An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Reumatologia

- v.59(1); 2021

Peer review guidance: a primer for researchers

Olena zimba.

1 Department of Internal Medicine No. 2, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

Armen Yuri Gasparyan

2 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK

The peer review process is essential for quality checks and validation of journal submissions. Although it has some limitations, including manipulations and biased and unfair evaluations, there is no other alternative to the system. Several peer review models are now practised, with public review being the most appropriate in view of the open science movement. Constructive reviewer comments are increasingly recognised as scholarly contributions which should meet certain ethics and reporting standards. The Publons platform, which is now part of the Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), credits validated reviewer accomplishments and serves as an instrument for selecting and promoting the best reviewers. All authors with relevant profiles may act as reviewers. Adherence to research reporting standards and access to bibliographic databases are recommended to help reviewers draft evidence-based and detailed comments.

Introduction

The peer review process is essential for evaluating the quality of scholarly works, suggesting corrections, and learning from other authors’ mistakes. The principles of peer review are largely based on professionalism, eloquence, and collegiate attitude. As such, reviewing journal submissions is a privilege and responsibility for ‘elite’ research fellows who contribute to their professional societies and add value by voluntarily sharing their knowledge and experience.

Since the launch of the first academic periodicals back in 1665, the peer review has been mandatory for validating scientific facts, selecting influential works, and minimizing chances of publishing erroneous research reports [ 1 ]. Over the past centuries, peer review models have evolved from single-handed editorial evaluations to collegial discussions, with numerous strengths and inevitable limitations of each practised model [ 2 , 3 ]. With multiplication of periodicals and editorial management platforms, the reviewer pool has expanded and internationalized. Various sets of rules have been proposed to select skilled reviewers and employ globally acceptable tools and language styles [ 4 , 5 ].

In the era of digitization, the ethical dimension of the peer review has emerged, necessitating involvement of peers with full understanding of research and publication ethics to exclude unethical articles from the pool of evidence-based research and reviews [ 6 ]. In the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, some, if not most, journals face the unavailability of skilled reviewers, resulting in an unprecedented increase of articles without a history of peer review or those with surprisingly short evaluation timelines [ 7 ].

Editorial recommendations and the best reviewers

Guidance on peer review and selection of reviewers is currently available in the recommendations of global editorial associations which can be consulted by journal editors for updating their ethics statements and by research managers for crediting the evaluators. The International Committee on Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) qualifies peer review as a continuation of the scientific process that should involve experts who are able to timely respond to reviewer invitations, submitting unbiased and constructive comments, and keeping confidentiality [ 8 ].

The reviewer roles and responsibilities are listed in the updated recommendations of the Council of Science Editors (CSE) [ 9 ] where ethical conduct is viewed as a premise of the quality evaluations. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) further emphasizes editorial strategies that ensure transparent and unbiased reviewer evaluations by trained professionals [ 10 ]. Finally, the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) prioritizes selecting the best reviewers with validated profiles to avoid substandard or fraudulent reviewer comments [ 11 ]. Accordingly, the Sarajevo Declaration on Integrity and Visibility of Scholarly Publications encourages reviewers to register with the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) platform to validate and publicize their scholarly activities [ 12 ].

Although the best reviewer criteria are not listed in the editorial recommendations, it is apparent that the manuscript evaluators should be active researchers with extensive experience in the subject matter and an impressive list of relevant and recent publications [ 13 ]. All authors embarking on an academic career and publishing articles with active contact details can be involved in the evaluation of others’ scholarly works [ 14 ]. Ideally, the reviewers should be peers of the manuscript authors with equal scholarly ranks and credentials.

However, journal editors may employ schemes that engage junior research fellows as co-reviewers along with their mentors and senior fellows [ 15 ]. Such a scheme is successfully practised within the framework of the Emerging EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) Network (EMEUNET) where seasoned authors (mentors) train ongoing researchers (mentees) how to evaluate submissions to the top rheumatology journals and select the best evaluators for regular contributors to these journals [ 16 ].

The awareness of the EQUATOR Network reporting standards may help the reviewers to evaluate methodology and suggest related revisions. Statistical skills help the reviewers to detect basic mistakes and suggest additional analyses. For example, scanning data presentation and revealing mistakes in the presentation of means and standard deviations often prompt re-analyses of distributions and replacement of parametric tests with non-parametric ones [ 17 , 18 ].

Constructive reviewer comments

The main goal of the peer review is to support authors in their attempt to publish ethically sound and professionally validated works that may attract readers’ attention and positively influence healthcare research and practice. As such, an optimal reviewer comment has to comprehensively examine all parts of the research and review work ( Table I ). The best reviewers are viewed as contributors who guide authors on how to correct mistakes, discuss study limitations, and highlight its strengths [ 19 ].

Structure of a reviewer comment to be forwarded to authors

Some of the currently practised review models are well positioned to help authors reveal and correct their mistakes at pre- or post-publication stages ( Table II ). The global move toward open science is particularly instrumental for increasing the quality and transparency of reviewer contributions.

Advantages and disadvantages of common manuscript evaluation models

Since there are no universally acceptable criteria for selecting reviewers and structuring their comments, instructions of all peer-reviewed journal should specify priorities, models, and expected review outcomes [ 20 ]. Monitoring and reporting average peer review timelines is also required to encourage timely evaluations and avoid delays. Depending on journal policies and article types, the first round of peer review may last from a few days to a few weeks. The fast-track review (up to 3 days) is practised by some top journals which process clinical trial reports and other priority items.

In exceptional cases, reviewer contributions may result in substantive changes, appreciated by authors in the official acknowledgments. In most cases, however, reviewers should avoid engaging in the authors’ research and writing. They should refrain from instructing the authors on additional tests and data collection as these may delay publication of original submissions with conclusive results.

Established publishers often employ advanced editorial management systems that support reviewers by providing instantaneous access to the review instructions, online structured forms, and some bibliographic databases. Such support enables drafting of evidence-based comments that examine the novelty, ethical soundness, and implications of the reviewed manuscripts [ 21 ].

Encouraging reviewers to submit their recommendations on manuscript acceptance/rejection and related editorial tasks is now a common practice. Skilled reviewers may prompt the editors to reject or transfer manuscripts which fall outside the journal scope, perform additional ethics checks, and minimize chances of publishing erroneous and unethical articles. They may also raise concerns over the editorial strategies in their comments to the editors.

Since reviewer and editor roles are distinct, reviewer recommendations are aimed at helping editors, but not at replacing their decision-making functions. The final decisions rest with handling editors. Handling editors weigh not only reviewer comments, but also priorities related to article types and geographic origins, space limitations in certain periods, and envisaged influence in terms of social media attention and citations. This is why rejections of even flawless manuscripts are likely at early rounds of internal and external evaluations across most peer-reviewed journals.

Reviewers are often requested to comment on language correctness and overall readability of the evaluated manuscripts. Given the wide availability of in-house and external editing services, reviewer comments on language mistakes and typos are categorized as minor. At the same time, non-Anglophone experts’ poor language skills often exclude them from contributing to the peer review in most influential journals [ 22 ]. Comments should be properly edited to convey messages in positive or neutral tones, express ideas of varying degrees of certainty, and present logical order of words, sentences, and paragraphs [ 23 , 24 ]. Consulting linguists on communication culture, passing advanced language courses, and honing commenting skills may increase the overall quality and appeal of the reviewer accomplishments [ 5 , 25 ].

Peer reviewer credits

Various crediting mechanisms have been proposed to motivate reviewers and maintain the integrity of science communication [ 26 ]. Annual reviewer acknowledgments are widely practised for naming manuscript evaluators and appreciating their scholarly contributions. Given the need to weigh reviewer contributions, some journal editors distinguish ‘elite’ reviewers with numerous evaluations and award those with timely and outstanding accomplishments [ 27 ]. Such targeted recognition ensures ethical soundness of the peer review and facilitates promotion of the best candidates for grant funding and academic job appointments [ 28 ].

Also, large publishers and learned societies issue certificates of excellence in reviewing which may include Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points [ 29 ]. Finally, an entirely new crediting mechanism is proposed to award bonus points to active reviewers who may collect, transfer, and use these points to discount gold open-access charges within the publisher consortia [ 30 ].

With the launch of Publons ( http://publons.com/ ) and its integration with Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), reviewer recognition has become a matter of scientific prestige. Reviewers can now freely open their Publons accounts and record their contributions to online journals with Digital Object Identifiers (DOI). Journal editors, in turn, may generate official reviewer acknowledgments and encourage reviewers to forward them to Publons for building up individual reviewer and journal profiles. All published articles maintain e-links to their review records and post-publication promotion on social media, allowing the reviewers to continuously track expert evaluations and comments. A paid-up partnership is also available to journals and publishers for automatically transferring peer-review records to Publons upon mutually acceptable arrangements.

Listing reviewer accomplishments on an individual Publons profile showcases scholarly contributions of the account holder. The reviewer accomplishments placed next to the account holders’ own articles and editorial accomplishments point to the diversity of scholarly contributions. Researchers may establish links between their Publons and ORCID accounts to further benefit from complementary services of both platforms. Publons Academy ( https://publons.com/community/academy/ ) additionally offers an online training course to novice researchers who may improve their reviewing skills under the guidance of experienced mentors and journal editors. Finally, journal editors may conduct searches through the Publons platform to select the best reviewers across academic disciplines.

Peer review ethics

Prior to accepting reviewer invitations, scholars need to weigh a number of factors which may compromise their evaluations. First of all, they are required to accept the reviewer invitations if they are capable of timely submitting their comments. Peer review timelines depend on article type and vary widely across journals. The rules of transparent publishing necessitate recording manuscript submission and acceptance dates in article footnotes to inform readers of the evaluation speed and to help investigators in the event of multiple unethical submissions. Timely reviewer accomplishments often enable fast publication of valuable works with positive implications for healthcare. Unjustifiably long peer review, on the contrary, delays dissemination of influential reports and results in ethical misconduct, such as plagiarism of a manuscript under evaluation [ 31 ].

In the times of proliferation of open-access journals relying on article processing charges, unjustifiably short review may point to the absence of quality evaluation and apparently ‘predatory’ publishing practice [ 32 , 33 ]. Authors when choosing their target journals should take into account the peer review strategy and associated timelines to avoid substandard periodicals.

Reviewer primary interests (unbiased evaluation of manuscripts) may come into conflict with secondary interests (promotion of their own scholarly works), necessitating disclosures by filling in related parts in the online reviewer window or uploading the ICMJE conflict of interest forms. Biomedical reviewers, who are directly or indirectly supported by the pharmaceutical industry, may encounter conflicts while evaluating drug research. Such instances require explicit disclosures of conflicts and/or rejections of reviewer invitations.

Journal editors are obliged to employ mechanisms for disclosing reviewer financial and non-financial conflicts of interest to avoid processing of biased comments [ 34 ]. They should also cautiously process negative comments that oppose dissenting, but still valid, scientific ideas [ 35 ]. Reviewer conflicts that stem from academic activities in a competitive environment may introduce biases, resulting in unfair rejections of manuscripts with opposing concepts, results, and interpretations. The same academic conflicts may lead to coercive reviewer self-citations, forcing authors to incorporate suggested reviewer references or face negative feedback and an unjustified rejection [ 36 ]. Notably, several publisher investigations have demonstrated a global scale of such misconduct, involving some highly cited researchers and top scientific journals [ 37 ].

Fake peer review, an extreme example of conflict of interest, is another form of misconduct that has surfaced in the time of mass proliferation of gold open-access journals and publication of articles without quality checks [ 38 ]. Fake reviews are generated by manipulating authors and commercial editing agencies with full access to their own manuscripts and peer review evaluations in the journal editorial management systems. The sole aim of these reviews is to break the manuscript evaluation process and to pave the way for publication of pseudoscientific articles. Authors of these articles are often supported by funds intended for the growth of science in non-Anglophone countries [ 39 ]. Iranian and Chinese authors are often caught submitting fake reviews, resulting in mass retractions by large publishers [ 38 ]. Several suggestions have been made to overcome this issue, with assigning independent reviewers and requesting their ORCID IDs viewed as the most practical options [ 40 ].

Conclusions

The peer review process is regulated by publishers and editors, enforcing updated global editorial recommendations. Selecting the best reviewers and providing authors with constructive comments may improve the quality of published articles. Reviewers are selected in view of their professional backgrounds and skills in research reporting, statistics, ethics, and language. Quality reviewer comments attract superior submissions and add to the journal’s scientific prestige [ 41 ].

In the era of digitization and open science, various online tools and platforms are available to upgrade the peer review and credit experts for their scholarly contributions. With its links to the ORCID platform and social media channels, Publons now offers the optimal model for crediting and keeping track of the best and most active reviewers. Publons Academy additionally offers online training for novice researchers who may benefit from the experience of their mentoring editors. Overall, reviewer training in how to evaluate journal submissions and avoid related misconduct is an important process, which some indexed journals are experimenting with [ 42 ].

The timelines and rigour of the peer review may change during the current pandemic. However, journal editors should mobilize their resources to avoid publication of unchecked and misleading reports. Additional efforts are required to monitor published contents and encourage readers to post their comments on publishers’ online platforms (blogs) and other social media channels [ 43 , 44 ].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

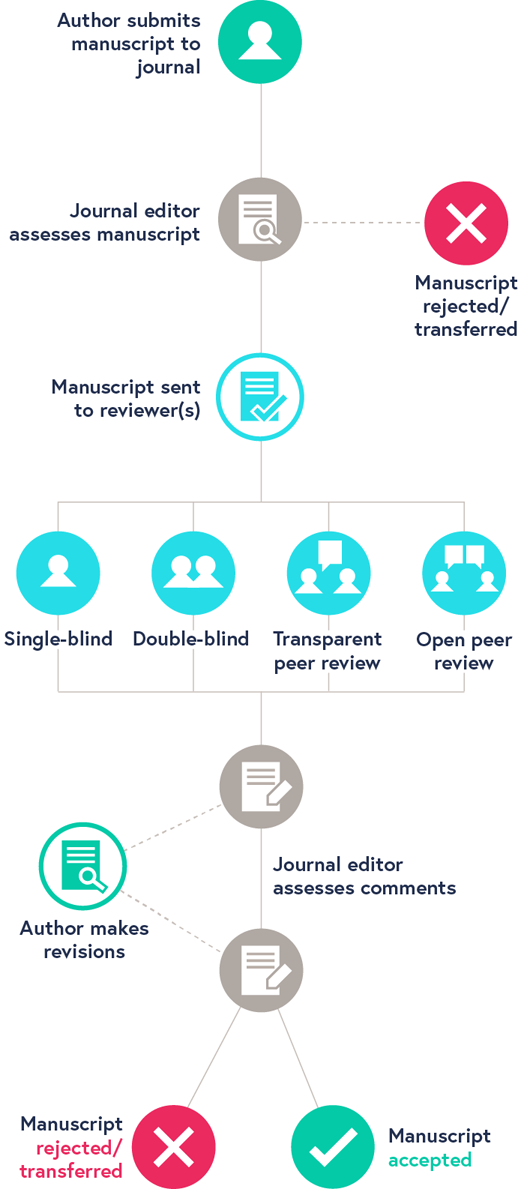

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

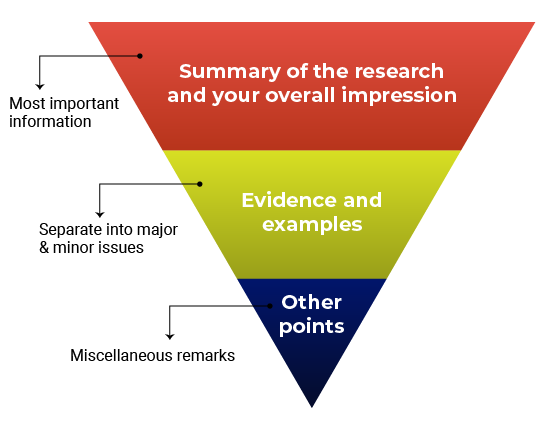

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Understanding Science

How science REALLY works...

- Understanding Science 101

- Peer-reviewed journals are publications in which scientific contributions have been vetted by experts in the relevant field.

- Peer-reviewed articles provide a trusted form of scientific communication. Peer-reviewed work isn’t necessarily correct or conclusive, but it does meet the standards of science.

Scrutinizing science: Peer review

In science, peer review helps provide assurance that published research meets minimum standards for scientific quality. Peer review typically works something like this:

- A group of scientists completes a study and writes it up in the form of an article. They submit it to a journal for publication.

- The journal’s editors send the article to several other scientists who work in the same field (i.e., the “peers” of peer review).

- Those reviewers provide feedback on the article and tell the editor whether or not they think the study is of high enough quality to be published.

- The authors may then revise their article and resubmit it for consideration.

- Only articles that meet good scientific standards (e.g., acknowledge and build upon other work in the field, rely on logical reasoning and well-designed studies, back up claims with evidence , etc.) are accepted for publication.

Peer review and publication are time-consuming, frequently involving more than a year between submission and publication. The process is also highly competitive. For example, the highly-regarded journal Science accepts less than 8% of the articles it receives, and The New England Journal of Medicine publishes just 6% of its submissions.

Peer-reviewed articles provide a trusted form of scientific communication. Even if you are unfamiliar with the topic or the scientists who authored a particular study, you can trust peer-reviewed work to meet certain standards of scientific quality. Since scientific knowledge is cumulative and builds on itself, this trust is particularly important. No scientist would want to base their own work on someone else’s unreliable study! Peer-reviewed work isn’t necessarily correct or conclusive, but it does meet the standards of science. And that means that once a piece of scientific research passes through peer review and is published, science must deal with it somehow — perhaps by incorporating it into the established body of scientific knowledge, building on it further, figuring out why it is wrong, or trying to replicate its results.

PEER REVIEW: NOT JUST SCIENCE

Many fields outside of science use peer review to ensure quality. Philosophy journals, for example, make publication decisions based on the reviews of other philosophers, and the same is true of scholarly journals on topics as diverse as law, art, and ethics. Even those outside the research community often use some form of peer review. Figure-skating championships may be judged by former skaters and coaches. Wine-makers may help evaluate wine in competitions. Artists may help judge art contests. So while peer review is a hallmark of science, it is not unique to science.

- Science in action

- Take a sidetrip

What’s peer review good for? To find out, explore what happens when the process is by-passed. Visit Cold fusion: A case study for scientific behavior .

- To find out how to tell if research is peer-reviewed and why this is important, check out this handy guide from Sense About Science .

- Advanced: Visit the Visionlearning website for advanced material on peer review .

- Advanced: Visit The Scientist magazine to learn about how peer review benefits the people doing the reviewing .

Publish or perish?

Copycats in science: The role of replication

Subscribe to our newsletter

- The science flowchart

- Science stories

- Grade-level teaching guides

- Teaching resource database

- Journaling tool

- Misconceptions

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Understanding Peer Review in Science

Peer review is an essential element of the scientific publishing process that helps ensure that research articles are evaluated, critiqued, and improved before release into the academic community. Take a look at the significance of peer review in scientific publications, the typical steps of the process, and and how to approach peer review if you are asked to assess a manuscript.

What Is Peer Review?

Peer review is the evaluation of work by peers, who are people with comparable experience and competency. Peers assess each others’ work in educational settings, in professional settings, and in the publishing world. The goal of peer review is improving quality, defining and maintaining standards, and helping people learn from one another.

In the context of scientific publication, peer review helps editors determine which submissions merit publication and improves the quality of manuscripts prior to their final release.

Types of Peer Review for Manuscripts

There are three main types of peer review:

- Single-blind review: The reviewers know the identities of the authors, but the authors do not know the identities of the reviewers.

- Double-blind review: Both the authors and reviewers remain anonymous to each other.

- Open peer review: The identities of both the authors and reviewers are disclosed, promoting transparency and collaboration.

There are advantages and disadvantages of each method. Anonymous reviews reduce bias but reduce collaboration, while open reviews are more transparent, but increase bias.

Key Elements of Peer Review

Proper selection of a peer group improves the outcome of the process:

- Expertise : Reviewers should possess adequate knowledge and experience in the relevant field to provide constructive feedback.

- Objectivity : Reviewers assess the manuscript impartially and without personal bias.

- Confidentiality : The peer review process maintains confidentiality to protect intellectual property and encourage honest feedback.

- Timeliness : Reviewers provide feedback within a reasonable timeframe to ensure timely publication.

Steps of the Peer Review Process

The typical peer review process for scientific publications involves the following steps:

- Submission : Authors submit their manuscript to a journal that aligns with their research topic.

- Editorial assessment : The journal editor examines the manuscript and determines whether or not it is suitable for publication. If it is not, the manuscript is rejected.

- Peer review : If it is suitable, the editor sends the article to peer reviewers who are experts in the relevant field.

- Reviewer feedback : Reviewers provide feedback, critique, and suggestions for improvement.

- Revision and resubmission : Authors address the feedback and make necessary revisions before resubmitting the manuscript.

- Final decision : The editor makes a final decision on whether to accept or reject the manuscript based on the revised version and reviewer comments.

- Publication : If accepted, the manuscript undergoes copyediting and formatting before being published in the journal.

Pros and Cons

While the goal of peer review is improving the quality of published research, the process isn’t without its drawbacks.

- Quality assurance : Peer review helps ensure the quality and reliability of published research.

- Error detection : The process identifies errors and flaws that the authors may have overlooked.

- Credibility : The scientific community generally considers peer-reviewed articles to be more credible.

- Professional development : Reviewers can learn from the work of others and enhance their own knowledge and understanding.

- Time-consuming : The peer review process can be lengthy, delaying the publication of potentially valuable research.

- Bias : Personal biases of reviews impact their evaluation of the manuscript.

- Inconsistency : Different reviewers may provide conflicting feedback, making it challenging for authors to address all concerns.

- Limited effectiveness : Peer review does not always detect significant errors or misconduct.

- Poaching : Some reviewers take an idea from a submission and gain publication before the authors of the original research.

Steps for Conducting Peer Review of an Article

Generally, an editor provides guidance when you are asked to provide peer review of a manuscript. Here are typical steps of the process.

- Accept the right assignment: Accept invitations to review articles that align with your area of expertise to ensure you can provide well-informed feedback.

- Manage your time: Allocate sufficient time to thoroughly read and evaluate the manuscript, while adhering to the journal’s deadline for providing feedback.

- Read the manuscript multiple times: First, read the manuscript for an overall understanding of the research. Then, read it more closely to assess the details, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Evaluate the structure and organization: Check if the manuscript follows the journal’s guidelines and is structured logically, with clear headings, subheadings, and a coherent flow of information.

- Assess the quality of the research: Evaluate the research question, study design, methodology, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Consider whether the methods are appropriate, the results are valid, and the conclusions are supported by the data.

- Examine the originality and relevance: Determine if the research offers new insights, builds on existing knowledge, and is relevant to the field.

- Check for clarity and consistency: Review the manuscript for clarity of writing, consistent terminology, and proper formatting of figures, tables, and references.

- Identify ethical issues: Look for potential ethical concerns, such as plagiarism, data fabrication, or conflicts of interest.

- Provide constructive feedback: Offer specific, actionable, and objective suggestions for improvement, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of the manuscript. Don’t be mean.

- Organize your review: Structure your review with an overview of your evaluation, followed by detailed comments and suggestions organized by section (e.g., introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion).

- Be professional and respectful: Maintain a respectful tone in your feedback, avoiding personal criticism or derogatory language.

- Proofread your review: Before submitting your review, proofread it for typos, grammar, and clarity.

- Couzin-Frankel J (September 2013). “Biomedical publishing. Secretive and subjective, peer review proves resistant to study”. Science . 341 (6152): 1331. doi: 10.1126/science.341.6152.1331

- Lee, Carole J.; Sugimoto, Cassidy R.; Zhang, Guo; Cronin, Blaise (2013). “Bias in peer review”. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 64 (1): 2–17. doi: 10.1002/asi.22784

- Slavov, Nikolai (2015). “Making the most of peer review”. eLife . 4: e12708. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12708

- Spier, Ray (2002). “The history of the peer-review process”. Trends in Biotechnology . 20 (8): 357–8. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)01985-6

- Squazzoni, Flaminio; Brezis, Elise; Marušić, Ana (2017). “Scientometrics of peer review”. Scientometrics . 113 (1): 501–502. doi: 10.1007/s11192-017-2518-4

Related Posts

Peer review process

Introduction to peer review, what is peer review.

Peer review is the system used to assess the quality of a manuscript before it is published. Independent researchers in the relevant research area assess submitted manuscripts for originality, validity and significance to help editors determine whether a manuscript should be published in their journal.

How does it work?

When a manuscript is submitted to a journal, it is assessed to see if it meets the criteria for submission. If it does, the editorial team will select potential peer reviewers within the field of research to peer-review the manuscript and make recommendations.

There are four main types of peer review used by BMC:

Single-blind: the reviewers know the names of the authors, but the authors do not know who reviewed their manuscript unless the reviewer chooses to sign their report.

Double-blind: the reviewers do not know the names of the authors, and the authors do not know who reviewed their manuscript.

Open peer: authors know who the reviewers are, and the reviewers know who the authors are. If the manuscript is accepted, the named reviewer reports are published alongside the article and the authors’ response to the reviewer.

Transparent peer: the reviewers know the names of the authors, but the authors do not know who reviewed their manuscript unless the reviewer chooses to sign their report. If the manuscript is accepted, the anonymous reviewer reports are published alongside the article and the authors’ response to the reviewer.

Different journals use different types of peer review. You can find out which peer-review system is used by a particular journal in the journal’s ‘About’ page.

Why do peer review?

Peer review is an integral part of scientific publishing that confirms the validity of the manuscript. Peer reviewers are experts who volunteer their time to help improve the manuscripts they review. By undergoing peer review, manuscripts should become:

More robust - peer reviewers may point out gaps in a paper that require more explanation or additional experiments.

Easier to read - if parts of your paper are difficult to understand, reviewers can suggest changes.

More useful - peer reviewers also consider the importance of your paper to others in your field.

For more information and advice on how to get published, please see our blog series here .

How peer review works

The peer review process can be single-blind, double-blind, open or transparent.

You can find out which peer review system is used by a particular journal in the journal's 'About' page.

N. B. This diagram is a representation of the peer review process, and should not be taken as the definitive approach used by every journal.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 2 September 2022.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, frequently asked questions about peer review.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymised) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymised comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymised) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymised) review – where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymised – does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimises potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymise everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimise back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarise the argument in your own words

Summarising the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organised. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticised, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the ‘compliment sandwich’, where you ‘sandwich’ your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarised or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilising rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication.

For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project – provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well regarded.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field.

It acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, September 02). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/peer-reviews/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a double-blind study | introduction & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, data cleaning | a guide with examples & steps.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 12 November 2021

Demystifying the process of scholarly peer-review: an autoethnographic investigation of feedback literacy of two award-winning peer reviewers

- Sin Wang Chong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4519-0544 1 &

- Shannon Mason 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 266 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2655 Accesses

6 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

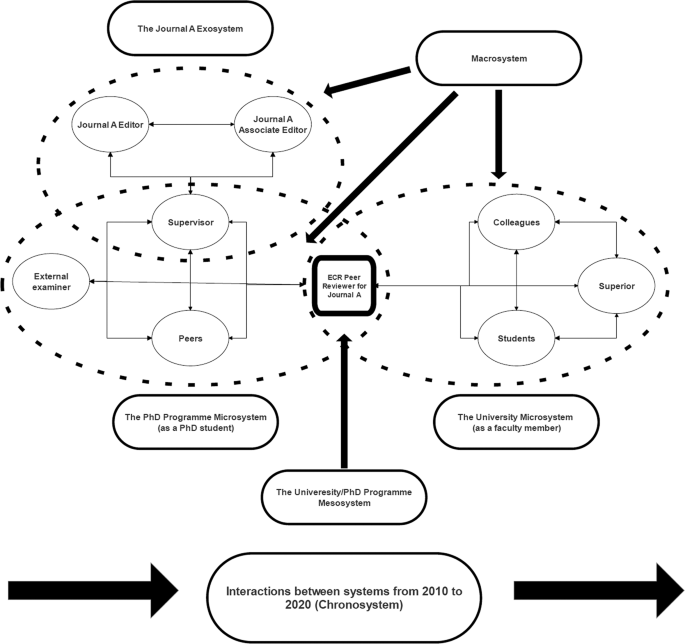

- Language and linguistics

A Correction to this article was published on 26 November 2021

This article has been updated

Peer reviewers serve a vital role in assessing the value of published scholarship and improving the quality of submitted manuscripts. To provide more appropriate and systematic support to peer reviewers, especially those new to the role, this study documents the feedback practices and experiences of two award-winning peer reviewers in the field of education. Adopting a conceptual framework of feedback literacy and an autoethnographic-ecological lens, findings shed light on how the two authors design opportunities for feedback uptake, navigate responsibilities, reflect on their feedback experiences, and understand journal standards. Informed by ecological systems theory, the reflective narratives reveal how they unravel the five layers of contextual influences on their feedback practices as peer reviewers (micro, meso, exo, macro, chrono). Implications related to peer reviewer support are discussed and future research directions are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

The transformative power of values-enacted scholarship

Nicky Agate, Rebecca Kennison, … Penelope Weber

What matters in the cultivation of student feedback literacy: exploring university EFL teachers’ perceptions and practices

Zhenfang Xie & Wen Liu

Writing impact case studies: a comparative study of high-scoring and low-scoring case studies from REF2014

Bella Reichard, Mark S Reed, … Andrea Whittle

Introduction

The peer-review process is the longstanding method by which research quality is assured. On the one hand, it aims to assess the quality of a manuscript, with the desired outcome being (in theory if not always in practice) that only research that has been conducted according to methodological and ethical principles be published in reputable journals and other dissemination outlets (Starck, 2017 ). On the other hand, it is seen as an opportunity to improve the quality of manuscripts, as peers identify errors and areas of weakness, and offer suggestions for improvement (Kelly et al., 2014 ). Whether or not peer review is actually successful in these areas is open to considerable debate, but in any case it is the “critical juncture where scientific work is accepted for publication or rejected” (Heesen and Bright, 2020 , p. 2). In contemporary academia, where higher education systems across the world are contending with decreasing levels of public funding, there is increasing pressure on researchers to be ‘productive’, which is largely measured by the number of papers published, and of funding grants awarded (Kandiko, 2010 ), both of which involve peer review.

Researchers are generally invited to review manuscripts once they have established themselves in their disciplinary field through publication of their own research. This means that for early career researchers (ECRs), their first exposure to the peer-review process is generally as an author. These early experiences influence the ways ECRs themselves conduct peer review. However, negative experiences can have a profound and lasting impact on researchers’ professional identity. This appears to be particularly true when feedback is perceived to be unfair, with feedback tone largely shaping author experience (Horn, 2016 ). In most fields, reviewers remain anonymous to ensure freedom to give honest and critical feedback, although there are concerns that a lack of accountability can result in ‘bad’ and ‘rude’ reviews (Mavrogenis et al., 2020 ). Such reviews can negatively impact all researchers, but disproportionately impact underrepresented researchers (Silbiger and Stubler, 2019 ). Regardless of career phase, no one is served well by unprofessional reviews, which contribute to the ongoing problem of bullying and toxicity prevalent in academia, with serious implications on the health and well-being of researchers (Keashly and Neuman, 2010 ).

Because of its position as the central process through which research is vetted and refined, peer review should play a similarly central role in researcher training, although it rarely features. In surveying almost 3000 researchers, Warne ( 2016 ) found that support for reviewers was mostly received “in the form of journal guidelines or informally as advice from supervisors or colleagues” (p. 41), with very few engaging in formal training. Among more than 1600 reviewers of 41 nursing journals, only one third received any form of support (Freda et al., 2009 ), with participants across both of these studies calling for further training. In light of the lack of widespread formal training, most researchers learn ‘on the job’, and little is known about how researchers develop their knowledge and skills in providing effective assessment feedback to their peers. In this study, we undertake such an investigation, by drawing on our first-hand experiences. Through a collaborative and reflective process, we look to identify the forms and forces of our feedback literacy development, and seek to answer specifically the following research questions:

What are the exhibited features of peer reviewer feedback literacy?

What are the forces at work that affect the development of feedback literacy?

Literature review

Conceptualisation of feedback literacy.

The notion of feedback literacy originates from the research base of new literacy studies, which examines ‘literacies’ from a sociocultural perspective (Gee, 1999 ; Street, 1997 ). In the educational context, one of the most notable types of literacy is assessment literacy (Stiggins, 1999 ). Traditionally, assessment literacy is perceived as one of the indispensable qualities of a successful educator, which refers to the skills and knowledge for teachers “to deal with the new world of assessment” (Fulcher, 2012 , p. 115). Following this line of teacher-oriented assessment literacy, recent attempts have been made to develop more subject-specific assessment literacy constructs (e.g., Levi and Inbar-Lourie, 2019 ). Given the rise of student-centred approaches and formative assessment in higher education, researchers began to make the case for students to be ‘assessment literate’; comprising of such knowledge and skills as understanding of assessment standards, the relationship between assessment and learning, peer assessment, and self-assessment skills (Price et al., 2012 ). Feedback literacy, as argued by Winstone and Carless ( 2019 ), is essentially a subset of assessment literacy because “part of learning through assessment is using feedback to calibrate evaluative judgement” (p. 24). The notion of feedback literacy was first extensively discussed by Sutton ( 2012 ) and more recently by Carless and Boud ( 2018 ). Focusing on students’ feedback literacy, Sutton ( 2012 ) conceptualised feedback literacy as a three-dimensional construct—an epistemological dimension (what do I know about feedback?), an ontological dimension (How capable am I to understand feedback?), and a practical dimension (How can I engage with feedback?). In close alignment with Sutton’s construct, the seminal conceptual paper by Carless and Boud ( 2018 ) further illustrated the four distinctive abilities of feedback literate students: the abilities to (1) understand the formative role of feedback, (2) make informed and accurate evaluative judgement against standards, (3) manage emotions especially in the face of critical and harsh feedback, and (4) take action based on feedback. Since the publication of Carless and Boud ( 2018 ), student and teacher feedback literacy has been in the limelight of assessment research in higher education (e.g., Chong 2021b ; Carless and Winstone 2020 ). These conceptual contributions expand the notion of feedback literacy to consider not only the manifestations of various forms of effective student engagement with feedback but also the confluence of contexts and individual differences of students in developing students’ feedback literacy by drawing upon various theoretical perspectives (e.g., ecological systems theory; sociomaterial perspective) and disciplines (e.g., business and human resource management). Others address practicalities of feedback literacy; for example, how teachers and students can work in synergy to develop feedback literacy (Carless and Winstone, 2020 ) and ways to maximise student engagement with feedback at a curricular level (Malecka et al., 2020). In addition to conceptualisation, advancement of the notion of feedback literacy is evident in the recent proliferation of primary studies. The majority of these studies are conducted in the field of higher education, focusing mostly on student feedback literacy in classrooms (e.g., Molloy et al., 2019 ; Winstone et al., 2019 ) and in the workplace (Noble et al., 2020 ), with a handful focused on teacher feedback literacy (e.g., Xu and Carless 2016 ). Some studies focusing on student feedback literacy adopt a qualitative case study research design to delve into individual students’ experience of engaging with various forms of feedback. For example, Han and Xu ( 2019 ) analysed the profiles of feedback literacy of two Chinese undergraduate students. Findings uncovered students’ resistance to engagement with feedback, which relates to the misalignment between the cognitive, social, and affective components of individual students’ feedback literacy profiles. Others reported interventions designed to facilitate students’ uptake of feedback, focusing on their effectiveness and students’ perceptions. Specifically, affordances and constraints of educational technology such as electronic feedback portfolio (Chong, 2019 ; Winstone et al., 2019 ) are investigated. Of particular interest is a recent study by Noble et al. ( 2020 ), which looked into student feedback literacy in the workplace by probing into the perceptions of a group of Australian healthcare students towards a feedback literacy training programme conducted prior to their placement. There is, however, a dearth of primary research in other areas where elicitation, process, and enactment of feedback are vital; for instance, academics’ feedback literacy. In the ‘publish or perish’ culture of higher education, academics, especially ECRs, face immense pressure to publish in top-tiered journals in their fields and face the daunting peer-review process, while juggling other teaching and administrative responsibilities (Hollywood et al., 2019 ; Tynan and Garbett 2007 ). Taking up the role of authors and reviewers, researchers have to possess the capacity and disposition to engage meaningfully with feedback provided by peer reviewers and to provide constructive comments to authors. Similar to students, researchers have to learn how to manage their emotions in the face of critical feedback, to understand the formative values of feedback, and to make informed judgements about the quality of feedback (Gravett et al., 2019 ). At the same time, feedback literacy of academics also resembles that of teachers. When considering the kind of feedback given to authors, academics who serve as peer reviewers have to (1) design opportunities for feedback uptake, (2) maintain a professional and supportive relationship with authors, and (3) take into account the practical dimension of giving feedback (e.g., how to strike a balance between quality of feedback and time constraints due to multiple commitments) (Carless and Winstone 2020 ). To address the above, one of the aims of the present study is to expand the application of feedback literacy as a useful analytical lens to areas outside the classroom, that is, scholarly peer-review activities in academia, by presenting, analysing, and synthesising the personal experiences of the authors as successful peer reviewers for academic journals.

Conceptual framework