When it Comes to Education, the Federal Government is in Charge of ... Um, What?

- Posted August 29, 2017

- By Brendan Pelsue

Judging by her Senate confirmation process, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos is one of the most controversial members of President Donald Trump’s cabinet. She was the only nominee to receive two “no” votes from members of her own party, Senators Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. On the eve of her confirmation vote, Democrats staged an all-night vigil in which they denounced her from the Senate floor. Following a 50–50 vote, Vice President Mike Pence was summoned in his capacity as president of the Senate to break the tie for DeVos — a first in the Senate’s 228-year history of giving “advice and consent” to presidential cabinet nominees.

Now that DeVos is several months into her tenure as the 11th secretary of education, both her supporters and detractors are paying close attention to the policies she is beginning to implement and how they will change the nation’s public schools. Even for veteran education watchers, however, this is difficult, not only because the Trump administration’s budget and policy proposals are more skeletal than those put forward by previous administrations, but because the Department of Education does not directly oversee the nation’s 100,000 public schools. States have some oversight, but individual municipalities, are, in most cases, the legal entities responsible for running schools and for providing the large majority of funding through local tax dollars.

Still, the federal government uses a complex system of funding mechanisms, policy directives, and the soft but considerable power of the presidential bully pulpit to shape what, how, and where students learn. Anyone hoping to understand the impact of DeVos’ tenure as secretary of education first needs to grasp some core basics: what the federal government controls, how it controls it, and how that balance does (and doesn’t) change from administration to administration.

This policy landscape is the subject of an Ed School course, A-129, The Federal Government and Schools, taught by Lecturer Laura Schifter , Ed.M.'07, Ed.D.'14,, a former senior adviser to Congressman George Miller (D-CA). Schifter has noticed that even for students who have worked in public schools, understanding the federal government’s current role in education can be complicated.

“Students frequently need a refresher on things like understanding the nature of the relationship between the federal government and the states, and what federalism is,” she says. With that in mind, the course begins with a civics review, especially the complicated politics of federalism, then moves on to a history lesson in federal education legislation since the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, and finally to an overview of the actual policy mechanisms through which the federal government enforces and implements the law. Throughout, students “read statutes, they read regulations, they read court decisions,” Schifter says — activities she believes are essential since there is no better way for educators to understand the law than to consult it themselves.

The civics and history lessons required to understand the federal government’s role in education are of course deeply intertwined and begin, as with so many things American, with the Constitution. That document makes no mention of education. It does state in the 10th Amendment that “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution … are reserved to the States respectively.” This might seem to preclude any federal oversight of education, except that the 14th Amendment requires all states to provide “any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

At least since the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, this has been interpreted to give the federal government the power to intervene in cases of legally sanctioned discrimination, like the segregation of public schools across the country; to mandate equal access to education for students with disabilities; and, according to some arguments, to correct for persistently unequal access to resources across states and districts of different income levels. According to Associate Professor Martin West , the government’s historical and current role in education reflects the conflicts inherent in these two central tenets of the nation’s charter.

Before 1965, the 10th Amendment seemed to prevail over the 14th, and federal involvement in K–12 education was minimal. Beginning with Horace Mann in Massachusetts, in the 1830s, states implemented reforms aimed at establishing a free, nonsectarian education system, but most national legislation was aimed at higher education. For example, the 1862 Morrill Act used proceeds from the sale of public lands to establish “land-grant” colleges focused on agriculture and engineering. (Many public universities, like Michigan State and historically black colleges like Tuskegee University, are land-grant institutions.)

And then, in the late 1860s, the first federal Department of Education under President Andrew Johnson was established to track education statistics. It was quickly demoted to “Office” and was not part of the president’s cabinet. It wasn’t until the mid-1960s that the federal government took a more robust role in K–12 education.

The impetus for the change was twofold. The Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which mandated the desegregation of public schools, gave the executive branch a legal precedent for enforcing equal access to education. At the same time, the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik I (and the technological brinksmanship of the Cold War more generally) created an anxiety that the nation’s schools were falling behind.

Those threads came together in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965, a bill designed in part by Francis Keppel , then the commissioner of education (the pre-cabinet-level equivalent of secretary of education) and a transformative dean at the Ed School. The bill was a key part of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty and has set the basic terms of the federal government’s involvement in education ever since.

Rather than mandating direct federal oversight of schools — telling states what to do — ESEA offered states funding for education programs on a conditional basis. In other words, states could receive federal funding provided they met the requirements outlined in certain sections, or titles, of the act.

Every major education initiative since 1965 has been about recalibrating the balance first struck by esea. Until 1980, the program was reauthorized every three years, each time with more specific guidelines about how federal funds were to be used (Title I money has to add to rather than replace locally provided education funding, for example). In 1975, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (now IDEA) ensured that students with disabilities are provided a free appropriate public education to meet their needs. This initial flurry of expansion culminated in 1979, under President Jimmy Carter, with the establishment of the federal Department of Education as a separate, cabinet-level government agency that would coordinate what West calls the “alphabet soup” of the federal government’s various initiatives and requirements.

The Reagan administration briefly rolled back many ESEA provisions, but following the release of the 1983 A Nation at Risk report, which pointed out persistent inequalities in the education system and made unfavorable comparisons between U.S. students and those in other nations, old requirements were restored and new ones added.

The 2001 No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) marked a new level of federal oversight by requiring states to set more rigorous student evaluation standards and, through testing, demonstrate “adequate yearly progress” in how those standards were met. Flaws in the law quickly surfaced. Standards did not take into account the differences between student populations, and so, according to West, the Department of Education often ended up “evaluating schools as much on the students they serve as opposed to their effectiveness in serving them.”

When the Obama administration came to office, it faced a legislative logjam on education. NCLB expired in 2007, but there was no Congressional consensus about the terms of its reauthorization. The administration responded by issuing waivers to states that did not meet nclb standards, provided they adopted other policies the administration favored, like the Common Core standards. At the same time, the Race to the Top program offered competitive grants that awarded points to states based on their implementation of policies like performance-based evaluations. The two programs were seen by many conservatives as executive overreach, and when ESEA was reauthorized in 2015 as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), NCLB standardized testing requirements were kept, but the evaluation and accountability systems meant to respond to the results of those tests became the responsibility of individual states. When DeVos was testifying before the Senate in January 2017, the federal government still had a greater hand in public education than it did at any point before No Child Left Behind, but it had also recently experienced the greatest rollback in its oversight since an era of almost continual expansion that began in 1965.

Back in Schifter’s class, students grapple with simulated versions of the actual dilemma now facing the Trump administration: how to design and implement policy. For Schifter’s students, that means choosing between two final projects: a mock Congressional markup on an education-related bill or a mock grant proposal similar to Race to the Top. For Trump, it means navigating how education policy is shaped by all three branches of government.

Congress has the ability to write statute and distribute funds. If, for example, it releases funds as formula grants, which are distributed to all states on the same basis, it can ensure universal adoption of programs like Title I. Competitive grants like Race to the Top arguably make policy implementation more efficient: the executive branch can regulate, clarify, and be selective about its enforcement of the law. And judicial rulings can redefine what qualifies as implementation of policy, as the Supreme Court did in its 2017 Endrew F. v. Douglas County School Dist. RE-1 ruling, a unanimous decision that interpreted idea as requiring that a disabled student’s “educational program must be appropriately ambitious in light of his circumstances.”

It seems the Department of Education’s approach under DeVos is still taking shape. Some of its actions have been swift and decisive. In February, the Departments of Justice and Education jointly announced they were rescinding the Obama-era guidance protecting transgender students’ right to use a bathroom corresponding with their gender identity.

In other areas, however, the department’s positions have been vague. On Inauguration Day, the administration ordered a freeze on state evaluation and accountability plans for schools, which under essa must be federally approved. In a February 10 letter to chief state school officers, however, DeVos said states should proceed with their proposals. If the department is lenient in its evaluation of these plans, it would amount to a de facto rollback in federal oversight because the Department of Education would be choosing not to exercise its powers to the full extent permitted by law.

The administration’s proposed budget, released in May under the title “A New Foundation for American Greatness,” calls for $500 million dollars in new charter school funding — a 50 percent increase over current levels, but less than the $759 million authorized over the first two years of the George W. Bush administration. The budget also allots an additional $1 billion in “portable” Title I funding, meaning the money would follow students who opt to attend charter or magnet schools (currently it stays in their home districts). Under ESSA, however, much of what was once overseen by the Department of Education has now reverted to the states.

“Ironically, we will see an administration that will be reluctant to dictate specific policies,” says Professor Paul Reville , the Massachusetts Secretary of Education under former Governor Deval Patrick. This doesn’t mean, of course, that the Department of Education and the administration are unable to exert influence, but it appears they are planning to do so through cutbacks rather than new initiatives. Trump’s budget proposes a 13.5 percent cut in the Education Department’s 2018 budget, including a $2.3 billion cut that would eliminate Supporting Effective Instruction States Grants, which fund teacher training and development.

And cutbacks in other areas could also affect students, since not all federal funding for schools comes from the Department of Education. For example, money for the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, whose school lunch nutritional guidelines were recently loosened by an executive order, comes through the Department of Agriculture. Public school employees like occupational and physical therapists bill much of their work through Medicaid, which also provides dental, vision, hearing, and mental health services. Programs like this are at risk in part because the administration’s proposed budget cuts Medicaid by $800 billion dollars.

Beyond the budget specifics, there is also the power of the presidential bully pulpit. Reville cites evidence that the administration’s rhetoric on charter schools and vouchers has already put conservative state governments “on the move, emboldened by the new federal stance on choice.”

The administration’s budget is only, however, a wish list. The actual power to determine federal expenditures rests in the House and the Senate, and even in years of less drastic proposals, legislators often pass a federal budget that looks quite different from the one suggested by the president. Trump’s budget has received pushback, and for some education-minded conservatives, the administration’s advocacy on their behalf is unwelcome. Frederick Hess , Ed.M.'90, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, believes in school choice — but worries what will happen if Trump pushes for it.

“The last thing we want,” Hess says of school choice, “is for the least popular, most maladroit leader in memory to become the advocate for an otherwise popular idea.”

Not everyone agrees with Hess’ assessment of the president, of course, but his concerns do illustrate a basic idea about policymaking that Schifter has borrowed from political scientist John Kingdon and tries to pass on to her students. For any given idea to become a legal reality, the theory goes, policy proposals are only one part of a triangle. Politicians must also effectively prove the existence of the problem, and they must do so at a moment in history when the fix they are proposing is politically possible. For Lyndon Johnson in 1965, the problem was that the nation’s schools were not serving all students equally. The solution was for the federal government to distribute funds in a way that would correct the balance. The political moment was when both Cold War anxieties and newly robust understandings of the 14th Amendment made the changes possible. The result was a new relationship between the federal government and the states on education policy.

Although the Trump administration has outlined some first principles, both its ability to make its case to the American people and the possibilities of this unprecedented political moment remain to be seen.

Brendan Pelsue is a writer whose last piece in Ed. looked at gap year programs .

Illustrations by Simone Massoni

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Equitable Recovery: Addressing Learning Challenges after COVID

Neighborhoods Matter

Road to COVID Recovery

Sorry, we did not find any matching results.

We frequently add data and we're interested in what would be useful to people. If you have a specific recommendation, you can reach us at [email protected] .

We are in the process of adding data at the state and local level. Sign up on our mailing list here to be the first to know when it is available.

Search tips:

• Check your spelling

• Try other search terms

• Use fewer words

How are public schools funded?

Public school funding comes primarily from local and state governments, while the federal government provides about 8% of local school funding.

Updated on Fri, July 21, 2023 by the USAFacts Team

Public schools in the US serve about 49.5 million students from pre-K to 12th grade. But how does it all get funded?

It's primarily a combination of funding from local and state governments, along with a smaller percentage from the federal government. Here's a breakdown.

Where does school funding come from?

In the 2019-2020 school year , 47.5% of funding came from state governments, 44.9% came from local governments, and the federal government provided about 7.6% of school funding.

Federal funding for schools

Most federal funding for public schools comes from the Child Nutrition Act, Title I, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), followed by other programs, according to 2018-19 school year data .

Title I grants

Title I provides funds to school districts with large numbers of low-income students. According to data from 2015-2016 school year, nearly 56,000 schools received money from Title I grants, serving more than 26 million students. About $14.6 billion went toward funds for Title I grants during the 2019-2020 school year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) provides funding to help children with disabilities receive quality special education and related services that are designed to meet their unique needs, according to the Education Department. In 2020–21, 7.5 million students received special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) . Some $14.3 billion in federal funding went toward IDEA in 2022.

Child Nutrition Act

During the 2020 fiscal year, $23.6 billion in federal funds were allocated for child nutrition programs , providing free or reduced lunches to eligible students.

Other federal funding

Federal funds also went towards Head Start programs (supporting children from birth to age 5 in low-income families), magnet schools, gifted and talented programs, Impact Aid (assistance to districts with children residing in areas including Indian lands, military bases, and low-rent housing properties), vocational programs and Indian Education programs.

Get facts first

Unbiased, data-driven insights in your inbox each week

You are signed up for the facts!

State funding for schools

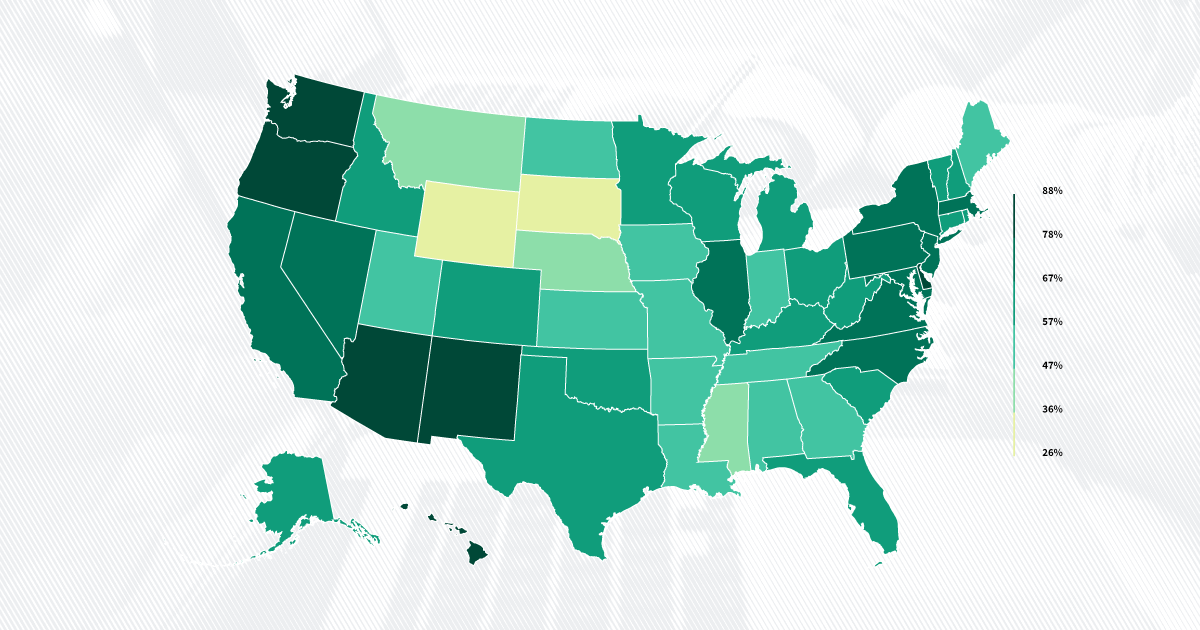

Some states allocate more money for public K-12 schools than others. In five states, two-thirds or more of K-12 public school funding comes from state revenue.

State revenues are raised from a variety of sources , primarily personal and corporate income and retail sales taxes, as well as taxes on tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, and lotteries—depending on the state.

Each state uses a different funding formula to determine how money for K-12 education is raised and how much each school district receives in a given school year. Funding formulas calculate whether school expenditures come from state governments versus local governments, such as counties, cities, or school districts themselves.

In at least 35 states, the state government sets a base level of funding per student that all school districts receive, according to a Congressional Research Service report that summarized various approaches of categorizing states' education funding models.

Local funding for schools

Local school revenue comes from cities, counties, or the school districts themselves. About 81% of local funding for schools comes from property taxes.

Other revenue comes from parents via parent-teacher associations and other groups. Schools also receive some private revenue from tuition, transportation fees, food services, district activities, textbook revenue, and summer school revenue.

Property taxes are a major source of school funding

According to the Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics, property taxes contribute 30% or more of total public school funding in 29 states .

- More than 60% of total public school funding came from property taxes in New Hampshire—the highest of any state.

- On the low end, Vermont had such little funding from property taxes that it rounded to zero. And Hawaii's one school district did not receive any funding from property taxes.

How are charter schools funded?

Public charter schools are funded by state and local governments and may also receive federal funding through Department of Education Charter School Program grants . Charter schools are independently run under an agreement (charter) with the state, district, or another entity. School choice programs offered in some states give parents the option to enroll their kids in charter schools, magnet schools, or opt for home-schooling.

How has school funding changed over time?

Over the past decade, funding provided by local and state governments has increased steadily while federal funding dropped by $30.2 billion. This has resulted in a lower share of school funding from the federal government, dropping from 12.5% in the 2010-11 school year to 7.6% in the 2019-20 school year.

Although federal funding for public schools plays a minor role, it supports programs like Title I, IDEA, and the Child Nutrition Act. As federal contributions have decreased over the past decade, the responsibility for supporting education increasingly falls on local and state entities, highlighting the role of local property taxes and state revenues in funding public education.

Learn more about the state of education in the US , and get the data directly in your inbox by signing up for our email newsletter .

Explore more of USAFacts

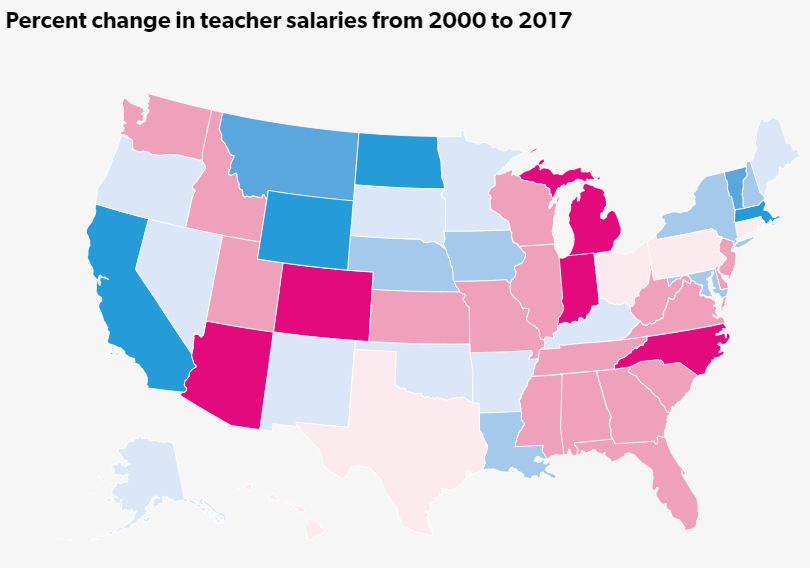

Related articles, in 32 states, teacher salaries have not kept pace with inflation.

How uneven educational outcomes begin, and persist, in the US

65% of households with children report the use of online learning during pandemic

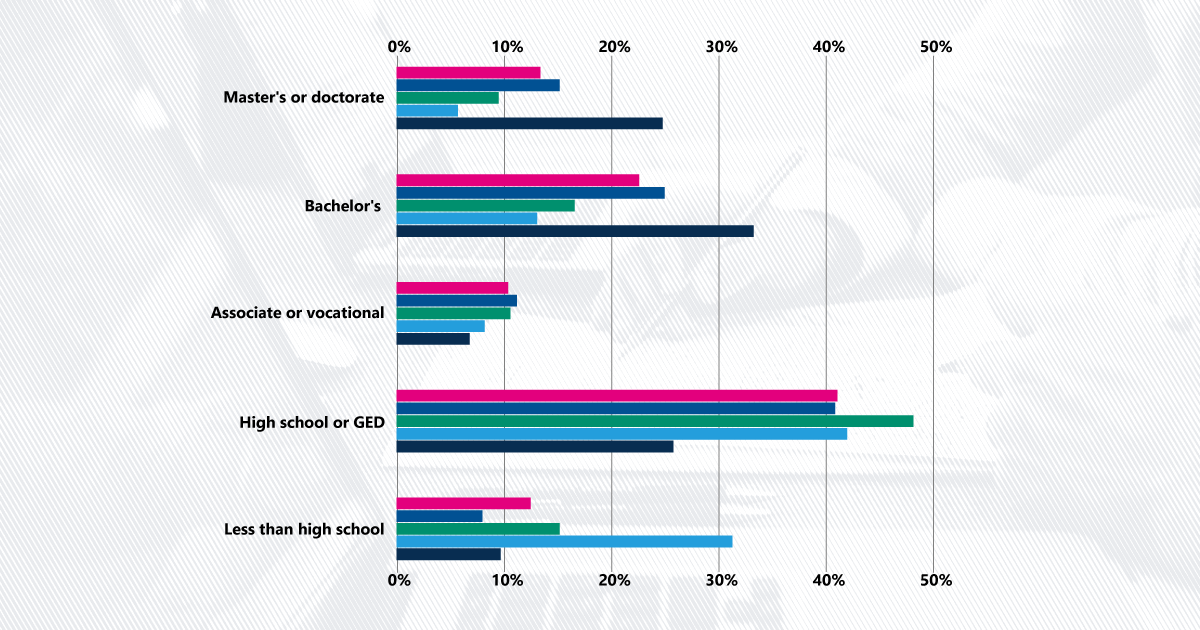

Who are the nation’s 4 million teachers?

Related Data

Public School Staff

6.63 million

High school graduates

3.67 million

National school lunch participation

30.1 million

Data delivered to your inbox

Keep up with the latest data and most popular content.

SIGN UP FOR THE NEWSLETTER

A primer on elementary and secondary education in the United States

Editor’s Note: This report is an excerpt, with minor edits, from Addressing Inequities in the US K-12 Education System , which first appeared in Rebuilding the Pandemic Economy , published by the Aspen Economic Strategy Group in 2021.

This report reviews the basics of the American elementary and secondary education system: Who does what and how do we pay for it? While there are some commonalities across the country, the answers to both questions, it turns out, vary considerably across states. 1

Who does what?

Schools are the institution most visibly and directly responsible for educating students. But many other actors and institutions affect what goes on in schools. Three separate levels of government—local school districts, state governments, and the federal government—are involved in the provision of public education. In addition, non-governmental actors, including teachers’ unions, parent groups, and philanthropists play important roles.

Most 5- to 17-year-old children – about 88%– attend public schools. 2 (Expanding universal schooling to include up to two years of preschool is an active area of discussion which could have far-reaching implications, but we focus on grades K-12 here.) About 9% attend private schools; about a quarter of private school students are in non-sectarian schools, and the remaining three-quarters are about evenly split between Catholic and other religious schools. The remaining 3% of students are homeschooled.

Magnet schools are operated by local school districts but enroll students from across the district; magnet schools often have special curricula—for example, a focus on science or arts—and were sometimes designed specifically to encourage racial integration. Charter schools are publicly funded and operate subject to state regulations; private school regulations and homeschooling requirements are governed by state law and vary across states. Nationally, 6.8% of public school students are enrolled in charter schools; the remainder attend “traditional public schools,” where students are mostly assigned to schools based on their home address and the boundaries school districts draw. Washington, D.C. and Arizona have the highest rates of charter enrollment, with 43 and 19% of their public school students attending charter schools. Several states have little or no charter school enrollment. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly all public schooling took place in person, with about 0.6% of students enrolled in virtual schools.

Local School Districts

Over 13,000 local education agencies (LEAs), also known as school districts, are responsible for running traditional public schools. The size and structure of local school districts, as well as the powers they have and how they operate, depend on the state. Some states have hundreds of districts, and others have dozens. District size is mostly historically determined rather than a reflection of current policy choices. But while districts can rarely “choose” to get smaller or larger, district size implicates important trade-offs . Having many school districts operating in a metropolitan area can enhance incentives for school and district administrators to run schools consistent with the preferences of residents, who can vote out leaders or vote with their feet by leaving the district. On the other hand, fragmentation can lead to more segregation by race and income and less equity in funding, though state laws governing how local districts raise revenue may address the funding issues. Larger districts can benefit from economies of scale as the fixed costs of operating a district are spread over more students and they are better able to operate special programs, but large districts can also be difficult to manage. And even though large districts have the potential to pool resources between more- and less-affluent areas, equity challenges persist as staffing patterns lead to different levels of spending at schools within the same district.

School boards can be elected or appointed, and they generally are responsible for hiring the chief school district administrator, the superintendent. In large districts, superintendent turnover is often cited as a barrier to sustained progress on long term plans, though the causation may run in the other direction: Making progress is difficult, and frustration with reform efforts leads to frequent superintendent departures. School districts take in revenue from local, state, and federal sources, and allocate resources—primarily staff—to schools. The bureaucrats in district “central offices” oversee administrative functions including human resources, curriculum and instruction, and compliance with state and federal requirements. The extent to which districts devolve authority over instructional and organizational decisions to the school level varies both across and within states.

State Governments

The U.S. Constitution reserves power over education for the states. States have delegated authority to finance and run schools to local school districts but remain in charge when it comes to elementary and secondary education. State constitutions contain their own—again, varying—language about the right to education, which has given rise to litigation over the level and distribution of school funding in nearly all states over the past half century. States play a major role in school finance, both by sending aid to local school districts and by determining how local districts are allowed to tax and spend, as discussed further below.

State legislatures and state education agencies also influence education through mechanisms outside the school finance system. For example, states may set requirements for teacher certification and high school graduation, regulate or administer retirement systems, determine the ages of compulsory schooling, decide how charter schools will (or will not) be established and regulated, set home-schooling requirements, establish curricular standards or approve specific instructional materials, choose standardized tests and proficiency standards, set systems for school accountability (subject to federal law), and create (or not) education tax credits or vouchers to direct public funds to private schools. Whether and how states approach these issues—and which functions they delegate to local school districts—varies considerably.

Federal Government

The authority of the federal government to direct schools to take specific actions is weak. Federal laws protect access to education for specific groups of students, including students with disabilities and English language learners. Title IX prohibits sex discrimination in education, and the Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of race. The U.S. Department of Education issues regulations and guidance on K-12 laws and oversees grant distribution and compliance. It also collects and shares data and funds research. The Bureau of Indian Education is housed in the Department of the Interior, not the Department of Education.

The federal government influences elementary and secondary education primarily by providing funding—and through the rules surrounding the use of those funds and the conditions that must be met to receive federal funding. Federal aid is typically allocated according to formulas targeting particular populations. The largest formula-aid federal programs are Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), which provides districts funds to support educational opportunity, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), for special education. Both allocate funding in part based on child poverty rates. State and school district fiscal personnel ensure that districts comply with rules governing how federal funds can be spent and therefore have direct influence on school environments. Since 1965, in addition to specifying how federal funds can be spent, Congress has required states and districts to adopt other policies as a condition of Title I receipt. The policies have changed over time, but most notably include requiring school districts to desegregate, requiring states to adopt test-based accountability systems, and requiring the use of “evidence-based” approaches.

IDEA establishes protections for students with disabilities in addition to providing funding. The law guarantees their right to a free and appropriate public education in the least restrictive setting and sets out requirements for the use of Individualized Educational Programs. Because of these guarantees, IDEA allows students and families to pursue litigation. Federal law prohibits conditioning funding on the use of any specific curriculum. The Obama Administration’s Race to the Top program was also designed to promote specific policy changes—many related to teacher policy—but through a competitive model under which only select states or districts “won” the funds. For the major formula funds, like Title I and IDEA, the assumption (nearly always true) is that states and districts will adopt the policies required to receive federal aid and all will receive funds; in some cases, those policy changes may have more impact than the money itself. The federal government also allocated significant funding to support schools during the Great Recession and during the COVID-19 pandemic through specially created fiscal stabilization or relief funds; federal funding for schools during the COVID crisis was significantly larger than during the Great Recession.

The federal tax code, while perhaps more visible in its influence on higher education, also serves as a K-12 policy lever. The controversial state and local tax deduction, now limited to $10,000, reduces federal tax collections and subsidizes progressive taxation for state and local spending, including for education. As of 2018, 529 plans, which historically allowed tax-preferred savings only for higher education expenses, can also be used for private K-12 expenses.

Non-Governmental Actors

Notable non-governmental actors in elementary and secondary education include teachers’ unions and schools of education, along with parents, philanthropists, vendors, and other advocates.The nation’s three million public school teachers are a powerful political force, affecting more than just teachers’ compensation. For example, provisions of collective bargaining agreements meant to improve teachers working conditions also limit administrator flexibility. Teachers unions are also important political actors; they play an active role in federal, state, and school board elections and advocate for (or, more often, against) a range of policies affecting education. Union strength varies considerably across U.S. states.

Both states and institutions of higher education play important roles in determining who teaches and the preparation they receive. Policies related to teacher certification and preparation requirements, ranging from whether teachers are tested on academic content to which teachers are eligible to supervise student teachers, vary considerably across states. 3 Meanwhile, reviews of teacher training programs reveal many programs do not do a good job incorporating consensus views of research-based best practices in key areas. To date, schools of education have not been the focus of much policy discussion, but they would be critical partners in any changes to how teachers are trained.

Parents play an important role, through a wide range of channels, in determining what happens in schools. Parents choose schools for their children, either implicitly when they choose where to live or explicitly by enrolling in a charter school, private school, participating in a school district choice program, or homeschooling, though these choices are constrained by income, information, and other factors. They may also raise money through Parent Teacher Associations (PTAs) or other foundations—and determine how it is spent. And they advocate for (or against) specific policies, curriculum, or other aspects of schooling through parent organizations, school boards, or other levels of government. Parents often also advocate for their children to receive certain teachers, placements, evaluation, or services; this is particularly true for parents of students with disabilities, who often must make sure their children receive legally required services and accommodations. Though state and federal policymakers sometimes mandate parent engagement , these mechanisms do not necessarily provide meaningful pathways for parental input and are often dominated by white and higher-SES parents .

Philanthropy also has an important influence on education policy, locally and nationally. Not only do funders support individual schools in traditional ways, but they are also increasingly active in influencing federal and state laws. Part of these philanthropic efforts happen through advocacy groups, including civil rights groups, religious groups, and the hard-to-define “education reform” movement. Finally, the many vendors of curriculum, assessment, and “edtech” products and services bring their own lobbying power.

Paying for school

Research on school finance might be better termed school district finance because districts are the jurisdictions generating and receiving revenue, and districts, not schools, are almost always responsible for spending decisions. School districts typically use staffing models to send resources to schools, specifying how many staff positions (full-time equivalents), rather than dollars, each school gets.

Inflation-adjusted, per-pupil revenue to school districts has increased steadily over time and averaged about $15,500 in 2018-19 (total expenditure, which includes both ongoing and capital expenditure, is similar but we focus on revenue because we are interested in the sources of revenue). Per-pupil revenue growth tends to stall or reverse in recessions and has only recently recovered to levels seen prior to the Great Recession (Figure 1). On average, school districts generated about 46% of their revenue locally, with about 80% of that from property taxes; about 47% of revenue came from state governments and about 8% from the federal government. The share of revenue raised locally has declined from about 56% in the early 1960s to 46% today, while the state and federal shares have grown. Local revenue comes from taxes levied by local school districts, but local school districts often do not have complete control over the taxes they levy themselves, and they almost never determine exactly how much they spend because that depends on how much they receive in state and federal aid. State governments may require school districts to levy certain taxes, limit how much local districts are allowed to tax or spend, or they may implicitly or explicitly redistribute some portion of local tax revenue to other districts.

Both the level of spending and distribution of revenue by source vary substantially across states (Figure 2), with New York, the highest-spending state, spending almost $30,000 per pupil, while Idaho, Utah, and Oklahoma each spent under $10,000 per pupil. (Some, but far from all, of this difference is related to higher labor costs in New York.) Similarly, the local share of revenue varies from less than 5% in Hawaii and Vermont to about 60% in New Hampshire and Nebraska. On average, high-poverty states spend less, but there is also considerable variation in spending among states with similar child poverty rates.

Discussions of school funding equity—and considerable legal action—focus on inequality of funding across school districts within the same state . While people often assume districts serving disadvantaged students spend less per pupil than wealthier districts within a state, per-pupil spending and the child poverty rate are nearly always uncorrelated or positively correlated, with higher-poverty districts spending more on average. Typically, disadvantaged districts receive more state and federal funding, offsetting differences in funding from local sources. Meanwhile, considerable inequality exists between states, and poorer states spend less on average. Figure 3 illustrates an example of this dynamic, showing the relationship between district-level per-pupil spending and the child poverty rate in North Carolina (a relatively low-spending state with county- and city-based districts) and Illinois (a higher-spending state with many smaller districts). In North Carolina, higher poverty districts spend more on average; Illinois is one of only a few states in which this relationship is reversed. But this does not mean poor kids get fewer resources in Illinois than in North Carolina. Indeed, nearly all districts in Illinois spend more than most districts in North Carolina, regardless of poverty rate.

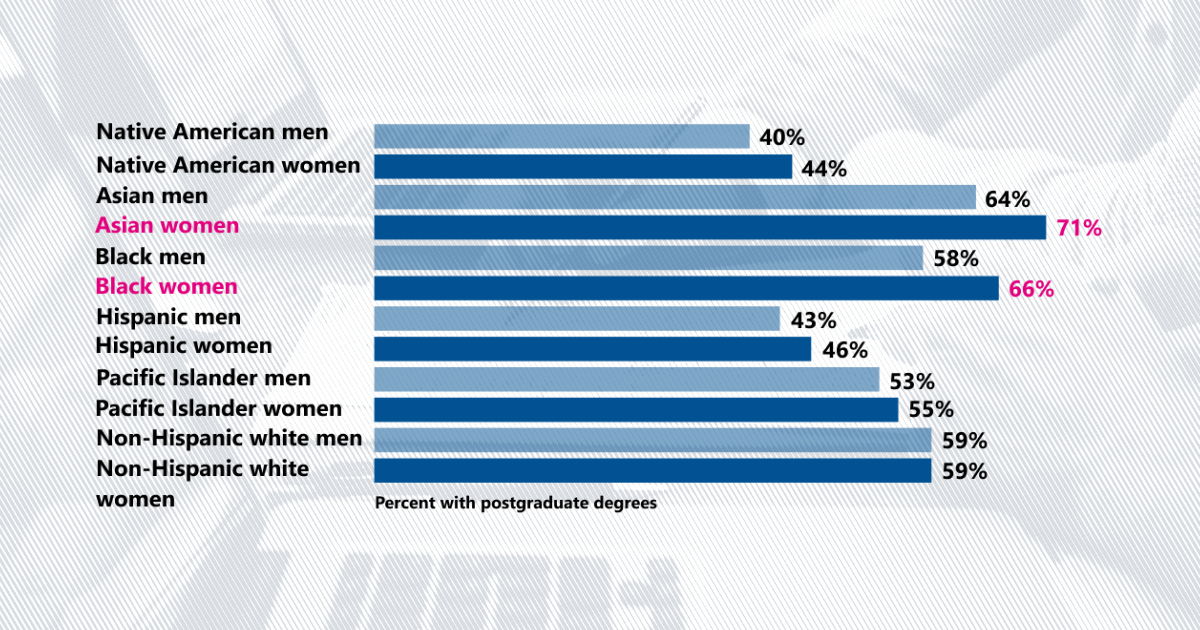

Figure 4 gives a flavor of the wide variation in per-pupil school spending. Nationally, the district at the 10th percentile had per-pupil current expenditure of $8,800, compared to $18,600 at the 90th percentile (for these calculations we focus on current expenditure, which is less volatile year-to-year, rather than revenue). Figure 4 shows that this variation is notably not systematically related to key demographics. For example, on average, poor students attend school in districts that spent $13,023 compared to $13,007 for non-poor students. The average Black student attends school in a district that spent $13,485 per student, compared to $12,918 for Hispanic students and $12,736 for White students. 4 School districts in high-wage areas need to spend more to hire the same staff, but adjusting spending to account for differences in prevailing wages of college graduates (the second set of bars) does not change the picture much.

Does this mean the allocation of spending is fair? Not really. First, to make progress reducing the disparities in outcomes discussed above, schools serving more disadvantaged students will need to spend more on average. Second, these data are measured at the school district level, lumping all schools together. This potentially masks inequality across (as well as within) schools in the same district.

The federal government now requires states to report some spending at the school level; states have only recently released these data. One study using these new data finds that within districts, schools attended by students of color and economically-disadvantaged students tend to have more staff per pupil and to spend more per pupil. These schools also have more novice teachers. How could within-district spending differences systematically correlate with student characteristics, when property taxes and other revenues for the entire district feed into the central budget? Most of what school districts buy is staff, and compensation is largely based on credentials and experience. So schools with less-experienced teachers spend less per pupil than those with more experienced ones, even if they have identical teacher-to-student ratios. Research suggests schools enrolling more economically disadvantaged students, or more students of color, on average have worse working conditions for teachers and experience more teacher turnover. Together, this means that school districts using the same staffing rules for each school—or even allocating more staff to schools serving more economically disadvantaged students—would have different patterns in spending per pupil than staff per pupil.

[1] : For state-specific information, consult state agency websites (e.g., Maryland State Department of Education) for more details. You can find data for all 50 states at the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics , and information on state-specific policies at the Education Commission of the States .

[2] : The numbers in this section are based on the most recent data available in the Digest of Education Statistics, all of which were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

[3] : See the not-for-profit National Council on Teacher Quality for standards and reviews of teacher preparation programs, and descriptions of state teacher preparation policies.

[4] : These statistics may be particularly surprising to people given the widely publicized findings of the EdBuild organization that, “ Nonwhite school districts get $23 billion less than white school districts. ” The EdBuild analysis estimates gaps between districts where at least 75% of students are non-White versus at least 75% of students are White. These two types of districts account for 53% of enrollment nationally. The $23 billion refers to state and local revenue (excluding federal revenue), whereas we focus on current expenditure (though patterns for total expenditure or total revenue are similar).

Disclosures: The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here . The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation .

About the Authors

Sarah reber, joseph a. pechman senior fellow – economic studies, nora gordon, professor – mccourt school of public policy, georgetown university.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

7 Education Federalism: Why It Matters and How the United States Should Restructure It

Kimberly Jenkins Robinson is the Elizabeth D. and Richard A. Merrill Professor of Law at the University of Virginia School of Law and Professor of Education at the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia. She speaks nationally and internationally about educational equity, civil rights, and the federal role in education. Her edited book, A Federal Right to Education: Fundamental Questions for Our Democracy, was published in 2019 and considers the questions raised when considering recognition of a federal right to education in the United States.

- Published: 02 April 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Education federalism in the United States promotes state and local authority over education and a limited federal role. This approach to education federalism often serves as an influential yet underappreciated influence on education law and policy. This chapter explores how education federalism in the United States has evolved over time, its strengths and drawbacks, as well as how it has hindered efforts to advance equal educational opportunity. It argues that to achieve the nation’s education aims, education federalism must be restructured to embrace a more efficacious and efficient allocation of authority of education that embraces the policymaking strengths of each level of government while ensuring that all levels of government aim to achieve equitable access to an excellent education. The chapter proposes how to restructure education federalism to support a partnership between federal, state, and local governments to achieve equitable access to an excellent education. It also explains how this new approach to education federal could guide the United States toward a more impactful reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

Introduction

“ Let us think of education as the means of developing our greatest abilities, because in each of us there is a private hope or dream which, fulfilled, can be translated into benefit for everyone and greater strength for our Nation.” —President John F. Kennedy, Jr. 1

Our nation’s approach to education federalism determines the balance of authority between the state, local, and federal governments in education. Although the federal role in education has grown substantially over the last half century, education federalism in the United States typically promotes primary state and local authority over education and a limited federal role. 2 Maintaining this approach to education federalism serves as a key driver of education law and policy in the United States. It is often underappreciated as one of the fundamental influences on education. Teachers, superintendents, chief state school officers, governors, philanthropists, private and for-profit entities, and the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Education all spring to mind as influencers of education. Yet education federalism shapes the purview of authority for each of these actors and exerts substantial pressure on education reform. 3 Understanding education law and policy requires comprehending education federalism’s influence on education and how the United States could and should reshape education federalism to achieve the aims of education.

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) provides a recent example of the influential nature of education federalism and the limits it places on education law and policy. ESSA protects states and localities as the key drivers of education decisions on everything from the content standards students will be taught, how and when success in learning these standards will be measured, and what interventions should occur when students fall short of meeting these standards. 4 The law greatly curtails the federal role in education because many felt that the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001’s (NCLB’s) dramatic increase in federal influence over education was both far too prescriptive and ill-advised. 5 This recent backlash against federal involvement in education 6 suggests that many have quickly forgotten that a Republican president, George H.W. Bush, ushered in the sizable increase of the federal role and spending in NCLB because federal accountability was needed to insist that states and localities raise expectations, expand opportunities, and effectively serve all students, including disadvantaged students. 7

This chapter begins with a brief overview of how the U.S. approach to education federalism has evolved in the United States and its benefits and drawbacks. It then explains how this approach has served as a roadblock to education reforms that aimed to advance equal educational opportunity. This chapter also presents my proposal for disrupting education federalism and restructuring it in ways that would more successfully support a partnership between state and local governments and the federal government to enable all three levels of government to pursue equitable access to an excellent education for all children. Finally, I provide an example of how this restructured approach to education federalism could be applied to guide reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. Throughout the chapter, I use the phrase “education federalism” to refer to a balance of power over education that emphasizes state and local authority over education and a circumscribed federal role, unless another use is indicated.

What Is Education Federalism and Why Does It Matter?

Historically, the United States has structured education federalism to protect state and local control of education and limit federal influence. 8 The U.S. Constitution does not include education within the purview of federal authority. The Tenth Amendment reserves for state authority any matter that the Constitution does not assign to the federal government. These constitutional foundations for the primacy of state and local authority and a limited federal role over education remain influential in contemporary debates over how education federalism should be structured.

Yet the persistent emphasis on a limited federal role in education often overlooks constitutional history that reveals that the Fourteenth Amendment obligates Congress “to ensure that all children have adequate educational opportunity for equal citizenship” and that Congress can wield tremendous influence over education through the Spending Clause. 9 History also demonstrates that federal leaders have long understood the importance of support for education for the prosperity of the nation and the endurance of our democracy. Although federal involvement in education was relatively limited until the mid-twentieth century, it is important for debates about the proper federal role in education to acknowledge that federal involvement in education dates back to the late eighteenth century when the Land Ordinance of 1785 required a portion of land in each township to be set aside for public schools. 10 In addition, when southern states were readmitted to the Union after the Civil War, Congress required the states to develop nonsectarian, free public schools. 11 The federal government has been and will remain influential in education even when its role has been circumscribed. This reality raises the question that this chapter examines: how should the balance of governmental power over education be arranged to accomplish the goals of education?

The balance of state, local, and federal power over education has been shifting for well over half a century in new and often unexpected ways from its decentralized origins. Three substantial evolutions have occurred. First, the federal role in education has greatly expanded from its initial role. Brown v. Board of Education and its progeny substantially expanded federal influence over education when the U.S. Supreme Court proclaimed segregated schools unconstitutional. 12 Congress continued to expand the federal role in education when it passed several laws that advanced equal educational opportunity in public schools, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. 13

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act has been a particularly powerful vehicle for increasing federal authority over education. It began as limited federal support for the needs of disadvantaged students to advance equal opportunity and civil rights. 14 Through such reauthorizations as the Improving America’s Schools Act of 1994 and NCLB, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act expanded its goals to include ensuring that all children receive high-quality educational opportunities and are taught and tested based upon challenging academic standards. 15 ESSA continues this expanded focus on all children while it also seeks to aid the most disadvantaged children. 16 Today, as it has for decades, the federal government influences education from the state capital to the classroom. 17

Second, state control of education has increased significantly since the time when local townships and schools exercised primary authority over schools in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. 18 Nationally, for the 2015–2016 school year, states provided the greatest share of funding for schools at 47 percent, local sources provided 45 percent, and the federal government provided 8 percent. 19 In contrast, for the 1919–1920 school year, states provided 17 percent of funding, local sources provided 83 percent of funding, and the federal government provided less than 1 percent of funding. 20 As states have contributed a greater share of education funding, they also have increased their authority and influence over education. 21 For example, states determine the content standards for each grade level and the tests used to assess student knowledge of the standards, which has resulted in greater state power over the curriculum. 22