- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

23.1: The Relationship Between Inflation and Unemployment

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 4473

The Phillips Curve

The Phillips curve shows the inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment: as unemployment decreases, inflation increases.

learning objectives

- Review the historical evidence regarding the theory of the Phillips curve

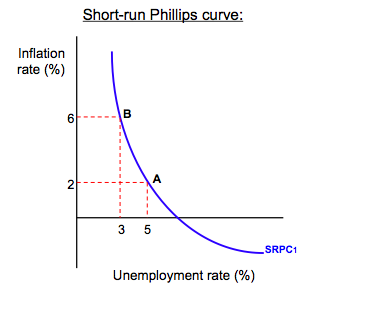

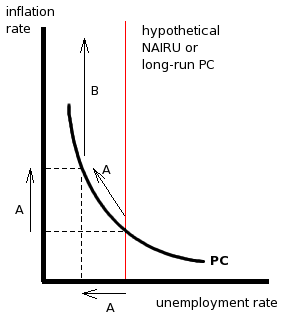

The Phillips curve relates the rate of inflation with the rate of unemployment. The Phillips curve argues that unemployment and inflation are inversely related: as levels of unemployment decrease, inflation increases. The relationship, however, is not linear. Graphically, the short-run Phillips curve traces an L-shape when the unemployment rate is on the x-axis and the inflation rate is on the y-axis.

Theoretical Phillips Curve : The Phillips curve shows the inverse trade-off between inflation and unemployment. As one increases, the other must decrease. In this image, an economy can either experience 3% unemployment at the cost of 6% of inflation, or increase unemployment to 5% to bring down the inflation levels to 2%.

The early idea for the Phillips curve was proposed in 1958 by economist A.W. Phillips. In his original paper, Phillips tracked wage changes and unemployment changes in Great Britain from 1861 to 1957, and found that there was a stable, inverse relationship between wages and unemployment. This correlation between wage changes and unemployment seemed to hold for Great Britain and for other industrial countries. In 1960, economists Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow expanded this work to reflect the relationship between inflation and unemployment. Because wages are the largest components of prices, inflation (rather than wage changes) could be inversely linked to unemployment.

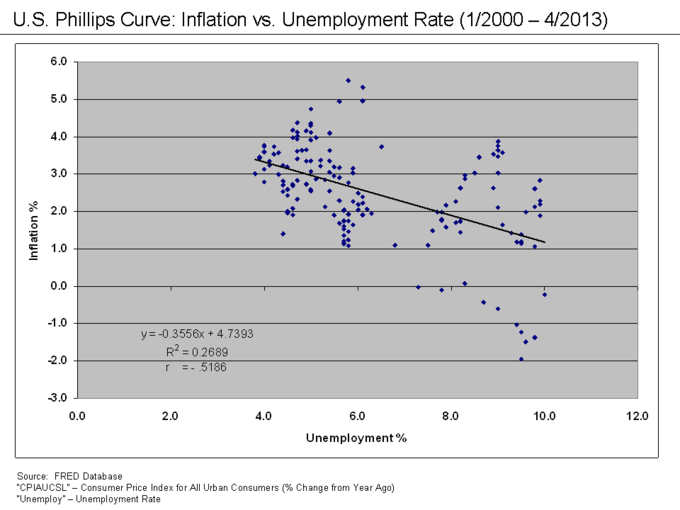

The theory of the Phillips curve seemed stable and predictable. Data from the 1960’s modeled the trade-off between unemployment and inflation fairly well. The Phillips curve offered potential economic policy outcomes: fiscal and monetary policy could be used to achieve full employment at the cost of higher price levels, or to lower inflation at the cost of lowered employment. However, when governments attempted to use the Phillips curve to control unemployment and inflation, the relationship fell apart. Data from the 1970’s and onward did not follow the trend of the classic Phillips curve. For many years, both the rate of inflation and the rate of unemployment were higher than the Phillips curve would have predicted, a phenomenon known as “stagflation. ” Ultimately, the Phillips curve was proved to be unstable, and therefore, not usable for policy purposes.

US Phillips Curve (2000 – 2013) : The data points in this graph span every month from January 2000 until April 2013. They do not form the classic L-shape the short-run Phillips curve would predict. Although it was shown to be stable from the 1860’s until the 1960’s, the Phillips curve relationship became unstable – and unusable for policy-making – in the 1970’s.

The Relationship Between the Phillips Curve and AD-AD

Changes in aggregate demand cause movements along the Phillips curve, all other variables held constant.

- Relate aggregate demand to the Phillips curve

The Phillips Curve Related to Aggregate Demand

The Phillips curve shows the inverse trade-off between rates of inflation and rates of unemployment. If unemployment is high, inflation will be low; if unemployment is low, inflation will be high.

The Phillips curve and aggregate demand share similar components. The Phillips curve is the relationship between inflation, which affects the price level aspect of aggregate demand, and unemployment, which is dependent on the real output portion of aggregate demand. Consequently, it is not far-fetched to say that the Phillips curve and aggregate demand are actually closely related.

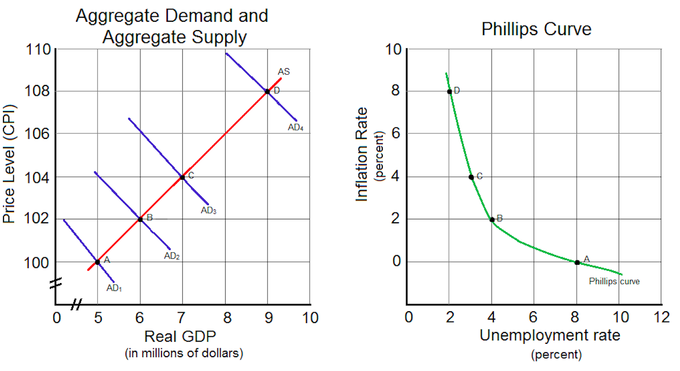

To see the connection more clearly, consider the example illustrated by. Let’s assume that aggregate supply, AS, is stationary, and that aggregate demand starts with the curve, AD 1 . There is an initial equilibrium price level and real GDP output at point A. Now, imagine there are increases in aggregate demand, causing the curve to shift right to curves AD 2 through AD4. As aggregate demand increases, unemployment decreases as more workers are hired, real GDP output increases, and the price level increases; this situation describes a demand-pull inflation scenario.

Phillips Curve and Aggregate Demand : As aggregate demand increases from AD1 to AD4, the price level and real GDP increases. This translates to corresponding movements along the Phillips curve as inflation increases and unemployment decreases.

As more workers are hired, unemployment decreases. Moreover, the price level increases, leading to increases in inflation. These two factors are captured as equivalent movements along the Phillips curve from points A to D. At the initial equilibrium point A in the aggregate demand and supply graph, there is a corresponding inflation rate and unemployment rate represented by point A in the Phillips curve graph. For every new equilibrium point (points B, C, and D) in the aggregate graph, there is a corresponding point in the Phillips curve. This illustrates an important point: changes in aggregate demand cause movements along the Phillips curve.

The Long-Run Phillips Curve

The long-run Phillips curve is a vertical line at the natural rate of unemployment, so inflation and unemployment are unrelated in the long run.

- Examine the NAIRU and its relationship to the long term Phillips curve

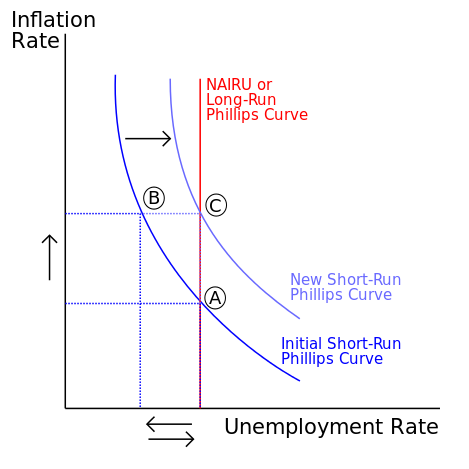

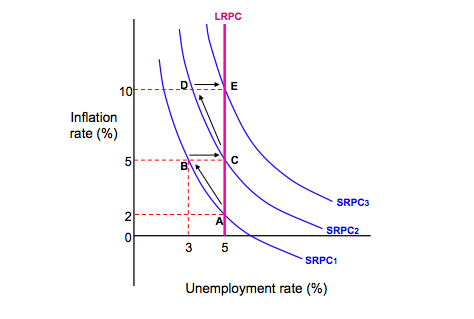

The Phillips curve shows the trade-off between inflation and unemployment, but how accurate is this relationship in the long run? According to economists, there can be no trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run. Decreases in unemployment can lead to increases in inflation, but only in the short run. In the long run, inflation and unemployment are unrelated. Graphically, this means the Phillips curve is vertical at the natural rate of unemployment, or the hypothetical unemployment rate if aggregate production is in the long-run level. Attempts to change unemployment rates only serve to move the economy up and down this vertical line.

Natural Rate Hypothesis

The natural rate of unemployment theory, also known as the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) theory, was developed by economists Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps. According to NAIRU theory, expansionary economic policies will create only temporary decreases in unemployment as the economy will adjust to the natural rate. Moreover, when unemployment is below the natural rate, inflation will accelerate. When unemployment is above the natural rate, inflation will decelerate. When the unemployment rate is equal to the natural rate, inflation is stable, or non-accelerating.

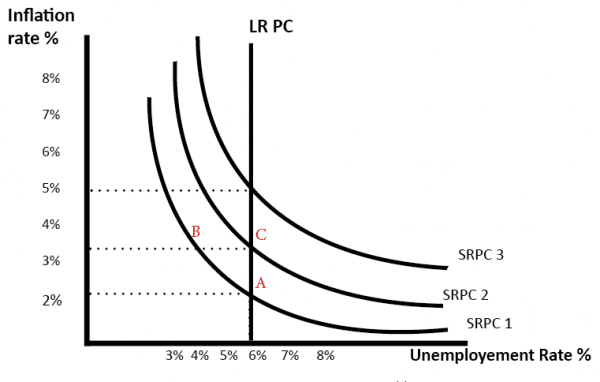

To get a better sense of the long-run Phillips curve, consider the example shown in. Assume the economy starts at point A and has an initial rate of unemployment and inflation rate. If the government decides to pursue expansionary economic policies, inflation will increase as aggregate demand shifts to the right. This is shown as a movement along the short-run Phillips curve, to point B, which is an unstable equilibrium. As aggregate demand increases, more workers will be hired by firms in order to produce more output to meet rising demand, and unemployment will decrease. However, due to the higher inflation, workers’ expectations of future inflation changes, which shifts the short-run Phillips curve to the right, from unstable equilibrium point B to the stable equilibrium point C. At point C, the rate of unemployment has increased back to its natural rate, but inflation remains higher than its initial level.

NAIRU and Phillips Curve : Although the economy starts with an initially low level of inflation at point A, attempts to decrease the unemployment rate are futile and only increase inflation to point C. The unemployment rate cannot fall below the natural rate of unemployment, or NAIRU, without increasing inflation in the long run.

The reason the short-run Phillips curve shifts is due to the changes in inflation expectations. Workers, who are assumed to be completely rational and informed, will recognize their nominal wages have not kept pace with inflation increases (the movement from A to B), so their real wages have been decreased. As such, in the future, they will renegotiate their nominal wages to reflect the higher expected inflation rate, in order to keep their real wages the same. As nominal wages increase, production costs for the supplier increase, which diminishes profits. As profits decline, suppliers will decrease output and employ fewer workers (the movement from B to C). Consequently, an attempt to decrease unemployment at the cost of higher inflation in the short run led to higher inflation and no change in unemployment in the long run.

The NAIRU theory was used to explain the stagflation phenomenon of the 1970’s, when the classic Phillips curve could not. According to the theory, the simultaneously high rates of unemployment and inflation could be explained because workers changed their inflation expectations, shifting the short-run Phillips curve, and increasing the prevailing rate of inflation in the economy. At the same time, unemployment rates were not affected, leading to high inflation and high unemployment.

The Short-Run Phillips Curve

The short-run Phillips curve depicts the inverse trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

- Interpret the short-run Phillips curve

The Phillips curve depicts the relationship between inflation and unemployment rates. The long-run Phillips curve is a vertical line that illustrates that there is no permanent trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run. However, the short-run Phillips curve is roughly L-shaped to reflect the initial inverse relationship between the two variables. As unemployment rates increase, inflation decreases; as unemployment rates decrease, inflation increases.

Short-Run Phillips Curve : The short-run Phillips curve shows that in the short-term there is a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. Contrast it with the long-run Phillips curve (in red), which shows that over the long term, unemployment rate stays more or less steady regardless of inflation rate.

Consider the example shown in. When the unemployment rate is 2%, the corresponding inflation rate is 10%. As unemployment decreases to 1%, the inflation rate increases to 15%. On the other hand, when unemployment increases to 6%, the inflation rate drops to 2%.

Historical application

During the 1960’s, the Phillips curve rose to prominence because it seemed to accurately depict real-world macroeconomics. However, the stagflation of the 1970’s shattered any illusions that the Phillips curve was a stable and predictable policy tool. Nowadays, modern economists reject the idea of a stable Phillips curve, but they agree that there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the short-run. Given a stationary aggregate supply curve, increases in aggregate demand create increases in real output. As output increases, unemployment decreases. With more people employed in the workforce, spending within the economy increases, and demand-pull inflation occurs, raising price levels.

Therefore, the short-run Phillips curve illustrates a real, inverse correlation between inflation and unemployment, but this relationship can only exist in the short run . The idea of a stable trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run has been disproved by economic history.

Relationship Between Expectations and Inflation

There are two theories of expectations (adaptive or rational) that predict how people will react to inflation.

- Distinguish adaptive expectations from rational expectations

The short-run Phillips curve is said to shift because of workers’ future inflation expectations. Yet, how are those expectations formed? There are two theories that explain how individuals predict future events.

Real versus Nominal Quantities

To fully appreciate theories of expectations, it is helpful to review the difference between real and nominal concepts. Anything that is nominal is a stated aspect. In contrast, anything that is real has been adjusted for inflation. To make the distinction clearer, consider this example. Suppose you are opening a savings account at a bank that promises a 5% interest rate. This is the nominal, or stated, interest rate. However, suppose inflation is at 3%. The real interest rate would only be 2% (the nominal 5% minus 3% to adjust for inflation).

The difference between real and nominal extends beyond interest rates. In an earlier atom, the difference between real GDP and nominal GDP was discussed. The distinction also applies to wages, income, and exchange rates, among other values.

Adaptive Expectations

The theory of adaptive expectations states that individuals will form future expectations based on past events. For example, if inflation was lower than expected in the past, individuals will change their expectations and anticipate future inflation to be lower than expected.

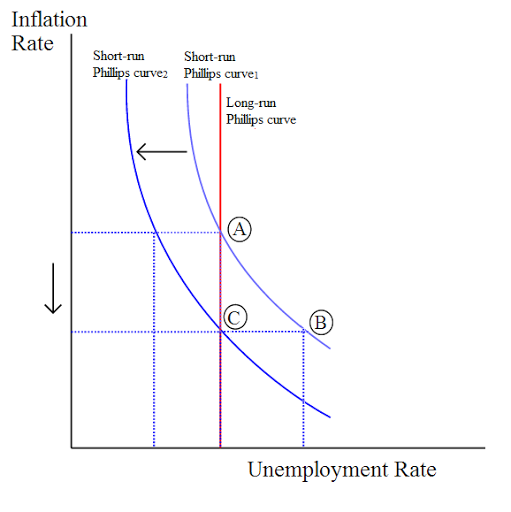

To connect this to the Phillips curve, consider. Assume the economy starts at point A at the natural rate of unemployment with an initial inflation rate of 2%, which has been constant for the past few years. Accordingly, because of the adaptive expectations theory, workers will expect the 2% inflation rate to continue, so they will incorporate this expected increase into future labor bargaining agreements. This way, their nominal wages will keep up with inflation, and their real wages will stay the same.

Expectations and the Phillips Curve : According to adaptive expectations theory, policies designed to lower unemployment will move the economy from point A through point B, a transition period when unemployment is temporarily lowered at the cost of higher inflation. However, eventually, the economy will move back to the natural rate of unemployment at point C, which produces a net effect of only increasing the inflation rate.According to rational expectations theory, policies designed to lower unemployment will move the economy directly from point A to point C. The transition at point B does not exist as workers are able to anticipate increased inflation and adjust their wage demands accordingly.

Now assume that the government wants to lower the unemployment rate. To do so, it engages in expansionary economic activities and increases aggregate demand. As aggregate demand increases, inflation increases. Because of the higher inflation, the real wages workers receive have decreased. For example, assume each worker receives $100, plus the 2% inflation adjustment. Each worker will make $102 in nominal wages, but $100 in real wages. Now, if the inflation level has risen to 6%. Workers will make $102 in nominal wages, but this is only $96.23 in real wages.

Although the workers’ real purchasing power declines, employers are now able to hire labor for a cheaper real cost. Consequently, employers hire more workers to produce more output, lowering the unemployment rate and increasing real GDP. On, the economy moves from point A to point B.

However, workers eventually realize that inflation has grown faster than expected, their nominal wages have not kept pace, and their real wages have been diminished. They demand a 4% increase in wages to increase their real purchasing power to previous levels, which raises labor costs for employers. As labor costs increase, profits decrease, and some workers are let go, increasing the unemployment rate. Graphically, the economy moves from point B to point C.

This example highlights how the theory of adaptive expectations predicts that there are no long-run trade-offs between unemployment and inflation. In the short run, it is possible to lower unemployment at the cost of higher inflation, but, eventually, worker expectations will catch up, and the economy will correct itself to the natural rate of unemployment with higher inflation.

Rational Expectations

The theory of rational expectations states that individuals will form future expectations based on all available information, with the result that future predictions will be very close to the market equilibrium. For example, assume that inflation was lower than expected in the past. Individuals will take this past information and current information, such as the current inflation rate and current economic policies, to predict future inflation rates.

As an example of how this applies to the Phillips curve, consider again. Assume the economy starts at point A, with an initial inflation rate of 2% and the natural rate of unemployment. However, under rational expectations theory, workers are intelligent and fully aware of past and present economic variables and change their expectations accordingly. They will be able to anticipate increases in aggregate demand and the accompanying increases in inflation. As such, they will raise their nominal wage demands to match the forecasted inflation, and they will not have an adjustment period when their real wages are lower than their nominal wages. Graphically, they will move seamlessly from point A to point C, without transitioning to point B.

In essence, rational expectations theory predicts that attempts to change the unemployment rate will be automatically undermined by rational workers. They can act rationally to protect their interests, which cancels out the intended economic policy effects. Efforts to lower unemployment only raise inflation.

Shifting the Phillips Curve with a Supply Shock

Aggregate supply shocks, such as increases in the costs of resources, can cause the Phillips curve to shift.

- Give examples of aggregate supply shock that shift the Phillips curve

The Phillips curve shows the relationship between inflation and unemployment. In the short-run, inflation and unemployment are inversely related; as one quantity increases, the other decreases. In the long-run, there is no trade-off. In the 1960’s, economists believed that the short-run Phillips curve was stable. By the 1970’s, economic events dashed the idea of a predictable Phillips curve. What could have happened in the 1970’s to ruin an entire theory? Stagflation caused by a aggregate supply shock.

Stagflation and Aggregate Supply Shocks

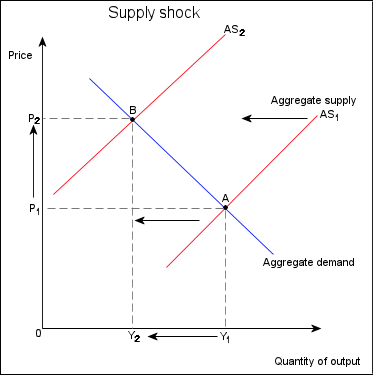

Stagflation is a combination of the words “stagnant” and “inflation,” which are the characteristics of an economy experiencing stagflation: stagnating economic growth and high unemployment with simultaneously high inflation. The stagflation of the 1970’s was caused by a series of aggregate supply shocks. In this case, huge increases in oil prices by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) created a severe negative supply shock. The increased oil prices represented greatly increased resource prices for other goods, which decreased aggregate supply and shifted the curve to the left. As aggregate supply decreased, real GDP output decreased, which increased unemployment, and price level increased; in other words, the shift in aggregate supply created cost-push inflation.

Aggregate Supply Shock : In this example of a negative supply shock, aggregate supply decreases and shifts to the left. The resulting decrease in output and increase in inflation can cause the situation known as stagflation.

Shifting the Phillips Curve

The aggregate supply shocks caused by the rising price of oil created simultaneously high unemployment and high inflation. At the time, the dominant school of economic thought believed inflation and unemployment to be mutually exclusive; it was not possible to have high levels of both within an economy. Consequently, the Phillips curve could not model this situation. For high levels of unemployment, there were now corresponding levels of inflation that were higher than the Phillips curve predicted; the Phillips curve had shifted upwards and to the right. Thus, the Phillips curve no longer represented a predictable trade-off between unemployment and inflation.

Disinflation

Disinflation is a decline in the rate of inflation, and can be caused by declines in the money supply or recessions in the business cycle.

- Identify situations with disinflation

Inflation is the persistent rise in the general price level of goods and services. Disinflation is a decline in the rate of inflation; it is a slowdown in the rise in price level. As an example, assume inflation in an economy grows from 2% to 6% in Year 1, for a growth rate of four percentage points. In Year 2, inflation grows from 6% to 8%, which is a growth rate of only two percentage points. The economy is experiencing disinflation because inflation did not increase as quickly in Year 2 as it did in Year 1, but the general price level is still rising. Disinflation is not to be confused with deflation, which is a decrease in the general price level.

Disinflation can be caused by decreases in the supply of money available in an economy. It can also be caused by contractions in the business cycle, otherwise known as recessions. The Phillips curve can illustrate this last point more closely. Consider an economy initially at point A on the long-run Phillips curve in. Suppose that during a recession, the rate that aggregate demand increases relative to increases in aggregate supply declines. This reduces price levels, which diminishes supplier profits. As profits decline, employers lay off employees, and unemployment rises, which moves the economy from point A to point B on the graph. Eventually, though, firms and workers adjust their inflation expectations, and firms experience profits once again. As profits increase, employment also increases, returning the unemployment rate to the natural rate as the economy moves from point B to point C. The expected rate of inflation has also decreased due to different inflation expectations, resulting in a shift of the short-run Phillips curve.

Disinflation : Disinflation can be illustrated as movements along the short-run and long-run Phillips curves.

Inflation vs. Deflation vs. Disinflation

To illustrate the differences between inflation, deflation, and disinflation, consider the following example. Assume the following annual price levels as compared to the prices in year 1:

- Year 1: 100% of Year 1 prices

- Year 2: 104% of Year 1 prices

- Year 3: 106% of Year 1 prices

- Year 4: 107% of Year 1 prices

- Year 5: 105% of Year 1 prices

As the economy moves through Year 1 to Year 4, there is a continued growth in the price level. This is an example of inflation; the price level is continually rising. However, between Year 2 and Year 4, the rise in price levels slows down. Between Year 2 and Year 3, the price level only increases by two percentage points, which is lower than the four percentage point increase between Years 1 and 2. The trend continues between Years 3 and 4, where there is only a one percentage point increase. This is an example of disinflation; the overall price level is rising, but it is doing so at a slower rate.

Between Years 4 and 5, the price level does not increase, but decreases by two percentage points. This is an example of deflation; the price rise of previous years has reversed itself.

- The relationship between inflation rates and unemployment rates is inverse. Graphically, this means the short-run Phillips curve is L-shaped.

- A.W. Phillips published his observations about the inverse correlation between wage changes and unemployment in Great Britain in 1958. This relationship was found to hold true for other industrial countries, as well.

- From 1861 until the late 1960’s, the Phillips curve predicted rates of inflation and rates of unemployment. However, from the 1970’s and 1980’s onward, rates of inflation and unemployment differed from the Phillips curve’s prediction. The relationship between the two variables became unstable.

- Aggregate demand and the Phillips curve share similar components. The rate of unemployment and rate of inflation found in the Phillips curve correspond to the real GDP and price level of aggregate demand.

- Changes in aggregate demand translate as movements along the Phillips curve.

- If there is an increase in aggregate demand, such as what is experienced during demand-pull inflation, there will be an upward movement along the Phillips curve. As aggregate demand increases, real GDP and price level increase, which lowers the unemployment rate and increases inflation.

- The natural rate of unemployment is the hypothetical level of unemployment the economy would experience if aggregate production were in the long-run state.

- The natural rate hypothesis, or the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) theory, predicts that inflation is stable only when unemployment is equal to the natural rate of unemployment. If unemployment is below (above) its natural rate, inflation will accelerate (decelerate).

- Expansionary efforts to decrease unemployment below the natural rate of unemployment will result in inflation. This changes the inflation expectations of workers, who will adjust their nominal wages to meet these expectations in the future. This leads to shifts in the short-run Phillips curve.

- The natural rate hypothesis was used to give reasons for stagflation, a phenomenon that the classic Phillips curve could not explain.

- The long-run Phillips curve is a vertical line at the natural rate of unemployment, but the short-run Phillips curve is roughly L-shaped.

- The inverse relationship shown by the short-run Phillips curve only exists in the short-run; there is no trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run.

- Economic events of the 1970’s disproved the idea of a permanently stable trade-off between unemployment and inflation.

- Nominal quantities are simply stated values. Real quantities are nominal ones that have been adjusted for inflation.

- Adaptive expectations theory says that people use past information as the best predictor of future events. If inflation was higher than normal in the past, people will expect it to be higher than anticipated in the future.

- Rational expectations theory says that people use all available information, past and current, to predict future events. If inflation was higher than normal in the past, people will take that into consideration, along with current economic indicators, to anticipate its future performance.

- According to adaptive expectations, attempts to reduce unemployment will result in temporary adjustments along the short-run Phillips curve, but will revert to the natural rate of unemployment. According to rational expectations, attempts to reduce unemployment will only result in higher inflation.

- In the 1970’s soaring oil prices increased resource costs for suppliers, which decreased aggregate supply. The resulting cost-push inflation situation led to high unemployment and high inflation ( stagflation ), which shifted the Phillips curve upwards and to the right.

- Stagflation is a situation where economic growth is slow (reducing employment levels) but inflation is high.

- The Phillips curve was thought to represent a fixed and stable trade-off between unemployment and inflation, but the supply shocks of the 1970’s caused the Phillips curve to shift. This ruined its reputation as a predictable relationship.

- Disinflation is not the same as deflation, when inflation drops below zero.

- During periods of disinflation, the general price level is still increasing, but it is occurring slower than before.

- The short-run and long-run Phillips curve may be used to illustrate disinflation.

- Phillips curve : A graph that shows the inverse relationship between the rate of unemployment and the rate of inflation in an economy.

- stagflation : Inflation accompanied by stagnant growth, unemployment, or recession.

- aggregate demand : The the total demand for final goods and services in the economy at a given time and price level.

- Natural Rate of Unemployment : The hypothetical unemployment rate consistent with aggregate production being at the long-run level.

- non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment : (NAIRU); theory that describes how the short-run Phillips curve shifts in the long run as expectations change.

- adaptive expectations theory : A hypothesized process by which people form their expectations about what will happen in the future based on what has happened in the past.

- rational expectations theory : A hypothesized process by which people form their expectations about what will happen in the future based on all relevant information.

- supply shock : An event that suddenly changes the price of a commodity or service. It may be caused by a sudden increase or decrease in the supply of a particular good.

- disinflation : A decrease in the inflation rate.

- inflation : An increase in the general level of prices or in the cost of living.

- deflation : A decrease in the general price level, that is, in the nominal cost of goods and services.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- Curation and Revision. Provided by : Boundless.com. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- Q18-Macro (Is there a long-term trade-off between inflation and unemployment?). Provided by : ib-econ Wikispace. Located at : ib-econ.wikispaces.com/Q18-M...employment%3F) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phillips curve. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillips_curve . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phillips Curve. Provided by : sjhsrc Wikispace. Located at : sjhsrc.wikispaces.com/Phillips+Curve . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- stagflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/stagflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//economics/...phillips-curve . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- U.S.nPhillips Curve 2000 to 2013. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:U....00_to_2013.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by : Wikispaces. Located at : ib-econ.wikispaces.com/Q18-M...unemployment?) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- aggregate demand. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/aggregate%20demand . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : http://www.boundless.com . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Milton Friedman. Provided by : econwikis-mborg Wikispace. Located at : econwikis-mborg.wikispaces.com/Milton+Friedman . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Natural rate of unemployment. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural...f_unemployment . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Natural Rate of Unemployment. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural...20Unemployment . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//economics/...f-unemployment . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- NAIRU-SR-and-LR. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:NAIRU-SR-and-LR.svg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Unit V. Provided by : ap-macroeconomics Wikispace. Located at : ap-macroeconomics.wikispaces.com/Unit+V . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phillips curve. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillips_curve . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by : Wikispaces. Located at : ib-econ.wikispaces.com/Q18-Macro+(Is+there+a+long-term+trade-off+between+inflation+and+unemployment?) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- PhilCurve.png. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PhilCurve.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Adaptive expectations. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Adaptive_expectations . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Rational expectations. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Rational_expectations . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Real versus nominal value (economics). Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_ve...ue_(economics) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- adaptive expectations theory. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/adaptiv...tions%20theory . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//economics/...tations-theory . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Supply shock. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Supply_shock . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phillips curve. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillip...%23Stagflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stagflation. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Stagflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- supply shock. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/supply%20shock . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- stagflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/stagflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Economics supply shock. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ec...pply_shock.png . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Disinflation. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Disinflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Long-Run AS. Provided by : mchenry Wikispace. Located at : mchenry.wikispaces.com/Long-Run+AS . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- deflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/deflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- inflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/inflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- disinflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/disinflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- U.S.nPhillips Curve 2000 to 2013. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:U....00_to_2013.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by : lh5.googleusercontent.com/-B...inflation2.png. Located at : https://lh5.googleusercontent.com/-Bc5Yt-QMGXA/Uo3sjZ7SgxI/AAAAAAAAAXQ/1MksRdza_rA/s512/Phillipscurve_disinflation2.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Natural Unemployment Rate

Understanding Natural Unemployment

- Inflation and Unemployment

The Bottom Line

What is the natural unemployment rate.

Julia Kagan is a financial/consumer journalist and former senior editor, personal finance, of Investopedia.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Julia_Kagan_BW_web_ready-4-4e918378cc90496d84ee23642957234b.jpg)

The natural unemployment rate is the minimum unemployment rate resulting from real or voluntary economic forces. Natural unemployment reflects workers moving from job to job, the number of unemployed replaced by technology, or those lacking the skills to gain employment.

Key Takeaways

- The natural unemployment rate is the minimum unemployment rate resulting from real or voluntary economic forces.

- It represents the number of people unemployed due to the structure of the labor force, such as those replaced by technology or those who lack the skills to get hired.

- Natural unemployment is commonplace in the labor market as workers flow to and from jobs or companies.

- Unemployment is not considered natural if it is cyclical, institutional, or policy-based unemployment.

- Because of natural unemployment, 100% full employment is unattainable in an economy.

Investopedia / Theresa Chiechi

The term “ full employment ” is often a target to achieve when the U.S. economy is performing well. The term is a misnomer because there are always workers looking for employment, including new college graduates or those displaced by technological advances. There is always movement of labor throughout the economy that represents natural unemployment.

Unemployment is not considered natural if it is cyclical, institutional, or policy-based unemployment. An economic crash or steep recession might increase the natural unemployment rate if workers lose the skills necessary to find full-time work or if certain businesses close and are unable to reopen due to excessive loss of revenue. Economists call this effect “ hysteresis .”

Important contributors to the theory of natural unemployment include Milton Friedman , Edmund Phelps , and Friedrich Hayek , all Nobel prize recipients. The works of Friedman and Phelps were instrumental in developing the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU).

Natural unemployment can occur from both voluntary and involuntary factors. Hysteresis often occurs following extreme or prolonged economic events such as a recession, where the unemployment rate may continue to increase despite economic growth.

Causes of Natural Unemployment

Economists commonly held that if unemployment existed, it was due to a lack of demand for labor or workers and the economy would need to be stimulated through fiscal or monetary measures. However, history reveals the natural flow of workers to and from companies even during robust economic periods.

Full Employment

Full employment means 100% of the workforce is employed. History shows that this is unattainable as workers move from job to job. A zero unemployment rate is also undesired as it requires an inflexible labor market, where workers cannot quit their current job or leave to find a better one.

According to the general equilibrium model of economics, natural unemployment is equal to the level of unemployment in a labor market at perfect equilibrium. This is the difference between workers who want a job at the current wage rate and those willing and able to perform such work. Under this definition of natural unemployment, it is possible for institutional factors, such as the minimum wage or high degrees of unionization, to increase the natural rate over the long run.

Effects of Inflation on Unemployment

John Maynard Keynes wrote The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in 1936, leading many economists to believe there is a direct relationship between the level of unemployment in an economy and the level of inflation.

This direct relationship was formally codified in the Phillips curve , which showed that unemployment moved in the opposite direction of inflation . If the economy was to be fully employed, there must be inflation, and conversely, with periods of low inflation, unemployment must increase or persist.

The Phillips curve fell out of favor after the great stagflation of the 1970s. During stagflation, unemployment and inflation both rise , questioning the implied correlation between strong economic activity and inflation, or between deflation and unemployment.

What Is Natural vs. Cyclical Unemployment?

The cyclical unemployment rate is the difference between the natural unemployment rate and the current rate of unemployment as defined by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Why Is the Natural Unemployment Rate Significant?

The natural rate of unemployment is considered the lowest acceptable level that a healthy economy can sustain without creating inflation.

How Does a Recovering Economy Impact the Natural Unemployment Rate?

The natural rate of unemployment typically rises after a downturn in the economy or a recession as workers become more confident that they can move from job to job.

The natural unemployment rate is the minimum unemployment rate stemming from real or voluntary economic forces. It is common in the labor market as workers flow to and from jobs or companies, and because of natural unemployment, full employment is unattainable in an economy. Unemployment is not considered natural if it is cyclical, institutional, or policy-based unemployment.

- What Is Unemployment? Causes, Types, and Measurement 1 of 43

- What Does Termination of Employment Mean? 2 of 43

- What Is an Unemployment Claim? 3 of 43

- Unemployment Compensation: Definition, Requirements, and Example 4 of 43

- What Is Severance Pay? Definition and Why It's Offered 5 of 43

- The Layoff Payoff: A Severance Package 6 of 43

- 7 Considerations When You Negotiate Severance 7 of 43

- 7 Effective Ways to Prepare for a Layoff 8 of 43

- Unemployment Insurance (UI): How It Works, Requirements, and Funding 9 of 43

- How to Apply for Unemployment Insurance Now 10 of 43

- Who Doesn't Get Unemployment Insurance? 11 of 43

- What Was Private Unemployment Insurance? 12 of 43

- How to Pay Your Bills When You Lose Your Job 13 of 43

- Can I Access Money in My 401(k) If I Am Unemployed? 14 of 43

- All About COBRA Health Insurance 15 of 43

- Medical Debt: What to Do When You Can’t Pay 16 of 43

- Help, My Unemployment Benefits Are Running Out 17 of 43

- What Is the Unemployment Rate? Rates by State 18 of 43

- How Is the U.S. Monthly Unemployment Rate Calculated? 19 of 43

- Unemployment Rates: The Highest and Lowest Worldwide 20 of 43

- What You Need to Know About the Employment Report 21 of 43

- U-3 vs. U-6 Unemployment Rate: What's the Difference? 22 of 43

- Participation Rate vs. Unemployment Rate: What's the Difference? 23 of 43

- What the Unemployment Rate Does Not Tell Us 24 of 43

- How the Unemployment Rate Affects Everybody 25 of 43

- How Inflation and Unemployment Are Related 26 of 43

- How the Minimum Wage Impacts Unemployment 27 of 43

- The Cost of Unemployment to the Economy 28 of 43

- Okun’s Law: Economic Growth and Unemployment 29 of 43

- What Can Policymakers Do To Decrease Cyclical Unemployment? 30 of 43

- What Happens When Inflation and Unemployment Are Positively Correlated? 31 of 43

- The Downside of Low Unemployment 32 of 43

- Frictional vs. Structural Unemployment: What’s the Difference? 33 of 43

- Structural vs. Cyclical Unemployment: What's the Difference? 34 of 43

- Cyclical Unemployment: Definition, Cause, Types, and Example 35 of 43

- Disguised Unemployment: Definition and Different Types 36 of 43

- Employment-to-Population Ratio: Definition and What It Measures 37 of 43

- Frictional Unemployment: Definition, Causes, and Quit Rate Explained 38 of 43

- Full Employment: Definition, Types, and Examples 39 of 43

- Labor Force Participation Rate: Purpose, Formula, and Trends 40 of 43

- Labor Market Explained: Theories and Who Is Included 41 of 43

- What Is the Natural Unemployment Rate? 42 of 43

- Structural Unemployment: Definition, Causes, and Examples 43 of 43

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/job-hunt-game-5bfc2d3e4cedfd0026c16b2d.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

The Natural Rate of Unemployment

- Definition: The natural rate of unemployment is the rate of unemployment when the labour market is in equilibrium. It is unemployment caused by structural (supply-side) factors. (e.g. mismatched skills)

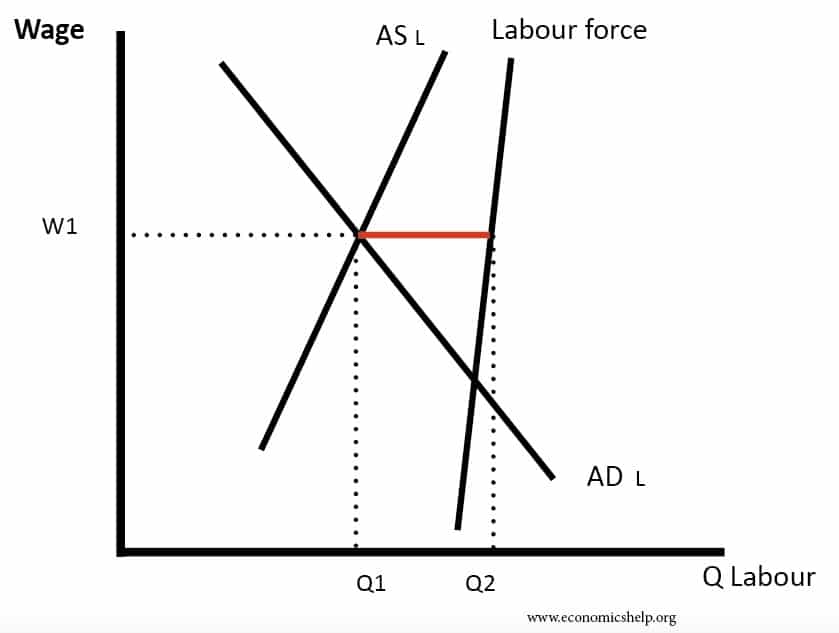

Diagram showing the natural rate of unemployment

- The natural rate of unemployment is the difference between those who would like a job at the current wage rate – and those who are willing and able to take a job. In the above diagram, it is the level (Q2-Q1)

- Frictional unemployment

- Structural unemployment . For example, a worker who is not able to get a job because he doesn’t have the right skills

- The natural rate of unemployment is unemployment caused by supply-side factors rather than demand side factors

What Determines the Natural Rate of Unemployment?

Milton Freidman argued the natural rate of unemployment would be determined by institutional factors such as.

- Availability of job information . A factor in determining frictional unemployment and how quickly the unemployed find a job.

- The level of benefits . Generous benefits may discourage workers from taking jobs at the existing wage rate.

- Skills and education. The quality of education and retraining schemes will influence the level of occupational mobilities.

- The degree of labour mobility. See: labour mobility

- Flexibility of the labour market E.g. powerful trades unions may be able to restrict the supply of labour to certain labour markets

- Hysteresis . A rise in unemployment caused by a recession may cause the natural rate of unemployment to increase. This is because when workers are unemployed for a time period they become deskilled and demotivated and are less able to get new jobs.

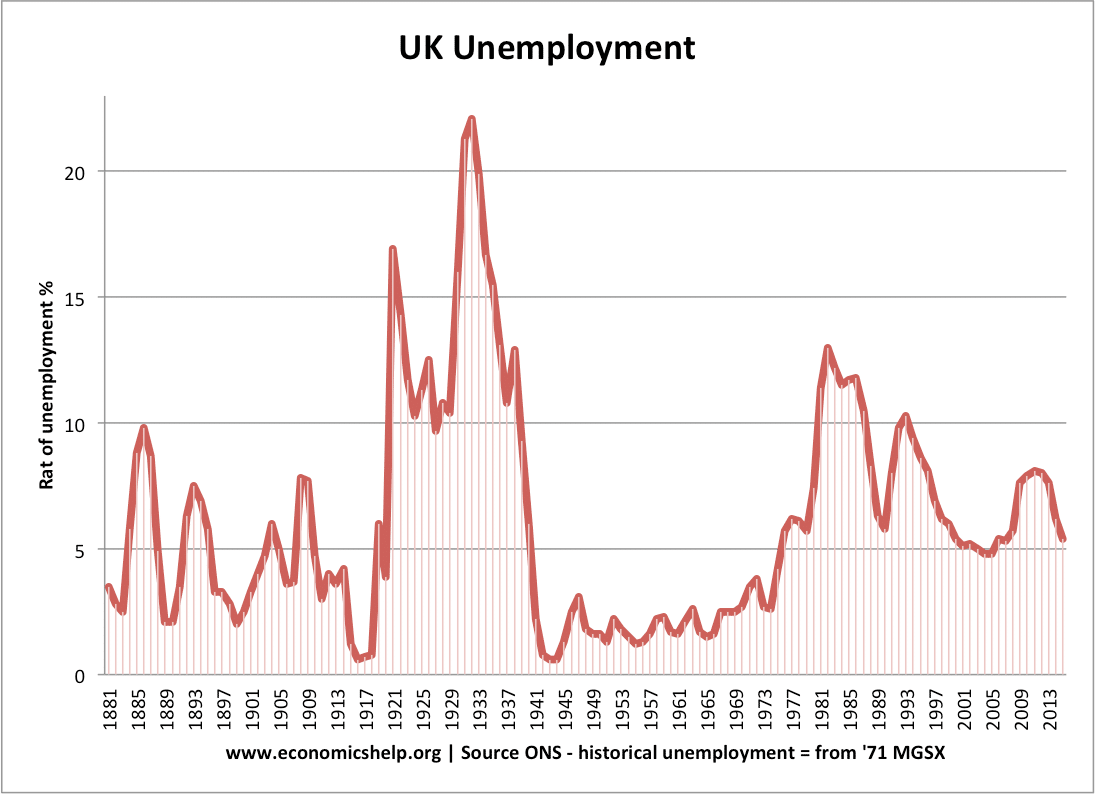

Explaining Changing Natural Rates of Unemployment

In the post-war period, structural unemployment was very low. During the 1980s, the natural rate of unemployment rose, due to rapid deindustrialisation and a rise in geographical and structural unemployment.

Since 2005, the natural rate of unemployment has fallen.

- Increased labour market flexibility, e.g. trade unions less powerful.

- Privatisation has helped increased competitiveness of industry, leading to more flexible labour markets.

- Rise in self-employment and gig economy, have created new types of jobs.

- Increased monopsony power of employers, who have kept wage growth low, enabling firms to employ more workers.

- Harder to claim unemployment benefits.

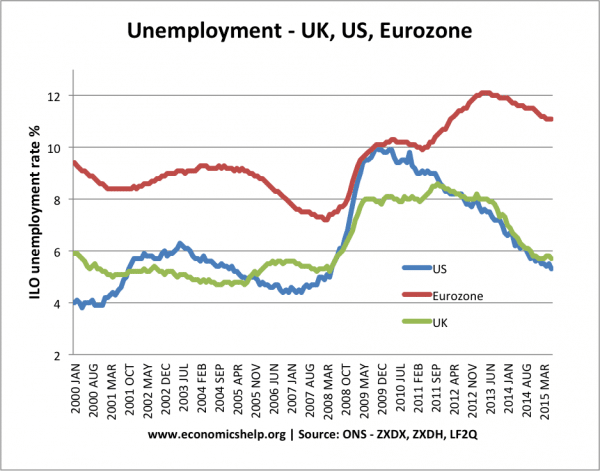

Natural Rate of Unemployment in EU

Even during the period of economic growth 2000-2007, unemployment in Eurozone is higher than US and UK. This suggests the Eurozone has a higher natural rate of unemployment.

- Rigidity in EU labour markets e.g. minimum wages and the maximum working week

- Restrictions on closing factories and mandatory severance pay for workers made unemployed, and this makes firms more reluctant to set up in these countries.

- Higher degrees of unionisation resulting in wage rigidity.

- Generous benefits which lessen the pain of unemployment.

- Hysteresis effects . The cyclical recessions of the 1970s and 1980s had long-lasting effects resulting in more unemployment. However, this does not appear to have affected the UK

- Growing competition from Asian countries, lead to structural unemployment from increased job competition.

During 2012-14, the higher unemployment was partly due to lower rates of economic growth – caused by austerity, and deflationary pressures of the Eurozone single currency.

Reducing the natural rate of unemployment

To reduce the natural rate of unemployment, we need to implement supply-side policies, such as:

- Better education and training to reduce occupational immobilities.

- Making it easier for workers and firms to relocated, e.g. more flexible housing market and greater supply in areas of high job demand.

- Making labour markets more flexible, e.g. reducing minimum wages and trade unions.

- Easier to hire and fire workers.

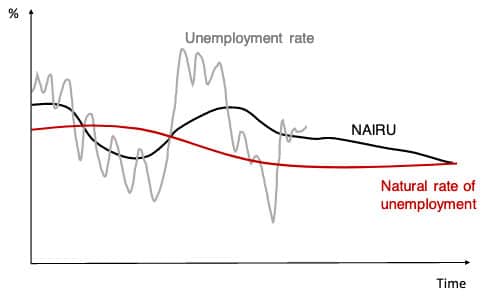

NAIRU and Non-Accelerating Rate of Unemployment

- A very similar concept to the natural rate of unemployment is the NAIRU – the non-accelerating rate of unemployment.

- This is the rate of unemployment consistent with a stable rate of inflation. If you try to reduce unemployment by increasing aggregate demand, then you will get a higher rate of inflation, and the fall in unemployment will prove temporary.

NAIRU explained

- If there is an increase in AD, firms pay higher wages to workers in order to increase in output, this increase in nominal wages encourage workers to supply more labour and therefore unemployment falls.

- However, the increase in AD also causes inflation to increase and therefore real wages do not actually increased but remain the same. Later workers realise that the increase in wages was only nominal and not a real increase.

- Therefore they no longer work overtime. Therefore the supply of labour falls, and unemployment returns to its original or Natural rate of unemployment. It is only possible to reduce unemployment by causing an increase in the rate of inflation. Therefore the natural rate is also known as the NAIRU (non accelerating rate of unemployment.

- This model assumes workers do not correctly predict the rate of inflation but have adaptive expectations .

- Some economists argue workers will correctly predict higher AD causes higher inflation and therefore there will not be even a short term fall in unemployment; this is known as rational expectations .

Example of NAIRU

- In the above example, the natural rate of unemployment is 6%. If you try to reduce unemployment through increased demand, we get a temporary fall in unemployment, but higher inflation. (point A)

- However, this fall in unemployment is unsustainable and the short-run Phillips Curve shifts to SRPC2, and we move to (point C) and unemployment of 6%.

- Causes of Unemployment

- Voluntary unemployment

- Essay on: Natural Rate of Unemployment

The Pandemic's Impact on Unemployment and Labor Force Participation Trends

Following early 2020 responses to the pandemic, labor force participation declined dramatically and has remained below its 2019 level, whereas the unemployment rate recovered briskly. We estimate the trend of labor force participation and unemployment and find a substantial impact of the pandemic on estimates of trend. It turns out that levels of labor force participation and unemployment in 2021 were approaching their estimated trends. A return to 2019 levels would then represent a tight labor market, especially relative to long-run demographic trends that suggest further declines in the participation rate.

At the end of 2019, the labor market was hotter than it had been in years. Unemployment was at a historic low, and participation in the labor market was finally increasing after a prolonged decline. That tight labor market came to an abrupt halt with the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020.

Now, two years later, the labor market has mostly recovered from the depths of the pandemic recession. The unemployment rate is close to pre-pandemic lows, and job openings are at record highs. Yet, participation and employment rates have remained persistently below pre-pandemic levels. This suggests the possibility that the pandemic has permanently reduced participation in the economy and that current participation rates reflect a new normal. In this article, we explore how the pandemic has affected labor markets and whether a new normal is emerging.

What Is "Normal"?

One way to define the normal level of a variable is to estimate its trend and compare the observed data with the estimated trend values. Constructing a trend essentially means drawing a smooth line through the variations in the actual data.

But this means that constructing the trend for a point in time typically involves considering what happened both before and after that point in time. Thus, constructing the trend at the end of a sample is especially hard, since we do not yet know how the data will evolve.

We construct trends for three aggregate labor market ratios — the labor force participation (LFP) rate, the unemployment rate and the employment-population ratio (EPOP) — using methods described in our 2019 article " Projecting Unemployment and Demographic Trends ."

First, we estimate statistical models for LFP and unemployment rates of demographic groups defined by age, gender and education. For each gender and education, we decompose its unemployment and LFP into cyclical components common to all age groups and smooth local trends for age and cohort effects.

Second, we aggregate trends from the estimates of the group-specific trends. Specifically, we construct the trend for the aggregate LFP rate as the population-share-weighted sum of the corresponding estimated trends for demographic groups. We construct the aggregate unemployment rate and EPOP trends from the group-specific LFP and unemployment trends and the groups' population shares.

In our previous work, we estimated the trends for the unemployment rate and LFP rate of a gender-education group separately using maximum likelihood methods. The estimates reported in this article are based on the joint estimation of LFP and unemployment rate trends using Bayesian methods.

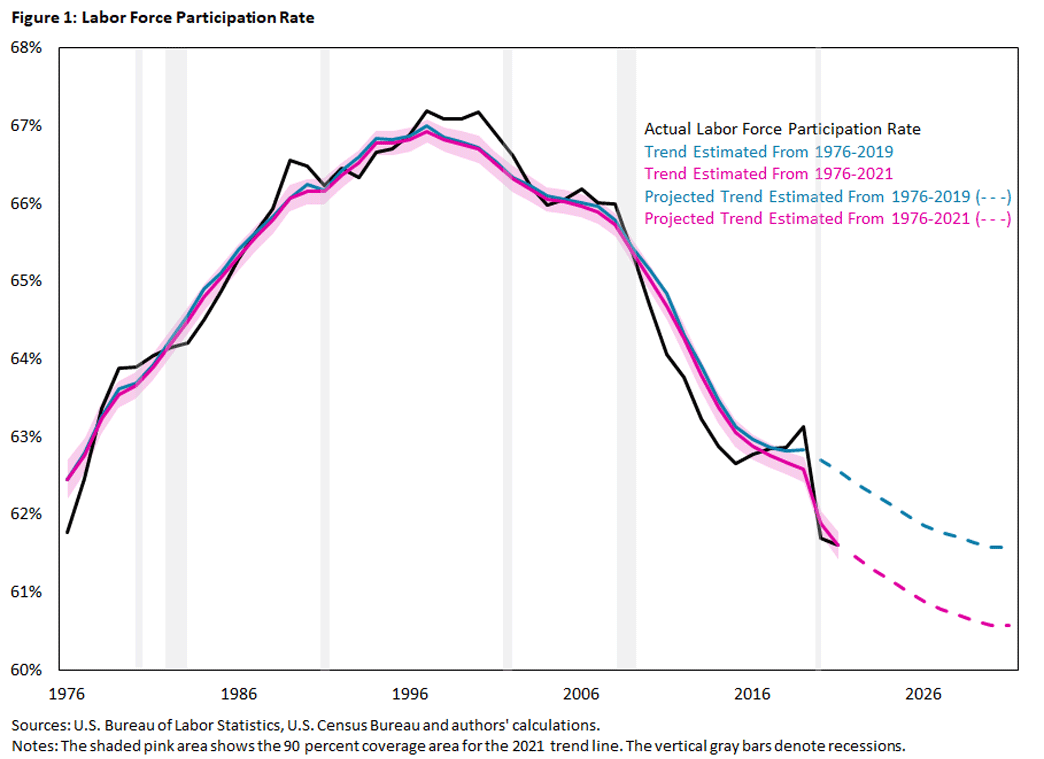

We separately estimate the trends using data from 1976 to 2019 (pre-pandemic) and from 1976 to 2021 (including the pandemic period). Figures 1, 2 and 3 display annual averages for the three aggregate labor market ratios — the LFP rate, the unemployment rate and EPOP, respectively — from 1976 to 2021.

In each figure, the solid black line denotes the observed values, and the blue and pink lines denote the estimated trend using data from 1976 up to and including 2019 and 2021, respectively. The estimated trends are subject to uncertainty, and the plotted trends represent the median estimate of the trend.

For the estimates based on data up to 2021, we also include the 90 percent coverage area shown as the shaded pink area. According to the statistical model, there is a 90 percent probability that the trend is contained in the coverage area. The blue and pink dotted lines represent our projections on how the labor market ratios will evolve until 2031, again based on the estimated trend up to and including 2019 and 2021. The shaded gray vertical areas highlight recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Pre-Pandemic Trends: 1976-2019

We start with the pre-pandemic trends for the LFP rate and unemployment rate estimated for data from 1976 through 2019. After a long recovery from the 2007-09 recession, the LFP rate was 63.1 percent in 2019 (slightly above the estimated trend value of 62.8 percent), and the unemployment rate was 3.7 percent (noticeably below its estimated trend value of 4.7 percent).

The LFP rate being above trend and the unemployment rate being below trend reflects the characterization of the 2019 labor market as "hot." But note that even though the LFP rate exceeded its trend value in 2019, it was still lower than during the 2007-09 period. This difference is accounted for by the declining trend in the LFP rate.

As noted in our 2019 article , LFP rates and unemployment rates differ systematically across demographic groups. Participation rates tend to be higher for younger, more-educated workers and for men. Unemployment rates tend to be lower for men and for the older and more-educated population.

Thus, changes in the population composition over time — that is, the relative size of demographic groups — will affect the aggregate LFP and unemployment rates, in addition to changes in the LFP and unemployment rate trends of the demographic groups.

As also noted in our 2019 article, the hump-shaped trend of the aggregate LFP rate reflects a variety of forces:

- Prior to 1990, the aggregate LFP rate was boosted by an upward trend in the LFP rate of women. But after 1990, the LFP rate of women began declining. Combining this with declining trend LFP rates for other demographic groups has reduced the aggregate LFP rate.

- Changes in the age distribution had a limited impact prior to 2005, but the aging population since then has lowered the aggregate LFP rate substantially.

- Increasing educational attainment has contributed positively to aggregate LFP throughout the period.

The steady decline of the unemployment rate trend reflects mostly the contributions from an older and more-educated population and, to some extent, a decline in the trend unemployment rates of demographic groups.

Pre-Pandemic Expectations of Future LFP and Unemployment Trends

Our statistical model of smooth local trends for the LFP and unemployment rates of demographic groups has the property that the best forecast for future trend values of demographic groups is their last estimated trend value. Thus, the model will only predict a change in the trend of aggregate ratios if the population shares of its constituent groups are changing.

We combine the U.S. Census Bureau population forecasts for the gender-age groups with an estimated statistical model of education shares for gender-age groups to forecast population shares of our demographic groups from 2020 to 2031 (the dotted blue lines in Figures 1 and 2).

As we can see, the changing demographics alone imply further reductions of 1 percentage point and 0.2 percentage points in the trend LFP rate and unemployment rate, respectively. This projection is driven by the forecasted aging of the population, which is only partially offset by the forecasted higher educational attainment.

Based on data up to 2019, the same aggregate LFP rates in 2021 as in 2019 would have represented a substantial cyclical deviation upward from the pre-pandemic trends.

It is notable that the unemployment rate is much more volatile relative to its trend than the LFP rate is. In other words, cyclical deviations from trend are much more pronounced for the unemployment rate than for the LFP rate.

In fact, in our estimation, the behavior of the unemployment rate determines the common cyclical component of both the unemployment rate and the LFP rate. Whereas the unemployment rate spikes in recessions, the LFP rate response is more muted and tends to lag recessions. This feature will be important for interpreting how the estimated trend LFP rate changed with the pandemic.

Finally, Figure 3 combines the information from the LFP rate and unemployment rate and plots actual and trend rates for EPOP. On the one hand, given the relatively small trend decline of the unemployment rate, the trend for EPOP mainly reflects the trend for the LFP rate and inherits its hump-shaped path and the projected decline over the next 10 years. On the other hand, EPOP inherits the volatility from the unemployment rate. In 2019, EPOP is notably above trend, by about 1 percentage point.

Unemployment and Labor Force Participation During the Pandemic

The behavior of unemployment resulting from the pandemic-induced recession was different from past recessions:

- The entire increase in unemployment between February and April 2020 was accounted for by the increase in unemployment from temporary layoffs. This differed from previous recessions, when a spike in permanent layoffs led the bulge of unemployment in the trough.

- The recovery started in May 2020, and the speed of recovery was also much faster than in previous recessions. After only seven months, unemployment declined by 8 percentage points.

- The behavior of the unemployment rate is reflected in the 2020 recession being the shortest NBER recession on record: It lasted for two months (March to April 2020).

To summarize, the runup and decline of the unemployment rate during the pandemic were unusually rapid, but the qualitative features were not that different from previous recessions after properly accounting for temporary layoffs, as noted in the 2020 working paper " The Unemployed With Jobs and Without Jobs . "

The decline in the LFP rate was sharp and persistent. The LFP rate dropped from 63.4 percent in February 2020 to 60.2 percent in April 2020, an unprecedented drop during such a short period of time. After a rebound to 61.7 percent in August 2020, the LFP rate essentially moved sideways and remained below 62 percent until the end of 2021.

The large drop in the aggregate LFP rate has been attributed to, among others:

- More people — especially women — leaving the labor force to care for children because of school closings or to care for relatives at increased health risk, as noted in the 2021 work " Assessing Five Statements About the Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Women (PDF) " and the 2021 article " Caregiving for Children and Parental Labor Force Participation During the Pandemic "

- An increase in retirement due to health concerns, as noted in the 2021 working paper " How Has COVID-19 Affected the Labor Force Participation of Older Workers? "

- Generous pandemic income transfers and unemployment insurance programs, as noted in the 2021 article " COVID Transfers Dampening Employment Growth, but Not Necessarily a Bad Thing "

All of these factors might impact the participation trend, but by how much?

The Pandemic's Effect on Trend Estimates for LFP and Unemployment

The aggregate trend assessment for the LFP and unemployment rates has changed considerably as a result of 2020 and 2021. Repeating the estimation of trend and cycle for our demographic groups using data from 1976 up to 2021 yields the pink trend lines in Figures 1 and 2.

The updated trend estimates now put the positive cyclical gap in 2019 for LFP at 0.5 percentage points (rather than 0.3 percentage points) and the negative cyclical gap for the unemployment rate at 1.4 percentage points (rather than 1 percentage point). That is, by this estimate of the trend, the labor market in 2019 was even hotter than by the estimates from the 1976-2019 period.

In 2021, the actual LFP rate is essentially at trend, and the unemployment rate is only slightly above trend. That is, by this estimate of the trend, the labor market is relatively tight.

Notice that even though the new 2021 trend estimates for both the LFP and the unemployment rates differ noticeably from the trend values predicted for 2021 based on data up to 2019, the trend revisions for the LFP rate are limited to more recent years, whereas the trend revisions for the unemployment rate apply to the whole sample.

The difference in revisions is related to how confident we can be about the estimated trends. The 90 percent coverage area is quite narrow for the LFP rate for the entire sample up to the last four years. Thus, there is no need to drastically revise the estimated trend prior to 2017.

On the other hand, the 90 percent coverage area for the trend unemployment rate is quite broad throughout the sample. That is, a wide range of values for trend unemployment is potentially consistent with observed unemployment values. Consequently, the last two observations lead to a wholesale reassessment of the level of the trend unemployment rate.

Another way to frame the 2020-21 trend revisions is as follows. The unemployment rate is very cyclical, deviations from trend are large, and though the sharp increase and decline of the unemployment rate in 2020-21 is unusual, an upward level shift of the trend unemployment rate best reflects the additional pandemic data.

The LFP rate, however, is usually not very cyclical, and it is only weakly related to the unemployment rate. Since the model assumes that the cyclical response does not change over the sample, it then attributes the large 2020-21 drop of the LFP rate to a decline in its trend and ultimately to a decline of the trend LFP rates of most demographic groups.

Finally, the EPOP trend is again mainly determined by the LFP trend, seen in Figure 3. Including the pandemic years noticeably lowers the estimated trend for the years from 2017 onwards. The cyclical gap in 2019 is now estimated to be 1.4 percentage points, and 2021 EPOP is close to its estimated trend.

What Does the Future Hold?

In our framework, current estimates of trend LFP and the unemployment rate for demographic groups are the best forecasts of future rates. Combined with projected demographic changes, this implies a continued noticeable downward trend for the LFP rate and a slight downward trend for the unemployment rate.

The trend unemployment rate is low, independent of how we estimate the trend. But given the highly unusual circumstances of the pandemic, the model may well overstate the decline in the trend LFP rate. Therefore, it is likely that the "true" trend lies somewhere between the trends estimated using data up to 2019 and data up to 2021.

That being a possibility, it remains that labor markets as of now have been unusually tight by most other measures, such as nominal wage growth and posted job openings relative to hires. This suggests that the true trend is closer to the revised 2021 trend than to the 2019 trend. In other words, the LFP rate and unemployment rate at the end of 2021 relative to the 2021 estimate of trend LFP and unemployment rate are consistent with a tight labor market.

Andreas Hornstein is a senior advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Marianna Kudlyak is a research advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Hornstein, Andreas; and Kudlyak, Marianna. (April 2022) "The Pandemic's Impact on Unemployment and Labor Force Participation Trends." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief , No. 22-12.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

V iews expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Subscribe to Economic Brief

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.

Thank you for signing up!

As a new subscriber, you will need to confirm your request to receive email notifications from the Richmond Fed. Please click the confirm subscription link in the email to activate your request.

If you do not receive a confirmation email, check your junk or spam folder as the email may have been diverted.

Phone Icon Contact Us

Module 7: Macroeconomic Measures — Unemployment and Inflation

The natural rate of unemployment, learning objectives.

- Explain natural unemployment

- Assess relationships between the natural rate of employment and potential real GDP, productivity, and public policy

Natural Unemployment and Potential Real GDP

Let’s close our introduction to unemployment with another look at the natural rate. The natural rate of unemployment is the unemployment rate that would exist in a growing and healthy economy. In other words, the natural rate of unemployment includes only frictional and structural unemployment, and not cyclical unemployment.

The natural rate of unemployment is related to two other important concepts: full employment and potential real GDP. The economy is considered to be at full employment when the actual unemployment rate is equal to the natural rate. When the economy is at full employment, real GDP is equal to potential real GDP. By contrast, when the economy is below full employment, the unemployment rate is greater than the natural unemployment rate and real GDP is less than potential. Finally, when the economy is above full employment, then the unemployment rate is less than the natural unemployment rate and real GDP is greater than potential. Operating above potential is only possible for a short while, since it is analogous to workers working overtime.

Productivity Shifts and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

Unexpected shifts in productivity can have a powerful effect on the natural rate of unemployment. Over time, the level of wages in an economy will be determined by the productivity of workers. After all, if a business paid workers more than could be justified by their productivity, the business will ultimately lose money and go bankrupt. Conversely, if a business tries to pay workers less than their productivity then, in a competitive labor market, other businesses will find it worthwhile to hire away those workers and pay them more.

However, adjustments of wages to productivity levels will not happen quickly or smoothly. Wages are typically reviewed only once or twice a year. In many modern jobs, it is difficult to measure productivity at the individual level. For example, how precisely would one measure the quantity produced by an accountant who is one of many people working in the tax department of a large corporation? Because productivity is difficult to observe, wage increases are often determined based on recent experience with productivity; if productivity has been rising at, say, 2% per year, then wages rise at that level as well. However, when productivity changes unexpectedly, it can affect the natural rate of unemployment for a time.

The U.S. economy in the 1970s and 1990s provides two vivid examples of this process. In the 1970s, productivity growth slowed down unexpectedly. For example, output per hour of U.S. workers in the business sector increased at an annual rate of 3.3% per year from 1960 to 1973, but only 0.8% from 1973 to 1982. The interactive graph below (Figure 1) illustrates the situation where the demand for labor—that is, the quantity of labor that business is willing to hire at any given wage—has been shifting out a little each year because of rising productivity, from D 0 to D 1 to D 2 . As a result, equilibrium wages have been rising each year from W 0 to W 1 to W 2 . But when productivity unexpectedly slows down, the pattern of wage increases does not adjust right away. Wages keep rising each year from W 2 to W 3 to W 4 . But the demand for labor is no longer shifting up. A gap opens where the quantity of labor supplied at wage level W 4 is greater than the quantity demanded. The natural rate of unemployment rises; indeed, in the aftermath of this unexpectedly low productivity in the 1970s, the national unemployment rate did not fall below 7% from May, 1980 until 1986. Over time, the rise in wages will adjust to match the slower gains in productivity, and the unemployment rate will ease back down. But this process may take years.

Figure 1 (Interactive Graph): Productivity rises, and then stops rising

The late 1990s provide an opposite example: instead of the surprise decline in productivity in the 1970s, productivity unexpectedly rose in the mid-1990s. The annual growth rate of real output per hour of labor increased from 1.7% from 1980–1995, to an annual rate of 2.6% from 1995–2001. Let’s simplify the situation a bit, so that the economic lesson of the story is easier to see graphically, and say that productivity had not been increasing at all in earlier years, so the intersection of the labor market was at point E in the interactive graph (Figure 2) below, where the demand curve for labor (D 0 ) intersects the supply curve for labor. As a result, real wages were not increasing. Now, productivity jumps upward, which shifts the demand for labor out to the right, from D 0 to D 1 . At least for a time, however, wages are still being set according to the earlier expectations of no productivity growth, so wages do not rise. The result is that at the prevailing wage level (W), the quantity of labor demanded (Q 1 ) will for a time exceed the quantity of labor supplied (Q 0 ), and unemployment will be very low—actually below the natural level of unemployment for a time. This pattern of unexpectedly high productivity helps to explain why the unemployment rate stayed below 4.5%—quite a low level by historical standards—from 1998 until after the U.S. economy had entered a recession in 2001.

Figure 2 (Interactive Graph): Productivity doesn’t change, and then rises.

Average levels of unemployment will tend to be somewhat higher on average when productivity is unexpectedly low, and conversely, will tend to be somewhat lower on average when productivity is unexpectedly high. But over time, wages do eventually adjust to reflect productivity levels.

Public Policy and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

Public policy can also have a powerful effect on the natural rate of unemployment. On the supply side of the labor market, public policies to assist the unemployed can affect how eager people are to find work. For example, if a worker who loses a job is guaranteed a generous package of unemployment insurance, welfare benefits, food stamps, and government medical benefits, then the opportunity cost of being unemployed is lower and that worker will be less eager to seek a new job.

What seems to matter most is not just the amount of these benefits, but how long they last. A society that provides generous help for the unemployed that cuts off after, say, six months, may provide less of an incentive for unemployment than a society that provides less generous help that lasts for several years. Conversely, government assistance for job search or retraining can in some cases encourage people back to work sooner. Reference the following section to learn how the U.S. handles unemployment insurance.

HOW DOES U.S. UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE WORK?

Unemployment insurance is a joint federal–state program, established by federal law in 1935. The federal government sets minimum standards for the program, but most of the administration is done by state governments. The funding for the program is a federal tax collected from employers. The federal government requires that the tax be collected on the first $7,000 in wages paid to each worker; however, states can choose to collect the tax on a higher amount if they wish, and 41 states have set a higher limit. States can choose the length of time that benefits will be paid, although most states limit unemployment benefits to 26 weeks—with extensions possible in times of especially high unemployment. The fund is then used to pay benefits to those who become unemployed. Average unemployment benefits are equal to about one-third of the wage earned by the person in his or her previous job, but the level of unemployment benefits varies considerably across states.

One other interesting thing to note about the classifications of unemployment—an individual does not have to collect unemployment benefits to be classified as unemployed. While there are statistics kept and studied relating to how many people are collecting unemployment insurance, this is not the source of unemployment rate information.

On the demand side of the labor market, government rules social institutions, and the presence of unions can affect the willingness of firms to hire. For example, if a government makes it hard for businesses to start up or to expand, by wrapping new businesses in bureaucratic red tape, then businesses will become more discouraged about hiring. Government regulations can make it harder to start a business by requiring that a new business obtain many permits and pay many fees, or by restricting the types and quality of products that can be sold. Other government regulations, like zoning laws, may limit where business can be done, or whether businesses are allowed to be open during evenings or on Sunday.

Whatever defenses may be offered for such laws in terms of social value, these kinds of restrictions impose a barrier between some willing workers and other willing employers, and thus contribute to a higher natural rate of unemployment. Similarly, if government makes it difficult to fire or lay off workers, businesses may react by trying not to hire more workers than strictly necessary—since laying these workers off would be costly and difficult. High minimum wages may discourage businesses from hiring low-skill workers. Government rules may encourage and support powerful unions, which can then push up wages for union workers, but at a cost of discouraging businesses from hiring those workers.

The Natural Rate of Unemployment in Recent Years

The underlying economic, social, and political factors that determine the natural rate of unemployment can change over time, which means that the natural rate of unemployment can change over time, too. Estimates by economists of the natural rate of unemployment in the U.S. economy in the early 2000s run at about 4.5% to 5.5%. This is a lower estimate than earlier. Three of the common reasons proposed by economists for this change are outlined below.

- The Internet has provided a remarkable new tool through which job seekers can find out about jobs at different companies and can make contact with relative ease. An Internet search is far easier than trying to find a list of local employers and then hunting up phone numbers for all of their human resources departments, requesting a list of jobs and application forms, and so on. Social networking sites such as LinkedIn have changed how people find work as well.

- The growth of the temporary worker industry has probably helped to reduce the natural rate of unemployment. In the early 1980s, only about 0.5% of all workers held jobs through temp agencies; by the early 2000s, the figure had risen above 2%. Temp agencies can provide jobs for workers while they are looking for permanent work. They can also serve as a clearinghouse, helping workers find out about jobs with certain employers and getting a tryout with the employer. For many workers, a temp job is a stepping-stone to a permanent job that they might not have heard about or gotten any other way, so the growth of temp jobs will also tend to reduce frictional unemployment.