Promoting Oral Presentation Skills Through Drama-Based Tasks with an Authentic Audience: A Longitudinal Study

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 15 March 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 253–267, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Yow-jyy Joyce Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7786-446X 1 &

- Yeu-Ting Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8055-0587 2

10k Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

Drama activities are reported to foster language learning, and may prepare learners for oral skills that mirror those used in real life. This year-long time series classroom-based quasi-experimental study followed a between-subjects design in which two classes of college EFL learners were exposed to two oral training conditions: (1) an experimental one in which drama-based training pedagogy was employed; and (2) the comparison one in which ordinary public speaking pedagogy was utilized. The experimental participants dramatized a picture book into a play, refined and rehearsed it for the classroom audience, and eventually performed it publicly as a theater production for community children. Diachronic comparisons of the participants’ oral presentation skills under the two conditions showed that a significant between-group difference began to become pronounced only after the experimental participants started to present for real-life audiences other than their classmates. This finding suggests that drama-mediated pedagogy effectively enhanced the experimental participants’ presentation performance and became more effective than the traditional approach only after a real-life audience was involved. In addition to the participants’ performance data, survey and retrospective protocols were utilized to shed light on how drama-based tasks targeting both classroom and authentic audiences influence college EFL learners’ presentation performance and their self-perceived oral presentation skills. Analysis of the survey and retrospective data indicated that the participants’ attention to three presentation skills—structure, audience adaptation and content—was significantly raised after their presentation involved a real-life audience. Based on these findings, pedagogical implications for drama for FL oral presentation instruction are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Pretexts: Igniter Materials of Dramatic Elsewhere in EFL Classrooms

What’s the Story with Storytime?: An Examination of Preschool Teachers’ Drama-Based and Shared Reading Practices During Picturebook Read-Aloud

Annette C. Schmidt, Melissa Pierce-Rivera, … M. Adelaida Restrepo

Drama As a Learning Medium in Science Education

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study explores drama-based activities as a vehicle for real-world situations to train foreign language (FL) oral presentation skills in tertiary education. One of the most effective ways of learning a target language is to apply it in a real-life context. It has been repeatedly proven that students acquire a foreign language best when they have a real purpose for learning, and when their use of language is meaningful and authentic (Chamot, 2009 ; Enright et al., 1988 ; Long, 2015 ). In the case of oral performance, however, while practicing their oral skills, FL learners in the classroom tend to target their presentation assignment on their peers and the teacher, and the presentations generated under such circumstances are often shaped by a restricted array of purposes and audience, and confined to the classroom-based activities and cohort. This issue speaks to the need to design effective authentic tasks that can better prepare FL learners for real-world oral communication.

So, how do language instructors and scholars perceive the concept of authenticity? According to Celce-Murcia ( 2008 ), communicative value is a telling sign of authenticity. Authenticity in the language education literature is often discussed in terms of three aspects: authenticity in language, task and situation (Beatty, 2015 ; Breen, 1985 ). Unfortunately, due to the demands of test-driven curricula, authenticity is often not inherent in the language pedagogy in many second language (L2) and FL classrooms (Widdowson, 1990 ). In line with this trend, many teaching and practice tasks in the classroom focus mainly on pedagogical or remedial activities that aim to prepare students for tests rather than on tasks that genuinely engage students with real-world language, tasks and situations that are rich in communicative characteristics, such as purposefulness, reciprocity, synchronicity, and unpredictability (Beatty, 2015 ; Thornbury, 2010 ; see also Widdowson, 1990 ). Consequently, in many FL classrooms, authenticity in language, task, and situation becomes a challenge because the pedagogical context of the language classroom makes what goes on inherently inauthentic, and the pedagogy in the language classroom lacks the genuine communicative value found in the real-world context (Beatty, 2015 ). The benefit of using drama and theater production with a real-life audience is mainly investigated and established in the domain of writing; studies have shown that the inclusion of an online audience prompted foreign and second language learners to develop an enhanced audience awareness (Hung, 2011 ; Warschauer, 1999 ), improve their writing outputs (Pilkington et al., 2000 ), and become more confident in their writing abilities (Choi, 2008 ; Phinney, 1991 ).

Despite the positive evidence from these studies, whether similar benefits also hold true in the domain of public oral presentation skills—a deliberate act of presenting a topic to a live audience to influence, educate, communicate, or entertain—is yet to be investigated. Spanning two academic semesters, this longitudinal study set out to explore the diachronic impacts that drama-based tasks may have on college students’ oral presentation outcomes and on their perceptions of their presentation skills.

Literature Review

Using drama/theater as an effective means of promoting oral skills.

Drama provides an authentic arena for real language use in real situations with an emphasis on reciprocal, synchronized, unpredictable audience interactions (Beatty, 2015 ; Thornbury, 2010 ; see also Widdowson, 1990 ). First-language (L1) research has shown that drama has the pedagogical potency to enhance listening comprehension (Thompson & Rubin, 1996 ), reinforce the tie between thought and expression in writing (Dunn et al., 2013 ), offer paralanguage and suprasegmental cues to enhance speaking skills (Di Pietro, 1987 ; Kao & O’Neill, 1998 ; Miccoli, 2003 ; Whiteson, 1996 ), strengthen reading comprehension (Cornett, 2003 ), and even facilitate vocabulary acquisition (Rose, 1987 ). Among these benefits, drama is particularly conducive to the development of various oral skills (Whiteson, 1996 ). To make a strong case for this view, Podlozny ( 2000 ) conducted an extensive meta-analysis of 80 studies published since 1950 which investigated the impact of drama on oral language outcomes. This meta-analysis shows that classroom drama significantly facilitated oral language development.

In the realm of FL and L2 research, Kao et al. ( 2011 ) reported that in the process of building the drama context, FL learners had the chance to critically evaluate and practice their listening and speaking skills; they claimed that drama is a tool with the potential to engage English FL learners and promote their oral proficiency (see also Hwang et al., 2016 ). Recently, Zhang et al. ( 2019 ) found that the interactions among peers in the form of collaboration and discussion during a drama-based learning process significantly promoted young English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) learners’ storytelling skills.

The examples above illustrate that dramatic activities, if well-designed and well-handled, can significantly enhance various oral skills. Note, however, that not all studies have yielded unequivocal, positive evidence supporting this view. According to Lee et al.’s ( 2015 ) meta-analysis of 47 drama-based pedagogy (DBP) research studies, the mixed findings among existing studies may be attributed to the duration of drama-based language teaching/learning. Lee et al. thus posited that a “more positive effect [arising from DBP] will result when students experience [drama-based] interventions that include frequent…sessions that occur over [a] longer period compared [with] sessions [that are] infrequent or the intervention as a whole is brief” (Lee et al., 2015 , pp. 11–12). Specifically, while reviewing relevant works on drama-based language learning, Lee et al. observed that larger effect sizes and stronger effects were typically associated with studies “that span 12 weeks to a year or more” (Lee et al., 2015 , p. 38; see also Conard, 1992 for a similar view). However, many such studies are short-term projects, which usually span from 3 to 6 weeks (e.g., Hwang et al., 2016 ; Kao et al., 2011 ; Zhang et al., 2019 ). The above finding entails that oral presentation skills, which take time to develop, are more likely to be captured in longitudinal studies, and that the effects of drama-based language teaching on oratory or public speaking skills may be more manifest in long-term treatment that lasts at least 12 weeks. Hitherto, there has been a scarcity of longitudinal studies in drama-based language pedagogy (Stinson & Winston, 2011 ).

Furthermore, the relevant studies have focused predominantly on elementary school children (Andresen, 2005 ; Kelner, 2002 ; Mages, 2008 ; McCaslin, 1990 ). More studies that involve older, cognitively mature FL learners (such as teenagers and college students) are needed to gain further insights into the effects of drama-based activities on FL learners’ oral presentation skills. The current research is designed to investigate the longitudinal impacts of drama-based tasks on college EFL learners’ oral presentation skills.

The Importance of Involving a Real-Life Audience Beyond the Classroom Setting

More than 2 decades ago, drama and theater scholars began to stress the importance of involving authentic audiences beyond the classroom walls. For instance, Brook ( 1996 ) claimed that the existence of a live audience in an act of theater may be all that is needed to “see the varying lengths of attention [an actor] could command” (p. 52). Etchells commented that actors and an audience are two irreducible facts of theater (Etchells, 1999 ). However, empirical validation of the above stipulation has only started to accumulate during the past decade, mostly in the realm of L2 writing. L2 writing studies have revealed that the inclusion of (online) audiences outside the classroom walls prompts English as a foreign language (EFL) learners to develop an enhanced audience awareness (Hung, 2011 ; Warschauer, 1999 ), improve their writing outputs (Chen & Brown, 2012 ; Lin et al., 2014 ; Pilkington et al., 2000 ; Wang, 2015 ), enhance their motivation (Chen & Brown, 2012 ; Lin et al., 2016 ) and develop confidence in their writing abilities (Choi, 2008 ; Phinney, 1991 ).

Among the aforementioned studies, Chen and Brown’s ( 2012 ) study is a case in point. In their canonical study, six L2 learners were asked to complete three writing tasks for a specific, authentic audience, using two internet-based applications ( Wikispaces and Weekbly ). Analysis of these learners’ interview data revealed that they were all highly motivated to learn, and had significantly positive perceptions of their progress; notably, they were all driven to improve their sentence precision and complexity, and to enlarge their vocabulary knowledge. Nevertheless, the generalizability of Chen and Brown’s study was constrained due to the small sample size, and a strong case about the imperative role of an authentic audience cannot be made because of the lack of a comparison or control group. The above issues were later addressed by Lin et al. ( 2014 ) in whose study learners were exposed to two writing conditions: (1) the experimental condition: learners wrote daily blogs for an authentic audience; and (2) the comparison condition: learners wrote their journals in their notebooks using pen and paper (without an authentic audience). Diachronic cross-group comparisons indicated that although the two groups did not differ significantly in their attitudes, the experimental participants exhibited a greater improvement over time, and experienced less anxiety. This finding was later replicated in Wang’s ( 2015 ) and Lin et al.’s ( 2016 ) studies which introduced L2 learners to authentic audiences using the University Teacher-Student Blog (TSB) freely offered to them, and Facebook, respectively. Online audiences beyond the classroom setting also exert a positive influence on students’ communicative competence shown in video-based artifacts (Hafner & Miller, 2011 ; Yeh, 2018 ).

Despite the positive evidence supporting the pivotal role of an authentic audience in promoting L2 writing, this issue has not been examined in the context of L2 speaking where learners face qualitatively different challenges (e.g., having time pressure and requiring different parsing strategies) in planning and production. In spite of the absence of empirical evidence in L2 speaking, Casteleyn ( 2019 ) stipulated the pivotal role of involving a real audience in promoting L2 oral skills. According to Casteleyn’s recent study (Casteleyn, 2019 ) on theater performance, drama and theater play can effectively help language learners “live the experience” and promote their oral presentation skills in real life due to the following three features:

Systematic desensitization: Casteleyn believes that regularly conducted activities (i.e., drama/theater training and performance) have the potency to desensitize students’ speaking anxiety by allowing them to constantly explore and experience the target language in various meaningful, realistic contexts (Purcell-Gates et al., 2002 )

Skills training: Casteleyn contends that activities such as drama/theater share numerous elements (voice, face, body language, structure, script content, audience, etc.) that are parallel to the communicative activities in real life. Thus, drama/theater practice and performance can effectively prepare students to develop the oratory skills required for meaningful communicative activities beyond the classroom setting

Cognitive modification: Casteleyn posits that drama and theater productions provide students with opportunities to connect to a real-life audience other than their classmates. Performing drama for an audience beyond the classroom setting is a useful way of fostering students’ incentive to practice/perform, and hence to develop a positive mindset for public speaking and performance beyond the classroom setting

Casteleyn’s ( 2019 ) view regarding systematic desensitization and skills training is familiar to many FL or L2 teachers who employ drama in their classrooms, especially those proponents of task-based language teaching (TBLT) (see Ekiert et al., 2018 ). Note, however, that the third feature proposed by Casteleyn ( 2019 ), namely fostering a positive state of mind throughout the involvement of an audience beyond the classroom, has not been sufficiently validated either in the research on drama/theater or that on language education. Consequently, whether the involvement of an authentic audience is facilitative in promoting L2 speaking and presentation skills is yet to be investigated. Nielsen ( 2015 ) argued that classroom tasks should transcend the school walls and involve an authentic audience other than their classmates, because this would give students an opportunity to immediately and clearly see the meaning of their work (Purcell-Gates et al., 2002 ). However, in the field of FL education, in particular with regard to the courses that prepare students for public speaking skills, the construct of an audience is often conveniently used to refer to the instructor or students’ classmates; the adoption of an extramural live audience for real-life meaningful tasks is seldom seen.

Research Questions

This study intended to establish that authentic activities that are designed and regularly implemented in consideration of the aforementioned three features noted by Casteleyn ( 2019 ) will equip students with the kind of mindset and oral presentation skills that are key to the success of communicative FL oral activities outside the classroom. To establish the above contention, this study incorporated drama-based activities into the teaching of FL presentation skills, and explored whether such a course design would enhance college students’ FL presentation skills as well as their self-perceived competence. Two research questions were explored:

Do drama-based tasks implemented with classroom and real-life audiences differentially promote learners’ FL oral presentation performance?

Do drama-based tasks implemented with classroom and real-life audiences differentially enhance learners’ self-perceived FL oral presentation performance?

Participants

This research spanned two consecutive semesters. It involved two presentation classes from an Applied English department in a Taiwanese university. The two classes consisted of 20 and 22 students, respectively, with one of them experiencing the drama-based teaching method (the experimental group) and the other going through a traditional (no-drama) presentation training (the comparison group). Irrespective of differences in training methods, the two classes each met for 2 h per week, 18 weeks a semester with the aim of helping the students acquire verbal and nonverbal presentation skills so as to present their ideas to an audience clearly, logically and comfortably. The instructor-as-researcher developed class activities within the domain of an oral discourse training class based on her specialty so as to achieve the aforementioned class goal. By comparing two groups of students using two different teaching methods, the researcher hoped to investigate which method promoted better oral outcomes, and whether there was a difference in the intended learning gains—a practice also seen in other classroom-based research (e.g., Wacha & Liu, 2017 ).

An IRB approval was obtained prior to the study. The study strictly adhered to the ethical procedures approved and prescribed by the IRB. All participants had sufficient time to review the content and syllabi of the two classes under investigation. Importantly, they could decide if they would allow the researcher to analyze their data; while going over the syllabi in the first meeting, the instructor clearly informed them of the grading criteria, and explicitly told them that whether or not they decided to be a part of the study would not have any impact on their grades. All class activities—including the ones used in the experimental or comparison groups—are pedagogical possibilities that instructors could imagine seeing in an oral-based class. In this study, all students voluntarily agreed to participate and express their interest in knowing the result of this study.

Before the research, all participants had studied EFL for 8–12 years, and all were third-year college students admitted to the same department at the same university in Taiwan through standardized national examinations set at level B1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001 ). In their senior high school and college life, they had received training emphasizing English as the target FL. Importantly, they had similar weekly exposure to the target language, as gleaned from a screening survey administered prior to the onset of this study. Before they came to this class, they had not received formal training in oral presentation. Before the study began, all participants had to make a presentation. To avoid rating bias, two public speaking professionals who did not know the participants were invited to rate the participants’ performance on the presentation. Importantly, to enhance the validity of the two professionals’ ratings, the participants’ presentation recordings produced before and after the study were blindly presented to and scored by the two professionals without any time labels (such as pre- and/or post-study speech samples). The raters had no other interaction with the class and did not know the student participants personally. An independent t test ensured that no significant differences [ t (40) = − 0.65, p = 0.517] in the initial levels of oral presentation performance existed between the comparison and experimental groups. Additionally, the two groups’ self-perceptions of the six presentation techniques under investigation (i.e., structure, audience adaptation, speech content, posture, nonverbal delivery, visual aid handling) were not significantly different, showing skills homogeneity for the two groups of students at the beginning of the study.

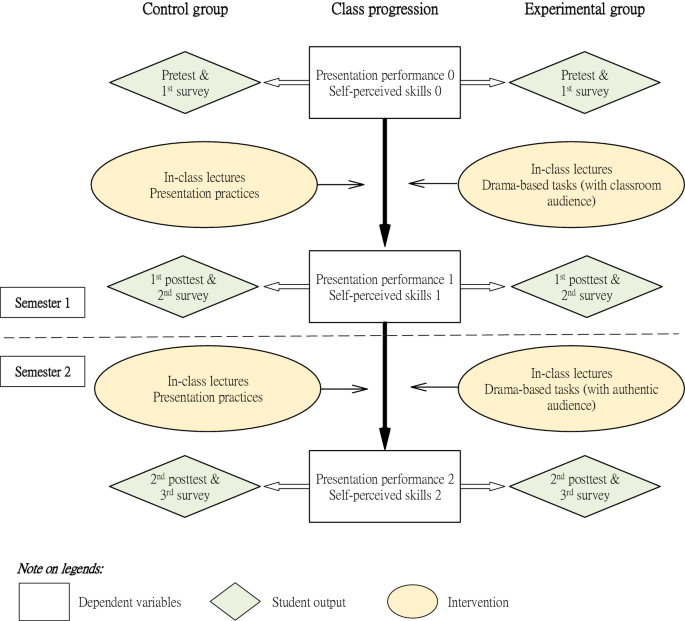

This research was a time-series classroom-based quasi-experimental study, recruiting students from two intact classes (see Rogers & Révész, 2020 ) and assigning them to the experimental condition (involving the drama-mediated treatment) and the comparison condition (involving the non-drama-mediated treatment consisting of ordinary public speaking training). Following the protocol of this type of research, the researcher collected the participants’ language samples assigned to these two conditions through multiple observations and made pairwise comparisons over a set period of time; as such it “allow[s] insight into the time course of language development, including changes that may be immediate, gradual, delayed, incubated, or residual…as well as the permanency of any effects resulting from a treatment” (p. 6). Addressing such a research method, Sato and Loewen ( 2019 ) noted that classroom-based quasi-experimental studies “[provide] learners with interventions that were seamlessly deployed in the genuine classroom contexts which permitted the examination of authentic classroom instruction with minimal disturbance” (p. 31). In this study, the comparison class received a standard regimen of presentation practice with lectures as supplemental sections; the experimental class received drama-based presentation practice, also with lectures as supplemental sections. The dependent variables under investigation were oral performance and six self-perceived presentation techniques (i.e., structure, audience adaptation, speech content, posture, nonverbal delivery, visual aid handling). Drama-based activities were the independent variable. The research design is summarized in Fig. 1 .

Flow chart of the research design

The Experimental Group

In the first semester, the experimental students practiced dramatic tasks that emphasized specific drama and oral presentation elements, while in the second semester they put their skills together for the production of a complete play for an outside-the-classroom audience. The experimental group treatment is described in more detail below.

At the beginning of the class, students in the experimental group were informed in advance that they needed to turn picture books in their mother tongue (Chinese) into cohesive scripted plays in English, and perform them for children from the neighborhood community. The students had to work in teams throughout the two-semester time span, each exploring and dramatizing a selected picture book under the scaffold and guidance of the instructor from each weekly meeting session. Created by Taiwanese writers and illustrators, all the picture books were written for children in Chinese. They were mostly fantasy, realistic fiction, and fables, ranging from 30 to 40 pages, with themes of friendship, sharing, family, love, or respecting differences—issues highly relevant to the life of the participants of this study. Chinese picture books were deliberately chosen so that the participating students worked on the English translation to create authentic lines from the original Chinese source materials rather than relying on readily available texts from English picture books. To this end, the experimental group received a series of drama-based tasks designed according to the principle of task dependency (Nunan, 2004 ), meaning one task building upon the preceding tasks. Specifically, the tasks for the experimental group were divided into two inter-related stages in the two semesters: (1) drama-based treatment, and (2) enactment of a theatrical play. During the first stage, the students were led to experience a series of drama-based tasks that were designed to incrementally foster their oratory skills and sensitivity to the six key elements of drama proposed by Aristotle ( 1984 ), namely, theme, plot, character, language/diction, music, and spectacle (see below for more details).

During the second stage of the treatment, while continuing building and polishing their team-scripted play, the students had to turn the play into a task of story theater, that is, a team production to be performed outside the classroom with community children as the authentic audience. While the time length and the story titles were pre-determined by the teacher, students were given extensive flexibility to extend the theme of the picture book and to work on the English translation of the lines from the original source materials in Chinese, the plot, dialogue production, character depiction, stage props, and the procedures of the play.

It is also worth noting that the first stage (drama-based treatment) primarily aims to attain “systematic desensitization” and “skill training”—the first two features for effective use of drama prescribed by Casteleyn ( 2019 ) through regularly conducted drama/theater training and performance within the classroom. Next, the second stage continued enhancing “systematic desensitization” and “skill training” by enacting a theatrical play. Importantly, the second stage attempted to foster a positive state of mind through the involvement of an audience beyond the classroom (cognitive modification)—the third feature prescribed by Casteleyn. The ensuing paragraphs will first detail how the drama-based treatment that took place in the first semester collectively and systematically equipped the students with the skill and competence that are key to the success of the second stage, namely enactment of a theatrical play.

First Stage: Drama-Based Treatment

During the first semester, the students were led to experience a variety of drama-based tasks, including storytelling, role play, character review, monologue, and play rehearsal in the classroom, which aimed to help the students think more deeply about the language and acting elements of their play production and characters. Details of these drama-based tasks, which aimed at fostering the aforementioned six drama elements proposed by Aristotle, are offered below:

Storytelling: each student chose or created a character in the story and told what happened in the story from his or her character’s point of view. This activity prompted the team to develop the plot of their final play production

Character review: each student made a self-introduction of his/her character’s part. In order to do so, the student must use imagination to consider onstage and offstage details about the character, such as age, physical attributes, personality characteristics, childhood, family history, education/work experience, habits, recreations, likes and dislikes, dreams, etc. This activity prompted the experimental group participants to make their characters come to life with a fuller form in the final play production

Monologue: each student chose a significant event in the story and commented on it from his or her character’s viewpoint. In order to do so, the student had to take into consideration the character’s personality traits and psychological state during that event. This activity prompted the experimental participants to develop the language/diction/dialogues of the characters in the final play production

Dress rehearsal: after becoming familiar with the plot, characters and language, the participants as a team made up more dialogues to fit the action and events of the story. They also designed stage props, costumes and visual effects, which corresponded to Aristotle’s dramatic element of spectacle. In addition, they had to produce sound effects and music for their story, which were equivalent to the dramatic element of music. Then the team acted out the story in a dress rehearsal. Afterwards the team sought feedback from the class and the teacher for production improvement. Additionally, the students constantly received comments from the instructor and their peers, and had their syntax, grammar, and phonology corrected in the classroom. It should be noted that up to this point the four drama-based tasks took place in the classroom.

Second Stage: Enactment of a Theatrical Play

Story theater: five teams produced five scripted plays, now all complete with the six elements of drama. They were publicly performed as a series of five theater productions for children in the local community; additionally, the children’s parents were also in the audience. During their performance, the students were encouraged to interact with the audience, either verbally or non-verbally, whenever possible and appropriate.

The Comparison Group

The comparison group did not receive any drama-based treatment. Instead, the group received a series of lectures on presentation skills, and were led to experience corresponding oral presentation practices during the two semesters (Fig. 1 ). They spent the same amount of activity time as that of the experimental group. The practice presentations, listed as follows, were designed to correspond to the nature of the tasks done by the experimental group:

A speech on what happened in the summer vacation [storytelling]

Self-introduction [character review]

A speech to comment on something the student felt strongly about [monologue]

A speech with interactions with the class audience [dress rehearsal]

A speech requiring interaction with the class audience [story theater]

Instruments

Two quantitative measures were used in this study: professional rater judgement and the self-perceived presentation techniques questionnaire (SPPTQ). While the former was used to answer research question#1, the latter was employed to address research question#2. Both the professional ratings and the results of the questionnaire were analyzed using the independent t test. A qualitative measure (i.e., post-study interview) was conducted to substantiate the findings of the quantitative measures.

Quantitative Measures

Professional raters’ judgment: throughout the study, which lasted for an academic year, all participants were tested on oral presentation at the beginning of the research, at the end of the first semester, and at the end of the second semester; the three presentations involved students making three informative speeches that were comparable in terms of length and difficulty level. The three presentation grades served as the pre-test, first post-test, and second post-test of oral presentation performance. Two professors who were public speaking experts rated the participants’ performances using the same grading guidelines on ten items: voice volume, speed, intonation, pronunciation, posture, gesture, eye contact, speech structure, language use, and material choice. Each item scored 10 points, making the total of a presentation 100 points. The inter-rater reliability of the two raters was 0.92. The two raters rated all the pre- and post-test presentations. The average of the two raters’ scores on the presentation performance was taken to represent the achievement score of that particular presentation.

The self-perceived presentation techniques questionnaire: the self-perceived presentation techniques questionnaire (SPPTQ), a 5-point Likert scale, was used to assess the participants’ perceptions of their own verbal and nonverbal communication behaviors in English presentation. It comprised 23 items, which gauged the skills on six dimensions: voice, facial expression, gesture, speech structure, speech content, and audience orientation. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the questionnaire was 0.922. The questionnaire was administered to both the experimental and comparison groups three times for their responses on the levels of their self-perceived presentation techniques: at the beginning of the research, at the end of the first semester, and at the end of the second semester, respectively.

Qualitative Measure

A post-study interview was administered to the members of the experimental group to elicit their qualitative feedback and reflection regarding their experience. The purpose was to produce qualitative information to substantiate how the experimental group students perceived the impacts of the drama-based tasks on their presentation learning. Feedback questions were adopted from Chen and Brown ( 2012 ) with necessary modification of the subject of inquiry from writing to presentation. In order to elicit in-depth thoughts and more responses, the participants were free to use Mandarin Chinese, their mother tongue, for reflection.

Data coding were conducted by the two raters, who constantly double-checked with each other, making sure both agreed with each other in the first round of data previewing. Rating alignment was then established. During the task of data sorting, recurring learner comments and opinions were identified according to principles of thematic data analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ). Throughout the process of categorizing the data into themes and key points, the two raters frequently met with each other to discuss and resolve coding differences, and reached consensus on theme categorization as well as key-point extraction through discussion. The inter-rater reliability was 0.85.

The results and relevant discussion vis-à-vis the two research questions are reported below.

Quantitative Results

RQ1: do drama-based tasks implemented with classroom and real-life audiences differentially promote learners’ FL oral presentation performance?

To understand the learners’ progress in presentation performance, the presentation scores of the first and second post-tests by the experimental and comparison groups are presented respectively in Table 1 . Table 1 summarizes the statistical results of independent t tests in the two stages of the drama-based tasks. The p value [ t (40) = − 0.152, p = 0.880] of the first post-test scores indicated that after engaging in drama-based exercises in the classroom at the end of the first semester of drama-based tasks, the presentation performance of the experimental group did not differ significantly from that of the comparison group, which performed non-drama exercises for practicing EFL presentation. That is, the two approaches had comparable impact on participants at the end of the first semester.

However, the p value [ t (40) = 2.061, p = 0.046] from the second post-test scores of the two groups at the end of the second semester of the study, that is, applying the extramural drama activities to the experimental group, showed that the presentation performance of the experimental group differed significantly from that of the comparison group. The statistics showed that after practicing and conducting the dramatic play to the child audience, the experimental group performed significantly better in terms of oral presentation, with significantly smaller variation in means (as gleaned from the smaller SD value, 7.001). This further indicates that the drama-based treatment—especially the one that involves an audience beyond the classroom setting—was probably more effective in terms of reducing inter-learner variation than the traditional oral training.

RQ2: do drama-based tasks implemented with classroom and real-life audiences differentially enhance learners’ self-perceived FL oral presentation performance?

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the statistics by independent t tests of six presentation techniques perceived by the experimental and comparison groups in the two stages of the drama-based tasks. The p values of the first post-test scores across all of the six self-perceived presentation techniques in Table 2 showed that they were all larger than 0.05. This indicated that after conducting drama-based tasks at the end of the first semester, the self-perception of all of the six presentation techniques held by the experimental group did not differ significantly from that by the comparison group, which did not receive drama-based tasks for practicing L2 English presentation.

However, in Table 3 the p values obtained at the end of the second semester show that for three of the presentation techniques, that is, structure/organization technique, audience sensitivity, and speech content, the differences in the self-perceived scores were large enough to register as significant, with p values less than 0.05. Thus, they differed significantly from their counterparts in the comparison group after presenting the drama to the audience.

Qualitative Results

Affective gains.

The ensuing paragraphs report the analysis of qualitative data from the experimental group. Achievements reported statistically can be further highlighted by some contextual knowledge of the affective perspectives of the participants regarding their experiences. Attention to these affective conditions sheds light on the agents’ perceptions of their own progress and performance. Four themes, (1) task authenticity, (2) task meaningfulness, (3) teamwork and friendship, and (4) enhanced presentation performance, were frequently mentioned in the post-study interviews.

Task authenticity The experimental group experienced an authentic oral presentation task during the second semester theatrical production, where there was a clear relationship to the real world with authentic purposes and authentic language (Skehan, 1998 ). All the participants were deeply impressed by the task authenticity they experienced from the reciprocal, synchronized, unpredictable audience interactions (Beatty, 2015 ; Thornbury, 2010 ; see also Widdowson, 1990 ) and the pressure these elements created for the performers to respond effectively. During the second semester, they had to present the play for an audience other than their classmates. This was an experience not available during the first semester, and it generated different feelings. Some participants expressed how they felt as follows:

We would find a vacant classroom and rehearse, without an audience of course, so we did not feel pressured. We could always rewind to where we went wrong. But not for the real performance. In a real performance, you only get one chance and you have to do the best you can to make it a success. (Participant 4E) During rehearsals, we did not feel any differences. To me they were just like normal presentation practices—very normal. But during the performance for children, we felt like we had no control and were totally at the disposal of others. There was no going back if we did anything wrong. Our state of mind was totally different. (Participant 2E)

Past research pointed out that it is effective to improve learners’ linguistic and communicative ability through authentic tasks (Ellis, 2000 ; Kiernan & Aizawa, 2004 ; Nunan, 2004 ; Willis, 1996 ). The results of the current study suggest that students’ oral presentation skills might be further developed by the authenticity inherent in the experience of a theatrical production.

Task meaningfulness From the theatrical production, the participants saw their skills being used to create something meaningful. In the process of accomplishing the drama task, they came to understand its importance, and they felt a great sense of achievement. The team members in the experimental group realized that they played critical roles in the play production and had the power to shape the scenes. They were entrusted with the responsibility to teach children English in an educational and fun way via an English play production. They had the sense that their ideas were important and would be listened to by the audience. During the theatrical performances, they deeply appreciated that they could make a difference to the pupils.

I was really moved by the fact that the kids enjoyed our show sang and danced with us, and their parents also sang and danced with us too! After our show, they also gave me great feedback and supportive comments. I was truly moved and felt that all the efforts were worthwhile. (Participant 14E)

I was fully rewarded by the satisfied smiles of the children and the positive feedback from their parents. I felt that all the efforts paid off. (Participant 11E)

It is reported that meaningful contexts promote language skill acquisition (Lyster & Sato, 2013 ). Participants’ acknowledgement of the meaningfulness of a theatrical task as a learning opportunity in this study agreed with these previous research findings.

[I] truly feel that it was great to engage in this activity. It’s a very nice experience. (Participant 12E)

I think it is really wonderful for a course to offer such an opportunity of putting on a theatrical show like this. (Participant 17E)

Teamwork and friendship One of the most important lessons the experimental group learned was the importance of teamwork. The phrase “A team can achieve much more than a single individual” was mentioned again and again. Without a doubt, this illustrated that the drama-based project developed teamwork. The theatrical performance helped the students appreciate the benefit of working cooperatively with a group. They learned that teamwork was required in every link of the team project, from props production, skit writing, props transportation, to collaboration in the play production. Each teammate made his/her unique contribution to the success of the drama project. Comments from the experimental group supported that the theatrical project could be used to build a sense of community in a team.

We made props together; we discussed the play script together; we rehearsed together; we coordinated with each to make our play production as good as it could be. Our comradeship grew and our friendship became better. (Participant 12E)

I learned that team members must coordinate with each other to achieve the common goals, which an individual alone cannot do. (Participant 3E)

Authentic tasks require collaborative problem-solving during the process and during the interaction with peers (Ellis, 2000 ; Kiernan & Aizawa, 2004 ; Nunan, 2004 ; Willis, 1996 ). Notably, enhanced collaboration was primarily reported from those participants in the experimental group. As the course went on, the mutual understanding and trust grew deeper among the team members. Because the drama-based task requires open, regular communication among the participants, they developed a bond and the ability to rely on each other when extemporaneous reactions must be taken to handle on-site contingencies from the audience. Tacit understanding of each other made the show resistant to unplanned disruptions.

I learned the importance of interactions with partners. I used to prefer completing assignments alone. After this task, I learned the importance and benefits of teamwork. Solidarity among members made me happy, and the power it brought made me feel that I will not dread obstacles because I have partners to help solve the problems. (Participant 8E)

Enhanced presentation performance An overwhelming proportion (91%) of the experimental participants testified at the post-study interviews that their presentation improved significantly after the drama-based activities involved real-life audiences. Compared to their predispositions at the beginning of the class, the participants indicated that during the second semester, they became more aware of the importance of liveliness required in presentations for a real-life audience; they were also more aware of their presentation performance and related skills and were able and willing to critique themselves. Such meta-cognition is important in learning for any progress to be made in the future. Many of them attributed the cause to the authentic theatrical task in the second semester. Some of the excerpts from the participants highlighted this theme:

Now, when I present in English, I become more expressive, unlike the monotonous and dry memorization before. (Participant 5E)

My stage presence and oral ability are better than before, as I used this opportunity [dramatic play in public] to push myself to practice over and over, and I have developed a habit of constantly paying attention to and correcting my pronunciation. (Participant 4E)

After the play production, I can maintain a pleasant facial expression, I can speak more fluently, and I do not get as nervous as before. (Participant 3E)

Before the play production, I could not speak in English fluently. Practice certainly made a lot of difference. It is true that by speaking English often, you can remember and recount things [in English] more naturally. (Participant 2E)

At the beginning of the class, whenever I faced a presentation, I often did not know how to report my content. However, by this theatrical production, I think my presentation ability has made some progress. (Participant 19E)

Gains in Self-Perceived Presentation Techniques

The participants’ qualitative reports on their enhanced presentation performance are particularly relevant to three elements of the SPPTQ survey on self-perceived presentation techniques, namely structure, content, and audience.

Structure The team members needed to discuss how to develop their storylines and put together a unified drama performance. This process involved proposing new ideas about the plot, activities, and how to organize them, which heightened their creative ability and structuring skills. One student described the process of planning the theatrical play in detail. As seen from the quote below, the participants’ comments revealed that the development of dramatic structures provides useful training for properly organizing a speech.

The first time I read through the picture book, I immediately remembered every single part of the plot. Then I started to prepare for the first presentation assignment assigned by the teacher—telling the story and summarizing the plot. Next was the midterm presentation—my character’s monologue. The two assignments made me all the more aware of every link and detail in the story, plus possible scenarios that my character might encounter, all devised by myself! I consulted with my team members. We incorporated all the add-on plot points that we could think of into our dramatic play and finalized our lines in the script. During the process our team discussed all the links in the play, although there were still some conflicting ones when we rehearsed in class. Nevertheless, thanks to the valuable feedback from the teacher and the classmates, we brainstormed even more plot points for our play! (Participant 18E)

Not only did the year-long process prompt the participants to notice the importance of plot structure and enable them to polish it, but it also heightened their awareness of speech structure which extended to other learning subjects.

After rehearsing so many times, there was virtually no problem with the major structure and procedure of the play. They were all smoothed out. (Participant 15E)

The biggest difference that happened for me [before and after] is the precision of language and attention to grammar. After all, I was giving a performance to children on behalf of my Department, so I must be careful about every word I said. This mentality also prompted me to pay extra attention to logic whenever I communicate in Chinese or English instead of treating communication lightly. (Participant 15E)

It should be noted that most of the classroom drama-based activities in the first semester were separate enactments, while the story and the script provided a unified plot structure for the theatrical activity in the second semester. It turned out that the experimental group participants acting out a structured story in the second semester made more significant progress than in the first semester. It is possible that the exposure to the structured plot and story concept (e.g., beginning, body, ending) provided in the form of a story/script deepened their concept of structure in English oral presentations. As structured enactment of drama was found to result in more heightened writing achievement than unstructured enactment (Podlozny, 2000 ), likewise structured enactment of drama in front of an authentic audience proved more effective in terms of heightening the sensitivity to presentation structure in the present study. It makes sense that enactment of a structured story would be more supportive of the self-awareness of structure needed in oral presentation.

Content The effort and time spent turning a picture book into an English script from scratch encouraged the students to pay more attention to what content to put in and how to arrange the plot points in a proper sequence. Some of the excerpts from the participants’ comments in this regard are as follows:

Before, when I faced a presentation assignment in the presentation class, I often found that what I wanted to say was incomplete. However, this time, for the theatrical play, I did what I was supposed to do! (Participant 19E)

This task prompted me to adjust the content of my presentation according to contingencies…Therefore, I think performance outside the classroom is more effective than presentation training in the classroom. (Participant 6E)

Because of this task, I have to speak English most of the time, so I gradually got used to speaking English. I also started to notice the word choices of friends around me and improved my own when expressing myself in English. This is a good phenomenon. (Participant 8E)

The above excerpts illustrated how the series of drama-based activities actually helped the participants with respect to presentation structure and content.

Audience Feedback from the participants clearly indicated that the experience of enacting a play production for an audience of children fostered the audience-centered mentality in several aspects: the level of English, audience interactions, and audience engagement. The participating students greatly anticipated what kinds of audience response there might be. It is plausible that the habits were transferred over from preparing for a theatrical play to the planning of their individual oral presentations.

Now I will change the ways of expressing myself according to different audiences, hoping that everyone understands me. Before, when I spoke, I was only concerned about myself. I will continue to hold this spirit and bravely express my thoughts in English. (Participant 7E)

Because the production was for children, I would think twice about whether I made any grammatical errors before I actually spoke out. (Participant 9E)

Because the audience that I faced was composed of children, I had to slow down and change my inflections to keep the children engrossed in our performance. (Participant 11E)

During the acting out of the dramatic play, we had to make adjustments according to audience responses. If they are less responsive, we must assist each other as a team to liven up the atmosphere. Children’s level [of English] is something to be taken into consideration, too. When it comes to designing the procedure of our play, we must adjust it to the level of the children so that the show could go on smoothly. (Participant 14E)

The statistical analysis indicates that the presence or absence of drama-based instruction with a classroom audience did not create significantly different results in the first semester. However, there were significant effects arising from the second stage of the study in which a real-life audience was introduced and included as part of their learning experiences. In contrast to the drama intervention in the first semester, which did not reveal significant impacts on students’ presentation performance nor self-perceived presentation skills, significant effects on performance and these perception variables appeared in the second semester—the time at which the real-life audience began to be introduced to the drama-based treatment. This is the key to the success of the drama-based activities and what really allowed the FL learners to outperform their counterparts assigned to the ordinary public-speaking training activities. Such results provide empirical evidence aligned with the theoretical stipulations on the centrality of audience proposed by scholars from the realm of theater studies (Brook, 1996 ; Etchells, 1999 ; Grotowski, 2012 ). Moreover, the findings empirically establish the need to fine-tune the practice of utilizing drama activities in language skills acquisition (Cornett, 2003 ; Dunn et al., 2013 ; Kao & O’Neill, 1998 ; Thompson & Rubin, 1996 ), necessitating the inclusion of a real-life audience as a crucial element of drama-related activities in language learning.

Accordingly, based on the findings of this study, three major pedagogical implications are proposed. First, it empirically establishes the need to include and implement regular (weekly) drama-based activities in an L2 speaking curriculum. The observation that the participants assigned to the drama-mediated experimental condition were capable of exhibiting better presentation skills and a more positive mindset to improve their oral skills entails that instructors should make drama-based activities at least a part of the curriculum. Second, the observation that the gain of the experimental group only started to manifest itself during the second semester points to the need to implement drama-based activities on a long-term basis (for at least two semesters); the positive effect of drama-based activities on FL learners’ oral presentation skills and mindset might not be salient if such activities only last for a semester.

Third, it is important to note that the evidence in the present study validates that long-term implementation of drama-based activities is only a necessary but insufficient condition for promoting FL oral presentation skills. The experimental group participants’ gain only started to become more salient after the drama-mediated treatment involved a real-life audience—a critical element that sets apart the experimental treatment implemented during the first and second semesters. Thus, to maximize the effectiveness of drama-based activities, the activities require a catalyst such as an authentic audience beyond the classroom for it to bloom. When the drama-based activities moved beyond the isolated pedagogical setting to include elements of real-world setting and interaction with an authentic audience, they became a more powerful tool for presentation training. Hence, this study provides an empirical demonstration that the nature of the audience in drama-based activities should be taken into consideration when searching for effective pedagogic tasks for FL presentation training. While the previous research reported the general effectiveness of drama-based language learning activities in promoting speaking skills (Di Pietro, 1987 ; Hwang et al., 2016 ; Kao & O’Neill, 1998 ; Kao et al., 2011 ; Lee, 2015 ; Miccoli, 2003 ; Whiteson, 1996 ), this study further demonstrates the nuanced effects of different types of drama-based practices and the key locus of their effects—the authentic audience beyond the classroom setting.

Consistent with the quantitative data reported above, the results of perception surveys and reflections also jointly show that public dramaturgical tasks that involve an authentic audience had effectively helped learners develop a repertoire of skills, in particular regarding enhanced audience awareness (which allowed the learners to keep the audience in mind when planning and delivering a presentation), sensitivity toward the structure of their presentation (which empowered the learners to effectively use the beginning-middle-end elements), and attention to content (which challenged the learners to frequently consider what elements to put in and how to present those elements for optimal outcomes). The above benefits echo some of the findings reported by Hung ( 2011 ), Warschauer ( 1999 ), and Yeh ( 2018 ). In addition to its positive impact on self-perceived presentation skills, drama-based activities also exerted a positive influence on the participants’ affect, fostering a more positive mindset toward collaborative learning with their peers (teamwork and friendship) and helping them to better see the purpose of their practices (task meaningfulness). Notably, the participants’ qualitative reports clearly indicated that virtually all the significant changes, including both the actual presentation performance and the positive impact on the aforementioned self-perceived presentation elements and mindsets, all occurred in the second stage of the research. This entails that positive changes in the participants’ behavior, performance, and mindset were significantly boosted only after the drama-based project was held in public. The task of presenting a dramatic play aimed at children had created a meaningful, educational, mind-changing platform where the FL learners were more willing to make efforts to apply the learned presentation techniques, and the learners were more likely to believe that what they were learning could genuinely make a difference to their presentation skills. Accordingly, in light of the findings of this study, to effectively enhance college FL learners’ presentation skills and to foster a positive state of mind for their presentation practices, instructors may want to systematically and regularly include drama-based tasks in a year-long (public-speaking) curriculum, and implement such tasks involving an audience beyond the classroom setting.

This study empirically establishes the effectiveness of drama-based tasks in promoting FL learners’ oral presentation performance and uncovers their self-perceived acquisition in presentation techniques. Analysis of the participants’ diachronic performance data showed that their oral performance was significantly enhanced only after they started to present for a real-life audience other than their classmates. Analysis of the survey and retrospective data also indicated the participants’ attention to three presentation skills—structure, audience adaptation and content—was significantly raised after their presentation involved a real-life audience.

Nevertheless, the findings of this study should be interpreted with care, given the relatively small sample of the study. Future research should include a larger population and a wider site selection for greater generalizability of research implications. A disclaimer should be made here that by no means does this article contend that speech presenters must be great actors. Furthermore, in spite of the insights of this study, it is important to note that the evidence of this study is only pertinent to the impact of drama-mediated tasks on the aspects of presentation skills investigated in this study (e.g., structure, audience adaptation and content). It is also worth noting that some types of drama activities may be inherently more supportive than others for certain learning outcomes: for example, structured dramatization may be more suitable for giving learners a deeper understanding of structure that is required in other types of communication.

Data Availability

The questionnaire that supports the findings of this study is available on request from the first author, Y. J. Lee. Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so raw data are not available.

Andresen, H. (2005). Role play and language development in the preschool years. Culture and Psychology, 11 (4), 387–414.

Article Google Scholar

Aristotle. (1984). Poetics . In: I. Bywater (Trans.). McGraw-Hill.

Beatty, K. (2015). Language, task and situation: Authenticity in the classroom. Journal of Language and Education, 1 (1), 27–37.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101.

Breen, M. P. (1985). Authenticity in the language classroom. Applied Linguistics, 6 (1), 60–70.

Brook, P. (1996). The empty space: A book about the theatre . Simon and Schuster.

Casteleyn, J. (2019). Playing with improv(isational) theatre to battle public speaking stress. The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 24 (2), 147–154.

Google Scholar

Celce-Murcia, M. (2008). Rethinking the role of communicative competence in language teaching. In E. A. Soler & M. P. S. Jorda (Eds.), Intercultural language use and language learning, chap. 3 (pp. 41–57). Springer.

Chamot, A. U. (2009). The CALLA handbook: Implementing the cognitive academic language learning approach (2nd ed.). Pearson Education.

Chen, C. C., & Brown, K. L. (2012). The effects of authentic audience on English as a second language (ESL) writers: A task-based, computer-mediated approach. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 25, 435–454.

Choi, J. (2008). The role of online collaboration in promoting ESL writing. English Language Teaching, 1 (1), 34–39.

Conard, F. C. (1992). The arts in education and a meta-analysis . Unpublished doctoral thesis, Purdue University, IN.

Cornett, C. E. (2003). Creating meaning through literature and the arts: Arts integration for classroom teachers . Pearson Education.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages . Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages . Accessed 11 Jan 2021.

Di Pietro, R. J. (1987). Strategic interaction: Learning languages through scenarios . Cambridge University Press.

Dunn, J., Harden, A., & Marino, S. (2013). Drama and writing: ‘Overcoming the hurdle of the blank page.’ In M. Anderson & J. Dunn (Eds.), How drama activates learning: Contemporary research and practice (pp. 245–259). Bloomsbury.

Ekiert, M., Lampropoulou, S., Révész, A., & Torgersen, E. (2018). The effects of task type and L2 proficiency on discourse appropriacy in oral task performance. In N. Taguchi & Y. Kim (Eds.), Task-based approaches to teaching and assessing pragmatics, chap.10 (pp. 248–263). John Benjamins.

Ellis, R. (2000). Task-based research and language pedagogy. Language Learning Research, 4 (3), 193–220.

Enright, D. S., McCloskey, M. L., & Savignon, S. J. (1988). Integrating English: Developing English language and literacy in the multicultural classroom . Addison-Wesley.

Etchells, T. (1999). Certain Fragments: Contemporary performance and forced entertainment . Routledge.

Grotowski, J. (2012). Toward a poor theatre . Routledge.

Hafner, C. A., & Miller, L. (2011). Fostering learning autonomy in English for science: A collaborative digital video project in a technological learning environment. Language Leaning and Technology, 15 (3), 68–86.

Hung, S. T. (2011). Pedagogical applications of Vlogs: An investigation into ESP learners’ perceptions. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42 (5), 736–746.

Hwang, W. Y., Shadiev, R., Hsu, J. L., Huang, Y. M., Hsu, G. L., & Lin, Y. C. (2016). Effects of storytelling to facilitate EFL speaking using web-based multimedia system. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29 (2), 215–241.

Kao, S. M., Carkin, G., & Hsu, L. F. (2011). Questioning techniques for promoting language learning with students of limited L2 oral proficiency in a drama-oriented language classroom. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 16 (4), 489–515.

Kao, S. M., & O’Neill, C. (1998). Words into worlds: Learning a second language through process drama . Ablex.

Kelner, L. B. (2002). The creative classroom: A guide for using drama in the classroom, preK-6 . Heinemann.

Kiernan, P. J., & Aizawa, K. (2004). Cell phones in task based learning: Are cell phones useful language learning tools? ReCALL, 16 (1), 71–84.

Lee, B., Patall, E., Cawthon, S., & Steingut, R. (2015). Meta-analysis of the effects of drama-based pedagogy on K-16 student outcomes since 1985. Review of Educational Research, 85, 3–49.

Lee, Y. J. (2015). Drama as a training aid to enhancing underachievers’ achievement in the EFL public speaking context. The International Journal of Assessment and Evaluation, 22 (3), 25–42.

Lin, V., Kang, Y. C., Liu, G. Z., & Lin, W. (2016). Participants’ experiences and interactions on Facebook group in an EFL course in Taiwan. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25 (1), 99–109.

Lin, M. H., Li, J. J., Hung, P. Y., & Huang, H. W. (2014). Blogging a journal: Changing students’ writing skills and perceptions. ELT Journal, 68 (4), 422–431.

Long, M. H. (2015). Second language acquisition and task-based language teaching . Wiley.

Lyster, R., & Sato, M. (2013). Skill acquisition theory and the role of practice in L2 development. In M. P. García-Mayo, M. J. Gutiérrez-Mangado, & M. Martínez-Adrián (Eds.), Contemporary approaches to SLA (pp. 71–91). John Benjamins.

Mages, W. K. (2008). Does creative drama promote language development in early childhood? A review of the methods and measures employed in the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 78 (1), 124–152.

McCaslin, N. (Ed.). (1990). Creative drama in the primary grades: A handbook for teachers (Revised). Players Press.

Miccoli, L. (2003). English through drama for oral skills development. ELT Journal, 57 (2), 122–129.

Nielsen, K. (2015). Teaching writing in adult literacy: Practices to foster motivation and persistence and improve learning outcomes. Adult Learning, 26 (4), 143–150.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching . Cambridge University Press.

Phinney, M. (1991). Computer-assisted writing and writing apprehension in ESL students. In P. A. Dunkel (Ed.), Computer assisted language learning and testing: Research issues and practice (pp. 189–204). Newbury House.

Pilkington, R., Bennett, C., & Vaughan, S. (2000). An evaluation of computer mediated communication to support group discussion in continuing education. Educational Technology and Society, 3 (3), 349–360.

Podlozny, A. (2000). Strengthening verbal skills through the use of classroom drama: A clear link. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 34 (3/4), 239–275.

Purcell-Gates, V., Degener, S. C., Jacobson, E., & Soler, M. (2002). Impact of authentic literacy on adult literacy practices. Reading Research Quarterly, 37 (1), 70–83.

Rogers, J., & Révész, A. (2020). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs. In J. McKinley & H. Rose (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of research methods in applied linguistics . Routledge.

Rose, C. (1987). Accelerated Learning . Dell.

Sato, M., & Loewen, S. (2019). Methodological strengths, challenges, and joys of classroom-based quasi-experimental research. In R. M. D. Keyser & G. P. Botana (Eds.), Doing SLA research with implications for the classroom: Reconciling methodological demands and pedagogical applicability (pp. 31–54). John Benjamins.

Skehan, P. (1998). Task-based instruction. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 18, 186–268.

Stinson, M., & Winston, J. (2011). Drama education and second language learning: A growing field of practice and research. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 16 (4), 479–488.

Thompson, I., & Rubin, J. (1996). Can strategy instruction improve listening comprehension? Foreign Language Annals, 29 (3), 331–342.

Thornbury, S. (2010, August 15). C is for communicative [Web blog message]. http://scottthornbury.wordpress.com/2010/08/15/c-is-for-communicative/

Wang, Y. C. (2015). Promoting collaborative writing through wikis: A new approach for advancing innovative and active learning in an ESP context. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28 (6), 499–512.

Wacha, R., & Liu, Y. T. (2017). Testing the efficacy of two new variants of recasts with standard recasts in communicative conversational settings: An exploratory longitudinal study. Language Teaching Research, 21 (2), 189–216.

Warschauer, M. (1999). Electronic literacies . Erlbaum.

Whiteson, V. (1996). New ways of using drama and literature in language teaching. New Ways in TESOL Series II. Innovative Classroom Techniques . TESOL.

Widdowson, H. G. (1990). Aspects of language teaching . Oxford University Press.

Willis, J. (1996). A Framework for task-based learning . Longman.

Yeh, H. C. (2018). Exploring the perceived benefits of the process of multimodal video making in developing multiliteracies. Language Teaching and Technology, 22 (2), 28–37.

Zhang, H., Hwang, W. Y., Tseng, S. Y., & Chen, H. S. L. (2019). Collaborative drama-based learning in familiar contexts. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57 (3), 697–722.

Download references

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (Grant No. 104-2410-H-025-015).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Applied English, National Taichung University of Science and Technology, Taichung, Taiwan

Yow-jyy Joyce Lee

Department of English, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan

Yeu-Ting Liu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by YJL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by YJL and both authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yeu-Ting Liu .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lee, Yj.J., Liu, YT. Promoting Oral Presentation Skills Through Drama-Based Tasks with an Authentic Audience: A Longitudinal Study. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 253–267 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00557-x

Download citation

Accepted : 22 February 2021

Published : 15 March 2021

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00557-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- EFL presentation

- Drama-based language teaching

- Authentic audience

- Oral skills

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Publishing Policies

- For Organizers/Editors

- For Authors

- For Peer Reviewers

An Insight to Attitudes and Challenges in Oral Presentations Among University Students

Oral presentation skills are often seen as important skills that university students need to possess once graduated. However, face to face oral presentation is still seen as one of the biggest challenges a student face as they often experience nervousness and shyness, give no eye contact, do not address the audience, and many more. With this in view, more research evidence is needed to understand students’ attitude towards oral presentation, oral presentation courses and the difficulties that students’ face when presenting. Hence, this study has two aims. The first is to investigate students’ attitude towards oral presentations skills and oral presentation courses. Secondly, this study aims to find out the difficulty that students face when giving oral presentations. A quantitative analysis was carried out to analyze the data. The data was collected among 145 university students from an oral presentation course in a selected university. The data obtained was analyzed for mean and percentages using the SPSS version 26. This study found that though students are aware on the importance of oral presentation skills, many are still facing challenges when doing it. Results yielded from four aspects which are from the general presentations challenges, linguistic, background knowledge, and psychological challenges. It is hoped that this study will help to contribute to the understanding of oral presentations among university students.

Keywords: Anxiety , attitudes , challenges , oral presentation , university students

Introduction

Employers often regard communication skills (written, oral, and listening) as one of the most sought-after skills when hiring ( Alshare & Hindi, 2004 ). It is one of the reasons why job interviews are conducted, which is to assess candidate’s communication skills. Oral presentation is the most popular speaking genre in classes as well as the workplace ( Chang & Huang, 2015 ). Most higher education courses include presentations as a method of assessment as well as classroom teaching and learning activities. In addition, successful communicative goals include effective oral presentation skills ( Evans, 2013 ). According to Van Emden and Becker ( 2017 ), being able to speak effectively to an audience is one of the benefits that students can gain from their tertiary education. Also, being able to present effectively is a valuable skill for students in whatever subjects they study and will consequently give greater achievements in their academics, career prospects, and their working lives in the future ( Van Emden & Becker, 2017 ).

Christensen ( 2002 ) observes that tertiary level students are provided with plenty opportunities to practice their presentation skills. These opportunities range from participating in group discussions, voicing out opinions during lectures, presenting formal speeches during orientation programs and other formal functions to defending their final year project to be assessed by others. In fact, oral presentation assessments are common assessment types in higher education and the function is to measure a student’s ability to create and deliver an engaging, informed, and persuasive argument ( Nash et al., 2016 ). On top of that, many higher educational institutions offer oral presentation and public speaking courses to further develop students’ presentation skills.

In line with the importance of oral presentation skills, University Teknologi Mara, Malaysia offers the course English for Oral Presentations to its students. The course focuses on oral communication theory and practice with emphasis on the importance of verbal and non-verbal communication skills. Learning takes place through a variety of activities to enhance learners’ ability to use the correct language for a presentation, to exploit a variety of materials and sources, and to use visual aids appropriately in oral presentations. Upon completion of the course, students are expected to develop skills to participate in speech communication activities confidently and competently.

Definition of oral presentation

The Learning Centre of The University of New South Wales ( 2010 ) defines oral presentation as a short talk on an assigned topic delivered to a group of people. In an oral presentation, one or more students will present their views and positions on a topic based on their readings or research. According to the University of Wollongong (n.d.) oral presentations can be observed in social events, classrooms and workplaces. In addition, an oral presentation at university shows a student's ability to communicate relevant information effectively in an interesting and engaging manner.

Students attitude towards oral presentations

There have been many past studies written on students’ attitude towards oral presentations. One study by Dansieh et al. ( 2021 ) was done to investigate the possible causes of anxiety towards oral presentations among tertiary students from Technical University, Ghana. The exploratory case study on 46 students used surveys and interviews as the instruments. The study found that even though students are aware of the importance of oral presentations, 63% of the respondents experienced anxiety when asked to give oral presentations. Additionally, 23.9 % experienced nervousness while another 13% experienced stage fright when asked to give oral presentations. The study further revealed that the respondents associated their unfavourable experience to three causes: 1) fear of making mistakes (65.2%), 2) fear towards the audience (21.7%), and 3) lack of knowledge in oral presentations (13%).

Another recent study that measures students’ attitude towards oral presentations was conducted by Pham et al. ( 2022 ) on 600 second-year, third-year, and fourth-year students at the Faculty of Foreign Languages of Van Lang University in Vietnam. The quantitative study used a survey questionnaire with 38 questions. The study reported that 89.7% of the respondents agree that oral presentation skills are important for their career prospects, and 90.7% of the respondents believe that being able to give good oral presentations is an advantage to students. Additionally, the respondents of the study also acknowledged that oral presentations can help improve communication skills, build confidence, and increase creativity. Despite showing positive understanding towards the importance of oral presentations, 57.1% of the students dread the idea of standing and speaking in front of an audience.