Plan International's websites

Find the Plan International website you are looking for in this list

- Case Studies

7 short child marriage stories

These child marriage stories show how and why Plan International is working to prevent early marriage and reveal the effect our work is having on girls’ lives.

Because I am a girl – I’ll take it from here

Our award-winning stop-motion film shows how education can transform girls’ lives. Education is one of the biggest factors in preventing child marriage. An educated girl is more likely to marry later, have fewer children, earn more money, invest in her children and become a force for change in society.

It’s my life – girls say no to child marriage in Africa

In sub-Saharan Africa around 7 million girls live as child brides. Parents marry off their daughters due to poverty, tradition and gender inequality. See how children’s groups set up by Plan International are spreading the message about the value of educating girls and the negative aspects of early marriage.

No mountain too high – ending child marriage in Nepal

15-year-old Maya was forced to drop out of school following her marriage. Plan International’s mobile outreach team helped her get back to school despite being unable to access Maya’s village by road.

13, and a bride

In Dosso, Niger, 13-year-old Mariama discovered that she was to be married in a few days’ time. In one of Plan International’s most watched child marriage stories, see how cultural and financial factors played a role in her mother’s decision to accept a dowry for her marriage and how Plan International works at multiple levels to educate communities about the consequences of child marriage.

Lamana’s story

Child marriage exposes girls to abuse, exploitation and early pregnancy. When Lamana was 15, this became her reality. See how Plan International worked alongside a local partner organisation to help her regain confidence, return to education and change her life.

12-year-old Thea’s wedding to 37-year-old Geir

Child marriage is most common in South Asia and West and Central Africa but how would people react to a child marriage taking place in Europe? Plan International Norway created a blog by 12-year-old Thea, who revealed she was marrying a 37-year-old man named Geir and the story soon went viral. This video shows what happened on the wedding day.

Wedding Busters: Child marriage free zones in Bangladesh

66% of girls in Bangladesh are married under 18. See how Plan International works alongside a local children’s organisation to create ‘child marriage-free zones’ to stop early marriage.

Education, Emergencies, Protection from violence, Sexual and reproductive health and rights, child marriage, Child protection in emergencies, Gender-based violence

Related pages

From school leavers to star teachers , salma is determined to stay in school – no matter what.

Water helps a community to grow and thrive

Cookie preferences updated. Close

Unchained At Last

UN-Arrange a Marriage … RE-Arrange a Life

United States’ Child Marriage Problem: Study Findings (April 2021)

Also see our article in the journal of adolescent health, view as pdf.

The United States has a child marriage problem – but a simple solution is available.

Nearly 300,000 minors, under age 18, were legally married in the U.S. between 2000 and 2018, this study found. A few were as young as 10, though nearly all were age 16 or 17. Most were girls wed to adult men an average of four years older.

Child marriage – or marriage before age 18 – is dangerous. Even at age 16 or 17, regardless of spousal age difference, child marriage:

1. Can easily be forced marriage, since minors have limited legal rights with which to escape an unwanted marriage (typically they are not even allowed to file for divorce);

2. Is a human rights abuse that produces devastating, lifelong repercussions for American girls, destroying their health, education, economic opportunities and quality of life; and

3. Undermines statutory rape laws, often covering up what would otherwise be considered a sex crime. Some 60,000 marriages since 2000 occurred at an age or spousal age difference that should have been considered a sex crime.

Table of Contents

Methodology, implications, policy failures, policy recommendations, appendix a: acknowledgments, appendix b: methodology categories, appendix c: marriage age by state.

Unlike in countries where child marriage is illegal but persists anyway, the problem in the U.S. is the laws themselves. Most U.S. states still allow marriage before 18, and the four states* that banned it did so only in the last three years.

Federal law, too, allows and might even encourage child marriage. Immigration law does not specify a minimum age to petition for a foreign spouse or fiancé(e) or to be the beneficiary of a spousal or fiancé(e) visa, which allows for American girls to be trafficked for their citizenship and allows for children around the world to be trafficked to the U.S. under the guise of marriage. The U.S. approved nearly 9,000 petitions involving a minor between 2007 and 2017, and in 95% of them, the younger party was a girl. Further, the federal criminal code prohibits sex with a child age 12 to 15 but specifically exempts those who first marry the child. This incentivizes child marriage and implicitly endorses child rape.

Legislation to this effect harms no one except child rapists, costs nothing and protects children from a human rights abuse.

Unchained At Last first realized in 2015 that the U.S. has a child marriage problem. Unchained had been founded in 2011 by a forced marriage survivor with a mission of providing free legal and social services to help individuals in the U.S. to escape forced marriages – but more and more girls, under age 18, were reaching out to Unchained to plead for the same help.

At the time, child marriage was legal in all 50 U.S. states, a fact that seemed lost on policymakers and advocates. Yet there is almost nothing Unchained can do to help a girl who is not yet 18 to escape a forced marriage. Even a day before her 18th birthday, a girl in the U.S. typically cannot leave home, enter a domestic violence shelter or even file for divorce.

Unchained launched a national movement to end child marriage with an op-ed article in the New York Times titled “America’s Child-Marriage Problem” [1] . Since then, Unchained and its allies have formed a National Coalition to End Child Marriage and various state coalitions, worked with state and federal legislators on simple policy solutions and studied and raised awareness of child marriage in the U.S.

Still, many Americans remain unaware of the prevalence of child marriage in the U.S. [2], possibly because of significant data deficiencies. No central repository collects national marriage-age data in the U.S., and some states do not track this information or make it available.

This is the first study of the extent of child marriage in the U.S. that collected all available state data and used various estimation methods, based on high correlations identified between the available data and census data, to fill in the data gaps. (Unchained’s previous study of the extent of child marriage in the U.S. for the period 2000 to 2010 was based on available data from 38 states plus estimates for the other 12 states based only on state population [3]. PBS Frontline later extended that study to 2015 but did not attempt to fill in the many data gaps left by states that provided no data or only some data [4] ).

Unchained led the study, which was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Unchained partnered with McGill University, Quest Research & Investigations, Quantitative Analysis and others. (See Appendix A for a full list of Unchained’s partners for this study.)

Unchained requested marriage-age data, based on marriage certificates, from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Specifically, Unchained asked for de-identified data on the ages and genders of all people married in the state, along with their spouse’s age and gender, in each year since 2000.

Full Data (32 States)

Unchained retrieved marriage-certificate (or, in some states, marriage-license) data from 32 states that showed the age or age ranges of all individuals married each year between 2000 and 2018. For those states, Unchained analyzed the data to determine how many individuals married before age 18. (A few states provided data for 2019 and part of 2020 as well, but Unchained did not include those years in its national calculations.)

Note that Unchained counted children married, not child marriages. Thus, if a minor married another minor, Unchained counted that as two.

Some states provided data that conflicted with data they previously had provided to Unchained. For those states, Unchained used the newer data, on the assumption that the states had found and corrected errors.

Some states’ data included obvious gaps that mean Unchained’s findings are almost certainly an undercount. For example, Tennessee withheld all counts less than 10 (such as if nine 17-year-olds married 20-year-olds one year), potentially hiding thousands of additional child marriages, and Ohio randomly and irretrievably deleted data on children married before age 15 in most years. Additionally, some states’ data included nonsensical marriage ages, such as three-digit numbers, that Unchained excluded from its analysis.

Unchained confirmed all outliers in the data – that is, children listed as married before age 12 – by contacting the relevant state.

Partial Data (12 States + D.C.)

For 10 states and the District of Columbia, Unchained retrieved marriage-age data for some or most of the years 2000 to 2018. Since the number of children married in each state was highly correlated across years – the correlation ranged from .93 to .99 – Unchained used each of those states’ available data to estimate numbers for the missing years.

For two additional states (Nevada and Arizona), Unchained retrieved full marriage-age data from one county or a pair of counties that represented at least two-thirds of the state population.

No Data (6 States)

To estimate data for the remaining six states and the remaining sections of Nevada and Arizona, Unchained looked for correlations between available marriage-age data in other states and variables in the American Community Survey, the U.S. Census Bureau’s demographics survey program. Unchained identified a strong correlation of .88 with a combination of two ACS variables: already-married individuals age 15 to 17 (they self-reported as married, divorced, widowed or separated) and divorced or separated individuals age 18 to 24. (See Appendix B for a breakdown of which states fit into each methodology category.)

An estimated 297,033 children were married in the U.S. between 2000 and 2018. That number includes 232,474 based on actual data plus 64,559 based on estimates.

Child marriage occurred most frequently among 16- and 17-year olds. Some 96% of the children wed were age 16 or 17, though a few were as young as 10 [5].

10-Year-Olds: 5 (<1%) 11-Year-Olds: 1 (<1%) 12-Year-Olds: 14 (<1%) 13-Year-Olds: 78 (<1%) 14-Year-Olds: 1,223 (<1%) 15-Year-Olds: 8,199 (4%) 16-Year-Olds: 63,956 (29%) 17-Year-Olds: 148,944 (67%)

Child marriage is much more likely to impact girls than boys. Some 86% of the children who married were girls – and most were wed to adult men (age 18 or older) [6]. Further, when girls married, their average spousal age difference was four years, whereas when boys married, their average spousal age difference was less than half that: 1.5 years [7].

Child marriage often covers up child rape. Some 60,000 marriages since 2000 occurred at an age or spousal age difference that should have been considered a sex crime [8].

In about 88% of those marriages, the marriage license became a “get out of jail free” card for a would-be rapist under state law that specifically allowed within marriage what would otherwise be considered statutory rape.

In the other 12% of those marriages, the state sent a child home to be raped. The marriage was legal under state law, but sex within the marriage was a crime.

The 10 states with the highest per-capita rates of child marriage [9] are :

1. Nevada (0.671%) 2. Idaho (0.338%) 3. Arkansas (0.295%) 4. Kentucky (0.262%) 5. Oklahoma (0.229%) 6. Wyoming (0.227%) 7. Utah (0.208%) 8. Alabama (0.195%) 9. West Virginia (0.193%) 10. Mississippi (0.182%)

The national number of children married decreased almost every year but is unlikely to get to zero without legislative intervention.

Policymakers should be deeply concerned about child marriage – including at age 16 or 17 – for three main reasons:

1. Child marriage can easily be forced marriage.

Minors, even highly mature 16- or 17-year-olds, do not have the legal rights they need to navigate a contract as serious as marriage.

Leaving home : Minors who leave home to escape from an abusive spouse or impending forced marriage are typically considered runaways under state law. Police might return them to their homes against their will; in some states, minors can be charged with a status offense for running away. Police might even arrest an advocate at Unchained who helped a minor leave home.

Entering a shelter : A minor who manages to run away from a forced marriage probably has nowhere to go, since Unchained has found that most domestic violence shelters do not accept unaccompanied minors. Youth shelters are not a solution: They typically notify parents their children are there, and house children only for about 21 days while they work on a reunification plan.

Retaining an attorney : Contracts with children, including retainer agreements with attorneys, usually are voidable under state law. Only the most generous attorneys would agree to represent a child.

Filing for divorce : Perhaps most shockingly, children typically are not allowed to initiate a legal proceeding – such as seeking a protective order or filing for divorce – unless they act through a guardian or other representative, under state law.

Some states have tried to close these legal traps by automatically emancipating minors upon their marriage. However, such emancipation arrives too late to prevent a child from being forced to marry; the child must undergo the trauma of the forced marriage before getting the limited legal rights that emancipation brings. And an emancipated minor’s rights are limited: Such a minor still might face difficulties leaving home, entering a shelter or taking other steps to escape an unwanted marriage. Further, automatic emancipation likely ends parents’ financial obligation to their child, regardless of the child’s financial situation. Unchained has seen such teens end up homeless after their marriage failed and their parents refused to allow them back home.

When children reach out to Unchained to ask for help escaping a forced marriage and learn about their limited options, many despair and turn to suicide attempts. Death seems like the only way out for them.

2. Child marriage is a human rights abuse that destroys American girls’ lives.

Marriage before 18, including at 16 or 17, is a human rights abuse, according to the U.S. State Department [10]. It produces devastating, lifelong repercussions for American girls, destroying their education [11], economic opportunities [12] and health [13]. It significantly increases a woman’s risk of experiencing domestic violence [14]. It almost always ends in divorce [15].

Much less is known about the impact of child marriage on American boys. Since most of the children who marry in the U.S. are girls, the research on the impacts of child marriage has been focused on girls.

3. Child marriage undermines statutory rape laws.

In most states and under federal law [16], sex with a child that would otherwise be considered rape – in some cases, felony rape – becomes legal within marriage. In those situations, the marriage license becomes a “get out of jail free” card for a child rapist.

In some states, statutory rape remains a crime within marriage. The marriage is legal, but sex within the marriage is rape. In those situations, the state that issues the marriage license sends a child home to be raped.

As this study showed, 60,000 marriages since 2000 occurred at an age or spousal age difference that should have been considered a sex crime – and 88% gave a rapist a “get out of jail free” card, while 12% sent a child home to be raped. Either way, the state made a mockery of its statutory rape laws.

Child marriage brings no benefit, other than to child rapists. A mature 17-year-old who is in love and wants to marry can wait a matter of months to marry without suffering any harm. A teen couple that gets pregnant can easily co-parent outside of marriage until they are both 18 (establishing paternity is a simple process in most states). A child who is in an abusive home deserves resources and options that do not involve entering a contractual sexual relationship.

Unlike in countries such as India, where child marriage is illegal but remains stubbornly widespread due to other factors, the problem in the U.S. is the laws themselves. The nearly 300,000 children wed in the U.S. between 2000 and 2018 all were married legally.

Each U.S. state sets its own marriage age. While most states set it at 18, legal loopholes in most states still allow children to marry, typically with nothing more than a parent’s signature on a form (parental “consent” that is often actually parental “coercion” [17] ) and/or a court’s approval (often a rubber stamp [18] ). Five states’ laws still specifically allow pregnant girls to marry,* a loophole that has been used to cover up rape and force girls to marry their rapist [19].

Federal law, too, allows and might even encourage child marriage. The Immigration and Nationality Act does not specify any minimum age to petition for a foreign spouse or fiancé(e) or to be the beneficiary of a spousal or fiancé(e) visa [22] . This creates a significant incentive to force a child to marry a foreign adult who wants a U.S. visa, and it invites the trafficking of children to the U.S. under the guise of marriage.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services approved 8,868 petitions involving minors for spousal or fiancé(e) entry into the U.S. between 2007 and 2017. The younger party was a girl in 95% of the petitions [23] .

Additionally, the federal criminal code, which prohibits sex with a child age 12 to 15, specifically exempts those who first marry the child*** [24] . Refusing to punish child rapists who first marry the child encourages both child marriage and child rape.

Four states and two territories have passed legislation to end all marriage before 18, without exceptions: Delaware [25] , New Jersey [26] , Pennsylvania [27] and Minnesota [28] , as well as American Samoa [29] and U.S. Virgin Islands**** [30]. (Puerto Rico banned marriage before age 18 in 2020 [31]. However, the age of adulthood in Puerto Rico is 21, so Puerto Rico cannot end child marriage unless it sets the marriage age at 21 or lowers the age of adulthood to 18.)

But other states have rejected or watered down legislation to end child marriage, in some cases eliminating one loophole only to introduce a new one, and some states have not acted at all. Bills to eliminate child marriage currently are pending in 12 states, but some have stalled.

Federal legislation to set a minimum age of 18 to remove marriage-related immigration benefits, except Violence Against Women Act self-petitions, for those under 18, was introduced in 2019 but did not get enough support to move [32].

The U.S. is one of 193 countries that have pledged, under the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (specifically, SDG 5.3) to end child marriage by year 2030 to help achieve gender equality [33]. The U.S. and the world will not be able to keep this promise if legislators do not act now.

Every U.S. state, territory and district must pass simple, commonsense legislation to eliminate any legal loophole that allows marriage before age 18 (or higher, in the three states where the age of adulthood is higher [34] ).

Unchained’s partners for this study included:

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, whose generosity made the study possible through a one-year grant;

- McGill University, which conducted the data analyses regarding statutory rape and spousal-age differences;

- Quest Research & Investigations, which conducted most of the data collection and analysis on a “ low bono ” basis;

- Kroll, which conducted some initial data collection on a pro bono basis;

- Quantitative Analysis, which estimated the data where actual data was unavailable on a pro bono basis;

- J Strategies, which helped publicize the study findings;

- White & Case, which conducted the state-by-state legal research on which some the analysis was based on a pro bono basis;

- TrustLaw, which arranged the “match” between Unchained and White & Case;

- DLA Piper, which conducted legal research on a pro bono basis;

- Morgan Lewis, which conducted legal research on a pro bono basis; and

- DOSIDO Design, which created infographics to illustrate the study’s findings.

*Clark County, Nevada, data also was missing the year 2000. Unchained estimated for that year as it did for states whose data missed one or more years.

The youngest age* at which one may marry in each state [35]:

[1] Fraidy Reiss, America’s Child-Marriage Problem, New York Times (13 October 2015), https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/14/opinion/americas-child-marriage-problem.html .

[2] David Lawson et al., What Does the American Public Know About Child Marriage?, PLoS ONE (23 September 2020), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238346 .

[3] Fraidy Reiss, Why Can 12-Year-Olds Still Get Married in the United States?, Washington Post (10 February 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2017/02/10/why-does-the-united-states-still-let-12-year-old-girls-get-married .

[4] Anjali Tsui et al., Child Marriage in America, PBS Frontline (6 July 2017), http://apps.frontline.org/child-marriage-by-the-numbers .

[5] Numbers and percentages based on children wed for whom age data were available (actual data only, excluding estimates).

[6] Percentages are based on children wed for whom spousal age and gender data were available (actual data only, excluding estimates).

[7] Calculations of spousal age differences are based on McGill University’s analysis of Unchained’s data (actual data only, excluding estimates) in 43 states.

[8] McGill University’s analysis of Unchained’s data found 34,943 to 40,224 marriages since 2000 occurred at an age or with a spousal age difference that should have constituted a sex crime under the relevant state’s law. In some 80%, sex became legal within marriage; in the other 20%, sex within the marriage was a crime. Unchained added to the analysis the estimated 23,588 children married in California between 2000 and 2018, all of whom fit in the first category.

[9] Per-capita comparison is based on actual and estimated data.

[10] U.S. Department of State, et al., United States Global Strategy to Empower Adolescent Girls (March 2016), https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/254904.pdf .

[11] Vivian Hamilton, The Age of Marital Capacity: Reconsidering Recognition of Adolescent Marriage , William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository (2012), http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2467&context=facpubs .

[12] Gordon Dahl, Early Teen Marriage and Future Poverty, The National Bureau of Economic Research (May 2005), http://www.nber.org/papers/w11328.pdf .

[13] Yann Le Strat, Caroline Dubertret, Bernard Le Foll, Child Marriage in the United States and Its Association With Mental Health in Women, Pediatrics: Official Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics (24 August 2011), http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2011/08/24/peds.2011-0961.full.pdf .

[14] World Policy Analysis Center, Fact Sheet (March 2015), https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/WORLD_Fact_Sheet_Legal_Protection_Against_Child_Marriage_2015.pdf .

[15] Vivian Hamilton, The Age of Marital Capacity: Reconsidering Recognition of Adolescent Marriage , William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository (2012), http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2467&context=facpubs .

[16] 18 U.S.C. § 2243 calls for up to 15 years in prison and/or a fine for someone who has sex with a child age 12 to 15, if the child is at least four years younger.

[17] In Unchained’s experience, even when a minor shows up sobbing at the clerk’s office while their parents force them to marry, the clerk is unwilling or unable to intervene.

[18] In Unchained’s experience, minors being forced to marry are too scared to tell the judge about it. Additionally, this study shows judges across the U.S. have approved marriages for children who are too young to consent to sex. Further indication that judges are not paying close attention is a report that showed Massachusetts probate judges approved 92% of child marriage petitions between 2010 and 2014. See Jim Morrison, Advocates Raise Concerns About Child Marriage in Mass. , Boston Globe (10 August 2016), https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/08/10/advocates-raise-concerns-about-child-marriage/sx4TQNbXp4gimy502yWB4L/story.html .

[19] The five states with a pregnancy exception to the marriage age are Arkansas (Arkansas Code Annotated § 9-11-103), Maryland (Maryland Family Law Code Ann. § 2-301), New Mexico (New Mexico Code § 40-1-6), North Carolina (North Carolina General Statutes § 51-2.1) and Oklahoma (Oklahoma Statutes Ann. § 43-3). For an example of how pregnancy loopholes have been used to cover up rape and force girls to marry their rapist, see: Nicholas Kristof, 11 Years Old, a Mom, and Pushed to Marry Her Rapist in Florida, New York Times (26 May 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/26/opinion/sunday/it-was-forced-on-me-child-marriage-in-the-us.html . (CORRECTION: A previous version of this study said that four states as of April 2021 included a pregnancy exception to the marriage age, which excluded Arkansas. This was corrected as of April 2022.) * NOTE* After this study was completed, North Carolina changed its laws, reducing to four the number of states with a pregnancy exception to the marriage age: Arkansas, Maryland, New Mexico and Oklahoma.

[20] Puerto Rico banned marriage before age 18 in 2020 with PC1564. See https://sutra.oslpr.org/osl/esutra/MedidaReg.aspx?rid=124126 . However, the age of adulthood in Puerto Rico is 21, so Puerto Rico cannot end child marriage unless it sets the marriage age at 21 or lowers the age of adulthood to 18. *NOTE* After this study was completed, Rhode Island, New York, Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut, Michigan, Washington and Virginia ended child marriage. Now child marriage is legal in 38 states, and four states do not specify a minimum marriage age.

[21] The 10 states whose laws do not specify any minimum age for marriage are California, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Washington, West Virginia and Wyoming. *NOTE* After this study was completed, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Michigan and Washington, which previously did not specify a minimum age for marriage, ended child marriage. Additionally, Wyoming and West Virginia raised their age to 16 from 0. Currently, four states’ laws do not specify a minimum marriage age: California, Mississippi, New Mexico and Oklahoma.

[22] 8 U.S.C. § 1101.

[23] U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, How the U.S. Immigration System Encourages Child Marriages (11 January 2019), https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Child%20Marriage%20staff%20report%201%209%202019%20EMBARGOED.pdf .

[24] 18 U.S.C. § 2243 calls for up to 15 years in prison and/or a fine for someone who has sex with a child age 12 to 15, if the child is at least four years younger. *NOTE* The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2022 — which President Biden signed into law in March 2022 — eliminated this marriage defense to statutory rape. However, another marriage defense to statutory rape remains in the federal code under 10 U.S.C. § 920b.

[25] HB337 (2018). https://legis.delaware.gov/BillDetail?LegislationId=26363 .

[26] S427 (2018). https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2018/Bills/AL18/42_.HTM .

[27] HB360 (2020). https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/billInfo/billInfo.cfm?sYear=2019&sInd=0&body=H&type=B&bn=0360 .

[28] HF745 (2020). https://www.revisor.mn.gov/bills/bill.php?f=HF745&y=2019&ssn=0&b=house .

[29] HB35-28 (2018). Not available online.

[30] Bill No. 33-109 (2020). https://www.legvi.org/billtracking/Detail.aspx?docentry=27003 .

[31] PC1564 (2020). https://sutra.oslpr.org/osl/esutra/MedidaReg.aspx?rid=124126 .

[32] S.742/H.R.1738: Protecting Children Through Eliminating Visa Loopholes Act (2019-2020). https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/742/text and https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1738/all-info .

[33] United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 is to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.” One aspect of that, Goal 5.3, is to “eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation.” https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5 .

[34] The age of adulthood is 19 in Alabama (Code of Alabama, Title 26, Chapter 1, § 26-1-1); 21 in Mississippi (Mississippi Code Ann. § 1-3-27); and 19 in Nebraska (Nebraska Code § 43-2101).

[35] Marriage age is based solely on statute, not on case law. *NOTE* After this study was completed, Rhode Island, New York, Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut, Michigan, Washington and Virginia ended child marriage. (The youngest marriage age allowed in those states is now 18.) Additionally, North Carolina and Alaska raised their marriage age to 16 from 14, Maryland raised its age to 17 from 15, Maine raised its age to 17 from 16, and Wyoming and West Virginia raised their age to 16 from 0.

© 2021 Unchained At Last

Legislative information on this page is accurate as of April 2021.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Goats and Soda

- Infectious Disease

- Development

- Women & Girls

- Coronavirus FAQ

Child grooms are often overlooked in the fight to stop child marriage

Photos and text by Stephanie Sinclair

Married at 15, Chakraman Shreshta Balami fulfilled his dying father's wish by getting married — at age 15. He had to give up his dream of becoming a doctor. Now the vice principal of Sri Bhavani government school, he campaigns against child marriage — but even his son was married as a teenager. Above, he poses with a grandchild. Stephanie Sinclair for NPR hide caption

Married at 15, Chakraman Shreshta Balami fulfilled his dying father's wish by getting married — at age 15. He had to give up his dream of becoming a doctor. Now the vice principal of Sri Bhavani government school, he campaigns against child marriage — but even his son was married as a teenager. Above, he poses with a grandchild.

The teenager dreamed of becoming a doctor. But that dream was derailed by child marriage. It's a familiar story – but in this case the details may surprise you.

The 15-year-old wasn't a child bride. He was a child groom.

Child marriage – defined by the United Nations as marriage under age 18 and considered a violation of human rights – disproportionally impacts girls. An estimated 650 million girls and women were married as children.

But there are also child grooms. In its first ever in-depth analysis of child grooms, published in 2019, UNICEF estimates 115 million boys and men around the world were married as children .

They too suffer because of young marriage. "Child grooms are forced to take on adult responsibilities for which they may not be ready," says UNICEF executive director Henrietta Fore . "Early marriage brings early fatherhood and with it added pressure to provide for a family, cutting short education and job opportunities."

Bishal and Sita, both 17, with their 18-month-old daughter Manisha, at his family's home in Kigati village in Nepal. A UNICEF study using data from 82 countries estimates that 115 million boys and men around the world married as children. Child marriage among boys is prevalent in a range of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific. Stephanie Sinclair for NPR hide caption

In addition to perpetuating the cycle of poverty, child marriage has a powerful psychological impact. Based on what he's seen, Pashupati Mahat , technical director and senior clinical psychologist for the Center for Mental Health and Counselling – Nepal , says that boys forced into child marriage suffer higher rates of depression, loneliness and even suicide than do child brides.

"Young men force themselves to be adults, but they don't have the psychological resources to cope with all the demands," says Mahat. "There is more isolation, alienation and a lot of psychological pain within themselves. They are not skilled enough to provide the good affectionate, emotional support [and] use a punitive parenting style. They don't want to face the difficult emotions of the child because they never got the opportunity to deal with their own emotional difficulties when they were quite young."

A would-be doctor derailed

The teenager who wanted to be a doctor, Chakraman Balami, lives in Nepal, which ranks among the countries with the highest rates of marriages involving a child groom. That rate is estimated by UNICEF at 1 in 10. The highest rates are in Central African Republic (28%) and Nicaragua (19%).

The practice of child marriage persists in Nepal despite the fact that it's been illegal since 1963. Current law sets the minimum age of marriage at 20 for both men and women. However, it's rarely enforced.

Now an adult, Balami has become an activist against child marriage. And in 2022, his mission is still a challenge.

The cultural forces that lead to child marriage have not diminished. In Nepal as in many other countries, the practice is part of longstanding tradition. And families may see little advantage to keeping their youth in a classroom when they're so desperately needed elsewhere.

Students at the Sri Bhavani government school in Nepal. Economic pressures cause many families to pull their children out of school. Stephanie Sinclair for NPR hide caption

Students at the Sri Bhavani government school in Nepal. Economic pressures cause many families to pull their children out of school.

"In the village, the parents who want their kids to marry, they see only immediate benefits," explained Chakraman. "They see free labor, they see one more person able to take care of the household chores, food, field, agriculture." At the same time, they do not consider the harmful repercussions of child marriage.

The pandemic has made matters worse. UNICEF predicts that an additional 10 million girls are at risk of marriage over the next decade as a result of economic repercussions caused by COVID-19.

In Nepal, for example, where on-and-off lockdowns have decimated the ability of farmers to earn a living, parents are eager to marry off their children to have one less mouth to feed. Both girls and boys are affected .

Initial data from the pandemic period shows that boys as well as now facing a greater risk of marriage: In Balami's village of Kagati, 9 underage girls were married in 2020, compared to 7 the year before, and three teenage boys were wed, while there were no child grooms in 2019.

From top student to unwilling groom

Before he became a groom at age 15, Chakraman was a top student at his secondary school near Kathmandu with no interest in early marriage.

But when he was around 13, his father became critically ill. His dying wish? To see his son get married.

"I felt very bad," says Chakraman. "But I respected my parents. I listened to them. I wanted to fulfill their wishes." So in 1993, he reluctantly agreed to marry at age 15, shortly before his father's death. "People have a mindset, a belief system that if you arrange your son's marriage or if you see your son getting married, then your life will be fulfilled."

Barely an adult, Chakraman became a father at 18 — but the baby died just five days later, leaving the young couple heartbroken. The couple subsequently had two children. The funds he would have invested in his education went toward providing for the youngsters.

So his dream of medical school was not to be. "When somebody's dreams are taken away, you get emotionally hurt, you get affected," says Chakraman. "I have a lot of anger when I think of the life I never got to make for myself."

Married at just 15, Chakraman Shreshta Balami, vice principal of Sri Bhavani government school, encourages his students to remain in school — and not marry at a young age. Stephanie Sinclair for NPR hide caption

Married at just 15, Chakraman Shreshta Balami, vice principal of Sri Bhavani government school, encourages his students to remain in school — and not marry at a young age.

Child marriages traditionally take place in this area around the Mahalaxmi temple. Advocates are trying to stop the practice but face many obstacles — including fears among parents who push for teen marriage, worried that a daughter in a relationship could become pregnant while unwed. Stephanie Sinclair for NPR hide caption

Child marriages traditionally take place in this area around the Mahalaxmi temple. Advocates are trying to stop the practice but face many obstacles — including fears among parents who push for teen marriage, worried that a daughter in a relationship could become pregnant while unwed.

But he did persevere to complete his education over a span of 20 years. He recently earned a master's degree in Education Planning Management. These days, Chakraman is the vice principal of Shree Bhawani Primary and Secondary Schools.

While his own dreams of medical school have faded, he hasn't given up on those of his students. He encourages them to finish their studies before considering marriage. It's been a decades-long fight.

But the group's best arguments have a hard time overcoming long-held traditions, economic challenges and family pressures. Child marriage has continued into the next generation. Even Chakraman's own son and niece would ultimately marry before they reached adulthood.

Even in communities more amenable to delaying marriage, when adolescents begin romantic relationships, parents may push for child marriage as they worry about premarital pregnancy bringing shame to families.

Why it's so hard to stop child marriage in Nepal

Chakraman understands all too well how hard it is to stop this practice.

Not long after his own wedding, he and more than 40 of his male teenage friends – all of whom were married or engaged as children – formed the youth organization Mahalaxmi Janajagriti Yuba Pariwar, which translates to Mahalaxmi Awareness Youth Club. The volunteer group was named after the temple where these marriages take place and was aimed at preventing their neighbors and relatives from facing the same fate. "Whenever we heard about a child marriage, we would try to convince parents and family members to stop it. If they didn't listen, we went to the bride and groom," he explained. "If that still didn't work, [we would] smash all pots of alcohol they make at home for the wedding feast."

The plan backfired. Villagers viewed the activists as disobedient, blaming their rebellious behaviors on their education and consequent exposure to ideas outside the social norm. The backlash even led some families to briefly question sending their children to school at all. The youth group eventually turned to less extreme methods, focusing on peer support and training to achieve its goals.

Chakraman has also been unable to forestall child marriage in his own family. Along with several other teen couples, his niece Sumeena was married at age 13 on the festival of Shree Panchami, considered one of the most auspicious occasions for weddings in the Hindu religion. Chakraman reluctantly performed some of the wedding rites. Her groom, Prakash Balami, was 15. Almost immediately, Sumeena became pregnant.

Left: Prakash Balami, 15, is groomed by friends and family for his wedding ceremony in Kagati village, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, on Jan. 23, 2007. Right: Prakash and his bride, Sumeena, 13. Stephanie Sinclair/VII Network hide caption

Left: Prakash Balami, 15, is groomed by friends and family for his wedding ceremony in Kagati village, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, on Jan. 23, 2007. Right: Prakash and his bride, Sumeena, 13.

Prakash, 15, and Sumeena, 13, married in 2007. An estimated 115 million boys and men around the world were married as children, UNICEF stated in its first in-depth analysis of child grooms. Of these, 1 in 5, or 23 million, were married before the age of 15. Stephanie Sinclair/VII Network hide caption

Prakash, 15, and Sumeena, 13, married in 2007. An estimated 115 million boys and men around the world were married as children, UNICEF stated in its first in-depth analysis of child grooms. Of these, 1 in 5, or 23 million, were married before the age of 15.

"We suffered a lot," recalls Prakash, now 30. "She became dizzy, she was sick all the time.

"I was very young then – I was a child," he says. "I didn't know much about weddings or marriage."

Sumeena's underdeveloped pelvic bones made for a difficult and painful delivery that quickly became life-threatening to both her and the unborn child. She was rushed to the hospital for a cesarean section.

While Sumeena and their son, Mukesh, survived, the pregnancy abruptly ended her education. The young family's financial demands drove Prakash out of school shortly thereafter.

"After my son was born, my childhood was gone," he says. "I was very much interested in social work before I got married. I thought if someone had a problem, I could go help. I really like helping people, but that's all gone."

When his son reached school age, Prakash took a job in construction for two years in the sweltering, year-round heat of Qatar, planning to earn money to send home to his young family. But he says his earnings were withheld to ostensibly pay off the recruiter fees. He returned home empty-handed, unable to afford even a school uniform for his son.

"I thought I would earn a lot for my family, for my children," says Prakash. "That was my dream. But nothing turned out the way I thought it would."

Prakash Balami, 29, was forced into an arranged marriage at 15. He poses with his wife, Sumeena, 27, and their children, Paratichya and Mukesh, next to their home, which was destroyed in the 2015 earthquake in Kagati village. "After my son was born, my childhood was gone," he says. "I was very much interested in social work before I got married. I really like helping people, but that's all gone." Stephanie Sinclair for NPR hide caption

Prakash Balami, 29, was forced into an arranged marriage at 15. He poses with his wife, Sumeena, 27, and their children, Paratichya and Mukesh, next to their home, which was destroyed in the 2015 earthquake in Kagati village. "After my son was born, my childhood was gone," he says. "I was very much interested in social work before I got married. I really like helping people, but that's all gone."

Satellite TV and the internet add a complication

In an ironic twist, the modern age, with increased access to satellite television and internet on smart phones , has reinforced the practice of child marriage. In previously sheltered Nepali villages, South Indian movies blast melodramatic love stories nightly into homes, with young eyes watching. The result is a surge in teen romance – and in parental fear that their daughters will defame the family by having premarital relations.

"We fell in love in grade nine," explains Chakraman's son, Nirazan Balami. "But we were kind of forced to marry because her father came to know we were in a relationship. I was 17."

Smitten, the teenage Nirazan says the girl's father overheard him saying "love-related things a boyfriend says to a girlfriend." The father insisted the couple immediately become husband and wife.

In shock and overcome with stress, Nirazan tried to calm his nerves with alcohol. Then, he called his mother saying he wanted to get married.

"My mother told my father because I couldn't bear to tell him. When he came to know, he shouted at me, 'No, no, no! Not now! This is not the right decision!' "

Chakraman arrived in Kathmandu the following morning to take Sanjeeta back to her father's house. A few days later, Nirazan returned to the village to find his parents still distraught and angry. Sanjeeta had been calling him daily in response to her father's relentless pressure to marry Nirazan.

Nirazan Balami, 21, hold his 17-month-old son, Nir. He married at 17 under intense pressure from his wife's family. Stephanie Sinclair for NPR hide caption

Nirazan Balami, 21, hold his 17-month-old son, Nir. He married at 17 under intense pressure from his wife's family.

In an effort to placate Sanjeeta's father, Nirazan finally convinced his parents to let them get engaged.

His mother acquiesced and immediately began making arrangements for the wedding.

"That's how I got married," says Nirazan.

For a while, Nirazan was able to return to veterinary school. But the newlywed couple soon married. In 2017, they had a child, and, like his father, Nirizan's education came to a halt.

"I felt pressure to earn money because I had a family. I felt very depressed. I thought, I don't know, why should I live?"

Before long, Nirazan got a job as an excavator driver. He's held the job for several years – and still can't help but wonder what his life could have been like had he been allowed to continue his studies.

Economics could be a key to convincing parents not to marry off their children. High-ranked officials in the village, including former members of the youth club, say the pace of change will remain incremental at best until many parents see economic benefits of letting their children continue their education – both girls and boys, the pace of societal change will remain incremental at best.

Will things ever change?

Clearly, child marriage for boys will not end unless it ends for girls, says Anju Malhotra, a fellow at the United Nations University-International Institute for Global Health and a global leader in gender issues.

For this to happen, families have to realize that there's an economic benefit to keeping girls in school – a tough idea to embrace during a pandemic and when climate change is having an impact on harvests, she says.

And while there are clear career paths for sons, she says that families don't have enough awareness that the same should be true for daughters.

Sumeena, 13, is carried in a basket during her wedding to Prakash, 15, in 2007. Stephanie Sinclair/Stephanie Sinclair/VII hide caption

Sumeena, 13, is carried in a basket during her wedding to Prakash, 15, in 2007.

She says there also must be programs in villages to sensitize families on the importance of decoupling their reputation from their daughter's intimate decisions – and that those decisions should not be cause for immediate marriage.

Without these changes for girls, the boys will also be unable to break free from pressure for child marriage, says Malhotra.

Had they just postponed the wedding, Nirazan says he feels that his life and his wife's life would be much different today. He wishes he could have communicated that to his wife's parents.

"Now," he says, "we've both sacrificed our dreams."

In a career that's spanned over two decades, Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Stephanie Sinclair has focused on gender and human rights issues, with special attention to the topic of child marriage. In 2014, she founded the charitable organization Too Young to Wed , whose mission is to empower girls and end child marriage globally.

- child grooms

- child marriage

- child brides

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 December 2020

Early marriage and women’s empowerment: the case of child-brides in Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia

- Mikyas Abera 1 ,

- Ansha Nega 2 ,

- Yifokire Tefera 2 &

- Abebaw Addis Gelagay 3

BMC International Health and Human Rights volume 20 , Article number: 30 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

39k Accesses

19 Citations

59 Altmetric

Metrics details

Women, especially those who marry as children, experience various forms and degrees of exclusion and discrimination. Early marriage is a harmful traditional practice that continues to affect millions around the world. Though it has declined over the years, it is still pervasive in developing countries. In Ethiopia, Amhara National Regional State (or alternatively Amhara region) hosts the largest share of child-brides in the country. This study aimed at assessing the effects of early marriage on its survivors’ life conditions – specifically, empowerment and household decision-making – in western Amhara.

This study employed community-based cross-sectional study design. It adopted mixed method approach – survey, in-depth interview and focus group discussion (FGD) – to collect, analyse and interpret data on early marriage and its effects on household decision-making processes. The survey covered 1278 randomly selected respondents, and 14FGDs and 6 in-depth interviews were conducted. Statistical procedures – frequency distribution, Chi-square, logistic regression – were used to test, compare and establish associations between survey results on women empowerment for two groups of married women based on age at first marriage i.e., below 18 and at/after 18. Narratives and analytical descriptions were integrated to substantiate and/or explain observed quantitative results, or generate contextual themes.

This study reported that women married at/after 18 were more involved in household decision-making processes than child-brides. Child-brides were more likely to experience various forms of spousal abuse and violence in married life. The study results illustrated how individual-level changes, mainly driven by age at first marriage, interplay with structural factors to define the changing status and roles of married women in the household and community.

Age at first marriage significantly affected empowerment at household level, and women benefited significantly from delaying marriage. Increase in age did not automatically and unilaterally empowered women in marriage, however, since age entails a cultural definition of one’s position in society and its institutions. We recommend further research to focus on the nexus between the household and the social-structural forms that manifest at individual and community levels, and draw insights to promote women’s wellbeing and emancipation.

Peer Review reports

Early marriage is any marriage entered into before one reaches the legal age of 18 [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Though both boys and girls could marry early, the norm in many countries around the world is that more girls than boys marry young and someone older [ 3 ]. In Mauritania and Nigeria, for instance, “more than half of married girls aged 15-19 have husbands who are 10 or more years older than they are” [ 3 ].

Resilient and interlinked socioeconomic and normative factors (e.g. poverty, illiteracy, traditionalism, patriarchy, etc.) undermine women’s status, capabilities and choices, and ensure early marriage continues unabated in many developing countries [ 4 ]. As a harmful traditional practice, though it is more common in developing than developed countries, there are substantial variations between and within regions of the world and countries [ 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. For instance, half of the world’s child-brides live in South Asia; and, while early marriage is still most common in Sub-Saharan Africa, between them, these two regions host the 10 countries with the highest rates of early marriage [ 3 , 5 , 8 ].

By early 2000s, 59% of Ethiopian girls were marrying before 18 [ 9 ]. Footnote 1 As in the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa, early marriage in Ethiopia is gendered with only 9% of men aged 25–49 been married by 18 [ 10 , 11 ]. Its effects are diverse and wide-ranging [ 3 , 4 ]. In its onset, early marriage effectively ends childhood by limiting its victims’ opportunities for schooling, skills acquisition, personal development and even mobility. It also increases the risks of early onset of sex, adolescent pregnancy and childbearing, etc. [ 12 , 13 ] whose negative outcomes are amplified by girls’ undeveloped physique and lack of or inadequate knowledge on healthy sexual and reproductive behaviours. Cumulatively, these effects of early marriage undermine girls’ and young women’s health, psychosocial wellbeing and overall quality of life [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Early marriage is not only a serious public health issue. It also exacerbates domestic violence [ 17 ] and undermines women’s status and decision-making powers [ 18 , 19 ]. It increases women’s risk of intimate partner sexual violence, for it is built on spousal age gap, power imbalance, social isolation and lack of female autonomy. Globally, some 30% of girls (aged 15–19) experience violence by partners [ 20 ]. Bangladeshi women married during their adolescence, for instance, are subject to increased domestic violence and loss of autonomy, which, nonetheless, improved with their educational attainment [ 21 ]. Child-brides, specifically, are twice as likely as adult-brides to experience domestic violence [ 22 ]. This is partly because child-brides are more likely to be uneducated, poor and adherents to traditional gender norms [ 3 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ].

Child-brides are mostly isolated with restricted mobility and limited opportunities for independent living. Those who had been going to school would be coerced to discontinue when they marry, and those who have not been to school, the hope to do so dies on their wedding day. In Tach-Gaynt Woreda of Amhara region, for instance, 69% of young women marry early. Between 2009 and 2014, females represented 61% primary school dropouts in the Woreda; and, 34% of female school dropouts mentioned early marriage as the main reason. If child-brides want to start/continue schooling, a rare approval must come from husbands and/or families. In rural communities of Ethiopia, including Amhara region, the ‘good wife’ is primarily pictured in terms of what she accomplishes at home and for the husband, children and the elderly in the family and kinship.

Against the backdrop of mounting calls for legal and policy changes, Ethiopia introduced provisions [ 10 ] to redress gender inequalities and discrimination in its most recent Constitution (1995; Article 35:3) [ 27 ]; it has also revised its Family (2000) and Penal (2005) Codes to, among other things, raise the age of legal consent for women to 18 (from 15). Ethiopia’s latest Education and Training Policy [ 28 ] introduced provisions to reorient societal attitude towards and valuation of women in education, training and development. More profoundly, and partly due to international pressure, in 2013, Ethiopia spelled out its commitment to eradicate early marriage by 2025 in the National Strategy and Action Plan on Harmful Traditional Practices against Women [ 29 ]. These and other relevant documents informed governmental and nongovernmental interventions to remove barriers, including early marriage, to young women’s personal advancement and empowerment, and taking effect at individual, institutional, national and cultural levels.

Accordingly, age at first marriage has been increasing over the years in Ethiopia [ 9 ]; nonetheless, its reported scale and rate are suspect for two main reasons. First, the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) defines age at first marriage as the age at which partners begin living together under one roof [ 29 ], despite the fact that many early marriages in Ethiopia allow spouses to start living together only a few years later as in the cases of promissory or child marriages [ 4 ]. Second, systematic underreporting or omission is a high possibility, which would lower the magnitude of early marriage among girls than boys as the latter commonly delay marriage. Criminal prosecution under the Revised Family Code (Article 7) could also induce underreporting or deliberate omission of early marriages.

Though there needs to be caution in interpreting statistics on early marriage in Ethiopia, it has been amply documented that Ethiopian women’s low social status explains their limited rights and odds to assume duties, roles and authority on equal terms as their male counterparts [ 9 , 30 ]. Early marriage, one manifestation of this violence, is intimately linked with gender, poverty and illiteracy in rural Ethiopia [ 30 ]. Rural women tend to marry younger than those in urban areas, while patriarchy and the feminization of poverty, illiteracy and low educational attainment play crucial role in perpetuating the imbalance [ 9 , 30 ].

There are studies that document strong association between early marriage and poverty. UNICEF reports that one in three girls in low- to middle-income countries will marry before 18 [ 3 , 31 ]. Nonetheless, though many see a strong link between poverty and early marriage, the correlation is never monotonic. Family riches are not guarantee to avoid early marriage. With growing population and land shortages, girls from better-off families who stand to inherit valuable resources have become easy targets for sustained solicitations by those who desire to ‘marry-into’ wealth. Conversely, poor families generally resort to early marriage as a strategy to reduce economic vulnerability. In both scenarios, however, early marriage is seen as a mechanism to strengthen ties between families, evade the risk of daughters engage in premarital sex (and lose their virginity and/or become pregnant) or pass the culturally defined ‘desirable age’ for marriage (and become unmarriable).

The sociocultural consequences of becoming pregnant outside wedlock are harsh as they go against deep-rooted cultural norms that tie girls’ chastity and sexual purity before marriage to their family honor as well as their marriageability. Most parents fear delaying marriage makes sexual encounters imminent – consented or otherwise – that disgraces the family and tarnishes girls’ reputation and, subsequently, marriage prospects.

Within Ethiopia, girls in some regional states are more likely to marry early; and, Amhara region has the highest prevalence of early marriage with 50% of girls marrying at 15, and 80% marrying at 18 [ 32 , 33 ]. In 2014, 74% of women [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ] in the region married before 18, significantly higher than the national average of 41% [ 2 ]. To put this in perspective, “a girl born in [Amhara region] is three times as likely as the girl born in Addis Ababa to marry early” [ 3 ].

Reports on improving inter-generational age at first marriage at national level puts the persistently high prevalence of early marriage in Amhara region in a curious light [ 34 ]. In the region, early marriage is deeply entrenched in religious and cultural norms where sex before marriage is a blow to a girl’s marriageability, for her worth lies in her sexual purity, her future role as a devout wife and mother, and her commitment to family honor [ 35 ]. Hence, despite proactive laws, institutional structures and project interventions, early marriage grew adept and continues to affect the lives of many under different guises.

Due to its myriad nature [ 36 , 37 ], on the other hand, eradicating early marriage requires simultaneously addressing its various dimensions and promoting girls’ empowerment through education, institutional support structures and community development programs. Informed by a mixed-methods approach, thus, this study aimed at informing such types of interventions at national and regional levels by identifying its association with women’s empowerment at three Zones (North Gondar, South Gondar and West Gojjam) of Amhara region – the regional State with “one the world’s highest rates of child marriage” (and the highest in Ethiopia) where “most unions take place without girls consent” [ 38 ]. The effects of early marriage go beyond the child-brides and their children, for they severely undermine national and global progress on a variety of Sustainable Development Goals, i.e., Agenda-2030. In light of this, this interdisciplinary study, falls within the current research priority agenda of promoting evidence-based policymaking and interventions [ 39 ] to mitigate early marriage as a resilient sociocultural problem – both from a human rights standpoint and meeting the Sustainable Development Goals targets.

Theoretically, systems theory, with its roots in Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s general systems theory, informs this study [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. General systems theory argues that all entities – physical, biological, chemical, social, etc. – are complex, structured and dynamic systems, and they constitute sub-systems or units that interact with one another as well as the external environment. His theory advanced remarkably over the years with applications in biology [ 43 , 44 , 45 ], economics [ 46 , 47 , 48 ], psychiatry [ 49 , 50 ] and sociology [ 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ], among others.

In the field of family studies, systems theory has been used to study family or marriage as an interactional system, whereby patterns in members’ behaviors reflect interdependencies and communications amongst each other and with their normative environment, primarily – rather than their idiosyncrasies. As such, it brings at least two advantages to the current study: firstly, it allows us to understand the norms that structure families, marital relations, individual choices and decisions; secondly, it helps us unravel the tensions between agency and structure i.e., how changes at individual, family and cultural levels feed on each other to make family or marriage a dynamic interactional system capable of recalibrating its functions, communications, etc. vis-à-vis subsystems other systems in its sociocultural milieu [ 55 , 56 ].

Using systems theory, hence, this study explores the effects of early marriage on child-brides interactional outcomes of a series of factors, including individuals’ personal convictions, the function of marriage (for instance, marriage in traditional societies is primarily a cultural arrangement that decent groups use to cement desirable alliances), normative definitions of sex, sexuality, etc. In other words, this study will treat early marriage as part of a broader, normative system where decisions or actions cannot be random but aim to create, maintain or re-create a state of equilibrium. Consensus, conflict, abuse or violence in a family, as Stratus puts it, can viewed as, primarily, products of the system than individual pathology [ 55 ]. Factors that perpetuate any of these scenarios in a family are embedded within the very fabric of the culture and norm that structure the family institution and relations among members i.e., individuals cannot randomly opt out of the norms of the system patterns without suffering consequences for their indiscretions or violations.

Description of the study area

The Amhara region is one of the 10 regional states and 2 city administrations that make-up the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Footnote 2 The region has an estimated population of 21.13million, with 90.85% residing in rural areas. Agriculture is the mainstay of residents in rural areas, with tourism, services and commerce creating the majority of jobs for urbanites. In 2013, Net Enrolment Rate at primary level was 93%, with gender parity at 0.95 [ 57 ]. The national adult literacy rate was 41.5% in 2012 [ 58 ].

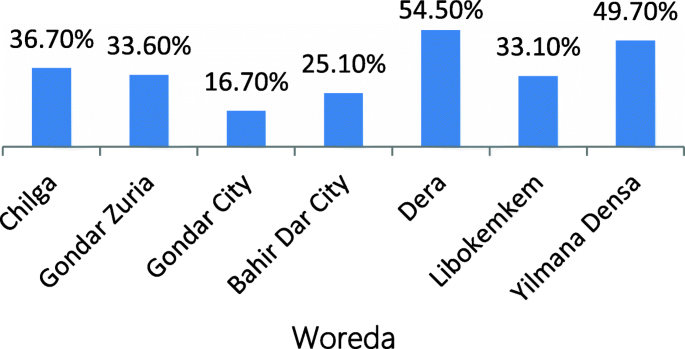

This study covered 7 administrative districts – five Woredas and two cities – located in three Zones – North Gondar, Footnote 3 South Gondar, West Gojjam – of northwestern Amhara region i.e., Chilga (Code.01), Gondar Zuria (Code.02), Libo-Kemkim (Code.05), Derra (Code.06) and Yèlma-èna-Dénsa (Code.07) Woredas , and cities of Gondar (Code.03) and Bahir Dar (Code.04). These districts are of varying sizes and they are subdivided into Kebeles – smallest administrative unit in the Ethiopian federal structure. The fieldwork was conducted between January and April 2017.

Study population

This study covered all women who had had their first marriage within 10-years prior to the fieldwork, irrespective of their current marital status, in western Amhara region. The 10-years timeline provided a reasonably representative group of married women who would furnish sufficient data to assess changes in the incidence, prevalence and multifaceted effects of early marriage on their life conditions.

Study design

This study employed a mixed method approach involving quantitative and qualitative methods. A cross-sectional study design with descriptive and analytical components enabled a comparative assessment of the effects of early marriage on women’s empowerment in the domestic sphere. Theoretically, system theory informs the discussion, analysis and interpretation of data i.e., by taking into account both individual (e.g., age) and ecological (e.g., cultural value, public policy) factors as they interact and affect actors’ behaviors (in this case, interpersonal interactions and decision-making) at household level.

Methods of the study

Survey, focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews generated relevant data on married women. A representative sample of 1278 married women were surveyed to gathered data on the prevalence and outcomes of early marriage in western Amhara region. Qualitative methods – FGD and in-depth interview – were used to assess married women’s experiences, community perceptions and values on (early) marriage, appropriate age of marriage, and impact of early marriage and community change-actors, among others. Critical desk-review of relevant documents generated perspectives and insights to triangulate the results of primary data.

Sample size

Survey sample size was calculated using a single population formula, by assuming the proportion of early marriage in Ethiopia among married women whose age less than 24-years at 41% [ 2 ], with 95% confidence level and 4% margin of error: 581 . But after considering design effect for two-stage cluster sampling (*2) and non-response rate (*10%), the final survey sample size was determined at 1278 (=581*2 + (581*.10)).

To collect qualitative data, 2 types of FGDs were conducted in each of the 7 districts with, on average, 8 discussants: FGD 1 , with child-brides – a mixed length of age at first marriage i.e., 1–5 years and 6–10 years, and their residential place i.e., rural or urban; and, FGD 2 , with representatives of community leaders, elders, law enforcement officers, parents, school directors and governmental and non-governmental organizations working on children and girls. In total, 14 FGDs were conducted.

Sampling procedure

Probability and purposive sampling techniques were used, respectively, for survey, and FGD and in-depth interview. Firstly, 7 districts – 5 Woredas (Chilga, Gondar Zuria, Derra, Libo-Kemkim and Yèlma-èna-Dénsa) and 2 cities (Gondar and Bahir Dar) – of Amhara region were identified, for they host community intervention projects intended to curb early marriage. Secondly, 4 Kebeles from each district were selected and the sampling procedure accounted for differences among districts in their residential pattern (urban vs. rural) and availability of community intervention projects (beneficiaries vs. non-beneficiaries). Specifically, the sampling procedure followed a 3:1 urban: rural ratio for the two cities, and the reverse for the 5 Woredas . Finally, the 1278 survey sample was distributed to each Kebele based on its population size and the number of women in reproductive age (ages, 15-49). Using Kebele residents’ rosters as sampling frame, a random – and proportionate – sample of households were selected for the survey from each Kebele .

Data collection tools and procedure

All data collection tools (enumerator-administered questionnaire, and FGD and in-depth interview guides) were initially designed in English. They were translated into Amharic, and then back to English – forward-and-backward translation – to ensure their validity and consistency. The questionnaire was pilot-tested at Teda Kebele of North Gondar Zone, a Kebele excluded from the survey, to check for its validity, reliability and consistency. The pilot improved the questionnaire’s completeness, appropriateness, conciseness and relevance as well as the feasibility of the fieldwork.

Twenty-eight females were employed as survey enumerators from World Vision–Ethiopia’s roster of data collectors that documents trained, experienced, locally-resourceful youth for possible recruitment as enumerators, interviewers, guides, etc. in research projects. These enumerators and local guides underwent 2-days intensive training on research methods, data collection tools, interviewing skills, etc. including running mock-interview sessions. After the training, they administrated survey questionnaires by travelling from household to household. They, before asking survey questions, were required to explain the objective of the study, requested for informed consent to participate in the study and checked respondents’ profile for eligibility i.e., women married within 10 years during the fieldwork.

Two types of FGDs, 14 in total, were conducted: FGD 1 involved child-brides who were identified and invited by enumerators during the survey; and, discussants for FGD 2 were identified based on their knowledge of the problem of early marriage in the study area and approached via administrative channels. Finally, 6 in-depth interviews were conducted with child-brides, chosen purposively as their experiences vividly illustrate the effects of early marriage on women’s empowerment.

After inquiring about preferences and confirming with participants, FGDs and in-depth interviews were conducted in facilities and spaces convenient to all such as offices of World Vision–Ethiopia, Gender and Legal Affairs, and Youth Centers. These facilities and spaces were assessed beforehand for their cleanliness, calm, safety and accessibility as well as falling outside non-participants’ earshot and possible intrusions. On average, FGDs and in-depth interviews took, respectively, 60 and 40 min to complete. Authors conducted FGDs and interviewed child-brides.

Data management and analysis

For the survey, all filled and returned questionnaires were checked for completeness and consistency of responses. Once survey data collection was finalized, 3 experienced data encoders entered questionnaire data into Epi-Info and later transferred to SPSS [ 20 ] as data-sets for cleaning, organization and analysis. Descriptive and inferential statistics were employed to determine, among others: the prevalence of early marriage; the incidences and magnitude of bad outcomes of early marriage on women’s decision-making; and, community’s perception on early marriage and appropriate age of marriage. Binary logistic regression models were used determine the likely occurrence of different forms of disempowerment in two groups of women i.e., those married before 18 and those married at/after 18. A p -value of 0.05 was used as a cut-off point to determine statistical significance.

Regarding FGDs and in-depth interviews, all sessions, with the consent of participants, were digitally recorded. Audio-files were later transcribed, post-coded and categorized under core thematic areas. Thematic content analysis provided insights into the nature, community perception and drivers of early marriage and changes. Analytical descriptions and quotes from FGDs and in-depth interviews were used to triangulate, contextualize or explain survey results. Narrated texts, graphs and tables were used to present results according to the nature of the information derived.

In quoting directly from FGDs and in-depth interviews, codes were used to refer to the method, source and location (districts). Accordingly, FGD-R01, for instance, refers to an FGD conducted with representatives of relevant stakeholders (i.e., R) in Chilga Woreda of North Gondar Zone (i.e., 01). Similarly, Interview-S07 refers to an interview conducted with child-brides (i.e., S) in Yèlma-èna-Dénsa Woreda of West Gojjam Zone (i.e., 07).

Ethical considerations

Data for this article are taken from a larger study the authors conducted on behalf of E 4 Y Project , a project run by World Vision-Ethiopia and cleared for appropriate ethical standards at national and regional levels. On behalf of the authors, World Vision–Ethiopia supplied official letters to the respective regional and district administration offices and provide support and facilitation as required.

During the fieldwork, study participants and/or parents/legal guardians (when participants were under the age of 18) were informed about the study objectives and the scope of their involvement beforehand. Verbal consent was obtained from participants or parents/guardians prior to commencing survey, interviews or FGDs. Privacy and confidentiality were granted and maintained during the survey, discussions or interviews. Confidentiality of digital recordings and transcribed data were strictly protected and this was explained to all participants. During FGDs and in-depth interviews, special attention was given to when asking sensitive questions based on local contexts. Participants’ concerns and questions were addressed before they provided individual, informed consents. There was no financial incentive offered to study participants. Nonetheless, participants who had to travel from distant Kebeles for study’s purpose were provided with transport allowance.

The preliminary findings of the study were presented and validated in a national validation workshop held at Bahir Dar city (Ethiopia) and in attendance were representatives of the community (including study participants) and relevant governmental and non-governmental organizations working on early marriage. Workshop participants reflected on the process and results of the study. The authors addressed the comments and questions raised during the workshop, and they revised the study report submitted to World Vision-Ethiopia.

The results and findings of the study are organized and presented in two sub-sections: (a) the prevalence of early marriage; and (b) early marriage and household decision-making in Amhara region. Let us start with the prevalence of early marriage and its variation among districts of the region.

The prevalence of early marriage in Amhara region

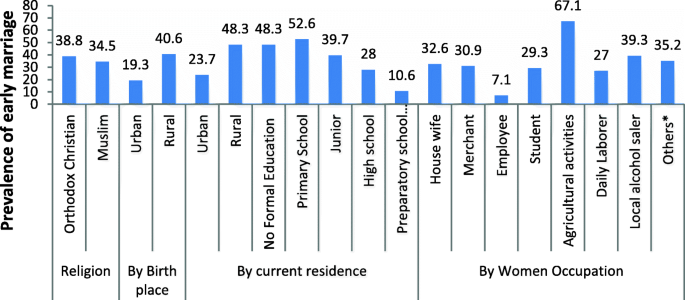

The survey covered 1278 married-women respondents, while 112 [ 6 ] participants took part in 14 FGDs (interviews). Of the 1278 respondents, 444 (34.7%) were married before the age of 18 Fig. 1 . Nonetheless, as Fig. 2 reports, there was variation in the prevalence rate of early marriage among districts in the study area: Derra (54.5%) and Yèlma-èna-Dénsa (49.7%) Woredas registered the highest, and the cities of Gondar (16.7%) and Bahir Dar (25.1%) the lowest rates of early marriage. With the regional prevalence rate of 32%, the results indicated that urbanization is inversely related to the prevalence rate of early marriage.

Prevalence of early marriage in Western Amhara, Ethiopia (Survey, 2017)

Comparatively, early marriage was high among Orthodox Christians (38.8%) and rural residents (40.6%). Regarding schooling, the proportion of child-brides increased from ‘no formal schooling’ (48.3%) to ‘primary level’ (52.6%), before it declined at junior (39.7%) and senior (28%) high-school levels. These results underlined rural residents and primary grades as potent entry points for any effective intervention, for 53% of primary graders and 41% of rural residents ended up marrying before 18.

Respondents’ age at first marriage ranged from 5 to 35 (M = 18.75; SD = 3.44); and, the lowest ages to start living with spouses and make sexual debut among respondents were, respectively, 9 (M = 18.93; SD = 3.25) and 10 (M = 18.80; SD = 3.11).

Among respondents primarily engaged in farming, on the other hand, 67.1% experienced early marriage, which is not unexpected since the prevalence of early marriage is high in rural areas where agriculture is the main employer of labor. Similarly, 39.3% those who produce and sell local alcoholic beverages were married before 18 (Fig. 2 ). These and the results presented above indicate that early marriage has pertinent impacts on and associations with young women’s education, economic development and wellbeing.

Prevalence and profile of early marriage in Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia (Survey, 2017)

Early marriage and household decision-making in Amhara region

In this section, the effects of early marriage on young women’s empowerment at household decision-making processes are presented under five sections: early marriage, marital interactions and dysfunctions; early marriage and spouse abuse; early marriage and household management; early marriage, social interactions and procreation; and early marriage and healthcare.

Early marriage, marital relations and dysfunction