Ethical Decision Making Models and 6 Steps of Ethical Decision Making Process

By Andre Wyatt on March 21, 2023 — 10 minutes to read

In many ways, ethics may feel like a soft subject, a conversation that can wait when compared to other more seemingly pressing issues (a process for operations, hiring the right workers, and meeting company goals). However, putting ethics on the backburner can spell trouble for any organization. Much like the process of businesses creating the company mission, vision, and principles ; the topic of ethics has to enter the conversation. Ethics is far more than someone doing the right thing; it is many times tied to legal procedures and policies that if breached can put an organization in the midst of trouble.

- A general definition of business ethics is that it is a tool an organization uses to make sure that managers, employees, and senior leadership always act responsibly in the workplace with internal and external stakeholders.

- An ethical decision-making model is a framework that leaders use to bring these principles to the company and ensure they are followed.

- Importance of Ethical Standards Part 1

- Ethical Decision-Making Model Approach Part 2

- Ethical Decision-Making Process Part 3

- PLUS Ethical Decision-Making Model Part 4

- Character-Based Decision-Making Model Part 5

The Importance of Ethical Standards

Leaders have to develop ethical standards that employees in their company will be required to adhere to. This can help move the conversation toward using a model to decide when someone is in violation of ethics.

There are five sources of ethical standards:

Utilitarian

Common good.

While many of these standards were created by Greek Philosophers who lived long ago, business leaders are still using many of them to determine how they deal with ethical issues. Many of these standards can lead to a cohesive ethical decision-making model.

What is the purpose of an ethical decision-making model?

Ethical decision-making models are designed to help individuals and organizations make decisions in an ethical manner.

The purpose of an ethical decision-making model is to ensure that decisions are made in a manner that takes into account the ethical implications for all stakeholders involved.

Ethical decision-making models provide a framework for analyzing ethical dilemmas and serve as a guide for identifying potential solutions. By utilizing these models, businesses can ensure they are making decisions that align with their values while minimizing the risk of harming stakeholders. This can result in better decision-making and improved reputation.

Why is it important to use an ethical decision making model?

Making ethical decisions is an integral part of being a responsible leader and member of society. It is crucial to use an ethical decision making model to ensure that all stakeholders are taken into account and that decisions are made with the highest level of integrity. An ethical decision making model provides a framework for assessing the potential consequences of each choice, analyzing which option best aligns with personal values and organizational principles, and then acting on those conclusions.

An Empirical Approach to an Ethical Decision-Making Model

In 2011, a researcher at the University of Calgary in Calgary, Canada completed a study for the Journal of Business Ethics.

The research centered around an idea of rational egoism as a basis for developing ethics in the workplace.

She had 16 CEOs formulate principles for ethics through the combination of reasoning and intuition while forming and applying moral principles to an everyday circumstance where a question of ethics could be involved.

Through the process, the CEOs settled on a set of four principles:

- self-interest

- rationality

These were the general standards used by the CEOs in creating a decision about how they should deal with downsizing. While this is not a standard model, it does reveal the underlying ideas business leaders use to make ethical choices. These principles lead to standards that are used in ethical decision-making processes and moral frameworks.

How would you attempt to resolve a situation using an ethical decision-making model?

When facing a difficult situation, it can be beneficial to use an ethical decision-making model to help you come to the best possible solution. These models are based on the idea that you should consider the consequences of your decision, weigh the various options available, and consider the ethical implications of each choice. First, you should identify the problem or situation and clearly define what it is. Then, you must assess all of the possible outcomes of each choice and consider which one is most ethical. Once you have identified your preferred option, you should consult with others who may be affected by your decision to ensure that it aligns with their values and interests. You should evaluate the decision by considering how it affects yourself and others, as well as how it meets the expectations of your organization or institution.

The Ethical Decision-Making Process

Before a model can be utilized, leaders need to work through a set of steps to be sure they are bringing a comprehensive lens to handling ethical disputes or problems.

Take Time to Define the Problem

Consult resources and seek assistance, think about the lasting effects, consider regulations in other industries, decide on a decision, implement and evaluate.

While each situation may call for specific steps to come before others, this is a general process that leaders can use to approach ethical decision-making . We have talked about the approach; now it is time to discuss the lens that leaders can use to make the final decision that leads to implementation.

PLUS Ethical Decision-Making Model

PLUS Ethical Decision-Making Model is one of the most used and widely cited ethical models.

To create a clear and cohesive approach to implementing a solution to an ethical problem; the model is set in a way that it gives the leader “ ethical filters ” to make decisions.

It purposely leaves out anything related to making a profit so that leaders can focus on values instead of a potential impact on revenue.

The letters in PLUS each stand for a filter that leaders can use for decision-making:

- P – Policies and Procedures: Is the decision in line with the policies laid out by the company?

- L – Legal: Will this violate any legal parameters or regulations?

- U – Universal: How does this relate to the values and principles established for the organization to operate? Is it in tune with core values and the company culture?

- S – Self: Does it meet my standards of fairness and justice? This particular lens fits well with the virtue approach that is a part of the five common standards mentioned above.

These filters can even be applied to the process, so leaders have a clear ethical framework all along the way. Defining the problem automatically requires leaders to see if it is violating any of the PLUS ethical filters. It should also be used to assess the viability of any decisions that are being considered for implementation, and make a decision about whether the one that was chosen resolved the PLUS considerations questioned in the first step. No model is perfect, but this is a standard way to consider four vital components that have a substantial ethical impact .

The Character-Based Decision-Making Model

While this one is not as widely cited as the PLUS Model, it is still worth mentioning. The Character-Based Decision-Making Model was created by the Josephson Institute of Ethics, and it has three main components leaders can use to make an ethical decision.

- All decisions must take into account the impact to all stakeholders – This is very similar to the Utilitarian approach discussed earlier. This step seeks to do good for most, and hopefully avoid harming others.

- Ethics always takes priority over non-ethical values – A decision should not be rationalized if it in any way violates ethical principles. In business, this can show up through deciding between increasing productivity or profit and keeping an employee’s best interest at heart.

- It is okay to violate another ethical principle if it advances a better ethical climate for others – Leaders may find themselves in the unenviable position of having to prioritize ethical decisions. They may have to choose between competing ethical choices, and this model advises that leaders should always want the one that creates the most good for as many people as possible.

There are multiple components to consider when making an ethical decision. Regulations, policies and procedures, perception, public opinion, and even a leader’s morality play a part in how decisions that question business ethics should be handled. While no approach is perfect, a well-thought-out process and useful framework can make dealing with ethical situations easier.

- How to Resolve Employee Conflict at Work [Steps, Tips, Examples]

- 5 Challenges and 10 Solutions to Improve Employee Feedback Process

- How to Identify and Handle Employee Underperformance? 5 Proven Steps

- Organizational Development: 4 Main Steps and 8 Proven Success Factors

- 7 Steps to Leading Virtual Teams to Success

- 7 Steps to Create the Best Value Proposition [How-To’s and Best Practices]

- Training & Certification

- Knowledge Center

- ECI Research

- Business Integrity Library

- Career Center

- The PLUS Ethical Decision Making Model

Seven Steps to Ethical Decision Making – Step 1: Define the problem (consult PLUS filters ) – Step 2: Seek out relevant assistance, guidance and support – Step 3: Identify alternatives – Step 4: Evaluate the alternatives (consult PLUS filters ) – Step 5: Make the decision – Step 6: Implement the decision – Step 7: Evaluate the decision (consult PLUS filters )

Introduction Organizations struggle to develop a simple set of guidelines that makes it easier for individual employees, regardless of position or level, to be confident that his/her decisions meet all of the competing standards for effective and ethical decision-making used by the organization. Such a model must take into account two realities:

- Every employee is called upon to make decisions in the normal course of doing his/her job. Organizations cannot function effectively if employees are not empowered to make decisions consistent with their positions and responsibilities.

- For the decision maker to be confident in the decision’s soundness, every decision should be tested against the organization’s policies and values, applicable laws and regulations as well as the individual employee’s definition of what is right, fair, good and acceptable.

The decision making process described below has been carefully constructed to be:

- Fundamentally sound based on current theories and understandings of both decision-making processes and ethics.

- Simple and straightforward enough to be easily integrated into every employee’s thought processes.

- Descriptive (detailing how ethical decision are made naturally) rather than prescriptive (defining unnatural ways of making choices).

Why do organizations need ethical decision making? See our special edition case study, #RespectAtWork, to find out.

First, explore the difference between what you expect and/or desire and the current reality. By defining the problem in terms of outcomes, you can clearly state the problem.

Consider this example: Tenants at an older office building are complaining that their employees are getting angry and frustrated because there is always a long delay getting an elevator to the lobby at rush hour. Many possible solutions exist, and all are predicated on a particular understanding the problem:

- Flexible hours – so all the tenants’ employees are not at the elevators at the same time.

- Faster elevators – so each elevator can carry more people in a given time period.

- Bigger elevators – so each elevator can carry more people per trip.

- Elevator banks – so each elevator only stops on certain floors, increasing efficiency.

- Better elevator controls – so each elevator is used more efficiently.

- More elevators – so that overall carrying capacity can be increased.

- Improved elevator maintenance – so each elevator is more efficient.

- Encourage employees to use the stairs – so fewer people use the elevators.

The real-life decision makers defined the problem as “people complaining about having to wait.” Their solution was to make the wait less frustrating by piping music into the elevator lobbies. The complaints stopped. There is no way that the eventual solution could have been reached if, for example, the problem had been defined as “too few elevators.”

How you define the problem determines where you go to look for alternatives/solutions– so define the problem carefully.

Step 2: Seek out relevant assistance, guidance and support

Once the problem is defined, it is critical to search out resources that may be of assistance in making the decision. Resources can include people (i.e., a mentor, coworkers, external colleagues, or friends and family) as well professional guidelines and organizational policies and codes. Such resources are critical for determining parameters, generating solutions, clarifying priorities and providing support, both while implementing the solution and dealing with the repercussions of the solution.

Step 3: Identify available alternative solutions to the problem The key to this step is to not limit yourself to obvious alternatives or merely what has worked in the past. Be open to new and better alternatives. Consider as many as solutions as possible — five or more in most cases, three at the barest minimum. This gets away from the trap of seeing “both sides of the situation” and limiting one’s alternatives to two opposing choices (i.e., either this or that).

Step 4: Evaluate the identified alternatives As you evaluate each alternative, identify the likely positive and negative consequence of each. It is unusual to find one alternative that would completely resolve the problem and is significantly better than all others. As you consider positive and negative consequences, you must be careful to differentiate between what you know for a fact and what you believe might be the case. Consulting resources, including written guidelines and standards, can help you ascertain which consequences are of greater (and lesser) import.

You should think through not just what results each alternative could yield, but the likelihood it is that such impact will occur. You will only have all the facts in simple cases. It is reasonable and usually even necessary to supplement the facts you have with realistic assumptions and informed beliefs. Nonetheless, keep in mind that the more the evaluation is fact-based, the more confident you can be that the expected outcome will occur. Knowing the ratio of fact-based evaluation versus non-fact-based evaluation allows you to gauge how confident you can be in the proposed impact of each alternative.

Step 5: Make the decision When acting alone, this is the natural next step after selecting the best alternative. When you are working in a team environment, this is where a proposal is made to the team, complete with a clear definition of the problem, a clear list of the alternatives that were considered and a clear rationale for the proposed solution.

Step 6: Implement the decision While this might seem obvious, it is necessary to make the point that deciding on the best alternative is not the same as doing something. The action itself is the first real, tangible step in changing the situation. It is not enough to think about it or talk about it or even decide to do it. A decision only counts when it is implemented. As Lou Gerstner (former CEO of IBM) said, “There are no more prizes for predicting rain. There are only prizes for building arks.”

Step 7: Evaluate the decision Every decision is intended to fix a problem. The final test of any decision is whether or not the problem was fixed. Did it go away? Did it change appreciably? Is it better now, or worse, or the same? What new problems did the solution create?

Ethics Filters

The ethical component of the decision making process takes the form of a set of “filters.” Their purpose is to surface the ethics considerations and implications of the decision at hand. When decisions are classified as being “business” decisions (rather than “ethics” issues), values can quickly be left out of consideration and ethical lapses can occur.

At key steps in the process, you should stop and work through these filters, ensuring that the ethics issues imbedded in the decision are given consideration.

We group the considerations into the mnemonic PLUS.

- P = Policies Is it consistent with my organization’s policies, procedures and guidelines?

- L = Legal Is it acceptable under the applicable laws and regulations?

- U = Universal Does it conform to the universal principles/values my organization has adopted?

- S = Self Does it satisfy my personal definition of right, good and fair?

The PLUS filters work as an integral part of steps 1, 4 and 7 of the decision-making process. The decision maker applies the four PLUS filters to determine if the ethical component(s) of the decision are being surfaced/addressed/satisfied.

- Does the existing situation violate any of the PLUS considerations?

- Step 2: Seek out relevant assistance, guidance and support

- Step 3: Identify available alternative solutions to the problem

- Will the alternative I am considering resolve the PLUS violations?

- Will the alternative being considered create any new PLUS considerations?

- Are the ethical trade-offs acceptable?

- Step 5: Make the decision

- Step 6: Implement the decision

- Does the resultant situation resolve the earlier PLUS considerations?

- Are there any new PLUS considerations to be addressed?

The PLUS filters do not guarantee an ethically-sound decision. They merely ensure that the ethics components of the situation will be surfaced so that they might be considered.

How Organizations Can Support Ethical Decision-Making Organizations empower employees with the knowledge and tools they need to make ethical decisions by

- Intentionally and regularly communicating to all employees:

- Organizational policies and procedures as they apply to the common workplace ethics issues.

- Applicable laws and regulations.

- Agreed-upon set of “universal” values (i.e., Empathy, Patience, Integrity, Courage [EPIC]).

- Providing a formal mechanism (i.e., a code and a helpline, giving employees access to a definitive interpretation of the policies, laws and universal values when they need additional guidance before making a decision).

- Free Ethics & Compliance Toolkit

- Ethics and Compliance Glossary

- Definitions of Values

- Why Have a Code of Conduct?

- Code Construction and Content

- Common Code Provisions

- Ten Style Tips for Writing an Effective Code of Conduct

- Five Keys to Reducing Ethics and Compliance Risk

- Business Ethics & Compliance Timeline

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Scher S, Kozlowska K. Rethinking Health Care Ethics [Internet]. Singapore: Palgrave Pivot; 2018. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-0830-7_5

Rethinking Health Care Ethics [Internet].

Chapter 5 the elusiveness of closure.

Published online: August 3, 2018.

Unlike what happens in the classroom, where discussions can end in conflict, with agreement nowhere in sight, ethical problems in clinical health care require that decisions be made. Some form of closure is required in order to move forward. And closure can be elusive indeed. In this chapter we look at efforts to achieve closure through the use of multistep processes, as proposed by some bioethicists.

In clinical practice, ethical problems do not arise out of nowhere. They develop, over time, from preexisting, but evolving, clinical situations. We start this chapter with a vignette adapted from the clinical experience of the second author (KK).

- Vignette: A Morbidly Obese, Developmentally Delayed 14-Year-Old

A family presents with a 150-kilogram (330-pound), epileptic, developmentally delayed, violent 14-year-old boy with a genetically related dementing illness. He had recently started refusing to leave home, with the consequence that he has not been attending school. At the observational admission, the clinical situation is assessed by the full range of health professionals at the hospital. Particular problems are identified as amenable to intervention, and both staff and family members are given various follow-up tasks to complete, including the following: a trial of different medications; provision of respite services for the parents; organization of services to assist in transporting the child to school on a regular basis; further review of the boy’s behavior-management program; and an assessment of the mother’s and possibly father’s mental and physical health.

Over the course of the next year, the father’s increasing stress about the situation at home led him to withdraw from the family, to spend more time at work, and to opt for more work-related travel assignments. The mother became increasingly depressed, could not, on her own, summon up the energy required to maintain the son’s educational and health status, and lost her capacity to resist his demands for food. As a consequence, the son’s weight continued to increase; he stopped attending school again; he was rarely leaving his bed; and a medical assessment concluded that without a return to the previous routine, the son’s hypertension would become uncontrollable, and he would develop further, potentially life-threatening complications of both obesity and immobility. Though neither the mother nor father was capable of providing proper care for their son, they were also both adamant that the child’s care was their business alone and that health professionals and others should stay away. The health professionals noted that without adequate care, the boy would likely either die very prematurely or end up creating an indeterminate (and presumably vast) stream of medical costs that would come out of the public treasury and decrease the funds available to care for other patients.

In a standard textbook on health care ethics, the case would likely here with the question “What should be done?”—or perhaps with a series of questions about, for example, the various stakeholders, their rights and interests, which have priority, how one decides such matters, whether a 14-year-old is potentially competent to make decisions in his own behalf, and whether family privacy overrides the public interest.

What is certain is that such a case would provide the basis for a class discussion that would be interesting, engaging, or even exuberant. But engaging students in a classroom discussion is one thing. Reaching a single, sound clinical decision in a situation permeated with suffering and distress is quite another.

- Multistep Processes for Achieving Closure

For the purpose of reaching decisions in difficult clinical situations, bioethicists have proposed various sorts of multistep processes for health professionals to follow, enabling them to address all the relevant issues. For example, in Ethics and Law for the Health Professions ( 2013 , pp. 138–139), Ian Kerridge and colleagues present a seven-step process: (1) identify the ethical problem; (2) get the facts; (3) consider core ethical principles; (4) consider how the problem would look from another perspective or using another theory; (5) identify ethical conflicts; (6) consider the law; and (7) identify a way forward. The full scope of what is required becomes manifest only in the complete description of the seven steps (see Text Box 5.1 ).

Text Box 5.1: A Model for Ethical Problem Solving in Clinical Medicine

Identify the ethical problem:

Consider the problem within its context and attempt to distinguish between ethical problems and other medical, social, cultural, linguistic and legal issues.

Explore the meaning of value-laden terms, e.g. futility, quality of life.

Get the facts:

Find out as much as you can about the problem through history, examination and relevant investigations.

Take the time to listen to the patient’s narrative and understand their personal and cultural biography.

Identify whether there are necessary facts that you do not have? If so, search for them.

Use the principles of Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) where possible when assessing or epidemiological evidence.

Consider core ethical principles:

Autonomy: what is the patient’s (or surrogate’s) preferences, goals and values; what is the patient’s approach to the problem?

Beneficence: what benefits can be obtained for the patient?

Non-maleficence: what are the risks and how can they be minimized or avoided?

Justice: how are the interests of different parties to be balanced? How can equity or fairness be maximized?

Confidentiality/privacy: what information is private and does confidentiality need to be limited or breached?

Veracity: has the patient and their family been honestly informed and is there any reason why the patient cannot know the truth?

Consider how the problem would look from another perspective or using another theory:

Who are the relevant stakeholders? What is their interest? What do they have to lose? How salient are their interests? How powerful are they? How legitimate are they? How urgent are they?

How would the problem look like from an alternative ethical position? For example, consequentialist, rights-based, virtue-based, feminist, communitarian, or care-based.

Has someone else solved a similar problem in the past? How did they do it?

Identify ethical conflicts (e.g. between principles, values or perspectives):

Explain why the conflicts occur and how they may be resolved.

Consider the law:

Identify relevant legal concepts and laws and how they might guide management.

Examine relationship between clinical-ethical decision and the law.

Identify a way forward:

Identify ethically viable options;

Identify the option chose, for example, by specifying how guiding principles were balanced or by clarifying what issues or processes were considered most significant, and why;

Be clear about who was responsible for the decision;

Communicate the choice and assist relevant stakeholders determine an action plan;

Document the process;

Assist/mediate resolution of any conflict;

Evaluate the outcome.

From Kerridge I., Lowe M., and Stewart C., Ethics and Law for the Health Professions , 4th ed. (Sydney: Federation Press, 2013 ). Reprinted with permission.

More concretely, in presenting multistep processes as a means of addressing ethical “dilemmas”—presumably, situations in which a straightforward application of ethical principles yields no unequivocal answer—bioethicists implicitly assert that such processes actually will lead, in some way, to the desired closure. But such processes, if brought to closure via a full consideration of all the relevant issues, are even more complex than Kerridge’s seven steps would suggest. Just how complex can be seen if we look not at bioethics but at what’s involved when law courts consider cases that have been appealed. In such situations, a lower court would have made a decision based on its consideration of both the law and the facts, as in a jury trial. On appeal—in a process that closely parallels the multistep consideration of difficult ethical questions in bioethics—the appeals court considers only matters of law, against the background facts as determined by the lower court. That process of appealing a decision by a lower court can be considered, for our purposes, as an elaborated version of Kerridge’s multistep process for addressing ethical issues in health care.

In considering the work of appeals courts, our goals are twofold: first, to understand the complexity of such multistep processes, and second, to understand why, in law, they actually work as a means of reaching decisions. In the section after that, we return to consider the use of multistep processes in bioethics.

- The Multistep Process of Appeals Courts

Framing and the Diversity of Perspectives

The work of appeals courts is to make decisions about the law in relation to cases that have previously been decided by lower courts. In particular, a case comes to an appeals court when one side of a case argues that the lower court, in making its decision, was mistaken in how it interpreted or applied the law. The task of the appeals court is to determine whether that interpretation or application was mistaken or not, given the facts as determined by the lower court.

For an appeals court judge (we will be taking U.S. appeals courts as a model here), 1 an initial step is to request each side to prepare a written legal brief presenting arguments to support their own interpretation of the law (or laws) in question—which is parallel to what happens in bioethics courses as students set out to defend their own views against those of their classmates. In these briefs, each side constructs, as it were, a view of the world that seeks to persuade the court to see the case in that way, too. For this purpose, the attorneys involved may well end up invoking the full range of factors used in ethicists’ multistep processes. Historical, cultural, and social factors might be part of framing—and arguing—a case. Linguistic factors are always important in law and may prove central, even decisive. No argument can be made without direct reference to established legal rules and to what that particular court and other courts have done in the past (i.e., relevant precedents ). Policies underlying a particular area of law are regularly invoked. And references to ethical principles are made, too, if they help to support one’s argument (e.g., by referring to factors such as “fundamental fairness”). Another crucial factor in preparing any legal brief, as in a bioethicist’s multistep process, is the need to anticipate and address the arguments of the other side; one test of this comes with oral argument, which enables the judge to probe the positions of the attorneys for each side.

In the case of our morbidly obese, bedbound teenage boy, let’s suppose that (1) a child-protection agency had attempted to remove the boy from his family, (2) the family, possibly with the assistance of some sort of pro bono or public organization (and therefore free or low cost), decided to oppose the removal, and (3) in a court proceeding, it was decided that the agency was legally justified in removing the child. If that decision was then appealed, both sides would be asked to prepare legal briefs presenting their positions. And if one assumes that the situation received attention in the local papers, one would also expect that there might be some, or even many, additional briefs submitted by amici curiae—friends of the court. A family-oriented, pro-parent group might insist that the rights of the parents be protected and that they be allowed to retain their child at home, no matter what the consequences. Likewise for any group writing from either the far right or far left, who would presumably be opposed to the intrusion of the state into what they considered a fundamentally private matter. Some groups representing health professionals or institutions would support the child-protection agency, arguing that protecting the health and well-being of the child is the community’s fundamental concern, whereas other groups might oppose removal, either to protect the psychological health of a disabled, dependent child or to prevent the child’s exposure to physical or sexual abuse in various sorts of foster-care settings. Law professors might write carefully researched, persuasive briefs on both sides of the dispute, often by citing not just the law but the sociological, historical, or anthropological factors relevant to the case.

It is difficult to overstate the potential degree of complexity in such situations. Each brief submitted not only argues in favor of a certain result but provides a distinct set of arguments that typically frame the case in a way that reflects the broader interests of whoever prepared or commissioned that particular brief. Based on such framing, the central issue in the case might be seen as one involving, among others, statutory interpretation, parental rights, children’s rights, state interests, abuse of power, domains of interest (public versus private), or the limits of the judicial authority. And each of these arguments might actually have some real merit.

The Complexities of Closure

In many legal cases, one might think that the availability of an established (and relevant) legal rule would carry the day and move directly to closure. If the case were so simple, however, it would never have been appealed (or accepted for appeal). For example, even when a judge agrees that, other things equal , “the established rule in such situations is that . . . ,” it is still an open question whether other things actually are equal. Deciding that question—and how narrowly or broadly to apply or interpret an established rule—is often a key element in the case, and a key element for judges to determine. In this context, courts need to consider all of the elements discussed in the preceding subsection and also a potentially wide range of subsidiary factors, including the following: How quickly is a decision required? Does the court have the time and resources to assess particular factors? Is there a simpler way of deciding a case without getting into complicated, controversial, or time-consuming issues? Is the issue “ripe”; that is, is enough known, often through previous litigation, about the factors relevant to a particular type of legal situation, enabling the court to make a reasoned, informed decision that is likely not to seem, in time, ill-founded or premature? Likewise, will deciding a case in a particular way end up upsetting established law, with the consequence that the decision would be considered unjustified or would create uncertainty in an area of law (e.g., contracts) where clarity and predictability are especially valued?

Against this background of conflicting legal arguments and, one might say, conflicting views of the world, the judge has to decide not only on a result—that is, which side “wins”—but also on the reasoning that led to that result and on what particular remedy, or course of action, to order. In the example we’re considering—the morbidly obese 14-year-old—the judge might decide in favor of the child-protection agency, set forth (or not) a set of reasons why the arguments presented by the opposing briefs were ultimately not persuasive, and then authorize the agency to remove the child but only pursuant to certain conditions. Such conditions might include (1) the availability of a public institution or even another family to take proper care of the child, (2) provision (or not) for the family to visit the child, and (3) conditions, if any, under which the child’s parents might petition the court to have the child returned home. Alternatively, and as often happens, the judge might decide in favor of the parents, provide a justification for that decision, and leave it to the child-protection agency to determine how best to protect the child at home.

What should be clear, no matter what, is that choosing exactly which arguments are “correct” (or stronger or more persuasive than the others) is no simple, determinate process. And it’s not as if there are only two potential results. A judge might find some middle or different ground for a decision—one not presented by any of the parties or amici curiae. The judge needs to take all the diverse factors into account, as best as he or she can, and with the knowledge that except in unusual cases, there will no single, correct answer, and no single correct legal analysis. Different judges and different courts may reach different results, and even when the actual outcome is the same, they may have reached that position through a different line of reasoning. Judicial decisions are as different as the judges themselves, each with their own sensitivities, political views, attitudes toward risk, need for control, and personal and intellectual histories, among many other differences.

What Makes a Judicial Decision a “Good” One?

That said, what makes a judicial decision a good one, and not merely a legally authoritative one because issued by a judge? The main criterion here is the judge’s capacity to credibly apply existing law and potentially to advance it (if only by a smidgen) while holding true to the constraints within which all judges are expected to act. These constraints include the facts as known, the diverse dimensions of existing law—statutory law (made by the legislative branch of government), case law (judicial branch), and regulatory law (executive branch)—and the wide-ranging histories, social forces, and public policies that have shaped these separate areas of law.

The broader institutional character of law comes into play here. Informed assessments of judicial decisions emerge, over time, though the work of other judges, lawyers, and potentially also commentators and critics from the academic community—which can be understood, in effect, as expressing the collective wisdom of the profession. This institutional feedback will influence, in the short term, whether the decision is appealed to (and changed or overruled by) a higher court and, in the long term, the actual “meaning” of the decision. A decision deemed good will generally be interpreted more broadly and therefore have more legal impact in both the short and long term than a decision deemed poor.

Over time, the overall impact of these assessments is to define relatively stable, fixed points in the legal system that enable lawyers and judges to determine what can and cannot be argued effectively, what can or cannot be reasonably interpreted as a point in contention. Likewise, by virtue of their legal training and professional experience, lawyers and judges come to understand which points are relatively fixed and which not, as well as how hard, and by what sorts of arguments, such fixed points can be questioned. Some points of law and some policies are more fixed than others; some points can be budged fairly easily (albeit only with very good reasons for doing so), whereas others require something much more than that. In the United States, for example, the confidentiality of the psychiatrist-patient relationship can be overridden only when the safety of another person is at risk—as in the case of a patient who tells his therapist that he is planning to murder someone. 2 Various constitutional doctrines have a similar, high threshold for arguing exceptions. Judge-made law actually does evolve, and sometimes change radically, over time. But in general, judges or lawyers who ignore or move too far away from established fixed points of the law are apt to find their own work ignored, disregarded, or disparaged.

Why Does the Judicial Process “Work”?

The persons implementing the model—judges and lawyers—are themselves experts in the relevant field : law. And they bring this expertise to bear throughout the process, from (at the very outset) deciding which cases to litigate, to every stage of the litigation, to the ultimate decision by, and reasoning of, the judge.

The law itself —substantively and procedurally—operates as a constraint. Substantive legal rules permeate and shape the process of judicial decision making, from outset to conclusion. These rules, though not inflexible, are relatively fixed signposts for such decision making. Procedural rules, such as those concerning documentary evidence or the examination of witnesses—keep the legal proceedings moving ahead on a defined path, and without having to recreate the process at every step and for every case.

More concretely, the history of each case serves to frame the relevant issues, and this history helps to determine, in effect, what points of fact and law are in contention, and which are not. It is not that the case, if it arose afresh, might not be seen as raising different issues. The point, instead, is that the history of a case serves to limit the range of issues and focus the attention of the court and the parties involved in the case.

The institutional framework of the law operates as a strong constraint on lawyers and judges, and serves to channel their attention and legal work. Beginning with the professional socialization that occurs in law school and continuing with the bar examination, professional organizations, continuing legal (and even judicial) education, and myriad other activities, life in the law is lived within educational, social, and legal institutions that define what it is to live and work as a lawyer.

- Revisiting Bioethics

The judicial process, as described above, can be understood for our purposes as a formalized, detailed version of the multistep process that Kerridge and colleagues ( 2013 ) recommend for addressing ethical issues in health care. As with the judicial process, the multistep process of ethical decision making should not be expected to produce unique, determinate, “correct” answers. It may be that, in the end, the various dimensions of the ethical problem at hand will be well, even deeply understood. But just how to integrate and balance the various factors remains indeterminate. As in the case of judges and the judicial process, different people will reach different results and for different reasons. More importantly, however, the multistep process in bioethics is not subject to the same constraints that channel the judicial process and that lead to what legal commentators see as generally good results.

The proposed multistep process for making ethical decisions incorporates none of the four constraints that channel the judicial process and that lead toward good, generally respected decisions. The most obvious and important difference is that health professionals are not experts in bioethics or in reasoning from ethical principles—the form of reasoning required by Kerridge and colleagues’ multistep process (or, indeed, by other multistep processes). Although bioethicists and philosophers undoubtedly feel comfortable with, and are adept at, analyzing ethical problems through the use of abstract ethical principles, they have reached that point only through explicit, lengthy training in academic programs designed just for that purpose. Needless to say, health professionals have not had that sort of training, and there is no reason to expect them to think and act as though they had.

A second shortcoming of bioethics’ multistep process is that ethical principles do not have the same, relatively stable and knowable structure as the law. As noted above, the judicial process operates within substantive and procedural constraints that channel the work of lawyers and judges—and it is just this rule-defined structure that law students learn in law school and that is, in large part, tested for in state bar examinations (without which no one can legally practice law). Put quite simply, these substantive and procedural constraints—the fixed points that serve to define an entire field of human activity—have no parallel in bioethics or in ethics generally. The problem here is easy to explain. Suppose that two ethical principles conflict. How does one proceed to address the conflict? Bioethicists and philosophers might have some relevant expertise. Health professional simply do not.

A third shortcoming of bioethics’ multistep process is that clinical situations raising ethical problems are not well defined in the way that they are in judicial decision making. Cases are not accepted for appeal because they have been, in some generic way, improperly decided by a lower court. Appeals are made, and accepted by higher courts, because some particular point or points of law—the grounds for appeal —may have been decided incorrectly by a lower court. This focus enables the process to move toward closure. By contrast, the bioethical process actually moves in the direction of increased complexity. The closer one looks, and the more exhaustively one attempts to address the full range of issues presented by an ethical situation, the more there is to see (with more and more issues to be explored and decided), the more complex the emotions experienced by the participants, and the more one moves away from a single, potentially determinate result. Judges expect such complexity and, indeed, are expected to make decisions that take into account such complexity. That’s their job! But it isn’t what health professionals are trained to do, and there’s no reason to think that they can do it, especially within the time constraints of clinical health care.

A fourth shortcoming of bioethics’ multistep process is that the institutional framework that constrains and channels the work of health professionals is oriented toward the provision of health care—understanding and treating disease and health-related problems. Analyzing difficult ethical problems by using abstract ethical principles is not part of that institutional framework. Health professionals are not trained, and not socialized, to deal with difficult ethical problems in that way. Health professional do, indeed, deal with such problems whenever they arise. But they do so only after careful discussions, insofar as possible, with colleagues as well as with patients and their families and carers. Each clinician brings to these discussions his or her own clinical experience and established, clinically informed ethical views. But using abstract ethical principles to address ethical problems is not an integral part of this process, and of what it is to live and work as a health professional.

- The Way Forward

Confronted with the suggestion that they engage in a multistep process for making ethical decisions, one can easily imagine the following—but hypothetical—response by health professionals:

Lawyers are trained in the complexities of such models, and they work with such models, in such systems, their entire professional lives. Likewise, judges learn to make decisions in situations involving innumerable complexities of law, ethics, and public policy, all with underlying human dimensions. Much the same might be said of bioethicists, who are specifically trained to deal with ethical principles and all their complexities. But we have not been trained in any of those ways, and we aren’t comfortable dealing with ethical theory and matters of public policy. Our world is concrete and clinical, and our goals are tied in with the welfare of our particular patients. In lieu of a multistep process requiring abstract analysis and the application of ethical principles, give us something that we can work with.

That’s exactly what the rest of the book is about.

Although we are, for the sake of simplicity, discussing the appeals process as if a single judge were deciding the case, federal appellate cases are typically decided by a panel of three judges. One judge writes the majority opinion, and the other two either join that opinion or write separate opinions of their own, either in concurrence or dissent.

By contrast, if the patient tells the psychiatrist about someone whom the patient has already murdered, confidentiality remains intact (Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, 1976 ).

- Kerridge, I., Lowe, M., & Stewart, C. (2013). Ethics and law for the health professions (4th ed.). Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

- Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, 17 Cal. 3d 425, 551 P.2d 334, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14 (Cal. 1976).

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

- Cite this Page Scher S, Kozlowska K. Rethinking Health Care Ethics [Internet]. Singapore: Palgrave Pivot; 2018. Chapter 5, The Elusiveness of Closure. 2018 Aug 3. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-0830-7_5

- PDF version of this page (200K)

- PDF version of this title (1.6M)

In this Page

Recent activity.

- The Elusiveness of Closure - Rethinking Health Care Ethics The Elusiveness of Closure - Rethinking Health Care Ethics

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

A Framework for Ethical Decision Making

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Ethics Resources

This document is designed as an introduction to thinking ethically. Read more about what the framework can (and cannot) do .

We all have an image of our better selves—of how we are when we act ethically or are “at our best.” We probably also have an image of what an ethical community, an ethical business, an ethical government, or an ethical society should be. Ethics really has to do with all these levels—acting ethically as individuals, creating ethical organizations and governments, and making our society as a whole more ethical in the way it treats everyone.

What is Ethics?

Ethics refers to standards and practices that tell us how human beings ought to act in the many situations in which they find themselves—as friends, parents, children, citizens, businesspeople, professionals, and so on. Ethics is also concerned with our character. It requires knowledge, skills, and habits.

It is helpful to identify what ethics is NOT:

- Ethics is not the same as feelings . Feelings do provide important information for our ethical choices. However, while some people have highly developed habits that make them feel bad when they do something wrong, others feel good even though they are doing something wrong. And, often, our feelings will tell us that it is uncomfortable to do the right thing if it is difficult.

- Ethics is not the same as religion . Many people are not religious but act ethically, and some religious people act unethically. Religious traditions can, however, develop and advocate for high ethical standards, such as the Golden Rule.

- Ethics is not the same thing as following the law. A good system of law does incorporate many ethical standards, but law can deviate from what is ethical. Law can become ethically corrupt—a function of power alone and designed to serve the interests of narrow groups. Law may also have a difficult time designing or enforcing standards in some important areas and may be slow to address new problems.

- Ethics is not the same as following culturally accepted norms . Cultures can include both ethical and unethical customs, expectations, and behaviors. While assessing norms, it is important to recognize how one’s ethical views can be limited by one’s own cultural perspective or background, alongside being culturally sensitive to others.

- Ethics is not science . Social and natural science can provide important data to help us make better and more informed ethical choices. But science alone does not tell us what we ought to do. Some things may be scientifically or technologically possible and yet unethical to develop and deploy.

Six Ethical Lenses

If our ethical decision-making is not solely based on feelings, religion, law, accepted social practice, or science, then on what basis can we decide between right and wrong, good and bad? Many philosophers, ethicists, and theologians have helped us answer this critical question. They have suggested a variety of different lenses that help us perceive ethical dimensions. Here are six of them:

The Rights Lens

Some suggest that the ethical action is the one that best protects and respects the moral rights of those affected. This approach starts from the belief that humans have a dignity based on their human nature per se or on their ability to choose freely what they do with their lives. On the basis of such dignity, they have a right to be treated as ends in themselves and not merely as means to other ends. The list of moral rights—including the rights to make one's own choices about what kind of life to lead, to be told the truth, not to be injured, to a degree of privacy, and so on—is widely debated; some argue that non-humans have rights, too. Rights are also often understood as implying duties—in particular, the duty to respect others' rights and dignity.

( For further elaboration on the rights lens, please see our essay, “Rights.” )

The Justice Lens

Justice is the idea that each person should be given their due, and what people are due is often interpreted as fair or equal treatment. Equal treatment implies that people should be treated as equals according to some defensible standard such as merit or need, but not necessarily that everyone should be treated in the exact same way in every respect. There are different types of justice that address what people are due in various contexts. These include social justice (structuring the basic institutions of society), distributive justice (distributing benefits and burdens), corrective justice (repairing past injustices), retributive justice (determining how to appropriately punish wrongdoers), and restorative or transformational justice (restoring relationships or transforming social structures as an alternative to criminal punishment).

( For further elaboration on the justice lens, please see our essay, “Justice and Fairness.” )

The Utilitarian Lens

Some ethicists begin by asking, “How will this action impact everyone affected?”—emphasizing the consequences of our actions. Utilitarianism, a results-based approach, says that the ethical action is the one that produces the greatest balance of good over harm for as many stakeholders as possible. It requires an accurate determination of the likelihood of a particular result and its impact. For example, the ethical corporate action, then, is the one that produces the greatest good and does the least harm for all who are affected—customers, employees, shareholders, the community, and the environment. Cost/benefit analysis is another consequentialist approach.

( For further elaboration on the utilitarian lens, please see our essay, “Calculating Consequences.” )

The Common Good Lens

According to the common good approach, life in community is a good in itself and our actions should contribute to that life. This approach suggests that the interlocking relationships of society are the basis of ethical reasoning and that respect and compassion for all others—especially the vulnerable—are requirements of such reasoning. This approach also calls attention to the common conditions that are important to the welfare of everyone—such as clean air and water, a system of laws, effective police and fire departments, health care, a public educational system, or even public recreational areas. Unlike the utilitarian lens, which sums up and aggregates goods for every individual, the common good lens highlights mutual concern for the shared interests of all members of a community.

( For further elaboration on the common good lens, please see our essay, “The Common Good.” )

The Virtue Lens

A very ancient approach to ethics argues that ethical actions ought to be consistent with certain ideal virtues that provide for the full development of our humanity. These virtues are dispositions and habits that enable us to act according to the highest potential of our character and on behalf of values like truth and beauty. Honesty, courage, compassion, generosity, tolerance, love, fidelity, integrity, fairness, self-control, and prudence are all examples of virtues. Virtue ethics asks of any action, “What kind of person will I become if I do this?” or “Is this action consistent with my acting at my best?”

( For further elaboration on the virtue lens, please see our essay, “Ethics and Virtue.” )

The Care Ethics Lens

Care ethics is rooted in relationships and in the need to listen and respond to individuals in their specific circumstances, rather than merely following rules or calculating utility. It privileges the flourishing of embodied individuals in their relationships and values interdependence, not just independence. It relies on empathy to gain a deep appreciation of the interest, feelings, and viewpoints of each stakeholder, employing care, kindness, compassion, generosity, and a concern for others to resolve ethical conflicts. Care ethics holds that options for resolution must account for the relationships, concerns, and feelings of all stakeholders. Focusing on connecting intimate interpersonal duties to societal duties, an ethics of care might counsel, for example, a more holistic approach to public health policy that considers food security, transportation access, fair wages, housing support, and environmental protection alongside physical health.

( For further elaboration on the care ethics lens, please see our essay, “Care Ethics.” )

Using the Lenses

Each of the lenses introduced above helps us determine what standards of behavior and character traits can be considered right and good. There are still problems to be solved, however.

The first problem is that we may not agree on the content of some of these specific lenses. For example, we may not all agree on the same set of human and civil rights. We may not agree on what constitutes the common good. We may not even agree on what is a good and what is a harm.

The second problem is that the different lenses may lead to different answers to the question “What is ethical?” Nonetheless, each one gives us important insights in the process of deciding what is ethical in a particular circumstance.

Making Decisions

Making good ethical decisions requires a trained sensitivity to ethical issues and a practiced method for exploring the ethical aspects of a decision and weighing the considerations that should impact our choice of a course of action. Having a method for ethical decision-making is essential. When practiced regularly, the method becomes so familiar that we work through it automatically without consulting the specific steps.

The more novel and difficult the ethical choice we face, the more we need to rely on discussion and dialogue with others about the dilemma. Only by careful exploration of the problem, aided by the insights and different perspectives of others, can we make good ethical choices in such situations.

The following framework for ethical decision-making is intended to serve as a practical tool for exploring ethical dilemmas and identifying ethical courses of action.

Identify the Ethical Issues

- Could this decision or situation be damaging to someone or to some group, or unevenly beneficial to people? Does this decision involve a choice between a good and bad alternative, or perhaps between two “goods” or between two “bads”?

- Is this issue about more than solely what is legal or what is most efficient? If so, how?

Get the Facts

- What are the relevant facts of the case? What facts are not known? Can I learn more about the situation? Do I know enough to make a decision?

- What individuals and groups have an important stake in the outcome? Are the concerns of some of those individuals or groups more important? Why?

- What are the options for acting? Have all the relevant persons and groups been consulted? Have I identified creative options?

Evaluate Alternative Actions

- Evaluate the options by asking the following questions:

- Which option best respects the rights of all who have a stake? (The Rights Lens)

- Which option treats people fairly, giving them each what they are due? (The Justice Lens)

- Which option will produce the most good and do the least harm for as many stakeholders as possible? (The Utilitarian Lens)

- Which option best serves the community as a whole, not just some members? (The Common Good Lens)

- Which option leads me to act as the sort of person I want to be? (The Virtue Lens)

- Which option appropriately takes into account the relationships, concerns, and feelings of all stakeholders? (The Care Ethics Lens)

Choose an Option for Action and Test It

- After an evaluation using all of these lenses, which option best addresses the situation?

- If I told someone I respect (or a public audience) which option I have chosen, what would they say?

- How can my decision be implemented with the greatest care and attention to the concerns of all stakeholders?

Implement Your Decision and Reflect on the Outcome

- How did my decision turn out, and what have I learned from this specific situation? What (if any) follow-up actions should I take?

This framework for thinking ethically is the product of dialogue and debate at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Primary contributors include Manuel Velasquez, Dennis Moberg, Michael J. Meyer, Thomas Shanks, Margaret R. McLean, David DeCosse, Claire André, Kirk O. Hanson, Irina Raicu, and Jonathan Kwan. It was last revised on November 5, 2021.

- Creating Environments Conducive to Social Interaction

Thinking Ethically: A Framework for Moral Decision Making

- Developing a Positive Climate with Trust and Respect

- Developing Self-Esteem, Confidence, Resiliency, and Mindset

- Developing Ability to Consider Different Perspectives

- Developing Tools and Techniques Useful in Social Problem-Solving

- Leadership Problem-Solving Model

- A Problem-Solving Model for Improving Student Achievement

- Six-Step Problem-Solving Model

- Hurson’s Productive Thinking Model: Solving Problems Creatively

- The Power of Storytelling and Play

- Creative Documentation & Assessment

- Materials for Use in Creating “Third Party” Solution Scenarios

- Resources for Connecting Schools to Communities

- Resources for Enabling Students

These 5 approaches and their history can be found at:

Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v7n1/thinking.html

Promoting Ethical Discussions and Decision Making in a Human Service Agency

- Research Article

- Published: 28 July 2020

- Volume 13 , pages 905–913, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Linda A. LeBlanc ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7711-0978 1 ,

- Olivia M. Onofrio 2 ,

- Amber L. Valentino 2 &

- Joshua D. Sleeper 2

1899 Accesses

15 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

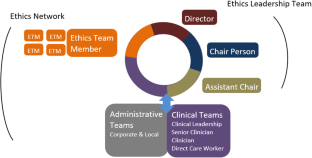

This article describes the development of a system, the Ethics Network, designed to promote discussion of ethical issues in a human services organization. The system includes several core components, including people (e.g., leaders, ambassadors), tools (e.g., hotline, training modules), and resources (e.g., monthly talking points). Data from 6 years of hotline submissions were analyzed to identify the most common concerns, and the data were compared to the pattern of violation notices submitted to the Behavior Analyst Certification Board. Recommendations are provided for creating similar systems in other organizations.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Ethics and Human Resource Management

Promoting Ethical Discussions and Decision Making in a Human Services Agency: Updates to LeBlanc et al.’s (2020) Ethics Network

Amber L. Valentino, Roxanne I. Gayle, … Ashley M. Fuhrman

“Systematizing” Ethics Consultation Services

Courtenay R. Bruce, Margot M. Eves, … Mary A. Majumder

Arya, K., Margaryan, A., & Collis, B. (2003). Culturally sensitive problem solving activities for multi-national corporations. TechTrends, 47 , 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02763283 .

Article Google Scholar

Bailey, J. S., & Burch, M. R. (2016). Ethics for behavior analysts (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts . Littleton, CO: Author.

Google Scholar

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2018). A summary of ethics violations and code-enforcement activities: 2016–2017 . Littleton, CO: Author.

Brodhead, M. T., & Higbee, T. S. (2012). Teaching and maintaining ethical behavior in a professional organization. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 5 (2), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391827 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brodhead, M. T., Quigley, S. P., & Cox, D. J. (2018). How to identify ethical practices in organizations prior to employment. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 11 (2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-018-0235-y .

Glago, K., Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (2009). Improving problem solving of elementary students with mild disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 30 (6), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932508324394 .

LeBlanc, L. A., Sellers, T. P., & Alai, S. (2020). Building and sustaining meaningful and effective relationships as a supervisor and mentor. Cornwall on Hudson, NY: Sloan Publishing.

O'Leary, P. N., Miller, M. M., Olive, M. L., & Kelly, A. N. (2015). Blurred lines: ethical implications of social media for behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10 (1), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-014-0033-0

Rosenberg, N. E., & Schwartz, I. S. (2019). Guidance or compliance: What makes an ethical behavior analyst? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12 (2), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-018-00287-5 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Smith, C. M. (2005). Origin and uses of primum non nocere—above all, do no harm! Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 45 (4), 371–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091270004273680 .

Smith, S. W., Lochman, J. E., & Daunic, A. P. (2005). Managing aggression using cognitive-behavioral interventions: State of the practice and future. Behavioral Disorders, 30 (3), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874290503000307 .

Zur, O. (2007). Boundaries in psychotherapy: Ethical and clinical explorations . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Download references

Author Note

The Ethics Network was developed as part of the Clinical Standards Initiative at Trumpet Behavioral Health. The authors thank Allie Kane, Heather Loeb, Jessie Mitchell, Kirstin Powers, Sarah Kristiansen, and Michael Wright, who each served as assistant chair, chair, or director of the Ethics Network.

No funding was associated with the current study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

LeBlanc Behavioral Consulting, Golden, CO, USA

Linda A. LeBlanc

Trumpet Behavioral Health, 390 Union Blvd., Suite #300, Lakewood, CO, 80228, USA

Olivia M. Onofrio, Amber L. Valentino & Joshua D. Sleeper

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Amber L. Valentino .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflict of interest regarding this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Additional information

Editor’s Note

Although some agencies are busy changing the format of their service delivery and supervision of staff, we know that other agencies are not currently providing services and that leaders in these agencies now have unexpected time to reflect on how to improve quality of care when they return to the workplace. We have two outstanding peer-reviewed articles that we believe can support leaders who seek to improve ethical care in their agencies. The article by David Cox provides a detailed description of how agencies can develop an ethics committee. The article by Linda LeBlanc and colleagues provides a demonstration of an ethics committee and shares data on the most frequently occurring ethical concerns reported by their staff. Leaders working in agencies that do not currently have an ethics coordinator or an ethics committee can initiate dialogue with their staff about the value and process of developing an ethics committee to be responsive to staff, parent, and client concerns. Together, these articles can support the development of ethics committees to increase adherence to ethical codes and to promote ethical behavior in the workplace.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Information Completed by Submitters on the Ethics Hotline Submission Form

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

LeBlanc, L.A., Onofrio, O.M., Valentino, A.L. et al. Promoting Ethical Discussions and Decision Making in a Human Service Agency. Behav Analysis Practice 13 , 905–913 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00454-7

Download citation

Published : 28 July 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00454-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board

- Clinical standards

- Compliance code

- Organizational system

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law