- Joyner Library

- Laupus Health Sciences Library

- Music Library

- Digital Collections

- Special Collections

- North Carolina Collection

- Teaching Resources

- The ScholarShip Institutional Repository

- Country Doctor Museum

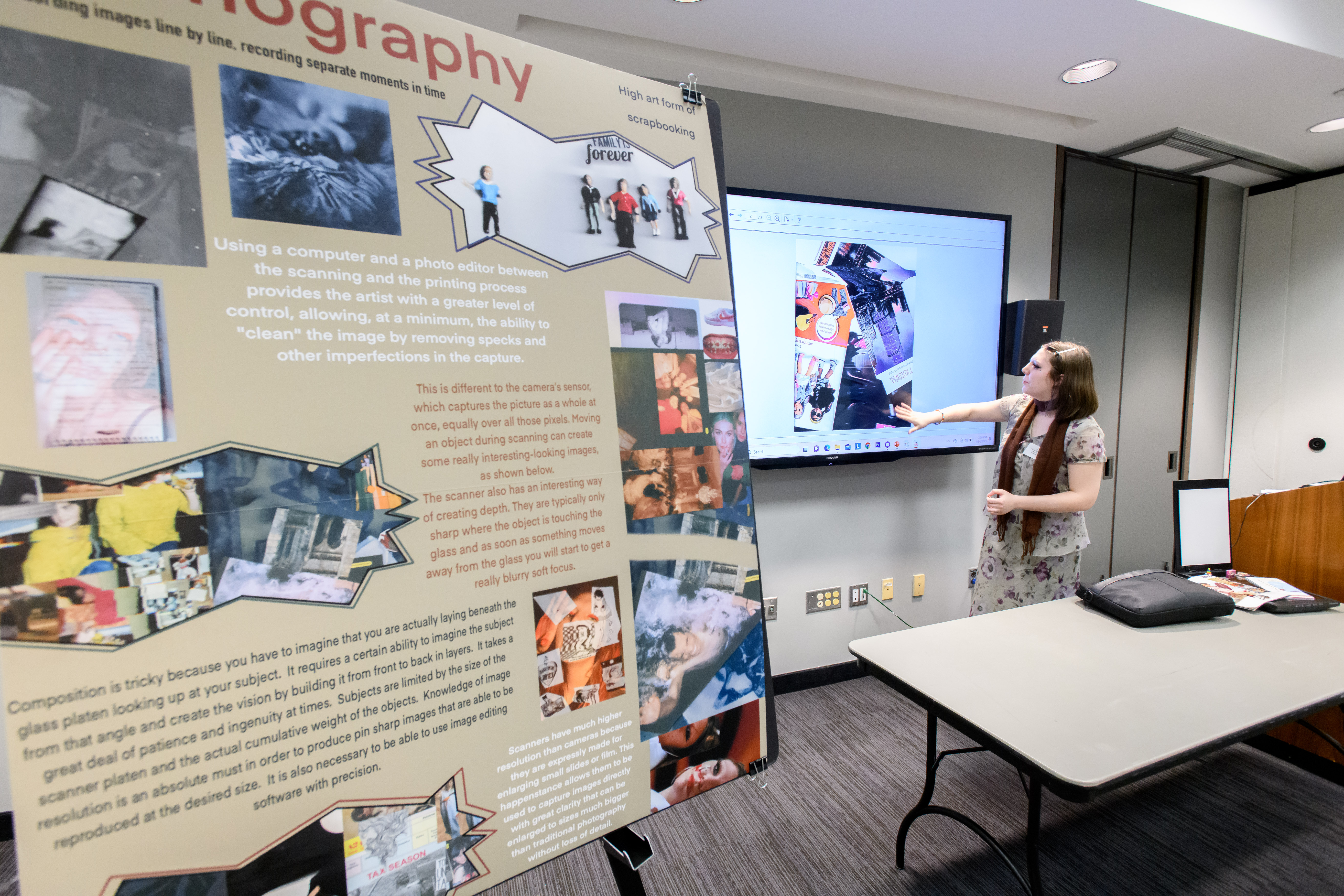

Presentations: Oral Presentations

- Poster Design

- Poster Content

- Poster Presentation

- Oral Presentations

- Printing & Archiving

Oral Presentations Purpose

An Oral Research Presentation is meant to showcase your research findings. A successful oral research presentation should: communicate the importance of your research; clearly state your findings and the analysis of those findings; prompt discussion between researcher and audience. Below you will find information on how to create and give a successful oral presentation.

Creating an Effective Presentation

Who has a harder job the speaker? Or, the audience?

Most people think speaker has the hardest job during an oral presentation, because they are having to stand up in a room full of people and give a presentation. However, if the speaker is not engaging and if the material is way outside of the audiences knowledge level, the audience can have a difficult job as well. Below you will find some tips on how to be an effective presenter and how to engage with your audience.

Organization of a Presentation

Introduction/Beginning

How are you going to begin? How are you going to get the attention of your audience? You need to take the time and think about how you are going to get started!

Here are some ways you could start:

- Ask the audience a question

- make a statement

- show them something

No matter how you start your presentation it needs to relate to your research and capture the audiences attention.

Preview what you are going to discuss . Audiences do not like to be manipulated or tricked. Tell the audience exactly what you are going to discuss, this will help them follow along. *Do not say you are going to cover three points and then try to cover 8 points.

At the end of your introduction, the audience should feel like they know exactly what you are going to discuss and exactly how you are going to get there.

Body/Middle

Conclusion/End

Delivery and Communication

Eye Contact

Making eye contact is a great way to engage with your audience. Eye contact should be no longer than 2-3 seconds per person. Eye contact for much longer than that can begin to make the audience member feel uncomfortable.

Smiling lets attendees know you are happy to be there and that you are excited to talk with them about your project.

We all know that body language says a lot, so here are some things you should remember when giving your presentation.

- Stand with both feet on the floor, not with one foot crossed over the other.

- Do not stand with your hands in your pockets, or with your arms crossed.

- Stand tall with confidence and own your space (remember you are the expert).

Abbreviated Notes

Having a written set of notes or key points that you want to address can help prevent you from reading the poster.

Speak Clearly

Sometimes when we get nervous we begin to talk fast and blur our words. It is important that you make sure every word is distinct and clear. A great way to practice your speech is to say tongue twisters.

Ten tiny tots tottered toward the shore

Literally literary. Literally literary. Literally literary.

Sally soon saw that she should sew some sheets.

Avoid Fillers

Occasionally we pick up fillers that we are not aware of, such as um, like, well, etc. One way to get rid of fillers is to have a friend listen to your speech and every time you say a "filler" have that friend tap you on the arm or say your name. This will bring the filler to light, then you can practice avoiding that filler.

Manage Anxiety

Many people get nervous when they are about to speak to a crowd of people. Below are ways that you can manage your anxiety levels.

- Practice, Practice, Practice - the more prepared you are the less nervous you will be.

- Recognize that anxiety is just a big shot of adrenalin.

- Take deep breaths before your presentation to calm you down.

Components of an Oral Research Presentation

Introduction

The introduction section of your oral presentation should consist of 3 main parts.

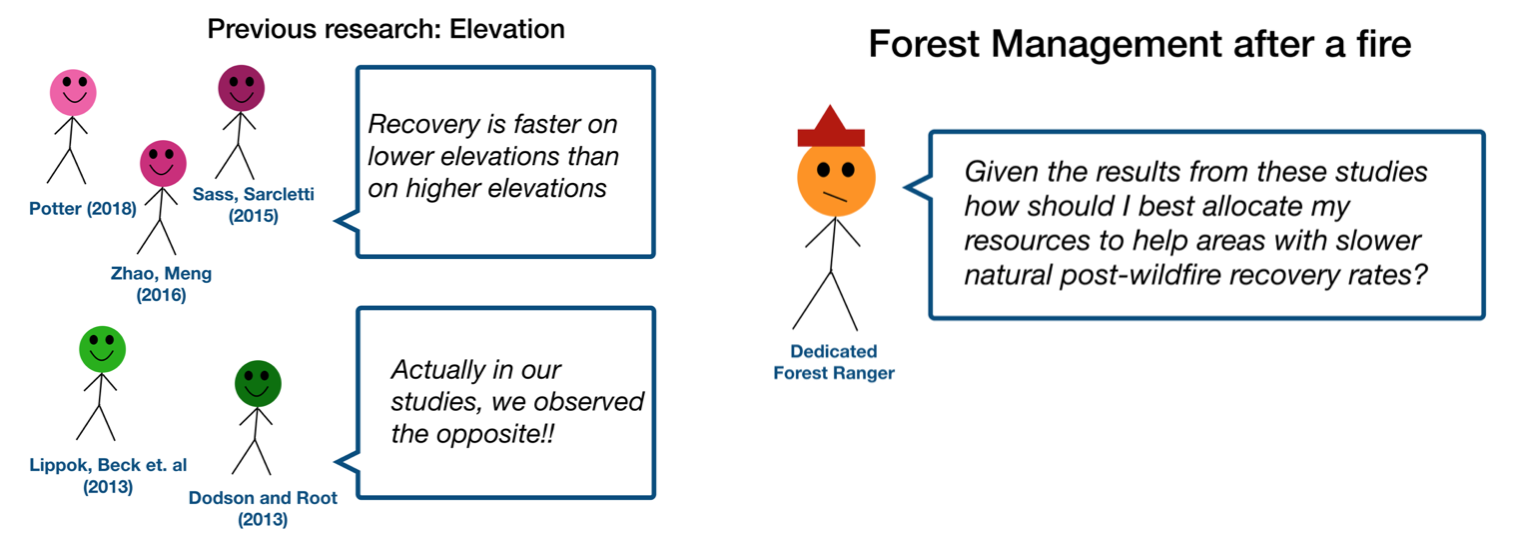

Part 1: Existing facts

In order to give audience members the "full picture", you first need to provide them with information about past research. What facts already exist? What is already known about your research area?

Part 2: Shortcomings

Once you have highlighted past research and existing facts. You now need to address what is left to be known, or what shortcomings exist within the current information. This should set the groundwork for your experiment. Keep in mind, how does your research fill these gaps or help address these questions?

Part 3: Purpose or Hypothesis

After you have addressed past/current research and have identified shortcomings/gaps, it is now time to address your research. During this portion of the introduction you need to tell viewers why you are conducting your research experiement/study, and what you hope to accomplish by doing so.

In this section you should share with your audience how you went about collecting and analyzing your data

Should include:

- Participants: Who or what was in the study?

- Materials/ measurements: what did you measure?

- Procedures: How did you do the study?

- Data-analysis: What analysis were conducted?

This section contains FACTS – with no opinion, commentary or interpretation. Graphs, charts and images can be used to display data in a clear and organized way.

Keep in mind when making figures:

- Make sure axis, treatments, and data sets are clearly labeled

- Strive for simplicity, especially in figure titles.

- Know when to use what kind of graph

- Be careful with colors.

Interpretation and commentary takes place here. This section should give a clear summary of your findings.

You should:

- Address the positive and negative aspects of you research

- Discuss how and if your research question was answered.

- Highlight the novel and important findings

- Speculate on what could be occurring in your system

Future Research

- State your goals

- Include information about why you believe research should go in the direction you are proposing

- Discuss briefly how you plan to implement the research goals, if you chose to do so.

Why include References?

- It allows viewers to locate the material that you used, and can help viewers expand their knowledge of your research topic.

- Indicates that you have conducted a thorough review of the literature and conducted your research from an informed perspective.

- Guards you against intellectual theft. Ideas are considered intellectual property failure to cite someone's ideas can have serious consequences.

Acknowledgements

This section is used to thank the people, programs and funding agencies that allowed you to perform your research.

Questions

Allow for about 2-3 minutes at the end of your presentation for questions.

It is important to be prepared.

- Know why you conducted the study

- Be prepared to answer questions about why you chose a specific methodology

If you DO NOT know the answer to a question

Visual Aids

PowerPoints and other visual aids can be used to support what you are presenting about.

Power Point Slides and other visual aids can help support your presentation, however there are some things you should consider:

- Do not overdo it . One big mistake that presenters make is they have a slide for every single item they want to say. One way you can avoid this is by writing your presentation in Word first, instead of making a Power Point Presentation. By doing this you can type exactly what you want to say, and once your presentation is complete, you can create Power Point slides that help support your presentation.

Formula for number of visual aids : Length of presentation divided by 2 plus 1

example: 12 minute presentation should have no more than 7 slides.

- Does it add interest?

- Does it prove?

- Does it clarify?

- Do not read the text . Most people can read, and if they have the option of reading material themselves versus listen to you read it, they are going to read it themselves and then your voice becomes an annoyance. Also, when you are reading the text you are probably not engaging with the audience.

- No more than 4-6 lines on a slide and no more than 4-6 words in a line.

- People should be able to read your slide in 6 seconds.

- << Previous: Poster Presentation

- Next: Printing & Archiving >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 9:02 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ecu.edu/c.php?g=637469

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare and...

How to prepare and deliver an effective oral presentation

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

- 2 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin; Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- luciahartigan{at}hotmail.com

The success of an oral presentation lies in the speaker’s ability to transmit information to the audience. Lucia Hartigan and colleagues describe what they have learnt about delivering an effective scientific oral presentation from their own experiences, and their mistakes

The objective of an oral presentation is to portray large amounts of often complex information in a clear, bite sized fashion. Although some of the success lies in the content, the rest lies in the speaker’s skills in transmitting the information to the audience. 1

Preparation

It is important to be as well prepared as possible. Look at the venue in person, and find out the time allowed for your presentation and for questions, and the size of the audience and their backgrounds, which will allow the presentation to be pitched at the appropriate level.

See what the ambience and temperature are like and check that the format of your presentation is compatible with the available computer. This is particularly important when embedding videos. Before you begin, look at the video on stand-by and make sure the lights are dimmed and the speakers are functioning.

For visual aids, Microsoft PowerPoint or Apple Mac Keynote programmes are usual, although Prezi is increasing in popularity. Save the presentation on a USB stick, with email or cloud storage backup to avoid last minute disasters.

When preparing the presentation, start with an opening slide containing the title of the study, your name, and the date. Begin by addressing and thanking the audience and the organisation that has invited you to speak. Typically, the format includes background, study aims, methodology, results, strengths and weaknesses of the study, and conclusions.

If the study takes a lecturing format, consider including “any questions?” on a slide before you conclude, which will allow the audience to remember the take home messages. Ideally, the audience should remember three of the main points from the presentation. 2

Have a maximum of four short points per slide. If you can display something as a diagram, video, or a graph, use this instead of text and talk around it.

Animation is available in both Microsoft PowerPoint and the Apple Mac Keynote programme, and its use in presentations has been demonstrated to assist in the retention and recall of facts. 3 Do not overuse it, though, as it could make you appear unprofessional. If you show a video or diagram don’t just sit back—use a laser pointer to explain what is happening.

Rehearse your presentation in front of at least one person. Request feedback and amend accordingly. If possible, practise in the venue itself so things will not be unfamiliar on the day. If you appear comfortable, the audience will feel comfortable. Ask colleagues and seniors what questions they would ask and prepare responses to these questions.

It is important to dress appropriately, stand up straight, and project your voice towards the back of the room. Practise using a microphone, or any other presentation aids, in advance. If you don’t have your own presenting style, think of the style of inspirational scientific speakers you have seen and imitate it.

Try to present slides at the rate of around one slide a minute. If you talk too much, you will lose your audience’s attention. The slides or videos should be an adjunct to your presentation, so do not hide behind them, and be proud of the work you are presenting. You should avoid reading the wording on the slides, but instead talk around the content on them.

Maintain eye contact with the audience and remember to smile and pause after each comment, giving your nerves time to settle. Speak slowly and concisely, highlighting key points.

Do not assume that the audience is completely familiar with the topic you are passionate about, but don’t patronise them either. Use every presentation as an opportunity to teach, even your seniors. The information you are presenting may be new to them, but it is always important to know your audience’s background. You can then ensure you do not patronise world experts.

To maintain the audience’s attention, vary the tone and inflection of your voice. If appropriate, use humour, though you should run any comments or jokes past others beforehand and make sure they are culturally appropriate. Check every now and again that the audience is following and offer them the opportunity to ask questions.

Finishing up is the most important part, as this is when you send your take home message with the audience. Slow down, even though time is important at this stage. Conclude with the three key points from the study and leave the slide up for a further few seconds. Do not ramble on. Give the audience a chance to digest the presentation. Conclude by acknowledging those who assisted you in the study, and thank the audience and organisation. If you are presenting in North America, it is usual practice to conclude with an image of the team. If you wish to show references, insert a text box on the appropriate slide with the primary author, year, and paper, although this is not always required.

Answering questions can often feel like the most daunting part, but don’t look upon this as negative. Assume that the audience has listened and is interested in your research. Listen carefully, and if you are unsure about what someone is saying, ask for the question to be rephrased. Thank the audience member for asking the question and keep responses brief and concise. If you are unsure of the answer you can say that the questioner has raised an interesting point that you will have to investigate further. Have someone in the audience who will write down the questions for you, and remember that this is effectively free peer review.

Be proud of your achievements and try to do justice to the work that you and the rest of your group have done. You deserve to be up on that stage, so show off what you have achieved.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.

- ↵ Rovira A, Auger C, Naidich TP. How to prepare an oral presentation and a conference. Radiologica 2013 ; 55 (suppl 1): 2 -7S. OpenUrl

- ↵ Bourne PE. Ten simple rules for making good oral presentations. PLos Comput Biol 2007 ; 3 : e77 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Naqvi SH, Mobasher F, Afzal MA, Umair M, Kohli AN, Bukhari MH. Effectiveness of teaching methods in a medical institute: perceptions of medical students to teaching aids. J Pak Med Assoc 2013 ; 63 : 859 -64. OpenUrl

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Lippincott Open Access

How to deliver an oral presentation

Georgina wellstead.

a Lister Hospital, East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust

Katharine Whitehurst

b Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital

Buket Gundogan

c University College London

d Guy's St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Delivering an oral presentation in conferences and meetings can seem daunting. However, if delivered effectively, it can be an invaluable opportunity to showcase your work in front of peers as well as receive feedback on your project. In this “How to” article, we demonstrate how one can plan and successfully deliver an engaging oral presentation.

Giving an oral presentation at a scientific conference is an almost inevitable task at some point during your medical career. The prospect of presenting your original work to colleagues and peers, however, may be intimidating, and it can be difficult to know how to approach it. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that although daunting, an oral presentation is one of the best ways to get your work out there, and so should be looked upon as an exciting and invaluable opportunity.

Slide content

Although things may vary slightly depending on the type of research you are presenting, the typical structure is as follows:

- Opening slide (title of study, authors, institutions, and date)

- Methodology

- Discussion (including strengths and weaknesses of the study)

Conclusions

Picking out only the most important findings to include in your presentation is key and will keep it concise and easy to follow. This in turn will keep your viewers engaged, and more likely to understand and remember your presentation.

Psychological analysis of PowerPoint presentations, finds that 8 psychological principles are often violated 1 . One of these was the limited capacity of working memory, which can hold 4 units of information at any 1 time in most circumstances. Hence, too many points or concepts on a slide could be detrimental to the presenter’s desire to give information.

You can also help keep your audience engaged with images, which you can talk around, rather than lots of text. Video can also be useful, for example, a surgical procedure. However, be warned that IT can let you down when you need it most and you need to have a backup plan if the video fails. It’s worth coming to the venue early and testing it and resolving issues beforehand with the AV support staff if speaking at a conference.

Slide design and layout

It is important not to clutter your slides with too much text or too many pictures. An easy way to do this is by using the 5×5 rule. This means using no more than 5 bullet points per slide, with no more than 5 words per bullet point. It is also good to break up the text-heavy slides with ones including diagrams or graphs. This can also help to convey your results in a more visual and easy-to-understand way.

It is best to keep the slide design simple, as busy backgrounds and loud color schemes are distracting. Ensure that you use a uniform font and stick to the same color scheme throughout. As a general rule, a light-colored background with dark-colored text is easier to read than light-colored text on a dark-colored background. If you can use an image instead of text, this is even better.

A systematic review study of expert opinion papers demonstrates several key recommendations on how to effectively deliver medical research presentations 2 . These include:

- Keeping your slides simple

- Knowing your audience (pitching to the right level)

- Making eye contact

- Rehearsing the presentation

- Do not read from the slides

- Limiting the number of lines per slide

- Sticking to the allotted time

You should practice your presentation before the conference, making sure that you stick to the allocated time given to you. Oral presentations are usually short (around 8–10 min maximum), and it is, therefore, easy to go under or over time if you have not rehearsed. Aiming to spend around 1 minute per slide is usually a good guide. It is useful to present to your colleagues and seniors, allowing them to ask you questions afterwards so that you can be prepared for the sort of questions you may get asked at the conference. Knowing your research inside out and reading around the subject is advisable, as there may be experts watching you at the conference with more challenging questions! Make sure you re-read your paper the day before, or on the day of the conference to refresh your memory.

It is useful to bring along handouts of your presentation for those who may be interested. Rather than printing out miniature versions of your power point slides, it is better to condense your findings into a brief word document. Not only will this be easier to read, but you will also save a lot of paper by doing this!

Delivering the presentation

Having rehearsed your presentation beforehand, the most important thing to do when you get to the conference is to keep calm and be confident. Remember that you know your own research better than anyone else in the room! Be sure to take some deep breaths and speak at an appropriate pace and volume, making good eye contact with your viewers. If there is a microphone, don’t keep turning away from it as the audience will get frustrated if your voice keeps cutting in and out. Gesturing and using pointers when appropriate can be a really useful tool, and will enable you to emphasize your important findings.

Presenting tips

- Do not hide behind the computer. Come out to the center or side and present there.

- Maintain eye contact with the audience, especially the judges.

- Remember to pause every so often.

- Don’t clutter your presentation with verbal noise such as “umm,” “like,” or “so.” You will look more slick if you avoid this.

- Rhetorical questions once in a while can be useful in maintaining the audience’s attention.

When reaching the end of your presentation, you should slow down in order to clearly convey your key points. Using phases such as “in summary” and “to conclude” often prompts those who have drifted off slightly during your presentation start paying attention again, so it is a critical time to make sure that your work is understood and remembered. Leaving up your conclusions/summary slide for a short while after stopping speaking will give the audience time to digest the information. Conclude by acknowledging any fellow authors or assistants before thanking the audience for their attention and inviting any questions (as long as you have left sufficient time).

If asked a question, firstly thank the audience member, then repeat what they have asked to the rest of the listeners in case they didn’t hear the first time. Keep your answers short and succinct, and if unsure say that the questioner has raised a good point and that you will have to look into it further. Having someone else in the audience write down the question is useful for this.

The key points to remember when preparing for an oral presentation are:

- Keep your slides simple and concise using the 5×5 rule and images.

- When appropriate; rehearse timings; prepare answers to questions; speak slowly and use gestures/ pointers where appropriate; make eye contact with the audience; emphasize your key points at the end; make acknowledgments and thank the audience; invite questions and be confident but not arrogant.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no financial conflict of interest with regard to the content of this report.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 8 June 2017

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

In the social and behavioral sciences, an oral presentation assignment involves an individual student or group of students verbally addressing an audience on a specific research-based topic, often utilizing slides to help audience members understand and retain what they both see and hear. The purpose is to inform, report, and explain the significance of research findings, and your critical analysis of those findings, within a specific period of time, often in the form of a reasoned and persuasive argument. Oral presentations are assigned to assess a student’s ability to organize and communicate relevant information effectively to a particular audience. Giving an oral presentation is considered an important learning skill because the ability to speak persuasively in front of an audience is transferable to most professional workplace settings.

Oral Presentations. Learning Co-Op. University of Wollongong, Australia; Oral Presentations. Undergraduate Research Office, Michigan State University; Oral Presentations. Presentations Research Guide, East Carolina University Libraries; Tsang, Art. “Enhancing Learners’ Awareness of Oral Presentation (Delivery) Skills in the Context of Self-regulated Learning.” Active Learning in Higher Education 21 (2020): 39-50.

Preparing for Your Oral Presentation

In some classes, writing the research paper is only part of what is required in reporting the results your work. Your professor may also require you to give an oral presentation about your study. Here are some things to think about before you are scheduled to give a presentation.

1. What should I say?

If your professor hasn't explicitly stated what the content of your presentation should focus on, think about what you want to achieve and what you consider to be the most important things that members of the audience should know about your research. Think about the following: Do I want to inform my audience, inspire them to think about my research, or convince them of a particular point of view? These questions will help frame how to approach your presentation topic.

2. Oral communication is different from written communication

Your audience has just one chance to hear your talk; they can't "re-read" your words if they get confused. Focus on being clear, particularly if the audience can't ask questions during the talk. There are two well-known ways to communicate your points effectively, often applied in combination. The first is the K.I.S.S. method [Keep It Simple Stupid]. Focus your presentation on getting two to three key points across. The second approach is to repeat key insights: tell them what you're going to tell them [forecast], tell them [explain], and then tell them what you just told them [summarize].

3. Think about your audience

Yes, you want to demonstrate to your professor that you have conducted a good study. But professors often ask students to give an oral presentation to practice the art of communicating and to learn to speak clearly and audibly about yourself and your research. Questions to think about include: What background knowledge do they have about my topic? Does the audience have any particular interests? How am I going to involve them in my presentation?

4. Create effective notes

If you don't have notes to refer to as you speak, you run the risk of forgetting something important. Also, having no notes increases the chance you'll lose your train of thought and begin relying on reading from the presentation slides. Think about the best ways to create notes that can be easily referred to as you speak. This is important! Nothing is more distracting to an audience than the speaker fumbling around with notes as they try to speak. It gives the impression of being disorganized and unprepared.

NOTE: A good strategy is to have a page of notes for each slide so that the act of referring to a new page helps remind you to move to the next slide. This also creates a natural pause that allows your audience to contemplate what you just presented.

Strategies for creating effective notes for yourself include the following:

- Choose a large, readable font [at least 18 point in Ariel ]; avoid using fancy text fonts or cursive text.

- Use bold text, underlining, or different-colored text to highlight elements of your speech that you want to emphasize. Don't over do it, though. Only highlight the most important elements of your presentation.

- Leave adequate space on your notes to jot down additional thoughts or observations before and during your presentation. This is also helpful when writing down your thoughts in response to a question or to remember a multi-part question [remember to have a pen with you when you give your presentation].

- Place a cue in the text of your notes to indicate when to move to the next slide, to click on a link, or to take some other action, such as, linking to a video. If appropriate, include a cue in your notes if there is a point during your presentation when you want the audience to refer to a handout.

- Spell out challenging words phonetically and practice saying them ahead of time. This is particularly important for accurately pronouncing people’s names, technical or scientific terminology, words in a foreign language, or any unfamiliar words.

Creating and Using Overheads. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kelly, Christine. Mastering the Art of Presenting. Inside Higher Education Career Advice; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th edition. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations. Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Organizing the Content

In the process of organizing the content of your presentation, begin by thinking about what you want to achieve and how are you going to involve your audience in the presentation.

- Brainstorm your topic and write a rough outline. Don’t get carried away—remember you have a limited amount of time for your presentation.

- Organize your material and draft what you want to say [see below].

- Summarize your draft into key points to write on your presentation slides and/or note cards and/or handout.

- Prepare your visual aids.

- Rehearse your presentation and practice getting the presentation completed within the time limit given by your professor. Ask a friend to listen and time you.

GENERAL OUTLINE

I. Introduction [may be written last]

- Capture your listeners’ attention . Begin with a question, an amusing story, a provocative statement, a personal story, or anything that will engage your audience and make them think. For example, "As a first-gen student, my hardest adjustment to college was the amount of papers I had to write...."

- State your purpose . For example, "I’m going to talk about..."; "This morning I want to explain…."

- Present an outline of your talk . For example, “I will concentrate on the following points: First of all…Then…This will lead to…And finally…"

II. The Body

- Present your main points one by one in a logical order .

- Pause at the end of each point . Give people time to take notes, or time to think about what you are saying.

- Make it clear when you move to another point . For example, “The next point is that...”; “Of course, we must not forget that...”; “However, it's important to realize that....”

- Use clear examples to illustrate your points and/or key findings .

- If appropriate, consider using visual aids to make your presentation more interesting [e.g., a map, chart, picture, link to a video, etc.].

III. The Conclusion

- Leave your audience with a clear summary of everything that you have covered.

- Summarize the main points again . For example, use phrases like: "So, in conclusion..."; "To recap the main issues...," "In summary, it is important to realize...."

- Restate the purpose of your talk, and say that you have achieved your aim : "My intention was ..., and it should now be clear that...."

- Don't let the talk just fizzle out . Make it obvious that you have reached the end of the presentation.

- Thank the audience, and invite questions : "Thank you. Are there any questions?"

NOTE: When asking your audience if anyone has any questions, give people time to contemplate what you have said and to formulate a question. It may seem like an awkward pause to wait ten seconds or so for someone to raise their hand, but it's frustrating to have a question come to mind but be cutoff because the presenter rushed to end the talk.

ANOTHER NOTE: If your last slide includes any contact information or other important information, leave it up long enough to ensure audience members have time to write the information down. Nothing is more frustrating to an audience member than wanting to jot something down, but the presenter closes the slides immediately after finishing.

Creating and Using Overheads. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations. Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Delivering Your Presentation

When delivering your presentation, keep in mind the following points to help you remain focused and ensure that everything goes as planned.

Pay Attention to Language!

- Keep it simple . The aim is to communicate, not to show off your vocabulary. Using complex words or phrases increases the chance of stumbling over a word and losing your train of thought.

- Emphasize the key points . Make sure people realize which are the key points of your study. Repeat them using different phrasing to help the audience remember them.

- Check the pronunciation of difficult, unusual, or foreign words beforehand . Keep it simple, but if you have to use unfamiliar words, write them out phonetically in your notes and practice saying them. This is particularly important when pronouncing proper names. Give the definition of words that are unusual or are being used in a particular context [e.g., "By using the term affective response, I am referring to..."].

Use Your Voice to Communicate Clearly

- Speak loud enough for everyone in the room to hear you . Projecting your voice may feel uncomfortably loud at first, but if people can't hear you, they won't try to listen. However, moderate your voice if you are talking in front of a microphone.

- Speak slowly and clearly . Don’t rush! Speaking fast makes it harder for people to understand you and signals being nervous.

- Avoid the use of "fillers." Linguists refer to utterances such as um, ah, you know, and like as fillers. They occur most often during transitions from one idea to another and, if expressed too much, are distracting to an audience. The better you know your presentation, the better you can control these verbal tics.

- Vary your voice quality . If you always use the same volume and pitch [for example, all loud, or all soft, or in a monotone] during your presentation, your audience will stop listening. Use a higher pitch and volume in your voice when you begin a new point or when emphasizing the transition to a new point.

- Speakers with accents need to slow down [so do most others]. Non-native speakers often speak English faster than we slow-mouthed native speakers, usually because most non-English languages flow more quickly than English. Slowing down helps the audience to comprehend what you are saying.

- Slow down for key points . These are also moments in your presentation to consider using body language, such as hand gestures or leaving the podium to point to a slide, to help emphasize key points.

- Use pauses . Don't be afraid of short periods of silence. They give you a chance to gather your thoughts, and your audience an opportunity to think about what you've just said.

Also Use Your Body Language to Communicate!

- Stand straight and comfortably . Do not slouch or shuffle about. If you appear bored or uninterested in what your talking about, the audience will emulate this as well. Wear something comfortable. This is not the time to wear an itchy wool sweater or new high heel shoes for the first time.

- Hold your head up . Look around and make eye contact with people in the audience [or at least pretend to]. Do not just look at your professor or your notes the whole time! Looking up at your your audience brings them into the conversation. If you don't include the audience, they won't listen to you.

- When you are talking to your friends, you naturally use your hands, your facial expression, and your body to add to your communication . Do it in your presentation as well. It will make things far more interesting for the audience.

- Don't turn your back on the audience and don't fidget! Neither moving around nor standing still is wrong. Practice either to make yourself comfortable. Even when pointing to a slide, don't turn your back; stand at the side and turn your head towards the audience as you speak.

- Keep your hands out of your pocket . This is a natural habit when speaking. One hand in your pocket gives the impression of being relaxed, but both hands in pockets looks too casual and should be avoided.

Interact with the Audience

- Be aware of how your audience is reacting to your presentation . Are they interested or bored? If they look confused, stop and ask them [e.g., "Is anything I've covered so far unclear?"]. Stop and explain a point again if needed.

- Check after highlighting key points to ask if the audience is still with you . "Does that make sense?"; "Is that clear?" Don't do this often during the presentation but, if the audience looks disengaged, interrupting your talk to ask a quick question can re-focus their attention even if no one answers.

- Do not apologize for anything . If you believe something will be hard to read or understand, don't use it. If you apologize for feeling awkward and nervous, you'll only succeed in drawing attention to the fact you are feeling awkward and nervous and your audience will begin looking for this, rather than focusing on what you are saying.

- Be open to questions . If someone asks a question in the middle of your talk, answer it. If it disrupts your train of thought momentarily, that's ok because your audience will understand. Questions show that the audience is listening with interest and, therefore, should not be regarded as an attack on you, but as a collaborative search for deeper understanding. However, don't engage in an extended conversation with an audience member or the rest of the audience will begin to feel left out. If an audience member persists, kindly tell them that the issue can be addressed after you've completed the rest of your presentation and note to them that their issue may be addressed later in your presentation [it may not be, but at least saying so allows you to move on].

- Be ready to get the discussion going after your presentation . Professors often want a brief discussion to take place after a presentation. Just in case nobody has anything to say or no one asks any questions, be prepared to ask your audience some provocative questions or bring up key issues for discussion.

Amirian, Seyed Mohammad Reza and Elaheh Tavakoli. “Academic Oral Presentation Self-Efficacy: A Cross-Sectional Interdisciplinary Comparative Study.” Higher Education Research and Development 35 (December 2016): 1095-1110; Balistreri, William F. “Giving an Effective Presentation.” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 35 (July 2002): 1-4; Creating and Using Overheads. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Enfield, N. J. How We Talk: The Inner Workings of Conversation . New York: Basic Books, 2017; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations. Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Speaking Tip

Your First Words are Your Most Important Words!

Your introduction should begin with something that grabs the attention of your audience, such as, an interesting statistic, a brief narrative or story, or a bold assertion, and then clearly tell the audience in a well-crafted sentence what you plan to accomplish in your presentation. Your introductory statement should be constructed so as to invite the audience to pay close attention to your message and to give the audience a clear sense of the direction in which you are about to take them.

Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th edition. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015.

Another Speaking Tip

Talk to Your Audience, Don't Read to Them!

A presentation is not the same as reading a prepared speech or essay. If you read your presentation as if it were an essay, your audience will probably understand very little about what you say and will lose their concentration quickly. Use notes, cue cards, or presentation slides as prompts that highlight key points, and speak to your audience . Include everyone by looking at them and maintaining regular eye-contact [but don't stare or glare at people]. Limit reading text to quotes or to specific points you want to emphasize.

- << Previous: Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Next: Group Presentations >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

- Presenting the Research Paper

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Writing the Research Paper

Writing an Abstract

Oral presentation, compiling a powerpoint.

Abstract : a short statement that describes a longer work.

- Indicate the subject.

- Describe the purpose of the investigation.

- Briefly discuss the method used.

- Make a statement about the result.

Oral presentations usually introduce a discussion of a topic or research paper. A good oral presentation is focused, concise, and interesting in order to trigger a discussion.

- Be well prepared; write a detailed outline.

- Introduce the subject.

- Talk about the sources and the method.

- Indicate if there are conflicting views about the subject (conflicting views trigger discussion).

- Make a statement about your new results (if this is your research paper).

- Use visual aids or handouts if appropriate.

An effective PowerPoint presentation is just an aid to the presentation, not the presentation itself .

- Be brief and concise.

- Focus on the subject.

- Attract attention; indicate interesting details.

- If possible, use relevant visual illustrations (pictures, maps, charts graphs, etc.).

- Use bullet points or numbers to structure the text.

- Make clear statements about the essence/results of the topic/research.

- Don't write down the whole outline of your paper and nothing else.

- Don't write long full sentences on the slides.

- Don't use distracting colors, patterns, pictures, decorations on the slides.

- Don't use too complicated charts, graphs; only those that are relatively easy to understand.

- << Previous: Writing the Research Paper

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

How to Prepare and Give a Scholarly Oral Presentation

- First Online: 01 January 2020

Cite this chapter

- Cheryl Gore-Felton 2

1213 Accesses

Building an academic reputation is one of the most important functions of an academic faculty member, and one of the best ways to build a reputation is by giving scholarly presentations, particularly those that are oral presentations. Earning the reputation of someone who can give an excellent talk often results in invitations to give keynote addresses at regional and national conferences, which increases a faculty member’s visibility along with their area of research. Given the importance of oral presentations, it is surprising that few graduate or medical programs provide courses on how to give a talk. This is unfortunate because there are skills that can be learned and strategies that can be used to improve the ability to give an interesting, well-received oral presentation. To that end, the aim of this chapter is to provide faculty with best practices and tips on preparing and giving an academic oral presentation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Pashler H, McDaniel M, Rohrer D, Bjork R. Learning styles: concepts and evidence. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2009;9:105–19.

Article Google Scholar

Newsam JM. Out in front: making your mark with a scientific presentation. USA: First Printing; 2019.

Google Scholar

Ericsson AK, Krampe RT, Tesch-Romer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:363–406.

Seaward BL. Managing stress: principles and strategies for health and well-being. 7th ed. Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC: Burlington; 2012.

Krantz WB. Presenting an effective and dynamic technical paper: a guidebook for novice and experienced speakers in a multicultural world. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

Cheryl Gore-Felton

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cheryl Gore-Felton .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Laura Weiss Roberts

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Gore-Felton, C. (2020). How to Prepare and Give a Scholarly Oral Presentation. In: Roberts, L. (eds) Roberts Academic Medicine Handbook. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31957-1_42

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31957-1_42

Published : 01 January 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-31956-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-31957-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Organizing Academic Research Papers: Giving an Oral Presentation

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

Preparing for Your Oral Presentation

In some classes, writing the research paper is only part of what is required. Your professor may also require you to give an oral presentation about your study. Here are some things to think about before you are scheduled to give your presentation.

- What should I say? If your professor hasn't explicitly stated what your presentation should focus on, think about what you want to achieve and what you consider to be the most important things that others should know about your study. Think about: do I want to inform my audience, inspire them to think about my research, or convince them of a particular point of view?

- Oral communication is different from written communication. Your audience only has one chance to hear your talk and can't "re-read" it if they get confused. Focus on being clear, particularly if the audience can't ask questions during the talk. There are two well-known ways to communicate your points effectively. The first is to K.I.S.S. (keep it simple stupid). Focus on getting one to three key points across. Second, repeat key insights: tell them what you're going to tell them (Forecast), tell them, and then tell them what you just told them (Summarize).

- Think about your audience. Yes, you want to demonstrate to your professor that you have conducted a good study. But professors often ask students to give an oral presentation to practice the art of communicating and to learn to speak clearly and audibly about yourself and your research. Questions to think about include, what background knowledge do they have about my topic? Does the audience have any particular interests? How am I going to involve them in my presentation?

Creating and Using Overheads . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking. 10th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2008; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations . Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations . The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills . Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Organizing the Content

First of all, think about what you want to achieve and think about how are you going to involve your audience in the presentation.

- Brainstorm your topic and write a rough outline. Don’t get carried away—remember you have a limited amount of time for your presentation.

- Organize your material and draft what you want to say [see below]

- Summarize your draft into key points to write on overheads and/or note cards.

- Prepare your visual aids.

- Rehearse your presentation and get its length right. Ask a friend to listen and time you.

GENERAL OUTLINE

I. Introduction (may be written last)

- Capture your listeners’ attention . Begin with a question, an amusing story, a startling comment, or anything that will make the audience think.

- State your purpose . For example, "I’m going to talk about..."; "This morning I want to explain…."

- Present an outline of your talk . For example, “I will concentrate on the following points: First of all…Then…This will lead to…And finally…"

II. The Body

- Present your main points one by one in logical order .

- Pause at the end of each point . Give people time to take notes, or time to think about what you are saying.

- Make it clear when you move to another point . For example, “The next point is that...”; “Of course, we must not forget that...”; “However, it's important to realize that....”

- Use clear examples to illustrate your points and/or key findings .

- Consider using visual aids to make your presentation more interesting [e.g., a map, chart, picture, etc.].

III. The Conclusion

- Leave your audience with a clear summary of everything that you have covered.

- Don't let the talk just fizzle out . Make it obvious that you have reached the end of the presentation.

- Summarize the main points again . For example, use phrases like: "So, in conclusion..."; "To recap the main points..."

- Restate the purpose of your talk, and say that you have achieved your aim : "My intention was ..., and it should now be clear that...."

- Thank the audience, and invite questions : "Thank you. Are there any questions?"

Creating and Using Overheads . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking. 10th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2008; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations . Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations . The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Delivering Your Presentation

Pay attention to language!

- Keep it simple . The aim is to communicate, not to show off your vocabulary.

- Emphasize the key points . Make sure people realize which are the key points. Repeat them using different phrasing.

- Check the pronunciation of difficult, unusual, or foreign words beforehand . Write out difficult words phonetically in your notes.

Use your voice to communicate clearly

- Speak loudly enough for everyone in the room to hear you . This may feel uncomfortably loud at first, but if people can't hear you, they won't try to listen.

- Speak slowly and clearly . Don’t rush! Speaking fast doesn’t make you seem smarter, it will only make it harder for other people to understand you.

- Practice to avoid saying um, ah, you know, like. These words occur most at transitions from one idea to another and are distracting to an audience. The better you know your presentation, the better you can control these verbal tics.

- Vary your voice quality . If you always use the same volume and pitch [for example, all loud, or all soft, or in a monotone] your audience will stop listening.

- Speakers with accents need to slow down [so do most others]. Non-native speakers often speak English faster than we slow-mouthed native speakers, usually because most non-English languages flow more quickly than English. Slowing down helps the audience to comprehend your talk.

- When you begin a new point, use a higher pitch and volume .

- Slow down for key points . These are also moments in your presentation to consider using body language such as hand gestures to help emphasize key points.

- Use pauses . Don't be afraid of short periods of silence. They give you a chance to gather your thoughts, and your audience a chance to think.

Use your body language to communicate too!

- Stand straight and comfortably . Do not slouch or shuffle about. If you appear bored or uninterested in what your talking about, the audience will be as well.

- Hold your head up . Look around and make eye contact with people in the audience. Do not just address your professor! Do not stare at a point on the carpet or the wall. If you don't include the audience, they won't listen to you.

- When you are talking to your friends, you naturally use your hands, your facial expression, and your body to add to your communication . Do it in your presentation as well. It will make things far more interesting for the audience.

- Don't turn your back on the audience and don't fidget! Neither moving around nor standing still is wrong. Practice either to make yourself comfortable.

- Keep your hands out of your pocket . This is a natural habit when speaking. One hand in your pocket gives the impression of being relaxed, but both hands in pockets looks too casual and should be avoided.

Interact with the audience

- Be aware of how your audience is reacting to your presentation . Are they interested or bored? If they look confused, ask them. Stop and explain a point again.

- Check if the audience is still with you . "Does that make sense?"; "Is that clear?"

- Do not apologize for anything . If you believe something will be hard to read or understand, don't use it. If you apologize for feeling awkward or nervous, you'll only succeed in drawing attention to it and your audience will begin looking for it.

- Be open to questions . If someone raises a hand, or asks a question in the middle of your talk, answer it. If it disrupts your train of thought momentarily, that's ok because your audience will understand. Questions show that the audience is listening with interest and, therefore, should not be regarded as an attack on you, but as a collaborative search for deeper understanding. However, don't engage in a conversation with an audience member or the rest of the audience will begin to feel left out. If an audience member persists, kindly tell them that the issue can be addressed after you've completed the rest of your presentation and note to them that their issue may be addressed by things you say in the rest of your presentation [it may not but at least you can move on].

- Be ready to get the discussion going after your presentation . Professors often want a brief discussion to take place after a presentation. Just in case nobody has anything to say, be prepared with some provocative questions to ask or points for discussion for your audience.

Speaking Tip

Your First Words are Your Most Important!

Your introduction should begin with something that grabs the attention of your audience, such as, an interesting statisitic, a brief narrative or story, or a bold assertion, and then clearly tell the audience in a well-crafted sentence what you plan to accomplish in your presentation. Your introductory statement should be constructed so as to invite the audience to pay close attention to your message and to give the audience a clear sense of the direction in which you are about to take them.

Another Speaking Tip

Talk to Your Audience, Don't Read to Them!

A presentation is not the same as an essay. If you read your presentation as if it were an essay, your audience will probably understand very little about you say and will lose concentration quickly. Use notes, cue cards, or overheads as prompts that emphasis key points, and speak to the audience. Include everyone by looking at them and maintaining regular eye-contact (but don't stare or glare at people).

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Dealing with Nervousness >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023 11:58 AM

- URL: https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803

- QuickSearch

- Library Catalog

- Databases A-Z

- Publication Finder

- Course Reserves

- Citation Linker

- Digital Commons

- Our Website

Research Support

- Ask a Librarian

- Appointments

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Research Guides

- Databases by Subject

- Citation Help

Using the Library

- Reserve a Group Study Room

- Renew Books

- Honors Study Rooms

- Off-Campus Access

- Library Policies

- Library Technology

User Information

- Grad Students

- Online Students

- COVID-19 Updates

- Staff Directory

- News & Announcements

- Library Newsletter

My Accounts

- Interlibrary Loan

- Staff Site Login

FIND US ON

This page has been archived and is no longer updated

Oral Presentation Structure

Finally, presentations normally include interaction in the form of questions and answers. This is a great opportunity to provide whatever additional information the audience desires. For fear of omitting something important, most speakers try to say too much in their presentations. A better approach is to be selective in the presentation itself and to allow enough time for questions and answers and, of course, to prepare well by anticipating the questions the audience might have.

As a consequence, and even more strongly than papers, presentations can usefully break the chronology typically used for reporting research. Instead of presenting everything that was done in the order in which it was done, a presentation should focus on getting a main message across in theorem-proof fashion — that is, by stating this message early and then presenting evidence to support it. Identifying this main message early in the preparation process is the key to being selective in your presentation. For example, when reporting on materials and methods, include only those details you think will help convince the audience of your main message — usually little, and sometimes nothing at all.

The opening

- The context as such is best replaced by an attention getter , which is a way to both get everyone's attention fast and link the topic with what the audience already knows (this link provides a more audience-specific form of context).

- The object of the document is here best called the preview because it outlines the body of the presentation. Still, the aim of this element is unchanged — namely, preparing the audience for the structure of the body.

- The opening of a presentation can best state the presentation's main message , just before the preview. The main message is the one sentence you want your audience to remember, if they remember only one. It is your main conclusion, perhaps stated in slightly less technical detail than at the end of your presentation.

In other words, include the following five items in your opening: attention getter , need , task , main message , and preview .

Even if you think of your presentation's body as a tree, you will still deliver the body as a sequence in time — unavoidably, one of your main points will come first, one will come second, and so on. Organize your main points and subpoints into a logical sequence, and reveal this sequence and its logic to your audience with transitions between points and between subpoints. As a rule, place your strongest arguments first and last, and place any weaker arguments between these stronger ones.

The closing

After supporting your main message with evidence in the body, wrap up your oral presentation in three steps: a review , a conclusion , and a close . First, review the main points in your body to help the audience remember them and to prepare the audience for your conclusion. Next, conclude by restating your main message (in more detail now that the audience has heard the body) and complementing it with any other interpretations of your findings. Finally, close the presentation by indicating elegantly and unambiguously to your audience that these are your last words.

Starting and ending forcefully

Revealing your presentation's structure.

To be able to give their full attention to content, audience members need structure — in other words, they need a map of some sort (a table of contents, an object of the document, a preview), and they need to know at any time where they are on that map. A written document includes many visual clues to its structure: section headings, blank lines or indentations indicating paragraphs, and so on. In contrast, an oral presentation has few visual clues. Therefore, even when it is well structured, attendees may easily get lost because they do not see this structure. As a speaker, make sure you reveal your presentation's structure to the audience, with a preview , transitions , and a review .

The preview provides the audience with a map. As in a paper, it usefully comes at the end of the opening (not too early, that is) and outlines the body, not the entire presentation. In other words, it needs to include neither the introduction (which has already been delivered) nor the conclusion (which is obvious). In a presentation with slides, it can usefully show the structure of the body on screen. A slide alone is not enough, however: You must also verbally explain the logic of the body. In addition, the preview should be limited to the main points of the presentation; subpoints can be previewed, if needed, at the beginning of each main point.

Transitions are crucial elements for revealing a presentation's structure, yet they are often underestimated. As a speaker, you obviously know when you are moving from one main point of a presentation to another — but for attendees, these shifts are never obvious. Often, attendees are so involved with a presentation's content that they have no mental attention left to guess at its structure. Tell them where you are in the course of a presentation, while linking the points. One way to do so is to wrap up one point then announce the next by creating a need for it: "So, this is the microstructure we observe consistently in the absence of annealing. But how does it change if we anneal the sample at 450°C for an hour or more? That's my next point. Here is . . . "

Similarly, a review of the body plays an important double role. First, while a good body helps attendees understand the evidence, a review helps them remember it. Second, by recapitulating all the evidence, the review effectively prepares attendees for the conclusion. Accordingly, make time for a review: Resist the temptation to try to say too much, so that you are forced to rush — and to sacrifice the review — at the end.

Ideally, your preview, transitions, and review are well integrated into the presentation. As a counterexample, a preview that says, "First, I am going to talk about . . . , then I will say a few words about . . . and finally . . . " is self-centered and mechanical: It does not tell a story. Instead, include your audience (perhaps with a collective we ) and show the logic of your structure in view of your main message.

This page appears in the following eBook

Topic rooms within Scientific Communication

Within this Subject (22)

- Communicating as a Scientist (3)

- Papers (4)

- Correspondence (5)

- Presentations (4)

- Conferences (3)

- Classrooms (3)

Other Topic Rooms

- Gene Inheritance and Transmission

- Gene Expression and Regulation

- Nucleic Acid Structure and Function

- Chromosomes and Cytogenetics

- Evolutionary Genetics

- Population and Quantitative Genetics

- Genes and Disease

- Genetics and Society

- Cell Origins and Metabolism

- Proteins and Gene Expression

- Subcellular Compartments

- Cell Communication

- Cell Cycle and Cell Division

© 2014 Nature Education

- Press Room |

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Notice |

Visual Browse

Reference management. Clean and simple.

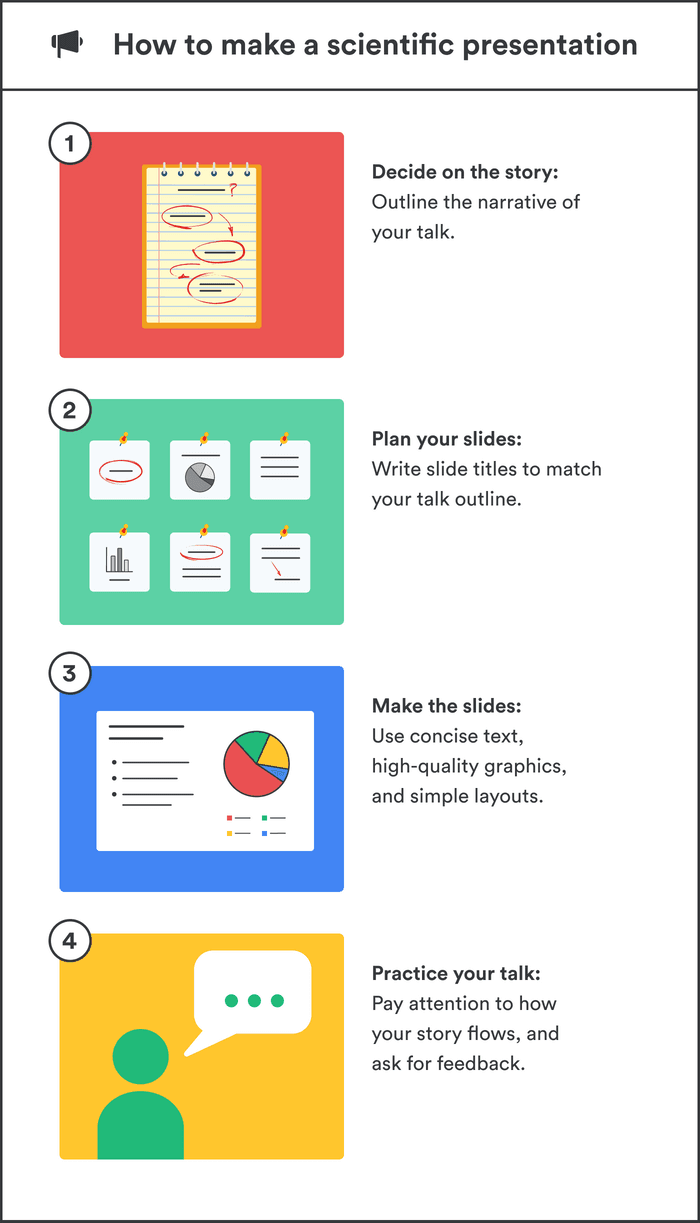

How to make a scientific presentation

Scientific presentation outlines

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk, 1. how much time do you have, 2. who will you speak to, 3. what do you want the audience to learn from your talk, step 1: outline your presentation, step 2: plan your presentation slides, step 3: make the presentation slides, slide design, text elements, animations and transitions, step 4: practice your presentation, final thoughts, frequently asked questions about preparing scientific presentations, related articles.

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered;

- How to outline a scientific presentation;

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation.

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

There are two main types of scientific talks: