- List of Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Opt-out preferences

Types of Speech in Communication

Communication is a fundamental aspect of human interaction, and speech is one of its most powerful tools. Speech allows individuals to convey ideas, emotions, intentions, and information effectively. Different types of speech are used depending on the context, audience, and purpose of communication.

Understanding these types helps in selecting the appropriate mode of expression and achieving the desired impact.

1. Informative Speech

Informative speech educates or informs the audience about a particular topic. The primary goal is to provide knowledge, explain concepts, or clarify issues. This type of speech is often used in educational settings, professional presentations, or public lectures.

Example: A professor giving a lecture on the impacts of climate change is delivering an informative speech. The professor provides data, explains scientific concepts, and discusses potential solutions to the problem. The focus is on sharing factual information to enhance the audience’s understanding.

2. Persuasive Speech

Persuasive speech aims to convince the audience to adopt a certain viewpoint or take a specific action. The speaker uses logical arguments, emotional appeals, and credible evidence to influence the audience’s beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors. Persuasive speeches are common in political campaigns, advertising, and debates.

Example: A politician giving a campaign speech will likely use persuasion to garner support. They might highlight their achievements, present their future plans and appeal to the emotions of the audience by addressing pressing societal issues. The objective is to persuade the audience to vote for them.

3. Demonstrative Speech

Demonstrative speech involves showing the audience how to do something. It combines explanation with practical demonstration, making it easier for the audience to understand and replicate the process. This type of speech is useful in workshops, training sessions, and instructional videos.

Example: A chef giving a cooking class is engaging in demonstrative speech. They not only explain the recipe but also demonstrate each step, such as chopping vegetables, mixing ingredients, and cooking the dish. The audience learns by watching and can follow along.

4. Entertaining Speech

Entertaining speech is intended to amuse the audience and provide enjoyment. While it may contain informative or persuasive elements, its primary purpose is to entertain. This type of speech is often light-hearted, humorous, and engaging, making it suitable for social events, ceremonies, or entertainment shows.

Example: A stand-up comedian performing a routine uses an entertaining speech to make the audience laugh. The comedian may share funny anecdotes, joke about everyday situations, or use witty observations to entertain the crowd. The focus is on creating an enjoyable experience.

5. Special Occasion Speech

Special occasion speech is delivered during specific events or ceremonies, such as weddings, graduations, funerals, or award ceremonies. The content is often personalized and tailored to the occasion, focusing on the significance of the event and the emotions associated with it.

Example: During a wedding, the best man might give a special occasion speech to honor the couple. The speech might include heartfelt memories, humorous stories, and well-wishes for the future. The purpose is to celebrate the occasion and express support for the couple.

6. Impromptu Speech

An impromptu speech is delivered without preparation, often in response to an unexpected situation or question. It requires quick thinking and the ability to articulate thoughts clearly on the spot. This type of speech is common in casual conversations, interviews, or meetings.

Example: In a team meeting, an employee might be asked to give an impromptu speech about the progress of a project. Without prior notice, the employee summarizes the project’s status, highlights key achievements, and addresses any challenges. The speech is spontaneous and unscripted.

7. Extemporaneous Speech

Extemporaneous speech is prepared in advance but delivered without a script. The speaker has a general outline or notes but speaks more freely, allowing for natural delivery and adaptability. This type of speech is common in business presentations, academic conferences, and public speaking engagements.

Example: A business executive presenting a quarterly report to stakeholders might use extemporaneous speech. They have prepared key points and data but speak conversationally, adjusting their delivery based on the audience’s reactions and questions. This approach allows for a more engaging and dynamic presentation.

8. Manuscript Speech

Manuscript speech is read word-for-word from a prepared text. This type of speech is often used when precise wording is essential, such as in official statements, legal proceedings, or news broadcasts. The speaker focuses on delivering the content accurately without deviation.

Example: A news anchor reading the evening news is using manuscript speech. The anchor reads from a teleprompter, ensuring that the information is conveyed accurately and clearly. The emphasis is on precision and professionalism.

9. Memorized Speech

Memorized speech involves delivering a speech from memory, without notes or a script. This approach is often used in performances, speeches that require exact wording, or competitive speaking events. Memorization allows for a polished and confident delivery but requires extensive practice.

Example: An actor reciting a monologue in a play is giving a memorized speech. The actor has committed the lines to memory and delivers them with emotion and expression, engaging the audience fully. The speech is fluid and rehearsed, showcasing the actor’s skill.

10. Motivational Speech

Motivational speech is designed to inspire and energize the audience, often encouraging them to pursue their goals or overcome challenges. The speaker uses personal stories, powerful messages, and emotional appeals to uplift the audience and provoke action.

Motivational speeches are common in self-help seminars, leadership conferences, and personal development events.

Example: A life coach speaking to a group of entrepreneurs might give a motivational speech about resilience and perseverance. The coach shares personal experiences of overcoming obstacles and encourages the audience to stay focused on their goals, despite setbacks.

11. Pitch Speech

A pitch speech is a brief, persuasive speech used to present an idea, product, or proposal to an audience, usually with the aim of securing funding, approval, or support. The speaker must be concise, clear, and convincing, often focusing on the benefits and potential impact of the proposal.

Example: An entrepreneur pitching his startup idea to potential investors is giving a pitch speech. The entrepreneur outlines the problem their product solves, the market opportunity, and how the investors will benefit, all within a few minutes.

A eulogy is a speech delivered at a funeral or memorial service, honoring the life and legacy of a deceased person. The speaker reflects on the person’s character, achievements, and the impact they had on others, often blending personal anecdotes with expressions of gratitude and remembrance.

Example: A family member delivering a eulogy at a funeral might share touching stories about the deceased, highlighting their kindness, generosity, and love for their family. The eulogy serves as a tribute, celebrating the life of the person who has passed away.

Tips for Giving a Great Speech

1. Know Your Audience : Understanding your audience’s interests, values, and expectations helps tailor your message effectively.

2. Structure Your Speech: Organize your content with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion. A well-structured speech is easier to follow and more impactful.

3. Practice: Rehearse your speech multiple times to become familiar with the content and improve your delivery. Rehearse your speech alone or in front of your friends (maybe in low numbers) to become familiar with the vocabulary and pronunciation of the precise phrases. so you can control the speed and improve your speech delivery.

4. Use Visual Aids: Visual aids can enhance understanding and retention. Ensure they are relevant and not overly distracting.

5. Engage with the Audience: Make eye contact, use gestures, and involve the audience through questions or interactive elements to keep them engaged.

How to Make Your Speech More Memorable

1. Start with a Strong Opening: Capture attention with a powerful quote, anecdote, or question that relates to your main message.

2. Use Stories: People remember stories better than facts alone. Incorporate personal or relatable stories to illustrate your points.

3. Be Passionate: Express enthusiasm and passion for your topic. A passionate delivery can leave a lasting impression.

4. Repeat Key Points: Repetition helps reinforce important ideas. Summarize key points at the end of your speech to ensure they stick.

5. End with a Call to Action: Encourage your audience to take a specific action or reflect on your message. A clear and compelling conclusion makes your speech memorable.

Related Posts:

- Non-Verbal Communication

- Various Types Of Communication Styles - Examples

- Types Of Thinking-Tips And Tricks To Improve Thinking Skill

- Conflict Management - Skills, Styles And Models

- Types Of Motivation And Its Components - Examples

- Most Important Social Skills - Explained With Examples

Leave a Comment

Next post: Burke’s Dramatism Theory

Previous post: Bloom’s Taxonomy | Domains of Learning with Examples

- Advertising, Public relations, Marketing and Consumer Behavior

- Business Communication

- Communication / General

- Communication Barriers

- Communication in Practice

- Communication Models

Communication Theory

- Cultural Communication

- Development Communication

- Group Communication

- Intercultural Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Mass Communication

- Organisational Communication

- Political Communication

- Psychology, Behavioral And Social Science

- Technical Communication

- Visual Communication

- Games, topic printables & more

- The 4 main speech types

- Example speeches

- Commemorative

- Declamation

- Demonstration

- Informative

- Introduction

- Student Council

- Speech topics

- Poems to read aloud

- How to write a speech

- Using props/visual aids

- Acute anxiety help

- Breathing exercises

- Letting go - free e-course

- Using self-hypnosis

- Delivery overview

- 4 modes of delivery

- How to make cue cards

- How to read a speech

- 9 vocal aspects

- Vocal variety

- Diction/articulation

- Pronunciation

- Speaking rate

- How to use pauses

- Eye contact

- Body language

- Voice image

- Voice health

- Public speaking activities and games

- Blogging Aloud

- About me/contact

- Types of speeches

The 4 types of speeches in public speaking

Informative, demonstrative, persuasive and special occasion.

By: Susan Dugdale

There are four main types of speeches or types of public speaking.

- Demonstrative

- Special occasion or Entertaining

To harness their power a speaker needs to be proficient in all of them: to understand which speech type to use when, and how to use it for maximum effectiveness.

What's on this page:

An overview of each speech type, how it's used, writing guidelines and speech examples:

- informative

- demonstrative

- special occasion/entertaining

- how, and why, speech types overlap

Return to Top

Informative speeches

An informative speech does as its name suggests: informs. It provides information about a topic. The topic could be a place, a person, an animal, a plant, an object, an event, or a process.

The informative speech is primarily explanatory and educational.

Its purpose is not to persuade or influence opinion one way or the other. It is to provide sufficient relevant material, (with references to verifiable facts, accounts, studies and/or statistics), for the audience to have learned something.

What they think, feel, or do about the information after they've learned it, is up to them.

This type of speech is frequently used for giving reports, lectures and, sometimes for training purposes.

Examples of informative speech topics:

- the number, price and type of dwellings that have sold in a particular suburb over the last 3 months

- the history of the tooth brush

- how trees improves air quality in urban areas

- a brief biography of Bob Dylan

- the main characteristics of Maine Coon cats

- the 1945 US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- the number of, and the work of local philanthropic institutions

- the weather over the summer months

- the history of companion planting

- how to set up a new password

- how to work a washing machine

Click this link if you'd like more informative topic suggestions . You'll find hundreds of them.

And this link to find out more about the 4 types of informative speeches : definition, description, demonstration and explanation. (Each with an example outline and topic suggestions.)

Demonstration, demonstrative or 'how to' speeches

A demonstration speech is an extension of an informative process speech. It's a 'how to' speech, combining informing with demonstrating.

The topic process, (what the speech is about), could either be demonstrated live or shown using visual aids.

The goal of a demonstrative speech is to teach a complete process step by step.

It's found everywhere, all over the world: in corporate and vocational training rooms, school classrooms, university lecture theatres, homes, cafes... anywhere where people are either refreshing or updating their skills. Or learning new ones.

Knowing to how give a good demonstration or 'how to' speech is a very valuable skill to have, one appreciated by everybody.

Examples of 'how to' speech topics are:

- how to braid long hair

- how to change a car tire

- how to fold table napkins

- how to use the Heimlich maneuver

- how to apply for a Federal grant

- how to fill out a voting form

- how to deal with customer complaints

- how to close a sale

- how to give medicine to your cat without being scratched to bits!

Resources for demonstration speeches

1 . How to write a demonstration speech Guidelines and suggestions covering:

- choosing the best topic : one aligning with your own interests, the audience's, the setting for the speech and the time available to you

- how to plan, prepare and deliver your speech - step by step guidelines for sequencing and organizing your material plus a printable blank demonstration speech outline for you to download and complete

- suggestions to help with delivery and rehearsal . Demonstration speeches can so easily lurch sideways into embarrassment. For example: forgetting a step while demonstrating a cake recipe which means it won't turn out as you want it to. Or not checking you've got everything you need to deliver your speech at the venue and finding out too late, the very public and hard way, that the lead on your laptop will not reach the only available wall socket. Result. You cannot show your images.

2. Demonstration speech sample outline This is a fully completed outline of a demonstration speech. The topic is 'how to leave an effective voice mail message' and the sample covers the entire step by step sequence needed to do that.

There's a blank printable version of the outline template to download if you wish and a YouTube link to a recording of the speech.

3. Demonstration speech topics 4 pages of 'how to' speech topic suggestions, all of them suitable for middle school and up.

Persuasive speeches

The goal of a persuasive speech is to convince an audience to accept, or at the very least listen to and consider, the speaker's point of view.

To be successful the speaker must skillfully blend information about the topic, their opinion, reasons to support it and their desired course of action, with an understanding of how best to reach their audience.

Everyday examples of persuasive speeches

Common usages of persuasive speeches are:

- what we say when being interviewed for a job

- presenting a sales pitch to a customer

- political speeches - politicians lobbying for votes,

- values or issue driven speeches e.g., a call to boycott a product on particular grounds, a call to support varying human rights issues: the right to have an abortion, the right to vote, the right to breathe clean air, the right to have access to affordable housing and, so on.

Models of the persuasive process

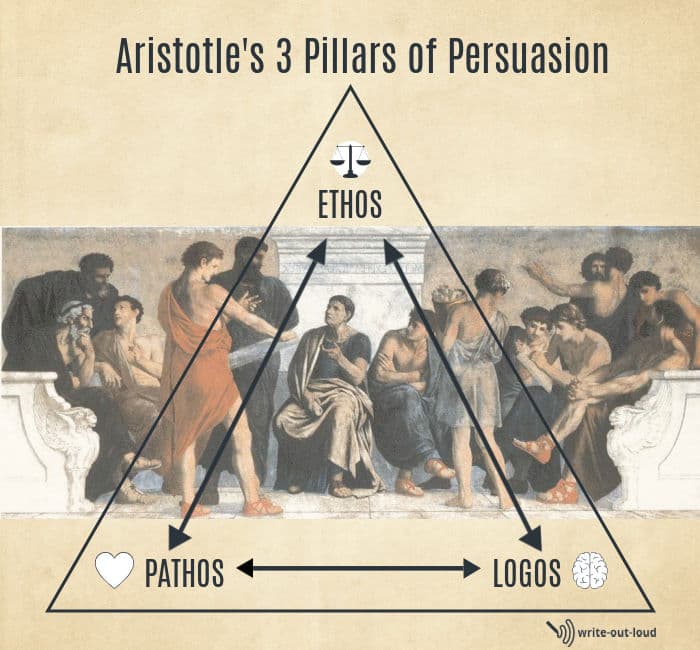

The most frequently cited model we have for effective persuasion is thousands of years old. Aristotle, the Greek philosopher, 384–322 BC , explained it as being supported by three pillars: ethos, pathos and logos.

Briefly, ethos is the reliability and credibility of the speaker. How qualified or experienced are they talk on the topic? Are they trustworthy? Should we believe them? Why?

Pathos is the passion, emotion or feeling you, the speaker, bring to the topic. It's the choice of language you use to trigger an emotional connection linking yourself, your topic and the audience together, in a way that supports your speech purpose.

(We see the echo of Pathos in words like empathy: the ability to understand and share the feels of another, or pathetic: to arouse feelings of pity through being vulnerable and sad.)

Logos is related to logic. Is the information we are being presented logical and rational? Is it verifiable? How is it supported? By studies, by articles, by endorsement from suitably qualified and recognized people?

To successfully persuade all three are needed. For more please see this excellent article: Ethos, Pathos, Logos: 3 Pillars of Public Speaking and Persuasion

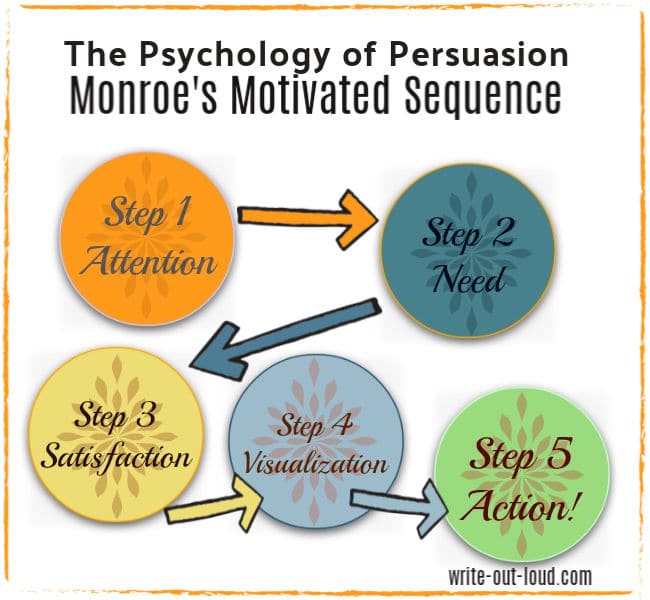

Monroe's Motivated Sequence of persuasion

Another much more recent model is Monroe's Motivated Sequence based on the psychology of persuasion.

It consists of five consecutive steps: attention, need, satisfaction, visualization and action and was developed in the 1930s by American Alan H Monroe, a lecturer in communications at Purdue University. The pattern is used extensively in advertising, social welfare and health campaigns.

Resources for persuasive speeches

1. How to write a persuasive speech Step by step guidelines covering:

- speech topic selection

- setting speech goals

- audience analysis

- empathy and evidence

- balance and obstacles

- 4 structural patterns to choose from

2. A persuasive speech sample outline using Monroe's Motivated Sequence

3. An example persuasive speech written using Monroe's Motivated Sequence

4. Persuasive speech topics : 1032+ topic suggestions which includes 105 fun persuasive ideas , like the one below.☺

Special occasion or entertaining speeches

The range of these speeches is vast: from a call 'to say a few words' to delivering a lengthy formal address.

This is the territory where speeches to mark farewells, thanksgiving, awards, birthdays, Christmas, weddings, engagements and anniversaries dwell, along with welcome, introduction and thank you speeches, tributes, eulogies and commencement addresses.

In short, any speech, either impromptu or painstakingly crafted, given to acknowledge a person, an achievement, or an event belongs here.

You'll find preparation guidelines, as well as examples of many special occasion speeches on my site.

Resources for special occasion speeches

How to prepare:

- an acceptance speech , with an example acceptance speech

- a birthday speech , with ongoing links to example 18th, 40th and 50th birthday speeches

- an office party Christmas speech , a template with an example speech

- an engagement party toast , with 5 examples

- a eulogy or funeral speech , with a printable eulogy planner and access to 70+ eulogy examples

- a farewell speech , with an example (a farewell speech to colleagues)

- a golden (50th) wedding anniversary speech , with an example speech from a husband to his wife

- an impromptu speech , techniques and templates for impromptu speaking, examples of one minute impromptu speeches with a printable outline planner, plus impromptu speech topics for practice

- an introduction speech for a guest speaker , with an example

- an introduction speech for yourself , with an example

- a maid of honor speech for your sister , a template, with an example

- a retirement speech , with an example from a teacher leaving to her students and colleagues

- a student council speech , a template, with an example student council president, secretary and treasurer speech

- a Thanksgiving speech , a template, with an example toast

- a thank you speech , a template, with an example speech expressing thanks for an award, also a business thank you speech template

- a tribute (commemorative) speech , with a template and an example speech

- a welcome speech for an event , a template, an example welcome speech for a conference, plus a printable welcome speech planner

- a welcome speech for new comers to a church , a template with an example speech

- a welcome speech for a new member to the family , a template with an example

Speech types often overlap

Because speakers and their speeches are unique, (different content, purposes, and audiences...), the four types often overlap. While a speech is generally based on one principal type it might also have a few of the features belonging to any of the others.

For example, a speech may be mainly informative but to add interest, the speaker has used elements like a demonstration of some sort, persuasive language and the brand of familiar humor common in a special occasion speech where everybody knows each other well.

The result is an informative 'plus' type of speech. A hybrid! It's a speech that could easily be given by a long serving in-house company trainer to introduce and explain a new work process to employees.

Related pages:

- how to write a good speech . This is a thorough step by step walk through, with examples, of the general speech writing process. It's a great place to start if you're new to writing speeches. You'll get an excellent foundation to build on.

- how to plan a speech - an overview of ALL the things that need to be considered before preparing an outline, with examples

- how to outline a speech - an overview, with examples, showing how to structure a speech, with a free printable blank speech outline template to download

- how to make and use cue cards - note cards for extemporaneous speeches

- how to use props (visual aids)

And for those who would like their speeches written for them:

- commission me to write for you

speaking out loud

Subscribe for FREE weekly alerts about what's new For more see speaking out loud

Top 10 popular pages

- Welcome speech

- Demonstration speech topics

- Impromptu speech topic cards

- Thank you quotes

- Impromptu public speaking topics

- Farewell speeches

- Phrases for welcome speeches

- Student council speeches

- Free sample eulogies

From fear to fun in 28 ways

A complete one stop resource to scuttle fear in the best of all possible ways - with laughter.

Useful pages

- Search this site

- About me & Contact

- Free e-course

- Privacy policy

©Copyright 2006-24 www.write-out-loud.com

Designed and built by Clickstream Designs

Learn The Types

Learn About Different Types of Things and Unleash Your Curiosity

Types of Speeches: A Guide to Different Styles and Formats

Speeches are a powerful way to communicate ideas, inspire people, and create change. There are many different types of speeches, each with its own unique characteristics and formats. In this article, we’ll explore some of the most common types of speeches and how to prepare and deliver them effectively.

1. Informative Speech

An informative speech is designed to educate the audience on a particular topic. The goal is to provide the audience with new information or insights and increase their understanding of the topic. The speech should be well-researched, organized, and delivered in a clear and engaging manner.

2. Persuasive Speech

A persuasive speech is designed to convince the audience to adopt a particular viewpoint or take action. The goal is to persuade the audience to agree with the speaker’s perspective and take action based on that belief. The speech should be well-researched, organized, and delivered in a passionate and compelling manner.

3. Entertaining Speech

An entertaining speech is designed to entertain the audience and create a memorable experience. The goal is to engage the audience and make them laugh, cry, or think deeply about a particular topic. The speech can be humorous, inspirational, or emotional and should be delivered in a lively and engaging manner.

4. Special Occasion Speech

A special occasion speech is designed for a specific event or occasion, such as a wedding, graduation, or retirement party. The goal is to celebrate the occasion and honor the people involved. The speech should be personal, heartfelt, and delivered in a sincere and respectful manner.

5. Impromptu Speech

An impromptu speech is delivered without any preparation or planning. The goal is to respond quickly and effectively to a particular situation or question. The speech should be delivered in a clear and concise manner and address the topic at hand.

In conclusion, speeches are an important way to communicate ideas, inspire people, and create change. By understanding the different types of speeches and their unique characteristics and formats, individuals can prepare and deliver successful speeches that are engaging, informative, and memorable.

You Might Also Like:

Patio perfection: choosing the best types of pavers for your outdoor space, a guide to types of pupusas: delicious treats from central america, exploring modern period music: from classical to jazz and beyond.

Understanding Different Types of Speeches and Their Purposes

Public speaking is an essential skill that can open doors, influence opinions, and convey vital information. Understanding the different types of speeches and how to craft them effectively can significantly enhance one's communication skills. Whether you're presenting an informative lecture, persuading an audience, or celebrating a special occasion, knowing which type of speech to use and how to deliver it is crucial. This guide will walk you through the distinct types of speeches, offering valuable insights and practical tips to enhance your speech delivery.

Informative Speeches: Sharing Knowledge Effectively

Informative speeches aim to educate the audience by providing them with knowledge on a particular subject. The informative speech's purpose is to share one's knowledge clearly and concisely, ensuring that the audience walks away with a better understanding of the topic. These speeches are often used in academic settings, business environments, and local community groups.

- Classroom Lectures : Teachers use informative speeches to introduce new concepts to students. These informative speeches vary widely depending on the subject, from history lessons to scientific theories.

- Business Presentations : Company employees might give informative speeches to share updates on the latest project or explain new policies.

- Informative Presentations at Community Groups : Individuals might speak about topics of interest, such as healthy living or local history, to provide valuable information to group members.

Key Elements:

- Clarity : The information presented should be clear and understandable.

- Credible Sources : Support your speech with credible evidence and sources to build trust with the audience.

- Visual Aids : Use visual aids like slides or charts to help illustrate key points and make the information more engaging.

Tip : When preparing an informative speech, focus on simplifying complex theories. Break down ambiguous ideas into more manageable pieces of information. Use examples and relatable scenarios to make the content more accessible to your audience.

Persuasive Speeches: Influencing Beliefs and Actions

Persuasive speeches are designed to convince the audience to adopt a particular point of view or take a specific action. Unlike informative speeches that merely share information, persuasive speeches actively aim to change the listener's beliefs or behaviors. Persuasive speech writing often involves critical thinking and appeals to emotions, making them powerful tools in public speeches.

- Political Speeches : Politicians often use persuasive speeches to influence public opinion and gain support for their policies.

- Debate Speech : In a debate setting, speakers use persuasive language and evidence to argue a particular issue, focusing on presenting a convincing argument backed by facts and logic.

- Campaign Pitches : Candidates running for office or promoting a cause use pitch speeches to rally support and convince the audience to back their initiatives.

Techniques:

- Factual Evidence : Support your arguments with data, statistics, and credible sources to build a strong case.

- Emotional Appeal: Connect with the audience on an emotional level to make your message more impactful.

- Convincing Tone : Use a confident and assertive tone to convey conviction in your message.

Tip : When delivering a persuasive speech, focus on the audience's beliefs and values. Tailor your message to resonate with their concerns and interests, making it more likely that they'll be persuaded by your argument.

Demonstrative Speeches: Showing How It's Done

Demonstrative speeches are instructional and focus on showing the audience how to do something through a step-by-step process. The primary purpose of a demonstrative speech is to provide a clear understanding of how to perform a specific task, making it a valuable skill in educational and training contexts. A demonstrative speech utilizes visual aids and hands-on examples to enhance learning.

Examples of Demonstrative Speeches:

- Cooking Classes : A chef might give a demonstrative speech on how to prepare a specific dish, such as Mediterranean cooking, showing each step of the process.

- How-To Workshops : Professionals may offer workshops to demonstrate techniques in fields like carpentry, art, or technology.

- Educational Demonstrations : Teachers use demonstrative speeches to explain scientific experiments or procedures.

Key Aspects:

- Physical Demonstration : Showing the steps visually helps the audience follow along and understand better.

- Clear Instructions : Provide detailed explanations for each step to avoid confusion.

- Visual Aids : Use props, tools, or presentation slides to support the demonstration.

Tip : Incorporate visual aids to enhance your demonstrative speech. They can help illustrate the steps more clearly, making it easier for the audience to follow and replicate the task.

Oratorical Speeches: The Art of Powerful Delivery

Oratorical speeches are formal speeches delivered with eloquence and often emphasize powerful rhetoric and grand style. These speeches are common in events that celebrate significant moments, such as inaugurations, memorials, or public celebrations. The main speaker's goal in an oratorical speech is to captivate and inspire the audience through their choice of words and delivery style.

- Inauguration Ceremonies : Leaders deliver oratorical speeches to set the tone for their leadership and outline their vision.

- Commemorative Events : During memorials or national holidays, speakers use oratorical speeches to honor significant historical figures or events.

- Public Celebrations : At large gatherings, speakers deliver oratorical speeches to motivate and unify the community.

- Eloquent Language : Use of rich, powerful language to engage the audience.

- Rhetorical Devices : Employing techniques like repetition, metaphors, and analogies to emphasize key points.

- Strong Deliver y: A commanding presence and vocal variety are crucial to maintaining the audience's attention.

Tip : Practice delivering your speech with emotion and passion. Focus on your body language, voice modulation, and eye contact to make a lasting impression on your audience.

Motivational Speeches: Inspiring the Audience

Motivational speeches are designed to inspire and encourage the audience to take action or improve their lives. These speeches often draw on personal experiences, stories of overcoming obstacles, and positive affirmations to motivate listeners.

- Commencement Addresses : Often delivered to college students, motivational speeches during graduation ceremonies encourage them to pursue their dreams and face challenges head-on.

- Corporate Events : Motivational speakers might inspire employees to embrace change, enhance productivity, or foster teamwork.

- Personal Development Seminars : Individuals attend these seminars to gain insights on self-improvement and personal growth.

- Inspiration : Focus on sharing stories or messages that ignite passion and drive.

- Connection : Establish a personal connection with the audience to make the message more relatable.

- Actionable Steps : Provide practical advice or steps the audience can take to apply the motivation in their lives.

Tip : When crafting a motivational speech, focus on genuine stories and experiences. Authenticity can have a more profound impact than generalized advice.

Entertaining Speeches: Engaging and Amusing the Audience

Entertaining speeches aim to amuse and engage the audience, often through humor, storytelling , or personal anecdotes. These speeches are typically delivered in informal settings where the goal is to entertain rather than inform or persuade.

- Wedding Toasts : Friends or family members give lighthearted speeches to celebrate the newlyweds.

- Talent Show Introductions : Hosts use entertaining speeches to introduce performers and keep the audience engaged.

- After-Dinner Speeches : Delivered at social gatherings, these speeches provide entertainment and often include humorous observations or stories.

- Humor : Use jokes or funny anecdotes to keep the audience entertained.

- Personal Stories : Sharing personal experiences can make the speech more relatable and engaging.

- Audience Interaction : Engage with the audience by asking questions or encouraging participation.

Tip : To deliver a successful entertaining speech, keep the tone light and relatable. Consider the audience's mood and interests, and tailor your content to fit the occasion.

Special Occasion Speeches: Marking Important Events

Special occasion speeches are crafted to honor a particular event, person, or milestone. These speeches are often given during significant moments, such as award ceremonies, weddings, or anniversaries, where the main goal is to celebrate or commemorate. Special occasion speeches can vary widely in tone and style, depending on the nature of the event and the relationship between the speaker and the honoree.

- Acceptance Speeches : Recipients of awards or honors express gratitude and acknowledge those who supported them.

- Wedding Toasts : Speeches given by the best man or maid of honor to celebrate the couple's journey.

- Speeches at Award Ceremonies : Honoring the achievements of individuals or groups and highlighting their contributions.

How to Deliver Special Occasion Speeches:

- Emotional Connection : Connect with the audience by expressing genuine emotions and heartfelt sentiments.

- Balance : Find the right balance between personal anecdotes and the significance of the event.

- Focus on the Main Point : Highlight the core purpose of the event, whether it's celebrating a person's achievements or commemorating a milestone.

Tip : When delivering a special occasion speech, focus on conveying emotions that resonate with the event's atmosphere. Share personal experiences or stories that highlight the significance of the occasion.

Impromptu Speeches: Speaking Off-the-Cuff

Impromptu speeches are delivered without prior preparation, often in response to spontaneous situations. They require quick thinking and the ability to communicate ideas clearly on the spot, making them an essential skill in both professional and personal settings.

- Responding to Unexpected Questions : Handling questions during a Q&A session.

- Speaking at Volunteer Activities : Giving a short speech to thank volunteers or recognize their efforts.

- Community Events : Offering remarks at a local gathering or event.

Tips for Delivering Impromptu Speeches:

- Stay Calm : Take a deep breath and collect your thoughts before speaking.

- Organize Your Ideas : Focus on a few key points to keep your speech structured.

- Be Authentic : Speak from the heart and be genuine in your delivery.

Tip : Practice impromptu speaking regularly to build confidence. Use prompts or scenarios to simulate spontaneous speaking situations, helping you become more comfortable with thinking on your feet.

How to Choose the Right Type of Speech for Your Situation

Selecting the appropriate type of speech depends on the audience, purpose, and context. It's essential to analyze these factors before deciding on the speech format:

- Audience Analysis : Consider the audience's interests, knowledge level, and expectations. Tailor your speech to resonate with them.

- Purpose : Determine whether the goal is to inform, persuade, entertain, or commemorate. This will guide the structure and content of your speech.

- Context : Consider the setting and occasion. For example, a formal event might require a more structured informative or persuasive speech, while a casual gathering might call for an entertaining or impromptu speech.

Examples of Blending Speech Types:

- Combining Informative and Persuasive: A speaker at a health seminar might provide informative details about a health issue and persuade the audience to adopt healthier habits.

- Mixing Entertaining and Special Occasion : A keynote speaker at a wedding might blend humor with heartfelt sentiments to engage the audience while celebrating the couple.

Using Teleprompters for Different Types of Speeches

When delivering a speech, especially in a formal setting or a high-stakes event, using a teleprompter can be a great tool for maintaining a smooth and engaging presentation. A teleprompter displays the speech text on a transparent screen, positioned in front of the speaker, ensuring that they maintain eye contact with the audience while following their script. This technique is widely used across various types of speeches, from informative speeches in business presentations to motivational speeches at large events.

Advantages of Using Teleprompters:

- Confidence and Flow : Teleprompters help speakers stay on track, reducing the risk of losing their place or forgetting key points.

- Engagement : By allowing speakers to maintain eye contact with the audience, teleprompters enhance engagement and make the speech more impactful.

- Professional Delivery : Teleprompters ensure that the speech is delivered as planned, without unnecessary pauses or deviations, contributing to a more polished presentation.

Mastering the Types of Speeches

Understanding and mastering the different types of speeches can significantly enhance your public speaking skills. From informative speeches that educate to persuasive speeches that inspire action, each type plays a unique role in effective communication. Practice these types regularly, and don't hesitate to experiment with blending different styles to suit your needs. By honing your skills in various speech types, you can become a more versatile and confident speaker, capable of captivating any audience.

Recording videos is hard. Try Teleprompter.com

Recording videos without a teleprompter is like sailing without a compass..

Related Articles

Understand the different types of speeches and how to deliver them effectively. Get tips for informative, persuasive, motivational, and more speech styles.

Creative Vlog Ideas for Beginners

Get inspired with creative vlog ideas for beginners! From personal vlogs to educational content, find fresh & engaging YouTube video ideas.

Since 2018 we’ve helped 1M+ creators smoothly record 17,000,000 + videos

Effortlessly record videos and reduce your anxiety so you can level up the quality of your content creation

The best Teleprompter software on the market for iOS.

Address: Budapest Podmaniczky utca 57. II. em. 14. 1064 🇭🇺 Contact:

Subject Libguide: Speech Communication: Types of speeches

- Writing a Speech

- Effective communication

- Additional Resources

- Public Domain Images & Creative Commons

- Evaluating Resources This link opens in a new window

- APA Format This link opens in a new window

- Multi-search Database and ebooks guide This link opens in a new window

- Featured online books This link opens in a new window

A persuasive speech tries to influence or reinforce the attitudes, beliefs, or behavior of an audience. This type of speech often includes the following elements:

- appeal to the audience

- appeal to the reasoning of the audience

- focus on the relevance of your topic

- alligns the speech to the audience - ensure they understand the information expressed

An informative speech is one that informs the audience. These types of speeches can be on a variety of topics:

A informative speech will:

- define terms to make the information more precise

- use descriptions to help the audience towards a larger picture

- include an demonstration

- explain concept the informative speech is conveying

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Writing a Speech >>

- Last Updated: Nov 6, 2020 3:03 PM

- URL: https://mccollege.libguides.com/speech

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: The Speech Communication Process

The Speech Communication Process

- Listener(s)

Interference

As you might imagine, the speaker is the crucial first element within the speech communication process. Without a speaker, there is no process. The speaker is simply the person who is delivering, or presenting, the speech. A speaker might be someone who is training employees in your workplace. Your professor is another example of a public speaker as s/he gives a lecture. Even a stand-up comedian can be considered a public speaker. After all, each of these people is presenting an oral message to an audience in a public setting. Most speakers, however, would agree that the listener is one of the primary reasons that they speak.

The listener is just as important as the speaker; neither one is effective without the other. The listener is the person or persons who have assembled to hear the oral message. Some texts might even call several listeners an “audience. ” The listener generally forms an opinion as to the effectiveness of the speaker and the validity of the speaker’s message based on what they see and hear during the presentation. The listener’s job sometimes includes critiquing, or evaluating, the speaker’s style and message. You might be asked to critique your classmates as they speak or to complete an evaluation of a public speaker in another setting. That makes the job of the listener extremely important. Providing constructive feedback to speakers often helps the speaker improve her/his speech tremendously.

Another crucial element in the speech process is the message. The message is what the speaker is discussing or the ideas that s/he is presenting to you as s/he covers a particular topic. The important chapter concepts presented by your professor become the message during a lecture. The commands and steps you need to use, the new software at work, are the message of the trainer as s/he presents the information to your department. The message might be lengthy, such as the President’s State of the Union address, or fairly brief, as in a five-minute presentation given in class.

The channel is the means by which the message is sent or transmitted. Different channels are used to deliver the message, depending on the communication type or context. For instance, in mass communication, the channel utilized might be a television or radio broadcast. The use of a cell phone is an example of a channel that you might use to send a friend a message in interpersonal communication. However, the channel typically used within public speaking is the speaker’s voice, or more specifically, the sound waves used to carry the voice to those listening. You could watch a prerecorded speech or one accessible on YouTube, and you might now say the channel is the television or your computer. This is partially true. However, the speech would still have no value if the speaker’s voice was not present, so in reality, the channel is now a combination of the two -the speaker’s voice broadcast through an electronic source.

The context is a bit more complicated than the other elements we have discussed so far. The context is more than one specific component. For example, when you give a speech in your classroom, the classroom, or the physical location of your speech, is part of the context . That’s probably the easiest part of context to grasp.

But you should also consider that the people in your audience expect you to behave in a certain manner, depending on the physical location or the occasion of the presentation . If you gave a toast at a wedding, the audience wouldn’t be surprised if you told a funny story about the couple or used informal gestures such as a high-five or a slap on the groom’s back. That would be acceptable within the expectations of your audience, given the occasion. However, what if the reason for your speech was the presentation of a eulogy at a loved one’s funeral? Would the audience still find a high-five or humor as acceptable in that setting? Probably not. So the expectations of your audience must be factored into context as well.

The cultural rules -often unwritten and sometimes never formally communicated to us -are also a part of the context. Depending on your culture, you would probably agree that there are some “rules ” typically adhered to by those attending a funeral. In some cultures, mourners wear dark colors and are somber and quiet. In other cultures, grieving out loud or beating one’s chest to show extreme grief is traditional. Therefore, the rules from our culture -no matter what they are -play a part in the context as well.

Every speaker hopes that her/his speech is clearly understood by the audience. However, there are times when some obstacle gets in the way of the message and interferes with the listener’s ability to hear what’s being said. This is interference , or you might have heard it referred to as “noise. ” Every speaker must prepare and present with the assumption that interference is likely to be present in the speaking environment.

Interference can be mental, physical, or physiological. Mental interference occurs when the listener is not fully focused on what s/he is hearing due to her/his own thoughts. If you’ve ever caught yourself daydreaming in class during a lecture, you’re experiencing mental interference. Your own thoughts are getting in the way of the message.

A second form of interference is physical interference . This is noise in the literal sense -someone coughing behind you during a speech or the sound of a mower outside the classroom window. You may be unable to hear the speaker because of the surrounding environmental noises.

The last form of interference is physiological . This type of interference occurs when your body is responsible for the blocked signals. A deaf person, for example, has the truest form of physiological interference; s/he may have varying degrees of difficulty hearing the message. If you’ve ever been in a room that was too cold or too hot and found yourself not paying attention, you’re experiencing physiological interference. Your bodily discomfort distracts from what is happening around you.

The final component within the speech process is feedback. While some might assume that the speaker is the only one who sends a message during a speech, the reality is that the listeners in the audience are sending a message of their own, called feedback . Often this is how the speaker knows if s/he is sending an effective message. Occasionally the feedback from listeners comes in verbal form – questions from the audience or an angry response from a listener about a key point presented. However, in general, feedback during a presentation is typically non-verbal -a student nodding her/his head in agreement or a confused look from an audience member. An observant speaker will scan the audience for these forms of feedback, but keep in mind that non-verbal feedback is often more difficult to spot and to decipher. For example, is a yawn a sign of boredom, or is it simply a tired audience member?

Generally, all of the above elements are present during a speech. However, you might wonder what the process would look like if we used a diagram to illustrate it. Initially, some students think of public speaking as a linear process -the speaker sending a message to the listener -a simple, straight line. But if you’ll think about the components we’ve just covered, you begin to see that a straight line cannot adequately represent the process, when we add listener feedback into the process. The listener is sending her/his own message back to the speaker, so perhaps the process might better be represented as circular. Add in some interference and place the example in context, and you have a more complete idea of the speech process.

Fundamentals of Public Speaking Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

10 Types of Speeches Every Speechwriter Should Know

“Speech is power. Speech is to persuade, to convert, to compel.” — Ralph Waldo Emmerson

Many events in human history can be traced back to that one well-written , well-presented speech. Speeches hold the power to move nations or touch hearts as long as they’re well thought out. This is why mastering the skill of speech-giving and speech writing is something we should all aim to achieve.

But the word “speech” is often too broad and general. So let’s explore the different types of speeches and explain their general concepts.

Basic Types of Speeches

While the core purpose is to deliver a message to an audience, we can still categorize speeches based on 4 main concepts: entertaining, informing, demonstrating and persuading.

The boundaries between these types aren’t always obvious though, so the descriptions are as clear as possible in order to differentiate between them.

1. Entertaining Speech

If you’ve been to a birthday party before, that awkward toast given by friends or family of the lucky birthday person is considered to fall under the definition of an entertaining speech .

The core purpose of an entertaining speech is to amuse the audience, and obviously, entertain them. They’re usually less formal in nature to help communicate emotions rather than to simply talk about a couple of facts.

Let’s face it, we want to be entertained after a long day. Who wouldn’t enjoy watching their favorite actors giving an acceptance speech , right?

You’ll find that entertaining speeches are the most common type of speeches out there. Some examples include speeches given by maids of honor or best men at weddings, acceptance speeches at the Oscars, or even the one given by a school’s principal before or after a talent show.

2. Informative Speech

When you want to educate your audience about a certain topic, you’ll probably opt to create an informative speech . An informative speech’s purpose is to simplify complex theories into simpler, easier-to-digest and less ambiguous ideas; in other words, conveying information accurately.

The informative speech can be thought of as a polar opposite to persuasive speeches since they don’t relate to the audience’s emotions but depend more on facts, studies, and statistics.

Although you might find a bit of overlap between informative and demonstrative speeches, the two are fairly distinct from one another. Informative speeches don’t use the help of visual aids and demonstrations, unlike demonstrative speeches, which will be described next.

Some examples of informative speeches can be speeches given by staff members in meetings, a paleontology lecture, or just about anything from a teacher (except when they’re telling us stories about their pasts).

3. Demonstrative Speech

ِFrom its name we can imagine that a demonstrative speech is the type of speech you want to give to demonstrate how something works or how to do a certain thing. A demonstrative speech utilizes the use of visual aids and/or physical demonstration along with the information provided.

Some might argue that demonstrative speeches are a subclass of informative speeches, but they’re different enough to be considered two distinct types. It’s like differentiating between “what is” and “how to”; informative speeches deal with the theoretical concept while demonstrative speeches look at the topic with a more practical lens.

Tutors explaining how to solve mathematical equations, chefs describing how to prepare a recipe, and the speeches given by developers demonstrating their products are all examples of demonstrative speeches.

4. Persuasive Speech

Persuasive speeches are where all the magic happens. A speech is said to be persuasive if the speaker is trying to prove why his or her point of view is right, and by extension, persuade the audience to embrace that point of view.

Persuasive speeches differ from other basic types of speeches in the sense that they can either fail or succeed to achieve their purpose. You can craft the most carefully written speech and present it in the most graceful manner, yet the audience might not be convinced.

Persuasive speeches can either be logical by using the help of facts or evidence (like a lawyer’s argument in court), or can make use of emotional triggers to spark specific feelings in the audience.

A great example of persuasive speeches is TED / TEDx Talks because a big number of these talks deal with spreading awareness about various important topics. Another good example is a business pitch between a potential client, i.e. “Why we’re the best company to provide such and such.”

Other Types of Speeches

Other types of speeches are mixes or variations of the basic types discussed previously but deal with a smaller, more specific number of situations.

5. Motivational Speech

A motivational speech is a special kind of persuasive speech, where the speaker encourages the audience to pursue their own well-being. By injecting confidence into the audience, the speaker is able to guide them toward achieving the goals they set together.

A motivational speech is more dependent on stirring emotions instead of persuasion with logic. For example, a sports team pep talk is considered to be a motivational speech where the coach motivates his players by creating a sense of unity between one another.

One of the most well-known motivational speeches (and of all speeches at that) is I Have a Dream by Martin Luther King Jr.

6. Impromptu Speech

Suppose you’re at work, doing your job, minding your own business. Then your co-worker calls you to inform you that he’s sick, there is a big meeting coming up, and you have to take his place and give an update about that project you’ve been working on.

What an awkward situation, right?

Well, that’s what an impromptu speech is: A speech given on the spot without any prior planning or preparation. It being impromptu is more of a property than a type on its own since you can spontaneously give speeches of any type (not that it’s a good thing though; always try to be prepared for your speeches in order for them to be successful).

Mark Twain once said, “It usually takes me more than three weeks to prepare a good impromptu speech.”

7. Oratorical Speech

This might sound a bit counterintuitive at first since the word oratorical literally means “relating to the act of speech-giving” but an oratorical speech is actually a very specific type of speech.

Oratorical speeches are usually quite long and formal in nature. Their purpose could be to celebrate a certain event like a graduation, to address serious issues and how to deal with them, or to mourn losses and give comfort like a eulogy at a funeral.

8. Debate Speech

The debate speech has the general structure of a persuasive speech in the sense that you use the same mechanics and figures to support your claim, but it’s distinct from a persuasive speech in that its main purpose is to justify your stance toward something rather than convince the audience to share your views.

Debate speeches are mostly improvised since you can’t anticipate all the arguments the other debaters (or the audience) could throw at you. Debate speeches benefit the speaker since it develops their critical thinking, public speaking, and research among other benefits .

You’ll find debate speeches to be common in public forums, legislative sessions, and court trials.

9. Forensic Speech

According to the American Forensic Association (AFA), the definition of a forensic speech is the study and practice of public speaking and debate. It’s said to be practiced by millions of high school and college students.

It’s called forensic because it’s styled like the competitions held in public forums during the time of the ancient Greeks.

Prior to a forensic speech, students are expected to research and practice a speech about a certain topic to teach it to an audience. Schools, universities, or other organizations hold tournaments for these students to present their speeches.

10. Special Occasion Speech

If your speech doesn’t fall under any of the previous types, then it probably falls under the special occasion speech . These speeches are usually short and to the point, whether the point is to celebrate a birthday party or introduce the guest of honor to an event.

Special occasion speeches can include introductory speeches, ceremonial speeches, and tributary speeches. You may notice that all these can be categorized as entertaining speeches. You’re right, they’re a subtype of entertaining speeches because they neither aim to teach nor to persuade you.

But this type shouldn’t be viewed as the black sheep of the group; in fact, if you aim to mark a significant event, special occasion speeches are your way to go. They are best suited (no pun intended) for a wedding, a bar mitzvah, or even an office party.

If you’ve reached this far, you should now have a general understanding of what a speech is and hopefully know which type of speech is needed for each occasion. I hope you’ve enjoyed and learned something new from this article. Which type will you use for your next occasion?

Photo by Forja2 Mx on Unsplash

Musings and updates from the content management team at Clippings.me.

4 Main Types of Speeches in Public Speaking (With Examples)

We live in a world where communication is king.

With social media and all the digital stuff, we’re bombarded with information constantly, and everyone is fighting for our attention.

Research shows that our attention spans have declined from 12 seconds to just 8.25 seconds in the past 15 years, even shorter than a goldfish’s attention span.

So, the point is being able to get your point across quickly and effectively is a big deal. That’s where the invaluable skill of public speaking comes in handy.

But being a great speaker goes beyond just having confidence. It’s about understanding different kinds of speeches and knowing which one works best for your audience and purpose.

In this blog, we will explore four main types of speeches (or types of public speaking), each with its own purpose and impact. By understanding these types, you can connect with your audience , cater to their needs, and deliver a message that resonates.

So, let’s dive right in:

What is Speech?

Importance of public speaking (7 benefits).

- 4 Main Types of Public Speeches (With Examples)

Other Types of Speeches

Final thoughts.

A speech is a formal or informal presentation in which a person communicates their thoughts, ideas, or information to an audience. It is a spoken expression of thoughts, often delivered in a structured and organized manner.

Speeches can be delivered to serve various purposes, such as to persuade , educate, motivate, or entertain the audience.

People usually give speeches in public places, like meetings, conferences, classrooms, or special events, aiming to connect with and influence the listeners through their words.

A public speech may involve the use of supporting materials, such as visual aids, slides , or props, to enhance understanding and engagement.

The delivery of a speech encompasses not only the words spoken but also factors like the tone of voice, body language , and timing, which can greatly impact the overall effectiveness and reception of the message.

You may want to check out our short video on how to speak without hesitation.

Public speaking is a superpower that transforms your life in more ways than you can imagine.

Here are 7 reasons why Public speaking is an invaluable skill:

- Effective Communication: Being a good public speaker helps you express yourself clearly and confidently. It allows you to share your knowledge, opinions, and ideas in a captivating manner.

- Professional Growth: Mastering public speaking gives you a competitive edge in the job market. It allows you to lead meetings , present ideas, negotiate deals, and pitch projects with confidence.

- Building Confidence: Overcoming the fear of public speaking and delivering successful presentations significantly boosts your self-confidence . With experience, you become more self-assured in various situations, both inside and outside of public speaking.

- Influence and Persuasion: A strong public speaker can inspire, motivate, and influence others. By effectively conveying your message, you can sway opinions, change attitudes, and drive positive change in your personal and professional circles.

- Leadership Development: Public speaking is a crucial skill for effective leadership. It enables you to inspire and guide others, lead meetings and presentations, and rally people around a common goal.

- Personal Development: Public speaking encourages personal growth and self-improvement. It pushes you out of your comfort zone, enhances your critical thinking and problem-solving skills, and helps you become a more well-rounded individual.

- Increased Visibility: The ability to speak confidently in public attracts attention and raises your visibility among peers, colleagues, and potential employers. This can lead to new opportunities, collaborations, and recognition for your expertise.

Public speaking is a vital tool for social change. History has shown us how influential speeches have shaped the world we live in. From Martin Luther King Jr.’s “ I Have a Dream ” speech to Malala Yousafzai’s advocacy for girls’ education, public speaking has been at the forefront of inspiring change. Your words have the power to challenge beliefs, ignite passion, and rally others around a cause. So, if you have a message you want to share or a mission you want to pursue, mastering the art of public speaking is essential.

1. Informative Speech

An informative speech is a type of public speaking that aims to educate or provide information to the audience about a specific topic. The main purpose of this speech is to present facts, concepts, or ideas in a clear and understandable manner.

Delivering an Informative Speech

In an informative speech, the speaker’s objective is to provide knowledge, increase awareness, or explain a subject in detail.

To be informative, you need to structure your content in a way that’s clear and easy to follow. The structure of an informative speech typically includes:

- an introduction where you grab the audience’s attention and introduce the topic

- the body where you present the main points and supporting evidence

- a conclusion where you summarize the key information and emphasize your message.

- a Q&A session or a brief discussion to further deepen their understanding.

Informative speech could be formal or informal speech, depending on the context. However, it is helpful to maintain a conversational tone.

Use relatable examples, anecdotes, or even a touch of humor to keep your audience engaged and interested. Think of it as having a friendly chat with a group of curious friends.

Examples of Informative Speeches:

An Example of Informative Speech

- Academic Settings : Students may deliver presentations to educate their classmates. Teachers or instructors may explain a specific subject to students in schools, colleges, and universities.

- Business and Professional Presentations: In the corporate world, professionals may present information about industry trends, new technologies, market research, or company updates to inform and educate their colleagues or clients.

- Public Events and Conferences: Informative speeches are prevalent in public events and conferences where experts and thought leaders share their knowledge and insights with a broader audience.

- Ted Talks and Similar Platforms: TED speakers design their speeches to educate, inspire, and spread ideas that have the potential to make a positive impact on society.

- Community Gatherings: Informative speeches can be delivered at community gatherings where speakers may inform the community about local issues, government policies, or initiatives aimed at improving the community’s well-being.

The beauty of informative speeches is their versatility; they can be adapted to different settings and tailored to suit the needs and interests of the audience.

2. Demonstrative Speech

In a demonstrative speech, the main goal is to show how to do something or how something works. It is like giving a step-by-step guide or providing practical instructions.

The purpose of a demonstrative speech is to educate or inform the audience about a specific process, task, or concept.

It can be about anything that requires a demonstration, such as cooking a recipe, performing a science experiment, using a software program, or even tying a tie.

The key to a successful demonstrative speech is to be organized and concise.

When preparing for a demonstrative speech, you need to break down the process or technique into clear and easy-to-follow steps.

You need to make sure that your audience can grasp the concepts and replicate the actions themselves. Visual aids like props, slides, or even live demonstrations are incredibly helpful in illustrating your points.

A great demonstrative speech not only teaches but also inspires.

You need to ignite a sense of enthusiasm and curiosity in your audience . Encourage them to try it out themselves and apply what they’ve learned in their own lives.

Examples of Demonstrative Speeches:

An Example of Demonstrative Speech

- Educational Settings: Demonstrative speeches are often used in classrooms, workshops, or training sessions to teach students or participants how to perform specific activities. For instance, a teacher might give a demonstrative speech on how to conduct a science experiment, play a musical instrument, or solve a math problem.

- Professional Training: In the workplace, a trainer might give a demonstrative speech on how to use a new software application, operate a piece of machinery, or follow safety protocols.

- DIY and Home Improvement: Demonstrative speeches are commonly seen in DIY (do-it-yourself) videos, TV shows, or workshops where experts demonstrate how to complete tasks like painting a room, fixing plumbing issues, or building furniture.

- Culinary Demonstrations: Demonstrative speeches are prevalent in the culinary world, where chefs or cooking experts showcase recipes and cooking techniques.

Overall, a demonstrative speech is a practical and hands-on type of speech that aims to educate, inform, and empower the audience by teaching them how to perform a particular task or skill.

3. Persuasive Speech

A persuasive speech is when the speaker tries to convince the audience to adopt or support a particular point of view, belief, or action. In a persuasive speech, the speaker aims to influence the audience’s opinions, attitudes, or behaviors.

You may present arguments and evidence to support your viewpoint and try to persuade the listeners to take specific actions or simply agree with you.

You have to use persuasive techniques such as logical reasoning, emotional appeals, and credibility to make your case.

Let me break it down for you.

- First, you need a clear and persuasive message. Identify your objective and what you want to achieve with your speech. Once you have a crystal-clear goal, you can shape your arguments and craft your speech accordingly.

- Secondly, you need to connect with your audience on an emotional level. You may use stories , anecdotes, and powerful examples to evoke emotions that resonate with your audience.

- Thirdly, you need to present compelling evidence, facts, and logical reasoning to support your arguments. Back up your claims with credible sources and statistics.

- Additionally, the delivery of your speech plays a crucial role in persuasion. Your body language, tone of voice , and overall presence should exude confidence and conviction.

- Lastly, end your persuasive speech with a call to action. Whether it’s signing a petition, donating to a cause, or changing a behavior, make it clear what steps you want your audience to take.

Examples of Persuasive speeches:

An Example of Persuasive Speech

- Political speeches: Politicians ****often deliver persuasive speeches to win support for their policies or convince people to vote for them.

- Sales and marketing presentations: Advertisements ****use persuasive techniques to persuade consumers to buy their products.

- Social issue speeches: Activists, advocates, or community leaders often give persuasive speeches to raise awareness about social issues and mobilize support for a cause.

Effective persuasion helps you win over clients, close deals, and secure promotions.

However, it’s important to note that persuasion should always be used ethically and with integrity. It’s not about manipulating people but rather about creating win-win situations.

4. Entertaining Speech

An entertaining speech is a type of public presentation that aims to captivate and amuse the audience while providing enjoyment and laughter. Unlike other types of speeches, entertaining speeches prioritize humor, storytelling , and engaging content to entertain and delight the listeners.

In an entertaining speech, the speaker uses various techniques such as jokes, anecdotes, funny stories, witty observations, humorous examples, and clever wordplay to engage the audience and elicit laughter.

The primary objective is to entertain and create a positive, lighthearted atmosphere.

An entertaining speech is a powerful tool for building a connection with the audience. It isn’t just about cracking jokes. It’s about using humor strategically to reinforce the main message.

When we’re entertained, our guards come down, and we become more receptive to the speaker’s message. It’s like a spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine go down.

An entertaining speech can be particularly effective when the topic at hand is traditionally considered dull, serious, or sensitive. By infusing humor, you can bring life to the subject matter and help the audience connect with it on a deeper level.

With entertainment, you can make complex concepts more accessible. And also break down barriers that might otherwise discourage people from paying attention.

Delivery and timing are crucial elements in entertaining speeches.

The speaker’s tone, facial expressions, gestures , and voice modulation play a significant role in enhancing the comedic effect.

Effective use of pauses , punchlines, and comedic timing can heighten the audience’s anticipation and result in laughter and amusement.

Examples of Entertaining Speech:

An Example of Entertaining Speech

- Social Events: Entertaining speeches are often seen at social gatherings such as weddings, birthday parties, or anniversary celebrations.

- Conferences or Conventions: In professional conferences or conventions, an entertaining speech can be a refreshing break from the more serious and technical presentations. A speaker may use humor to liven up the atmosphere.

- Stand-up Comedy: Stand-up comedians are prime examples of entertaining speeches. They perform in comedy clubs, theaters, or even on television shows, aiming to make the audience laugh and enjoy their performance.

The content and style of an entertaining speech should be tailored to the audience and the occasion. While humor is subjective, the skilled entertaining speaker knows how to adapt their speech to suit the preferences and sensibilities of the specific audience. By carefully selecting appropriate humor, you can transform a dull or serious setting into an enjoyable experience for the audience.

Beyond the four main types of public speeches we mentioned, there are a few other different types of speeches worth exploring.

- Special Occasion Speeches: These speeches are delivered during specific events or occasions, such as weddings, graduation ceremonies, or award ceremonies. They are meant to honor or celebrate individuals, express congratulations, or provide inspiration and encouragement.

- Motivational Speeches: Motivational speeches aim to inspire and are commonly delivered by coaches, entrepreneurs, or motivational speakers. They often focus on personal development, goal-setting, overcoming obstacles, and achieving success.

- Commemorative Speeches: These speeches are delivered on anniversaries, memorial services, or dedications. These speeches express admiration, highlight achievements, and reflect on the impact of the person or event being commemorated.

- Debate Speeches: Debate speeches involve presenting arguments and evidence to support a particular viewpoint on a topic. They require logical reasoning, persuasive language, and the ability to counter opposing arguments effectively.

- Impromptu Speeches: Impromptu speeches are delivered without prior preparation or planning. You are given a topic or a question on the spot and must quickly organize your thoughts and deliver a coherent speech. These speeches test the speaker’s ability to think on their feet and communicate effectively in spontaneous situations.

- Oratorical Speech: An oratorical speech is a formal and eloquent speech delivered with great emphasis and rhetorical flair. It aims to inspire, persuade, or inform the audience through the skilled use of language and powerful delivery techniques. Oratorical speeches are typically given on significant occasions, such as political rallies, commemorative events, or public ceremonies.

No matter what kind of speech you are giving, pauses play a key role in making it captivating.

Check out our video on how pausing can transform your speeches.

Public speaking is a powerful skill that holds tremendous value in various aspects of our lives. Whether you’re aiming to inform, demonstrate, persuade, or entertain, mastering the art of public speaking can open doors to new opportunities and personal growth.

Growth happens when you push beyond your comfort zones. Public speaking may seem daunting at first, but remember that every great speaker started somewhere. Embrace the challenge and take small steps forward.

Start with speaking in front of friends or family, join a local speaking club, or seek opportunities to present in a supportive environment . Each time you step out of your comfort zone, you grow stronger and more confident.

Seek resources like TED Talks, workshops, books , and podcasts to learn from experienced speakers and improve your skills.

Just like any skill, public speaking requires practice. The more you practice, the more comfortable and confident you will become.

Seek opportunities to speak in public, such as volunteering for presentations or joining public speaking clubs. Embrace every chance to practice and refine your skills.

If you are looking for a supportive environment to practice and hone your public speaking skills, try out BBR English.

Our 1:1 live sessions with a corporate expert are designed to help you improve your communication skills. You’ll gain the confidence and skills you need to communicate effectively in any situation.