seven hours old, a force of evil has already entered it; waked and brought hither by this son of Adam," says Aslan (Lewis, 1988, p.126). Lewis has cleverly associated Digory with the Biblical Adam in two ways. The obvious connection is that Digory is a male human being, and therefore a "son of Adam". But the the deeper connection that Lewis implies is that just as Adam first brought sin into the world in Genesis, Digory is charged with bringing the first evil into the new world of Narnia.

Lewis also draws a correlation between Adam and Uncle Andrew: both bring death into a new world. The apostle Paul describes Adam as one who brought death into the world: "Sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin," (Rom 5:12). Uncle Andrew, while he does not bring death into Narnia, does bring the concept of death with him. Upon seeing Aslan, his first reaction is to kill: "A most disagreeable place. If only I were a younger man and had a gun --" (Lewis, 1988, p.96). This image of a gun-wielding Uncle Andrew is seen again and again in the narrative: "The first thing is to get that brute shot." (Lewis, 1988, p.103). Lewis is able to affiliate humans not only with evil, but with the race of Adam: a people that brings death and sin. The way in which he achieves this is also very important: by using the image of the slaughter of animals, Lewis once again appeals to the sensibilities of a younger audience. Children are likely to be more upset at the death of an animal than that of a man who lived long ago; a man they never knew. In this way, children might sympathize more easily with the proposed death of a Christ-like lion than that of a historical Jesus (a theme explored later in this essay).

The analysis of evil entering Narnia would not be near complete, of course, without examining the character of Queen Jadis (known in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe as the White Witch). Like Uncle Andrew, the Witch is antagonistic towards Aslan. She too wishes to destroy the lion, and attempts to kill him with an iron bar: "She raised her arm and flung the iron bar straight at its head." (Lewis, 1988, p.99). Later Aslan makes it clear that she is the evil that has entered Narnia: "The world is not five hours old an evil has already entered it" (Lewis, 1988, p.111), "There is an evil witch abroad in my new land of Narnia," (Lewis, 1988, p.125). The allegory of the Witch is still unclear, though. In the creation story in Genesis, two elements of evil can be found. The first is Adam and Eve's direct disobedience to God's commandment (Gen 2-3). The second element, however, is not of human origin, but is rather the character of the serpent (Gen 3). The Witch in The Magician's Nephew can be perhaps seen as an image of the introduction of sin (in the context of the Narnian creation story), but later in the novel Lewis also alludes to her relation with the character of the serpent.

This marks a move away from the theme of creation, and a step towards the theme of temptation in the Narnia Chronicles. The theme of temptation is present in both the Bible and the Narnia Chronicles, and Lewis often models his presentations of temptation after stories and characters from the Bible. A good example of this phenomenon is that of Chapter 13 (Lewis, 1988), which is a retelling of the story of the tree of knowledge. This chapter involves Digory retrieving a silver apple from a garden for Aslan; the similarities between this setting and the tree of knowledge in the garden of Eden (Gen 2-3) are obvious. The role of the Witch, however, evolves from being a symbol of evil to being compared with the serpent in Genesis 3. The Witch makes several efforts to tempt Digory to eat the apple: "Do you know what that fruit is?...It is the apple of youth...Eat it, Boy, eat it," (Lewis, 1988, p.150). This role of temptress is analogous to the role of the serpent when it speaks to Eve (Gen 3:1-5). Lewis has also put Digory in the role of Adam and Eve. Digory's connection to Adam is made explicit by Aslan referring to him as "Son of Adam" throughout the novel. In this retelling of the Garden of Eden story, however, Lewis has Digory make the righteous decision of not eating the apple, but returning to Aslan instead. By having the Witch eat the apple instead (Lewis, 1988, p.149), Lewis allows the roles of protagonist and antagonist to remain clear and distinct. By manipulating the story of the fall of man in this way, Lewis has simplified and contained the forces of good and evil into single characters, making the distinction easier for his children readers understand.

Digory is not the only character to be tempted in Narnia. Uncle Andrew is tempted throughout the narrative by his greed; his lust for money and power. He is forever scheming and dreaming of ways to capitalize on the discovery of Narnia: "The commercial possibilities of this are unbounded...I shall be a millionaire." (Lewis, 1988, p.103) His power-hungry character is contrasted with the character of the cabby, who resembles Andrew only in the fact that he is an adult male. The cabby, however, has a kind of reverent awe of Aslan and the land of Narnia, and voices his disgust in Andrew for not being able to appreciate the miracle of the creation of Narnia: "Oh, stow it Guv'nor, do stow it. Watchin' and listenin's the thing at present; not talking." (Lewis, 1988, p.98) Their relationship is reminiscent of the Biblical story of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). Just as Lazarus received the kingdom of heaven, the cabby becomes the first king of Narnia (Lewis, 1988, p.159), while Andrew is not repaid for succumbing to temptation. This is an example of Lewis' gift to subtly weave Christian teachings into his stories without sacrificing their readability for a young audience.

Perhaps the best example of surrendering to temptation can be found in the second book of the Narnia Chronicles (the first Chronicle, however, for Lewis to write): The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe . The character of Edmund struggles with temptation throughout his time in Narnia, and like Digory, his temptress is the White Witch. Unlike The Magician's Nephew , however, Lewis' use of the Biblical theme of temptation in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe uses New Testament readings as its primary source, drawing from the stories of temptation of both Jesus and Judas.

Keeping the former distinction in mind, an examination of New Testament teaching concerning temptation proves useful. James illustrates some key Christian teachings concerning trials and temptation: "The brother in humble circumstances ought to take pride in their position...He [God] chose to give us birth through the word of truth, that we might be a kind of firstfruits of all he created." (James 1:9, 18). When writing about a good Christian facing temptation, James places emphasis on the righteousness of a man in humble position. He also places importance of the concept of the "word of truth" in humanity. The character of Edmund adheres to neither of these principles.

Edmund's first significant sin is to succumb to the temptation of gluttony (King, 1998). The White Witch offers him enchanted Turkish Delights. The description of his gluttonous and decadent behaviour is very clear: "At first Edmund tried to remember that it was rude to speak with one's mouth full, but soon he forgot about this and thought only of trying to shovel down as much Turkish Delight as he could, and the more he ate the more he wanted to eat..." (Lewis, 1986, p.37) This scene not only the image of Eve succumbing to the temptation of eating the fruit of knowledge, but also to the New Testament theology of Paul: "...many live as enemies of the cross of Christ. Their destiny is destruction, their god is their stomach, and their glory is in their shame. Their mind is on earthly things." (Phil 3:18-19).

Edmund continues to fill his mind with earthly desires by also succumbing to the temptation of improving his humble position (see James 1:9 above) when the White Witch entices him with the prospect of princehood: "I think I would like to make you the Prince -- some day when you bring the others to visit me." (Lewis, 1986, p.39). This temptation of power is very like the story of Jesus being tempted by Satan in the desert. Satan, like the Witch, tempts Jesus with power in exchange for service: "The devil took him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their splendour. "All this I will give you," he said, "if you bow down and worship me." (Matt 4:8-9). In addition to succumbing to these various temptations, Edmund also agrees not to reveal his knowledge of the Witch to his siblings (Lewis, 1986, p.40), and consequentially ends up lying to his them about his discovery of Narnia: "Lucy and I have been playing -- pretending that all her story about a country in the wardrobe is true." (Lewis, 1986, p.44) By doing this, Edmund fulfills the antithesis of Paul's virtues of the good Christian in face of temptation (see James 1:18).

Lewis masterfully intertwines these Biblical themes of temptation into the character of Edmund. But Edmund's character is, in fact, most closely allegorized to the Biblical character of Judas; the betrayer (Matt 26). Edmund betrays his siblings and the Beavers by going to seek the White Witch in Chapter 8 (Lewis, 1986). All he could think about were his earthly desires and wants: "Turkish Delight and to be a prince" (Lewis, 1986, p.82). Comparing a mere child to Judas, however, is a very serious allegory for a children's novel. To deal with this, Lewis creates the idea of the Witch giving Edmund enchanted Turkish Delight: "She knew, though Edmund did not, that this was enchanted Turkish Delight and that anyone who tasted it would want more and more of it, and would even, if they were allowed, to go on eating it till they killed themselves." (p.38). By making Edmund's cravings for Turkish Delight the fault of the Witch and not his own, Lewis alleviates some of the gravity of Edmund's offense; once again taking Biblical imagery and softening it to appeal to a young audience. And in the end, of course, Edmund is forgiven for his betrayal; an event which involves the most important allegorical theme in the Narnia Chronicles: Aslan's synonymy with Jesus Christ.

Before continuing, it should be said that many academics have gone too far in deconstructing the Chronicles of Narnia; theorizing about Lewis' intended "true" meaning for all of his symbolic Bible imagery; to analyze the books in this fashion is to miss Lewis' point in writing them (Schakel, 1979, p.xii). In 1954, Lewis was asked to explain the Aslan-Christ parallel to some fifth graders in Maryland. He replied: "I did not say to myself 'Let us represent Jesus as He really is in our world by a Lion in Narnia'; I said 'Let us suppose that there were land like Narnia and that the Son of God, as he became a Man in our world, became a Lion there, and then imagine what would happen". (Lewis, 1954, 1998) Bearing this in mind, it still proves fruitful to examine how Lewis relates Aslan to the character of the Biblical Jesus, because the analysis yields a better understanding of Lewis' craft: to use Biblical motifs to create a captivating story for children.

Edmund embodies many characteristics of Judas, including the characteristic of betrayal, and Aslan's similarity to Jesus is noticeable in the way he forgives Edmund. Lewis, however, has specifically evaded allegorizing Jesus not forgiving Judas (Mark 14:21), and instead turns to more general Christian teachings on forgiveness: "If someone is caught in a sin, you who are spiritual should restore him gently...Carry each other's burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ." (Gal 6:1-2). In this way, Lewis once again manages to dilute the Biblical narrative into guilt-free children's readability. Aslan forgiveness of Edmund is expressed by his rescue of Edmund from the White Witch (Lewis, 1986, p.124-125). The Witch, however, claims Edmund's life as hers to take: "You at least know the Magic which the Emperor put into Narnia at the very beginning. You know that every traitor belongs to me as my lawful prey and that for every treachery I have a right to kill." (Lewis, 1986, p.128). Aslan then offers his own life in exchange for Edmund's; this action is cataclysmic in its Biblical meaning, because not only is Aslan merely forgiving and dying for Edmund's sin, but the act is also symbolic of Christ dying for the sins of humanity. Edmund's sin of treachery becomes symbolic for all human sins, and Aslan pays for it with his life, as did Christ: "While we were still sinners, Christ died for us." (Rom 5:8).

These events set up the narrative of the execution of Aslan. The former account is incredibly similar in imagery to that of the death of Jesus in the Bible. Lucy and Susan, two of the four child protagonists in the novel, follow Aslan to his execution: "And both the girls cried bitterly (though they hardly knew why) and clung to the Lion..." (Lewis, 1986, p.136). Jesus too had followers not unlike the children: "A large number of people followed him, including women who mourned and wailed for him." (Luke 23:27) Once he is in the hands of the Witch, Aslan is subjected to humiliation and ridicule: "'Stop!' said the Witch. 'Let him first be shaved.'...they worked about his face putting on the muzzle...he [was] surrounded by the whole crowd of creatures kicking him, hitting him, spitting on him, jeering at him." (Lewis, 1986, p.139-140) This imagery is, once again, remarkably similar to that of the Gospels: "The men who were guarding Jesus began mocking and beating him. They blindfolded him and demanded, 'Prophesy! Who hit you?' And they said many other insulting things to him." (Luke 22:63-65)

Aslan's resurrection involves the same kind of Biblical allusion. In the Gospel of Luke, the women who had followed Jesus went to his tomb: "Very early in the morning, the women took the spices they had prepared and went to the tomb. They found the stone rolled away from the tomb, but when they entered, they did not find the body of the Lord Jesus." (Luke 24:1-3) in the same way, after Lucy and Susan take off Aslan's muzzle, they leave the Stone Table where he was executed. In the early morning they return to find the Stone Table broken in two and the resurrected Aslan standing before them (Lewis, 1986, p.142-147). The breaking of the Stone Table is obviously not so similar to the stone in Jesus' tomb as it is to the curtain of the temple being torn (Luke 23:45). The image is even more allusive to the breaking of the tablets containing the Commandments in the book of Exodus. These latter correlation, however, is probably not so much direct allegory as it is an example of Lewis' command of Biblical imagery as a literary device.

Lewis, then, has retold the story of the death and resurrection of Jesus in the context of Aslan and Narnia. He has used several devices, however, to transform this heavy content into material for a children's novel. The obvious difference in Lewis' retelling of the Biblical story is his use of Aslan the lion and the land of Narnia. There is, to an extent, use of lion imagery in the Bible: "You are a lion's cub, O Judah; you return from the prey, my son." (Gen 49:9), "A king's wrath is like the roar of a lion..." (Proverbs 20:2), "They will follow the Lord; he will roar like a lion." (Hosea 11:10). Most important is the reference of lions in the Book of Revelation, referring (we assume) to Christ: "See, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has triumphed." (Rev 5:5). Evidently, Lewis' choice of a lion to represent Christ is not completely original; there are, however, other reasons for Lewis to choose this animal to represent Jesus. For instance, perhaps he assumed that children might better sympathize with the death of an animal than the death of a historical figure. Lewis uses a similar technique in using "Deep Magic" to explain the miraculous events that take place, like the resurrection: "'It is more magic.' They looked round. There, shining in the sunrise, larger than they had seen him before, shaking his mane (for it had apparently grown again), stood Aslan himself." (Lewis, 1986, p.147) The young audience for whom the Narnia Chronicles were mainly intended would have an easier time understanding the concept of magic, rather than the theological implications that arise in the Bible stories of the resurrection. Finally, Lewis uses children as the main characters of the Narnia Chronicles. Immediately this establishes a connection for young readers that the Bible rarely offers. Children are also more likely to relate to a Messiah figure that constantly treats children with respect and love; a figure like Aslan.

The Narnia Chronicles have already established themselves as timeless works of literature. They appeal to both the atheists and the God-fearing, to both the uneducated and to scholars; to children and adults. An understanding of the Biblical allegory in these books is not essential to their appreciation. A critical analysis of these works, however, does allow the reader to more fully appreciate Lewis' unique gift to simplify complex narratives and craft beautiful children's fantasies. This, in turn, allows the reader to gain both a deeper understanding of Lewis as a skilled creative writer, and a deeper satisfaction of his art. To be able to appreciate C. S. Lewis as such a craftsman can only add to one's enjoyment of his works.

Into the Wardrobe Forum

The Into the Wardrobe forum debuted on June 30th, 1996 and was active until October 1st, 2010. The archives are open to the public and are filled with vast amounts of good reading and information for you to enjoy.

If you wish to meet many of the Wardrobians who participated, we are still active on the Into the Wardrobe Facebook group.

Enter the Forum Archives

The Chronicles of Narnia: Books vs. Movies

How do C.S. Lewis's beloved novels differ from their popular screen adaptations? If you're a fan of the Pevensie children and their magical adventures, read on!

The Chronicles of Narnia is a seven-book fantasy series by the legendary C.S. Lewis . The novels are considered classics of children's literature and have sold more than 100 million copies worldwide in 47 languages. Initially published between 1950 and 1956, the series has since been adapted for radio, television, the stage, film, and computer games. To this day, The Chronicles of Narnia remains a highly influential and acclaimed work, leaving a lasting impression on not only fantasy literature but also pop culture as a whole.

Warning: The following article contains spoilers for The Chronicles of Narnia series.

What inspired The Chronicles of Narnia?

As author C.S. Lewis has stated, the idea for The Chronicles of Narnia came from an image of a faun with an umbrella, carrying parcels in the snowy woods. In his essay "It All Began with a Picture," Lewis explains: "This picture had been in my mind since I was about sixteen. Then one day, when I was about forty, I said to myself: 'Let's try to make a story about it.'"

The children of Lewis's stories were inspired by real-life experiences. During World War II, children were being evacuated from London to protect them from anticipated military attacks on the city. At this time, Lewis was living in Risinghurst, three miles east of Oxford city center, and opened his home to a family of three young girls, the Kilns.

Which book in the series should I listen to first?

While the books were not originally written or published in chronological order, the author's family and the publishers now insist that Lewis would want the books to be listened to in chronological order. Meanwhile, some scholars and fans of the books argue that the world of Narnia is best introduced through The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe , and so that book should be heard first, even though it is not the first book chronologically.

What is The Chronicles of Narnia about?

The Chronicles of Narnia envisions a world parallel to ours, and the series sees people from our world traveling over to that world, meeting characters there, exploring, and having adventures. While the series is not explicitly about Christianity, C.S. Lewis was an author of Christian apologetics before he wrote this series and influences from Christian theology are all over The Chronicles of Narnia story. Faith, forgiveness, and salvation are major themes in all of Narnia books.

Who are the main characters of The Chronicles of Narnia?

Aslan is a lion and a major character in all of The Chronicles of Narnia audiobooks—he is widely believed to be a Christ-like figure. Wise and kind, Aslan acts as a guide to the characters from our world who journey to Narnia. He often appears in the story when characters need to be rescued or are in need of moral guidance.

Lucy Pevensie is the youngest of the Pevensie children and the first of the children to journey into Narnia through the wardrobe and meet Mr. Tumnus. Perhaps because she is the youngest, Lucy is the one who has the most faith in Narnia.

Edmund Pevensie is the second youngest Pevensie. When he enters Narnia, he betrays his family and sides with the White Witch. Later, however, Edmund is redeemed and fights alongside his family to protect Narnia.

Susan Pevensie is the second eldest Pevensie. She later becomes queen of Narnia. As an adult, she is courted by the scheming Prince Rabadash. When she refuses his proposal, Rabadash becomes angry and nearly incites a war.

Peter Pevensie is the eldest of the Pevensies and leads the Narnian army against the White Witch in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe . Peter is brave and responsible, which is why Aslan counts on him to close the door to Narnia in The Last Battle .

Mr. Tumnus is a faun and the character who first introduces Lucy (and the listener!) to the magical world of Narnia in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe . Initially, Tumnus brings Lucy to his home in an effort to turn her over to Jadis—but after befriending her, he simply can't betray her. Having failed to do as she ordered, the White Witch turns him into stone.

Prince Caspian is the title character of , the second book published in The Chronicles of Narnia. With the help of the Pevensies, Caspian must take back the throne from his evil uncle, King Miraz, and return Narnia to the magical, wonderful place it once was.

Eustace Scrubb is the Pevensies’ cousin. He is first introduced in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader as a bratty, selfish boy—but after his greed turns him into a dragon, he changes his perspective and helps save Prince Rilian in The Silver Chair and King Tirian in The Last Battle .

Jill Pole is Eustace's school mate who travels to Narnia to help find the lost Prince Rilian in The Silver Chair .

Digory Kirke is the titular character in The Magician's Nephew . He is also "the Professor" in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe who the Pevensies come to stay with after they're evacuated from London. Digory is the one who accidentally awakens Queen Jadis. To make up for that terrible mistake, Aslan asks Digory to find a magical apple with the power to heal his ailing mother and ultimately help to protect Narnia.

Polly Plummer is a friend of Digory's who ends up stranded in the Wood between the Worlds when Digory's wicked uncle tricks her into touching a magic ring.

Queen Jadis , also called the White Witch in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe , is responsible for freezing Narnia, sending it into the Hundred Year Winter. She turns her enemies into statues. She's the only villain to return for more than one book. In T he Magician's Nephew , the prequel to The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe , Digory awakens her.

King Miraz is the main villain in Prince Caspian . He murders Prince Caspian's father, Caspian the Ninth, and usurps the throne. Then when Miraz has a son of his own, he seeks to kill his nephew, the rightful heir, so that his own son can take the throne.

The Lady of the Green Kirtle is the main villain in The Silver Chair. She rules an underground kingdom using magical mind-control. She is also known as Queen of the Underland or simply "the Witch."

Prince Rabadash is the arrogant eldest son of the Tisroc and the main villain in The Horse and His Boy . When Rabadash invades Archenland and is defeated, Aslan punishes him by turning him into a donkey.

Shift the Ape is the main antagonist in The Last Battle . Although the books never describe what kind of ape he is, Pauline Baynes's illustrations depict him as a chimpanzee. Shift is clever and greedy, and he convinces the naïve donkey Puzzle to impersonate Aslan so that he can overtake Narnia.

What happens in The Chronicles of Narnia series?

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950)

This novel introduces listeners to young Lucy, Edmund, Susan, and Peter Pevensie, who have been evacuated to the English countryside following the outbreak of World War II. While staying with Professor Digory Kirke, the siblings discover a magical wardrobe that transports them to the land of Narnia. Together, the Pevensie children help Aslan, a talking lion, save Narnia from Queen Jadis, the evil White Witch, who has sent Narnia into a perpetual winter with no Christmas.

Prince Caspian (1951)

In Prince Caspian, the Pevensies return to Narnia a year after their first adventure. Prince Caspian summons them to Narnia with the help of Susan's magic horn. Although only one year has passed in their world, 1,300 years have passed in the world of Narnia, and much has changed. Now the children must save Narnia from the evil King Miraz, who has usurped the kingdom.

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952)

Three Narnian years after the events of Prince Caspian, this novel sees Edmund and Lucy Pevensie return to Narnia with their cousin, Eustace Scrubb. In Narnia, the children join Caspian's voyage on the ship Dawn Treader in search of the seven lords who were banished when King Miraz took control of Narnia.

The Silver Chair (1953)

The Silver Chair is the first book in The Chronicles of Narnia that does not involve the Pevensie children. In this adventure, Eustace returns to Narnia with his classmate, Jill Pole. Half a century has passed in Narnia since Eustace was last there, and now he and Jill are searching for Caspian's son Rilian, who disappeared 10 years ago on a quest to avenge his mother's death.

The Horse and His Boy (1954)

The Horse and His Boy is the first book set outside of the chronological order of the series. The events of this novel take place during the reign of the Pevensies in Narnia. This book tells the story of Shasta, a runaway boy; Aravis, a runaway aristocrat girl; and Bree and Hwyn, talking Narnian horses.

The Magician's Nephew (1955)

This is the second novel in the series to take place outside of chronological order. The Magician's Nephew is a prequel and the origin story of Narnia, which is why some critics and fans argue it should be heard first. It tells the story of a young Digory Kirke, later known as "the Professor," who stumbles into an alternate world after he and his friend Polly experiment with rings given to them by Digory's uncle. When in the dying world of Charn, Digory accidentally awakens Jadis, who goes on to become the antagonist in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

The Last Battle (1956)

In The Last Battle, Jill and Eustace return to Narnia to save the world from Shift the Ape, who has taken over Narnia after convincing Puzzle the donkey to impersonate Aslan. This story ultimately leads to the end of Narnia as we know it, but in the end Aslan reveals his true form and that this was only the beginning of the real story, "which goes on forever, and in which every chapter is better than the one before."

So, what are the differences between The Chronicles of Narnia books and movies?

The Chronicles of Narnia was most recently adapted, between 2005 and 2010, as a film series. The first two films— The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Prince Caspian— were directed by Andrew Adamson. The third film, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader , was directed by Michael Apted. While there had been plans to make a fourth film, it has since been announced that new adaptations of the films are in the works for Netflix. Here are the major differences between the three most recent film adaptations and the books.

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

While the book only mentions the bombings in London, the movie actually shows the Pevensie children hiding in a shelter.

In the movie, Edmund meets Tumnus when they are both captured by Jadis and sharing a cell. By the time Jadis gets her hands on Edmund in the book, Tumnus has already been turned into stone.

The movie includes a thrilling chase on a frozen river that was simply added to the adventure and does not appear in the novel.

In the movie, the battle of Beruna is shown in much greater detail for a longer period of time. In the book, listeners stay with Susan, Lucy and Aslan, who don't get to the battle until it's nearly over.

The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian

The movie ages up the character of Prince Caspian significantly. In the book, he is only about 13 years old at the beginning of his story (although he ages up later). In the movie, he is a young adult of about Peter's age at the very start.

The movie shows Miraz being crowned king. In the books, Miraz is already king and has been for years — since he secretly murdered his brother, Prince Caspian IX.

Probably in an effort to amp up the action in the movie, a chase scene is added on the way to Dancing Lawn.

The movie also adds more action when the Narnians launch an attack on Miraz's castle. In the book, they consider an attack, but the plan is abandoned.

In the book, Susan never engaged in the battle — it was only Peter, Edmund, and Caspian who fought. Meanwhile, Susan and Lucy stayed with Aslan to help him restore Narnia to its former glory.

A romantic storyline between Caspian and Susan was added to the film. This was never a part of the novel or the series. At the end of the movie, Susan and Caspian kiss, but, again, this moment never happened in the books.

In the movie, before the Pevensies leave Narnia to return to their world, Peter gives Caspian his sword. In the book, Caspian is instead gifted with Susan's horn.

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

The final adaptation of the three probably makes the most changes, but overall the story of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader film remains faithful to the novel.

The biggest change is the quest for the seven swords. Apparently, these swords were all once owned by the Seven Lost Lords, and Caspian is looking for the swords to complete Aslan's table. All of this was made up for the movie. This storyline is not in the book.

In the book, Aslan changes Eustace back from a dragon and then Eustace is able to follow the Dawn Treader. In the movie, however, Eustace remains a dragon until almost the very end.

The encounter with the Slave Trader is different in the book than in the movie as well. In the book, Caspian is sold as a slave and later recognized by one of the seven lords as the king. In the movie, the crew of the Dawn Treader rescues Caspian before anything happens.

In the book, Lucy is tempted by the Book of Incantations when she sees an image of herself as a beauty surpassing that of Susan. In the movie, however, she sees herself as an exact image of Susan.

In the movie, Eustace and Jill Pole are already friends. But in the books, they did not become friends until later. At first, Jill despises Eustace and considers him a bully. It isn't until after he changes during the events of the book that she saw him as a friend.

Edmund's character arc is changed for this movie, perhaps to be more in line with the Edmund viewers would recognize from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. In The Voyager of the Dawn Treader movie, Edmund is tempted by the power of the water to turn objects into gold. In the book, however, Caspian is the one tempted to use the power. Meanwhile, Edmund tries to warn people to stay away from the waters.

The movie seems intent on preserving Caspian's image as a noble king with no temptations to do anything rash or irresponsible. The Caspian of the films decides not to go to The World's End because of his duty as a king. In the novel, however, Aslan forbids Caspian from going to The World's End, and this is the only reason Caspian doesn't go.

Last but not least, the dreaded White Witch makes an appearance in the film version of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader . In the book, she's only briefly mentioned by Lucy.

95+ C.S. Lewis Quotes About Love, Life, Faith, Bravery, and Friendship

From The Chronicles of Narnia, The Four Loves, and more, here are 99 of the best C.S. Lewis quotes that capture the magic of childhood and reflect on life’s mysteries.

The Best Family Audiobooks for All Ages

Listening together is quality time well spent. Perfect for the whole family, these audiobooks are sure to put a smile on the face of everyone: little kids, big kids, and grown-ups alike.

Dream big: meet the all-star cast of "The Sandman: Act II"

With a truly astonishing array of talents, the star-studded cast of The Sandman: Act II is simply unmatched.

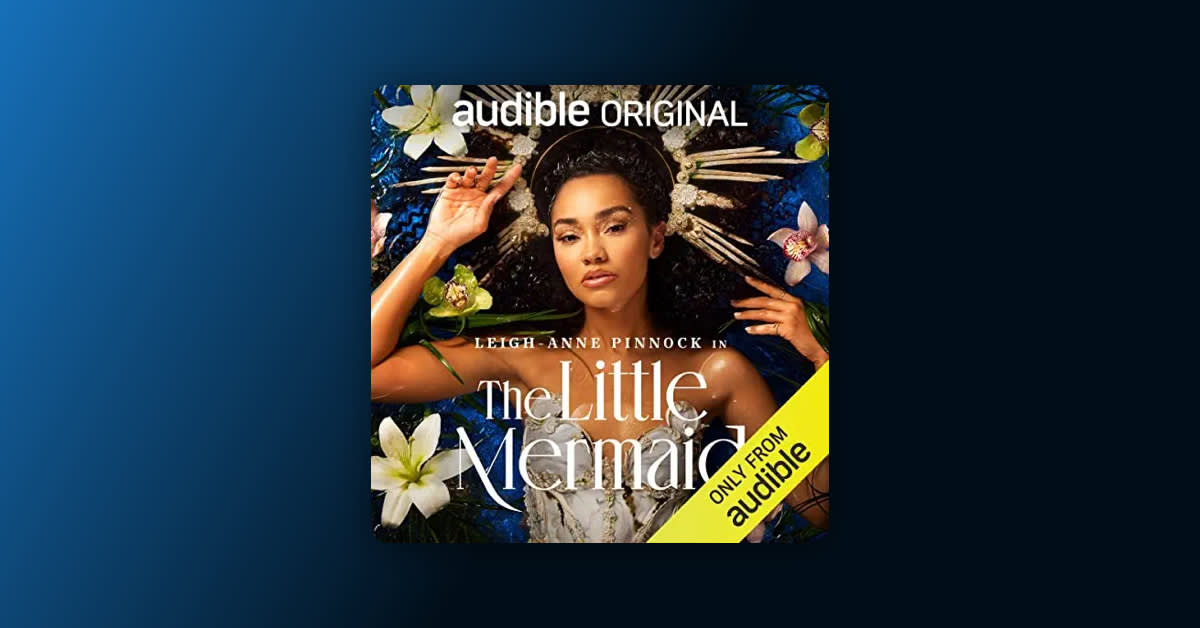

"The Little Mermaid"—dive into the differences among the two Disney films and the original fairy tale

Curious about how the 1989 animated classic and 2023 live-action refresh compare to what Hans Christian Andersen wrote? Read on!

- The Chronicles of Narnia

- Book vs. Film

- Sci-fi & Fantasy

A Summary and Analysis of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by CS Lewis

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe , published in 1950, was the first of the seven Chronicles of Narnia to be published. The book became an almost instant classic, although its author, C. S. Lewis, reportedly destroyed the first draft after he received harsh criticism on it from his friends and fellow fantasy writers, including J. R. R. Tolkien.

How should we analyse The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe : as Christian allegory, as wish-fulfilment fantasy, or as something else? Before we embark on an analysis of the novel, it might be worth briefly recapping the plot.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe : summary

The novel is about four siblings – Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy Pevensie – who are evacuated from London during the Second World War and sent to live with a professor in the English countryside. One day, Lucy discovers that one of the wardrobes in the house contains a portal through to another world, a land covered in snow.

Soon after arriving there, she (quite literally) bumps into a faun (half-man, half-goat) named Mr Tumnus, who takes her to his house and gives her tea while he tells her about the land she has wandered into. Its name is Narnia, and it is always winter (but never Christmas) ever since the White Witch cast a spell over the land. Indeed, Tumnus confesses to Lucy that he should report Lucy’s presence in Narnia to the White Witch, but he can’t bring himself to do it. Instead, he helps her find her way back to the portal so she can return home.

When Lucy gets back and tells her three siblings about her adventure in Narnia, none of them believes her – although Edmund, intrigued, follows her into the wardrobe when she goes back there and finds himself in Narnia, where he meets the White Witch. She gives him Turkish Delight and he tells her about himself and his brother and sisters. She tells him she will make him a prince if he persuades his other siblings to come with him to Narnia.

However, when Edmund talks to Lucy about where they’ve been, and he learns that the White Witch is bad news, he denies that Narnia even exists when Lucy is telling Peter and Susan about it. He accuses her of lying. But eventually all four of them go through the wardrobe into Narnia. When Lucy takes them to visit Mr Tumnus, however, they find that he has been arrested.

The children are befriended by Mr and Mrs Beaver, from whom they learn more information about Narnia. There is a prophecy that when two boys and two girls become Kings and Queens of Narnia, the White Witch will lose her power over the land; this is why the White Witch was so keen to lure the children to Narnia, with Edmund’s help, so she can destroy them and ensure the prophecy does not come true. The Beavers also tell the children that Aslan, the great lion, is on the move, and that he is due to return.

Edmund slips away from them and goes to the White Witch, telling her everything he knows. She takes him to the Stone Table, where Aslan is due to reappear, and orders her servants (wolves) to track down Edmund’s siblings and kill them so the prophecy cannot come true. Mr and Mrs Beaver take the other three children to the Stone Table to meet Aslan.

The snow in Narnia is melting, and Father Christmas appears: proof that the White Witch’s spell over the land is losing its power. Father Christmas gives Lucy, Peter, and Susan presents which will help them in their quest. They arrive at the Stone Table and meet Aslan. The White Witch’s wolf captain Maugrim approaches the camp and attacks Susan, but Peter, armed with the sword Father Christmas gave him, saves his sister and kills the wolf.

The White Witch arrives, and she and Aslan discuss her right to execute Edmund for treason, invoking ‘Deep Magic from the Dawn of Time’. Edmund is spared, but that night the children witness the White Witch putting Aslan to death on the Stone Table. Aslan has gone willingly to his death, in order to save Edmund.

However, the children are surprised and relieved when, the following morning, Aslan comes back to life, citing ‘Deeper Magic from before the Dawn of Time’, which means that a willing victim who sacrificed himself in place of a traitor can be brought back from death. Aslan and the children march to battle against the Witch, with Aslan raising additional troops for his army by breathing on the stone statues in the White Witch’s castle courtyard: traitors she had turned to stone with her magic.

Many years pass. The four Pevensie children have grown into young adults, and have been Kings and Queens of Narnia (reigning jointly) for many years. One day, while they are out hunting the White Stag (which, when caught, can grant wishes), they ride to the lamppost where Lucy first met Mr Tumnus: the location of the portal leading to and from their (and our) world.

Without realising this, the four of them pass through the portal and find themselves back in the wardrobe in the professor’s house. They are children again, as they were before they left all those years ago: time hasn’t passed in our world while they have been away.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe : analysis

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is a classic children’s novel which looks back to both earlier fantasy fiction by Victorian writers like William Morris and George MacDonald (the latter a particular influence on C. S. Lewis) as well as pioneering children’s novels by E. Nesbit.

Indeed, the Pevensie children were partly inspired by Nesbit’s Bastable children, who feature in a series of her novels, including The Story of the Treasure Seekers . Nesbit, however, had also written portal fantasy novels (as had George MacDonald, such as his 1895 novel Lilith ) involving children leaving our world behind for a fantastical other world: see her novel The Magic City , for example.

Say ‘ Chronicles of Narnia ’ or ‘ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe ’ and many people will say, ‘Oh, the C. S. Lewis book(s) that are Christian allegory, right?’

But C. S. Lewis didn’t regard them as allegory: ‘In reality,’ he wrote, Aslan ‘is an invention giving an imaginary answer to the question, “What might Christ become like if there really were a world like Narnia, and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?” This is not allegory at all.’

In short, Lewis rejects the idea that his Narnia books are allegory because, for them to qualify as allegorical, Aslan would have to ‘represent’ Jesus. But he doesn’t: he is Jesus, if Narnia existed and a deity decided to walk among the people of that world. We might think of this as something like the distinction between simile and metaphor: simile is like allegory, because one thing is like something else, whereas in metaphor, one thing is the other thing.

Aslan is not like Jesus (allegory): he is Jesus’ equivalent in Narnia. Perhaps this is a distinction without a difference to many readers, but it’s worth bearing in mind that if anyone should know what allegory is, it’s C. S. Lewis: he wrote a whole scholarly work, The Allegory of Love , about medieval and Renaissance allegory.

Readers might quibble over Lewis’s categorisation here, and decide that what he is outlining is a distinction without a difference (perhaps clouded by his Christianity, and his unwillingness to see his children’s books as ‘mere’ allegory for Christianity, but instead as something more direct and powerful).

But if we stick with mid-twentieth-century fiction and animals for a moment, we can find an example of unequivocal allegory: George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), which we have analysed here . Certainly, there are subtle differences between Orwell’s novel in which animal characters ‘stand in’ for human counterparts, and what Lewis is doing with Aslan in the Chronicles of Narnia .

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is, nevertheless, a novel in which Lewis draws on the Christian story of salvation through a godlike figure (Aslan’s sacrifice on the Stone Table, and subsequent resurrection, are clearly meant to summon the Crucifixion and subsequent Resurrection of Jesus Christ), in order to promote the Christian story. But what if we aren’t ‘sold’ on the Christian aspect of the story? Does the novel’s only value lie in its power as an allegory – or whatever term we might employ instead of allegory?

Part of the reason for the novel’s broader appeal, even in an increasingly secular age, is that it provides escapism and wish-fulfilment aplenty. The whole idea of a portal to another world symbolises the children’s literal escape from a dreary wartime world (where the danger of being bombed during the Blitz has given way to a rather dull life in the countryside with a professor) into a world of crisp snow, magic, and adventure.

Although The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was published five years after the end of the Second World War, children in the early 1950s were still living through a time of rationing and austerity. Even that Turkish Delight that Edmund is given – his thirty pieces of silver to betray his siblings, of course – must have seemed like an almost unattainable treat to Lewis’s original readers.

Even the device with which the novel ends, by which the four children learn that during the years they have spent in Narnia, no time has passed back home, recalls the force of a powerful dream whereby we feel we have ‘lived’ an intense, and intensely long, experience only to wake up and discover it’s only the next morning after all.

5 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by CS Lewis”

Fascinating post. Curious that a modern counterpart Philip Pullman loathes and detests the works of C S Lewis.

Read it as a kid, and remains a favorite. As a kid, I never saw the Jesus connection, it wasn’t until I was an adult that I realized it. I love Turkish delight and can understand why Edmund was so tempted. I enjoyed this post.

I think this story must have combined with The Stream that stood Still and Alice in Wonderland to give me the inspiration for my new “Penny ” books as these are also a portal to another land stories with a time slip. Instead of a Christian background I have an ecological one but hope children will find them just as exciting.”Penny down the Drain” is out now and “Penny and the Poorly Parrot,” ( inspired by the pandemic) will be followed by “Penny and The Creeping Weed.” Amazon seem determined to ignore a self published author but I shall renew my marketing efforts with book 2 after the lockdown.

- Pingback: A Summary and Analysis of Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Selfish Giant’ – Interesting Literature

You’re absolutely right to point out that this isn’t allegory. It is a fictional story featuring Jesus in another world setting which is exactly what Lewis does with the ‘Out of the Silent Planet’ trilogy too – where he attempts to move the traditional Earth-centric ideology of the Christian world into our solar system. How would Christ behave with aliens, is the question Lewis poses there.

Comments are closed.

<script id=”mcjs”>!function(c,h,i,m,p){m=c.createElement(h),p=c.getElementsByTagName(h)[0],m.async=1,m.src=i,p.parentNode.insertBefore(m,p)}(document,”script”,”https://chimpstatic.com/mcjs-connected/js/users/af4361760bc02ab0eff6e60b8/c34d55e4130dd898cc3b7c759.js”);</script>

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Sample details

- Psychology,

- Cinematography

Related Topics

- Rationality

- Uncertainty

- Alfred Hitchcock

Moral Analysis of the Movie Chronicles of Narnia

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is a fable story written by C.S. Lewis in 1950. It is a story about love, family, good, evil and sacrifice, with moral beliefs for readers to learn. The story revolves around the four Pevensie children, Lucy, Peter, Susan, and Edmund, who find themselves in Narnia, a magical world. Lucy, Peter, and Susan live their lives on the path of good and righteousness, while Edmund is lost, angry, and selfish. The evil White Queen seduces Edmund, and he agrees to betray his siblings to the White Queen. However, there is hope, as Aslen the lion has come with his army of good to free the world from the evil White Queen’s rule. Aslen is the centerpiece of the story, representing good, holy, and just. He sacrifices his life to save Edmund’s lost soul and returns to life to finally conquer the White Queen. Edmund understands the evil he has caused and redeems himself, and good triumphs over evil. Despite the fact that the story was not intended to be a Christian fable, it has strong Christian themes and a Christ figure in the character of Aslen the lion.

Moral analysis of the movie Chronicles of Narnia The chronicles of Narnia, the Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe was written by C. S. Lewis in 1950 and remains the best-loved fable of all generations. A fable story of love, family, good, evil and sacrifice with moral beliefs for readers to learn. C. S Lewis’s stepson Douglas Gresham has reported that C.S Lewis did not intend on his story to be a Christian fable. He intended on it just being a moral story, about good and evil, his premise being if the Jesus’ crucifixion had happened in modern day. The main characters are the four Pevensie children, Lucy, Peter, Susan, and Edmund.

Lucy is the youngest and pure of heart, and Peter is the oldest and the leader. Susan is the first oldest, and Edmund is a lost soul. The middle child, he misses his father who is fighting in the war, and resents that he has to obey his older brother. He is selfish, angry and lost.

In Narnia, Lucy, Peter, and Susan live their lives on the path of good and the righteous, while the evil White Queen seduces Edmund (Satan) and agrees to betray his siblings to the White Queen in exchange for sitting on the throne beside her and a lifetime supply of delicious Turkish treats. Lucy, Peter and Susan are told that they are part of a prophecy that says four human children will bring about the end of Winter (Evil) and the White queen’s rule. However, there is hope, Aslen, the lion (Jesus) has come with his army of good to free the world of the evil White queens’ rule. His is the centerpiece of the story representing good, holy, and the just.

Aslen stands for virtue, condemns evil, and is the Christ figure of the piece. He sacrifices his life to the White Queen for Edmund’s lost soul and returns to life to finally conquer the White Queen. Edmund understands the evil he has caused, and redeems himself. He is forgiven and good triumph’s over evil.

- The Chronicles of Narnia- The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis

Cite this page

https://graduateway.com/moral-analysis-of-the-movie-chronicles-of-narnia/

You can get a custom paper by one of our expert writers

Check more samples on your topics

Analysis: the chronicles of narnia.

Introduction The Chronicles of Narnia is a series written by C.S. Lewis between 1949 and 1954. The series revolves around the fantasy adventure of a group of children (primarily the Pevensie siblings Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy), transported from this earth, to a magical world called Narnia. In Narnia, animals talk and mythical creatures such as

Analysis of the Literary Elements on the Prince Caspian, the Narnia Chronicles

In The Magician’s Nephew, Lewis employs a third person omniscient perspective or third person limited omniscient perspective. Although the narrator is not a participant in the story, they do address the reader at various points. This narrator has access to the thoughts and emotions of Digory and Polly, particularly Digory's feelings of sadness, hope, and

Chronicles of Narnia: Assignment

Christianity

They are home at the professor's house, then they go to Marina through the wardrobe and at last they are home at the professor's house again. Actinic model: Helper. Subject. Opponent Sender D .Object. Receiver Helper = Tumulus, the beavers and Aslant Subject = The Penknives Opponent = The white witch Sender = Aslant Object =

Hero’s Journey “The Chronicles of Narnia”

Hero'S Journey

In The Chronicles of Narnia, the ordinary world is the kids treating Lucy like she is a baby. Lucy knows she is more mature than what they say about her. She isn’t treated good by her brother Edmund. The call to adventure is when Lucy is looking for a place to hide while she is

“Chronicles of Immigrants” by Peter Skshinetsky

‘An individual’s interaction with others and the world around them can limit or enrich their experience of belonging. ’ Belonging is central to how we define ourselves: our belonging to or connection emerges from interaction with people and places. Belonging is a distinct identity characterised by affiliation, acceptance and association. Belonging is shaped by personal,

‘The Martian Chronicles”

Al Bundy faced the problem of finding out who's land was who's when his neighbor and him got into an argument over an apple tree. He called in a surveyor and they found out the tree belonged to Marcy, his neighbor, and Al became jealous. Al and his family then electricuted Marcy. Marcy retaliated when

Hope in Chronicles Essay

Hope in Chronicles It is only Monday and anxiety and fear have been the theme of the day. I wish I could tell you that I have been a stoic follower of Christ with no fear of tomorrow but this has not been the case. As COVID-19 has been the revolving news for what feels way

Moral Relativism Is a Moral and Value Position

Cannibalism, what do you believe of it? Is it morally rectify? Does the theory of ethical relativism support it or does it strike hard it down? Throughout this paper I am traveling to measure the pros and cons of ethical relativism for a instance refering cannibalism. An American adult male by the name of Daniel

Moral Conscience in tne Movie “A Man for All Seasons”

Conscience is the act of recognizing the moral quality of a specific action through reason. This concept is exemplified by Thomas More in the film A Man for All Seasons, where he consistently displays his strong moral conscience. Despite living in a time marked by hedonism, materialism, and corruption, Thomas remains steadfast in his commitment

Hi, my name is Amy 👋

In case you can't find a relevant example, our professional writers are ready to help you write a unique paper. Just talk to our smart assistant Amy and she'll connect you with the best match.

The Chronicles of Narnia

Narnia…. a land of fantasy and adventure where magic and a Great Lion prevail. A land where so many people wish to be, a land from start to finish in The Chronicles of Narnia. Seven books written by Clive Staples Lewis have proven to be the most enchanting and mesmerizing books of all time. Pure beauty and amazing imagery allows the reader to become an explorer of Narnia and take part in the fascinating adventures bound to happen. Readers become one with the pages, not wanting to put the book down for fear of the wonderful land of Narnia escaping their minds.

Not wanting to lose the joy and bliss as the words flow, page after page, book after book. The Chronicles of Narnia were first written by C. S. Lewis with children in mind. Easy dialogue and a sense of reality in the fantasy setting allows all ages to enjoy and fall in love with these books. The adventure begins with The Magicians Nephew. The reader is introduced to Digory Kirke and Polly Plumer. Digorys Uncle Andrew, a mad magician, doesnt fully understand the magic that he is dealing with. Andrew was given four rings when he was a child and when he received them, was ordered to throw them away and never think of them again. He didnt do so.