Advertisement

Burden of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Indian Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Original Article

- Published: 16 January 2022

- Volume 89 , pages 570–578, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Anil Chauhan 1 na1 ,

- Jitendra Kumar Sahu 2 na1 ,

- Manvi Singh 3 ,

- Nishant Jaiswal 1 ,

- Amit Agarwal 1 ,

- Singanamalla Bhanudeep 2 ,

- Pranita Pradhan 3 &

- Meenu Singh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2224-2743 1 , 3 , 4

919 Accesses

6 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

To determine the pooled prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in Indian children.

The searching of published literature was conducted in different databases (PubMed, Ovid SP, and EMBASE). The authors also tried to acquire information from the unpublished literature about the prevalence of ADHD. A screening was done to include eligible original studies, community or school-based, cross-sectional or cohort, reporting the prevalence of ADHD in children aged ≤ 18 y in India. Retrieved data were analyzed using STATA MP12 (Texas College station).

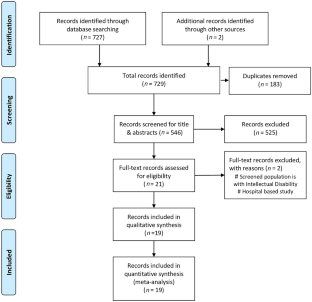

Of 729 studies retrieved by searching different databases, 183 studies were removed as duplicates, and 546 titles and abstracts were screened. After screening, 19 studies were included for quantitative analysis. Subgroup analysis was conducted with respect to their setting (school-based/community-based). Fifteen studies performed in a school-based setting showed 75.1 (95% CI 56.0–94.1) pooled prevalence of ADHD per 1000 children of 4–19 y of age. In community-based settings, the pooled prevalence per 1000 children surveyed was 18.6 (95% CI 8.8–28.4). The overall pooled prevalence of ADHD was observed as 63.2 (95% CI 49.2–77.1) in 1000 children surveyed. Significant heterogeneity was observed in the systemic review.

Conclusions

ADHD accounts for a significant health burden, and understanding its burden is crucial for effective health policy-making for educational intervention and rehabilitation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

An overview on neurobiology and therapeutics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Bruna Santos da Silva, Eugenio Horacio Grevet, … Claiton Henrique Dotto Bau

Understanding and Supporting Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in the Primary School Classroom: Perspectives of Children with ADHD and their Teachers

Emily McDougal, Claire Tai, … Sinéad M. Rhodes

Neurodiversity in higher education: a narrative synthesis

Lynn Clouder, Mehmet Karakus, … Patricia Rojo

Arlington VA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/DSM/APA_DSM-5-ADHD.pdf . Accessed on 25th Jan 2021.

Dulcan M. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Academy of child &Adolescent Psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:85S–121S.

Polanczyk G, De Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and meta regression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:942–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Thomas R, Sanders S, Doust J, Beller E, Glasziou P. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e994-1001.

Bruchmüller K, Margraf J, Schneider S. Is ADHD diagnosed in accord with diagnostic criteria? overdiagnosis and influence of client gender on diagnosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:128–38.

Batstra L, Hadders-Algra M, Nieweg E, Van Tol D, Pijl SJ, Frances A. Childhood emotional and behavioural problems: reducing overdiagnosis without risking undertreatment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:492–4.

Charach A, Dashti B, Carson P, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effectiveness of treatment in at-risk pre-schoolers; long-term effectiveness in all ages; and variability in prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment. 2011. Available at: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm . Accessed on 7th June 2013.

Batstra L, Frances A. Holding the line against diagnostic inflation in psychiatry. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81:5–10

Boyle MH. Guidelines for evaluating prevalence studies. Evid Based Mental Health. 1998;1:37–9.

Article Google Scholar

Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, Roberts JG, Stratford PW. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can. 1998;19:170–6.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Sharma P, Gupta RK, Banal R, et al. Prevalence and correlates of Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) risk factors among school children in a rural area of North India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:115–8.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Catherine TG, Robert NG, Mala KK, Kanniammal C, Arullapan J. Assessment of prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among school children in selected schools. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:232–7.

Suthar N, Garg N, VermaK, Singhal A, Singh H, Baniya G. Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in primary school children: a cross-sectional study. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2018;14:74–88

Ghosh P, Choudhury HA, Victor R. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among primary school children in Cachar, Assam, North-East India. Open J Psychiatry Allied Sci. 2018;9:130–5.

Arora NK, Nair MKC, Gulati S, et al. Neurodevelopmental disorders in children aged 2–9 years: population-based burden estimates across five regions in India. PLoS Med. 2018;15.

Ramya HS, Goutham AS, Lakshmi V Pandit. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in school going children aged between 5–12 years in Bengaluru. Curr Pediatr Res. 2017;21:321–326

Gupta A. Prevalence and symptomatology of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in school children. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:S718. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-977x(16)31862-4 .

Mannapur R, MunirathnamG, Hyarada M, Bylagoudar SSS. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among urban school children. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2016;3:240–2.

Jaisoorya TS, Beena KV, Beena M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported ADHD symptoms in children attending school in India. J Atten Disord. 2020;24:1711–5.

CAS Google Scholar

Manjunath R, Kishor M, Kulkarni P, Shrinivasa BM, Sathyamurthy S. Magnitude of attention deficit hyper kinetic disorder among school children of Mysore city. International Neuropsychiatric Disease Journal. 2016;6:1–7.

Juneja M, Sairam S, Jain R. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescent school children. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:151–2.

Venkata JA, Panicker AS. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in primary school children. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:338–42.

Patil RN, Nagaonkar SN, Shah NB, Bhat TS. A cross-sectional study of common psychiatric morbidity in children aged 5 to 14 years in an urban slum. J Family Med Prim Care. 2013;2:164–8.

Ajinkya S, Kaur D, Gursale A, Jadhav P. Prevalence of parent-rated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated parent-related factors in primary school children of Navi Mumbai- a school based study. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:207–10.

Suvarna BS, Kamath A. Prevalence of attention deficit disorder among preschool age children. Nepal Med Coll J. 2009;11:1–4.

Pillai A, Patel V, Cardozo P, Goodman R, Weiss HA, Andrew G. Non-traditional lifestyles and prevalence of mental disorders in adolescents in Goa. India Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:45–51.

Srinath S, Girimaji SC, Gururaj G, et al. Epidemiological study of child & adolescent psychiatric disorders in urban & rural areas of Bangalore. India Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:67–79.

PubMed Google Scholar

Malhotra S, Kohli A, Arun P. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in school children in Chandigarh. India Indian J Med Res. 2002;116:21–8.

Gada M. A study of prevalence and pattern of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity in primary school children. Indian J Psychiatry. 1987;29:113–8.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) Advanced Center of Evidence Based Child Health, PGIMER, Chandigarh for supporting this systematic review .

ICMR Advanced Centre for Evidence Based Child Health Phase 2, PGIMER, Chandigarh (Grant reference No 5/7/1668/CH/CAR/2019-RBMCH).

Author information

Anil Chauhan and Jitendra Kumar Sahu have equal contribution to this manuscript and share the first authorship.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Telemedicine, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Evidence Based Health Informatics Unit, Regional Resource Centre, Chandigarh, India

Anil Chauhan, Nishant Jaiswal, Amit Agarwal & Meenu Singh

Pediatric Neurology Unit, Department of Pediatrics, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India

Jitendra Kumar Sahu & Singanamalla Bhanudeep

ICMR Advanced Center for Evidence Based Child Health, Department of Pediatrics, PGIMER, Chandigarh, 160012, India

Manvi Singh, Pranita Pradhan & Meenu Singh

Department of Pediatrics, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India

Meenu Singh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The studies searched through different databases were independently screened for their titles and abstracts by AC, SB, and JKS. The full texts of eligible studies so identified were further analyzed or screened by AC and MaS for their inclusion. PP contributed in searching the literature for this systematic review. Any discrepancies were resolved by consulting MS. AA, AC, JKS, and MaS extracted data independently from eligible studies. AC and JKS independently assessed the quality of the included studies by using a validated quality assessment tool. The data were analyzed by NJ, AC, and AA using “STATA MP12 (Texas, College Station).” MS is the guarantor for this paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Meenu Singh .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Chauhan, A., Sahu, J.K., Singh, M. et al. Burden of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Indian Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Indian J Pediatr 89 , 570–578 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-021-03999-9

Download citation

Received : 18 March 2021

Accepted : 19 August 2021

Published : 16 January 2022

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-021-03999-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Hyperactive disorder

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

ADHD research in India: A narrative review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research (JIPMER), Puducherry 605006, India. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research (JIPMER), Puducherry 605006, India. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 3 Room No. 4091, Department of Psychiatry, 4th Floor Academic Block, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110029, India. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 4 Department of Psychiatry, 4th Floor Academic Block, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110029, India. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 5 Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, India. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 6 Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, India. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 28709018

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.07.022

Introduction: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with no clear etiopathogenesis. Owing to unique socio cultural milieu of India, it is worthwhile reviewing research on ADHD from India and comparing findings with global research. Thereby, we attempted to provide a comprehensive overview of research on ADHD from India.

Methods: A boolean search of articles published in English from September 1966 to January 2017 on electronic search engines Google Scholar, PubMed, IndMED, MedIND, using the search terms "ADHD", "Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder", "Hyperactivity" ,"Child psychiatry", "Hyperkinetic disorder", "Attention Deficit Disorder", "India"was carried out and peer - reviewed studies conducted among human subjects in India were included for review. Case reports, animal studies, previous reviews were excluded from the current review.

Results: Results of 73 studies found eligible for the review were organized into broad themes such as epidemiology, etiology, course and follow up, clinical profile and comorbidity, assessment /biomarkers, intervention/treatment parameters, pathways to care and knowledge and attitude towards ADHD.

Discussion: There was a gap noted in research from India in the domains of biomarkers, course and follow up and non-pharmacological intervention. The prevalence of ADHD as well as comorbidity of Bipolar Disorder was comparatively lower compared to western studies. The studies found unique to India include comparing the effect of allopathic intervention with Ayurvedic intervention, yoga as a non pharmacological intervention. There is a need for studies from India on biomarkers, studies with prospective research design, larger sample size and with matched controls.

Keywords: ADHD; Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; India; Research; Trends.

Copyright © 2017 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity* / diagnosis

- Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity* / epidemiology

- Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity* / therapy

- Biomedical Research* / trends

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,954,836 articles, preprints and more)

- Available from publisher site using DOI. A subscription may be required. Full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Burden of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Indian Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

Author information, affiliations.

- Chauhan A 1

- Jaiswal N 1

- Agarwal A 1

- Singh M 1, 3

- Bhanudeep S 2

- Pradhan P 3

ORCIDs linked to this article

- Sahu JK | 0000-0001-5194-9951

- Singh M | 0000-0002-2224-2743

Indian Journal of Pediatrics , 16 Jan 2022 , 89(6): 570-578 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-021-03999-9 PMID: 35034274

Abstract

Conclusions, full text links .

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-021-03999-9

References

Articles referenced by this article (5)

Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem.

Loney PL , Chambers LW , Bennett KJ , Roberts JG , Stratford PW

Chronic Dis Can, (4):170-176 1998

MED: 10029513

Prevalence of attention deficit disorder among preschool age children.

Suvarna BS , Kamath A

Nepal Med Coll J, (1):1-4 2009

MED: 19769227

Epidemiological study of child & adolescent psychiatric disorders in urban & rural areas of Bangalore, India.

Srinath S , Girimaji SC , Gururaj G , Seshadri S , Subbakrishna DK , Bhola P , Kumar N

Indian J Med Res, (1):67-79 2005

MED: 16106093

Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in school children in Chandigarh, India.

Malhotra S , Kohli A , Arun P

Indian J Med Res, 21-28 2002

MED: 12514974

A study of prevalence and pattern of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity in primary school children.

Indian J Psychiatry, (2):113-118 1987

MED: 21927223

Citations & impact

Impact metrics, citations of article over time, article citations, similar articles .

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

Open Research Library Search query Search var _gaq = _gaq || []; _gaq.push(['_setAccount', 'UA-5266663-1']); _gaq.push(['_trackPageview']); (function() { var ga = document.createElement('script'); ga.type = 'text/javascript'; ga.async = true; ga.src = ('https:' == document.location.protocol ? 'https://ssl' : 'http://www') + '.google-analytics.com/ga.js'; var s = document.getElementsByTagName('script')[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(ga, s); })(); Skip navigation jQuery(document).ready(function() { jQuery('#gw-nav a[data-mega-menu-trigger], #gw-megas a[data-mega-menu-trigger]').on('click', function () { showMegaMenu($(this).attr('data-mega-menu-trigger')); return false; }); }); Home About Contribute Publishing Policy Copyright Contact Statistics My Open Research close My Open Research

Your list of unfinished submissions or submissions in the workflow.

- Edit Profile

- Receive email updates

- Search ANU web, staff & maps

- Search current site content

ADHD in Indian schools : a study of students with ADHD and their teachers in twenty primary schools in New Delhi and Bangalore

- Export Reference to BibTeX

- Export Reference to EndNote XML

Altmetric Citations

Sethi, Nandini

Description

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) has been identified as a worldwide problem. However, questions remain regarding its expression, recognition and management in different cultures. In India, ADHD is a very under-researched topic. Only four studies could be found in the research literature, two of which reported high prevalence rates. This thesis presents two studies, a broad pilot study and an investigation focussed on teachers and their experience with ADHD in their classes. The ... [Show more] pilot study was conducted to gain initial insights into the awareness, recognition, diagnosis and management of ADHD in India. Key people in the child's ecological system (teachers, principals, parents, mental health professionals and school counselors) were chosen to be interviewed for this purpose. These "stakeholders" commented on a wide range of issues, based on their involvement with children with ADHD and their ability to influence the children's outcomes, either directly or indirectly. The findings indicated that in many cases, ADHD was probably left unrecognized. In addition, the impression was gained that many schools were not supporting these children adequately because of limited teacher knowledge, lack of well, developed referral and intervention systems and limited resources. The second study was conducted to investigate more systematically a number of issues related to ADHD, this time with a narrower focus on children and their teachers. One hundred and ten teachers reported on 110 children with ADHD symptoms in their classrooms as well as 110 comparison children whom they regarded as "average" children. Teacher identified children with ADHD symptoms displayed significantly more inattentive, hyperactive and/or behaviour problems than "average" children in the same classrooms. However, in spite of being significantly more symptomatic, fewer than one fourth had received a diagnosis of ADHD and only 7.2% were on medication. In addition, only 10% of children had Individual Education Plans. This extended impressions gained in the pilot study that this may be an underserviced population in India. An analysis of the demandingness of these children, teacher stress, burnout and efficacy was conducted. Not only were these children more demanding, but they also stressed teachers more than comparison average children. The sheer frequency of inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity and/or behaviour problems played a major role in stressing teachers. However, stress associated with children with teacher identified ADHD was not found to be uniquely predictive of teacher burnout or lowered self-efficacy. Investigation of the supports for teachers in the schools revealed that teachers in Indian schools wanted more support with children with ADHD, including professional development and the school's support and understanding. This research brings into focus and highlights the needs of children with ADHD and their teachers. These children need to be adequately diagnosed and managed in schools, which does not appear to be the case at the moment. The current processes of recognition and intervention in schools have the potential to leave many children undiagnosed and/or not supported. This research also brings into focus the perspectives of teachers and the need to support them. Lastly, the results make a case for professionals and school personnel to invest in children with ADHD to ensure that Indian schools will be truly inclusive.

Items in Open Research are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

Updated: 17 November 2022 / Responsible Officer: University Librarian / Page Contact: Library Systems & Web Coordinator

- Contact ANU

- Freedom of Information

+61 2 6125 5111 The Australian National University, Canberra CRICOS Provider : 00120C ABN : 52 234 063 906

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychiatry

The lived experiences of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A rapid review of qualitative evidence

Callie m. ginapp.

1 Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Grace Macdonald-Gagnon

2 Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

Gustavo A. Angarita

3 Connecticut Mental Health Center, New Haven, CT, United States

Krysten W. Bold

Marc n. potenza.

4 Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, Wethersfield, CT, United States

5 Child Study Center, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

6 Department of Neuroscience, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

7 Wu Tsai Institute, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Associated Data

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common condition that frequently persists into adulthood, although research and diagnostic criteria are focused on how the condition presents in children. We aimed to review qualitative research on lived experiences of adults with ADHD to characterize potential ADHD symptomatology in adulthood and provide perspectives on how needs might be better met. We searched three databases for qualitative studies on ADHD. Studies ( n = 35) in English that included data on the lived experiences of adults with ADHD were included. These studies covered experiences of receiving a diagnosis as an adult, symptomatology of adult ADHD, skills used to adapt to these symptoms, relationships between ADHD and substance use, patients’ self-perceptions, and participants’ experiences interacting with society. Many of the ADHD symptoms reported in these studies had overlap with other psychiatric conditions and may contribute to misdiagnosis and delays in diagnosis. Understanding symptomatology of ADHD in adults may inform future diagnostic criteria and guide interventions to improve quality of life.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has an estimated prevalence of 7% among adults globally ( 1 ). ADHD has historically been considered a disorder of childhood; however, 40–50% of children with ADHD may meet criteria into adulthood ( 2 ). Diagnostic criteria for ADHD include symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness present since childhood ( 3 ). These criteria are largely based on presentations in children, although diagnostic criteria have changed over time to better but not completely encompass considerations of experiences of adults ( 3 , 4 ).

Although adult ADHD is highly treatable with stimulant medication ( 5 ), adults with ADHD often have unmet needs. Substance use disorders (SUDs) are approximately 2.5-fold more prevalent among adults with versus without ADHD ( 6 , 7 ). Adults with ADHD are particularly likely to be incarcerated, with 26% of people in prison having ADHD ( 8 ). As diagnosis of ADHD has increased considerably in recent decades ( 9 ), there are likely many adults with ADHD who were not originally diagnosed as children. In more recent years, ADHD is still frequently underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed as other psychiatric conditions such as mood or personality disorders ( 10 ). Even when patients are diagnosed with ADHD as children, many patients lose access to resources when transitioning from child to adult health services ( 11 ) which may contribute to less than half of people with ADHD adhering to stimulant medication ( 12 ).

Non-pharmacological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) have shown promise with helping adults manage their ADHD symptoms, although such symptoms are not completely ameliorated by therapy ( 13 – 15 ). A more thorough understanding of the symptoms adults with ADHD experience and the effects that these symptoms have on their lives may allow for more efficacious or targeted therapeutic interventions.

Qualitative research may provide insight into lived experiences, and findings from such studies may direct future research into potential symptoms and therapeutic interventions. The aim of this review is to describe the current qualitative literature on the lived experiences of adults with ADHD. This review may provide insight into the symptomatology of adult ADHD, identify areas where patient needs could be better met, and define gaps in understanding.

Search strategy

Using rapid review methodology ( 16 ), PubMed, PsychInfo, and Embase were searched on October 11th, 2021 with no date restrictions. The search terms included “ADHD” and related terms as well as “qualitative methods” present in the titles or abstracts. The full search ( Supplementary Appendix 1 ) was conducted with the help of a clinical librarian. The search yielded 417 articles which were uploaded to Endnote X9 where 111 duplicates were removed. The remaining 307 articles were uploaded to Covidence Systematic Review Management Software for screening, with one additional duplicate removed. The search also yielded a previous review on the lived experiences of adults with ADHD ( 17 ). The ten articles present in this review were also uploaded to Covidence where two duplicates were removed resulting in 314 unique articles.

Study selection

Studies reporting original peer-reviewed qualitative data on the lived experience of adults with ADHD, including mixed-methods studies, were eligible for inclusion. “Adult” was defined as being 18 years of age or older; studies that included adolescent and young adult participants were only included if results were reported separately by age. Studies that included some participants without ADHD were included if results were reported separately by diagnosis. Any studies with adult participants who were exclusively reflecting on their childhood experiences with ADHD were considered outside this study’s scope, as were studies on family members, medical providers, or other groups commenting on adults with ADHD. Articles could be from any country, but needed to have been published in English. Individual case studies were not included due to concerns with generalizability.

Twenty percent of titles and abstracts were screened by two reviewers for meeting the inclusion criteria. Studies were not initially excluded based on participants’ ages as many titles and abstracts did not specify age. One reviewer screened the remaining abstracts; a second reviewer screened all excluded abstracts. For full-text screening, ten articles were screened by both reviewers to ensure consistency. One reviewer screened the remaining articles; a second reviewer screened all excluded articles.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal was completed by one reviewer using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research ( 18 ). Half of included studies did not state philosophical perspectives, two-thirds did not locate researchers culturally or theoretically, nearly one-third did not include specific information about ethics approval, and only two studies commented on reflexivity ( Supplementary Appendix 2 ). Given the varied quality appraisal results and the small body of literature, all studies were included regardless of methodological rigor.

Data extraction

Data extracted included general study characteristics and methodology, participant characteristics (sample size, demographics, and country of residence), study aims, and text excerpts of qualitative results. Study characteristics were entered into a Google Sheets document. PDFs of all studies were uploaded into NVivo 12, and results sections were coded using grounded theory ( 19 ). One reviewer extracted and coded data; a second reviewed extracted data for thematic consistency.

Study characteristics

One-hundred-and-seventy-three articles were deemed relevant in title and abstract screening. Of these, 35 were included after the full-text review ( Figure 1 ). Articles were published between 2005 and 2021, and methodology mostly consisted of individual interviews (91%), with other studies utilizing focus groups (14%). Eight studies focused on young adults (18–35 years), and three were specific to older adults (>50 years). Two had exclusively male participants, and three had exclusively female participants. Nineteen were conducted in Europe, nine in North America, and three in Asia. No studies included participants from Africa, South America, or Oceania. In six studies, participants had current or prior SUDs, six studies focused on college students, four included participants diagnosed in adulthood, and two included highly educated/successful participants ( Table 1 ).

PRISMA flow diagram showing the search strategy for identifying qualitative studies on the lived experience of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Article characteristics of included studies.

1 Ages not reported consistently across studies.

2 Substance use disorder.

An overview of the identified themes is described in Figure 2 , and Table 2 provides a summary of main findings. Several of the themes overlap with each other, and such areas are identified in the main text.

Schematic diagram of the domains of features linked to the lived experiences of adults with ADHD.

Summary of results.

Adult diagnosis

Assessment and diagnosis of adult ADHD were reported as laborious and included prior misdiagnoses ( 20 – 22 ), lack of psychiatric resources ( 23 ), and physicians’ stigma regarding adult ADHD ( 24 ). Participants were often diagnosed only after their children were diagnosed ( 23 , 24 ). However, after receiving a diagnosis, relief was commonly reported initially. Adults noted that receiving a diagnosis helped explain previously seemingly inexplicable symptoms and feelings of being different, and allowed for participants to blame themselves less for perceived shortcomings ( 24 – 31 ).

Identity changes were another reported finding after diagnosis, both positive and negative. Some participants reported experiencing existential questioning of their identities ( 25 , 26 ); others reported feeling increased levels of self-awareness ( 26 , 28 ). Some participants reported having initial doubts about the validity of their diagnoses ( 26 , 28 ). Some reported experiencing emotional turmoil and concerns about the future ( 25 , 26 , 29 ). A commonly reported late step involved acceptance, both of themselves and their diagnoses, sometimes coupled with increased interest in researching ADHD ( 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 32 ). A ubiquitous finding was participant regret that they had not been diagnosed earlier, largely because of the many years they had gone without understanding their condition or receiving treatment ( 22 , 24 , 26 – 30 ). In one study, participants who had been diagnosed as children had better emotional control and self-esteem ( 33 ). No studies reported participant regret about their ADHD diagnosis.

Symptomatology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity.

Consistent with current diagnostic conceptualizations, difficulties with attention and concentration were described. These difficulties hindered completion of daily life tasks at home, school, and work ( 24 , 27 , 28 , 32 , 34 – 37 ). Some participants reported not experiencing a pervasive deficit of attention, but rather only struggling when the topic was not of personal interest and could sustain attention on interesting tasks for long periods of time ( 33 , 38 – 42 ). Attention could be influenced by the environment; for example, attention worsened in distracting environments or improved in intense, stimulating environments ( 40 , 41 ).

Impulsivity was widely reported and reflected in risk-taking including reckless driving, unprotected sex, and extreme sports ( 20 , 24 , 28 , 33 , 36 , 43 ). Impulsive spending was noted ( 20 , 36 – 38 , 44 ). Impulsive speech (“blurting out”) was common and often led to strained interpersonal relationships ( 24 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 40 ).

Fewer studies described participants’ struggles with hyperactivity, such as with staying still or not being constantly busy ( 24 , 34 , 36 ). Hyperactivity was reported as an internal symptom by some participants, noted as inner feelings of restlessness ( 22 , 36 , 37 , 39 ), or described as resulting in excessive talking ( 36 ). This more subtle hyperactivity was mostly reported by women or older adults.

Chaos, lack of structure, and emotions

Living in chaos was often reported, whether involving internal feelings of being unsettled ( 28 ), or external aspects such as turbulent schedules or disorganized living spaces ( 22 , 24 , 27 , 36 ). Participants often struggled with maintaining structure in daily routines, resulting in irregular sleeping and eating, difficulty completing household tasks, and strained social lives ( 36 – 38 , 43 , 44 ). Increased autonomy in adulthood was often perceived as difficult to manage compared to more highly structured childhoods.

Although lacking from current diagnostic criteria, emotional dysregulation was often noted. Participants reported experiencing extreme emotional reactions to interpersonal conflicts such as terminations of romantic relationships or receiving negative feedback at work ( 24 , 34 , 38 , 40 ). Negative feelings of anxiety and agitation were common ( 22 , 24 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 38 , 44 ), as was difficulty with controlling, recognizing, naming, and managing emotions ( 30 , 40 , 41 , 44 ). One study noted that emotional lability has positive aspects since participants’ emotional highs were higher ( 45 ).

Positive aspects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Not all aspects of ADHD were perceived as negative. Impulsivity was reported by some as fun and spontaneous ( 26 , 37 , 45 ), struggles with attention were reported as promoting creativity and motivating focus on details ( 21 , 33 , 40 , 41 , 45 ), and hyperactivity was described as providing energy to pursue one’s passions ( 40 , 45 ). Learning to live with ADHD-related impairments was reported as promoting resilience and humanity ( 45 ), and increased tendencies to keep calm in chaotic settings ( 40 ). Ability to maintain focus for extended periods on topics of personal interest was sometimes seen as helpful, although unpredictable ( 33 ).

Adapting to symptoms

Coping skills.

Participants reported compensatory organizational strategies that increased structure in their daily lives. Creating regimented sleeping, eating, working, and relaxing schedules ( 30 , 35 , 42 , 44 , 46 ), and keeping to-do lists or using reminder apps ( 24 , 32 , 37 , 40 , 42 , 46 ) were frequently-reported strategies. Some participants reported thriving without formal structure while working from home since they were able to maintain daily routines and were free from distractions ( 34 ).

Participants reported being able to adjust their environment to best suit their needs, whether that be decreasing distracting stimulation ( 32 , 46 ) or cultivating a highly stressful and stimulating environment ( 39 ). Creating space for physical activity was reported as a helpful outlet for hyperactivity ( 24 , 33 , 39 , 43 , 46 ). Having awareness of their diagnosis allowed newly-diagnosed participants to attribute their symptoms to their disorder, thereby decreasing self-blame ( 24 , 26 , 32 ). In one study, participants engage in self-talk to modify their behavior ( 32 ). Participants reported implementing social skills to prevent interrupting others and adjusting their social circles to accommodate their symptoms ( 24 , 35 , 46 ).

Substance use was also described as a coping strategy, although there were also drawbacks associated with using substances. Such findings are discussed under “substance use.”

Stimulant medications were commonly used to help manage ADHD symptoms; participants reported that stimulants facilitated task prioritization, goal achievement, and productivity often to “life-changing” extents ( 22 , 24 – 27 , 29 , 32 , 35 , 40 , 46 – 48 ). Stimulants were sometimes reported as assisting with social and emotional functioning by promoting calmness ( 22 , 24 , 30 , 40 ). Some participants took their medications on an as-needed basis, choosing to take them only when they had much work ( 20 , 27 , 32 , 33 , 47 ). In one study, participants reported feeling pressured to sell their medication, and in another, participants reported increasing their dosages to stay up all night in order to better complete school work ( 27 , 47 ).

Participant ambivalence or hesitation to take stimulants was reported due to therapeutic and adverse effects. Reported adverse effects included “not feeling like oneself,” resulting in difficulties with socializing and creativity ( 22 , 27 , 35 , 40 , 47 ), somatic effects such as appetite suppression and insomnia ( 22 , 27 , 35 , 40 , 47 ), unpleasant emotions including irritability and numbness ( 35 , 40 , 47 ), and rebound symptoms and withdrawal side effects when the medications wore off ( 29 , 47 ).

Outside support

Studies noted participants adapting to living with their symptoms by receiving formal accommodations at work and school. Reported workplace accommodations included reduction of auditory distractions and bosses who would provide organizational advice or extra reminders about due dates ( 24 , 25 , 40 ). Reported accommodations in college consisted of separate testing environments and extra time on examinations. However, inaccessibility of disability offices, limited willingness of professors to comply with accommodations, and lack of participant engagement with accommodations due to not wanting to seem different resulted in many participants not utilizing such resources ( 27 , 32 ).

Individual therapy was reported as helpful for managing symptoms and acquiring self-knowledge, especially therapeutic interventions designed for ADHD and CBT ( 22 , 23 , 27 , 41 ). However, some participants reported minimal benefits from seeing therapists who did not specialize in ADHD, and CBT was reported to need improvement to be specially tailored to adults with ADHD such as being more engaging or being reframed as ADHD coaching ( 22 , 27 , 33 ). Community care workers added structure to some participants’ lives and aided with motivation in one study ( 42 ).

In some studies, participants expressed desires to be involved with support groups for adults with ADHD in order to learn new coping skills and find community, but not knowing where to access such services ( 28 , 40 ). Those who had participated in ADHD support or focus groups reported feeling validated and less isolated, as well leaving with improved strategies for symptom management ( 24 , 31 , 41 , 49 ). Support was also reported in personal relationships. Having a supportive partner often helped participants tremendously with organization and life tasks, especially for men married to women ( 24 , 43 ). A close friend or family member encouraging accountability and creating a sense of togetherness was viewed as advantageous ( 32 , 42 ).

Substance use and addiction

Reasons for substance use.

The SUDs were commonly reported among adults with ADHD and often seen as a form of self-medication. In every study that discussed self-medication, participants reported using substances to feel calm and relaxed; substances included nicotine/tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and methamphetamine ( 20 , 24 , 32 , 46 , 50 – 52 ). Nicotine/tobacco, marijuana, ecstasy (MDMA), and methamphetamine were used to help improve focus, particularly before diagnosis and subsequent to stimulant treatment ( 20 , 24 , 32 , 51 , 52 ). Participants also reported using substances to help feel “normal” as they facilitated social interactions and helped complete activities of daily life ( 20 , 50 , 52 ). One study described college males’ experiences with video game addictions which resulted in neglecting schoolwork ( 32 ).

The tendencies of people with ADHD to make impulsive decisions were suggested as linking ADHD and substance use ( 20 , 52 ). Substance use worsened ADHD symptoms, most notably impulsivity ( 44 , 52 ). One study attributed high rates of substance use to participants with ADHD being less fearful and more rebellious than individuals without ADHD ( 50 ).

Although discontinuing substance use was regarded as a difficult process with frequent relapses, participants considered their quality of life to improve after quitting ( 30 , 44 , 53 ). Nicotine withdrawal was reported to worsen ADHD symptoms, and participants desired smoking-cessation programs specifically tailored for those with ADHD ( 53 ). Even after discontinuation of substance use, participants reported difficulties accessing stimulant medication due to their substance-use histories ( 52 ).

Stimulants and use of other substances

Findings relating stimulant use and use of other substances were mixed. Prescription stimulant usage was reported as a protective factor against use of other substances. Participants who had previously been self-medicating reported that when they had been on stimulants, they did not need other substances to help them feel calm and focused ( 46 , 47 , 50 , 52 ). Stimulants were reported to decrease cigarette cravings ( 50 ). In one study, a participant commented that her stimulant prescription generated a hatred of taking pills, which she reported subsequently prevented her from using drugs ( 54 ).

Some participants reported stimulant prescriptions as increasing risk of substance use. Some reported that stimulants directly increased nicotine cravings ( 50 ). Indirect connections were reported, such as feelings of social exclusion due to being labeled as medicated or due to participants feeling used to taking drugs since childhood ( 54 ). Other participants reported no connection between stimulant medication and use of other substances ( 50 , 54 ).

Perceptions of self and diagnosis

Self-esteem.

Participants often reported experiencing low self-esteem which they attributed to feeling unable to keep up with work or school, being told they were not good enough by others, and frequently failing at life goals ( 24 , 27 – 29 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 41 , 43 ). Low self-image was typically worse in childhood and improved over time, especially after receiving a diagnosis ( 28 , 36 , 43 ). In one study, some participants did not see themselves as having any flaws despite repeatedly being told otherwise, possibly due to being distracted from the emotional impact of these remarks ( 29 ).

Views of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Some participants viewed ADHD as a personality trait or difference as opposed to a disorder or disability ( 31 , 32 , 39 , 41 , 45 ). Some participants reported finding the ADHD diagnosis limiting and not wanting the disorder to define who they were ( 27 , 28 ). When asked if they would want their ADHD “cured” in one study, participants’ responses ranged from “definitively yes” to “definitely no.” Many reported feeling ambivalent as they described both positive and negative aspects of ADHD ( 20 ).

Interactions with society

Relationships with others.

Difficulties building and maintaining relationships with others were regularly reported. Participants reported that impulsivity hindered their social interactions due to their tendencies to make inappropriate remarks, engage in reckless behaviors, and agree to engagements without thinking through consequences, resulting in being associated with people to whom they did not want to be linked ( 20 , 22 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 43 ). Reported organizational struggles contributed to participants frequently being late and having cluttered living spaces ( 24 , 38 ). Participants reported misunderstanding social norms and hierarchies and being hesitant about starting conversations ( 28 , 30 , 40 , 43 ). They reported feeling overwhelmed by others’ emotions and unsure how to respond to them ( 44 ). Some participants reported choosing to hide their ADHD diagnoses, and the resultant barrier made socializing feel exhausting ( 24 ). Participants reported that these factors made sustaining long-term relationships especially difficult ( 22 , 31 , 38 , 43 ).

Feeling different from others was widely reported, most notably in childhood ( 20 , 24 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 32 ). This experience was described as feeling misunderstood, like a misfit, abnormal, and/or like there was something wrong with them ( 20 , 24 , 27 , 29 , 33 , 43 , 45 , 50 ). Participants reported consciously pretending to be normal as an attempt to fit in ( 28 , 41 ). Some participants reported seeing themselves as more brave or rebellious than their peers, which sometimes resulted in positive self-images ( 24 , 36 , 50 ). A strong desire to advocate for “the underdog” in interpersonal relationships was described by some women ( 31 ). In one study, most participants did not describe feeling different from others, but reported having felt misunderstood as children ( 36 ).

Participants with ADHD who also had children diagnosed with ADHD reported that their approaches to their children’s diagnoses were shaped by their own ADHD experiences. Parents reported uniform support of diagnostic testing, although the best time for testing was not agreed-upon ( 26 , 48 ). Opinions on starting their children on stimulants varied, ranging from enthusiastic support to viewing medication as a last resort, even among participants who had responded positively to stimulants themselves ( 48 ). Most participants reported supporting shared decision-making with the child.

Outside perceptions of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Participants reported their social networks often expressed preconceived notions about the diagnosis, such as ADHD being “fake” or restricted to children ( 27 – 29 , 37 , 41 ). Stigma about ADHD was reported as having prevented many from disclosing their diagnosis both personally and professionally ( 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 32 ). Increased awareness and education about ADHD were desired by participants to help them function better in society ( 28 , 41 ).

Societal expectations

Some studies discussed participants’ difficulties with meeting societal expectations. Participants reported struggling to keep up with daily tasks such as maintaining their living spaces, paying bills and remembering to eat ( 28 , 33 , 35 , 41 ). These difficulties were reported to result in exasperation, low self-esteem, and exhaustion ( 29 , 33 ).

Education and occupation

Academic underachievement was widely reported; most studies focused on postsecondary education. Some participants reported having to try harder than their peers for the same results ( 28 , 35 ), while others reported that they fell behind due to not putting in much effort ( 24 , 27 ). Reports of low motivation to complete assignments until the last minute, as it then became easier to focus, led to missed deadlines ( 32 , 35 , 38 ). Participants reported difficulties paying attention in class ( 24 , 27 , 32 , 35 ), struggling with reading comprehension ( 27 , 32 ), and needing extra tutoring ( 24 , 28 ). Participants reported these difficulties prevented them from “reaching their potential” as they were unable to complete advanced courses or degrees necessary for their careers of choice ( 20 , 22 , 31 , 37 , 39 ). A third of participants in one study noted that they did not struggle academically ( 31 ). Reported coping mechanisms for mitigating academic impairment included medications ( 35 , 47 ), active engagement with materials facilitated by small class sizes or study groups ( 23 , 35 ), and studying from home with fewer distractions ( 34 ). Formal academic accommodations are discussed under the outside support subheading of adapting to symptoms.

Occupational struggles were commonly reported, with many studies detailing participant underemployment or unemployment and high job-turnover rates ( 22 , 31 , 33 , 37 , 41 , 43 ). Difficulties with punctuality and keeping up with tasks and deadlines were reported to generate tensions in the workplace ( 20 , 22 , 24 , 33 , 35 , 39 ), and participants reported frequently being bored and unable to stay focused on their responsibilities, with noisy workplaces promoting distractibility ( 20 , 24 , 33 , 35 , 39 , 40 ). Some studies noted difficulties understanding and navigating social hierarchies in the workplace ( 20 , 40 ). In one study, participants reported feeling unable to maintain work-life balance, overworking until they felt burnt out ( 36 ). Working in fields of intrinsic interest, multitasking, and self-employment were reported strategies used to achieve occupational success ( 24 , 31 , 40 ). Having an understanding employer who could assist with task delegation and understand their needs was described as promoting positive workplace dynamics ( 25 , 33 , 40 ). Clearly defied roles and working with others helped some participants remain engaged in work ( 42 ). College students often reported part-time jobs as rewarding, with responsibilities helping them manage their academic pursuits ( 35 ).

Accessing services

Adults described difficulties accessing healthcare for ADHD. Most reported having to fight to receive a diagnosis and medication due to perceptions of stigma from physicians about adult ADHD ( 22 ). After diagnosis, participants often felt they did not receive adequate counseling or follow-up, especially when seeing general practitioners ( 22 , 26 ). Many participants reported not seeing physicians regularly for medication management due to bureaucratic difficulties ( 21 ); college students reported often having their former pediatricians refill prescriptions without regular appointments ( 47 ). Many participants in one study had little knowledge of ADHD services available to them despite regular appointments ( 32 ).

This review characterizes the current literature on the lived experiences of adults with ADHD. This includes experiences of having been diagnosed as an adult, symptomatology of adult ADHD, skills used to adapt to ADHD symptoms, relationships between ADHD and substance use, individual perceptions of self and of having received ADHD diagnoses, and social experiences interacting in society.

Similar themes were noted in a previous review on lived experiences of adults with ADHD consisting of ten studies, three of which were included here ( 17 ). Such themes included participants feeling different from others, perceiving themselves as creative, and implementing coping skills. There were also other similar findings from a review of eleven studies on the experiences of adolescents with ADHD ( 55 ). Overlapping themes included participants feeling that ADHD symptomatology has some benefits, experiencing difficulties with societal expectations, emotions and interpersonal conflicts, struggling with identity and stigma, and having varying experiences with stimulants. The overlaps in findings from these two reviews suggest there are shared experiences between adolescents and adults with ADHD. Unique from previous reviews on lived experiences of people with ADHD are the present qualitative findings of experiences of having received diagnoses in adulthood, reflections on ADHD and substance use, occupational struggles, attention dysregulation, and emotional symptoms of ADHD.

The relationship between ADHD effects and poor occupational performance has been previously described. People with ADHD often struggle with unemployment and underemployment and functional impairment at work ( 56 – 58 ). The findings of this review suggest that adults with ADHD may benefit from workplace accommodations and from decreased stigma around adult ADHD.

Findings suggest that people with ADHD often experience attention dysregulation as opposed to attention deficits, per se . This notion builds on previous clinical observations ( 59 ) and quantitative literature ( 60 , 61 ) documenting that adults with ADHD may hyperfocus on tasks of interest. These findings suggest that inattention does not fully capture the attentional symptoms of the condition and suggest a possible need for updated diagnostic criteria.

Emotional dysregulation was described by many studies in this review, and there were no studies in which participants denied struggling with emotions. These findings provide support for a conceptual model of ADHD that presents emotional dysregulation as a core feature of ADHD, as opposed to models stating that emotional dysregulation is a subtype of ADHD or simply that the domains are correlated ( 62 ). Debates exist regarding whether or not specific clinical aspects of disorders constitute core or diagnostic features ( 63 ). The DSM-5 and ICD-11 have viewed differently the criteria for specific disorders, including with respect to engagement for emotional regulation or stress-reduction purposes [e.g., behavioral addictions like gambling and gaming disorders, and other behaviors relating to compulsive sexual engagement ( 3 , 64 , 65 )]. Because emotional dysregulation is often overlooked as being associated with ADHD, patients experiencing such symptoms may be mistaken for having other conditions such as mood or personality disorders. Appreciating the emotional symptoms of ADHD may help psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers more accurately diagnose ADHD in adults and decrease misdiagnosis.

The recurrent themes of difficulty naming and recognizing emotions found here suggest that ADHD may be associated with alexithymia. One study found that 22% of adults with ADHD were highly alexithymic but their mean scores on the rating scale for alexithymia were not significantly different from controls ( 66 ). Parenting style, attachment features, and ADHD symptoms have been found to predict emotional processing and alexithymia measures among adults with ADHD ( 67 ). More research is needed into the relationship between ADHD symptoms and alexithymia.

There was considerable heterogeneity in wishes regarding cures for ADHD (suggesting both perceived benefits and detriments) and stimulant use being association with SUDs. From a clinical perspective, both points will be important to understand better. With regard to the latter, ADHD and SUDs frequently co-occur; one meta-analysis found that 23% of people with SUDs met criteria for ADHD ( 68 ). Furthermore, youth with ADHD are seven-fold more likely than those without to experience/develop SUDs; however, early treatment with stimulants appeared to decrease this risk ( 69 ). Understanding better motivations for substance use in adults with ADHD as may be gleaned through considering lived experiences may help decrease ADHD/SUD co-occurrence and improve quality of life.

This review highlights gaps in the qualitative literature on adult ADHD. Nearly all included studies took place in Europe, North America or Asia; there is a dearth of qualitative research on ADHD in the Global South. Although most studies did not report race, those that did often had a majority of White participants. Racial/ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis may contribute to the relatively low diversity of study participants ( 9 ), and such disparities are further reason to expand research focused on non-White individuals with ADHD. Most studies focused on young or middle-aged adults and most participants were male; more research is needed on how ADHD may impact older adults and other gender identities. Although long considered to disproportionately affect male children at approximately 3:1 ( 70 ), ADHD in adults has been reported to have gender ratios of 1.5:1 ( 71 ). Among the adult psychiatric population, some studies have found no gender difference in prevalence or up to a 2.5:1 female predominance ( 72 ). This finding suggests that women often may not receive diagnoses until adulthood and there may be strong links with other psychopathologies in women. The lived experience of women with ADHD should be further examined; this insight may help to understand why women often go undiagnosed and experience other psychiatric concerns.

Future qualitative studies should explore how ADHD symptoms change over the lifespan as this was not addressed in any of the included studies. There were very few findings relating to how adults with ADHD conceptualize the condition and how their diagnosis interacts with their identities. Some studies reported on difficulties adults with ADHD have with accessing services; further exploration is needed into how the medical community can better meet the needs of this population. Findings from this review may be used to inform future ADHD screening tools. The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) is a widely used screening tool that covers symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity ( 73 ). This review suggests that symptoms may be more expansive than what is included in the ASRS and that questions on attentional dysregulation and hyperfocusing, emotional dysregulation, internal chaos, low self-esteem, and strained interpersonal relationships could be tested for validity for inclusion. The Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS) includes questions on emotional lability and low self-esteem in addition to symptoms covered by the ASRS ( 74 ), although the scale has been found to have high false-positive and false-negative rates ( 75 ). Further studies are needed to develop screening tools that capture the lived experience of adults with ADHD while maintaining appropriate sensitivity and specificity. This review may also inform tailoring CBT and other therapeutic interventions for ADHD. For example, CBT may help develop skills for volitional hyperfocusing on productive tasks instead of feeling pulled away from daily activities.

This study has limitations. Being a rapid review, it was not an exhaustive search of the available literature and may have missed some relevant studies that would have been identified by a systematic search. The search strategy consisted of ADHD and qualitative research methods; studies that did not include “qualitative” in their titles or abstracts may not have been identified. This may explain why the previous review on the lived experiences of adults with ADHD ( 17 ) included studies not identified by this search. Although a formal quality appraisal was completed, all studies were included regardless of the quality assessment as to not further narrow the review. For example, studies were not excluded based on how they verified ADHD diagnosis as many studies did not specify if or how this was completed. Although restricting studies based on quality metrics may have made the present findings more robust, the amount of data that would have been excluded would have been considerable and may have resulted in omitting important findings. These variable quality metrics not only limit the findings of the present review, but also speak to limitations in the methodological rigor of qualitative research on adult ADHD.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is a relatively common diagnosis among adults. Exploration of the lived experiences of adults with ADHD may illuminate the breadth of symptomatology of the condition and should be considered in the diagnostic criteria for adults. Understanding symptomatology of adults with ADHD and identifying areas of unmet need may help guide intervention development to improve the quality of life of adults with ADHD.

Author contributions

CG and MP contributed to the conception of the review. CG and GM-G performed the abstract and full text screening. CG performed the data synthesis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GM-G, GA, KB, and MP contributed to the revising and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express gratitude to clinical librarian Courtney Brombosz for her assistance in developing the search strategy.

This work was supported by the Yale School of Medicine Office of Student Research One-Year Fellowship and the K12 DA000167 grant.

Conflict of interest

MP has consulted for and advised Opiant Pharmaceuticals, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, BariaTek, AXA, Game Day Data, and the Addiction Policy Forum; has been involved in a patent application with Yale University and Novartis; has received research support from the Mohegan Sun Casino and Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling; has participated in surveys, mailings or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse control disorders or other health topics; and has consulted for law offices and gambling entities on issues related to impulse control or addictive disorders. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.949321/full#supplementary-material

- Brain Fitness With Memorie

- Attention Training With Cogo

- Manage Stress With Galini

- Know Your Mind With MindViewer

- NeeuroOS for Developers

- QuickScreen

- Documentation

- Warranty Registration

- Device Compatibility

Millions of Indian Children (and Parents) Struggle with ADHD

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or ADHD is a cognitive disorder that afflicts approximately 2-7% of children globally. ADHD prevalence in India, however, is much higher than the global average. As the disorder can affect a person’s everyday functioning even until adulthood, children suffering from ADHD in India stand the risk of long-term negative outcomes such as lower educational and employment attainment. In terms of social impact, a child with ADHD can cause a lot of anxiety to the people around him, putting strains on parent/sibling-child relationships. As children with ADHD become adults, they could manifest imbalances in emotion (trouble controlling anger, depression and mood swings, relationships and problems at work) and behavior (getting into addictions and substance abuse, experiencing chronic boredom).

ADHD in India

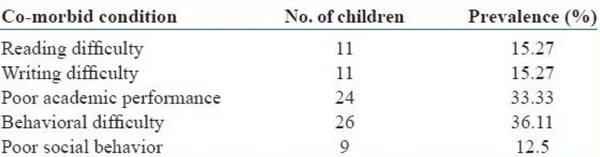

In India, a study entitled Prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Primary School Children that was conducted in Coimbatore found ADHD prevalence in children to be higher than the global estimate, at 11.32% . The highest prevalence is found in ages 9 (at 26.4%) and 10 (at 25%). Further, the study showed that more males (66.7%) were found to have ADHD. Children who have ADHD were also observed to not only have poor academic performance and behavioural difficulty but also had problems with reading and writing.

Another ADHD study conducted in different parts of India also suggested a prevalence between 2% to as high as 17%. In numbers, an article published in India Today mentioned that it is estimated that 10 million Indian children are diagnosed with ADHD annually.

What is ADHD?

In the early days, ADHD was also referred to as ‘Attention Deficit Disorder’(ADD). ADD is a milder representation of the symptoms of ADHD - that is without hyperactivity - and is more often seen in girls. Currently, ADD is no longer considered a medical diagnosis and doctors have been using the term ADHD to describe both the hyperactive and inattentive types.

There are 3 types of ADHD.

- Primarily Inattentive

- Primarily hyperactive-impulsive

Coping with ADHD

Medications.

Medicines used to manage ADHD symptoms help to balance and enhance neurotransmitters thereby improving symptoms. Stimulant medicines work for about 70-80% of people. They can be used to treat both moderate and severe symptoms of ADHD. Some stimulants are approved for children over the age of 3 and children over the age of 6, respectively. These medicines help children, teens, and adults who have a hard time at work, home or school.

Types of medications available for ADHD are:

- If stimulants and non-stimulants don’t work

- If they cause side effects that you can’t live without

- If you have other medical conditions

ADHD Pharmacophobia in Some Indian Communities

Non-pharmacological solutions | adhd india.

In India, there are alternative solutions being advocated:

- Psychosocial interventions – involve behavioral intervention, parent training, peer and social skills training, and school/classroom‑based intervention/training.

- Body focused - body‑oriented activities such as yoga‑based, physical exercises, sleep and mindfulness‑based interventions such as using breathing exercises with music therapy or attention training.

- Cognitive-behavioral training (such as play therapy).

- Neuro cognitive training - computer-based attention and EEG biofeedback training like the Cogo game launched by Singapore-based Neeuro Pte. Ltd. alongside researchers from the Institute of Mental Health (IMH), the medical school Duke-NUS, and Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR).

A decade’s worth of work by the researchers suggested that EEG-based attention training is a promising solution. In fact, brain scans done on the children with ADHD in their latest clinical trial, exhibited reorganized brain network activity, meaning having less inattentive symptoms.

Click the banner below to learn more about Neeuro's Cogo solution!

Topics: CogoLand , ADHD , Digital Therapeutics

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Leave a comment, newsletter sign up.

Disclaimer: Neeuro products are not medical solutions and should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition.

Celebrating 25 Years

- Join ADDitude

- |

- What Is ADHD?

- The ADHD Brain

- ADHD Symptoms

- ADHD in Children

- ADHD in Adults

- ADHD in Women

- Find ADHD Specialists

- New! Symptom Checker

- ADHD Symptom Tests

- All Symptom Tests

- More in Mental Health

- Medication Reviews

- ADHD Medications

- Natural Remedies

- ADHD Therapies

- Managing Treatment

- Treating Your Child

- Behavior & Discipline

- School & Learning

- Teens with ADHD

- Positive Parenting

- Schedules & Routines

- Organizing Your Child

- Health & Nutrition

- More on ADHD Parenting

- Do I Have ADD?

- Getting Things Done

- Relationships

- Time & Productivity

- Organization

- Health & Nutrition

- More for ADHD Adults

- Free Webinars

- Free Downloads

- ADHD Videos

- ADHD Directory

- eBooks + More

- Newsletters

- Guest Blogs

- News & Research

- For Clinicians

- For Educators

- Manage My Subscription

- Get Back Issues

- Digital Magazine

- Gift Subscription

- Renew My Subscription

- ADHD Adults

- Do I Have ADD? Diagnosis & Next Steps

They Denied Her ADHD Because She Was Disciplined, Studious… and Indian

“the accommodations coordinator was basically assuming my parents forced me to take advanced courses. he was valuing my teacher’s observations more than my doctor’s opinion and my personal struggles. i knew if i was a white kid, he would not have made those comments to me.”.

During lessons, Eeshani doodled rainbows and flowers on her notebook, using funky-colored gel pens to take the dryness out of note-taking. Her brain wandered during lectures even though she looked at the board; no hint of her inner struggle for the outside world to see.

At night, she had to study the material taught in class for hours. During a home study session, she could focus… but on the wrong tasks. If she had assignments due on Wednesday and Friday, she’d start Friday’s first. She observed that her peers spent less time studying than she did and earned higher marks. This hurt her self-esteem . Her inner critic told her that she was stupid.

“I would have felt fine getting average grades if I knew I did not put in effort, but I was doing just that,” she said. “When my friends studied for an hour or so, they would get a high A-grade; I would study for four or five hours and receive a low B. It didn’t make sense to me why these things seemed easier for others.”

This Is What ADHD Looks Like?

To many people, a “struggling” student is the class clown or an emotionally unstable child, usually a male — and typically not of Asian descent . A loud, boisterous student who has side conversations during lectures, blurts out answers, doesn’t raise their hand, cannot sit still, talks back to teachers, gets into fights, and has an extensive incident file — this is the stereotypical ADHD poster child .

Eeshani doesn’t fit that profile at all. Those who best know her say she’s reserved and quiet around people she doesn’t know well but becomes a chatterbox once comfortable. When communicating, she does “zone out fast” and miss what people say to her. She prefers not to work in groups for class projects because she doesn’t like to speak up when other students don’t pitch in.

[ Read: “I’m Not Supposed to Have ADHD” ]

Eeshani often skipped exams and napped at home, but she wasn’t playing hooky. She experienced anxiety when taking in-person tests with other students.

“I hated taking tests with students around me in complete silence,” she said. “I’d be so distracted by the noises of pencil taps or feet tapping, so I’d stay home on test days so I could be alone in a room to make up the test.”

Teachers didn’t mind her making up tests at first, but later observed that it was a pattern for her, which raised some suspicion. It’s not that Eeshani neglected to study, either.

“I’d be up until about 4 or 5 a.m., studying,” she said. “I would wake up so tired, but not feel ready for the test, so I’d ask my parents if I could skip that day. Friends would text me asking where I was, and I would say, ‘I can’t take the test.’ I didn’t care if they talked about me, because I did this for me.”

[ Read: “What It Feels Like Living with Undiagnosed ADHD” ]

To her family, Eeshani was independent and mature. While she may have appeared to be just another studious Indian child on the surface, she struggled hard.

“When I would read, I’d read all the words on the page but have truly no idea what I just read, and I’d have to keep re-reading until I could pay proper attention,” she said.

The Moment Her Struggles Became Undeniable

One night, Eeshani burst into her parent’s room crying at 3 a.m. because she couldn’t focus on her study material. Shortly thereafter, her mother called the pediatrician as she requested. The doctor instructed her parents to fill out a form with a checklist, and have Eeshani’s teachers each do so, too.

When she visited her doctor, Eeshani did not imagine that she’d be diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactive disorder ( ADHD ) or obsessive compulsive personality disorder (OCPD). She simply thought she would receive more “studying tips.”

During the appointment, the doctor asked Eeshani about her family health history. When she mentioned that she had an aunt who dealt with anxiety, the doctor suggested that Eeshani may have anxiety as well.

The usually-reserved Eeshani was not afraid to speak up. She told the doctor that she did not think she had an anxiety disorder, but rather extreme focusing difficulties, particularly with tasks that she felt others her age could complete more easily. After reading the teachers’ completed forms, the doctor felt that their observations of Eeshani were “normal.”

“The pediatrician gave me a differential diagnosis of anxiety and instructed me to visit a neurologist to rule out the possibility of ADHD,” Eeshani said.

She Spoke a Truth Everyone Refused to Hear

Eeshani began to advocate for herself at school. She informed a school counselor and accommodation coordinator about the pediatrician’s findings, which led to a grueling ordeal which included a counselor, coordinator, her parents, and all her teachers.

Eeshani’s parents explained her struggles as well the neurologist’s and doctor’s opinions. The teachers shared their opinions about her work ethic and academic performance. One teacher concluded that calculus is a difficult subject, so it’s natural that a student would struggle a bit. Another suggested that she attend early morning help sessions.

“What teachers did not understand was that it wouldn’t matter if I attended the help sessions,” she said. “I knew the course content; I just couldn’t focus, and that was something they could not change unless they understood.”

Eeshani’s accommodations coordinator said that she needed to attend the help sessions. He stated that everyone has anxiety, and he agreed with the teacher that calculus is a tough subject. Eeshani was disappointed to leave the meeting without an Individualized Educational Plan ( IEP ), which gives specialized instruction to students with disabilities, or a 504 Plan that helps provide accommodations to students with disabilities.

“The accommodations coordinator told me that my poor academic performance is nothing out of the ordinary and could result from my choice of taking higher-level courses due to academic pressure,” she said. “I knew right away what he meant. He was basically assuming my parents forced me to take advanced courses. He was valuing my teacher’s observations more than my doctor’s opinion and my personal struggles. I knew if I was a white kid, he would not have made those comments to me.”

What’s more, Eeshani struggled in both AP and regular classes.

“The regular classes were easier, but my grades remained the same as in the AP, and I was expecting them to go up,” she said.

The ADHD Validation She Was Nearly Denied Due to Stereotypes

At a neurologist’s office, Eeshani took a computer simulation test. Her results showed “clear signs of inattentiveness ” compared to a control group that also took that test. She performed well at the start of the test, but her focus level started dropping off later. This was the validation she so badly needed, and then she was sent to a psychiatrist.

“I used to think that I just was not smart, but I noticed that I knew so much course content, but when assessed with simple multiple-choice questions, I couldn’t convey that,” she said.

Eeshani visited a psychiatrist as the neurologist recommended. The psychiatrist diagnosed her with ADHD and OCPD, which is marked by preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and mental and interpersonal control, at the expense of flexibility, openness, and efficiency.

“He told me that OCPD includes behaviors such as wanting to be in a certain environment or wanting to be ambitious and high-achieving to set goals made for myself, but while remaining independent,” she said.

She began taking stimulant medications — first Vyvanse , and then switched to Adderall XR for insurance reasons. Her psychiatrist, who is also Indian American, applauded her parents for bringing her in. He said many South Asian families don’t take their kids to psychiatrists, which inhibits proper diagnosis.