- Open access

- Published: 28 June 2021

Impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes: a systematic review protocol

- Foluso Ishola ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8644-0570 1 ,

- U. Vivian Ukah 1 &

- Arijit Nandi 1

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 192 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

2 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

A country’s abortion law is a key component in determining the enabling environment for safe abortion. While restrictive abortion laws still prevail in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), many countries have reformed their abortion laws, with the majority of them moving away from an absolute ban. However, the implications of these reforms on women’s access to and use of health services, as well as their health outcomes, is uncertain. First, there are methodological challenges to the evaluation of abortion laws, since these changes are not exogenous. Second, extant evaluations may be limited in terms of their generalizability, given variation in reforms across the abortion legality spectrum and differences in levels of implementation and enforcement cross-nationally. This systematic review aims to address this gap. Our aim is to systematically collect, evaluate, and synthesize empirical research evidence concerning the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs.

We will conduct a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature on changes in abortion laws and women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will search Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases, as well as grey literature and reference lists of included studies for further relevant literature. As our goal is to draw inference on the impact of abortion law reforms, we will include quasi-experimental studies examining the impact of change in abortion laws on at least one of our outcomes of interest. We will assess the methodological quality of studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series checklist. Due to anticipated heterogeneity in policy changes, outcomes, and study designs, we will synthesize results through a narrative description.

This review will systematically appraise and synthesize the research evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will examine the effect of legislative reforms and investigate the conditions that might contribute to heterogeneous effects, including whether specific groups of women are differentially affected by abortion law reforms. We will discuss gaps and future directions for research. Findings from this review could provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services and scale up accessibility.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019126927

Peer Review reports

An estimated 25·1 million unsafe abortions occur each year, with 97% of these in developing countries [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Despite its frequency, unsafe abortion remains a major global public health challenge [ 4 , 5 ]. According to the World health Organization (WHO), nearly 8% of maternal deaths were attributed to unsafe abortion, with the majority of these occurring in developing countries [ 5 , 6 ]. Approximately 7 million women are admitted to hospitals every year due to complications from unsafe abortion such as hemorrhage, infections, septic shock, uterine and intestinal perforation, and peritonitis [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. These often result in long-term effects such as infertility and chronic reproductive tract infections. The annual cost of treating major complications from unsafe abortion is estimated at US$ 232 million each year in developing countries [ 10 , 11 ]. The negative consequences on children’s health, well-being, and development have also been documented. Unsafe abortion increases risk of poor birth outcomes, neonatal and infant mortality [ 12 , 13 ]. Additionally, women who lack access to safe and legal abortion are often forced to continue with unwanted pregnancies, and may not seek prenatal care [ 14 ], which might increase risks of child morbidity and mortality.

Access to safe abortion services is often limited due to a wide range of barriers. Collectively, these barriers contribute to the staggering number of deaths and disabilities seen annually as a result of unsafe abortion, which are disproportionately felt in developing countries [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. A recent systematic review on the barriers to abortion access in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) implicated the following factors: restrictive abortion laws, lack of knowledge about abortion law or locations that provide abortion, high cost of services, judgmental provider attitudes, scarcity of facilities and medical equipment, poor training and shortage of staff, stigma on social and religious grounds, and lack of decision making power [ 17 ].

An important factor regulating access to abortion is abortion law [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Although abortion is a medical procedure, its legal status in many countries has been incorporated in penal codes which specify grounds in which abortion is permitted. These include prohibition in all circumstances, to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, and on request with no requirement for justification [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

Although abortion laws in different countries are usually compared based on the grounds under which legal abortions are allowed, these comparisons rarely take into account components of the legal framework that may have strongly restrictive implications, such as regulation of facilities that are authorized to provide abortions, mandatory waiting periods, reporting requirements in cases of rape, limited choice in terms of the method of abortion, and requirements for third-party authorizations [ 19 , 21 , 22 ]. For example, the Zambian Termination of Pregnancy Act permits abortion on socio-economic grounds. It is considered liberal, as it permits legal abortions for more indications than most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa; however, abortions must only be provided in registered hospitals, and three medical doctors—one of whom must be a specialist—must provide signatures to allow the procedure to take place [ 22 ]. Given the critical shortage of doctors in Zambia [ 23 ], this is in fact a major restriction that is only captured by a thorough analysis of the conditions under which abortion services are provided.

Additionally, abortion laws may exist outside the penal codes in some countries, where they are supplemented by health legislation and regulations such as public health statutes, reproductive health acts, court decisions, medical ethic codes, practice guidelines, and general health acts [ 18 , 19 , 24 ]. The diversity of regulatory documents may lead to conflicting directives about the grounds under which abortion is lawful [ 19 ]. For example, in Kenya and Uganda, standards and guidelines on the reduction of morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion supported by the constitution was contradictory to the penal code, leaving room for an ambiguous interpretation of the legal environment [ 25 ].

Regulations restricting the range of abortion methods from which women can choose, including medication abortion in particular, may also affect abortion access [ 26 , 27 ]. A literature review contextualizing medication abortion in seven African countries reported that incidence of medication abortion is low despite being a safe, effective, and low-cost abortion method, likely due to legal restrictions on access to the medications [ 27 ].

Over the past two decades, many LMICs have reformed their abortion laws [ 3 , 28 ]. Most have expanded the grounds on which abortion may be performed legally, while very few have restricted access. Countries like Uruguay, South Africa, and Portugal have amended their laws to allow abortion on request in the first trimester of pregnancy [ 29 , 30 ]. Conversely, in Nicaragua, a law to ban all abortion without any exception was introduced in 2006 [ 31 ].

Progressive reforms are expected to lead to improvements in women’s access to safe abortion and health outcomes, including reductions in the death and disabilities that accompany unsafe abortion, and reductions in stigma over the longer term [ 17 , 29 , 32 ]. However, abortion law reforms may yield different outcomes even in countries that experience similar reforms, as the legislative processes that are associated with changing abortion laws take place in highly distinct political, economic, religious, and social contexts [ 28 , 33 ]. This variation may contribute to abortion law reforms having different effects with respect to the health services and outcomes that they are hypothesized to influence [ 17 , 29 ].

Extant empirical literature has examined changes in abortion-related morbidity and mortality, contraceptive usage, fertility, and other health-related outcomes following reforms to abortion laws [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. For example, a study in Mexico reported that a policy that decriminalized and subsidized early-term elective abortion led to substantial reductions in maternal morbidity and that this was particularly strong among vulnerable populations such as young and socioeconomically disadvantaged women [ 38 ].

To the best of our knowledge, however, the growing literature on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes has not been systematically reviewed. A study by Benson et al. evaluated evidence on the impact of abortion policy reforms on maternal death in three countries, Romania, South Africa, and Bangladesh, where reforms were immediately followed by strategies to implement abortion services, scale up accessibility, and establish complementary reproductive and maternal health services [ 39 ]. The three countries highlighted in this paper provided unique insights into implementation and practical application following law reforms, in spite of limited resources. However, the review focused only on a selection of countries that have enacted similar reforms and it is unclear if its conclusions are more widely generalizable.

Accordingly, the primary objective of this review is to summarize studies that have estimated the causal effect of a change in abortion law on women’s health services and outcomes. Additionally, we aim to examine heterogeneity in the impacts of abortion reforms, including variation across specific population sub-groups and contexts (e.g., due to variations in the intensity of enforcement and service delivery). Through this review, we aim to offer a higher-level view of the impact of abortion law reforms in LMICs, beyond what can be gained from any individual study, and to thereby highlight patterns in the evidence across studies, gaps in current research, and to identify promising programs and strategies that could be adapted and applied more broadly to increase access to safe abortion services.

The review protocol has been reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [ 40 ] (Additional file 1 ). It was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database CRD42019126927.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies.

This review will consider quasi-experimental studies which aim to estimate the causal effect of a change in a specific law or reform and an outcome, but in which participants (in this case jurisdictions, whether countries, states/provinces, or smaller units) are not randomly assigned to treatment conditions [ 41 ]. Eligible designs include the following:

Pretest-posttest designs where the outcome is compared before and after the reform, as well as nonequivalent groups designs, such as pretest-posttest design that includes a comparison group, also known as a controlled before and after (CBA) designs.

Interrupted time series (ITS) designs where the trend of an outcome after an abortion law reform is compared to a counterfactual (i.e., trends in the outcome in the post-intervention period had the jurisdiction not enacted the reform) based on the pre-intervention trends and/or a control group [ 42 , 43 ].

Differences-in-differences (DD) designs, which compare the before vs. after change in an outcome in jurisdictions that experienced an abortion law reform to the corresponding change in the places that did not experience such a change, under the assumption of parallel trends [ 44 , 45 ].

Synthetic controls (SC) approaches, which use a weighted combination of control units that did not experience the intervention, selected to match the treated unit in its pre-intervention outcome trend, to proxy the counterfactual scenario [ 46 , 47 ].

Regression discontinuity (RD) designs, which in the case of eligibility for abortion services being determined by the value of a continuous random variable, such as age or income, would compare the distributions of post-intervention outcomes for those just above and below the threshold [ 48 ].

There is heterogeneity in the terminology and definitions used to describe quasi-experimental designs, but we will do our best to categorize studies into the above groups based on their designs, identification strategies, and assumptions.

Our focus is on quasi-experimental research because we are interested in studies evaluating the effect of population-level interventions (i.e., abortion law reform) with a design that permits inference regarding the causal effect of abortion legislation, which is not possible from other types of observational designs such as cross-sectional studies, cohort studies or case-control studies that lack an identification strategy for addressing sources of unmeasured confounding (e.g., secular trends in outcomes). We are not excluding randomized studies such as randomized controlled trials, cluster randomized trials, or stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trials; however, we do not expect to identify any relevant randomized studies given that abortion policy is unlikely to be randomly assigned. Since our objective is to provide a summary of empirical studies reporting primary research, reviews/meta-analyses, qualitative studies, editorials, letters, book reviews, correspondence, and case reports/studies will also be excluded.

Our population of interest includes women of reproductive age (15–49 years) residing in LMICs, as the policy exposure of interest applies primarily to women who have a demand for sexual and reproductive health services including abortion.

Intervention

The intervention in this study refers to a change in abortion law or policy, either from a restrictive policy to a non-restrictive or less restrictive one, or vice versa. This can, for example, include a change from abortion prohibition in all circumstances to abortion permissible in other circumstances, such as to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, or on request with no requirement for justification. It can also include the abolition of existing abortion policies or the introduction of new policies including those occurring outside the penal code, which also have legal standing, such as:

National constitutions;

Supreme court decisions, as well as higher court decisions;

Customary or religious law, such as interpretations of Muslim law;

Medical ethical codes; and

Regulatory standards and guidelines governing the provision of abortion.

We will also consider national and sub-national reforms, although we anticipate that most reforms will operate at the national level.

The comparison group represents the counterfactual scenario, specifically the level and/or trend of a particular post-intervention outcome in the treated jurisdiction that experienced an abortion law reform had it, counter to the fact, not experienced this specific intervention. Comparison groups will vary depending on the type of quasi-experimental design. These may include outcome trends after abortion reform in the same country, as in the case of an interrupted time series design without a control group, or corresponding trends in countries that did not experience a change in abortion law, as in the case of the difference-in-differences design.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes.

Access to abortion services: There is no consensus on how to measure access but we will use the following indicators, based on the relevant literature [ 49 ]: [ 1 ] the availability of trained staff to provide care, [ 2 ] facilities are geographically accessible such as distance to providers, [ 3 ] essential equipment, supplies and medications, [ 4 ] services provided regardless of woman’s ability to pay, [ 5 ] all aspects of abortion care are explained to women, [ 6 ] whether staff offer respectful care, [ 7 ] if staff work to ensure privacy, [ 8 ] if high-quality, supportive counseling is provided, [ 9 ] if services are offered in a timely manner, and [ 10 ] if women have the opportunity to express concerns, ask questions, and receive answers.

Use of abortion services refers to induced pregnancy termination, including medication abortion and number of women treated for abortion-related complications.

Secondary outcomes

Current use of any method of contraception refers to women of reproductive age currently using any method contraceptive method.

Future use of contraception refers to women of reproductive age who are not currently using contraception but intend to do so in the future.

Demand for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who are currently using, or whose sexual partner is currently using, at least one contraceptive method.

Unmet need for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using any method of contraception.

Fertility rate refers to the average number of children born to women of childbearing age.

Neonatal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death of newborn babies within the first 28 days of life.

Maternal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth.

There will be no language, date, or year restrictions on studies included in this systematic review.

Studies have to be conducted in a low- and middle-income country. We will use the country classification specified in the World Bank Data Catalogue to identify LMICs (Additional file 2 ).

Search methods

We will perform searches for eligible peer-reviewed studies in the following electronic databases.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) (from 1946 to present)

Embase Classic+Embase on OvidSP (from 1947 to present)

CINAHL (1973 to present); and

Web of Science (1900 to present)

The reference list of included studies will be hand searched for additional potentially relevant citations. Additionally, a grey literature search for reports or working papers will be done with the help of Google and Social Science Research Network (SSRN).

Search strategy

A search strategy, based on the eligibility criteria and combining subject indexing terms (i.e., MeSH) and free-text search terms in the title and abstract fields, will be developed for each electronic database. The search strategy will combine terms related to the interventions of interest (i.e., abortion law/policy), etiology (i.e., impact/effect), and context (i.e., LMICs) and will be developed with the help of a subject matter librarian. We opted not to specify outcomes in the search strategy in order to maximize the sensitivity of our search. See Additional file 3 for a draft of our search strategy.

Data collection and analysis

Data management.

Search results from all databases will be imported into Endnote reference manager software (Version X9, Clarivate Analytics) where duplicate records will be identified and excluded using a systematic, rigorous, and reproducible method that utilizes a sequential combination of fields including author, year, title, journal, and pages. Rayyan systematic review software will be used to manage records throughout the review [ 50 ].

Selection process

Two review authors will screen titles and abstracts and apply the eligibility criteria to select studies for full-text review. Reference lists of any relevant articles identified will be screened to ensure no primary research studies are missed. Studies in a language different from English will be translated by collaborators who are fluent in the particular language. If no such expertise is identified, we will use Google Translate [ 51 ]. Full text versions of potentially relevant articles will be retrieved and assessed for inclusion based on study eligibility criteria. Discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or will involve a third reviewer as an arbitrator. The selection of studies, as well as reasons for exclusions of potentially eligible studies, will be described using a PRISMA flow chart.

Data extraction

Data extraction will be independently undertaken by two authors. At the conclusion of data extraction, these two authors will meet with the third author to resolve any discrepancies. A piloted standardized extraction form will be used to extract the following information: authors, date of publication, country of study, aim of study, policy reform year, type of policy reform, data source (surveys, medical records), years compared (before and after the reform), comparators (over time or between groups), participant characteristics (age, socioeconomic status), primary and secondary outcomes, evaluation design, methods used for statistical analysis (regression), estimates reported (means, rates, proportion), information to assess risk of bias (sensitivity analyses), sources of funding, and any potential conflicts of interest.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Two independent reviewers with content and methodological expertise in methods for policy evaluation will assess the methodological quality of included studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series risk of bias checklist [ 52 ]. This checklist provides a list of criteria for grading the quality of quasi-experimental studies that relate directly to the intrinsic strength of the studies in inferring causality. These include [ 1 ] relevant comparison, [ 2 ] number of times outcome assessments were available, [ 3 ] intervention effect estimated by changes over time for the same or different groups, [ 4 ] control of confounding, [ 5 ] how groups of individuals or clusters were formed (time or location differences), and [ 6 ] assessment of outcome variables. Each of the following domains will be assigned a “yes,” “no,” or “possibly” bias classification. Any discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or a third reviewer with expertise in review methodology if required.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The strength of the body of evidence will be assessed using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system [ 53 ].

Data synthesis

We anticipate that risk of bias and heterogeneity in the studies included may preclude the use of meta-analyses to describe pooled effects. This may necessitate the presentation of our main findings through a narrative description. We will synthesize the findings from the included articles according to the following key headings:

Information on the differential aspects of the abortion policy reforms.

Information on the types of study design used to assess the impact of policy reforms.

Information on main effects of abortion law reforms on primary and secondary outcomes of interest.

Information on heterogeneity in the results that might be due to differences in study designs, individual-level characteristics, and contextual factors.

Potential meta-analysis

If outcomes are reported consistently across studies, we will construct forest plots and synthesize effect estimates using meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity will be assessed using the I 2 test where I 2 values over 50% indicate moderate to high heterogeneity [ 54 ]. If studies are sufficiently homogenous, we will use fixed effects. However, if there is evidence of heterogeneity, a random effects model will be adopted. Summary measures, including risk ratios or differences or prevalence ratios or differences will be calculated, along with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Analysis of subgroups

If there are sufficient numbers of included studies, we will perform sub-group analyses according to type of policy reform, geographical location and type of participant characteristics such as age groups, socioeconomic status, urban/rural status, education, or marital status to examine the evidence for heterogeneous effects of abortion laws.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses will be conducted if there are major differences in quality of the included articles to explore the influence of risk of bias on effect estimates.

Meta-biases

If available, studies will be compared to protocols and registers to identify potential reporting bias within studies. If appropriate and there are a sufficient number of studies included, funnel plots will be generated to determine potential publication bias.

This systematic review will synthesize current evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health. It aims to identify which legislative reforms are effective, for which population sub-groups, and under which conditions.

Potential limitations may include the low quality of included studies as a result of suboptimal study design, invalid assumptions, lack of sensitivity analysis, imprecision of estimates, variability in results, missing data, and poor outcome measurements. Our review may also include a limited number of articles because we opted to focus on evidence from quasi-experimental study design due to the causal nature of the research question under review. Nonetheless, we will synthesize the literature, provide a critical evaluation of the quality of the evidence and discuss the potential effects of any limitations to our overall conclusions. Protocol amendments will be recorded and dated using the registration for this review on PROSPERO. We will also describe any amendments in our final manuscript.

Synthesizing available evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms represents an important step towards building our knowledge base regarding how abortion law reforms affect women’s health services and health outcomes; we will provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services, and scale up accessibility. This review will be of interest to service providers, policy makers and researchers seeking to improve women’s access to safe abortion around the world.

Abbreviations

Cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature

Excerpta medica database

Low- and middle-income countries

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols

International prospective register of systematic reviews

Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, Johnson BR, Tuncalp O, Assifi A, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010-14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2372–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Guttmacher Institute. Induced Abortion Worldwide; Global Incidence and Trends 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-worldwide . Accessed 15 Dec 2019.

Singh S, Remez L, Sedgh G, Kwok L, Onda T. Abortion worldwide 2017: uneven progress and unequal access. NewYork: Guttmacher Institute; 2018.

Book Google Scholar

Fusco CLB. Unsafe abortion: a serious public health issue in a poverty stricken population. Reprod Clim. 2013;2(8):2–9.

Google Scholar

Rehnstrom Loi U, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Faxelid E, Klingberg-Allvin M. Health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1502-2 .

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tuncalp O, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):E323–E33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Benson J, Nicholson LA, Gaffikin L, Kinoti SN. Complications of unsafe abortion in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(2):117–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/11.2.117 .

Abiodun OM, Balogun OR, Adeleke NA, Farinloye EO. Complications of unsafe abortion in South West Nigeria: a review of 96 cases. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2013;42(1):111–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I. Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries. BJOG. 2016;123(9):1489–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13552 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vlassoff M, Walker D, Shearer J, Newlands D, Singh S. Estimates of health care system costs of unsafe abortion in Africa and Latin America. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35(3):114–21. https://doi.org/10.1363/3511409 .

Singh S, Darroch JE. Adding it up: costs and benefits of contraceptive services. Estimates for 2012. New York: Guttmacher Institute and United Nations Population Fund; 2012.

Auger N, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Sauve R. Abortion and infant mortality on the first day of life. Neonatology. 2016;109(2):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442279 .

Krieger N, Gruskin S, Singh N, Kiang MV, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Reproductive justice & preventable deaths: state funding, family planning, abortion, and infant mortality, US 1980-2010. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:277–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.03.007 .

Banaem LM, Majlessi F. A comparative study of low 5-minute Apgar scores (< 8) in newborns of wanted versus unwanted pregnancies in southern Tehran, Iran (2006-2007). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(12):898–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050802372390 .

Bhandari A. Barriers in access to safe abortion services: perspectives of potential clients from a hilly district of Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:87.

Seid A, Yeneneh H, Sende B, Belete S, Eshete H, Fantahun M, et al. Barriers to access safe abortion services in East Shoa and Arsi Zones of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. J Health Dev. 2015;29(1):13–21.

Arroyave FAB, Moreno PA. A systematic bibliographical review: barriers and facilitators for access to legal abortion in low and middle income countries. Open J Prev Med. 2018;8(5):147–68. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2018.85015 .

Article Google Scholar

Boland R, Katzive L. Developments in laws on induced abortion: 1998-2007. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2008;34(3):110–20. https://doi.org/10.1363/3411008 .

Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S, Johnson BR Jr, Ganatra B. Global Abortion Policies Database: a descriptive analysis of the legal categories of lawful abortion. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0183-1 .

United Nations Population Division. Abortion policies: A global review. Major dimensions of abortion policies. 2002 [Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/abortion/abortion-policies-2002.asp .

Johnson BR, Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S. Global abortion policies database: a new approach to strengthening knowledge on laws, policies, and human rights standards. Bmc Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0174-2 .

Haaland MES, Haukanes H, Zulu JM, Moland KM, Michelo C, Munakampe MN, et al. Shaping the abortion policy - competing discourses on the Zambian termination of pregnancy act. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0908-8 .

Schatz JJ. Zambia’s health-worker crisis. Lancet. 2008;371(9613):638–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60287-1 .

Erdman JN, Johnson BR. Access to knowledge and the Global Abortion Policies Database. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;142(1):120–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12509 .

Cleeve A, Oguttu M, Ganatra B, Atuhairwe S, Larsson EC, Makenzius M, et al. Time to act-comprehensive abortion care in east Africa. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(9):E601–E2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30136-X .

Berer M, Hoggart L. Medical abortion pills have the potential to change everything about abortion. Contraception. 2018;97(2):79–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.12.006 .

Moseson H, Shaw J, Chandrasekaran S, Kimani E, Maina J, Malisau P, et al. Contextualizing medication abortion in seven African nations: A literature review. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(7-9):950–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2019.1608207 .

Blystad A, Moland KM. Comparative cases of abortion laws and access to safe abortion services in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:351.

Berer M. Abortion law and policy around the world: in search of decriminalization. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19(1):13–27.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Johnson BR, Mishra V, Lavelanet AF, Khosla R, Ganatra B. A global database of abortion laws, policies, health standards and guidelines. B World Health Organ. 2017;95(7):542–4. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.197442 .

Replogle J. Nicaragua tightens up abortion laws. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):15–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60011-7 .

Keogh LA, Newton D, Bayly C, McNamee K, Hardiman A, Webster A, et al. Intended and unintended consequences of abortion law reform: perspectives of abortion experts in Victoria, Australia. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2017;43(1):18–24. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101541 .

Levels M, Sluiter R, Need A. A review of abortion laws in Western-European countries. A cross-national comparison of legal developments between 1960 and 2010. Health Policy. 2014;118(1):95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.06.008 .

Serbanescu F, Morris L, Stupp P, Stanescu A. The impact of recent policy changes on fertility, abortion, and contraceptive use in Romania. Stud Fam Plann. 1995;26(2):76–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137933 .

Henderson JT, Puri M, Blum M, Harper CC, Rana A, Gurung G, et al. Effects of Abortion Legalization in Nepal, 2001-2010. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064775 .

Goncalves-Pinho M, Santos JV, Costa A, Costa-Pereira A, Freitas A. The impact of a liberalisation law on legally induced abortion hospitalisations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;203:142–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.05.037 .

Latt SM, Milner A, Kavanagh A. Abortion laws reform may reduce maternal mortality: an ecological study in 162 countries. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0705-y .

Clarke D, Muhlrad H. Abortion laws and women’s health. IZA discussion papers 11890. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics; 2018.

Benson J, Andersen K, Samandari G. Reductions in abortion-related mortality following policy reform: evidence from Romania, South Africa and Bangladesh. Reprod Health. 2011;8(39). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-8-39 .

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj-Brit Med J. 2015;349.

William R. Shadish, Thomas D. Cook, Donald T. Campbell. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, New York; 2002.

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw098 .

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. The use of controls in interrupted time series studies of public health interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(6):2082–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy135 .

Meyer BD. Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. J Bus Econ Stat. 1995;13(2):151–61.

Strumpf EC, Harper S, Kaufman JS. Fixed effects and difference in differences. In: Methods in Social Epidemiology ed. San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass; 2017.

Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: estimating the effect of California’s Tobacco Control Program. J Am Stat Assoc. 2010;105(490):493–505. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. Am J Polit Sci. 2015;59(2):495–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12116 .

Moscoe E, Bor J, Barnighausen T. Regression discontinuity designs are underutilized in medicine, epidemiology, and public health: a review of current and best practice. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2015;68(2):132–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.021 .

Dennis A, Blanchard K, Bessenaar T. Identifying indicators for quality abortion care: a systematic literature review. J Fam Plan Reprod H. 2017;43(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101427 .

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 .

Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Anton A, Choi A, Fournier JP, Geier AK, et al. The accuracy of Google Translate for abstracting data from non-English-language trials for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2019.

Reeves BC, Wells GA, Waddington H. Quasi-experimental study designs series-paper 5: a checklist for classifying studies evaluating the effects on health interventions-a taxonomy without labels. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.02.016 .

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD .

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Genevieve Gore, Liaison Librarian at McGill University, for her assistance with refining the research question, keywords, and Mesh terms for the preliminary search strategy.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Fonds de recherche du Quebec – Santé (FRQS) PhD doctoral awards and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant, “Examining the impact of social policies on health equity” (ROH-115209).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Purvis Hall 1020 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 1A2, Canada

Foluso Ishola, U. Vivian Ukah & Arijit Nandi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

FI and AN conceived and designed the protocol. FI drafted the manuscript. FI, UVU, and AN revised the manuscript and approved its final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Foluso Ishola .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

PRISMA-P 2015 Checklist. This checklist has been adapted for use with systematic review protocol submissions to BioMed Central journals from Table 3 in Moher D et al: Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews 2015 4:1

Additional File 2:.

LMICs according to World Bank Data Catalogue. Country classification specified in the World Bank Data Catalogue to identify low- and middle-income countries

Additional File 3: Table 1

. Search strategy in Embase. Detailed search terms and filters applied to generate our search in Embase

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ishola, F., Ukah, U.V. & Nandi, A. Impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 10 , 192 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01739-w

Download citation

Received : 02 January 2020

Accepted : 08 June 2021

Published : 28 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01739-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Abortion law/policies; Impact

- Unsafe abortion

- Contraception

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 20 December 2018

Global Abortion Policies Database: a descriptive analysis of the legal categories of lawful abortion

- Antonella F. Lavelanet ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2159-2570 1 ,

- Stephanie Schlitt 2 ,

- Brooke Ronald Johnson Jr 1 &

- Bela Ganatra 1

BMC International Health and Human Rights volume 18 , Article number: 44 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

34 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Texts and interpretations on the lawfulness of abortion and associated administrative requirements can be vague and confusing. It can also be difficult for a woman or provider to know exactly where to look for and how to interpret laws on abortion. To increase transparency, the Global Abortion Policies Database (GAPD), launched in 2017, facilitates the strengthening of knowledge and understanding of the complexities and nuances around lawful abortion as explicitly stated in laws and policies.

We report on data available in the GAPD as of May 2018. We reviewed the content and wording of laws, policies, standards and guidelines, judgments and other official statements for all countries where data is available in the GAPD. We analyzed data for 158 countries, where abortion is lawful on the woman’s request with no requirement for justification and/or for at least one legal ground, including additional indications that are nonequivalent to a single common legal ground. We classified laws on the basis of the explicit wording of the text. The GAPD treats legal categories as the circumstances under which abortion is lawful, that is, allowed or not contrary to law, or explicitly permitted or specified by law.

32% of countries allow or permit abortion at the woman’s request with no requirement for justification. Approximately 82% of countries allow or permit abortion to save the woman’s life. 64% of countries specify health, physical health and/or mental (or psychological) health. 51% allow or permit abortion based on a fetal condition, 46% of countries allow or permit abortion where the pregnancy is the result of rape, and 10% specify an economic or social ground. Laws may also specify several additional indications that are nonequivalent to a single legal ground.

Conclusions

The GAPD reflects details that exist within countries’ laws and highlights the nuance within legal categories of abortion; no assumptions are made as to how laws are interpreted or applied in practice. By examining the text of the law, additional complexities related to the legal categories of abortion become more apparent.

Peer Review reports

Abortion is one of the few health procedures that is legally regulated in most countries, but this was not always the case. There were few restrictions on abortion prior to the nineteenth century; women could access abortion prior to quickening, the time at which a woman can feel fetal movement [ 1 ]. However, with growing concern related to surgical and medical infection risks, abortion came to be seen as a dangerous and life-threatening surgery, prompting greater regulation, including the inclusion of abortion in penal legislation. In addition to health justifications, restrictions were also based on religious ideology, regulating fertility, fetal protection including for eugenic purposes, and in some cases, desires by physicians to limit competitor practice [ 1 , 2 ]. These restrictions were progressively incorporated into countries around the world, threatening the lives and eroding the rights of women around the world [ 3 , 4 ].

In the twentieth century, some countries began to recognize the equal status of women [ 1 ], while other countries began to appreciate the dangers of unsafe abortion [ 3 , 5 ] leading to the liberalization of abortion laws and/or the enactment of new abortion laws [ 6 ]. Where abortion is allowed or permitted, three broad categories exist: 1) abortion on request with no requirement for justification; 2) based on common legal grounds and related indications (hereinafter referred to as legal grounds); or 3) based on additional indications that are nonequivalent to a single legal ground but could be interpreted under multiple grounds. Common legal grounds include abortion to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, and for economic or social reasons [ 7 ]. Abortion regulation may occur in legal texts beyond the penal code, including reproductive health acts, general health acts, and medical ethics codes.

Although expanded categories of lawful abortion potentially yield greater access to abortion, the way in which abortion is expressed in legal texts can be vague and confusing. When looking merely at the legal texts, women and providers may find it difficult to know when abortion is lawful and how to interpret information related to legal requirements to ensure compliance with the law. Additionally, abortion may be regulated as a health procedure; abortion may be criminalized in all cases; there may be uncertain prohibition where laws prohibit unlawful abortion but do not specify what constitutes a lawful abortion; or exceptions for permitted abortion access may be specified in the law. Such regulations may exist in a variety of documents including penal codes, ministerial decrees, abortion-specific acts, and court cases to name a few. The expanding range of regulatory documents can sometimes lead to conflicting directives in various sources or even within the same source [ 7 , 8 ] leading to even greater confusion for women and providers related to the circumstances under which abortion is lawful.

Several databases currently exist which provide information related to country specific abortion laws and may facilitate better understanding of the legal regulation of abortion [ 7 , 9 , 10 ]. These databases often classify countries as falling on a hierarchical spectrum of access to abortion based on the number and type of grounds under which abortion is permitted. To increase transparency, the Global Abortion Policies Database (GAPD) was launched in 2017 [ 11 ] and facilitates the strengthening of knowledge by demonstrating the complexities and nuances of legal texts. The GAPD also contains information related to authorization and service-delivery requirements, conscientious objection, penalties, national SRH indicators, and UN Treaty Monitoring Body concluding observations on abortion. The GAPD does not offer information related to the meaning of legal texts or how legal texts are interpreted or applied in society. The meaning of any legal text is informed by its context: the wider set of laws concerning access requirements and women’s reproductive health more generally, and the culture in which these texts are operationalized. However, the GAPD does provide a starting point from which to understand legal categories, including on request with no requirement for justification, legal grounds, and additional nonequivalent indications as set out in national laws.

In this paper, our main objective is to use data extracted from the GAPD, to report on the number of countries that allow or permit abortion within each legal category and describe the complexities and nuances of these laws, which have not been addressed by other databases or have been obscured by more simplistic classification schemes.

We use data available in the GAPD as of May 2018. Footnote 1 The GAPD contains data that was extracted onto a policy questionnaire, based on closed questions and a finite set of legal grounds. Unique or complex policy nuances that do not exactly match one of the common legal grounds are separately captured in the GAPD as other . Footnote 2 The methodologic details related to the classifying and coding used for the GAPD have been previously described [ 12 ]. In this paper, we diverge from the way in which legal grounds are displayed on the GAPD to better describe the complexities related to legal categories of abortion; we do not present data related to additional access requirements.

The GAPD treats legal categories as the circumstances under which abortion is lawful, that is, allowed or not contrary to law, or explicitly permitted or specified by law (legal grounds). We reviewed the content and wording of laws, policies, standards and guidelines, judgments and other official statements (referred to hereinafter as ‘law’ and ‘laws’) for all countries where abortion is lawful on the woman’s request with no requirement for justification and/or for at least one legal ground, including additional indications that are nonequivalent to a single legal ground. Countries where abortion is prohibited in all circumstances (Andorra, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Holy See, Madagascar, Malta, Nicaragua, Palau, Philippines, Republic of Congo, San Marino, Senegal, and Suriname) and countries where laws prohibit unlawful abortion but do not specify lawful abortion (Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Gambia, Jamaica, Sierra Leone, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Tonga) are also excluded.

We only report on data that is available in the GAPD. Countries which have no data available in GAPD include Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Equatorial Guinea, Honduras, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Niue, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Seven countries (Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canada, China, Mexico, Nigeria, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) that may regulate abortion at the subnational level are not included in the analysis as the GAPD may not have subnational level data or the data may vary significantly across the jurisdictions. Thus, we analyzed data for 158 countries.

The coding and classification of laws is based on the explicit text of the law. We do not make assumptions about the interpretation of laws. Each ground is treated independently; countries where abortion is permitted on request with no requirement for justification are not coded in the database as countries that permit any other legal ground unless those grounds are explicitly stated. The information in the database is limited by accessibility of source documentation and the ability to translate source documents.

On request with no requirement for justification

Abortion at the woman’s request with no requirement for justification is allowed or permitted in 50 countries (32% = 50/158); just over half of these are in Europe (54% = 27/50). In Asia, there are 14 countries where abortion on request is lawful, followed by six in Africa, three in Latin America and the Caribbean, and one in North America; there are no countries in Oceania where abortion is lawful on the woman’s request with no requirement for justification. All but one country (Viet Nam) impose gestational age limits on women accessing abortion on request. Footnote 3 In all other countries, abortion on request is typically available up to 12 weeks of gestation; the range is 8 to 24 weeks.

Legal grounds and related indications

Where abortion is not available on request or once the gestational limit associated with a woman’s request has been reached, abortion may be lawful based on legal grounds or related indications.

Life threat

Approximately 82% (129/158) of countries allow or permit abortion to save the woman’s ‘life’ (See Table 1 ). The threat to life is described in various ways.

Some laws reference the threats/risks the pregnant woman confronts as circumstances in which:

‘continuation of pregnancy endangers the life.’

Others qualify the level of the threat/risk the pregnant woman confronts when:

‘there is a substantial threat to the woman’s life in continuing the pregnancy.’

Yet others compare the risks the woman confronts:

‘if the continuance of the pregnancy would involve a risk to the life of the woman greater than if the pregnancy were terminated” or where “ abortion is the only way to save the woman’s life. ’

Seven of the 129 countries Footnote 4 (5%) utilize a medical or surgical operations clause to permit abortion to save the woman’s life, which exempts from criminal responsibility those who perform ‘in good faith and with reasonable care and skill a surgical operation upon an unborn child for the preservation of the mother’s life, if the performance of the operation is reasonable, having regard to the patient’s state at the time and to all the circumstances of the case.’

In 24 of the 129 countries (19%) where abortion is lawful based on a life threat, Footnote 5 this indication is the only permissible circumstance in which a woman may lawfully obtain an abortion. Most countries do not impose gestational age limits related to the life ground; however, gestational limits are present in 31 countries across the regions (See Table 1 ).

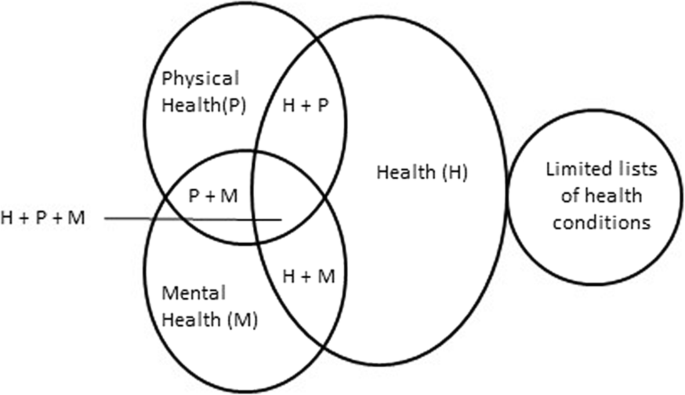

Health threat

The laws of most countries with a health-related ground refer to one or a combination of the following terms: ‘health’, ‘physical health’ and/or ‘mental (or psychological) health.’ Some laws specify limited lists of health conditions (See Fig. 1 ).

Relationship between health, physical health and/or mental health ground and related indications

Of 158 countries analyzed, 101 (64%) specify health in some form. Health alone is specified in 49 (31% = 49/158) countries; 36 (23% = 36/158) additional countries provide greater detail in their laws, specifying the lawfulness of abortion based on both ‘physical health’ and ‘mental health.’ In 10 countries, Footnote 6 laws specify ‘health,’ ‘physical health’ and ‘mental health.’ In Japan and Mongolia, ‘health’ and ‘physical’ health are specified, while in Finland and Iraq, ‘health’ and ‘mental health’ are specified. In Monaco and Zimbabwe, abortion may only be lawful based on a ‘physical health’ ground.

In addition to specifying ‘health’, ‘physical health’ and/or ‘mental (or psychological) health,’ 9 countries Footnote 7 narrow the lawfulness of abortion to certain specified health conditions, including HIV infection, severe depression or where a woman’s psychological equilibrium may be compromised by continuation of the pregnancy.

Most countries do not impose a gestational limit for any health indication, but in the 38 countries (38% = 38/101) where the law specifies an associated gestational limit, most fall between 19 and 24 weeks (See Table 2 ).

Limited lists of health conditions

Six countries (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, and Turkey) have limited lists of specific health conditions; several types of diseases may be included on such lists. In one country, for example, the category “infectious and parasitic diseases” includes all active forms of tuberculosis, severe viral hepatitis, syphilis, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and rubella. The category “mental disorders” includes chronic alcoholism with personality change, transient psychotic conditions resulting from organic diseases, drug addiction and substance abuse, and mental retardation.

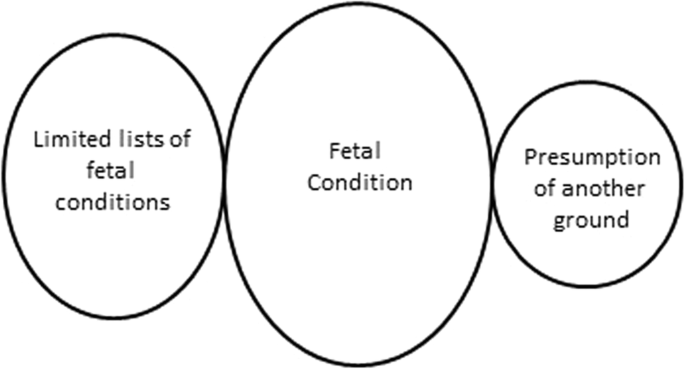

Fetal conditions

Laws allow or permit access to abortion based on fetal conditions; in some cases, countries provide a limited list of conditions or specify a single fetal condition for which abortion is lawful. (See Fig. 2 ).

Relationship between a ground based on fetal condition and related indications

In 80 of the 158 (51%) countries analyzed, abortion is allowed or permitted based on a fetal condition, with no restriction as to the type of fetal condition (See Table 3 ). In 35 of these 80 countries, gestational limits restrict a woman’s access to abortion based on a fetal condition. These gestational ages range from 8 to 35 weeks; the median is 22 weeks.

Limited lists of or single specified fetal condition

In six countries, an abortion is lawful if the fetus has a congenital or hereditary disease (Bulgaria and Lithuania), or where the fetus’s condition is lethal (Bolivia and Colombia) or ‘incompatible with extrauterine life’ (Chile and Uruguay). In Brazil, an anencephalic fetus is the only lawful fetal condition.

Fetal condition - presumption of another ground

In Thailand, if the woman suffers ‘severe stress’ due to the finding that the fetus is afflicted with a ‘severe disability, or has or has a high risk of having severe genetic disease,’ abortion is lawful under the mental health ground. A medical practitioner, other than the one who will perform the termination of pregnancy must authorize the abortion based on this ground in writing.

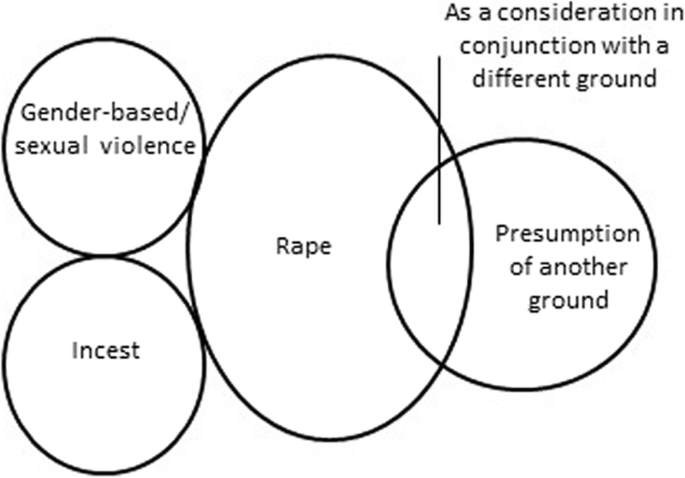

Many countries allow or permit abortion in cases where the pregnancy is the result of rape or gender-based/sexual violence; however, laws vary in how this ground is defined (See Fig. 3 ).

Relationship between rape ground and related indications

Abortion is lawful in 72 of the 158 countries analyzed (46%) if pregnancy is the result of ‘rape.’ In 61% (44/72) of countries where rape is a permitted legal ground, an accompanying gestational limit is imposed. The range between the lowest and highest limits varies across regions (See Table 4 ).

Rape - presumption of another ground

In Barbados and India, abortion is lawful under the mental health ground where pregnancy results from rape. In both countries there is a presumption that pregnancy resulting from rape is or can be injurious to the woman’s mental health, without the need for a health professional’s assessment.

Rape - as a consideration in conjunction with a different ground

One country, New Zealand, specifically states in its law that rape is not in and of itself a legal ground but may be considered if there are reasonable grounds for believing that the pregnancy is the result of sexual violation, where continuation of the pregnancy would result in serious danger to the woman or girl’s life, physical or mental health.

Gender-based/sexual violence

In 14 countries where abortion is permitted on the ground of rape, abortion is also allowed or permitted if the pregnancy is the result of another specific act of sexual violence including human trafficking, forced marriage, sexual assault, or unwanted implantation of a fertilized ovum.

In the laws of six countries, rape is not an explicit indication for abortion, however, similar indications exist. The laws in four countries (Angola, Bulgaria, Italy and Portugal) permit consideration of the circumstances in which the pregnancy occurred, such as if the pregnancy was the “result of a crime against freedom and sexual self-determination” or resulted “from an act of violence.” In Zambia and Bolivia, specific acts of gender-based violence, such as defilement or forced marriage are included in the law.

Of 45/72 (63%) countries that have a rape ground, abortion is also lawful if the pregnancy is the result of ‘incest’. Two countries (Bulgaria and New Zealand) do not explicitly specify a rape ground in their laws but do allow or permit abortion where the pregnancy is the result of incest. Gestational limits restrict a woman’s access to abortion based on incest in 26 of the 45 countries where abortion is lawful. These gestational ages range from 8 to 28 weeks; the median is 20 weeks.

Intellectual or cognitive disability

In 20 of the 158 countries, intellectual or cognitive disability of the woman is specified as a legal ground. In 13 of these 20 countries, gestational limits restrict the application of this indication. The range is between 12 and 28 weeks, the median is 21 weeks.

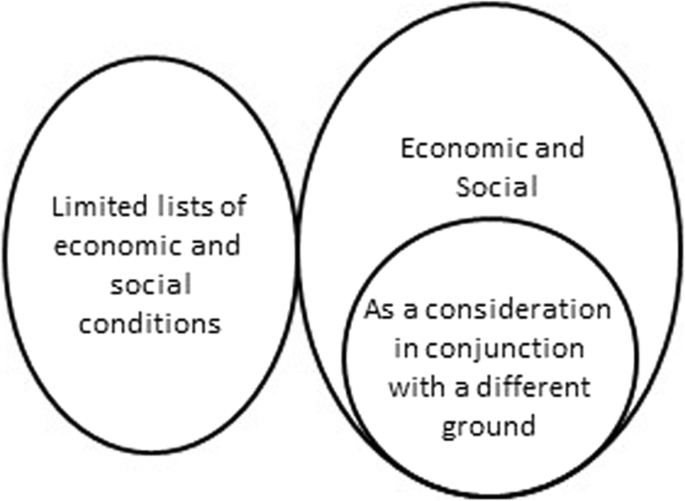

Economic or social ground

Economic and/or social grounds are specified in laws either as an independent ground or as a consideration in conjunction with a different ground. Alternatively, some countries’ laws have limited lists of or a single specific economic or social condition (See Fig. 4 ).

Relationship between economic or social ground and related indications

Of 158 countries analyzed, 16 countries (10%) allow or permit abortion based on an economic or social ground. In 13 of the 16 countries where abortion is permitted on an economic and social ground, gestational limits restrict the application of this indication. The range is between 12 and 22 weeks, the median is 21 weeks.

Economic or social ground -as a consideration in conjunction with a different ground

Six countries permit consideration of economic and social reasons in conjunction with another ground. In Barbados, Belize, and Zambia, a pregnant woman’s actual or foreseeable social environment may be considered in determining whether a risk to her life or health exists. Similarly, a woman’s living conditions or economic circumstances may be taken into account in Germany and Guyana where abortion is considered justified to avert injury to her health. In The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, an abortion is lawful if a woman has seriously deteriorated marital and family relations or a difficult housing condition and these circumstances may be detrimental to her health.

Limited lists of or single specified economic and social conditions

In 16 countries, specific social indications or a limited list of social indications are specified within their laws. For example, in Israel, abortion is lawful where the pregnancy is the result of extramarital relations. In Guyana and Slovakia, abortion is permitted in cases of contraceptive failure. In Kazakhstan, the law includes a list of social circumstances, such as the death of a woman’s husband, the woman and her husband are recognized as officially unemployed, refugee status for the woman, and if the woman has four or more children, to name a few.

Non-equivalent indications

Abortion may also be lawful based on indications that are not equivalent to a single legal ground.

Claim of distress

In four countries, the law allows or permits abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy to women who suffer from distress or similar impact from continuation of the pregnancy. In the Netherlands, a woman’s request for abortion must be based on her opinion that she is in an emergency situation which can only be alleviated by an abortion. In Switzerland, abortion is lawful if a woman provides a written request claiming that she is in distress. In Belgium and Hungary, the woman must be distressed or in a crisis situation, as assessed by her attending doctor.

Age qualification

In 22 countries, abortion is lawful for minors, or those below or above a specified age. In these countries, abortion is typically permitted for girls between 13 and 18 years of age, and women over 40 years. In 14 of the 22 countries, the law allows or permits abortion at one end of this age spectrum, either for those before 18 or after 40 years of age. In 6 countries, minority is accompanied by additional stipulations. For example, in Liberia, a girl under 16 is entitled to an abortion where the pregnancy is the result of illicit intercourse. In Denmark and Ethiopia, a minor whose immaturity renders her unfit to raise a child may have an abortion. In Liechtenstein, a girl under 15 is entitled to an abortion, if she is not married to the person who impregnated her at the time of conception or afterwards. In Benin and Central African Republic, where the pregnancy would constitute a handicap for the minor’s development or lead to a state of grave distress, abortion is lawful.

Various therapeutic indications

In 17 countries, the law allows or permits abortion in circumstances that may be categorized as potentially falling under several common grounds, including life, health, fetal condition, economic and social reasons, and rape. These countries’ laws allow or permit abortion where such procedures are for a “‘therapeutic purpose’ or ‘proven medical necessity,”’ to ‘avert the danger of serious harm to physical integrity’ or to prevent ‘serious and irreversible harm to the body.’ Some of these laws allow or permit abortion where a spouse suffers from a mental disease.

Two additional countries (Bahamas and Grenada) have a surgical operations clause but make no reference to preservation of the ‘mother’s’ life, while one country (Mozambique) permits health committees to examine cases not stipulated in the law on a case-by-case basis to protect pregnant women’s’ sexual and reproductive rights.

Menstrual regulation

In Bangladesh, ‘menstrual regulation’ is medically or surgically available to women as a method of uterine evacuation used to regulate the menstrual cycle when menstruation has been absent for a short duration.

While the GAPD does not provide information on how laws are interpreted or applied in practice, this analysis demonstrates that there are wide variations in how countries specify legal categories, including abortion on a woman’s request with no requirement for justification, legal grounds, and additional, but non-equivalent indications. Unpacking each category and revealing the nuances that exist within legal texts acts a starting point to the discourse around when abortion is allowed or permitted.

Determining what is included within a legal category

The circumstances under which abortion is lawful may be unclear to women and service providers attempting to navigate vague or complex laws . The World Health Organization (WHO) describes health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [ 13 ]. While all WHO Member States accept this definition of health, many countries’ laws do not refer to either the WHO definition or reference explicitly all the component parts of health. The results demonstrate that sometimes health is specified in a variety of ways in legal texts. Where laws contain a specific list of health indications for which an abortion can be performed, questions may arise as to whether service providers will interpret these lists restrictively or whether they will consider them as illustrations, which do not preclude clinical judgment [ 14 ]. Where mental health is not specified, it may not necessarily mean that women with mental health conditions are now lawfully entitled to abortion, given that service providers exercise sole discretion as to whether these conditions will be considered under a more broadly framed ‘health’ indication. Similarly, in cases such as New Zealand, where rape may be considered if the woman is faced with a serious danger in terms of a threat to her life or her physical or mental health, questions arise as to how that effect is assessed.

However, there may be value in the law being vague as it relates to health and other grounds, as access may be available more broadly, in line with the WHO definition. Similarly, countries’ laws that contain vague language, such as ‘therapeutic purposes’, ‘very serious medical reasons’, or ‘necessary treatment to the woman’ may permit health-care providers to apply these indications consistent with their obligation to the health and well-being of their patients. Thus, these indications may apply when there is a threat to the woman’s life or health, in cases where a fetal condition is present, or where a woman faces economic or social circumstances requiring necessary treatment.

Physicians may also apply such grounds against the knowledge that women may seek clandestine abortion, which depending on the context, can pose risks to life and health [ 14 ]. In one country (Bangladesh), despite a restrictive penal code, which offers only a life ground for abortion, menstrual regulation is a lawful way to “to reduce the incidence of unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions” [ 15 ]. Specifically, menstrual regulation is available “as a backup family planning method” to women with a last menstrual period of 10 weeks or less who may be “at risk of pregnancy, whether or not [they are] actually pregnant” [ 15 ]. Providers may also appreciate the risks associated with a continued pregnancy, including the fact that 75% of global maternal deaths are a result of direct obstetric causes [ 16 ], or that mortality associated with childbirth is approximately 14 times higher than that of abortion [ 17 ].

However, without specified legal categories or clear language, and where severe penalties may exist, health-care providers may interpret legal grounds narrowly, restricting access to safe abortion beyond what the law requires. For example, according to a study in Argentina, interpretation related to the scope of the health ground, as well as whether the rape ground applies to all women or only those with mental disabilities, has hindered access to abortion [ 18 ]. Even where a ground is explicitly stated in the law and supported by providers, this same study reveals that only 50% of providers are willing to perform an abortion [ 18 ]. These interpretations may be motivated by culture and gender stereotypes [ 18 ]. While almost all countries allow or permit abortion on the basis of some life-related ground ( N = 133), variations in interpretation or lack of appreciation of the severity of the risk can have devastating consequences [ 19 ].

Additionally, fear of liability may lead health-care providers to limit access well before a gestational limit has been reached for a permitted legal ground [ 20 ]. Interpretation may also impact available methods; for example, service providers may feel they cannot provide medical abortions in countries where the only legal basis for abortion is a medical or surgical operations clause. Thus, greater concerns about abortion access and safety arise when there is lack of clarity related to the law, as providers must balance the risk of potential criminal liability or other self-interests against the needs and desires of the woman.

The legal categories for abortion cannot be neatly packaged into discrete classes based on common legal grounds. It is only by examining the text of the law that nuances are exposed. Subsuming these specific circumstances under common legal grounds provides a false sense of certainty about the legal status and availability of abortion services within a country. For example, in Belgium, Hungary, Netherlands, and Switzerland, countries that have been previously classified as permitting abortion on request, are found on review of the text to permit abortion within the context of a claim of distress where a written or verbal statement is required by the woman describing her situation as one of crisis or emergency or distress.

Legitimizing or delegitimizing women’s claims to abortion

Laws that specify individual legal grounds reflect the perceived legitimacy of some of the reasons women may have for wanting an abortion. Our analysis demonstrates that in most countries’ laws, abortion based on the legal ground of life threat is the most common, followed by health threat, fetal condition and rape, suggesting a hierarchy in the acceptability of women’s reasons. It could be argued that entitlement to abortion is based on a cumulative effect – the more grounds that exist, the greater the likelihood that women in different circumstances may qualify under one of these grounds. However, this raises questions related to fairness and equity regarding why countries single out specific conditions for entitlement to abortion, especially when women more often seek abortion based on socio-economic issues, age, health, family life, and marital status [ 21 ], rather than based on a life threat or rape ground.

This issue is further compounded by associated gestational limits; the wide variation in gestational limits demonstrates that they are not based on evidence. In the case of a fetal impairment indication, for instance, it may be difficult for a woman to comply with a gestational limit of 8 weeks when this time limit is several weeks before usual diagnostic tests are undertaken. Gestational limits narrow a woman’s options as the pregnancy progresses making legal grounds with higher gestational limits appear as more significant than those with lower limits.

Moreover, laws that impose time limits on the length of pregnancy for which abortion can be performed can force some women to seek clandestine abortion or to seek services in other countries, which is costly, delays access (thus increasing health risk) and creates social inequities [ 22 ]. It is for this reason that reducing unsafe abortion and abortion-related morbidity and mortality are less related to the total aggregate of grounds available and more related to access based on broad socioeconomic grounds or at the woman’s request [ 21 ].

This paper focuses on only one aspect of legal abortion; access must be considered within the broader context of sexual and reproductive healthcare. For example, additional barriers may be linked to legal categories and are often inscribed in the law; such barriers include mandatory waiting periods, requirements for third-party authorizations, conscientious objection, and reporting requirements in cases of rape. Laws related to contraception, financing of abortion, and access to medical information also impact how laws and policies are translated into practice. Additionally, national laws exist within a greater international context. The GAPD includes all UN Treaty Monitoring Body concluding observations and Special Procedures reports that have addressed abortion since the year 2000; human rights and UN treaty bodies have reiterated state’s obligations in terms of regulation of abortion and that the “right to sexual and reproductive health is an integral part of the right to health” [ 23 ].

The GAPD aims to increase transparency of information and accountability of countries for the protection of individuals’ health and human rights in the context of abortion. The database expands on existing knowledge related to the legal categories of abortion by capturing unique or complex policy nuances, a starting point by which to better consider legal entitlements to abortion.

This paper highlights the wide variation that exists in legal texts across countries related to the legal categories of abortion demonstrating several indications that have previously been obscured behind more simplistic classification schemes. Illuminating the complexities that exist reveals additional burdens on women and health-care providers to interpret legal categories related to abortion. Moreover, women seek abortion services based on one or more reasons which do not neatly fit into distinct legal classifications, and providers are relied upon to determine a woman’s eligibility based on their interpretation of these laws, creating an illusion of transparency that does not necessarily reflect the actual scope and potential limits of the law. With so much variance in legal texts, questions arise as to how women and healthcare workers appreciate these nuances both within and among different legal categories. Further research is needed to investigate the interpretation and implementation of these laws in practice, including how abortion legal categories co-exist among other laws related to reproductive health and how they are applied across various social, cultural, political, and economic contexts.

Information in the GAPD changes as new sources are received and verified.

‘Other’ includes countries with caveats, stipulations or countries where additional qualifications linked to a woman’s request are required; these countries are not represented as having abortion on request in the GAPD. Results for these countries are presented as an access ground based on a specific legal indication.

In Tajikistan, an order of the Minister of Health containing National Standards for safe abortion and post abortion care exist and may contain information related to gestational limits, but is not reflected here as this source could not be translated.

Africa: Malawi and Uganda; Oceania: Kiribati, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Tuvalu.