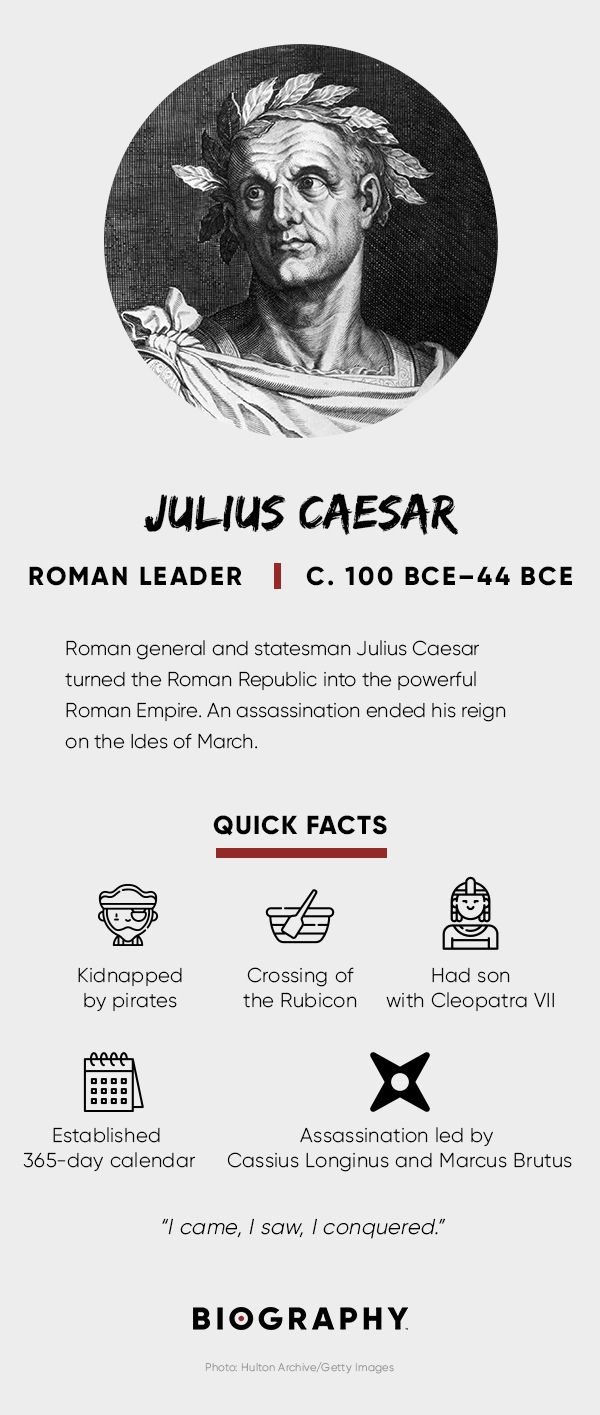

Julius Caesar

Roman general and statesman Julius Caesar turned the Roman Republic into the powerful Roman Empire. An assassination ended his reign on the Ides of March.

Quick Facts

Julius caesar early life, julius caesar's political career, first triumvirate, early rule and gallic wars, civil war against pompey, crossing the rubicon, julius caesar and cleopatra, dictatorship, julius caesar's death, who killed julius caesar, after caesar’s death, archaeological discovery, julius caesar: a play by william shakespeare, who was julius caesar.

Julius Caesar was a leader of ancient Rome who significantly transformed what became known as the Roman Empire by greatly expanding its geographic reach and establishing its imperial system. Allegedly a descendant of Trojan prince Aeneas, Caesar’s birth marked the beginning of a new chapter in Roman history. By age 31, Caesar had fought in several wars and become involved in Roman politics. After several alliances and military victories, he became dictator of the Roman Empire, a rule that lasted for just one year before his death in 44 BCE.

FULL NAME: Gaius Julius Caesar BORN: July 12, 100 BCE DIED: March 15, 44 BCE BIRTHPLACE: Rome, Italy SPOUSE: Cornelia (84–69 BCE), Pompeia (67–62 BCE), Calpurnia (59–44 BCE) CHILDREN: Julia Caesaris, Caesarion ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Cancer

Born Gaius Julius Caesar on July 12, 100 BCE, Caesar hailed from Roman aristocrats, though his family was far from rich. Little is known of Caesar’s early years, but during his youth an element of instability dominated the Roman Republic, which had discredited its nobility and seemed unable to handle its considerable size and influence.

When he was 16, his father, an important regional governor in Asia also named Gaius Julius Caesar, died. He remained close to his mother, Aurelia. Around the time of his father’s death, Caesar made a concerted effort to establish key alliances with the country’s nobility, with whom he was well-connected.

In 84 BCE, Caesar married Cornelia, the daughter of a nobleman. Caesar’s marriage to Cornelia drew the ire of the Roman dictator Sulla, as Cornelia’s father was Sulla’s political rival. Sulla ordered Caesar to divorce his wife or risk losing his property. The young Roman refused and escaped by serving in the military, first in the province of Asia and then in Cilicia. Caesar likely returned to Rome after Sulla’s death circa 79 BCE (another account states Caesar, with the help of his influential friends, eventually convinced Sulla to be allowed to return).

Back in Rome, Caesar and Cornelia had a daughter, Julia Caesaris, in 76 BCE. In 69 BCE, Cornelia passed away.

After Sulla’s death, Caesar began his career in politics as a prosecuting advocate. He relocated temporarily to Rhodes to study philosophy.

During his travels he was kidnapped by pirates. In a daring display of his negotiation skills and counter-insurgency tactics, he convinced his captors to raise his ransom, then organized a naval force to attack them. The pirates were captured and executed.

Caesar further enhanced his stature in 74 BCE when he put together a private army and combated Mithradates VI Eupator, king of Pontus, who had declared war on Rome.

Caesar began an alliance with Gnaeus Pompey Magnus, a powerful military and political leader. Soon after, in 68 or 69 BCE, he was elected quaestor (a minor political office). Caesar went on to serve in several other key government positions.

In 67 BCE, Caesar married Pompeia, the granddaughter of Sulla. Their marriage lasted just a few years, and in 62 BCE, the couple divorced.

In 61 to 60 BCE, Caesar served as governor of the Roman province of Spain. Caesar maintained his alliance with Pompey, which enabled him to get elected as consul, a powerful government position, in 59 BCE.

The same year, Caesar wed Calpurnia, a teenager to whom he remained married for the rest of his life. (He also had several mistresses, including Cleopatra VII , Queen of Egypt, with whom he had a son, Caesarion.)

At the same time Caesar was governing under Pompey, he aligned himself with the wealthy military leader Marcus Licinius Crassus. The strategic political alliance among Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus came to be known as the First Triumvirate.

For Caesar, the First Triumvirate partnership was the perfect springboard to greater domination. Crassus, a leader known as the richest man in Roman history, offered Caesar financial and political support that proved to be instrumental in his rise to power.

Crassus and Pompey, however, were intense rivals. Once again, Caesar displayed his abilities as a negotiator, earning the trust of both Crassus and Pompey and convincing them they’d be better suited as allies than as enemies.

In a controversial move, Caesar tried to pay off Pompey’s soldiers by granting them public lands. Caesar hired some of Pompey’s soldiers to stage a riot. In the midst of all the chaos, he got his way.

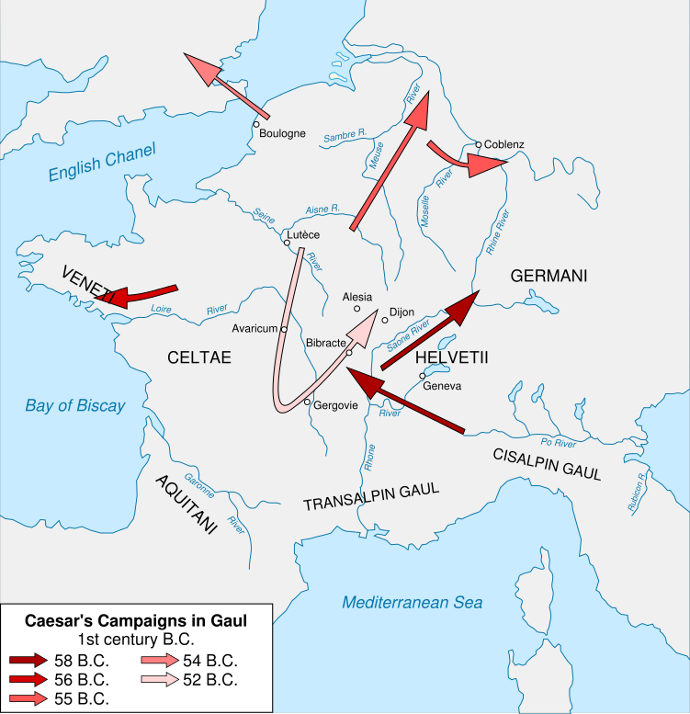

Not long after, Caesar secured the governorship of Gaul (modern-day France and Belgium). This allowed him to build a bigger military and begin the kind of campaigns that would cement his status as one of Rome’s all-time great leaders. Between 58 and 50 BCE, Caesar conquered the rest of Gaul up to the river Rhine.

As he expanded his reach, Caesar was ruthless with his enemies. In one instance he waited until his opponent’s water supply had dried up, then ordered the hands of all the remaining survivors be cut off.

All the while, he was mindful of the political scene back home in Rome, hiring key political agents to act on his behalf.

As Julius Caesar’s power and prestige grew, Pompey grew envious of his political partner. Meanwhile, Crassus still had never completely overcome his disdain for Pompey.

The three leaders patched things up temporarily in 56 BCE at a conference in Luca, which cemented Caesar’s existing territorial rule for another five years, granted Crassus a five-year term in Syria, and accorded Pompey a five-year term in Spain.

Three years later, however, Crassus was killed in a battle in Syria. Around this time, Pompey—his old suspicions about Caesar’s rise reignited—commanded that Caesar disband his army and return to Rome as a private citizen.

Rather than submit to Pompey’s command, on January 10, 49 BCE, Caesar ordered his powerful army to cross the Rubicon River in northern Italy and march toward Rome. As Pompey further aligned himself with nobility, who increasingly saw Caesar as a national threat, civil war between the two leaders proved to be inevitable. Pompey and his troops, however, were no match for Caesar’s military prowess. Pompey fled Rome and eventually landed in Greece, where his troops were defeated by Caesar’s legions.

By late 48 BCE, Caesar had subdued Pompey and his supporters in Italy, Spain, and Greece, finally chasing Pompey into Egypt. The Egyptians, however, knew of Pompey’s defeats and believed the gods favored Caesar: Pompey was assassinated as soon as he stepped ashore in Egypt. Caesar claimed to be outraged over Pompey’s murder. After having Pompey’s assassins put to death, he met with the Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII.

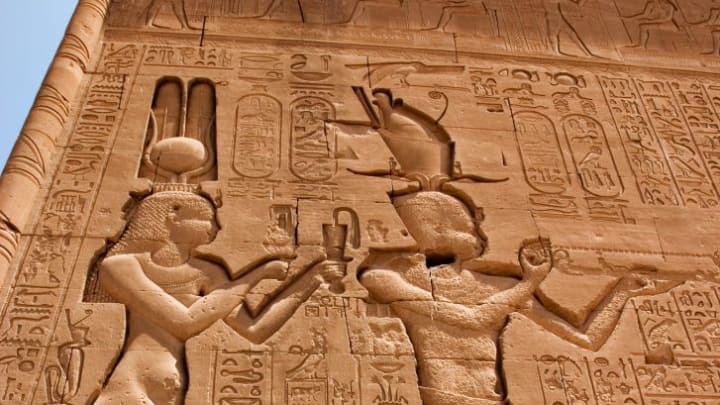

Caesar and Cleopatra forged an alliance (and a sexual relationship) that ousted her brother and co-regent, Ptolemy XIII, and placed Cleopatra on the throne of Egypt. A skilled political tactician, she and her son by Caesar, Caesarion, proved instrumental in international affairs for years, culminating in her liaison with Roman general Mark Antony .

Upon his triumphant return to Rome, Caesar was hailed as the father of his country and made dictator for life. Although he would serve just a year’s term, Caesar’s rule proved instrumental in reforming Rome for his countrymen.

Caesar greatly transformed the empire, relieving debt and reforming the Senate by increasing its size and opening it up so that it better represented all Romans. He altered the Roman calendar and reorganized the construction of local government.

Caesar also resurrected two city-states, Carthage and Corinth, which had been destroyed by his predecessors. And he granted citizenship to a number of foreigners. A benevolent victor, Caesar even invited some of his defeated rivals to join him in the government.

At the same time, Caesar was also careful to solidify his power and rule. He stuffed the Senate with allies and required it to grant him honors and titles. He spoke first at assembly meetings, and Roman coins bore his face.

Although Caesar’s reforms greatly enhanced his standing with Rome’s lower- and middle-class populations, his increasing power was met with envy, concern, and angst in the Roman Senate. A number of politicians saw Caesar as an aspiring king.

And Romans had no desire for monarchical rule: Legend has it that it had been five centuries since they’d last allowed a king to rule them. Caesar’s inclusion of former Roman enemies in the government helped seal his downfall.

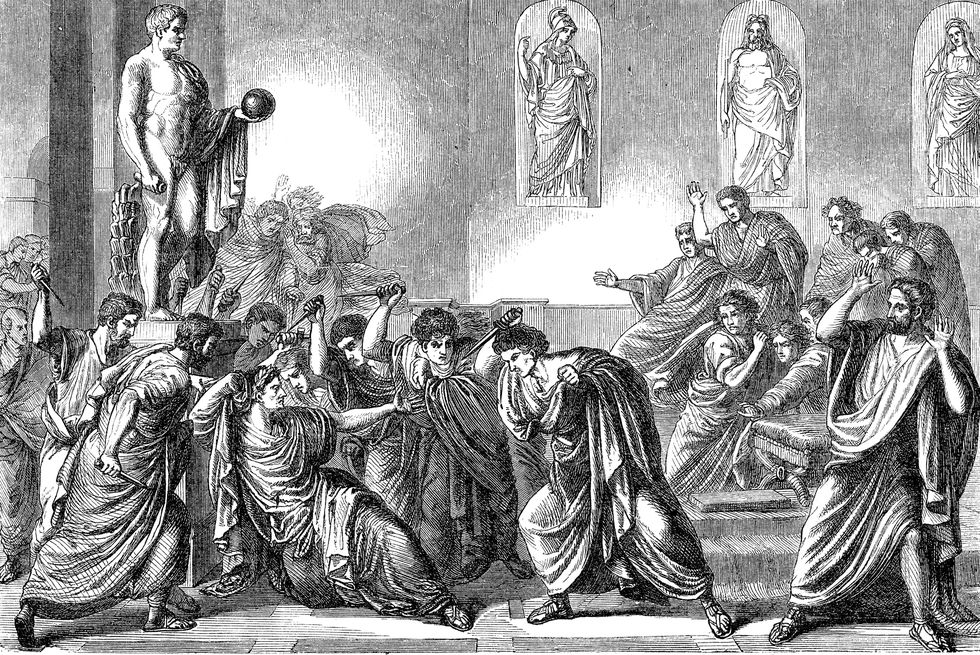

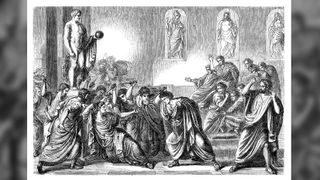

Caesar was assassinated by political rivals in Rome on the Ides of March —March 15—in 44 BCE. It’s not clear whether Caesar knew of the plot to kill him: By all accounts, he planned to leave Rome on March 18 for a military campaign in what is now modern-day Iraq, where he hoped to avenge the losses suffered by his former political ally Crassus.

Gaius Cassius Longinus and Marcus Junius Brutus , former rivals of Caesar who’d joined the Roman Senate, led Caesar’s assassination. Cassius and Brutus dubbed themselves “the liberators.”

Brutus’ involvement in the killing packed the most complicated backstory. During Rome’s earlier civil war, he had originally sided with Caesar’s opponent, Pompey. But after Caesar’s victory over Pompey, Brutus was encouraged to join the government. His mother, Servilia, was also one of Caesar’s lovers.

After his death, Caesar quickly became a martyr in the new Roman Empire. A mob of lower- and middle-class Romans gathered at Caesar’s funeral, with the angry crowd attacking the homes of Cassius and Brutus.

Just two years after his death, Caesar became the first Roman figure to be deified. The Senate also gave him the title “The Divine Julius.”

A power struggle ensued in Rome, leading to the end of the Roman Republic. Caesar’s great-grandnephew Gaius Octavian played on the late ruler’s popularity, assembling an army to fight back the military troops defending Cassius and Brutus. His victory over Caesar’s assassins allowed Octavian, who assumed the name Augustus, to take power in 27 BCE and become the first Roman emperor.

In November 2017, archaeologists announced the discovery of what they believed to be the first evidence of Caesar’s invasion of Britain in 54 BCE. The excavation of a new road in Ebbsfleet, Kent, revealed a 5-meter-wide defensive ditch and the remains of pottery and weapons. Experts from the University of Leicester and Kent County Council said the location was consistent with accounts of the invasion from the time period, and enabled them to pinpoint nearby Pegwell Bay as the likely landing spot for Caesar’s fleet.

Julius Caesar’s last days and the ensuing political clash between Octavian, Cassius, and Brutus have been famously captured in the five-act tragic play Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare . It was first produced in 1599 or 1600, around the opening of the Globe Theater, and continues to entertain audiences today. Joseph Mankiewicz ’s 1953 film adaptation of the play—starring Louis Calhern as Caesar, Marlon Brando as Mark Antony, James Mason as Brutus, and John Gielgud as Cassius—is one of the most enduring retellings on the silver screen.

- For the immortal gods are accustomed at times to grant favorable circumstances and long impunity to men whom they wish to punish for their crime, so that they may smart the more severely from a change of fortune.

- If you must break the law, do it to seize power: In all other cases, observe it.

- What we wish, we readily believe, and what we ourselves think, we imagine others think also.

- The res publica is nothing—a mere name without body or shape.

- You too, my child?

- Now that I am the leading Roman of my day, it will be harder to pull me down from first to second place than degrade me to the ranks.

- No, I am Caesar, not king.

- For those closest to a man ought not to allow his death to end their loyalty to him.

- An omen! A prodigy! Let us march where we are called by such a divine intimation. The die is cast.

- I merely want to protect myself against the slanders of my enemies.

- My aim is to outdo others in justice and equity, as I have previously striven to outdo them in achievement.

- I came, I saw, I conquered.

Citation Information

- Article Title : Julius Caesar Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- URL: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/julius-caesar

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 15, 2023

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Queen Elizabeth II

Marcus Aurelius

Pontius Pilate

Maria Theresa

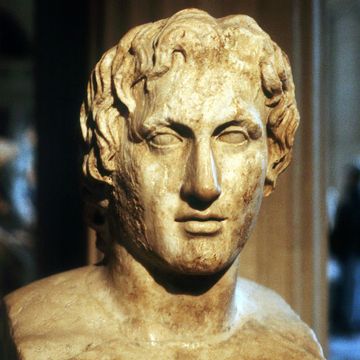

Alexander the Great

Nicholas II

Kaiser Wilhelm

Kublai Khan

William the Conqueror

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

Who Was Julius Caesar? A Short Biography

Colin Ricketts

30 jul 2018.

The most famous Roman of them all was never himself Emperor. But Julius Caesar’s military and political domination of Rome – as popular general, consul and finally dictator – made the switch from republican to imperial government possible.

Born to power

Caesar was born into the Roman political ruling class, on 12 or 13 July 100 BC.

He was named Gaius Julius Caesar, like his father and grandfather before him. Both had been republican officials, but the Julian clan’s greatest link to high power when Julius was born was through marriage. Caesar’s paternal aunt was married to Gaius Marius, a giant of Roman life and seven times consul.

Caesar learned early that Roman politics was bloody and factional. When Gaius Marius was overthrown by the dictator Sulla, the Republic’s new ruler came after his vanquished foe’s family. Caesar lost his inheritance – he was often in debt throughout his life – and he headed for the distant safety of overseas military service.

Once Sulla had resigned power, Caesar, who had proved himself a brave and ruthless soldier, began his political climb. He moved up the bureaucratic ranks, becoming governor of part of Spain by 61-60 BC.

Conqueror of Gaul

There is a story that in Spain and aged 33, Caesar saw a statue of Alexander the Great and wept because by a younger age, Alexander had conquered a vast empire.

He made it to the top as part of a team, joining forces with the massively wealthy Crassus and the popular general Pompey to take power as the First Triumvirate, with Caesar at its head as consul.

After his term ended he was sent to Gaul. Recalling Alexander the Great, he set upon a bloody campaign of eight years of conquest, which made him fantastically wealthy and powerful. He was now a popular military hero, responsible for Rome’s long-term safety and a huge addition to its northern territory.

Crossing the Rubicon

Pompey was now a rival, and his faction in the senate ordered Caesar to disarm and come home. He came home, but at the head of an army, saying “let the die be cast” as he crossed the Rubicon River to pass the point of no return. The ensuing four-year civil war sprawled across Roman territory leaving Pompey dead, murdered in Egypt, and Caesar undisputed leader of Rome.

Caesar now set about putting right what he thought was wrong with a Rome that was struggling to control its provinces and was riddled with corruption. He knew that the vast territories Rome now controlled needed a strong central power, and he was it.

He reformed and strengthened the state, acted on debt and over spending and promoted child birth to build Rome’s numerical strength. Land reform particularly favoured military veterans, the backbone of Roman power. Granting citizenship in new territories unified all of the Empire’s peoples. His new Julian Calendar, based on the Egyptian solar model, lasted until the 16th century.

Caesar’s assassination and civil strife

The Roman office of dictator was meant to grant extraordinary powers to an individual for a limited period in the face of crisis. Caesar’s first political enemy, Sulla, had overstepped those bounds but Caesar went further. He was dictator for just 11 days in 49 BC, by 48 BC a new term had no limits, and in 46 BC he was given a 10-year term. One month before he was killed that was extended to life.

Showered with further honours and powers by the Senate, which was packed with his supporters and which in any case he could veto, there were no practical limits on Caesar’s power.

The Roman Republic had rid the city of kings yet now had one in everything but name. A conspiracy against him was soon hatched, led by Cassius and Brutus, who Caesar may have believed was his illegitimate son.

On the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC, Caesar was stabbed to death by a group of around 60 men. The killing was announced with cries of: “People of Rome, we are once again free!” A civil war saw Caesar’s chosen successor, his great nephew Octavian, take power. Soon the republic really was over and Octavian became Augustus, the first Roman Emperor .

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Julius caesar.

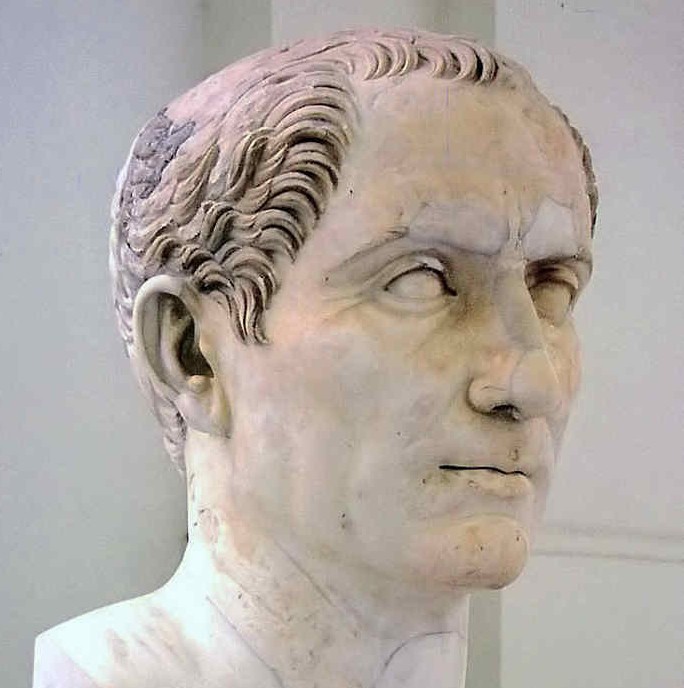

Julius Caesar was a Roman general and politician who named himself dictator of the Roman Empire, a rule that lasted less than one year before he was famously assassinated by political rivals in 44 B.C.

Anthropology, Archaeology, Social Studies, World History

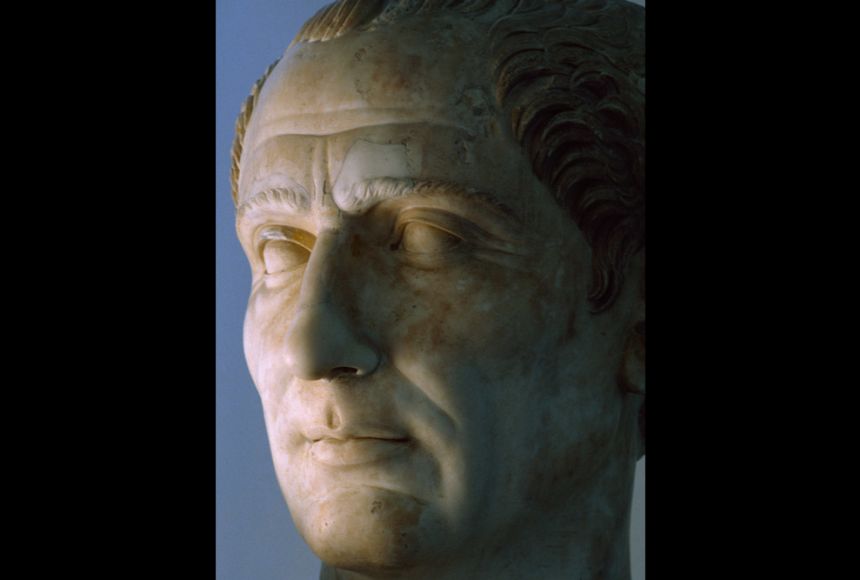

Gaius Julius Caesar was a crafty military leader who rose through the ranks of the Roman Republic, ultimately declaring himself dictator for life and shaking the foundations of Rome itself.

Photograph by James L. Stanfield, National Geographic

Julius Caesar was a Roman general and politician who named himself dictator of the Roman Empire, a rule that lasted less than one year before he was famously assassinated by political rivals in 44 B.C.E.

Caesar was born on July 12 or 13 in 100 B.C.E. to a noble family. During his youth, the Roman Republic was in chaos . Seizing the opportunity, Caesar advanced in the political system and briefly became governor of Spain, a Roman province.

Returning to Rome, he formed political alliances that helped him become governor of Gaul , an area that included what is now France and Belgium. His Roman troops conquered Gallic tribes by exploiting tribal rivalries . Throughout his eight-year governorship , he increased his military power and, more importantly, acquired plunder from Gaul . When his rivals in Rome demanded he return as a private citizen , he used these riches to support his army and marched them across the Rubicon River, crossing from Gaul into Italy. This sparked a civil war between Caesar’s forces and forces of his chief rival for power, Pompey, from which Caesar emerged victorious .

Returning to Italy, Caesar consolidated his power and made himself dictator . He wielded his power to enlarge the senate, created needed government reforms, and decreased Rome’s debt. At the same time, he sponsored the building of the Forum Iulium and rebuilt two city-states, Carthage and Corinth. He also granted citizenship to foreigners living within the Roman Republic.

In 44 B.C.E., Caesar declared himself dictator for life. His increasing power and great ambition agitated many senators who feared Caesar aspired to be king. Only a month after Caesar’s declaration, a group of senators, among them Marcus Junius Brutus, Caesar’s second choice as heir, and Gaius Cassius Longinus assassinated Caesar in fear of his absolute power.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Biography Online

Julius Caesar Biography

“Veni, Vidi, Vici.” “I came, I saw, I conquered.”

– Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was born into a noble family with a long pedigree of serving the Roman Republic. He gained a good education, but when he was 16 his father died, and it left Caesar in a difficult position due to an ongoing civil war which made his family a target. His inheritance was stripped from Caesar, leaving him with little money. He worked as an advocate and became known for his powerful oratory.

Surrender of Gallic chieftains after the Battle of Alesia (52 BC)

In 59 BC, Caesar was elected Consul to the Roman Senate, where he proposed a law to redistribute lands to the poor. However, this was opposed by many other senators. Instead, he was given command over Roman armies in northern Italy, southern France and southeastern Europe. Over the next seven years, Caesar led his armies to conquer large areas of Europe. It included modern-day France, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany and as far north as Britain. Despite, facing forces with greater numbers of men, the superior military capabilities and tactics of the Romans enabled Caesar to make a dramatic expansion of the Roman Empire. The historian Plutarch claimed that Caesar’s army fought over 3 million men, of which 1 million were killed, and approximately 800 cities were destroyed in the campaign. He is widely regarded as a pre-eminent military genius.

Caesar’s exploits made him popular with his soldiers and ordinary people back in Rome. However, his popularity only made his political enemies more nervous about Caesar and in 50 BC the Senate, led by Pompey, ordered Caesar to disband his army and return to Rome. Caesar had good reason to fear he would be tried and executed, but with the support of his soldiers and public opinion, he ignored the summons and returned to Rome with his army in tow. On 10 January 49 BC, he crossed the Rubicon river with one legion. As he crossed the river, he is said to have remarked. “The die is cast.”

Caesar then pursued and defeated armies loyal to Pompey. This allowed him to return in triumph to Rome, where he was re-elected to a second consulship.

Caesar pursued Pompey to Egypt, where Pompey was killed and Caesar formed an alliance with Cleopatra in an Egyptian civil war. With Caesar’s help, Cleopatra emerged victorious and she was installed as ruler of Egypt. Caesar and Cleopatra had an affair and produced a son Caesarian out of wedlock. Cleopatra visited Caesar in Rome.

Caesar gradually increased his power until he was proclaimed dictator for life. At the time, the Roman Empire was beset with corruption, fratricidal conflict and gross inequality. Caesar saw that Republican government was not working and he felt the only way to restore strong, stable government was through centralisation of power and authority in a strong leader. Although Caesar defeated supporters of Pompey in conflict, he was not as ruthless with political opponents as he might have done. He created many new loyal senators, but some old aristocratic senators remained.

As leader, Caesar tried to introduce many reforms into the Roman Empire, such as introducing a new calendar based on the Egyptian model of the sun, rather than the old system based on the moon. The Julian calendar began on 1 January 45 BC and is the basis for the modern western calendar. He also passed laws to redistribute power and wealth towards a greater section of society. He also sought to bring the Italian provinces into a more cohesive national unit. Caesar offered Roman citizenship to a greater scope of people. He published coins with his own image on. Despite ambitious plans to create a new constitution, he never enacted it.

The murder of Caesar

Despite Caesar’s power and popularity with the public, Senators were concerned that Caesar was heading towards a totalitarian state where the Senate would be completely abolished and they would lose increasing amounts of wealth and land due to Caesar’s policy of redistribution. Meeting in secret, senators, such as Gaius Cassius Longinus, Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, and Marcus Junius Brutus decided to murder Caesar while he was in the Senate as only senators were allowed there.

In the days leading up to the assassination, Caesar had received warnings his life was in danger, but in keeping with his personal outlook on life, he dismissed threats of his personal safety and ignored any extra measures for safety.

On 15 March 44 BC, the senators hid knives in their cloaks and then attacked Caesar on the steps of the Senate. His final words are disputed, but Caesar is said to have expressed surprise the senators turned on him. In his famous play, Shakespeare offered a fictional account with the famed words “Et Tu Brutus, then fall Caesar” Caesar died from multiple knife wounds.

In the aftermath of Caesar’s death, the Roman republic hastened to its demise – contrary to the aims of the conspirators. There was widespread mourning amongst the poorer sections of society for the loss of Caesar and the conspirators fled. Caesar had named his adoptive son Octavian as his heir. This led to a civil war between Mark Anthony and Octavian for control. Octavian prevailed and took the name, Caesar Augustus. Augustus went on to complete many of his father’s plans.

Julius Caesar became a powerful symbol of earthly power. He was by all accounts a charismatic figure, brilliant orator, powerful writer and someone who connected with ordinary people. He has a supreme self-confidence in his own abilities. His life and attitude is often summed up in his own words:

Veni, Vidi, Vici. “I came, I saw, I conquered.”

Caesar became a title imbued with almost god-like significance. The German Kaiser and Tzar in Russia are derived from Caesar.

He married three times. Cornelia (84–69 BC; her death) Pompeia (67–61 BC; divorced) Calpurnia (59–44 BC; his death) He only had one child born in wedlock – Julia with his first wife Cornelia. Julia was renowned for her beauty and virtue.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan. “ Biography of Julius Caesar” , Oxford, UK www.biographyonline.net , Published: 22 June 2019.

Caesar – by Adrian Goldsworthy (Authat Amazon

Culture History

Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar was a Roman military general, statesman, and dictator who played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. He was born in 100 BCE and was assassinated in 44 BCE. Caesar’s military conquests, political maneuvers, and eventual dictatorship significantly impacted the course of Roman history.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Julius Caesar’s early life and rise to power are integral parts of his historical narrative, shaping the trajectory of his political and military career. Born into a patrician family on July 12 or 13, 100 BCE, in Rome, Caesar hailed from a line that claimed descent from the goddess Venus. His family lacked the immense wealth of some Roman nobility, but they were well-connected politically.

Caesar’s father died when he was 16, leaving him with the responsibility of heading the family. Despite his father’s demise, Caesar received an excellent education, studying rhetoric, literature, and philosophy in Rome and Rhodes. His eloquence and oratorical skills, evident later in his political career, were honed during these formative years.

Caesar’s entry into public life began with his election as military tribune in 72 BCE. This position marked the start of his military service and provided him with the opportunity to showcase his leadership abilities. Subsequently, he served as quaestor in Hispania (present-day Spain) in 69 BCE, where he displayed administrative competence, albeit facing financial challenges. This early experience in both military and administrative roles laid the groundwork for his later achievements.

The turning point in Caesar’s career occurred when he formed a political alliance with two influential figures, Pompey and Crassus, creating the First Triumvirate in 60 BCE. Although an informal coalition rather than a legally sanctioned entity, the Triumvirate allowed the trio to pool their resources and influence Roman politics. Caesar’s alliance with Pompey, a military hero, and Crassus, one of the wealthiest Romans, bolstered his own political and military standing.

In 59 BCE, Caesar secured the powerful position of consul through the Triumvirate’s influence. His consulship marked a critical phase in his rise to power, as he navigated the complexities of Roman politics and consolidated support among the Roman populace. During his term, he pushed through legislation that addressed the land distribution issue, providing veterans with plots of land—a move that endeared him to the common people and strengthened his political base.

Caesar’s next significant step was obtaining the proconsulship of Gaul in 58 BCE. This appointment, which granted him command over Roman legions in Gaul (modern-day France, Belgium, and parts of Switzerland), was crucial for both military and political reasons. While Gaul was perceived as a province that required Roman control, it also provided Caesar with the opportunity to amass wealth and military glory.

Over the course of nearly a decade, from 58 BCE to 50 BCE, Caesar conducted a series of military campaigns in Gaul. His achievements in these campaigns showcased his strategic brilliance, tactical innovation, and an innate understanding of military logistics. The conquest of Gaul not only expanded Rome’s territories but also solidified Caesar’s reputation as a military genius.

Caesar’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico, his firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, demonstrates his prowess not only as a military commander but also as a skilled writer. The Commentarii served a dual purpose: narrating his military exploits for a Roman audience hungry for glory and shaping his own public image. Through these writings, Caesar skillfully portrayed himself as a capable and magnanimous leader, endearing himself to the Roman people.

While Caesar was achieving military success in Gaul, political tensions were escalating in Rome. His prolonged absence and accumulating power fueled suspicions among the Roman elite, particularly in the Senate. The triumviral arrangement with Pompey and Crassus began to unravel as Pompey aligned himself more closely with the Senate, distancing himself from Caesar.

The Senate, fearing Caesar’s growing influence and popularity, demanded that he disband his legions and return to Rome without the prospect of standing for consulship in absentia. However, Caesar was hesitant to comply, aware that returning to Rome without the protection of his armies could expose him to political and legal vulnerabilities.

The Rubicon River, a small waterway separating Gaul from Italy, became the symbolic threshold of Caesar’s defiance. Crossing the Rubicon in 49 BCE, Caesar uttered the famous phrase “alea iacta est” (“the die is cast”), signaling his decision to march on Rome and plunge the Republic into a civil war.

The ensuing conflict, known as the Roman Civil War, pitted Caesar against Pompey and the Senate. The decisive Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE resulted in Caesar’s victory, solidifying his control over the Roman state. Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was assassinated, and Caesar pursued his political adversaries, asserting dominance over Rome.

Upon returning to Rome, Caesar faced the challenge of consolidating power and implementing his vision for the Roman state. He embarked on a series of political and social reforms, aiming to address long-standing issues within Roman society. These reforms included the redistribution of land to veterans, the extension of Roman citizenship to more individuals, and the restructuring of the calendar into the Julian calendar.

Caesar’s political maneuvers, while applauded by the common people, stirred apprehension among those who cherished the traditional republican values. The Senate, fearing the concentration of power in one individual, grew increasingly uneasy. The culmination of these tensions unfolded on the Ides of March, March 15, 44 BCE, when a group of senators, including prominent figures like Brutus and Cassius, assassinated Caesar in the Theatre of Pompey.

Julius Caesar’s early life and rise to power reflect a complex interplay of political astuteness, military prowess, and the shifting dynamics of Roman society. From his humble beginnings to his triumphs in Gaul and the subsequent civil war, Caesar’s journey laid the groundwork for the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire . His legacy, marked by both admiration and controversy, remains a pivotal chapter in the annals of Western history.

Military Campaigns

Julius Caesar’s military campaigns stand as a testament to his strategic brilliance, bold leadership, and unparalleled military acumen. The most renowned of these campaigns occurred in Gaul, spanning from 58 BCE to 50 BCE, and were chronicled in Caesar’s own writings, Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War).

Caesar’s proconsulship in Gaul marked a turning point in his career. Initially, his assignment seemed routine, involving the pacification of a region that had seen frequent uprisings. However, the scale and intensity of his campaigns surpassed expectations, and his accomplishments in Gaul became the cornerstone of his military reputation.

The Gallic Wars commenced with Caesar’s intervention in the Helvetii migration in 58 BCE. The Helvetii, a Celtic tribe, sought to migrate westward, causing concern among Roman allies. Caesar, viewing their movement as a potential threat to Roman stability, decisively defeated them at the Battle of Bibracte, showcasing his strategic foresight and military prowess.

Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul were marked by a series of engagements against various Gallic tribes, each presenting unique challenges. The Battle of Gergovia in 52 BCE, against the ambitious chieftain Vercingetorix, demonstrated Caesar’s adaptability and resilience. Though Caesar faced setbacks in this campaign, including a failed siege and a retreat, he ultimately regrouped and emerged victorious in the Siege of Alesia, effectively quelling the Gallic resistance.

A significant aspect of Caesar’s success in Gaul was his ability to forge alliances and divisions among the Gallic tribes. His diplomatic skill, coupled with a thorough understanding of local politics, allowed him to exploit internal rivalries and weaken Gallic unity. This divide-and-conquer strategy played a pivotal role in securing Roman dominance.

The Battle of Alesia, fought in 52 BCE, was a masterstroke in military strategy. Vercingetorix, recognizing the impending Roman siege, gathered Gallic forces in a fortified position. Caesar, undeterred, surrounded Alesia with a double fortification—a circumvallation to repel external reinforcements and a contravallation to defend against potential counterattacks. The Roman legions endured harsh conditions but ultimately prevailed, showcasing Caesar’s logistical prowess and strategic vision.

As Caesar continued to subjugate Gaul, his military campaigns extended beyond the borders of modern France. In 55 BCE and 54 BCE, he conducted two expeditions to Britain, seeking to expand Roman influence and gather intelligence. While the expeditions did not result in permanent conquests, they demonstrated Caesar’s audacity and willingness to explore new frontiers.

The Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE marked a critical juncture in Caesar’s military career. Facing off against Pompey, his former ally turned adversary, Caesar employed tactical brilliance to secure victory. Despite being outnumbered, Caesar exploited weaknesses in Pompey’s strategy, decisively defeating him. The Battle of Pharsalus solidified Caesar’s control over the Roman state, making him the undisputed master of Rome.

The Egyptian Campaign in 47 BCE showcased Caesar’s military prowess and political acumen. Following the Battle of Pharsalus, Caesar pursued Pompey to Egypt, where he became embroiled in the Egyptian civil war between Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy XIII. Caesar intervened decisively, aligning with Cleopatra and ensuring her ascent to the throne. This strategic move not only secured an alliance with Egypt but also showcased Caesar’s ability to navigate complex political landscapes.

Caesar’s military campaigns were characterized by a combination of strategic brilliance, tactical innovation, and adaptability. His legions, known for their discipline and loyalty, formed the backbone of his military success. Caesar’s personal leadership style, characterized by hands-on involvement in battles and the welfare of his troops, earned him the unwavering loyalty of his legions.

The Siege of Uxellodunum in 51 BCE, toward the end of the Gallic Wars, further demonstrated Caesar’s tenacity. The fortress of Uxellodunum, held by Gallic rebels, withstood a prolonged Roman siege. However, Caesar, determined to break the resistance, implemented a ruthless strategy. Upon capturing the stronghold, he imposed harsh penalties on the defenders, including cutting off the hands of those who had borne arms—an act that exemplified his resolve in maintaining Roman authority.

The military campaigns of Julius Caesar, while securing his position as a legendary commander, also raised concerns among the Roman elite. The prolonged duration of his proconsulship, coupled with his military successes, fueled fears of his growing power and ambitions. The crossing of the Rubicon River in 49 BCE, signaling the beginning of the Roman Civil War, marked a point of no return and set the stage for the eventual demise of the Roman Republic.

First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate, a political alliance formed in 60 BCE, played a pivotal role in shaping the course of Roman history, paving the way for the rise of Julius Caesar and the eventual transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire. Comprising three influential figures—Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey), and Marcus Licinius Crassus—the Triumvirate represented a strategic coalition of military prowess, political maneuvering, and financial influence.

Julius Caesar, a rising political figure known for his military exploits and charisma, formed a crucial part of the Triumvirate. Born into a patrician family, Caesar’s early political career saw him ascending through the Roman offices, showcasing his abilities as both a military commander and a shrewd politician. By aligning with Pompey and Crassus, Caesar sought to consolidate power and navigate the intricate political landscape of the late Roman Republic.

Pompey, also known as Pompey the Great, was a celebrated military general who had achieved fame through his victories in the East. Having been a part of the First Triumvirate, Pompey’s alliance with Caesar marked a notable shift in Roman politics. Initially, Pompey’s military prowess and popularity garnered him significant influence, but he found himself increasingly at odds with the Senate. The Triumvirate provided him with a powerful alliance to counterbalance the Senate’s influence and safeguard his interests.

Crassus, the wealthiest man in Rome at the time, was a seasoned politician and military commander. His financial resources were crucial in supporting the political aspirations of both Caesar and Pompey. Despite his wealth, Crassus sought military glory to match his political standing, and the Triumvirate offered him an opportunity to pursue his ambitions. Together, the three men formed a formidable trio that could effectively challenge the traditional power structures within the Roman Republic.

The formation of the Triumvirate was facilitated by mutual interests and complementary strengths. Caesar, as consul in 59 BCE, played a key role in brokering the alliance. The political landscape at the time was fraught with tensions, with various factions vying for control. Caesar’s consulship allowed him to shape the political climate in favor of the Triumvirate.

One of the earliest manifestations of the Triumvirate’s power was the passing of legislation known as the Lex Julia, which addressed the distribution of land to Pompey’s veterans and provided support for Caesar’s legislative agenda. This marked the beginning of the Triumvirate’s collaborative efforts in pursuing their individual goals while collectively challenging the Senate’s authority.

To solidify their alliance, Caesar gave his daughter Julia in marriage to Pompey, creating a familial tie between the two leaders. This marital connection was intended to strengthen the bonds of the Triumvirate, emphasizing the personal relationships that underpinned its political cohesion.

Despite the appearance of unity, tensions within the Triumvirate began to surface. The death of Julia in 54 BCE dealt a significant blow to the personal ties between Caesar and Pompey. Without this familial link, the Triumvirate faced strains as personal ambitions and conflicting interests took precedence.

Crassus’s death in 53 BCE further destabilized the alliance. His defeat at the Battle of Carrhae against the Parthians marked the end of his military aspirations and left a power vacuum within the Triumvirate. With Crassus gone, the delicate balance of power tilted, setting the stage for the eventual rivalry between Caesar and Pompey.

The breakdown of the Triumvirate became evident as Caesar’s proconsulship in Gaul drew to a close. The Senate, sensing an opportunity to curb Caesar’s influence, sought to limit his power upon his return to Rome. Pompey, once Caesar’s ally, found himself torn between loyalty to the Senate and maintaining a semblance of alliance with Caesar.

The situation reached a critical juncture in 50 BCE when the Senate demanded that Caesar disband his legions and return to Rome without the prospect of standing for consulship in absentia. Caesar, reluctant to expose himself to political vulnerability, chose to defy the Senate’s orders. Crossing the Rubicon River in 49 BCE, he famously declared, “alea iacta est” (“the die is cast”), initiating a civil war that would determine the fate of the Roman Republic.

The ensuing conflict, known as the Roman Civil War, pitted Caesar against Pompey and the Senate. Despite the historical camaraderie between Caesar and Pompey, the breakdown of the Triumvirate led to a bitter rivalry. The decisive Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE resulted in Caesar’s victory, marking a turning point in Roman history.

Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was ultimately assassinated. Caesar, upon arriving in Egypt, became embroiled in the Egyptian civil war between Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy XIII. His intervention on Cleopatra’s behalf further showcased the intersection of political and military dynamics in the wake of the Triumvirate’s dissolution.

The legacy of the First Triumvirate lies in its role as a catalyst for the unraveling of the Roman Republic. While the alliance initially served the interests of its members, personal ambitions, conflicting goals, and external pressures led to its disintegration. The breakdown of the Triumvirate set the stage for the rise of Julius Caesar and the subsequent shift from republic to empire, marking a transformative period in Roman history.

Crossing the Rubicon

The crossing of the Rubicon River by Julius Caesar in 49 BCE is a historic event that reverberated through the annals of Roman history, signaling the beginning of a civil war and ultimately leading to the demise of the Roman Republic. This fateful decision, immortalized by the phrase “alea iacta est” (“the die is cast”), marked a point of no return and set in motion a series of events that would reshape the political landscape of ancient Rome .

The Rubicon River served as a natural boundary between Cisalpine Gaul, where Julius Caesar held command, and the Roman Republic proper. Roman law strictly forbade any general from bringing an army across this river and into the Italian peninsula. This prohibition was designed to prevent military leaders from using their legions to seize power within Rome. The crossing of the Rubicon was, therefore, a direct challenge to the authority of the Roman Senate.

The events leading to Caesar’s decision to cross the Rubicon were rooted in the complex political dynamics of the time. The First Triumvirate, a political alliance formed in 60 BCE between Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus, had begun to unravel. The death of Crassus in 53 BCE created a power vacuum, and the subsequent death of Pompey’s wife, Julia (Caesar’s daughter), severed one of the personal ties that had bound the triumvirs together.

As Caesar’s proconsulship in Gaul neared its end in 50 BCE, the Senate, led by Pompey and his allies, sought to curtail Caesar’s influence upon his return to Rome. The Senate demanded that Caesar disband his legions and return to Rome without standing for consulship in absentia. This move was a calculated attempt to weaken Caesar’s political standing and prevent him from leveraging his military success in Gaul for further political gains.

Caesar, aware of the potential consequences of yielding to the Senate’s demands, faced a dilemma. Returning to Rome without the protection of his legions could expose him to political and legal vulnerabilities. The Senate, dominated by Pompey’s faction, had already demonstrated its intent to curb Caesar’s influence. The alternative, however, meant defying Roman law and initiating a civil war.

On January 10, 49 BCE, Caesar stood on the northern bank of the Rubicon with his legions. The Rubicon was not just a physical barrier; it represented the legal limit to a general’s authority. Caesar, contemplating the gravity of his decision, knew that crossing the Rubicon would trigger a conflict with the Senate, possibly leading to a civil war. The phrase “alea iacta est” is attributed to Caesar at this moment, signifying his acceptance of the irreversible course of action.

Caesar’s decision to cross the Rubicon was marked by both audacity and strategic calculation. Crossing the river with his army meant violating Roman law, an act that would bring about severe consequences. It was a move that would either secure his political survival or lead to his downfall. The die was cast, and there was no turning back.

The crossing of the Rubicon set off a chain reaction of events that unfolded rapidly. Caesar moved swiftly towards Rome, facing minimal resistance as many cities, including Ariminum and Rimini, opened their gates to him. The Senate, caught off guard, scrambled to respond to the sudden and bold advance of Caesar’s forces.

Pompey, realizing the gravity of the situation, opted to abandon Rome and retreat to the south. He hoped to gather forces, consolidate support, and prepare for a confrontation with Caesar. The strategic maneuvering on both sides marked the beginning of the Roman Civil War, a conflict that would determine the fate of the Roman Republic.

Caesar’s march towards Rome was marked by a series of decisive actions, including the capture of key cities and the securing of strategic alliances. The speed and efficiency of his movements showcased not only the loyalty of his legions but also the effectiveness of his military strategy.

The Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE was the climactic encounter of the Roman Civil War. It pitted Caesar against Pompey in a showdown that would decide the fate of the Republic. Despite being outnumbered, Caesar’s tactical brilliance and the discipline of his legions prevailed. The defeat of Pompey marked a turning point in Roman history, solidifying Caesar’s control over Rome.

The consequences of crossing the Rubicon were profound and far-reaching. By challenging the Senate’s authority, Caesar effectively ended the Roman Republic’s tradition of peaceful transitions of power. The political norms that had guided Rome for centuries were shattered, and the stage was set for the rise of autocratic rule.

Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon and the subsequent civil war led to a series of political and institutional changes. Caesar was appointed dictator perpetuo (dictator in perpetuity), consolidating unprecedented power in his hands. The Senate, stripped of its authority, became a symbolic body with limited influence. Caesar’s reforms, including the restructuring of the calendar into the Julian calendar, further reflected his imprint on Roman governance.

The crossing of the Rubicon and the events that followed culminated in the assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March in 44 BCE. While Caesar’s actions had transformed the political landscape, his death sparked new conflicts and power struggles. The vacuum left by Caesar’s demise ultimately paved the way for the rise of Caesar’s adopted heir, Octavian (later known as Augustus), and the establishment of the Roman Empire.

Dictatorship

Julius Caesar’s ascent to dictatorship marked a transformative period in Roman history, profoundly altering the political landscape and leading to the demise of the Roman Republic. From his crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BCE to his assassination on the Ides of March in 44 BCE, Caesar’s dictatorial rule left an indelible impact on Rome and set the stage for the subsequent transition from republic to empire.

Caesar’s appointment as dictator perpetuo (dictator in perpetuity) was a culmination of a series of events that unfolded during the Roman Civil War. The conflict emerged from the breakdown of the First Triumvirate, the political alliance between Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus. With Crassus dead and Pompey aligning himself with the Senate, Caesar found himself at odds with the Roman political establishment.

The crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BCE was a decisive move that set the Roman Civil War into motion. Caesar, aware of the political risks, defied the Senate’s orders and marched his legions into Italy. The ensuing conflict saw decisive battles, including the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE, where Caesar emerged victorious, securing control over Rome.

Caesar’s rise to dictatorship was facilitated by the breakdown of traditional Roman political norms. The Senate, once the primary governing body, found itself weakened and unable to resist Caesar’s growing power. The dictator perpetuo title, bestowed upon Caesar by the Senate in 44 BCE, granted him unprecedented authority, effectively making him the sole ruler of Rome.

As dictator, Caesar implemented a series of reforms aimed at addressing social and political issues within the Roman Republic. His policies reflected a blend of pragmatism and a desire for populist support. One significant reform was the distribution of land to veterans, a move intended to reward his loyal soldiers and alleviate social tensions in Rome.

Caesar’s agrarian reforms aimed at providing land to the poor, particularly those who had served in his legions during the Gallic Wars. This measure not only helped secure the loyalty of his veteran soldiers but also endeared him to the urban poor, a significant constituency in Roman politics. By addressing issues of land distribution, Caesar sought to strengthen his support base and foster social stability.

In addition to domestic reforms, Caesar initiated changes to the Roman calendar, which resulted in the adoption of the Julian calendar. This calendar, named after Caesar, introduced a 365-day year with a leap year, aligning more closely with the solar year. The Julian calendar, with later adjustments, formed the basis for the modern Gregorian calendar.

While Caesar’s reforms addressed immediate concerns and garnered support from certain segments of society, they also raised concerns among those who cherished the traditional republican values. The concentration of power in the hands of a single individual contradicted the foundational principles of the Roman Republic, where power was meant to be distributed among elected officials.

The Senate, despite its diminished influence, remained a symbol of republican governance. The traditionalists within the Senate feared Caesar’s autocratic rule and resented the erosion of their authority. Tensions between Caesar and the Senate persisted, as exemplified by incidents like the infamous refusal to rise in his honor and the offer of a crown during the Lupercalia festival, which Caesar rejected to avoid the appearance of aspiring to kingship.

Caesar’s refusal to accept the crown at the Lupercalia festival demonstrated his awareness of the sensitivities surrounding monarchical symbols in Rome. Despite his dictatorial powers, Caesar was mindful of the need to maintain a facade of republican governance to appease those who still clung to the ideals of the Roman Republic.

The term “dictator perpetuo” itself reflected a delicate balance. While the title conferred immense power upon Caesar, it retained a semblance of legality by maintaining the term “dictator,” a position traditionally appointed during times of crisis and for a limited duration. However, the open-ended nature of Caesar’s dictatorship, combined with his accumulation of various titles and offices, effectively concentrated power in his hands without the checks and balances inherent in the Roman system.

Caesar’s rule, despite its transformative nature, faced significant opposition. The Senate, led by figures like Brutus and Cassius, viewed Caesar as a threat to the republican order and conspired against him. The assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March in 44 BCE, carried out by a group of senators, including some of his closest associates, marked a dramatic turn of events.

The assassination of Caesar did not restore the Roman Republic but, instead, plunged Rome into a new round of civil wars. The power vacuum left by Caesar’s death led to a struggle for control, with figures like Octavian (Caesar’s adopted heir), Mark Antony , and Marcus Lepidus forming the Second Triumvirate. This alliance sought to avenge Caesar’s death, eliminate his assassins, and reestablish control over Rome.

The Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE resulted in the defeat of the forces led by Brutus and Cassius, solidifying the Triumvirs’ control over Rome. In the aftermath, internal conflicts between Octavian and Antony arose, eventually leading to the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. Octavian emerged victorious, and in 27 BCE, he became the first Roman Emperor, marking the official transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire.

The dictatorship of Julius Caesar, while short-lived, left an enduring impact on the course of Roman history. His rule highlighted the vulnerabilities of the Roman Republic and underscored the challenges inherent in maintaining a balance between republican ideals and the practical demands of governance. The events following Caesar’s assassination paved the way for the establishment of the Roman Empire, fundamentally altering the nature of Roman governance and influencing the trajectory of Western civilization .

Assassination

The assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March in 44 BCE stands as one of the most consequential events in Roman history, triggering a chain reaction that ultimately led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. This dramatic act, carried out by a group of senators including some of Caesar’s closest associates, exposed the deep-seated tensions within Roman society and the struggle for power in the wake of Caesar’s dictatorial rule.

The political landscape leading up to Caesar’s assassination was marked by a complex web of alliances, rivalries, and shifting loyalties. Julius Caesar, having crossed the Rubicon in 49 BCE and defeated his adversaries in the Roman Civil War, had consolidated unprecedented power as dictator perpetuo. While some supported his autocratic rule, others viewed him as a threat to the traditional republican order.

The Senate, the symbolic heart of Roman governance, found itself marginalized and resentful of Caesar’s concentration of power. The traditionalists within the Senate, led by figures like Cassius and Brutus, feared that the Republic’s foundational principles were being eroded, and Rome was veering towards a one-man rule. The idea of a monarch, a concept anathema to Roman republican ideals, loomed large in their minds.

The conspirators against Caesar, commonly known as the Liberators, comprised a mix of senators, military officers, and politicians. Cassius Longinus, a senator with a deep-seated resentment toward Caesar, played a prominent role in organizing the conspiracy. Brutus, despite his close association with Caesar and his familial ties, was persuaded to join the plot by Cassius and others who saw him as a figurehead capable of garnering broader support.

The conspirators framed their actions as a noble endeavor to preserve the Roman Republic and prevent the emergence of a tyrant. They believed that eliminating Caesar would restore the traditional balance of power and protect the republican institutions that had defined Roman governance for centuries.

The stage was set on the Ides of March, March 15, 44 BCE, when Caesar was scheduled to attend a meeting of the Senate at the Theatre of Pompey. The conspirators, armed with daggers and driven by a sense of duty, positioned themselves among the senators. Caesar, perhaps influenced by his overconfidence or a disregard for the warnings he had received, proceeded to the Senate, unaware of the imminent threat.

As Caesar entered the Senate chamber, the conspirators surrounded him, and the first dagger was drawn. According to historical accounts, the initial stab came from Casca, one of the conspirators, followed by a frenzied onslaught of blows from multiple assailants. The sheer number of wounds inflicted upon Caesar, including the infamous participation of Brutus, reflected the intensity of the conspirators’ resolve.

The assassination of Julius Caesar unfolded in a chaotic and brutal manner. The act itself, while shocking, was symbolic of the deep-seated anxieties and conflicting visions for the future of Rome. The conspirators, in their bid to preserve the republic, resorted to political violence, setting off a series of events that would have profound consequences for the Roman state.

Contrary to the conspirators’ expectations, the assassination did not result in the restoration of the Roman Republic. Instead, it plunged Rome into a new round of turmoil. The vacuum left by Caesar’s death led to power struggles among various factions vying for control. The Liberators, far from being hailed as saviors, were met with hostility from the Roman populace.

Mark Antony, Caesar’s loyal supporter, skillfully exploited the public sentiment against the conspirators. His funeral oration, delivered at Caesar’s funeral, stirred emotions and turned public opinion against the Liberators. The phrase “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears” from Antony’s speech is immortalized by William Shakespeare and captures the rhetorical prowess employed to manipulate the crowd’s sentiments.

The events following Caesar’s assassination culminated in the formation of the Second Triumvirate, an alliance between Octavian (Caesar’s adopted heir), Mark Antony, and Marcus Lepidus. This coalition sought to avenge Caesar’s death, eliminate his assassins, and restore order to Rome. The Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE resulted in the defeat of the forces led by Brutus and Cassius, solidifying the Triumvirs’ control over Rome.

The assassination of Julius Caesar and its aftermath highlighted the fragility of the Roman political system. The republic, once a bastion of stability and civic virtue, succumbed to internal strife and external threats. The ideals of the Roman Republic, built on the principles of checks and balances, were compromised by the pursuit of personal power and the erosion of political norms.

The demise of the Roman Republic paved the way for the emergence of the Roman Empire. Octavian, later known as Augustus, capitalized on the political chaos to consolidate power and establish the principate. In 27 BCE, he became the first Roman Emperor, marking the formal transition from the republic to the empire.

The assassination of Julius Caesar remains a compelling and often debated episode in history. Some view it as a tragic attempt to salvage the republic, while others see it as a futile effort that ultimately contributed to the erosion of the very values the conspirators sought to protect. Regardless of one’s interpretation, the events surrounding Caesar’s death underscore the complex interplay of power, ambition, and political ideals in the tumultuous tapestry of Roman history.

Impact on Rome

The assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March in 44 BCE had profound and far-reaching consequences, reshaping the political landscape of Rome and setting the stage for the transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire. The impact of Caesar’s death reverberated through the city, triggering a series of events that would ultimately redefine the nature of Roman governance.

One immediate effect of Caesar’s assassination was the eruption of political turmoil and civil unrest in Rome. The vacuum left by Caesar’s death created a power struggle among various factions vying for control. The conspirators, known as the Liberators, failed to gain the support they anticipated from the Roman populace. Instead, they faced hostility, as many citizens viewed Caesar as a popular and benevolent leader who had brought stability to Rome.

Mark Antony, Caesar’s loyal supporter, skillfully capitalized on the public sentiment against the conspirators. His funeral oration, delivered at Caesar’s funeral, incited a wave of anger and indignation among the Roman citizens. The crowd, moved by Antony’s rhetoric, turned against the Liberators, whom they now saw as traitors to the memory of the fallen leader.

The events following Caesar’s assassination led to the formation of the Second Triumvirate, an alliance between Octavian (Caesar’s adopted heir), Mark Antony, and Marcus Lepidus. This coalition was driven by a shared desire to avenge Caesar’s death, eliminate his assassins, and restore order to Rome. The Triumvirs initiated a series of proscriptions, targeting those deemed enemies of the state. Brutus and Cassius, among other conspirators, were hunted down and met their demise in the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE.

The aftermath of the civil war marked a significant turning point for Rome. The Second Triumvirate, despite achieving its immediate objectives, faced the challenge of maintaining stability and consolidating power. The power-sharing agreement between Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus was tenuous, and internal tensions within the triumviral alliance began to surface.

The relationship between Octavian and Antony, in particular, became strained. Antony, captivated by his affair with Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt, drifted away from Rome both politically and personally. Octavian, meanwhile, sought to secure his position and extend his influence within the Roman state.

The Battle of Actium in 31 BCE marked the culmination of the power struggle between Octavian and Antony. Octavian’s fleet, under the command of Agrippa, decisively defeated the combined forces of Antony and Cleopatra. The defeat led to Antony and Cleopatra’s suicides, and Octavian emerged as the sole master of Rome.

In 27 BCE, Octavian officially restored power to the Roman Senate, claiming to have returned the republic to its traditional form. However, his actions spoke otherwise. Octavian, now hailed as Augustus, became the first Roman Emperor, marking the beginning of the Roman Empire. The transition from republic to empire marked a profound transformation in the structure of Roman governance.

The impact of Caesar’s assassination on Rome extended beyond the political realm. It had social, cultural, and economic repercussions that reshaped the fabric of Roman society. The proscriptions initiated by the Second Triumvirate resulted in the purging of individuals deemed enemies of the state. This led to widespread bloodshed, as citizens were targeted for their wealth, political affiliations, or perceived threats to the triumvirs’ authority.

The proscriptions also had economic consequences. Confiscation of property and assets from the proscribed individuals contributed to a redistribution of wealth within Roman society. The ensuing instability and fear further weakened the foundations of the Roman Republic, as citizens grappled with the consequences of political violence and uncertainty.

The transition from republic to empire initiated a shift in cultural and societal values. The Roman Republic, with its emphasis on civic virtue and shared governance, gave way to the autocratic rule of the emperors. Augustus, in particular, sought to restore traditional Roman values, emphasizing the importance of moral conduct, family, and public service. The concept of the “Pax Romana” (Roman Peace) emerged during the early years of the empire, reflecting a period of relative stability and prosperity.

The imperial system introduced a new dynamic to Roman society. The emperors, while often holding absolute power, needed to balance the support of the army, Senate, and populace to maintain stability. Augustus, in crafting the image of the principate, presented himself as the “first citizen” rather than a monarch. This subtle manipulation of political symbols aimed to preserve the illusion of a restored republic while consolidating imperial authority.

The architectural landscape of Rome also underwent significant changes during the imperial period. Augustus initiated a series of monumental building projects, including the construction of the Forum of Augustus and the completion of the Temple of Caesar. These structures served not only as symbols of imperial grandeur but also as tools for shaping public perception and reinforcing the legitimacy of Augustus’s rule.

The impact of Caesar’s assassination on Rome was multi-faceted, leaving an enduring imprint on the city’s history and trajectory. The assassination itself marked the end of the Roman Republic, but the subsequent power struggles and transformations paved the way for the establishment of the Roman Empire. The transition from republic to empire ushered in an era of autocratic rule marked by the concentration of power in the hands of emperors, fundamentally altering the nature of Roman governance and shaping the course of Western civilization .

The establishment of the Roman Empire brought about a consolidation of authority, but it also raised questions about the balance between individual power and the principles of the Roman Republic. Augustus, the first emperor, skillfully navigated these complexities, presenting himself as a restorer of traditional Roman values while simultaneously wielding unprecedented authority.

The imperial system introduced a new administrative structure with a centralization of power in the emperor’s hands. While the Senate continued to exist, its role evolved into one of advisory rather than legislative. The emperor’s will, backed by the military, became the ultimate authority in matters of governance. This shift in political dynamics had a lasting impact on the Roman political psyche.

The imperial period also witnessed an expansion of Roman territory and influence. Under emperors like Trajan and Hadrian, the Roman Empire reached its greatest territorial extent, encompassing vast regions from Britannia to Mesopotamia. This expansion brought about cultural exchange, economic prosperity, and the spread of Roman influence, but it also posed challenges in terms of governance and administration.

The concept of citizenship underwent changes during the imperial era. While citizenship had been a prized status in the Roman Republic, the emperors extended it to various communities within the empire as a means of fostering loyalty and integration. This inclusive approach, known as the “Romanization” of the empire, sought to bind diverse regions under a common Roman identity.

The imperial period also witnessed the flourishing of Roman literature, art, and architecture. Augustan literature, often characterized by poets like Virgil and Horace, celebrated the virtues of the new imperial age. Roman art and architecture reflected a fusion of classical styles with innovative elements, leaving a legacy that influenced later artistic traditions.

Economically, the Roman Empire experienced both prosperity and challenges. The integration of diverse regions into a unified economic system facilitated trade, agricultural development, and technological advancements. However, issues such as taxation, economic inequality, and occasional financial crises also posed challenges to the stability of the empire.

The imperial succession became a critical factor in the longevity and stability of the Roman Empire. While some emperors, like Augustus and Trajan, were successful in securing smooth successions, others faced instability and conflict. The adoption of heirs, as exemplified by emperors such as Nerva adopting Trajan, became a strategic means of ensuring continuity.

Despite its strengths, the Roman Empire faced internal and external threats. Internally, issues such as political corruption, economic disparities, and military challenges posed significant risks. Externally, the empire contended with invasions by Germanic tribes, the Parthians in the east, and later, the formidable Sassanian Empire.

The decline of the Roman Empire, often attributed to a combination of internal and external pressures, unfolded gradually over centuries. Factors such as political instability, economic challenges, military decline, and the sheer vastness of the empire contributed to its eventual fragmentation. The division of the Roman Empire into the Western and Eastern Roman Empires marked a pivotal moment, with the Western Roman Empire succumbing to external pressures in 476 CE.

The legacy of Rome, however, endured. The Roman Empire’s contributions to law, governance, architecture, engineering, language, and culture left an indelible mark on subsequent civilizations. The principles of Roman law, embodied in the Justinian Code, continued to influence legal systems throughout Europe. The Latin language evolved into the Romance languages, and Roman engineering marvels such as aqueducts and roads persisted for centuries.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Julius Caesar

By kristen richard | feb 20, 2020.

MILITARY (0100–0044); ROME, ITALY

A powerful politician, army general, and emperor, Julius Caesar helped transform Rome into one of the most powerful empires in history. Caesar was beloved by many; however, his power also garnered much resentment from his fellow politicians. Read on for more about Caesar's life, his affair with Cleopatra, his assassination, and the famous William Shakespeare play that helped immortalize him, despite taking plenty of liberties with the true story.

1. Julius Caesar was born on either July 12 or 13, 100 BCE, but likely not via cesarean section.

For centuries, it was believed Julius Caesar was the first baby born via Cesarean section, but that's likely far from the truth. A 10th-century Byzantine-Greek historical encyclopedia called may be the source of the confusion, since it claims C-sections got their name from Caesar himself, stating :

"The emperors of the Romans receive this name from Julius Caesar, who was not born. For when his mother died in the ninth month, they cut her open, took him out, and named him thus; for in the Roman tongue dissection is called ‘Caesar.’"

The story, however, is highly unlikely for several reasons. First, C-sections were already performed in Rome at the time. For centuries, there was a law that required C-sections be performed under certain circumstances, which was instated during the reign of Numa Pompilius , who ruled from 715–673 BCE, long before Caesar.

According to the law, if a woman died while pregnant, she had to undergo a C-section, because it was against Roman beliefs to bury a mother with her baby in her womb. The law also stated that dying pregnant women must undergo a C-section to attempt to save the life of the baby. The Suda mistakenly says Caesar’s mother, Aurelia Cotta, died during childbirth. But we know Caesar's mother lived well into his adulthood, and some historians believe she may have even outlived him, so it's unlikely she underwent a C-section and survived.

2. William Shakespeare’s play The Tragedy of Julius Caesar left out a key player in Julius Caesar’s assassination.

William Shakespeare’s play, The Tragedy of Julius Caesar , is set in 44 BCE . It explores what lead to the assassination of Caesar and the aftermath. One of the most famous quotes from the play, uttered by Caesar upon his death, is “ et tu, Brute ?” or “and you, Brutus?” But Caesar didn’t actually say that; he didn’t even know Brutus particularly well.

The real traitor was Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus . However, he was barely mentioned in the play, and his name was spelled incorrectly. In actuality, he was like a friend to Caesar. The emperor even gave him a job in politics to help restore the name of his disgraced family, and they fought alongside each other in battle. But in the end, Decimus played a key role in the assassination.

3. Julius Caesar and Cleopatra had an affair that led to a son named Caesarion.

Caesar and Cleopatra’s affair was about more than lust; it was a relationship the both of them needed to reach their own goals. For Cleopatra to secure her place on Egypt's throne, she needed an army; more accurately, she needed Caesar's vast army. On Caesar's end, he needed access to Cleopatra's incredible wealth (imagine a fortune far greater than Bill Gates 's today) to pay off debts and keep his own position in power. Cleopatra would eventually go to Rome with Caesar, where he was apparently very open about their affair. Together, they had a son, Caesarion , and Caesar's public displays of affection even included having a statue erected of Cleopatra in Rome's Temple of Venus Genetrix. She remained in Rome until Caesar was assassinated , which ultimately forced her and her son to flee.

4. Julius Caesar was assassinated on March 15, 44 BCE, after he was stabbed 23 times.

In 44 BCE, Caesar declared himself dictator for life. While many of his changes and reforms were well-received by lower- and middle-class populations , other politicians grew anxious about his ever-growing power. The animosity eventually boiled over, and on March 15, 44 BCE, the emperor was stabbed to death by what's been described as a group of approximately 40 senators.

5. Julius Caesar was Kidnaped by Pirates and demanded they ask for a higher ransom.

When Caesar was 25 years old, he was sailing the Aegean Sea and was kidnaped by Cicilian pirates . The pirates said they were going to demand 20 talents of silver (about $600,000 today), but, apparently, Caesar laughed in their face and told them they should ask for 50 (about 1550 kg of silver). While his associates went off to get the ransom, Caesar was forced to wait in captivity as the money was gathered and delivered. After he was freed, he gathered a small group of soldiers, hunted the pirates down, slit their throats, and took his silver back.

6. Julius Caesar had three wives during his life.

Caesar married Cornelia , his first wife, in 84 BCE. They had a daughter together but Cornelia died in 69 BCE. In 67 BCE, he married Pompeia, who he later divorced. Julius Caesar then married Calpurnia in 59 BCE, and they remained together until his death.

7. You Can visit the site Where Julius Caesar was assassinated.

Largo di Torre Argentina is Rome’s oldest open-air square, and it was where Caesar was stabbed around 23 times on March 15, 44 BCE. It fell into disrepair during the following centuries, but after a $1.1 million restoration project, the historic site will be open to the public in 2021.

8. A bust thought to be of Julius Caesar was found in 2007.