Art Theory for a Global Pluralistic Age pp 39–63 Cite as

The Effects of Globalization on Art and Aesthetics

- Steven Félix-Jäger 2

- First Online: 03 December 2019

459 Accesses

This chapter traces the ways globalization caused art around the world to shift toward inclusion. Both the West and the majority world followed unique paths toward the same globalized reality, creating a vast cross-cultural dialogue that envelops every aspect of culture, including art. In today’s world of art, globalization is not a one-way street where Western artists indoctrinate the total discourse on art. Rather, majority world artists and markets are also feeding into and changing the global discourse. The rise of global art biennials, and the sociological concept of “reverse flow,” perpetuates a plurality of critical voices. With a new emphasis on plurality, theories of art fail if they are based on particularized intrinsic qualities. As such, a glocal theory of art must find extrinsic qualities for classifying and evaluating art.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Noël Carroll, “Art and Globalization: Then and Now,” in Susan Feagin, Ed., Global Theories of the Arts and Aesthetics (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 132.

Carroll, “Art and Globalization: Then and Now,” 132.

Carroll, “Art and Globalization: Then and Now,” 136.

For instance, Caroline Jones says that the transnational suggests a moving beyond a singular world picture and has entered into a pluralistic era with several coexisting world pictures. Caroline Jones, The Global Work of Art: World Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of Experience (Chicago: the University of Chicago Press, 2016), 159.

Myers, Engaging Globalization , 37.

Manfred Steger, The Rise of the Global Imaginary: Political Ideologies from the French Revolution to the Global War on Terror (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 10–11.

Myers, Engaging Globalization , 38.

Tommaso Durante, “On the Global Imaginary: Visualizing and Interpreting Aesthetics of Global Change in Melbourne, Australia and Shanghai, People’s Republic of China,” The Global Studies Journal , Vol. 8, No. 5 (2015), 19.

Caroline Jones, “Globalism/Globalization,” in James Elkins, Zhivka Valiavicharska, and Alice Kim, Eds., Art and Globalization (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 130.

Jones, “Globalism/Globalization,” 134.

Akshaya Kumar “The Aesthetics of Pirate Modernities: Bhojpuri Cinema and the Underclasses,” in Raminder Kaur and Parul Dave-Mukherji, Eds., Arts and Aesthetics in a Globalizing World (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), 1.

Myers, Engaging Globalization , 69.

Myers, Engaging Globalization , 74–76.

Myers, Engaging Globalization , 79.

Gregory Clark and Robert Feenstra, “Technology in the Great Divergence,” in Michael Bordo, Alan Taylor, and Jeffrey Williamson, Globalization in Historical Perspective (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2003), 298.

Nina Möntmann, “Narratives of Belonging: On the Relation of the Art Institution and the Changing Nation-State,” in James Elkins, Zhivka Valiavicharska, and Alice Kim, Eds., Art and Globalization (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 162.

Walter Mignolo, “Museums in the Colonial Horizon of Modernity: Fred Wilson’s Mining of the Museum (1992),” in Jonathan Harris, Ed., Globalization and Contemporary Art (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 71.

Möntmann, “Narratives of Belonging,” 161.

Myers, Engaging Globalization , 89.

Myers, Engaging Globalization , 98.

Myers, Engaging Globalization , 100.

Myers, Engaging Globalization , 101.

Iftikhar Dadi, “Globalization and Transnational Modernism,” in James Elkins, Zhivka Valiavicharska, and Alice Kim, Eds., Art and Globalization (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 183–184.

Dadi, “Globalization and Transnational Modernism,” 186–187.

Caroline Jones, The Global Work of Art: World’s Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of Experience (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 3.

Jones, The Global Work of Art , 3.

Claudette Lauzon, “Reluctant Nomads: Biennial Culture and Its Discontents,” RACAR, Vol. 36, No. 2 (2011), 16.

Jerry Saltz, “Biennial Culture,” Artnet, http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/saltz/saltz7-2-07.asp (accessed June 15, 2018).

Charles Green and Anthony Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta: The Exhibition that Created Contemporary Art (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016), 6.

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 276.

Caroline Jones, The Global Work of Art: World’s Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of Experience (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 83.

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 49.

Although a proper noun, the term is stylized with the lower case “d” in “documenta 5.”

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 20.

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 33.

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 41.

Jones, The Global Work of Art , 114.

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 81–82.

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 113.

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 255.

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 150.

Jones, The Global Work of Art , 93.

Jones, The Global Work of Art , 94.

Green and Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta, 260.

Jones, The Global Work of Art , 198.

David Craven, “Institutionalized Globalization, Contemporary Art, and the Corporate Gulag in Chile,” in Jonathan Harris, Ed., Globalization and Contemporary Art (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 492.

Kelly Richman-Abdou, “7 Most Important Art Fairs People Travel Across the World to See,” My Modern Met (2018) https://mymodernmet.com/art-fairs/ (accessed January 12, 2019).

Alain Quemin, “International Contemporary Art Fairs in a ‘Globalized’ Art Market,” European Societies , Vol. 15, No. 2 (2013), 170.

Christine Morgner, “The Art Fair as Network,” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, Vol. 44 (2014), 38.

Morgner, “The Art Fair as Network,” 43.

Quemin, “International Contemporary Art Fairs in a ‘Globalized’ Art Market,” 174.

Quemin, “International Contemporary Art Fairs in a ‘Globalized’ Art Market,” 172.

Quemin, “International Contemporary Art Fairs in a ‘Globalized’ Art Market,” 170–171.

I would add the philosophy of art to this list.

James Elkins, “Introduction: Art History as a Global Discipline,” in James Elkins, Ed., Is Art History Global (London: Routledge, 2007), 16–20.

Blake Gopnik, “The Oxymoron of Global Art,” in James Elkins, Zhivka Valiavicharska, and Alice Kim, Eds., Art and Globalization (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 146.

Gopnik, “The Oxymoron of Global Art,” 146.

Melvin DeFleur, Mass Communication Theories: Explaining Origins, Processes, and Effects (London: Routledge, 2016), 301.

“Indestructible Object,” MoMA Learning, https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/man-ray-indestructible-object-1964-replica-of-1923-original (accessed June 14, 2018).

“About Survival Research Labs,” Survival Research Laboratories, http://www.srl.org/about.html (accessed January 12, 2019).

“Cai Guo-Qiang: The Artist Who ‘Paints’ With Explosives,” CNN Style, https://www.cnn.com/style/article/cai-guo-qiang-explosive-art/index.html (accessed June 14, 2018).

Jonathan Jones, “Who’s the Vandal: Ai Weiwei or the Man Who Smashed His Han Urn?” The Guardian (2014), https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2014/feb/18/ai-weiwei-han-urn-smash-miami-art (accessed June 14, 2018).

Jones, The Global Work of Art , 152.

Jones, The Global Work of Art , 153–154.

Victor Roudometof, Glocalization: A Critical Introduction (London: Routledge, 2016) , 124.

James Elkins, Section 8 of the Seminars, in James Elkins, Zhivka Valiavicharska, and Alice Kim, Eds., Art and Globalization (University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 2010), 98–99.

For a discussion about other options beyond the global or glocal, see Roudometof, Glocalization (London: Routledge, 2016). Roudometof discusses other terms such as “hybridity,” “creole,” and “mestizaje,” stating that these are sometimes used to discuss contemporary art as well, but they have their limitations. Hybridity refers to the mixing of two streams, but does not account for the origin of the streams (14). Creole and Mestizaje discuss the mixing of a native group with immigrant groups. These are also too limiting since most people experience the global from the vantage point of a dominant, and not mixed, heritage.

Roudometof, Glocalization , 2.

“Glocal,” Oxford Dictionary, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/glocal (accessed June 18, 2018).

Thierry de Duve, “The Glocal and the Singuniversal: Reflection on Art and Culture in the Global World,” Third Text , Vol. 21, No. 6 (2007) 683.

de Duve, “The Glocal and the Singuniversal,” 683.

Roudometof, Glocalization , 49.

Roudometof, Glocalization , 64.

Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer,” in George Marcus and Fred Myers, Eds., The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 304.

Nermin Saybasili, “Gesturing No(w)here,” in Jonathan Harris, Ed., Globalization and Contemporary Art (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 410.

This idea will be discussed in greater detail in the next chapter.

Roudometof, Glocalization , 76.

Kathleen Marie Higgins, “Global Aesthetics – What Can We Do?” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism , Vol. 75, No. 4 (2017), 339.

Additionally, Higgins argues that the very term “global aesthetics” is problematic. The fact that aesthetics is modified with a qualifier (global) implies that a “global aesthetics” is not an aesthetics proper (340). Since aesthetics as a field of particular philosophical inquiry arose in the West, Western aesthetics has long been equated with aesthetics proper. Qualifying the more particular sense of the term to broaden its semantic range seems backward, however, and ignores the fact that cultures around the world have offered some sort of perceived or construed insight into aesthetical matters. But, as James Elkins points out, the West has indeed established the parameters of the field of aesthetics; hence this odd reversal.

Higgins, “Global Aesthetics,” 342.

Higgins, “Global Aesthetics,” 344.

Higgins, “Global Aesthetics,” 344–345.

This notion will be fleshed out in Chaps. 5 and 6 .

Raminder Kaur and Parul Dave-Mukherji, “Introduction,” in Raminder Kaur and Parul Dave-Mukherji, Eds., Arts and Aesthetics in a Globalizing World (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), 1.

The “ethnographic turn in art” was an idea initially espoused by Hal Foster in his 1995 essay, “The Artist as Ethnographer.” Foster claims that the subject of art “is now the cultural and/or ethnic other in whose name the artist often struggles” (302). Thus artists seek to uncover identity within and outside of local and immanent orientations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Assistant Professor and Chair of the Worship Arts and Media program, Life Pacific University, San Dimas, CA, USA

Steven Félix-Jäger

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Steven Félix-Jäger .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Félix-Jäger, S. (2020). The Effects of Globalization on Art and Aesthetics. In: Art Theory for a Global Pluralistic Age. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29706-0_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29706-0_3

Published : 03 December 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-29705-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-29706-0

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Student Policies

- Canvas Login

- Careers Portal

- Alumni Benefits

- Career Services

Flows and Counterflows: Globalisation in Contemporary Art

Here are the first few paragraphs of the second chapter in Marcus Verhagen’s new book, Flows and Counterflows; Globalisation in Contemporary Art . The chapter looks at the efforts of artists to engage with the tourism industry and to use it as a prism for the examination of globalisation and its effects.

On Artists and Other Tourists

What theoretical and practical affiliations might an artist choose to have when working far from his or her home? This is a topical question: after all, many artists today travel constantly, to take up residencies, to study and teach, to carry out research, to participate in shows and biennials. And in works grounded in their travels, they are bound to reflect on the movements of other travellers. Pierre Huyghe has taken on the role of the explorer, Barthélémy Toguo has performed the part of the illegal migrant, Emily Jacir has played the visitor and go-between, other artists have aligned themselves with globetrotting businessmen, ethnographers, refugees, tour guides, and translators. And some have identified their movements with the travels of the tourist. On the face of it, this is an obvious gambit. In using taxis, cafés, hotels, Wi-Fi connections, and other amenities, travelling artists are in any case shadowing the tourist. So it comes as little surprise that artists have alluded to the cultural underpinnings, infrastructural arrangements, and paraphernalia of tourism while elaborating on their own movements. Maurizio Cattelan acted as a tour operator when he built a replica of the iconic Hollywood sign above a landfill site in Sicily and then flew a group of collectors, curators, and critics over from the Venice Biennale to see it, his work highlighting the rise in art tourism while at the same time casting the tourist as a wide-eyed consumer of globally distributed fantasies ( Hollywood , 2001). Simon Starling crossed the Tabernas Desert, in Spain, on a fuel cell–powered bicycle and then used the water produced by the engine to paint an image of a cactus that is native to the region ( Tabernas Desert Run , 2004). Hans-Peter Feldmann has displayed his collection of postcards of the Eiffel Tower, drawing out the conventions of postcard photography while commenting on the transformation of the structure into a cultural fetish ( Untitled (Eiffel Tower) , 1990). Din Q. Lê has ironically suggested that tourism can bring post-conflict reconciliation in travel posters featuring sights in Vietnam with captions like “Come back to Vietnam for closure!” ( Not Over Us , 2004). All of these projects were on display in “Universal Experience: Art, Life, and the Tourist’s Eye,” a sprawling show put on in 2005 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago by the curator Francesco Bonami, who set out to explore the parallels between museums and (other) tourist destinations, between artworks and sights.

To underline the affinity of the travelling artist with the tourist, as Feldman, Bonami, and others have done, is to recognise that the artist often follows in the footsteps of the tourist as he or she moves between nodes in a now-global art network. But it would be wrong to understand efforts to couple the travels of the artist and tourist as uninflected affirmations of commonality—they are, on the contrary, charged gestures. Most of us are tourists at one point or another and yet our attitudes to tourism are often uncertain or dismissive. Even when our experiences of travel are richly rewarding we may view the structures of tourism—the guidebooks, the restaurants with “tourist menus,” the designated attractions, tourist trails, photo opportunities, and so forth—with misgiving. Certainly, many of the works in “Universal Experience,” including those by Cattelan and Lê, were premised on a sceptical appraisal of tourism. So what is to be gained from an association with the tourist? More specifically, what can artworks tell us about the processes of globalisation when they picture those processes from the perspective of the tourist?

“Tourism is the march of stupidity.” So wrote Don DeLillo in 1982, starkly expressing a view that has been put forward many times, before and since. The bumbling tourist has long been a staple of comic fiction, doing duty, for instance, in Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad (1869), in Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog) (1889), and more recently in the travelogues of Redmond O’Hanlon. The crowd of tourists proceeding mindlessly from sight to sight is another common literary image, one that is rehearsed in Raymond Queneau’s Zazie dans le métro (1959) when, at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, Zazie’s uncle is adopted by a group of tourists who mistake him for a guide and then follow him, open-mouthed and uncomprehending, across Paris. The same view of tourism is occasionally expressed in an openly discriminatory key, American tourists coming in for particularly harsh treatment, as they do, for instance, in Nicolas Bouvier’s Chronique Japonaise (1975) when the author describes “three mature American women, solidly kitted out in hats and corsets and equipped with cameras—the kind that can take in a dozen temples and one or two imperial residencies in a day without even feeling bloated.” The tourist who expresses contempt for other visitors on the mistaken understanding that he or she has somehow risen above them is another familiar comic figure, appearing in a range of novels from E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View (1908) to Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station (2011). Tourists are routinely compared to sheep, geese, pigeons, and flies—they don’t walk or gather, they “flock” and they “swarm”—and their appearance in a given location is regularly described as an irruption or an invasion. They are also often and unfavourably compared with other travellers, as they are, for instance, in John Buchan’s thriller The Three Hostages (1924) when a hunter speaks of tourists as “blatant and foolish and abundantly discourteous,” unlike mountaineers, who get on with their climbing quietly, without frightening the deer away. This literary critique of tourism has received academic sanction in the work of the conservative historian Daniel J. Boorstin, who describes the experiences of the modern tourist as superficial and inauthentic, contrasting him or her with the adventurous traveller of earlier times. And this critique has a certain currency in the art world. The Gervasuti Foundation in Venice, for instance, put out a magazine advertisement bearing the caption, “Tourists Not Allowed!!! Real Travellers and Native Venetians Only.”

Contemporary artists have also disparaged the tourist. The photographer Martin Parr has made a career of it, picturing groups of travellers as they follow guides, buy souvenirs, and take pictures of one another in various locations around the world. Often sunburnt and inappropriately dressed, his tourists rarely seem to be enjoying themselves; more often than not they look lost or harassed. Olaf Breuning adopts a more corrosive comedic tone in his videos Home (2004) and Home II (2007), which follow the travels of an inanely enthusiastic young American, played by Brian Kerstetter, who takes part in a tribal dance in Papua New Guinea, distributes bananas in a market in Ghana, and parades with men and women wearing Pokemon masks in Tokyo. Watching or intruding on local events, including many that are plainly put on for the benefit of visitors, Breuning’s tourist is a brash and uninformed presence. Wherever he goes, he is keen to immerse himself in local society but his understanding of it is largely conditioned by popular entertainment and travel guides and his encounters are, as a result, painfully one-sided. “Look at this,” he intones as he surveys a Papuan village in Home II, “it looks just like a remake of a Disney film—it’s that real, I feel I want to go up and touch it.” The tourist makes a handy buffoon and plainly appeals to satirists like Parr and Breuning, who follow Boorstin in picturing the tourist’s experience not as an open engagement with unfamiliar places and communities but as a closed loop of media-derived expectations and stage-managed encounters.

In the remainder of this chapter, Verhagen argues that although the tourist is not at first sight a promising metaphorical vehicle for reflections on cross-border contact, some artists have adopted the tourist’s perspective to great effect, offering startling insights on travel and global exchange despite the ridicule that attaches to that perspective—and in some of the more probing works precisely because of it.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

29 Art and the Cultural Transmission of Globalization

School of Art, RMIT University

- Published: 11 December 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter assesses how from early modernity to the present day, art has been a significant agent in the cultural transmission of globalization. It is a cultural legacy, however, that continues to be divided by a deep sense of ambivalence toward the question of how social imaginaries are delimited by the ubiquitous processes of global capital. The field of contemporary art is often entirely complicit with a culture of manufactured exclusivity and large profits, yet it also has its critical edge that has shown how the glossy allure of transnational capital obscures visions of other possible, less inequitable worlds. Other possible worlds have also appeared in art in a recent turn to the great, circulatory systems of the oceans as both the historical conduits of globalization and the channels through which we might envisage what kind of global imaginary will prevail in response to environmental crisis.

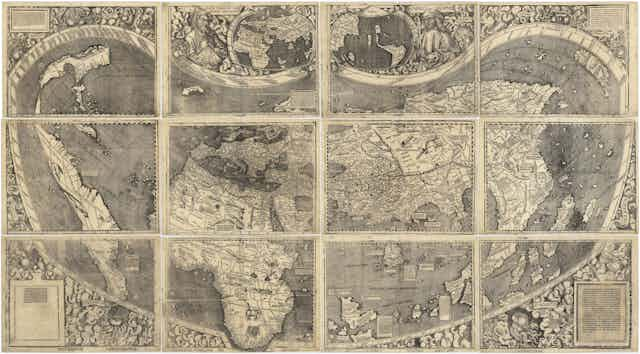

There is no precise historical juncture that can be identified as the point when globalization began to influence the visual arts. The term globalization itself only came into common usage by the late twentieth century, although its history as a process of sociopolitical transformation is, of course, centuries old ( James and Steger 2014 ). Cultural responses to this process also have a long history with complex geopolitical origins that no doubt could be traced back along ancient migratory trade routes such as the Silk Road. In Europe, the cultural engagement in unfolding globalization was greatly extended by maritime circumnavigations of the world from the sixteenth century, when notions of a vast New World began to shape how people in young nation-states recalibrated the contours of their “imagined” communities ( Anderson 1991 ). Hence, the imagery of the globe—of distant lands, exotic islands, or brave “new” worlds—combined with various imperialist tropes were commonplace in late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century art, literature, and letters. Not least in Anglophone culture, in which they often appeared in the works of major poets such as Shakespeare, Donne, Marvell, or Milton (M. Frank, Goldberg, and Newman 2016 ; Lim 1998 ; Mentz 2015 ). Shakespeare wrote from England of the shimmering new global horizons of the seventeenth century:

O, wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, That has such people in ‘t! — The Tempest (1611)

From the outset, however, early modern concepts of the global were tempered by the context of emergent nationalism and a robust colonial discourse imbued with world-destroying implications for subaltern peoples and unforeseen ecological consequences ( Crosby 2003 ; Grove 1997 ). And by the twentieth century in England, Aldous Huxley’s futuristic vision of the price of global modernity was much less sanguine than those of earlier writers:

“What you need,” the Savage went on, “is something with tears for a change. Nothing costs enough here.” — Brave New World (1932)

Cultural concepts of the global were also shaped by the deep shift in Western economies beginning in early modernity and now remaining within what Peter Sloterdijk (2014) refers to as the “world interior of capital” It is important to acknowledge this function of art as a “soft” agent of the extensive channels of international capital, a role it continues to occupy today. Yet this has never been its sole function because, paradoxically, art also has the capacity, as Franz Kafka (1904/1977) noted, to act “like an axe, to break up the frozen sea inside us.” And it this transformative capacity of art that offers counternarratives to what has now been conceived as an advanced form of global socioeconomic Empire ( Hardt and Negri 2000 ). As material culture, art is generally less capable of avoiding everyday contingencies than are poetry and philosophy, for example, yet since the reception of art is not based primarily on either language or literacy, this same materiality and the persuasive power of images can be powerful conduits for shaping transnational social imaginaries.

The concept of the social imaginary has gained considerable critical traction in the humanities ( Appadurai 1996 ; Castoriadis 1987/1998 ; Connery 1996 ; James 2015 ; Taylor 2004 ), and the concept of a global imaginary is also gaining momentum (C. Frank 2010 ; Steger 2008 ). And while a unilateral social image of the global is clearly inconceivable in a highly contested geopolitical field of intensifying inequalities, the struggle to visualize a global imaginary has become a consistent theme of contemporary visual art. This aesthetic objective to visualize globalizing processes draws largely on a late twentieth-century cultural turn toward what George Modelski (2008: 11) called connectivism, in which globalization is viewed primarily as a condition of interdependence. This is particularly the case with themes of social justice and global ecological change in contemporary art, as discussed in greater detail later, but it also applies to the openness and connectivity of the global art markets that artists must negotiate. The connectivist approach to globalization, moreover, should be distinguished from an institutional approach that in the case of art applies to the persuasive power of cultural institutions, now commonly referred to as the culture industry, that effectively facilitate global art markets. Modelski observed,

Both connectivity and openness are the product of a set of organizational and institutional arrangements. They derive from the organizations that originate and manage these flows; the regimes that facilitate and govern them; the matrices of mutual trust that sustain them; and the systems of knowledge that guide them. (p. 12)

If relations between the interior and exterior worlds of global capital are deeply contested, the same applies to the field referred to in developed countries as “contemporary art,” produced by the “creative class” as an essential attribute of financially successful cities ( Florida 2005 ). It is a field of cultural production disseminated by galleries and national biennales 1 and then endorsed by museum collections, art dealers, and private collectors. Yet it is also a field of critical discourse and social critique. Hence, the term “contemporary art” represents a frequently conflicted domain of social consensus confirming the way the world recognizes its most recent cultural self-images and that has, moreover, included many attempts to incorporate art from the “outside” into the interior of late modern culture.

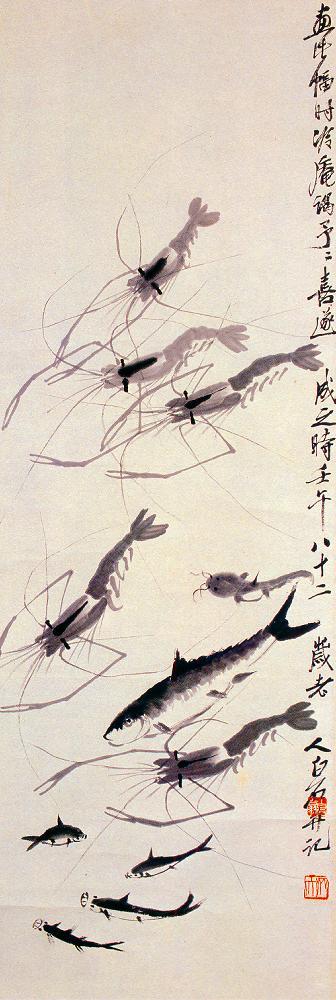

Sloterdijk (2014; 265) identifies the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London as a turning point when the world was “transfigured by luxury and cosmopolitanism” from the far reaches of empire. Yet European maritime expansion had ensured that London’s Crystal Palace was anything but “an agora or a trade fair beneath an open sky, but rather a hothouse that has drawn inwards everything that was once on the outside” (p. 12). In the field of contemporary art, there are comparable problems in how the global mainstream appropriates what it perceives as marginal. This is not just a recent problem; there are many well-known examples of cultural appropriation in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art, such as the use of Japanese or Polynesian art by the post-impressionists or the use of African tribal art by the cubists. Such examples were facilitated, on the one hand, by the rise in the market for Japanese prints and, on the other, by the establishment of the major European ethnographic museums from the 1870s (followed by the first Venice Biennale of 1895). Such examples are often regarded as colonizing gestures toward “primitivism” despite the fact that the artists themselves viewed the works they adapted as sophisticated and saw plagiarizing them as a form of admiration.

In the current discussion, however, rather than engaging in an ethnographic account of the diversity of “outsider” art, my focus is on art that can be described as late modern, which is to say, as art originating in a system of largely Western aesthetic values that, by default, are clearly located within the field of global capital. The fact that such art is no longer exclusively Western has become clearer during the past two decades by the global focus on contemporary Asian art and, more recently, on art from the global war zone of the Middle East. As, for example, the huge growth in the Western market for Chinese art attests, recent Asian art is as enmeshed in the world interior of capital as the European or American art that is more closely aligned with Western traditions. Notwithstanding claims for a new cultural internationalism, however, as Lotte Philipsen (2010; 80–83) has noted, the formal media of non-Western contemporary art has a conceptual framework that is essentially a product of Western processes of modernity. This is not to say that this global art of the contemporary condition does not have its own pluralities, dissensions, or forms of immanent critique but, rather, that it is delimited by its place inside a Western paradigm and exclusive cultural regime where the pressures of the art market mitigate against the agency of art as a form of social critique.

This global art market originated in seventeenth-century Holland, as distinct from other coeval colonial states such as Catholic Spain, Portugal, or France, where art patronage came mainly from the church and court, and England, where acquiring artworks was still largely a privilege of the court and aristocracy. Whereas in the Netherlands by the age of colonial expansion, there was a thriving middle-class art market for which Dutch artists produced large numbers of paintings (Montiaz 1989). 2 These works often referenced the effects of early globalization, to which I turn briefly before discussing art in the transdisciplinary field, where it has become a significant agent in the transmission of cultural globalization.

An early form of global capitalism first emerged in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when European nation-states competed for imperial supremacy of the oceans. Although long before the era of mass consumption, Dutch art of this period effectively redefined the “cultural biography” of objects as luxury commodities ( Kopytoff 1986 ), yet it also had the capacity to reveal their less stable meanings as objects of desire.

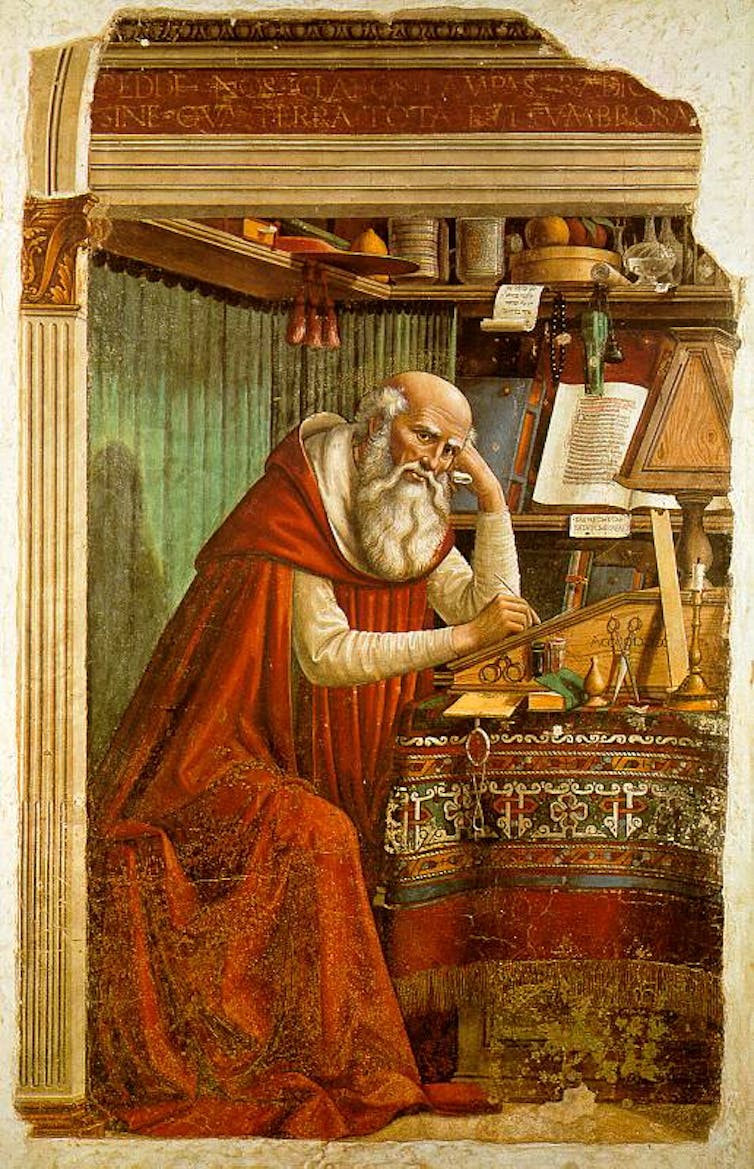

There is, for example, a detectable, if inchoate sense of tension in the imagery of maps and geographers’ globes featured in many seventeenth-century still life or genre pictures. These works were produced at a time when the Western imagination was still shaped by theocentric ontologies and was turning only gradually toward the new economic logic of modernity. In Dutch paintings of this time, the cartographic aim to record with precision the outlines of new lands was at first moderated by attempts to anchor new territories in more familiar traditions by framing them with personifications of the natural elements, biblical narratives, or mythological figures. As the art historian Svetlana Alpers (1983: 122) has observed, however, Dutch map makers were known as “world describers,” a term that she also aptly ascribes to Dutch painters with their heightened skill in carefully depicting the material details of everyday life. Although this “mapping impulse” of Dutch art, as Alpers calls it, certainly shaped new forms of secular landscape painting, it also inclined artists toward achieving greater ethnographic accuracy, where in maps of Africa or South America, for example, continental coastlines were flanked by careful representations of indigenous peoples (although this certainly did not extend to African slaves shipped to sugar plantations in Dutch Brazil).

The art of the new Dutch Republic also referred to geographers’ globes, often rendered as objects as easily grasped as any of the other luxury items on a desk or table. Yet such worlds were also defined by the vast new horizons offered by early telescopes and by the new microscopes that revealed previously unknown dimensions of the physical world. This new lens technology complemented traditional juxtapositions of scale between near and far, small and large, that, as Alpers (1983) acknowledges, had long occupied the artists of Northern Europe. Lenses were also adapted by Dutch and Flemish artists to achieve greater refinement in painted details such as reflections in glass or metal. Hence, as this golden age of Dutch art brought greater visual acuity and focus to a European imaginary reshaped by global colonialism, it also drew on technological advances that offered new lines of enquiry into other kinds of worlds.

Of course, the maps and globes featured in Dutch art were also tools of global mercantile expansion. Companies such as the Dutch VOC (United East India Company, 1602), West India Company (1621), or the British East India Company (1600) were the first of many later multinational companies, including HSBC and BP in London and the Dutch-based ING and Shell. In the seventeenth century, early multinational corporations were new gateways for the trade of luxury goods shipped from afar to Europe. This was a naval trade greatly enabled by technological advances such as the magnetic compass, paper, and gunpowder, which were all invented by the Chinese ( Brook 2008 : 19). The Low Countries in particular were important channels for the trade in material culture (Rittersma 2010), not least in cosmopolitan cities such as Antwerp or in the bustling city of Amsterdam, where in Braudel’s (1984) account,

Everything was crammed together, concentrated: the ships in the harbor, wedged as tight as herrings in a case, the lighters plying up and down the canals, the merchants who thronged to the Bourse, and the goods that piled up in warehouses only to pour out of them. (p. 236)

Antwerp, Amsterdam, and other Dutch cities such as Delft were also centers for the production and trade of paintings with mainly secular subjects, such as still life, landscapes, genre pictures, and portraits. Dutch bourgeois preferences for paintings typically showed “little of colonial working life, concentrating rather on colonial benefits to trade, art and science” ( Westermann, 1996 : 114) while conveying a palpable sense of confidence in national prosperity. The popular genre of still life especially provided a quiet retreat of sorts from the busy pace and noise of the city while also conveying allusions to global horizons: where imported consumer goods such as exotic fruits and foreign flowers were placed beside Pacific Ocean nautilus shells fashioned as wine goblets, or next to pipes for American tobacco and Chinese export porcelain.

In Dutch art of the secular baroque, such imperial luxury goods are typically depicted with skillful verisimilitude, responding to the sumptuous effects of color and light arrayed across domestic objects in ways that suggest a celebration of new forms of consumption. Yet these pictures also suggest an inchoate sense of tension in the way flowers, fruit, or glassware were so often combined with the canonical imagery of still life as memento mori , where skulls, hourglasses, or flickering candle flames signified the vanity of human endeavors. Such references imbued these pictures with a certain ambiguity about the accumulation of worldly wealth that, if not derived from an ambivalence about globalization as such, suggests an unease with the emergence of capital as its driving force that, as discussed later, remains a persistent theme in contemporary art. The historian Simon Schama wrote of dual value systems underpinning seventeenth-century Dutch culture, in which the one “embraced money; power; authority; the gratification of appetite” while the other “invoked austerity; piety; frugality; parsimony; sobriety; the vanity of worldly success; the exclusive community of sacred congregation; the abhorrent” ( Schama 1979 : 113)—a tension he later went on to describe as an “embarrassment of riches” ( Schama 1987 ).

Schama’s account is certainly plausible, especially in light of Weber’s (1905/1965) famous essay on the role of Calvinist salvation anxiety in the spirit of capitalism. Yet, on the other hand, an iconography that juxtaposes new forms of wealth and excess with mortality and decay may also plausibly indicate the nascent signs of a more secular and immanent form of critique. In the context of a new republic recently released from the heavy yoke of Spanish occupation, the experience of a colonization was not foreign to the Dutch people. This obviously did little to prevent the Dutch from profiting from the slave trade as much as other European states. But along with the kind of Calvinist restraint that recoiled from the Spanish baroque, the experience of colonialism may have contributed to an emergent aesthetic that allowed for abundance but drew a line against triumphalism.

The abundant imagery of flowers, fruit, and wine in Dutch still life pictures evoked reflections on mortality through images of dead animals such as birds, rabbits, or fish that were to be prepared as food. Dead animals are also a recurring feature of contemporary art, where they are reconstructed through taxidermy and often appear in a strange new poetic alluding to questions of the industrialized production of animals or global species extinctions. The contemporary Dutch taxidermist company Darwin, Sinke & Tongeren, on the other hand, sells stuffed animals in exhibitions with titles such as New Masters in homage to the seventeenth-century Dutch still life. In 2015, the company exhibited examples of its taxidermy in London, where the British artist Damien Hirst bought every item for his private collection. Hirst’s artworks from the early 1990s of animals preserved in glass tanks of formaldehyde are well known as modern memento mori , although his more recent meditations on death have focused in greater detail on objects saturated by global capital, the subject of the following section.

Global Liquidity

Hirst refers to the currency of diamonds rather than money as such, although their monetary status is clear enough in his paintings and display cabinets with synthetic diamonds. 3 In his major work For the Love of God (2007), references to big money are more explicit because Hirst had a London jeweler construct a platinum replica of an eighteenth-century human skull, embellishing it with the original teeth and 8,600 flawless diamonds at 1,106.18 carats valued somewhere around £10–14 million. On his website, 4 Hirst gave some clues to his thinking about this work:

It becomes necessary to question whether they are “just a bit of glass,” with accumulated metaphorical significance? Or [whether they] are genuine objects of supreme beauty connected with life. 5 The cutthroat nature of the diamond industry, and the capitalist society which supports it, is central to the work’s concept. . . . The stones “bring out the best and the worst in people . . . people kill for diamonds, they kill each other.” 6

These questions seem reasonable enough, but the work was also designed to maximize publicity and, in effect, comments more eloquently on the global art market than on extractive mining or blood diamonds. Hirst marketed the skull for £50 million, and it remains controversial whether or not the artist later sold it for this sum to an anonymous consortium. What it did achieve, however, was a tryst with the media in partnership with an image of a wealthy celebrity artist, vigilant in the protection and promotion of his own brand while also managing a fashionably sardonic refutation of the romantic myth of the heroically impoverished artist.

By contrast, the artists of the Danish art collective Superflex have for some years made elaborate artworks aimed as direct hits on the global system of corporate capitalism. For example, their 2009 video, The Financial Crisis , took advantage of the stock market crash of 2008 and subsequent volatility in global markets to call attention to how global liquidity is manipulated in ways that leave most people with little sense of control. Superflex had an actor perform as a traditional hypnotist seeking to control viewers into believing they were the “invisible hand” of the market. Viewers were then addressed as if—in a hypnotized state—they had assumed the personality of one of the global financial elite and hence would suddenly be able to wake from the nightmare of their financial insecurity to become fully alert to how capital actually works. Like their work Flooded McDonald’s (2009), in which global sea level rise appears to swamp the global fast-food franchise, The Financial Crisis puts satirical humor to good effect so that political critique is close enough to the rhetorical surface of the work to become part of the joke. Later, in an exhibition held in Mexico City, The Corrupt Show and Speculative Machine (2014), Superflex offered the idea of copying corruption as a useful tool for political sedition. Held on the grounds of a Jumex Mexican fruit juice plant to which the factory workers were invited, the exhibition featured banners of “bankrupt banks” displaying the corporate logos of the failed companies the workers once trusted. Viewers were also invited to participate in a work called Copy Light/Factory , encouraging them to appropriate intellectual property, trademarks, global brand ownership, and patents by scanning or photocopying. In ridiculing the corporatization of everyday life, Superflex also provided all the components of popular domestic lamp products so that people could make their own lamps from contemporary design copyrights. In a similar spirit, the group has also opened free shops as artworks. Indistinguishable from ordinary shops, there are no references to art, Superflex, the sponsors, or the word “free” so that buyers only realize there is no cost involved when they receive a printed bill for zero. Superflex’s elaborate strategies include publications on political critique and seminars during which the public is invited to question how global corporations impact on people’s everyday lives. Superflex’s work is clearly a dedicated attempt to provoke counter-narratives to those sanctioned by multinational companies, and it often succeeds because it combines these questions with shrewd satire and innovative ways of engaging its audiences through artworks.

In her work RMB City from 2009, digital artist Cao Fei invited the public to visit her virtual city in the online world of Second Life. Named after the abbreviation for the Renminbi, the currency of the People’s Republic of China, the City Planning for RMB City can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MhfATPZA0g . This playful reflection on life in a Chinese global megacity is followed in other sequences based on the activities of a number of digital avatars living in the city. At first glance, the world of RMB City appears to be an attractive site of hybrid Eastern and Western mythologies—complete with a big floating panda bear and giant sinking statues of Chairman Mao. But RMB City also acknowledges history, as one of the avatars, Uncle Mars, explains to the baby “Little China Sun” ( Live in RMB City , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61k679iP2xU ):

The buildings of this city are merely incarnations of your parents. In another time and space, they reverberate with the hollow shells of despair.

This is a real-world memory inside RMB City, where heroic Chinese modernity meets hard labor and the deepening gulf between wealth and poverty. Moreover, even in the futuristic, super-flat contours of Second Life , where dirt or pain are rarely seen, Cao Fei includes tanks, container ships, belching smokestacks, and the unmistakable signs of pollution gushing from giant drains. Yet her gentle satire on global capital is ambivalent: RMB City is polluted and there are metaphoric shadows that can be glimpsed in the flatness of this digital world, yet it also offers a buoyantly optimistic vision of the potential of technology and the future of China in the world.

Other approaches to money in contemporary art also appear to have a satirical edge, yet this too is frequently ambiguous, as in the case of the German artist Hans-Peter Feldmann, who works in art-multiples based on the playful reconfiguration of traditional taxonomies of apparently arbitrary images drawn from everyday life. In 2010, Feldmann was awarded the prestigious $100,000 Hugo Boss art prize that includes an exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York City. Following this, in 2011, Feldman devised The Art and Money Project , an installation at the Guggenheim where 100,000 real $1 bills were fixed to the walls. Feldmann’s gesture could be read as a statement that the collapsing of distinctions between art and money simply represents a basic category error, yet it could also be understood as a recognition that institutions such as the Guggenheim play a powerful role in determining which artworks become global investments. And it is perhaps for this reason that Cao Fei has carefully constructed a “Guggenheim of the Virtual World” in her RMB City. Understandably, Feldmann took his money home after the exhibition, unlike the British artist Jimmy Cauty and his friend Bill Drummond, who, after becoming wealthy in the 1980s following their years in the successfully edgy band KLF, decided to send a message to the culture industry with an utterly insouciant project: K Foundation Burn a Million Quid. This project was undertaken with real money in August 1994, when it was also filmed.

Artists who do not share such celebrity status are often dissatisfied with the money galleries apportion to them on the sale of their works, and they occasionally make these concerns explicit, as for example in the 2009 work Distribution of Wealth by the Seattle-based arts collective SuttonBeresculler. These artists took a pile of 100 $1 bills and cut them neatly into proportioned pieces to expose the small remuneration received by artists from dealers and galleries. Blake Fall-Conroy’s Minimum Wage Machine (2008–2010), on the other hand, was concerned with more general inequality in the social distribution of wealth. For this project, the artist made a hand-operated vending machine that released one penny for approximately 5 seconds of turning, or $7.67 an hour—a sum representing the minimum wage received by 1.8 million Americans in 2010, while at the same time a further 2.5 million people were paid less than the minimum wage. 7

The theme of money persists in more recent art, as in Vienna in 2015, where an entire series of exhibitions was based on art about money. Photographs of vaults filled with gold bars were joined by virtual art platforms on which the group Cointemporary sold art online for Bitcoin currency, and a work by Tom Molloy, Swarm (2006), comprised a swarm-like mass of dollar bills folded as paper planes that appeared to have pierced the gallery walls. The walls of the world’s galleries, this work seems to suggest, are as malleable to the flow of capital as the international market that rapidly adapts to most art-based social critiques through the processes of exclusivity and commodification. Hence, one of the most contemptuous anti-establishment gestures in modern art, the common urinal Marcel Duchamp transformed as a dada Fountain in 1917, by 2002 sorely disappointed auctioneers at Phillips de Pury & Luxembourg when it fetched a mere £1,185,000.

Displaced Worlds

As much of the world’s history of art patronage indicates, however, there is no cultural law demonstrating how big money compromises aesthetic value, yet on the other hand, when art is valued for the density of its saturation by market value alone, its affective meanings become warped. Apart from their effect on art, inflated art market values also obviously reveal massive differences between the cultural agency of a privileged few and that in the world of the poor, where even the prospect of functioning urinals or clean water is unlikely. Nonetheless, new cultural geographies of inequality have become another major theme of contemporary art, where such artworks are negotiated in the constantly shifting spaces between their means of production and the exclusive sites of their reception in contemporary galleries or the even more rarified domains of corporate philanthropy. These are the main outlets for artists adapting to the aesthetics challenges of representing shifting geopolitical boundaries ( Belting, Birken, and Buddensieg 2011 ; Harris 2011 ; Philipsen 2010 ) or migratory cultures ( Bal and Hernandez-Navarro 2011 ; Barriendos Rodriguez 2011 ) as they attempt to offer viable alternatives to the stream of mass media images in which the anguished face of one refugee seems to meld seamlessly with so many others. Although art in public spaces appears to offer alternative avenues to the usual outlets for artists, access and funding for art to urban sites also require negotiation with civic bodies and developers. And because urban artworks are often publicly contentious, a common solution is often the kind of aesthetic compromises that litter cities with dreary large-scale objects, directing the business of the cutting edge either to ephemeral public artworks or right back into the domain of the gallery.

In 2009, the French Algerian artist Kader Attia brought the shantytowns and markets of North Africa into the public event of the Biennale of Sydney with a work called Kasbah. Attia recycled materials similar to those recycled as roofs by people in urban slums throughout the world: corrugated iron, old doors, scrap metal, along with the ubiquitous satellite dish. This was not a work inviting an easy stroll through an exotic kasbah because the makeshift roofs completely covered the floor so that visitors were required to walk on top of them. It is difficult to gauge what visitors made of the overworked symbolism implied by trampling over the roofs of the poor, but at least the point appeared to be to make the physical negotiation of the work noisy and difficult and to alert people to watch their step.

In an earlier work, Ghost (2007), Attia filled a room with the hollow shapes of enrobed Muslim women made entirely out of tinfoil, kneeling uniformly in prayer. This work was purchased by the influential British collector George Saatchi, who included it the Saatchi Gallery exhibition Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East , and it is described on the Saatchi website as follows:

Attia’s figures become alien and futuristic, synthesising the abject and divine. Bowing in shimmering meditation, their ritual is equally seductive and hollow, questioning modern ideologies—from religion to nationalism and consumerism—in relation to individual identity, social perception, devotion and exclusion. 8

Whatever Attia’s own perception may be of women at prayer, the romanticization of the other in such art-speak obfuscation seems to filter out the lived experience of a largely hidden world rather than bringing us closer to understanding it. It also exposes the risk that the incorporation of cultural difference into the established art system might ultimately lead to a homogeneity that is “equally seductive and hollow.”

Other works are less at risk of mystification, such as those by the Indian artists of RAQS Media Collective, who created a series of hollow and partial figures in white fiberglass, Coronation Park , for the 2015 Venice Biennale. This work was a direct reference to a neglected park of that name in Delhi, where there are still a range of grandiose marble statues of monarchs, viceroys, and colonial officials from the days of the British Raj. For some years, RAQS has been engaged in a robust investigation of concepts of time and how history can be read in the present, and Coronation Park brings that intellectual focus to bear on the ultimate hollowness at the center of imperial power. The transitory nature of colonial authority is made clear enough in these figural sculptures to be generally accessible, not only because they are grounded in history but also because there were circular discs on the plinths with imaginary epitaphs that brought the History of Great Men into the realm of common personal emotions. Hence, beneath one rather pompous-looking figure, RAQS wrote, “The crowd would laugh at him. And his whole life was one long struggle not to be laughed at.” On the plinth of another was written, “It was at this moment, as he stood there with the weapon in his hands, that he first grasped the hollowness, the futility,” and by a figure that seemed to embody the gradual entropy in the pursuit of power, RAQS wrote, “In the end he could not stand it any longer and went away.”