Proposal Template AI

Free proposal templates in word, powerpoint, pdf and more

Action Research Proposal Template: A Comprehensive Guide + Free Template Download + How to Write it

Action research proposal template: a guide for real-world problem solving.

As a researcher dedicated to making a real impact in the world, I understand the importance of developing an action research proposal that goes beyond the standard academic proposal . Action research is a powerful tool for bringing about meaningful change in a specific context, and a well-crafted proposal is essential for ensuring that the research is both rigorous and relevant to the needs of the community or organization being studied. This article will provide a comprehensive guide to creating an action research proposal template, outlining the key components and considerations that set it apart from a traditional research proposal . Whether you are a student, practitioner, or academic, understanding the unique elements of an action research proposal will enable you to approach your research projects with a focus on real-world problem solving and positive change.

Action Research Proposal Template

The Effectiveness of Implementing Technology in a Mathematics Classroom

Background and Introduction:

In this section, provide a brief overview of the research problem and context. Discuss the rationale for conducting the action research and provide a clear statement of the research question or objective.

The incorporation of technology in educational settings has become increasingly prevalent in recent years. However, the effectiveness of using technology in mathematics classrooms is still a subject of debate. This action research aims to investigate the impact of implementing technology on students’ mathematical abilities and engagement in a middle school classroom.

Research Goals and Objectives:

Clearly outline the specific goals and objectives of the action research. What do you hope to achieve through this study? What are the intended outcomes?

The primary goal of this action research is to analyze the impact of technology integration on students’ mathematical performance and attitudes towards the subject. The objectives include assessing changes in students’ test scores, observing their engagement during technology-enhanced lessons, and gathering feedback from both students and teachers about their experiences with technology in the classroom.

Research Methodology:

Detail the research methodology that will be used to conduct the action research. This includes a description of the participants, data collection methods , and data analysis techniques .

The action research will be conducted in a 7th-grade mathematics classroom with a total of 30 students. Data will be collected through pre- and post-assessments, classroom observations, and student and teacher interviews. Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical methods, while qualitative data will be subjected to thematic analysis to identify recurring patterns and themes.

Action Plan:

Provide a timeline and action plan for implementing the research. How will the data collection and analysis be carried out? What are the key milestones and deadlines?

The action research will be carried out over the course of 10 weeks. Week 1-2 will involve pre-assessments and the introduction of technology integration into the classroom. Weeks 3-8 will focus on implementing technology-enhanced lessons and collecting data through observations and student feedback. Weeks 9-10 will be dedicated to post-assessments and data analysis .

Expected Outcomes and Impact:

Discuss the anticipated outcomes of the action research and the potential impact on the educational setting. How will the findings contribute to the existing knowledge in the field?

It is expected that the findings of this action research will demonstrate the positive impact of technology integration on students’ mathematical performance and engagement. The results will provide valuable insights for educators and policymakers on the effectiveness of using technology in mathematics classrooms, potentially influencing future curriculum and instructional design decisions.

Budget and Resources:

Outline the budget and resources required to conduct the action research. This may include costs for technology equipment, data collection materials, and personnel.

The action research will require funding for the purchase of tablets or laptops for the classroom, as well as printing materials for assessments and consent forms. Additionally, there may be personnel costs for hiring a research assistant to aid in data collection and analysis.

Conclusion:

Summarize the key points of the action research proposal and reiterate the significance of the study . Emphasize the potential benefits of conducting the research and the importance of addressing the research question or objective.

References:

List all of the references cited in the action research proposal using the appropriate citation style (e.g., APA, MLA). This section demonstrates the scholarly foundation of the proposed research.

My advice on using the Action Research Proposal Template:

When using this template, be sure to customize it to fit the specific context and goals of your action research. Tailor the examples and language to your own research topic and consider seeking feedback from peers or mentors to ensure the proposal is clear and comprehensive. Pay close attention to the research methodology and action plan, as these sections will guide the implementation and data collection process. Lastly, be diligent in your budget and resource planning to ensure the successful execution of the action research.

Download free Action Research Proposal Template in Word DocX, Powerpoint PPTX, and PDF. We included Action Research Proposal Template examples as well.

Download Free Action Research Proposal Template PDF and Examples Download Free Action Research Proposal Template Word Document

Download Free Action Research Proposal Template Powerpoint

Action Research Proposal Template FAQ

1. what is an action research proposal.

An action research proposal is a document that outlines the plan for an action research project . It includes the background of the issue, the purpose of the research, the research questions , the methodology, and the expected outcomes .

2. What should be included in an action research proposal?

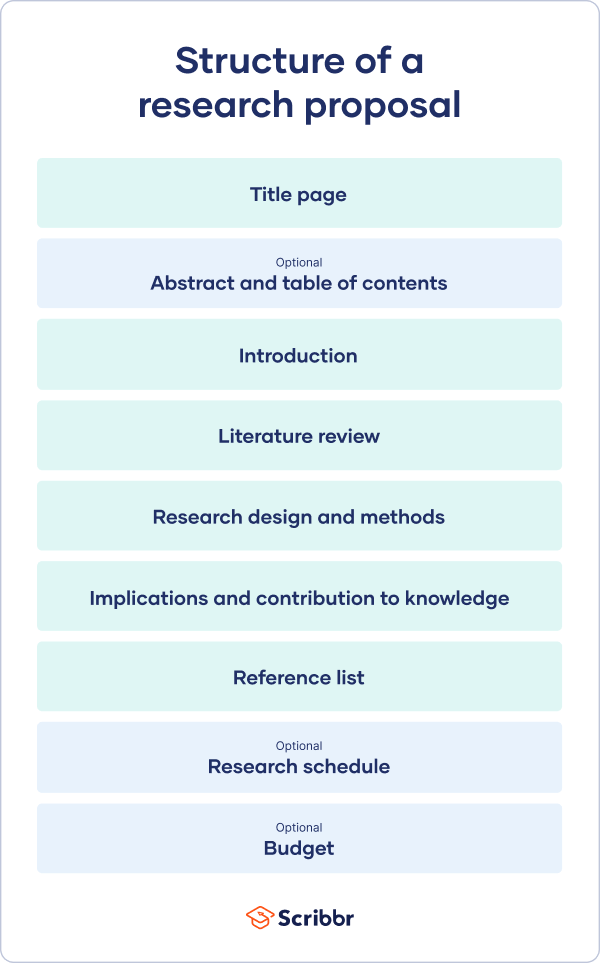

An action research proposal should include an introduction to the research problem, a literature review , the research questions , the methodology, the timeline for the project, the expected outcomes , and a brief discussion of how the research will be implemented and evaluated.

3. How long should an action research proposal be?

An action research proposal should typically be around 5-10 pages long, including all necessary components such as the background, literature review , methodology, and expected outcomes.

4. What is the purpose of an action research proposal?

The purpose of an action research proposal is to outline the plan for conducting an action research project, including the steps to be taken, the goals to be achieved, and the expected impact of the research.

5. Can an action research proposal be modified during the course of the research?

Yes, an action research proposal can be modified as the research progresses and new information becomes available. It is important to be flexible and willing to make changes as needed to ensure the success of the research project.

Related Posts:

- Academic Proposal Template: A Comprehensive Guide +…

- Community Event Proposal Template: A Comprehensive…

- Business Problem Solving Proposal Template: A…

- Community Project Proposal Template: A Comprehensive…

- Change Management Proposal Template: A Comprehensive…

- Change Order Proposal Template: A Comprehensive…

- Research Proposal Template: A Comprehensive Guide +…

- Real Estate Business Proposal Template: A…

Jevannel's Blog

Learning | Happy Living | Personality Development | Self-Care | Study Tips | Study Essentials | Teaching Tools | Research Tips

#BlogChallenge #blogging #bloggingbranding #GREATGOOGLE #justthoughts #poemporn #poetry #poetryoflove #randomposts bible verse blogging challenge Blogging for Money Blogging for Teaching Bring Gratitute CoVID-19 Dissertation Journey Google Classroom How to Love Research Letting go Oral Care personal notes PhD Student Pinay Teacher poetry Productivity random writing Reading Reflections Research Proposal Research Writing Scholarships Self-Care self care student life studying study tips Teachers Who Blog teaching Teaching Philosophy Teaching Tools travel destinations in the Philippines travel maestra White Teeth writing challenge Yoga Practice

How to Write An Action Research (Proposal)

Action research is a type of research that involves the systematic and reflective study of one’s own practice in order to improve it. It is a practical and collaborative approach to problem-solving that can be used by individuals or groups in various settings. In this guide on How to Write An Action Research , we will outline the steps to writing an action research paper.

Step 1: Select a Problem or Issue

The first step in writing an action research paper is to identify a problem or issue that you would like to address. The problem or issue should be relevant to your area of work or interest and should be specific and measurable. Once you have identified the problem or issue, you can begin to formulate a research question that will guide your inquiry.

Step 2: Review the Literature

The next step is to review the literature on the problem or issue you have identified. This will help you to understand what has been done in the past and what the current state of knowledge is. You should look for both academic and practical sources of information and use them to inform your research question.

Step 3: Develop a Research Plan

The third step is to develop a research plan. This should include a description of the problem or issue, the research question, the data collection methods, and the analysis plan. You should also identify any potential ethical considerations and address them in your plan.

Step 4: Collect Data

The fourth step is to collect data. This can be done through a variety of methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, and document analysis. The data you collect should be relevant to your research question and should be analyzed using appropriate methods.

Step 5: Analyze the Data

The fifth step is to analyze the data you have collected. This can be done using both quantitative and qualitative methods, depending on the type of data you have collected. The analysis should be guided by your research question and should help you to identify patterns, trends, and relationships in the data.

Step 6: Reflect on the Findings

The sixth step is to reflect on the findings of your analysis. This involves thinking about what the data means in relation to your research question and how it can be used to address the problem or issue you identified at the beginning of the research process.

Step 7: Develop an Action Plan

The final step is to develop an action plan . This should outline the steps you will take to address the problem or issue you identified. The action plan should be based on the findings of your research and should be practical and achievable.

In conclusion, writing an action research paper requires a systematic and reflective approach to problem-solving. It involves identifying a problem or issue, reviewing the literature, developing a research plan, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and developing an action plan.

By following these steps on How to Write An Action Research , you can use action research to improve your practice and make a positive impact in your field.

Jevannel is passionate about teaching and learning about anything. She loves to share her words with the world, hoping for readers to get something from her works. She specializes in Science Education and Research and she also writes poetry and many other things.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

One response to “How to Write An Action Research (Proposal)”

[…] We cannot teach what we don’t know yet. Let the students explore. Make them READ. Let them FEEL, and they will enjoy the exciting journey to discover new things, explore various real experiences and develop an understanding of the world through RESEARCH. […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide...

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

Published on January 27, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

Table of contents

Types of action research, action research models, examples of action research, action research vs. traditional research, advantages and disadvantages of action research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about action research.

There are 2 common types of action research: participatory action research and practical action research.

- Participatory action research emphasizes that participants should be members of the community being studied, empowering those directly affected by outcomes of said research. In this method, participants are effectively co-researchers, with their lived experiences considered formative to the research process.

- Practical action research focuses more on how research is conducted and is designed to address and solve specific issues.

Both types of action research are more focused on increasing the capacity and ability of future practitioners than contributing to a theoretical body of knowledge.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Action research is often reflected in 3 action research models: operational (sometimes called technical), collaboration, and critical reflection.

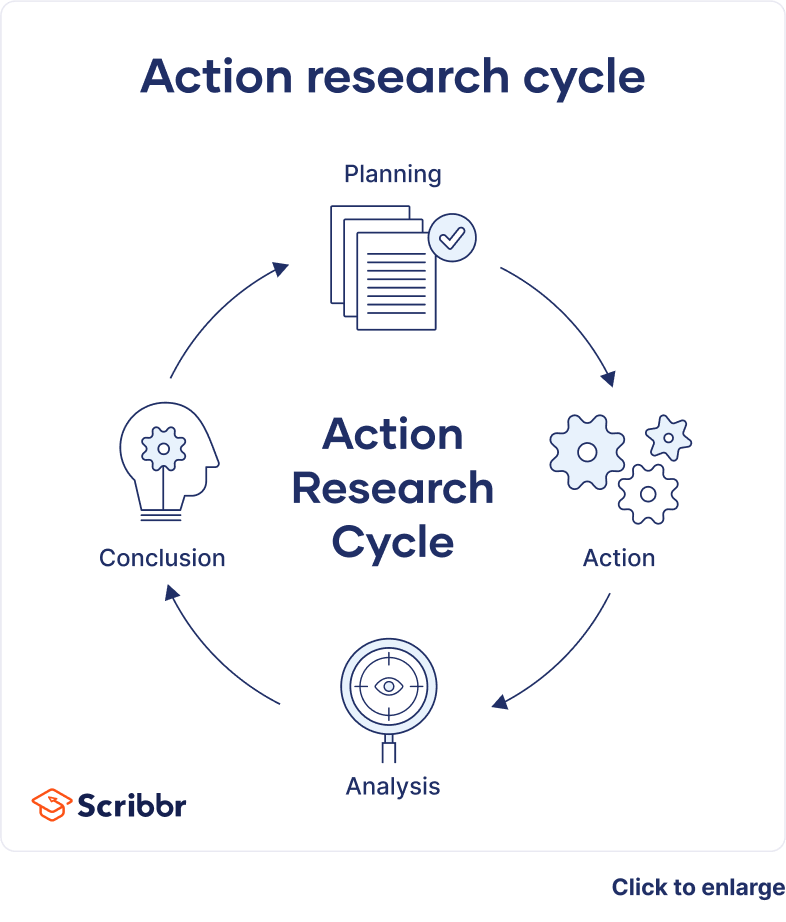

- Operational (or technical) action research is usually visualized like a spiral following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

- Collaboration action research is more community-based, focused on building a network of similar individuals (e.g., college professors in a given geographic area) and compiling learnings from iterated feedback cycles.

- Critical reflection action research serves to contextualize systemic processes that are already ongoing (e.g., working retroactively to analyze existing school systems by questioning why certain practices were put into place and developed the way they did).

Action research is often used in fields like education because of its iterative and flexible style.

After the information was collected, the students were asked where they thought ramps or other accessibility measures would be best utilized, and the suggestions were sent to school administrators. Example: Practical action research Science teachers at your city’s high school have been witnessing a year-over-year decline in standardized test scores in chemistry. In seeking the source of this issue, they studied how concepts are taught in depth, focusing on the methods, tools, and approaches used by each teacher.

Action research differs sharply from other types of research in that it seeks to produce actionable processes over the course of the research rather than contributing to existing knowledge or drawing conclusions from datasets. In this way, action research is formative , not summative , and is conducted in an ongoing, iterative way.

As such, action research is different in purpose, context, and significance and is a good fit for those seeking to implement systemic change.

Action research comes with advantages and disadvantages.

- Action research is highly adaptable , allowing researchers to mold their analysis to their individual needs and implement practical individual-level changes.

- Action research provides an immediate and actionable path forward for solving entrenched issues, rather than suggesting complicated, longer-term solutions rooted in complex data.

- Done correctly, action research can be very empowering , informing social change and allowing participants to effect that change in ways meaningful to their communities.

Disadvantages

- Due to their flexibility, action research studies are plagued by very limited generalizability and are very difficult to replicate . They are often not considered theoretically rigorous due to the power the researcher holds in drawing conclusions.

- Action research can be complicated to structure in an ethical manner . Participants may feel pressured to participate or to participate in a certain way.

- Action research is at high risk for research biases such as selection bias , social desirability bias , or other types of cognitive biases .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.

Action research is focused on solving a problem or informing individual and community-based knowledge in a way that impacts teaching, learning, and other related processes. It is less focused on contributing theoretical input, instead producing actionable input.

Action research is particularly popular with educators as a form of systematic inquiry because it prioritizes reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice. Educators are able to simultaneously investigate an issue as they solve it, and the method is very iterative and flexible.

A cycle of inquiry is another name for action research . It is usually visualized in a spiral shape following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2024, January 12). What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/action-research/

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th edition). Routledge.

Naughton, G. M. (2001). Action research (1st edition). Routledge.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is an observational study | guide & examples, primary research | definition, types, & examples, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Preparing for Action Research in the Classroom: Practical Issues

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What sort of considerations are necessary to take action in your educational context?

- How do you facilitate an action plan without disrupting your teaching?

- How do you respond when the unplanned happens during data collection?

An action research project is a practical endeavor that will ultimately be shaped by your educational context and practice. Now that you have developed a literature review, you are ready to revise your initial plans and begin to plan your project. This chapter will provide some advice about your considerations when undertaking an action research project in your classroom.

Maintain Focus

Hopefully, you found a lot a research on your topic. If so, you will now have a better understanding of how it fits into your area and field of educational research. Even though the topic and area you are researching may not be small, your study itself should clearly focus on one aspect of the topic in your classroom. It is important to maintain clarity about what you are investigating because a lot will be going on simultaneously during the research process and you do not want to spend precious time on erroneous aspects that are irrelevant to your research.

Even though you may view your practice as research, and vice versa, you might want to consider your research project as a projection or megaphone for your work that will bring attention to the small decisions that make a difference in your educational context. From experience, our concern is that you will find that researching one aspect of your practice will reveal other interconnected aspects that you may find interesting, and you will disorient yourself researching in a confluence of interests, commitments, and purposes. We simply want to emphasize – don’t try to research everything at once. Stay focused on your topic, and focus on exploring it in depth, instead of its many related aspects. Once you feel you have made progress in one aspect, you can then progress to other related areas, as new research projects that continue the research cycle.

Identify a Clear Research Question

Your literature review should have exposed you to an array of research questions related to your topic. More importantly, your review should have helped identify which research questions we have addressed as a field, and which ones still need to be addressed . More than likely your research questions will resemble ones from your literature review, while also being distinguishable based upon your own educational context and the unexplored areas of research on your topic.

Regardless of how your research question took shape, it is important to be clear about what you are researching in your educational context. Action research questions typically begin in ways related to “How does … ?” or “How do I/we … ?”, for example:

Research Question Examples

- How does a semi-structured morning meeting improve my classroom community?

- How does historical fiction help students think about people’s agency in the past?

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences?

- How do we increase student responsibility for their own learning as a team of teachers?

I particularly favor questions with I or we, because they emphasize that you, the actor and researcher, will be clearly taking action to improve your practice. While this may seem rather easy, you need to be aware of asking the right kind of question. One issue is asking a too pointed and closed question that limits the possibility for analysis. These questions tend to rely on quantitative answers, or yes/no answers. For example, “How many students got a 90% or higher on the exam, after reviewing the material three times?

Another issue is asking a question that is too broad, or that considers too many variables. For example, “How does room temperature affect students’ time-on-task?” These are obviously researchable questions, but the aim is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables that has little or no value to your daily practice.

I also want to point out that your research question will potentially change as the research develops. If you consider the question:

As you do an activity, you may find that students are more comfortable and engaged by acting sentences out in small groups, instead of the whole class. Therefore, your question may shift to:

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences, in small groups ?

By simply engaging in the research process and asking questions, you will open your thinking to new possibilities and you will develop new understandings about yourself and the problematic aspects of your educational context.

Understand Your Capabilities and Know that Change Happens Slowly

Similar to your research question, it is important to have a clear and realistic understanding of what is possible to research in your specific educational context. For example, would you be able to address unsatisfactory structures (policies and systems) within your educational context? Probably not immediately, but over time you potentially could. It is much more feasible to think of change happening in smaller increments, from within your own classroom or context, with you as one change agent. For example, you might find it particularly problematic that your school or district places a heavy emphasis on traditional grades, believing that these grades are often not reflective of the skills students have or have not mastered. Instead of attempting to research grading practices across your school or district, your research might instead focus on determining how to provide more meaningful feedback to students and parents about progress in your course. While this project identifies and addresses a structural issue that is part of your school and district context, to keep things manageable, your research project would focus the outcomes on your classroom. The more research you do related to the structure of your educational context the more likely modifications will emerge. The more you understand these modifications in relation to the structural issues you identify within your own context, the more you can influence others by sharing your work and enabling others to understand the modification and address structural issues within their contexts. Throughout your project, you might determine that modifying your grades to be standards-based is more effective than traditional grades, and in turn, that sharing your research outcomes with colleagues at an in-service presentation prompts many to adopt a similar model in their own classrooms. It can be defeating to expect the world to change immediately, but you can provide the spark that ignites coordinated changes. In this way, action research is a powerful methodology for enacting social change. Action research enables individuals to change their own lives, while linking communities of like-minded practitioners who work towards action.

Plan Thoughtfully

Planning thoughtfully involves having a path in mind, but not necessarily having specific objectives. Due to your experience with students and your educational context, the research process will often develop in ways as you expected, but at times it may develop a little differently, which may require you to shift the research focus and change your research question. I will suggest a couple methods to help facilitate this potential shift. First, you may want to develop criteria for gauging the effectiveness of your research process. You may need to refine and modify your criteria and your thinking as you go. For example, we often ask ourselves if action research is encouraging depth of analysis beyond my typical daily pedagogical reflection. You can think about this as you are developing data collection methods and even when you are collecting data. The key distinction is whether the data you will be collecting allows for nuance among the participants or variables. This does not mean that you will have nuance, but it should allow for the possibility. Second, criteria are shaped by our values and develop into standards of judgement. If we identify criteria such as teacher empowerment, then we will use that standard to think about the action contained in our research process. Our values inform our work; therefore, our work should be judged in relation to the relevance of our values in our pedagogy and practice.

Does Your Timeline Work?

While action research is situated in the temporal span that is your life, your research project is short-term, bounded, and related to the socially mediated practices within your educational context. The timeline is important for bounding, or setting limits to your research project, while also making sure you provide the right amount of time for the data to emerge from the process.

For example, if you are thinking about examining the use of math diaries in your classroom, you probably do not want to look at a whole semester of entries because that would be a lot of data, with entries related to a wide range of topics. This would create a huge data analysis endeavor. Therefore, you may want to look at entries from one chapter or unit of study. Also, in terms of timelines, you want to make sure participants have enough time to develop the data you collect. Using the same math example, you would probably want students to have plenty of time to write in the journals, and also space out the entries over the span of the chapter or unit.

In relation to the examples, we think it is an important mind shift to not think of research timelines in terms of deadlines. It is vitally important to provide time and space for the data to emerge from the participants. Therefore, it would be potentially counterproductive to rush a 50-minute data collection into 20 minutes – like all good educators, be flexible in the research process.

Involve Others

It is important to not isolate yourself when doing research. Many educators are already isolated when it comes to practice in their classroom. The research process should be an opportunity to engage with colleagues and open up your classroom to discuss issues that are potentially impacting your entire educational context. Think about the following relationships:

Research participants

You may invite a variety of individuals in your educational context, many with whom you are in a shared situation (e.g. colleagues, administrators). These participants may be part of a collaborative study, they may simply help you develop data collection instruments or intervention items, or they may help to analyze and make sense of the data. While the primary research focus will be you and your learning, you will also appreciate how your learning is potentially influencing the quality of others’ learning.

We always tell educators to be public about your research, or anything exciting that is happening in your educational context, for that matter. In terms of research, you do not want it to seem mysterious to any stakeholder in the educational context. Invite others to visit your setting and observe your research process, and then ask for their formal feedback. Inviting others to your classroom will engage and connect you with other stakeholders, while also showing that your research was established in an ethic of respect for multiple perspectives.

Critical friends or validators

Using critical friends is one way to involve colleagues and also validate your findings and conclusions. While your positionality will shape the research process and subsequently your interpretations of the data, it is important to make sure that others see similar logic in your process and conclusions. Critical friends or validators provide some level of certification that the frameworks you use to develop your research project and make sense of your data are appropriate for your educational context. Your critical friends and validators’ suggestions will be useful if you develop a report or share your findings, but most importantly will provide you confidence moving forward.

Potential researchers

As an educational researcher, you are involved in ongoing improvement plans and district or systemic change. The flexibility of action research allows it to be used in a variety of ways, and your initial research can spark others in your context to engage in research either individually for their own purposes, or collaboratively as a grade level, team, or school. Collaborative inquiry with other educators is an emerging form of professional learning and development for schools with school improvement plans. While they call it collaborative inquiry, these schools are often using an action research model. It is good to think of all of your colleagues as potential research collaborators in the future.

Prioritize Ethical Practice

Try to always be cognizant of your own positionality during the action research process, its relation to your educational context, and any associated power relation to your positionality. Furthermore, you want to make sure that you are not coercing or engaging participants into harmful practices. While this may seem obvious, you may not even realize you are harming your participants because you believe the action is necessary for the research process.

For example, commonly teachers want to try out an intervention that will potentially positively impact their students. When the teacher sets up the action research study, they may have a control group and an experimental group. There is potential to impair the learning of one of these groups if the intervention is either highly impactful or exceedingly worse than the typical instruction. Therefore, teachers can sometimes overlook the potential harm to students in pursuing an experimental method of exploring an intervention.

If you are working with a university researcher, ethical concerns will be covered by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). If not, your school or district may have a process or form that you would need to complete, so it would beneficial to check your district policies before starting. Other widely accepted aspects of doing ethically informed research, include:

Confirm Awareness of Study and Negotiate Access – with authorities, participants and parents, guardians, caregivers and supervisors (with IRB this is done with Informed Consent).

- Promise to Uphold Confidentiality – Uphold confidentiality, to your fullest ability, to protect information, identity and data. You can identify people if they indicate they want to be recognized for their contributions.

- Ensure participants’ rights to withdraw from the study at any point .

- Make sure data is secured, either on password protected computer or lock drawer .

Prepare to Problematize your Thinking

Educational researchers who are more philosophically-natured emphasize that research is not about finding solutions, but instead is about creating and asking new and more precise questions. This is represented in the action research process shown in the diagrams in Chapter 1, as Collingwood (1939) notes the aim in human interaction is always to keep the conversation open, while Edward Said (1997) emphasized that there is no end because whatever we consider an end is actually the beginning of something entirely new. These reflections have perspective in evaluating the quality in research and signifying what is “good” in “good pedagogy” and “good research”. If we consider that action research is about studying and reflecting on one’s learning and how that learning influences practice to improve it, there is nothing to stop your line of inquiry as long as you relate it to improving practice. This is why it is necessary to problematize and scrutinize our practices.

Ethical Dilemmas for Educator-Researchers

Classroom teachers are increasingly expected to demonstrate a disposition of reflection and inquiry into their own practice. Many advocate for schools to become research centers, and to produce their own research studies, which is an important advancement in acknowledging and addressing the complexity in today’s schools. When schools conduct their own research studies without outside involvement, they bypass outside controls over their studies. Schools shift power away from the oversight of outside experts and ethical research responsibilities are shifted to those conducting the formal research within their educational context. Ethics firmly grounded and established in school policies and procedures for teaching, becomes multifaceted when teaching practice and research occur simultaneously. When educators conduct research in their classrooms, are they doing so as teachers or as researchers, and if they are researchers, at what point does the teaching role change to research? Although the notion of objectivity is a key element in traditional research paradigms, educator-based research acknowledges a subjective perspective as the educator-researcher is not viewed separately from the research. In action research, unlike traditional research, the educator as researcher gains access to the research site by the nature of the work they are paid and expected to perform. The educator is never detached from the research and remains at the research site both before and after the study. Because studying one’s practice comprises working with other people, ethical deliberations are inevitable. Educator-researchers confront role conflict and ambiguity regarding ethical issues such as informed consent from participants, protecting subjects (students) from harm, and ensuring confidentiality. They must demonstrate a commitment toward fully understanding ethical dilemmas that present themselves within the unique set of circumstances of the educational context. Questions about research ethics can feel exceedingly complex and in specific situations, educator- researchers require guidance from others.

Think about it this way. As a part-time historian and former history teacher I often problematized who we regard as good and bad people in history. I (Clark) grew up minutes from Jesse James’ childhood farm. Jesse James is a well-documented thief, and possibly by today’s standards, a terrorist. He is famous for daylight bank robberies, as well as the sheer number of successful robberies. When Jesse James was assassinated, by a trusted associate none-the-less, his body travelled the country for people to see, while his assailant and assailant’s brother reenacted the assassination over 1,200 times in theaters across the country. Still today in my hometown, they reenact Jesse James’ daylight bank robbery each year at the Fall Festival, immortalizing this thief and terrorist from our past. This demonstrates how some people saw him as somewhat of hero, or champion of some sort of resistance, both historically and in the present. I find this curious and ripe for further inquiry, but primarily it is problematic for how we think about people as good or bad in the past. Whatever we may individually or collectively think about Jesse James as a “good” or “bad” person in history, it is vitally important to problematize our thinking about him. Talking about Jesse James may seem strange, but it is relevant to the field of action research. If we tell people that we are engaging in important and “good” actions, we should be prepared to justify why it is “good” and provide a theoretical, epistemological, or ontological rationale if possible. Experience is never enough, you need to justify why you act in certain ways and not others, and this includes thinking critically about your own thinking.

Educators who view inquiry and research as a facet of their professional identity must think critically about how to design and conduct research in educational settings to address respect, justice, and beneficence to minimize harm to participants. This chapter emphasized the due diligence involved in ethically planning the collection of data, and in considering the challenges faced by educator-researchers in educational contexts.

Planning Action

After the thinking about the considerations above, you are now at the stage of having selected a topic and reflected on different aspects of that topic. You have undertaken a literature review and have done some reading which has enriched your understanding of your topic. As a result of your reading and further thinking, you may have changed or fine-tuned the topic you are exploring. Now it is time for action. In the last section of this chapter, we will address some practical issues of carrying out action research, drawing on both personal experiences of supervising educator-researchers in different settings and from reading and hearing about action research projects carried out by other researchers.

Engaging in an action research can be a rewarding experience, but a beneficial action research project does not happen by accident – it requires careful planning, a flexible approach, and continuous educator-researcher reflection. Although action research does not have to go through a pre-determined set of steps, it is useful here for you to be aware of the progression which we presented in Chapter 2. The sequence of activities we suggested then could be looked on as a checklist for you to consider before planning the practical aspects of your project.

We also want to provide some questions for you to think about as you are about to begin.

- Have you identified a topic for study?

- What is the specific context for the study? (It may be a personal project for you or for a group of researchers of which you are a member.)

- Have you read a sufficient amount of the relevant literature?

- Have you developed your research question(s)?

- Have you assessed the resource needed to complete the research?

As you start your project, it is worth writing down:

- a working title for your project, which you may need to refine later;

- the background of the study , both in terms of your professional context and personal motivation;

- the aims of the project;

- the specific outcomes you are hoping for.

Although most of the models of action research presented in Chapter 1 suggest action taking place in some pre-defined order, they also allow us the possibility of refining our ideas and action in the light of our experiences and reflections. Changes may need to be made in response to your evaluation and your reflections on how the project is progressing. For example, you might have to make adjustments, taking into account the students’ responses, your observations and any observations of your colleagues. All this is very useful and, in fact, it is one of the features that makes action research suitable for educational research.

Action research planning sheet

In the past, we have provided action researchers with the following planning list that incorporates all of these considerations. Again, like we have said many times, this is in no way definitive, or lock-in-step procedure you need to follow, but instead guidance based on our perspective to help you engage in the action research process. The left column is the simplified version, and the right column offers more specific advice if need.

Figure 4.1 Planning Sheet for Action Research

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Linking Research to Action: A Simple Guide to Writing an Action Research Report

What Is Action Research, and Why Do We Do It?

Action research is any research into practice undertaken by those involved in that practice, with the primary goal of encouraging continued reflection and making improvement. It can be done in any professional field, including medicine, nursing, social work, psychology, and education. Action research is particularly popular in the field of education. When it comes to teaching, practitioners may be interested in trying out different teaching methods in the classroom, but are unsure of their effectiveness. Action research provides an opportunity to explore the effectiveness of a particular teaching practice, the development of a curriculum, or your students’ learning, hence making continual improvement possible. In other words, the use of an interactive action-and-research process enables practitioners to get an idea of what they and their learners really do inside of the classroom, not merely what they think they can do. By doing this, it is hoped that both the teaching and the learning occurring in the classroom can be better tailored to fit the learners’ needs.

You may be wondering how action research differs from traditional research. The term itself already suggests that it is concerned with both “action” and “research,” as well as the association between the two. Kurt Lewin (1890-1947), a famous psychologist who coined this term, believed that there was “no action without research; no research without action” (Marrow, 1969, p.163). It is certainly possible, and perhaps commonplace, for people to try to have one without the other, but the unique combination of the two is what distinguishes action research from most other forms of enquiry. Traditional research emphasizes the review of prior research, rigorous control of the research design, and generalizable and preferably statistically significant results, all of which help examine the theoretical significance of the issue. Action research, with its emphasis on the insider’s perspective and the practical significance of a current issue, may instead allow less representative sampling, looser procedures, and the presentation of raw data and statistically insignificant results.

What Should We Include in an Action Research Report?

The components put into an action research report largely coincide with the steps used in the action research process. This process usually starts with a question or an observation about a current problem. After identifying the problem area and narrowing it down to make it more manageable for research, the development process continues as you devise an action plan to investigate your question. This will involve gathering data and evidence to support your solution. Common data collection methods include observation of individual or group behavior, taking audio or video recordings, distributing questionnaires or surveys, conducting interviews, asking for peer observations and comments, taking field notes, writing journals, and studying the work samples of your own and your target participants. You may choose to use more than one of these data collection methods. After you have selected your method and are analyzing the data you have collected, you will also reflect upon your entire process of action research. You may have a better solution to your question now, due to the increase of your available evidence. You may also think about the steps you will try next, or decide that the practice needs to be observed again with modifications. If so, the whole action research process starts all over again.

In brief, action research is more like a cyclical process, with the reflection upon your action and research findings affecting changes in your practice, which may lead to extended questions and further action. This brings us back to the essential steps of action research: identifying the problem, devising an action plan, implementing the plan, and finally, observing and reflecting upon the process. Your action research report should comprise all of these essential steps. Feldman and Weiss (n.d.) summarized them as five structural elements, which do not have to be written in a particular order. Your report should:

- Describe the context where the action research takes place. This could be, for example, the school in which you teach. Both features of the school and the population associated with it (e.g., students and parents) would be illustrated as well.

- Contain a statement of your research focus. This would explain where your research questions come from, the problem you intend to investigate, and the goals you want to achieve. You may also mention prior research studies you have read that are related to your action research study.

- Detail the method(s) used. This part includes the procedures you used to collect data, types of data in your report, and justification of your used strategies.

- Highlight the research findings. This is the part in which you observe and reflect upon your practice. By analyzing the evidence you have gathered, you will come to understand whether the initial problem has been solved or not, and what research you have yet to accomplish.

- Suggest implications. You may discuss how the findings of your research will affect your future practice, or explain any new research plans you have that have been inspired by this report’s action research.

The overall structure of your paper will actually look more or less the same as what we commonly see in traditional research papers.

What Else Do We Need to Pay Attention to?

We discussed the major differences between action research and traditional research in the beginning of this article. Due to the difference in the focus of an action research report, the language style used may not be the same as what we normally see or use in a standard research report. Although both kinds of research, both action and traditional, can be published in academic journals, action research may also be published and delivered in brief reports or on websites for a broader, non-academic audience. Instead of using the formal style of scientific research, you may find it more suitable to write in the first person and use a narrative style while documenting your details of the research process.

However, this does not forbid using an academic writing style, which undeniably enhances the credibility of a report. According to Johnson (2002), even though personal thoughts and observations are valued and recorded along the way, an action research report should not be written in a highly subjective manner. A personal, reflective writing style does not necessarily mean that descriptions are unfair or dishonest, but statements with value judgments, highly charged language, and emotional buzzwords are best avoided.

Furthermore, documenting every detail used in the process of research does not necessitate writing a lengthy report. The purpose of giving sufficient details is to let other practitioners trace your train of thought, learn from your examples, and possibly be able to duplicate your steps of research. This is why writing a clear report that does not bore or confuse your readers is essential.

Lastly, You May Ask, Why Do We Bother to Even Write an Action Research Report?

It sounds paradoxical that while practitioners tend to have a great deal of knowledge at their disposal, often they do not communicate their insights to others. Take education as an example: It is both regrettable and regressive if every teacher, no matter how professional he or she might be, only teaches in the way they were taught and fails to understand what their peer teachers know about their practice. Writing an action research report provides you with the chance to reflect upon your own practice, make substantiated claims linking research to action, and document action and ideas as they take place. The results can then be kept, both for the sake of your own future reference, and to also make the most of your insights through the act of sharing with your professional peers.

Feldman, A., & Weiss, T. (n.d.). Suggestions for writing the action research report . Retrieved from http://people.umass.edu/~afeldman/ARreadingmaterials/WritingARReport.html

Johnson, A. P. (2002). A short guide to action research . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Marrow, A. J. (1969). The practical theorist: The life and work of Kurt Lewin . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Tiffany Ip is a lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University. She gained a PhD in neurolinguistics after completing her Bachelor’s degree in psychology and linguistics. She strives to utilize her knowledge to translate brain research findings into practical classroom instruction.

Research Proposal Example/Sample

Detailed Walkthrough + Free Proposal Template

If you’re getting started crafting your research proposal and are looking for a few examples of research proposals , you’ve come to the right place.

In this video, we walk you through two successful (approved) research proposals , one for a Master’s-level project, and one for a PhD-level dissertation. We also start off by unpacking our free research proposal template and discussing the four core sections of a research proposal, so that you have a clear understanding of the basics before diving into the actual proposals.

- Research proposal example/sample – Master’s-level (PDF/Word)

- Research proposal example/sample – PhD-level (PDF/Word)

- Proposal template (Fully editable)

If you’re working on a research proposal for a dissertation or thesis, you may also find the following useful:

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : Learn how to write a research proposal as efficiently and effectively as possible

- 1:1 Proposal Coaching : Get hands-on help with your research proposal

FAQ: Research Proposal Example

Research proposal example: frequently asked questions, are the sample proposals real.

Yes. The proposals are real and were approved by the respective universities.

Can I copy one of these proposals for my own research?

As we discuss in the video, every research proposal will be slightly different, depending on the university’s unique requirements, as well as the nature of the research itself. Therefore, you’ll need to tailor your research proposal to suit your specific context.

You can learn more about the basics of writing a research proposal here .

How do I get the research proposal template?

You can access our free proposal template here .

Is the proposal template really free?

Yes. There is no cost for the proposal template and you are free to use it as a foundation for your research proposal.

Where can I learn more about proposal writing?

For self-directed learners, our Research Proposal Bootcamp is a great starting point.

For students that want hands-on guidance, our private coaching service is recommended.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

I am at the stage of writing my thesis proposal for a PhD in Management at Altantic International University. I checked on the coaching services, but it indicates that it’s not available in my area. I am in South Sudan. My proposed topic is: “Leadership Behavior in Local Government Governance Ecosystem and Service Delivery Effectiveness in Post Conflict Districts of Northern Uganda”. I will appreciate your guidance and support

GRADCOCH is very grateful motivated and helpful for all students etc. it is very accorporated and provide easy access way strongly agree from GRADCOCH.

Proposal research departemet management

I am at the stage of writing my thesis proposal for a masters in Analysis of w heat commercialisation by small holders householdrs at Hawassa International University. I will appreciate your guidance and support

please provide a attractive proposal about foreign universities .It would be your highness.

comparative constitutional law

Kindly guide me through writing a good proposal on the thesis topic; Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Financial Inclusion in Nigeria. Thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Training and Development

- Beginner Guides

Blog Education

How to Write a Research Proposal: A Step-by-Step

By Danesh Ramuthi , Nov 29, 2023

A research proposal is a structured outline for a planned study on a specific topic. It serves as a roadmap, guiding researchers through the process of converting their research idea into a feasible project.

The aim of a research proposal is multifold: it articulates the research problem, establishes a theoretical framework, outlines the research methodology and highlights the potential significance of the study. Importantly, it’s a critical tool for scholars seeking grant funding or approval for their research projects.

Crafting a good research proposal requires not only understanding your research topic and methodological approaches but also the ability to present your ideas clearly and persuasively. Explore Venngage’s Proposal Maker and Research Proposals Templates to begin your journey in writing a compelling research proposal.

What to include in a research proposal?

In a research proposal, include a clear statement of your research question or problem, along with an explanation of its significance. This should be followed by a literature review that situates your proposed study within the context of existing research.

Your proposal should also outline the research methodology, detailing how you plan to conduct your study, including data collection and analysis methods.

Additionally, include a theoretical framework that guides your research approach, a timeline or research schedule, and a budget if applicable. It’s important to also address the anticipated outcomes and potential implications of your study. A well-structured research proposal will clearly communicate your research objectives, methods and significance to the readers.

How to format a research proposal?

Formatting a research proposal involves adhering to a structured outline to ensure clarity and coherence. While specific requirements may vary, a standard research proposal typically includes the following elements:

- Title Page: Must include the title of your research proposal, your name and affiliations. The title should be concise and descriptive of your proposed research.

- Abstract: A brief summary of your proposal, usually not exceeding 250 words. It should highlight the research question, methodology and the potential impact of the study.

- Introduction: Introduces your research question or problem, explains its significance, and states the objectives of your study.

- Literature review: Here, you contextualize your research within existing scholarship, demonstrating your knowledge of the field and how your research will contribute to it.

- Methodology: Outline your research methods, including how you will collect and analyze data. This section should be detailed enough to show the feasibility and thoughtfulness of your approach.

- Timeline: Provide an estimated schedule for your research, breaking down the process into stages with a realistic timeline for each.

- Budget (if applicable): If your research requires funding, include a detailed budget outlining expected cost.

- References/Bibliography: List all sources referenced in your proposal in a consistent citation style.

How to write a research proposal in 11 steps?

Writing a research proposal in structured steps ensures a comprehensive and coherent presentation of your research project. Let’s look at the explanation for each of the steps here:

Step 1: Title and Abstract Step 2: Introduction Step 3: Research objectives Step 4: Literature review Step 5: Methodology Step 6: Timeline Step 7: Resources Step 8: Ethical considerations Step 9: Expected outcomes and significance Step 10: References Step 11: Appendices

Step 1: title and abstract.

Select a concise, descriptive title and write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology and expected outcomes. The abstract should include your research question, the objectives you aim to achieve, the methodology you plan to employ and the anticipated outcomes.

Step 2: Introduction

In this section, introduce the topic of your research, emphasizing its significance and relevance to the field. Articulate the research problem or question in clear terms and provide background context, which should include an overview of previous research in the field.

Step 3: Research objectives

Here, you’ll need to outline specific, clear and achievable objectives that align with your research problem. These objectives should be well-defined, focused and measurable, serving as the guiding pillars for your study. They help in establishing what you intend to accomplish through your research and provide a clear direction for your investigation.

Step 4: Literature review

In this part, conduct a thorough review of existing literature related to your research topic. This involves a detailed summary of key findings and major contributions from previous research. Identify existing gaps in the literature and articulate how your research aims to fill these gaps. The literature review not only shows your grasp of the subject matter but also how your research will contribute new insights or perspectives to the field.

Step 5: Methodology

Describe the design of your research and the methodologies you will employ. This should include detailed information on data collection methods, instruments to be used and analysis techniques. Justify the appropriateness of these methods for your research.

Step 6: Timeline

Construct a detailed timeline that maps out the major milestones and activities of your research project. Break the entire research process into smaller, manageable tasks and assign realistic time frames to each. This timeline should cover everything from the initial research phase to the final submission, including periods for data collection, analysis and report writing.

It helps in ensuring your project stays on track and demonstrates to reviewers that you have a well-thought-out plan for completing your research efficiently.

Step 7: Resources

Identify all the resources that will be required for your research, such as specific databases, laboratory equipment, software or funding. Provide details on how these resources will be accessed or acquired.

If your research requires funding, explain how it will be utilized effectively to support various aspects of the project.

Step 8: Ethical considerations

Address any ethical issues that may arise during your research. This is particularly important for research involving human subjects. Describe the measures you will take to ensure ethical standards are maintained, such as obtaining informed consent, ensuring participant privacy, and adhering to data protection regulations.

Here, in this section you should reassure reviewers that you are committed to conducting your research responsibly and ethically.

Step 9: Expected outcomes and significance

Articulate the expected outcomes or results of your research. Explain the potential impact and significance of these outcomes, whether in advancing academic knowledge, influencing policy or addressing specific societal or practical issues.

Step 10: References

Compile a comprehensive list of all the references cited in your proposal. Adhere to a consistent citation style (like APA or MLA) throughout your document. The reference section not only gives credit to the original authors of your sourced information but also strengthens the credibility of your proposal.

Step 11: Appendices

Include additional supporting materials that are pertinent to your research proposal. This can be survey questionnaires, interview guides, detailed data analysis plans or any supplementary information that supports the main text.

Appendices provide further depth to your proposal, showcasing the thoroughness of your preparation.

Research proposal FAQs

1. how long should a research proposal be.

The length of a research proposal can vary depending on the requirements of the academic institution, funding body or specific guidelines provided. Generally, research proposals range from 500 to 1500 words or about one to a few pages long. It’s important to provide enough detail to clearly convey your research idea, objectives and methodology, while being concise. Always check

2. Why is the research plan pivotal to a research project?

The research plan is pivotal to a research project because it acts as a blueprint, guiding every phase of the study. It outlines the objectives, methodology, timeline and expected outcomes, providing a structured approach and ensuring that the research is systematically conducted.

A well-crafted plan helps in identifying potential challenges, allocating resources efficiently and maintaining focus on the research goals. It is also essential for communicating the project’s feasibility and importance to stakeholders, such as funding bodies or academic supervisors.

Mastering how to write a research proposal is an essential skill for any scholar, whether in social and behavioral sciences, academic writing or any field requiring scholarly research. From this article, you have learned key components, from the literature review to the research design, helping you develop a persuasive and well-structured proposal.

Remember, a good research proposal not only highlights your proposed research and methodology but also demonstrates its relevance and potential impact.

For additional support, consider utilizing Venngage’s Proposal Maker and Research Proposals Templates , valuable tools in crafting a compelling proposal that stands out.

Whether it’s for grant funding, a research paper or a dissertation proposal, these resources can assist in transforming your research idea into a successful submission.

- Section 2: Home

- Developing the Quantitative Research Design

- Qualitative Descriptive Design

- Design and Development Research (DDR) For Instructional Design

- Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Action Research Resource

What is Action Research?

Considerations, creating a plan of action.

- Case Study Design in an Applied Doctorate

- SAGE Research Methods

- Research Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- Dataset Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- IRB Resource Center This link opens in a new window