education, community-building and change

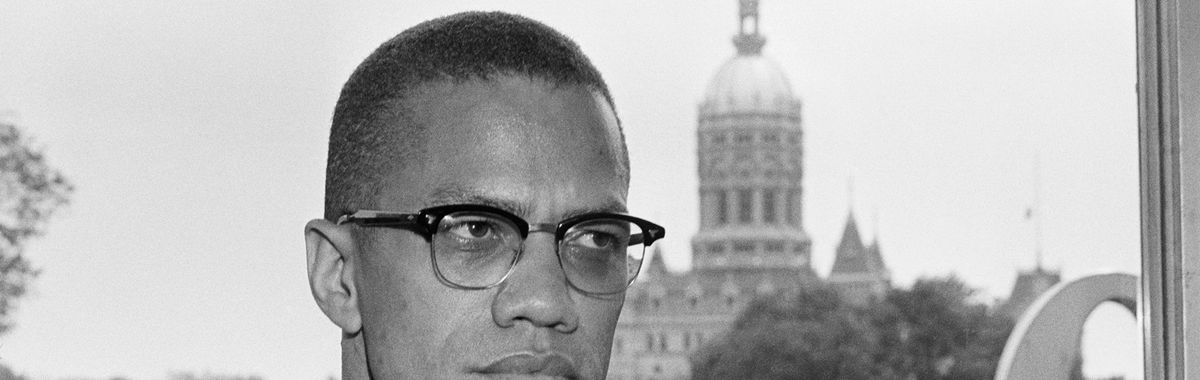

Malcolm X on education

Malcolm x on education. malcolm x is a fascinating person to approach as an educational thinker – not because he was an academic or had any scholastic achievements but as an example of what can be achieved by someone engages in ‘homemade’ or self-education..

contents: introduction · homemade education · conclusion · bibliography · how to cite this article

Malcolm X (1925 – 1965) was born as Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1925. His father was a Baptist minister and a strong devotee of the Black leader Marcus Garvey. Garvey’s message, as many readers will be familiar, was that Black people in America would never be able to live in peace and harmony with white Americans and their only hope of salvation was to move as a people back to their roots in Africa. Malcolm’s father died when he was six and his mother was put in a mental home when he was about twelve. As a result, his many brothers and sisters were split up and put into different foster homes.

Malcolm left school early and eventually drifted North and finally settled in Harlem, New York, on his own, at the age of 17.

In Harlem, he soon slipped into a life of crime. He became involved in hustling, in prostitution, in drug dealing. He became a cocaine addict and a burglar. Finally, at the ripe old age of 19, he was arrested and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment.

It was while he was in prison that his whole life changed. He first learned of the existence of the Honourable Elijah Mohammed and of the movement known as the Black Muslims from his brothers and sisters outside the prison. They had become converts to the movement and asked Malcolm to write to Elijah Mohammed. In Chapter 11 of his autobiography, Malcolm writes that “at least twenty-five times I must have written that first one-page letter to him, over and over. I was trying to make it both legible and understandable. I practically couldn’t read my handwriting myself; it shames me even to remember it. My spelling and my grammar were as bad, if not worse”. This chapter in his autobiography is extremely moving as it documents a man’s desperate pursuit of an education.

Homemade education

Malcolm became a letter writer and as a result he says that he “stumbled upon starting to acquire some kind of homemade education”. He became extremely frustrated at not being able to express what he wanted to convey in letters that he wrote. He says that “in the street I had been the most articulate hustler out there … But now, trying to write simple English, I not only wasn’t articulate, I wasn’t even functional”. His ability to read books was severely hampered. “Every book I picked up had few sentences which didn’t contain anywhere from one to nearly all of the words that might have been in Chinese”. He skipped the words he didn’t know and so had little idea of what the books said.

He got himself a dictionary and began painstakingly copying every entry. It took him a day to do the first page. He would copy it all out and then read back aloud what he had written. He began to remember the words and what they meant. He was fascinated with the knowledge that he was gaining. He finished the A’s and went on to the B’s. Over a period of time he finished copying out the whole dictionary. Malcolm regarded the dictionary as a miniature encyclopedia. He learned about people and animals, about places and history, philosophy and science.

As his word base broadened, he found that he could pick up a book “and now begin to understand what the book was saying”. He says that “from then until I left that prison, in every free moment I had, if I was not reading in the library, I was reading in my bunk. You couldn’t have gotten me out of a book with a wedge”.

He preferred to read in his cell but one of the problems he had was that at 10 o’clock each night when ‘lights out’ was called he found that it always seemed to coincide with him in the middle of something engrossing. Fortunately, there was a light on the landing outside his particular cell and once his eyes got accustomed to the glow, he was able to sit on the floor by the cell door and continue his reading. He found that the guards would come around once every hour so that when he heard their footsteps approaching, he would rush back to his bunk until they had gone past and pretend to be asleep. As soon as they had gone, he would be back by the door reading. This would continue until three or four every morning. He says that “three or four hours of sleep a night was enough for me. Often in the years in the streets I had slept less than that”.

Malcolm read and read and read. He devoured books on history and was astounded at the knowledge he obtained about the history of black civilizations throughout the world. He read books by Gandhi on the struggle in India, he read about African colonization and China’s Opium Wars. He found within the library’s collection some bound pamphlets of the Abolitionist Anti-Slavery Society and was able to read for himself descriptions of atrocities committed against the slaves and of the degradations suffered by his forbears. “I never will forget how shocked I was when I began reading about slavery’s total horror … Book after book showed me how the white man had brought upon the world’s black, brown, red and yellow peoples every variety of the sufferings of exploitation”. His reading was not limited to history, however. He read about genetics and philosophy. He read about religion.

He relates that “ten guards and the warden couldn’t have torn me out of those books … I have often reflected upon the new vistas that reading opened to me. I knew right there in prison that reading had changed forever the course of my life”.

Malcolm went on to become a major figure in the fight against racism in the United States. He became a dynamic spokesman for the Black Muslims. He was feared by many, he was respected by many.

He never stopped wanting to learn. Just before his death in 1965, he maintained that one of the things he most regretted in his life was his lack of an academic education. He stated that he would be quite willing to go back to school and continue where he had left off and go on to take a degree. “I would just like to study. I mean ranging study, because I have a wide-open mind. I’m interested in almost any subject you can mention”.

When he left the Black Muslims and formed his own organization, one of the roles he performed was that of a teacher. He ran a regular class for young people where he told them “We have got to get over the brainwashing we had … get out of your mind what the man put in it … Read everything. You never know where you’re going to get an idea. We have to learn how to think …”

Bibliography

Bloom, H. (1996) Alex Haley & Malcolm X’s the Autobiography of Malcolm X. Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House.

DeCaro, L. (1998) Malcolm and the Cross: The Nation of Islam, Malcolm X, and Christianity. New York: New York University Press.

Haley, A. (ed.) (1965) The Autobiography of Malcolm X . New York: Grove Press, Inc. (Also available as a Penguin paperback 1970).

Perry, B. (1991) Malcolm: The Life of the Man Who Changed Black America. Barrytown, NY: Station Hill Press.

BrotherMalcolm.net – comprehensive listing of links etc.

Malcolm-X.org – various resources

Acknowledgement : Picture: Malcolm X – released into the public domain by its author, U.S. News & World Report (Library of Congress). Sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

How to cite this article : Burke, B. (2004). ‘Malcolm X on education’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education . [ www.infed.org/thinkers/malcolm.htm Retrieved: insert date ].

© Barry Burke 2004

Last Updated on January 28, 2013 by infed.org

May 19, 1925 to February 21, 1965

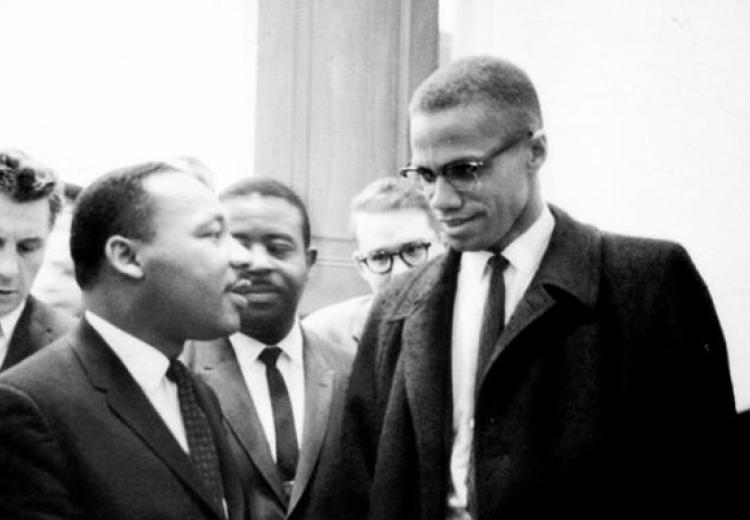

As the nation’s most visible proponent of Black Nationalism , Malcolm X’s challenge to the multiracial, nonviolent approach of Martin Luther King, Jr., helped set the tone for the ideological and tactical conflicts that took place within the black freedom struggle of the 1960s. Given Malcolm X’s abrasive criticism of King and his advocacy of racial separatism, it is not surprising that King rejected the occasional overtures from one of his fiercest critics. However, after Malcolm’s assassination in 1965, King wrote to his widow, Betty Shabazz: “While we did not always see eye to eye on methods to solve the race problem, I always had a deep affection for Malcolm and felt that he had the great ability to put his finger on the existence and root of the problem” (King, 26 February 1965).

Malcolm Little was born to Louise and Earl Little in Omaha, Nebraska, on 19 May 1925. His father died when he was six years old—the victim, he believed, of a white racist group. Following his father’s death, Malcolm recalled, “Some kind of psychological deterioration hit our family circle and began to eat away our pride” (Malcolm X, Autobiography , 14). By the end of the 1930s Malcolm’s mother had been institutionalized, and he became a ward of the court to be raised by white guardians in various reform schools and foster homes.

Malcolm joined the Nation of Islam (NOI) while serving a prison term in Massachusetts on burglary charges. Shortly after his release in 1952, he moved to Chicago and became a minister under Elijah Muhammad, abandoning his “slave name,” and becoming Malcolm X (Malcolm X, “We Are Rising”). By the late 1950s, Malcolm had become the NOI’s leading spokesman.

Although Malcolm rejected King’s message of nonviolence , he respected King as a “fellow-leader of our people,” sending King NOI articles as early as 1957 and inviting him to participate in mass meetings throughout the early 1960s ( Papers 5:491 ). Although Malcolm was particularly interested that King hear Elijah Muhammad’s message, he also sought to create an open forum for black leaders to explore solutions to the “race problem” (Malcolm X, 31 July 1963). King never accepted Malcolm’s invitations, however, leaving communication with him to his secretary, Maude Ballou .

Despite his repeated overtures to King, Malcolm did not refrain from criticizing him publicly. “The only revolution in which the goal is loving your enemy,” Malcolm told an audience in 1963, “is the Negro revolution … That’s no revolution” (Malcolm X, “Message to the Grassroots,” 9).

In the spring of 1964, Malcolm broke away from the NOI and made a pilgrimage to Mecca. When he returned he began following a course that paralleled King’s—combining religious leadership and political action. Although King told reporters that Malcolm’s separation from Elijah Muhammad “holds no particular significance to the present civil rights efforts,” he argued that if “tangible gains are not made soon all across the country, we must honestly face the prospect that some Negroes might be tempted to accept some oblique path [such] as that Malcolm X proposes” (King, 16 March 1964).

Ten days later, during the Senate debate on the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , King and Malcolm met for the first and only time. After holding a press conference in the Capitol on the proceedings, King encountered Malcolm in the hallway. As King recalled in a 3 April letter, “At the end of the conference, he came and spoke to me, and I readily shook his hand.” King defended shaking the hand of an adversary by saying that “my position is that of kindness and reconciliation” (King, 3 April 1965).

Malcolm’s primary concern during the remainder of 1964 was to establish ties with the black activists he saw as more militant than King. He met with a number of workers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), including SNCC chairman John Lewis and Mississippi organizer Fannie Lou Hamer . Malcolm saw his newly created Organization of African American Unity (OAAU) as a potential source of ideological guidance for the more militant veterans of the southern civil rights movement. At the same time, he looked to the southern struggle for inspiration in his effort to revitalize the Black Nationalist movement.

In January 1965, he revealed in an interview that the OAAU would “support fully and without compromise any action by any group that is designed to get meaningful immediate results” (Malcolm X, Two Speeches , 31). Malcolm urged civil rights groups to unite, telling a gathering at a symposium sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality : “We want freedom now, but we’re not going to get it saying ‘We Shall Overcome.’ We've got to fight to overcome” (Malcolm X, Malcolm X Speaks , 38).

In early 1965, while King was jailed in Selma, Alabama, Malcolm traveled to Selma, where he had a private meeting with Coretta Scott King . “I didn’t come to Selma to make his job difficult,” he assured Coretta. “I really did come thinking that I could make it easier. If the white people realize what the alternative is, perhaps they will be more willing to hear Dr. King” (Scott King, 256).

On 21 February 1965, just a few weeks after his visit to Selma, Malcolm X was assassinated. King called his murder a “great tragedy” and expressed his regret that it “occurred at a time when Malcolm X was … moving toward a greater understanding of the nonviolent movement” (King, 24 February 1965). He asserted that Malcolm’s murder deprived “the world of a potentially great leader” (King, “The Nightmare of Violence”). Malcolm’s death signaled the beginning of bitter battles involving proponents of the ideological alternatives the two men represented.

Maude L. Ballou to Malcolm X, 1 February 1957, in Papers 4:117 .

Goldman, Death and Life of Malcolm X , 1973.

King, “The Nightmare of Violence,” New York Amsterdam News , 13 March 1965.

King, Press conference on Malcolm X’s assassination, 24 February 1965, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, Statement on Malcolm X’s break with Elijah Muhammad, 16 March 1964, MCMLK-RWWL .

King to Abram Eisenman, 3 April 1964, MLKJP-GAMK .

King to Shabazz, 26 February 1965, MCMLK-RWWL .

(Scott) King, My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr. , 1969.

Malcolm X, Interview by Harry Ring over Station WBAI-FM in New York, in Two Speeches by Malcolm X , 1965.

Malcolm X, “Message to the Grassroots,” in Malcolm X Speaks , ed. George Breitman, 1965.

Malcolm X, “We Are Rising From the Dead Since We Heard Messenger Muhammad Speak,” Pittsburgh Courier , 15 December 1956.

Malcolm X to King, 21 July 1960, in Papers 5:491 .

Malcolm X to King, 31 July 1963,

Malcolm X with Haley, Autobiography of Malcolm X , 1965.

Historical Material

Maude L. Ballou to Malcolm X

From Malcolm X

Malcolm X’s View on Education

This essay about Malcolm X explores his influential role in civil rights activism and his unique perspective on education as a means of empowerment and liberation. It discusses his challenging early life, his transformative self-education in prison, and his advocacy for a revolutionary approach to education that emphasized self-determination for African Americans. The essay highlights his impact on societal change and the enduring relevance of his ideas on education and freedom.

How it works

In the vibrant landscape of civil rights activism in mid-20th century America, Malcolm X stood out as a pivotal figure, casting a long shadow over the domain of racial inequality. His view on education, complex and evolving, mirrored the ups and downs of his own life, moving from disenfranchisement to awareness. Malcolm X’s concept of education went beyond the traditional boundaries of schools, textbooks, and curricula; it was a powerful call to reclaim autonomy, dignity, and self-worth amid systemic discrimination.

Malcolm X’s early life was marked by severe challenges and exclusion. Born in a society where skin color dictated value, he experienced firsthand the ugly realities of racism and segregation that infiltrated all aspects of American life. Lacking access to quality education and trapped in a cycle of poverty and despair, Malcolm X’s formative years highlighted the deep-rooted inequalities in the country.

However, it was within the walls of a prison cell that Malcolm X’s journey of self-education truly commenced. Isolated from the world, he plunged into a universe of thought, consuming books with an insatiable thirst for knowledge. Without the usual resources of formal education, Malcolm X undertook a self-directed quest for enlightenment, exploring literature, philosophy, and history for insights that would form his ideological framework.

For Malcolm X, education was more than just a tool for acquiring skills or qualifications; it was a route to freedom, a key element in the fight against oppression. In his autobiography, he described how his time in prison became a period of profound personal change, where ignorance was replaced by knowledge. “I don’t think anybody ever got more out of going to prison than I did,” he stated, recognizing the crucial impact of education on his path to redemption.

At the heart of Malcolm X’s educational philosophy was the principle of self-determination. He opposed the idea that African Americans should merely accept the limited educational opportunities provided by a predominantly white society. Instead, he advocated for a transformative approach to education, imagining schools that would enable Black students to reconnect with their heritage, challenge established norms, and determine their own futures.

Additionally, Malcolm X saw education as a driving force for collective action and societal transformation. He believed that true freedom could only come from the unity and solidarity of marginalized communities, with education acting as a unifying force. Through his public addresses and writings, he urged African Americans to disregard the divisive narratives set by a prejudiced society and unite towards the common objective of liberty.

Though Malcolm X’s stance on education, particularly his support for Black separatism and critique of the integration-focused civil rights movement, sparked significant debate. Nevertheless, he remained committed to disrupting the existing order and advocating for the empowerment of Black individuals.

Reflecting on Malcolm X’s legacy today, his perspectives and words still resonate, offering a powerful vision of education as a tool for liberation and empowerment. By celebrating his contributions, we recommit ourselves to the values of knowledge, justice, and freedom for all.

Cite this page

Malcolm X's View On Education. (2024, Apr 29). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/malcolm-xs-view-on-education/

"Malcolm X's View On Education." PapersOwl.com , 29 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/malcolm-xs-view-on-education/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Malcolm X's View On Education . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/malcolm-xs-view-on-education/ [Accessed: 19 May. 2024]

"Malcolm X's View On Education." PapersOwl.com, Apr 29, 2024. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/malcolm-xs-view-on-education/

"Malcolm X's View On Education," PapersOwl.com , 29-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/malcolm-xs-view-on-education/. [Accessed: 19-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Malcolm X's View On Education . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/malcolm-xs-view-on-education/ [Accessed: 19-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Civil rights activist Malcolm X was a prominent leader in the Nation of Islam. Until his 1965 assassination, he vigorously supported Black nationalism.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Quick Facts

Early life and family, time in prison, nation of islam, malcolm x and martin luther king jr., becoming a mainstream sunni muslim, assassination, wife and children, "the autobiography of malcolm x", who was malcolm x.

Malcolm X was a minister, civil rights activist , and prominent Black nationalist leader who served as a spokesman for the Nation of Islam during the 1950s and 1960s. Due largely to his efforts, the Nation of Islam grew from a mere 400 members at the time he was released from prison in 1952 to 40,000 members by 1960. A naturally gifted orator, Malcolm X exhorted Black people to cast off the shackles of racism “by any means necessary,” including violence. The fiery civil rights leader broke with the Nation of Islam shortly before his assassination in 1965 at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan, where he had been preparing to deliver a speech. He was 39 years old.

FULL NAME: Malcolm X (nee Malcolm Little) BORN: May 19, 1925 DIED: February 21, 1965 BIRTHPLACE: Omaha, Nebraska SPOUSE: Betty Shabazz (1958-1965) CHILDREN: Attilah, Quiblah, Lamumbah, Ilyasah, Malaak, and Malikah ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Taurus

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska. He was the fourth of eight children born to Louise, a homemaker, and Earl Little, a preacher who was also an active member of the local chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and avid supporter of Black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey .

Due to Earl Little’s civil rights activism, the family was subjected to frequent harassment from white supremacist groups including the Ku Klux Klan and one of its splinter factions, the Black Legion. In fact, Malcolm Little had his first encounter with racism before he was even born. “When my mother was pregnant with me, she told me later, ‘a party of hooded Ku Klux Klan riders galloped up to our home,’” Malcolm later remembered. “Brandishing their shotguns and rifles, they shouted for my father to come out.”

The harassment continued when Malcolm was 4 years old, and local Klan members smashed all of the family’s windows. To protect his family, Earl Little moved them from Omaha to Milwaukee in 1926 and then to Lansing, Michigan, in 1928.

However, the racism the family encountered in Lansing proved even greater than in Omaha. Shortly after the Littles moved in, a racist mob set their house on fire in 1929, and the town’s all-white emergency responders refused to do anything. “The white police and firemen came and stood around watching as the house burned to the ground,” Malcolm later remembered. Earl moved the family to East Lansing where he built a new home.

Two years later, in 1931, Earl’s dead body was discovered lying across the municipal streetcar tracks. Although the family believed Earl was murdered by white supremacists from whom he had received frequent death threats, the police officially ruled his death a streetcar accident, thereby voiding the large life insurance policy he had purchased in order to provide for his family in the event of his death.

Louise never recovered from the shock and grief over her husband’s death. In 1937, she was committed to a mental institution where she remained for the next 26 years. Malcolm and his siblings were separated and placed in foster homes.

In 1938, Malcolm was kicked out of West Junior High School and sent to a juvenile detention home in Mason, Michigan. The white couple who ran the home treated him well, but he wrote in his autobiography that he was treated more like a “pink poodle” or a “pet canary” than a human being.

He attended Mason High School where he was one of only a few Black students. He excelled academically and was well-liked by his classmates, who elected him class president.

A turning point in Malcolm’s childhood came in 1939 when his English teacher asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, and he answered that he wanted to be a lawyer. His teacher responded, “One of life’s first needs is for us to be realistic... you need to think of something you can be... why don’t you plan on carpentry?” Having been told in no uncertain terms that there was no point in a Black child pursuing education, Malcolm dropped out of school the following year, at the age of 15.

After quitting school, Malcolm moved to Boston to live with his older half-sister, Ella, about whom he later recalled: “She was the first really proud Black woman I had ever seen in my life. She was plainly proud of her very dark skin. This was unheard of among Negroes in those days.”

Ella landed Malcolm a job shining shoes at the Roseland Ballroom. However, out on his own on the streets of Boston, he became acquainted with the city’s criminal underground and soon turned to selling drugs.

He got another job as kitchen help on the Yankee Clipper train between New York and Boston and fell further into a life of drugs and crime. Sporting flamboyant pinstriped zoot suits, he frequented nightclubs and dance halls and turned more fully to crime to finance his lavish lifestyle.

In 1946, Malcolm was arrested on charges of larceny and sentenced to 10 years in prison. To pass the time during his incarceration, he read constantly, devouring books from the prison library in an attempt make up for the years of education he had missed by dropping out of high school.

Also while in prison, Malcolm was visited by several siblings who had joined the Nation of Islam, a small sect of Black Muslims who embraced the ideology of Black nationalism—the idea that in order to secure freedom, justice and equality, Black Americans needed to establish their own state entirely separate from white Americans.

He changed his name to Malcolm X and converted to the Nation of Islam before his release from prison in 1952 after six and a half years.

Now a free man, Malcolm X traveled to Detroit, where he worked with the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad , to expand the movement’s following among Black Americans nationwide.

Malcolm X became the minister of Temple No. 7 in Harlem and Temple No. 11 in Boston, while also founding new temples in Hartford and Philadelphia. In 1960, he established a national newspaper called Muhammad Speaks in order to further promote the message of the Nation of Islam.

Articulate, passionate, and an inspirational orator, Malcolm X exhorted Black people to cast off the shackles of racism “by any means necessary,” including violence. “You don’t have a peaceful revolution. You don’t have a turn-the-cheek revolution,” he said. “There’s no such thing as a nonviolent revolution.”

His militant proposals—a violent revolution to establish an independent Black nation—won Malcolm X large numbers of followers as well as many fierce critics. Due primarily to the efforts of Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam grew from a mere 400 members at the time he was released from prison in 1952, to 40,000 members by 1960.

By the early 1960s, Malcolm X had emerged as a leading voice of a radicalized wing of the Civil Rights Movement, presenting a dramatic alternative to Martin Luther King Jr. ’s vision of a racially-integrated society achieved by peaceful means. King was critical of Malcolm’s methods but avoided directly calling out his more radical counterpart. Although very aware of each other and working to achieve the same goal, the two leaders met only once—and very briefly—on Capitol Hill when the U.S. Senate held a hearing about an anti-discrimination bill.

A rupture with Elijah Muhammad proved much more traumatic. In 1963, Malcolm X became deeply disillusioned when he learned that his hero and mentor had violated many of his own teachings, most flagrantly by carrying on many extramarital affairs. Muhammad had, in fact, fathered several children out of wedlock.

Malcolm’s feelings of betrayal, combined with Muhammad’s anger over Malcolm’s insensitive comments regarding the assassination of John F. Kennedy , led Malcolm X to leave the Nation of Islam in 1964.

That same year, Malcolm X embarked on an extended trip through North Africa and the Middle East. The journey proved to be both a political and spiritual turning point in his life. He learned to place America’s Civil Rights Movement within the context of a global anti-colonial struggle, embracing socialism and pan-Africanism.

Malcolm X also made the Hajj, the traditional Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, during which he converted to traditional Islam and again changed his name, this time to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

After his epiphany at Mecca, Malcolm X returned to the United States more optimistic about the prospects for a peaceful resolution to America’s race problems. “The true brotherhood I had seen had influenced me to recognize that anger can blind human vision,” he said. “America is the first country... that can actually have a bloodless revolution.”

Just as Malcolm X appeared to be embarking on an ideological transformation with the potential to dramatically alter the course of the Civil Rights Movement, he was assassinated .

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X took the stage for a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan. He had just begun addressing the room when multiple men rushed the stage and began firing guns. Struck numerous times at close range, Malcolm X was declared dead after arriving at a nearby hospital. He was 39.

Three members of the Nation of Islam were tried and sentenced to life in prison for murdering the activist. In 2021, two of the men—Muhammad Aziz and Khalil Islam—were exonerated for Malcolm’s murder after spending decades behind bars. Both maintained their innocence but were still convicted in March 1966, alongside Mujahid Abdul Halim, who did confess to the murder. Aziz and Islam were released from prison in the mid-1980s, and Islam died in 2009. After the exoneration, they were awarded $36 million for their wrongful convictions.

In February 2023, Malcolm X’s family announced a wrongful death lawsuit against the New York Police Department, the FBI, the CIA, and other government entities in relation to the activist’s death. They claim the agencies concealed evidence and conspired to assassinate Malcolm X.

Malcolm X married Betty Shabazz in 1958. The couple had six daughters: Attilah, Quiblah, Lamumbah, Ilyasah, Malaak, and Malikah. Twins Malaak and Malikah were born after Malcolm died in 1965.

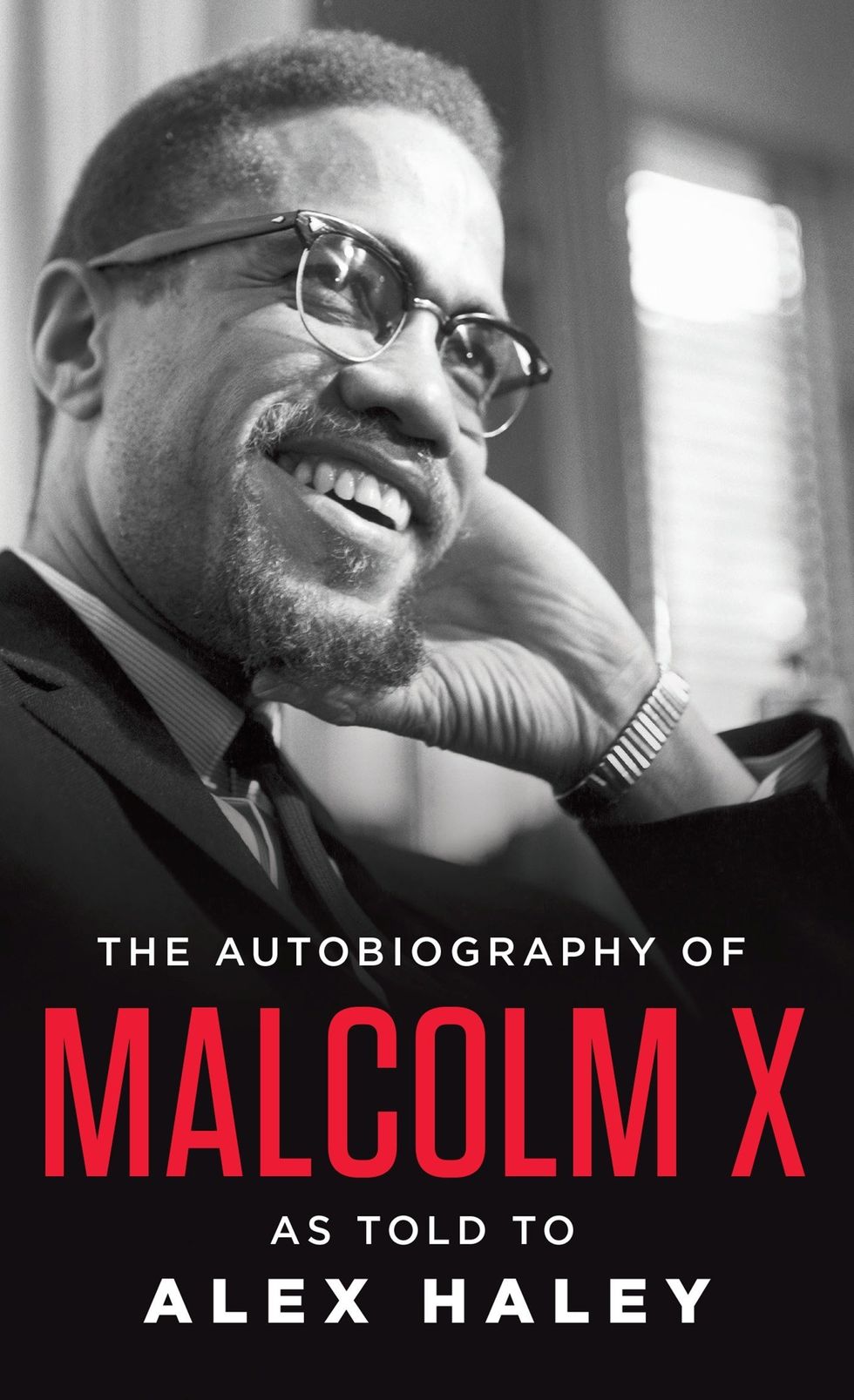

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

In the early 1960s, Malcolm X began working with acclaimed author Alex Haley on an autobiography. The book details Malcolm X’s life experiences and his evolving views on racial pride, Black nationalism, and pan-Africanism.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X was published in 1965 after his assassination to near-universal praise. The New York Times called it a “brilliant, painful, important book,” and Time magazine listed it as one of the 10 most influential nonfiction books of the 20 th century.

Malcolm X has been the subject of numerous movies, stage plays, and other works and has been portrayed by actors like James Earl Jones , Morgan Freeman , and Mario Van Peebles.

In 1992, Spike Lee directed Denzel Washington in the title role of his movie Malcolm X . Both the film and Washington’s portrayal of Malcolm X received wide acclaim and were nominated for several awards, including two Academy Awards.

In the immediate aftermath of Malcolm X’s death, commentators largely ignored his recent spiritual and political transformation and criticized him as a violent rabble-rouser. But especially after the publication of The Autobiography of Malcolm X , he began to be remembered for underscoring the value of a truly free populace by demonstrating the great lengths to which human beings will go to secure their freedom.

“Power in defense of freedom is greater than power in behalf of tyranny and oppression,” he said. “Because power, real power, comes from our conviction which produces action, uncompromising action.”

- Power in defense of freedom is greater than power in behalf of tyranny and oppression because power, real power, comes from our conviction which produces action, uncompromising action.

- Education is the passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today.

- You don’t have a peaceful revolution. You don’t have a turn-the-cheek revolution. There’s no such thing as a nonviolent revolution.

- If you are not willing to pay the price for freedom, you don’t deserve freedom.

- We want freedom now, but we’re not going to get it saying “We Shall Overcome.” We’ve got to fight to overcome.

- I believe that it is a crime for anyone to teach a person who is being brutalized to continue to accept that brutality without doing something to defend himself.

- We are non-violent only with non-violent people—I’m non-violent as long as somebody else is non-violent—as soon as they get violent, they nullify my non-violence.

- Revolution is like a forest fire. It burns everything in its path. The people who are involved in a revolution don’t become a part of the system—they destroy the system, they change the system.

- If a man puts his arms around me voluntarily, that’s brotherhood, but if you hold a gun on him and make him embrace me and pretend to be friendly or brotherly toward me, then that’s not brotherhood, that’s hypocrisy.

- You get freedom by letting your enemy know that you’ll do anything to get your freedom; then you’ll get it. It’s the only way you’ll get it.

- My father didn’t know his last name. My father got his last name from his grandfather, and his grandfather got it from his grandfather who got it from the slavemaster.

- To have once been a criminal is no disgrace. To remain a criminal is the disgrace. I formerly was a criminal. I formerly was in prison. I’m not ashamed of that.

- It’s going to be the ballot or the bullet.

- America is the first country... that can actually have a bloodless revolution.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Black History

Jesse Owens

Alice Coachman

Wilma Rudolph

Tiger Woods

Deb Haaland

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Ava DuVernay

Octavia Spencer

Inventor Garrett Morgan’s Lifesaving 1916 Rescue

Get to Know 5 History-Making Black Country Singers

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Malcolm X: A Radical Vision for Civil Rights

Martin Luther King and Malcolm X waiting for press conference, March 26, 1964.

Wikimedia Commons

When most people think of the civil rights movement, they think of Martin Luther King, Jr., whose "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, and his acceptance of the Peace Prize the following year, secured his place as the voice of non-violent, mass protest in the 1960s.

Yet the movement achieved its greatest results—the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act—due to the competing and sometimes radical strategies and agendas of diverse individuals such as Malcolm X, whose birthday is celebrated on May 19. As one of the most powerful, controversial, and enigmatic figures of the movement he occupies a necessary place in social studies/history curricula.

Malcolm X’s Black Separatism

Malcolm X’s embrace of black separatism shaped the debate over how to achieve freedom and equality in a nation that had long denied a portion of the American citizenry the full protection of their rights. It also laid the groundwork for the Black Power movement of the late sixties.

Malcolm X believed that blacks were god's chosen people. As a minister of the Nation of Islam, he preached fiery sermons on separation from whites, whom he believed were destined for divine punishment because of their longstanding oppression of blacks.

Whites had proven themselves long on professing and short on practicing their ideals of equality and freedom, and Malcolm X thought only a separate nation for blacks could provide the basis for their self-improvement and advancement as a people.

In this interview at the University of California—Berkeley in 1963, Malcolm X addresses media and violence, being a Muslim in America, desegregation, and other issues pertinent to the successes and short-comings of the civil rights movement.

Malcolm X and the Common Core

The Common Core emphasizes that students’ reading, writing, and speaking be grounded in textual evidence and the lesson Black Separatism or the Beloved Community? Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. , which contrasts Malcolm X and Martin Luther King’s aims and means of achieving progress for black American progress in the 1960s, provides a wealth of supplementary historical nonfiction texts for such analysis.

This lesson helps teachers and students achieve a range of Common Core standards, including:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.2 —Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.9 —Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.11-12.4 —Present information, findings, and supporting evidence, conveying a clear and distinct perspective, such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning, alternative or opposing perspectives are addressed, and the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to purpose, audience, and a range of formal and informal tasks.

The background to the teacher section, written by a scholar of African American political thought, will benefit both novice teachers and those who seek to deepen their understanding of this seminal figure.

In the activity section, students gain an understanding of Malcolm X’s ideas and an appreciation for his rhetorical powers by diving into compelling and complex primary source material, including an exclusive interview with the journalist Louis Lomax (who first brought Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam to the attention of white people) and by reading and listening to a recording of Malcolm X’s “Message to the Grassroots.”

The assessment activity asks students to evaluate both visions for a new and “more perfect” America. In this way they will gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of civil rights movement writ large.

In the extending the lesson section, the evolution of Malcolm X’s views are traced and considered.

After he left the Nation of Islam in March 1964, Malcolm felt free to offer political solutions to the problems that afflicted black Americans. He advised black Americans to (1) engage in smarter political voting and organization (for example, no longer voting for black leaders he viewed as shills for white interests); and (2) fight for civil rights at the international level .

One of Malcolm X’s last speeches, "The Ballot or the Bullet," is crucial, and a close reading of it will help students understand how his thinking about America and black progress was evolving.

More Common Core Connections

Teachers may also wish to use a radio documentary accessible through the NEH-supported WNYC archive that includes a rare interview with Malcolm X and goes on to explore his legacy and relationship with Islam through interviews with friends, associates, and excerpts from his speeches.

Last and not least, the NEH-supported American Icons podcast on The Autobiography of Malcolm X surveys The Autobiography ’s appeal and includes riveting passages read by the actor Dion Graham. Teachers can listen to both podcasts as they begin to plan lessons around the text, or they may choose to listen with students in order to introduce them to the debates the text continues to spark around race, rights, and social justice. This activity would help students meet another of the ELA Standards.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.11-12.5 —Make strategic use of digital media (e.g., textual, graphical, audio, visual, and interactive elements) in presentations to enhance understanding of findings, reasoning, and evidence and to add interest.

Additional Resources

- American Icons podcast on The Autobiography of Malcolm X

- WNYC Archive: Rare Interviews and Audio with Malcolm X

Related on EDSITEment

The music of african american history, the green book: african american experiences of travel and place in the u.s., grassroots perspectives on the civil rights movement: focus on women, lesson 2: black separatism or the beloved community malcolm x and martin luther king, jr., the works of langston hughes.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

Ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X is the story Malcolm tells of his experiences and of his own growth. Alternatively, it is the story of his education. That education is not a standard one, with typical schooling. It is rather an education in racism, on the streets, and out in the world – but Malcolm is consistent in his efforts to learn from his experiences and to make an education, however informal, for himself.

As a child, Malcolm does very well in school, and he ranks among the top three students in his class. His dreams of becoming a lawyer, however, are blocked by his white teacher, Mr. Ostrowski , who tells him to set his sights more reasonably and pursue a career in carpentry. This marks one of the first times that Malcolm is acutely aware of being discriminated against because of his race, and he quickly drops out of school. More than teaching him subject knowledge, Malcolm’s official school career makes him aware of racism, of how official society represented by public schools both oppresses black people and justifies that oppression through its view of black people as being inferior – a viewpoint that at least for a time Malcolm internalizes.

Malcolm then turns to a life on the streets, where he receives a very different kind of education, as he learns to “hustle” and to make extra money wherever he can. As another hustler Freddie tells him, "The main thing you got to remember is that everything in the world is a hustle.” This advice becomes a guiding principle of Malcolm’s throughout his hustling career and beyond, for both good and ill. On the one hand, Malcolm explains how it opens up his mind to see how so many relationships and moments which seem innocent actually involve some form of “hustle,” or some hidden play for money, influence, or power. However, Malcolm also explains how it presses him into a “jungle mentality” in which he can only think in terms of survival. Plus, hustling (in this case, burglary) eventually gets Malcolm sent to prison for seven years.

In prison Malcolm’s education shifts, especially after he gets transferred to the Norfolk Prison Colony, a progressive institution with regular lectures, debates, and a large library. With both time and resources that have previously been denied to him, Malcolm rediscovers his love of books and learning, becoming particularly interested in the history of Africa, the American slave trade, and religion. He stays so busy studying that “months passed without my even thinking about being imprisoned. In fact, up to then, I never had been so truly free in my life.” This education is freeing not just in that it helps Malcolm pass the time or do something he enjoys, but that it gives him an understanding of things that had previously been hidden from him. It’s freeing because it lets him see the lie in the racism forced upon him by his official schooling, and his own dignity as a black man, and it motivates him to join the Nation of Islam.

After breaking with the Nation of Islam, Malcolm characterizes that time of his life within the group as being “twelve years of never thinking.” But the Hajj to Mecca, where he must learn the beliefs and customs of orthodox Muslims, gives him a final education. The Hajj exposes Malcolm both to a wider world and his own ignorance. For instance, he finds that he does not even know the proper Islamic prayer postures, and his body aches under the strain of practicing them. This education is extremely humbling, especially for a man who has been leading a growing religious movement for years. As Malcolm puts it: “Imagine, being a Muslim minister, a leader in Elijah Muhammad's Nation of Islam, and not knowing the prayer ritual.” By humbling him from the position of minister to just another man simply learning to serve God, this education contributes towards his more tempered views on the goals of social justice.

Malcolm never loses his reverence for education. In fact, as he reflects in the Autobiography shortly before his assassination, he says his only regret is that he never finished his schooling to become a lawyer. He understands that education has been an empowering force in his life, but the one time he was denied further access to it he was forced to learn a different, more destructive way to survive.

Education ThemeTracker

Education Quotes in The Autobiography of Malcolm X

I looked like Li'l Abner. Mason, Michigan, was written all over me. My kinky, reddish hair was cut hick style, and I didn't even use grease in it. My green suit's coat sleeves stopped above my wrists, the pants legs showed three inches of socks. Just a shade lighter green than the suit was my narrow-collared, three-quarter length Lansing department store topcoat. My appearance was too much for even Ella. But she told me later she had seen countrified members of the Little family come up from Georgia in even worse shape than I was.

"The main thing you got to remember is that everything in the world is a hustle. So long, Red.”

Shorty would take me to groovy, frantic scenes in different chicks' and cats' pads, where with the lights and juke down mellow, everybody blew gage and juiced back and jumped. I met chicks who were fine as May wine, and cats who were hip to all happenings. That paragraph is deliberate, of course; it's just to display a bit more of the slang that was used by everyone I respected as "hip" in those days. And in no time at all, I was talking the slang like a lifelong hipster.

We were in that world of Negroes who are both servants and psychologists, aware that white people are so obsessed with their own importance that they will pay liberally, even dearly, for the impression of being catered to and entertained.

There I was back in Harlem's streets among all the rest of the hustlers. I couldn't sell reefers; the dope squad detectives were too familiar with me. I was a true hustler—uneducated, unskilled at anything honorable, and I considered myself nervy and cunning enough to live by my wits, exploiting any prey that presented itself. I would risk just about anything.

I was going through the hardest thing, also the greatest thing, for any human being to do; to accept that which is already within you, and around you.

Let me tell you something: from then until I left that prison, in every free moment I had, if I was not reading in the library, I was reading on my bunk. You couldn't have gotten me out of books with a wedge. Between Mr. Muhammad's teachings, my correspondence, my visitors—usually Ella and Reginald—and my reading of books, months passed without my even thinking about being imprisoned. In fact, up to then, I never had been so truly free in my life.

“Today's Uncle Tom doesn't wear a handkerchief on his head. This modern, twentieth-century Uncle Thomas now often wears a top hat. He's usually well-dressed and well-educated. He's often the personification of culture and refinement. The twentieth-century Uncle Thomas sometimes speaks with a Yale or Harvard accent. Sometimes he is known as Professor, Doctor, Judge, and Reverend, even Right Reverend Doctor. This twentieth-century Uncle Thomas is a professional Negro . . . by that I mean his profession is being a Negro for the white man.”

And that was how, after twelve years of never thinking for as much as five minutes about myself, I became able finally to muster the nerve, and the strength, to start facing the facts, to think for myself.

I told him, "What you are telling me is that it isn't the American white man who is a racist, but it's the American political, economic, and social atmosphere that automatically nourishes a racist psychology in the white man." He agreed.

He talked about the pressures on him everywhere he turned, and about the frustrations, among them that no one wanted to accept anything relating to him except "my old 'hate' and 'violence' image." He said "the so-called moderate" civil rights organizations avoided him as "too militant" and the "so-called militants" avoided him as "too moderate." “They won't let me tum the corner!" he once exclaimed, “I'm caught in a trap!"

The Ideological and Spiritual Transformation of Malcolm X

- Open access

- Published: 18 July 2020

- Volume 24 , pages 417–433, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Trevin Jones 1

43k Accesses

4 Citations

68 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper explores the nexus between incarceration, spirituality, and self-discovery through the literary lens of The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Nineteenth Century: Medicine, Spiritualism and Christianity

Magic, Madness, and the Ruses of the Trickster: Healing Rituals and Alternative Spiritualities in Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day, Erna Brodber’s Jane and Louisa Will Soon Come Home, and Nalo Hopkinson’s Brown Girl in the Ring

Writing in the Face of Social Death: Malcolm X’s Autobiography Representing Varied Sustaining Objects/Processes

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Evolving Ideology of Malcolm X

For many African American males inside and outside of prison, Malcolm X embodies the true meaning of manhood, spirituality, and leadership. He personifies the rebel and the reformed, the unsympathetic and passionate, and the incorrigible and scholarly. Malcolm X’s life was one of complexity due to many changes, internal and external, that impacted his evolution as a man as well as his broad influence on African American culture. Some scholars argue that Malcom X inspired a generation of African American men while other misguided souls believe his lasting legacy is one of racial polarization. Whether people revere Malcolm as someone who wanted to uplift his race or suspect him to be a figure who widened the racial divide through his unrestrained critique of the American social order, it is safe to say that even in death, his legacy is still evolving. His story fascinates young readers and continues to inspire prison inmates who see Malcolm’s life as a reflection of their own. This article examines Malcolm X’s spiritual evolution as a former prisoner, Nation of Islam minister, and human rights activist. This work does not explore The Autobiography of Malcolm X from a sentimental gaze but as an avenue to understand many of the deep-seated issues that continue to plague our nation, such as race, incarceration, manhood, and the possibility of conversion behind bars. In addition, I argue that Malcolm X’s spiritual journey and search for ideological soundness remained in a state of flux even at the time of his assassination.

Moreover, people continue to be intrigued by the mystique of Malcolm X, especially because his life was snuffed out before his potential could be actualized. As a result, scholars, spectators, and skeptics are still constructing Malcolm’s life story from his interviews, speeches, and time spent with author Alex Haley. One can argue that while Haley may have written a first account of Malcolm X’s oral history, there still remains an element of mythology to behind Haley’s account, as Malcolm died before his narrative was finished. Shirley K. Rose suggests, “All autobiographical writing contains two distinct literary myths: literacy as a means for achieving individual autonomy and literacy as means of social participation” (Rose 1987 , 3). These literary myths are evident in Malcolm X’s autobiography because Alex Haley superimposes his language onto Malcolm’s words and manipulates how the world at large still views Malcolm’s multifaceted life. One can argue that Haley may have reconstituted some of Malcolm’s narrative accounts to give his story national and global appeal. Nonetheless, Nell Painter argues “Even when the autobiography is not a collaboration, the narrator passes over much in silence and highlights certain themes that become salient . . . [to] what the narrator concludes she or he has become” (Painter 1993 , 433). And at the root of all storytelling is the author’s ability to transcend literary, cultural, and political boundaries. While scholars continue to debate the validity of Haley’s interpretation, Malcolm’s life is still considered a great American story because the narrative intertwines three distinct literary tropes: literacy, the self-made man, and the conversion experience. Nevertheless, the centrality of this research is not an examination of authorship, but an exploration into Malcolm’s life, a controversial American figure, whose life continues to bring attention to incarceration, recidivism, and the probability of transformation in the lives of former convicts.

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, in the middle of the roaring twenties at the height of Jim Crow laws and racial segregation. To combat the onslaught of state-sanctioned terrorism against African Americans, families such as the Littles formed very close bonds with local churches and other religious affiliations. As a young boy, Malcolm witnessed his dad preach fiery sermons in Baptist churches. In addition to preaching, his father also made time to spread the doctrine of Marcus Garvey, the founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, who encouraged African Americans to, among other things, return to Africa. According to Malcolm X, “The teachings of Marcus Garvey stressed becoming independent of the white man” (Alex Haley 1965 , 5). Garvey’s philosophy certainly had a profound effect on young Malcolm, as shown by his later choice of a similar path and doctrine that promoted Black solidarity and racial pride. While a large majority of African Americans believed that a higher being would eventually relieve them from their pain and suffering on earth, Malcolm had a hard time placing his confidence in religion or in a supreme being. He states in his autobiography, “I couldn’t believe in the Christian concept of Jesus as someone divine” (Haley 1965 , 7). Although the text does not state this explicitly, one can infer the possibility that the sudden death of his father and his mother’s mental breakdown thereafter contributed to Malcolm’s distrust of religion.

While his father exited his life in a literal sense, his mother departed both physically and mentally. Malcolm X’s father’s death was considered by many in the African American community an unsolved homicide because his body was found severed on streetcar tracks. Consumed with grief and unable to care for her family, Malcolm X’s mother collapsed emotionally from the anguish and the enormity of having to care for her seven children. She was eventually placed in a mental institution. These two unfathomable losses for Malcolm X are the first in a series of incidents that served as turning points in his life. At such a young age, Malcolm X experienced what most adults dread, yet also understand is imminent. He suffered the literal death of his father at the age of six and the (figurative) passing of his mother at the age of twelve.

The absence of his mother and father left him vulnerable to the lure of the streets and mischievous behavior. As a result, Malcolm X spent time in a foster home and later a reform school. On the way to reform school, a male welfare worker expressed to Malcolm the true meaning of the word reform , which proved to be a foreshadowing to Malcolm’s mission in life. In the autobiography, the welfare worker Mr. Maynard Allen asserts, “The word reform means to change and to become better” (Haley 1965 , 31). Malcolm was about to undergo a series of changes in a new home, school, and town. One incident in particular that served to remind Malcolm of his place or position in society occurred in the eighth grade, when his Caucasian teacher told him to abandon any dreams of becoming a lawyer. His teacher insisted, “A lawyer is no realistic goal for a nigger” (Haley 1965 , 43). These words spoken by Malcolm’s teacher devastated Malcolm and caused him to question the importance of an education. Theologian Ryan LaMothe contends, “No matter how bright or gifted Malcolm was, he now knew that all that was left to him was the lowest sphere of economic and cultural life” (LaMothe 2009 , 531). The world that his white classmates had privy to by virtue of their race was not available to Malcolm. He recalls this pivotal time as an adolescent when learning became no longer a priority. Malcolm states, “It was then that I began to change inside” (Haley 1965 , 44). His desire to learn and to cooperate with those around him was replaced by disappointment that weighed heavy on his mind. This incident caused Malcolm to become even more disillusioned with church and God. Malcolm may have wrestled internally with the following question: How could a loving God allow one race of people to thrive and another race of people to go through life under the cloak of racism and segregation? LaMothe argues, “Malcolm X’s withdrawal from and rebellion against the white world and its concomitant expectations of African American submission included his rejection of Christianity” (LaMothe 2009 , 531). As a result, Malcolm gave his full attention to the world outside of the classroom, where he gained acceptance and access to life on the streets in Harlem.

Without a father or mother to affirm his humanity and identity, Malcolm gained approval from peers who were only interested in acts of deception and corruption. For instance, one lesson he learned early after his arrival in Boston to live with his half-sister Ella was that far too many people lead fraudulent lives, and everything in the world is a hustle (Haley 1965 ). Malcolm thrived in the hustler lifestyle, pedaling narcotics, robbing homes, and engaging in prostitution. Archie Epps claims, “He lived up to his nickname-the tough urbane, devil-like Detroit Red” (Epps 1993 , 64). While Malcolm was far from the attorney, he once dreamed of becoming, he was gaining notoriety fast between the streets of Boston and Harlem in 1943. (the writer needs to introduce to the reader when Malcolm found himself in Harlem). Like most young people in their teens, he lived with the notion of invincibility. His foreboding sense of indestructability heightened every time he escaped being caught or outwitted his peers on the streets. In Malcolm’s autobiography, he recalls this period in his life as a very empty existence. He states, “Through all this time in my life, I really was dead, mentally dead” (Haley 1965 , 145). Malcolm’s eventual arrest in 1946 for burglary awakened him to the severity of his crime and to the irony of finally being out-hustled.

Sitting inside a jail cell brought Malcolm to face to face with the hopelessness and depravity that was far more sinister than the life he knew as a criminal on the streets. He notes, “Behind bars, a man never reforms” (Haley 1965 , 176). Malcolm believed locking men away in cages only intensified their propensity for lawless acts because he too took part in illegal activities for a time while incarcerated. Also, his disdain for white people increased, because in his mind, they were the ones that destroyed his family and life: “The white people who kept calling my mother crazy . . . the white people to the Kalamazoo asylum . . . the white judge and others who had split up the children . . . .” (Haley 1965 , 184). Malcolm’s internal anger also manifested itself in the way he viewed himself as well. For instance, there was a period of his incarceration where fellow inmates referred to Malcolm as Satan, due to his rejection of anything or anyone spiritual in nature. However, his perception of himself and others changed once he submitted his life to Allah.

While Malcolm was not quite twenty-one and facing a lengthy prison sentence, his life shifted once again when he was introduced to Allah and the Nation of Islam (NOI) by his brother Reginald, who visited Malcolm in prison. Through their lengthy conversation about God (Allah) and a subsequent letter from his brother Philibert, after months of soul-searching, Malcolm decided to adopt their Islamic faith. Malcolm’s brothers had aligned their philosophical beliefs with the prophet Elijah Muhammad, who created his own sect of Islam based partly on myths of the African American race and bits and pieces of Orthodox Islam as practiced in Middle East countries.

This was not an easy transition for Malcolm because his former life was entrenched in his thinking and actions. However, over a period of learning more about the Nation of Islam (NOI) and Allah, Malcolm was persuaded to adopt this new belief system that elevated African Americans, instead of reducing them to lowest level of existence. Malcolm X notes, “Christian religion . . . taught the ‘Negro’ that black was a curse [and] it taught him to hate everything black, including himself” (Haley 1965 , 188). And for Malcolm, reading and studying about Africans and African Americans in the context of the NOI affirmed his humanity. Malcolm paralleled his spiritual conversion to that of the biblical figure Paul on the road to Damascus: “I do not now, and I did not then, liken myself to Paul . . . But I do understand his experience” (Haley 1965 , 189). This statement is somewhat ironic in that Malcolm would compare his spiritual awakening to that of a Christian prophet considering he vehemently rejects Christianity throughout his narrative. One can also argue that this comparison is a foreshadowing of Malcolm’s lifelong search for truth as well as an indication of the internal warring with which he wrestled until his death. Nevertheless, this revelation for Malcolm would now begin to inform his thoughts and actions inside of prison as well as how he perceived others. A pivotal part of Malcolm’s salvation experience or surrendering his life to a higher power was his willingness to begin writing letters to Elijah Muhammad and family members to gain a greater understanding of the NOI. This is not surprising because Malcolm was a student of life, and his classroom was now a jail cell instead of the streets of Harlem. Nonetheless, Malcolm was arrested in Boston. In his autobiography, he reflects on the use of a dictionary as the teaching tool that liberated him to freely express himself. Malcolm referred to it as his homemade education. He notes, “Between Mr. Muhammad’s teachings, my correspondence, my visitors . . . and my reading of books, months passed without my even thinking about being imprisoned . . . In fact, up to then, I never had been so truly free in my life” (Haley 1965 , 199). This moment in text illustrates not only Malcolm’s mental awakening but also the spiritual stirring to know Allah.

Furthermore, the most difficult aspect of submitting to Allah for Malcolm was learning to pray. This meant becoming completely vulnerable and admitting that he needed help from a higher power if he was going to make it through his prison experience. Malcolm contends, “I had to force myself to bend my knees and waves of shame and embarrassment would force me back up . . . For evil to bend its knees, admitting its guilt, to implore the forgiveness of God was the hardest thing in the world . . . Again, again, I would force myself back down into the praying-to-Allah posture” (Haley 1965 , 197). This act of submission by Malcolm helped him to understand that his life consisted of not just the experiences of his past, but that there was also a future awaiting his rise from obscurity. In addition, as Malcolm continued to grow in his faith and understanding of the NOI, the more he wanted to learn and apply the doctrine to his life.

Elijah Muhammad’s brand of Islam was based on an individual by the name of W.D. Fard, who was seminal to the movement in the 1930s. Fard reportedly knocked on the doors of African American families and proclaimed that their true religious identity was Islam. Religious historian Edward Curtis contends, “Fard stayed in Detroit only a little while before disappearing from the city, but his movement would have an impact on the entire country” (Curtis 2006 , 2). Elijah Poole, who embraced Fard’s brand of Islam, changed his name to Elijah Muhammad and eventually began to follow the earlier teachings of Fard. Curtis points out, “Elijah Muhammad’s movement would cement itself in American historical memory as a black nationalist organization committed to racial separation and ethnic pride” (Curtis 2006 ). Muhammad began proselytizing in the same geographical region of Detroit where W.D. Fard mysteriously vanished; however, Muhammad’s separatist message soon spread to other regions of the USA and even abroad. African Americans were drawn to Muhammad’s message of racial solidarity because it affirmed their humanity, in time of extreme social and racial oppression. This message was not only preached in the ghettos and urban spaces of America but also spread to prisons as a theology of liberation for the African American male. The NOI reached many Black males in prison because the organization addressed issues of racism and poverty in Black communities, the breakdown of the Black family, rising rates of prisoners of color, and a lack of spiritual guidance. These issues were pertinent to both incarcerated and free Blacks, thus making Muhammad’s message of liberation viable to hopeful new converts and intriguing to those somewhat skeptical.

This new belief system set Malcolm on a path toward self-actualization. He was drawn to the NOI along with many other African American male inmates because this religious organization placed a heavy emphasis on Black identity and manhood. Sociologist Magnus O. Bassey suggests, “Islam, according to Malcolm, [meant] freedom, justice, and equality” (Bassey 1999 , 50). Also, Islam offered African Americans a position of authority in the creation story, whereas Christianity reduced them to a cursed existence. Bassey further contends, “Christianity had brainwashed African Americans and left them mentally, morally and spiritually dead” (Bassey 1999 , 50). In addition, Christianity encouraged its followers to seek their resolve and rest from life’s challenges in the afterlife. Bassey also insists, “Malcolm recognized that Christianity misdirected black rage away from white racism and toward another world of heaven and sentimental romance” (Bassey 1999 ). One can reason that prison inmates are more concerned with addressing their current needs and frustrations than with looking to a heaven that may or may not exist. The NOI was able to capitalize on the emotional vulnerability of inmates by promising them a salvation that addressed issues of incarceration, poverty, family, and spirituality. In doing so, Muhammad was able to appeal to the prisoner’s sense of loss of self as well as his culture. Malcolm and many other inmates were imprisoned physically and emotionally by what they perceived to be an all-white judicial system with little to no empathy for the Black man. Muhammad knew many of the men he targeted in prison to convert were from impoverished backgrounds and the victims of a racist judicial system, so he took advantage of their vulnerable emotional state and lured many of them to the NOI by demonizing the white race.

One of Malcolm’s first letters from Muhammad underscores the plight of the Black prisoner from his vantage point. Muhammad wrote, “The black prisoner symbolized white society’s crime of keeping black men oppressed and deprived and ignorant, and unable to get decent jobs, turning them into criminals” (Haley 1965 , 195). While Muhammad’s letters and methods for recruiting men in prison were divisive, he was able to shift the focus of the prisoner’s responsibility back to the problem of race in America. Zoe Colley contends, “The influence of the imprisoned Muslims stretched across the prison walls to help shape the NOI’s critique of white privilege and its ideological appeal within ghettos” (Colley 2014 , 396). The NOI’s doctrine went to great lengths to parallel the existence of Black prisoners to free Blacks living under an oppressive and racist regime.

In addition, Muhammad promised his new converts if they prayed to Allah, a change in their lives would occur. Muhammad’s Islam was predicated on the following core values: uplift of the Black race, manhood, and moral transformation. Magnus Bassey suggests, “By becoming a Muslim, the African American becomes a man . . . [and] his lost identity is rediscovered, his never-experienced dignity dawns and he enters life” (Bassey 1999 , 53). The promise of manhood or the affirming of an inmate’s manhood is what caused the NOI to appeal to so many convicts who lived at the lowest level of existence inside a jail cell and who were also told by the Christian religion that their race was cursed. Anna Hartwell argues, “The Nation offered a nexus of identifications that seemingly existed outside US structures of oppression that nurtured the devastating conjunction of racism and urban poverty” (Hartwell 2008 , 209). One of the primary goals of the NOI was to empower African American males by providing them with opportunities for personal growth. Furthermore, Muhammad drew from his own imprisonment in the 1940s for refusing to register for the World War II draft (Colley 2014 ). Muhammad made sure he appealed to the prisoner’s deepest need for human connection and support. Black inmates who felt demoralized and unable to survive emotionally under oppressive penal institutions gravitated toward the NOI because the organization validated their humanity. Colley further asserts, “For African American prisoners, the crucial element of this philosophy was the promise of redemption and hope for the future” (Colley 2014 , 402). The NOI did not completely ignore Black criminality; however, the organization chose to place a greater emphasis on the goodness they believed every prisoner was capable of demonstrating.

Also, Muhammad and his followers understood the problem of recidivism that was all too common among inmates, so they worked very hard to present a religious philosophy that addressed every aspect of man’s existence. NOI members were instructed to adhere to moral decency, respect authority, work hard, live frugally, avoid certain foods, and abstain from alcohol and drugs. Moreover, the NOI also called for political, economic, and social separation from White America (Colley 2014 ). This separation drew Malcolm, as well as other Black inmates who were intrigued by a religion that refuted societal claims that they were inferior to other races and destined to live as second-class citizens all their lives. Anna Hartwell suggests, “The Nation offered a vehicle through which US blacks might shake off the post-slavery legacy of endemic racism – racism that some brands of Christianity had so enthusiastically justified – by opposing, rather than attempting to assimilate with, dominant notions of Americanness” (Hartwell 2008 , 210).

As Malcolm and other inmates accepted the religious ideology espoused by the NOI, many prison officials believed the organization was fashioned to create antagonistic relationships between white prison guards and Black inmates. The fears or distress of prison guards over this religion that captured the minds and hearts of Black inmates through sermons of empowerment and pride in the Black race troubled prison officials to the point that some penal sites forbade inmates to practice Islam. As the NOI’s membership in prisons increased, so did the resistance from prison officials, which resulted in Black protest movements in prisons during the late 1950s. Sociologist James B. Jacobs argues, “Prison officials saw in the Muslims not only a threat to prison authority but also a broader revolutionary challenge to American society” (Jacobs 1979 , 6). Prison inmates protested against personal, social, and religious injustices. Many of the same injustices that catalyzed racial and social movements outside of prison mirrored the movements that were then taking place inside American prisons.

Moreover, as Black Muslim inmates continued to protest for their rights to practice their beliefs and to proselytize, prison officials persisted in their efforts to hinder them. Prison administrators believed racial hatred was at the core of Black Muslim ideology, which resulted in anarchy. Contrary to the thoughts and feelings of prison officials, Black Muslims claimed white prison officials routinely continued the oppression of American Blacks (Jacobs 1979 ). What made Black Muslims such a force inside of prisons was that they challenged the caste system, defied penal policies, and initiated litigation. As a result of their willingness to fight for religious and social freedom behind bars, many inmates were politicized in prison in the late 1950s and 1960s. This politicization also stemmed from civil rights groups that did not share all the values of Black Muslims but still recognized the importance of fighting injustice in all areas of society. As Malcolm experienced what he believed to be the sting of injustice, he also went through a spiritual transformation that helped him to see the plight of Black prisoners and Black men in general from a new perspective.

Once he accepted Allah as his God, his mission shifted to sharing the liberating truths of The Nation of Islam with other inmates. Upon his release from prison in 1952, Malcolm immersed himself in the teaching of Muhammad’s and the work of the NOI. A year later, he was appointed by Muhammad as Detroit Temple Number One’s Assistant Minister (Haley 1965 ). This appointment allowed Malcolm X to spread the message of Black pride and racial uplift on a fulltime basis. This was yet another pivotal moment in Malcolm’s journey because he abandoned a former life on the streets and embraced a spiritual charge to transform himself and his community.

In doing so, he also further distanced himself from the white race and Christianity because, from his vantage point, they both represented oppression. Malcolm’s early messages to Black Muslims and bystanders were reminiscent of those of his father Earl Little, who also preached a controversial religious and political ideology. Anna Hartwell argues, “The Nation’s appropriation of Garveyism – as well as other sources of 19th century as well as 20th century black nationalism – thus hung onto its central symbols while displacing the Christian account of divine authority” (Hartwell 2008 ). Malcolm believed that Islam was a special religion for African American males, who in his opinion were misguided and conditioned to view themselves as inferior beings through the eyes of the white race. One can argue that Malcolm’s rejection of the white cultural-political ethos and religion signified an attempt to find a Black political (and, more latently, religious) subjectivity that would support his self-worth and agency (LaMothe 2009 ). This was evident in Malcolm’s desire as a teenager and young adult to fully fit into the Black urban spaces of Harlem and Boston, where Black subjectivity was affirmed and celebrated. In these spaces, Malcolm absorbed the Black ethos with its idioms and values and its rich stories and rituals though this did not include the Black Christian ethos (LaMothe 2009 ). From his perspective, Christian teachings and practices hampered the advancement of Blacks whereas Islam promoted Black empowerment and self-reliance.

Under the tutelage of Muhammad, Malcolm immersed himself in a new way of thinking and living as one of the organization’s ministers. In addition, his apprenticeship with Muhammad stirred within Malcolm a reverence that was far greater than any feelings he had ever experienced for another human being. As a result of such a great adoration, Malcolm worked very hard to prove his loyalty to Muhammad as well as his devotion to Allah. Everything Malcolm learned through the reading of the Quran and his time with Muhammad, he shared with parishioners and potential converts on the streets of Detroit and in other cities.

In 1959, a nationally televised documentary The Hate That Hate Produced gave Americans their first intimate view of the NOI and its philosophical teachings. Before the documentary, the NOI existed in obscurity from a large portion of the American public. The documentary brought more notoriety to the NOI as well as critics who believed the organization was encouraging hatred toward people who were not of African descent. Edward Curtis claims, “The [expose] on the NOI was generally negative, criticizing the movement as an anti-American or black supremacist group” (Curtis 2006 , 4). The undesirable portrayal of the NOI caused many national leaders, Black, and white, to condemn the organization for its separatist ideology. According to Manning Marable, “Malcolm himself thought the show had demonized the Nation, and likened its impact to what happened back in 1938 when Orson Wells frightened America with a radio program describing, as though it was happening, an invasion by men from Mars” (Manning 2011 , 162). While detractors attacked the Nation for its controversial beliefs and practices, Malcolm remained steadfast to his convictions and loyalty to the NOI’s mission. He continued to represent the Nation even though some members within the organization began to view his charismatic approach and motives as self-serving.