Want to Get your Dissertation Accepted?

Discover how we've helped doctoral students complete their dissertations and advance their academic careers!

Join 200+ Graduated Students

Get Your Dissertation Accepted On Your Next Submission

Get customized coaching for:.

- Crafting your proposal,

- Collecting and analyzing your data, or

- Preparing your defense.

Trapped in dissertation revisions?

Phd qualifying exam: 5 steps to success, published by steve tippins on may 27, 2022 may 27, 2022.

Last Updated on: 2nd February 2024, 05:02 am

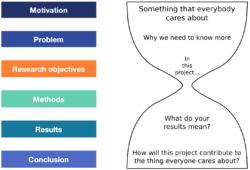

The PhD qualifying exam varies by institution and discipline, but they all share something in common: they are among the most difficult tests you will ever take. A PhD qualifying exam is given after you completed your coursework. It is the final hurdle before you begin to work on your dissertation . Passing the PhD qualifying exam is your ticket out of coursework and into the research phase of your degree.

In this article, we’ll cover what the process looks like and how to prepare for the written and oral parts of the exam. We also include sample questions to give you an idea of the territory.

Traditional vs New Qualifying Exams

There is a distinction between how qualifying exams are traditionally structured and how some institutions are now conducting them. Here’s the lowdown:

Traditional Qualifying Exams

Traditionally, the exam has one or two parts: a written part and sometimes an oral part. The exam is made up of whatever the faculty wants to ask you, so you have to be prepared for just about anything that was covered in your classes.

To prepare, people typically take two to four months to review the literature they covered in the previous few years so that they are prepared to answer questions on any topic. Many times, you might know broad topics where questions can be drawn from but not specific questions. If that is the case, the oral exam would typically be used for clarification, allowing you to further explain a topic and show your understanding to faculty.

New Qualifying Exams

Some schools have moved to a model in which you receive the questions and have two weeks or so to answer them. Then, you have time to prepare lots of material for your answers. However, faculty might expect more perfection in this case because you get a chance to review and ponder, as opposed to the traditional exam.

Other schools may just want to see your dissertation proposal, which takes the place of your exam. Either way, you have to show that you have grasped the material from your first several years of coursework.

How Long Is the PhD Qualifying Exam?

If you are writing the traditional model, you will have five to seven questions over two days, and you basically write everything you can think of on those questions . Students typically dump everything they know, whether it applies or not, just to show how much they know.

If you’re taking the exam at home, you will probably type it. Many schools now allow typing in the traditional model as well. Your answers will usually run in the neighborhood of 15 to 20 pages per question because they want to see everything you can come up with.

How Do You Prepare for the PhD Qualifying Exam?

Many students waste valuable study time because they don’t know how to structure their preparation to be most effective. Here’s how to best prepare for the PhD qualifying exam.

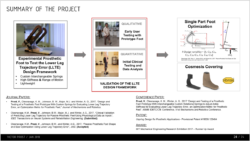

Step 1: Assemble the Literature

To prepare for the qualifying exam, the first step is to assemble the literature you want to review . Look at each class you took and gather the academic articles you read in those classes.

Step 2: Review and Take Notes

The next step is to read the articles again and take notes on them, including the key findings and methodology. This step might take you a couple of months to do.

Step 3: Go Back Through the Notes and Summarize

The third step is to go back through the notes you took on all of those articles and summarize them again to condense them even further.

Step 4: Review Your Summaries

The fourth step is to spend four to five days going back through your condensed summary so that you have it all in your mind. That way, you can quickly recall which author said what and how it relates to what other authors have said. Keep all those relationships in your head.

Step 5: Rest

The day before your exam, the fifth step is to rest so that you’re ready for the intense nature of the next couple of days.

PhD Qualifying Exam Pass Rate

The PhD qualifying exam pass rate is difficult to determine because schools don’t usually publish or talk about it. About half the people who enter a PhD program complete it.

Most of the people who don’t complete the program leave before or at the qualifying exam. When people get to the dissertation phase, they’re more likely to finish.

When you take your qualifying exam, many schools have four levels of grades: high pass, pass, low pass, and didn’t pass.

What Happens If You Fail the PhD Qualifying Exam?

If you fail the PhD qualifying exam, most schools will allow you another attempt to pass it. They may only do them a certain number of times a year, so it could be six months to a year later. But you may get another shot at it.

Ultimately, if you fail the PhD qualifying exam, you do not get to move forward to write the dissertation and you are finished with the program. They have determined that you have not learned, gathered, or synthesized enough material and you’re not ready to work on a dissertation.

On the other hand, if you pass the PhD qualifying exam, most schools then say you have reached what has become known as “all but dissertation” or ABD . With everything but the dissertation finished, some people use the term “ PhD candidate ” or PhD(c) to represent themselves.

What Is an Oral Exam?

There are two types of oral exams. One takes place after a written exam, while the other stands alone.

Written Exam Followed by Oral Exam

If you are taking a written exam and an oral exam follows, you can usually provide clarification in the oral exam and dig further into what was on the comprehensive exam.

Oral Exam Only

Some schools just give an oral exam, where you and a number of faculty members meet in person or on a zoom call. They ask you the questions, and you get to answer them without writing.

Tips for Navigating the Oral Exam

- Treat the committee with respect. Remember that you’re walking into a room of people who control your future. If you don’t respect them, they will take it as a sign that you are not serious, which could negatively impact the likelihood of you moving forward.

- Answer every question.

- If you get stuck, ask them to rephrase the question. Doing so will allow your brain a chance to relax.

- Ask the committee questions. When you finish answering a question, you can always ask “Have I answered your question?” or “Have I answered to the level you want me to answer?” Then, ultimately, you can ask them questions, such as, “Do you have any thoughts on that?”

Sample Questions for the PhD Qualifying Exam

It’s vital to know what to expect when you take your exam. Here are some methods for getting familiar with the question you may be asked.

First, a Tip: Look at Past Tests

Some institutions keep old PhD qualifying exams or comprehensive exam questions. You can look at those to see the types of questions they may ask and what they might be looking for.

Other institutions might even let you see the questions that have been asked in the past. They’re not going to ask the exact same questions, but you will at least be able to see which areas have been emphasized or revisited over time. If there’s an area that comes up every year, you definitely want to make sure you’re ready to answer questions related to it. Look at the questions to determine tendencies and identify the types of questions you might be asked.

Some Broad Example Questions

The questions are going to be discipline specific, but here are some broad examples:

- Trace the development of the capital asset pricing model from its first author to the current thoughts.

- Author X proposes that the Roman Empire fell for certain reasons, and Author Y proposes different reasons. What are the current thoughts on that, and how does it apply to the current situation in the United States?

- Trace the antecedents of Greenleaf’s servant leadership. Where has it gone from there? What are authors currently proposing regarding servant leadership?

- Trace the development of generally accepted accounting principles and how they might be applied in a nonprofit situation.

Final Thoughts

The doctoral comprehensive exam is a big deal. Take it seriously, and be prepared to show the faculty that you have grasped what they have offered to you as opportunities to learn. Show that you understand how the material and literature fit together and provide a platform for future learning and research.

Steve Tippins

Steve Tippins, PhD, has thrived in academia for over thirty years. He continues to love teaching in addition to coaching recent PhD graduates as well as students writing their dissertations. Learn more about his dissertation coaching and career coaching services. Book a Free Consultation with Steve Tippins

Related Posts

A Professor’s Top 3 Pieces of Advice for Ph.D. Students

When it comes to getting a Ph.D., there is no one-size-fits-all approach to ensuring success in graduate school. Every student must find their own path to navigating the most rigorous academic experience that most people Read more…

PhD Stipends: All Your Questions Answered

What are PhD stipends? When you enter a PhD program, you can also get financial support in the form of tuition reduction, free tuition, and PhD stipends. That means compensation for work you’ll do, such Read more…

PhD Graduates: A Guide to Life After Your Degree

What do PhD students do after they graduate? What should they do? And what are the unexpected challenges and limitations they encounter? The first thing a PhD graduate should do is rest and gather their Read more…

Make This Your Last Round of Dissertation Revision.

Learn How to Get Your Dissertation Accepted .

Discover the 5-Step Process in this Free Webinar .

Almost there!

Please verify your email address by clicking the link in the email message we just sent to your address.

If you don't see the message within the next five minutes, be sure to check your spam folder :).

Hack Your Dissertation

5-Day Mini Course: How to Finish Faster With Less Stress

Interested in more helpful tips about improving your dissertation experience? Join our 5-day mini course by email!

Email forwarding for @cs.stanford.edu is changing. Updates and details here . CS Commencement Ceremony June 16, 2024. Learn More .

PhD | Qualifying Examination

Main navigation.

The qualifying examination tests a student's depth of knowledge and familiarity in their area of specialization. Qualifying exams are generally offered in all areas covered by the written comprehensive exam. It is possible for a student to request a qualifying exam in an area not already offered, such as one that cuts across current divisions. The feasibility of this request is determined on a case-by-case basis by the PhD program committee. A student should pass a qualifying exam no later than the end of their third year.

A student may take the qualifying exams only twice. In some cases a conditional pass is awarded. When the designated conditions have been met (such as CAing for a certain class, taking a course, or reading additional material in a specific area), the student is credited with the pass. If a student fails the qualifying exam a second time, the PhD program committee is contacted because its an indication that the student is not "making reasonable progress". This is cause for dismissal by default from the PhD program. The qualifying exams are a University requirement and are taken very seriously. Therefore, sufficient time and in-depth preparation must be given to the quals area that the student chooses, to ensure success.

The format of the qualifying exams varies from year-to-year and area-to-area, depending on the faculty member or quals chair in charge of each specific exam. Examples are in-class written exams, "take-home" written exams, oral exams, written assignments and/or a combination of the above. The quals chair administers the exams and the results must be submitted to the PhD program officer, as they will enter the information into the University's Axess (PeopleSoft) and Departmental database systems. Passing the qualifying exam certifies that the student is ready to begin dissertation work in the chosen area. If a student wishes to do dissertation work in an area other than their qualifying exam area, the student's advisor and/or the faculty in the new area will determine whether an additional exam is required.

Information about the Qualifying Examination

The student's advisor needs to email [email protected] (and cc faculty who were on the Quals committee) the qual results.

- The candidate student must form a committee of 3 faculty members. A committee needs to have (at least) 2 core AI faculty on it. Upon request, we can consider having 1 core AI and (at least) 1 AI-affiliated faculty. In all cases, at least 1 core AI faculty must be present.

- The student is asked to prepare a 30-minute presentation on a research project the student is working on.

- The student supplies to each committee member a short report summarizing the student’s research project and a list of references that is related to such a project. Report and list of references are due to the committee members 3 days before the exam.

- During the first half hour the student presents the research project.

- The second half hour comprises a 30min QA session related to the research project by the committee. During such sessions committee members can (but are not necessarily committed to) ask questions related to any of the papers in the list of references. This gives the opportunity to committee members to assess general mastery of the area the student is working on.

- Statistical Machine Learning (Percy Liang)

- Natural Language Processing (Dan Jurafsky)

- The candidate’s advisor/s should be a member/s.

- At least one member must be a Stanford CS faculty.

- Two members must be working in Computational Biology.

- One member will be non-computational from an affected field of biomedicine.

- At least two members must be doing work directly relevant to the candidate’s work.

- 30 minutes presentation on their research.

- 30 minutes presentation on 3 papers which are jointly picked by the quals committee and the student, relating to the student’s current and future research directions.

- After the exam has been taken, the candidate will email the CS PhD Student Services Admin, cc’ing all members of their quals committee, with the exam’s outcome.

- HCI (Michael Bernstein)

- InfoQual (Jure Leskovec)

- The physiqual will now consist of exams with faculty in 5 areas: vision, geometry, math, graphics and robotics .

- The second part of the physiqual (which consists of a talk on a few selected papers) will no longer be part of the physiqual, given that there is requisites for the thesis proposal .

- For students who have already taken the second oral portion of the physiqual, we suggest that their advisors exempt them through the thesis proposal requirement. As the current language of the thesis proposal requirement would seem to allow this.

- Form a panel of 3 professors (CS systems faculty). Select 3-4 papers, in consultation with the panel, in an area not identical to your thesis work for you to read, review and synthesize over a period of 3 weeks. Depending on the panel's advice, you may need to execute a small implementation project. For example, a project might answer a related research question, reproduce or compare results in a novel setting, or quantitatively investigate the implications of certain design decisions.

- The exam has a written and an oral component. Three weeks after selecting the papers, turn in a 5-10 page report (not counting references) as well as pointers to any software or hardware artifacts created as part of the project (if any). Approximately one week after submitting the report, make an oral presentation to the panel, followed by questions.

- Analysis of Algorithms

- Form a panel of three professors, select 3-4 papers in an area related (but usually not identical) to your thesis work for you to read, review and synthesize over a period of a month (30 days). Write a report on your review/synthesis, give it to the committee, and also make an oral presentation to the committee, followed by questions.

- The candidate student must form a committee of 2-3 faculty members, where at least one is a Visual Computing faculty member.

- The student and the committee agree on a list of at least 5 papers in the student’s research area of interest.

- During the first half hour, the student presents a lecture on the topics in the said papers and any relevant background.

- The second half hour comprises a 30min Q&A session where committee members can ask questions related to the lecture and any of the said papers. This gives the committee an opportunity to assess the general mastery of the research area the student is working on.

PhD Qualifying Examinations - Sample Questions

Below you will find examples of questions from previous PhD Qualifying Examinations (also called Comprehensives or “Comps”).

The issues arising from the relationship between media, technology and society have been examined from different theoretical frameworks, including technological determinism, and social constructivism. Compare and contrast the ideas and approach of McLuhan, Williams and Winner, inter alios to consider both technology as an independent factor and how it is shaped by political and social contexts.

What is the relationship between a semiotic conception of photography and an affective one?

To what extent can national business culture influence the technology adoption life cycle? How could industrial culture affect the way organizations respond to a discontinuous innovation?

In what way does the concept of persuasion apply to evolving forms of digital communication?

What does management theory offer to explain the ways that individuals can develop their own brand alongside organizational brands?

Explain how the medium of comic books and the superhero genre facilitate engagement with fans and the larger cultural landscape.

If you were to design a survey course focusing on key themes and theorists in critical race theory and gender studies, which theorists and readings would you choose and why? How would you structure and develop the course?

How do new technologies problematize existing forms of knowledge? How have scholars theorized these epistemological shifts as they relate to technology’s evolving role in society?

How has research-creation been theorized as a hybrid theory and practice method for the study of media and digital culture? What methodological frameworks have been established in this field? Use examples from the field to provide case studies that integrate theory and practice into creative work.

What is the relation between nationalism, history, and photographic archives?

Taking into account a wide array of cultural, political, and economic considerations, account for the viability of an independent Kashmir.

Define and provide an example of a contemporary Black countervisuality by bringing Mirzoeff’s The Right To Look into conversation with Leigh Raiford’s Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare alongside other texts from your list.

Drawing on your list, explain how race was made and operationalized in the world.

The term “Anthropocene” is contested by many scholars. Outline the major debates in the emerging field of study associated with the Anthropocene.

Cooperation between arctic countries has been strong since the end of the Cold War; however, the media describes the relationship between arctic countries as tense, in part because military exercises in the area are increasing and the political rhetoric is sometimes adversarial. Discuss the geopolitical situation in the Arctic from the perspectives of academic scholars and the media.

Discuss how race-centric far-right movements like the American ‘Alt-Right’ can exist amorphously – with no strict rules, leaders, or goals – and yet maintain momentum in terms of producing violent effects, upholding followers, or fostering adjacent racist trends. What is the function of concepts like race and nationhood, which uphold racializing systems, in sustaining that momentum? Are there limitations to that success?

Healy (2015) differentiates between effective and obstructive use of detail and nuance in sociological writing and theory. They discuss how all abstraction requires the deletion of some detail, and argue that nuance for the sake of nuance can get in the way of effective theorizing. At first glance, Healy’s position appears to sharply contrast with ethnography’s traditional emphasis on detailed, contextual thick description (Geertz, Lambeck). However, some contemporary ethnographic work (e.g. Stewart, Bubandt) suggests by example that theoretical abstraction can be paired with strategic deployments of detail to evoke new depictions and definitions of culture. Is it useful to apply Healy’s critique to anthropological work? If so, what is gained through its application? In your answer, show specific examples of how extensive detail or description is useful for contemporary ethnography, and when or whether adherence to ethnographic detail gets in the way of theorizing culture.

How does the early development of the field of visual culture elide the importance of materiality?

There is a growing body of literature related to psychology and games. Describe the current state in the cognitive and social psychology literature, and how it has been applied within game design and gameplay?

The proliferation of new technologies and their impact on culture has been debated by media scholars. Some theorists take the position that digital technologies create new possibilities for interconnectedness, improved access to information, and engender communities of support and belonging. Others caution that a cultural emphasis on and preoccupation with digital technology is creating deep divides in our culture, generating a sense of individual isolation and social anxiety. These debates, at times, focus on the impact of technologies on human empathy, relationships, and the quality, or lack thereof, of social discourse afforded by digital technologies. Develop these positions, with attention to how these two positions have been theorized in media scholarship. What is your position in this debate?

The Internet and cellphones are examples of technologies that were not only globally accepted but also spread rapidly. There are other technologies that do not share the same level of success despite technical capability. Could this phenomenon be explained by characteristics of technology that are associated with cultural values? How might this association affect technology diffusion?

Charting the emergence of Islamic art within Art History, what are the advantages and disadvantages of using this rubric when studying historical and contemporary art from the MENASA region and its diasporas? Further, are there alternative categories that can be deployed to research this area?

Considering the diversity in exhibitionary lineages between different past and present colonized communities, how has the curatorial been employed to forge new solidarities that challenge historical exclusions/appropriations and formulate more dialogic pathways?

Using theories of communication and cultural studies, consider the role of popular culture in the conception, creation, and portrayal of social robots.

An emerging problematic in theories of material culture and dress centres on moving beyond viewing the fashion object as passive, and instead interpreting material as an influencer of bodies, experiences, and cultures. Whereas foundational fashion studies scholars studied the subjective experience of those who engaged with the material object, more recent scholarship has complicated these perspectives by introducing the object as an active force with agency of its own. Considering these divergent approaches, assess theories of material culture in relation to the fashion object.

Explore the ways in which scholarship in the field has highlighted a turn to affective and psychosocial regulation in postfeminist culture. Given postfeminism’s propensity toward exacting regimes of self-improvement and surveillance, how does this shift indicate prevailing themes and/or critical changes in an ongoing regulation of gendered subjects?

How have comic studies addressed race and gender, and how have they failed?

The Anthropocene is said to challenge the notion that nature and culture are two separate entities. Explain how scholars have explored this idea.

Disciplinary “turns” – while provoking debate – can also engender new methodological and theoretical modes of practice. Describe the “ontological turn” in anthropology, discuss its criticisms, and examine its points of contact and/or contrast with other contemporary ethnographic work. What does the ontological turn provide, in terms of alternative ways of doing ethnography (whether in terms of fieldwork, writing, or otherwise)? Are there further ways the principles of the ontological turn have been or could be used or extended? Can the ontological turn be synthesized with other contemporary developments in ethnography?

What is the ‘documentary mode’ in photography? Discuss its major tenets and criticisms.

A prominent feature of many recent games has been improved graphical realism and the implementation of avatar customization for the playable character. Discuss the role avatars have played in current research and explorations within HCI and digital games?

In fashion studies scholars have laid claim to a unique connection between fashion and modernity, with fashion historians and theorists asserting ties between “modernism,” “modernity,” and “la mode.” Using fashion as a starting point, what connections can be traced more broadly and/or problematized by viewing these ties through the lens of material culture and the processes of cultural production and consumption?

What are the barriers to sustainable education among fashion consumers? How can long-term sustainable fashion be fostered through education?

If you were to construct an undergraduate course on modest fashion, what rationale would you use to synthesize your research material into a comprehensible, dynamic, and relevant overview? What theories and historical processes would you draw on? What audio-visual materials and written materials would be included? What pedagogical philosophy would underpin the course?

What is the ‘girl’ in girls’ studies? How has the field theorized the concept of girlhood as well as the possibilities in expanding and diversifying the construction and categorizations of ‘girl’?

How do different theorists approach the intersection of the material, visual and textual in fashion?

Can moving-image be theory? Discuss with reference to the texts on your list.

How do Black feminisms in Canada inform academia about black women’s lives and how to make black women legible? In particular, how do Black feminisms help position black women as human and include black women in the human historical, social and political project?

Discuss the tensions between mainstream accounts of journalism history, and Black press accounts of history? In what ways can the mainstream historical narrative be revisited through a focus on the Black Press?

Explain how museums, their collections, archives, and concomitant exhibitions are thought of as constituting ‘history from above,’ and how this is countered via ‘histories from below.’

Affect has become an influential way of thinking about emotions and psychology within game studies. How has affect been discussed in scholarship related to game studies with regard to its relationship to player behaviours?

McLuhan (1964) argued that through the advent of electric technologies human beings have externalized their central nervous systems, calling this extension of the self “a desperate suicidal autoamputation, as if the central nervous system could no longer depend on the physical organs to be protective buffers against the slings and arrows of outrageous mechanism” (p. 111). Have new digital technologies increased individual anxieties, degraded individual and collective senses of self, and degenerated social bonds and devolved discourse? Drawing upon selected theorists, make an argument for or against digital technologies creating greater individual or cultural anxieties.

“Big Other’s” ecosystem and its blind eye of radical indifference. Assuming that platforms are inevitable and that people are part of this connective culture; how does the relationship between its interdependence and interoperability, which are fundamental to platforms’ strategy, affect collective privacy? Why is this relationship crucial to our “right to the future tense”?

Cultural producers become platform complementors as the winner-take-all orientation and network effects strategy result in a siloed-fenced-garden ecosystem in which standardization is mandatory. How is cultural production being affected by this relationship? How are platforms’ strategies, values, and politics influencing the relationship between cultural producers and their audience? Why might this relation be pivotal to the business and future of platforms?

If you were to design a survey course focusing on the topic of digital content branding, which theorists and readings would you choose and why? How would you structure and develop the course?

How is labour conceptualized and discussed in the academic discourse of Creative Industries? In what ways are issues of social and cultural inequality part of the discourse?

Situate science and technology studies in its historical cultural context. What are the origins, contributing disciplines, and key theorists? How do these overlap with the field of communication studies? What problems have both fields attempted to address?

In museum and archive studies, collecting has been theorized across a wide range of interdisciplinary perspectives. By drawing on relevant theories, trace the diverse approaches for studying the act of collecting, as they relate to dress studies in the museum, the archive, and private collections. Your discussion should speak to the central debates regarding collection and curatorial practices in dress studies.

Outline major theories on the production of space. What is the critical utility of these theories?

What does climate change reveal about the social production of space? How can these revelations be articulated?

With reference to the principal themes, debates, and theoretical issues, define how modesty has been understood in fashion studies and articulate how perspectives on modesty can be challenged from a decolonizing perspective.

Aerial and nonhuman viewpoints in photography is a major precursor to art responding to the Anthropocene. How is the nonhuman viewpoint currently understood in Anthropocene art, and how are artists challenging or reinforcing this approach to making Anthropocene-related art?

Across a selection of ethnographic monographs (Bubandt, Garcia, Biehl), journaled reviews (Bialecki, Bessire & Bond, Robbins), and experimental texts on new ethnography and creative methods (Elliot & Culhane, Pandian & McLean), there emerges a theme of “taking seriously”. For these texts, the concept of “taking seriously” is applied in various ways, and helps form authors’ critiques of traditional and contemporary ways of doing ethnographic theory, data collection, and written form. Describe and compare these uses of “taking seriously” as a conceptual tool, and discuss the historical, methodological, and theoretical critiques they forward. Are these critiques warranted? Contrast work that foregrounds the concept of “taking seriously” with other contemporary ethnographic work that does not in order to show what distinctive insights and/or limitations this foregrounding can generate.

To what extent is the “fresh cookie” conundrum (does the cookie sell more because it is fresh? Or, is it fresh because it sells more?) applicable to social media algorithms? Are automated decision-making tools that inform social media a reflection of social and political structural inequities or vice versa? How are the relationship between biased prejudice and the development of secret algorithms affecting the way people engage in social media? Can we find a solution to the “internet freedom oxymoron”?

How should we understand the work that the audience does in the digital environment?

How does neoliberal ideology in creative economy frameworks exacerbate issues around inclusivity and diversity, both in cultural participation and in cultural production?

Describe how the methods used to study communication and emotion in humans can be leveraged for the study of social robots.

Design a queer inclusive toolkit to tackle queer exclusivity and exclusive policies. In the toolkit, refer to academic literature, theorists, and scholars in the field to support your document. Consider the impact the toolkit will have (e.g., metrics and measurement of its use and success). How will you ensure that the toolkit supports your intention?

What are some of the implications of queer inclusive/exclusive policies for the lived experiences of queer athletes? How do these implications shift or change depending on given sport spaces?

Explain how intersectionality challenges understandings of identity formation in fashion studies and discuss how useful it is as an organizing principle for the study of modest fashion and how it has expanded research in that field.

Much of the theoretical work with intersectionality has been coopted and stripped of its origins in black feminist thought. Drawing from the body of work by black feminists describe the role of social justice and transformation in intersectional research. Discuss how fashion and intersectionality can be grounded in social transformation.

What might it mean to consider if we have entered a ‘post-postfeminist’ moment? In what ways might new “emergent feminisms” (Keller & Ryan, 2019), social justice discourses, and an increased prevalence of intersectionality, all reveal critical gaps in, or reconsiderations of, foundational postfeminist scholarship and its ubiquity within feminist cultural criticisms?

Explore audiences’ emerging capacity to appropriate, reproduce, and circulate celebrity, (their image and persona), within digital culture. How might scholarly consideration of these practices as a ‘remix’ of digital celebrity further illuminate and extend fan studies scholarship on the affective dynamics of participatory culture and fan labour?

Provide a genealogical reading of Black queer and trans documentary cinema. Using select texts from your list, discuss the relevant critical issues and themes.

Endangered life is often used to justify humanitarian media intervention, but what if suffering humanity is both the fuel and outcome of such media representations? Pooja Rangan argues that this vicious circle is the result of immediation, a prevailing documentary ethos that seeks to render human suffering urgent and immediate at all costs. What is the commemorative value and ethics of documentary value in such contexts?

How has the ‘archival turn’ impacted the ways photographs are thought about in archival theory?

In what ways has the centrality of nation state actors in communications governance been displaced by new non-state actors since the emergence of internet communications?

According to some studies, digital representations of a player character can alter behaviour and decision-making in virtual worlds (Yee et al., 2009; Yee & Bailenson, 2007; Fox et al., 2013). Yee et al. (2009) coined the term the Proteus Effect for behavioural changes in game players who selected avatars that differed from their own physical forms. Using your theorists and research evidence, explain how immersive embodiment is said to enhance training, learning and communication. What are the issues with these claims?

Discuss Édouard Glissant’s archipelagic thinking in relation to other postcolonial works on diaspora, racial multiplicity, and cultural syncretism. Can such comparative studies on race illuminate our understanding of ethnicities in relation?

How has the relationship between Islamic Art, institutions, and their patrons developed in the post-9/11 context? Using an institutional case study, consider the role of funders in developing the narrative of historical and contemporary Islamic Art.

Identify and describe three key influences of communication studies in the formation of science and technology studies.

As a scholarly field, dress studies faces a challenge shared by practice-based approaches of preserving the fashion object, while still allowing these ephemeral materials to be accessed by researchers and the public. How have digital technologies impacted these approaches? Your answer should address the methodological challenges faced by both conservators and curators when incorporating digital methodologies.

In what ways does bounded rationality affect the optimal decision-making ability of sustainable fashion consumption?

How do key scholarly contributions in girls’ studies contemplate a prevailing social investment in girls; subsequently, how does this literature mediate debates and ideas on the collective anxieties and fixations that surround contemporary girlhood?

Examine different approaches to the body and non-visual senses in visual culture, highlighting complementary and conflicting debates.

“Popular culture is made by the people, not produced by the culture industry.” (Fiske, 1989, pg.24). Discuss the validity of this claim and how it relates to both audience studies and fan cultures.

Using Castells, Dyer-Witheford, and Moody, how does technological change result from and affect relations of labour?

Design an undergraduate course on Black studies. Provide the syllabus and rationalize your choices.

Critical technology scholars work to confront the social, historical, and ideological forces that shape our experiences with and the development of technology. While some authors develop direct explanations or tentative solutions to matters of continuing oppression (Noble, Barlett, Gallon), others provide more abstract critiques. Summarizing and combining abstract discussions and anti-oppressive strategies from critical media and technology studies, develop a critical concept that could be applied to contemporary research contexts.

Who controls the internet? Drawing on readings from across your comps lists, propose a theoretical framework for how we ought to understand power and control in regards to the internet and forward and argument about contemporary power relations.

If according to Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, the postcolonial incorporates multiple chronologies, what are some of the beginnings of postcolonialism and in what ways have these origins been activated and altered function in the global art historical turn?

Compare and contrast how the academic fields of comics studies and fan studies conceptualize and situate audiences/consumers in their fields. Are “audiences,” “consumers,” and “fans” framed differently as subjects in these fields?

Discuss how Stuart Hall’s theories of cultural representation have influenced the field of cultural studies with reference to how subjects are positioned.

Imagine that you have just completed instructing a survey or introductory course exploring intersectionality in sport activism. It is your closing lecture. Explain the important highlights from the class in terms of subjects and knowledge and why you delivered the course in the way that you did.

With reference to the principal themes, debates, and theoretical and/or methodological issues, define “critical fashion” as an object of study and articulate how Indigenous fashion engages with and challenges the field.

How are objects discussed and theorized in relation to biography and memory?

If you were to design a course syllabus on “Diversity, Representation and the Comic Form”, what texts and theorists would you choose and why? Describe how you would structure your course in terms of reading assignments and exercises. If you choose to include film examples and case studies, mention those as well.

In the past, audience and fan studies have been criticized for its absence of race and gender interventions. Has scholarship addressed this oversight well enough or have their efforts been tokenized?

How has Visual Studies developed over the last 30 years? Does Visual Studies represent an independent academic discipline or an interdisciplinary field? Does this matter? What are the implications of each for the study of Visual Culture?

Discuss the more contemporary (i.e. post- Cold War) dimensions of the Kashmir crisis, paying particular attention to recent domestic events in India and Pakistan, as well as broader regional and international developments.

Discuss the broad historiography of scholarship on the Kashmir conflict, identifying major issues, schools of thought, prospects for resolution, and the difficulties confronting any scholar dealing with the topic.

How does technological change result from and affect relations of power? (e.g. Fuchs, Kline et al, Terranova)

Discuss the artistic responses to the notion of the Anthropocene in photography and video. What themes, topics, and representational strategies are used to depict the Anthropocene?

How does photography operate at the intersection of personal memory and social history?

As a practice and method, digital ethnography emphasizes multi-modality of interactions as well as a multi-sited approach. How can this approach be used to remedy any shortcomings in traditional ethnographic approaches?

Are digital games empathy machines? How do they differ from other modalities in their ability to produce affective empathy? Engage with selected theorists to make a case for or against games as uniquely capable in creating fellow feeling for another’s lived experience.

Based on the progression and evolution of sustainable fashion, how do you anticipate our understanding of sustainable fashion will evolve in the next 10 years?

How are digital platforms involved in the production of tourism commodities? What dynamics do platforms introduce to the political economy of tourism?

How has girls’ studies scholarship understood the significance of girls’ visibilities and participation in digital culture? How are girls’ emerging contributions in digital media industries, and girls’ production and/or consumption of content in online spaces, analyzed and theorized in this field?

Survey and discuss changes in the field of creative industries, focusing on issues of race and social justice. How does Indigenous cultural sovereignty enter into this discussion?

What is the impact of major theorists on communication and culture? Using major schools of thought (Frankfurt, Birmingham, and Toronto) discuss the main themes and direction of the literature.

Examining the research and views of social marginalization, in respect to race, class, and gender, compare theories of how and to what purpose social marginalization occurs, using Ahmed, Butler, Foucault, and Hall.

Explain how actor-network theory describes society’s relationship to technology and other nonhuman actors, and what the significance of nonhuman actors is in conceptualizing technological innovation. Discuss critiques of this theory from various scholars’ perspectives.

Describe the ideas and approaches of Manovich, Kittler, Fuller, Kitchin and Dodge, inter alios, the impact of software in society, and how the work of these scholars informs our understanding of the relationship between software and gender.

How has the positionality of colonial privilege been challenged in contemporary acts of commemoration?

Three key concepts developed within critical race, racism, and critical whiteness studies are citizenship, sovereign nationhood, and racializing discourse. Compare, combine, or contrast these concepts and discuss their utility in articulating the social function and constitution of race and racism.

How has the visual field been theorized as a place where power is constituted? How has that power been countered?

Game play’s vaunted “magic circle” is a space that games create for players to detach themselves from ordinary life and experience problem-solving outside of the constraints of reality (Salen & Zimmerman, 2004; Huizinga, 1950). The magic circle is a protective frame which stands between the player and the real world and it problems. Using your theorists, engage with the concept of a magic circle. Do you believe in the magic circle? Is it a necessary aspect of game play and an element that attracts people to games?

Chart the emergence of research creation and inclusion-based models within curatorial projects in the 21st century, including exhibitions, public programs, and publications. In what ways has durational and collaborative research become a precept in the contemporary field of the curatorial?

An important theoretical, social, and cultural space in modernist studies is the city and the urban landscape. Discuss the figure of the flâneur as a touchstone of urban modernity with reference to specific, relevant theories. Address how issues of gender, race, and class figure in the diverse conceptualizations of this figure. In formulating your argument, consider centrally how diverse theories configure the flâneur vis-à-vis processes of cultural production and consumption.

Consider how scholars of postfeminism engage with debates surrounding women’s attachment to a culture and media that feminist activism might situate as oppressive, harmful and misogynistic. What theories and frameworks are offered to mediate debates on women’s apparent passivity, complicity, or resistance within this culture, and how can these attachments to hegemonic cultural ideologies be theorized?

How are issues of politics and visual culture related? With specific reference to discussions, theorists, and artists working in the field of visual culture, argue or describe the importance of the political dimension of practices (production and circulation) in visual culture?

Summarize and comment on how structures of power are established and maintained through the division of labour (Althusser, Durkheim, Marx, Thompson, Veblen)

What lessons are there in Black feminist thought for present-day activism and scholarship?

If you were to design a course focusing on the use of digital technology in art practices, which theorists and readings would you choose and why? How would you structure and develop the course?

Identify and describe some of the limitations that undermine social media’s potential to develop democracy, and explain how computer-mediated communications have the potential to expand the role of the public in political discourses and enhance the democratic process.

Social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube provide users with diverse participatory environments and accessible tools for public communication and political activism. Individuals use social media to try to make their issues known and publicly visible. Explain how these platforms have been used both as a tool to publicize and mobilize political activism and as a tool for law enforcement, propaganda and surveillance.

From the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street and Tahrir Square to the Maidan, the mobile phone with its built-in video camera has been an invaluable ally in witnessing and documenting revolution, civil unrest, protests, police brutality, beheadings, and state sanctioned terror in the 21 st century. What are the possibilities and limitations of social media and mobile phones in particular, for witnessing social change?

In the mid to late 20 th century, live “happenings” were a staple of theoretician and performance artist Alan Kaprow wherein by design, the audience became part of the live performances. Similarly, in the early 21 st century, Philip Auslander ascribed the term “liveness” to both the live performance as well as the audience engagement within an environment that directly shaped the relational aesthetic (Bishop) between the audience and the performance/performers. What does the concept of ‘liveness’ add to the concepts of performance, participation and to the documentary form?

Do theories of public communication and political economy adequately account for the “irrational” dimensions of communication such as affective, subjective and emotional? Bringing the work of three or four scholars working in these theories into dialogue with political economy and/or public sphere approaches, reflect on if and how these elements can combine into a singular viable theoretical framework.

Discuss and critique the various understandings of “data” in Human-Robot Interaction, communication, and emotion research.

What insights about power and gender have you gained as a result of examining queer inclusive/exclusive policies? Imagine you are presenting your reflection to a sport governing body or an agency about to embark on writing such a policy. Review the many levels of power, decision making, influence, and beliefs they (governing bodies/agencies) have on policy making and/or stakeholders.

How can framing and identity affect the way we view sustainable fashion consumption?

How are places defined, and who has the power to define them?

Discuss how consumption can be understood as a system of control, using Debord, Baudrillard, and Veblen.

Deconstruct/analyze the pedagogical role of relationships in black and Indigenous methodologies.

What is the rationale for interdisciplinarity in Human-Robot Interaction/Human Computer Interaction?

Provide an overview and critically discuss research methods currently being applied in Human-Robot Interaction, communication studies, and the expression of human emotion.

Compare and contrast competing definitions of sustainability outside of and within the field of fashion.

What responsibilities does the consumer have in educating themselves about sustainable fashion?

What are tourism commodities? To what extent are tourist destinations commodified spaces?

Trace the genealogy of arts-based, arts-informed, practice-based, multi-modal research, and research creation by exploring the similarities, differences, and tensions between them.

How do fashion exhibitions fit within theories of “new” museology?

How have black and Indigenous methodologies shaped the conversations around knowledge production, consciousness raising and empowerment of communities?

How did the Black press in the 19th and 20th centuries circulate, and for which reasons? How did black women in particular participate in and make use of the Black press?

The use of digital technology in creating artworks has changed art as artefact to art as experience. Explain how interactive art has transformed the nature of audience experience, and how audience engagement assists digital artists in conducting practice-based research to further understand art and its viewers.

Discuss the key barriers to commercial and shipping activities in and around the Arctic Ocean. How is the Canadian Government responding to these barriers, and what does this mean for issues of Arctic sovereignty in Canada?

The concept of discourse has played a key role in critical race, racism, and critical whiteness studies (Chavez, Lensmire, Bonilla-Silva, Weed, Hanbrink). Some authors have expanded the term with concepts such as “inter-discursivity” (Parsons-Dick) and have implicated discursive means within racialized constructions of law, education, and other institutions (Capers, Alexander, Gillborn, Tallbear, Leonardo, Simpson). Discuss the work that the concept of discourse and its extensions do across varying texts.

What are the main areas of contestation arising from the emergence of Visual Studies, and its study of visual culture, as a separate, distinct field from Art History?

What is it about modern museum logic that amplifies the unruly nature of photographs, and vise-versa?

Using the frameworks and theories of platform studies and media archeology, explore how virtual reality has been positioned as in interface technology throughout its history. What has changed in the contemporary discourse about virtual reality?

How have international exhibitions, from world fairs to biennales, produced the status of the national and the global, since the Great Exhibition of 1851? Include historical and political events that contributed to the development of the curatorial in the 19th century and early 20th century.

How have theorists, artists and activists theorized artistic practices as forms of resistance? How do these theories apply to the everyday spaces of contemporary digital media? Provide examples of artistic resistance within the field of new media art.

Discuss how intersectionality has challenged theories of identity and embodiment in fashion studies. How has it been used in fashion studies research and research in gender studies that engages with fashion? Discuss the gaps and the next horizon for research that will further advance knowledge in the field of fashion studies.

Select three moving-image texts from your list and offer a critical reading that comments on how each has chosen to situate Blackness and queerness within its sociocultural landscape. Draw upon the theorists and scholarship from your list in order to support this reading and discuss whether or not it is useful to think of these films/videos in this way.

One of the most significant recent phenomena in visual cultures around the world is the explosion of the selfie culture—the documentation of the self. The selfie culture, with its own visual culture and commemoration, is not only predicated on documenting the everyday and the mundane it can also bear witness to violence, trauma and memory. How does the selfie’s prominence and ubiquity aid in documenting and commemorating visual culture?

Social media platforms rely on user-generated content as the basis of their economic model. What does platform studies tell us about the monetization strategies of social media platforms, and how they shape how content is presented on these platforms?

Discuss Édouard Glissant’s archipelagic thinking in relation to other postcolonial works on diaspora, racial multiplicity, and cultural syncretism. How can such comparative studies on race outline possibilities for transcultural solidarities?

How do different models of networked agency account for distributions of power and causality across large systems?

In his 2011 article “The Object of Fashion: Methodological Approaches to the History of Fashion,” fashion historian Giorgio Riello traces three branches of fashion analysis: the history of dress and costume (focusing on historical and object-based methods), fashion theory or fashion studies (involving a distancing from artefacts), and the material culture of fashion (an interdisciplinary method). Reflecting on Riello’s positionality, how do other scholars understand the field especially the last two streams—fashion theory and fashion studies, as well as the material culture of fashion? More generally, can one really engage the material culture of fashion without any kind of theory, and if so what does that tell us about some understandings of theory?

Imagine that you have just completed instructing a survey or introductory course exploring queer theory and sports. It is your closing lecture. Explain the important highlights from the class in terms of subjects and knowledge and why you delivered the course in the way that you did.

How have different modes of mobile visuality been theorized, especially around the theme of modernity?

How should we interpret photographs of political violence and armed conflict?

From Jean Rouch to Mike Broomfield, Barbara Kopple to Ngozi Onwurah, Spike Lee to Michael Moore these directors have participated/performed in their documentary films as intentional and/or inadvertent subjects, narrators, directors and crew. How have these documentarians negotiated an expectation for veracity in documentary and to what degree has “performance, race; and spectatorship” (Bruzzi, 2000) factored into the relationship between the story and the audience?

Phillips and Milner (2017) discuss the concept of “ambivalence” as a framework for mapping participatory Internet culture. In the context of their application, what does this use accomplish? Could such a concept be applied or combined with other theories or contexts within critical media & technology studies? If so, provide an example, and discuss advantages or disadvantages of this.

Games scholarship has focused heavily on game design in the last 10+ years, highlighting the need for academics to understand the implications of game design on the interactions players have with technologies. Describe current approaches within HCI and digital game design.

How is cultural production being affected by platforms’ ecosystem? How are the relationships between rationalization, information processing, and reciprocal communication, which are central to the idea of control and platformization, influencing cultural production? Which other aspects related to this techno-economic alignment could also influence the way people produce and consume culture?

Apply historical understandings of presentations of self to digital environments to explore the underlying contributions and gaps of these environments for further consideration.

How are constructs of whiteness and masculinity defined and situated within the fields of critical race theory and gender studies? Discuss how each field intervenes in these forms of social and cultural hegemony.

Discuss the way in which stories told through archives, museums, and exhibitions can be the locations for both the subjugation and the resurgence of marginalized voices. What are some of the key theoretical debates surrounding the marshalling of the exhibition space as a locus for empowerment and positive social change? Formulate an argument regarding the intersection of curatorial practices and diversity.

There are many voices in queer theory. One could argue that race and eurocentrism are not major features of queer theory. Situate your research in relation to key debates around these issues in the field.

Position yourself and your research in relation to queer theory. Explain the relationship between queer theory and sport and the importance of applying a queer theoretical framework in academic literature/writing on sport-based research. Provide at least one example of existing sport-related research that effectively uses a queer theoretical framework and one example of existing sport-related research that would benefit from a more fulsome application of queer theory.

State and societal apparatuses protect the sartorial privileges of some bodies and mobilize the policing of others. Drawing on literature from gender and fashion studies among others, discuss how fashion reinforces these realities.

With reference to the principal themes, debates, and theoretical and/or methodological issues, define “arts- and media-engaged research” as a method of study and articulate how fashion studies can benefit from and engage with digital storytelling.

What has the role of fashion been in crafting cultural identity and mobilizing the politics of marginalized and oppressed groups? Drawing on literature about Black and queer fashion, among others, discuss how Indigenous makers might use fashion in similar ways.

How would you structure and develop a survey course focusing on Indigenous resurgence through the fashion and the creative industries?

Based on current literature, what are the foundational principles of decolonizing methodologies? Describe and analyze examples of decolonizing methodologies with specific methods as they are applied to research on fashion and the creative industries.

If you were to design a survey course on fashion studies, which theorists and readings would you choose and why?

Who is answerable for these images and what is the ethical responsibility of the image-maker, the spectator, and those represented?

History, memory and photography are intricately connected, yet the study of photographs as evidence in the discipline of history is a relatively recent phenomenon. Discuss the difficulty of analyzing photographs as historical documents, some of the central issues related to the specific ontology of photography, and the manner in which theorists, historians, and artists have approached the study and use of photographs as evidence of the past. Make sure to situate your own perspective, supported by evidence from the texts, within your essay.

Explain the makings of the Canadian nation state and its employment of racialization using the texts on your list.

What are the various ways we can understand the relationship and connections between content creators and their audiences on social media?

Should the responsibility of educating oneself about the ‘safest’ and most ‘responsible’ garment choice lay with citizens (i.e., consumers) or should the responsibility be on governments to ensure only safe and responsible products are available for citizens to purchase, thus alleviating citizens of the need to become experts on all product categories?

How does intersectionality disrupt, challenge, change the frameworks of arts- and media-engaged research methods in use in fashion studies?

Design a syllabus for the course entitled “Taylor Swift: Celebrity in the Digital Age”, which will aim to illuminate the intersections and convergences between the key arguments and literature in this field. Demonstrate the ways in which the scholarship in the field could be communicated and organized in the structure of an academic course.

How can an understanding of the affordances of digital platforms (e.g., Twitter, Instagram, TikTok) utilized by celebrities and their audiences illuminate the varied ways in which celebrity is understood to operate and circulate affect in digital culture? How might celebrity appear differently according to the structures of these platforms, and how might some platforms facilitate the different types of celebrity explored in the scholarship in this field?

While many theorists in the latter half of the twentieth century have argued that the photographic archive represents a totalizing space that controls and shapes the dissemination of knowledge, recently others have challenged this notion and instead have shown the ability of archives to challenge institutional power. With reference to the principal themes, debates, and theoretical and/or methodological issues, discuss this debate and your own position within it along with reference to specific artists and theorists.

How does Susan Sontag articulate, position, and/or construct the audience in relation to the body in pain in Regarding the Pain of Others? Consider, assess and bring her work into dialogue with other texts from your list.

The technological and digital revolutions of the early 21 st century greatly influenced and impacted the engagement, consumption and commercialization of all media. How does the changing technology impact the nature of community, social networks and public access?

Authors in critical technology studies have pointed out technology’s tendency to replicate pre-existing systems of racial and gendered oppression in new forms (Nakamura, Noble, Zuckerburg, Gallon). Simultaneously, authors in digital and Internet cultural studies have mapped nuanced potential opportunities for non-normative life or resistance, provided by the affordances of digitally mediated communication (Milner, Phillips & Milner, Boellstorff, Noble, Barnett et al., Khazraee & Novak). Discuss whether and how these seemingly divergent conceptual approaches might be worked together. Do they entail different understandings of digitally mediated communication, or do they together capture its contradictions?

The literatures of the public sphere, political economy, and on communications industry practice give different perspectives on the roles and responsibilities of communication for the public interest. What implications does this have for the way we consider the role of private sector practices in public life?

In what ways has digital ethnography been applied to digital media and games? How has the application of digital ethnography changed the academic framing of digital spaces?

In the field of Cultural Studies, media is the site for both hegemony and resistance. Following this approach, what are the processes and strategies through which racialized cultural producers have displaced Eurocentric media to provide counter-narratives?

What are the gaps in collections of Islamic art, in terms of media, geography, and period? Define these gaps to illustrate the ways in which they systematized collecting practices of Western institutions, from the 1800 to the present?

Describe the relationship between production and consumption in creative economy frameworks. How is consumption situated within a creative economy framework, and how are products valued? Discuss with reference to the comics industry.

What is intersectionality? How does intersectionality operate as a framework in examining the nuances and interconnections in racial and gender inequalities? How are structures of power defined according to critical race theory and gender studies?

Using a communication studies perspective, discuss the role of science and technology studies in contemporary cultural discourses.

Demonstrate how communication theory can be used to explain the relationship between popular culture representations of social robots and their development.

How do STS theories account for the concealment of values and politics within technical designs? To what extent do contemporary software platforms and digital infrastructures extend notions of “the black box”?

Intersectionality is an important framework to include in analyses of sport and activism. Provide an overview of the framework and explain how it can enhance understandings of sports and activism. Incorporate at least one example of existing sport-related research that effectively uses an intersectional framework and one example of existing sport-related research that would benefit from an intersectional framework.

Should there be one singular global definition of sustainable fashion or allow for multiple definitions that honour pluriverse (pluralism)? Can a definition be established that is fluid and adaptable?

What are the different ways in which consumers can practice sustainable fashion and does the current definition of sustainable fashion encompass all of the ways to be sustainable?

Identify major theoretical perspectives on the relationship between nature and the value form under capitalism.

What is Indigenous land-based education and how can it be applied to fashion and the creative industries? What are the merits of Indigenous pedagogical literature for land-based education, and how can it contribute to decolonization?

Critically analyze contemporary feminist literature on Muslim women’s agency, representation, and subjectivity and discuss the relevance or limitations of key approaches.

Design an undergraduate course in visual culture. Provide the syllabus and rationalize your choices with reference to the field of visual culture as a whole.

In considering the concept of autonomous technology, scholars have debated the idea of technological development being self-propelling, self-sustaining and following its own independent course. Discuss the theoretical contributions scholars such as Winner, Ellul, Marcuse and Mumford, inter alios have made to the concept of autonomous technology, considering the strengths and limitations of their ideas.

Discuss how scholars have applied the concept of affordances to social media, including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, to different contexts. Use examples of contemporary political activism to demonstrate how affordances in social media have played a major role in enhancing political movements.

In Claiming the Real II (Winston, 2008), the documentary form is seen as an advocate for social justice and an ally of the public. Over its century of evolution, the audiences’ faith in ‘documentary’ films to reveal the truth continues to set it apart from other forms of storytelling media. What constitutes truth in the documentary form?

From the cinema to the gallery, from direct cinema to re-enactment, from citizen journalism to documentary podcasts, ‘documentary’ continues to engage and enrage the public. How has documentary’s ability to influence real and imagined change in the context of the 21 st century shifted in response to digital media?

What are the compatibilities and incompatibilities between the political economy approach and platform studies?

Assuming that people carry values or, as Hofstede named, “mental programs” that are developed, shaped, and influenced by several institutions such as family, schools, and organizations; how is the relationship between the individual and the media being affected by the inevitability of technology? Why is this central to the idea of technological diffusion?

Life is a collection of experiences. How we feel in regard to these experiences is crucial in determining happiness, things we like to do, and people we want to engage with. How is the relationship between attention, reputation, interaction, and co-creation of value influencing engagement in social media? Moreover, why might this association be more harmful to equity-seeking groups?

The task of deciding whom to trust, what to choose, and which ideas to support in the “look-at-me” market is challenging. How is the association of deindividuation, attentional manipulations, automated reputation systems, and electronic engagement affecting our digital experience; hence, making the aforementioned task even harder? How could some communities be privileged over others as an outcome of our digital experience?

How have scholars theorized technological systems as embodiments of ideology and social control? Articulate this debate with reference to the emergence of algorithmic forms of control and governance.

In his study of fashion and semiotics, Roland Barthes argues for an understanding of fashion as a system of signification, even going so far as to see fashion as a form of communication (especially in the case of the language of fashion magazines and fashion photography). For Barthes, there are two modes for understanding the structures of fashion: the first, real clothing, “is burdened with practical consideration (protection, modesty, adornment); the second, represented clothing (through image and text), “which no longer serves to protect, to cover, to adorn, but at most to signify protection, modesty, or adornment.” (8). Discuss Barthes’ two versions of fashion in relation to specific examples of material culture objects and in conversation with more recent feminist theoretical frameworks of fashion.

In his essay “The Painter of Modern Life” (1863), French poet Charles Baudelaire provides an influential definition of modernity, describing it as “the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable” (13). What are some of the arguments in modernist studies that support or contest Baudelaire’s understanding of modernity? By reflecting also on the more recent focus on “modernisms” in the plural, how do these concepts shine a light on the current critical inquires of cultural production and consumption in a diversity of “modern” contexts?

How does the literature on activism and intersectionality in sport apply to fields outside of academia? Discuss how academic and non-academic approaches can work together to lead to social change.

How is sustainable fashion consumption susceptible to mental accounting?

How does analysis of stereotypes about gender in Islam contribute to understanding contemporary “cultural imperialism”? Discuss at least two examples from your bibliography.

Updated February 2022.

UC Davis Graduate Studies

Doctoral qualifying exam.

MANDATORY IN-PERSON PARTICIPATION IN THE QUALIFYING EXAMINATION - September 10 and forward As of Sept. 10, 2022 and in accordance with the Graduate Council Policy on Service on Advanced Degree Committees , QE’s must be held fully in-person with the option to include up to one committee member participating remotely, other than the QE chair, with Graduate Studies approval of a Remote Participation Request .

The Doctoral Qualifying Examination (QE)

Qualifying exam topics, student eligibility , appl ying to take the qe, committee selection, not pass & the second exam, advancing to candidacy, forms & policy links.

The Qualifying Exam Application

Purpose of the Qualifying Exam

All UC Davis doctoral students must take a Qualifying Examination (QE) to demonstrate they are prepared to advance to candidacy, undertake independent research, and begin the dissertation. Doctoral students may have no more than two opportunities to pass the QE.

The QE evaluates the student’s preparation and potential for doctoral study, including:

Strategies for Success

Review proven QE tips, gathered by students in Professors of the Future, on Acing Your Qualifying Exam .

- Academic preparation in the field, and sufficient understanding of the areas related to the dissertation research.

- Knowledge and understanding of the literature in the field, and the ability to evaluate and integrate those concepts.

- Knowledge and understanding of relevant research methods and applications.

- The viability and originality of the research proposal, and the ability to communicate those topics.

Information below is included in the Doctoral Qualifying Examination policy . The QE must be an oral exam, 2-3 hours in length, and may include a written component covering both breadth and depth of knowledge. Specific format is determined by the graduate program degree requirements which have been approved by Graduate Council. Graduate Council specifies that Qualifying Exams must also have the following essential characteristics:

- Be Interactive

- The examiners must be able to ask questions, hear the answers, and then follow up with another question or comment in response to the student's initial reply. Committee members, individually and collectively, must be able to engage in a discourse with the candidate on topics relevant to the candidate’s area of competence.

- Be a Group Activity

- In addition to the ability to follow up to one's own questions, it is also very important for all examiners to hear all of the questions and all of the student's responses, plus have the ability to interject an alternate follow-up question. The collective wisdom of a group is generally greater than that of the individual. Further having other examiners present serves to moderate the group, to ensure that one examiner does not ask questions that are either trivial or too difficult, and that any one examiner is neither too friendly nor too obstreperous. Thus, to optimize the examination process and evaluation of the candidate, the committee as a whole must collectively: 1) experience the discourse with a candidate, 2) evaluate the candidate’s performance, 3) determine the length and content of the examination, and 4) moderate the demeanor of the candidate and the members of the committee.

- Be Broadly Structured

- Based on the candidate’s past academic, research, and scholarly record and the performance on the examination, the candidate must broadly demonstrate sufficient competence in the selected disciplinary area, which must go beyond the limited area of scholarship associated with a dissertation topic. Further, the candidate must demonstrate the capability for integration and utilization of knowledge and skills that are critical for independent and creative research, thereby qualifying them for advancement to the research-intensive phase of doctoral education.

Student QE Eligibility

To be eligible to take the exam, a student must:

- Be enrolled in the quarter in which the exam will be conducted, or if the exam is held during a break between quarters, the student must have been enrolled in the previous quarter and be enrolled in the subsequent quarter.

- Maintain a minimum cumulative GPA of 3.0 in all course work completed.

- Have completed all degree requirements (including coursework and language examinations), with the possible exception of any requirements being fulfilled during the quarter the QE is to be held.

Applying to take the QE

The exam may not be held until a QE application has been approved by Graduate Studies. QE applications are due to Graduate Studies at least 30 days prior to the expected exam date.

- If requesting an external committee member (employed outside the UC), complete an External Member Request and obtain the member's CV (document, not web-based).

- If requesting a committee member participate remotely, complete the QE Remote Member Request .

- If you are participating in a Designated Emphasis, and haven't yet submitted an application, complete the DE Application .

- The Graduate Coordinator submits the QE Application and any supplemental documents to Graduate Studies for review of student and committee eligibility.