Political crime and corruption take center stage: introductory notes

- Published: 17 March 2021

- Volume 75 , pages 195–200, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Mary Dodge ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2662-8301 1 &

- Henry N. Pontell 2

5550 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The incidence of political crime, both known and unknown, is likely to exceed even the most unhinged estimates of what actually occurs in the elite world of white-collar criminality. In short, data on the exact number of crimes and unethical acts committed globally by politicians and corporations are unattainable. This problem exists due to the structurally veiled nature of political criminal behavior more generally. White-collar crime conducted by high-level officials often is hidden from public view, though, as one article documents in this issue, offenders may now more openly commit unspeakable acts that become normalized, by airing dirty laundry and situating crimes in the public domain as acceptable or inevitable. This special issue offers current perspectives on political corruption that represent singularly distinct but overlapping research and commentary on the insidious and global nature of white-collar crime.

Definitions of what political crime entails are controversial, which can make it difficult to pinpoint what happened, who was responsible, and why it occurred. Offenders and offenses present a wide array of wrongdoing and opportunities for analysis. Hence, white-collar crime researchers face perplexing issues when dealing with the complexities relating to both definitions and data access. These obstacles need to be overcome in order to provide better understandings of political corruption and the necessary means to combat it.

Political crime easily fits within the parameters of white-collar crime, though some offenses against the state may represent outliers. For example, in one major analysis Ross ( 2003 :2) emphasized that there remained “considerable confusion about what constitutes a political offense.” Conceptual issues in white-collar crime, as noted by scholars Shover and Wright [ 12 ], result in skirmishes over offender/offense distinctions and definitions that may make even the most experienced researchers squeamish. Political offenses include crimes against the state (e.g., insurrection, terrorism, sedition) and by the state (i.e., illegal or unethical acts by political figures). More common forms include bribery, ethical misconduct, election manipulations, graft, nepotism, looting, and misuse of financial resources. Political offending can also include war crimes, genocide and ethnic cleansing, espionage, assassinations, illegal experiments, terrorism, human rights violations, money laundering, theft, and wrongful incarceration [ 2 , 7 , 9 ]. In this issue, Joel Martinsson notes that discovering an “all-encompassing corruption definition would for corruption researchers be like finding the Holy Grail.”

Definitions of political crime are considered “broad and ill defined” and accusations of corruption can be all-encompassing and relatively common [ 1 ]: 201,[ 8 ]. Many scholars have adopted a state crime approach, though they readily concede that expansion of this term results in a definition that might include any “undesirable activities,” which, according to Sharkansky [ 11 ] represents an “intellectual transgression.” Friedrichs [ 5 ] also acknowledged the confusion surrounding state and governmental crimes with the latter representing a wide-range of misdeeds committed in a governmental context, often by an individual, and dependent on occupational status. The former, as defined by Friedrichs, represents actions carried out by the state itself. Geis and Meier [ 6 ] propose a rather straightforward definition of political crime that fits well-within traditional notions of white-collar criminality more generally,illegal actions committed by political officeholders in the course of their duties. An exhaustive exploration of definitional issues of political crime is beyond the scope of this introduction, but it can be emphasized that the concept continues to defy clear demarcations, and purposed definitions may result in a quagmire of incongruous offenses that are difficult to sort out accordingly.

Global jurisdictional issues, cover-ups, financial complexities, legal technicalities, political structures, and economic considerations also make attempts to research political crime difficult. The generally hidden nature of political crime involves acts by ruling elites that are clearly corrupt, yet fully ingrained in existing societal arrangements that act to thwart enforcement efforts, regulatory action, and judicial involvement. Most recently, the normalization of political malfeasance has resulted from the repeated “look at me” attitude and displays of Donald Trump as U.S. president.

Public complacency has developed from the number of overt illegal and immoral acts that are ignored, accepted, or unpunished. In this issue, Pontell, Tillman, and Ghazi-Tehrani offer a new perspective on the criminal debacle of Donald Trump’s presidency. The authors frame the newest “gate” as reminiscent of a publicly-aired Watergate scandal, and examine how the alleged offenses are flagrant acts enabled by the proliferation of a new lexicon of “fake news,” “cancel culture,” “cult of the personality,” “whataboutism,” and “not me” that assisted in rationalizing wrongdoing. Pontell, Tillman and Ghazi-Tehrani explore the Trump administration’s maneuvers to neutralize illegal and unethical acts in a public forum, making significant segments of the population more accepting of a wide range of political crimes. They also consider these moves as part of a larger existential war against white-collar and corporate crime in the United States, that not only sought to reduce regulatory capacity and enforcement efforts, but to normalize such offending itself.

Corruption in government is often explored using indices such as the World Bank’s Control of Corruption, and Transparency International’s Corruption Perception, and Global Integrity, which allow for quantitative comparisons across countries. Transparency International, established in mid-1990s, compiles information on corruption scandals involving “bribes and money laundering of epic proportions” (see Table 1 ). While particular cases are anecdotal, overall the criminal enterprises note the need for additional prosecution and preventive policies.

In many cases, political figures who reap the benefits of their ill-gotten gains have seized opportunities afforded to them by positions that feed their greed and inhumanity. In Peru, former president Alberto Fujimori, maintained a high public approval rating, despite bribing politicians and judges, employing death squads to kill guerillas, and embezzling at least US$600 million. Similarly, Ramzen Kadyrov, the head of Chechnya, used public funds to throw birthday parties and buy a US $2-million-dollar private boxing session with former world heavyweight boxing champion, Mike Tyson. While living in a palace with his pet tiger, Kadyrov ordered the killing of numerous rivals and committed a host of human rights violations [ 13 ].

Perhaps the most heinous political crimes documented by Transparency International are those involving collusion between governmental officials and companies [ 14 ]. Siemens Corporation, a German company, provoked a worldwide scandal by engaging in a bribery scheme with government officials and civil servants that involved approximately US$1.4 billion.

The extensive networks of political crime immersed in alliance with legitimate businesses is sometimes discovered only after a massive depletion of private and public funds. Research studies that focus on specific aspects of political crime continue to add impressive perspectives and endeavors to expand the extant literature. In this issue, Fiona Chan, Carole Gibbs, Rachel Boratto, and Mark Speers offer an innovative examination of transnational corporate bribery. The authors acknowledge the importance of employing a white-collar crime framework to research corruption and corporate bribery. Chan and colleagues’ work utilizes violation data of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act from the US Department of Justice’s Fraud Section. The article offers a valuable and insightful analysis that establishes a theoretical and practical framework for exploring and researching corporate bribery.

Political crime is highly problematic in that the extent and nature of offenses act to destroy public trust and create feelings of helplessness in the populace. Indeed, identified corruption by a political leader may result in outrage and protests but the elite offender can create a safe haven for their actions by virtue of their position. In 2014, The Pew Research Center released the findings of a global study in which it found that a median of 83% of people across 34 emerging and developing economies responded that crime in their countries was a major problem, and that 76% saw corrupt political leaders in the same way. Additionally, corruption was perceived to be highest in Africa, followed by Ukraine, Russia, and China. Respondents from Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East saw crime and corruption as the greatest problems in their countries. [ 10 ]. Despite such findings of citizen recognition of the problem, Ross [ 8 ] noted that the proliferation of corruption also “hampers public understanding” and results in “cynicism, skepticism, and complacency (p. 2).” Martinsson (this issue) cites a 2019 Pew Research Center survey finding that 81 percent of Americans distrust congress and 68 percent of the population in the European Union view corruption as a major problem.

Through detailed historical analysis, Børge Bakken and Jasmine Wang detail the growth of corruption in modern China. Their narrative of the influence of culturally embedded views identifies the changing forms of corruption in China and the connections between political elites and entrepreneurs. The authors adopt a critical perspective on white-collar crime in explaining how corruption and oppression is essential to exploitation that erodes public trust. The article places corruption in the contextual experiences of a single party autocracy that saw practices evolve that emphasized “decentralization without accountability,” resulting in increased wrongdoing at local levels.

Joel Martinsson’s article acknowledges that preventing corruption is problematic and that current approaches have created a false dichotomy. Martinsson emphasizes the need to look beyond the two popular frameworks—principle-agent and collective-action—in order to effectively prevent institutional corruption. He adopts a policy-centered approach toward systemic corruption that can address “honest graft” in established democracies. His portrayal of George Washington Plunkitt’s case ironically mirrors current events in the United States, as well as global problems that systematically reproduce political crimes.

Efforts to research sanctions and prevention efforts directed at political crime are challenging, especially across local and global jurisdictions. Carlos Novella-García and Alexis Cloquell-Lozano’s article addresses corruption in Spain. They employ a sophisticated analysis with a framework of Hermeneutic definitions of maxima and minima and social justice and offer prevention suggestions that stress the importance of public ethics as a mechanism for reducing corruption. They explore various theoretical approaches and provide a historical narrative for a case study of public corruption in Spain. When corruption is perceived as widespread, according to the authors, political and public ethics are needed to ensure that “the human condition is not easily corrupted by the act of wanting greater prestige, more power, and more money.”

Despite progress in the study of political crime and corruption, they still rage on today throughout the world and result in major societal losses. Moreover, like white-collar crime more generally, their social costs are physical as well as financial, or, as William Black has put it in challenging common business narratives, “corruption kills” [ 3 ]. Future research is warranted for both theory development, and prevention and control efforts.

Several major themes throughout the articles that follow are summarily captured by Ferrari who, a century ago, wrote:

This absolute contrast in the treatment of political criminals is due to a change of interpretation of their character and of their role from the point of view of the evolution of humanity. Whereas formerly the political criminal was treated as a public enemy, he is today considered as a friend of the public good, as a man of progress, desirous of bettering the political institutions of his country, having laudable intentions, hastening the onward march of humanity, his only fault being that he wishes to go too fast, and that he employs, in attempting to realize the progress which he desires, means irregular, illegal and violent (1920: 312).

Ferrari, despite the dearth of literature on white-collar crime at the time, further concluded that the “political criminal is reprehensible and ought to be punished in the interest of the established order, his criminality can- not be compared with that of the ordinary malefactor, with the murderer, the thief, etc.”

We extend our appreciation and thanks to all the authors who contributed to this valuable and timely issue.

Mary Dodge and Henry N. Pontell.

Allen, H. E., Friday, P. C., Roebuck, J. B., & Sagarin, E. (1981). Crime and punishment: An introduction to criminology (pp. 4–8). Free Press.

Google Scholar

Barak, G. (1991). Crimes by the capitalist state: An introduction to state criminality . State University of New York Press.

Black, W. K. (2007). Corruption kills. In H. N. Pontell & G. Geis (Eds.), International Handbook of White-Collar and Corporate Crime (pp. 439–455). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ferrari, R. (1920). Political crime. Columbia Law Review, 20, 308.

Article Google Scholar

Friedrichs, D. O. (2000). State crime or governmental crimes: Making sense of the conceptual confusion. In J. A. Ross (Ed.), Controlling state crime (pp. 53–80). Transaction Publishers.

Geis, G., & Meier, R. F. (1977). White-collar crime: Offenses in business, politics, and the professions (rev). Free Press.

Hagan, F. E. (1997). Political crime: Ideology and criminality . Allyn and Bacon.

Ross, J. A. (2003). The dynamics of political crime . Sage Publications.

Ross, J. A. (2000). Controlling state crime (2nd ed.). Transaction Publishers.

Pew Research Center (2014). Crime and corruption top problems in emerging and developing countries. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2014/11/06/crime-and-corruption-top-problems-in-emerging-and-developing-countries . Accessed 20 Feb 2021.

Sharkansky, I. (2000). A state action may be nasty but is not likely to be a crime. In J. A. Ross (Ed.), Controlling state crime (pp. 35–52). Transaction Publishers.

Shover, N., & Wright, J. P. (Eds.). (2001). Crimes of privilege: Readings in white-collar crime . Oxford University Press.

The Guardian (2015). Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/23/putins-closest-ally-and-his-biggest-liability2015/sep/23/putins-closest-ally-and-his-biggest-liability . Accessed 20 Feb 2021.

Transparency International (2019). Retrieved from https://www.transparency.org/en/news/25-corruption-scandals#Siemens . Accessed 20 Feb 2021.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Colorado Denver, Campus Box 142, P.O Box 173364, Denver, CO, 802017, USA

John Jay College of Criminal Justice, New York, NY, 10019, USA

Henry N. Pontell

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mary Dodge .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dodge, M., Pontell, H.N. Political crime and corruption take center stage: introductory notes. Crime Law Soc Change 75 , 195–200 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-021-09950-5

Download citation

Accepted : 28 February 2021

Published : 17 March 2021

Issue Date : April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-021-09950-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

The Rise of Political Violence in the United States

- Rachel Kleinfeld

Select your citation format:

Recent alterations to violent groups in the United States and to the composition of the two main political parties have created a latent force for violence that can be 1) triggered by a variety of social events that touch on a number of interrelated identities; or 2) purposefully ignited for partisan political purposes. This essay describes the history of such forces in the U.S., shares the risk factors for election violence globally and how they are trending in the U.S., and concludes with some potential paths to mitigate the problem.

O ne week after the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Eric Coomer, an executive at Dominion Voting Systems, was forced into hiding. Angry supporters of then-president Donald Trump, believing false accusations that Dominion had switched votes in favor of Joe Biden, published Coomer’s home address and phone number and put a million-dollar bounty on his head. Coomer was one of many people in the crosshairs. An unprecedented number of elections administrators received threats in 2020—so much so that a third of poll workers surveyed by the Brennan Center for Justice in April 2021 said that they felt unsafe and 79 percent wanted government-provided security. In July, the Department of Justice set up a special task force specifically to combat threats against election administrators. 1

From death threats against previously anonymous bureaucrats and public-health officials to a plot to kidnap Michigan’s governor and the 6 January 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, acts of political violence in the United States have skyrocketed in the last five years. 2 The nature of political violence has also changed. The media’s focus on groups such as the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, and Boogaloo Bois has obscured a deeper trend: the “ungrouping” of political violence as people self-radicalize via online engagement. According to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), which maintains the Global Terrorism Database, most political violence in the United States is committed by people who do not belong to any formal organization.

About the Author

Rachel Kleinfeld is senior fellow in the Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. She was the founding CEO of the Truman National Security Project and serves on the National Task Force on Election Crises.

View all work by Rachel Kleinfeld

Instead, ideas that were once confined to fringe groups now appear in the mainstream media. White-supremacist ideas, militia fashion, and conspiracy theories spread via gaming websites, YouTube channels, and blogs, while a slippery language of memes, slang, and jokes blurs the line between posturing and provoking violence, normalizing radical ideologies and activities.

These shifts have created a new reality: millions of Americans willing to undertake, support, or excuse political violence, defined here (following the violence-prevention organization Over Zero) as physical harm or intimidation that affects who benefits from or can participate fully in political, economic, or sociocultural life. Violence may be catalyzed by predictable social events such as Black Lives Matter protests or mask mandates that trigger a sense of threat to a common shared identity. Violence can also be intentionally wielded as a partisan tool to affect elections and democracy itself. This organizational pattern makes stopping political violence more difficult, and also more crucial, than ever before.

Political Violence in the United States Historically

Political violence has a long history in the United States. Since the late 1960s, it was carried out by intensely ideological groups that pulled adherents out of the mainstream into clandestine cells, such as the anti-imperialist Weather Underground Organization or the anti-abortion Operation Rescue. In the late 1960s and 1970s, these violent fringes were mostly on the far left. They committed extensive violence, largely against property (with notable exceptions), in the name of social, environmental, and animal-rights causes. Starting in the late 1970s, political violence shifted rightward with the rise of white supremacist, anti-abortion, and militia groups. The number of violent events declined, but targets shifted from property to people—minorities, abortion providers, and federal agents.

What is occurring today does not resemble this recent past. Although incidents from the left are on the rise, political violence still comes overwhelmingly from the right, whether one looks at the Global Terrorism Database, FBI statistics, or other government or independent counts. 3 Yet people committing far-right violence—particularly planned violence rather than spontaneous hate crimes—are older and more established than typical terrorists and violent criminals. They often hold jobs, are married, and have children. Those who attend church or belong to community groups are more likely to hold violent, conspiratorial beliefs. 4 These are not isolated “lone wolves”; they are part of a broad community that echoes their ideas.

Two subgroups appear most prone to violence. The January 2021 American Perspectives Survey found that white Christian evangelical Republicans were outsized supporters of both political violence and the Q-Anon conspiracy, which claims that Democratic politicians and Hollywood elites are pedophiles who (aided by mask mandates that hinder identification) traffic children and harvest their blood; separate polls by evangelical political scientists found that in October 2020 approximately 47 percent of white evangelical Christians believed in the tenets of Q-Anon, as did 59 percent of Republicans. 5 Many evangelical pastors are working to turn their flocks away from this heresy. The details appear outlandish, but stripped to its core, the broad appeal becomes clearer: Democrats and cultural elites are often portrayed as Satanic forces arrayed against Christianity and seeking to harm Christian children.

The other subgroup prone to violence comprises those who feel threatened by either women or minorities. The polling on them is not clear. Separate surveys conducted by the American Enterprise Institute and academics in 2020 and 2021 found a majority of Republicans agreeing that “the traditional American way of life is disappearing so fast” that they “may have to use force to save it.” Respondents who believed that whites faced greater discrimination than minorities were more likely to agree. 6 Scholars Nathan Kalmoe and Lilliana Mason found that white Republicans with higher levels of minority resentment were more likely to see Democrats as evil or subhuman (beliefs thought to reduce inhibitions to violence). However, despite these feelings, the racially resentful did not stand out for endorsing violence against Democrats. Instead, the people most likely to support political violence were both Democrats and Republicans who espoused hostility toward women. 7 A sense of racial threat may be priming more conservatives to express greater resentment in ways that normalize violence and create a more permissive atmosphere, while men in both parties who feel particularly aggrieved toward women may be most willing to act on those feelings.

The bedrock idea uniting right-wing communities who condone violence is that white Christian men in the United States are under cultural and demographic threat and require defending—and that it is the Republican Party and Donald Trump, in particular, who will safeguard their way of life. 8 This pattern is similar to that of political violence in the nineteenth-century United States, where partisan identity was conflated with race, ethnicity, religion, and immigration status; many U.S.-born citizens felt they were losing cultural power and status to other social groups; and the violence was committed not by a few deviant outliers, but by many otherwise ordinary citizens engaged in normal civic life.

Changing social dynamics were the obvious spur for this violence, but it often yielded political outcomes. The ambiguity incentivized and enabled politicians to play with fire, deliberately provoking violence while claiming plausible deniability. In the 1840s and 1850s, from Maine and Maryland to Kentucky and Louisiana, the Know-Nothing party incited white Protestants to riot against mostly Catholic Irish and Italian immigrants (seen as both nonwhite and Democratic Party voters). When the Know-Nothings collapsed in 1855 in the North and 1860 in the South, anti-Catholic violence suddenly plummeted, despite continued bigotry. In the South, white supremacist violence was blamed on racism, but the timing was linked to elections. After the Supreme Court ruled in 1883 that the federal government lacked jurisdiction over racist terror, overturning the 1875 Civil Rights Act, violence became an open campaign strategy for the Democratic Party in multiple states. Lynchings were used in a similar manner. While proximate causes were social and economic, their time and place were primed by politics: Lynchings increased prior to elections in competitive counties. 9 Democratic Party politicians used racial rhetoric to amplify anger, then allowed violence to occur, to convince poor whites that they shared more in common with wealthy whites than with poor blacks, preventing the Populist and Progressive Parties from uniting poor whites and blacks into a single voting base. As Jim Crow laws enshrined Democratic one-party control, lynchings were not needed by politicians. Their numbers fell swiftly; they were no longer linked to elections. 10

Risk Factors for Election Violence

Globally, four factors elevate the risk of election-related violence, whether carried out directly by a political party through state security or armed party youth wings, outsourced to militias and gangs, or perpetrated by ordinary citizens: 1) a highly competitive election that could shift the balance of power; 2) partisan division based on identity; 3) electoral rules that enable winning by exploiting identity cleavages; and 4) weak institutional constraints on violence, particularly security-sector bias toward one group, leading perpetrators to believe they will not be held accountable for violence. 11

The rise of the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) illustrates this dynamic. In 2002, a train fire killed Hindu pilgrims returning to Gujarat, India, from a contested site in Ayodhya. An anti-Muslim pogrom erupted. India’s current prime minister, the BJP’s Narendra Modi, was then chief minister of Gujarat. During three days of violence directed almost entirely against Muslims, he allowed the police to stand by and afterward refused to prosecute the rioters. The party won state legislative elections later that year by exploiting Hindu-Muslim tensions to pry Hindu voters from the Congress Party. The party has since stoked ethnic riots to win in contested areas across the country, and Modi reprised the strategy as prime minister. 12

In India’s winner-take-all electoral system, mob violence can potentially swing elections. Though fueled by social grievance, mob violence is susceptible to political manipulation. This is the form of electoral violence most like what the United States is experiencing, and it is particularly dangerous. Social movements have goals of their own. Though they may also serve partisan purposes, they can move in unintended directions and are hard to control.

Today, the risk factors for electoral violence are elevated in the United States, putting greater pressure on institutional constraints.

Highly competitive elections that could shift the balance of power: Heightened political competition is strongly associated with electoral violence. Only when outcomes are uncertain but close is there a reason to resort to violence. For much of U.S. history, one party held legislative power for decades. Yet since 1980, a shift in control of at least one house of Congress was possible—and since 2010, elections have seen a level of competition not seen since Reconstruction (1865–77). 13

Partisan division based on identity: Up to the 1990s, many Americans belonged to multiple identity groups—for example, a union member might have been a conservative, religious, Southern man who nevertheless voted Democratic. Today, Americans have sorted themselves into two broad identity groups: Democrats tend to live in cities, are more likely to be minorities, women, and religiously unaffiliated, and are trending liberal. Republicans generally live in rural areas or exurbs and are more likely to be white, male, Christian, and conservative. 14 Those who hold a cross-cutting identity (such as black Christians or female Republicans) generally cleave to the other identities that align with their partisan “tribe.”

As political psychologist Lilliana Mason has shown, greater homogeneity within groups with fewer cross-cutting ties allows people to form clearer in- and out-groups, priming them for conflict. When many identities align, belittling any one of them can trigger humiliation and anger. Such feelings are heightened by policy differences but are not about policy; they are personal, and thus are more powerful. These real cultural and belief differences are at the heart of the cultural conflicts in the United States.

U.S. party and electoral institutions are intensifying rather than reducing these identity cleavages. The alignment of racial and religious identity with political party is not random. Sorting began after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1965 as whites who disagreed with racial equality fled the Democratic Party. A second wave—the so-called Reagan Democrats, who had varied ideological motivations, followed in 1980 and 1984. A third wave, pushed away from the Democratic Party by the election of Barack Obama and attracted by Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, drew previous swing voters who were particularly likely to define “Americanness” as white and Christian into the Republican Party. 15

A 2016 Pew Research Center poll found that 32 percent of U.S. citizens believed that to be a “real American,” one must be a U.S.-born Christian. But among Trump’s primary voters, according to a 2017 Voter Study Group analysis, 86 percent thought it was “very important” to have been born in the United States; 77 percent believed that one must be Christian; and 47 percent thought one must also be “of European descent.” 16 According to Democracy Fund voter surveys, during the 2016 primaries, many economic conservatives, libertarians, and other traditional Republican groups did not share these views on citizenship. By 2020, however, white identity voters made up an even larger share of the Republican base. Moreover, their influence is greater than their numbers because in the current U.S. context—where identities are so fixed and political polarization is so intense—swing voters are rare, so it is more cost-effective for campaigns to focus on turning out reliable voters. The easiest way to do this is with emotional appeals to shared identities rather than to policies on which groups may disagree. 17 This is true for both Republicans and Democrats.

The Democratic Party’s base, however, is extremely heterogeneous. The party must therefore balance competing demands—for example, those of less reliable young “woke” voters with those of highly reliable African American churchgoers, or those of more-conservative Mexican American men with those of progressive activists. In contrast, the Republican Party is increasingly homogenous, which allows campaigns to target appeals to white, Christian, male identities and the traditional social hierarchy.

The emergence of large numbers of Americans who can be prompted to commit political violence by a variety of social events is thus partially an accidental byproduct of normal politics in highly politically sorted, psychologically abnormal times. Even in normal times, people more readily rally to their group’s defense when it is under attack, which is why “ they are out to take your x” is such a time-honored fundraising and get-out-the-vote message. Usually, such tactics merely heighten polarization. But when individuals and societies are highly sorted and stressed, the effects can be much worse. Inequality and loneliness, which were endemic in the United States even before the covid-19 pandemic and have only gotten worse since, are factors highly correlated with violence and aggression. Contagious disease, meanwhile, has led to xenophobic violence historically.

The confluence of these factors with sudden social-distancing requirements, closures of businesses and public spaces, and unusually intrusive pandemic-related government measures during an election year may have pushed the more psychologically fragile over the edge. Psychologists have found that when more homogenous groups with significant overlap in their identities face a sense of group threat, they respond with deep anger. Acting on that anger can restore a sense of agency and self-esteem and, in an environment in which violence is justified and normalized, perhaps even win social approval. 18

The sorts of racially coded political messages that have been in use for decades will be received differently in a political party whose composition has altered to include a greater percentage of white identity voters. Those who feel that their dominant status in the social hierarchy is under attack may respond violently to perceived racial or other threats to their status at the top. But those lower on the social ladder may also resort to violence to assert dominance over (and thus psychological separation from) those at the bottom—for example, minority men over women or other minorities, one religious minority over another, or white women over minority women. Antisemitism is growing among the young, and exists on the left, but is far stronger on the right, and is particularly salient among racial minorities who lean right. 19 On the far-left, violent feelings are emerging from the same sense of group threat and defense, but in mirror-image: Those most willing to dehumanize the right are people who see themselves as defending racial minorities.

Republicans and Democrats have been espousing similar views on the acceptability of violence since 2017, when Kalmoe and Mason began collecting monthly data.

Between 2017 and 2020, Democrats and Republicans were extremely close in justifying violence, with Democrats slightly more prone to condone violence—except in November 2019, the month before Trump’s first impeachment, when Republican support for violence spiked. Both sides also expressed similarly high levels of dehumanizing thought: 39 percent of Democrats and 41 percent of Republicans saw the other side as “downright evil,” and 16 percent of Democrats and 20 percent of Republicans said that their opponents were “like animals.” Such feelings can point to psychological readiness for violence. Separate polling found lower but still comparable levels: 4 percent of Democrats and 3 percent of Republicans believed in October 2020 that attacks on their political opponents would be justified if their party leader alleged the election was stolen; 6 percent of Democrats and 4 percent of Republicans believed property damage to be acceptable in such a case. 20

The parallel attitudes suggest that partisan sorting and social pressures were working equally on all Americans, although Republicans may have greater tolerance for online threats and harassment of opponents and opposition leaders. 21 Yet actual incidents of political violence, while rising on both sides, have been vastly more prevalent on the right. Why has the right been more willing to act on violent feelings?

The clue lies in the sudden shift in attitudes in October 2020, when after maintaining similarity for years, Republicans’ endorsements of violence suddenly leapt across every one of Kalmoe and Mason’s questions regarding the acceptability of violence; findings that were repeated in other polling. 22 In January 2020, 41 percent of Republicans agreed that “a time will come when patriotic Americans have to take the law into their own hands”; a year later, after the January 6 insurrection, 56 percent of Republicans agreed that “if elected leaders will not protect America, the people must do it themselves even if it requires taking violent action.” 23 Moral disengagement also spiked: By February 2021, more than two-thirds of Republicans (and half of Democrats) saw the other party as “downright evil,”; while 12 percent more Republicans believed Democrats were less than human than the other way around. 24

The false narrative of a stolen 2020 election clearly increased support for political violence. Those who believed the election was fraudulent were far more likely to endorse coups and armed citizen rebellion; by February 2021, a quarter of Republicans felt that it was at least “a little” justified to take over state government buildings with violence to advance their political goals. 25 This politically driven false narrative points to the role of politicians since 2016 in fueling the difference in violence between right and left. As has been found in Israel and Germany, domestic terrorists are emboldened by the belief that politicians encourage violence or that authorities will tolerate it. 26

It is not uncommon for politicians to incite communal violence to affect electoral outcomes. In northern Kenya, voters call this “war by remote control.” Incumbent leaders who fear losing are particularly prone to using electoral violence to intimidate potential opponents, build their base, affect voting behavior and election-day vote counts, and, failing all that, to keep themselves relevant or at least out of jail. 27 Communal violence can clear opposition voters from contested areas, altering the demographics of electoral districts, as happened in Kenya’s Rift Valley in 2007 and the U.S. South during Reconstruction. Violent intimidation can keep voters away from the polls, as has occurred since the 1990s in Bangladesh; from the 1990s through 2013 in Pakistan; and in the U.S. South in the 1960s.

Communal violence often flares in contested districts where it is politically expedient, as in Kenya and India. Likewise, political violence in the United States has been greatest in suburbs where Asian American and Hispanic American immigration has been growing fastest, particularly in heavily Democratic metropoles surrounded by Republican-dominated rural areas. These areas, where white flight from the 1960s is meeting demographic change, are areas of social contestation. They are also politically contested swing districts. Most of the arrested January 6 insurrectionists hailed from these areas rather than from Trump strongholds. 28 Postelection violence can also be useful to politicians. They can manipulate angry voters who believe their votes were stolen into using violence to influence or block final counts or gain leverage in power-sharing negotiations, as occurred in Kenya in 2007 and Afghanistan in 2019.

Not all political violence directly serves an electoral purpose. Using violence to defend a group bonds members to the group. Thus violence is a particularly effective way to build voter “intensity.” In 1932, young black-clad militants of the British Union of Fascists roamed England’s streets, picking fights and harassing Jews. The leadership of the nascent party realized that its profile grew whenever the “blackshirts” got into violent confrontations. Two years later, the party held a rally of nearly fifteen-thousand people that became a brutal melee between blackshirts and antifascist protestors. After the clash (which was not fully spontaneous), people queued to join the party for the next two days and nights and membership soared. 29 As every organizer knows, effective mobilization requires keeping supporters engaged. Given the role of gun rights to Republican identity, armed rallies can mobilize supporters and expand fundraising. Yet even peaceful rallies of crowds carrying automatic weapons can intimidate people who hold opposing views.

Finally, politicians may personally benefit from violent mobilization that is not election-related. In South Africa, former president Jacob Zuma spent years cultivating ties with violent criminal groups in his home state of Kwa-Zulu Natal. 30 When he was out of office and on trial for corruption and facing jail time for contempt of court, he activated those connections to spur a round of violence and looting on a scale not seen in South Africa since apartheid. Vast inequality, unemployment, and other social causes allowed for plausible deniability—many looters with no political ties were just joining in the fracas. Zuma has, as of this writing, avoided imprisonment due to undisclosed “medical reasons.”

Electoral rules enable winning by exploiting identity cleavages: The fissures in divided societies such as the United States can be either mitigated or enhanced by electoral systems. The U.S. electoral system comprises features that are correlated with greater violence globally. Winner-take-all elections are particularly prone to violence, possibly because small numbers of voters can shift outcomes. Two-party systems are also more correlated with violence than are multiparty systems, perhaps because they create us-them dynamics that deepen polarization. 31 Although multiparty systems allow more-extreme parties to gain representation, such as Alternative for Germany or Golden Dawn in Greece, they also enable other parties to work together against a common threat. The U.S. system is more brittle. A two-party system can prevent the representation of fringe views, as occurred for years in the United States—for example, American Independent Party candidate George Wallace won 14 percent of the popular vote in 1968 but no representation. Yet because party primaries tend to be low-turnout contests with highly partisan voters, small factions can gain outsized influence over a mainstream party. If that happens, extreme politicians can gain control over half of the political spectrum—leaving that party’s voters nowhere to turn.

Weak institutional constraints on violence: The United States suffers from three particularly concerning institutional weaknesses today—the challenge of adjudicating disputes between the executive and legislative branches inherent in presidential majoritarian systems, recent legal decisions enhancing the electoral power of state legislatures, and the politicization of law enforcement and the courts.

Juan Linz famously noted that apart from the United States, few presidential majoritarian systems had survived as continuous democracies. One key reason was the problem of resolving disputes between the executive and legislative branches. Because both are popularly elected, when they are held by different parties stalemates between the two invite resolution through violence. Such a dynamic drove state-level electoral violence throughout the nineteenth century, not only in the Reconstruction South, but also in Pennsylvania, Maine, Rhode Island, and Colorado. It is thus particularly concerning that in the last year, nine states have passed laws to give greater power to partisan bodies, particularly state legislatures. 32 The U.S. Supreme Court has also made several recent decisions vesting greater power over elections in state legislatures. These trends are weakening institutional guardrails against future political violence.

When law and justice institutions are believed to lean toward one party or side of an identity cleavage, political violence becomes more likely. International cases reveal that groups that believe they can use violence without consequences are more likely to do so. The U.S. justice system, police, and military are far more professional and less politicized than those of most developing democracies that face widespread electoral violence. Longstanding perceptions that police favor one side are supported by Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) data showing that police used far greater force at left-wing protests than at right-wing protests throughout 2020. Despite this conservative ideological tilt, party affiliation and feelings were more complicated: Law enforcement was also a target of right-wing militias, and partisan affiliation (based on donations) had previously been mixed due to union membership and other cross-cutting identities that connected police to the Democratic Party. In 2020, however, donations from individual law enforcement officers to political parties increased, and they tilted far toward the Republican Party, suggesting that the polarizing events of 2020 have led them to sort themselves to the right and deepen their partisanship. 33

How to Counter the Trends

Interventions in five key areas could help defuse the threat of political violence in the United States: 1) election credibility, 2) electoral rules, 3) policing, 4) prevention and redirection, and 5) political speech. The steps best taken depend on who is in power and who is committing the violence. Technical measures to enhance election credibility and train police can reduce inadvertent violence from the state. But such technical solutions will fail if the party in power is inciting violence, as happens more often than not. In that case, behind-the-scenes efforts to help parties and leaders strike deals or mediate grievances can sometimes keep violence at bay. In Kenya, for instance, two opposing politicians accused of leading election violence in 2007 joined forces to run as president and vice-president; their alliance enabled a peaceful election in 2013. Ironically, strong institutions, low levels of corruption, and reductions in institutionalized methods of elite deal-making (such as Congressional earmarks) make such bargains more difficult in the United States. However, the United States is helped by its unusually high level of federalism in terms of elections and law enforcement, because if one part of “the state” is acting against reform, it may still be possible at another level.

More credible elections: While there was no widespread fraud in the 2020 U.S. elections, international election experts agree that the U.S. electoral system is antiquated and prone to failure. The proposed Freedom to Vote Act, which enhances cybersecurity, protects election officers, provides a paper trail for ballots, and provides proper training and funding for election administration, among other measures, could offer the sort of bipartisan compromise that favors neither side and would shore up a problematic system. But if it is turned into a political cudgel, as is likely, it will fail to reassure voters, despite its excellent provisions.

Changing the electoral rules: Whether politicians use violence as a campaign strategy is shaped by the nature of the electoral system. A seminal study on India by Steven Wilkinson suggests that where politicians need minority votes to win, they protect minorities; where they do not, they are more likely to incite violence. 34 By this logic, Section 2 of the U.S. Voting Rights Act of 1965, which allows for gerrymandering majority-minority districts to ensure African American representation in Congress, may inadvertently incentivize violence by making minority votes unnecessary for Republican wins in the remaining districts . While minority representation is its own valuable democratic goal, creating districts where Republicans need minority votes to win—and where Democrats need white votes to win—might reduce the likelihood of violence.

Whether extremists get elected and whether voters feel represented or become disillusioned with the peaceful process of democracy can also be affected by electoral-system design. Thus postconflict countries often redesign electoral institutions. For example, a major plank of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that ended the Troubles in Northern Ireland involved introducing a type of ranked-choice voting with multimember districts to increase a sense of representation. There are organizations in the United States today that are advocating various reform measures—for example, eliminating primaries and introducing forms of ranked-choice voting or requiring lawmakers to win a majority of votes to be elected (currently the case in only a handful of states)—that could result in fewer extremists gaining power while increasing voter satisfaction and representation.

Fairer policing and accountability: Even in contexts of high polarization, external deterrence and societal norms generally keep people from resorting to political violence. Partisans who are tempted to act violently should know that they will be held accountable, even if their party is in power. Minority communities, meanwhile, need assurance that the state will defend them.

A number of police-reform measures could help. Police training in de-escalation techniques and nonviolent protest and crowd control, support for officers under psychological strain, improved intelligence collection and sharing regarding domestic threats, and more-representative police forces would all help deter both political violence and police brutality. Publicizing such efforts would demonstrate to society that the government will not tolerate political violence.

Meanwhile, swift justice for violence, incitement, and credible threats against officials—speedy jail sentences, for instance, even if short—is also crucial for its signaling and deterrent value. So are laws that criminalize harassment, intimidation, and political violence.

Prevention and redirection: Lab experiments have found that internal norms can be reinforced by “inoculating” individuals with warnings that people may one day try to indoctrinate them to extremist beliefs or recruit them to participate in acts of political violence. Because no one likes to be manipulated, the forewarned organize their mental defenses against it. The technique seems promising for preventing younger people from radicalization, though it requires more testing among older partisans whose beliefs are strongly set. 35

A significant portion of those engaged in far-right violence are also under mental distress. People searching online for far-right violent extremist content are 115 percent more likely to click on mental-health ads; those undertaking planned hate crimes show greater signs of mental illness than does the general offender population. 36 Groups such as Moonshot CVE are experimenting with targeted ads that can redirect people searching for extremist content toward hotlines for depression and loneliness and help for leaving violent groups.

Political speech: When political leaders denounce violence from their own side, partisans listen. Experiments using quotes from Biden and Trump show that leaders’ rhetoric has the power to de-escalate and deter violence—if they are willing to speak against their own side. 37

Long-term trends in social and political-party organization, isolation, distrust, and inequality, capped by a pandemic, have placed individual psychological health and social cohesion under immense strain. Kalmoe and Mason’s surveys found that in February 2021, a fifth of Republicans and 13 percent of Democrats—or more than 65 million people—believed immediate violence was justified. Even if only a tiny portion are serious, such large numbers put a country at risk of stochastic terrorism—that is, it becomes statistically near certain that someone (though it is impossible to predict who) somewhere will act if a public figure incites violence.

Thus while social factors may have created the conditions, politicians have the match to light the tinder. In recent years, some candidates on the right have been particularly willing to use violent speech and engage with groups that spread hate. Yet Democrats are not immune to these trends. Far-left violence is far lower than on the right, but rising. The firearm industry’s trade association found that, in 2020, 40 percent of all legal gun sales were to first-time buyers, and 58 percent of those five-million new owners were women and African Americans. 38 Kalmoe and Mason’s February 2020 polling found that 11 percent of Democrats and 12 percent of Republicans agreed that it was at least “a little” justified to kill opposing political leaders to advance their own political goals. With both the left and the right increasingly armed, viewing the other side as evil or subhuman, and believing political violence to be justified, the possibility grows of tit-for-tat street warfare, like the clashes between antifascist protesters and Proud Boys in Portland, Oregon, from 2020 through this writing. If Democrats have been less likely to act on these beliefs, it is likely because Democratic politicians have largely and vocally spoken out against violence.

Although political violence in the United States is on the rise, it is still lower than in many other countries. Once violence begins, however, it fuels itself. Far from making people turn away in horror, political violence in the present is the greatest factor normalizing it for the future. Preventing a downward spiral is therefore imperative.

1. “Election Officials Under Attack: How to Protect Administrators and Safeguard Democracy,” Brennan Center for Justice, 16 June 2021, www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/BCJ-129%20ElectionOfficials_v7.pdf ; “Documenting and Addressing Harassment of Election Officials,” California Voter Foundation, June 2021, www.calvoter.org/sites/default/files/cvf_addressing_harassment_of_election_officials_report.pdf ; Zach Montellaro, “‘Center of the Maelstrom’: Election Officials Grapple with 2020’s Long Shadow,” Politico, 18 August 2021.

2. See the Global Terrorism Database maintained by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland, the dataset of extremist far-right violent incidents maintained by Arie Perliger at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, and FBI data on hate crimes.

3. Robert O’Harrow, Jr., Andrew Ba Tran, and Derek Hawkins, “The Rise of Domestic Extremism in America,” Washington Post, 12 April 2021.

4. Robert Pape and the Chicago Project on Security and Threats, “Understanding American Domestic Terrorism: Mobilization Potential and Risk Factors of a New Threat Trajectory” (presentation, University of Chicago, 6 April 2021), https://d3qi0qp55mx5f5.cloudfront.net/cpost/i/docs/americas_insurrectionists_online_2021_04_06.pdf?mtime=1617807009.

5. Daniel A. Cox, “Social Isolation and Community Disconnection Are Not Spurring Conspiracy Theories,” Survey Center on American Life, 4 March 2021, www.americansurveycenter.org/research/social-isolation-and-community-disconnection-are-not-spurring-conspiracy-theories ; Paul A. Djupe and Ryan P. Burge, “A Conspiracy at the Heart of It: Religion and Q,” Religion in Public blog, 6 November 2020, https://religioninpublic.blog/2020/11/06/a-conspiracy-at-the-heart-of-it-religion-and-q .

6. Daniel A. Cox, “After the Ballots Are Counted: Conspiracies, Political Violence, and American Exceptionalism,” Survey Center on American Life, 11 February 2021, www.americansurveycenter.org/research/after-the-ballots-are-counted-conspiracies-political-violence-and-american-exceptionalism ; Larry M. Bartels, “Ethnic Antagonism Erodes Republicans’ Commitment to Democracy,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (September 2020): 22752–59.

7. Nathan P. Kalmoe and Lilliana Mason, Radical American Partisanship: Mapping Violent Hostility, Its Causes, and the Consequences for Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming [2022]), 105, 109.

8. Daniel A. Cox, “Support for Political Violence Among Americans Is on the Rise. It’s a Grim Warning About America’s Political Future,” American Enterprise Institute, 26 March 2021, www.aei.org/op-eds/support-for-political-violence-among-americans-is-on-the-rise-its-a-grim-warning-about-americas-political-future ; Bartels, “Ethnic Antagonism Erodes Republicans’ Commitment to Democracy”; Sonia Roccas and Marilynn B. Brewer, “Social Identity Complexity,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 6 (May 2002): 86–102.

9. Susan Olzak, “The Political Context of Competition: Lynching and Urban Racial Violence, 1882–1914,” Social Forces 69 (December 2020): 395–421; Ryan Hagen, Kinga Makovi, and Peter Bearman, “The Influence of Political Dynamics on Southern Lynch Mob Formation and Lethality,” Social Forces 92 (December 2013): 757-87.

10. Brad Epperly, Christopher Witko, Ryan Strickler, and Paul White, “Rule by Violence, Rule by Law: Lynching, Jim Crow, and the Continuing Evolution of Voter Suppression in the U.S.,” Perspectives on Politics 18 (September 2020): 756-69.

11. Sarah Birch, Ursula Daxecker, and Kristine Hӧglund, “Electoral Violence: An Introduction,” Journal of Peace Research 57 (January 2020): 3–14.

12. Steven I. Wilkinson, Votes and Violence: Electoral Competition and Ethnic Riots in India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

13. Frances E. Lee, Insecure Majorities : Congress and the Perpetual Campaign (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

14. Lilliana Mason, Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

15. Tyler T. Reny, Loren Collingwood, and Ali A. Valenzuela, “Vote Switching in the 2016 Election: How Racial and Immigration Attitudes, Not Economics, Explain Shifts in White Voting,” Public Opinion Quarterly 83 (Spring 2019): 91–113; John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck, Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

16. Bruce Stokes, “What It Takes to Truly Be ‘One of Us,’” Pew Research Center, 1 February 2017, www.pewresearch.org/global/2017/02/01/what-it-takes-to-truly-be-one-of-us ; Emily Ekins, “The Five Types of Trump Voters: Who They Are and What They Believe,” Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, June 2017, www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/the-five-types-trump-voters .

17. Costas Panagopoulos, “All About That Base: Changing Campaign Strategies in U.S. Presidential Elections,” Party Politics 22 (March 2016): 179–90.

18. Pablo Fajnzylber, Daniel Lederman, and Norman Loayza, “Inequality and Violent Crime,” Journal of Law and Economics 45 (April 2002): 1–39; James V. P. Check, Daniel Perlman, and Neil M. Malamuth, “Loneliness and Aggressive Behavior,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2 (September 1985): 243–52; Mark Schaller and Justin H. Park, “The Behavioral Immune System (and Why It Matters),” Current Directions in Psychological Science 20 (April 2011): 99–103.

19. Eitan Hersh and Laura Royden, “Antisemitic Attitudes Across the Ideological Spectrum,” 9 April 2021, unpubl ms., www.eitanhersh.com/uploads/7/9/7/5/7975685/hersh_royden_antisemitism_040921.pdf .

20. Kalmoe and Mason, Radical American Partisanship ; Noelle Malvar et al., “Democracy for President: A Guide to How Americans Can Strengthen Democracy During a Divisive Election,” More in Common, October 2020, https://democracyforpresident.com/topics/election-violence.

21. The Democracy Fund’s 2019 VOTER Survey shows 10-point gaps for each in December 2019; however, monthly Kalmoe and Mason polling shows no gap, and Bright Line Watch polling in 2020 shows splits of less than 6 and 3 percent for identically worded questions.

22. Kalmoe and Mason, Radical American Partisanship, 83–90.

23. Bartels, “Ethnic Antagonism Erodes Republicans’ Commitment to Democracy”; Cox, “Support for Political Violence.”

24. Kalmoe and Mason, Radical American Partisanship, 86.

25. Kalmoe and Mason, Radical American Partisanship, 164, 90.

26. Arie Perliger, “Terror Isn’t Always a Weapon of the Weak—It Can Also Support the Powerful,” The Conversation, 28 October 2018, https://theconversation.com/terror-isnt-always-a-weapon-of-the-weak-it-can-also-support-the-powerful-82626 .

27. Ken Menkhaus, Conflict Assessment: Northern Kenya and Somaliland (Copenhagen: Danish Deming Group, 2015), 42; Thad Dunning, “Fighting and Voting: Violent Conflict and Electoral Politics,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55 (June 2011): 327–39.

28. Arie Perliger, “Why Do Hate Crimes Proliferate in Progressive Blue States?” Medium, 20 August 2020, https://medium.com/3streams/why-hate-crimes-proliferate-in-progressive-blue-state-72483b2d72a7 ; Pape and Chicago Project, “Understanding American Domestic Terrorism.”

29. Martin Pugh, “The British Union of Fascists and the Olympia Debate,” Historical Journal 41 (June 1998): 529–42.

30. Gavin Evans, “Why Political Killings Have Taken Hold—Again—In South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal,” The Conversation, 10 August 2020, https://theconversation.com/why-political-killings-have-taken-hold-again-in-south-africas-kwazulu-natal-143908 .

31. G. Bingham Powell, Jr., “Party Systems and Political System Performance: Voting Participation, Government Stability and Mass Violence in Contemporary Democracies,” American Political Science Review 75, no. 4 (1981): 861–79; Hanne Fjelde and Kristine Höglund, “Electoral Institutions and Electoral Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa,” British Journal of Political Science 46 (April 2016): 297–320.

32. Quinn Scanlan, “10 New State Laws Shift Power Over Elections to Partisan Entities,” ABC News, 16 August 2021, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/dozen-state-laws-shift-power-elections-partisan-entities/story?id=79408455 ; “Democracy Crisis Report Update: New Data and Trends Show the Warning Signs Have Intensified in the Last Two Months,” States United Democracy Center, Protect Democracy, and Law Forward, 10 June 2021, https://statesuniteddemocracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Democracy-Crisis-Part-II_June-10_Final_v7.pdf .

33. Phillip Bump, “Police Made a Lot More Contributions in 2020 Than Normal—Mostly to Republicans,” Washington Post, 25 February 2021.

34. Wilkinson, Votes and Violence.

35. Kurt Braddock, “Vaccinating Against Hate: Using Inoculation to Confer Resistance to Persuasion by Extremist Propaganda,” Terrorism and Political Violence (2019), 1–23.

36. “Mental Health and Violent Extremism,” Moonshot CVE, 28 June 2018, https://moonshotteam.com/mental-health-violent-extremism ; Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) dataset, Global Terrorism Database.

37. Kalmoe and Mason, Radical American Partisanship, 180-87; Matthew A. Baum and Tim Groeling, “Shot by the Messenger: Partisan Cues and Public Opinion Regarding National Security and War,” Political Behavior 31 (June 2009): 157–86; Susan Birch and David Muchlinski, “Electoral Violence Prevention: What Works?” Democratization 25 (April 2018): 385–403.

38. “First-Time Gun Buyers Grow to Nearly 5 Million in 2020,” Fire Arms Industry Trade Association, 24 August 2020, www.nssf.org/articles/first-time-gun-buyers-grow-to-nearly-5-million-in-2020 .

Copyright © 2021 National Endowment for Democracy and Johns Hopkins University Press

Image Credit: lev radin/Shutterstock.com.

Further Reading

Volume 35, Issue 2

America’s Crisis of Civic Virtue

- Arthur C. Brooks

The problem for democracy today is not capitalism; it is a decline in public honesty and civility. But there is an opportunity to revive our sense of national community, if…

Volume 35, Issue 4

Liberal Democracy in an Age of Immigration

- Rafaela Dancygier

Immigration threatens to erode liberalism, as far-right parties and migrant communities with illiberal views gain power. Mass publics have shouldered the blame. But should political elites be held responsible?

The Liberalism of Refuge

- Bryan Garsten

Liberal societies are those which offer refuge from the very people they empower—through individual choice, mobility, and the possibility of exit. This is the form of liberty that most clearly…

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Corrections

- Crime, Media, and Popular Culture

- Criminal Behavior

- Criminological Theory

- Critical Criminology

- Geography of Crime

- International Crime

- Juvenile Justice

- Prevention/Public Policy

- Race, Ethnicity, and Crime

- Research Methods

- Victimology/Criminal Victimization

- White Collar Crime

- Women, Crime, and Justice

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Political corruption and state crime.

- Clayton Peoples Clayton Peoples Department of Social Psychology, University of Nevada, Reno

- , and James E. Sutton James E. Sutton Department of Anthropology and Sociology, Hobart and William Smith Colleges

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.274

- Published online: 26 April 2017

The state is responsible for maintaining law and order in society and protecting the people. Sometimes it fails to fulfill these responsibilities; in other cases, it actively harms people. There have been many instances of political corruption and state crime throughout history, with impacts that range from economic damage to physical injury to death—sometimes on a massive scale (e.g., economic recession, pollution/poisoning, genocide). The challenge for criminologists, however, is that defining political corruption and state crime can be thorny, as can identifying their perpetrators—who can often be collectives of individuals such as organizations and governments—and their victims. In turn, pinpointing appropriate avenues of controlling these crimes can be difficult. These challenges are exacerbated by power issues and the associated reality that the state is in a position to write or change laws and, in essence, regulate itself. One possible solution is to define political corruption and state crime—as well as their perpetrators and victims—as broadly as possible to include a variety of scenarios that may or may not exhibit violations of criminal law. Likewise, a resolution to the issue of social control would be to move beyond strictly institutional mechanisms of control. Criminological research should further elucidate these issues; it should also, however, move beyond conceptual dilemmas toward (a) better understanding the processes underlying political corruption/state crime and (b) illustrating the broader ramifications of these crimes.

- political corruption

- state crime

- state-corporate crime

- white collar crime

- corporate crime

- official deviance

- organizational deviance

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Criminology and Criminal Justice. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 14 November 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.150.64]

- 185.80.150.64

Character limit 500 /500

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Current research overstates American support for political violence

Sean j westwood, justin grimmer, matthew tyler, clayton nall.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

To whom correspondence may be addressed. Email: [email protected] .

Edited by Anthony Fowler, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL; received September 15, 2021; accepted February 7, 2022 by Editorial Board Member Margaret Levi

Author contributions: S.J.W. designed research; S.J.W., J.G., and M.T. performed research; M.T. and C.N. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; S.J.W. analyzed data; and S.J.W. and J.G. wrote the paper.

Accepted 2022 Feb 7; Issue date 2022 Mar 22.

This open access article is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND) .

Significance

Recent political events show that members of extreme political groups support partisan violence, and survey evidence supposedly shows widespread public support. We show, however, that, after accounting for survey-based measurement error, support for partisan violence is far more limited. Prior estimates overstate support for political violence because of random responding by disengaged respondents and because of a reliance on hypothetical questions about violence in general instead of questions on specific acts of political violence. These same issues also cause the magnitude of the relationship between previously identified correlates and partisan violence to be overstated. As policy makers consider interventions designed to dampen support for violence, our results provide critical information about the magnitude of the problem.

Keywords: political violence, affective polarization, democratic norms

Political scientists, pundits, and citizens worry that America is entering a new period of violent partisan conflict. Provocative survey data show that a large share of Americans (between 8% and 40%) support politically motivated violence. Yet, despite media attention, political violence is rare, amounting to a little more than 1% of violent hate crimes in the United States. We reconcile these seemingly conflicting facts with four large survey experiments ( n = 4,904), demonstrating that self-reported attitudes on political violence are biased upward because of respondent disengagement and survey questions that allow multiple interpretations of political violence. Addressing question wording and respondent disengagement, we find that the median of existing estimates of support for partisan violence is nearly 6 times larger than the median of our estimates (18.5% versus 2.9%). Critically, we show the prior estimates overstate support for political violence because of random responding by disengaged respondents. Respondent disengagement also inflates the relationship between support for violence and previously identified correlates by a factor of 4. Partial identification bounds imply that, under generous assumptions, support for violence among engaged and disengaged respondents is, at most, 6.86%. Finally, nearly all respondents support criminally charging suspects who commit acts of political violence. These findings suggest that, although recent acts of political violence dominate the news, they do not portend a new era of violent conflict.

Provocative recent work ( 1 – 3 )—cited in PNAS ( 4 , 5 ), The American Journal of Political Science ( 6 ), 60 other articles and books, and 40 news articles that, together, have garnered over 2,281,133 Twitter engagements—asserts that large segments of the American population now support politically motivated violence. These studies report that up to 44% of Americans would endorse hypothetical violence in some undetermined future event ( 1 – 3 , 7 ). This survey work fits within a media landscape that regularly raises the specter of political violence. Since 2016, we counted 2,863 mentions of political violence on news television, more than 630 news stories about political violence, and over 10 million tweets on the topic of the January 6 riot alone (see SI Appendix , section 1 for details for all counts in this paragraph). Political violence, however, remains exceedingly rare in the United States, amounting to 48 incidents ( 8 ) in 2019 (the most recent year for which data are available) compared to 4,526 incidents of nonpolitical violent hate crimes ( 9 ) and 1,203,808 total violent crimes ( 10 ) documented by the Department of Justice.

In this paper, we reconcile supposedly significant public support for political violence with minimal actual instances of violent political action. To do this, we use four survey experiments that assess respondents’ reactions to specific acts of violence, where we experimentally manipulate whether partisanship motivated the activity and the severity of the violence. Using these studies, we identify two reasons why current survey data overestimate support for political violence in the United States.

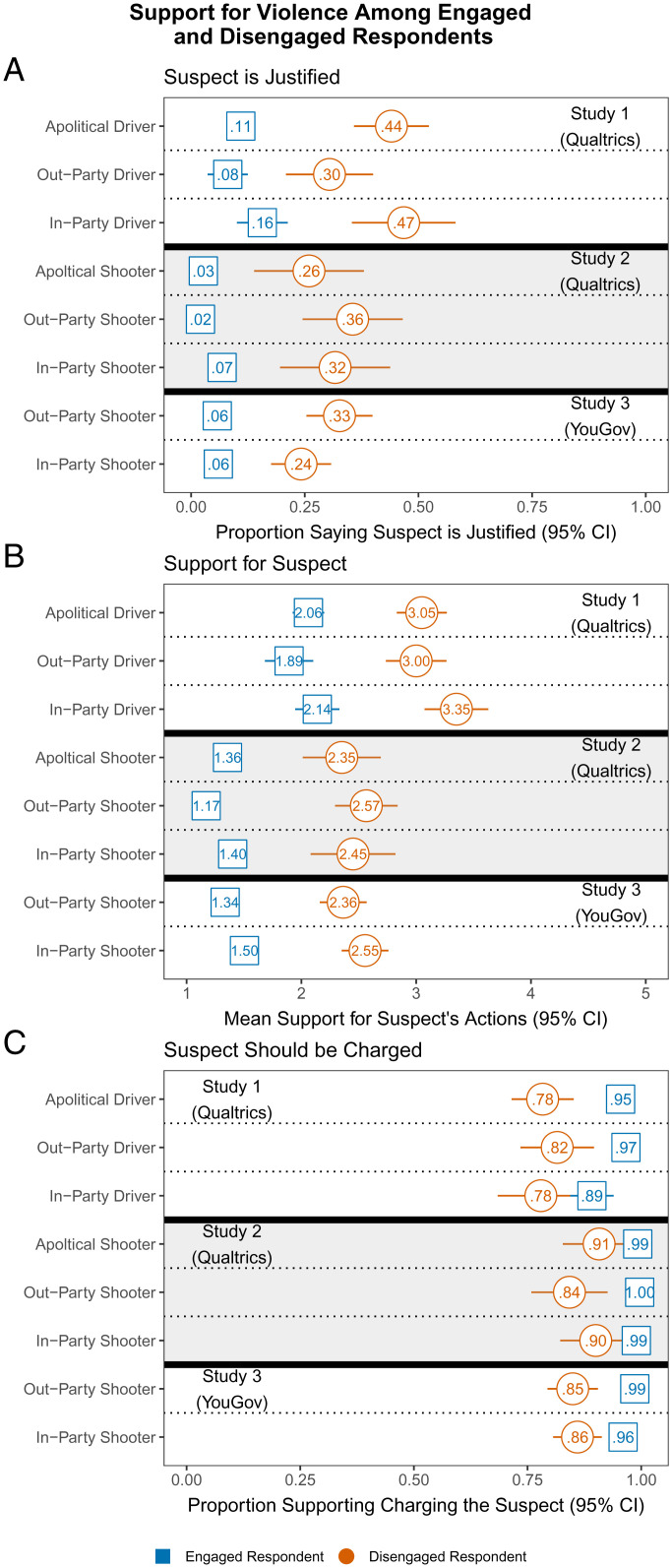

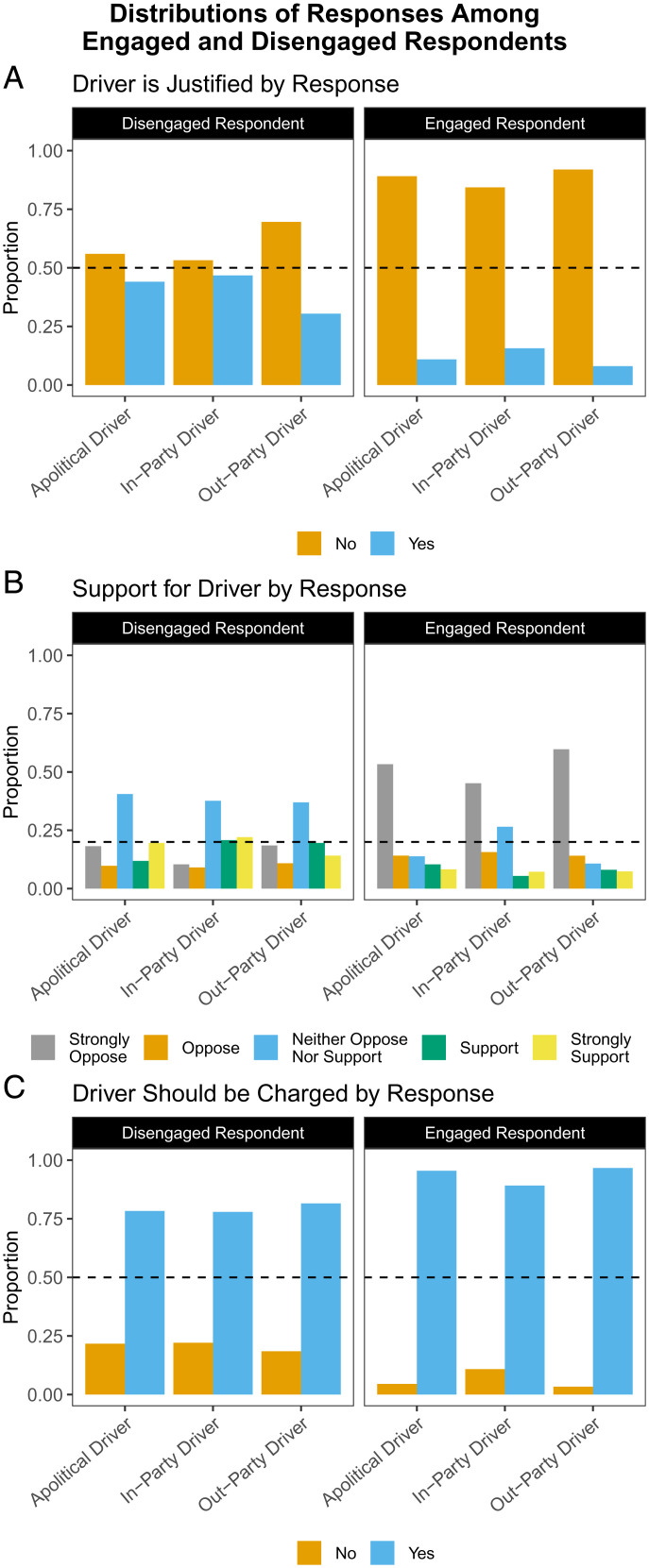

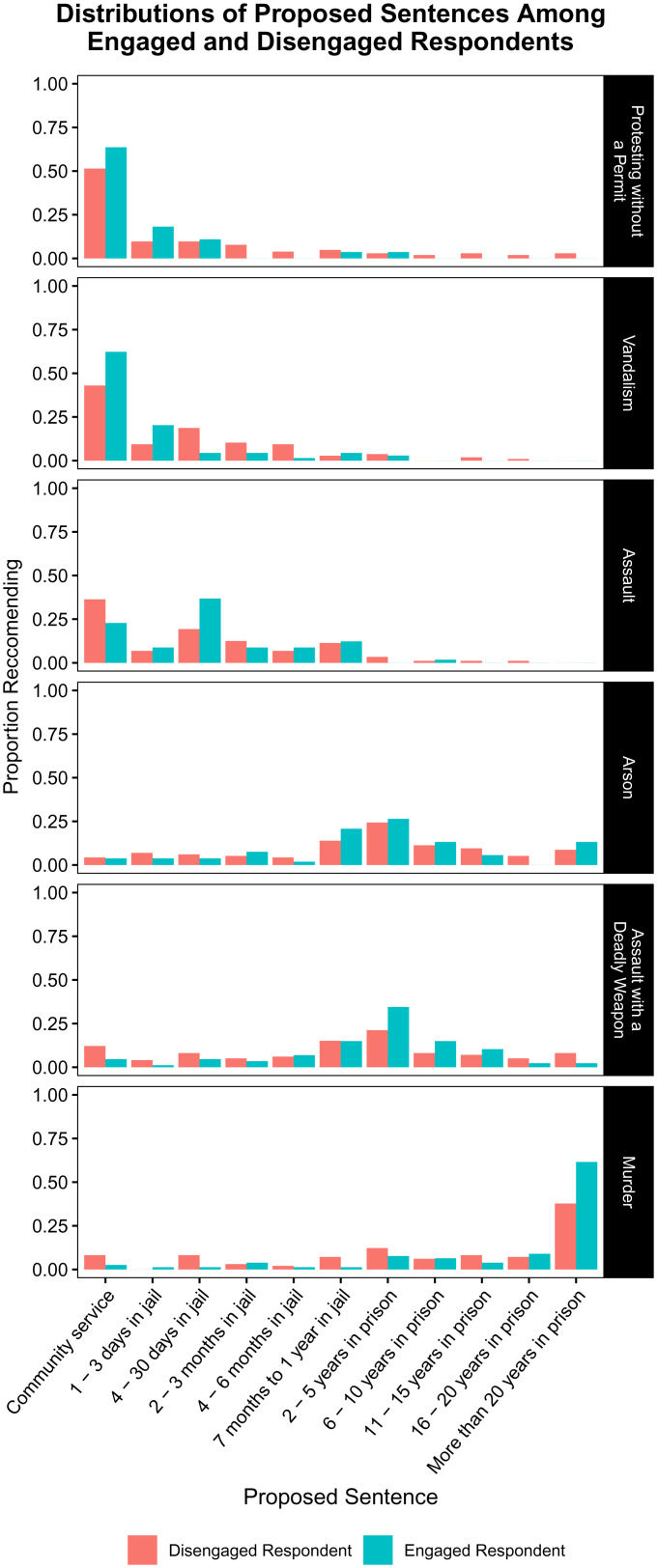

First, ambiguous survey questions cause overestimates of support for violence. Prior studies ask about general support for violence without offering context, leaving the respondent to infer what “violence” means. Using detailed treatments and precisely worded survey questions, we resolve this ambiguity and reveal that support for violence varies substantially depending on the severity of the specific violent act. With our measures, assault and murder attract minimal support, while low-level property crimes gain higher (although still low) support. Moreover, even though segments of the public may support violence or report that it is justified in the abstract, nearly all respondents still believe that perpetrators of well-defined instances of severe political violence should be criminally charged.

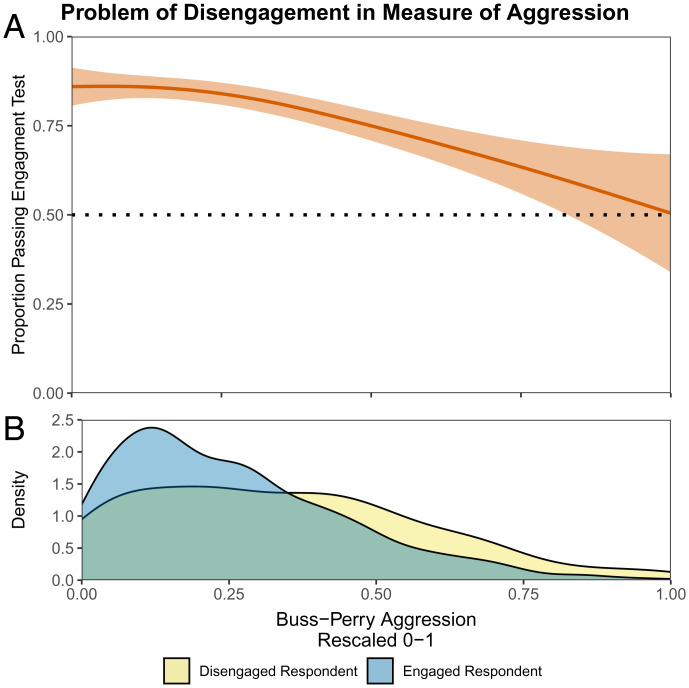

Second, disengaged survey respondents cause an upward bias in reported support for violence. Prior survey questions force respondents to select a response without providing a neutral midpoint or a “don’t know” option. This causes disengaged respondents—satisficers ( 11 )—to select an arbitrary or random response ( 12 ). Current violence support scales are coded such that four of five choices indicate acceptance of violence. In the presence of arbitrary responding, such a scale will overstate support for violence. Across all four studies, we show that disengaged respondents report higher support for violence.

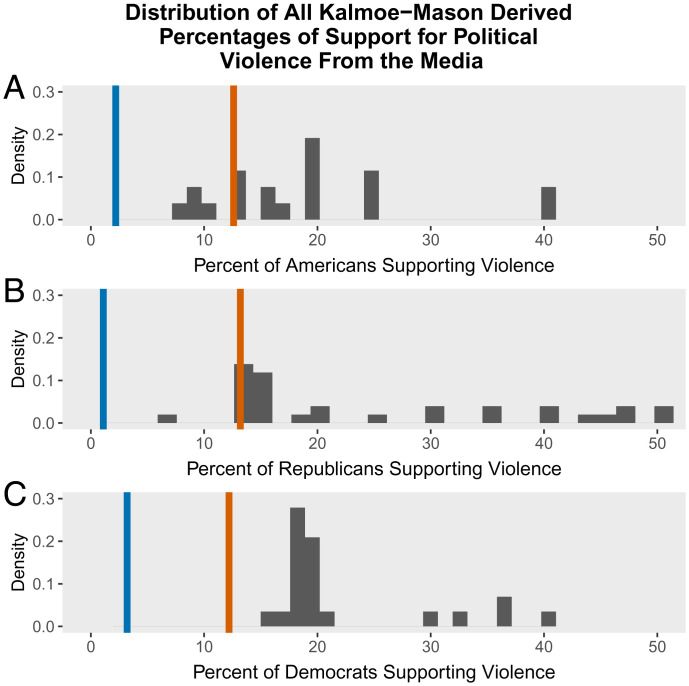

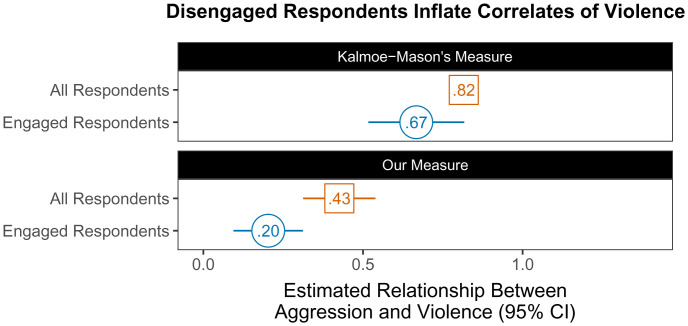

Accounting for these sources of error, our four studies show that American support for political violence is less intense than prior work asserts ( Fig. 1 ) and is contingent on the severity of the violent act. Depending on how the question is asked, we show that the median of existing estimates of the public’s support for partisan violence is nearly 6 times larger than the median of our estimates (18.5% versus 2.9%). While recent political events show that extreme political groups are willing to engage in violence, these groups are likely to overlap with the narrow segment of the population who already support political violence. As policy makers consider interventions designed to dampen support for violence, our results demonstrate that support for violence is not a mass phenomenon, indicating that antiviolence measures should be appropriately tailored to match the scale of the problem.

We created a census of all reported estimates of support for violence using the Kalmoe–Mason measure in the media (this includes work done by authors other than Kalmoe and Mason). This figure shows their distribution. We report this in the full sample ( A ), for Republicans ( B ), and for Democrats ( C ). To contextualize the problems, in these estimates, we overlay the largest estimates (orange line) and smallest estimates (blue line) from the studies that follow. There is large variation in the reported values, but all are significantly larger than our preferred estimate. See SI Appendix for additional details.

Support for Partisan Violence Is Lower than Previously Reported

Partisan animosity, often referred to as affective polarization ( 13 ), has increased significantly over the last 30 y. While Americans are arguably no more ideologically polarized than in the recent past, they hold more-negative views toward the political opposition and more-positive views toward members of their own party. This pattern has been documented across several measures of animosity and has raised alarm among scholars across disciplines about the potential consequences of growing partisan discord (e.g., ref. 14 ). Numerous studies have documented the negative interpersonal, “apolitical” ( 15 ) consequences of affective polarization, including politically based discrimination against job applicants ( 16 ), prospective romantic partners ( 17 ), workers ( 18 ), and even scholarship recipients (for a review, see ref. 13 ). These findings have created substantial concerns over partisan animosity’s pervasive effects on American social life ( 19 ).

Yet, evidence suggests that affective polarization is not related to and does not cause increases in support for political violence ( 20 , 21 ) and is generally unrelated to political outcomes ( 21 , 22 ). Moreover, partisan violence appears to be unrelated to many other political variables ( 2 ). We are therefore left with a phenomenon that is not explained by the current literature on partisan animosity, that is rarely observed in the world, but that is based on prior work supported by a near majority of the American population ( 1 – 3 ).

We show that documented support for political violence is illusory, a product of ambiguous questions and disengaged respondents. We now explain how each causes political violence to appear more popular than it is in the public.

Ambiguous Questions Create Upward Bias in Estimates of Support for Violence.