Pain Assessment

You have an important role to play in screening for and assessing pain (RNAO, 2013).

You will often be the first person to recognize that a client is in pain as a result of your assessment including observations. Nurses also spend sustained periods of time with clients, so clients are more likely to share this information with you than with other healthcare professionals. If they say they are in pain, believe them . Trust will disintegrate if clients feel you do not believe them.

Unassessed pain can lead to inadequate pain management and/or untreated pain. This is a serious problem because it can affect many body systems as well as a client’s cognitive capacity and quality of life, and even whether they live or die.

Pain can be difficult to assess because it is a personal experience that affects clients in different ways . Clients may also have difficulty articulating their pain and describing what it feels like. Sometimes pain is invisible, making it difficult to recognize, particularly in someone with chronic pain. The next sections explore the dimensions of pain so that you can develop an understanding of how pain may appear.

Dimensions of Pain Assessment

Pain has many dimensions in terms of how it affects a person (see Table 1 ). The various dimensions of pain can involve various descriptions and considerations (Cleeland, 2009). It is important to be aware that these dimensions are not necessarily separate; for example, the subjective dimension includes cognitive, psychological, and social features. Consider the many dimensions in terms of your pain assessment of the client and which pain assessment tools may be best in certain situations and populations (this will be discussed in more detail later).

Table 1 : Dimensions of pain and related considerations.

Contextualizing Inclusivity

Activity: check your understanding.

Association for the Study of Pain (2020). IASP announces revised definition of pain. https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/iasp-news/iasp-announces-revised-definition-of-pain/

Cleeland, C. (2009). The Brief Pain Inventory: User guide. https://www.mdanderson.org/content/dam/mdanderson/documents/Departments-and-Divisions/Symptom-Research/BPI_UserGuide.pdf

Laitner, M., Erikson, L., Society for Women’s Health Research Osteoarthritis and Chronic Pain Working Group, & Ortman, E. (2021). Understanding the impact of sex and gender in osteoarthritis: Assessing research gaps and unmet needs. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(5). https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8828

RNAO (2013). Assessment and management of pain. 3rd edition. https://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/assessment-and-management-pain

Samulowitz, A., Gremyr, I., Eriksson, E., & Hensing, G. (2018). “Brave men” and “emotional women”: A theory-guided literature review on gender bias in health care and gendered norms towards patients with chronic pain. Pain Research and Management, article ID 6358624. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6358624

Zhang, L., Losin, E., Ashar, Y., Koban, L., & Wager, T. (2021). Gender bias in estimation of others’ pain. The Journal of Pain, 22(9), 1048-1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2021.03.001

Introduction to Health Assessment for the Nursing Professional - Part II Copyright © 2023 by January 2023 is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Pain Assessment

Warum dieses Szenario verwenden?

This scenario is designed for nursing students in a nursing assessment or equivalent introductory course. The scenario encourages the participants to assess the patient, identify normal versus abnormal assessment findings, and use clinical judgment in the evaluation of the assessment findings. The scenario is mapped to the 2019 NCLEX Test Plan Categories for easy integration into nursing curricula. The learning objectives and case study provide a high degree of fidelity within the simulation and facilitate the post-simulation debriefing using the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) competencies.

Zusammenfassung

Sara Lin is an 18-year-old female who presents at the emergency department (ED) with nausea, vomiting, and severe abdominal pain. She has been diagnosed with appendicitis. She is scheduled for surgery and is being admitted to the medical-surgical unit.

The students are expected to perform a pain assessment along with a focused abdominal assessment and identify intervention steps.

Lernziele für das Szenario

Upon completion of the simulation, the student will be able to:

Scenario-specific

- Identify the components of a pain assessment

- Perform a pain assessment

- Discuss the role and responsibility for the nurse when assessing a patient with acute pain

- Perform a focused abdominal assessment

Note: The general objectives are generic in nature and once learners have been exposed to the content, they are expected to maintain competency in these areas. Not every simulation will include all of the general objectives listed.

Lehrplanziele

- Identify personal strengths and weaknesses in light of essential knowledge and skills of nursing

- Conduct assessments in an organized, systematic manner

- Establish a therapeutic environment and alliance for engaging patients and their families

- Document nursing assessment activities in a concise, descriptive, and legally appropriate manner

- Provide a safe environment for both patients and staff while maintaining patient privacy

- Apply principles of infection control, including demonstrating hand washing and appropriate use of personal protective equipment

- Use therapeutic communication techniques in a manner that illustrates caring for the patient’s overall well-being and reflects cultural awareness and psychosocial needs

- Demonstrate a process of critical thinking when conducting an assessment and interpreting data

- Make clinical judgments and decisions using evidence-based practice

Lehrhinweise

The scenario includes a list of the 2019 NCLEX-RN Test Plan Categories that are being addressed in the scenario.

Separater Anhang zum Herunterladen und Ausdrucken: View NCLEX Test Plan Categories 2019

Prior to simulation, the students should be familiar with the following topics:

- Pain assessment, including the components of a pain assessment

- Focused abdominal assessment

Before the simulation begins, all students should:

- Complete all recommended pre-simulation requirements

- Receive an orientation to the simulator and the room

- Understand general objectives, guidelines and expectations for the simulation

- Understand their assigned roles

- Understand time frame expectations

This scenario can be used together with vSim® for Nursing Health Assessment (purchased separately). Used together the products form a blended learning program that includes scenarios for standardized patients, virtual simulations, and online curriculum materials.

Patient safety and quality care outcomes are critically dependent on the competence of health care personnel. Building real competence is a step-by-step process that is gained through experience. It includes acquiring new knowledge and skills, getting used to making quick and safe decisions, and training realistically in teams.

Using blended learning technologies such as online reading assignments, documentation assignments, virtual simulations combined with pre- and post-simulation quizzes, guided reflection questions, classroom teaching and human patient simulations will help students gradually build on their theoretical knowledge, skills, and attitudes and move to a higher level of competence. This approach provides a coherent and meaningful learning process which enable the students to put the pieces together from the different disciplines that they have encountered during their education.

When using blended learning, the students can be introduced to the same scenario in different formats. For example, after completing the necessary knowledge acquisition, they can care for a patient in a computer simulation with focus mainly on the cognitive element of patient care and on clinical decision-making. Next, they will meet the same patient in a simulation with a human patient simulator. This will add complexity of having to perform procedures and communicate with the patient, family, and health care team members. When the students experience the same patient encounter through different technologies, it help to reinforce theoretical knowledge and gradually build confidence and competence.

More information about vSim ® for Nursing can be found on Laerdal Medical’s vSim for Nursing product site.

Related Scenarios

This scenario is part of a set of 10 scenarios focusing on health assessment for nursing

Head-to-Toe Assessment

Peripheral Vascular System Assessment

Abdominal System Assessment

Vorbereiten

Nachbesprechung.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.3: Pain Assessment Methods

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 76837

- Ernstmeyer & Christman (Eds.)

- Chippewa Valley Technical College via OpenRN

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Asking a patient to rate the severity of their pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with “0” being no pain and “10” being the worst pain imaginable is a common question used to screen patients for pain. However, according to The Joint Commission requirements described earlier, this question can be used to initially screen a patient for pain, but a thorough pain assessment is required. Additionally, the patient’s comfort-function goal must be assessed. The comfort-function goal provides the basis for the patient’s individualized pain treatment plan and is used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

PQRSTU, OLDCARTES, and COLDSPA

The “PQRSTU,” “OLDCARTES,” or “COLDSPA” mnemonics are helpful in remembering a standardized set of questions used to gather additional data about a patient’s pain. See Figure 11.4 [1] for the questions associated with a “PQRSTU” assessment framework. While interviewing a patient about pain, use open-ended questions to allow the patient to elaborate on information that further improves your understanding of their concerns. If their answers do not seem to align, continue to ask focused questions to clarify information. For example, if a patient states that “the pain is tolerable” but also rates the pain as a “7” on a 0-10 pain scale, these answers do not align, and the nurse should continue to use follow-up questions using the PQRSTU framework. Upon further questioning the patient explains they rate the pain as a “7” in their knee when participating in physical therapy exercises, but currently feels the pain is tolerable while resting in bed. This additional information assists the nurse to customize interventions for effective treatment with reduced potential for overmedication with associated side effects.

Sample questions when using the PQRSTU assessment are included in Table 11.3a.

Table 11.3a. Sample PQRSTU Focused Questions for Pain

An alternative mnemonic to use when assessing pain is “OLDCARTES.”

- O nset: When did the pain start? How long does it last?

- L ocation: Where is the pain?

- D uration: How long has the pain been going on? How long does an episode last?

- C haracteristics: What does the pain feel like? Can the pain be described in terms such as stabbing, gnawing, sharp, dull, aching, piercing, or crushing?

- A ggravating factors: What brings on the pain? What makes the pain worse? Are there triggers such as movement, body position, activity, eating, or the environment?

- R adiating: Does the pain travel to another area or the body, or does it stay in one place?

- T reatment: What has been done to make the pain better and has it been helpful? Examples include medication, position change, rest, and application of hot or cold.

- E ffect: What is the effect of the pain on participating in your daily life activities?

- S everity: Rate your pain from 0 to 10.

A third mnemonic used is “COLDSPA.”

- C: Character

- L: Location

- D: Duration

- S: Severity

- A: Associated Factors

No matter which mnemonic is used to guide the assessment questions, the goal is to obtain comprehensive assessment data that allows the nurse to create a customized nursing care plan that effectively addresses the patient’s need for comfort.

Pain Scales

In addition to using the PQRSTU or OLDCARTES methods of investigating a patient’s chief complaint, there are several standardized pain rating scales used in nursing practice.

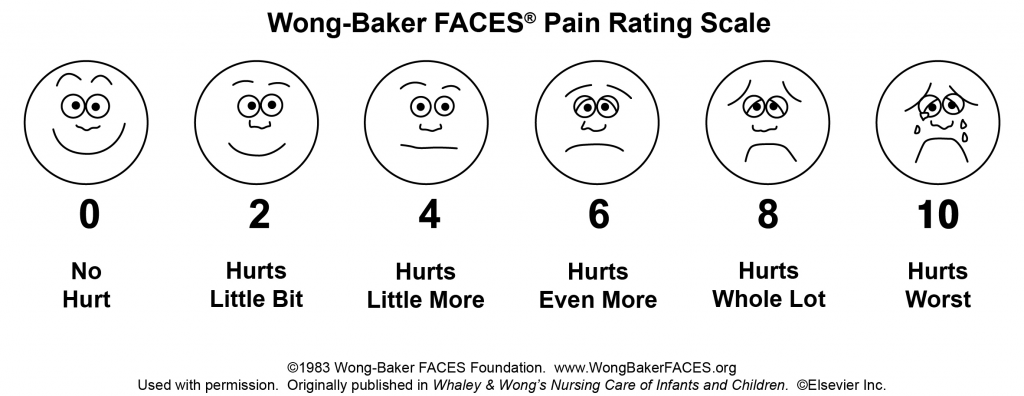

FACES Scale

The FACES scale is a visual tool for assessing pain with children and others who cannot quantify the severity of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10. See Figure 11.5 [2] for the FACES Pain Rating Scale. To use this scale, use the following evidence-based instructions. Explain to the patient that each face represents a person who has no pain (hurt), some pain, or a lot of pain. “Face 0 doesn’t hurt at all. Face 2 hurts just a little. Face 4 hurts a little more. Face 6 hurts even more. Face 8 hurts a whole lot. Face 10 hurts as much as you can imagine, although you don’t have to be crying to have this worst pain.” Ask the person to choose the face that best represents the pain they are feeling. [3]

FLACC Scale

The FLACC scale (i.e., the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale) is a measurement used to assess pain for children between the ages of 2 months and 7 years or individuals who are unable to verbally communicate their pain. The scale has five criteria, which are each assigned a score of 0, 1, or 2. The scale is scored in a range of 0–10 with “0” representing no pain. [4] See Table 11.3b for the FLACC scale.

Table 11.3b The FLACC Scale [5]

COMFORT Behavioral Scale

The COMFORT Behavioral Scale is a behavioral-observation tool validated for use in children of all ages who are receiving mechanical ventilation. Eight physiological and behavioral indicators are scored on a scale of 1 to 5 to assess pain and sedation. [6]

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale

The Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale is a simple, valid, and reliable instrument for assessing pain in noncommunicative patients with advanced dementia. See Table 11.3c for the items included on the scale. Each item is scored from 0-2, When totaled, the score can range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain).

Table 11.3c The PAINAD Scale [7]

Download the full PAINAD scale from the The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing. [8]

Comfort-Function Goals

Comfort-function goals encourage the patient to establish their level of comfort needed to achieve functional goals based on their current health status. For example, one patient may be comfortable ambulating after surgery and their pain level is 3 on a 0-to-10 pain intensity rating scale, whereas another patient desires a pain level of 0 on a 0-to-10 scale in order to feel comfortable ambulating. To properly establish a patient’s comfort-function goal, nurses must first describe the essential activities of recovery and explain the link between pain control and positive outcomes. [9]

If a patient’s pain score exceeds their comfort-function goal, nurses must implement an intervention and follow up within 1 hour to ensure that the intervention was successful. Using the previous example, if a patient had established a comfort-function goal of 3 to ambulate and the current pain rating was 6, the nurse would provide appropriate interventions, such as medication, application of cold packs, or relaxation measures. Documentation of the comfort-function goal, pain level, interventions, and follow-up are key to effective, individualized pain management. [10]

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St- Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Wong-Baker FACES Foundation. (2016). Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale. https://wongbakerfaces.org/ . Used with permission. ↵

- Merkel, S. I., Voepel-Lewis, T., Shayevitz, J. R., & Malviya, S. (1997). The FLACC: A behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatric Nursing, 23 (3). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9220806/ ↵

- Freund, D., & Bolick, B. (2019). CE: Assessing a Child's Pain. American Journal of Nursing. 119 (5), 34. https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Fulltext/2019/05000/CE__Assessing_a_Child_s_Pain.25.aspx ↵

- Warden V., Hurley A., & Volicer, L. (2003). Development and psychometric evaluation of the pain assessment in advanced dementia (PAINAD) scale. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 4 (1), 9-15. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JAM.0000043422.31640.F7 ↵

- The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, New York University, Rory Meyers School of Nursing. (n.d.). Assessment tools for best practices of care for older adults. https://hign.org/consultgeri-resources/try-this-series ↵

- Boswell, C., & Hall, M. (2017). Engaging the patient through comfort-function levels. Nursing 2017, 47 (10), 68-69. https://www.nursingcenter.com/journalarticle?Article_ID=4345712&Journal_ID=54016&Issue_ID=4345459 ↵

This is Clinical Skills content

Pain Assessment and Management

Learn more about Clinical Skills today! Standardize education and management competency among nurses, therapists and other health professionals to ensure knowledge and skills are current and reflect best practices and the latest clinical guidelines.

Pain Assessment and Management - CE/NCPD

Never use physiologic responses alone to determine pain therapy. A patient’s self-report is the gold standard.

Use only evidence-based pain assessment tools in the population in which the instrument has been tested.

Identify patients at high risk for adverse opioid-related outcomes (e.g., patients with sleep apnea, receiving continuous IV opioids, or on supplemental oxygen). undefined#ref5">5

Pain is a subjective experience for the patient and can be characterized in many ways: sharp or dull, burning or tingling, or generalized aching. Unrelieved pain has been associated with negative outcomes and physiologic alterations, such as increased peripheral vascular resistance and cardiac oxygen consumption, hypercoagulability, and compromised immune function. 8 Pain management is an important component of comprehensive patient care. 1

The use of opioid medication for pain management comes with risk. 1 Health care team members should be involved in pain assessment and management to identify patients at high risk for opioid dependence and to establish criteria for safe opioid prescribing. 4 Collaboration among health care team members helps achieve the best possible plan of care for pain relief.

The inability of a patient to communicate pain intensity (e.g., patients with cognitive impairment or an inability to communicate) is a barrier to effective pain control. The input of family members helps evaluate the patient’s response to medications and nonpharmacologic interventions but should not be the only assessment. Physiologic responses to acute pain (e.g., tachycardia, hypertension) have a short duration. With persistent pain, a patient does not typically exhibit such physiologic responses. A valid pain assessment method for patients with cognitive impairment or an inability to communicate should be used.

The patient should be actively involved in a pain management treatment plan. 4 Effectively managing a patient’s pain does not mean eliminating it. Pain management collaboration with the patient and family helps identify an acceptable intensity of pain that allows maximum patient functioning. Asking the patient baseline questions about the pain helps formulate pain-intensity goals to help the patient cope with the discomfort.

The nursing process offers a systematic method of pain management that results in improved pain relief for most patients. Using this process, the nurse recognizes distinct differences in patient perceptions and responses to pain. Nonpharmacologic complimentary modalities for pain relief should be incorporated into the patient’s care. 1 An individualized plan of care that stabilizes the patient’s pain at an acceptable intensity is the goal of pain assessment and management.

See Supplies tab at the top of the page.

- Provide developmentally and culturally appropriate education based on the desire for knowledge, readiness to learn, and overall neurologic and psychosocial state.

- Explain to the patient and family that pain control is the patient’s right.

- Review the patient’s and family’s understanding of the pain-intensity scale selected to rate the patient’s pain.

- Explain the steps to be taken to minimize pain stimuli.

- Discuss the patient’s goal for pain management.

- Encourage questions and answer them as they arise.

ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

- Perform hand hygiene before patient contact. Don appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) based on the patient’s need for isolation precautions or the risk of exposure to bodily fluids.

- Introduce yourself to the patient.

- Verify the correct patient using two identifiers.

- Invasive procedures

- Inability to communicate

- Cognitive impairment

- Advanced age

Rationale: In some cultures, expressing pain is unacceptable; the nurse must assess nonverbal and physiologic signs of pain.

- Nociceptive pain (resulting from damage to tissue)

- Neuropathic pain (resulting from a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory nervous system)

- Cancer pain (resulting from malignant disease)

- Psychogenic pain (without visible signs of disease)

- Chronic or idiopathic pain (longer duration than expected for healing or no identifiable cause) 3

Rationale: Medication strategies differ based on the type of pain. For example, immediate-release opioids are more appropriate for acute pain, whereas chronic pain requires a long-acting, sustained-release opioid with breakthrough pain medication.

- Acute pain is sudden and usually sharp. It lasts for a few minutes and up to weeks or even months (e.g., postoperative pain or childbirth pain).

- Chronic pain persists after healing has occurred (e.g., low back pain, arthritis pain, neuropathic pain) and usually lasts more than 6 months. 3 Chronic pain is often described as burning or radiating.

- Assess the patient’s response to previous pharmacologic interventions, especially the ability to function (e.g., sleeping, eating, and other activities of daily living [ADL]).

- Determine the patient’s previous responses to analgesics (e.g., itching and nausea with morphine).

- Inspection (discoloration, swelling, drainage)

- Palpation (change in temperature, areas of altered sensation, painful areas, areas that trigger pain, areas that reduce pain)

- Range of motion of involved joints, if applicable

When examining the abdomen, auscultate first; then inspect and palpate.

- Moaning, crying, whimpering, vocalizations (e.g., “Stop, stop!”)

- Decreased activity

- Facial expressions (e.g., grimace, clenched teeth)

- Change in usual behavior

- Abnormal gait

- Irritability

- Guarding of a body part

- Increased blood glucose level

- Diaphoresis

- Change in mental status (e.g., confusion)

- Decreased gastrointestinal motility, nausea, vomiting

- Muscle tension, restlessness, exhaustion

- Insomnia, anorexia, fatigue

- Depression, hopelessness, anger, fear, social withdrawal, powerlessness, stoicism

Factors other than pain may influence patient behavior and cause distress.

- P rovocative or P alliative factors (e.g., “What makes your pain better or worse?”)

- Q uality (open-ended questions, e.g., “What does your pain feel like?”)

- R egion and R adiation (e.g., “Show me where your pain is.”)

Rationale: Pain intensity often changes with movement.

- T iming: Ask the patient if the pain is constant, intermittent, continuous, or a combination; also, ask if the pain increases during specific times of the day, with particular activities, or in specific locations.

- Ask the patient baseline questions to help establish pain-intensity goals, such as “How is the pain affecting you (U) with regard to ADLs, work, relationships, and enjoyment of life?”

- Assess the cultural considerations, background, and attitudes that may affect the patient’s perception and treatment of pain.

- Identify the patient’s preferences for supplemental nonpharmacologic pain management modalities.

Preparation

Rationale: Temperature extremes alter a patient’s responses to pain.

Rationale: Bright or very dim lighting aggravates pain sensation.

Rationale: Loud or irritating sounds aggravate pain.

Rationale: Fatigue accentuates the perception of pain.

Rationale: Privacy reduces stimuli that increase pain.

- Perform hand hygiene. Don appropriate PPE based on the patient’s need for isolation precautions or the risk of exposure to bodily fluids.

- Explain the procedure and ensure that the patient agrees to treatment.

Rationale: Removing triggers reduces stimulation of pain and pressure receptors and maximizes a patient’s response to pain-relieving interventions.

Rationale: Turning and repositioning reduce stimulation of pain and pressure receptors.

Rationale: Smooth linens reduce pressure and irritation to the skin.

Rationale: Constrictive bandages or devices encircling an extremity may restrict circulation.

- Reposition underlying tubes or equipment.

Rationale: Splinting immobilizes the painful area.

- Assist the patient in placing the hands firmly over the area of discomfort.

- Attempt nonpharmacologic or complementary interventions before administering analgesics, as appropriate. These interventions include using aromatherapy, distraction, massage, and music of the patient’s choice.

- If nonpharmacologic interventions are unsuccessful and if analgesics are ineffective, or none have been ordered, consult the practitioner regarding an order for analgesics.

- Administer analgesics as ordered.

- Reassess the patient’s pain status, allowing for sufficient onset of action per medication, route, and the patient’s condition. Assess the patient for adverse effects of the medication (e.g., respiratory depression).

Rationale: Preemptive action prevents or minimizes unpleasant problems. When an adverse effect is common to the patient, the patient should not have to wait to ask for treatment.

- Discard supplies, remove PPE, and perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure in the patient’s record.

MONITORING AND CARE

Use the same pain-intensity scale that was used before implementing pain interventions.

- Compare the patient’s ability to function and perform ADLs before and after pain interventions.

- Observe the patient’s nonverbal behaviors, including facial expressions, body movements, restlessness, behavioral changes, and speaking out.

Rationale: Adverse effects of analgesics may be controlled by reducing the dose, increasing the time intervals, or administering other medications (e.g., stimulant laxative for opioid-induced constipation).

- If medications or nonpharmaceutical interventions are ineffective, contact the practitioner for further orders.

- Assess, treat, and reassess pain.

EXPECTED OUTCOMES

- Patient expresses full or partial pain relief.

- Patient states that pain-intensity goal is achieved.

- Patient displays nonverbal behaviors that reflect a reduction in pain (e.g., relaxed face and absence of squinting).

- Patient’s sleep, nutrition, physical activity, and interpersonal relationships improve.

UNEXPECTED OUTCOMES

- Patient describes continued pain that exceeds pain-intensity goal, worsening pain, or pain in a different location.

- Patient displays nonverbal behavior reflecting pain.

- Patient experiences an unexpected reaction to the medication.

DOCUMENTATION

- Pain-intensity scale used

- Pain assessment before and after intervention

- Character of pain before intervention, therapies used, and patient’s response

- Inadequate pain relief (not reaching goal)

- Reduction in patient’s functioning

- Adverse effects from pain interventions (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic)

- Unexpected outcomes and related interventions

PEDIATRIC CONSIDERATIONS

- Although validity and reliability scores of pain rating scales generally increase with a patient’s age, some rating scales can be used with a child as young as 3 years old. 2 , 6

- Some children are reluctant to report pain because they have misconceptions about the cause of it or they fear the consequences (e.g., another painful procedure or an injection).

- Infants and children respond to pain differently than adults, and behaviors vary depending on developmental level. 7 Examples of pain-related behaviors are crying, thrashing, disturbed sleep, refusal to eat or play, withdrawal, being unusually quiet, and sucking or rocking.

- Parents are a helpful source of information when assessing a child’s pain and planning pain-relief therapies. Most parents know how their child exhibits pain and which pain-relief interventions have been successful.

- Many pediatric medication dosages are based on the child’s weight. Ensure that a recent, accurate weight has been obtained.

OLDER ADULT CONSIDERATIONS

- Older adults may have vision or hearing problems that complicate pain assessment. Look for pain behaviors to indicate the location and intensity of pain. 2

- Explaining the selected pain assessment scale to some older adults may require more time.

- Pain is not a natural part of aging, although older adults are at risk of experiencing more pain-producing conditions.

- Nonverbal older adults experiencing pain typically receive fewer analgesics than those who are able to report their pain. Perform a thorough pain assessment and evaluation of the patient’s response.

- American Nurses Association (ANA). (2018). The ethical responsibility to manage pain and the suffering it causes. Retrieved November 8, 2023, from https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/official-position-statements/id/the-ethical-responsibility-to-manage-pain-and-the-suffering-it-causes/

- Ball, J.W. and others (Eds.). (2023). Chapter 6: Vital signs and pain assessment. In Seidel’s guide to physical examination: An interprofessional approach (10th ed., pp. 79-92). St. Louis: Elsevier.

- Gélinas, C. (2022). Chapter 8: Pain and pain management. In L.D. Urden, K.M. Stacy, M.E. Lough (Eds.), Critical care nursing: Diagnosis and management (9th ed., pp. 116-139). St. Louis: Elsevier.

- Joint Commission, The. (2017). Joint Commission enhances pain assessment and management requirements for accredited hospitals. Perspectives, 37 (7), 1, 3-4. (Level VII)

- Joint Commission, The. (2017). Pain assessment and management standards for hospitals. R3 Report: Requirement, Rationale, Reference, 11, 1-7. Retrieved November 8, 2023, from https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/R3_Report_Issue_11_Pain_Assessment_8_25_17_FINAL.pdf (Level VII)

- Lewis, C.A. (2022). Chapter 39: The pediatric patient. In L.D. Urden, K.M. Stacy, M.E. Lough (Eds.), Critical care nursing: Diagnosis and management (9th ed., pp. 974-996). St. Louis: Elsevier.

- Martin, S.D. and others. (2019). Chapter 5: Pain assessment and management in children. In M.J. Hockenberry, D. Wilson, C.C. Rodgers (Eds.), Wong’s nursing care of infants and children (11th ed., pp. 137-168). St. Louis: Elsevier.

- Miner, J.R., Burton, J.H. (2023). Chapter 6: Pain management. In R.M. Walls and others (Eds.), Rosen’s emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice (10th ed., pp. 62-79). Philadelphia: Elsevier.

ADDITIONAL READINGS

Tick, H. and others. (2018). Evidence-based nonpharmacologic strategies for comprehensive pain care: The Consortium Pain Task Force white paper. Explore, 14 (3), 177-211. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2018.02.001

Adapted from Perry, A.G. and others (Eds.). (2022). Clinical nursing skills & techniques (10th ed.). St. Louis: Elsevier.

Elsevier Skills Levels of Evidence

- Level I - Systematic review of all relevant randomized controlled trials

- Level II - At least one well-designed randomized controlled trial

- Level III - Well-designed controlled trials without randomization

- Level IV - Well-designed case-controlled or cohort studies

- Level V - Descriptive or qualitative studies

- Level VI - Single descriptive or qualitative study

- Level VII - Authority opinion or expert committee reports

Clinical Review: Suzanne M. Casey, MSN-Ed, RN Published: December 2023

- About Elsevier

- Accessibility Policy

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookie settings

Cookies are used by this site. To decline or learn more, visit our cookie notice .

Copyright © 2024 Elsevier, its licensors, and contributors. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Abbey J, Piller N, De Bellis A The Abbey pain scale: a 1-minute numerical indicator for people with end-stage dementia. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2004; 10:(1)6-13 https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.1.12013

Boore J, Cook N, Shepherd A. Essentials of anatomy and physiology for nursing practice.Los Angeles: Sage; 2016

Colvin LA, Carty S. Neuropathic pain. In: Colvin LA, Fallon M (eds). Chichester: BMJ Books/Wiley; 2012

Cullen M, MacPherson F. Complementary and alternative strategies. In: Colvin LA, Fallon M (eds). Chichester: BMJ Books/Wiley; 2012

Cunningham S. Pain assessment and management. In: Moore T, Cunningham S (eds). Abingdon: Routledge; 2017

Flasar CE, Perry AG. Pain assessment and basic comfort measures, 8th edn. In: Perry AG, Potter PA, Ostendorf WR (eds). London: Mosby/Elsevier; 2014

Johnson MI. The role of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation TENS on pain management. In: Colvin LA, Fallon M (eds). Chichester: BMJ Books/Wiley; 2012

Kettyle A. Pain management, 1st edn. In: Delves-Yates C (ed). London: Sage; 2015

Laws P, Rudall N. Assessment and monitoring of analgesia, sedation, delirium and neuromuscular blockade levels and care. In: Mallet J, Albarran JW, Richardson A (eds). Chichester: Wiley; 2013

Mears J. Pain management. In: Dutton H, Finch J (eds). Chichester: Wiley; 2018

Melzack R. The McGill pain questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975; 1:(3)277-299

Smith MT, Muralidharan A. Pain pharmacology and the pharmacological management of pain, 2nd edn. In: Van Griensven H, Strong J, Unruh AM (eds). London: Elsevier; 2014

World Health Organization. WHO's cancer pain ladder for adults. 2019. http://tinyurl.com/y4u2ghok (accessed 28 March 2019)

Adult pain assessment and management

Claire Ford

Lecturer, Adult Nursing, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, explain how to reduce the risk of contamination

View articles · Email Claire

Claire Ford, Lecturer, Adult Nursing, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne ([email protected]) outlines the skills and tools health professionals use to help patients manage pain

For health professionals, one of the most common patient problems they will encounter is pain. Although this is universally experienced, effective assessment and management is sometimes difficult to achieve, as pain is also extremely complex. Therefore, when a patient states they are in pain it is every health professional's duty to listen to what they say, believe that pain is what they say it is, observe for supporting information using appropriate and varied assessment approaches, and act as soon as possible using suitable management strategies.

The holistic assessment and management of pain is important, as pain involves the mind as well as the body, and is activated by a variety of stimuli, including biological, physical, and psychological ( Boore et al, 2016 ). For some patients, the pain they experience can be short-lived and easy to treat, but for others, it can cause significant issues in relation to their overall health and wellbeing ( Flasar and Perry, 2014 ).

Mismanaged pain can affect an individual's mobility, sleep pattern, nutritional and hydration status and can increase their risk of developing depression or becoming socially withdrawn ( Mears, 2018 ). As nurses are the frontline force in healthcare settings, they play a vital role in the treatment of individuals in pain. This article examines and explores some of the holistic nursing assessment and management strategies that can be used by health professionals.

Classifications of pain

Before diving into the assessment process, it is necessary to have a general understanding of the various types of pain that can be experienced, as well as how these are manifested. This understanding will ultimately help to inform management decisions—it is the first step in the assessment process ( Boore et al, 2016 ).

There are several classifications of pain (see Table 1 ); some overlap and patients may present with one or more. Pain can be:

- Acute: pain that is of short duration (less than 3 months) and is reversible

- Chronic: pain that is persistent and has been experienced for more than 3 months

- Nociceptive: pain resulting from stimulation of pain receptors by heat, cold, stretching, vibration or chemicals

- Neuropathic: pain related to sensory abnormalities that can result from damage to the nerves (nerve infection) or neurological dysfunction (a disease in the somatosensory nervous system)

- Inflammation: stimulation of nociceptive processes by chemicals released as part of the inflammatory process

- Somatic: nociceptive processes activated in skin, bones, joints, connective tissues and muscles

- Visceral: nociceptive processes activated in organs (eg stomach, kidneys, gallbladder)

- Referred: pain that is felt a distance from the site of origin. ( Colvin and Carty, 2012 ; Laws and Rudall, 2013 ; Kettyle, 2015 ; Boore et al, 2016 ; Cunningham, 2017 ; Mears, 2018 ).

Individuals react to pain in varying ways; for some, pain is seen as something that should be endured, while for others it can be a debilitating problem, which is impeding their ability to function. Therefore, in order to develop an effective and individually tailored holistic management plan, it is important to understand how the pain is uniquely affecting the individual, from a biopsychosocial perspective ( Flasar and Perry, 2014 ).

To do this, health professionals use a range of tools, such as the skills of observation (the art of noticing), questioning techniques, active listening, measurement and interpretation. No one skill is superior; rather, it is the culmination of information gathered via the various methods that enables a health professional to determine if a patient is in pain, and how this pain is affecting them physically, psychologically, socially, and culturally ( Cunningham, 2017 ) ( Table 2 ).

One of the first skills that can be used is to visually observe the patient, and examine body language, facial expressions, and behaviours, as these provide information about how a person is feeling. For example, an individual in pain may be quiet and withdrawn or very vocal, angry, and irritable. They may display facial grimacing and teeth clenching or exhibit negative body language, guarding and an altered gait.

However, there may be times when an individual may not be able to show behavioural signs of pain, such as when a patient is unconscious. Therefore, physiological response to noxious stimuli can be observed through the measurement of vital signs, such as hypertension, tachycardia, and tachypnoea. Although these observations are routinely used within perioperative and critical care areas, these signs can be present in the absence of pain; consequently, these must be used in conjunction with other assessment strategies ( Laws and Rudall, 2013 ).

Assessment tools

Although vital observations and behavioural manifestations may indicate that a patient is in pain, questioning, measurement and interpretation skills will assist with determining the intensity, severity, and effect of the pain on the patient's wellbeing and quality of life. This process can be aided with the use of specifically designed tools, which act as prompts for health professionals and facilitate the assessment of one or more dimensions.

Unidimensional tools

A visual analogue scale (VAS), numerical rating scale (NRS), or verbal rating scale (VRS) can be quick, easy to use, regularly repeated and do not require complex language. These are limited in terms of the information gained, as examining one specific aspect is not sufficient for adequate and holistic pain management ( Mears, 2018 ). However, for individuals who are unable to communicate or where language barriers exist, unidimensional tools, such as the Wong-Baker FACES tool can be very useful ( Kettyle, 2015 ). The Wong-Baker FACES tool (https://wongbakerfaces.org/), which was originally created for children, has been successfully integrated into the care of older people (with or without cognitive impairment) and is beneficial in facilitating an individual's ability to communicate if they are experiencing pain.

Multidimensional tools

These ask for greater information and measure the quality of pain via affective, evaluative and sensory means. The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) is one example ( Melzack, 1975 ). This long-established tool is often used to assess individuals who are experiencing chronic pain. However, due to its higher levels of complexity health professionals can sometimes find this tool more difficult to use, especially if unfamiliar with it. The Abbey pain scale ( Abbey et al, 2004 ) is another multidimensional tool that has proven to be beneficial for assessing pain in older adults who are unable to articulate their needs.

OPQRST and SOCRATES are just two examples of mnemonic aids, which can be useful and require no equipment as they use mental assessment processes only. OPQRST stands for onset, provokes, quality, radiates, severity and time. SOCRATES stands for site, onset, character, radiates, associations, timing, exacerbating factors and severity.

However, regardless of which tool or mnemonic is used, because pain presentations are often unique pain assessment will not be successful if the health professional fails to ascertain and interpret the signs and symptoms, uses the tools inappropriately, and does not apply a person-centred approach to the overall assessment process, ie uses the wrong tool for the wrong patient.

Management strategies

The primary goal for all patients is to pre-empt and prevent pain from occurring in the first instance; however, if pain cannot be avoided, optimal analgesic management is vital.

The word analgesia, ‘to be without feeling of pain’, is derived from the Greek language, and in terms of pain management can relate to medication and alternative interventions ( Laws and Rudall, 2013 ). Hence, pain management plans should incorporate a multi-modal approach in order to successfully and holistically treat patients' pain ( Flasar and Perry, 2014 ). Boore et al (2016) argued that this is an effective way to manage pain, but stressed that the decisions about which management strategies to use, also need to take into consideration the context of the clinical situation, the patient's level of acuity, the environment and physical space, and the availability of resources.

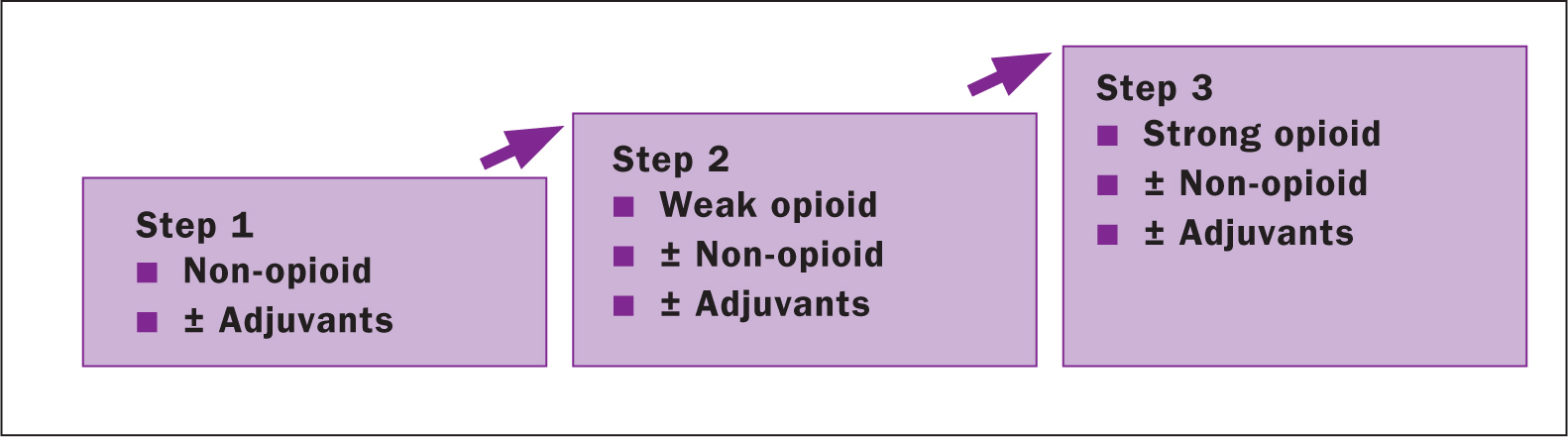

Pharmacological

One very effective strategy that health professionals have within their management arsenal is the use of pharmacological treatments. The choice of treatment depends on whether the pain is nociceptive, neuropathic, inflammatory or of mixed origin. There are three main categories: opioids, non-opioids/non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, and adjuvants/co-analgesics ( Table 3 ). The most efficient pharmacological regime, for moderate to severe pain (ie cancer-related pain) often incorporates a combined approach, by administrating a specific drug in conjunction with adjuvants or co-analgesics ( Figure 1 ).

Non-pharmacological

Pharmacological treatments are not the only strategy at health professionals' disposal, and true holistic management cannot be achieved without the incorporation of other non-pharmacological therapies. Some of these interventions are long-standing, are ingrained in some traditional medical practices and, when used correctly, can enhance patients' feelings of empowerment and involvement ( Flasar and Perry, 2014 ). However, due to limited resources, funding, space, time, knowledge of use, and personal beliefs, some therapies are not fully used or embraced ( Cullen and MacPherson, 2012 ).

These can be placed into three main groups ( Table 4 ), and the choice of which to use will depend on patients' preferences and existing coping mechanisms. The following strategies have been highlighted as they align with the fundamental core values of care and compassion, and require very little in terms of resources or time.

- Distraction: this can take various forms, such as talking to the patient about their specific hobbies. This basic skill often requires no equipment, can be done anywhere and is a useful way of taking the patient's mind off their pain

- Imagery/meditation: this management technique takes distraction therapy one step further by using a more structured approach

- Therapeutic touch and massage: for centuries, the therapeutic placing of hands has proven to be a useful skill, and has beneficial physiological (stimulation of A-beta fibres, which restrict pain pathways) and psychological properties ( Kettyle, 2015 ).

- Environment: sound, lighting and the temperature of the patient's immediate environment have been shown to heighten or reduce perceptions of pain

- Body positioning and comfort: this can be used to help patients cope with the pain levels they are experiencing and may reduce the pain associated with nociceptive and inflammatory pain signals

- Thermoregulation: for some types of pain, it has been shown that the use of heat or cold packs can help reduce pain experiences. However, care needs to be taken if these treatments are to be used on postoperative sites and areas with skin-related contraindications

- Electrostimulation: this technique is non-invasive and uses pulsed electrical currents to stimulate A-beta fibres, which inhibit the transmission of nociceptive signals in the pain pathway ( Johnson, 2012 ).

Successful pain assessment and management can only be achieved if health professionals adopt a holistic and multimodal approach, incorporating the use of person-centred assessment processes, compassionate communication and a variety of management strategies, chosen in partnership with the patient.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

- Have a basic understanding of some of the classifications of pain

- Improve awareness of the skills required to assess and manage an individual's pain

- Explore some of the tools used to assist with the assessment of pain

- Understand some of the strategies used to manage pain

- Examine some of the barriers to effective pain assessment and management

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.3 Pain Assessment Methods

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Asking a patient to rate the severity of their pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with “0” being no pain and “10” being the worst pain imaginable is a common question used to screen patients for pain. However, according to The Joint Commission requirements described earlier, this question can be used to initially screen a patient for pain, but a thorough pain assessment is required. Additionally, the patient’s comfort-function goal must be assessed. The comfort-function goal provides the basis for the patient’s individualized pain treatment plan and is used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

PQRSTU, OLDCARTES, and COLDSPA

The “PQRSTU,” “OLDCARTES,” or “COLDSPA” mnemonics are helpful in remembering a standardized set of questions used to gather additional data about a patient’s pain. See Figure 11.4 [1] for the questions associated with a “PQRSTU” assessment framework. While interviewing a patient about pain, use open-ended questions to allow the patient to elaborate on information that further improves your understanding of their concerns. If their answers do not seem to align, continue to ask focused questions to clarify information. For example, if a patient states that “the pain is tolerable” but also rates the pain as a “7” on a 0-10 pain scale, these answers do not align, and the nurse should continue to use follow-up questions using the PQRSTU framework. Upon further questioning the patient explains they rate the pain as a “7” in their knee when participating in physical therapy exercises, but currently feels the pain is tolerable while resting in bed. This additional information assists the nurse to customize interventions for effective treatment with reduced potential for overmedication with associated side effects.

Sample questions when using the PQRSTU assessment are included in Table 11.3a.

Table 11.3a. Sample PQRSTU Focused Questions for Pain

An alternative mnemonic to use when assessing pain is “OLDCARTES.”

- O nset: When did the pain start? How long does it last?

- L ocation: Where is the pain?

- D uration: How long has the pain been going on? How long does an episode last?

- C haracteristics: What does the pain feel like? Can the pain be described in terms such as stabbing, gnawing, sharp, dull, aching, piercing, or crushing?

- A ggravating factors: What brings on the pain? What makes the pain worse? Are there triggers such as movement, body position, activity, eating, or the environment?

- R adiating: Does the pain travel to another area or the body, or does it stay in one place?

- T reatment: What has been done to make the pain better and has it been helpful? Examples include medication, position change, rest, and application of hot or cold.

- E ffect: What is the effect of the pain on participating in your daily life activities?

- S everity: Rate your pain from 0 to 10.

A third mnemonic used is “COLDSPA.”

- C: Character

- L: Location

- D: Duration

- S: Severity

- A: Associated Factors

No matter which mnemonic is used to guide the assessment questions, the goal is to obtain comprehensive assessment data that allows the nurse to create a customized nursing care plan that effectively addresses the patient’s need for comfort.

Pain Scales

In addition to using the PQRSTU or OLDCARTES methods of investigating a patient’s chief complaint, there are several standardized pain rating scales used in nursing practice.

FACES Scale

The FACES scale is a visual tool for assessing pain with children and others who cannot quantify the severity of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10. See Figure 11.5 [2] for the FACES Pain Rating Scale. To use this scale, use the following evidence-based instructions. Explain to the patient that each face represents a person who has no pain (hurt), some pain, or a lot of pain. “Face 0 doesn’t hurt at all. Face 2 hurts just a little. Face 4 hurts a little more. Face 6 hurts even more. Face 8 hurts a whole lot. Face 10 hurts as much as you can imagine, although you don’t have to be crying to have this worst pain.” Ask the person to choose the face that best represents the pain they are feeling. [3]

FLACC Scale

The FLACC scale (i.e., the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale) is a measurement used to assess pain for children between the ages of 2 months and 7 years or individuals who are unable to verbally communicate their pain. The scale has five criteria, which are each assigned a score of 0, 1, or 2. The scale is scored in a range of 0–10 with “0” representing no pain. [4] See Table 11.3b for the FLACC scale.

Table 11.3b The FLACC Scale [5]

COMFORT Behavioral Scale

The COMFORT Behavioral Scale is a behavioral-observation tool validated for use in children of all ages who are receiving mechanical ventilation. Eight physiological and behavioral indicators are scored on a scale of 1 to 5 to assess pain and sedation. [6]

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale

The Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale is a simple, valid, and reliable instrument for assessing pain in noncommunicative patients with advanced dementia. See Table 11.3c for the items included on the scale. Each item is scored from 0-2, When totaled, the score can range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain).

Table 11.3c The PAINAD Scale [7]

Comfort-Function Goals

Comfort-function goals encourage the patient to establish their level of comfort needed to achieve functional goals based on their current health status. For example, one patient may be comfortable ambulating after surgery and their pain level is 3 on a 0-to-10 pain intensity rating scale, whereas another patient desires a pain level of 0 on a 0-to-10 scale in order to feel comfortable ambulating. To properly establish a patient’s comfort-function goal, nurses must first describe the essential activities of recovery and explain the link between pain control and positive outcomes. [9]

If a patient’s pain score exceeds their comfort-function goal, nurses must implement an intervention and follow up within 1 hour to ensure that the intervention was successful. Using the previous example, if a patient had established a comfort-function goal of 3 to ambulate and the current pain rating was 6, the nurse would provide appropriate interventions, such as medication, application of cold packs, or relaxation measures. Documentation of the comfort-function goal, pain level, interventions, and follow-up are key to effective, individualized pain management. [10]

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St- Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Wong-Baker FACES Foundation. (2016). Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale. https://wongbakerfaces.org/ . Used with permission. ↵

- Merkel, S. I., Voepel-Lewis, T., Shayevitz, J. R., & Malviya, S. (1997). The FLACC: A behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatric Nursing, 23 (3). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9220806/ ↵

- Freund, D., & Bolick, B. (2019). CE: Assessing a Child's Pain. American Journal of Nursing. 119 (5), 34. https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Fulltext/2019/05000/CE__Assessing_a_Child_s_Pain.25.aspx ↵

- Warden V., Hurley A., & Volicer, L. (2003). Development and psychometric evaluation of the pain assessment in advanced dementia (PAINAD) scale. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 4 (1), 9-15. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JAM.0000043422.31640.F7 ↵

- The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, New York University, Rory Meyers School of Nursing. (n.d.). Assessment tools for best practices of care for older adults. https://hign.org/consultgeri-resources/try-this-series ↵

- Boswell, C., & Hall, M. (2017). Engaging the patient through comfort-function levels. Nursing 2017, 47 (10), 68-69. https://www.nursingcenter.com/journalarticle?Article_ID=4345712&Journal_ID=54016&Issue_ID=4345459 ↵

Nursing Fundamentals Copyright © by Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Pain Scales: Types of Scales and Using Them to Explain Pain

11 Common Pain Scales Doctors Use to Assess Pain

Pain scales are used by healthcare providers to improve communication and understanding about the pain you may be experiencing. Pain is felt differently from one person to the next ranging from mild to severe and varying in type. Having a means of measuring your pain helps with:

- Diagnosing what may be the cause of your pain

- Tracking how your condition progresses

- Determining if treatment is working for you

Several types of pain scales are in use for acute, chronic, and neuropathic pain. Whether your pain comes on suddenly ( acute ), persists for several months ( chronic ), or is caused by nerve damage ( neuropathic ), the 11 common scales explored in this article can be tools that help you move through it.

Types of Pain Scales

Healthcare providers have at least 11 types of pain scales to choose from. They generally fall into one of three categories:

- Numerical rating scales (NRS) : Uses numbers to rate pain

- Visual analog scales (VAS) : Asks you to select a picture that best matches your pain level

- Categorical scales : Primarily uses words, possibly along with numbers, colors, or location(s) on the body

The scales may provide quantitative measurements, qualitative measurements, or both.

Quantitative scales answer the question, "How bad is your pain?" They're helpful for gauging your response to treatment over time.

Qualitative pain scales answer the question, "What does it feel like?" They can give your healthcare provider ideas about the cause of your pain , whether it's associated with any medical problems you have, or whether it's caused by the treatment itself.

No one particular pain scale is considered ideal or better than the others for every situation. Some of these tools are best suited for people of certain ages. Others are more useful for people who are highly involved in their own health care.

Numerical Rating Pain Scale

NIH / Warren Grant Magnusen Clinical Center

The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) is designed for anyone over age 9. It is one of the most commonly used pain scales in health care.

To use it, you just say the number that best matches the level of pain you are feeling; you can also place a mark on the scale itself.

Zero means you have no pain, while 10 represents the most intense pain possible.

Wong-Baker Faces Pain Scale

The Wong-Baker FACES Pain Scale combines pictures and numbers for pain ratings. It can be used in adults and children over age 3.

Six faces depict different expressions, ranging from happy to extremely upset. Each is assigned a numerical rating between 0 (smiling) and 10 (crying).

To use it, you can point to the picture that best represents the degree and intensity of your pain.

FLACC Pain Scale

The FLACC Pain Scale is based on observations made by a healthcare provider. Originally created to evaluate young children, it can be used for anyone who cannot communicate.

FLACC stands for:

- Facial expression

- Leg tension or relaxation

- Activity (still or squirming with pain)

- Consolability (whether you can be comforted)

Zero to two points are assigned for each of the five categories. Then the overall score is tallied. Scores are interpreted as follows:

- 0 : Relaxed and comfortable

- 1 to 3 : Mild discomfort

- 4 to 6 : Moderate pain

- 7 to 10 : Severe discomfort/pain

By recording the FLACC score on a regular basis, healthcare providers can gain some sense of whether someone's pain is increasing, decreasing, or staying the same.

CRIES Pain Scale

The CRIES Pain Scale assesses:

- Oxygenation

- Vital signs

- Sleeplessness

It's often used for babies 6 months and younger. It's widely used in neonatal intensive care units (NICU).

This assessment tool is based on a healthcare provider's observations and objective measurements. In each category:

- A rating of 0 means you're showing no signs of pain.

- A rating of 2 means you're showing signs of extreme pain.

COMFORT Pain Scale

The COMFORT Scale is another pain scale designed for people who can't describe or rate their pain, such as:

- Adults with cognitive impairments

- Adults who are temporarily impaired by medication or illness

- People who are sedated in an intensive care unit (ICU) or operating room

The COMFORT Scale provides a pain rating between nine and 45 based on nine different parameters. Each is rated from 1 to 5:

- Alertness : 1 for deep sleep, 2 for light sleep, 3 for drowsiness, 4 for alertness, and 5 for high alertness

- Calmness : 1 for complete calmness, higher ratings for increased anxiety and agitation

- Respiratory distress : How much your breathing indicates pain, with higher ratings for agitated breathing

- Crying: 1 for no crying, higher scores for moaning, sobbing, or screaming

- Physical movement : 0 for no movement (a sign of less pain), 1 or 2 for some movement, and higher scores for vigorous movements (e.g., thrashing in pain)

- Muscle tone : A score of 3 for normal, lower scores for diminished muscle tone, and higher scores for rigid muscles

- Facial tension : 1 for a completely normal, relaxed face, and higher ratings for signs of strain

- Blood pressure and heart rate : Rated according to your baseline; 1 means they're below baseline (abnormally low), 2 is baseline, and higher scores are for elevated or abnormally high levels

McGill Pain Questionnaire

The McGill Pain Questionnaire, also known as the McGill Pain Index, consists of 78 words that describe pain. You rate your own pain by marking the words that best match your feelings.

Some examples of the words used are:

Once you've made your selections, the provider figures out a numerical score with a maximum rating of 78 based on how many words you marked.

This pain scale is helpful for adults and children who can read.

Color Analog Pain Scale

BSIP / Getty Images

The Color Analog Scale (CAS) uses colors to represent different levels of pain on a pain scale:

- Red : Severe pain

- Yellow : Moderate pain

- Green : Comfortable

The colors are usually positioned in a line with corresponding numbers or words that describe your pain.

The Color Analog Scale is often used for children and is considered reliable.

Mankoski Pain Scale

The Mankoski Pain Scale uses numbers and specific descriptions of pain to ensure your healthcare provider understands your pain.

Descriptions are detailed. They include phrases such as:

- Very minor annoyance

- Occasional minor twinges

- Cannot be ignored for more than 30 minutes

After reading the descriptions, you tell the provider which number best fits your pain level.

Brief Pain Inventory

RamiNaif / Researchgate

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) is a worksheet made up of 15 questions.

You're asked to numerically rate the effect of your pain in categories such as:

- How you relate with other people

- How well you can walk

- How you've slept over the last 24 hours

This pain scale captures more nuance in terms of how your pain is affecting your day-to-day life.

Descriptor Differential Scale of Pain Intensity

Ratologydisabled

This pain scale has 12 lines, each of which has a descriptor—such as faint, strong, intense, and very intense—placed in the middle of it.

Each line has a minus sign at the start and a plus sign at the end.

- First, you find the line with the descriptor that best matches your pain.

- For less intense pain, you mark somewhere on the minus side.

- For more intense pain, you mark someone on the plus side.

Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale

U.S. Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense in 2021 announced it was using a new pain scale called the Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS).

According to a news release , it's the response to dissatisfaction with other pain scales from both healthcare providers and patients. Rather than a simple scale, it includes:

- Faces : Expressions range from smiling to highly distressed

- Colors : Green for no pain, then moving through the spectrum to red for the worst possible pain

- Numbers : 0 for no pain, 10 for the worst possible pain

- Descriptors : These include "hardly notice pain," "hard to ignore, avoid usual activities," and "can't bear the pain, unable to do anything"

Combining aspects of many other pain scales may give your healthcare provider more information to work from.

Pain scales can help healthcare providers determine how much pain you're in and its impact on you. They can also help define your pain in mutually understood terms.

The medical community uses several kinds of pain scales. Some use pictures or colors, others use numbers or words, and some use combinations of these.

A provider can choose which scale to use based on your ability to read or communicate and what they want to learn.

Some doctors regularly use a pain scale. Some hospital rooms even have them posted on their walls.

If you're not asked to use a pain scale and are having a hard time clearly communicating with a healthcare provider, ask for one. They're a useful tool for improving diagnosis and treatment.

Boonstra AM, Stewart RE, Köke AJ, et al. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the numeric rating scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: variability and influence of sex and catastrophizing . Front Psychol . 2016;7:1466. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01466

Wong-Baker Faces Foundation. Pain Rating Scale .

Crellin DJ, Harrison D, Santamaria N, Huque H, Babl FE. The psychometric properties of the FLACC scale used to assess procedural pain . J Pain . 2018;19(8):862-872. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2018.02.013

New York Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Pain Scales Assessment .

Boerlage AA, Ista E, Duivenvoorden HJ, De wildt SN, Tibboel D, Van dijk M. The COMFORT behaviour scale detects clinically meaningful effects of analgesic and sedative treatment . Eur J Pain . 2015;19(4):473-9. doi:10.1002/ejp.569

Bourdel N, Alves J, Pickering G, Ramilo I, Roman H, Canis M. Systematic review of endometriosis pain assessment: how to choose a scale? . Human Reproduction Update . 2015;21(1):136-152.

doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu046

Le may S, Ballard A, Khadra C, et al. Comparison of the psychometric properties of 3 pain scales used in the pediatric emergency department: visual analogue scale, faces pain scale-revised, and colour analogue scale . Pain . 2018;159(8):1508-1517. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001236.

George Francis McMahon, I. I. I. (n.d.). Comparison of a numeric and a descriptive pain scale in the Occupational Medicine Setting . SJSU ScholarWorks .

Lin, C, Poquet, N. The Brief Pain Inventory . Journal of Physiotherapy . 2016;62(52). doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2015.07.001

Atkinson JH, Slater MA, Capparelli EV, et al. A randomized controlled trial of gabapentin for chronic low back pain with and without a radiating component . Pain . 2016;157(7):1499-507. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000554

U.S. Department of Defense. Your pain on a scale of 1-10? Check out a new DOD way to evaluate pain .

Sarpangala M, Devasya A, George AL, Kumara A, Panicker P, Mathew M. Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of lignocaine containing topical anesthetic agents during extraction of deciduous anterior teeth . Minerva Stomatol . 2018;67(1):26-31. doi:10.23736/S0026-4970.17.04052-3

By Erica Jacques Erica Jacques, OT, is a board-certified occupational therapist at a level one trauma center.

Assessment and Management of Pain

- Télécharger (fr)

- scaricamento (it)

- descargar (es)

Purpose and scope

This guideline provides evidence-based recommendations for nurses and other members of the interprofessional team who are assessing and managing people with the presence or risk of any type of pain. We’ve designed this guideline to help nurses and their interprofessional teams become more…

This guideline provides evidence-based recommendations for nurses and other members of the interprofessional team who are assessing and managing people with the presence or risk of any type of pain.

We’ve designed this guideline to help nurses and their interprofessional teams become more comfortable, confident and competent. A specific focus: building the core competencies of nurses to help them be more effective in assessing and managing of pain without focusing on the type or origin of the pain. It is intended for use in all domains of health care and public health, including clinical work, administration and education.

Get started

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (2013). Assessment and Management of Pain (third edition). Toronto, ON: Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario.

Recommendations

Do you want to learn about and implement the most- up-to-date evidence-based recommendations on this topic with your colleagues? Download and share the full best practice guideline (BPG), Assessment and Management of Pain . See below for a snapshot of the recommendations from this BPG. We strongly suggest you review the full BPG before implementing the recommendations and good practice statements. The BPG also includes further resources to support implementation and evaluation.

Recommendation 1.1: Screen for the presence, or risk of, any type of pain:

- On admission or visit with a health-care professional;

- After a change in medical status; and

- Prior to, during and after a procedure.

Recommendation 1.2: Perform a comprehensive pain assessment on persons screened having the presence, or risk of, any type of pain using a systematic approach and appropriate, validated tools.

Recommendation 1.3: Perform a comprehensive pain assessment on persons unable to self-report using a validated tool.

Recommendation 1.4: Explore the person’s beliefs, knowledge and level of understanding about pain and pain management.

Recommendation 1.5: Document the person’s pain characteristics.

Recommendation 2.1: Collaborate with the person to identify their goals for pain management and suitable strategies to ensure a comprehensive approach to the plan of care.

Recommendation 2.2: Establish a comprehensive plan of care that incorporates the goals of the person and the interprofessional team and addresses:

- Assessment findings;

- The person’s beliefs and knowledge and level of understanding; and

- The person’s attributes and pain characteristics.

Implementation

Recommendation 3.1: Implement the pain management plan using principles that maximize efficacy and minimize the adverse effects of pharmacological interventions including:

- Multimodal analgesic approach;

- Changing of opioids (dose or routes) when necessary;

- Prevention, assessment and management of adverse effects during the administration of opioid analgesics; and

- Prevention, assessment and management of opioid risk.

Recommendation 3.2: Evaluate any non-pharmacological (physical and psychological) interventions for effectiveness and the potential for interactions with pharmacological interventions.

Recommendation 3.3: Teach the person, their family and caregivers about the pain management strategies in their plan of care and address known concerns and misbeliefs.

Recommendation 4.1: Reassess the person’s response to the pain management interventions consistently using the same re-evaluation tool. The frequency of reassessments will be determined by:

- Presence of pain;

- Pain intensity;

- Stability of the person’s medical condition;

- Type of pain e.g. acute versus persistent; and

- Practice setting.

Recommendation 4.2: Communicate and document the person’s responses to the pain management plan.

Education for health providers

Recommendation 5.1: Educational institutions should incorporate this guideline, Assessment and Management of Pain (3rd ed.), into basic and interprofessional curricula for registered nurses, registered practical nurses and doctor of medicine programs to promote evidence-based practice.

Recommendation 5.2: Incorporate content on knowledge translation strategies into education programs for health-care providers to move evidence related to the assessment and management of pain into practice.

Recommendation 5.3: Promote interprofessional education and collaboration related to the assessment and management of pain in academic institutions.

Recommendation 5.4: Health-care professionals should participate in continuing education opportunities to enhance specific knowledge and skills to competently assess and manage pain, based on this guideline, Assessment and Management of Pain (3rd ed.).

Organization and policy

Recommendation 6.1: Establish pain assessment and management as a strategic clinical priority.

Recommendation 6.2: Establish a model of care to support interprofessional collaboration for the effective assessment and management of pain.

Recommendation 6.3: Use the knowledge translation process and multifaceted strategies within organizations to assist health-care providers to use the best evidence on assessing and managing pain in practice.

Recommendation 6.4: Use a systematic organization-wide approach to implement Assessment and Management of Pain (3rd ed.) best practice guideline and provide resources and organizational and administrative supports to facilitate uptake.

Disclaimer: These guidelines are not binding for nurses, other health providers or the organizations that employ them. The use of these guidelines should be flexible and based on individual needs and local circumstances. They constitute neither a liability nor discharge from liability. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the contents at the time of publication, neither the authors nor the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) gives any guarantee as to the accuracy of the information contained in them or accepts any liability with respect to loss, damage, injury or expense arising from any such errors or omission in the contents of this work.

Revision status

Current edition published 2013.

About the next edition

The Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario (RNAO) is developing a fourth edition of this best practice guideline (BPG), with the working title Assessment and Management of Pain . The anticipated publication date is 2024.

This new edition will replace Assessment and Management of Pain (2013).

Help shape BPGs

- Apply to become a panel member

- Apply to become a stakeholder

Contact us for any questions.

- 416-599-1925 1-800-268-7199 (toll-free)

© 2024 RNAO. All rights reserved.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Pain is the most common complaint seen in a primary care office. There are over 50 million Americans, 20% of all patients, that suffer from chronic pain in the United States.[1] The prevalence of chronic pain is even higher in the elderly.[2] With opioid use disorder on the rise, it is critical to treat a patient's pain in a logical manner adequately.