2.4 Developing a Hypothesis

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis it is imporant to distinguish betwee a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition. He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observation before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [1] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

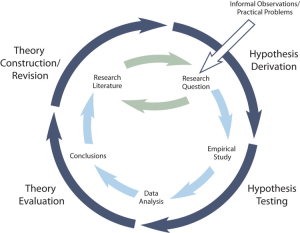

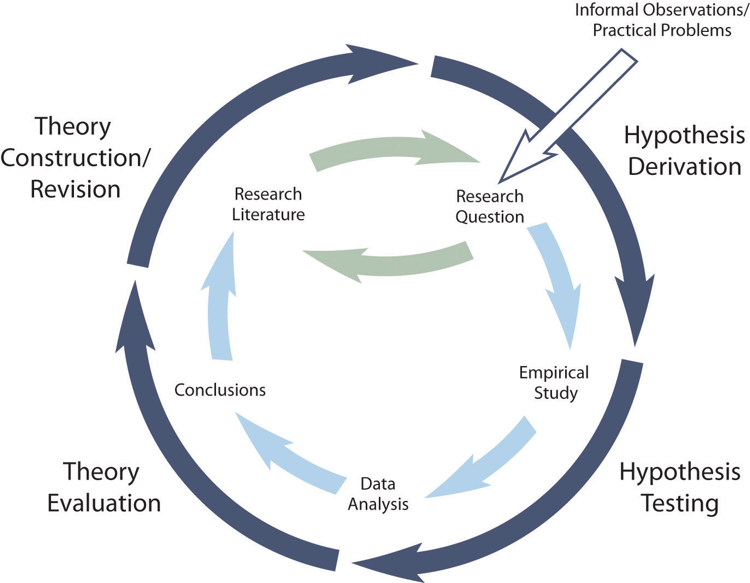

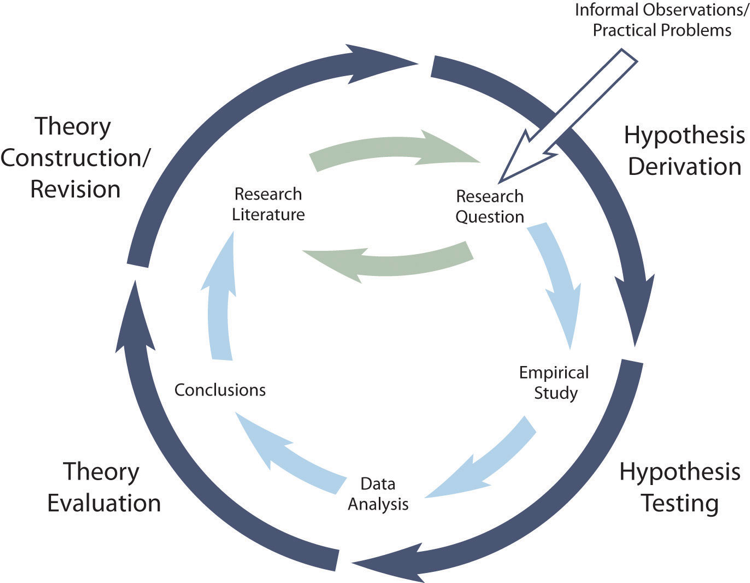

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). A researcher begins with a set of phenomena and either constructs a theory to explain or interpret them or chooses an existing theory to work with. He or she then makes a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researcher then conducts an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, he or she reevaluates the theory in light of the new results and revises it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researcher can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.2 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

Figure 2.2 Hypothetico-Deductive Method Combined With the General Model of Scientific Research in Psychology Together they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [2] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans (Zajonc & Sales, 1966) [3] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that really it does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

Key Takeaways

- A theory is broad in nature and explains larger bodies of data. A hypothesis is more specific and makes a prediction about the outcome of a particular study.

- Working with theories is not “icing on the cake.” It is a basic ingredient of psychological research.

- Like other scientists, psychologists use the hypothetico-deductive method. They construct theories to explain or interpret phenomena (or work with existing theories), derive hypotheses from their theories, test the hypotheses, and then reevaluate the theories in light of the new results.

- Practice: Find a recent empirical research report in a professional journal. Read the introduction and highlight in different colors descriptions of theories and hypotheses.

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Overview of the Scientific Method

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis, it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition (1965) [1] . He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observations before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [2] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

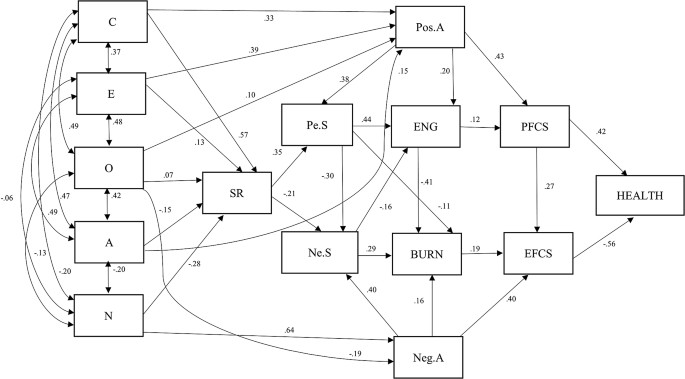

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret them or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.3 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [3] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans [Zajonc & Sales, 1966] [4] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that it really does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149 , 269–274 ↵

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

A coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena.

A specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate.

A cyclical process of theory development, starting with an observed phenomenon, then developing or using a theory to make a specific prediction of what should happen if that theory is correct, testing that prediction, refining the theory in light of the findings, and using that refined theory to develop new hypotheses, and so on.

The ability to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and the possibility to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

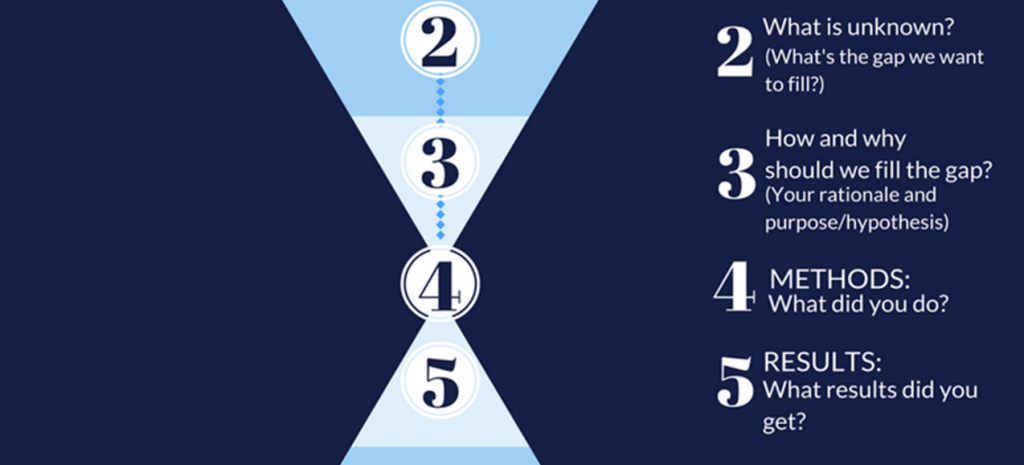

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

Guidelines for Crafting Hypotheses in Psychology

Have you ever wondered what a hypothesis in psychology is and why it is so important? In this article, we will explore the significance of hypotheses in psychology, what makes a good hypothesis, the different types of hypotheses, and how to effectively formulate one.

We will also discuss common mistakes to avoid when crafting hypotheses, so you can ensure your research is clear, testable, and logically sound. Join us as we dive into the world of hypotheses in psychology!

- A hypothesis in psychology is a testable and falsifiable statement that predicts the relationship between variables.

- Hypotheses are crucial in psychology as they guide research and help to test theories and understand human behavior.

- To create a good hypothesis in psychology, it should be based on previous research, specific, logical, and plausible, and include variables, relationship, and specific language.

- 1 What Is a Hypothesis in Psychology?

- 2 Why Are Hypotheses Important in Psychology?

- 3.1 Based on Previous Research

- 3.2 Testable and Falsifiable

- 3.3 Specific and Clear

- 3.4 Logical and Plausible

- 4.1 Research Hypothesis

- 4.2 Null Hypothesis

- 4.3 Directional and Non-Directional Hypotheses

- 4.4 One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Hypotheses

- 5.1 Identify the Variables

- 5.2 Determine the Relationship Between Variables

- 5.3 Use Specific Language and Format

- 6.1 Vague or Ambiguous Language

- 6.2 Biased Hypotheses

- 6.3 Overgeneralization

- 6.4 Ignoring Alternative Explanations

- 7.1 What are the guidelines for crafting hypotheses in psychology?

- 7.2 Why is it important to have clear and testable hypotheses in psychology?

- 7.3 How can I ensure that my hypotheses are relevant to my research question?

- 7.4 Are there specific methods that should be used to test hypotheses in psychology?

- 7.5 What should I do if my hypothesis is not supported by the data?

- 7.6 Can I modify my hypothesis during the research process?

What Is a Hypothesis in Psychology?

In psychology, a hypothesis is a proposed explanation based on research and observations that can be tested through experiments or data analysis.

Hypotheses play a crucial role in psychology by guiding researchers in determining the relationship between different variables. By identifying the specific variables under study, hypotheses help establish a framework for designing experiments. They provide a clear direction for gathering data and analyzing results to either support or reject the proposed explanation. Through this process, hypotheses aid in developing scientific theories by contributing to our understanding of human behavior and mental processes.

Why Are Hypotheses Important in Psychology?

Hypotheses play a crucial role in psychology by guiding research efforts, allowing for testable predictions, and contributing to the advancement of scientific knowledge.

Through hypotheses, researchers can formulate educated guesses about the relationships between different variables in a study. This process helps in establishing the foundation for experiments and investigations in the field of psychology.

Hypotheses enable researchers to structure their studies according to existing theory and previous findings, ensuring that their work aligns with the broader scientific knowledge base.

The formulation and testing of hypotheses are essential components of the scientific method in psychology, driving the field forward with empirical evidence and innovative insights.

What Makes a Good Hypothesis in Psychology?

A good hypothesis in psychology is characterized by being testable , specific, logical, and plausible, setting the foundation for meaningful research outcomes.

Testability is essential as it allows researchers to systematically collect data to support or refute the hypothesis.

Specificity ensures clear direction for the study, outlining the relationship between variables.

Logic aids in constructing a rational and coherent argument, guiding the research methodology.

Plausibility contributes to the credibility of the hypothesis, aligning it with existing knowledge in the field.

Incorporating these key criteria not only enhances the quality of the research but also facilitates effective data collection and analysis.

Based on Previous Research

A hypothesis in psychology should be grounded in previous research findings, drawing upon existing theories and employing sound academic research methodologies to advance knowledge in the field.

By basing hypotheses on prior research, psychologists ensure that their investigations are built upon a solid foundation of established knowledge. This helps in developing testable predictions that contribute to the accumulation of evidence supporting or refuting the proposed relationships between variables.

Proper integration of relevant keywords such as independent and dependent variables further enhances the clarity and specificity of the hypothesis, guiding the direction of the research study. It is through this systematic process of hypothesis development that the scientific rigor and credibility of academic research in psychology is upheld.

Testable and Falsifiable

A key characteristic of a good hypothesis is its testability and falsifiability , allowing researchers to make predictions and conduct statistical analyses to either support or reject the null hypothesis.

Testability ensures that a hypothesis can be systematically tested through empirical observations and experimentation. By formulating clear predictions based on the proposed relationship between variables, researchers can design experiments that generate reliable data .

The falsifiability criterion dictates that a hypothesis must be potentially disprovable, leading to robust scientific inquiry. This process involves challenging the hypothesis with empirical evidence and statistical tests to either confirm its validity or refine scientific understanding.

Specific and Clear

A well-formulated hypothesis in psychology should be specific and clear, outlining the expected relationship between variables and enabling direct comparison of effects or outcomes.

When constructing a hypothesis, it is crucial to consider the theory that underpins the research and the methodology used to test it. By clearly defining the relationship between the variables, researchers can determine the impact of one on the other with precision.

Such precision is essential in psychology as it allows for accurate interpretations of experimental results, leading to a deeper understanding of human behavior and mental processes.

Logical and Plausible

A logical and plausible hypothesis considers potential extraneous variables, incorporates control variables where necessary, and offers a rational explanation for the proposed relationship between variables.

When developing a hypothesis, it’s vital to pay attention to the data being utilized for testing. Statistical analysis plays a key role in substantiating the hypothesized relationships between variables. By carefully selecting control variables, researchers can isolate the effect of the main variables under scrutiny. This process not only enhances the credibility of the study but also ensures that the results are robust and reliable. Considering all these aspects in formulating hypotheses adds depth and validity to the research being conducted.

What Are the Different Types of Hypotheses in Psychology?

Psychology encompasses various types of hypotheses, including research hypotheses, directional and non-directional hypotheses, and one-tailed and two-tailed hypotheses, each serving unique purposes in scientific inquiries.

Research hypotheses are formulated to investigate the relationship between variables, aiming to address specific inquiries and predict outcomes based on previous findings. On the other hand, directional hypotheses propose the direction of the expected effect, predicting that changes in one variable will lead to changes in another. Non-directional hypotheses, however, suggest the presence of an effect but do not specify the relationship’s direction.

Regarding hypothesis testing, the distinction between one-tailed and two-tailed hypotheses is crucial. One-tailed hypotheses make predictions about the direction of an effect, while two-tailed hypotheses consider the possibility of an effect in either direction, providing a more comprehensive approach to testing the research question.

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis in psychology aims to establish a potential relationship between variables, often focusing on correlation or association to test specific theories or predictions.

These hypotheses serve as the foundation for research studies in psychology, guiding the collection and analysis of data through various methods . The testing of hypotheses provides a framework for examining the proposed relationships between variables, allowing researchers to draw conclusions and make inferences based on empirical evidence. By formulating clear and specific hypotheses, psychologists can investigate complex phenomena and contribute to the understanding of human behavior and mental processes.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis serves as the default position in hypothesis testing, providing a baseline for comparison and addressing the presence of research bias in scientific inquiries.

When designing a research study, psychologists carefully construct null hypotheses as essential components of their methodology. These hypotheses allow researchers to investigate whether the observed results are statistically significant or simply occur by chance. By setting up the null hypothesis, researchers can then use statistical analysis to determine if the alternative hypothesis, the one being tested, offers a more plausible explanation. This meticulous approach ensures that potential biases, whether they be participant-related, experimenter-induced, or measurement errors, are adequately addressed and accounted for.

Directional and Non-Directional Hypotheses

Directional hypotheses predict the specific direction of a relationship between variables, while non-directional hypotheses focus on the presence or absence of effects without specifying a particular direction.

In psychology, when researchers formulate hypotheses , they must decide whether they expect a particular outcome or are exploring general effects. This distinction plays a crucial role in the testing and comparison of theories. Directional hypotheses are used when there is prior evidence or theoretical reasoning suggesting a specific relationship between variables. On the other hand, non-directional hypotheses are employed when researchers want to investigate possible effects without bias towards a particular relationship direction.

One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Hypotheses

One-tailed hypotheses focus on predicting an effect in a single direction, while two-tailed hypotheses consider the possibility of effects in both directions, guiding statistical hypothesis testing approaches.

When researchers formulate a one-tailed hypothesis , they are making a specific prediction about the relationship between variables. For instance, in a study examining the impact of exercise on mood, a one-tailed hypothesis might state that increased exercise leads to improved mood. In comparison, a two-tailed hypothesis acknowledges the potential for different outcomes, suggesting that exercise can either positively or negatively influence mood, or that there may be no significant effect at all.

These distinctions in hypotheses not only shape the directionality of predicted effects but also influence the choice of statistical tests used to analyze the data. In a one-tailed hypothesis, statistical testing focuses on demonstrating whether the effect is present in the predicted direction. Conversely, for a two-tailed hypothesis, the analysis considers the significance of the effect regardless of its direction. This nuanced difference guides researchers in interpreting their findings and drawing conclusions based on the hypotheses they have formulated.

How to Formulate a Hypothesis in Psychology?

Formulating a hypothesis in psychology involves identifying relevant variables, determining the expected relationships between them, and employing specific language and formats to express the proposed hypotheses.

When crafting a hypothesis, psychologists carefully consider the data gathered, existing theories, and observations made. By analyzing these components, psychologists can create meaningful and testable hypotheses that contribute to the understanding of human behavior. The process of hypothesis formulation requires a thorough understanding of the subject matter, an ability to link different variables, and a skill in articulating the expected outcomes. Effective hypotheses in psychology typically stem from a blend of empirical evidence, theoretical frameworks, and keen observations.

Identify the Variables

The first step in formulating a hypothesis is to identify the variables involved, distinguishing between independent and dependent variables that form the core elements of the research question.

Independent variables are the factors that are manipulated or controlled by the researcher to observe their effect on the dependent variable, which is the outcome being studied. These variables play a crucial role in determining the relationship between them. It is essential to establish a clear understanding of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables to formulate a hypothesis that can be tested through the research methodology.

Identifying and considering control variables is important to ensure that any observed effects are actually due to the independent variables and not other external factors. Through a systematic approach to variable identification, researchers can construct hypotheses that are precise and facilitate meaningful research outcomes.

Determine the Relationship Between Variables

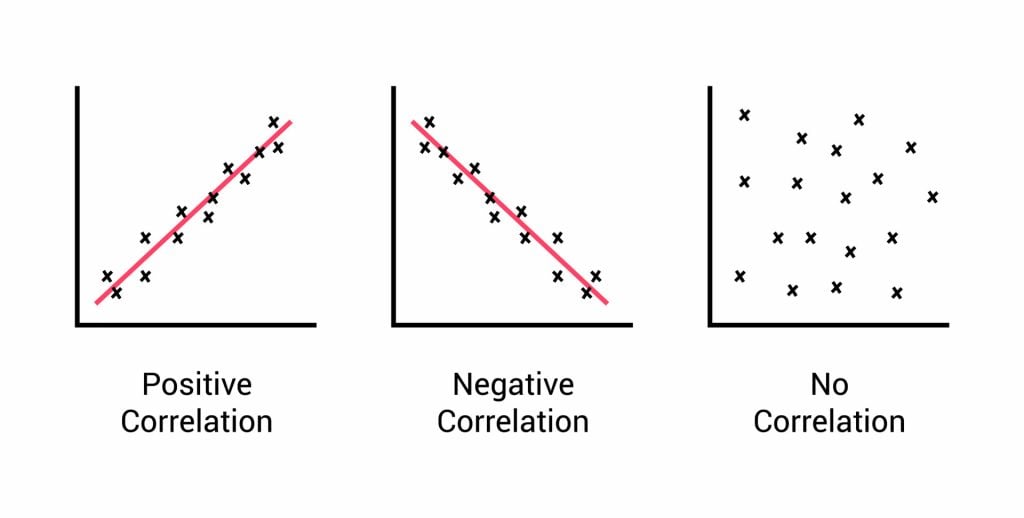

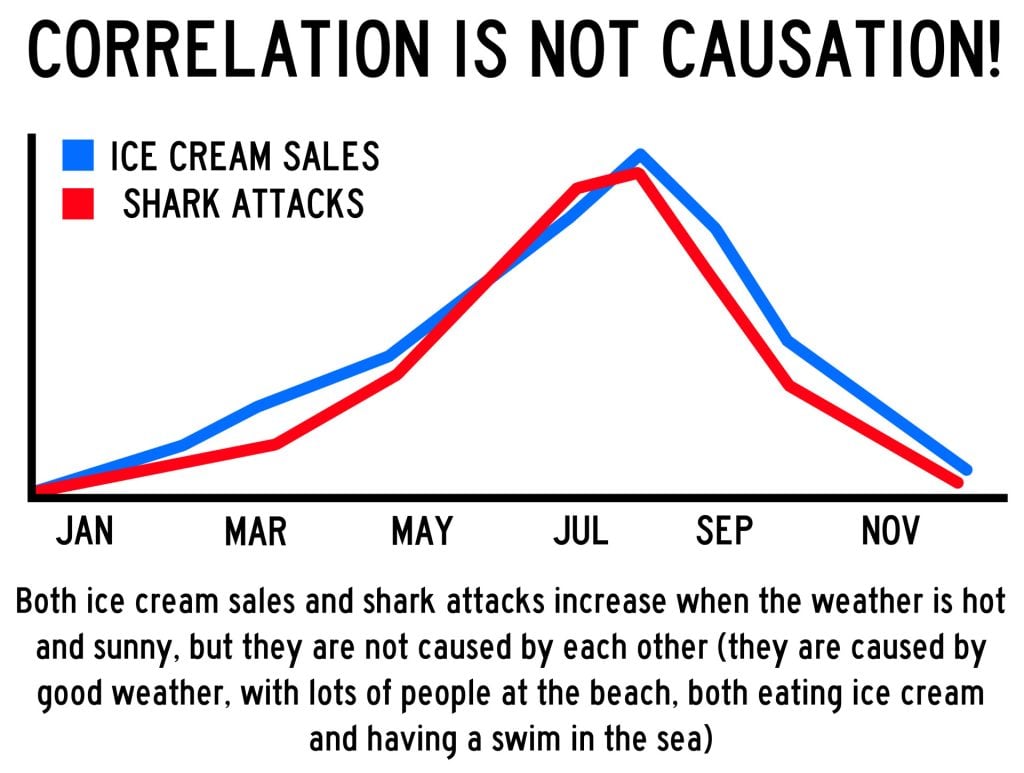

After identifying variables, it is essential to determine the nature of the relationship between them, whether it involves correlation, causation, or other forms of association that can be tested through research.

Establishing relationships between variables in hypothesis formulation is a crucial step in ensuring the integrity of the research. Understanding the types of connections, such as correlation or causation, is vital for constructing testable hypotheses. By examining how variables interact, researchers can uncover potential effects and make meaningful comparisons to derive valuable insights from the data collected. This process not only adds depth to the hypothesis but also sets a solid foundation for the subsequent analysis and interpretation of results.

Use Specific Language and Format

Hypotheses in psychology should be articulated using specific language and formats to ensure clarity, precision, and conciseness in conveying the intended research predictions and relationships between variables.

One of the key elements in crafting a hypothesis is to clearly define the theory or concept being tested, followed by a succinct explanation of the methodology used to collect and analyze data. This structured approach not only enhances the overall coherence of the research design but also enables researchers to systematically evaluate and validate their predictions through rigorous testing procedures.

What Are Common Mistakes to Avoid When Crafting Hypotheses in Psychology?

When crafting hypotheses in psychology, it is crucial to avoid common mistakes such as using vague or ambiguous language, introducing bias, overgeneralizing conclusions, and overlooking alternative explanations.

Clarity and precision are key in hypothesis formulation, as clearly defined statements help in setting the foundation for meaningful data collection and analysis. Introducing bias can skew results and lead to inaccurate conclusions, undermining the validity of the research. Overgeneralization can dilute the impact of the hypothesis, making it less specific and testable. Failure to consider alternative explanations may limit the scope of understanding the phenomenon under investigation, which is essential for robust hypothesis testing in psychology.

Vague or Ambiguous Language

The use of vague or ambiguous language in hypotheses can undermine clarity and precision, potentially leading to misinterpretation of the intended relationships or effects being investigated.

When a hypothesis lacks specificity, it becomes challenging to determine the exact nature of the variables being studied, hindering accurate correlation and comparison.

Without clear and concise language in hypotheses, researchers run the risk of drawing erroneous conclusions or misjudging the significance of their findings.

Articulating hypotheses with precision is crucial for ensuring that the intended relationships or effects are accurately captured and analyzed in scientific research.

Biased Hypotheses

Biased hypotheses in psychology introduce partiality and preconceived notions into research inquiries, potentially skewing results and compromising the validity of the scientific association being studied.

One of the critical aspects of psychology research lies in the formulation and testing of various theories, where biased hypotheses pose a significant threat to the integrity of the entire methodology.

Any form of prejudice, whether conscious or subconscious, can lead to the misinterpretation of data and the false validation of predetermined ideas.

It is imperative for researchers to remain vigilant against such influences, as they can obscure the true nature of human behavior and hinder the progress of scientific understanding.

Overgeneralization

Overgeneralization in hypotheses can lead to sweeping conclusions that extend beyond the scope of the study, potentially distorting the actual effects or comparisons being investigated.

When researchers fail to distinguish between correlation and causation, they risk oversimplifying complex relationships between variables. This could misrepresent the true impact of certain factors under investigation, ultimately compromising the integrity of the data collected. Using a flawed methodology or drawing generalized conclusions without sufficient supporting evidence can undermine the credibility of the entire study, leading to inaccurate interpretations and erroneous conclusions.

Ignoring Alternative Explanations

Neglecting alternative explanations when formulating hypotheses can overlook crucial factors that might influence variables or effects under investigation, leading to incomplete or misleading research outcomes.

It is essential in the scientific realm to consider a wide range of possibilities when constructing a hypothesis, ensuring that all potential influencing factors are taken into account. By conducting thorough experiments and analyses, researchers can deepen their knowledge and minimize the risk of overlooking significant variables.

Accounting for alternative explanations not only enhances the credibility of the findings but also enriches the overall scientific process, fostering a culture of critical thinking and meticulous investigation.

This practice contributes to the advancement of understanding and promotes more robust and reliable results in the realm of scientific inquiry.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the guidelines for crafting hypotheses in psychology.

The guidelines for crafting hypotheses in psychology include identifying the research question, reviewing relevant literature, formulating a clear and testable hypothesis, and selecting appropriate methods for testing the hypothesis.

Why is it important to have clear and testable hypotheses in psychology?

Clear and testable hypotheses in psychology are important because they guide the research process and provide a framework for interpreting results. They also help researchers to avoid bias and ensure the validity and reliability of their findings.

How can I ensure that my hypotheses are relevant to my research question?

To ensure relevance, it is important to thoroughly review relevant literature and theories before formulating a hypothesis. This will help to identify any gaps in knowledge and ensure that the hypothesis is based on established principles and previous research.

Are there specific methods that should be used to test hypotheses in psychology?

Yes, there are various methods that can be used to test hypotheses in psychology, including experiments, surveys, and observational studies. The choice of method will depend on the research question and the type of data that needs to be collected.

What should I do if my hypothesis is not supported by the data?

If your hypothesis is not supported by the data, it is important to acknowledge this and consider alternative explanations for your findings. This can provide valuable insights and lead to further research in the future.

Can I modify my hypothesis during the research process?

Yes, it is common for hypotheses to be modified during the research process as new information is gathered. However, any modifications should be based on sound reasoning and should not deviate too far from the original research question.

Vanessa Patel is an expert in positive psychology, dedicated to studying happiness, resilience, and the factors that contribute to a fulfilling life. Her writing explores techniques for enhancing well-being, overcoming adversity, and building positive relationships and communities. Vanessa’s articles are a resource for anyone looking to find more joy and meaning in their daily lives, backed by the latest research in the field.

Similar Posts

Understanding ‘Manipulate’ in Psychological Context

The article was last updated by Dr. Naomi Kessler on February 9, 2024. Manipulation is a term often associated with negative connotations, but in psychology,…

Exploring Correlational Studies in Psychology: Uncovering Relationships and Connections

The article was last updated by Gabriel Silva on February 6, 2024. Have you ever wondered how psychologists uncover hidden relationships and connections between variables?…

Insights into Interneurons in Psychology

The article was last updated by Dr. Emily Tan on February 4, 2024. Interneurons play a crucial role in the complex network of the brain,…

Exploring Common and Intriguing Psychology Questions for Study and Research

The article was last updated by Lena Nguyen on February 5, 2024. Are you curious about the human mind and behavior? Psychology offers a fascinating…

Understanding the Stroop Effect in Psychology

The article was last updated by Gabriel Silva on February 8, 2024. Have you ever wondered why it is so difficult to say the color…

The Importance of Pilot Studies in Psychology: Exploring Their Purpose and Execution

The article was last updated by Dr. Henry Foster on February 6, 2024. Pilot studies play a crucial role in the field of psychology, helping…

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.4: Developing a Hypothesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 16104

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition. He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observation before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [1] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). A researcher begins with a set of phenomena and either constructs a theory to explain or interpret them or chooses an existing theory to work with. He or she then makes a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researcher then conducts an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, he or she reevaluates the theory in light of the new results and revises it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researcher can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.2 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [2] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans (Zajonc & Sales, 1966) [3] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that really it does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

Key Takeaways

- A theory is broad in nature and explains larger bodies of data. A hypothesis is more specific and makes a prediction about the outcome of a particular study.

- Working with theories is not “icing on the cake.” It is a basic ingredient of psychological research.

- Like other scientists, psychologists use the hypothetico-deductive method. They construct theories to explain or interpret phenomena (or work with existing theories), derive hypotheses from their theories, test the hypotheses, and then reevaluate the theories in light of the new results.

- Practice: Find a recent empirical research report in a professional journal. Read the introduction and highlight in different colors descriptions of theories and hypotheses.

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202.

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92.

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168.

Research Methods In Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Research methods in psychology are systematic procedures used to observe, describe, predict, and explain behavior and mental processes. They include experiments, surveys, case studies, and naturalistic observations, ensuring data collection is objective and reliable to understand and explain psychological phenomena.

Hypotheses are statements about the prediction of the results, that can be verified or disproved by some investigation.

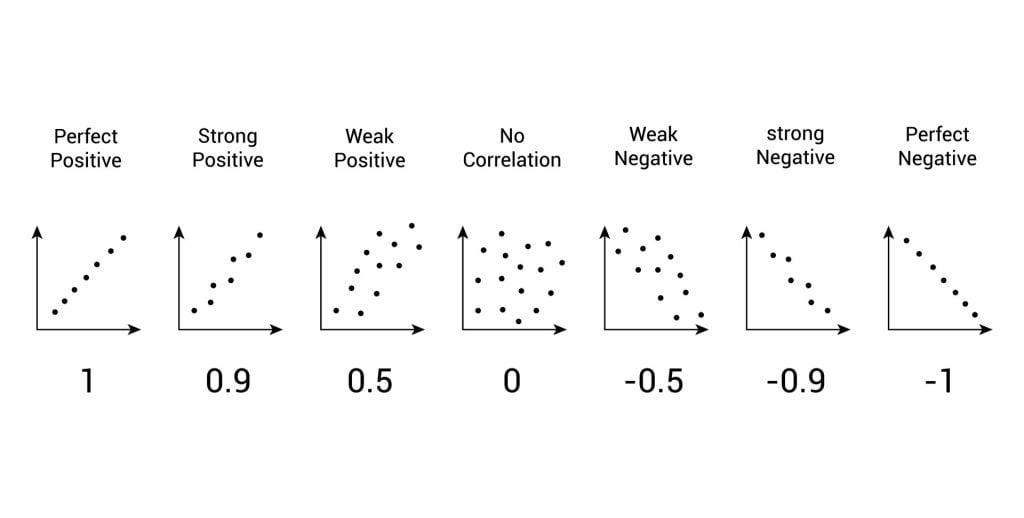

There are four types of hypotheses :

- Null Hypotheses (H0 ) – these predict that no difference will be found in the results between the conditions. Typically these are written ‘There will be no difference…’

- Alternative Hypotheses (Ha or H1) – these predict that there will be a significant difference in the results between the two conditions. This is also known as the experimental hypothesis.

- One-tailed (directional) hypotheses – these state the specific direction the researcher expects the results to move in, e.g. higher, lower, more, less. In a correlation study, the predicted direction of the correlation can be either positive or negative.

- Two-tailed (non-directional) hypotheses – these state that a difference will be found between the conditions of the independent variable but does not state the direction of a difference or relationship. Typically these are always written ‘There will be a difference ….’

All research has an alternative hypothesis (either a one-tailed or two-tailed) and a corresponding null hypothesis.

Once the research is conducted and results are found, psychologists must accept one hypothesis and reject the other.

So, if a difference is found, the Psychologist would accept the alternative hypothesis and reject the null. The opposite applies if no difference is found.

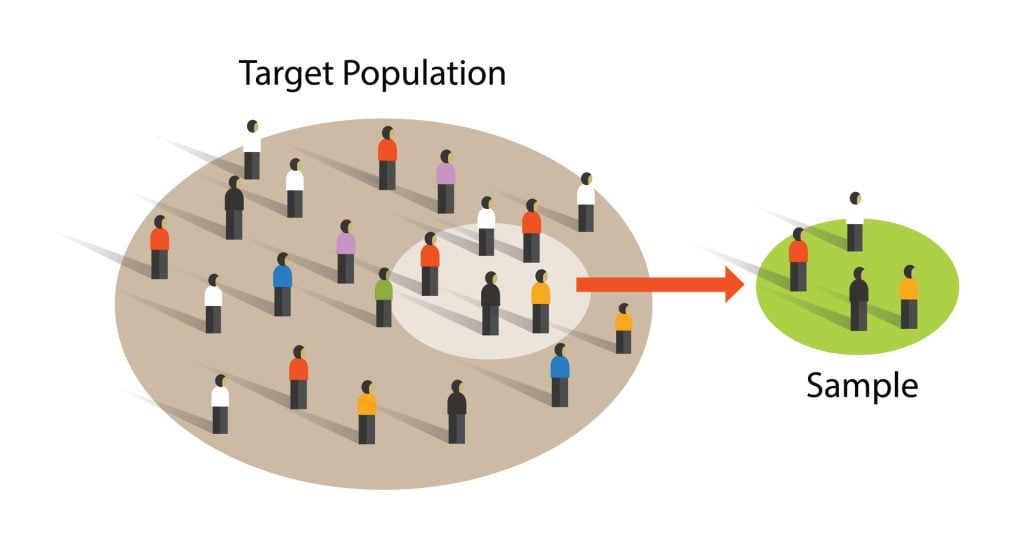

Sampling techniques

Sampling is the process of selecting a representative group from the population under study.

A sample is the participants you select from a target population (the group you are interested in) to make generalizations about.

Representative means the extent to which a sample mirrors a researcher’s target population and reflects its characteristics.

Generalisability means the extent to which their findings can be applied to the larger population of which their sample was a part.

- Volunteer sample : where participants pick themselves through newspaper adverts, noticeboards or online.

- Opportunity sampling : also known as convenience sampling , uses people who are available at the time the study is carried out and willing to take part. It is based on convenience.

- Random sampling : when every person in the target population has an equal chance of being selected. An example of random sampling would be picking names out of a hat.

- Systematic sampling : when a system is used to select participants. Picking every Nth person from all possible participants. N = the number of people in the research population / the number of people needed for the sample.

- Stratified sampling : when you identify the subgroups and select participants in proportion to their occurrences.

- Snowball sampling : when researchers find a few participants, and then ask them to find participants themselves and so on.

- Quota sampling : when researchers will be told to ensure the sample fits certain quotas, for example they might be told to find 90 participants, with 30 of them being unemployed.

Experiments always have an independent and dependent variable .

- The independent variable is the one the experimenter manipulates (the thing that changes between the conditions the participants are placed into). It is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

- The dependent variable is the thing being measured, or the results of the experiment.

Operationalization of variables means making them measurable/quantifiable. We must use operationalization to ensure that variables are in a form that can be easily tested.

For instance, we can’t really measure ‘happiness’, but we can measure how many times a person smiles within a two-hour period.

By operationalizing variables, we make it easy for someone else to replicate our research. Remember, this is important because we can check if our findings are reliable.

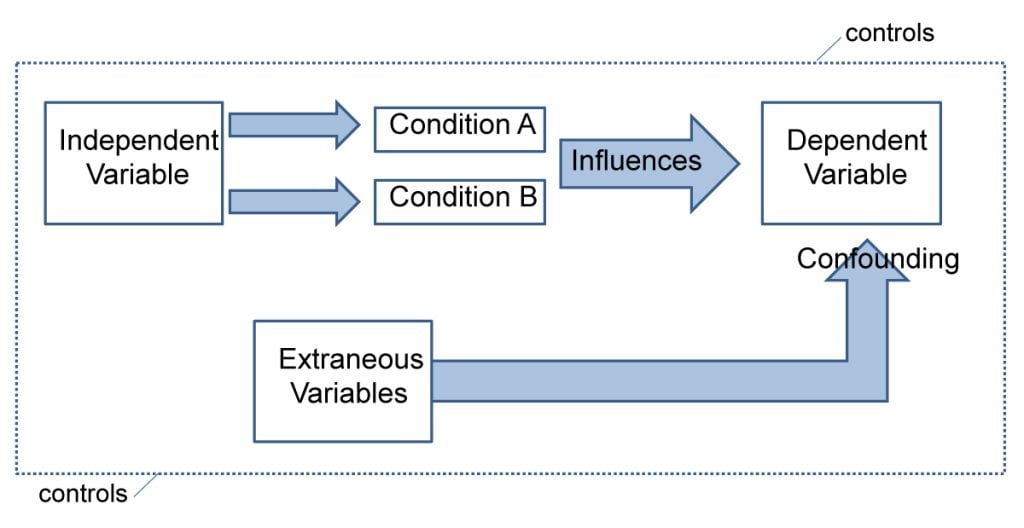

Extraneous variables are all variables which are not independent variable but could affect the results of the experiment.

It can be a natural characteristic of the participant, such as intelligence levels, gender, or age for example, or it could be a situational feature of the environment such as lighting or noise.

Demand characteristics are a type of extraneous variable that occurs if the participants work out the aims of the research study, they may begin to behave in a certain way.

For example, in Milgram’s research , critics argued that participants worked out that the shocks were not real and they administered them as they thought this was what was required of them.

Extraneous variables must be controlled so that they do not affect (confound) the results.

Randomly allocating participants to their conditions or using a matched pairs experimental design can help to reduce participant variables.

Situational variables are controlled by using standardized procedures, ensuring every participant in a given condition is treated in the same way

Experimental Design

Experimental design refers to how participants are allocated to each condition of the independent variable, such as a control or experimental group.