Tamil Solution

Educational News | Recruitment News | Tamil Articles

- Add a Primary Menu

- Tamil Essays

Indian Culture Tamil Essay – இந்திய கலாச்சாரம் கட்டுரை

Indian Culture Tamil Essay – India Kalacharam Katturai – இந்திய கலாச்சாரம் கட்டுரை

இந்திய கலாச்சாரமானது பல்வேறு கலாச்சாரங்களின் தொகுப்பாகும் , வேற்றுமையில் ஒற்றுமை என்ற பதத்திர்ற்கு ஏற்ப மொழிவாரியாக ,உடை வாரியாக ,உணவு வாரியாக ,கலை வாரியாக வேறுபடுகிறது.

இந்திய கலாச்சாரத்தின் உச்சமாக விருந்தோம்பல் இடம் பெறுகிறது, இருக்கைகளை கூப்பி வணக்கமிடும் பழக்கம் தொன்று தொட்டு இந்திய கலாச்சாரத்தின் அத்தனை பிரிவுகளிலும் இடம் பெறுகிறது .

இந்திய கலாச்சாரம் வேற்று நாடுகளின் படையெடுப்பு மற்றும் ஆட்சி காரணமாக சிதைந்து போகாமல் ,ஒவ்வொரு நாலும் மேம்பட்டு கொண்டே இருக்கிறது ,உடுத்தும் உடையில் மேற்கத்திய நாகரிகம் பளிச்சிட்டாலும் உள்ளூர அமைந்த இந்திய கலாச்சார ஒரு போதும் மாறாமலே இருக்கிறது.

இந்திய கலாச்சாரம் பற்றிய ஆய்வு கட்டுரை எழுதும் ஒவ்வொரு மாணவருக்கும் ஏற்படும் பிரமிப்பு என்னவென்றால் எத்தனையோ கலாச்சாரங்களின் சாயல் படிந்தாலும் இந்திய கலாச்சாரம் உயர்ந்து நிற்பதுதான்

மத ரீதியான கலாச்சாரங்களை வரையறுக்கும் ஆய்வாளர்கள் இந்திய கலாச்சாரத்தை மட்டும் மொழி ரீதியாகவே அணுகுகிறார்கள் , ஒவ்வொரு மொழிக்கும் அதன் கலாச்சாரம் மாறாத புத்தகம் ,நாடகங்கள் ,திரைப்படங்கள் என மேலோங்கி நிற்கிறது,

மொழி ரீதியாக கலாச்சாரங்கள் பிரிக்க பட்டாலும் அனைத்திர்ற்கும் உள்ளக இந்திய கலாச்சாரம் என்ற ஒற்றை தொகுப்பு அடங்கியுள்ளது .

புதிய மத பழக்க வழக்கங்கள் இந்திய கலாச்சாரத்தின்மீது ஊன்றி இருந்தாலும் , அவற்றயும் தன்னுடன் இணைத்து கொள்ளும் பழக்கம் இந்தியர்களுக்கு உண்டே அன்றி ,பழைய கலாச்சாரத்தை மறந்து புதிய கலாச்சாரத்தை தழுவும் முறை அறவே இல்லை

Comments are closed.

You Might Also Like

என்.ஆர். நாராயண மூர்த்தி, bharathiar katturai in tamil – பாரதியார் கட்டுரை, உழைப்பே உயர்வு கட்டுரை – hard work essay in tamil (ulaipe uyarvu), silapathikaram katturai in tamil – சிலப்பதிகாரம் கட்டுரை.

Essay on Tamil Culture

Students are often asked to write an essay on Tamil Culture in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Tamil Culture

Introduction.

Tamil culture is one of the oldest and richest cultures in the world. Originating from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, it has a history that dates back over 2000 years.

At the heart of Tamil culture is the Tamil language. It’s one of the longest-surviving classical languages in the world, known for its rich literature and poetry.

Art and Architecture

Tamil culture is renowned for its unique art and architecture. The Dravidian style of architecture, seen in many temples, is a significant part of this culture.

Festivals like Pongal and Tamil New Year reflect the vibrant spirit of Tamil culture, showcasing its traditions, music, and dance.

In conclusion, Tamil culture, with its deep-rooted traditions, is a testament to the rich heritage of India. It continues to thrive and inspire people worldwide.

250 Words Essay on Tamil Culture

Tamil culture, one of the oldest and richest cultures globally, is the embodiment of the traditions, values, and art forms of the Tamil people. It is an intrinsic part of the Indian subcontinent, primarily in the state of Tamil Nadu and among the Tamil diaspora worldwide.

Language and Literature

The Tamil language, recognized as a classical language by UNESCO, is the lifeblood of Tamil culture. It has a rich literary tradition with works like Thirukkural, a treatise on ethics, and Silappatikaram, an epic of love and revenge, reflecting the philosophical and moral depth of the culture.

Tamil culture has significantly contributed to Indian art and architecture, with the Dravidian style of temple architecture and Bharatanatyam dance form being its most recognized symbols. The grandeur of temples like Brihadeeswarar Temple and the aesthetic beauty of Bharatanatyam are testimonies to the artistic excellence of this culture.

Cuisine and Festivals

Tamil cuisine, known for its flavors and health benefits, is another essential aspect of Tamil culture. The use of rice, lentils, and spices is predominant, with dishes like Dosa, Sambar, and Rasam being popular. Pongal, Diwali, and Karthigai Deepam are some of the vibrant festivals celebrated, which strengthen communal harmony and reflect the culture’s spiritual depth.

The Tamil culture, with its profound philosophical insights, artistic brilliance, and communal harmony, has a significant impact on the Indian subcontinent and the world. It is a culture that has not only survived but thrived over millennia, adapting to changes while retaining its unique identity.

500 Words Essay on Tamil Culture

Tamil culture, one of the oldest and richest cultures in the world, is the embodiment of the traditions, values, and artistic expression of the Tamil people. Originating from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, it has a rich history dating back over two millennia, influencing and being influenced by other cultures. This essay will delve into various aspects of Tamil culture, including its language, literature, music, dance, and cuisine.

The Tamil language, recognized as a classical language by the Indian government, is the lifeblood of Tamil culture. It is one of the longest surviving classical languages in the world, with literature dating back to the 3rd Century BC. The Thirukkural, written by the poet Thiruvalluvar, is a seminal work in Tamil literature, offering wisdom and guidance on ethics, love, and statecraft. The Sangam literature, comprising of 2,381 poems, provides a window into the ancient Tamil world.

Music and Dance

Music and dance are integral to Tamil culture. Carnatic music, a classical music form of South India, has its roots in Tamil Nadu. The compositions of the Trinity of Carnatic music – Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Syama Sastri – continue to be celebrated worldwide. Similarly, Bharatanatyam, one of the oldest dance forms in India, originated in Tamil Nadu. It is a beautiful blend of Bhava (emotion), Raga (melody), and Tala (rhythm), and is traditionally performed in temples.

Tamil cuisine is a culinary treasure trove, offering a wide variety of vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes. It is characterized by the use of rice, lentils, and spices like mustard, fenugreek, and asafoetida. The Chettinad cuisine, known for its fiery and aromatic dishes, and the simple yet delicious meals served on banana leaves are iconic elements of Tamil culinary culture.

Festivals form an essential part of Tamil culture, reflecting the community’s religious and agricultural practices. Pongal, a harvest festival, is one of the most important Tamil festivals. It is a time of thanksgiving to nature, marked by cooking the Pongal dish, a sweet rice preparation. Other significant festivals include Karthigai Deepam, a festival of lights, and Tamil New Year, celebrated with feasting and cultural performances.

Tamil culture, with its rich language, literature, music, dance, cuisine, and festivals, is a testament to the Tamil people’s resilience and creativity. It is a culture that has not only survived but thrived, despite numerous challenges. It continues to evolve while maintaining its unique identity, contributing to the multicultural tapestry of India and the world. As we move forward, understanding and appreciating this ancient culture becomes even more crucial in fostering a sense of unity in diversity.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Importance of Culture and Tradition

- Essay on Odisha Culture

- Essay on Maharashtra Culture

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Home > Tamils - a Nation without a State > The Tamil Heritage > Tamil Military Virtues and Ideals > Tamil Language & Literature > Culture of the Tamils > Sathyam Art Gallery > Spirituality & the Tamil Nation > Tamil Digital Renaissance > Tamil National Forum > One Hundred Tamils of the 20th Century > Tamil Eelam Struggle for Freedom > Nations & Nationalism >

Nadesan Satyendra 1998, 2009

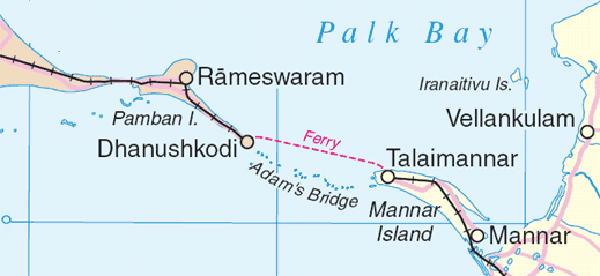

The Tamils are an ancient people. Their history had its beginnings in the rich alluvial plains near the southern extremity of peninsular India which included the land mass known as the island of Sri Lanka today. The island's plant and animal life (including the presence of elephants) evidence the earlier land connection with the Indian sub continent. So too do satellite photographs which show the submerged 'land bridge' between Dhanuskodi on the south east of the Indian sub-continent and Mannar in the north west of the island.

Some researchers have concluded that it was during the period 6000 B.C. to 3000 B.C. that the island separated from the Indian sub continent and the narrow strip of shallow water known today as the Palk Straits (named after Robert Palk, who was a governor of Madras Presidency (1755-1763) under the British Raj) came into existence.

Many Tamils trace their origins to the people of Mohenjodaro in the Indus Valley around 6000 years before the birth of Christ. There is, however, a need for further systematic study of the history of the early Tamils and proto Tamils.

"Dravidians, whose descendents still live in Southern India, established the first city communities, in the Indus valley, introduced irrigation schemes, developed pottery and evolved a well ordered system of government." (Reader's Digest Great World Atlas, 1970)

Clyde Ahmad Winters , who has written extensively on Dravidian origins commented:

"Archaeological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Dravidians were the founders of the Harappan culture which extended from the Indus Valley through northeastern Afghanistan, on into Turkestan. The Harappan civilization existed from 2600-1700 BC. The Harappan civilization was twice the size the Old Kingdom of Egypt. In addition to trade relations with Mesopotamia and Iran, the Harappan city states also had active trade relations with the Central Asian peoples."

He has also explored the question whether the Dravidians were of African origin. (Winters, Clyde Ahmad, "Are Dravidians of African Origin", P.Second ISAS,1980 - Hong Kong:Asian Research Service, 1981 - pages 789- 807) Other useful web pages on the Indus civilisation (suggested by Dr.Jude Sooriyajeevan of the National Research Council, Canada) include the Indus Dictionary .

At the same time, the Aryan/Dravidian divide in India and the ' Aryan Invasion Theory ' itself has come under attack by some modern day historians. (see also Sarasvati-Sindhu civilisation ; ' Hinduism: Native or Alien to India ')

Professor Klaus Klostermaier in 'Questioning the Aryan Invasion Theory and Revising Ancient Indian History' commented:

"India had a tradition of learning and scholarship much older and vaster than the European countries that, from the sixteenth century onwards, became its political masters. Indian scholars are rewriting the history of India today. One of the major points of revision concerns the so called 'Aryan invasion theory', often referred to as 'colonial-missionary', implying that it was the brainchild of conquerors of foreign colonies who could not but imagine that all higher culture had to come from outside 'backward' India, and who likewise assumed that a religion could only spread through a politically supported missionary effort. While not buying into the more sinister version of this revision, which accuses the inventors of the Aryan invasion theory of malice and cynicism, there is no doubt that early European attempts to explain the presence of Indians in India had much to with the commonly held Biblical belief that humankind originated from one pair of humans - Adam and Eve to be precise ..."

Hinduism Today concluded in Rewriting Indian History - Hindu Timeline:

"Although lacking supporting scientific evidence, this (Aryan Invasion) theory, and the alleged Aryan-Dravidian racial split, was accepted and promulgated as fact for three main reasons. It provided a convenient precedent for Christian British subjugation of India. It reconciled ancient Indian civilisation and religious scripture with the 4000 bce Biblical date of Creation. It created division and conflict between the peoples of India, making them vulnerable to conversion by Christian missionaries." "Scholars today of both East and West believe the Rig Veda people who called themselves Aryan were indigenous to India, and there never was an Aryan invasion. The languages of India have been shown to share common ancestry in ancient Sanskrit and Tamil. Even these two apparently unrelated languages, according to current "super-family" research, have a common origin: an ancient language dubbed Nostratic."

Robert Caldwell wrote in 1875:

"... From the evidence of words in use amongst the early Tamils, we learn the following items of information. They had 'kings' who dwelt in 'strong houses' and ruled over 'small districts of country'. They had 'minstrels', who recited 'songs' at 'festivals', and they seem to have had alphabetical 'characters' written with a style on Palmyra leaves. A bundle of those leaves was called 'a book'; they acknowledged the existence of God, whom they styled as ko, or King.... They erected to his honour a 'temple', which they called Ko-il, God's-house. They had 'laws' and 'customs'... Marriage existed among them. They were acquainted with the ordinary metals... They had 'medicines', 'hamlets' and 'towns', 'canoes', 'boats' and even 'ships' (small 'decked' coasting vessels), no acquaintance with any people beyond the sea, except in Ceylon, which was then, perhaps, accessible on foot at low water.. They were well acquainted with agriculture.... All the ordinary or necessary arts of life, including 'spinning', 'weaving' and 'dyeing' existed amongst them. They excelled in pottery..." (Robert Caldwell: Comparative Grammar of Dravidian or South Indian Family of Languages - Second Edition 1875 - Reprinted by the University of Madras, 1961)

The Tamils were a sea faring people . They traded with Rome in the days of Emperor Augustus. They sent ships to many lands bordering the Indian Ocean and with the ships went traders, scholars, and a way of life. Tamil inscriptions in Indonesia go back some two thousand years. The oldest Sanskrit inscriptions belonging to the third century in Indo China bear testimony to Tamil influence and until recent times Tamil texts were used by priests in Thailand and Cambodia. The scattered elements of ruined temples of the time of Marco Polo's visit to China in the 13th century give evidence of purely Tamil structure and include Tamil inscriptions.

"Tamil Nadu, the home land of the Tamils, occupies the southern most region of India. Traditionally, Thiruvenkatam - the abode of Sri Venkatewara and a range of hills of the Eastern Ghats - formed the northern boundary of the country and the Arabian sea line the western boundary. However as a result of infiltrations, made by peoples from other territories, Tamil lost its ground in the west as well as in the north. In medieval times, the country west of the mountains, became Kerala and that in the north turned part of Andhra Desa. Bounded by the states of Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Desa, the Tamil Nadu of the present day extends from Kanyakumari in the south to Tiruttani in the North.... In early times the Pandyas , the Cheras and the Cholas held their pioneering sway over the country and extended their authority beyond the traditional frontiers. As a result the Tamil Country served as the homeland of extensive empires. It was during this period that the Tamil bards composed the masterpieces in Tamil literature. "In the first decade of the 14th century the rising tide of Afghan imperialism swept over South India. The Tughlugs created a new province in the Tamil Country called Mabar, with its capital at Madurai which in 1335 asserted independence as the Sultanate of Madurai. After a short period of stormy existence, it gave way to the Vijayanagar Empire... Since then, the Telegus, the Brahminis, the Marathas and the Kannadins wrested possession of the territory. Between 1798 and 1801, the country passed under the direct administration of the English East India Company ." (History of Tamil Nadu 1565 - 1982: Professor K.Rajayyan, Head of the School of Historical Studies, M.K.University, Madurai - Raj Publishers, Madurai, 1982)

Today an estimated 80 million Tamils live in many lands - more than 50 million Tamils live in Tamil Nadu in South India and around 3 million reside in the island of Sri Lanka.

The response of a people to invasion by aliens from a foreign land is a measure of the depth of their roots and the strength of their identity. It was under British conquest that the Tamil renaissance of the second half of the 19th century gathered momentum.

It was a renaissance which had its cultural beginnings in the discovery and the subsequent editing and printing of the Tamil classics of the Sangam period . These had existed earlier only as palm leaf manuscripts. Arumuga Navalar in Jaffna, in the island of Sri Lanka, published the Thirukural in 1860 and Thirukovaiyar in 1861. Thamotherampillai , who was born in Jaffna but who served in Madras, published the grammatical treatise Tolkapiyam by collating material from several original ola leaf manuscripts.

It was on the foundations laid by Arumuga Navalar and Thamotherampillai that Swaminatha Aiyar , who was born in Tanjore, in South India, put together the classics of Tamil literature of the Sangam period. Swaminatha Aiyar spent a lifetime researching and collecting many of the palm leaf manuscripts of the classical period and it is to him that we owe the publication of Cilapathikaram , Manimekali , Puranuru , Civakachintamani and many other treatises which are a part of the rich literary heritage of the Tamil people.

Another Tamil from Jaffna, Kanagasabaipillai served at Madras University and his book 'Tamils - Eighteen Hundred Years Ago' reinforced the historical togetherness of the Tamil people and was a valuable source book for researchers in Tamil studies in the succeeding years. It was a Tamil cultural renaissance in which the contributions of the scholars of Jaffna and those of South India are difficult to separate.

Again, not surprisingly, it was a renaissance which was also linked with a revived interest in Saivaism and a growing recognition that Saivaism was the original religion of the Tamil people. Arumuga Navalar established schools in Jaffna, in Sri Lanka and in Chidambaram, in South India and his work led to the formation of the Saiva Paripalana Sabai in Jaffna in 1888, the publication of the Jaffna Hindu Organ in 1889 and the founding of the Jaffna Hindu College in 1890.

In South India, J.M.Nallaswami Pillai, who was born in Trichinopoly, published Meykandar's Sivajnana Bodham in English in 1895 and in 1897, he started a monthly called Siddhanta Deepika which was regarded by many as reflecting the 19th century ' renaissance of Saivaism'. A Tamil version of the journal was edited by Maraimalai Atikal whose writings gave a new sense of cohesion to the Tamil people - a cohesion which was derived from the rediscovery of their ancient literature and the rediscovery of their ancient religion.

The cultural renaissance of the 19th century led to an increasing Tamil togetherness and was linked with the thrust for social reform and political power - a thrust which at the same time, sought to marry a rising Tamil togetherness with the immediate and larger struggle for freedom from British rule.

In South India, no one exemplified the marriage of this duality more effectively than Subramania Bharathy whose songs in Tamil stirred the hearts of millions of Tamils, both as Tamils and as Indians. The words of Bharathy's Senthamil Nadu Enum Pothinale, continue to move the hearts of the Tamil people today. It was his salute to the Tamil nation that was yet unborn. His Viduthalai was the joyous song of Indian freedom and there he reached out beyond the Tamil nation to the day when Bharat would be free.

Bharathy sought to consolidate the togetherness of his own people by his ceaseless campaign against casteism and for women's rights. The Bharathy birth centenary celebrations of 1982 served to underline the permanent place that Bharathy will always have in the hearts of the Tamil people, whether they be from Tamil Nadu, Tamil Eelam, Malaysia, Singapore or elsewhere.

Two other Tamils will be always associated with the rise of Tamil national consciousness in the first two decades of the 20th century - lawyer, Tamil scholar and revolutionary, V.V.S.Aiyar and the Swadeshi steam ship hero, Kappal Otiya Thamilan, V.O.Chidambram Pillai .

Aiyar was a lawyer who joined Grays Inn in London to become a barrister but became a revolutionary instead. Later, he wrote many books in Tamil and in English and is regarded by many as the father of the modern Tamil short story. He was a pioneer in Tamil literary criticism. His major works included a translation of the Thirukural and ' Kamba Ramayanam - A Study'.

In the years after the first World War, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi reached out to the underlying unity of India and sought to weld together the many peoples of the Indian subcontinent into a larger whole. But the attempt did not entirely succeed. The assessment of Pramatha Chauduri who wrote in Bengali in 1920 was not without significance:

"...You have accused me of 'Bengali patriotism'. I feel bound to reply. If its a crime for a Bengali to harbour and encourage Bengali patriotism in his mind, then I am guilty "But I ask you, what other patriotism do you expect from a Bengali writer? The fact that I do not write in English should indicate that non Bengali patriotism does not sway my mind. If I had to make patriotic speeches in a language that is the language of no part of India, then I would have had to justify that patriotism by saying it does not relate to any special part of India as a whole. In a language learnt by rote you can only express ideas learnt by heart. ... The whole of India is now under British rule...therefore, the main link between us is the link of bondage and no province can cut through this subjugation by its own efforts and actions...So today we are obliged to tell the people of India, 'Unite and Organise'... People will recognise the value of provincial patriotism the moment they attain independence...Then the various nations of India will not try to merge, they will try to establish a unity amongst themselves... To be united due to outside pressure and to unite through mutual regard are not the same. Just as there is a difference between the getting together of five convicts in a jail and between five free men... Indian patriotism then will be built on the foundation of provincial patriotism, not just in words but in reality ..." ( Pramatha Chaudhuri : Bengali Patriotism - Sabuj Patra 1920, translated and reprinted in Facets, September 1982)

"The Tamil Renaissance took place at the same time as the (Indian) Nationalist Movement. The outcome of this interaction of the renaissance and the Nationalist Movement was the genesis of a consciousness of a separate identity resulting in Dravidian Nationalism.... In philology the term 'Dravidian' was used to denote a group a group of languages mainly spoken in South India, namely, Tamil Telegu, Kannada and Malayalam. Later when the term was extended to denote a race, again it denoted the peoples speaking these four languages. But in South Indian politics as well as in general usage since the beginning of this century the term 'Dravidian' came to denote the 'Tamils' only and not the other three language speaking peoples. ... Hence it may be observed that the terms 'Tamil Nationalism' and 'Dravidian Nationalism' were synonymous" - K.Nambi Arooran - Tamil Renaissance and Dravidian Nationalism, Koodal Publishers, Madurai, 1980

The establishment of Annamalai University in Chidambaram and later the Tamil Isai Sangam in Madras were manifestations of a rising Tamil self consciousness. The students at Annamalai University were to become influential political leaders of the Tamil people in the years to come.

As early as 1926, Sankaran Nair, a nominated member of the Council of State in Delhi, pleaded for self government to the ten Tamil districts of the Madras Presidency, with its own army, navy and airforce.

Scholar politician V. Kaliyanasundarar writing in 1929 urged that Tamil Nadu constituted a nation within the Indian state. He declared that the correct English translation of the word Nadu was nation and not land and pointed out that the early Tamils had their own government, language, culture and historical traditions. (V.Kaliyanasundarar, Tamil Cholai, Volume 1, Madras 1954)

In 1937, Periyar E.V. Ramasamy took over the leadership of the South Indian Liberal Federation, commonly called the Justice Party. At the Justice Party confederation held in Madras in 1938 , Periyar Ramasamy put forward his demand for Dravidanad. This was two years before Mohamed Ali Jinnah set out the formal demand for Pakistan at the Lahore conference. In 1944, the Justice party changed its name to Dravida Kalagam and C.N.Annadurai functioned as its first General Secretary.

But, in the end, Periyar E.V.Ramasamy , the undoubted father of the Dravidian movement failed to deliver on the promise of Dravida Nadu. E.V.R. failed where Mohamed Ali Jinnah succeeded. It is true that the strategic considerations of the ruling colonial power were different in each case - and this had something to do with Jinnah�s success. But, nevertheless, if ideology is concerned with moving a people to action, the question may well be asked: why did E.V.R�s ideology fail to deliver Dravida Nadu?

Two aspects may be usefully considered. One was the attempt of the Dravida movement to encompass Tamils, Malayalees, Kannadigas and all Dravidians and mobilise them behind the demand for Dravida Nadu. Unsurprisingly, the attempt to mobilise across what were in fact separate national formations failed to take off.

It was one thing to found a movement which rejected casteism. It was quite another thing, to mobilise peoples, speaking different languages with different historical memories, into an integrated political force in support of the demand for Dravida Nadu.

At the same time, the Aryan/Dravidian divide propagated by German scholars such as Max Weber, encouraged by the British, and espoused by E.V.R. paid insufficient attention to the underlying links that the Tamil people had with the other nations of the Indian sub continent .

That was not all. E.V.R extended his attack on casteism to an attack on Hinduism - and indeed to all religions as well. Periyar E.V.R threw out the Hindu child with the Brahmin bath water.

E.V.R was right to extol the virtues of pahuth arivu, common sense. He was right to attack mooda nambikai, foolish faith. His rationalism was often a refreshing response to religious dogma and superstition in a quasi feudal society. His attack on casteism, his social reform movement and his Self Respect Movement in the 1920s infused a new dignity, thanmaanam, amongst the Tamil people and laid the foundations on which Tamil nationalism has grown.

It was the pioneering work of EVR that led to the growth of the Dravida Munetra Kalagam (DMK) led by C.N.Annadurai and later by M.Karunanidhi , to the All India Dravida Munetra Kalagam led by M.G.Ramachandran and the Marumalarchi Dravida Munetra Kalagam (MDMK) led by V.Gopalasamy .

".. Periyar's Dravidianisin, which was but Tamil nationalism, has to be seen as a response to the homogenising drives of the Brahmin-Bania combine which, Periyar judged rightly, would shape the new Indian nation-state. Periyar opposed to the coopting logic of Brahminism and the centralizing dynamic of the modern nation-state, the notion of a free and rational Tamil society that would in time evolve into a Tamil nation..." Interrogating 'India' - a Dravidian Viewpoint - V.Geetha and S.V.Rajadurai

But, having said that, the refusal of EVR to recognise that casteism was one thing, Hinduism another and spiritualism, perhaps, yet another, proved fatal. His belligerent atheism failed to move the Tamil people. In the result even within Tamil Nadu, EVR's Dravida Kalagam became marginalised, and the DMK which was an offshoot of the Dravida Kalagam and the ADMK which was an offshoot of the DMK, both found it necessary to play down the anti religious line and adopt instead a �secular� face. One consequence of EVR�s atheism was that spirituality in Tamil Nadu came to be exploited as the special preserve of those who were opposed to the growth of Tamil nationalism.

Furthermore, the anti-Brahmin movement tended to ignore the many caste differences that existed among the non-Brahmin Tamils and failed to address the oppression practised by one non-Brahmin caste on another non-Brahmin caste .

"... The cultural nationalist agenda of the Dravidian parties, and its moral claims for social justice for the common people (to be achieved by modest redistribution, or 'sharing' through welfare programmes rather than by changing the distribution of assets ) , was immensely successful ... Culture war, in other words, is class war by other means: the one is a displacement of the other' . .. but the non-Brahmin category proved too amorphous to become the basis of an enduring cleavage... The dividing lines between individual backward castes and between the 'backward' castes and the scheduled castes create divisions that are salient in the everyday experience of the majority of the population, and this makes broader categories, such as that of the backward castes, difficult to invoke as the basis of political action..." The Changing Politics of Tamil Nadu in the 1990s - John Harriss and Andrew Wyatt

It is a failure that continues to haunt the Tamil national movement even today. Caste divides and fragments the togetherness of the Tamil people .

" The Tamil nation is a political community, a grand solidarity. To maintain its solidarity, the Tamil nation has to remove all sorts of divisions that causes dissension and discord among its members. The Caste System is such a pernicious division that has plagued our society for thousands of years." S.M.Lingam on Tamil Nationalism & the Caste System - Swami Vivekananda and Saint Kabir

Support for the positive contributions that E.V.R. made in the area of social reform and to rational thought, should not prevent an examination of where it was that he went wrong. Again, it may well be that E.V.R. represented a necessary phase in the struggle of the Tamil people and given the objective conditions of the 1920s and 1930s, E.V.R was right to focus sharply on the immediate contradiction posed by 'upper' caste dominance and mooda nambikai. But in the 21st century, there may be a need to learn from E.V.R. - and not simply repeat that which he said or did.

It is not surprising that in Tamil Nadu poverty and corruption continue to weaken confidence in existing political structures.

"As programmes and reforms failed... repression appeared as the direct method of dealing with peasant unrest. Between 1975 and 1982, the police forces launched a series of operations against the Naxals. Either in what was called encounters or under police custody nineteen young men died and about 250 people were jailed. The green turbanned peasants led by Narayanaswamy Naidu launched agitations in 1972 and 1980. In Coimbatore, Dharmapuri, South Arcot and Madurai there were serious disturbances.. Between 1972 and 1982 fifty four peasants were killed in police firings and more than 25,000 were taken into custody." (History of Tamil Nadu 1565 - 1982: Professor K.Rajayyan, Head of the School of Historical Studies, M.K.University, Madurai - Raj Publishers, Madurai, 1982)

"India's Tamilians have always considered themselves a distinct race. Distinct from the Aryans who, history tells us, displaced their Dravidian ancestors after the conquest of the Indus-Valley civilizations. The Tamil language and script are perhaps of greater antiquity than Sanskrit and have remained largely free of its influence. Not to speak of Tamil literature which may be the richest India has to offer, both in depth and scope. The Stink of Untouchability Which is why Tamilians break into passionate protest when any Tamilian anywhere be perceived as being under siege. Sri Lanka offering a prime example, as well as the situation of Tamilians in Malysia. So, would it be right to infer that Tamilian civilizational homogeneity brooks no breach? Wrong .... Interestingly, Tamil Nadu is governed by a largely (Other Backward Classes) OBC-led formation-intermediate social castes who vanquished the caste oppression of the Tamil Brahmins during the social reform agitations led by Periyar and Annadurai, mentors of the current leadership.Yet, such is India's social reality that those who fought and defeated Brahminism seem at best lukewarm in defeating caste oppression of the Pillai OBCs in Uthapuram against fellow dalit Tamils.."

In the island of Sri Lanka, the national identity of the Tamil people grew through a process of opposition to and differentiation from the Buddhist Sinhala people. The Sinhala people trace their origins in the island to the arrival of Prince Vijaya from India , around 500 B.C. and the Mahavamsa, the Sinhala chronicle of a later period (6th Century A.D.) records that Prince Vijaya arrived on the island on the same day that the Buddha attained Enlightenment in India. However, the words of the Sinhala historian and Cambridge scholar, Paul Peiris represent an influential and common sense point of view:

"..it stands to reason that a country which was only thirty miles from India and which would have been seen by Indian fisherman every morning as they sailed out to catch their fish, would have been occupied as soon as the continent was peopled by men who understood how to sail... Long before the arrival of Prince Vijaya, there were in Sri Lanka five recognised isvarams of Siva which claimed and received the adoration of all India. These were Tiruketeeswaram near Mahatitha; Munneswaram dominating Salawatte and the pearl fishery; Tondeswaram near Mantota; Tirkoneswaram near the great bay of Kottiyar and Nakuleswaram near Kankesanturai. " (Paul E. Pieris: Nagadipa and Buddhist Remains in Jaffna : Journal of Royal Asiatic Society, Ceylon Branch Vol.28)

The Pancha Ishwarams of Eelam were important landmarks of the country and S.J.Gunasegaram's ' Trincomalee - Holy Hill of Siva ' reveals the antiquity of Trincomalee as an ancient Hindu shrine.

The Tamil people and the Sinhala people were brought within the confines of a single state by the British. The struggle for freedom from British colonial rule, did lead Tamil leaders such as Ponnambalam Ramanathan and Ponnambalam Arunachalam to work together with their Sinhala counterparts in the Ceylon National Congress. But it was largely a dialogue between the English speaking Tamil middle class and its English speaking Sinhala counterpart.

Professor Kailasapathy in a paper presented at a Social Scientists Association Seminar in Colombo , traced the growth of Tamil consciousness in Eelam from the time of British rule, through independence and upto 1979. The paper affords many insights into the continuing growth of Tamil Consciousness today, not only in Eelam but in the Tamil diaspora as well:

"Both the reformers and the revivalists came from the Hindu upper castes, but while the former were not only English educated but also used that language for their livelihood and for acquiring social status, the latter were primarily traditional in their education and used their mother tongue for their livelihood and social communication.. .most of them wrote in English... In doing so they probably had a particular audience in mind, an audience to whom they wanted to prove the antiquity and greatness of their tradition...In contrast the revivalists were mainly highly erudite in their mother tongue and wrote in it..."

The Pan Sinhala Executive Committee of the Ceylon State Council in 1936 and the formation of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress led by G.G.Ponnambalam were some of the early manifestations of the growth of a separate Sinhala nationalism and a separate Tamil nationalism in the political arena of the island of Ceylon (as it then was known).

It was a Tamil nationalism which eventually found expression in the formation of the Ilankai Thamil Arasu Katchi led by S.J.V.Chelvanayakam in 1949 and later in the 1970s in the Tamil armed resistance movement , led today by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and Velupillai Pirabaharan .

"The historical storm of the liberation struggle is uprooting age old traditions that took root over a long period of time in our society... The ideology of women liberation is a child born out of the womb of our liberation struggle... Our women are seeking liberation from the structures of oppression deeply embedded in our society. This oppressive cultural system and practices have emanated from age old ideologies and superstitions. Tamil women are subjected to intolerable suffering as a consequence of male chauvinistic oppression, violence and from the social evils of casteism and dowry." ( Velupillai Pirabaharan, 1992, 1993)

That the armed resistance movement of the Tamil people should have originated in Tamil Eelam and not in Tamil Nadu is not altogether surprising. It is the nature of the discrimination and oppression which often determines the nature of the response.

"Liberty is the life breath of a nation; and when life is attacked, when it is sought to suppress all chance of breathing by violent pressure, then any and every means of self preservation becomes right and justifiable...It is the nature of the pressure which determines the nature of the resistance." ( Aurobindo in Bande Mataram, 1907)

Suffering unites a people and the suffering of the Tamil people in the island of Sri Lanka, in their struggle for freedom and justice, has also served to bring together the Tamils living in many lands. Pongu Tamil Vizhas and Maveerar Naals around the globe have brought together Tamils who had originally come not only from Tamil Eelam but also from Tamil Nadu - the Tamil homeland.

The Tamil cultural renaissance of the second half of the 19th century and of the early 20th century, on the foundations laid by Swaminatha Iyer from Tamil Nadu and Thamotherampillai from Tamil Eelam; the rise of the Dravida Tamil national movement of the first half of the 20th century led by Periyar and C.N.Annadurai ; the internationalisation of Tamil studies by the monumental efforts of Father Thaninayagam from Tamil Eelam; the armed struggle for freedom in Tamil Eelam symbolised by the Chola Tiger emblem and led by Velupillai Pirabakaran ; and the answering responses in Pongu Tamil Vizhas and Maveerar Naals around the world, with the active participation of Tamils who traced their origins to both Tamil Nadu and Tamil Eelam, are but tributories flowing into one river - the river of the growing togetherness of the Tamil nation - and this river is not about to flow backwards.

"... தமிழ் இன்று அதன் எல்லைகளைத் தாண்டி கண்டங்களையும் கடல்களையும் தாண்டி தேசங்களைக் கடந்த தேசியமாக பர்ணமித்துள்ளது.... நாம் எங்கும் சிறகுடன் பறந்தாலும் தமிழுக்கென, தமிழருக்கென ஒரு நாடு மலர்ந்திட காலம்தோறும், தேசம்தோறும் தமிழ்செய்வோம்.." M.Thanapalasingham in காலம்தோறும் தமிழ், 2009

Here, not many will question that the future of the Tamil nation is interlinked with the other nations of the Indian subcontinent. In 1973, Kamil Zvebil , Professor in Tamil Studies at Charles University, Prague wrote in 'The Poets and the Powers', of the Tamil contribution in shaping and moulding the Indian synthesis :

"...Many and variegated are the contributions of the Tamils of South India to the treasures of human civilisation, the early classical love and war poetry , the architecture of the Pallavas , the deservedly famous South Indian bronzes of the Chola period , the well known Bharata Natyam dance , the philosophy of Saiva Siddhanta , the magnificent temples of the South - for more than two thousand years have the Tamils been contributing to Indian culture and taking part in shaping and moulding the great Indian synthesis."

Sylvain Levi George Coedes and La Valee Poissin wrote in the 'The Indianisation of South East Asia' in 1975:

"Without being aware of it, India determined the history of a good portion of mankind. She gave three quarters of Asia a God, a religion, a doctrine, a art. She gave them her sacred language, literature and her institutions... All the regions contributed to this expansion and civilisation, but it was the South that played the greatest role ."

Said that, it has also to be said that the Indian 'Union' will survive only if it reinvents itself as a free and equal association of independent states .

"... Endless platitudes abound about (Indian) 'national unity' and the catholicity and durability of 'Indian culture'... (but) our national identity has not been forged through a definitive articulation of a national-popular collective will as has been claimed... It seems urgent, then, that we pose certain crucial and important questions about ourselves: How are we a 'nation'? What are the historical and cultural markers of our 'nation-hood'? Is our national identity the product of a `national popular will'?... The Indian state is of course determined to prevent these questions from being asked. In this context it seems logical that we ask: What is the 'Indian' nation we seek to preserve? These questions were posed with great alacrity and boldness by the ideologues of the Dravidian movement in Tamilnadu (among others) during the early decades of this century..." Interrogating 'India' - a Dravidian Viewpoint - V.Geetha and S.V.Rajadurai

The European Union is a pointer to the direction that the Indian 'Union' will need to take if it is not to implode in the way that the Soviet Union did in the 1990s. Peaceful evolution is necessary if bloody revolution is to be avoided. The days of an Indian empire with a ruling Indira Gandhi - Rajiv Gandhi - Sonia Gandhi - Rahul Gandhi dynasty presiding over a caste riven quasi feudal society with an English speaking elite are numbered.

"... India's Prime Minister Manmohan Singh says his country is losing the battle against Maoist rebels. Mr Singh told a meeting of police chiefs (14 September 2009) from different states that rebel violence was increasing and the Maoists' appeal was growing... The rebels operate in 182 districts in India, mainly in the states of Jharkhand, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh , Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and West Bengal. In some areas they have virtually replaced the local government and are able to mount spectacular attacks on government installations. " India is 'losing Maoist battle' says Indian Prime Minister, BBC Report, 15 September 2009

Arundhati Roy was right to point out in 2007 -

"..What we�re witnessing is the most successful secessionist struggle ever waged in independent India � the secession of the middle and upper classes from the rest of the country. It�s a vertical secession, not a lateral one. They�re fighting for the right to merge with the world�s elite somewhere up there in the stratosphere... to equate a resistance movement fighting against enormous injustice with the government which enforces that injustice is absurd. The government has slammed the door in the face of every attempt at non-violent resistance. When people take to arms, there is going to be all kinds of violence � revolutionary, lumpen and outright criminal. The government is responsible for the monstrous situations it creates... There is a civil war in Chhattisgarh sponsored, created by the Chhattisgarh government, which is publicly pursing the Bush doctrine: if you�re not with us, you are with the terrorists. The lynchpin of this war, apart from the formal security forces, is the Salva Judum � a government-backed militia of ordinary people forced to become spos (special police officers). The Indian State has tried this in Kashmir , in Manipur , in Nagaland . Tens of thousands have been killed - thousands tortured, thousands have disappeared. Any banana republic would be proud of this record. Now the government wants to import these failed strategies into the heartland... I have no doubt that the Maoists can be agents of terror and coercion too. I have no doubt they have committed unspeakable atrocities. I have no doubt they cannot lay claim to undisputed support from local people � but who can? Still, no guerrilla army can survive without local support. That�s a logistical impossibility. And the support for Maoists is growing, not diminishing. That says something. People have no choice but to align themselves on the side of whoever they think is less worse.does this mean that people whose dignity is being assaulted should give up the fight because they can�t find saints to lead them into battle?. " 'It�s outright war and both sides are choosing their weapons'- Arundhati Roy March 2007

There is a compelling need for those concerned to preserve the Indian 'Union' to pay renewed attention to that which Pramatha Chauduri said many decades ago -

"... As children, we read in the Hitopodesa that at night birds from all directions would gather on a shimul tree on the banks of the Godavari. Why? To cackle for a while and then go off to sleep. Cackle in this context means to discuss the politics of the birdworld. We, too, in this dark, night time of India's history go to the Congress meet to cackle for three or four days and then snore. We can cackle together because, thanks to the education conferred by the British, we all have the same dialect. I am not saying that this dialect is all that our lips utter or our minds. All I want to suggest is that behind the Congress patriotism, there is only one kind of mind and that mind is bred on English text books. We all have that kind of mind, but under it is the mind which is individual for all nations and different from nation to nation. And our civilisation will emerge from the depth of that mind. ...It is not a bad thing to try and weld many into one but to jumble them all up is dangerous, because the only way we can do that is by force. If you say that this does not apply to India, the reply is that if self determination is not suited to us, then it is not suited at all to Europe. No people in Europe are as different, one from another, as our people. There is not that much difference between England and Holland as there is between Madras and Bengal. Even France and Germany are not that far apart ." For Province, Read Nation - Pramatha Chauduri, 1920

There is a scholarly literature in Tamil dating back to the early centuries of the Christian era. The language is of Dravidian origin. The Dravidians were the founders of one of the world's most ancient civilizations , which already existed in India sometime before 1000 BC when the Aryans invaded the sub-continent from the north.

The Aryans, who spoke the Sanskrit language, pushed the Dravidians down into south India. Today 8 of the languages of northern and western India (including Hindi) are of Sanskrit origin, but Sanskrit itself is only spoken by Hindu Brahman priests in temple worship and by scholars. In southern India, 4 languages of Dravidian origin are spoken today. Tamil is the oldest of these. The History of Tamil Nadu begins with the 3 kingdoms, Chera , Chola and Pandya , which are referred to in documents of the 3rd century BC. Some of the kings of these dynasties are mentioned in Sangam Literature and the age between the 3rd century BC and the 2nd century AD is called the Sangam Age. At the beginning of the 4th century AD the Pallavas established their rule with Kanchipuram as their capital. Their dynasty, which ruled continously for over 500 years, left a permanent impact on the history of Tamil Nadu, which was during this period virtually controlled by the Pallavas in the north and the Pandyas in the south. In the middle of the 9th century a Chola ruler established what was to become one of India's most outstanding empires on account of its administrative achievements (irrigation, village development) and its contributions to art and literature. The Age of the Cholas is considered the golden age of Tamil history. Towards the end of the 13th century the Cholas were overthrown by the later Pandyas who ruled for about a century and were followed by the Vijayanagara Dynasty, whose greatest ruler was Krishnadeva Raya (1509-1529), and the Nayaks of Madurai and Tanjore.

The Colonial Age opened in the 17th century. In 1639 the British East India Company opened a trading post at the fishing village of Madraspatnam, today Madras, the capital of Tamil Nadu. In 1947, India achieved Independence. The overwhelming majority of the population of Tamil Nadu is Hindu, with active Christian and Muslim minorities.

The Modern Tamil Novel: Changing Identities and Transformations

- First Online: 31 March 2017

Cite this chapter

- Lakshmi Holmström 3

315 Accesses

This essay examines the articulation of voices and genres of the Indian contemporary multilingual canon by introducing Tamil fiction and the impact of translation on it. Holmström reconstructs the development of the modern novel in Tamil in the past decades, discussing in particular some authors who have been deemed to be extremely influential on the course of recent Tamil literary history. Ashokamitran, Sundara Ramaswamy, Ambai, and Bama have narrated the story of the individual in times of political and social change both in Tamil Nadu and in India, each with their own innovative point of view, including feminist, Dalit, and diasporic perspectives. Many important works by these four novelists have been translated into other Indian languages as well as into English. Some have been translated into European languages such as French, Spanish, and German. Yet some translations have taken on a life of their own, while others have not. In the essay’s final remarks, the relationship between the original text and its successful translation is explored.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: Intellectual Traditions of India in Dialogue with Mikhail Bakhtin

“No Blind Admirer of Byron”: Imperialist Rivalries and Activist Translation in Júlio Dinis’s Uma Família Inglesa

Self-Translation and Exile in the Work of Catalan Writer Agustí Bartra. Some Notes on Xabola (1943), Cristo de 200.000 brazos (Campo de Argelés) (1958) and Crist de 200.000 braços (1968)

Ambai (1992) A Purple Sea , translated with an introduction by Lakshmi Holmström, Madras: Affiliated East-West Press.

Google Scholar

Ambai (2006) In a Forest, a Deer , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Ambai (2012) Fish in a Dwindling Lake , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, New Delhi: Penguin India.

Ashokamitran (1993) Water , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, London:Heinemann; 2nd edition, New Delhi: Katha, 2001.

Bama (2000) Karukku , translated with an introduction by Lakshmi Holmström, Chennai: Macmillan India, 2nd edition, New Delhi: OUP India, 2012.

Bama (2005) Sangati: Events , translated with an introduction by Lakshmi Holmström, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Cheran (2013) In a Time of Burning , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, Todmorden: Arc.

Doraiswamy, T.K. (1974) ‘Ashokamitranin Tannir’ in Pakkiamuttu T. (ed.) Vidudalaikkuppin Tamil Naavalkal . Madras: Christian Literature Society, n.p.

Ebeling, S. (2010) Colonizing the Realm of Words: The Transformation of Tamil Literature in Nineteenth-Century South India , Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Gauthaman, R. (1995) ‘Olivattangal Tevai Illai’ [‘We Have No Need for Haloes’] in India Today Annual , pp. 96–98.

Pudumaippittan (1954) Pudumaippittan Katturaigal , Madras: Star Publications.

Ramaswamy, S. (2013) Children, Women, Men , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, New Delhi: Penguin India.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Norwich, England

Lakshmi Holmström

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lakshmi Holmström .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

English and Anglophone Literatures, University of Naples ‘L’Orientale’, Naples, Italy

Rossella Ciocca

School of English, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

Neelam Srivastava

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Holmström, L. (2017). The Modern Tamil Novel: Changing Identities and Transformations. In: Ciocca, R., Srivastava, N. (eds) Indian Literature and the World. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54550-3_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54550-3_6

Published : 31 March 2017

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-137-54549-7

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-54550-3

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Skip to main content

- Select your language English हिंदी

Social Share

The culture and history of the tamils.

Author: Sastri, K.A. Nilakanta

Publisher: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay, Calcutta

Source: Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi

Type: E-Book

Received From: Archaeological Survey of India

- Dublin Core View

- Parts of PDF & Flipbook

Indian Institute of Technology Bombay

- Phone . [email protected]

- Email . +54 356 945234

Indian Culture App

The Indian Culture Portal is a part of the National Virtual Library of India project, funded by the Ministry of Culture, Government of India. The portal has been created and developed by the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay. Data has been provided by organisations of the Ministry of Culture.

Email Id : [email protected]

Indian Culture and Tradition Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on indian culture and tradition.

India has a rich culture and that has become our identity. Be it in religion, art, intellectual achievements, or performing arts, it has made us a colorful, rich, and diverse nation. The Indian culture and tradition essay is a guideline to the vibrant cultures and traditions followed in India.

India was home to many invasions and thus it only added to the present variety. Today, India stands as a powerful and multi-cultured society as it has absorbed many cultures and moved on. People here have followed various religion , traditions, and customs.

Although people are turning modern today, hold on to the moral values and celebrates the festivals according to customs. So, we are still living and learning epic lessons from Ramayana and Mahabharata. Also, people still throng Gurudwaras, temples, churches, and mosques.

The culture in India is everything from people’s living, rituals, values, beliefs, habits, care, knowledge, etc. Also, India is considered as the oldest civilization where people still follows their old habits of care and humanity.

Additionally, culture is a way through which we behave with others, how softly we react to different things, our understanding of ethics, values, and beliefs.

People from the old generation pass their beliefs and cultures to the upcoming generation. Thus, every child that behaves well with others has already learned about their culture from grandparents and parents.

Also, here we can see culture in everything like fashion , music , dance , social norms, foods, etc. Thus, India is one big melting pot for having behaviors and beliefs which gave birth to different cultures.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Indian Culture and Religion

There are many religions that have found their origin in age-old methods that are five thousand years old. Also, it is considered because Hinduism was originated from Vedas.

Thus, all the Hindu scriptures that are considered holy have been scripted in the Sanskrit language. Also, it is believed that Jainism has ancient origin and existence in the Indus valley. Buddhism is the other religion that was originated in the country through the teachings of Gautam Buddha.

There are many different eras that have come and gone but no era was very powerful to change the influence of the real culture. So, the culture of younger generations is still connected to the older generations. Also, our ethnic culture always teaches us to respect elders, behave well, care for helpless people, and help needy and poor people.

Additionally, there is a great culture in our country that we should always welcome guest like gods. That is why we have a famous saying like ‘Atithi Devo Bhava’. So, the basic roots in our culture are spiritual practices and humanity.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Drama Criticism › Indian Literary Theory and Criticism

Indian Literary Theory and Criticism

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on November 13, 2020 • ( 0 )

The Western tradition of literary theory and criticism essentially derives from the Greeks, and there is a sense in which Plato, Aristotle, and Longinus mark out positions and debates that are still being played out today. At a moment when we are questioning the sufficiency of such Western critical methods to make sense of the plethora of literatures produced by the world’s cultures, it may be useful to remind ourselves that other equally ancient classical critical traditions exist. There is an unbroken line of literary theory and criticism in Indian culture that goes back at least as far as the Western tradition. Indian criticism constitutes an important and largely untapped resource for literary theorists, as the Indian tradition in important respects assigns a more central role to literature than the Greek tradition does.

While explicit literary theory in India can be traced as far back as the fourth century b.c.e., placing Indian critical theory at the same time as Aristotle and Plato, there is much discussion of poetic and literary practice in the Vedas, which developed over the period 1500 BCE-500 BCE. In India, literary theory and criticism was never isolated simply as an area of philosophy; the practice and appreciation of literature was deeply woven into religion and daily life. While Plato argued in The Republic that the social role of the poet was not beneficial, Ayurveda , the science of Indian medicine, believed that a perfectly structured couplet by its rhythms could literally clean the air and heal the sick. We know this perfect couplet today as the mantra , literally “verse.” Sanskrit poetry has to be in the precise meter of the sloka, comparable to the heroic couplet, to be able to speak to the hearer. The Vedic Aryans therefore worshipped Vach, the goddess of speech or holy word (De Bary et al. 5-6). Like the Greeks, Indian critics developed a formalistic system of rules of grammar and structure that were meant to shape literary works, but great emphasis was also laid on the meaning and essence of words. This became the literary- critical tenet of rasadhvani . In contrast to Plato’s desire to expel poets and poetry from his republic, poetry in India was meant to lead individuals to live their lives according to religious and didactic purposes, creating not just an Aristotelian “purgation of emotions” and liberation for an individual but a wider, political liberation for all of society. Society would then be freed from bad ama , or “ill will” and “feelings that generate bad karma ,” causing individuals to live in greater harmony with each other. This essay outlines the various systems that aimed at creating and defining this liberatory purpose in literature through either form or content.

The three major critical texts that form the basis of Sanskrit critical theory are Bharata’s Natyasastra (second century C.E.), Anandavardhana’s Dhvanyaloka , which was the foundation of the dhvani school of criticism, and Bhartrhari’s theory of rasa in the Satakas, the last two dating to about c.E. 800. We shall discuss these works in the order in which the three genres—poetry, drama, and literary criticism—developed. Interestingly, these works asked questions that sound surprisingly contemporary. For example, a major question concerned whether “authority” rested with the poet or with the critic, that is, in the text or in the interpretation. In his major critical treatise, Dhvanyaloka, Anandavardhana concluded that “in the infinite world of literature, the poet is the creator, and the world changes itself so as to conform to the standard of his pleasure” (Sarma 6). According to Anandavardhana, kavirao (“poet”) is equated with Prajapati (“Creator”). The poet creates the world the reader sees or experiences. Thus, Anandavardhana also jostled with the issue of the role of the poet, his social responsibility, and whether social problems are an appropriate subject for literature. For Anandavardhana, “life imitated art”; hence the role of the poet is not just that of the “unacknowledged legislator of the world”—as P. B. Shelley stated (Shelley’s Critical Prose , ed. Bruce R. McElderry, Jr., 1967, 36)—not just that of someone who speaks for the world, but that of someone who shapes social values and morality. The idea of sahrdaya (“proper critic”), “one who is in sympathy with the poet’s heart,” is a concept that Western critics from I. A . Richards through F. R. Leavis to Stanley Fish have struggled with. In the Indian tradition, a critic is the sympathetic interpreter of the poet’s works.

But why interpretation? Why does a community that reads the works of its own writers need interpretation? How does the reader read, and what is the role of criticism? Indian philosophers and priests attempted to answer these questions in terms of the didactic purpose of literature as liberation. As we shall see, rasadhvani approximated closely to the Indian view of life, detachment from emotions that would cause bad karma , purgation of harmful emotions, and the subsequent road to moksha, “liberation.” Twentieth-century critics such as K. R. Srinivasa Iyengar and Kuppuswami Sastriar (both South Indians, the latter being the major Tamil interpreter of Sanskrit literary criticism) have brought about a revival of the rasadhvani schools of criticism. Similarly, Bengali writers such as Rabindranath Tagore were greatly influenced by the didactic purpose of literature that rasadhvani critics advocated.

To understand how these critical theories developed, we need to look briefly at the development of Indian literature. The Rig Veda is considered the earliest extant poem in the Indo-European language family and is dated anywhere between 2500 b .c .e . and 600 B.C.E. It does, however, make reference to kavya , “stanzaic forms,” or poetry, that existed before the Rig Veda itself. The word gatha , referring to Zoroastrian religious verses that are sung, also occurs frequently in the Rig Veda. Valmiki, the author of the Ramayana, is considered the first poet, but as we shall see, Valmiki is also considered the first exponent of poetic form. The period between 600-500 B.C.E. and c.E. 200 is labeled the epic period by Sarvepelli Radhakrishnan (the first president of the postcolonial Republic of India and the most prolific scholar of Indian philosophy and critical theory) because it saw the development of the great epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata (Radhakrishnan and Moore xviii). According to Radhakrishnan, the Bhagavad Gita, which is a part of the Mahabharata , ranks as the most authoritative text in Indian philosophical literature because it is considered to have been divinely revealed and because it apparently was noted down as it was revealed and therefore was not merely transmitted orally. In the Gita , Krishna and Arjuna philosophize about the role of the poet. The responsibility of maintaining order in the world is on the shoulders of the poet-sage, such as Janaka, for ordinary mortals tend to imitate the role model as portrayed by Janaka. Thus it is the poets who set the standards for the world to follow.

The period of Indian philosophy that spans more than a millennium from the early Christian centuries until the seventeenth century C.E. is considered the sutra period, or the period of treatises upon the religious and literary texts. It was this period that saw the rise of the many schools of literary criticism and interpretation. Radhakrishnan calls this the scholastic period of Indian philosophy, and it was in this period that interpretation became important. Sanskrit is the language in which the Vedas are written, and because the Vedas are the basis of the all-Indian Hindu tradition, all of India’s religious, philosophical, literary, and critical literature was written in Sanskrit. Sanskrit served as a lingua franca across regional boundaries but predominantly for the learned, upper classes and the Brahmins, who made up the priestly class. The Brahmins then interpreted the religious, literary, and critical texts for local individuals by using the indigenous languages.

While Sanskrit remained the language of religion in the south, local versions of the religious literature began to emerge in order to meet the needs of the South Indian people, who spoke predominantly Tamil or Telugu. It was not until the breakup of the Brahminical tradition in about the seventh century c.E. (Embree 228-29) that literary religious hymns emerged in Tamil. The Indian- English writer R. K. Narayan’s version of the Ramayana is based on the Tamil version by the poet Kamban in the eleventh century. Tamil literary criticism remained rooted in the classical Sanskrit critical tenets, however, as is evidenced by the continuance (even in the 1900s) of Dhvanyaloka criticism by Kuppuswami Sastri in Madras.

Early Indian criticism was “ritual interpretation” of the Vedas, which were the religious texts. Such ritual interpretation consisted in the analysis of philosophical and grammatical categories, such as the use of the simile, which was expounded upon in the Nirutka of Yasaka, or in applying to a text the grammatical categories of Panini’s grammar. This critical method, which consisted in the analysis of grammar, style, and stanzaic regularity, was called a sastra, or “science.” Panini’s Sabdanusasana [Science of sabda, or “words”] and the Astadhyayi [Eight chapters of grammatical rules] (Winternitz 422) are perhaps the oldest extant grammars, dated by various scholars to about the beginning of the Christian era. Alankara sastra is “critical science,” which emanated from Panini’s grammar and was dogmatic and rule-governed about figures of speech in poetry. The word alankara means “ornament” (Dimock 120), and as in Western rhetorical theory, this critical science consisted of rules for figurative speech, for example, for rupaka (“simile”), utpreksa (“metaphor”), atisya (“hyperbole”), and kavya (“stanzaic forms”). As Edwin Gerow has noted in his chapter “Poetics of Stanzaic Poetry,” in The Literature of India :

Alankara criticism passes over almost without comment the entire range of issues that center around the origin of the individual poem, its context, its appreciation, and its authorship. It does not aim at judgement of individual literary works or at a theory of their origin. (Dimock 126)

The idea of criticism as a science is rooted in the centuries- old Indian belief that vyakarana, “grammar,” is the basis of all education and science. Rules were to be learned by rote, as were declensions and conjugations, as a means of developing discipline of the mind.

Patanjali, whose work is ascribed to the second century b .c .e ., believed that a child must study grammar for the first twelve years; in fact, before studying any science, one must prepare for it by studying grammar for twelve years (see Winternitz 420). Since grammar lay the foundation of all other study, a series of rule-governed disciplines arose, each of which had categories and classifications to be learned by heart. These disciplines were arthasastra , a grammar of government or political science; rasa-sastra, the science of meaning or interpretation specifically for poetry, that is, literary criticism; natyasastra, the science of drama or dramaturgy; and sangitasastra, the science of music or musicology. Each was further broken down; for instance, musicology was divided into jatilaksana (“theory”), atodya (the “study of musical instruments”), susira (“song”), tala (“measure”), and dhruva (“rhythm”).

Poetry was most governed by the alankara , the rules of critical science; but since poetry existed before criticism, it in itself was generative of that criticism. Critics in the last few centuries b .c .e . believed that any association of word and memory having a special quality generates kavya . The creation of mnemonic rhymes was considered essential to poetry. Poetry was considered as having two qualities: alankara , here loosely translated to mean “formal qualities”; and guna , or “meaning” and “essence.”

According to the Alankara sastra , form has as much to do with creating the sphota, the “feeling evoked by a poem,” as the sphota has to do with creating meaning. Tradition has it that Valmiki, the sage wandering in the forest, heard a pair of Kaunca birds mating. When the male of that pair was shot down by a hunter, Valmiki heard the grieving of the female bird, which was metrically so perfect that Valmiki himself expressed her grief in the form of a perfect couplet. Ever since then Valmiki is considered the father of Sanskrit poetry as well as of poetic criticism. T he appropriate vibhav, “cause,” in this case grief, gives rise to the anubhav , “effect,” which in turn gives rise to perfect rhythmic expression. Valmiki, the author of the Ramayana , which is contemporaneous with the Mahabharata and belongs to the epic period, thus became the first poet to proclaim a critical tenet (see Sankaran 5-7).

Drama developed later in India than in Greece. Bharata’s Natyasastra [Science of drama], written about the second century C.E., not only lay down rules governing the creation of drama but also prepared the way for developing the theories of rasa, “meaning” or “essence.” Lee Siegel provides the following explanation in his important book on comedy in Indian drama:

Playing upon the literal meaning of rasa, “flavor” or “taste,” [Bharata] used the gastronomic metaphor to explain the dynamics of the aesthetic experiences. Just as the basic ingredient in a dish, when seasoned with secondary ingredients and spices, yields a particular flavor which the gourmet can savor with pleasure, so the basic emotion in a play, story, or poem, when seasoned with secondary emotions, rhetorical spices, verbal herbs, and tropological condiments, yields a sentiment which the connoisseur can appreciate in enjoyment. Love yields the amorous sentiment, courage the heroic mode. (7-8)

Thus Bharata provided formulas for producing the corresponding sentiments in the audience—recipes similar to Aristotle’s definition of “tragedy” and “comedy” but corresponding mostly with the means to produce homeostasis or balance in an audience by having the audience identify with certain rasas.

It is in the idea that literature is meant to cause a purgation of emotions and create a homeostasis in the audience that Indian criticism most approximates Aristotle’s theory of tragedy. This idea, though, is drawn from Indian philosophy and religious emphasis on liberation and freedom from bad karma. All literature is supposed to generate the feeling of moksha (“liberation”). Literature, more particularly drama or tragedy, must cause the purgation of the emotions of satva (“happiness”), rajas (“anger”), and tamas (“ignorance” or “laziness”) so as to free the soul from the body.

Bharata divided up the Natyasastra into hasya-rasa (“comedy”) and karuna-rasa (“tragedy”). The effect of drama can be obtained through, first, vibhava, the conditions provoking a specific emotion in the audience, which are controlled by alambana-vibhava, or identification with a person, as in Aristotle’s dictum of identification with the fall of a great man, and uddipana-vibhava , the circumstances causing the emotion to be evoked, as in the role of fate, pride, ambition, and so on; second, anubhava, or the technicalities of dramaturgy, gesture, expression, and so on; and third, vyabhicari , the buildup toward the dominant emotion, or as Aristotle would put it, the climax and subsequent catharsis. S. N. Dasgupta says that the theory of rasa

is based on a particular view of psychology which holds that our personality is constituted, both towards its motivation and intellection, of a few primary emotions which lie deep in the subconscious or unconscious strata of our being. These primary emotions are the amorous, the ludicrous, the pathetic, the heroic, the passionate, the fearful, the nauseating, the wondrous. (37)

Each of these, however, can be classified under the three primary emotions— satva, rajas, tamas . In freeing the audiences of these emotions, dramaturgy functions rather like karma yoga , or the “yoga of good deeds.”

The other major dramaturgist is Dandin. His poetics, entitled Kavyadarsa, dated to the eighth century c.E. (He also wrote the first prose romance, Dasa Kumara-carita. ) He, too, emphasized the gunas, or emotions generated by the “excellence of arrangement” (Mishra 202). Thus he attempted to bring rasas together with alankaras .

Literary criticism in India resulted from the historical developments in poetry and drama. It was Anandavardhana who, in writing the Dhvanyaloka , first explicitly developed a systematic literary criticism. This was the beginning of a formal literary criticism as opposed to the critical criteria that were generated alongside poetry and drama by the pronouncements of poets and dramatists. Anandavardhana, poet laureate of the court of Avantivaranan (C.E. 855-85), the king of Kashmir, turned to the centuries-old theory of dhvani and for the first time succeeded in establishing that dhvani , “sense as suggested by the form,” is the soul of poetry (Banerji 13). He chose to oppose the rasa theorists by going back to the emphasis on words laid by the grammarians, or Alankarikas , exponents of the Alankara school of criticism. Mishra describes the theory of dhvani as follows:

The theory of Dhvani was based on the Sphotavada of grammarians who held that the sphota is the permanent capacity of words to signify their imports and is manifested by the experience of the last sound of a word combined with the impressions of the experiences of the previous ones. The formulation of the doctrine of sphota was made in order to determine the significative seat of a word and the Alankarikas concerned themselves first with this grammatico-philosophical problem about the relation of a word to its connotation in order to get support, strong and confirmatory for their theory. (209)

Anandavardhana then ruled form over content and felt that the best poetry, especially dramatic poetry, suggested not only meaning but also poetic form.

To the alankaras Anandavardhana added slesa, “rules that governed the stylistic choices” of homonyms, synonyms, and so on. Slesa can be considered roughly equivalent to rules for parsing and metrical analysis. Two types of slesas are sabdaslesa, “word play” or “word sound,” and arthaslesa, “meaning and sense.” The closest analogy to this in Western terms is, perhaps, Robert Frost’s theory of “getting the sound of sense” ( Poetry and Prose, ed. Edward Connery Lathem and Lawrance Thompson, 1972,261).

In light of contemporary Western critical theory, there is a very interesting twist to the theories of Anandavardhana. For him, vyanjana, “revelation,” is an important characteristic of poetry. But the revelation rests in the heart of the “hearer,” that is, the reader. In other words, readers make meaning. To make this move to the reader, Anandavardhana turned to the grammarians. According to Mukunda Madhava Sharma, “The grammarians do not recognize any suggestive function of the expressive words but they hold that the syllables that we hear suggest an eternal and complete word within the heart of the hearer, which is called sphota and which alone is associated with meaning” (35). Therefore, if a poet follows the correct rules for combining sounds and words, meaning will follow from the sphota that exists within the reader.