Money or Education, Which is More Important/Better? (Debate)

- Post author: Edeh Samuel Chukwuemeka ACMC

- Post published: March 3, 2024

- Post category: Scholarly Articles

Money or Education, Which is more Important? (Debate): So, which is more valuable: education or money? Which one should we concentrate on? This appears to be a simple question, but when we think about it, the answer is not that straightforward. Money and education are inextricably linked in our daily lives. On the one hand, money is what drives the majority of our lives.

We have to think about money in practically every decision we make. Education, on the other hand, cannot be overlooked since it provides us with the fundamental tools we require to live. Let’s weigh in on their relative importance and see if we can finally settle this age-old argument.

Recommended: Advantages and Disadvantages of studying abroad

Table of Contents

Why Money is Important

Money is commonly said to be “ not the most important thing in the world.” However, for many individuals, it is right up there with oxygen in terms of significance. These aren’t necessarily materialistic individuals. They just recognize the genuine worth of money.

Money isn’t exciting on its own. What matters is what money can accomplish for you. You have more flexibility and options when you have money. When you have a strong salary or financial resources, you have the freedom to choose where and how you wish to live. When you don’t have much money, on the other hand, making choices may be something you can’t afford. In actuality, the choices available to you may not be choices at all.

Also see: Most profitable skills to learn this year

Undoubtedly, you’ll require money to meet your fundamental needs, which include food, clothes, and shelter. Because of a lack of funds, a poor individual is frequently forced to make compromises even on essential basic requirements. Moreover, medical expenditures nowadays consume a person’s whole life savings. Furthermore, one must have money to obtain an education, as the cost of school is quite expensive these days and is not likely to decrease anytime soon.

While money cannot purchase happiness, it may give you independence, stability, and the ability to follow your aspirations. As a result, money is unquestionably necessary for every excellent thing that provides us financial satisfaction.

Recommended: How to spend less and save more

Why Education is Important

Today, education is more vital than ever before, and it has reached new heights as people have a better knowledge of what it comprises. If you ask yourself, “Why is education important?” your response will almost certainly not be the same as everyone else’s. While having a college degree is tremendously important for a successful profession and is socially acceptable in today’s culture, it is not the sole source of education. In everything we do, education is all around us.

Education may help you become the greatest, most complete version of yourself by allowing you to learn about what interests you, what you’re excellent at, and how to become self-aware and aware of the world around you. It can assist you in finding your position in the world and making you feel whole. Basic life skills and street smarts are built on the foundation of education. While education may appear to be a technical phrase, it refers to all we learn in life on how to live our lives to the fullest. When it comes to being creative in any manner, shape, or form, the mind can only achieve its full potential if it’s given the tools to think outside the box.

Education gives you a sense of stability in life, which no one can ever take away. You boost your prospects of greater professional options and create new doors for yourself by being well-educated. Education gives financial security in addition to stability, which is very important in today’s culture. An excellent education is more likely to lead to a higher-paying career and provide you with the necessary skills. It might provide you with the freedom to make your own decisions as well as be financially independent. Education has the potential to be the most liberating and empowering thing in the world.

Recommended: How to become a successful business entrepreneur

Money vs Education, Which is More Important

Money is required for basic expenses, but that is not the only requirement. Money helps us reach our objectives and support the things we care about most, such as family, education, health care, charity, adventure, enjoyment, and so on. It assists us in obtaining some of life’s intangibles, such as freedom or independence, as well as the opportunity to maximize our abilities and talents. It allows us to chart our path in life. It ensures financial safety. Much good may be accomplished with money, and unnecessary suffering can be prevented or eliminated.

Education, on the other hand, is essential for survival. Everyone needs education at some point in their lives to improve their knowledge, manner of life, and social and financial standing. Although it may not provide you with financial standing in society, a literate mind will undoubtedly set you apart. Education is amazing in that it is not restricted by age.

While money gives us the ability to make a difference in our own lives and the lives of others, it is impossible to obtain an education without it. The cost of education is quite expensive these days, and it will continue to rise in the near future. Education may be too expensive, particularly at private institutions and universities. While you don’t have to pay back your student loans until after you graduate, the payment will ultimately come due. Without funding, education would come to a halt.

Also see: Best side hustles for teachers to make extra money

In a different light, money may be able to buy what you “ desire ,” but education helps you to realize what you “need” to live a better life. This is demonstrated by the numerous non-monetary advantages that may be obtained via education. Money may allow us to have more control over our lives, but it is education that allows us to contribute to society. Although money is useful, an educated individual understands how to make money in the first place. Education has the potential to open up job opportunities.

With an education, you have the potential to earn more money than others who do not. Obtaining a degree might expand your options in some professions, allowing you to make more money. Many employers provide educational incentives to their workers. Anyone who stays up with current trends will always be able to make more money. If you are well educated, your chances of living in poverty are lower.

Furthermore, you cannot lose or be stripped of your education. Whatever happens, the lessons you’ve learned will be with you. Even if you lose a wonderful job, your degree and experience will assist you in finding work in the future. When a financial catastrophe strikes, you can’t lose what you’ve learned. Even if you become indebted due to unforeseen circumstances, your education will not be taken away from you.

Nevertheless, much of the narrative about the benefits of going to college and having a degree is centred around the concept that if you have a degree, you’ll be able to make more money. For many people, education is only a means to an end, which is monetary gain.

Some believe, however, that if generating money is your primary incentive for pursuing a profession, you might explore trade schools and other qualifications that may help you earn a fair living. After all, while many people dismiss trade skills such as plumbing and electrical labour, these individuals may amass money more quickly than their more educated counterparts. We frequently read about people who have amassed enormous wealth while having had very little formal education. In fact, having a degree does not ensure that you will earn more since many people without a degree make more money than graduates.

Regardless, education will assist you in developing a decent character, a noble personality, and, above all, will help you become a better person. You will not only be able to make money with education, but you will also be able to efficiently use the money you have made to benefit yourself and others. Money is a slippery slope, but those who figure out what they genuinely value and match their money with those beliefs have the most financial and personal well-being. Education is necessary to become such a person. Never forget that knowledge is power.

Recommended: Countries with the best education system in the world

Money vs Education is a perennial debate. The common view of money and education in our lives has been emphasized in this article. Everyone, after all, has their unique point of view.

Edeh Samuel Chukwuemeka, ACMC, is a lawyer and a certified mediator/conciliator in Nigeria. He is also a developer with knowledge in various programming languages. Samuel is determined to leverage his skills in technology, SEO, and legal practice to revolutionize the legal profession worldwide by creating web and mobile applications that simplify legal research. Sam is also passionate about educating and providing valuable information to people.

This Post Has 4 Comments

Money is important but education is far more important cuz money is the root to all evil while education is power

Money or education which is more important?

Education is the best, only to those who value it and know how to make use of it Education can bring money, but money at the other side can never bring education Even, a renown people in this world are educated.

Comments are closed.

DEBATE TOPIC: Education is Better than Money ( Support and Oppose the motion)

Explore the ongoing debate about whether education holds more value than money . This comprehensive article delves into the advantages of education, its impact on personal growth, and the role of money in achieving success.

In the eternal debate of education is Better than Money, both sides have valid points to consider. Education and money are undeniably powerful tools that can significantly influence our lives. While money enables us to access resources and opportunities, education equips us with knowledge and skills for personal and professional growth. Let’s delve into the depths of this debate and understand how education can be perceived as more valuable than money in various aspects of life.

DEBATE: Education is Better than Money

In this section, we’ll explore the reasons why education holds a distinct advantage over money and how it contributes to personal development, societal progress, and long-term success.

1. Lifelong Learning for Personal Growth

Free download now.

Education is a journey that doesn’t end with graduation. It fosters continuous learning and intellectual curiosity, allowing individuals to evolve and adapt to changing circumstances. With education, you gain the ability to think critically, analyze situations, and make informed decisions, which are essential for personal development.

2. Knowledge as an Asset

While money can be spent and lost, knowledge is an asset that grows over time. Acquiring education ensures that you have a valuable resource that can never be taken away. It empowers you to innovate, solve problems, and contribute meaningfully to society.

3. Empowerment and Self-Confidence

Education instills a sense of empowerment and self-confidence. When you’re well-educated, you’re equipped to face challenges head-on, communicate effectively, and pursue your passions with conviction. This self-assuredness is a priceless asset in both personal and professional spheres.

4. Shaping Critical Life Skills

Education goes beyond academic subjects; it imparts life skills such as communication, time management, and teamwork. These skills are fundamental for success in any field and play a crucial role in building well-rounded individuals.

5. Fostering Innovation

Innovation is at the heart of progress. Education fuels innovation by encouraging you to question the status quo, explore new ideas, and develop groundbreaking solutions to real-world problems.

6. Social Impact and Empathy

Education enhances your understanding of diverse cultures, perspectives, and societal issues. This broader awareness fosters empathy and a sense of responsibility towards making positive contributions to the community.

7. Long-Term Career Success

While money can provide short-term gains, education paves the way for sustained career success. It opens doors to better job opportunities, higher earning potential, and the ability to adapt to changing industries.

8. Wealth of Experience

An educated individual accumulates a wealth of experiences through learning, which enriches their life journey. These experiences contribute to personal growth, relationships, and a deeper appreciation of the world around them.

9. Redefining Success

Success is often equated with financial prosperity, but education challenges this notion. It encourages you to define success based on personal fulfillment, contribution to society, and the positive impact you make.

10. Enabling Social Mobility

Education is a powerful tool for social mobility. It provides opportunities for individuals from diverse backgrounds to overcome socioeconomic barriers and achieve their aspirations.

FAQs about the Debate “ Education is Better than Money”

Q: does education guarantee financial success.

Education enhances your skill set and knowledge, increasing your potential for higher earning opportunities. However, financial success depends on various factors, including market demand and personal choices.

Q: Can money buy happiness?

Money can provide comfort and security, but true happiness often stems from fulfilling relationships, meaningful experiences, and a sense of purpose, which education can contribute to.

Q: Is it wise to pursue education without considering earning potential?

While education enriches your understanding of the world, considering potential career prospects is essential to ensure financial stability and a well-rounded life.

Q: How can one balance educational debt with financial goals?

Striking a balance between repaying educational debt and saving for the future requires prudent financial planning and budgeting skills, emphasizing the importance of both education and financial stability.

Q: Can wealth be amassed solely through formal education?

While education provides a foundation, financial success often involves additional factors such as entrepreneurship, investment strategies, and adapting to market trends.

Q: Is philanthropy achievable without substantial wealth ?

Philanthropy is not exclusive to the wealthy. Even modest resources, combined with a commitment to positive change, can contribute to meaningful philanthropic endeavors.

The debate “Education is Better than Money” encapsulates the dynamic interplay between intellectual growth and financial prosperity. As this discourse unfolds, it becomes evident that both education and money hold their own distinct value and significance. The key lies in harnessing the potential of education to make informed financial decisions and leveraging financial resources to create a positive impact on oneself and society.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

What Is More Powerful? Education vs Money

21 april, 2020 , read more education.

We can give your business a digital turnover! Get your Ad published on our website for absolutely free.

© Copyright 2020-2022 BLOG SURVEYTOEARN. All rights reserved.

Why money matters for improving education

Subscribe to global connection, emiliana vegas emiliana vegas former co-director - center for universal education , former senior fellow - global economy and development @emivegasv.

July 21, 2016

For at least four decades, economists have analyzed the relationship between per student spending and learning outcomes across the United States and, more recently, across countries around the world. In 1996, as a result of a Brookings conference, the influential book “Does Money Matter?: The Effect of School Resources on Student Achievement and Adult Success ” was published, edited by economist Gary Burtless and with contributions from several well-known economists. The book focuses on the puzzle between research evidence from the U.S. that found that more resources did not necessarily result in improved student achievement and evidence showing that students who attend well-resourced schools end up having better outcomes later in life than students who attend poorly-endowed schools.

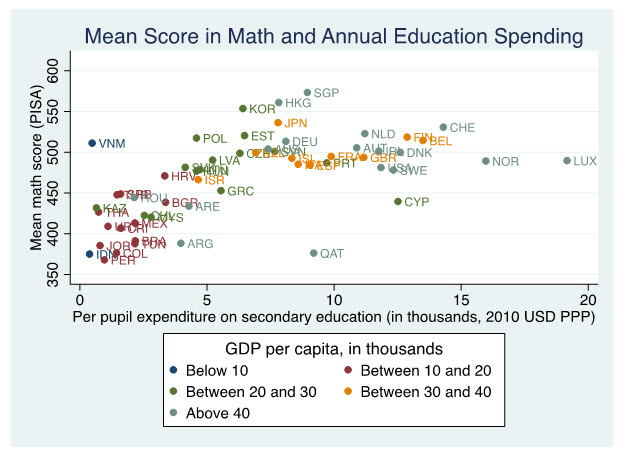

Indeed, a simple correlation analysis using cross-country data suggests that there is at best a weak relationship between student achievement and education spending. In other words, when comparing per pupil spending and average learning outcomes per country, we find that countries with similar levels of spending per student also show enormous differences in how much their students learn. Figure 1 shows the simple correlation between mean scores in math in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA, and per pupil spending in secondary education for each of the countries that participated in PISA 2012. It is easy to see that students in countries like Qatar and Singapore, which spend similar amounts of dollars per student, achieve vastly different PISA math scores.

Figure 1: Per pupil spending and mean math scores in PISA 2012, by country

Source: Vegas and Coffin, 2015 .

Working in developing countries throughout my career, I was always struck by the weak relationship between spending and outcomes. While, it was clear that differences in student learning between countries with similar spending levels, such as Qatar and Singapore, support the leading argument that how money is spent in education is more important than how much , I wondered whether this was only the case for countries that spend above a minimum level—a level that guarantees a minimum standard of basic inputs to ensure adequate learning opportunities for all.

Could in fact countries that spend little on education achieve good learning outcomes by simply spending more efficiently?

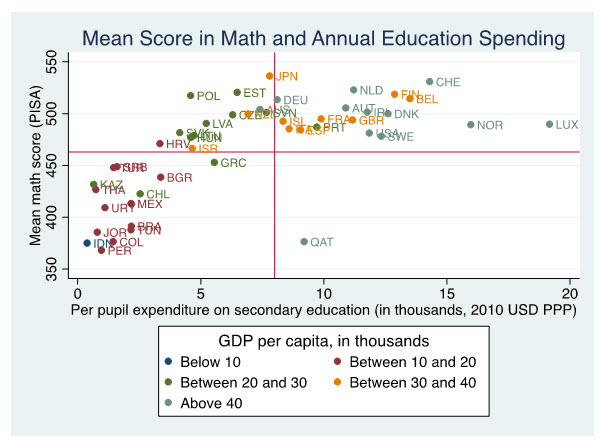

With my colleague Chelsea Coffin, I set out to explore the relationship between per pupil spending and learning, particularly in developing countries that spend much lower levels in education than do OECD countries. To do this, we separated countries that have participated in PISA into two groups based on their level of per pupil expenditure: a low-spending group, comprised of countries that spend less than a certain threshold per student; and a high-spending group, which included the countries that spend more than that threshold. Then, we designed separate regressions to estimate the relationship between spending and student learning (as measured by PISA) within these two groups of countries. We wanted to see if, among the low-spending group, more spending is associated with higher outcomes. Additionally, we wanted to estimate the per pupil spending level at which more money no longer can be associated with higher learning outcomes.

Put simply, our underlying hypothesis was that if Haiti only spends $100 per student, common sense suggests that it cannot reach the average learning levels of OECD countries that spend much more per student. However, does the country need to increase spending to the U.S. level ($11,732) or Finland’s level ($9,353) in order for their students to be able to learn the basic skills necessary compete in today’s global economy?

Our findings, reported in the Comparative Education Review suggest that, when education systems spend above $8,000, the association between student learning and per student spending is no longer statistically significant. Therefore, we find a threshold effect after this level of resources is met, indicating a declining relationship between resources and achievement at high levels of expenditure (consistent with other recent literature). This can be seen in Figure 2, where there is a positive relationship between student learning and per pupil expenditure among the low-spending countries (below $8,000 per student), but a flat relationship among high-spending countries.

Figure 2: Per student expenditures and mean math scores, separating low- from high-spending countries

One interpretation of our analysis, consistent with prior studies, is that efficient spending is more important among systems that already provide the basic inputs necessary for a quality education (as measured by their average spending per pupil). High spenders might also spend more on programs that compensate for students with disadvantaged backgrounds, helping mitigate inconsistent gains in test scores or proficiency. But when low spenders increase expenditure, it may be used to establish basic conditions or increase quality to a minimum standard, although efficient use of these resources may also be a constraint to achieve high levels of learning for all.

Our findings are also important in light of another strand of the economics literature. Research on the factors that explain differences in student learning has empirically demonstrated that, from the school side, high quality teachers (as measured by teachers’ capacity to generate learning in their students, or teacher value-added) are the most important determinant of student learning (See Hanushek 2011 , Hanushek and Kain 2012 , and Chetty et al 2014a and 2014b ). Influenced by this evidence, international organizations have prioritized attracting, motivating, and retaining talented teachers as a means to improving learning outcomes. And, like in any other profession, compensation matters. Unfortunately, only in a few countries is teaching a truly competitive career for talented professionals.

In short, improving education outcomes in Latin America and the Caribbean requires more and better investment. These countries still need to increase overall spending for education in order to provide the basic learning inputs to students. More importantly, in too few if any countries in Latin America is teaching a valued profession that attracts the most talented individuals. While some countries have introduced bold reforms to improve teaching conditions, attract better professionals, and set up teacher evaluation systems to guide teaching practices, much more remains to be done to ensure that all Latin American students have access to effective teachers.

Global Education

Global Economy and Development

The Brookings Institution, Washington DC

8:30 am - 4:30 pm EDT

Thinley Choden

May 3, 2024

Ghulam Omar Qargha, Rachel Dyl, Sreehari Ravindranath, Nariman Moustafa, Erika Faz de la Paz

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

School Money

Can more money fix america's schools.

Cory Turner

Kevin McCorry

Sarah Gonzalez

Kirk Carapezza

Claire McInerny

Week 2: Can More Money Fix America's Schools?

This winter, Jameria Miller would often run to her high school Spanish class, though not to get a good seat.

She wanted a good blanket.

"The cold is definitely a distraction," Jameria says of her classroom's uninsulated, metal walls.

Her teacher provided the blankets. First come, first served. Such is life in the William Penn School District in an inner-ring suburb of Philadelphia.

The hardest part for Jameria, though, isn't the cold. It's knowing that other schools aren't like this.

Before her family moved closer to the city, where they could afford more living space, she attended the more affluent Upper Moreland district, which is predominantly white and, according to state and local records, spends about $1,200 more per student than William Penn.

That difference adds up, Jameria says, to better buildings, smaller class sizes, take-home textbooks and less teacher turnover.

"It's never going to be fair," she says, comparing her life now to her former classmates. "They're always going to be a step ahead of us. They'll have more money than us, and they'll get better jobs than us, always."

The Miller family sits in the living room of their home in a Philadelphia suburb. They are part of an ongoing lawsuit, arguing Pennsylvania has neglected its constitutional responsibility to provide all children a "thorough and efficient" education. Emily Cohen for NPR hide caption

The Miller family sits in the living room of their home in a Philadelphia suburb. They are part of an ongoing lawsuit, arguing Pennsylvania has neglected its constitutional responsibility to provide all children a "thorough and efficient" education.

So Jameria's parents have signed onto a lawsuit, arguing that Pennsylvania's school funding system is unfair and inadequate. To the Millers, money matters.

But not everyone agrees.

"It's not about the dollars," says Stan Saylor, chairman of the education committee in Pennsylvania's House of Representatives. "It's where that local school district spent those dollars over the last many years."

And Saylor is not alone.

About The 'School Money' Project

School Money is a nationwide collaboration between NPR's Ed Team and 20 member station reporters exploring how states pay for their public schools and why many are failing to meet the needs of their most vulnerable students. This story is Part 2 of 3. Join the conversation on Twitter by using #SchoolMoney .

"Money isn't pixie dust," declared the Texas assistant solicitor general, arguing his state's side of a school funding lawsuit before the Texas Supreme Court. "Funding is no guarantee of better student outcomes."

This idea, that sprinkling more dollars over troubled schools won't magically improve test scores or graduation rates, is a common refrain among many politicians, activists and experts. And they have research to back it up.

This report on school spending from the libertarian Cato Institute is just one entry in a decades-long body of work that suggests there is little to no link between spending and academic achievement. And so, again ...

"Use the money you have more wisely and educate our children," says Jon Caldara of Colorado's Independence Institute, a free-market think tank.

In short, these critics say, it's How You Spend School Money, not How Much You Spend .

This debate has raged for at least half a century, and today we're going to put both sides under a microscope.

What follows here, as with the first installment in the School Money series, is a wrap-up of our reporting. For nearly every name and place, you'll find a hyperlink to more.

Like this story, for Jameria Miller.

Last week, we explored the question, "How do we pay for our public schools?"

This week, we ask: "What difference can a dollar make in our schools?"

Or, better yet, "Is money pixie dust?"

The answer begins in a place not known for magic: Congress.

The Coleman Report

Section 402 of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 is short, just a paragraph long, but it demanded something huge: The federal government had to conduct a nationwide survey "concerning the lack of availability of equal educational opportunities for individuals by reason of race, color, religion, or national origin." The results were to be reported back to Congress.

James S. Coleman, a sociologist, was tapped for the job. And he did not take it lightly. By the time Coleman filed his 700-page report , he and his team had surveyed some 650,000 students and teachers nationwide.

James S. Coleman, 1958. JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/Getty Images hide caption

"It was the most comprehensive data set, that was nationally representative, ever collected," says Kirabo Jackson, a researcher at Northwestern University. "It's actually the first time anyone had collected data that linked the characteristics of children in the home to their outcomes in school."

The day Coleman released his report, in 1966, Eric Hanushek was a graduate student in economics at MIT, eagerly hunting for a thesis project. He found it in one of Coleman's headline findings.

"Coleman explicitly said families are important and, after that, schools contribute very little," recalls Hanushek, now a senior fellow with the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. "And also that resources contribute very little."

Family matters, Coleman found; schools matter less. And how much money schools spend on their students doesn't seem to matter much at all.

"This is crazy," Hanushek remembers thinking. "If schools don't matter, why do we pay so much attention to them?"

In the decades since, Hanushek has become a chief spokesman for the How You Spend movement, arguing that pouring more money into troubled schools won't necessarily fix them. To make his case, he offers a few examples. Here's one:

Camden, N.J.

Something remarkable happened in New Jersey in the late 1990s.

As part of a long-running school funding lawsuit known as Abbott v. Burke, the state increased spending in 31 of its then-poorest districts, dubbed Abbott districts. In fact, they got so much new money that spending in some of them eclipsed spending in some of the state's wealthiest districts.

School Funding In New Jersey

Credit: Katie Park/NPR

This remarkable investment in New Jersey's poorest schools turned heads and made headlines across the country. And, if money truly matters, Hanushek says, then the Abbotts should be a success story.

But, he points out, all these years later, many are still "spending 2.5 times the national average, and there's no real evidence that they're closing the achievement gap or that they're doing significantly better."

One of those districts, Camden, is spending roughly $23,000 per student this year. And Hanushek is right about the results. While schools there have improved under Superintendent Paymon Rouhanifard, student performance is still abysmal.

A third of the district's seniors don't graduate on time, and more than 90 percent of high school students there are not proficient in either language arts or math.

Part of the problem has been mismanagement. Before Rouhanifard, Camden struggled with corruption and went through 13 superintendents in 20 years.

Much of that extra money is also paying for important things that had long been ignored.

"If you read the stories about Camden from the early '90s, late '80s, it was a really, really horrendous situation," says Rouhanifard. "Schools couldn't offer basic meals for their kids. They didn't even have cafeterias. They didn't have basic textbooks."

He says the additional funding changed that, and to focus only on low test scores overlooks the good it's done.

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing Camden's schools boils down to one word: poverty.

Nearly half of the district's students live in poverty and nearly all qualify for free- or reduced-price lunch.

In high-poverty districts, children often arrive at school needing things that more affluent districts simply don't have to provide — but providing them won't necessarily improve test scores.

And this challenge extends well beyond Camden. Nationwide, 1 in 5 children lives in poverty.

"If kids are coming to school without the basic health and nutritional supports, you need to do that," says Linda Darling-Hammond, who studies school policy at Stanford University.

Darling-Hammond says any educator will tell you: It's tough to teach a child who is chronically hungry. Or sick. Or cold, like Jameria in Philadelphia.

But, as with textbooks and teacher salaries, addressing the symptoms of poverty costs schools precious money.

For more on Camden, click here .

'Doomed' Without Preschool

To meet the needs of its disadvantaged students, North Carolina has focused much of its effort — and dollars — on one big intervention: preschool.

In the 1990s, a handful of low-income districts sued the state, arguing insufficient funding. Wake County Superior Court Judge Howard Manning found that, for most students, the state's schools and their funding were good enough.

It was a different story, though, for what Manning called "at-risk" students — among them, kids with disabilities, living in poverty or learning English as a second language. In his October 2000 decision, Manning didn't mince words:

"At-risk children, who are not presently in quality pre-kindergarten educational programs, are being denied their fundamental constitutional right to receive the equal opportunity to a sound basic education."

Superior Court Judge Howard Manning presides over a Leandro education hearing in a Wake County courtroom on July 23, 2015. Manning retired last year. Chris Seward/News Observer hide caption

Superior Court Judge Howard Manning presides over a Leandro education hearing in a Wake County courtroom on July 23, 2015. Manning retired last year.

Manning ordered the state to provide free preschool for any child considered at-risk. Not as an option, he argued, but as an obligation.

"The Court is not so naïve as to think that every single at-risk child will be an academic superstar as a result of this early childhood intervention," Manning wrote, "but the Court is convinced that without this intervention more children will be doomed to the academic basement."

A new study from the National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University is just the latest to suggest that preschool, when it's high-quality, can narrow achievement gaps before they grow too wide.

With strong support from the state's then-new governor, Mike Easley, the program grew quickly. At peak enrollment, in the 2008-09 school year, it provided free preschool to roughly 35,000 at-risk kids at a cost of $170 million.

Did it work?

Ellen Peisner-Feinberg, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has studied the state's pre-K program since it began. She's found that children who attend make greater-than-expected gains in kindergarten.

"This is particularly true with dual-language learners and children who have lower levels of English proficiency," says Peisner-Feinberg.

But it's not all good news.

She found that some of those preschool gains fade by the time these students leave third grade. For state lawmakers, that was one reason to scale back. When the Great Recession hit, they cut the program to serve 6,000 fewer students.

Judge Manning blamed the fading benefits not on the preschool program but on the lackluster schooling that many students received in later years.

"They've been screwed over by first grade, second grade, third grade," said Manning in a presentation at North Carolina State University in 2011. "The academic prop they got [from preschool] fizzled because they probably weren't challenged and were just treated like poor kids without expectations."

For more on North Carolina, click here .

Mission Creep

To some, the fact that schools are spending money to alleviate the symptoms of poverty is a kind of mission creep.

At a press conference last year, as the Indiana General Assembly was re-writing its school funding formula, state Rep. Tim Brown, a Republican, put it this way:

"You know, one of the things about education is money to help those kids who are outside the educational problem. You know, did Mary's mother get arrested the night before? Did Johnny not come with shoes to school? Those aren't to me core issues of education."

They affect education "a lot," Brown said, but help should come from outside organizations, not necessarily schools.

That may explain why lawmakers there decided to scale back the extra money they had been sending to schools that educate lots of disadvantaged kids.

School Funding In Indiana

Those dollars have made a big difference in Goshen, a small, northern Indiana town where low-wage manufacturing jobs have attracted many immigrants.

More than half of the students there are Latino, the highest concentration of any district in Indiana. And many of those students depend on the district's special English Language (EL) program, which provides extra teachers, teaching assistants, counselors and considerable parent outreach.

Hector Juarez-Montes, a fifth-grader at West Goshen Elementary, says his special English-language class is his favorite.

"It's much easier in here to speak than back in our [traditional] classroom because over there you're sort of shy if you mess up on a word," he says. "But here it's safer."

When kids like Hector feel safer speaking English in class, they perform better, too. That's one reason Superintendent Diane Woodworth says test scores went up as the number of low-income, Latino students increased in Goshen.

Last year, state lawmakers voted to fund every district more equally, whether it's in an affluent suburb or a high-poverty community.

That's meant a cut of some $3 million to Goshen, roughly a third of the cost of its EL program. But Superintendent Woodworth says she's not cutting any services — not yet, anyway.

"We're not going to go there, because we'll find money," she says. "I'm an eternal optimist."

For more on Goshen, click here .

The Magic Wand

Goshen isn't the only place where extra money has made a difference.

"A good education in a safe environment is the magic wand that brings opportunity," declared the Republican governor of Massachusetts, William Weld, back in 1993, as he signed into law a landmark overhaul of the state's school funding system. "It's up to us to make sure that wand is waved over every cradle."

That magic wand did many things, but chief among them, it gave more state money to districts that educate lots of low-income kids.

In places like Revere, north of Boston, where nearly 80 percent of students come from low-income families, many of those dollars were spent on people : to hire and keep good teachers and give them better training.

Karen English has taught in the Revere, Mass., schools for 36 years. Kirk Carapezza/WGBH hide caption

Karen English has taught in the Revere, Mass., schools for 36 years.

This is key, says Bruce Baker, who studies school funding at Rutgers. "If you have enough money to hire enough people to have reasonable class sizes and to be able to pay them sufficient wages so that you're getting good people coming into the profession, that's most of the battle of providing quality schooling."

Revere didn't stop there. It used the money to give its teachers better materials, too.

"We noticed the difference right away," says Revere's current superintendent, Dianne Kelly. In 1993, she was teaching algebra. "We adopted a whole new textbook series in the math department. The first year I was here, the textbooks I was using with my students dated — no exaggeration — back to the '50s and '60s."

Revere's schools also used the money to hire reading coaches, a technology team — some even lengthened the school day.

"I really think that the funding was like winning the World Series," says Karen English, who grew up in Revere and has taught there for 36 years.

Today, the district says nearly 90 percent of its high school graduates go on to some form of postsecondary education. That's up from 70 percent in the early '90s.

And it wasn't just Revere.

"When you look at Massachusetts' overall performance nationally, we have gone from the middle of the pack to the top of the pack," says Paul Reville, a former state education secretary who now teaches at Harvard's Graduate School of Education.

For more on Revere, click here .

Money Matters

So, quick recap: While the money in Camden, N.J., has led to relatively little academic progress, our stories from North Carolina, Indiana and Massachusetts offer a compelling counterpoint to the idea that money doesn't really matter.

So, too, do a pair of recent studies that look not at one state but at many where parents, activists and school leaders from low-income districts sued and won increases in school funding.

The first, we'll call it Study A , looked at how well these low-income students performed on the NAEP test, the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

"After the spending increased, test scores slowly, surely increased as a result," says one of the researchers, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, who is also an associate professor at Northwestern's School of Education and Social Policy.

The team behind Study A found that the achievement gap between students in high- and low-income districts shrank by roughly 20 percent. By contrast, in states that saw no school-funding reform, that gap didn't shrink at all. It grew.

Whether or not a school is funded well depends a lot on where that school is located. LA Johnson/NPR hide caption

Now to Study B .

Instead of test scores, these researchers used very different measures of success: long-term outcomes like educational attainment and a student's income in adulthood.

Why? One of the authors of this study, Northwestern's Kirabo Jackson, says that important social-emotional skills — sharing, cooperation, persistence — may not show up in a test score, but cultivating them in schools can help a child succeed in later life.

"They're designed to teach students things like, 'This is how you share. This is how you become a good person.' And these things play out," Jackson says. "If you go to a job interview and you don't understand that you need to show up on time and be polite, you're not going to get that job, no matter how smart you are."

Translation: If funding increases helped build students' social-emotional skills, then low test scores wouldn't necessarily mean the money was wasted.

Indeed, Jackson and his colleagues found a few key benefits when school spending increased steadily, by 10 percent over the 12 years that a low-income child was in school:

1.) The extra money made poor students less likely to be poor as adults.

2.) It increased the likelihood that they would graduate from high school by 10 percentage points (7 points for all students).

3.) And, perhaps most remarkable, the funding led to a nearly 10 percent increase in low-income students' adult earnings.

Jackson and his fellow researchers studied the effects on all students, but for nonpoor children, he says, funding benefits were "small" or "statistically insignificant." Only low-income students showed consistently large benefits.

The Takeaways

So, is money pixie dust?

No. If it were, there would be no debate. Or, at least, the debate wouldn't be nearly as loud.

But, does money matter — especially for low-income students? Even Stanford's Eric Hanushek agrees that it does.

"Money matters, of course," he bristles. "And I think that's a straw-man way to phrase the question."

Make no mistake, money can make a difference in the classroom. If:

Takeaway #1: The money reaches students who need it most.

"What I see as the ideal in many ways," Hanushek says, "is a system that provides extra resources to kids that need more resources. So this would be ELL kids. Special education kids. Disadvantaged kids in general."

In other words, the kind of targeted funding that helped Goshen build its special EL program in Indiana, or that paid for Revere's district-wide reset.

Takeaway #2: The increases come steadily, year after year.

For extra money to have an impact, Study B and the story of Revere in Massachusetts suggest that it can't just be a one- or two-year boost.

Takeaway #3: The money stays in the classroom: paying, training and supporting strong teachers, improving curriculum and keeping class sizes manageable.

Money alone does not guarantee success any more than a lack of it guarantees failure. Paul Reville, the former Massachusetts education secretary, says not all districts there were able to translate funding increases into academic gains. Often, the difference was how they spent the extra money.

And so we come full circle.

This debate — How You Spend versus How Much You Spend — isn't a debate at all. Or shouldn't be.

Each depends on the other.

Extra money spent thoughtlessly is no panacea for what ails many schools. But it's also true that, to pay for the kinds of things (and people) that are most likely to help vulnerable students, many schools need more money.

Lost in all of this, of course, is perhaps the most important takeaway — a question that all educators, parents and policymakers should ask themselves before they spend a dime:

Takeaway #4: How do we define success?

Is it just about test scores?

Or should our focus widen to include wages, incarceration rates and other life outcomes of kids many years after they leave the nation's schools?

Because the lesson of Camden and, again, of Study B is that not all school spending, especially on meeting students' basic needs, can be expected to improve test scores. But that doesn't mean it's being misspent or failing the children it's supposed to help.

Next week, the last week in NPR Ed's School Money series, we'll look at the political landscape of school funding and explore a few big changes on the horizon.

Right on the Money

- Posted January 22, 2010

- By Elaine McArdle

Despite repeated efforts to reward teachers based on performance -- both theirs and their students' -- many experts say this incentive doesn't improve education.

Offering financial incentives to improve education -- providing money rewards to students, teachers, schools, or districts as a way to motivate them to try harder and do better -- is one of the hottest topics in education today.

On the student side, schools in cities like New York, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., are experimenting with financial rewards, including cash payouts to students who make good grades or show other achievement. The new competitive incentive grants from the federal Department of Education -- the so-called "Race to the Top" money -- hand out financial remuneration to states that comply with certain requirements, including improving academic results.

But the greatest focus has been "pay for performance" initiatives for teachers whose students make the most academic progress, typically measured by results of standardized tests. The concept is simple: A series of influential studies in recent years have shown that teacher quality is one of the most important factors in student achievement, so "good" teachers -- as reflected in growth in student test scores -- should be paid more than their less able colleagues. Financial incentives will encourage teachers to try harder in their jobs, the theory goes, and those who don't should leave the field and seek other careers. Pay for performance will rid schools of mediocre teachers, proponents say, leading to higher student achievement, betters schools, and, in the long-run, a more productive workforce in the United States.

In the ongoing effort to address the complicated issue of improving American education, pay for performance seems to make sense, and so the movement has caught on across the country. In the past decade, at least 20 states and a large number of districts have instituted some form of pay for performance for teachers, including California, Florida, Minnesota, Texas, and the cities of Cincinnati, Denver, New York, and Charlotte, N.C., according to Donald Gratz, Ed.M.'76, author of the new book, The Peril and Promise of Performance Pay . And President Obama has announced that the federal Teacher Incentive Fund, a competitive grant program to support pay for performance plans, will increase five-fold, from $97 million to $483 million.

But does pay for performance really work? According to many experts, the answer is a resounding no -- especially when teacher ability is measured solely or primarily on student scores on standardized tests.

"There has never been any research that shows that this works, although it's very fashionable to think that it should work," says Richard Rothstein, the former education columnist at The New York Times and the author of a number of books on education, including Grading Education: Getting Accountability Right .

"When it comes to the sexy reform du jour -- basing teachers' pay on student performance -- the research doesn't support it at all," concurs Bella Rosenberg, Ed.M.'72, an independent education consultant based in Washington, D.C., who worked for more than 20 years for the American Federation of Teachers. This year, Rosenberg did a project that required her to read "just about every piece of research available on this, including from the advocates," she says. She found no evidence that pay for performance improves education. "It's not there -- it's just not there," she says.

Indeed, since the idea of pay for performance first was born, in the 18th century, it has failed every time it's been tried, says Kitty Boles, Ed.D.'91, a senior lecturer at the Ed School. As early as 1710, in England, teachers were paid based on their students' test scores in reading, writing, and arithmetic. But problems with this approach quickly became apparent, she says. The curriculum narrowed as arts and science classes were no longer taught. Teachers focused on drills aimed at improving test scores, and "teaching to the test" was born. There were even scandals with teachers faking test scores. For these reasons, pay for performance -- also known as merit pay -- was abandoned. Over the past three centuries, it has been resurrected numerous times, and in each instance, Boles says, it has failed to improve education and was eventually dropped. This cycle has been repeated each time a merit pay system has been launched, including one championed by President Richard Nixon but declared a failure not long afterwards, Boles says.

Professor Susan Moore Johnson, M.A.T.'69, Ed.D.'81, agrees. "There have been waves of merit pay initiatives in the past, and every time someone recommends it anew, it's as if it's never been done before," says Johnson, who recently coauthored Redesigning Teacher Pay: A System for the Next Generation of Educators , a book garnering much attention in the education world by advocating a radically different approach to teacher pay that encourages teacher career development through a four-tier system of promotion.

Despite the history of merit pay, these plans continue to be reborn, including in various waves in the United States over the past century. Most recently, the passage in 2001 of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act reignited the movement. By mandating that all states develop annual standardized tests to measure student performance, NCLB created objective standards that could be used for other purposes, too -- including as an ostensible means of judging teacher effectiveness. Merit pay gained real traction when the federal government instituted the fund that distributes awards to states and districts that create pay for performance plans in high-needs schools.

To Boles, the format doesn't matter, whether it's purely objective or not; merit pay misses the point. "I'm not ready to say it will never work, but I doubt it will work because it's not the way we should be assessing teachers' abilities or skills," says Boles, who instead advocates better teacher training and a career path that involves mentoring and being mentored.

Plans that rely solely on student test scores have the most opponents, including many parents, who scorn "teaching to the test," in which students are drilled to increase their test scores rather than taught to understand the underlying material and learning skills to last a lifetime. Teachers' unions are strongly against these plans for a variety of reasons, including that they say it's nearly impossible to accurately measure an individual teacher's contribution to a student's success, since a child's achievement is cumulative over a period of years and the result of the efforts of many people. Some plans only reward the teachers whose subjects are tested; namely, reading and math teachers, thereby excluding others who also influence student achievement.

"We are opposed to any form of merit pay where pay goes to individual teachers based on student test scores," says Ed Doherty, Ed.D.'98, assistant to the president of the American Federation of Teachers in Massachusetts, which has 20,000 members. Not only is this the official position of the union, Doherty says, but in a survey of the 40,000 teachers in Massachusetts, about 90 percent oppose merit pay.

A related problem is the emphasis on subjects in which student performance is easiest to measure; namely, math and reading. "There's no way to measure performance other than in math or reading, other than by observing teachers in the classroom, but that's extremely expensive, so no one is talking about that," says Rothstein. By focusing on math and reading to the exclusion of other subjects, he says, "you create incentives to further distort and narrow the curriculum, which is disastrous."

He adds, "In any institution, if you have multiple goals and you create incentives to pursue only one or two, you get people abandoning other things they should be doing in order to focus on things for which they're held accountable." In his opinion, he continues, "this is one of biggest shortcomings of No Child Left Behind -- schools have abandoned science, social studies, history, arts, and physical education, which is particularly disastrous in low-income communities."

Teachers and many others are particularly offended by the underlying assumption of merit pay: namely, that teachers would work harder if only they were rewarded with even a minor financial bonus (the pay differential in most plans is typically quite small, only a few thousand dollars tops.) Most people who go into teaching are motivated by intrinsic rewards -- the value of the work they do -- rather than extrinsic motivators, such as money, many educators believe. "There's an assumption under this that teachers would try harder if they were paid more," says Gratz. "The corollary is that they're not trying hard enough now, which means they care more about money than kids. Frankly, teachers find that insulting."

Rothstein agrees. The flawed theory behind pay for performance is "that student achievement is not as high as you'd like it to be because teachers, to use the economists' term, are shirking, are not doing as well as they could, so they need incentives to work harder or better. That assumes that reason student achievement is poor is that teachers know what to do and just aren't doing it." To the contrary, Rothstein says, poor achievement in school is a larger problem that can't be laid in the laps of teachers. "The assumption is that all our problems are due to teachers, so we don't need to pay attention to social conditions students come from," he says.

Johnson concurs. "The essential assumption of pay for performance is that pay for performance is about effort, and that teachers who are offered a small sum of money -- and it's really very small, when you look at these plans -- will somehow redouble their efforts and solve problems [of student achievement] they don't know how to solve," she says.

Rob Stein, C.A.S.'93, Ed.D.'01, also believes that teacher motivation is not the core issue. Stein was named principal of an inner-city Denver high school when it reopened two years ago after being shut down for being the worst-performing school in the district. Denver's merit pay system, known as the Professional Compensation System (ProComp), is currently touted as the model system for merit pay because it had widespread support, including from teachers and parents when it passed about five years ago.

He says, "What I see is that people have a missionary zeal to want to work with kids who need them the most. I've never heard anyone say, 'I'm applying to your school because of the extra pay incentive.'" Still, he adds, if the district is going to offer rewards for things his teachers would do anyway, he's happy to ensure they receive them.

Gratz also believes merit pay doesn't incentivize teachers. But, he says, educators in Denver find that ProComp has some real benefits in getting all stakeholders -- teachers, principals, and parents -- focused on student success. In other words, he says, the schools benefited not from improved teacher commitment but as a consequence of everyone searching for ways to help students.

Merit pay may not compel teachers to try harder. But on the specific issue of attracting high-quality teachers to teach in at-risk schools or with difficult student populations, Jennifer Steele, Ed.D.'08, says financial rewards have an impact. Steele works for the Rand Corporation on projects related to pay for performance and teacher effectiveness; at Harvard, she wrote her dissertation on whether a $20,000 cash incentive in California would induce academically talented teachers to go to disadvantaged schools.

In fact, it did. The bonus increased by 28 percentage points the likelihood that gifted teachers would enter a low-performing school. "So far, we've found that you can influence the career choices of teachers with financial incentives," Steele says. Still, that's a different issue than rewarding teachers for student performance, she says. While test scores can be one measure, it's critical that they not be the sole measure. Rather, a broad set of factors should be evaluated in assessing a teacher's performance, including his or her lesson-plan portfolio. Another measure should be a principal's subjective evaluation of a teacher, which Steele says is a pretty good predictor of a teacher's effectiveness. While there are many critics of the subjective approach, it has an important role in order to balancing out the "teach to the test" and other negative consequences of relying solely on test scores.

What to Reward Eric Anderman, Ed.M.'86, and his wife, Lynley Hicks Anderman, who teach at The Ohio State University, are researchers who've studied and published in the area of educational motivation for 20 years. In their new book, Classroom Motivation, they argue that incentives can work in motivating students -- and teachers, too -- if they are properly structured. That means incentives should be awarded only if they are informational, meaning the student has really learned something, and if the reward is not perceived as controlling but provides the student some choice, such as deciding to read a book when not specifically asked to do so.

"You get rewarded not for doing something but learning something," says Anderman. "For example, you're rewarded for demonstrating to me that you know how to add a series of two-digit numbers and understand the process behind it, versus just completing a worksheet." The same principles apply to teachers: "If teachers are simply rewarded for following some kind of protocol or rule according to how it's mandated, that's not effective. But if the teacher did something creative, innovative, that would be great because it's coming from the teacher," he says.

The other kind of reward will work, he stresses, but has serious negative consequences. "The danger is people start doing things just to get the reward and lose interest in the activity itself. So the teacher might go through the appropriate behaviors in order to get a bigger paycheck instead of because he or she wants to teach kids. The same with k ids: they'll do the worksheets in order to get the reward, but get bored with math and rule it out as a career," he says.

Of course, it's more time-consuming to base rewards on a larger portfolio of factors including subjective evaluations, which is why relying on test scores is popular. But in the end, it will backfire -- if the goal is to produce educated children. "If you keep rewarding for teaching to the test, teachers will keep doing that," says Anderman. "What would be a good thing would be if teachers were rewarded not just for making students achieve, but for specific ways of making them achieve" including learning critical thinking and other things harder to test but more valuable in the long run. Like Boles, Stein, and others, Anderman believes higher salaries across the board for teachers would be more useful than merit pay, as would better teacher preparatory programs, mentoring, and other ongoing supports.

A Multi-Tiered Approach Johnson is director of the Project on the Next Generation of Teachers, where she studies teachers' work and careers. Her latest book, Redesigning Teacher Pay: A System for the Next Generation of Educators, cowritten with John Papay, Ed.M.'05, an advanced doctoral student at the Ed School, is gaining attention from educators searching for better ways to approach teacher pay. The book grew out of two studies, the first of which took a broad look at pay for performance in four urban districts: Houston; Minneapolis; Charlotte- Mecklenberg, N.C.; and Hillsborough County, Fla. Without assessing these programs per se, Johnson explains, the book examines how these systems are set up, including whether they use student performance on standardized tests, professional evaluations, a hybrid model, and whether they used individual or group assessments.

But it's the second part of the book that is gaining attention in education circles. It offers a new and comprehensive approach for teacher pay that focuses on helping teachers develop their skills throughout their careers in order to benefit students and schools. Johnson and Papay's concept states that since money is not the primary motivating factor for teachers, it will neither attract nor retain them in the field. What's needed to cultivate good teachers -- and by extension, better students -- is a range of support including mentorship and the ability to learn and grow in a formal way, they believe.

"Teachers generally don't go into teaching for money, especially in these days when they have access to all other lines of work," in contrast to years past when women and men of color went into education because they were blocked from some fields, Johnson says. "Today, people who are choosing to teach are really choosing to teach, and it's with awareness of the limitations of salaries. No one expects to get rich. You hear this again and again in interviews with teachers." As most teachers will explain, she says, they're drawn to the field because they want to help students. "They'll say that again and again: It's the kids," she says.

For that reason, Johnson and Papay propose a system that would replace the common single-salary scale in teaching with a four-tiered pay structure that sets out goals and provides rewards in the form of substantially higher pay when teachers achieve them by being promoted to the next tier. Each of the tiers -- probationary teacher, professional teacher with tenure, master teachers and school-based leaders, and school and district leaders -- provide opportunities for career growth. And the system emphasizes career support that helps all teachers improve. Johnson and Papay also propose what they call a "Learning and Development Fund," created by diverting resources from the single-salary scale, to finance new learning opportunities for teachers, provide stipends for special staffing assignments, and give other support to assist teachers and schools.

Johnson believes that such an approach -- with its emphasis on investing in teachers' careers -- is the answer to a stable and successful teaching corps.

"Districts that implement the tiered pay-and-career structure and its companion Learning and Development Fund will fundamentally change how they recruit, compensate, assess, and develop teachers," she and Papay write. "As a result, their schools should achieve greater stability, steady improvement, and increased student success."

-- Elaine McArdle is a freelance writer based in Cambridge. Her last piece in Ed. explored rural education.

When we initially started this story, we wanted to look at incentives overall in schools -- for teachers and students. That turned out to be a huge undertaking, too huge for one short magazine story. In addition, Harvard Professor Roland Fryer's new research on student incentives wasn't being released until after the publication of our magazine. For those reasons, we decided to tackle the topic with two stories -- teacher incentives in this issue of Ed. and student incentives in a web-exclusive, "Earn to Learn? " . As always, let us know what you think!

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Public and Teachers Divided on Merit Pay, Teacher Tenure, Race to the Top

Teaching Together for Change

An economist spent decades saying money wouldn’t help schools. Now his research suggests otherwise.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news organization covering public education in communities across America. Sign up for our free weekly newsletter to keep up with how public education is changing.

This story was co-published with Vox.

Eric Hanushek, a leading education researcher, has spent his career arguing that spending more money on schools probably won’t make them better.

His latest research, though, suggests the opposite.

The paper , set to be published later this year, is a new review of dozens of studies. It finds that when schools get more money, students tend to score better on tests and stay in school longer, at least according to the majority of rigorous studies on the topic.

“They found pretty consistent positive effects of school funding,” said Adam Tyner, national research director at the Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank. “The fact that Hanushek has found so many positive effects is especially significant because he’s associated with the idea that money doesn’t matter all that much to school performance.”

The findings seem like a remarkable turnabout compared to prior research from Hanushek, who had for four decades concluded in academic work that most studies show no clear relationship between spending and school performance. His work has been cited by the U.S. Supreme Court and pushed a generation of federal policymakers and advocates looking to fix America’s schools to focus not on money but ideas like teacher evaluation and school choice.

Despite his new findings, Hanushek’s own views have not changed. “Just putting more money into schools is unlikely to give us very good results,” he said in a recent interview. The focus, he insists, should be on spending money effectively, not necessarily spending more of it. Money might help, but it’s no guarantee.

Hanushek’s view matters because he remains influential, playing a dual role as a leading scholar and advocate — he continues to testify in court cases about school funding and to shape how many lawmakers think about improving schools.

‘Does money matter?’ The decades-long debate, explained.

Hanushek began studying schools as a doctoral student in economics at MIT in 1966, when he attended an academic seminar to pore over a bombshell new study. The Coleman Report, published by the federal government, claimed that schools did not matter much for students’ academic success. More money for education wouldn’t improve things either, argued the report, which was influential but shot through with methodological flaws .

Hanushek couldn’t believe the conclusion that schools didn’t matter. By 1981, then an economics professor at the University of Rochester, he had found a way to make sense of the report’s vexing findings: Schools really did make difference, but you couldn’t tell which ones were good based on how much money they spent. Hanushek published a manifesto-like academic paper laying out this case titled: “Throwing Money at Schools.”

Eventually the debate became “Does money matter?” as the Brookings Institution put it in a book that Hanushek contributed to. He always described this framing as simplistic, but Hanushek essentially became the captain of team “not really.”

Hanushek hammered home this point with the message discipline of a politician and the data chops of an economist. He wrote updated versions of the same academic paper again in 1986 and then in 1989 , 1997 , and 2003 . He also made the case in numerous reports and articles, as well as in testimony in increasingly prevalent school funding lawsuits. In 2000, he became a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, a conservative think tank, where he remains based today.

Hanushek’s basic claim was that most studies of school “inputs” — like per-pupil spending, teacher salaries, and smaller class sizes — did not show a clear link between those resources and student outcomes. His 2003 paper showed that only 27% of the findings on spending were positively and significantly related to student performance. “One is left with the clear picture that input policies of the type typically pursued have little chance of being effective,” Hanushek wrote.

The basis for this conclusion was far more tenuous than Hanushek let on, though. Some researchers reanalyzed Hanushek’s data, and found that there actually was a link between spending and performance because his approach for summarizing studies was flawed. More importantly, the studies he relied on weren’t able to clearly isolate the impact of money.

“They were very poorly done by current standards,” said Martin West, a Harvard education professor. Nevertheless, Hanushek’s summary of these older studies, all published before 1995, is still sometimes cited today, including in legal proceedings .

Starting in the early 1990s, the economics discipline began focusing more on teasing apart cause and effect, using so-called “natural experiments,” an idea that recently won the Nobel Prize in economics. This eventually upended the school spending debate: A slew of newer papers using these methods came out showing a positive link with student outcomes. A recent overview paper by Northwestern University’s Kirabo Jackson and Claire Mackevicius combined the results of numerous prior studies. They found that on average, an additional $1,000 per student led to small increases in test scores and a 2 percentage-point boost in high school graduation rates.

The view that money matters now appears to be conventional wisdom among education researchers, although some still question whether the newer methods can convincingly show cause and effect.

Hanushek has downplayed this newer research linking spending to outcomes. Last year he even testified in a Pennsylvania school funding case that, “The majority of the studies that have been done to look at this relationship don’t give any statistically significant relationship.” This line was later cited in a trial brief by lawyers for the state.

Hanushek’s new paper: most studies do show a link between funding, performance

Hanushek’s most recent paper , posted online several months after his Pennsylvania testimony, comes to a different conclusion.

Along with Stanford predoctoral fellow Danielle Handel, Hanushek reviewed rigorous studies released since 1999. Of 18 statistical estimates of the relationship between spending and test scores, 11 were positive and statistically significant. A separate set of 18 estimates examined the link with high school completion or college attendance; 14 of those were positive and significant. (The other four leaned positive but were not significant.) These findings appear much more favorable for school spending than Hanushek’s prior work indicated.

Hanushek and Northwestern’s Jackson have publicly debated the relationship between funding and outcomes, including in a recent Maryland court case. But their most recent papers are surprisingly aligned in results, if not interpretation.

“The findings reported by these studies were remarkably similar,” said Matthew Springer, a professor at the University of North Carolina who has testified on the side of states in a number of funding cases. Both show positive effects of money, he said.

Still, Hanushek insists this is the wrong takeaway. Don’t look at the typical effect, he argues; look at the variation from study to study. “A thorough review of existing studies ... leads to conclusions similar to those in the historical work: how resources are used is key to the outcomes,” he and Handel wrote. “The range of estimates is startling.”

The context matters, they say. Sometimes money is spent well; sometimes it’s spent poorly. Sometimes the effects are big; other times they are small or nonexistent. Just focusing on the overall effect masks this variation.

To Hanushek, this aligns with what he’s been saying for decades: Throwing money at schools is a bad bet. “I still don’t think that that’s good policy — that you have 61% of very diverse studies [finding a relationship between spending and test scores] and you say I’ll bet the next billion dollars on that,” he said.

Jackson agrees that how money is spent matters. But he also thinks that Hanushek is missing the obvious conclusion from his own results.

“The vast majority of the time whatever school districts choose to spend the money on tends to improve outcomes,” he said. “I don’t see how you can look at that and then say therefore we don’t have enough evidence to suggest we should just increase the funds.”

Other researchers agreed that the variation in results is important, but that shouldn’t mean ignoring the overall impact. “The average effect still matters,” said West, the Harvard professor.

The new research has not stopped Hanushek’s advocacy work outside of academia. He is still testifying on behalf of states in court cases about whether schools should get more money, including in ongoing lawsuits in Arizona and Maryland. (Recently, he’s been paid $450 an hour for his time in these cases. Jackson was paid $300 an hour as an expert on the other side of the Maryland case.) “More often than not the academic research indicates no significant improvements in student outcomes despite increased funding,” Hanushek wrote last year in an expert report for the Maryland case.

Now, though, Hanushek’s own work contradicts his claim that most studies don’t show a positive relationship. “When I gave that testimony, I didn’t have this summary,” Hanushek said, referring to similar comments as a witness in Pennsylvania. “I wouldn’t answer it in that way” if asked again, he said. But ultimately, his thrust would be the same: “I would say that there is no consistent effect.”

The Pennsylvania judge didn’t buy Hanushek’s claims, and ruled for plaintiffs who sued the state. Other judges and politicians may be persuaded though. Some policymakers, including former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos , continue to claim that money will not improve schools. This mantra may grow louder. Schools have received $190 billion in COVID relief since 2020, and although there has been little rigorous research on the money’s effects, many commentators have already argued that the funding has been ill spent.

Meanwhile, despite the impression left by four decades of his work and legal testimony, Hanushek says he’s not actually against more funding for schools. “I have never said that money shouldn’t be spent on schools,” he said recently. He simply thinks it needs to be used more effectively. For instance, he would like to see extra resources earmarked to attract and retain good teachers in high-poverty schools, a policy he found worked in Dallas.

So should policymakers spend more dollars on public schools, attached to certain requirements? Hanushek’s answer: “Yes.”

Matt Barnum is a Spencer fellow in education journalism at Columbia University and a national reporter at Chalkbeat.

Illinois high school juniors will have to take the ACT to graduate starting spring 2025. This comes at a time when most colleges and universities are again requiring students to take entrance exams for the admissions process.

Council members questioned officials as the looming expiration of federal COVID relief money threatens to shave $808 million from the Education Department’s budget.

The district’s plan calls for training on alternative discipline practices and aims to focus on the “root cause” of student behavior.

The program will train young adults ages 18 to 24 to act “as navigators serving middle and high school students,” according to state officials.

Roughly 12% of Chicago residents age 16 to 24 are not working or in school. Black teens are most impacted.

Representing families challenging school segregation, here’s what the NAACP’s chief legal counsel told the high court.

Learn2prosper

20 Reasons Why Money Is Better Than Education

In a world that values knowledge and personal growth, the idea that money might be better than education can be quite controversial but where education is highly valued, it is important to acknowledge the significance of money beyond academics. Education is often considered a cornerstone of success, but there are arguments that suggest money holds a unique power of its own. While learning opens your mind, money acts as a tool to make life smoother. Let us delve into and explore 20 reasons why money is often considered more valuable than education.

Table of Contents

Reasons Why Money Is Better Than Education:

1. financial freedom and security:.

Having enough money to feel secure is important. It is even more important than education for a few reasons. While learning is great for growing and knowing things, having money makes sure you can deal with life’s problems and chase after opportunities. Education can help you find a good job, but money is like a safety blanket that education alone cannot give you. This blanket helps you pay for things you did not plan for, like surprise expenses or emergencies. So, even if unexpected stuff happens, having money means you will be fine and can keep living comfortably.

2. Meeting Basic Needs: