Learn more about updates regarding the 2024–2025 FAFSA process.

School of Art

- Undergraduate Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Continuing Studies

- Study Abroad

- Center K–12

- Interdisciplinary Studies

- Undergraduate Advising

Admissions & Aid

- Undergraduate

- Admissions Contacts

- Student Financial Services

Life at Pratt

- Life in Brooklyn

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Residential Life & Housing

- Health & Safety

- Student Success

- Athletics & Recreation

- Student Involvement

- Student Affairs

- Title IX & Nondiscrimination

- Current Students

- Prospective Students

- International Students

- Administrative Departments

- People Directory

Art and Design Education

- Art and Design Education, Undergraduate

- Art and Design Education, Graduate

Associate Degrees

- Game Design and Interactive Media, AOS

- Graphic Design, AOS

- Illustration, AOS

- Graphic Design/Illustration, AAS

- Painting/Drawing, AAS

Creative Arts Therapy

- Art Therapy and Creativity Development, MPS

- Art Therapy and Creativity Development, MPS, Low Residency Program

- Dance/Movement Therapy, MS

- Dance/Movement Therapy, MS, Low Residency Program

Creative Enterprise Leadership

- Arts and Cultural Management, MPS

- Design Management, MPS

Digital Arts and Animation

- Digital Arts, BFA (Emphasis in 2-D Animation)

- Digital Arts, BFA (Emphasis in 3-D Animation and Motion Arts)

- Digital Arts, BFA (Emphasis in Art & Technology/formerly Interactive Arts)

- Game Arts, BFA

- Digital Arts, MFA (3-D Animation and Motion Arts Concentration)

- Digital Arts, MFA (Interactive Arts Concentration)

- Fine Arts, BFA

- Fine Arts, MFA

Photography

- Photography Undergraduate

- Photography Graduate

- About the School of Art

- School of Art Exhibitions

- SoArt Lectures

- School of Art >

- Creative Arts Therapy >

Dance/Movement Therapy at Pratt

Creative, aesthetic, and psychotherapeutic theory come together in everything we do. Movement is done in every course and is used to learn a range of therapeutic skills. Experiential processes translate the theoretical framework into personal and practical application. You’ll focus on a variety of populations over the course of two years of clinical training.

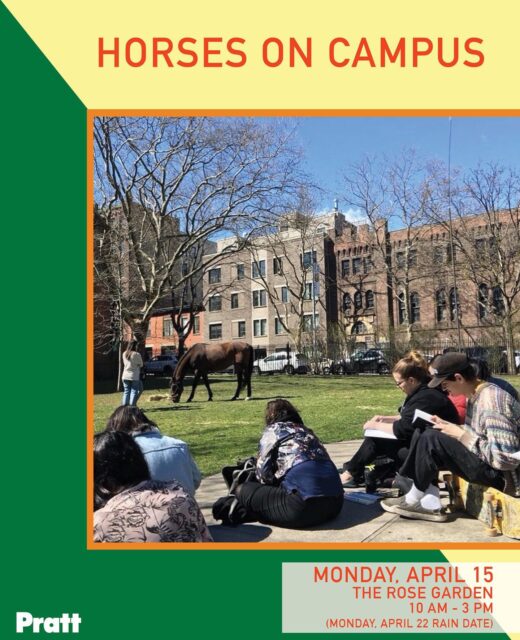

The Experience

The MS in Dance/Movement Therapy is a 60-credit program for students who want a diverse skill set, balanced with a strong theoretical framework. Interdisciplinary, socially engaged, and justice-driven, our Creative Arts Therapy community is connected by a shared mission for transformative change. Pratt’s Dance/Movement Therapy program can be completed in 4 semesters of full-time study. All courses are offered on the Pratt Brooklyn campus.

Internships

We believe creative and clinical practices are best developed together, each informing and improving the other. Internships are a vital part of the hallmark experiential learning process. Much of the coursework draws directly from clinical experiences and processing of client material. Students complete internship experiences in an array of site placements, including inpatient hospitals, community mental health agencies, and school-based settings, among others.

The mission of the Creative Arts Therapy Department at Pratt Institute is to provide the highest level of clinical training in art and dance/movement therapy, preparing graduates to work effectively with people from diverse communities. Our unique teaching philosophy is based on a combination of personal experience, didactic learning, and practical application, and is rooted in the primacy of creative process and psychodynamic theory. We offer an integration of historical perspectives and current andragogy, leading to applications of practice in a variety of settings. The program combines the power of non-verbal communication, artistic process, and embodied creative action. Our students develop self-awareness and recognition of their unique attributes through experiential learning. They acquire an increased sense of self and resiliency, which is translated to their work as creative arts therapists.

Student Learning Outcomes

- Students will be able to identify and utilize their own internal processes in service of therapeutic interventions.

- Students will comprehend and apply creative and aesthetic processes in the context of creative arts therapy theory and practice.

- Students will be able to establish a therapeutic relationship using imagery, movement, symbolization, and verbalization; and recognize shifts within that developing relationship.

- Students will be able to demonstrate knowledge of psychodynamic theory within the context of creative arts therapy practice in the service of diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing evaluation.

- Students will be able to articulate clinical theory and applied practice through writing, research, oral presentation, and professional advocacy across broad interdisciplinary communities.

- Students will be able to apply ethical and professional codes of practice as they apply to clinical practices, communities, and self.

- Students will be able to understand the intersectionality of power, privilege, and oppression as they apply to clinical practices, communities and self.

Our Faculty

Alongside their teaching roles, our faculty are accomplished artists who integrate creative and clinical practices every day in their work. See all Creative Arts Therapy faculty and administrators .

Students in Action

Reckoning with Whiteness: An Embodied Approach to Exploring Racial Identity Development for Dance/Movement Therapy Students

Success Stories

Prattfolio Story

The Art of Holding

Using Art and Dance to Promote Healing in Internships at Rikers Island and Providence House

Educating for the Future: Creative Arts Therapy Chair Julie Miller

How We Lead: Drena Fagen, MPS Art Therapy ’02, and Nadia Jenefsky, MPS Art Therapy ’99

Using Dance to Promote Healing: Dance/Movement Therapy Student Simone Saiya

Ready for more.

School of Art Pratt Institute

@soartpratt

From the Catalog

Sample courses.

- ADT-630 Clinical Diagnosis, Assessment and Treatment 3 credits

- ADT-632 Research and Thesis 3 credits

- ADT-635 Art Therapy Open Studio 3 credits

- ADT-640 Development Of Personality I 3 credits

- ADT-641 Creative Arts Therapy I 3 credits

Program Overview

The program’s structure.

Both the MPS in Art Therapy and Creativity Development and MS in Dance/Movement Therapy Master’s are 60-credit programs providing a synthesis of creative, aesthetic, and psychotherapeutic theory. Courses offer a thorough theoretical framework that is translated into personal and practical application through an experiential process. Artwork and/or movement is done in every course and is used to learn therapeutic skills. Students focus on a wide variety of populations and are required to work with a different population for each of the two years of fieldwork/internship/practicum. Both programs are for students who want a broad body of skills, balanced with a strong theoretical framework.

Academic-Year Format

The academic year format offers classes in a traditional manner, with classes in fall and spring semesters, for 15 weeks each semester. The cycle of classes is as follows: students take courses and fieldwork/practicum/internship from September through May for two consecutive years. Students in the low residency format are admitted for the spring semester only.

MINI REVIEW article

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (emdr) therapy for prolonged grief: theory, research, and practice.

- 1 School of Psychology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

- 2 School of Psychological Sciences, College of Health and Medicine, University of Tasmania, Launceston, TAS, Australia

Prolonged Grief Disorder occurs within 7-10% of the bereaved population and is a more complicated and persistent form of grief which has been associated with suicidality, mental health disorders, sleep disturbance, poor health behaviors, and work and social impairment. EMDR is a fitting treatment option for those with Prolonged Grief, focusing on processing past memories, blocks, current triggers, future fears, and preparing the person for living life beyond the loss in line with the Adaptive Information Processing Model and grief frameworks. This paper discusses the theory, research regarding the application of EMDR with prolonged grief, and gives insight and guidance to clinicians working in this area including a case example.

Introduction

Despite the universality of death and bereavement, losing a loved one is often a major distressing event in an individual’s life. Although the pain may remain in some form, often over time the loss of someone is accommodated into an individual’s life, and they can live a life of purpose and meaning beyond the loss. Research has demonstrated however that 7-10% of the bereaved population develop a more complicated and prolonged grief response ( 1 ). Although various terms have been used for this grief response, there is general consensus now among experts in the field that Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) is the correct classification for this response, now being included in both the International Classification of Diseases, 11 th Edition (ICD-11) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). Prolonged Grief includes various symptoms and challenges such as difficulty accepting the death, a sense of meaninglessness, yearning for the deceased and associated emotional pain and difficulty engaging in new activities, with a diagnosis only being warranted after a minimum 6–12-month time frame. Although there is no direct research on the duration of PGD, it is commonly understood this disorder can last years and decades without significant improvement in symptoms ( 2 ). PGD has been associated with increased rates of suicidality, mental disorder and sleep disturbance, poor health behaviors, and work and social impairment ( 3 – 8 ). Due to the functional impact, increasing rates, and challenges associated with having a prolonged grief response, identifying individuals at risk, and those who need evidenced based treatments is of great importance. This notion is further supported by the findings by Lichtenthal et al. ( 9 ) demonstrating those with prolonged grief are less likely to receive support, despite being the ones in greatest need for intervention. Furthermore, Johnson et al. ( 10 ) demonstrated that more than 90% of individuals experiencing prolonged grief symptoms are relieved to understand their grief is a more complicated form, and report interest in receiving intervention for their prolonged grief symptoms. Having effective and widely available treatments for those with prolonged grief is further supported by Eisma, Boelen, and Lenferink ( 11 ) which have suggested an increase in the rates of prolonged grief since the COVID-19 pandemic due to a lack of social support, limited access to professional grief support, and the individual not being able to engage in traditional grief rituals to assist them in accommodating and adjusting to the loss (saying goodbye, viewing the body, and burial).

Up to this point, the research surrounding interventions for PGD has largely been centered around cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions. This preference for CBT focused approaches in addressing PGD might stem from previous clinical recommendations, which classified prolonged grief as a type of major depressive disorder ( 12 ). While numerous studies have reported significant outcomes from such interventions, a notable percentage of subjects do not experience meaningful therapeutic benefits ( 13 ). For instance, Bryant et al. ( 2 ) found that post-treatment, 37.9% of participants undergoing CBT continued to meet the criteria for PGD. In more recent years, other more specific interventions have been developed for the treatment of Prolonged Grief Disorder, notably Complicated Grief Treatment (CGT; 14 ). Complicated Grief Treatment is typically provided in a structured weekly format, generally consisting of 16 sessions ( 15 ). CGT is divided into 4 major phases: (1) getting started which involves areas such as getting a grief history, providing psychoeducation, building up social support and various grief related behavioral tasks, (2) core revisiting sequence which involves imaginal exposure based exercises to connect with the grief, (3) midcourse review which involves an evaluation of treatment progress and (4) closing sequence which includes preparation for closure and completing any other necessary supports and interventions ( 16 ). Although CGT has been demonstrated to be more effective than are proven efficacious treatments for depression, including citalopram ( 15 ) and interpersonal therapy ( 14 , 17 ), there is still an absence of large, repeated randomized controlled trials demonstrating consistent results. Furthermore, in some research response rates in CGT were only 51% ( 14 ), and of practical relevance to clinicians, many individuals that may be working with Prolonged Grief are firstly not aware of CGT being an intervention, and secondly would have to become additionally trained and supervised in this approach. It is also important to note that similar with many other clinical presentations such as anxiety and depression, having various different treatment approaches available is of benefit as some clients may respond better to certain treatments provided. Furthermore, often certain components of treatments may be combined and integrated based on a client’s needs and goals. As an example, therapists could integrate elements of the getting started phase of CGT to have a grief focused, expert designed structure to assist with their assessment and preparation work, and then choose to implement EMDR therapy to process distressing elements of the loss, rather than the imaginal exposure-based exercises included in phase 2 of CGT.

Prolonged Grief Disorder has been listed in both the DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 under the trauma and stressor related disorder categories, and many experts within the field including Shear et al. ( 18 ), view PGD as a trauma and stress response. Based on this, treatment approaches should view prolonged grief through a “trauma lens”, allowing the adaptive resolution of information which is impeding on the natural grieving process. This is further supported by the illustration that several elements of PGD show considerable overlap with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms including intrusive images of the deceased, engaging in avoidance behavior, feeling estranged from others, sleep disturbance, and difficulty concentrating. Differences however do exist such as PTSD more being associated with fear, whereas prolonged grief associated with yearning and sadness. Furthermore, the content of intrusive images in PTSD being related to the traumatic event, whereas in prolonged grief this can be related to the person or factors associated with the loss ( 19 ). It is clear however that based on EMDR being a first line and consistently effective treatment for PTSD ( 20 )., PGD being viewed as a trauma and stress response, and the overlap of PTSD and PGD, that the use of EMDR in this population is warranted. This is also supported by theoretical accounts and building empirical research as discussed below.

Theory and frameworks: integrating our understanding of grief and the adaptive information processing model

In understanding a clients prolonged grief response, the Adaptive Information Processing Model ( 21 ) can act as our underlying framework in understanding as to why a clients natural grieving process has become blocked, complicated, or prolonged in some way. The Adaptive Information Processing Model suggests that mental health challenges and pathology is related to blocked information processing at the time of a traumatic, distressing, or challenging experience, and the subsequent way this information is stored maladaptively within our brain and nervous system. Due to the nature of an event, past history and experiences, and environmental and contextual factors at the time of an experienced event, this may impact on our ability to make sense and process an event or series of events that have occurred. If so, this information frozen and stored in a raw and state specific form can continue to impact on the way we see ourselves, the world, and our interactions with others, and through our engagement with life can be activated on a conscious or unconscious level leading to activation of images, feelings, thoughts, emotions, and subsequently certain behaviors.

In applying the AIP Model in the case of prolonged grief, integrating this theoretical framework with well-known and supported grief frameworks can add greater context to a client’s grief experience, and importantly give insight as to how EMDR therapy should be utilized. One of the most common, and well supported grief frameworks is known as the Dual Process Model by Stroebe and Schut ( 22 ). This model suggests that to be able to adjust and accommodate the loss into our lives, there needs to be a balance and oscillation between loss-oriented tasks and restoration-oriented tasks. In relation to this model, loss-oriented tasks involve aspects of the grief experience such as doing the active grief work, thinking about, and connecting with the loved person, engaging with reflection around what life was like before the loss, and connecting with memories and experiences regarding the person and life you had with them. The ultimate aim and goal of dealing with this area is to emotionally process the loss, involving a whole range of feelings, which does not occur in stages, but happens flexibly at certain time points ( 23 ). Loss oriented aspects of the grief are often more predominant during the initial phases of a loss, and this model considers factors associated with this such as closeness of the relationship, attachment, and other factors that may impede on engagement within this domain such as avoidance. Restoration oriented activities and engagement are focused on what life is like now, and what it will look like beyond the loss, involving components such as figuring out your new life role and identity now that this person is not here, creating new behaviors and experiences, forging new relationships, and recreating a life with meaning and fulfilment, whilst still keeping a connection with the deceased in some way if desired. This important area also includes dealing with secondary loss, such as the loss of an emotional support person due to the bereavement, feelings of isolation, and additional life changes contributing to distress such as increased household responsibilities, or life roles ( 24 ).

If we integrate these models as a unified framework for understanding prolonged grief, we can utilize our knowledge of risk factors in EMDR therapy to gain greater understanding of the possible blocks, information, and contributing factors that may impact or impede on someone’s natural healing process. Regarding loss-oriented tasks, there are several factors that have been consistently demonstrated in the research regarding prolonged grief that may impact on engagement in this domain. These include nature of the relationship with the deceased, childhood trauma, prior experiences of loss and pre-death mental health, attachment style, and schemas, ( 25 – 27 ). As an example, if an individual has prior unprocessed childhood trauma, their capacity to engage in sitting with feelings and processing the loss may be impacted due to challenges with managing distress, therefore there may be a need within our treatment to process this in addition to the grief related memories. Similarly, those with an insecure or avoidant attachment may want to avoid anything to do with loss-oriented tasks, and those with a self-sacrifice schema may put others needs for grieving over their own. Similarly, regarding restoration-oriented activities, various factors identified in the research may impact or impede on someone’s ability to adjust and accommodate the loss. These include areas such as low levels of social support, poorer family functioning, and low levels of optimism ( 28 ), considerations we need to take into account throughout our EMDR assessment, preparation and processing phases. As demonstrated, from combining the AIP model, Dual Process Model and identified risk factors associated with prolonged grief, our case conceptualization and knowledge of targets for processing in EMDR can be strengthened.

EMDR and grief: what the research says

The use of EMDR with bereaved individuals is not uncommon, with Luber ( 29 ) outlining a suggested protocol for grief which involved discussing important considerations for clinicians regarding target assessment, and various goals and components of consideration when using EMDR for grief including connecting with a balanced range of emotions, and to accommodate the loss into an individual’s life. Solomon and Rando ( 30 , 31 ) provided important insights for clinicians through multiple papers highlighting the importance of implementing EMDR within existing grief frameworks, considering all three prongs of EMDR reprocessing (past, present, and future), the need to focus on early life experiences and attachment as necessary, and the illustration of these principles through various case examples. In addition, Solomon and Hensley ( 32 ) discuss the use of EMDR for grief in the context of COVID-19 and more recently Solomon and Meysner ( 33 ) cover the use of EMDR with traumatic grief in the Oxford Handbook of EMDR, providing suggestions and guidance for clinicians working with traumatic bereavement. Regarding clinical research, Hornsveld et al. ( 34 ) investigated the efficacy of eye movements in reducing the emotionality of memories relating to loss. Sixty participants were asked to recall a negative loss-related memory before and after one of three conditions—eye movement, relaxation music, or a control with recall-only. In comparison to the relaxation music and control group, the eye movement group showed significantly greater reductions in both the ability to focus on the loss related memory and emotionality of the memory. In research by Sprang ( 35 ), 50 participants self-selected either EMDR or guided morning (exposure-based grief intervention) for individuals experiencing traumatic grief. Both treatments resulted in significant reductions in outcome measures such as reexperiencing, nightmares, rumination, and intrusive symptoms. This is consistent with Ironson et al. ( 36 ) findings in a PTSD population, however, EMDR participants experienced near complete symptom reduction at a much faster rate (8 sessions) in comparison to the GM condition in 13 sessions, an important finding for time-limited clinical settings. Furthermore, those who engaged in EMDR reported significant increases in positive memories of their loved ones, a finding not demonstrated in the GM condition, demonstrating additional benefits to EMDR as a grief intervention.

In another study by Meysner, Cotter, & Lee ( 37 ) the effectiveness of EMDR was compared with an integrated cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention for grief. Nineteen participants (12 females and 7 males) who identified themselves as struggling with grief were randomly allocated to treatment conditions for a 7-week treatment intervention. The results demonstrated CBT and EMDR to be equally effective in reducing grief symptoms, trauma symptoms, and distress. In a study using the same participants by Cotter, Meysner, and Lee ( 38 ), qualitative feedback on the benefits of each treatment were provided by participants. Participant reports common to both therapies included increased behavioral engagement, a better and heathier relationship to their deceased loved one, an increase in positive emotions, and an improvement in confidence. Regarding reported differences between each condition, the CBT group described benefits such as learning various emotional regulation skills and feeling like they were now in a new chapter of their life. In the EMDR condition, it was reported a noticeable benefit was that previously disturbing memories were now more distant and clearer.

In 2018 van Denderen et al., ( 39 ) completed a randomized control trial on the use of an integrated EMDR and CBT intervention for homicidally bereaved Dutch adults. The research included 85 participants, and demonstrated an integrated CBT and EMDR intervention was effective in reducing both complicated grief symptoms and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms. In a further similar study completed by Lennefrink et al. ( 40 ) a combined Cognitive Therapy and EMDR intervention was used with individuals bereaved by a loss from the MH17 plane crash. In their multicenter randomized control trial, self-rated scores for persistent complex bereavement, depression, and PTSD were comparted between an immediate treatment and waitlist control in 39 Dutch adults. The immediate treatment group showed a significant decline in depression, however no significant between group differences were observed regarding PTSD and grief symptoms.

More recently, ( 41 ) presented a case series on the efficacy of short term EMDR with patients with persistent complex bereavement. Three patients who had all lost a first degree relative were included in the case series, with between 1-2 sessions of EMDR being used to process complicated grief targets. In all cases positive improvements were noted on both quantitative clinical instruments, and feedback including changes such as not feeling guilty about the loss, being able to engage in life more, decreased avoidance, and returning to normal routines. In 2020 Solomon and Hensley discussed the application of EMDR in relation to grief and mourning in times of COVID-19. Similar to previous discussed findings, the case presented in this paper demonstrated positive improvement in symptoms and being able to move forward from the loss.

EMDR for grief treatment considerations

EMDR therapy is a transdiagnostic and integrative psychotherapy ( 42 ) and as highlighted has been applied effectively with individuals experiencing various forms of grief. Regarding the application of EMDR with Prolonged Grief, the standard protocol is applied with consideration of all three prongs, and other targets as highlighted that may impact on the individuals natural grieving process. Furthermore, there are important considerations and areas of focus to be aware of as a clinician. Firstly, as previously discussed, in the assessment phase of EMDR when a client has experienced grief, it is of vital importance to understand and assess for the risk factors mentioned to understand a client’s current likelihood of developing a more complicated and prolonged grief response and areas to process within treatment. Regarding our education, not only is it important to frame the clients’ current challenges in line with the AIP mode, incorporating grief frameworks such as the Dual Process Model is essential. In preparation for processing, standard EMDR resource development ( 43 ) and self-regulation techniques ( 44 ) as necessary can be employed. In addition, considering restoration-oriented activities as mentioned and the risk factors that may impact on this area, building up social support, and creating hope and optimism through resource development may be necessary components to enhance clinical efficacy. Previous clinical research has also demonstrated that a positive therapeutic alliance early on in therapy results in a greater reduction of prolonged grief symptoms ( 45 ). Considering this as a core tenet of our approach aligns with recent peer reviewed articles by Piedfort-Marin ( 46 ) and Hase and Brisch ( 47 ) which highlight the core role of the therapeutic relationship in EMDR.

Regarding target assessment, and subsequently desensitization and reprocessing, prior memories that are resulting in the client not being able to grieve or accommodate the loss are often a key focus point of treatment. These targets can often be centered around the themes of responsibility (e.g., I should have done more) or an individual’s ability to cope (I can’t manage this), although each individual may be unique regarding how they process loss related information and previous events underlying their symptoms. As previously discussed, in line with the AIP model, there may be a need to process other past traumatic events, other losses, or other sources of maladaptively stored information impacting or impeding on an individual’s natural grieving process. Furthermore, in working with grief, significant importance is placed on current triggers and the use of the Flash Forward Approach ( 48 ) to process catastrophic or significantly disturbing fears towards the future. Some examples of current triggers may be someone talking about the loved one, being reminded of them from a song or place, or other loss associated material. Processing fears the client may have towards the future (e.g., being alone forever, never enjoying a moment again in life) with the flashforward technique often provides further beneficial effects for clients, allowing them to feel more comfortable about life in the future. Future templates also assist in this way, providing further adaptive information for the person to feel they can cope, keep a connection with their loved one, and still have a sense of meaning in their life. As highlighted, the AIP model and the application of EMDR across all 8 phases can be a fitting and appropriate treatment framework and approach for working with clients whose grief has become complicated and blocked in some form.

Case example

Mary is a 24-year-old who lost her mother in a workplace accident. Since the death Mary has lost interest and engagement with hobbies, connecting with friends, avoids any reminders of the loss including places and people, and feels like life has lost all meaning and purpose. Mary has not engaged in therapy or talked about the grief with anyone for over 3 years. On assessment at the start of therapy, Mary met the PGD criteria based on the Prolonged Grief-13 (PG-13), a diagnostic tool to assess against the criteria for diagnosis. In EMDR therapy utilizing the standard protocol approach, a detailed history was taken with curiosity and assessment of known risk factors for PGD as highlighted earlier, and an assessment of other traumatic experiences which may be impacting on Mary’s current grief experience. Concurrently with gaining information about Mary’s history, and current challenges regarding the grief, Mary focused on building self-regulation skills through EMDR based techniques such as Resource Development and Installation ( 43 ). In addition, boosting up social connection and engagement was a major early focus, and from the preparation phase of EMDR, overall a willingness to start to process components of the grief and past trauma became more evident. This was in addition to Mary starting to have a greater positive connection to her deceased mother, being able to share positive stories and describe things that she loved about her in therapy. EMDR target assessment phase revealed certain EMDR targets for processing including the moment she found out about the death, a previous argument a few days before the death with her mother, previous losses and trauma from childhood, current triggers such as driving past her Mums house or work, and also fears of the future around what life would look like, in addition to positive future template work around being able to cope and manage events such as Christmas, anniversaries, and her Mother’s birthday. Mary responded well to treatment after 12 sessions of EMDR, no longer satisfying the criteria for a diagnosis of PGD. Mary showed improvement around being able to talk about the death or being in certain places related to the loss, has increased her connection with her mother in a way that feels meaningful to her, has been able to connect socially and with hobbies again, and has regained a sense of purpose in her life.

Overall, EMDR is a powerful treatment approach for those whose natural grieving process has become blocked in some way. The AIP model in combination with the Dual Process Model provides a useful framework to understand what has caused these blocks, and how we can support clients in moving forward in life after loss. Although the research in this area is building, there needs to be further research completed, especially considering individuals who have experienced trauma are more at risk of developing a prolonged and complicated grief response. The research so far has been limited in terms of not examining the use of EMDR specifically for those who meet the diagnostic criteria for Prolonged Grief Disorder. Most studies have also mentioned limitations regarding sample size and follow up. Furthermore, no trials completed so far have compared EMDR with Complicated Grief Treatment by Katherine Shear ( 49 ), which currently has the most empirical support for this population group. Further studies examining the comparison of EMDR and CGT independently and also combined would be of benefit to determine whether there is any additional benefit of combining both, in comparison to just using one intervention.

Author contributions

LS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Lundorff M, Holmgren H, Zachariae R, Farver-Vestergaard I, O’Connor M. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord . (2017) 212:138–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.030

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Bryant RA, Kenny L, Joscelyne A, Rawson N, Maccallum F, Cahill C, et al. Treating prolonged grief disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry . (2014) 71:1332–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1600

3. Szanto K, Prigerson H, Houck P, Ehrenpreis L, Reynolds CF III. Suicidal ideation in elderly bereaved: the role of complicated grief. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav . (1997) 27:194–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1997.tb00291.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Germain A, Caroff K, Buysse DJ, Shear MK. Sleep quality in complicated grief. J Traumatic Stress: Off Publ Int Soc Traumatic Stress Stud . (2005) 18:343–6. doi: 10.1002/jts.20035

5. Hardison HG, Neimeyer RA, Lichstein KL. Insomnia and complicated grief symptoms in bereaved college students. Behav Sleep Med . (2005) 3:99–111. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0302_4

6. Mitchell AM, Kim Y, Prigerson HG, Mortimer MK. Complicated grief and suicidal ideation in adult survivors of suicide. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav . (2005) 35:498–506. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.5.498

7. Simon NM, Pollack MH, Fischmann D, Perlman CA, Muriel AC, Moore CW, et al. Complicated grief and its correlates in patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry . (2005) 66:1105–10.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

8. Silverman GK, Jacobs SC, Kasl SV, Shear MK, Maciejewski PK, Noaghiul FS, et al. Quality of life impairments associated with diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief. psychol Med (2000) 30(4):857–62.

9. Lichtenthal WG, Nilsson M, Kissane DW, Breitbart W, Kacel E, Jones EC, et al. Underutilization of mental health services among bereaved caregivers with prolonged grief disorder. Psychiatr Serv . (2011) 62:1225–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.10.pss6210_1225

10. Johnson JG, First MB, Block S, Vanderwerker LC, Zivin K, Zhang B, et al. Stigmatization and receptivity to mental health services among recently bereaved adults. Death Stud . (2009) 33:691–711. doi: 10.1080/07481180903070392

11. Eisma MC, Boelen PA, Lenferink LI. Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Res . (2020) 288:113031. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113031

12. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-IV-TR . 4th, Text Revision ed. Washington: DC: American Psychiatric Association (2000).

Google Scholar

13. Breen LJ, Hall CW, Bryant RA. A clinician’s quick guide of evidence-based approaches: Prolonged grief disorder. Clin Psychol . (2017) 21:153–4. doi: 10.1111/cp.12124

14. Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF 3rd. Treatment of complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc . (2005) 293:2601–8.

15. Shear MK, Reynolds CF, Simon NM, Zisook S, Wang Y, Mauro C. Optimizing treatment of complicated grief: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry . (2016) 73:685–94.

16. Shear MK, Gribbin Bloom C. Complicated grief treatment: An evidence-based approach to grief therapy. J Rational-Emotive Cognitive-Behavior Ther . (2017) 35:6–25.

17. Shear MK, Wang Y, Skritskaya N, Duan N, Mauro C, Ghesquiere A. Treatment of complicated grief in elderly persons: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry . (2014) 71:1287–95.

18. Shear K, Monk T, Houck P, Melhem N, Frank E, Reynolds C, et al. An attachment-based model of complicated grief including the role of avoidance. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2007) 257:453–61.

19. Szuhany KL, Malgaroli M, Miron CD, Simon NM. Prolonged grief disorder: Course, diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Focus . (2021) 19:161–72.

20. de Jongh A, de Roos C, El-Leithy S. State of the science: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. J Traumatic Stress (2024).

21. Shapiro F. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Basic principles, protocols, and procedures . New York City, US: Guilford Press (2001).

22. Stroebe MS, Schut H. Meaning making in the dual process model of coping with bereavement. In Neimeyer RA (Ed.), Meaning reconstruction & the experience of loss (pp. 55–73). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/10397-003

23. Schut MSH. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Stud . (1999) 23:197–224.

24. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: A decade on. OMEGA-journal Death Dying (2010) 61(4):273–89.

25. He L, Tang S, Yu W, Xu W, Xie Q, Wang J. The prevalence, comorbidity and risks of prolonged grief disorder among bereaved Chinese adults. Psychiatry Res (2014) 219(2):347–52.

26. Schaal S, Jacob N, Dusingizemungu JP, Elbert T. Rates and risks for prolonged grief disorder in a sample of orphaned and widowed genocide survivors. BMC Psychiatry . (2010) 10:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-55

27. Thimm JC, Holland JM. Early maladaptive schemas, meaning making, and complicated grief symptoms after bereavement. Int J Stress Manage . (2017) 24:347.

28. Thomas K, Hudson P, Trauer T, Remedios C, Clarke D. Risk factors for developing prolonged grief during bereavement in family carers of cancer patients in palliative care: a longitudinal study. J Pain Symptom Manage . (2014) 47:531–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.022

29. Luber M. Protocol for excessive grief. J EMDR Pract Res . (2012) 6:129–35.

30. Solomon RM, Rando TA. Utilization of EMDR in the treatment of grief and mourning. J EMDR Pract Res . (2007) 1:109–17.

31. Solomon RM, Rando TA. Treatment of grief and mourning through EMDR: Conceptual considerations and clinical guidelines. Eur Rev Appl Psychol . (2012) 62:231–9.

32. Solomon RM, Hensley BJ. EMDR therapy treatment of grief and mourning in times of COVID-19. J EMDR Pract Res . (2020) 14(3):162–74. doi: 10.1891/EMDR-D-20-00031

33. Solomon R, Meysner L. EMDR Therapy and Traumatic Grief (Clinical Guidelines) . (2023) In Farrell D., Schubert S, Kiernan M. The Oxford Handbook of EMDR. Oxford University Press.

34. Hornsveld HK, Landwehr F, Stein W, Stomp MP, Smeets MA, van den Hout MA. Emotionality of loss-related memories is reduced after recall plus eye movements but not after recall plus music or recall only. J EMDR Pract Res . (2010) 4:106.

35. Sprang G. The use of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in the treatment of traumatic stress and complicated mourning: Psychological and behavioral outcomes. Res Soc Work Pract . (2001) 11:300–20.

36. Ironson G, Freund B, Strauss JL, Williams J. Comparison of two treatments for traumatic stress: A community-based study of EMDR and prolonged exposure. J Clin Psychol . (2002) 58:113–28.

37. Meysner L, Cotter P, Lee CW. Evaluating the efficacy of EMDR with grieving individuals: A randomized control trial. J EMDR Pract Res . (2016) 10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.10.1.2

38. Cotter P, Lee CW. Evaluating the efficacy of EMDR with grieving individuals: A randomised control trial. J EMDR Pract Res . (2016) 10:3.

39. van Denderen M, de Keijser J, Stewart R, Boelen PA. Treating complicated grief and posttraumatic stress in homicidally bereaved individuals: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Psychol Psychother . (2018) 25:497–508.

40. Lenferink LI, de Keijser J, Smid GE, Boelen PA. Cognitive therapy and EMDR for reducing psychopathology in bereaved people after the MH17 plane crash: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. Traumatology . (2020) 26:427.

41. Usta FD, Yasar AB, Abamor AE, Caliskan M. A case series: Efficacy of short term EMDR on patients with persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD). Eur Psychiatry . (2020) 41:S360–1.

42. Dominguez SK. Farrell D, Schubert S, Kiernan, editors. The Oxford Handbook of EMDR. Oxford University Press (2023).

43. Leeds AM, Shapiro F. EMDR and resource installation: Principles and procedures for enhancing current functioning and resolving traumatic experiences. Brief Ther strategies individuals couples . (2000), 469–534.

44. van Genugten L, Dusseldorp E, Massey EK, van Empelen P. Effective self-regulation change techniques to promote mental wellbeing among adolescents: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev . (2017) 11:53–71.

45. Glickman K, Katherine Shear M, Wall MM. Therapeutic alliance and outcome in complicated grief treatment. Int J Cogn Ther . (2018) 11:222–33.

46. Piedfort-Marin O. Transference and countertransference in EMDR therapy. J EMDR Pract Res . (2018) 12:158–72.

47. Hase M, Brisch KH. The therapeutic relationship in EMDR therapy. Front Psychol . (2022) 13:835470.

48. Logie R, De Jongh A. The “Flashforward procedure”: Confronting the catastrophe. J EMDR Pract Res . (2014) 8:25–32.

49. Katherine SM, Mulhare E. Complicated grief. Psychiatr Ann (2008) 38 10.

Keywords: grief, EMDR, prolonged grief, trauma, therapy, mental health

Citation: Spicer L (2024) Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy for prolonged grief: theory, research, and practice. Front. Psychiatry 15:1357390. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1357390

Received: 18 December 2023; Accepted: 26 March 2024; Published: 15 April 2024.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Spicer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liam Spicer, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Marian Chace Foundation Lecture: Rhythms of Research and Dance/Movement Therapy

- Published: 16 February 2018

- Volume 40 , pages 142–154, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Robyn Flaum Cruz 1

882 Accesses

3 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Acharya, S., & Shukla, S. (2012). Mirror neurons: Enigma of the metaphysical modular brain. Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine, 3 (2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-9668.101878 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

American Dance Therapy Association (Producer). (2013). ADTA Talks: Dance/Movement Therapy: Psychodiagnosis, Movement, and Neurology, Robyn Flaum Cruz. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mu67F5OjwME

Bearrs, K. A., McDonald, K. C., Bar, R. J., & DeSouza, J. F. X. (2017). Improvements in balance and gait speed after a 12 week dance intervention for Parkinson’s disease. Advances in Integrative Medicine, 4, 10–13.

Article Google Scholar

Berrol, C. (2016). Reflections on dance/movement therapy and interpersonal neurobiology: The first 50 years. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 38 (2), 303–310.

Bothwell, L. E., & Podolsky, S. H. (2016). The emergence of the randomized controlled trial. New England Journal of Medicine, 375 (6), 501–504.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chaiklin, H. (1975). Marian Chace: Her papers . Columbia, MD: American Dance Therapy Association.

Google Scholar

Chaiklin, H., & Chaiklin, S. (2012). The case study. In R. F. Cruz & C. F. Berrol (Eds.), Dance/movement therapists in action: A working guide to research options (2nd ed., pp. 75–101). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Cruz, R. F. (1995). An empirical investigation of the Movement Psychodiagnostic Inventory. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering Vol. 57 (2-B), August, 1996, 1495.

Cruz, R. F. (2016). Dance/movement therapy and developments in empirical research: The first 50 years. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 38 (2), 297–302.

Davis, M. (1991). Guide to movement analysis methods part 2: Movement psychodiagnostic inventory.

Depez, E. E., & Chen, C. (2017). Medical journals have a fake news problem. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-08-29/medical-journals-have-a-fake-news-problem

Devereaux, C. (2017). Educator perceptions of the inclusion of dance/movement therapy within the special education classroom. Body, Movement, and Dance in Psychotherapy, 12 (1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2016.1238011 .

Dominus, S. (2017). When the revolution came for Amy Cuddy. New York Times Magazine , pp. 28–33, 50–55.

Hanna, J. L. (2014). Dancing to learn: The brain’s cognition, emotion, and movement . London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Hulbert, S., Ashburn, A., Roberts, L., & Verheyden, G. (2017). Dance for Parkinson’s—the effects on whole body co-ordination during turning around. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 32, 91–97.

Kattensroth, J. C., Kalisch, T., Holt, S., Tegenthoff, M., & Dinse, H. R. (2013). Six months of dance intervention enhances postural, sensorimotor, and cognitive performance in elderly without affecting cario-respiratory functions. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience . https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2013.00005 .

Kawano, T. (2017). Developing a dance/movement therapy approach to qualitatively analyzing interview data. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 56, 61–73.

Ko, K. S. (2016). East Asian students’ experiences of learning dance/movement therapy in the US: A phenomenological investigation. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 38 (2), 358–377.

Mau, L. W., & Giordano-Adams, A. (2016). Social media and dance/movement therapy: The first 50 years. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 38 (2), 378–406.

McNeely, M. E., Duncan, R. P., & Earhart, G. M. (2015). Impacts of dance on non-motor symptoms, participation, and quality of life in Parkinson disease and healthy older adults. Maturitas, 82, 336–341.

Mollett, A., Brumley, C., Gilson, C., & Williams, S. (2017). Communicating your research with social media . London: Sage.

National Institutes of Health. (2016). A short history of the National Institutes of Health by Victoria A. Harden. Retrieved from https://history.nih.gov/exhibits/history/index.html

Olvera, A. E. (2008). Cultural dance and health: A review of the literature. American Journal of Health Education, 39 (6), 353–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2008.10599062 .

Stahl, J. (2017). We are born to love dance—science says so! Dance Magazine . Retrieved from http://www.dancemagazine.com/why-humans-love-dance-2487518208.html

Sur, R. L., & Dahm, P. (2011). History of evidence-based medicine. Indian Journal of Urology, 27 (4), 487–489. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.91438 .

Tantia, J. F. (2014). Body-focused interviewing: Corporeal experience in phenomenological inquiry, In SAGE Research Methods Cases. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/978144627305013519226

Thaut, M. H., & Abiru, M. (2010). Rhythmic auditory stimulation in rehabilitation of movement disorders: A review of current research. Music Perception, 27 (4), 263–269.

Timothy, E. K., Graham, F. P., & Levack, W. M. M. (2016). Transitions in the embodied experience after stroke: Grounded theory study. Physical Therapy, 96 (10), 1565–1575.

Wingfield, B. (2017). The peer review system has flaws but it’s still a barrier to bad science. The Conversation . Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/the-peer-review-system-has-flaws-but-its-still-a-barrier-to-bad-science-84223

Young, J. (2017). The therapeutic movement relationship in dance/movement therapy: A phenomenological study. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 39 (1), 93–112.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

1718 Anderson Pl SE, Albuquerque, NM, 87108, USA

Robyn Flaum Cruz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robyn Flaum Cruz .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Research Involved in Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the author.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cruz, R.F. Marian Chace Foundation Lecture: Rhythms of Research and Dance/Movement Therapy. Am J Dance Ther 40 , 142–154 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-018-9267-7

Download citation

Published : 16 February 2018

Issue Date : June 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-018-9267-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Dance Movement Therapy (DMT)

- Bronx Psychiatric

- Entraining Motion

- Creative Arts Therapies

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Movement-Based Therapies in Rehabilitation

Melissa e. phuphanich.

a Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, VA Greater Los Angeles Health Care System, 11301 Wilshire Boulevard (117) Los Angeles, CA 90073, USA

Jonathan Droessler

Lisa altman.

b Healthcare Transformation, VA Greater Los Angeles Health Care System, 11301 Wilshire Boulevard (117) Los Angeles, CA 90073, USA

c University of California Los Angeles- UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Blessen C. Eapen

Movement therapy refers to a broad range of Eastern and Western mindful movement-based practices used to treat the mind, body, and spirit concurrently. Forms of movement practice are universal across human culture and exist in ancient history. Research demonstrates forms of movement therapy, such as dance, existed in the common ancestor shared by humans and chimpanzees, approximately 6 million years ago. Movement-based therapies innately promote health and wellness by encouraging proactive participation in one’s own health, creating community support and accountability, and so building a foundation for successful, permanent, positive change.

- • Decrease fear avoidance and empower individuals to take a proactive role in their own health and wellness.

- • Can benefit patients of any ability; practices are customizable to the individual’s needs and health.

- • Are safe, cost-effective, and potent adjunct treatments used to supplement (not replace) standard care.

- • Deliver patient-centered, integrative care that accounts for the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of health and illness.

- • Have diverse, evidence-based benefits, including reduction in pain, stress, and debility, and improvements in range of motion, strength, balance, coordination, cardiovascular health, physical fitness, mood, and cognition.

Introduction

Movement therapy refers to a broad range of Eastern and Western mindful movement–based practices used to treat the mind, body, and spirit concurrently. Forms of movement practice are universal across human culture and exist in ancient history. Research demonstrates forms of movement therapy, such as dance, existed in the common ancestor shared by humans and chimpanzees, approximately 6 million years ago. 1 Movement-based therapies innately promote health and wellness by encouraging proactive participation in one’s own health, creating community support and accountability, and so building a foundation for successful, permanent, positive change.

Movement therapies used in conjunction with conventional medicine allow physicians to offer comprehensive, patient-centered treatment plans. This holistic approach embodies the essence of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation by maximizing patient function and improving quality of life (QOL) to treat the whole person, not just the disease. The combination of modern medicine with mind-body practices offers an opportunity for “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,” the definition of health by the World Health Organization. 2

This article described evidence supporting the concept that mindful movement is medicine. Scientific evidence supports broad benefits of movement therapy, including reduction in pain, stress, and debility, and improvements in range of motion (ROM), strength, balance, coordination, cardiovascular health, physical fitness, mood, and cognition. Compelling evidence demonstrates that movement practices promote optimal health and are integral in the prevention and treatment of many medical conditions.

The Yoga Practice

Yoga is a practice of physical postures, breathing techniques, and sometimes meditation derived from ancient India to promote physiologic and psychological well-being. Many types of yoga have evolved and become widespread in the United States. Although all forms of yoga share a common foundation in ancient philosophy focused on mind-body connection, each style has a different emphasis ( Table 1 ). Styles range from handstand practices that would challenge an Olympic athlete to Kundalini yoga, which involves only poses lying down. Consequently, it may be challenging for a patient to choose the style that best suites his or her needs.

Table 1

Commonly practiced yoga styles

Despite the large variety of yoga classes available, all forms are based in the fundamentals of yoga philosophy that nourish physical and mental wellness, which include the following:

- 1. Asana—physical poses

- 2. Pranayama—breathing techniques

- 3. Meditation

- 4. Advice for ethical lifestyle

- 5. Spiritual practice

Introduction to Yoga Research

There are many research studies highlighting the benefits of yoga on mental health and medical conditions. A bibliometric analysis on yoga as a therapeutic intervention from 1967 to 2013 reported 486 articles published in 217 different peer-reviewed journals and included 28,080 participants from 29 different countries and a vast variety of conditions. 3 Studies in almost every field of medicine examine yoga’s benefits ( Table 2 ). 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 The most studied disorders are in (1) mental health, (2) cardiovascular disease, and (3) respiratory disease. 3

Table 2

Research studies on yoga for many conditions

Research shows that yoga improves physical fitness and cognitive function, and yoga may serve as an effective adjunct treatment of many medical and psychiatric conditions.

The literature demonstrates that yoga is more effective than waitlist control comparisons; however, yoga cannot yet be recommended as an equivalent or superior treatment to standard-of-care physical therapy or traditional exercise. 4 All 13 Cochrane reviews on yoga concluded that further, large-scale, methodological robust trials are required to establish evidence for yoga as a stand-alone treatment. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Accordingly, yoga should be used as a potent therapy in addition to standard care.

Yoga for Oncologic Rehabilitation

The mind-body-spirit connection applied in yoga is particularly valuable for conditions that affect both physical and mental health, such as cancer. Oncologic patients often suffer from long-term psychological distress, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and chronic pain. A recent Cochrane meta-analysis on yoga for breast cancer, the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women worldwide, includes an impressive 24 randomized control trials (RCTs) involving 2166 women. The review recommends yoga as a complementary intervention for improving health-related QOL and reducing fatigue, sleep disturbances, depression, and anxiety. 10 Furthermore, yoga may boost the immune system of oncology patients. Patients with breast cancer in a Hatha yoga program showed decreases in interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1beta cytokine from isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide, and interferon-gamma, suggesting that yoga protects against stress-related immune suppression. 16

Yoga for Mental Health

Mental health influences the effectiveness of rehabilitation treatment plans, and yoga can efficiently address these psychosocial components of care. RCTs establish that the addition of yoga to standard-of-care treatment is more effective in reducing depression symptoms than standard care alone. 10 , 17 Yoga enhances mood through improved regulation of the sympathetic and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal systems. RCTs illustrate that these changes are mediated by decreases in cortisol and autonomic measures, such as heart rate and blood pressure, and upregulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels. 16 Moreover, a longitudinal study found these benefits to mood were sustained at 1 year after only an 8-week yoga intervention. 18 The strongest evidence endorses yoga for depressive symptoms. The evidence on yoga for anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is also encouraging but not definitive due to lack of large-scale RCTs with high methodological and reporting quality. 19

Yoga for Chronic Pain

Chronic pain syndromes are particularly susceptible to exacerbation by psychosocial factors, and yoga mitigates these negative influences by decreasing fear avoidance, increasing self-efficacy, and reducing stress and sleep disturbance. 20 Quality reviews show improvements in function, QOL, and pain level for chronic pain conditions, such as knee osteoarthritis (OA), rheumatoid arthritis, neck pain, headaches, and low back pain. 4 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 One quality study used MRI techniques to show that yoga improves pain tolerance. 25 Yogis tolerated pain more than twice as long as individually matched controls and had more brain matter in areas uniquely correlated to pain tolerance and areas responsible for integrating nociceptive input and parasympathetic activation. This finding of use-dependent hypertrophy suggests a consistent yoga practice improves pain tolerance by teaching different ways to deal with sensory inputs and the potential emotional reactions attached to those inputs. An RCT of yoga for low back pain also highlighted yoga’s impact on neuromodulation. This study demonstrated that yoga led to decreased pain scores, improved ROM, and higher levels of serotonin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (known modulators of nociception). 26

Yoga for Spinal Conditions

More specifically, yoga may improve pain related to spinal conditions due to its focus on postural awareness and correction and subsequent reduction in excess muscle tension. RCTs demonstrated that yoga improved cervical proprioception, ROM, QOL, and mood and reduces pain and associated disability. 21 , 27 Evidence also affirmed that yoga decreased headache frequency, duration, and pain intensity in patients suffering from tension or cervicogenic headaches. 23 Iyengar yoga, which emphasizes precise body alignment, may be the most appropriate style for patients with chronic spine pain who need posture training.

Yoga for Neurologic Rehabilitation

Yoga can also effectively treat debilitating neurologic conditions that are often exacerbated by stress. Studies demonstrate yoga’s alleviating effect on traumatic brain injury, stroke, spinal cord injury, Parkinson disease, dementia, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, and neuropathies. Multiple systematic reviews reproduced improvements in function and mood, using tools such as the Berg Balance Scale, 6-minute walk, Timed Up and Go, State Trait Anxiety Inventory, Geriatric Depression Scale, Stroke Impact Scale, and Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale. 4 , 5 Even patients with paretic neurologic conditions may benefit from yoga. A study revealed that Kundalini yoga, a style that practices only poses lying down, improved both aphasia and fine motor dexterity in stroke patients. 28 In addition, a case study on a man who sustained an incomplete C3-C6 spinal cord injury and underwent a 12-week Hatha yoga practice showed improvements in functional goals, balance, endurance, flexibility, posture, and muscle strength of the hip extensors, hip abductors, and knee extensors. 29 Yoga is also used to reduce seizures triggered by stress. Sahaja yoga, a simple form of meditation, reduced seizures and EEG changes in patients with epilepsy. The potent effect of meditation was attributed to stress reduction, as evidenced by changes in galvanic skin resistance and levels of blood lactate and urinary vanillylmandelic acid, which are objective indicators of stress. 30 , 31

Yoga for Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation

The holistic yoga philosophy promotes a sustainably healthy lifestyle that may be useful for cardiopulmonary rehabilitation patients. A meta-analysis of 44 RCTs found that yoga improved systolic and diastolic blood pressures, heart rate, respiratory rate, waist circumference, waist/hip ratio, cholesterol, triglycerides, hemoglobin A1c, and insulin resistance. 32 The improvements in autonomic measures were attributable to increased parasympathetic activity through upregulation of GABA. This modulation counteracts the excessive activity of the sympathetic nervous system that has been associated with hypertension. 33 Rigorous yoga styles, such as Ashtanga or Vinyasa yoga, are more suitable for cardiovascular fitness, as no reductions in blood pressure were appreciated with Kundalini yoga interventions, which only uses poses lying down. 34

Yoga Therapy in Summary

Yoga is a powerful adjunct tool for health promotion and maintenance and can be used to minimize pharmacologic treatments; alleviate chronic pain; and supplement neurologic, cardiopulmonary, and spinal cord injury rehabilitation. The diversity of yoga styles allows this therapy to be adaptable for a broad variety of ailments and physical abilities. However, this variability also makes it inherently difficult to apply the scientific method standards traditionally used for validating treatments. Clinical trials cannot blind yoga participants, which makes this research intrinsically susceptible to bias and not amenable to the gold standard of double-blinded RCTs. Yoga is highly supported as a safe and effective remedy for a plethora of conditions but cannot yet be recommended as a stand-alone treatment until stronger evidence is established. Research urges that additional high-quality RCTs are needed to improve confidence in estimates of effect, to evaluate long-term outcomes, and to provide additional information on comparisons between yoga and other exercise.

The Pilates Method

Pilates is low-impact exercise based on holistic movement principles including concentration, centering, control, breathing, precision, and flow ( Table 3 ). 35 Its mindful approach stimulates awareness of body structure, muscle recruitment, body alignment during movement, and posture awareness and control and stabilizes the core muscles during dynamic movement. 36 Pilates uses isokinetic exercises with resistance to strengthen deep muscle groups. In contrast to yoga, there are only 2 major forms of Pilates ( Table 4 ).

Table 3

Key principles of the Pilates method

Table 4

Types of Pilates

Introduction to Pilates Research

Research supports Pilates ability to improve pain, function, psychological health, and kinesiophobia in people with disability. 37 , 38 Systematic reviews have investigated the effectiveness of Pilates on health outcomes related to body compositions, low back pain, breast cancer rehabilitation, physical fitness and fall prevention in seniors, and pelvic floor muscle function. 36 , 39 However, the benefits of Pilates are considerably less established in the literature when compared with the thousands of research articles examining yoga.

Pilates for Low Back Pain

Of the limited Pilates research, the strongest evidence suggests that Pilates effectively treats low back pain. This style of exercise builds lumbar stability and incorporates posture training and thus may alleviate low back pain using the same strategies as conventional evidence-based physical therapy programs. Pilates activates deep abdominal muscles for core strengthening and focuses on precise body alignment and awareness, resulting in a physique that mediates low back pain. The resultant physical changes identified in studies include increased rectus abdominis strength, elimination of muscular asymmetries in transversus abdominis and obliques, improved isolation of transversus abdominis, improved spinal stability with limb loading, improved hamstring flexibility, and improved abdominal muscular endurance. 40 The design of the Pilates method is highly compatible to the treatment of low back pain disorders. These exercises use a recruitment pattern of the abdominal muscles that may be particularly efficacious. A study examining activation of the transversus abdominis, a primary contributor to spine stability, found Pilates practitioners performed significantly better on transversus abdominis isolation and lumbopelvic stability testing compared with the group that trained with standard abdominal crunches. 41 Another RCT compared Pilates against aerobic exercise and proposed that Pilates is a more effective treatment of low back pain and disability because the exercises are targeted to the muscles of pelvis and trunk. 42 Research also identified higher patient satisfaction and compliance with Pilates programs compared with traditional back school. 40

Pilates Therapy in Summary

Although the Pilates method was established over a hundred years ago, there is a paucity of scientific experiment examining its health effects. The existing studies, along with established biomechanical theory, suggest Pilates is an effective treatment of low back disorders; however, the current evidence is not strong enough to be conclusive. 43 Consequently, Pilates is recommended as a powerful supplement (not replacement) to traditional physical therapy programs for low back pain.

The Tai Chi Practice

Tai chi is a Chinese, meditative, martial arts practice designed to gently strengthen and relax the body and mind. It is a system featuring coordinated movements, meditation, and purposeful breathing that is believed to help unlock the body’s Qi ( Table 5 ). 44 Qi is the energy source that is believed to flow throughout every person’s body and accounts for physical, mental, and spiritual health. When Qi becomes “unbalanced or blocked,” pain and sickness result. 45 Tai chi is the process by which each person’s Qi can be restored, generating improved functional capacity, balance, stress reduction, and enhancement of peacefulness, healing, and life-expectancy. 46

Table 5

Key characteristics of tai chi

Introduction to Tai Chi Research

Ancient tai chi is known for its complex, choreographed movement patterns that can take years to master. Given its accessibility to a wide age range, low cost, and theoretic benefit to functional ability and general health, a standardized and simplified form of tai chi was sought. In 2003, an expert panel on tai chi agreed that a simplified, standardized practice could be used for the general population. 46 There are now more than 500 trials and 120 systematic reviews over the past 45 years on the health benefits of tai chi. 44

Tai Chi for Fall Prevention

The strongest evidence supports tai chi for fall prevention. Many strategies have been investigated, including various exercise modalities, vitamin supplementation, medication reconciliation, and vision screening or cataract surgery. 47 A Cochrane review on tai chi exercise and falls found high-certainty evidence that tai chi reduces the number of falls in elderly by 20% compared with controls. 48 In addition, a systematic review comparing the most common approaches to prevent falls found that tai chi is the most cost-effective fall prevention strategy. 47 Similarly, there is strong evidence that tai chi improves balance and reduces falls in patients with Parkinson disease. 44 , 49 , 50 Meta-analyses also suggest a possible role for tai chi in stroke rehabilitation to improve balance and gait and prevent falls. 44 , 51 , 52 Further, studies indicate tai chi may reduce fractures, a common consequence of falls, by improving bone mineral density in osteoporosis. A clinical trial demonstrated statistically significant improvements after 9 months, with participation in at least 75% of classes, suggesting results may depend on length and compliance with intervention. 44 These promising results are attributed to tai chi’s ability to reduce the fear of falling and improve lower extremity strength, aerobic capacity, flexibility, and static and dynamic balance. 44 , 53 , 54

Tai Chi for Chronic Pain

Tai chi’s integrative approach is recommended in current guidelines for reducing chronic general musculoskeletal pain and associated disability. 55 Tai chi significantly reduces pain in patients with OA and is recommended by American College of Rheumatology for knee and hip OA. 56 Tai chi may also improve pain and QOL for patients with fibromyalgia. An RCT on fibromyalgia revealed that tai chi was superior to aerobic exercise, the current first-line exercise treatment. 44 , 57 This advantage could be attributed to the biopsychosocial care tai chi offers over conventional aerobic exercise.

Tai Chi Therapy in Summary

The highest quality evidence supports tai chi for fall prevention in community dwelling elderly and patients with Parkinson disease. These results are especially important given that tai chi has minimal adverse events and has the potential to reduce health care costs. 44 Research suggests the benefits of tai chi may apply to a wider range of conditions, including depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, sleep disturbance, schizophrenia, rheumatoid arthritis, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, and immune disorders. 44 , 58 However, there is a lack of conclusive evidence broadening the utility of tai chi due to small study size and methodological heterogeneity. Improvements must be made in standardizing tai chi class type, length of treatment, and assessing the long-term effects. 44

The Qigong Practice

Qigong is another “moving” mindfulness practice that originated from traditional Chinese medicine. 58 Similar to tai chi, qigong uses the “mind” (or concentration) to coordinate breathing and smooth movements that promote the circulation of Qi. 46 There are several forms of qigong performed standing, sitting, or lying down with little to no movement. The forms make qigong adaptable to persons of any fitness level, age, income, or physical ability. 45

Qigong Research

Tai chi and qigong practices are so similar that they are often grouped together in research studies as tai chi and qigong (TCQ). 58 Correspondingly, systematic reviews on qigong establish comparable improvements in fall risk, depression, and QOL. A Cochrane review on TCQ for individuals with cancer showed an integrative approach resulted in broad benefits to both psychological and physical health. TCQ led to improvements in sleep disturbance, depression, fatigue, pain, and QOL. TCQ may even have a role in reducing the inflammatory response that causes progression of cancer. 58

Qigong Therapy in Summary

A comprehensive review by the National Institutes of Health on TCQ shows consistent, significant results for several health benefits in RCTs and infers equivalence of the 2 mindful martial arts practices. 46

Feldenkrais

The feldenkrais method.

The Feldenkrais method (FM), founded by a physicist and engineer, is a system that uses movement exploration for somatic learning through 2 major techniques ( Table 6 ). 59 Series of movements force the practitioner to use body sensation and perceptual feedback to choose between favorable (easy, comfortable) and unfavorable (painful, straining) positions. With practice, discernment between favorable and unfavorable movements improves, and movement modifications develop and become engrained. The FM fosters self-efficacy in a group setting and theoretically provides sustained health benefits. 60

Table 6

Feldenkrais techniques

Feldenkrais Research

Although often compared with TCQ, the health benefits of Feldenkrais are less established in research studies. Despite this, the FM is used to modify motor behavior of people ranging in age and ability. An RCT demonstrated that Feldenkrais resulted in more relaxed supine posture due to changes in muscle tone. This study implied that Feldenkrais may alleviate chronic tension based pain. 59 A second RCT showed the FM has comparable efficacy to back school for the treatment of chronic low back pain. 61 Another RCT found improvements in balance testing in middle-aged individuals with intellectual disability. Given the commonality of functional decline in this population, Feldenkrais may play a role in improving physical activity and maintaining a level of independence in patients with intellectual disability. 62

Feldenkrais Therapy in Summary

The FM has broad applications for changing bodily perceptions; easing function; and promoting awareness, self-efficacy, and health. Yet, there is a paucity of scientific evidence validating the benefits of Feldenkrais. At this time, clinicians may only offer Feldenkrais as a supplementary therapy to patients interested in efficient physical performance and self-efficacy. 60

Ancient philosopher Plato posed, “Lack of activity destroys the good condition of every human being, while movement and methodical physical exercise save it and preserve it.” 63 Current research advances this aged notion, “exercise is medicine,” and contends that mindful movement is effective whole-person medicine. Movement-based therapies (1) decrease fear avoidance and empower individuals to take a proactive role in their own health and wellness; (2) can benefit patients of any ability; practices are customizable to the individual’s needs and health; (3) are safe, cost-effective, and potent adjunct treatments used to supplement (not replace) standard care; (4) deliver patient-centered, integrative care that accounts for the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of health and illness; (5) and have diverse, evidence-based benefits, including reduction in pain, stress, and debility and improvements in ROM, strength, balance, coordination, cardiovascular health, physical fitness, mood, and cognition.

Strong Evidence for Mind-Body Therapies