Free Will, Determinism, and Moral Responsibility

--> Arthurs, Frank (2014) Free Will, Determinism, and Moral Responsibility. PhD thesis, University of Sheffield.

The first half of this thesis is a survey of the PSR, followed by consideration of arguments for and against the principle. This survey spans from the Ancient Greeks to the present day, and gives the reader a sense of the ways in which the PSR has been used both implicitly and explicitly throughout the history of philosophy. I argue that, while none of the arguments either for or against the PSR provide conclusive evidence of its truth or falsity, we should adopt a presumption in its favour. The best hope the PSR sceptic has of demonstrating the PSR’s falsity would be to find empirical evidence of something non-deterministic, since the PSR entails determinism. The theory of libertarianism is considered as just such a counterexample; but I argue the evidence for libertarianism is flimsy, and so the presumption in favour of the PSR remains. The second half starts from the premise that the PSR—and hence also determinism—is true, and goes on to examine what implications this has for our moral responsibility practices. We examine incompatibilist arguments by van Inwagen and Galen Strawson, both of which appeal to the origination condition. I contend that these arguments are compelling precisely because the origination condition to which they appeal is compelling. This leaves us with a dilemma: it seems like we can either accept these incompatibilist arguments, which would require us to abandon our moral responsibility practices; or we could save our moral responsibility practices by adopting some form of compatibilism, but at the cost of denying the intuitively appealing origination condition. In fact, to avoid the costs of each horn of this dilemma, we can seek to create a ‘mixed view’ instead. We consider Vargas’s revisionism, Double’s free will subjectivism, and Smilansky’s illusionism and fundamental dualism, which help to shape the mixed view I argue for here: a consequentialist compatibilist theory of moral responsibility. This theory allows us to acknowledge the impossibility of true desert without dispensing with our responsibility practices.

--> Philosophy PhD on Ethics and Metaphysics -->

Filename: PhD - Free Will, Determinism, and Moral Responsibility. Complete pdf File..pdf

Description: Philosophy PhD on Ethics and Metaphysics

Embargo Date:

You do not need to contact us to get a copy of this thesis. Please use the 'Download' link(s) above to get a copy. You can contact us about this thesis . If you need to make a general enquiry, please see the Contact us page.

Free Will (Philosophy)

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

- pp 3237–3240

- Cite this reference work entry

- Matthew A Sarraf 3

11 Accesses

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Caruso, G. D. (2013). Free will and consciousness: A determinist account of the illusion of free will . Landham: Lexington Books.

Google Scholar

Dennett, D. C. (2015). Elbow room: The varieties of free will worth wanting . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Book Google Scholar

Horst, S. W. (2011). Laws, mind, and free will . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McKenna, M., & Pereboom, D. (2016). Free will: A contemporary introduction . New York: Routledge.

Mele, A. R. (2006). Free will and luck . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[Moscow Center for Consciousness Studies]. (2014). Greenland 2014 Dennett on Pereboom . [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cN7cEDPgMek

Pereboom, D. (2016). Free will, agency, and meaning in life . New York: Oxford University Press.

Sartorio, C. (2016). Causation and free will . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Strawson, G. (1986). Freedom and belief . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA

Matthew A Sarraf

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Matthew A Sarraf .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Todd K Shackelford

Viviana A Weekes-Shackelford

Section Editor information

Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA

Karin Machluf

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Sarraf, M.A. (2021). Free Will (Philosophy). In: Shackelford, T.K., Weekes-Shackelford, V.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_2167

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_2167

Published : 22 April 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-19649-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-19650-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Chapter 5: The problem of free will and determinism

The problem of free will and determinism

Matthew Van Cleave

“You say: I am not free. But I have raised and lowered my arm. Everyone understands that this illogical answer is an irrefutable proof of freedom.”

-Leo Tolstoy

“Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills.”

-Arthur Shopenhauer

“None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.”

-Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

The term “freedom” is used in many contexts, from legal, to moral, to psychological, to social, to political, to theological. The founders of the United States often extolled the virtues of “liberty” and “freedom,” as well as cautioned us about how difficult they were to maintain. But what do these terms mean, exactly? What does it mean to claim that humans are (or are not) free? Almost anyone living in a liberal democracy today would affirm that freedom is a good thing, but they almost certainly do not all agree on what freedom is. With a concept as slippery as that of free will, it is not surprising that there is often disagreement. Thus, it will be important to be very clear on what precisely we are talking about when we are either affirming or denying that humans have free will. There is an important general point here that extends beyond the issue of free will: when debating whether or not x exists, we must first be clear on defining x, otherwise we will end up simply talking past each other . The philosophical problem of free will and determinism is the problem of whether or not free will exists in light of determinism. Thus, it is crucial to be clear in defining what we mean by “free will” and “determinism.” As we will see, these turn out to be difficult and contested philosophical questions. In this chapter we will consider these different positions and some of the arguments for, as well as objections to, them.

Let’s begin with an example. Consider the 1998 movie, The Truman Show . In that movie the main character, Truman Burbank (played by Jim Carrey), is the star of a reality television show. However, he doesn’t know that he is. He believes he is just an ordinary person living in an ordinary neighborhood, but in fact this neighborhood is an elaborate set of a television show in which all of his friends and acquaintances are just actors. His every moment is being filmed and broadcast to a whole world of fans that he doesn’t know exists and almost every detail of his life has been carefully orchestrated and controlled by the producers of the show. For example, Truman’s little town is surrounded by a lake, but since he has been conditioned to believe (falsely) that he had a traumatic boating accident in which his father died, he never has the desire to leave the small little town and venture out into the larger world (at least at first). So consider the life of Truman as described above. Is he free or not? On the one hand, he gets to do pretty much everything he wants to do and he is pretty happy. Truman doesn’t look like he’s being coerced in any explicit way and if you asked him if he was, he would almost certain reply that he wasn’t being coerced and that he was in charge of his life. That is, he would say that he was free (at least to the same extent that the rest of us would). These points all seem to suggest that he is free. For example, when Truman decides that he would rather not take a boat ride out to explore the wider world (which initially is his decision), he is doing what he wants to do. His action isn’t coerced and does not feel coerced to him. In contrast, if someone holds a gun to my head and tells me “your wallet or your life!” then my action of giving him my wallet is definitely coerced and feels so.

On the other hand, it seems clear the Truman’s life is being manipulated and controlled in a way that undermines his agency and thus his freedom. It seems clear that Truman is not the master of his fate in the way that he thinks he is. As Goethe says in the epigraph at the beginning of this chapter, there’s a sense in which people like Truman are those who are most helplessly enslaved, since Truman is subject to a massive illusion that he has no reason to suspect. In contrast, someone who knows she is a slave (such as slaves in the antebellum South in the United States) at least retains the autonomy of knowing that she is being controlled. Truman seems to be in the situation of being enslaved and not knowing it and it seems harder for such a person to escape that reality because they do not have any desire to (since they don’t know they are being manipulated and controlled).

As the Truman Show example illustrates, it seems there can be reasonable disagreement about whether or not Truman is free. On the one hand, there’s a sense in which he is free because he does what he wants and doesn’t feel manipulated. On the other hand, there’s a sense in which he isn’t free because what he wants to do is being manipulated by forces outside of his control (namely, the producers of the show). An even better example of this kind of thing comes from Aldous Huxley’s classic dystopia, Brave New World . In the society that Huxley envisions, everyone does what they want and no one is ever unhappy. So far this sounds utopic rather than dystopic. What makes it dystopic is the fact that this state of affairs is achieved by genetic and behavioral conditioning in a way that seems to remove any choice. The citizens of the Brave New World do what they want, yes, but they seems to have absolutely no control over what they want in the first place. Rather, their desires are essentially implanted in them by a process of conditioning long before they are old enough to understand what is going on. The citizens of Brave New World do what they want, but they have no control over what the want in the first place. In that sense, they are like robots: they only have the desires that are chosen for them by the architects of the society.

So are people free as long as they are doing what they want to—that is, choosing the act according to their strongest desires? If so, then notice that the citizens of Brave New World would count as free, as would Truman from The Truman Show , since these are both cases of individuals who are acting on their strongest desires. The problem is that those desires are not desires those individuals have chosen. It feels like the individuals in those scenarios are being manipulated in a way that we believe we aren’t. Perhaps true freedom requires more than just that one does what one most wants to do. Perhaps true freedom requires a genuine choice. But what is a genuine choice beyond doing what one most wants to do?

Philosophers are generally of two main camps concerning the question of what free will is. Compatibilists believe that free will requires only that we are doing what we want to do in a way that isn’t coerced—in short, free actions are voluntary actions. Incompatibilists , motivated by examples like the above where our desires are themselves manipulated, believe that free will requires a genuine choice and they claim that a choice is genuine if and only if, were we given the choice to make again, we could have chosen otherwise . I can perhaps best crystalize the difference between these two positions by moving to a theological example. Suppose that there is a god who created the universe, including humans, and who controls everything that goes on in the universe, including what humans do. But suppose that god does this not my directly coercing us to do things that we don’t want to do but, rather, by implanting the desire in us to do what god wants us to do. Thus human beings, by doing what the want to do, would actually be doing what god wanted them to do. According to the compatibilist, humans in this scenario would be free since they would be doing what they want to do. According to the incompatibilist, however, humans in this scenario would not be free because given the desire that god had implanted in them, they would always end up doing the same thing if given the decision to make (assuming that desires deterministically cause behaviors). If you don’t like the theological example, consider a sci-fi example which has the same exact structure. Suppose there is an eccentric neuroscientist who has figured out how to wire your brain with a mechanism by which he can implant desire into you.

Suppose that the neuroscientist implants in you the desire to start collecting stamps and you do so. However, you know none of this (the surgery to implant the device was done while you were sleeping and you are none the wiser).

From your perspective, one day you find yourself with the desire to start collecting stamps. It feels to you as though this was something you chose and were not coerced to do. However, the reality is that given this desire that the neuroscientist implanted in you, you could not have chosen not to have started collecting stamps (that is, you were necessitated to start collecting stamps, given the desire). Again, in this scenario the compatibilist would say that your choice to start collecting stamps was free (since it was something you wanted to do and did not feel coerced to you), but the incompatibilist would say that your choice was not free since given the implantation of the desire, you could not have chosen otherwise.

We have not quite yet gotten to the nub of the philosophical problem of free will and determinism because we have not yet talked about determinism and the problem it is supposed to present for free will. What is determinism?

Determinism is the doctrine that every cause is itself the effect of a prior cause. More precisely, if an event (E) is determined, then there are prior conditions (C) which are sufficient for the occurrence of E. That means that if C occurs, then E has to occur. Determinism is simply the claim that every event in the universe is determined. Determinism is assumed in the natural sciences such as physics, chemistry and biology (with the exception of quantum physics for reasons I won’t explain here). Science always assumes that any particular event has some law-like explanation—that is, underlying any particular cause is some set of law- like regularities. We might not know what the laws are, but the whole assumption of the natural sciences is that there are such laws, even if we don’t currently know what they are. It is this assumption that leads scientists to search for causes and patterns in the world, as opposed to just saying that everything is random. Where determinism starts to become contentious is when we move into the human sciences, such as psychology, sociology, and economics. To illustrate why this is contentious, consider the famous example of Laplace’s demon that comes from Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1814:

We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.

Laplace’s point is that if determinism were true, then everything that every happened in the universe, including every human action ever undertaken, had to have happened. Of course humans, being limited in knowledge, could never predict everything that would happen from here out, but some being that was unlimited in intelligence could do exactly that. Pause for a moment to consider what this means. If determinism is true, then Laplace’s demon would have been able to predict from the point of the big bang, that you would be reading these words on this page at this exact point of time. Or that you had what you had for breakfast this morning. Or any other fact in the universe. This seems hard to believe, since it seems like some things that happen in the universe didn’t have to happen. Certain human actions seem to be the paradigm case of such events. If I ate an omelet for breakfast this morning, that may be a fact but it seems strange to think that this fact was necessitated as soon as the big bang occurred. Human actions seem to have a kind of independence from web of deterministic web of causes and effects in a way that, say, billiard balls don’t.

Given that the cue ball his the 8 ball with a specific velocity, at a certain angle, and taking into effect the coefficient of friction of the felt on the pool table, the exact location of the 8 ball is, so to speak, already determined before it ends up there. But human behavior doesn’t seem to be like the behavior of the 8 ball in this way, which is why some people think that the human sciences are importantly different than the natural sciences. Whether or not the human sciences are also deterministic is an issue that helps distinguish the different philosophical positions one can take on free will, as we will see presently. But the important point to see right now is that determinism is a doctrine that applies to all causes, including human actions. Thus, if some particular brain state is what ultimately caused my action and that brain state itself was caused by a prior brain state, and so on, then my action had to occur given those earlier prior events. And that entails that I couldn’t have chosen to act otherwise, given that those earlier events took place . That means that the incompatibilist position on free will cannot be correct if determinism is true. Recall that incompatibilism requires that a choice is free only if one could have chosen differently, given all the same initial conditions. But if determinism is true, then human actions are no different than the 8 ball: given what has come before, the current event had to happen. Thus, if this morning I cooked an omelet, then my “choice” to make that omelet could not have been otherwise. Given the complex web of prior influences on my behavior, my making that omelet was determined. It had to occur.

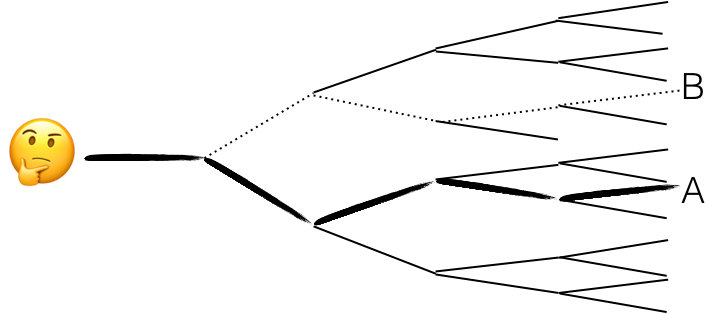

Of course, it feels to us, when contemplating our own futures, that there are many different possible ways our lives might go—many possible choices to be made. But if determinism is true, then this is an illusion. In reality, there is only one way that things could go, it’s just that we can’t see what that is because of our limited knowledge. Consider the figure below. Each junction in the figure below represents a decision I make and let’s suppose that some (much larger) decision tree like this could represent all of the possible ways my life could go. At any point in time, when contemplating what to do, it seems that I can conceive of my life going many different possible ways. Suppose that A represents one series of choices and B another. Suppose, further, that A represents what I actually do (looking backwards over my life from the future). Although from this point in time it seems that I could also have made the series of choices represented in B, if determinism is true then this is false. That is, if A is what ends up happening, then A is the only thing that ever could have happened . If it hasn’t yet hit you how determinism conflicts with our sense of our own possibilities in life, think about that for a second.

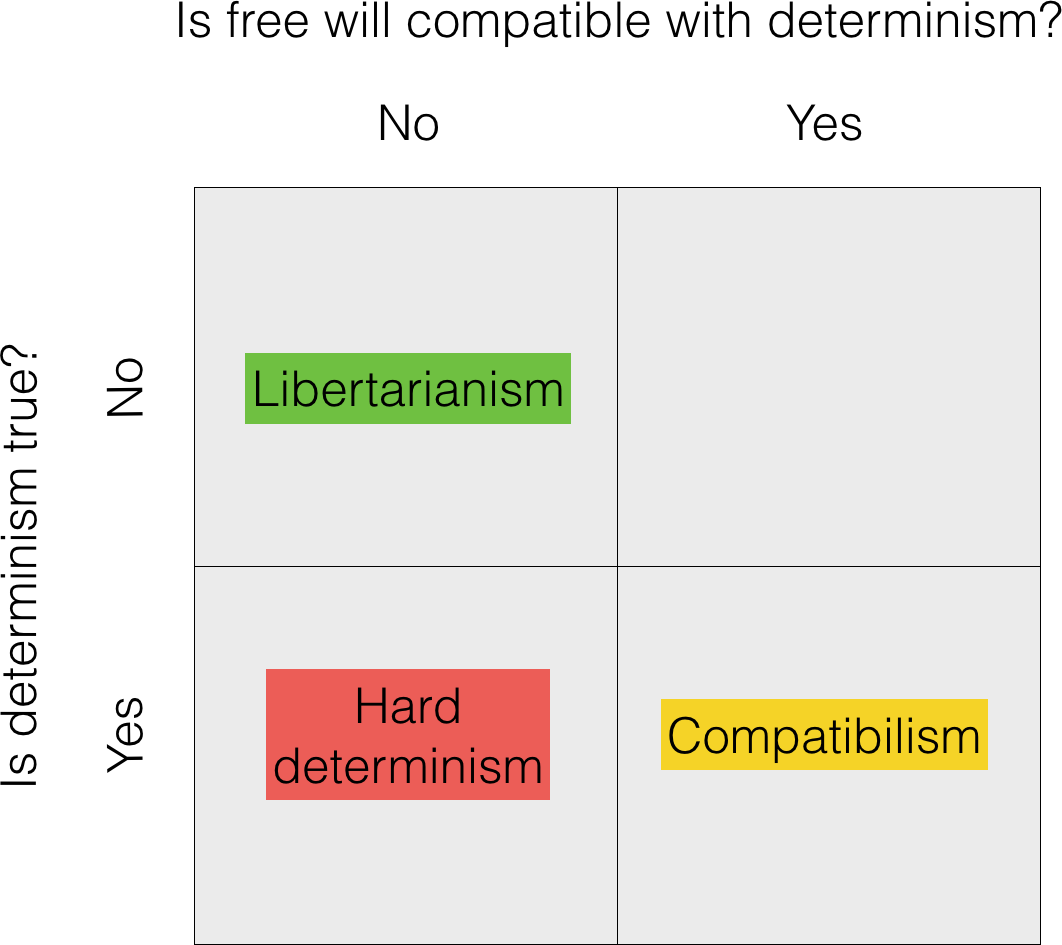

As the foregoing I hope makes clear, the incompatibilist definition of free will is incompatibile with determinism (that’s why it’s called “incompatibilist”). But that leaves open the question of which one is true. To say that free will and determinism are logically incompatible is just to say that they cannot both be true, meaning that one or the other must be false. But which one? Some will claim that it is determinism which is false. This position is called libertarianism (not to be confused with political libertarianism, which is a totally different idea). Others claim that determinism is true and that, therefore, there is no free will. This position is called hard determinism. A third type of position, compatibilism , rejects the incompatibilist definition of freedom and claims that free will and determinism are compatible (hence the name). The table below compares these different positions. But which one is correct? In the remainder of the chapter we will consider some arguments for and against these three positions on free will and determinism.

Libertarianism

Both libertarianism and hard determinism accept the following proposition: If determinism is true, then there is no free will. What distinguishes libertarianism from hard determinism is the libertarian’s claim that there is free will. But why should we think this? This question is especially pressing when we recognize that we assume a deterministic view in many other domains in life. When you have a toothache, we know that something must have caused that toothache and whatever cause that was, something else must have caused that cause. It would be a strange dentist who told you that your toothache didn’t have a cause but just randomly occurred. When the weather doesn’t go as the meteorologist predicts, we assume there must be a cause for why the weather did what it did. We might not ever know the cause in all its specific details, but assume there must be one. In cases like meteorology, when our scientific predictions are wrong, we don’t always go back and try to figure out what the actual causes were—why our predictions were wrong. But in other cases we do. Consider the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1986. Years later it was finally determined what led to that explosion (“O-ring” seals that were not designed for the colder condition of the launch). There’s a detailed deterministic physical explanation that one could give of how the failure of those O-rings led to the explosion of the Challenger. In all of these cases, determinism is the fundamental assumption and it seems almost nothing could overturn it.

But the libertarian thinks that the domain of human action is different than every other domain. Humans are somehow able to rise above all of the influences on them and make decisions that are not themselves determined by anything that precedes them. The philosopher Roderick Chisholm accurately captured the libertarian position when he claimed that “we have a prerogative which some would attribute only to God: each of us, when we really act, is a prime mover unmoved. In doing what we do, we cause certain events to happen, and nothing and no one, except we ourselves, causes us to cause those events to happen” (Chisholm, 1964). But why should we think that we have such a godlike ability? We will consider two arguments the libertarian makes in support of her position: the argument from intuitions and the argument from moral responsibility.

The argument from intuitions is based on the very strong intuition that there are some things that we have control over and that nothing causes us to do those things except for our own willing them. The strongest case for this concerns very simple actions, such as moving one’s finger. Suppose that I hold up my index finger and say that I am going to move it to the right or the to the left, but that I have not yet decided which way to move it. At the moment before I move my finger one way or the other, it truly seems to me that my future is open.

Nothing in my past and nothing in my present seems to be determining me to move my finger to the right or to the left. Rather, it seems to me that I have total control over what happens next. Whichever way I move my finger, it seems that I could have moved it the other way. So if, as a matter of fact, I move my finger to the right, it seems unquestionably true that I could have moved it to the left (and vice versa, mutatis mutandis ). Thus, in cases of simple actions like moving my finger to the right or left, it seems that the strong incompatibilist definition of freedom is met: we have a very strong intuition that no matter what I actually did, I could have chosen otherwise, were I to be given that exact choice again . The libertarian does not claim that all human actions are like this. Indeed, many of our actions (perhaps even ones that we think are free) are determined by prior causes. The libertarian’s claim is just that at least some of our actions do meet the incompatibilist’s definition of free and, thus, that determinism is not universally true.

The argument from moral responsibility is a good example of what philosophers call a transcendental argument . Transcendental arguments attempt to establish the truth of something by showing that that thing is necessary in order for something else, which we strongly believe to be true, to be true. So consider the idea that normally developed adult human beings are morally responsible for their actions. For example, if Bob embezzles money from his charity in order to help pay for a new sports car, we would rightly hold Bob accountable for this action. That is, we would punish Bob and would see punishment as appropriate. But a necessary condition of holding Bob responsible is that Bob’s action was one that he chose, one that he was in control of, one that he could have chosen not to do. Philosophers call this principle ought implies can : if we say that someone ought (or ought not) do something, this implies that they can do it (that is, they are capable of doing it). The ought implies can principle is consistent with our legal practices. For example, in cases where we believe that a person was not capable of doing the right thing, we no longer hold them morally or criminally liable. A good example of this within our legal system is the insanity defense: if someone was determined to be incapable of appreciating the difference between right and wrong, we do not find them guilty of a crime. But notice what determinism would do to the ought implies can principle. If everything we ever do had to happen (think Laplace’s demon), that means that Bob had to embezzle those funds and buy that sports car. The universe demanded it. That means he couldn’t not have done those things. But if that is so, then, by the ought implies can principle, we cannot say that he ought not to have done those things. That is, we cannot hold Bob morally responsible for those things. But this seems absurd, the libertarian will say.

Surely Bob was responsible for those things and we are right to hold him responsible. But the only we way can reasonably do this is if we assume that his actions were chosen—that he could have chosen to do otherwise than he in fact chose. Thus, determinism is incompatible with the idea that human beings are morally responsible agents. The practice of holding each other to be morally responsible agents doesn’t make sense unless humans have incompatibilist free will—unless they could have chosen to do otherwise than they in fact did. That is the libertarian’s transcendental argument from moral responsibility.

Hard determinism

Hard determinism denies that there is free will. The hard determinist is a “tough-minded” individual who bravely accepts the implication of a scientific view of the world. Since we don’t in general accept that there are causes that are not themselves the result of prior causes, we should apply this to human actions too. And this means that humans, contrary to what they might believe (or wish to believe) about themselves, do not have free will. As noted above, hard determininsm follows from accepting the incompatibilist definition of free will as well as the claim that determinism is universally true. One of the strongest arguments in favor of hard determinism is based on the weakness of the libertarian position. In particular, the hard determinist argues that accepting the existence of free will leaves us with an inexplicable mystery: how can a physical system initiate causes that are not themselves caused?

If the libertarian is right, then when an action is free it is such that given exactly the same events leading up to one’s action, one still could have acted otherwise than they did. But this seems to require that the action/choice was not determined by any prior event or set of events. Consider my decision to make a cheese omelet for breakfast this morning. The libertarian will say that my decision to make the cheese omelet was not free unless I could have chosen to do otherwise (given all the same initial conditions). But that means that nothing was determining my decision. But what kind of thing is a decision such that it causes my actions but is not itself caused by anything? We do not know of any other kind of thing like this in the universe. Rather, we think that any event or thing must have been caused by some (typically complex) set of conditions or events. Things don’t just pop into existence without being caused . That is as fundamental a principle as any we can think of. Philosophers have for centuries upheld the principle that “nothing comes from nothing.” They even have a fancy Latin phrase for it: ex nihilo nihil fir [1] . The problem is that my decision to make a cheese omelet seems to be just that: something that causes but is not itself caused. Indeed, as noted earlier, the libertarian Roderick Chisholm embraces this consequence of the libertarian position very clearly when he claimed that when we exercise our free will,

“we have a prerogative which some would attribute only to God: each of us, when we really act, is a prime mover unmoved. In doing what we do, we cause certain events to happen, and nothing and no one, except we ourselves, causes us to cause those events to happen” (Chisholm, 1964).

How could something like this exist? At this point the libertarian might respond something like this:

I am not claiming that something comes from nothing; I am just claiming that our decisions are not themselves determined by any prior thing. Rather, we ourselves, as agents, cause our decisions and nothing else causes us to cause those decisions (at least in cases where we have acted freely).

However, it seems that the libertarian in this case has simply pushed the mystery back one step: we cause our decisions, granted, but what causes us to make those decisions? The libertarian’s answer here is that nothing causes us. But now we have the same problem again: the agent is responsible for causing the decision but nothing causes the agent to make that decision. Thus we seem to have something coming from nothing. Let’s call this argument the argument from mysterious causes. Here’s the argument in standard form:

- The existence of free will implies that when an agent freely decides to do something, the agent’s choice is not caused (determined) by anything.

- To say that something has no cause is to violate the ex nihilo nihil fit principle.

- But nothing can violate the ex nihilo nihil fit principle.

- Therefore, there is no free will (from 1-3)

The hard determinist will make a strong case for premise 3 in the above argument by invoking basic scientific principles such as the law of conservation of energy, which says that the amount of energy within a closed system stays that same. That is, energy cannot be created or destroyed. Consider a billiard ball. If it is to move then it must get the required energy to do so from someplace else (typically another billiard ball knocking into it, the cue stick hitting it or someone tilting the pool table). To allow that something could occur without any cause—in this case, the agent’s decision—would be a violation of the conservation of energy principle, which is as basic a scientific principle as we know. When forced to choose between uphold such a basic scientific principle as this and believing in free will, the hard determinist opts for the former. The hard determinist will put the ball in the libertarian’s court to explain how something could come from nothing.

I will close this section by indicating how these problems in philosophy often ramify into other areas of philosophy. In the first place, there is a fairly common way that libertarians respond to the charge that their view violates basic principles such as ex nihilo nihil fit and, more specifically, the physical law of conservation of energy. Libertarians could claim that the mind is not physical—a position known in the philosophy of mind as “substance dualism” (see philosophy of mind chapter in this textbook for more on substance dualism). If the mind isn’t physical, then neither are our mental events, such our decisions.

Rather, all of these things are nonphysical entities. If decisions are nonphysical entities, there is at least no violation of the physical laws such as the law of conservation of energy. [2] Of course, if the libertarian were to take this route of defending her position, she would then need to defend this further assumption (no small task). In any case, my main point here is to see the way that responses to the problem of free well and determinism may connect with other issue within philosophy. In this case, the libertarian’s defense of free will may turn out to depend on the defensibility of other assumptions they make about the nature of the mind. But the libertarian is not the only one who will need to ultimately connect her account of free will up with other issues in philosophy. Since hard determinists deny that free will exists, it seems that they will owe us some account of moral responsibility. If, moral responsibility requires that humans have free will (see previous section), then in denying free will we seem to also be denying that humans have moral responsibility. Thus, hard determinists will face the objection that in rejecting free will they also destroy moral responsibility.

But since it seems we must hold individuals morally to account for certain actions (such as the embezzler from the previous section), the hard determinist

needs some account of how it makes sense to do this given that human being don’t have free will. My point here is not to broach the issue of how the hard determinist might answer this, but simply to show how hard determinist’s position on the problem of free will and determinism must ultimately connect with other issues in philosophy, such issues in metaethics [3] . This is a common thing that happens in philosophy. We may try to consider an issue or problem in isolation, but sooner or later that problem will connect up with other issues in philosophy.

Compatibilism

The best argument for compatibilism builds on a consideration of the difficulties with the incompatibilist definition of free will (which both the libertarian and the hard determinist accept). As defined above, compatibilists agree with the hard determinists that determinism is true, but reject the incompatibilist definition of free will that hard determinists accept. This allows compatbilists to claim that free will is compatible with determinism. Both libertarians and hard compatibilists tend to feel that this is somehow cheating, but the compatibilist attempts to convince us arguing that the strong incompatibilist definition of freedom is problematic and that only the weaker compatibilist definition of freedom—free actions are voluntary actions—will work. We will consider two objections that the compatibilist raises for the incompatibilist definition of freedom: the epistemic objection and the arbitrariness objection . Then we will consider the compatibilist’s own definition of free will and show how that definition fits better with some of our common sense intuitions about the nature of free actions.

The epistemic objection is that there is no way for us to ever know whether any one of our actions was free or not. Recall that the incompatibilist definition of freedom says that a decision is free if and only if I could have chosen otherwise than I in fact chose, given exactly all the same conditions. This means that if we were, so to speak, rewind the tape of time and be given that decision to make over again, we could have chosen differently. So suppose the question is whether my decision to make a cheese omelet for breakfast was free. To answer this question, we would have to know when I could have chosen differently. But how am I supposed to know that ? It seems that I would have to answer a question about a strange counterfactual : if given that decision to make over again, would I choose the same way every time or not? How on earth am I supposed to know how to answer that question? I could say that it seems to me that I could make a different decision regarding making the cheese omelet (for example, I could have decided to eat cereal instead), but why should I think that that is the right answer? After all, how things seem regularly turn out to be not the case—especially in science. The problem is that I don’t seem to have any good way of answering this counterfactual question of what I would choose if given the same decision to make over again. Thus the epistemic objection [4] is that since I have no way of knowing whether I would/wouldn’t make the same decision again, I can never know whether any of my actions are free.

The arbitrariness objection is that it turns our free actions into arbitrary actions. And arbitrary actions are not free actions. To see why, consider that if the incompatibilist definition is true, then nothing determines our free choices, not even our own desires . For if our desires were determining our choices then if we were to rewind the tape of time and, so to speak, reset everything— including our desires —the same way, then given those same desires we would choose the same way every time. And that would mean our choice was not free, according to the incompatbilist. It is imperative to remember that incompatibilism says that if an action is not free if it is determined ( including if it is determined by our own desires ). But now the question is: if my desires are not causing my decision, what is? When I make a decision, where does that decision come from, if not from my desires and beliefs? Presumably it cannot come from nothing ( ex nihilo nihil fit ). The problem is that if the incompatibilist rejects that anything is causing my decisions, then how can my decisions be anything but arbitrary?

Presumably an arbitrary decision—a decision not driven by any reason at all—is not an exercise of my freedom. Freedom seems to require that we are exercising some kind of control over my actions and decisions. If my action or decision is arbitrary that means that no reason or explanation of the action/decision can be given. Here’s the arbitrariness objection cast as a reductio ad absurdum argument:

- A free choice is one that isn’t determined by anything, including our desires. [incompatibilist definition of freedom]

- If our own desires are not determining our choices, then those choices are arbitrary.

- If a choice is arbitrary then it is not something over which we have control

- If a choice isn’t something over which we have control, then it isn’t a free choice

- Therefore, a free choice is not a free choice (from 1-4)

A reductio ad absurdum argument is one that starts with a certain assumption and then derives a contradiction from that assumption, thereby showing that assumption must be false. In this case, the incompatibilist’s definition of a free choice leads to the contradiction that something that is a free choice isn’t a free choice.

What has gone wrong here? The compatibilist will claim that what has gone wrong is incompatibilist’s idea that a free action must be one that isn’t caused/determined by anything. The compatibilist claims that free actions can still be determined, as long as what is determining them is our own internal reasons, over which we have some control, rather than external things over which we have no control. Free choices, according to the compatibilist, are just choices that are caused by our own best reasons . The fact that, given the exact same choices, I couldn’t have chosen otherwise doesn’t undermine what freedom is (as the incompatibilist claims) but defines what it is. Consider an example. Suppose that my goal is to spend the shortest amount of time on my commute home from work so that I can be on time for a dinner date. Also suppose, for simplicity, that there are only three possible routes that I can take: route 1 is the shortest, whereas route 2 is longer but scenic and 3 is more direct but has potentially more traffic, especially during rush hour. I am leaving early from work today so that I can make my dinner date but before I leave, I check the traffic and learn that there has been a wreck on route 1. Thus, I must choose between routes 2 and 3. I reason that since I am leaving earlier, route 3 will be the quickest since there won’t be much traffic while I’m on my early commute home. So I take route 3 and arrive home in a timely manner: mission accomplished. The compatibilist would say that this is a paradigm case of a free action (or a series of free actions). The decisions I made about how to get home were drive both by my desire to get home quickly and also by the information I was operating with. Assuming that that information was good and I reasoned well with it and was thereby able to accomplish my goal (that is, get home in a timely manner), then my action is free. My action is free not because my choices were undetermined, but rather because my choices were determined (caused) by my own best reasons—that is, by my desires and informed beliefs. The incompatibilist, in contrast, would say that an action is free only if I could have chosen otherwise, given all the same conditions again. But think of what that would mean in the case above! Why on earth would I choose routes 1 or 2 in the above scenario, given that my most pressing goal is to be able to get to my dinner date on time? Why would anyone knowingly choose to do something that thwarts their primary goals? It doesn’t seem that, given the set of beliefs and desires that I actually had at the time, I could have chosen otherwise in that situation. Of course, if you change the information I had (my beliefs) or you change what I wanted to accomplish (my desires), then of course I could have acted otherwise than I did. If I didn’t have anything pressing to do when I left work and wanted a scenic and leisurely drive home in my new convertible, then I probably would have taken route 2! But that isn’t what the incompatibilist requires for free will. As we’ve seen, they require the much stronger condition that one’s action be such that it could have been different even if they faced exactly the same condition over again. But in this scenario that would be an irrational thing to do. Of course, if one’s goal were to be irrational and to thwart one’s own desires, I suppose they could do that. But that would still seem to be acting in accordance with one’s desires.

Many times free will is treated as an all or nothing thing, either humans have it or they don’t. This seems to be exactly how the libertarian and hard determinist see the matter. And that makes sense given that they are both incompatibilists and view free will and determinism like oil and water—they don’t mix. But it is interesting to note that it is common for us to talk about decisions, action, or even whole lives (or periods of a life) as being more or less free . Consider the Goethe quotation at the beginning of this chapter: “none are more enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.” Here Goethe is conceiving of freedom as coming in degrees and claiming that those who think they are free but aren’t as less free than those who aren’t free and know it. But this way of speaking implies that free will and determinism are actually on a continuum rather than a black and white either or. The compatibilist can build this fact about our ordinary ways of speaking about freedom into an argument for their position. Call this the argument from ordinary language . The argument from ordinary language is that only compatibilism is able to accommodate our common way of speaking about freedom coming in degrees—that is, as actions or decisions being more or less free. The libertarian can’t account for this since the libertarian sees freedom as an all or nothing matter: if you couldn’t have done otherwise then your action was not truly free; if you could have done otherwise, then it was. In contrast, the compatibilist is able to explain the difference between more/less free action on the continuum. For the compatibilist, the freest actions are those in which one reasons well with the best information, thus acting for one’s own best reasons, thus furthering one’s interests. The least free actions are those in which one lacks information and reason poorly, thus not acting for one’s own best reasons, thus not furthering one’s interests. Since reasoning well, being informed, and being reflective are all things that come in degrees (since one can possess these traits to a greater or lesser extent) and since these attribute define what free will is for the compatibilist, it follows that free will comes in degrees. And that means that the compatibilist is able to make sense or a very common way that we talk about freedom (as coming in degrees) and thus make sense of ourselves, whereas the libertarian isn’t.

There’s one further advantage that compatibilists can claim over libertarians. Libertarians defend the claim that there are at least some cases where one exercises one’s free will and that this entails that determinism is false. However, this leaves totally open the extent of human free will. Even if it were true that there are at least some cases where humans exercise free will, there might not be very many instances and/or those decisions in which we exercise free will might be fairly trivial (for example, moving one’s finger to the left or right). But if it were to turn out that free will was relatively rare, then even if the libertarian were correct that there are at least some instances where we exercise free will, it would be cold comfort to those who believe in free will. Imagine: if there were only a handful of cases in your life where your decision was an exercise of your free will, then it doesn’t seem like you have lived a life which was very free. In other words, in such a case, for all practical purposes, determinism would be true.

Thus, it seems like the question of how widespread free will is is an important one. However, the libertarian seems unable to answer it for reasons that we’ve already seen. Answering the question requires knowing whether or not one could have acted otherwise than one in fact did. But in order to know this, we’d have to know how to answer a strange counterfactual—whether I could have acted differently given all the same conditions. As noted earlier (“the epistemic objection”), this raises a tough epistemological question for the libertarian: how could he ever know how to answer this question? And so how could he ever know whether a particular action was free or not? In contrast, the compatibilist can easily answer the question of how widespread free will is: how “free” one’s life is depends on the extent to which one’s actions are driven by their own best reasons. And this, in turn, depends on factors such as how well-informed, reflective, and reasonable a person is. This might not always be easy to determine, but it seems more tractable than trying to figure out the truth conditions of the libertarian’s counterfactual.

In short, it seems that compatibilism has significant advantages over both libertarianism and hard determinism. As compared to the libertarian, compatibilism gives a better answer to how free will can come in degrees as well as how widespread free will is. It also doesn’t face the arbitrariness objection or the epistemic objection. As compared to the hard determinist, the compatibilist is able to give a more satisfying answer to the moral responsibility issue. Unlike the hard determinist, who sees all action as equally determined (and so not under our control), the compatibilist thinks there is an important distinction within the class of human actions: those that are under our control versus those that aren’t. As we’ve seen above, the compatibilist doesn’t see this distinction as black and white, but, rather, as existing on a continuum. However, a vague boundary is still a boundary. That is, for the compatibilist there are still paradigm cases in which a person has acted freely and thus should be held morally responsible for that action (for example, the person who embezzles money from a charity and then covers it up) and clear cases in which a person hasn’t acted freely (for example, the person who was told to do something by their boss but didn’t know that it was actually something illegal). The compatibilist’s point is that this distinction between free and unfree actions matters, both morally and legally, and that we would be unwise to simply jettison this distinction, as the hard determinist does. We do need some distinction within the class of human actions between those for which we hold people responsible and those for which we don’t. The compatibilist’s claim is that they are able to do with while the hard determinist isn’t. And they’re able to do it without inheriting any of the problems of the libertarian position.

Study questions

- True or false: Compatibilists and libertarians agree on what free will is (on the concept of free will).

- True or false: Hard determinists and libertarians agree that an action is free only when I could have chosen otherwise than I in fact chose.

- True or false: the libertarian gives a transcendental argument for why we must have free will.

- True or false: both compatibilists and hard determinists believe that all human actions are determined.

- True or false: compatibilists see free will as an all or nothing matter: either an action is free or it isn’t; there’s no middle ground.

- True or false: compatibilists think that in the case of a truly free action, I could have chosen otherwise than I in fact did choose.

- True or false: One objection to libertarianism is that on that view it is difficult to know when a particular action was free.

- True or false: determinism is a fundamental assumption of the natural sciences (physics, chemistry, biology, and so on).

- True or false: the best that support the libertarian’s position are cases of very simple or arbitrary actions, such as choosing to move my finger to the left or to the right.

- True or false: libertarians thinks that as long as my choices are caused by my desires, I have chosen freely.

For deeper thought

- Consider the Shopenhauer quotation at the beginning of the chapter. Which of the three views do you think this supports and why?

- Consider the movie The Truman Show . How would the libertarian and compatibilist disagree regarding whether or not Truman has free will?

- Consider the Tolstoy quote at the beginning of the chapter. Which of the three views does this support and why?

- Consider a child being raised by white supremacist parents who grows up to have white supremacist views and to act on those views. As a child, does this individual have free will? As an adult, do they have free will? Defend your answer with reference to one of the three views.

- Consider the eccentric neuroscientist example (above). How might a compatibilist try to show that this isn’t really an objection to her view? That is, how might the compatibilist show that this is not a case in which the individual’s action is the result of a well-informed, reflective choice?

- Actually, the phrase was originally a Latin phrase, not an English one because at the time in Medieval Europe philosophers wrote in Latin. ↵

- On the other hand, if these nonphysical decisions are supposed to have physical effects in the world (such as causing our behaviors) then although there is no problem with the agent’s decision itself being uncaused, there would still be a problem with how that decision can be translated into the physical world without violating the law of conservation of energy. ↵

- One well-known and influential attempt to reconcile moral responsibility with determinism is P.F. Strawson’s “Freedom and Resentment” (1962). ↵

- The term “epistemic” just denotes something relating to knowledge. It comes from the Greek work episteme, which means knowledge or belief. ↵

Introduction to Philosophy Copyright © by Matthew Van Cleave is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 Chaos, Indeterminism, and Free Will

Robert C. Bishop is associate professor of Physics and Philosophy and the John and Madeleine McIntyre Professor for the Philosophy and History of Science at Wheaton College. He has published numerous articles on reduction and emergence, nonlinear dynamics, complexity, determinism and free will. His most recent book is The Philosophy of the Social Science.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions