An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Res Involv Engagem

Research Buddy partnership in a MD–PhD program: lessons learned

Daniel j. gould.

1 Department of Surgery, St. Vincent’s Hospital, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC Australia

Marion Glanville-Hearst

Samantha bunzli.

2 School of Health Sciences and Social Work, Griffith University, Nathan Campus, Brisbane, QLD Australia

3 Physiotherapy Department, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Brisbane, QLD Australia

Peter F. M. Choong

4 Department of Orthopaedics, St. Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne, VIC Australia

Michelle M. Dowsey

Associated data.

Not applicable.

Background and aims

There is increasing recognition of the importance of patient involvement in research. In recent years, there has also been growing interest in patient partnerships with doctoral studies students. However, it can be difficult to know where to start and how to go about such involvement activities. The purpose of this perspective piece was to share experiential insight of the experience of a patient involvement program such that others can learn from this experience.

This is a co-authored perspective piece centred on the experience of MGH, a patient who has had hip replacement surgery, and DG, a medical student completing a PhD, participating in a Research Buddy partnership over the course of over 3 years. The context in which this partnership took place was also described to facilitate comparison with readers’ own circumstances and contexts. DG and MGH met regularly to discuss, and work together on, various aspects of DG’s PhD research project. Reflexive thematic analysis was conducted on reflections from DG and MGH regarding their experience in the Research Buddy program to synthesise nine lessons which were then corroborated with reference to published literature on patient involvement in research. These lessons were: learn from experience; tailor the program; get involved early; embrace uniqueness; meet regularly; build rapport; ensure mutual benefit; broad involvement; regularly reflect and review.

Conclusions

In this perspective piece, a patient and a medical student completing a PhD reflected upon their experience co-designing a Research Buddy partnership within a patient involvement program. A series of nine lessons was identified and presented to inform readers seeking to develop or enhance their own patient involvement programs. Researcher-patient rapport is foundational to all other aspects of the patient’s involvement.

Plain English summary

The importance of patient involvement in research is gaining recognition. Existing research centres, as well as those that are just getting started, need to find their own way to involve patients and community members. However, learning from the experience of others is crucial to ensure every effort is made to do this in a fruitful way. Therefore, we aimed to share our experience and provide a list of lessons learned to help other researchers and patients get started and work together effectively. Our research centre developed a framework for involving patients in joint replacement research. Part of this framework is a ‘Research Buddy’ program, where a research student partners with a patient so that the research they conduct is more relevant and applicable to the target population. In our case, the research student partnered with someone who had a hip replacement to develop and test a questionnaire for an interview study about artificial intelligence in shared decision-making. The student and patient worked together and wrote this perspective piece outlining nine lessons so readers can learn from their experience of this program. The lessons were: learn from experience, tailor the program, get involved early, embrace uniqueness, meet regularly, build rapport, ensure mutual benefit, broad involvement, regularly reflect and review. People interested in starting, or improving, their own patient involvement activities can learn from our experience. These lessons will need to be adapted to fit the purpose and unique situation of other researchers and patients who have different needs and circumstances.

Introduction

There is growing recognition of the importance of patient and public involvement and engagement in research [ 1 , 2 ]. However, it can be difficult to know where to begin and how to go about it. Sharing experiential knowledge is critical for different groups seeking to develop and deploy their own programs and strategies [ 3 ]. This is because a one-size-fits-all approach will not address the culture and context of the unique settings in which these programs take place [ 4 – 7 ]. Rather, strategies should be tailored to each unique setting [ 8 ]. An in-depth description of the experience of the patient involvement program in a particular context, including the nature of the program and the challenges overcome, provides others with ideas and examples they can modify to suit their own needs [ 1 , 3 , 9 ]. These other groups can read about the experience of others and possibly avoid some pitfalls while harnessing the strengths of the program. This is not intended to restrict creativity nor to provide a prescriptive roadmap, but rather to provide an experiential account of the nature of engagement in a particular setting and offer suggestions for ways in which engagement can take place.

In recent years, there has also been growing interest in efforts to involve patients in doctoral studies [ 5 , 10 – 17 ]. This presents a unique opportunity to instil recognition of the importance of patient involvement early in the career of researchers and equip them with the skills and experience to facilitate meaningful involvement. It simultaneously offers patients an opportunity to partner with researchers in this formative stage of their career as they develop their research interests and approach to research.

Aims and rationale

The aim of this perspective piece was for the first two members (DG and MGH) of a Research Buddy partnership (described below in the ‘Context’ section) to critically reflect on their experience of this involvement activity throughout the course of a MD–PhD program.

Through this reflective process, lessons learned through experience were consolidated such that they can be of benefit to others seeking to learn from this experiential insight as they establish or improve their own patient involvement programs [ 1 , 3 , 18 – 20 ]. We also provided a detailed description of the context in which this Research Buddy partnership took place, to provide readers with a more complete understanding of the way in which this context influenced the partnership such that readers can consider the nature of their own unique situation and how this might impact upon patient involvement efforts [ 21 ].

Overview of structure of this perspective piece

Definitions.

Theoretical Underpinnings.

- Method of Patient Involvement throughout MD–PhD program

Method of reflection in this perspective piece

Findings—Lessons Learned.

Definitions

The body of literature in the patient involvement space is fraught with complex and nuanced terminology [ 22 ]. Therefore, the purpose of this section is to clarify the terminology and definitions used. Influential stakeholder involvement literature, as well as recent publications, were reviewed to select widely-used and functionally relevant terminology for this perspective piece [ 1 , 22 – 33 ]. The other critical aspect of the rationale for selecting these terms and definitions was that they were agreed upon with the patient partner, MGH, as they accurately described the nature of her involvement.

Terms used in this paper include the following: patient, involvement, partnership, and co-design.

The term ‘patient’ was used because this perspective piece concerns involvement with patients as distinct from members of the public. While this term may invoke the image of an individual seeking care, in the context of involvement it also refers to individuals with experience of a health condition and its management [ 28 ], which in this case is total joint replacement surgery.

Building upon this is the definition of ‘involvement’, which is commonly accepted to refer to research done ‘with’ or ‘by’ patients rather than ‘for’, ‘to’, or ‘about’ them [ 30 ]. One specific type of involvement is the ‘patient partnership’, in which patients are embedded in various research activities at different levels and in multiple stages of the research process [ 1 ]. A particularly powerful example of a patient partnership is the Research Buddy program, which has been described previously as a program in which a doctoral student works closely with a patient throughout their project [ 13 ] and which was also described and reflected upon later in this perspective piece in the section ‘Method of Patient Involvement throughout MD–PhD program’.

Finally, the term ‘co-design’ was used in this piece to describe the active, voluntary process of researcher and patient partner working together on the design of a PhD project and its constituent studies, as this terminology is appropriate for the timeframe in which doctoral studies typically take place [ 22 , 32 – 35 ].

Theoretical underpinnings

Theory development was not an aim of this perspective piece. However, it is important to describe the theoretical underpinnings of the patient involvement program.

There are three main approaches to patient involvement in research: epistemological, consequentialist, and emancipatory or moral [ 33 , 36 , 37 ]. The epistemological approach recognises the fact that patients have lived experience of a health condition that can be of benefit to the research by broadening the perspective of researchers. The emancipatory approach recognises that patients have a right to be involved in publicly funded research that impacts upon them or the care they receive, and consequently researchers have a responsibility to involve patients. Finally, the consequentialist argument states that involvement can improve the design, conduct, and reporting of research.

Primarily, the emancipatory argument motivated the formation of the involvement program described in this perspective piece. Furthermore, patient involvement can lead to more ethically sound research [ 38 ], and this was recognised in the work reflected upon in this piece as MGH assisted DG in the ethics application process for the PhD research projects through document review. However, it was also recognised that the quality and relevance of research conducted at the research centre could be improved through involvement of a patient with lived experience of joint replacement surgery. Therefore, the consequentialist and epistemological arguments also underpinned the involvement program.

Recent literature has also advocated for a pragmatic approach to patient-oriented research by utilising patient involvement to ultimately improve health outcomes for affected individuals [ 39 ]. These authors recognised that achieving such impact is a complex task and, as such, mixed methods approaches to research are encouraged to harness the strength of both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies. This is particularly relevant to the current perspective piece, which describes patient involvement in a mixed methods PhD project on a topic of clinical relevance aimed to improve outcomes for patients.

Finally, the word ‘perspective’ was intentionally selected instead of the term ‘representative’ because it is unrealistic and unfair to ask a single patient with their own unique experience to generalise their experience to represent that of all patients with the same health condition. Rather, patient involvement was incorporated to broaden the perspective of the researchers while they co-designed research with the patient [ 36 , 40 ].

A detailed description of the context in which the patient involvement program took place facilitates comparison to one’s own context such that the potential applicability of a framework and experience can be considered in detail [ 6 , 7 ]. This is not intended to limit the generalisability of the findings reflected upon in this perspective piece. Rather, the specific context in which the patient involvement partnership and activities took place is described in detail such that readers can accurately compare this context to their own.

The patient involvement program described in this perspective piece took place in an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Centre for Research Excellence for Total Joint Replacement, seeking to O ptimise P atient o U tcomes and S election for Total Joint Replacement (OPUS). OPUS is embedded in a hospital in Melbourne, Victoria, which is a tertiary referral centre for total joint replacement (TJR), providing care for people from a broad range of geographical regions, socioeconomic backgrounds, and cultures [ 41 ]. OPUS brings together clinician-researchers with backgrounds in orthopaedic surgery, nursing, and physiotherapy, as well as trialists, epidemiologists, health economists, statisticians and qualitative researchers. It comprises researchers at various stages of their careers, including graduate research students.

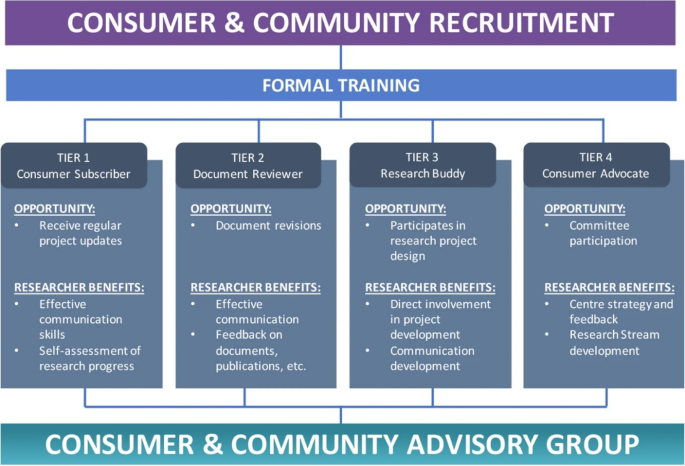

The patient involvement program at OPUS was developed and launched in 2020 and has been described previously [ 42 ]. The program involves a four-tiered framework of involvement (see Fig. 1 ). Table 3 of this prior publication also outlines the remuneration fee schedule according to which MGH was remunerated for her time. This prior publication used the term ‘consumer’, therefore, for consistency, this terminology is used below when describing the framework.

Proposed level of involvement for consumers and community members presents different opportunities of participation and the relevant benefits to researchers

This Figure was made available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

The Consumer and Community Advisory Group (bottom of Fig. 1 ) oversees the operations of the CCI program. It is chaired by a consumer (MGH, co-author on this paper).

This perspective piece details the experience of a Research Buddy, Tier 3 as shown in Fig. 1 , and an MD–PhD candidate at OPUS. An MD–PhD candidate is a medical student who takes time out from their clinical studies to complete a PhD. The details of this Research Buddy program are described in the next section.

Method of patient involvement throughout MD–PhD program

The Research Buddy program reflected upon in this piece took the approach of broadening the perspective of the research team by including the voice a patient with lived experience of a health condition [ 43 ]. This is distinct from an approach which would seek to achieve representativeness from one patient partner on behalf of all patients with a shared lived experience, which would be unrealistic [ 31 , 44 ].

The focus of this piece is on the Research Buddy partnership comprising authors DG and MGH. In this section, DG and MGH reflected upon their expectations prior to the commencement of the Research Buddy program and how their actual experience played out.

DG was a final-year postgraduate medical student in 2019, carrying out a research project on risk factors for readmission following total knee replacement (TKR) surgery. The opportunity arose to enrol in a PhD to expand upon this work, which led to the deferment of DG’s final year of medical school in order to complete a PhD as part of an MD–PhD program [ 45 ]. Building upon the research into risk factors for readmission following TKR, the PhD centred around the development of a clinical risk prediction tool utilising machine learning. DG, along with his PhD supervisors (authors MD, SB, and PC) felt that the strong clinical focus of the MD–PhD program would position it well for close involvement with a Research Buddy. MGH had previously participated, as a subject, in a study conducted by MD and PC investigating the impact of a mindfulness program on recovery post-surgery for patients undergoing total hip replacement (THR) [ 46 ]. MGH reached out to MD regarding the findings of the mindfulness study, coincidentally while MD was establishing the patient involvement framework at OPUS and seeking volunteers for the Research Buddy role. MGH subsequently embraced the opportunity and volunteered to be DG’s Research Buddy approximately 6 months after the official commencement of the PhD. MGH decided to take part specifically in DG’s project because she wanted to learn more about research, had a keen interest in artificial intelligence and machine learning and its application to lower limb joint replacement surgery, and has had a lifelong interest and involvement in academia. This presented a tangible opportunity to make a substantial impact on the direction of the research and cement its clinical, stakeholder-focused approach, and MGH felt her interests and experience aligned most closely with DG’s project [ 47 ].

During this formative stage of the PhD project, MGH and DG worked together to define the scope and structure of the Research Buddy program. There was a shared expectation of open-ended discussions and regular contact with updates on the research. Neither DG nor MGH had been involved in such a patient involvement partnership before, therefore they did not have rigid expectations about the manner in which the partnership would unfold. It was decided that regular monthly meetings would facilitate the development of rapport, ongoing discussion of ideas for the PhD project and opportunities for involvement its constituent studies, and the opportunity for regular updates on progress.

The first part of DG’s PhD project discussed in these meetings was the systematic review, which was in the manuscript drafting stage and benefited greatly from MGH’s input on the clarity of the language [ 48 , 49 ] and ensuring the pertinence and importance of the topic were clearly communicated. Patient involvement in systematic reviews has been reported extensively in the literature [ 32 , 50 – 52 ], and it was an opportunity for MGH to gain familiarity with the topic at the foundation of the PhD project. More broadly, the regular monthly meetings were critical in defining the overall scope and purpose of the PhD project. Specifically, during the early stages it was difficult to determine how to make the research more clinically relevant. MGH had a background in occupational therapy and medical anthropology and had previously been involved in qualitative interview projects in which she interviewed participants and coded transcripts. The idea of a qualitative study exploring the views of TKR patients on the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning for risk prediction in shared clinical decision-making was already being developed, and MGH felt this was a fitting opportunity to be involved given her personal journey as a patient and her prior academic and research experience. MGH was involved as a co-author on the qualitative study and made a substantial contribution by pilot-testing the interview guide, contributing to the reflexive thematic analysis, and preparing and editing the manuscript for publication.

Next, MGH reviewed all of the ethics approval application documents for the studies comprising DG’s PhD project. Not only did this improve the clarity of the documents in a similar way to MGH’s review of the systematic review manuscript, but it also led to the development of more ethically conscious research by incorporating a patient’s perspective into the application [ 38 ] and helped DG to clarify the way these studies related to one another and formed a cohesive program of research.

Beyond the specific elements in which MGH made a direct contribution, DG’s reflection upon the stakeholder involvement in the form of the Research Buddy program prompted a shift in focus from machine learning to enhance predictive performance of the TKR readmission prediction model, to stakeholder involvement and engagement in the whole process of developing clinical risk prediction models, including not only patients but also clinicians [ 29 , 53 ]. In light of this, thanks to MGH’s Research Buddy input, DG designed the PhD project with stakeholder involvement embedded throughout.

At the time of writing this perspective piece, the main studies of the PhD project had been completed and DG was in the final stages of thesis write-up following feedback provided by MGH on the first full draft. The overall focus of the PhD project is on co-design with stakeholders, inspired by the Research Buddy partnership with MGH and cemented by exploration of the literature [ 24 , 54 – 56 ].

The PhD project centres around the development of a machine learning model to predict 30-day readmission [ 57 ] in people undergoing TKA surgery years [ 58 , 59 ] for osteoarthritis (OA) [ 60 ], co-designed with clinicians and patients [ 61 ]. The project is divided into four components, each comprising at least one main study. While MGH’s involvement in the project overall has been outlined above, what follows is a brief description of each part of the PhD project as well as the level [ 29 ] and phase [ 62 ] at which MGH was involved. While a high level of involvement was aimed at from the early phases of each part of the PhD project, it is recognised that higher levels of involvement are not automatically more desirable [ 27 ] and, since some aspects of the project were already underway when MGH and DG commenced the Research Buddy program, flexibility and responsiveness to the realities of the circumstances were of utmost importance in deciding with MGH at what level she wanted to be involved.

- i. Level = Involve

- ii. Phase = Design and preparation, dissemination

- ii. Phase = Dissemination

- i. Level = Collaborate

- ii. Phase = Design and preparation, conduct and implementation, and dissemination

Rather than speaking for the patient, it is important for the patient to speak for themselves. Prior reflective work on patient involvement in doctoral research adopted this approach to great effect [ 5 , 14 ]. This piece was therefore co-written by MGH and DG, the two members of the inaugural Research Buddy partnership at OPUS.

Pertinent elements of the GRIPP2 (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public) checklist [ 70 ] were adhered to while writing this piece.

The experiential insight gained by DG and MGH through their involvement in the Research Buddy program was consolidated in regular meetings throughout DG’s PhD project. Additionally, DG and MGH conducted an informal interview using questions informed by prior literature in which patient advocates from various patient involvement programs in the UK were interviewed [ 9 ]. This interview was audio recorded and transcribed. The transcript was then analysed using reflective thematic analysis [ 71 ] in which themes were generated inductively by DG and MGH based on MGH’s responses to the questions in the interview, informed by their shared experience in the Research Buddy partnership. These themes were then synthesised and refined into lessons, inspired by prior patient involvement literature which has used thematic analysis in a similar way to generate lessons and recommendations [ 1 , 3 , 55 , 62 , 72 , 73 ].

A literature search was then carried out to identify literature reviews which contained lessons from, or recommendations for, patient involvement [ 1 , 5 , 13 , 15 , 28 , 35 , 62 , 74 , 75 ]. These reviews were used to corroborate the findings from our own inductive analysis and reflection.

DG and MGH derived these lessons by reflecting primarily on their experience in the Research Buddy program. However, MGH was embedded in various other patient involvement activities at the research centre (OPUS), therefore some of these lessons will be broadly applicable beyond Research Buddy partnerships. This will depend on the patient’s desired level of involvement, and it is advised that readers are flexible in their interpretation and implementation of these findings.

Findings: lessons learned

Lesson (1) learn from experience.

Don’t go in completely blind. Learn from the experience of others as much as possible. Bring in experienced patient partners, and researchers experienced in patient involvement, who can offer advice on promising avenues to explore as well as flagging those which are less likely to be fruitful. For example, as part of the Research Buddy program reflected upon in this perspective piece, Carol Vleeskens was consulted to conduct a training session attended by both MGH and DG. Carol was a co-author on the publication outline OPUS’ patient involvement framework [ 42 ] and has extensive experience in patient involvement [ 76 ]. MGH was then involved in preparing an orientation day for prospective patient partners at OPUS, which she also attended.

Another powerful resource is published work on the experience and appraisal of other researcher-patient partnerships sharing their experience [ 5 ].

This lesson is pertinent to consider both in preparation for partnering with patients in order to maximise the likelihood of success prior to launching involvement programs [ 8 , 13 , 48 , 77 ], as well as for ongoing appraisal and improvement of existing programs based on patient partner feedback [ 1 ].

Lesson (2) tailor the program

A one-size-fits-all approach does not work. Patient involvement programs should be bespoke. They should be tailored to the unique context of the research centre engaging the patients [ 5 , 78 ]. Learning from the work of others is critical for generating ideas about how one’s own program could take shape [ 78 ], but it is equally important to modify these programs so they are fit for purpose.

Tailoring the patient involvement program has been emphasised in prior literature as a critical component of fruitful involvement through the translation of general principles into context-specific systems and actions [ 4 , 5 , 8 , 15 , 35 , 74 ].

Lesson (3) get involved early

If possible, involve patients in discussions where ideas are generated for research projects. Allow ample time to include patients on ethics applications and governance approvals to ensure they can make a meaningful contribution to the research.

Integrating patient involvement in earlier stages of research helps to facilitate truly patient-led research. Based on the experience outlined in this perspective piece, there are two main ways in which this can be done. First, patient involvement can be embedded in the ongoing work of established research centres as well as the commencement of work at new research centres in order to identify research priorities and steer the direction of research activities [ 4 , 7 ]. Second, in the style of Research Buddy partnerships, patients can be partnered with PhD students in order to co-design the program of research in a meaningful way by embedding engagement and co-design at the beginning of the student’s project [ 19 ]. It is not difficult to imagine a pipeline in which researchers collaborate with patients to generate ideas and then these ideas are translated into PhD research projects with patients.

Having patients engaged at these different stages of idea-generation and research project design could have the added benefit of anticipating and addressing challenges likely to arise in complex research projects such that solutions can be suggested proactively [ 29 ].

Early involvement has been demonstrated or recommended numerous times in a diverse range of contexts and for different levels of involvement [ 5 , 7 , 15 , 28 , 35 , 43 , 75 ].

Lesson (4) embrace uniqueness

Patients bring a wealth of unique experience. They should be treated as individuals with their own unique characteristics, experience, and insight [ 79 ]. Embrace their unique skills and experience. Throughout regular meetings and correspondence, various aspects of the patient’s experience may enable them to bring a unique perspective to the research which researchers could not have anticipated.

Embracing uniqueness of patient partners has been found to encourage more inclusive stakeholder involvement by demonstrating a flexibility in the researchers and responsiveness to the individual needs, experiences, and preferences of people seeking to be involved [ 1 , 5 , 35 , 48 , 77 ].

Lesson (5) meet regularly

Meet regularly, right from the start, even in the absence of a clear idea of what to do in terms of exactly how the patient will be involved. The level and nature of involvement can be collaboratively defined through these regular meetings.

Be open to a variety of forms the patient’s involvement could take and be willing to engage in some trial and error. Some ideas will not pan out, and that is just part of the process. Be willing to persevere and adapt. For example, during the qualitative study conducted as part of DG’s PhD project, MGH attempted cross-coding of the qualitative interview transcripts using the coding framework being developed by DG and author SB. However, MGH found that her style of coding based her prior experience was not functioning as well as it had for previous projects. DG and MGH attempted different styles and continued to discuss their findings in their regular monthly meetings, however ultimately this cross-coding exercise was abandoned as it was becoming quite convoluted and MGH felt more comfortable discussing the transcripts and contributing to the discussions around the development of themes through reflexive thematic analysis.

Both DG and MGH had an openness that resulted in these meetings being fruitful beyond the pragmatic aspects of setting the research agenda and tracking progress; they were critical in building rapport. Even when there were no specific research updates, the regular meeting time was maintained and utilised for an opportunity to discuss topics related to the research.

Regular meetings are a critical component of impactful patient involvement programs reported in the literature [ 15 , 35 , 62 , 75 ] as they facilitates ongoing communication, continuous feedback, and strong rapport-building as expanded upon in Lesson 6.

Lesson (6) build rapport

Establishing trust and rapport is critical to the success of the program. Put in the time. Create an environment in which frank and open discussions are encouraged. Follow through on action items from meetings and email discussions. Respect the patient’s autonomy while supporting them in their role. Listen to the patient and take their feedback into account. Demonstrate to the patient how their input is influencing the research. This designated time to meet and talk openly was critical for building rapport, which is arguably the most important component of patient involvement to increase the likelihood of success [ 37 , 80 ]. The centrality of rapport to the overall success of patient involvement in research is reflected in the large volume of diverse literature recognising its importance [ 1 , 5 , 17 , 28 , 30 , 35 , 62 , 73 , 75 , 81 – 84 ].

Lesson (7) ensure mutual benefit

Patients are more engaged when there is something in it for them. Ensure the interaction is mutually beneficial. For example, patients might learn more about their condition, or the condition of those they care for, through the patient involvement program [ 85 ].

This pragmatic aspect of involvement has been recognised in the literature detailing meaningful and impactful involvement activities that recognise the importance of ensuring the involvement benefits the research, the researchers, and the patient partners themselves [ 1 , 19 , 35 , 62 , 75 , 83 ].

The nature of a successful patient involvement program, in which there is rapport, mutual respect, and open discussion, is associated with a certain degree of passive learning simply by the two parties being in contact with one another [ 85 ]. Without any specific educational component to the program, regular and open communication regarding a common focus in the context of a research centre or program can have the effect of educating the patient about research [ 53 ], and the researcher about the patient’s lived experience of their condition [ 72 , 86 ]. Patients may also learn more about their own condition, its management, and current research being done to further understanding about it [ 85 ].

Lesson (8) broad involvement

It is beneficial to have the patient embedded in the broader patient involvement activities at the research centre, not just the Research Buddy (or equivalent) program. This may enable the patient to participate in broad discussions about current research and setting the direction of future research.

This is important for contextualising the Research Buddy’s work and enhancing their understanding of the way in which it fits into the broader body of work being conducted at the research centre in which the program is taking place. This is not to say patient partners should be stretched beyond their limit, but rather that they are not forced to limit themselves to one project and instead are encouraged to broaden their perspective through opportunities to be involved in varying capacities in other research projects and activities depending on their interests and capacity [ 28 , 35 , 82 ].

Lesson (9) regularly reflect and review

It is not enough to have good intentions. Having a framework is also critical, but the patient’s role may evolve over time and ethical considerations related to their involvement also evolve. It is easy for the patient’s role to devolve into tokenism despite the best intentions [ 22 ]. Regular meetings incorporating feedback from patient partners on their involvement in the research are critical to ensuring the patient’s role as partner in the research is respected and maintained. This requires transparency on the part of the researcher regarding how the patient’s involvement is influencing the research. Researchers must also be open to feedback from patients that may indicate they are not satisfied with their involvement and adjustments to their involvement may be required.

One potential way in which the patient partnership can break down is for researchers to treat them less like partners in the research process and more like participants in quasi-qualitative research by simply calling upon patients to complete surveys or answer questions as if in a qualitative interview. This is problematic because patient involvement in research is distinct from qualitative research and must be treated as such, but vigilance and effort is required to maintain the boundaries between the two [ 22 ].

Beyond this specific problem, regular reflection and review are broadly applicable to every aspect of patient involvement to ensure the patient’s involvement is meeting expectations as these expectations evolve throughout the research project alongside changes in the patient’s capacity and interests.

Regular review is crucial to ensure ethical principles are being adhered to at all times as the patient’s role evolves. Circumstances change, both intentionally and unintentionally, so it is critical to have discussions specifically dedicated to reviewing the patient’s role and ensuring they are still meaningfully involved and ethical principles are adhered to [ 87 ]. There may be occasions on which the patient’s preconceived ideas need to be discussed and worked through.

Building upon the other lessons outlined in this perspective piece, rapport based on mutual respect, coupled with regular meetings, provide the structure and nurture the culture necessary to facilitate continuous feedback as well as regular designated touch points at which reflection and review can take place [ 5 , 13 , 28 , 35 , 62 , 74 , 75 , 83 , 87 ].

Summary of findings

In this perspective piece, a patient partner with lived experience of total joint replacement surgery (MGH) and a MD–PhD candidate (DG) reflected on their experience in a Research Buddy program throughout a PhD project. Their aim was to provide experiential insight such that other researchers and patient partners can learn from their experience as they develop and refine their own patient involvement programs. Inductive thematic analysis was applied to the transcript of an informal interview carried out between DG and MGH, informed by reflections from regular meetings throughout their Research Buddy partnership. Through this process, nine lessons were synthesised from their experience: Learn from experience, Tailor the program, Get involved early, Embrace uniqueness, Meet regularly, Build rapport, Ensure mutual benefit, Broad involvement, and Regularly reflect and review. These lessons were corroborated by published literature, and rapport was found to be the most important factor in successful patient involvement. Each of the remaining lessons either stem from and/or contribute to the development of rapport.

Contribution to the literature

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first perspective piece on patient partnership in a MD–PhD program. This builds upon prior work highlighting the positive impact of partnering medical students with patients to further their clinical education and broaden their perspective, while empowering patients through the opportunity to learn more about their own health condition and health service experience while sharing their experiential insight with future clinicians in a formative stage of their career [ 88 , 89 ]. It builds upon this by demonstrating how MD–PhD students, being situated at the interface between the research and clinical domains, can partner with patients in a fruitful way that has a meaningful impact upon their clinical development while also influencing the design, conduct, and reporting of the research. This was particularly noteworthy during DG’s PhD journey, most of which was undertaken during lockdowns imposed in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Regular contact with MGH was, for long periods of time, DG’s only patient interaction and therefore was crucial to maintaining patient contact [ 88 ] from a clinical perspective as well as working with MGH to develop solutions to convert various research activities to be entirely online [ 15 , 16 ].

Through regular meetings based on mutual trust and respect, largely comprising open discussion especially when there were no major research progress updates, building rapport was prioritised from the outset of the Research Buddy program. Since MGH and DG had the freedom to define the scope and nature of the program, they were able to emphasise the importance of this reciprocal relationship both through conversation as well as through document review, providing comments alongside DG’s PhD supervisors, which enabled MGH to provide a critical perspective on DG’s work. With strong rapport as the foundation and critical feedback encouraged throughout the research journey, MGH’s role as ‘critical friend’ was characterised and strengthened [ 10 , 17 ].

This perspective piece also builds upon exemplary prior work reporting a Research Buddy program [ 13 ] by being co-authored with the Research Buddy. This perspective piece conveyed lessons learned through a program which drew on elements of embedded consultation [ 5 , 13 ] and demonstrated flexibility in the level of involvement in various aspects of the PhD project in response to changes in MGH’s interests and capacity throughout the partnership [ 16 ].

Furthermore, while the PhD project reflected upon in this perspective piece did not strictly pertain to a digital health innovation nor to a full translational research innovation, a predictive model was developed which was intended for use in the clinical setting for shared clinical decision-making in orthopaedics. Therefore, MGH’s involvement throughout the project was critical for in laying a solid foundation for the development of a clinically relevant digital health innovation [ 90 , 91 ] primed for translation into the clinical setting [ 27 ] in orthopaedics, which is a clinical discipline in which patient involvement is gaining recognition and appreciation [ 26 ].

Implications of findings

The most impactful implication of the findings of this paper is that the description of the context in which the researcher-patient partnership took place, coupled with the co-authored lessons learned and experiential insight [ 3 ] offered through reflection by both members of the Research Buddy partnership, can be utilised by others [ 92 , 93 ]. Learning through experience and reporting these lessons along with a detailed description of the context in which they were learned [ 6 , 18 ] is an impactful outcome of its own [ 92 ]. This enables readers to inform their own involvement efforts, both when establishing involvement programs and refining them.

Through involvement, patients like MGH learn more about their health condition as well as the research that goes into the developments in management approaches and the way in which patients experience the healthcare system [ 85 ].

It is hoped that these findings can be of assistance to ongoing [ 11 , 12 ] and future patient involvement efforts to bring researchers and patients onto the same page from the outset of research projects [ 49 ].

Future directions

Evaluating impact.

The question of how best to evaluate impact of patient involvement is longstanding and complicated [ 48 , 77 ]. There have been many attempts over the years to answer this question [ 11 , 12 , 23 , 73 , 78 , 79 , 94 – 99 ], but it appears there is no single best approach to measuring the effectiveness, success, or impact of involvement [ 100 ], and perhaps such a measure will never exist. However, ongoing efforts to develop and validate consistent patient involvement evaluation measures are encouraged to facilitate the comparison of different involvement strategies and gain some indication of which might be the most promising in a given context, when resources are limited and ought to be allocated to the most promising strategy [ 101 ].

Exploring patient involvement in decision-making non-research patient involvement and empowerment

The research project reflected upon in this perspective piece centred around the development of a risk prediction tool intended to be used in the process of shared clinical decision-making. This perspective piece explored patient involvement in clinically-oriented research being carried out by a MD–PhD candidate, which positions it well for ongoing work exploring the role patients play in the shared clinical decision-making process [ 102 – 104 ], particularly as it pertains to the use of decision aids including predictive tools.

Further reading

Further reading is recommended for those seeking to expand their knowledge of different types of patient involvement in varied contexts in order to better understand how to initiate, or improve, their own patient involvement programs [ 32 , 40 , 105 – 148 ].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this perspective piece include the consistent and frequent contact between DG and MGH throughout the course of the PhD program, which facilitated widespread and deep involvement in various aspects of the research project and its constituent studies. This also facilitated continuous feedback and reflection through open discussion, which laid the foundation for the writing of this piece.

One potential limitation is that MGH may be regarded as a ‘professional’ patient partner, given her academic background. This may raise concerns about whether her perspective as a patient is diminished by her familiarity with academia and the research process. This was certainly an important consideration, especially considering MGH’s involvement spanned over 3 years and involved close and regular contact with DG. However, it was not a concern because regardless of how familiar MGH becomes with the research process, she will never lose her perspective as a patient who has lived experience of total joint replacement surgery [ 149 ].

In this perspective piece, a patient and a medical student completing a PhD reflected upon their experience co-designing a Research Buddy partnership within a patient involvement program. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time such a partnership has been written about within the context of a MD–PhD program, which is uniquely placed at the interface between the research and clinical domains. A series of nine lessons was identified and presented to inform readers seeking to develop or enhance their own patient involvement programs: learn from experience, tailor the program, get involved early, embrace uniqueness, meet regularly, build rapport, ensure mutual benefit, broad involvement, regularly reflect and review. Researcher-patient rapport is foundational to all other aspects of the patient’s involvement.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the work of Dr Tilini Gunatillake and Dr Michelle Lam in establishing the OPUS CCI program. We also acknowledge the work of Dr Elizabeth Nelson, Claire Weeden and Lauren Patten in leading, administering, maintaining, and expanding the program. MMD is supported by a University of Melbourne Dame Kate Campbell Fellowship. PFC holds a National Health & Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship (GNT1154203)

Abbreviations

| PhD | Doctor of philosophy |

| MD | Doctor of medicine |

| GRIPP2 | Guidance for reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public |

| OPUS | OPtimise Patient oUtcomes and Selection for Total Joint Replacement |

| TKR | Total knee replacement |

| THR | Total hip replacement |

Author contributions

DG and MGH conceptualised the manuscript and wrote the initial draft, with PFC, MMD, and SB providing intellectual content. All authors contributed to discussions in which the recommendations were synthesised and refined. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript prior to submission, and have all reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the manuscript and will work together to ensure questions relating to the accuracy and integrity of any part of it are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

No funding was received directly for this study. DG, MGH, and SB receive no funding. PFC had the following funding sources to declare: Royalties from Johnson and Johnson, Consultancy with Johnson & Johnson, Consultancy with Stryker Corportation (paid personally); Australian National Health & Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship (paid to institution), HCF Foundation, BUPA Foundation, St. Vincents Health Australia, Australian Research Council, (Grant support provided to institution for research unrelated to the current manuscript); Axcelda cartilage regeneration project, Patent applied for device, composition of matter and process (institution and personally). MMD had the following funding sources to declare: National Health and Medical Research Council, HCF Foundation, BUPA Foundation, St. Vincents Health Australia, Australian Research Council, (Grant support provided to my institution for research unrelated to the current manuscript).

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

DG, MGH, and SB have no competing interests. PFC has the following to declare: Chair, Research Committee, Australian Orthopaedic Association (now completed term); Emeritus Board Member Musculoskeletal Australia. MMD has the following to declare: Chair, Australian Orthopaedic Association Research Foundation, Research Advisory Committee.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Research Buddy

- Writing Assistant

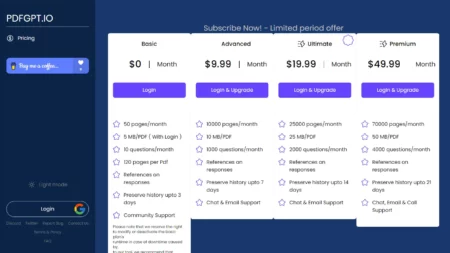

Pricing Model

Ai tool description.

Research Buddy is an innovative AI-powered tool designed to generate comprehensive Academic Literature Reviews in minutes.

With Research Buddy, users can quickly and easily type in a subject or research question, and generate a comprehensive literature review with Harvard referencing in minutes. The platform is ideal for those looking to stay up to date on a subject or issue before a meeting or class or generate a literature review for a research paper or thesis.

Research Buddy outputs to Word or PDF format, providing convenient export options for easy sharing and editing. The one-page executive summary is ideal for getting up-to-date on any subject or issue quickly before a meeting or class.

- Harvard referencing

- Comprehensive literature reviews

- One-page executive summary

- Outputs to Word or PDF format

Other related tools

Facial recognition and reverse image search for privacy and security protection.

Perplexity AI

AI-driven answer engine for complex questions.

Metaphor Systems

Search the internet creatively with large language models using Metaphor.

Selected AI Tools Direct to Your Inbox.

Join 100,000+ other Executives, Marketers, Developers & Founders

Spotlight: Nailedit (LLM Comparison) .

- My Saved AIs

Research Buddy

ResearchBuddy is an AI tool that automates the process of literature reviews. The tool helps researchers streamline their literature review process by presenting the most relevant information in a concise and easily digestible format.

Its intelligent algorithms help identify the most pertinent information in a given research field, saving hours of time and effort. Through its user-friendly interface, ResearchBuddy enables researchers to quickly and efficiently analyze large amounts of information, allowing them to focus on more critical aspects of their research.

The tool is designed to work with a wide range of research topics and is particularly useful in the fields of Science, Humanities and Social Sciences.

Its fully automated approach eliminates the need for manual intervention, reducing the possibility of errors or biases common in traditional literature reviews.

The tool can be accessed from anywhere, making it convenient for researchers to conduct virtual collaborations from different locations.ResearchBuddy helps researchers stay up-to-date with the latest research trends and findings.

The tool is backed by a team of experts who continuously update its algorithms and databases to ensure that the information presented is accurate and relevant.

Overall, ResearchBuddy provides an efficient and reliable method for conducting literature reviews and offers significant benefits to researchers in terms of saving time, effort and resources.

Community ratings

How would you rate research buddy.

Help other people by letting them know if this AI was useful.

Feature requests

54 alternatives to Research Buddy for Academic research

Most impacted jobs

Pros and Cons

If you liked research buddy, featured matches.

Other matches

People also searched

- Builder dashboard

Subscribe to our exclusive newsletter, coming out 3 times per week with the latest AI tools. Join over 470,000 readers.

To prevent spam, some actions require being signed in. It's free and only takes a few seconds.

Research Buddy

What is research buddy.

Research Buddy is an innovative AI-powered research assistant designed to help users efficiently gather information, analyze data, and generate insights. This powerful tool leverages advanced natural language processing and machine learning algorithms to streamline the research process and provide users with a comprehensive understanding of their topics of interest.

Top Features:

- Intelligent Search: Research Buddy's search functionality goes beyond traditional keyword matching, using semantic analysis to deliver highly relevant and contextual results.

- Summarization and Synthesis: The tool can quickly summarize large amounts of information, identifying key points and synthesizing insights to provide users with a concise understanding of their research topic.

- Collaboration and Sharing: Research Buddy allows users to easily share their findings and collaborate with others, facilitating seamless teamwork and knowledge sharing.

Pros and Cons

- Time-saving: Research Buddy significantly reduces the time and effort required to conduct research, allowing users to focus on analysis and decision-making.

- Comprehensive Results: The tool's advanced search capabilities and ability to synthesize information from multiple sources provide users with a well-rounded understanding of their research topic.

- Ease of Use: Research Buddy has a user-friendly interface and intuitive features, making it accessible to users of all skill levels.

- Potential Bias: Like any AI system, Research Buddy may be subject to biases in its training data or algorithms, which could influence the accuracy of its results.

- Dependence on Internet Connectivity: The tool requires a stable internet connection to function, which could be a limitation for users in areas with unreliable connectivity.

- Limited Customization: While Research Buddy offers a range of features, some users may desire more customization options to tailor the tool to their specific research needs.

- Academic Research: Students and researchers can use Research Buddy to quickly gather information, synthesize findings, and generate insights for their academic projects and papers.

- Business Intelligence: Professionals in various industries can leverage Research Buddy to gather market data, analyze trends, and make informed business decisions.

- Personal Knowledge Management: Individuals can use the tool to organize and synthesize information on topics they are passionate about, expanding their knowledge and understanding.

Who Can Use Research Buddy?

- Students: Research Buddy can greatly benefit students at all levels, from high school to graduate school, by streamlining their research process and helping them generate high-quality insights.

- Researchers: Academics and researchers in various fields can use the tool to efficiently gather information, collaborate with colleagues, and produce well-researched papers and reports.

- Professionals: Individuals working in fields such as business, marketing, consulting, and journalism can leverage Research Buddy to gather market intelligence, analyze trends, and make informed decisions.

- Free Trial: Research Buddy offers a free trial period, allowing users to explore the tool's features and functionality before committing to a paid plan.

- Pricing Plan: The tool offers various pricing plans based on the user's needs, with options for individuals, teams, and enterprises. Prices are competitive and offer good value for the features and functionality provided.

Our Review Rating Score:

- Functionality and Features: 4.5/5

- User Experience (UX): 4.2/5

- Performance and Reliability: 4.3/5

- Scalability and Integration: 4.1/5

- Security and Privacy: 4.4/5

- Cost-Effectiveness and Pricing Structure: 4.2/5

- Customer Support and Community: 4.0/5

- Innovation and Future Proofing: 4.6/5

- Data Management and Portability: 4.1/5

- Customization and Flexibility: 3.9/5

- Overall Rating: 4.3/5

Final Verdict:

Research Buddy is a powerful and innovative AI-powered research assistant that can significantly streamline the research process for users across various domains. Its intelligent search capabilities, summarization and synthesis features, and collaboration tools make it an excellent choice for anyone looking to efficiently gather information, analyze data, and generate insights. While it may have some limitations, such as potential biases and limited customization options, Research Buddy's overall performance, user-friendliness, and cost-effectiveness make it a valuable tool for students, researchers, and professionals alike.

1) What data sources does Research Buddy use?

Research Buddy accesses a wide range of online data sources, including academic databases, news articles, industry reports, and social media platforms. The tool uses advanced algorithms to gather and synthesize information from these sources, providing users with comprehensive and up-to-date research results.

2) Can Research Buddy be used for team collaboration?

Yes, Research Buddy offers collaboration features that allow users to share their findings, comment on each other's work, and work together on research projects. The tool's sharing capabilities make it easy for teams to stay organized and aligned throughout the research process.

3) How accurate are Research Buddy's results?

While Research Buddy's results are generally accurate and reliable, it's important to note that the tool's accuracy depends on the quality and accuracy of the data sources it uses. Users should always critically evaluate the information provided by Research Buddy and cross-reference it with other reliable sources before relying on it for important decisions.

4) Can Research Buddy be used for non-English languages?

At the moment, Research Buddy primarily supports English language research. However, the tool's developers are working on expanding its language capabilities to support other major languages in the near future.

5) Is Research Buddy secure and private?

Research Buddy takes user privacy and data security very seriously. The tool uses advanced encryption and security protocols to protect user data, and has a strict privacy policy that ensures user information is never shared or sold to third parties. However, users should always exercise caution when sharing sensitive information online.

Become the AI Expert of Your Office

Join 200,000 professionals adopting AI tools for work

- Bookmark 100s of AI tools that interest you

- Get personalized AI tool recommendations every week

- Free weekly newsletter with practical news, trending tools, tutorials and more

Research Buddy alternatives

Thumbmachine

Crypto Co-Pilot

Join 40,000+ subscribers including Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft employees reading our free newsletter.

Remember Me

Please enter your email address or username. You will receive a link to create a new password via email.

- I agree with the privacy policy

- Best AI Tools

Research Buddy

- Matthew Edwards

- Read reviews

- Create collection

- --> {{ item.title }}

- {{ item.label }}

About Research Buddy

Introducing ResearchBuddy, the ultimate AI-powered solution for hassle-free literature reviews. Designed to streamline the research process, our user-friendly platform grants researchers seamless access to a vast array of articles and papers. With ResearchBuddy, conducting literature reviews has never been easier.

Our cutting-edge technology enables ResearchBuddy to swiftly search and categorize an extensive range of scholarly content. By utilizing advanced algorithms, our tool effectively analyzes and extracts crucial information from articles, empowering researchers to swiftly pinpoint relevant sources. Furthermore, ResearchBuddy offers customization options through filters and tags, ensuring effortless organization and tracking of research findings.

Whether you are an aspiring student, a distinguished professor, or a seasoned industry professional, ResearchBuddy is an invaluable companion for comprehensive literature reviews. Our tool keeps you updated with the latest research in your field, ensuring you never overlook any seminal studies. Invest in ResearchBuddy today and revolutionize the way you conduct literature reviews.

Research Buddy image gallery

Research Buddy core features

❤ Automate literature review ❤ Search and categorize scholarly content ❤ Track research findings

Research Buddy use cases

#️⃣Keep yourself informed about the most recent research. #️⃣Reduce the amount of time and energy spent on literature reviews. #️⃣Easily access and evaluate articles that are relevant to your field. #️⃣Streamline the process of conducting literature reviews with automation. #️⃣Efficiently organize and monitor your research findings.

Authentic Links 🌍

- Official Website

Research Buddy pricing 👀

Dubformer.ai

- Audio Generation

- Advertising

- Customer Support

AI Job Description Generator

- Human Resources

- Image Generation

- Developer tools

GummySearch

Storydoc Pitch Deck

- Startup tools

There are no results matching your search.

Similar AI tools like Research Buddy

Mirrorthink

Lumina Chat

All Search AI

AlphaInquire

History Timelines

ContextClue

AcademicGPT

Color Pop AI

Paperade Startup Idea Generator

Branchminds

Connected Papers

PaperClipapp

AI Text Classifier

Research Buddy Reviews

- {{ order.label }}

No reviews available

Excellent 33%

Very good 67%

- Promote your tool

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Refund Policy

Research Articles

Enhancing Student-Student Online Interaction: Exploring the Study Buddy Peer Review Activity

- Colin Madland and

- Griff Richards

…more information

Colin Madland Thompson Rivers University, Canada [email protected]

Griff Richards Athabasca University, Canada [email protected]

Online publication: Dec. 6, 2019

An article of the journal International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning

Volume 17, Number 3, April 2016 , p. 157–175

Copyright (c) Colin Madland, Griff Richards, 2016

The study buddy is a learning strategy employed in a graduate distance course to promote informal peer reviewing of assignments before submission. This strategy promotes student-student interaction and helps break the social isolation of distance learning. Given the concern by Arum and Roksa (2011) that student-student interaction may be distracting from instead of contributing to academic achievement it was felt important to examine the way peer interaction can contribute to learning in a well-structured collaborative learning activity. This mixed-methods study (n=31) examined both quantitative and qualitative aspects of student perceptions of the study buddy activity. While quantitative findings regarding depth of processing were inconclusive due to the small and homogeneous sample, qualitative analysis showed very high levels of learner support for the activity as well as evidence that the activity encouraged learners to approach their learning with greater depth. 88% of study buddies said they found the activity well worth their time, and would recommend it for other graduate courses. It is thought with greater scaffolding, the quality of buddy feedback might be improved. The few who did not appreciate the activity felt let down by a lack of buddy commitment to the process.

- interaction,

- cooperative learning,

- critical thinking,

- study buddy,

- approaches to learning,

- learning design

Download the article in PDF to read it. Download

Citation Tools

Cite this article, export the record for this article.

RIS EndNote, Papers, Reference Manager, RefWorks, Zotero

ENW EndNote (version X9.1 and above), Zotero

BIB BibTeX, JabRef, Mendeley, Zotero

Research Buddy

What is Research Buddy?

Research Buddy is an AI tool that automates the process of literature reviews, helping researchers streamline their literature review process by identifying the most pertinent information in a given research field. It uses intelligent algorithms to present the most relevant information, saving hours of time and effort. The tool is designed to work with a wide range of research topics and is particularly useful in the fields of Science, Humanities, and Social Sciences. Research Buddy is accessible from anywhere, enabling researchers to collaborate virtually from different locations. The tool is backed by experts who continuously update its algorithms and databases to ensure accuracy and reliability.

⚡Top 5 Research Buddy Features:

- Automated Literature Reviews: Research Buddy uses AI technology to automate the process of literature reviews, helping researchers save time and effort.

- Intelligent Algorithms: The tool’s algorithms identify the most pertinent information in a given research field, ensuring accuracy and relevance.

- User-Friendly Interface: A simple and intuitive design, enabling users to easily navigate and analyze large amounts of information.

- Accessible Anywhere: The platform allows researchers to conduct virtual collaborations from different locations, increasing convenience and flexibility.

- Continuous Updates: Research Buddy’s team of experts regularly updates the algorithms and databases to maintain the quality and reliability of the information provided.

⚡Top 5 Research Buddy Use Cases:

- Academic Research: Research Buddy assists researchers in various fields by generating comprehensive literature reviews and providing valuable insights.

- Staying Updated: Users can stay informed about a subject or issue before a meeting or class by using ResearchBuddy’s one-page executive summary feature.

- Literature Review Generation: Research Buddy simplifies creating literature reviews for research papers or theses by automatically generating relevant information.

- Collaboration: The platform facilitates virtual collaboration among researchers, allowing them to share and discuss findings from different locations.

- Harvard Referencing: Get literature reviews in either Word or PDF formats, which can be easily shared and edited while maintaining proper citation styles.

View Research Buddy Alternatives:

CoolMindMaps

Collaborate on custom mind maps to organize ideas visually.

Stellaris AI

Advanced language models and analytics for pioneering solutions.

MonkeyLearn

contact for pricing

No-code text analytics platform for insights from feedback, surveys.

Generate insights and extract valuable information from data instantly.

Securely track, store documents in the cloud, cite sources easily.

Intelligent assistant for instant answers, knowledge gaps.

Simplify & distill lengthy documents to boost productivity.

Experience PDFs with light mode, login, bug reports, and more.

Organize digital life, capture ideas, manage tasks, and share with peers

Uncover customer problems, decide what to build, strategize.

Predictive algorithms for designing improved proteins.

Comprehensive resource hub for exploring AI advances.

© 2023 Powerusers, All Rights Reserved

Some of the links on this site may be affiliate links, and we may earn a commission if you purchase any of the products at no extra cost to you.

We use cookies to improve user experience. By using powerusers.ai you accept cookies

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of buddy in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- friend We've been friends for years.

- buddy He's one of my dad's old war buddies.

- pal The heartthrob was spotted hanging with his Hollywood pals in L.A.

- mate UK He's out with his mates.

- acquaintance

- acquaintanceship

- acquainted with someone

- contact list

- contemporary

- fair-weather friend

- non-contemporary

- office spouse

- on further acquaintance

- with friends like you, who needs enemies? idiom

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

buddy | American Dictionary

Examples of buddy, translations of buddy.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

knock someone down

to cause someone or something to fall to the ground by hitting him, her, or it

Fakes and forgeries (Things that are not what they seem to be)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun

- American Noun

- Translations

- All translations

To add buddy to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add buddy to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, what's a study buddy.

I've heard people mention having a 'study buddy' to help them with schoolwork. What exactly does that mean? Is this something I should look into?

A 'study buddy' is a term commonly used to describe a friend or classmate with whom you study regularly. The main idea behind having a study buddy is to enhance the learning experience by providing mutual support, sharing resources, and holding each other accountable. Study buddies can help you stay focused, motivated, and organized throughout the academic year.

There are several benefits to having a study buddy. Some of these include:

1. Improved understanding of the material: By explaining concepts to each other and working through problems together, you can gain a better grasp of the subject matter.

2. Keeping each other on track: Study buddies can help with time management by establishing study schedules and ensuring you stick to them.

3. Emotional support: A study buddy can offer encouragement during challenging times, like exam season or when tackling difficult assignments.

4. Learning new strategies: Study buddies often share effective study techniques, skills, or strategies that you may not have considered using before.

5. Networking: Forming a bond with a study buddy may lead to new connections and friendships both inside and outside the classroom.

You might consider finding a study buddy if you enjoy collaborative learning, find it hard to stay focused when studying alone, or just want to expand your academic support network. To maximize the benefits, try to find someone with a similar work ethic, learning style, and commitment to academics. That being said, every student is different, and what works for one person may not work for another. Ultimately, the decision to get a study buddy should be based on your personal preferences and learning style.

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

Advertisement

Making Meaning Together: Buddy Reading in a First Grade Classroom

- Published: 26 September 2010

- Volume 38 , pages 289–297, ( 2010 )

Cite this article

- Tori K. Flint 1 , 2

2088 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This study uses a Vygotskian approach and a socio-cultural lens, as well as the Transactional Reading Theory to investigate how social interactions and literary transactions can combine through buddy reading to empower young readers and promote literacy in a first grade classroom. The research focuses on how literary transaction and social interaction work together to facilitate emergent and early readers in a ‘partner/buddy’ reading approach. The research question asked whether or not ‘partner/buddy’ reading can promote literacy through social interaction, and yielded three major themes, including the use of reading strategies to scaffold learning, making connections with and to the text in order to construct meaning, and using play as a type of social interaction and motivational method. The findings suggest that buddy reading as a classroom tool can effectively promote literacy and learning in a cooperative setting.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Facilitating Reading Habits and Creating Peer Culture in Shared Book Reading: An Exploratory Case Study in a Toddler Classroom

“reading is social”: dialogic responses to interactive read-alouds with nonfiction picturebooks.

How Second-Grade English Learners Experienced Dyad Reading with Fiction and Nonfiction Texts

Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. (1996). Tools of the mind: The Vygotskian approach to early childhood education . Columbus, OH: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Christie, J. F., & Roskos, K. A. (2009). Play’s potential in early literacy development. In: R. E. Tremblay, R. G. Barr, R. De V. Peters, M. Boivin (Eds.), Encyclopedia on early childhood development [online]. Montreal, Quebec: Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development:1–6. Available at: http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/documents/Christie-RoskosANGxp.pdf . Accessed [April 2010].

Cochran-Smith, M. (1984). The making of a reader . Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

Cronin, D. (2000). Click, clack, moo: Cows that type . New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Griffin, M. L. (2002). Why don’t you use your finger? Paired reading in first grade. The Reading Teacher, 55 (8), 766–774.

Hubbard, R. S. & Power, B. M. (1993, 2003). The art of classroom inquiry: A handbook for teacher researchers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

MacGillivray, L., & Hawes, S. (1994). “ I don’t know what I’m doing-they all start with B”: First graders negotiate peer reading interactions. The Reading Teacher, 48 (3), 210–217.

Masurel, C. (2000). Ten dogs in the window: A countdown book . Croton on Hudson, NY: North-South Books (Houghton Mifflin Big Book Series).

Rosenblatt, L. M. (2001). The literary transaction: Evocation and response. Theory into Practice, XXI (4), 268–277.

Shannon, D. (1998). No David! New York, NY: Scholastic Publishing.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Skyline Ranch K-8, 1084 W. San Tan Hills Drive, San Tan Valley, AZ, 85143, USA

Tori K. Flint

Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, 85287, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tori K. Flint .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Flint, T.K. Making Meaning Together: Buddy Reading in a First Grade Classroom. Early Childhood Educ J 38 , 289–297 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-010-0418-9

Download citation

Published : 26 September 2010

Issue Date : December 2010

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-010-0418-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social interactions

- Literary transactions

- Buddy reading

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- The Oxford Review DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion) Dictionary /

Buddy System – Definition and Explanation

Understanding the Buddy System in the Workplace: Fostering DEI

In the realm of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI), the buddy system emerges as a powerful tool for fostering a supportive and inclusive workplace culture.

Definition:

The buddy system in the workplace refers to a structured approach where new employees are paired with existing employees, often referred to as “buddies” or mentors, to facilitate their integration into the company culture, processes, and workflows. This system aims to provide support, guidance, and a sense of belonging to newcomers, thereby enhancing their overall experience within the organisation.

Significance:

The buddy system plays a pivotal role in advancing DEI initiatives within organisations. By pairing individuals from diverse backgrounds as buddies, companies create opportunities for cross-cultural exchange, empathy building, and understanding. This fosters an inclusive environment where differences are celebrated, and employees feel valued irrespective of their background, ethnicity, or identity.

Implementation: