Ch. 8 The Middle Ages in Europe

Learning objective.

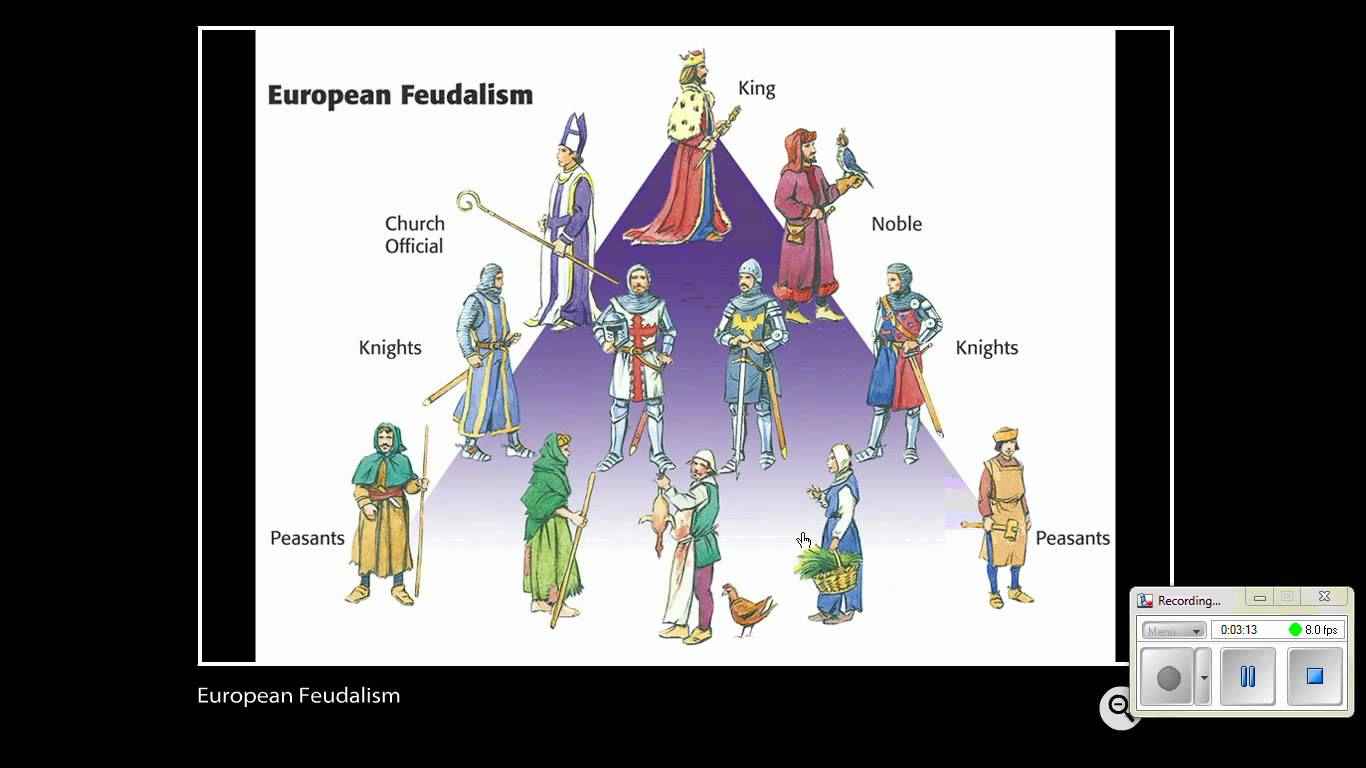

- Recall the structure of the feudal state and the responsibilities and obligations of each level of society

- Feudalism flourished in Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries.

- Feudalism in England determined the structure of society around relationships derived from the holding and leasing of land, or fiefs .

- In England, the feudal pyramid was made up of the king at the top with the nobles, knights, and vassals below him.

- Before a lord could grant land to a tenant he would have to make him a vassal at a formal ceremony. This ceremony bound the lord and vassal in a contract.

- While modern writers such as Marx point out the negative qualities of feudalism, such as the exploitation and lack of social mobility for the peasants, the French historian Marc Bloch contends that peasants were part of the feudal relationship; while the vassals performed military service in exchange for the fief, the peasants performed physical labour in return for protection, thereby gaining some benefit despite their limited freedom.

- The 11th century in France saw what has been called by historians a “feudal revolution” or “mutation” and a “fragmentation of powers” that increased localized power and autonomy.

In the Middle Ages this was the ceremony in which a feudal tenant or vassal pledged reverence and submission to his feudal lord, receiving in exchange the symbolic title to his new position.

An oath, from the Latin fidelitas (faithfulness); a pledge of allegiance of one person to another.

Persons who entered into a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe.

Heritable property or rights granted by an overlord to a vassal.

mesne tenant

A lord in the feudal system who had vassals who held land from him, but who was himself the vassal of a higher lord.

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries. It can be broadly defined as a system for structuring society around relationships derived from the holding of land, known as a fiefdom or fief, in exchange for service or labour.

The classic version of feudalism describes a set of reciprocal legal and military obligations among the warrior nobility, revolving around the three key concepts of lords, vassals, and fiefs. A lord was in broad terms a noble who held land, a vassal was a person who was granted possession of the land by the lord, and a fief was what the land was known as. In exchange for the use of the fief and the protection of the lord, the vassal would provide some sort of service to the lord. There were many varieties of feudal land tenure, consisting of military and non-military service. The obligations and corresponding rights between lord and vassal concerning the fief formed the basis of the feudal relationship.

Feudalism, in its various forms, usually emerged as a result of the decentralization of an empire, especially in the Carolingian empires, which lacked the bureaucratic infrastructure necessary to support cavalry without the ability to allocate land to these mounted troops. Mounted soldiers began to secure a system of hereditary rule over their allocated land, and their power over the territory came to encompass the social, political, judicial, and economic spheres.

Many societies in the Middle Ages were characterized by feudal organizations, including England, which was the most structured feudal society, France, Italy, Germany, the Holy Roman Empire, and Portugal. Each of these territories developed feudalism in unique ways, and the way we understand feudalism as a unified concept today is in large part due to critiques after its dissolution. Karl Marx theorized feudalism as a pre-capitalist society, characterized by the power of the ruling class (the aristocracy) in their control of arable land, leading to a class society based upon the exploitation of the peasants who farm these lands, typically under serfdom and principally by means of labour, produce, and money rents.

While modern writers such as Marx point out the negative qualities of feudalism, the French historian Marc Bloch contends that peasants were an integral part of the feudal relationship: while the vassals performed military service in exchange for the fief, the peasants performed physical labour in return for protection, thereby gaining some benefit despite their limited freedom. Feudalism was thus a complex social and economic system defined by inherited ranks, each of which possessed inherent social and economic privileges and obligations. Feudalism allowed societies in the Middle Ages to retain a relatively stable political structure even as the centralized power of empires and kingdoms began to dissolve.

Structure of the Feudal State in England

Feudalism in 12th-century England was among the better structured and established systems in Europe at the time. The king was the absolute “owner” of land in the feudal system, and all nobles, knights, and other tenants, termed vassals, merely “held” land from the king, who was thus at the top of the feudal pyramid.

Below the king in the feudal pyramid was a tenant-in-chief (generally in the form of a baron or knight), who was a vassal of the king. Holding from the tenant-in-chief was a mesne tenant—generally a knight or baron who was sometimes a tenant-in-chief in their capacity as holder of other fiefs. Below the mesne tenant, further mesne tenants could hold from each other in series.

Before a lord could grant land (a fief) to someone, he had to make that person a vassal. This was done at a formal and symbolic ceremony called a commendation ceremony, which was composed of the two-part act of homage and oath of fealty. During homage, the lord and vassal entered into a contract in which the vassal promised to fight for the lord at his command, while the lord agreed to protect the vassal from external forces.

Roland pledges his fealty to Charlemagne. Roland (right) receives the sword, Durandal, from the hands of Charlemagne (left). From a manuscript of a chanson de geste, c. 14th Century.

Once the commendation ceremony was complete, the lord and vassal were in a feudal relationship with agreed obligations to one another. The vassal’s principal obligation to the lord was “aid,” or military service. Using whatever equipment the vassal could obtain by virtue of the revenues from the fief, he was responsible for answering calls to military service on behalf of the lord. This security of military help was the primary reason the lord entered into the feudal relationship. In addition, the vassal could have other obligations to his lord, such as attendance at his court, whether manorial or baronial, or at the king’s court.

The vassal’s obligations could also involve providing “counsel,” so that if the lord faced a major decision he would summon all his vassals and hold a council. At the level of the manor this might be a fairly mundane matter of agricultural policy, but could also include sentencing by the lord for criminal offenses, including capital punishment in some cases. In the king’s feudal court, such deliberation could include the question of declaring war. These are only examples; depending on the period of time and location in Europe, feudal customs and practices varied.

Feudalism in France

In its origin, the feudal grant of land had been seen in terms of a personal bond between lord and vassal, but with time and the transformation of fiefs into hereditary holdings, the nature of the system came to be seen as a form of “politics of land.” The 11th century in France saw what has been called by historians a “feudal revolution” or “mutation” and a “fragmentation of powers” that was unlike the development of feudalism in England, Italy, or Germany in the same period or later. In France, counties and duchies began to break down into smaller holdings as castellans and lesser seigneurs took control of local lands, and (as comital families had done before them) lesser lords usurped/privatized a wide range of prerogatives and rights of the state—most importantly the highly profitable rights of justice, but also travel dues, market dues, fees for using woodlands, obligations to use the lord’s mill, etc. Power in this period became more personal and decentralized.

- Boundless World History. Authored by : Boundless. Located at : https://www.boundless.com/world-history/textbooks/boundless-world-history-textbook/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Feudalism

Introduction, general overviews.

- History of the Term

- French Historians

- British Historians

- German Historians

- Italian Historians

- Eleventh Century

- Vassal Homage

- Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

- “Feudalism” Under Charles Martel?

- Eleventh-Century Transformations

- The “Feudal Revolution”

- Feudalism and the Nobility

- Feudalism and Women

- Feudalism and Chivalry

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- English Kings and Monarchy, 1066-1485

- Slavery in Medieval Europe

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Chronicles (Anglo-Norman and Continental French)

- Chronicles (East Norse, Rhymed Chronicles)

- Middle English Lyric

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Feudalism by Constance B. Bouchard LAST REVIEWED: 06 February 2012 LAST MODIFIED: 06 February 2012 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195396584-0018

“Feudalism” is a term that has confused more than clarified the nature of medieval society. Until quite recently scholars attempted to create a paradigm of “feudalism” that would combine privileges for the elite few with lordship over the peasantry and (usually) a breakdown in centralized government. But as Elizabeth A. R. Brown first convincingly demonstrated, a term with such varied and noncongruent social, legal, political, and economic meanings—especially when applied to institutions that developed a millennium or more apart—hampers real understanding of the Middle Ages. In the last twenty years numerous discussions of “feudalism” have gone over the same ground, pointing out the difficulties with trying to use the term—although even now some scholars still try to retain it. Nonetheless, even if “feudalism” is nothing but a confusing construct, medieval fiefs were real—if not nearly as ubiquitous as once thought.

“Feudalism” is not a medieval term and not even a translation of a medieval concept ( Abels 2010 ; Brown 2010 ; Bouchard 1998 ). It was first coined long after the Middle Ages were over and originally meant the granting of a fief ( feudum in medieval Latin), that is, land given in return for loyalty, by one aristocrat to another. But soon grafted onto this term were many divergent—indeed, contradictory—meanings. It has been used to mean servile peasant status, or the private administration of justice, or battles fought on horseback, or fragmented governmental authority, or special privileges for a hereditary elite. It has been called a social system, a legal system, a form of military service, and a type of economic organization. Brown 1974 , Reynolds 1994 , and Reynolds 1997 argue convincingly for jettisoning such a confusing word, even though some ( Abels 2010 , White 2005 ) still feel the term can be useful if narrowly defined.

Abels, Richard. Feudalism . 2010.

Provides a succinct, modern overview of the different ways “feudalism” has been used by different scholars. Attempts to retain the term to mean social and political ties among a warrior aristocracy, who exercised public power as private individuals.

Bouchard, Constance Brittain. “Strong of Body, Brave and Noble”: Chivalry and Society in Medieval France . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998.

Includes a critique of the concept of feudalism in the context of a discussion of knights and chivalry.

Brown, Elizabeth A. R. “The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe.” American Historical Review 79 (1974): 1063–1088.

DOI: 10.2307/1869563

The fundamental article on why the term “feudalism” should be jettisoned.

Brown, Elizabeth A. R. Feudalism . 2010.

A concise overview of the term and its uses, incorporating the most recent scholarship; from the online Encyclopedia Britannica .

Reynolds, Susan. Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted . Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Continues the critique of the concept of feudalism begun by Brown 1974 . Densely written and somewhat controversial, yet extremely influential.

Reynolds, Susan. Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300 . 2d ed. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

An effort to provide an alternate theoretical framework to replace feudalism when discussing ties between different sectors of medieval society. Originally published in 1984.

White, Stephen D. Re-Thinking Kinship and Feudalism in Early Medieval Europe . Aldershot, UK, and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2005.

This collection of articles by a legal historian seeks to retain narrowly defined feudalism as a useful analytic category, while considering its relationship to kinship structures.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Medieval Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Aelred of Rievaulx

- Alcuin of York

- Alexander the Great

- Alfred the Great

- Alighieri, Dante

- Ancrene Wisse

- Angevin Dynasty

- Anglo-Norman Realm

- Anglo-Saxon Art

- Anglo-Saxon Law

- Anglo-Saxon Manuscript Illumination

- Anglo-Saxon Metalwork

- Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture

- Apocalypticism, Millennialism, and Messianism

- Archaeology of Southampton

- Armenian Art

- Art and Pilgrimage

- Art in Italy

- Art in the Visigothic Period

- Art of East Anglia

- Art of London and South-East England, Post-Conquest to Mon...

- Arthurian Romance

- Attila And The Huns

- Auchinleck Manuscript, The

- Audelay, John

- Augustodunensis, Honorius

- Bartholomaeus Anglicus

- Benedictines After 1100

- Benoît de Sainte Maure [113]

- Bernard of Clairvaux

- Bernardus Silvestris

- Biblical Apocrypha

- Birgitta of Sweden and the Birgittine Order

- Boccaccio, Giovanni

- Bokenham, Osbern

- Book of Durrow

- Book of Kells

- Bozon, Nicholas

- Byzantine Art

- Byzantine Manuscript Illumination

- Byzantine Monasticism

- Calendars and Time (Christian)

- Cambridge Songs

- Capgrave, John

- Carolingian Architecture

- Carolingian Era

- Carolingian Manuscript Illumination

- Carolingian Metalwork

- Carthusians and Eremitic Orders

- Cecco d’Ascoli (Francesco Stabili)

- Charlemagne

- Charles d’Orléans

- Charters of the British Isles

- Chaucer, Geoffrey

- Christian Mysticism

- Christianity and the Church in Post-Conquest England

- Christianity and the Church in Pre-Conquest England

- Christina of Markyate

- Chronicles of England and the British Isles

- Church of the Holy Sepulchre, The

- Cistercian Architecture

- Cistercians, The

- Clanvowe, John

- Classics in the Middle Ages

- Cloud of Unknowing and Related Texts, The

- Constantinople and Byzantine Cities

- Contemporary Sagas (Bishops’ sagas and Sturlunga saga)

- Corpus Christi

- Councils and Synods of the Medieval Church

- Crusades, The

- Crusading Warfare

- da Barberino, Francesco

- da Lentini, Giacomo

- da Tempo, Antonio and da Sommacampagna, Gidino

- da Todi, Iacopone

- Dance of Death

- d’Arezzo, Ristoro

- de la Sale, Antoine

- de’ Rossi, Nicolò

- de Santa Maria, Cantigas

- Death and Dying in England

- Decorative Arts

- delle Vigne, Pier

- Drama in Britain

- Dutch Theater and Drama

- Early Italian Humanists

- Economic History

- Eddic Poetry

- England, Pre-Conquest

- England, Towns and Cities Medieval

- English Prosody

- Exeter Book, The

- Family Letters in 15th Century England

- Family Life in the Middle Ages

- Feast of Fools

- Female Monasticism to 1100

- Findern Manuscript (CUL Ff.i.6), The

- Folk Custom and Entertainment

- Food, Drink, and Diet

- Fornaldarsögur

- French Drama

- French Monarchy, The

- French of England, The

- Froissart, Jean

- Games and Recreations

- Gawain Poet, The

- German Drama

- Gerson, Jean

- Glass, Stained

- Gower, John

- Gregory VII

- Hagiography in the Byzantine Empire

- Handbooks for Confessors

- Hardyng, John

- Harley 2253 Manuscript, The

- Hiberno-Latin Literature

- High Crosses

- Hilton, Walter

- Historical Literature (Íslendingabók, Landnámabók)

- Hoccleve, Thomas

- Hood, Robin

- Hospitals in the Middle Ages

- Hundred Years War

- Hungary, Latin Literacy in Medieval

- Hungary, Libraries in Medieval

- Illuminated Manuscripts

- Illustrated Beatus Manuscripts

- Insular Art

- Insular Manuscript Illumination

- Islamic Architecture (622–1500)

- Italian Cantari

- Italian Chronicles

- Italian Drama

- Italian Mural Decoration

- Italian Novella, The

- Italian Religious Writers of the Trecento

- Italian Rhetoricians

- Jewish Manuscript Illumination

- Jews and Judaism in Medieval Europe

- Julian of Norwich

- Junius Manuscript, The

- King Arthur

- Kings and Monarchy, 1066-1485, English

- Kings’ Sagas

- Knapwell, Richard

- Lancelot-Grail Cycle

- Late Medieval Preaching

- Latin and Vernacular Song in Medieval Italy

- Latin Arts of Poetry and Prose, Medieval

- Latino, Brunetto

- Learned and Scientific Literature

- Libraries in England and Wales

- Lindisfarne Gospels

- Liturgical Drama

- Liturgical Processions

- Lollards and John Wyclif, The

- Lombards in Italy

- London, Medieval

- Love, Nicholas

- Low Countries

- Lydgate, John

- Machaut, Guillaume de

- Magic in the Medieval Theater

- Maidstone, Richard

- Malmesbury, Aldhelm of

- Malory, Sir Thomas

- Manuscript Illumination, Ottonian

- Marie de France

- Markets and Fairs

- Masculinity and Male Sexuality in the Middle Ages

- Medieval Archaeology in Britain, Fifth to Eleventh Centuri...

- Medieval Archaeology in Britain, Twelfth to Fifteenth Cent...

- Medieval Bologna

- Medieval Chant for the Mass Ordinary

- Medieval English Universities

- Medieval Ivories

- Medieval Latin Commentaries on Classical Myth

- Medieval Music Theory

- Medieval Naples

- Medieval Optics

- Mendicant Orders and Late Medieval Art Patronage in Italy

- Middle English Language

- Mosaics in Italy

- Mozarabic Art

- Music and Liturgy for the Cult of Saints

- Music in Medieval Towns and Cities

- Music of the Troubadours and Trouvères

- Musical Instruments

- Necromancy, Theurgy, and Intermediary Beings

- Nibelungenlied, The

- Nicholas of Cusa

- Nordic Laws

- Norman (and Anglo-Norman) Manuscript Ilumination

- N-Town Plays

- Nuns and Abbesses

- Old English Hexateuch, The Illustrated

- Old English Language

- Old English Literature and Critical Theory

- Old English Religious Poetry

- Old Norse-Icelandic Sagas

- Ottonian Art

- Ovid in the Middle Ages

- Ovide moralisé, The

- Owl and the Nightingale, The

- Papacy, The Medieval

- Persianate Dynastic Period/Later Caliphate (c. 800–1000)

- Peter Abelard

- Pictish Art

- Pizan, Christine de

- Plowman, Piers

- Poland, Ethnic and Religious Groups in Medieval

- Pope Innocent III

- Post-Conquest England

- Pre-Carolingian Western European Kingdoms

- Prick of Conscience, The

- Pucci, Antonio

- Pythagoreanism in the Middle Ages

- Rate Manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 61)

- Regions of Medieval France

- Regular Canons

- Religious Instruction (Homilies, Sermons, etc.)

- Religious Lyrics

- Robert Mannyng of Brunne

- Rolle, Richard

- Romances (East and West Norse)

- Romanesque Art

- Rus in Medieval Europe

- Ruthwell Cross

- Sagas and Tales of Icelanders

- Saint Plays and Miracles

- Saint-Denis

- Saints’ Lives

- Scandinavian Migration-Period Gold Bracteates

- Schools in Medieval Britain

- Scogan, Henry

- Sex and Sexuality

- Ships and Seafaring

- Shirley, John

- Skaldic Poetry

- Snorra Edda

- Song of Roland, The

- Songs, Medieval

- St. Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury

- St. Peter's in the Vatican (Rome)

- Syria and Palestine in the Byzantine Empire

- The Middle Ages, The Trojan War in

- The Use of Sarum and Other Liturgical Uses in Later Mediev...

- Theater and Performance, Iberian

- Thirteenth-Century Motets in France

- Thomas Aquinas

- Thornton, Robert

- Tomb Sculpture

- Travel and Travelers

- Trevisa, John

- Troubadours and Trouvères

- Troyes, Chrétien de

- Umayyad History

- Usk, Thomas

- Venerable Bede, The

- Vercelli Book, The

- Vernon Manuscript, The

- Von Eschenbach, Wolfram

- Wall Painting in Europe

- Wearmouth-Jarrow

- Welsh Literature

- William of Ockham

- Women's Life Cycles

- York Corpus Christi Plays

- York, Medieval

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Feudalism and knights in medieval europe.

Viking Sword

Aquamanile in the Form of a Mounted Knight

A Knight of the d'Aluye Family

Michael Norris Department of Education, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2001

From the ninth to the early eleventh centuries, invasions of the Magyars from the east, Muslims from the south, and Vikings from the north struck western Europe. This unrest ultimately spurred greater unity in England and Germany, but in northern France centralized authority broke down and the region split into smaller and smaller political units. By the ninth century, many knights and nobles held estates (fiefs) granted by greater lords in return for military and other service. This feudal system (from the medieval Latin feodum or feudum , fee or fief) enabled a cash-poor but land-rich lord to support a military force. But this was not the only way that land was held, knights maintained, and loyalty to a lord retained. Lands could be held unconditionally, landless knights could be sheltered in noble households, and loyalties could be maintained through kinship, friendship, or wages.

Mounted armored warriors , or knights (from the Old English cniht , boy or servant), were the dominant forces of medieval armies. The twelfth-century Byzantine princess Anna Komnena wrote that the impact of a group of charging French knights “might rupture the walls of Babylon .” At first, most knights were of humble origins, some of them not even possessing land, but by the later twelfth century knights were considered members of the nobility and followed a system of courteous knightly behavior called chivalry (from cheval , the French word for horse). During and after the fourteenth century , weapons that were particularly effective against horsemen appeared on the battlefield, such as the longbow, pike, halberd, and cannon. Yet despite the knights’ gradual loss of military importance, the system by which noble families were identified, called heraldry, continued to flourish and became more complex. The magnificence of their war games—called tournaments—also increased, as did the number of new knightly orders, such as the Order of the Garter.

Norris, Michael. “Feudalism and Knights in Medieval Europe.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/feud/hd_feud.htm (October 2001)

Further Reading

Bennett, Judith M., and C. Warren Hollister. Medieval Europe: A Short History . 10th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Gies, Joseph and Frances Gies. Life in a Medieval Castle . New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Additional Essays by Michael Norris

- Norris, Michael. “ The Papacy during the Renaissance .” (August 2007)

- Norris, Michael. “ Arms and Armor in Medieval Europe .” (October 2001)

- Norris, Michael. “ Life of Jesus of Nazareth .” (originally published June 2008, last revised September 2008)

Related Essays

- Arms and Armor in Medieval Europe

- The Crusades (1095–1291)

- The Decoration of Arms and Armor

- Fashion in European Armor, 1000–1300

- The Function of Armor in Medieval and Renaissance Europe

- The Age of Saint Louis (1226–1270)

- Arms and Armor in Renaissance Europe

- Arms and Armor—Common Misconceptions and Frequently Asked Questions

- Art and Death in the Middle Ages

- Byzantium (ca. 330–1453)

- Courtship and Betrothal in the Italian Renaissance

- The Decoration of European Armor

- Domestic Art in Renaissance Italy

- Famous Makers of Arms and Armors and European Centers of Production

- Fashion in European Armor

- Fashion in European Armor, 1300–1400

- Fashion in European Armor, 1400–1500

- Medieval Aquamanilia

- Nuptial Furnishings in the Italian Renaissance

- Romanesque Art

- Techniques of Decoration on Arms and Armor

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- France, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1000–1400 A.D.

- 10th Century A.D.

- 11th Century A.D.

- 12th Century A.D.

- 13th Century A.D.

- 14th Century A.D.

- 9th Century A.D.

- Frankish Art

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Horse Trappings

- Islamic Art

- Medieval Art

History of Feudal System Compare & Contrast Essay

Feudalism as articulated by f.l. ganshof and l. white, marc bloch on feudalism.

Bibliography

The word ‘feudal’ was created by the Renaissance jurists of Italy to label what they saw as the usual customary law on land. It lacks a clear definition, but it may be inferred from the meaning created by historians, economists and philosophers. It was a social and economic structure defined by hereditary social lines. All these hereditary lines possessed natural, social, and economic benefits and responsibilities.

In this sense, wealth was primarily a creation of the land as a factor of production. However, it had been subjected to the cultured political economy at that time, which saw the serfs till it at the mercy of their lords. This concept is discussed in this paper, as articulated by F.L. Ganshof and Lynn White against the concept of feudalism by Marc Bloch.

Feudalism was regarded as an administrative, martial, and societal creation that brought together the classes of aristocrats in medieval Europe and the vassalage by way of land as the uniting factor.

The principal advocate of this belief was F.L. Ganshof 1 , who viewed feudalism as a creation of the institutions that established and regulated the duties of obedience and service, mostly in military service, from the vassal towards the lord. In addition, there were reciprocal responsibilities of protection and upkeep on the lord the vassal. The lords would give out portions of lands to the vassals as goodies.

These portions of land were commonly known as fiefs. Feudalism to Ganshof was the possession of power by the lords in the form of land and its systematic transmission to the serfs.

Therefore, Ganshof’s observation and opinion were that classes had been effectively created by the feudal system, where the class of the lords or landowners protected and granted tenure of land to the vassals. Conversely, the vassals observed obedience and served the lords. 2

Professor Lynn White, Jr., on her part, spoke of technological determinism. She used a set of writings to create her own compilation in 1962, known as, “Medieval Technology and Social Change”. This pamphlet contained a detailed discussion on technology and recent inventions of the middle ages, but more importantly it had a contentious theory regarding the foregoing issue of feudalism.

White 3 reckons that the presence of technology during this age enabled the growth of the ambition of many lords, who would carry out spontaneous combat attacks on distant lands more easily.

She asserted that this was the impetus that drove a renowned man by the name Charles Martel to fast-track the annexation of lands that were held by the church. The lands were then distributed to his knights, who spent martial lives by buying expensive horses to back him in battle.

Additionally, White 4 argued that there was a swing of political supremacy leaving the Mediterranean end of the planet and moving to the North of Europe. This wave of supremacy occurred as a result of the growing productivity in the technologized regions, whose farming was characterized by implements, such as improved carts for cultivation, improvement in harvest storage facilities, as well as industrialization.

These developments brought about a triple-annual harvest rotation for the lands. Professor White similarly studied the medieval machinery that improved motion and energy. All of this is what White refers to as the technological determinism of the people as a result of their empowerment for better lives through technological advancements. 5

Unlike the above two philosophers who wrote their opinions earlier in the ages, Marc Bloch came at a time when there was a doubling of people in the western European region, the agrarian revolution which had a three crop rotation, heavyweight ploughs, horse carts, and the windmills. All these technological advancements were used for the growth and advancement of food production.

Similarly, there was a huge growth in trade, which led to the development of urban areas and the rebirth of a cash economy. 6 The progress that was achieved economically helped the rulers in Europe to get more power and developed the modern Europe.

As a result, Marc had to define feudalism according to his age and times. In 1939, he described the “feudal society” as where class was not determined as superior based on the earnings of its members, but its warrior supremacy. The warrior classes were closely knit.

Fragmentations led to disorder, but the family set up and the state helped maintain the ties, with the state during the feudal age seeking to restore the tight bonds in society. 7

In contrast to the above two writers, Marc described the feudal system as a fundamentally dysfunctional system that brought about many vices and a huge disparity in the lives and the classes of the people.

Though both F.L. Ganshof and Lynn White had criticized the structure and working of feudalism, unlike Marc, they did not view it as a failed system that ‘led inevitably to disorder’. Instead, they viewed the feudal system as inevitable in the system of life of the day and saw it as the default economic system. 8

Bloch, Marc. Feudal Society . New York: Routledge, 2014.

Ganshof, François Louis. “II. Benefice and Vassalage in the Age of Charlemagne.” Cambridge Historical Journal 6, no. 02 (1939): 147-175.

White, Lynn Townsend. Medieval Technology and Social Change, Vol. 163. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964.

1 Louis François Ganshof, “II Benefice and Vassalage in the Age of Charlemagne,” Cambridge Historical Journal 6, no. 02 (1939), 147-175.

2 Louis François Ganshof, “II Benefice and Vassalage in the Age of Charlemagne,” Cambridge Historical Journal 6, no. 02 (1939), 147-175.

3 Townsend Lynn White, Medieval Technology and Social Change, Vol. 163 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964)

6 Marc, Bloch, Feudal Society (New York: Routledge, 2014)

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, December 24). History of Feudal System. https://ivypanda.com/essays/feudal-system/

"History of Feudal System." IvyPanda , 24 Dec. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/feudal-system/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'History of Feudal System'. 24 December.

IvyPanda . 2019. "History of Feudal System." December 24, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/feudal-system/.

1. IvyPanda . "History of Feudal System." December 24, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/feudal-system/.

IvyPanda . "History of Feudal System." December 24, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/feudal-system/.

- Feudalism System of Western Europe in the Middle Ages

- The Serfs in Poland

- Portland Food Carts Popularity and Effects

- Feudalism in Europe in the "Beowulf" Poem

- Klimt's "The Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I" and "The Kiss"

- Western Civilization in the Middle Ages

- Justification, Limitations, and Exercise of Authority in Feudal Japan

- The Epic Poem "The Song of Roland"

- The Development of Feudalism and Manorialism in the Middle Ages

- “Religion a Figment of Human Imagination” by Andy Coghlan

- "The Thatcher Revolution" by Earl A. Reitan

- "British Society Since 1945: The Penguin Social History of Britain" by Arthur Marwick

- Nationalism and Its 19th Century History From a Moral and Functional Perspective

- Nationalism and Its 19th Century History

- To What Extent did Hitler Rule Germany with Popular Consent?

Feudalism in Europe: Definition, Origin and End of Feudalism

Europe passed through lawlessness after the death of Charlemagne. Robbery, instability and social disparity became orders of the day after the fall of Roman Empire.

Taking chance of this lawlessness, the foreign invaders looted different kingdoms of Europe. This created utter helplessness among the subjects.

They now sought the help of powerful men for the protection of their life and property. This gave rise to ‘Feudalism’ in Europe.

Image Source: i.ytimg.com/vi/CuQhFarIWso/maxresdefault.jpg

Definition of Feudalism:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Feudalism was a kind of socio-political organisation which arose in medieval Europe and was based on land tenure given by the Lord to the Vassels, who served their masters in varous ways. In other words, feudalism was a part of the feudal society where the subordinate subjects showed loyalty to their Lords and obtained from them a piece of land there by serving their master, in various ways seeking protection from them for their life and property.

The origin of feudalism was not sudden. This situation arose in Egypt after the end of the ‘Old Kingdom’. Ancient Greece witnessed this situation during the ‘Age of Homer’. This system prevailed in Roman Society in which the weaker section appealed to the rich people to save them from peril and showed allegience to their masters.

This system was reflected through the procedure of Comitatus. In this system the young fighters engaged themselves in the service of a powerful leader and performed their duty as per the instruction of that leader. In fifth Century A.D. feudalism appeared in the Prankish Kingdom where a bond was created between the ruler and his supporters.

With the expansion of the Frankish Kingdom, feudalism spread to Italy, Spain, Germany and other Countries. Feudalism exerted its influence in the entire medieval Europe.

The Basic Principles of Feudalism:

Feudalism was based on certain principles. In medieval Europe, the weak and innocent people needed the help of a powerful man. The king was very weak. He could not save his subjects from the plunders of the foreign invaders. So, the common people turned to strong and powerful leaders who were mostly the descendants of the Dukes, Counts and Margraves to make their life and property safe.

The protector was variously known as the ‘Lord’, ‘Liege Lord’, ‘Suzerain’ or ‘Seignior’. The people who sought his protection were called the ‘Vassals’ or ‘Liege-men’. The Lord gave back the plot of land known as Tier to his vassal. In some places, instead of the word ‘fief, the word ‘Feud’ was used from which the term ‘Feudalism’ was derived.

End of Feudalism:

In due course of time, Feudalism lost its relevance for the European countries. The Kings increased their power and gave protection to their subjects. So, the necessity of feudal Lords was not felt in the society. When the lot of the cities improved through trade and commerce, they paid back money to the feudal Lords and became free from them. The great Plague took a heavy total of life in the area stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to the Baltic Ocean.

When there was a shortage of people to perform cultivation work, the feudal Lords were compelled to resort to rearing of sheep. The use of gun-powder made the King more powerful and the feudal Lords could not be a match to them. The invention of printing machine and the progress of education changed the outlook of the people who relegated feudalism to distant background. For these reasons, feudalism in Europe came to an end.

Related Articles:

- Feudalism: Top 9 Features of Feudalism – Explained!

- What are the Merits and Demerits of Feudalism?

- The Medieval Towns of Europe

- Medieval Universities of Italy: Origin and Importance

Home — Essay Samples — Life — History of Taekwondo — Feudalism in Ancient China

Feudalism in Ancient China

- Categories: Feudalism Gender Equality History of Taekwondo

About this sample

Words: 715 |

Published: Mar 16, 2024

Words: 715 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Origins and development, key characteristics, impact on chinese history and culture.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Social Issues Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1061 words

1 pages / 507 words

2 pages / 908 words

1 pages / 647 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on History of Taekwondo

Fordlandia, a small town in the heart of the Amazon rainforest, was established by American industrialist Henry Ford in the 1920s. The project aimed to create a self-sustaining rubber plantation to supply Ford's automobile [...]

"Killing Lincoln" is a book written by Bill O'Reilly and Martin Dugard that explores the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. The authors provide a detailed account of the events leading up to and following the tragic [...]

Andrew Jackson, the seventh President of the United States, is a figure often associated with the rise of democracy in America. His presidency, from 1829 to 1837, marked a significant shift in American politics and governance, [...]

American imperialism was driven by a combination of political, economic, and ideological motivations. Politically, the United States sought to expand its influence and power on the global stage. As European powers carved up [...]

Taekwondo is a martial art form that was founded on April 11, 1955, by the South Korean army general Choi Hong Hee. In Korean Tae (Tae) means kicking, Quon means fist or hand kicks, Do is the way. So there are two components of [...]

This is a description of a single case evaluation examining a relationship between stress during a test before practicing yoga and after practicing yoga. A single case evaluation is defined as a time series design used to [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Haiti That Still Dreams

By Edwidge Danticat

I often receive condolence-type calls, e-mails, and texts about Haiti. Many of these messages are in response to the increasingly dire news in the press, some of which echoes what many of us in the global Haitian diaspora hear from our family and friends. More than fifteen hundred Haitians were killed during the first three months of this year, according to a recent United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights report, which described the country’s situation as “ cataclysmic .” Women and girls are routinely subjected to sexual violence. Access to food, water, education, and health care is becoming more limited, with more than four million Haitians, around a third of the population, living with food insecurity, and 1.4 million near starvation. Armed criminal groups have taken over entire neighborhoods in Port-au-Prince and the surrounding areas, carrying out mass prison breaks and attacks on the city’s airport, seaport, government buildings, police stations, schools, churches, hospitals, pharmacies, and banks, turning the capital into an “ open air prison .”

Even those who know the country’s long and complex history will ask, “Why can’t Haiti catch a break?” We then revisit some abridged version of that history. In 1804, after a twelve-year revolution against French colonial rule, Haiti won its independence, which the United States and several European powers failed to recognize for decades. The world’s first Black republic was then forced to spend sixty years paying a hundred-and-fifty-million francs (now worth close to thirty billion dollars) indemnity to France . Americans invaded and then occupied Haiti for nineteen years at the beginning of the twentieth century. The country endured twenty-nine years of murderous dictatorship under François Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude, until 1986. In 1991, a few months after Haiti’s first democratically elected President, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, took office, he was overthrown in a coup staged by a military whose members had been trained in the U.S. Aristide was elected again, then overthrown again, in 2004, in part owing to an armed rebellion led by Guy Philippe, who was later arrested by the U.S. government for money laundering related to drug trafficking. Last November, six years into his nine-year prison sentence, Philippe was deported by the U.S. to Haiti. He immediately aligned himself with armed groups and has now put himself forward as a Presidential candidate.

In 2010, the country was devastated by a 7.0-magnitude earthquake, which killed more than two hundred thousand people. Soon after, United Nations “peacekeepers” dumped feces in Haiti’s longest river, causing a cholera epidemic that killed more than ten thousand people and infected close to a million. For the past thirteen years, Haiti has been decimated by its ruling party, Parti Haïtien Tèt Kale (P.H.T.K.), which rose to power after a highly contested election in 2011. In that election, the U.S.—then represented by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton—and the Organization of American States helped the candidate who finished in third place, Michel Martelly, claim the top spot. Bankrolled by kidnapping, drug trafficking, business élites, and politicians, armed groups have multiplied under P.H.T.K, committing massacres that have been labelled crimes against humanity. In 2021, a marginally elected President, Jovenel Moïse, was assassinated in his bedroom , a crime for which many of those closest to him, including his wife, have been named as either accomplices or suspects.

The unasked question remains, as W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in “ The Souls of Black Folk ,” “How does it feel to be a problem?”

I deeply honor Haiti’s spirit of resistance and long history of struggle, but I must admit that sometimes the answer to that question is that it hurts. Sometimes it hurts a lot, even when one is aware of the causes, including the fact that the weapons that have allowed gangs to take over the capital continue to flow freely from Miami and the Dominican Republic, despite a U.N. embargo. Internally, the poorest Haitians have been constantly thwarted by an unequal and stratified society, which labels rural people moun andeyò (outside people), and which is suffused with greedy and corrupt politicians and oligarchs who scorn the masses from whose tribulations they extract their wealth.

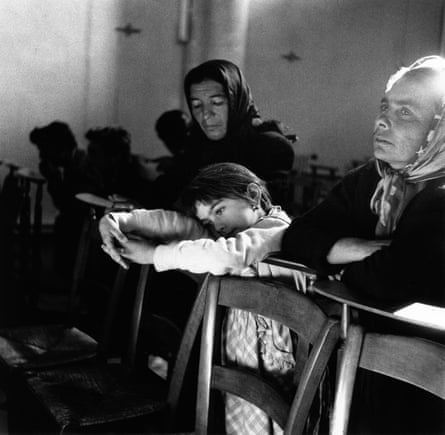

Recently, at a loved one’s funeral, in Michigan, the spectre of other Haitian deaths was once again on the minds of my extended family members. Everywhere we gather, Haiti is with us, as WhatsApp messages continuously stream in from those who chose to stay in Haiti and can’t leave because the main airport is closed, and others who have no other home. In Michigan, during chats between wake, funeral, and repast, elders brought up those who can’t get basic health care, much less a proper burial or any of the rituals that are among our most sacred obligations. “Not even a white sheet over those bodies on the street,” my mother-in-law, who is eighty-nine, said, after receiving yet another image of incinerated corpses in Port-au-Prince. At least after the 2010 earthquake, sheets were respectfully placed on the bodies pulled from the rubble. Back then, she said, the armed young men seemed to have some reverence for life and some fear of death.

Lately, some of our family gatherings are incantations of grief. But they can also turn into storytelling sessions of a different kind. They are opportunities for our elders to share something about Haiti beyond what our young ones, like everyone else, see on the news. The headlines bleed into their lives, too, as do the recycled tropes that paint us as ungovernable, failures, thugs, and even cannibals. As with the prayers that we recite over the dead, words still have power, the elders whisper. We must not keep repeating the worst, they say, and in their voices I hear an extra layer of distress. They fear that they may never see Haiti again. They fear that those in the next generation, some of whom have never been to Haiti, will let Haiti slip away, as though the country they see in the media—the trash-strewn streets and the barricades made from the shells of burnt cars, the young men brandishing weapons of war and the regular citizens using machetes to defend themselves—were part of some horror film that they can easily turn off. The elders remind us that we have been removed, at least physically, from all of this by only a single generation, if not less.

We are still human beings, the elders insist—“ Se moun nou ye .” We are still wozo , like that irrepressible reed that grows all over Haiti. For a brief moment, I think someone might break into the Haitian national anthem or sing a few bars of the folk song “ Ayiti Cheri .” (“Beloved Haiti, I had to leave you to understand.”) Instead, they hum the music that the wozo has inspired : “ Nou se wozo / Menm si nou pliye, nou pap kase. ” Even if we bend, we will not break.

Except we are breaking. “It pains me to see people living in constant fear,” the Port-au-Prince-based novelist and poet Évelyne Trouillot recently wrote to me in an e-mail. “I dream of a country where children are not afraid to dream.” Internationally, U.S. deportations continue , Navy ships are ready to be deployed to intercept migrant boats, and Haitian asylum seekers could once again end up imprisoned on Guantánamo, as they did in the early nineteen-nineties. In conversations, whether with strangers or with younger family members, someone inevitably asks, “Is there any hope?”

I have hope, I say, because I grew up with elders, both in Haiti and here in the U.S., who often told us, “ Depi gen souf gen espwa ”—as long as there’s breath, there’s hope. I have hope, too, because the majority of Haitians are under twenty-five years old, as are many members of our family. Besides, how can we give in to despair with eleven million people’s lives in the balance? Better yet, how can we reignite that communal grit and resolve that inspired us to defeat the world’s greatest armies and then pin to our flag the motto “ L’union fait la force ”? Unity is strength.

The elders also remind us that Haiti is not just Port-au-Prince. As more and more of the capital’s residents are forced to return to homesteads and ancestral villages, the moun andeyò have much to teach other Haitians. “Historically, the moun andeyò have always been the preserver of Haiti’s cultural and traditional ethos,” Vivaldi Jean-Marie, a professor of African American and African-diaspora studies at Columbia University, told me. Rural Haitians, who have lived for generations without the support of the state, have had no choice but to rely on one another in close and extended family structures called lakou . “This shared awareness—I am because we are—will prevail beyond this difficult chapter in Haitian history,” Jean-Marie said.

Finally, I have hope because in Haiti, as the American writer and art collector Selden Rodman has written, “ art is joy .” This remains true even as some of the country’s most treasured cultural institutions, including the National School of the Arts and the National Library, have been ransacked. In the summer of 2023, Carrefour Feuilles, a district in Port-au-Prince that many writers, visual artists, and musicians call home, was attacked by armed criminal groups. The onslaught led to a petition that collected close to five thousand signatures. It read in part, “How many more hundreds of our women and children must be raped, executed, burned before the public authorities do everything possible to put an end to the plague of gangs and their sponsors?”

A few days later, the homes of two of the signatories, the multimedia artist Lionel St. Eloi and the writer Gary Victor, were taken over by a gang. The last time I saw St. Eloi was in 2019, in the courtyard of Port-au-Prince’s Centre d’Art, where he had a series of metal birds on display, their bejewelled bodies and beaks pointing toward the sky. Allenby Augustin, the Centre d’Art’s executive director, recently described how some artists, afraid of having to suddenly flee their homes and leave their work behind, bring their pieces to the center or keep them in friends’ homes in different parts of the city. Others add the stray bullets that land inside their studios— bal pèdi or bal mawon —to their canvasses.

St. Eloi, the patriarch of a family of artists, had lived in Carrefour Feuilles since the seventies, working with young people there. “The youth who were neglected or who could not afford to go to school were taken in by our family,” one of St. Eloi’s sons, the musician Duckyns (Zikiki) St. Eloi, told me. “We taught them to paint, to play guitar, and to play the drums. Now they are hired to run errands for gangsters who put guns in their hands.” In spite of what has happened, he still believes that art can turn some things around. He recently sent me a picture of a work by his younger brother Anthony—an image depicting gang members wearing brightly colored balaclavas and holding pencils, a book, a paint palette, a camera, and a musical instrument. “If there are gangs, we’d be better off with art gangs,” Zikiki said. “Gangs that paint, make music, recite poetry. Art is how we bring our best face to the world. Art is how we dream.” ♦

New Yorker Favorites

A Harvard undergrad took her roommate’s life, then her own. She left behind her diary.

Ricky Jay’s magical secrets .

A thirty-one-year-old who still goes on spring break .

How the greatest American actor lost his way .

What should happen when patients reject their diagnosis ?

The reason an Addams Family painting wound up hidden in a university library .

Fiction by Kristen Roupenian: “Cat Person”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Isaac Chotiner

By Maxine Scates

By Geraldo Cadava

By Gideon Lewis-Kraus

The origin of all things: Kyotographie 2024 – a photo essay

The 12 th annual Kyotographie photography festival features 13 exhibitions staged in striking locations across the Japanese city of Kyoto. Photographers from around the world submitted pictures on the theme of ‘source’

- The Kyotographie international photography festival runs until 12 May

S pring in Kyoto ushers in cherry blossom season, but it also marks the return of one of the biggest photo festivals in Asia. Kyotographie, now in its 12th year, fuses the past and present with its striking images and unique locations. The 13 exhibitions are staged in temples, galleries and traditional private homes across the Japanese city, showcasing the work of national and international photographers.

The festival is loosely centred on a theme – and this year the directors, Lucille Reyboz and Yusuke Nakanishi, asked participants to focus on the word “source” by delving into the essence of beginnings and the nexus of creation and discovery.

The Yamomami struggle. Photograph by Claudia Andujar

The source is the initiator, the origin of all things. It is the creation of life, a place where conflict arises or freedom is obtained; it is the space in which something is found, born or created. It is a struggle Claudia Andujar and the Yanomami shaman and leader Davi Kopenawa know too well. The Yanomami Struggle is the first retrospective exhibition in Japan by the Brazilian artist and activist Andujar with the Yanomami people of Brazil.

It is more than 50 years since she began photographing the Yanomami, the people of the Amazon rainforest near Brazil’s border with Venezuela, an initial encounter that changed their lives. Andujar’s work is not just a showcase of her photographic talent but, with Kopenawa accompanying the exhibition to Japan for the first time, it is a platform to bring the Yanomami’s message to a wider Asian audience.

The Yanomami Struggle. Photograph by Claudia Andujar

The first part of the exhibition features photographs taken by Andjuar in the 1970s, alongside artwork by the Yanomami people and words by Kopenawa. The second part narrates the continuing violence inflicted by non-Indigenous society on the Yanomami. The project is a platform for the Yamomani people to be seen and protected from ongoing threats. The exhibition, curated by Thyago Nogueira from São Paulo’s Instituto Moreira Salles, is a smaller version of one that has been touring the world since 2018.

The Yanomami Struggle, by Claudia Andujar, and artwork by the Yanomami people.

The Moroccan artist Yassine Alaoui Ismaili (Yoriyas) is showing new work made during his Kyotographie artist-in-residence programme for young Africans. The images from the Japanese city feature alongside his project Casablanca Not the Movie.

Children Transform the Sheep for Eid al-Adha into a Playground in Casablanca. Photograph by Yassine Alaoui Ismaili (Yoriyas)

Yoriyas gave up his career as a breakdancer and took up photography as a means of self-expression. His project Casablanca Not the Movie documents the streets of the city where he lives with candid shots and complex compositions. His work, which combines performance and photography, encourages us to focus on how we inhabit urban spaces. The exhibition’s clever use of display and Yoriyas’s experience with choreography force the viewer to see the work at unconventional angles. He says: “The camera frame is like a theatre stage. The people in the frame are my dancers. By moving the camera, I am choreographing my subjects without even knowing it. When an interesting movement catches my eye, I press the shutter. My training has taught me to immediately understand space, movement, connection and story. I photograph in the same way that I choreograph.”

The contrasts in Casablanca take many forms, including social, political, religious and chromatic. Photograph by Yoriyas

From Our Windows is a collaboration bringing together two important Japanese female photographers, both of whom shares aspects of their lives through photography, in a dialogue about different generations. The exhibition is supported by Women in Motion, which throws a spotlight on the talent of women in the arts in an attempt to reach gender equality in the field. Rinko Kawauchi, an internationally acclaimed photographer, chose to exhibit with Tokuko Ushioda who, at 83, continues to create vibrant new works. Kawauchi says of Ushioda: “I respect the fact that she has been active as a photographer since a time when it was difficult for women to advance in society, and that she is sincerely committed to engaging with the life that unfolds in front of her.” This exhibition features photographs taken by each of them of their families.

Photograph by Rinko Kawauchi.

Kawauchi’s two bodies of work, Cui Cui and As It Is, focus on family life. The first series is a family album relating to the death of her grandfather and the second showcases the three years after the birth of her child. Family, birth, death and daily life are threads through both bodies of work that help to create an emotional experience that transcends the generations.

Rinko Kawauchi and Tokuko Ushioda at the Kyoto City Kyocera Museum of Art

Kawauchi says: “My works will be exhibited alongside Ushioda. Each of the works from the two series are in a space that is the same size, located side by side. The works show the accumulation of time that we have spent. They are a record of the days we spent with our families, and they are also the result of facing ourselves. We hope to share with visitors what we have seen through the act of photography, which we have continued to do even though our generations are different, and to enjoy the fact that we are now living in the same era.”

Ushioda’s first solo exhibition features two series: the intimate My Husband and also Ice Box, a fixed-point observation of her own and friends’ refrigerators. Ushioda says: “I worked on that series [Ice Box] for around 20 years or so. Like collecting insects, I took photographs of refrigerators in houses here and there and in my own home, which eventually culminated in this body of work.”

Entries from Tokuko Ushida’s series Ice Box.

James Mollison’s ongoing project Where Children Sleep is on display at the Kyoto Art Centre with a clever display that turns each photograph into its own bedroom.

A child portrayed in Where Children Sleep, Nemis, Canada.

Featuring 35 children from 28 countries, the project encourages viewers to think about poverty, wealth, the climate emergency, gun violence, education, gender issues and refugee crises. Mollison says: “From the start, I didn’t want to think about needy children in the developing world, but rather something more inclusive, about children from all types of situations.” Featuring everything from a trailer in Kentucky during an opioid crisis and a football fan’s bedroom in Yokohama, Japan, to a tipi in Mongolia, the project offers an engrossing look at disparate lives.

From Where Children Sleep, Nirto, Somalia

Joshim, India. Photographs by James Mollison

Phosphor, Art & Fashion (1990-2023) is the first big retrospective exhibition devoted to the Dutch artist Viviane Sassen . It covers 30 years of works, including previously unseen photographs, and combines them with video installations, paintings and collages that showcase her taste for ambiguity and drama in a distinctive language of her own.

Eudocimus Ruber, from the series Of Mud and Lotus, 2017. Photograph by Viviane Sassen and Stevenson

The exhibition opens with self-portraits taken during Sassen’s time as a model. “I wanted to regain power over my own body. With a man behind the camera, a sort of tension always develops, which is often about eroticism, but usually about power,” she says. Sassen lived in Kenya as a child, and the series produced there and in South Africa are dreamlike, bold and enigmatic. She describes this period as her “years of magical thinking”. The staging of the exhibition in an old newspaper printing press contrasts with the light, shadows and bold, clashing colours of her work. The lack of natural light intensifies the flamboyant tones of the elaborately composed fashion work.

Dior Magazine (2021), and Milk, from the series Lexicon, 2006. Photographs by Viviane Sassen and Stevenson

Viviane Sassen’s immersive video installation at the Kyoto Shimbun B1F print plant. Photograph by Joanna Ruck

The source of and inspiration for Kyotographie can be traced to Lucien Clergue, the founder of Les Rencontres d’Arles, the first international photography festival, which took place in 1969. Arles, where Clergue grew up and lived all his life, was a canvas for his photography work in the 1950s. Shortly after the second world war, many Roma were freed from internment camps and came to Arles, where Clergue forged a close relationship with the community. Gypsy Tempo reveals the daily life of these families – their nomadic lifestyle, the role of religion and how music and dance are used to tell stories.

Draga in Polka-Dot Dress, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, 1957. Photographs by Lucien Clergue

Little Gypsy Girl in the Chapel, Cannet 1958

During this time, Clergue discovered, and then helped propel to fame, the Gypsy guitarist Manitas de Plata and his friend José Reyes. Manitas went on to become a famous musician in the 1960s who, together with Clergue, toured the world, including Japan.

Kyotographie 2024 was launched alongside its sister festival, Kyotophonie , an international music event, with performances by Los Graciosos, a band from Catalonia who play contemporary Gypsy music. Meanwhile, the sounds of De Plata can be heard by viewers of Clergue’s exhibition.

The Magic Circle, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, 1958, by Lucien Clergue.

Kyotographie 2024 runs until 12 May at venues across Kyoto, Japan.

- The Guardian picture essay

- Photography

- Exhibitions

- Asia Pacific

Most viewed

- Center Reports

- Advisory Board

- Executive Committee

- Faculty & Fellows

- Graduate Students

- Postdoctoral Researchers

- Research Associates

- Visiting Scholars & Students

- Alumni Spotlight

- Past Graduate Students

- Past Postdoctoral Researchers

- Past Visiting Scholars & Students

- Algorithms in Culture

- Art+Science in Residence Program

- Workshop: Advancing Science for Policy Through Interdisciplinary Research in Regulation (ASPIRR)

- Berkeley Papers in History of Science

- Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences

- Quantum Physics Collections and Databases

- The Cloud and the Crowd

- Nuclear Engineering & Society

- Nuclear Futures

- Epistemic Jurisdiction in Biofuels and Geoengineering

- PhD Graduate Field in History of Science

- PhD Designated Emphasis in STS

- Undergraduate Minor in STS

- Undergraduate Course Thread

- Current Events

- Conferences & Workshops

Other Events of Interest

- Past Brownbags

- Past Colloquia

- Past Conferences & Workshops

- Become a part of the Center

- Apply to become a Visiting Scholar or Student

- Past Working Groups

- Rent 470 Stephens

HSNS 54.1: A Special Issue of Essays: Pedagogy in the History of Science and Medicine

April 22nd, 2024 | Published in Latest news

The HSNS February 2024 Issue marks the first for a new “Essays and Reviews” editorial team: Melinda Baldwin and Brigid Vance.

From the Editorial Team:

Henry Cowles and Chitra Ramalingam have left us big shoes to fill, and we want to express our appreciation for everything they have done for both HSNS and us during this editorial transition.

The February 2024 special section focuses on the theme of “Pedagogy in the History of Science.” Like most of our colleagues, the two of us found ourselves navigating a new teaching environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our classes moved online; many students fell ill and needed extra support; faculty and students alike had to find ways to cope with and work through the anxiety, stress, and loneliness of social distancing. In this new environment, we reconsidered learning goals for our students, revised policies on absences and late work, and examined how our field could speak to this moment in history.

That experience led us to solicit essays on pedagogy in the history of science and medicine. Classes at most universities have now resumed in person, but we have heard from many colleagues whose pandemic experiences shifted what and how they teach. The essays in this special section reflect caring, innovative, and rigorous pedagogical approaches that teach not just historical content, but analytical thinking, key academic skills, and new approaches to collaborative and individual work.

The authors of our essays work in a variety of educational contexts, not all of which are university settings. Matthew Shindell and Samantha Thompson of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum share reflections on pedagogy in a museum environment, and Shireen Hamza’s essay recounts her experience teaching at Statesville Prison in Crest Hill, Illinois. Nor are all of the essays about teaching in North America. John DiMoia writes about his experience building a history of computing syllabus for a large course at Seoul National University, and Jongsik Yi shares her work building an innovative syllabus on the history of science in Korea. Many of the essays address efforts to decolonize the way we teach our field, or ways to put the history of science into conversation with other fields. Honghong Tinn’s course on “Ethics and Science and Technology” pushes students to consider case studies of indigenous technology, invisible labor, and exploitation in the East Asian context, and David Dunning and Judith Kaplan share their experience contributing to an interdisciplinary team-taught freshman program.

For the complete text, please read “Introduction: Pedagogy in the History of Science and Medicine” by Melinda Baldwin and Brigid Vance.

Share this:

- See All Events

International Careers Panel: Professionals Across Sectors Share Their Stories

DISCO Summit 2024

06/14/2024 - 06/15/2024

Fordham Library News

The latest from the Fordham University Libraries

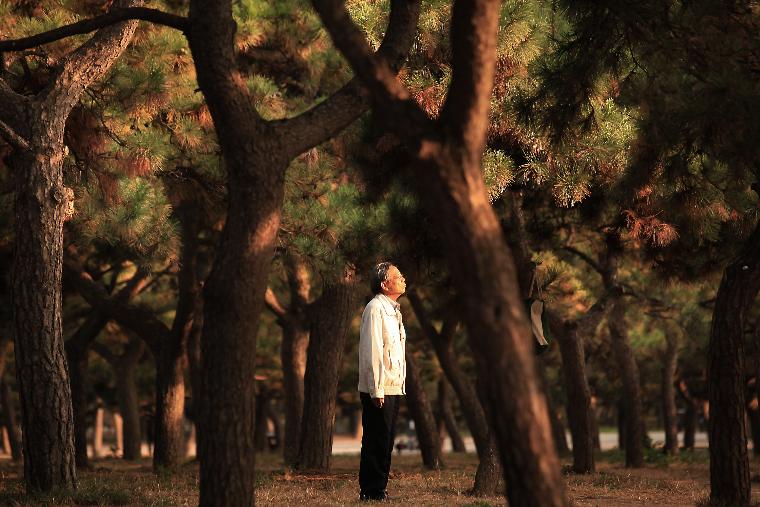

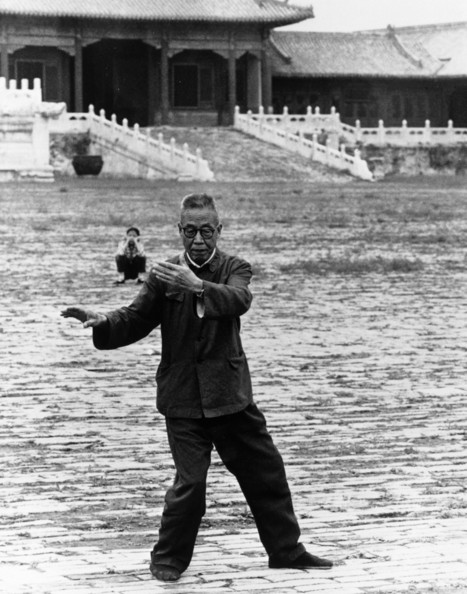

World Tai Chi & QiGong Day

By mike magilligan, reference librarian, lincoln center.

On the last Saturday of April in parks and cities all around the globe an annual celebration of Tai Chi and QiGong takes place. Practitioners gather in groups or solo to perform and celebrate these ancient traditional exercises that blend Martial Arts with Medicinal and Spiritual lineages. The free flowing movements aimed at helping circulate internal energy can be focused with an emphasis on Martial Art/Self defense applications ( Tai Chi ) or on meditative and medicinal benefits ( QiGong ). That is not to say that Tai Chi cannot be medicinal or meditative and a more descriptive analogy would be to think of them as two sides of the same coin. These traditions date back thousands of years and are deeply imbued with the Daoist philosophy of Yin and Yang theory which allows practitioners a deeper meaning to the movements they perform and a day once a year when they get to celebrate!

For a deeper dive on this subject and to celebrate World Tai Chi & QiGong Day here’s some highlights from our Ebooks collection that will allow a better understanding of this subject.

Traditional Chinese Exercises by Jianmei Qu is broken into two parts and gives a comprehensive overview of both Tai/Chi and Qi Gong. Part one focuses on the origins of Qi Gong and gives an informative overview of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), its relation to QiGong and how to maximize the correlation between the two. The second part focuses on teaching the traditional Yang 24 , which is one of the most popular sets of movements (form) in all of Tai Chi and a must know foundation piece.

Don’t let this title fool you as this book for seated QiGong and Tai Chi will have challenging and beneficial moves no matter your experience level. This book also gives a good overview of TCM before it goes into the seated QiGong set and then seated Tai Chi movements that come from the Yang form. A great feature of this book is a section on useful acupressure points and how to use them in treatment of ailments from the physical to mental.

More academic in scope, Lost Tʻai-Chi Classics from the Late Chʻing Dynasty by Douglas Wile looks at the origins of Tai Chi and explores its evolution into different regional styles and the Masters who passed this tradition on to their disciples in an oral tradition. This book analyzes the classic historical texts and discusses the stylistic differences that delineate the major schools from one another while providing basic form applications.

Weapon training is a big part of the Tai Chi tradition and the sword (Jian) is considered the gold standard within this art form. This book gives an historical overview of the sword tradition with an illustrated teaching guide to the basic rudiments and the complete 32 movement Yang Sword Form. This is the most popular sword form and the benchmark form used in international competitions. With handy diagrams for foot placement and detailed instructions this book is a valuable resource for all interested in this field.

World Tai Chi & QiGong Day is this Saturday, April 27th. Consider taking a break from your Saturday studies, head to the park, and get in on the action of this exciting event .

For questions relating to World Tai Chi & QiGong Day, Fordham Libraries, and everything in between, hop on our 24/7 chat service, Ask a Librarian .

More From the Blog

Classics Reimagined

In Her Own Words: Memoirs, Essays, and Autobiographies Celebrating Women’s History Month

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The recent approaches to the study of early medieval Indian history

The recent approaches to the study of early medieval Indian history and how it challenged the hypothesis of Indian Feudalism. This essay will be looking at the different approaches to the study of early medieval Indian history from the 1950s to the latest by looking at the ideas and concepts put forward by historians like D.D. Kosambi, R. S. Sharma, B. N. S. Yadava, D.C. Sircar, Harbans Mukhia, D.N. Jha, Burton Stein, B.D. Chattopadhyaya, and Irfan Habib and how it changed over time.

Related Papers

Pavan Tiwari

Presently, varied schemes of periodization of history are prevalent in historical studies, the most common being the tripartite scheme of ancient-medieval-modern periods. In European history, ancient, medieval and modern eras have remained the dominant standard epochal frontiers since the eighteenth century. In the wake of colonial rule, this scheme was applied by the European historians and orientalists to the colonized regions in Africa and Asia, including India, for historiographical purposes. The concept of medieval period in Indian history is not without problems and limitations. First, not only there are conceptual intricacies involved in it, the whole process of periodization has been politicized. Moreover, the chronological frontiers of medieval India have become conceptual barriers, which restrict historical imagination. Secondly, the medieval period in Indian history, as in European history, is often referred to as the 'Middle Ages'. It is understood as a post-classical age denoting a radical shift from ancient or classical period. Moreover, there seems to be an inherent bias in it, as it implies decline and degeneration in medieval times as opposed to the splendor and glory of the ancient era. Thirdly, despite its common usage, there is no consensus among historians as to what constitute medieval India, though the construction of ancient and modern India is also controversial. As for the ancient India, almost all historians begin it with an account of the prehistoric times followed by the Aryan invasion and the Vedic age, but the problem arises where to bring ancient India to a close and

The Book Review

isara solutions

International Research Journal Commerce arts science

The feudalism debate once play a major role in any medieval researchers, but now it's long gone, still then it relevant for any medieval scholars to understand, as it is the essence of every aspect as it related to urbanisation, trade, land grant and so on. The notion of an 'Indian feudalism' has predominated in the recent historiography of pre-colonial India. Early medieval India has been described by historian, largely as a dark phase of Indian history characterised only by political fragmentation and culture. Such a characterisation being assigned to it, this period remained by and large a neglected one in terms of historical research. We owe it completely in new research in the recent decades to have brought to light the many important and interesting aspects of this period. Fresh studies have contributed to the removal of the notion of 'dark age' attached to this period by offering fresh perspectives. Indeed the every absence of political unity that was considered a negative attribute by earlier scholars in now seen as a factor that had made possible the emergence of rich cultures of the medieval period.

Harbans Mukhia

Inaugural Lecture in the Jadu Nath Sarkar Memorial Lectures Series instituted by the Bangiya Itihas Samiti (Bengali History Society). Traces the evolving contours of medieval Indian history over the past six odd decades.

Bhupesh Singh Danu

An abstract to medieval indian history....

TULIIP BISWAS

THIS IS MY ARTICLE CUM ASSIGNMENT ON THE DEBATE OF EARLY MEDIEVAL INDIAN FEUDALISM.

Tanvir Anjum

Audrey Truschke