Advertisement

- Previous Issue

- Previous Article

- Next Article

The Peer Review Imperative

Threats to peer review, public trust in science and medicine, peer review matters: research quality and the public trust.

Michael M. Todd, M.D., served as Handling Editor for this article.

This article has a related Infographic on p. 17A.

Accepted for publication October 13, 2020.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

- Search Site

Evan D. Kharasch , Michael J. Avram , J. David Clark , Andrew J. Davidson , Timothy T. Houle , Jerrold H. Levy , Martin J. London , Daniel I. Sessler , Laszlo Vutskits; Peer Review Matters: Research Quality and the Public Trust. Anesthesiology 2021; 134:1–6 doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003608

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

“Peer review grounds the public trust in the scientific and medical research enterprise…”

Image: Adobe Stock.

In an era of evidence-based medicine, peer review is an engine and protector of that evidence. Such evidence, vetted by and surviving the peer review process, serves to inform clinical decision-making, providing practitioners with the information to make diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. Unfortunately, there is recent and growing pressure to prioritize the speed of research dissemination, often at the expense of careful peer review. It is timely to remind readers and the public of the value brought by peer review, its benefits to patients, how much the public trust in science and medicine rests upon peer review, and how these have become vulnerable.

Peer review has been the foundation of scholarly publishing and scientific communication since the 1665 publication of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. The benefits and advantages of peer review in scientific research, and particularly medical research, are manifold and manifest. 1 Journals, editors, and peer reviewers hold serious responsibility as stewards of valid information, with accountability to the scientific community and an obligation to maintain the public trust. Anesthesiology states its aspiration and its responsibility on the cover of every issue: Trusted Evidence. Quality peer review (more specifically, closed or single-blind peer review, in which the identity of reviewers is confidential) is a foundational tenet of Anesthesiology.

Peer review grounds the public trust in the scientific and medical research enterprise, as well as the substantial public investment in scientific research. Peer review affords patients some degree of comfort in placing their trust in practitioners, knowing that they should be informed by the best possible, vetted evidence.

Quality peer review enriches and safeguards the scientific content, transparency, comprehensibility, and scientific integrity of published articles. It can enhance published research importance, originality, authenticity, scientific validity, adherence to experimental rigor, and correctness of results and interpretations and can identify errors in research execution. Peer review can help authors improve reporting quality, presentation clarity, and transparency, thereby enhancing comprehension and potential use by clinicians and scientists. Careful scrutiny can identify whether research has appropriate ethical principles, regulatory approvals, compliance, and equitable inclusion of both sexes. Peer review should consider the appropriateness of authorship and can detect duplicate publication, fabrication, falsification, plagiarism, and other misconduct.

Peer review should serve as a tempering factor on overenthusiastic authors and overstated conclusions, unwarranted extrapolations, conflation of association with causality, unsupported clinical recommendations, and spin. Spin is a well known, unfortunately common, and often insidious bias in the presentation and interpretation of results that seeks to convince readers that the beneficial effect of an experimental treatment exceeds what has actually been found or that minimizes untoward effects. 2–4

Manuscripts often change substantially between the initial submission and the revised and improved published version. Improvement during the peer review process is not apparent to readers, who only see the final, published article, but is well known to authors, reviewers, and editors. Peer review is a defining difference in an era of proliferating predatory journals and other forms of research dissemination. Anesthesiology reviewers and editors devote considerable effort in service to helping authors improve their scientific communications, whether published in this journal or if ultimately elsewhere.

In the domain of clinical research, peer review does not change the scientific premise of an investigation, the hypothesis, or the study design, although it frequently improves their communication. Peer review does not change clinical research data, although it often corrects, enhances, or strengthens the statistical analysis of those data and can markedly improve their presentation and clarity. More importantly, peer review can assess, correct, and improve the interpretation, meaning, importance, and communication of research results—and importantly, confirm that conclusions emanate strictly from those results. Peer review may occasionally fundamentally revise or even reverse clinical research interpretations and recommendations. Each of these many functions enhances reader understanding and should ultimately improve patient care.

Peer review is not a guarantee of truth, and it can be imperfect. Medical history provides many examples of peer-reviewed research that was later found to be incorrect, typically through error or occasionally from misconduct. However, peer review certainly was and remains an essential initial check and quality control that has weeded out, or corrected before publication, innumerable reports of research of insufficient quality or veracity that otherwise would have been published and thereby become publicly accessible. Additionally, science should be “self-correcting,” and peer review is one of the most important factors responsible for such correction. Peer review remains an element by which medical science achieves the “self-correction” that drives progress.

Quality peer review does take time. So also do the initial preparation of manuscripts and the modifications made by authors in response to peer review. Anesthesiology endeavors to provide both quality and timely peer review. Our time to first decision averages only 16 days.

The increasing emphasis on fast research dissemination, often absent quality peer review, comes mostly but not exclusively because of the immediacy of the internet and broader media and societal trends. In an era in which the companies whose major product is the immediacy of information are the economic leaders (Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Apple), it is unsurprising that the immediacy of information is challenging that of quality as the value proposition in the research marketplace. Nevertheless, fast is not synonymous with good. We believe that sacrificing quality on the altar of speed is unwise, benefits no one (except perhaps authors), and may ultimately diminish trust in medical research and possibly even worsen clinical care.

Another recent societal problem is the growing spillover of political and media communication trends into scientific communication. Almost half of Americans believe that science researchers overstate the implications of their research, and three in four think “the biggest problem with news about scientific research findings is the way news reporters cover it.” 5 Scientific conclusions may be perverted through internet-based campaigns of disinformation and misinformation and dissemination of misleading and biased information. 6 This threatens the public trust in the scientific enterprise and scientific knowledge. 7 Social media has made science and health vulnerable to strategic manipulation. 7 , 8 It is also “leaving peer-reviewed communication behind as some scientists begin to worry less about their citation index (which takes years to develop) and more about their Twitter response (measurable in hours).” 8 Peer-reviewed journals cannot reverse these trends, but they can at least ensure that scientific conclusions when presented are correct and clearly stated.

In addition to the premium on dissemination speed versus peer review quality, a new variant of rapid clinical research dissemination has emerged that abrogates peer review entirely: preprints. Preprints are research reports that are posted by authors in a publicly accessible online repository in place of or before publication in a peer-reviewed scholarly journal. The preprint concept is decades old, rooted in physics and mathematics, in which authors traditionally sent their hand- or typewritten manuscript draft to a few colleagues for feedback before submitting it to a journal for publication. With the advent of the internet, this process was replaced by preprint servers and public posting. With the creation of a preprint server for biology and the life sciences (bioRxiv.org), the posting of unreviewed manuscripts by basic biomedical scientists has exploded in popularity and practice. Next came the creation of medRxiv.org, a publicly accessible preprint server for disseminating unpublished and unreviewed clinical research results in their “preliminary form” 9 and more so a call for research funders to require mandatory posting of their grantees’ research reports first on preprint servers before peer-reviewed publication. 10 Lack of peer review is the hallmark of preprints.

The main arguments offered by proponents of preprints are the free and near-immediate access to research results, claimed acceleration of the progress of research by immediate dissemination without peer review, and the assumption that articles will be improved by feedback from a wider group of readers alongside formal review by a few experts. Specifically claimed advantages of preprints are that they bypass the peer review process that adversely delays the dissemination of research results and “lifesaving cures” and “the months-long turnaround time of the publishing process and share findings with the community more quickly.” 11 In addition it is claimed that preprints address “researchers recently becoming vocally frustrated about the lengthy process of distributing research through the conventional pipelines, numerous laments decrying increasingly impractical demands of journals and reviewers, complicated dynamics at play from both authors and publishers that can affect time to press” and enable “sharing papers online before (or instead of) publication in peer-reviewed journals.” 11

Preprints for clinical research have been justifiably criticized. 2 , 12–15 Most importantly, medical preprints lack safeguards afforded by peer review and increase the possibility of disseminating wrong or incorrectly interpreted results. Related concerns are that preprints are unnecessary for and potentially harmful to scientific progress and a significant threat with potential consequence to patient health and safety. Preprint server proponents “assume that most preprints would subsequently be peer reviewed,” 10 possibly before or after formal publication (if published), thus enabling correction or improvement (before or after publication). However, it is estimated that careful peer review of a manuscript takes 5 to 6 h. 1 , 16 It seems highly unlikely that busy scientists will surf the web in search of preprints on which to spend half a day providing concerted informative peer review.

Preprint enthusiasts claim that peer review after posting will provide scholarly input, facilitate preprint improvement, and enhance research quality. In fact, such peer review has been scant with biologic preprints, and it seems naïve to expect it with medical preprints. In reality, most preprints receive few comments, even fewer formal reviews, and many comments that are “counted” to support the notion that preprints do undergo peer review actually come through social media; a tweet is hardly a substantive review. The idea that comments on servers will replace quality peer review is not happening now and seems unlikely to transpire. Moreover, a survey found that the lack of peer review was an important reason why authors deliberately choose to post via preprint. 17 Additionally, postdissemination peer review takes longer than traditional prepublication peer review, and there remains concern by authors who do value peer review about the quality of the post-preprint peer review process and the quality of posted preprints. 17

Preprint server proponents state “the work in question would be available to interested readers while these processes (peer review) take place, which is more or less what happens in physics today.” 10 The lives of patients are different than the lives of subatomic particles. Preprints deliberately “decouples the dissemination of manuscripts from the much slower process of evaluation and certification.” 10 However, it is exactly that coupling that validates clinical research, benefits patients, improves health, and engenders public trust.

The potential for free and unfettered distribution of raw, unvetted, and potentially incorrect information to be consumed by clinicians and patients cannot be called a medical advance. Use of such information by news outlets and online web services to promote “new” and “latest” research further misinforms the public and patients and is a disservice.

Relegating peer review to the realm of option and afterthought is not in the interest of research quality and integrity or of patients and public health. There is no apparent value in abrogating peer review of clinical research and all its many attendant benefits in ensuring the quality of clinical research available to practitioners and patients. Practitioners and patients have historically not seen the unreviewed manuscript submissions that eventually become revised peer-reviewed publications. Doing so now, given the sizable fraction of clinical research manuscripts that are rejected for publication and the substantial changes in most that are published, by providing the public with unreviewed preprints seems to carry considerable risk.

An additional problem is that the same research report can be posted on several preprint servers or websites or multiple versions may exist on the same preprint site. Various versions may be the same or different, and the final peer-reviewed published article (if it ever exists) may bear little semblance to the various posted versions, which remain freely available. Which version is correct? Availability of various differing reports of the same research risks competing or incorrect information and can only generate confusion. Scientific publishing decades ago banned publication of the same research in multiple journals owing to concerns about data integrity and inappropriate reuse. Restarting this now, via preprints, seems unwise—especially in medicine.

The public cannot and should not be expected to differentiate between posting and peer-reviewed publication. Unfortunately, and worse, even some practitioners do not understand the difference. Posting is often referred to erroneously as publication. Indeed, even the world’s most prestigious scientific journals refer to posting as publication. 18 Such conflation blurs the validity of information. That peer-reviewed publications and preprints both receive digital object identifiers further blurs their distinction and may give the latter more apparent credibility in the eyes of the lay public. The preprint community (servers and scientists) continues to claim simultaneously that preprints are and are not publications, depending on how such claims meet their proclivities. Although the bioRxiv server contains the disclaimer “readers should be aware that articles on bioRxiv have not been finalized by authors, might contain errors, and report information that has not yet been accepted or endorsed in any way by the scientific or medical community” on a web page, 19 it is not on the preprint itself for readers to see (perhaps this disclaimer, and the one below, should appear on the cover page of every preprint and as a footnote on every page). Fortunately, the medRxiv home page ( http://www.medrxiv.org ) states the following disclaimer: “Preprints are preliminary reports of work that have not been certified by peer review. They should not be relied on to guide clinical practice or health-related behavior and should not be reported in news media as established information.” Then why bother?

The popularity of preprints in the basic science world has exploded in the last 5 yr, with the number of documents posted to preprint servers increasing exponentially. 20 While acknowledging the noble reasons given by preprint servers and authors for the dissemination of research by posting, three other apparent reasons are less noble. The first is competition for research funding. Major research funders ( e.g. , the National Institutes of Health) do not allow citation of unpublished manuscripts in grant applications but do allow citation of preprints. 21 , 22 The second is the preoccupation of authors with the speed of availability. There is a growing (and disappointing) trend of authors perceiving a need to claim priority (“we are the first to report…”), grounded perhaps on fear of being “scooped.” The third is the pursuit of academic promotion, which is based largely on the number of peer-reviewed publications listed on a curriculum vitae . We now see faculty listing preprints in the peer-reviewed research publications section of their curriculum vitae. All these drivers (priority, science advancement, reputational reward, and financial return) 7 are investigator centric. They are neither quality-centric nor patient-centric.

Who benefits if clinical research quality is sacrificed at the altar of speed? Certainly, it is not patients, public health, or the public trust in science, medicine, and the research enterprise. Enthusiasm for preprints seems to be emanating mostly from investigators, presumably because of academic or other incentives, 23 including the desire for prominence and further funding. Is this why we do medical research? Should we be investigator- or patient-centric?

Little in the argumentation espoused by proponents of clinical preprints attends to their benefit to patients. Indeed, posted preprints without all the scrutiny and benefits of peer review may lack quality and validity and may report flawed data and conclusions, which may hurt patients. 17 , 23 As stated previously, “clinical studies of poor quality can harm patients who might start or stop therapy in response to faulty data, whereas little short-term harm would be expected from an unreviewed astronomy study.” 12

The importance of peer review in clinical research and the downside of its absence in posted preprints is illuminated by the COVID-19 pandemic. As of this date (October 1, 2020), there are 9,222 unreviewed COVID-19 SARS–CoV-2 preprints posted: 7,257 on medRxiv and 1,965 on bioRxiv. 24 To date, 33 COVID-19 articles have been retracted (0.37%), and 5 others have been temporarily retracted or have expressions of concern. 25 Of the 33 retractions, 11 (33%) were posted on an Rxiv server. The overall retraction rate in the general peer-reviewed literature is 0.04%. 26

Based upon one of the unreviewed COVID-19 medical preprints, 27 the Commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (the government agency entrusted more than any other to protect public health) and the President of the United States announced that convalescent plasma from COVID-19 survivors was “safe and very effective” and had been “proven to reduce mortality by 35%.” 28 Although the Commissioner later, after scientific uproar over that misinformation, “corrected” his comment in a tweet (a back page retraction to a front page headline), 29 the preprint was used to justify a Food and Drug Administration decision to issue an emergency use authorization for convalescent plasma to treat severe COVID-19. Would these errors have been prevented by peer review? We will never know.

Even if priority in clinical (and basic) research is valued, compared to the unquestionable value of quality, clinical preprints have questionable necessity in establishing precedence in contemporary times. Clinical trials registration, which makes fully public the existence of all such research, establishes both who is doing what and when. Some investigators may even publish their entire clinical protocol, to further make their studies known and by whom and when.

For hundreds of years, patent medicines (exotic concoctions of substances, often addicting and sometimes toxic) were claimed to prevent or cure a panoply of illnesses, without any evidence of effectiveness or safety or warning of potential harm. These medical elixirs, the magic potions of snake oil salesmen and charlatans, were heavily advertised and promoted to ailing, sometimes desperate, and thoroughly unsuspecting citizens—all without any oversight, regulation, quality control, or peer review. It was not until the 20th century that medical peer review and the requirement for evidence of effectiveness and safety reigned in the “Wild West” and launched the modern era of medicine, yielding the scientific discovery, progress, and improvement in human health seen today. This era rests on the bedrock of peer review, the quality ideal, and the evidence that constitutes the foundation for evidence-based medicine.

Will clinical preprints become the patent medicines of the new millennium? Do they portend the unrestricted and unregulated spillage of anything claimed as research, by anyone, and absent the quality control afforded by peer review? Like the patent medicines of a bygone era, which were heavily promoted by the newly developed advertising industry, will “posted” clinical research become fodder for the medical advertising industry and media at large, pushing who knows what information and claims on practitioners and a public already deluged with endless promotions and claims with which they cannot keep up or verify? An unsuspecting public is incapable of differentiating between the “posting” of any research observation by anyone with access to a computer and proper scholarly “publication” of peer-reviewed results and conclusions. This is particularly true of vulnerable patients with severe and/or incurable diseases, who may grasp at anything. Moreover, continuous claims of “breakthroughs” and “proven treatments” based on preprints, followed by backpedaling after challenges and outcries, further reduces public confidence in the scientific endeavor as a whole. This can create the perception that clinical science is unreliable and might be a matter of turf wars and politics instead of reliable valid evidence.

Over the past century and throughout the world, legislation has been passed and government agencies have been created to protect the public and maintain their trust in the medicines they take. Few would advocate dismantling the protections against patent medicines. Why now consider dismantling the peer review process in clinical research?

In 2019, the editors of several journals expressed a well articulated principle that they will not accept clinical research manuscripts that had been previously posted to a preprint server. 30 Their rationale was that the benefit of preprint servers in clinical research did not outweigh the potential harm to patients and scientific integrity. Major specific concerns included: “1) Preprints may be perceived by some (and used by less scrupulous investigators) as evidence even though the studies have not gone through peer review and the public may not be able to discern an unreviewed preprint from a seminal article in a leading journal; 2) It seems unlikely that the kind of prepublication dialogue that has taken place in other academic disciplines (e.g. mathematics and physics) will take place in medicine or surgery because the incentives are very different; 3) Preprints may lead to multiple competing, and perhaps even conflicting, versions of the ‘same’ content being available online at the same time, which can cause (at least) confusion and (at most) grave harm; and 4) For the vast majority of medical diagnoses, a few months of review of a study’s findings do not make a difference; the pace of discovery and dissemination generally is adequate.” These editors’ concerns and approach merit consideration if not more widespread adoption.

The potential for practitioner and public confusion regarding the difference between unregulated preprints and peer-reviewed publication is substantial. Indeed, the posting of preprints is often incorrectly termed “publication.” Peer-reviewed publications versus posted “publications” will soon become a difference without a distinction. Moreover, authors cannot have it both ways. They cannot claim a preprint as a publication for purposes of a grant (and now in some universities potentially for purposes of a degree, appointment, and/or promotion), yet claim it is not a publication for the purposes of submission to a peer-reviewed journal that does not allow prior publication. More importantly, the peer review imperative in clinical research and the role it plays in research quality, the evidence base, and patient care, constitutes an obligation to patient safety that cannot and should not be abrogated.

Peer review, clinical research quality, and the public trust in clinical research all now face an unprecedented assault. Quality peer review is a foundational tenet of Anesthesiology and underlies the Trusted Evidence we publish. Quality, timely, and unpressured peer review will continue to be a hallmark of Anesthesiology , in service to readers, patients, and the public trust.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ryan Walther, Managing Editor, and Vicki Tedeschi, Director of Digital Communications, for their valuable insights.

Competing Interests

Dr. Clark has a consulting agreement with Teikoku Pharma USA (San Jose, California). Dr. Levy reports being on Advisory and Steering Committees for Instrumentation Laboratory (Bedford, Massachusetts), Merck & Co. (Kenilworth, New Jersey), and Octapharma (Lachen, Switzerland). Dr. London reports financial relationships with Wolters Kluwer UptoDate (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and Springer (journal honorarium; New York, New York). The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Citing articles via

Most viewed, email alerts, related articles, social media, affiliations.

- ASA Practice Parameters

- Online First

- Author Resource Center

- About the Journal

- Editorial Board

- Rights & Permissions

- Online ISSN 1528-1175

- Print ISSN 0003-3022

- Anesthesiology

- ASA Monitor

- Terms & Conditions Privacy Policy

- Manage Cookie Preferences

- © Copyright 2024 American Society of Anesthesiologists

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Understanding Peer Review in Science

Peer review is an essential element of the scientific publishing process that helps ensure that research articles are evaluated, critiqued, and improved before release into the academic community. Take a look at the significance of peer review in scientific publications, the typical steps of the process, and and how to approach peer review if you are asked to assess a manuscript.

What Is Peer Review?

Peer review is the evaluation of work by peers, who are people with comparable experience and competency. Peers assess each others’ work in educational settings, in professional settings, and in the publishing world. The goal of peer review is improving quality, defining and maintaining standards, and helping people learn from one another.

In the context of scientific publication, peer review helps editors determine which submissions merit publication and improves the quality of manuscripts prior to their final release.

Types of Peer Review for Manuscripts

There are three main types of peer review:

- Single-blind review: The reviewers know the identities of the authors, but the authors do not know the identities of the reviewers.

- Double-blind review: Both the authors and reviewers remain anonymous to each other.

- Open peer review: The identities of both the authors and reviewers are disclosed, promoting transparency and collaboration.

There are advantages and disadvantages of each method. Anonymous reviews reduce bias but reduce collaboration, while open reviews are more transparent, but increase bias.

Key Elements of Peer Review

Proper selection of a peer group improves the outcome of the process:

- Expertise : Reviewers should possess adequate knowledge and experience in the relevant field to provide constructive feedback.

- Objectivity : Reviewers assess the manuscript impartially and without personal bias.

- Confidentiality : The peer review process maintains confidentiality to protect intellectual property and encourage honest feedback.

- Timeliness : Reviewers provide feedback within a reasonable timeframe to ensure timely publication.

Steps of the Peer Review Process

The typical peer review process for scientific publications involves the following steps:

- Submission : Authors submit their manuscript to a journal that aligns with their research topic.

- Editorial assessment : The journal editor examines the manuscript and determines whether or not it is suitable for publication. If it is not, the manuscript is rejected.

- Peer review : If it is suitable, the editor sends the article to peer reviewers who are experts in the relevant field.

- Reviewer feedback : Reviewers provide feedback, critique, and suggestions for improvement.

- Revision and resubmission : Authors address the feedback and make necessary revisions before resubmitting the manuscript.

- Final decision : The editor makes a final decision on whether to accept or reject the manuscript based on the revised version and reviewer comments.

- Publication : If accepted, the manuscript undergoes copyediting and formatting before being published in the journal.

Pros and Cons

While the goal of peer review is improving the quality of published research, the process isn’t without its drawbacks.

- Quality assurance : Peer review helps ensure the quality and reliability of published research.

- Error detection : The process identifies errors and flaws that the authors may have overlooked.

- Credibility : The scientific community generally considers peer-reviewed articles to be more credible.

- Professional development : Reviewers can learn from the work of others and enhance their own knowledge and understanding.

- Time-consuming : The peer review process can be lengthy, delaying the publication of potentially valuable research.

- Bias : Personal biases of reviews impact their evaluation of the manuscript.

- Inconsistency : Different reviewers may provide conflicting feedback, making it challenging for authors to address all concerns.

- Limited effectiveness : Peer review does not always detect significant errors or misconduct.

- Poaching : Some reviewers take an idea from a submission and gain publication before the authors of the original research.

Steps for Conducting Peer Review of an Article

Generally, an editor provides guidance when you are asked to provide peer review of a manuscript. Here are typical steps of the process.

- Accept the right assignment: Accept invitations to review articles that align with your area of expertise to ensure you can provide well-informed feedback.

- Manage your time: Allocate sufficient time to thoroughly read and evaluate the manuscript, while adhering to the journal’s deadline for providing feedback.

- Read the manuscript multiple times: First, read the manuscript for an overall understanding of the research. Then, read it more closely to assess the details, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Evaluate the structure and organization: Check if the manuscript follows the journal’s guidelines and is structured logically, with clear headings, subheadings, and a coherent flow of information.

- Assess the quality of the research: Evaluate the research question, study design, methodology, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Consider whether the methods are appropriate, the results are valid, and the conclusions are supported by the data.

- Examine the originality and relevance: Determine if the research offers new insights, builds on existing knowledge, and is relevant to the field.

- Check for clarity and consistency: Review the manuscript for clarity of writing, consistent terminology, and proper formatting of figures, tables, and references.

- Identify ethical issues: Look for potential ethical concerns, such as plagiarism, data fabrication, or conflicts of interest.

- Provide constructive feedback: Offer specific, actionable, and objective suggestions for improvement, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of the manuscript. Don’t be mean.

- Organize your review: Structure your review with an overview of your evaluation, followed by detailed comments and suggestions organized by section (e.g., introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion).

- Be professional and respectful: Maintain a respectful tone in your feedback, avoiding personal criticism or derogatory language.

- Proofread your review: Before submitting your review, proofread it for typos, grammar, and clarity.

- Couzin-Frankel J (September 2013). “Biomedical publishing. Secretive and subjective, peer review proves resistant to study”. Science . 341 (6152): 1331. doi: 10.1126/science.341.6152.1331

- Lee, Carole J.; Sugimoto, Cassidy R.; Zhang, Guo; Cronin, Blaise (2013). “Bias in peer review”. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 64 (1): 2–17. doi: 10.1002/asi.22784

- Slavov, Nikolai (2015). “Making the most of peer review”. eLife . 4: e12708. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12708

- Spier, Ray (2002). “The history of the peer-review process”. Trends in Biotechnology . 20 (8): 357–8. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)01985-6

- Squazzoni, Flaminio; Brezis, Elise; Marušić, Ana (2017). “Scientometrics of peer review”. Scientometrics . 113 (1): 501–502. doi: 10.1007/s11192-017-2518-4

Related Posts

Peer Review in Scientific Publications: Benefits, Critiques, & A Survival Guide

Affiliations.

- 1 Clinical Biochemistry, Department of Pediatric Laboratory Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto , Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- 2 Clinical Biochemistry, Department of Pediatric Laboratory Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Chair, Communications and Publications Division (CPD), International Federation for Sick Clinical Chemistry (IFCC), Milan, Italy.

- PMID: 27683470

- PMCID: PMC4975196

Peer review has been defined as a process of subjecting an author's scholarly work, research or ideas to the scrutiny of others who are experts in the same field. It functions to encourage authors to meet the accepted high standards of their discipline and to control the dissemination of research data to ensure that unwarranted claims, unacceptable interpretations or personal views are not published without prior expert review. Despite its wide-spread use by most journals, the peer review process has also been widely criticised due to the slowness of the process to publish new findings and due to perceived bias by the editors and/or reviewers. Within the scientific community, peer review has become an essential component of the academic writing process. It helps ensure that papers published in scientific journals answer meaningful research questions and draw accurate conclusions based on professionally executed experimentation. Submission of low quality manuscripts has become increasingly prevalent, and peer review acts as a filter to prevent this work from reaching the scientific community. The major advantage of a peer review process is that peer-reviewed articles provide a trusted form of scientific communication. Since scientific knowledge is cumulative and builds on itself, this trust is particularly important. Despite the positive impacts of peer review, critics argue that the peer review process stifles innovation in experimentation, and acts as a poor screen against plagiarism. Despite its downfalls, there has not yet been a foolproof system developed to take the place of peer review, however, researchers have been looking into electronic means of improving the peer review process. Unfortunately, the recent explosion in online only/electronic journals has led to mass publication of a large number of scientific articles with little or no peer review. This poses significant risk to advances in scientific knowledge and its future potential. The current article summarizes the peer review process, highlights the pros and cons associated with different types of peer review, and describes new methods for improving peer review.

Keywords: journal; manuscript; open access; peer review; publication.

You are using an outdated browser . Please upgrade your browser today !

What Is Peer Review and Why Is It Important?

It’s one of the major cornerstones of the academic process and critical to maintaining rigorous quality standards for research papers. Whichever side of the peer review process you’re on, we want to help you understand the steps involved.

This post is part of a series that provides practical information and resources for authors and editors.

Peer review – the evaluation of academic research by other experts in the same field – has been used by the scientific community as a method of ensuring novelty and quality of research for more than 300 years. It is a testament to the power of peer review that a scientific hypothesis or statement presented to the world is largely ignored by the scholarly community unless it is first published in a peer-reviewed journal.

It is also safe to say that peer review is a critical element of the scholarly publication process and one of the major cornerstones of the academic process. It acts as a filter, ensuring that research is properly verified before being published. And it arguably improves the quality of the research, as the rigorous review by like-minded experts helps to refine or emphasise key points and correct inadvertent errors.

Ideally, this process encourages authors to meet the accepted standards of their discipline and in turn reduces the dissemination of irrelevant findings, unwarranted claims, unacceptable interpretations, and personal views.

If you are a researcher, you will come across peer review many times in your career. But not every part of the process might be clear to you yet. So, let’s have a look together!

Types of Peer Review

Peer review comes in many different forms. With single-blind peer review , the names of the reviewers are hidden from the authors, while double-blind peer review , both reviewers and authors remain anonymous. Then, there is open peer review , a term which offers more than one interpretation nowadays.

Open peer review can simply mean that reviewer and author identities are revealed to each other. It can also mean that a journal makes the reviewers’ reports and author replies of published papers publicly available (anonymized or not). The “open” in open peer review can even be a call for participation, where fellow researchers are invited to proactively comment on a freely accessible pre-print article. The latter two options are not yet widely used, but the Open Science movement, which strives for more transparency in scientific publishing, has been giving them a strong push over the last years.

If you are unsure about what kind of peer review a specific journal conducts, check out its instructions for authors and/or their editorial policy on the journal’s home page.

Why Should I Even Review?

To answer that question, many reviewers would probably reply that it simply is their “academic duty” – a natural part of academia, an important mechanism to monitor the quality of published research in their field. This is of course why the peer-review system was developed in the first place – by academia rather than the publishers – but there are also benefits.

Are you looking for the right place to publish your paper? Find out here whether a De Gruyter journal might be the right fit.

Besides a general interest in the field, reviewing also helps researchers keep up-to-date with the latest developments. They get to know about new research before everyone else does. It might help with their own research and/or stimulate new ideas. On top of that, reviewing builds relationships with prestigious journals and journal editors.

Clearly, reviewing is also crucial for the development of a scientific career, especially in the early stages. Relatively new services like Publons and ORCID Reviewer Recognition can support reviewers in getting credit for their efforts and making their contributions more visible to the wider community.

The Fundamentals of Reviewing

You have received an invitation to review? Before agreeing to do so, there are three pertinent questions you should ask yourself:

- Does the article you are being asked to review match your expertise?

- Do you have time to review the paper?

- Are there any potential conflicts of interest (e.g. of financial or personal nature)?

If you feel like you cannot handle the review for whatever reason, it is okay to decline. If you can think of a colleague who would be well suited for the topic, even better – suggest them to the journal’s editorial office.

But let’s assume that you have accepted the request. Here are some general things to keep in mind:

Please be aware that reviewer reports provide advice for editors to assist them in reaching a decision on a submitted paper. The final decision concerning a manuscript does not lie with you, but ultimately with the editor. It’s your expert guidance that is being sought.

Reviewing also needs to be conducted confidentially . The article you have been asked to review, including supplementary material, must never be disclosed to a third party. In the traditional single- or double-blind peer review process, your own anonymity will also be strictly preserved. Therefore, you should not communicate directly with the authors.

When writing a review, it is important to keep the journal’s guidelines in mind and to work along the building blocks of a manuscript (typically: abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, references, tables, figures).

After initial receipt of the manuscript, you will be asked to supply your feedback within a specified period (usually 2-4 weeks). If at some point you notice that you are running out of time, get in touch with the editorial office as soon as you can and ask whether an extension is possible.

Some More Advice from a Journal Editor

- Be critical and constructive. An editor will find it easier to overturn very critical, unconstructive comments than to overturn favourable comments.

- Justify and specify all criticisms. Make specific references to the text of the paper (use line numbers!) or to published literature. Vague criticisms are unhelpful.

- Don’t repeat information from the paper , for example, the title and authors names, as this information already appears elsewhere in the review form.

- Check the aims and scope. This will help ensure that your comments are in accordance with journal policy and can be found on its home page.

- Give a clear recommendation . Do not put “I will leave the decision to the editor” in your reply, unless you are genuinely unsure of your recommendation.

- Number your comments. This makes it easy for authors to easily refer to them.

- Be careful not to identify yourself. Check, for example, the file name of your report if you submit it as a Word file.

Sticking to these rules will make the author’s life and that of the editors much easier!

Explore new perspectives on peer review in this collection of blog posts published during Peer Review Week 2021

[Title image by AndreyPopov/iStock/Getty Images Plus

David Sleeman

David Sleeman worked as a Senior Journals Manager in the field of Physical Sciences at De Gruyter.

You might also be interested in

Academia & Publishing

The Impact of Transformative Agreements on Scholarly Publishing

Our website is currently unavailable: cyberattacks on cultural heritage institutions, wie steht es um das wissenschaftliche erbe der ddr eine podiumsdiskussion, visit our shop.

De Gruyter publishes over 1,300 new book titles each year and more than 750 journals in the humanities, social sciences, medicine, mathematics, engineering, computer sciences, natural sciences, and law.

Pin It on Pinterest

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

What is peer review.

Peer review is ‘a process where scientists (“peers”) evaluate the quality of other scientists’ work. By doing this, they aim to ensure the work is rigorous, coherent, uses past research and adds to what we already know.’ You can learn more in this explainer from the Social Science Space.

Peer review brings academic research to publication in the following ways:

- Evaluation – Peer review is an effective form of research evaluation to help select the highest quality articles for publication.

- Integrity – Peer review ensures the integrity of the publishing process and the scholarly record. Reviewers are independent of journal publications and the research being conducted.

- Quality – The filtering process and revision advice improve the quality of the final research article as well as offering the author new insights into their research methods and the results that they have compiled. Peer review gives authors access to the opinions of experts in the field who can provide support and insight.

Types of peer review

- Single-anonymized – the name of the reviewer is hidden from the author.

- Double-anonymized – names are hidden from both reviewers and the authors.

- Triple-anonymized – names are hidden from authors, reviewers, and the editor.

- Open peer review comes in many forms . At Sage we offer a form of open peer review on some journals via our Transparent Peer Review program , whereby the reviews are published alongside the article. The names of the reviewers may also be published, depending on the reviewers’ preference.

- Post publication peer review can offer useful interaction and a discussion forum for the research community. This form of peer review is not usual or appropriate in all fields.

To learn more about the different types of peer review, see page 14 of ‘ The Nuts and Bolts of Peer Review ’ from Sense about Science.

Please double check the manuscript submission guidelines of the journal you are reviewing in order to ensure that you understand the method of peer review being used.

- Journal Author Gateway

- Journal Editor Gateway

- Transparent Peer Review

- How to Review Articles

- Using Sage Track

- Peer Review Ethics

- Resources for Reviewers

- Reviewer Rewards

- Ethics & Responsibility

- Sage Editorial Policies

- Publication Ethics Policies

- Sage Chinese Author Gateway 中国作者资源

- Open Resources & Current Initiatives

- Discipline Hubs

What is peer review?

From a publisher’s perspective, peer review functions as a filter for content, directing better quality articles to better quality journals and so creating journal brands.

Running articles through the process of peer review adds value to them. For this reason publishers need to make sure that peer review is robust.

Editor Feedback

"Pointing out the specifics about flaws in the paper’s structure is paramount. Are methods valid, is data clearly presented, and are conclusions supported by data?” (Editor feedback)

“If an editor can read your comments and understand clearly the basis for your recommendation, then you have written a helpful review.” (Editor feedback)

Peer Review at Its Best

What peer review does best is improve the quality of published papers by motivating authors to submit good quality work – and helping to improve that work through the peer review process.

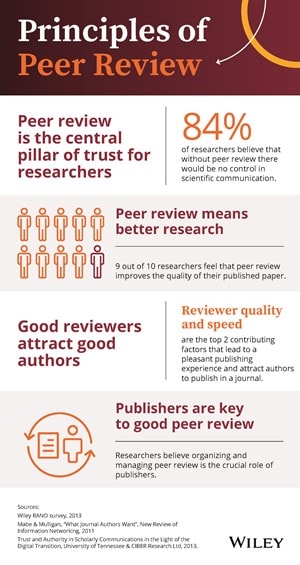

In fact, 90% of researchers feel that peer review improves the quality of their published paper (University of Tennessee and CIBER Research Ltd, 2013).

What the Critics Say

The peer review system is not without criticism. Studies show that even after peer review, some articles still contain inaccuracies and demonstrate that most rejected papers will go on to be published somewhere else.

However, these criticisms should be understood within the context of peer review as a human activity. The occasional errors of peer review are not reasons for abandoning the process altogether – the mistakes would be worse without it.

Improving Effectiveness

Some of the ways in which Wiley is seeking to improve the efficiency of the process, include:

- Reducing the amount of repeat reviewing by innovating around transferable peer review

- Providing training and best practice guidance to peer reviewers

- Improving recognition of the contribution made by reviewers

Visit our Peer Review Process and Types of Peer Review pages for additional detailed information on peer review.

Transparency in Peer Review

Wiley is committed to increasing transparency in peer review, increasing accountability for the peer review process and giving recognition to the work of peer reviewers and editors. We are also actively exploring other peer review models to give researchers the options that suit them and their communities.

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Social Work Research

- Peer Review & Evaluation

- Getting Started

- Encyclopedias & Handbooks

- Evidence Based Practice

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Books & Dissertations

- Data and Statistics

- Film & Video

- Policy & Government Documents

- Trabajo Social

- Citing & Citation Management

- Research Funding

- Open Access

- Choosing & Assessing Journals

- Increasing Access to Your Work

- Tracking Your Impact

- Systematic Reviews

- Tests & Measures

- What is Peer Review?

- How to check peer review

Peer Review is a critical part of evaluating information. It is a process that journals use to ensure the articles they publish represent the best scholarship currently available, and articles from peer reviewed journal are often grounded in empirical research. When an article is submitted to a peer reviewed journal, the editors send it out to other scholars in the same field (the author's peers) to get their assessment of the quality of the scholarship, its relevance to the field, its appropriateness for the journal, etc. Sometimes, you'll see this referred to as "refereed."

Publications that don't use peer review (Time, Cosmo, Salon) rely on an editor to determine the value of an article. Their goal is mainly to educate or entertain the general public, not to support scholarly research.

Most library databases will have a search feature that allows you to limit your results to peer reviewed or scholarly sources.

If you can't tell whether or not a journal is peer-reviewed, check Ulrichsweb.

- Access the database here: Ulrichsweb

- Type in the title of the journal

- Peer-reviewed journals will have a referee jersey ("refereed" is another term for "peer-reviewed") - example below

Evaluation Criteria

Use the criteria below to help you evaluate a source. As you do, remember:

- Each criterion should be considered in the context of your research question . For example, currency changes if you are working on a current event vs. a historical topic.

- Weigh all four criteria when making your decision. For example, the information may appear accurate, but if the authority is suspect you may want to find a more authoritative source for your information.

Criteria to consider:

- Currency : When was the information published or last updated? Is it current enough for your topic?

- Relevance : Is this information that you are looking for? Is it related to your topic? Is it detailed enough to help you answer questions on your topic.

- Use Web of Science database and/or Google Scholar

- Accuracy : Is the information true? What information does the author cite or refer to? Can you find this information anywhere else? Can you find evidence to back it up from another resource? Are studies mentioned but not cited (this would be something to check on)? Can you locate those studies?

- Methodology: What type of study did they conduct? Is it an appropriate type of study to answer their research question? How many people were involved in the study? Is the sample size large and diverse enough to give trustworthy results?

- Purpose/perspective : What is the purpose of the information? Was it written to sell something or to convince you of something? Is this fact or opinion based? Is it unfairly biased?

Learn more about how to evaluate your source

- Evaluate Sources

Source Evaluation Chart

- Source Evaluation Chart If you find it helpful, use this chart to evaluate sources as you read them. This is just a sample of some of the questions you might ask.

- Last Updated: Jan 26, 2024 7:14 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/socialwork

- myState on Mississippi State University

- Directory on Mississippi State University

- Seminar Series

Peer Review and (Dis)Service to Research

Dr. Renee Clary

Peer review serves an essential role in research and its dissemination of results, though the quality of peer review varies greatly. This session will overview the essential variables for superior peer review, including the importance of reviewer confidentiality and security, to help you avoid being THAT Reviewer.

- Find Office of Research and Economic Development on Facebook

- Find Office of Research and Economic Development on X Twitter

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NATURE INDEX

- 01 May 2024

Plagiarism in peer-review reports could be the ‘tip of the iceberg’

- Jackson Ryan 0

Jackson Ryan is a freelance science journalist in Sydney, Australia.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Time pressures and a lack of confidence could be prompting reviewers to plagiarize text in their reports. Credit: Thomas Reimer/Zoonar via Alamy

Mikołaj Piniewski is a researcher to whom PhD students and collaborators turn when they need to revise or refine a manuscript. The hydrologist, at the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, has a keen eye for problems in text — a skill that came in handy last year when he encountered some suspicious writing in peer-review reports of his own paper.

Last May, when Piniewski was reading the peer-review feedback that he and his co-authors had received for a manuscript they’d submitted to an environmental-science journal, alarm bells started ringing in his head. Comments by two of the three reviewers were vague and lacked substance, so Piniewski decided to run a Google search, looking at specific phrases and quotes the reviewers had used.

To his surprise, he found the comments were identical to those that were already available on the Internet, in multiple open-access review reports from publishers such as MDPI and PLOS. “I was speechless,” says Piniewski. The revelation caused him to go back to another manuscript that he had submitted a few months earlier, and dig out the peer-review reports he received for that. He found more plagiarized text. After e-mailing several collaborators, he assembled a team to dig deeper.

Meet this super-spotter of duplicated images in science papers

The team published the results of its investigation in Scientometrics in February 1 , examining dozens of cases of apparent plagiarism in peer-review reports, identifying the use of identical phrases across reports prepared for 19 journals. The team discovered exact quotes duplicated across 50 publications, saying that the findings are just “the tip of the iceberg” when it comes to misconduct in the peer-review system.

Dorothy Bishop, a former neuroscientist at the University of Oxford, UK, who has turned her attention to investigating research misconduct, was “favourably impressed” by the team’s analysis. “I felt the way they approached it was quite useful and might be a guide for other people trying to pin this stuff down,” she says.

Peer review under review

Piniewski and his colleagues conducted three analyses. First, they uploaded five peer-review reports from the two manuscripts that his laboratory had submitted to a rudimentary online plagiarism-detection tool . The reports had 44–100% similarity to previously published online content. Links were provided to the sources in which duplications were found.

The researchers drilled down further. They broke one of the suspicious peer-review reports down to fragments of one to three sentences each and searched for them on Google. In seconds, the search engine returned a number of hits: the exact phrases appeared in 22 open peer-review reports, published between 2021 and 2023.

The final analysis provided the most worrying results. They took a single quote — 43 words long and featuring multiple language errors, including incorrect capitalization — and pasted it into Google. The search revealed that the quote, or variants of it, had been used in 50 peer-review reports.

Predominantly, these reports were from journals published by MDPI, PLOS and Elsevier, and the team found that the amount of duplication increased year-on-year between 2021 and 2023. Whether this is because of an increase in the number of open-access peer-review reports during this time or an indication of a growing problem is unclear — but Piniewski thinks that it could be a little bit of both.

Why would a peer reviewer use plagiarized text in their report? The team says that some might be attempting to save time , whereas others could be motivated by a lack of confidence in their writing ability, for example, if they aren’t fluent in English.

The team notes that there are instances that might not represent misconduct. “A tolerable rephrasing of your own words from a different review? I think that’s fine,” says Piniewski. “But I imagine that most of these cases we found are actually something else.”

The source of the problem

Duplication and manipulation of peer-review reports is not a new phenomenon. “I think it’s now increasingly recognized that the manipulation of the peer-review process, which was recognized around 2010, was probably an indication of paper mills operating at that point,” says Jennifer Byrne, director of biobanking at New South Wales Health in Sydney, Australia, who also studies research integrity in scientific literature.

Paper mills — organizations that churn out fake research papers and sell authorships to turn a profit — have been known to tamper with reviews to push manuscripts through to publication, says Byrne.

The fight against fake-paper factories that churn out sham science

However, when Bishop looked at Piniewski’s case, she could not find any overt evidence of paper-mill activity. Rather, she suspects that journal editors might be involved in cases of peer-review-report duplication and suggests studying the track records of those who’ve allowed inadequate or plagiarized reports to proliferate.

Piniewski’s team is also concerned about the rise of duplications as generative artificial intelligence (AI) becomes easier to access . Although his team didn’t look for signs of AI use, its ability to quickly ingest and rephrase large swathes of text is seen as an emerging issue.

A preprint posted in March 2 showed evidence of researchers using AI chatbots to assist with peer review, identifying specific adjectives that could be hallmarks of AI-written text in peer-review reports .

Bishop isn’t as concerned as Piniewski about AI-generated reports, saying that it’s easy to distinguish between AI-generated text and legitimate reviewer commentary. “The beautiful thing about peer review,” she says, is that it is “one thing you couldn’t do a credible job with AI”.

Preventing plagiarism

Publishers seem to be taking action. Bethany Baker, a media-relations manager at PLOS, who is based in Cambridge, UK, told Nature Index that the PLOS Publication Ethics team “is investigating the concerns raised in the Scientometrics article about potential plagiarism in peer reviews”.

How big is science’s fake-paper problem?

An Elsevier representative told Nature Index that the publisher “can confirm that this matter has been brought to our attention and we are conducting an investigation”.

In a statement, the MDPI Research Integrity and Publication Ethics Team said that it has been made aware of potential misconduct by reviewers in its journals and is “actively addressing and investigating this issue”. It did not confirm whether this was related to the Scientometrics article.

One proposed solution to the problem is ensuring that all submitted reviews are checked using plagiarism-detection software. In 2022, exploratory work by Adam Day, a data scientist at Sage Publications, based in Thousand Oaks, California, identified duplicated text in peer-review reports that might be suggestive of paper-mill activity. Day offered a similar solution of using anti-plagiarism software , such as Turnitin.

Piniewski expects the problem to get worse in the coming years, but he hasn’t received any unusual peer-review reports since those that originally sparked his research. Still, he says that he’s now even more vigilant. “If something unusual occurs, I will spot it.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01312-0

Piniewski, M., Jarić, I., Koutsoyiannis, D. & Kundzewicz, Z. W. Scientometrics https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-04960-1 (2024).

Article Google Scholar

Liang, W. et al. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.07183 (2024).

Download references

Related Articles

- Peer review

- Research management

Algorithm ranks peer reviewers by reputation — but critics warn of bias

Nature Index 25 APR 24

Researchers want a ‘nutrition label’ for academic-paper facts

Nature Index 17 APR 24

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

Editorial 09 APR 24

Structure peer review to make it more robust

World View 16 APR 24

Is ChatGPT corrupting peer review? Telltale words hint at AI use

News 10 APR 24

How reliable is this research? Tool flags papers discussed on PubPeer

News 29 APR 24

Scientists urged to collect royalties from the ‘magic money tree’

Career Feature 25 APR 24

Silver Endowed Chair (Developmental Psychiatry)(Open Rank Faculty)

The Robert A. Silver Endowed Chair in Developmental Neurobiology leads an internationally recognized, competitively funded research program...

Tampa, Florida

University of South Florida - Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Neurosciences

W2 Professorship with tenure track to W3 in Animal Husbandry (f/m/d)

The Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Göttingen invites applications for a temporary professorship with civil servant status (g...

Göttingen (Stadt), Niedersachsen (DE)

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

Postdoctoral Associate- Cardiovascular Research

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Faculty Positions & Postdocs at Institute of Physics (IOP), Chinese Academy of Sciences

IOP is the leading research institute in China in condensed matter physics and related fields. Through the steadfast efforts of generations of scie...

Beijing, China

Institute of Physics (IOP), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS)

Director, NLM

Vacancy Announcement Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health DIRECTOR, NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE THE POSITION:...

Bethesda, Maryland

National Library of Medicine - Office of the Director

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 29 April 2024

Self-reported health related quality of life in children and adolescents with an eating disorder

- A. Wever ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8877-5876 1 ,

- E. van Gerner 2 ,

- J.C.M Jansen 3 &

- B. Levelink 1

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 242 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

100 Accesses

Metrics details

Eating disorders in children and adolescents can have serious medical and psychological consequences. The objective of this retrospective quantitative study is to gain insight in self-reported Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) of children and adolescents with a DSM-5 diagnosis of an eating disorder.

Collect and analyse data of patients aged 8–18 years, receiving treatment for an eating disorder. At the start and end of treatment patients completed the KIDSCREEN-52, a questionnaire measuring HRQoL.

Data of 140 patients were analysed. Children diagnosed with Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder all had lower HRQoL on multiple dimensions at the start of treatment, there is no statistically significant difference between these groups. In contrast, patients with Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder only had lower HRQoL for the dimension Physical Well-Being. HRQoL showed a significant improvement in many dimensions between start and end of treatment, but did not normalize compared to normative reference values of Dutch children.

The current study showed that self-reported HRQoL is low in children with eating disorders, both at the beginning but also at the end of treatment. This confirms the importance of continuing to invest in the various HRQoL domains.

Peer Review reports

Eating disorders in children and adolescents can have serious medical and psychological consequences and rank 12th on the list of physical and mental conditions amongst woman aged 15–19 years in high-income countries when looking at the global burden of disease [ 1 , 2 ]. The estimated lifetime prevalence of Anorexia Nervosa (AN) in woman is 1–4% and 1–2% for Bulimia Nervosa (BN), and the epidemiology is changing, with increasing rates of eating disorders in younger children, boys and minority groups [ 2 , 3 ].

The past two decades research on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with an eating disorder has increased [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. HRQoL is a subjective evaluation of the overall health of an individual, as well as the health of underlying subdimensions of physical, psychological and social functioning [ 9 ]. Most studies have been conducted in adults and a recent review and meta-analysis both show that eating disorders are associated with significant impaired HRQoL compared with the healthy population [ 10 , 11 ]. To our knowledge only one other study evaluated the impact of eating disorders on HRQoL in children and adolescents. Jenkins et al. looked at the impact of eating disorders in a group of adolescents seeking treatment for AN, BN or eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) [ 6 ]. This study reported a poorer HRQoL measured with the SF-36 Health Survey in adolescents with an eating disorder compared with adolescent norms for the Swedish population [ 6 ]. Two studies included both children and adolescents. Weigel et al. examined the association between disorder specific factors, comorbidity and HRQoL in anorexia nervosa in adolescents and adults. HRQoL was measured using the visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) a generic scale that does not look to different HRQoL domains [ 12 ]. Ackard et al. assessed quality of life in patients diagnosed with an eating disorder, mean age at initial assessment was 20.6 years (SD 5 8.3 years), with a range of 12–53 years. Children were not assessed separatly. Other studies in children and adolescents focused on disordered eating behaviours, but not diagnosed eating disorders [ 4 ]. A review of population-based studies showed that disordered eating attitudes and behaviours were associated with lower HRQoL in children and adolescents [ 9 ]. Herpertz-Dahlmann and colleagues found a poorer HRQoL in adolescents with self-reported disordered eating, and an association between eating disorder symptoms and psychopathology [ 13 ].

Because treating an eating disorder encompasses more than weight gain alone it is important to know the possible impact of an eating disorder on HRQoL [ 14 ]. As there are still few studies on self-reported HRQoL in children and adolescents with a diagnosed eating disorder, the primary aim of this study is to gain more insight in the different domains of self-reported HRQoL in a clinical sample of children and adolescents with a DSM-5 diagnosis of an eating disorder at the beginning of treatment. In addition, changes of HRQoL between start and end of treatment were evaluated to determine whether treatment influences HRQoL and if so which domains.

Participant

Data of patients who were diagnosed conform the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) -IV-TR/DSM-5 criteria for an eating disorder, and receiving treatment between November 2006 and April 2019 at The Mutsaersstichting were used [ 15 , 16 ]. The Mutsaersstichting is a mental healthcare institute specialised in eating disorders in the Netherlands where children between 0 and 18 years receive both in- and outpatient treatment. At first presentation, every patient received an extensive consultation with a child and youth psychologist, a child and youth psychiatrist and a paediatrician. Based on this information DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 classification were made. Patients diagnosed before 2014 were rediagnosed using the DSM-5 classification, especially using the new criteria for Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID). Subsequently, a personalized treatment plan was presented to the family. Treatment always consisted of a combination of family-based treatment, individual treatment, group treatment and physical follow-up. Data from patients who met the DSM-5 diagnosis for AN, BN, ARFID, Binge Eating Disorder (BED), or OSFED were considered eligible for analyses. Because the study specifically focused on self-reported HRQoL, only data of children between the ages of 8 and 18 were included, since for younger children the parents completed the HRQoL questionnaire. Children and adolescents who only had HRQoL reports completed by the parents were excluded. Ethical approval was obtained from the medical ethics committee of the Maastricht University Medical Centre.

As part of the Routine Outcome Monitoring the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire was sent to every patient who sought treatment for an eating disorder at the Mutsaersstichting. Baseline characteristics and clinical data were collected at the start and end of treatment. At first consultation, patient characteristics including age, sex, underlying diseases, eating attitudes and behaviours, compensatory behaviour and sociodemographic data were obtained. Heart rate and blood pressure were measured with an oscillometric blood pressure machine and evaluated according to the Clinical Practice Guidline of the American Acadamy of Pediatrics [ 17 ]. In addition, a full physical examination was performed. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated from measured weight and height [ 18 ]. Growth charts designed by the Dutch organization for applied scientific research (TNO) were used to determine height for age (standard deviation, SD) and weight for height (SD) [ 19 , 20 ]. At the end-evaluation data was collected concerning most recent height, weight, BMI and eating attitudes and behaviours.

The KIDSCREEN-52 is a validated self-report questionnaire for measuring HRQoL in European children between 8 and 18 years old [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. It consists of 52 questions, divided into 10 dimensions: Physical Well-being, Psychological Well-being, Moods and Emotions, Self-Perception, Autonomy, Parent Relations and Home Life, Social Support and Peers, School Environment, Social Acceptance (Bullying), and Financial Resources. The KIDSCREEN-52 uses 5-point Likert scale responses, within each different dimension the results are converted into a Rasch scale. Cronbach–alpha’s vary between 0.77 and 0.89 [ 25 ]. The results are transformed to a t-score, giving the children in the total reference population a mean t-score of 50 with a SD of 10. Specific reference populations are made by country, gender and age groups. The results of this study are compared with the validated normative reference values of Dutch children in the age between 8 and 18 years old [ 25 ]. Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer defined a mean t-score 0.5 SD below the mean t-score of the specific referential population of a country as a low HRQoL and a t-score 0.5 SD above the mean t-score of the referential population as high HRQoL [ 25 ].

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 [ 26 ]. The Mann-Withney U, χ 2 , and fisher exact test were used to determine whether there were statistical differences between all the children and adolescents included in this study and the children who completed the questionnaire at intake and end-evaluation. Paired t test was used to test for statistically significant differences in HRQoL between start- and end of treatment. To test the differences in t-score on the KIDSCREEN-52 stratified for DSM-classification, a one-way ANOVA and Welch test was done, with the Tukey’s Test as a post-hoc analysis. Statistically significance was considered when the result had a p value of < 0.05. Univariate regression analysis was done in the group diagnosed with AN to test whether there is an association between HRQoL and BMI, BMI SD, age, excessive exercise and binge eating. Since purging only occurred in four patients this could not be included in the analysis. Other DSM-5 diagnoses where not included due to small subgroup sample size.

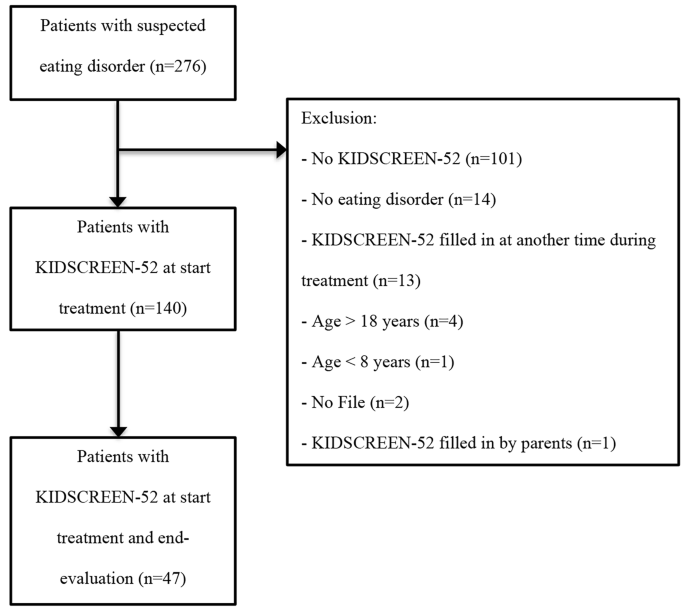

Baseline characteristics

Data of 276 patients were analysed of which 140 were found eligible for this study (Fig. 1 ). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 . The total population consisted primarily of female children and adolescents ( n = 119; 85%) with a mean age of 15.0 years ranging from 8 to 18 years. Almost half of the population was classified as AN ( n = 68; 48.6%). The mean weight for children with AN ( n = 67) was 44.1 kg (minimal weight 25 kg– maximal weight 59 kg) with a mean weight SD of -1.6 and mean BMI of 15.9 kg/m 2 (minimal BMI 11.9 kg/m 2 – maximal BMI 19.9 kg/m 2 ). Children with ARFID had a mean weight of 31.9 kg (minimal weight 18 kg– maximal weight 105 kg), mean weight SD– 0.6, mean BMI 15.9 kg/m 2 (minimal BMI 12.1 kg/m 2 – maximal BMI 36.3 kg/m 2 ). Only two patients were diagnosed with BED, this was too small a sample size to be included in results stratified for the DSM-5 criteria. No significant differences were found in the baseline characteristics between children who completed the KIDSCREEN-52 only at the beginning of treatment, and those who completed the questionnaire both at the start and end-evaluation ( n = 47), except for psychiatric co-morbidities ( X 2 (1) = 4.97; p = 0.026). Even though the effect size for this finding, Cramer’s V = 0.188, was weak, due to the known association between psychiatric co-morbidities and eating disorder symptoms, a comparison between HRQoL at the beginning and end of treatment was only made within the group of 47 patients that completed both questionnaires [ 13 , 27 , 28 ].

HRQoL at the start of treatment