Literature Reviews

- Introduction

- Tutorials and resources

- Step 1: Literature search

- Step 2: Analysis, synthesis, critique

- Step 3: Writing the review

If you need any assistance, please contact the library staff at the Georgia Tech Library Help website .

Analysis, synthesis, critique

Literature reviews build a story. You are telling the story about what you are researching. Therefore, a literature review is a handy way to show that you know what you are talking about. To do this, here are a few important skills you will need.

Skill #1: Analysis

Analysis means that you have carefully read a wide range of the literature on your topic and have understood the main themes, and identified how the literature relates to your own topic. Carefully read and analyze the articles you find in your search, and take notes. Notice the main point of the article, the methodologies used, what conclusions are reached, and what the main themes are. Most bibliographic management tools have capability to keep notes on each article you find, tag them with keywords, and organize into groups.

Skill #2: Synthesis

After you’ve read the literature, you will start to see some themes and categories emerge, some research trends to emerge, to see where scholars agree or disagree, and how works in your chosen field or discipline are related. One way to keep track of this is by using a Synthesis Matrix .

Skill #3: Critique

As you are writing your literature review, you will want to apply a critical eye to the literature you have evaluated and synthesized. Consider the strong arguments you will make contrasted with the potential gaps in previous research. The words that you choose to report your critiques of the literature will be non-neutral. For instance, using a word like “attempted” suggests that a researcher tried something but was not successful. For example:

There were some attempts by Smith (2012) and Jones (2013) to integrate a new methodology in this process.

On the other hand, using a word like “proved” or a phrase like “produced results” evokes a more positive argument. For example:

The new methodologies employed by Blake (2014) produced results that provided further evidence of X.

In your critique, you can point out where you believe there is room for more coverage in a topic, or further exploration in in a sub-topic.

Need more help?

If you are looking for more detailed guidance about writing your dissertation, please contact the folks in the Georgia Tech Communication Center .

- << Previous: Step 1: Literature search

- Next: Step 3: Writing the review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 11:21 AM

- URL: https://libguides.library.gatech.edu/litreview

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

- 3 minute read

- 44.4K views

Table of Contents

As a researcher, you may be required to conduct a literature review. But what kind of review do you need to complete? Is it a systematic literature review or a standard literature review? In this article, we’ll outline the purpose of a systematic literature review, the difference between literature review and systematic review, and other important aspects of systematic literature reviews.

What is a Systematic Literature Review?

The purpose of systematic literature reviews is simple. Essentially, it is to provide a high-level of a particular research question. This question, in and of itself, is highly focused to match the review of the literature related to the topic at hand. For example, a focused question related to medical or clinical outcomes.

The components of a systematic literature review are quite different from the standard literature review research theses that most of us are used to (more on this below). And because of the specificity of the research question, typically a systematic literature review involves more than one primary author. There’s more work related to a systematic literature review, so it makes sense to divide the work among two or three (or even more) researchers.

Your systematic literature review will follow very clear and defined protocols that are decided on prior to any review. This involves extensive planning, and a deliberately designed search strategy that is in tune with the specific research question. Every aspect of a systematic literature review, including the research protocols, which databases are used, and dates of each search, must be transparent so that other researchers can be assured that the systematic literature review is comprehensive and focused.

Most systematic literature reviews originated in the world of medicine science. Now, they also include any evidence-based research questions. In addition to the focus and transparency of these types of reviews, additional aspects of a quality systematic literature review includes:

- Clear and concise review and summary

- Comprehensive coverage of the topic

- Accessibility and equality of the research reviewed

Systematic Review vs Literature Review

The difference between literature review and systematic review comes back to the initial research question. Whereas the systematic review is very specific and focused, the standard literature review is much more general. The components of a literature review, for example, are similar to any other research paper. That is, it includes an introduction, description of the methods used, a discussion and conclusion, as well as a reference list or bibliography.

A systematic review, however, includes entirely different components that reflect the specificity of its research question, and the requirement for transparency and inclusion. For instance, the systematic review will include:

- Eligibility criteria for included research

- A description of the systematic research search strategy

- An assessment of the validity of reviewed research

- Interpretations of the results of research included in the review

As you can see, contrary to the general overview or summary of a topic, the systematic literature review includes much more detail and work to compile than a standard literature review. Indeed, it can take years to conduct and write a systematic literature review. But the information that practitioners and other researchers can glean from a systematic literature review is, by its very nature, exceptionally valuable.

This is not to diminish the value of the standard literature review. The importance of literature reviews in research writing is discussed in this article . It’s just that the two types of research reviews answer different questions, and, therefore, have different purposes and roles in the world of research and evidence-based writing.

Systematic Literature Review vs Meta Analysis

It would be understandable to think that a systematic literature review is similar to a meta analysis. But, whereas a systematic review can include several research studies to answer a specific question, typically a meta analysis includes a comparison of different studies to suss out any inconsistencies or discrepancies. For more about this topic, check out Systematic Review VS Meta-Analysis article.

Language Editing Plus

With Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus services , you can relax with our complete language review of your systematic literature review or literature review, or any other type of manuscript or scientific presentation. Our editors are PhD or PhD candidates, who are native-English speakers. Language Editing Plus includes checking the logic and flow of your manuscript, reference checks, formatting in accordance to your chosen journal and even a custom cover letter. Our most comprehensive editing package, Language Editing Plus also includes any English-editing needs for up to 180 days.

- Publication Recognition

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

- Manuscript Preparation

What is and How to Write a Good Hypothesis in Research?

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Reviewing Research: Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, Systematic Reviews

- Differentiating the Three Review Types

Reviewing Research: Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, Systematic Reviews: Differentiating the Three Review Types

- Framework, Protocol, and Writing Steps

- Working with Keywords/Subject Headings

- Citing Research

The Differences in the Review Types

Grant, M.J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. H ealth Information & Libraries Journal , 26: 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x The objective of this study is to provide descriptive insight into the most common types of reviews, with illustrative examples from health and health information domains.

- What Type of Review is Right for you (Cornell University)

Literature Reviews

Literature Review: it is a product and a process.

As a product , it is a carefully written examination, interpretation, evaluation, and synthesis of the published literature related to your topic. It focuses on what is known about your topic and what methodologies, models, theories, and concepts have been applied to it by others.

The process is what is involved in conducting a review of the literature.

- It is ongoing

- It is iterative (repetitive)

- It involves searching for and finding relevant literature.

- It includes keeping track of your references and preparing and formatting them for the bibliography of your thesis

- Literature Reviews (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews are a " preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature . Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research)." Grant and Booth (2009).

Scoping reviews are not mapping reviews: Scoping reviews are more topic based and mapping reviews are more question based.

- examining emerging evidence when specific questions are unclear - clarify definitions and conceptual boundaries

- identify and map the available evidence

- a scoping review is done prior to a systematic review

- to summarize and disseminate research findings in the research literature

- identify gaps with the intention of resolution by future publications

- Scoping review timeframe and limitations (Touro College of Pharmacy

Systematic Reviews

Many evidence-based disciplines use ‘systematic reviews," this type of review is a specific methodology that aims to comprehensively identify all relevant studies on a specific topic, and to select appropriate studies based on explicit criteria . ( https://cebma.org/faq/what-is-a-systematic-review/ )

- clearly defined search criteria

- an explicit reproducible methodology

- a systematic search of the literature with the defined criteria met

- assesses validity of the findings - no risk of bias

- a comprehensive report on the findings, apparent transparency in the results

- Better evidence for a better world Browsable collection of systematic reviews

- Systematic Reviews in the Health Sciences by Molly Maloney Last Updated Apr 23, 2024 515 views this year

- Next: Framework, Protocol, and Writing Steps >>

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

Analyze results.

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Librarian Support

Analysis should lead to insight. This is how you will contribute to the field.

- Analysis requires that you have an approach or a point of view to evaluate the material you found.

- Are there gaps in the literature?

- Where has significant research taken place, and who has done it?

- Is there consensus or debate on this topic?

- Which methodological approaches work best?

Analysis is the part of the literature review process where you justify why your research is needed, how others have not addressed it, and/or how your research advances the field.

Tips for Writing a Literature Review

Though this video is titled "Tips for Writing a Literature Review," the ideas expressed relate to being focused on the research topic and building a strong case, which is also part of the analysis phase.

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

About Systematic Reviews

Understanding the Differences Between a Systematic Review vs Literature Review

Automate every stage of your literature review to produce evidence-based research faster and more accurately.

Let’s look at these differences in further detail.

Goal of the Review

The objective of a literature review is to provide context or background information about a topic of interest. Hence the methodology is less comprehensive and not exhaustive. The aim is to provide an overview of a subject as an introduction to a paper or report. This overview is obtained firstly through evaluation of existing research, theories, and evidence, and secondly through individual critical evaluation and discussion of this content.

A systematic review attempts to answer specific clinical questions (for example, the effectiveness of a drug in treating an illness). Answering such questions comes with a responsibility to be comprehensive and accurate. Failure to do so could have life-threatening consequences. The need to be precise then calls for a systematic approach. The aim of a systematic review is to establish authoritative findings from an account of existing evidence using objective, thorough, reliable, and reproducible research approaches, and frameworks.

Level of Planning Required

The methodology involved in a literature review is less complicated and requires a lower degree of planning. For a systematic review, the planning is extensive and requires defining robust pre-specified protocols. It first starts with formulating the research question and scope of the research. The PICO’s approach (population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes) is used in designing the research question. Planning also involves establishing strict eligibility criteria for inclusion and exclusion of the primary resources to be included in the study. Every stage of the systematic review methodology is pre-specified to the last detail, even before starting the review process. It is recommended to register the protocol of your systematic review to avoid duplication. Journal publishers now look for registration in order to ensure the reviews meet predefined criteria for conducting a systematic review [1].

Search Strategy for Sourcing Primary Resources

Learn more about distillersr.

(Article continues below)

Quality Assessment of the Collected Resources

A rigorous appraisal of collected resources for the quality and relevance of the data they provide is a crucial part of the systematic review methodology. A systematic review usually employs a dual independent review process, which involves two reviewers evaluating the collected resources based on pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The idea is to limit bias in selecting the primary studies. Such a strict review system is generally not a part of a literature review.

Presentation of Results

Most literature reviews present their findings in narrative or discussion form. These are textual summaries of the results used to critique or analyze a body of literature about a topic serving as an introduction. Due to this reason, literature reviews are sometimes also called narrative reviews. To know more about the differences between narrative reviews and systematic reviews , click here.

A systematic review requires a higher level of rigor, transparency, and often peer-review. The results of a systematic review can be interpreted as numeric effect estimates using statistical methods or as a textual summary of all the evidence collected. Meta-analysis is employed to provide the necessary statistical support to evidence outcomes. They are usually conducted to examine the evidence present on a condition and treatment. The aims of a meta-analysis are to determine whether an effect exists, whether the effect is positive or negative, and establish a conclusive estimate of the effect [2].

Using statistical methods in generating the review results increases confidence in the review. Results of a systematic review are then used by clinicians to prescribe treatment or for pharmacovigilance purposes. The results of the review can also be presented as a qualitative assessment when the end goal is issuing recommendations or guidelines.

Risk of Bias

Literature reviews are mostly used by authors to provide background information with the intended purpose of introducing their own research later. Since the search for included primary resources is also less exhaustive, it is more prone to bias.

One of the main objectives for conducting a systematic review is to reduce bias in the evidence outcome. Extensive planning, strict eligibility criteria for inclusion and exclusion, and a statistical approach for computing the result reduce the risk of bias.

Intervention studies consider risk of bias as the “likelihood of inaccuracy in the estimate of causal effect in that study.” In systematic reviews, assessing the risk of bias is critical in providing accurate assessments of overall intervention effect [3].

With numerous review methods available for analyzing, synthesizing, and presenting existing scientific evidence, it is important for researchers to understand the differences between the review methods. Choosing the right method for a review is crucial in achieving the objectives of the research.

[1] “Systematic Review Protocols and Protocol Registries | NIH Library,” www.nihlibrary.nih.gov . https://www.nihlibrary.nih.gov/services/systematic-review-service/systematic-review-protocols-and-protocol-registries

[2] A. B. Haidich, “Meta-analysis in medical research,” Hippokratia , vol. 14, no. Suppl 1, pp. 29–37, Dec. 2010, [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3049418/#:~:text=Meta%2Danalyses%20are%20conducted%20to

3 Reasons to Connect

- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Systematic reviews vs meta-analysis: what’s the difference?

Posted on 24th July 2023 by Verónica Tanco Tellechea

You may hear the terms ‘systematic review’ and ‘meta-analysis being used interchangeably’. Although they are related, they are distinctly different. Learn more in this blog for beginners.

What is a systematic review?

According to Cochrane (1), a systematic review attempts to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence to answer a specific research question. Thus, a systematic review is where you might find the most relevant, adequate, and current information regarding a specific topic. In the levels of evidence pyramid , systematic reviews are only surpassed by meta-analyses.

To conduct a systematic review, you will need, among other things:

- A specific research question, usually in the form of a PICO question.

- Pre-specified eligibility criteria, to decide which articles will be included or discarded from the review.

- To follow a systematic method that will minimize bias.

You can find protocols that will guide you from both Cochrane and the Equator Network , among other places, and if you are a beginner to the topic then have a read of an overview about systematic reviews.

What is a meta-analysis?

A meta-analysis is a quantitative, epidemiological study design used to systematically assess the results of previous research (2) . Usually, they are based on randomized controlled trials, though not always. This means that a meta-analysis is a mathematical tool that allows researchers to mathematically combine outcomes from multiple studies.

When can a meta-analysis be implemented?

There is always the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis, yet, for it to throw the best possible results it should be performed when the studies included in the systematic review are of good quality, similar designs, and have similar outcome measures.

Why are meta-analyses important?

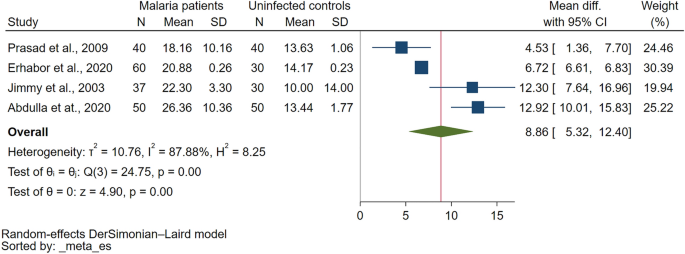

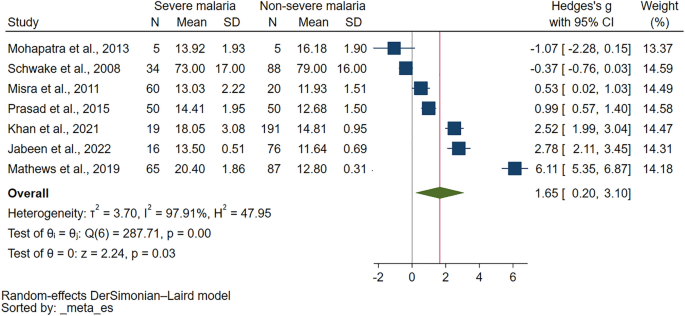

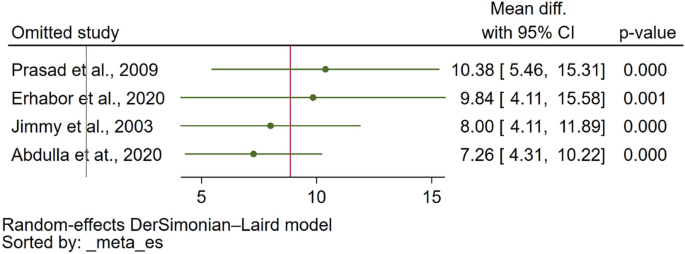

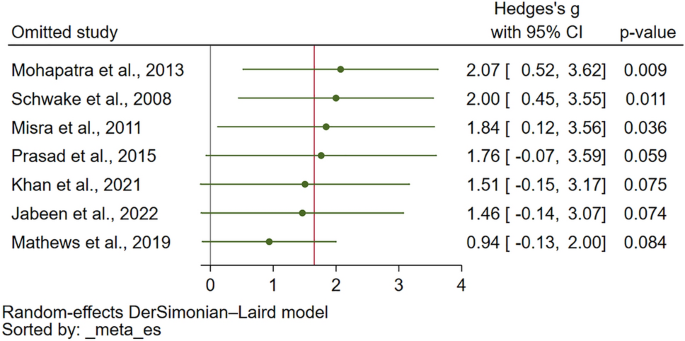

Outcomes from a meta-analysis may provide more precise information regarding the estimate of the effect of what is being studied because it merges outcomes from multiple studies. In a meta-analysis, data from various trials are combined and generate an average result (1), which is portrayed in a forest plot diagram. Moreover, meta-analysis also include a funnel plot diagram to visually detect publication bias.

Conclusions

A systematic review is an article that synthesizes available evidence on a certain topic utilizing a specific research question, pre-specified eligibility criteria for including articles, and a systematic method for its production. Whereas a meta-analysis is a quantitative, epidemiological study design used to assess the results of articles included in a systematic-review.

Remember: All meta-analyses involve a systematic review, but not all systematic reviews involve a meta-analysis.

If you would like some further reading on this topic, we suggest the following:

The systematic review – a S4BE blog article

Meta-analysis: what, why, and how – a S4BE blog article

The difference between a systematic review and a meta-analysis – a blog article via Covidence

Systematic review vs meta-analysis: what’s the difference? A 5-minute video from Research Masterminds:

- About Cochrane reviews [Internet]. Cochranelibrary.com. [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/about/about-cochrane-reviews

- Haidich AB. Meta-analysis in medical research. Hippokratia. 2010;14(Suppl 1):29–37.

Verónica Tanco Tellechea

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

How to read a funnel plot

This blog introduces you to funnel plots, guiding you through how to read them and what may cause them to look asymmetrical.

Heterogeneity in meta-analysis

When you bring studies together in a meta-analysis, one of the things you need to consider is the variability in your studies – this is called heterogeneity. This blog presents the three types of heterogeneity, considers the different types of outcome data, and delves a little more into dealing with the variations.

Natural killer cells in glioblastoma therapy

As seen in a previous blog from Davide, modern neuroscience often interfaces with other medical specialities. In this blog, he provides a summary of new evidence about the potential of a therapeutic strategy born at the crossroad between neurology, immunology and oncology.

Literature Review vs Systematic Review

- Literature Review vs. Systematic Review

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Databases and Articles

- Specific Journal or Article

Subject Guide

Definitions

It’s common to confuse systematic and literature reviews because both are used to provide a summary of the existent literature or research on a specific topic. Regardless of this commonality, both types of review vary significantly. The following table provides a detailed explanation as well as the differences between systematic and literature reviews.

Kysh, Lynn (2013): Difference between a systematic review and a literature review. [figshare]. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.766364

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Primary vs. Secondary Sources >>

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 10:19 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sjsu.edu/LitRevVSSysRev

Guide to Thematic Analysis

- Abductive Thematic Analysis

- Collaborative Thematic Analysis

- Deductive Thematic Analysis

- How to Do Thematic Analysis

- Inductive Thematic Analysis

- Reflexive Thematic Analysis

- Advantages of Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Analysis for Case Studies

- Thematic Coding

- Disadvantages of Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Analysis in Educational Research

- Thematic Analysis Examples

- Thematic Analysis for Focus Groups

- Thematic Analysis vs. Grounded Theory

- What is Thematic Analysis?

- Increasing Rigor in Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Analysis for Interviews

- Introduction

What is a thematic literature review?

Advantages of a thematic literature review, structuring and writing a thematic literature review.

- Thematic Analysis in Mixed Methods Approach

- Thematic Analysis in Observations

- Peer Review in Thematic Analysis

- How to Present Thematic Analysis Results

- Thematic Analysis in Psychology

- Thematic Analysis of Secondary Data

- Thematic Analysis in Social Work

- Thematic Analysis Software

- Thematic Analysis in Surveys

- Thematic Analysis in UX Research

- Thematic vs. Content Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Discourse Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Framework Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Narrative Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Phenomenology

A thematic literature review serves as a critical tool for synthesizing research findings within a specific subject area. By categorizing existing literature into themes, this method offers a structured approach to identify and analyze patterns and trends across studies. The primary goal is to provide a clear and concise overview that aids scholars and practitioners in understanding the key discussions and developments within a field. Unlike traditional literature reviews , which may adopt a chronological approach or focus on individual studies, a thematic literature review emphasizes the aggregation of findings through key themes and thematic connections. This introduction sets the stage for a detailed examination of what constitutes a thematic literature review, its benefits, and guidance on effectively structuring and writing one.

A thematic literature review methodically organizes and examines a body of literature by identifying, analyzing, and reporting themes found within texts such as journal articles, conference proceedings, dissertations, and other forms of academic writing. While a particular journal article may offer some specific insight, a synthesis of knowledge through a literature review can provide a comprehensive overview of theories across relevant sources in a particular field.

Unlike other review types that might organize literature chronologically or by methodology , a thematic review focuses on recurring themes or patterns across a collection of works. This approach enables researchers to draw together previous research to synthesize findings from different research contexts and methodologies, highlighting the overarching trends and insights within a field.

At its core, a thematic approach to a literature review research project involves several key steps. Initially, it requires the comprehensive collection of relevant literature that aligns with the review's research question or objectives. Following this, the process entails a meticulous analysis of the texts to identify common themes that emerge across the studies. These themes are not pre-defined but are discovered through a careful reading and synthesis of the literature.

The thematic analysis process is iterative, often involving the refinement of themes as the review progresses. It allows for the integration of a broad range of literature, facilitating a multidimensional understanding of the research topic. By organizing literature thematically, the review illuminates how various studies contribute to each theme, providing insights into the depth and breadth of research in the area.

A thematic literature review thus serves as a foundational element in research, offering a nuanced and comprehensive perspective on a topic. It not only aids in identifying gaps in the existing literature but also guides future research directions by underscoring areas that warrant further investigation. Ultimately, a thematic literature review empowers researchers to construct a coherent narrative that weaves together disparate studies into a unified analysis.

Organize your literature search with ATLAS.ti

Collect and categorize documents to identify gaps and key findings with ATLAS.ti. Download a free trial.

Conducting a literature review thematically provides a comprehensive and nuanced synthesis of research findings, distinguishing it from other types of literature reviews. Its structured approach not only facilitates a deeper understanding of the subject area but also enhances the clarity and relevance of the review. Here are three significant advantages of employing a thematic analysis in literature reviews.

Enhanced understanding of the research field

Thematic literature reviews allow for a detailed exploration of the research landscape, presenting themes that capture the essence of the subject area. By identifying and analyzing these themes, reviewers can construct a narrative that reflects the complexity and multifaceted nature of the field.

This process aids in uncovering underlying patterns and relationships, offering a more profound and insightful examination of the literature. As a result, readers gain an enriched understanding of the key concepts, debates, and evolutionary trajectories within the research area.

Identification of research gaps and trends

One of the pivotal benefits of a thematic literature review is its ability to highlight gaps in the existing body of research. By systematically organizing the literature into themes, reviewers can pinpoint areas that are under-explored or warrant further investigation.

Additionally, this method can reveal emerging trends and shifts in research focus, guiding scholars toward promising areas for future study. The thematic structure thus serves as a roadmap, directing researchers toward uncharted territories and new research questions .

Facilitates comparative analysis and integration of findings

A thematic literature review excels in synthesizing findings from diverse studies, enabling a coherent and integrated overview. By concentrating on themes rather than individual studies, the review can draw comparisons and contrasts across different research contexts and methodologies . This comparative analysis enriches the review, offering a panoramic view of the field that acknowledges both consensus and divergence among researchers.

Moreover, the thematic framework supports the integration of findings, presenting a unified and comprehensive portrayal of the research area. Such integration is invaluable for scholars seeking to navigate the extensive body of literature and extract pertinent insights relevant to their own research questions or objectives.

The process of structuring and writing a thematic literature review is pivotal in presenting research in a clear, coherent, and impactful manner. This review type necessitates a methodical approach to not only unearth and categorize key themes but also to articulate them in a manner that is both accessible and informative to the reader. The following sections outline essential stages in the thematic analysis process for literature reviews , offering a structured pathway from initial planning to the final presentation of findings.

Identifying and categorizing themes

The initial phase in a thematic literature review is the identification of themes within the collected body of literature. This involves a detailed examination of texts to discern patterns, concepts, and ideas that recur across the research landscape. Effective identification hinges on a thorough and nuanced reading of the literature, where the reviewer actively engages with the content to extract and note significant thematic elements. Once identified, these themes must be meticulously categorized, often requiring the reviewer to discern between overarching themes and more nuanced sub-themes, ensuring a logical and hierarchical organization of the review content.

Analyzing and synthesizing themes

After categorizing the themes, the next step involves a deeper analysis and synthesis of the identified themes. This stage is critical for understanding the relationships between themes and for interpreting the broader implications of the thematic findings. Analysis may reveal how themes evolve over time, differ across methodologies or contexts, or converge to highlight predominant trends in the research area. Synthesis involves integrating insights from various studies to construct a comprehensive narrative that encapsulates the thematic essence of the literature, offering new interpretations or revealing gaps in existing research.

Presenting and discussing findings

The final stage of the thematic literature review is the discussion of the thematic findings in a research paper or presentation. This entails not only a descriptive account of identified themes but also a critical examination of their significance within the research field. Each theme should be discussed in detail, elucidating its relevance, the extent of research support, and its implications for future studies. The review should culminate in a coherent and compelling narrative that not only summarizes the key thematic findings but also situates them within the broader research context, offering valuable insights and directions for future inquiry.

Gain a comprehensive understanding of your data with ATLAS.ti

Analyze qualitative data with specific themes that offer insights. See how with a free trial.

Home » Education » Difference Between Literature Review and Systematic Review

Difference Between Literature Review and Systematic Review

Main difference – literature review vs systematic review.

Literature review and systematic review are two scholarly texts that help to introduce new knowledge to various fields. A literature review, which reviews the existing research and information on a selected study area, is a crucial element of a research study. A systematic review is also a type of a literature review. The main difference between literature review and systematic review is their focus on the research question ; a systematic review is focused on a specific research question whereas a literature review is not.

This article highlights,

1. What is a Literature Review? – Definition, Features, Characteristics

2. What is a Systematic Review? – Definition, Features, Characteristics

What is a Literature Review

A literature review is an indispensable element of a research study. This is where the researcher shows his knowledge on the subject area he or she is researching on. A literature review is a discussion on the already existing material in the subject area. Thus, this will require a collection of published (in print or online) work concerning the selected research area. In simple terms, a literature is a review of the literature in the related subject area.

A good literature review is a critical discussion, displaying the writer’s knowledge on relevant theories and approaches and awareness of contrasting arguments. A literature review should have the following features (Caulley, 1992)

- Compare and contrast different researchers’ views

- Identify areas in which researchers are in disagreement

- Group researchers who have similar conclusions

- Criticize the methodology

- Highlight exemplary studies

- Highlight gaps in research

- Indicate the connection between your study and previous studies

- Indicate how your study will contribute to the literature in general

- Conclude by summarizing what the literature indicates

The structure of a literature review is similar to that of an article or essay, unlike an annotated bibliography . The information that is collected is integrated into paragraphs based on their relevance. Literature reviews help researchers to evaluate the existing literature, to identify a gap in the research area, to place their study in the existing research and identify future research.

What is a Systematic Review

A systematic review is a type of systematic review that is focused on a particular research question . The main purpose of this type of research is to identify, review, and summarize the best available research on a specific research question. Systematic reviews are used mainly because the review of existing studies is often more convenient than conducting a new study. These are mostly used in the health and medical field, but they are not rare in fields such as social sciences and environmental science. Given below are the main stages of a systematic review:

- Defining the research question and identifying an objective method

- Searching for relevant data that from existing research studies that meet certain criteria (research studies must be reliable and valid).

- Extracting data from the selected studies (data such as the participants, methods, outcomes, etc.

- Assessing the quality of information

- Analyzing and combining all the data which would give an overall result.

Literature Review is a critical evaluation of the existing published work in a selected research area.

Systematic Review is a type of literature review that is focused on a particular research question.

Literature Review aims to review the existing literature, identify the research gap, place the research study in relation to other studies, to evaluate promising research methods, and to suggest further research.

Systematic Review aims to identify, review, and summarize the best available research on a specific research question.

Research Question

In Literature Review, a r esearch question is formed after writing the literature review and identifying the research gap.

In Systematic Review, a research question is formed at the beginning of the systematic review.

Research Study

Literature Review is an essential component of a research study and is done at the beginning of the study.

Systematic Review is not followed by a separate research study.

Caulley, D. N. “Writing a critical review of the literature.” La Trobe University: Bundoora (1992).

“Animated Storyboard: What Are Systematic Reviews?” . cccrg.cochrane.org . Cochrane Consumers and Communication . Retrieved 1 June 2016.

Image Courtesy: Pixabay

About the Author: Hasa

Hasanthi is a seasoned content writer and editor with over 8 years of experience. Armed with a BA degree in English and a knack for digital marketing, she explores her passions for literature, history, culture, and food through her engaging and informative writing.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

A link to reset your password has been sent to your email.

Back to login

We need additional information from you. Please complete your profile first before placing your order.

Thank you. payment completed., you will receive an email from us to confirm your registration, please click the link in the email to activate your account., there was error during payment, orcid profile found in public registry, download history, difference between a literature review and a critical review.

- Charlesworth Author Services

- 08 October, 2021

As you read research papers, you may notice that there are two very different kinds of review of prior studies. Sometimes, this section of a paper is called a literature review, and at other times, it is referred to as a critical review or a critical context . These differences may be more commonly seen across different fields. Although both these sections are about reviewing prior and existing studies, this article aims to clarify the differences between the two.

Literature review

A literature review is a summary of prior or existing studies that are related to your own research paper . A literature review can be a part of a research paper or can form a paper in itself . For the former, the literature review is designed as a basis upon which your own current study is designed and built. The latter forms a synthesis of prior studies and is a way to highlight future research agendas or a framework.

Writing a literature review

In a literature review, you should attempt to discuss the arguments and findings in prior studies and then work to build on these studies as you develop your own research. You can also highlight the connection between existing and prior literature to demonstrate how the current study you are presenting can advance your knowledge in the field .

When performing a literature review, you should aim to summarise your discussions using a specific aspect of the literature, such as by topic, time, methodology/ design and findings . By doing so, you should be able to establish an effective way to present the relevant literature and demonstrate the connection between prior studies and your research.

Do note that a literature review does not include a presentation or discussion of any results or findings – this should come at a later point in the paper or study. You should also not impose your subjective viewpoints or opinions on the literature you discuss.

Critical review

A critical review is also a popular way of reviewing prior and existing studies. It can cover and discuss the main ideas or arguments in a book or an article, or it can review a specific concept, theme, theoretical perspective or key construct found in the existing literature .

However, the key feature that distinguishes a critical review from a literature review is that the former is more than just a summary of different topics or methodologies. It offers more of a reflection and critique of the concept in question, and is engaged by authors to more clearly contextualise their own research within the existing literature and to present their opinions, perspectives and approaches .

Given that a critical review is not just a summary of prior literature, it is generally not considered acceptable to follow the same strategy as for a literature review. Instead, aim to organise and structure your critical review in a way that would enable you to discuss the key concepts, assert your perspectives and locate your arguments and research within the existing body of work.

Structuring a critical review

A critical review would generally begin with an introduction to the concepts you would like to discuss. Depending on how broad the topics are, this can simply be a brief overview or it could set up a more complex framework. The discussion that follows through the rest of the review will then address and discuss your chosen themes or topics in more depth.

Writing a critical review

The discussion within a critical review will not only present and summarise themes but also critically engage with the varying arguments, writings and perspectives within those themes. One important thing to note is that, similar to a literature review , you should keep your personal opinions, likes and dislikes out of a review. Whether you personally agree with a study or argument – and whether you like it or not – is immaterial. Instead, you should focus upon the effectiveness and relevance of the arguments , considering such elements as the evidence provided, the interpretations and analysis of the data, whether or not a study may be biased in any way, what further questions or problems it raises or what outstanding gaps and issues need to be addressed.

In conclusion

Although a review of previous and existing literature can be performed and presented in different ways, in essence, any literature or critical review requires a solid understanding of the most prominent work in the field as it relates to your own study. Such an understanding is crucial and significant for you to build upon and synthesise the existing knowledge, and to create and contribute new knowledge to advance the field .

Read previous (fourth) in series: How to refer to other studies or literature in the different sections of a research paper

Maximise your publication success with Charlesworth Author Services .

Charlesworth Author Services, a trusted brand supporting the world’s leading academic publishers, institutions and authors since 1928.

To know more about our services, visit: Our Services

Share with your colleagues

Related articles.

Conducting a Literature Review

Charlesworth Author Services 10/03/2021 00:00:00

Important factors to consider as you Start to Plan your Literature Review

Charlesworth Author Services 06/10/2021 00:00:00

How to Structure and Write your Literature Review

Charlesworth Author Services 07/10/2021 00:00:00

Related webinars

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication- Module 3: Understand the structure of an academic paper

Charlesworth Author Services 04/03/2021 00:00:00

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 5: Conduct a Literature Review

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 7: Write a strong theoretical framework section

Charlesworth Author Services 05/03/2021 00:00:00

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 11: Know when your article is ready for submission

Literature search.

Why and How to do a literature search

Charlesworth Author Services 17/08/2020 00:00:00

Best tips to do a PubMed search

Charlesworth Author Services 26/08/2021 00:00:00

Best tips to do a Scopus search

Understanding the influence of different proxy perspectives in explaining the difference between self-rated and proxy-rated quality of life in people living with dementia: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis

- Open access

- Published: 24 April 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lidia Engel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7959-3149 1 ,

- Valeriia Sokolova 1 ,

- Ekaterina Bogatyreva 2 &

- Anna Leuenberger 2

217 Accesses

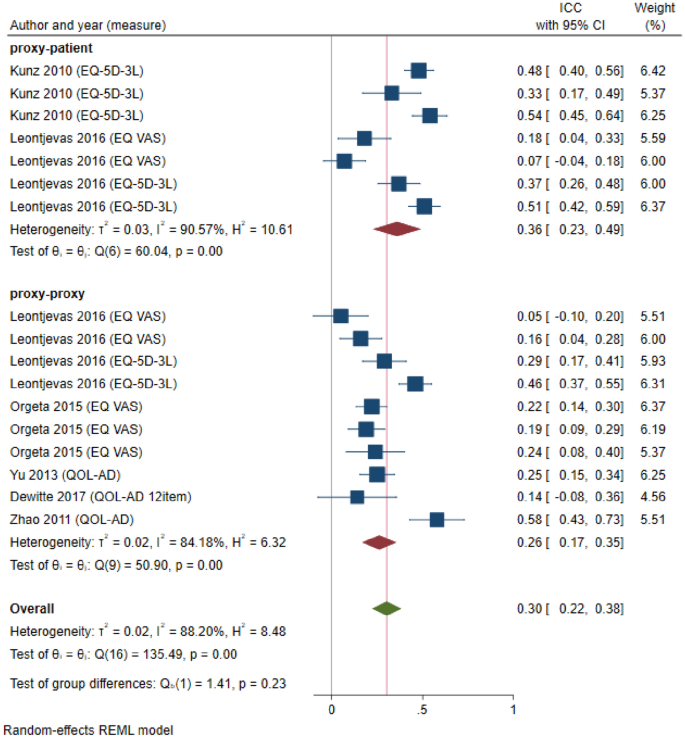

Explore all metrics

Proxy assessment can be elicited via the proxy-patient perspective (i.e., asking proxies to assess the patient’s quality of life (QoL) as they think the patient would respond) or proxy-proxy perspective (i.e., asking proxies to provide their own perspective on the patient’s QoL). This review aimed to identify the role of the proxy perspective in explaining the differences between self-rated and proxy-rated QoL in people living with dementia.

A systematic literate review was conducted by sourcing articles from a previously published review, supplemented by an update of the review in four bibliographic databases. Peer-reviewed studies that reported both self-reported and proxy-reported mean QoL estimates using the same standardized QoL instrument, published in English, and focused on the QoL of people with dementia were included. A meta-analysis was conducted to synthesize the mean differences between self- and proxy-report across different proxy perspectives.

The review included 96 articles from which 635 observations were extracted. Most observations extracted used the proxy-proxy perspective (79%) compared with the proxy-patient perspective (10%); with 11% of the studies not stating the perspective. The QOL-AD was the most commonly used measure, followed by the EQ-5D and DEMQOL. The standardized mean difference (SMD) between the self- and proxy-report was lower for the proxy-patient perspective (SMD: 0.250; 95% CI 0.116; 0.384) compared to the proxy-proxy perspective (SMD: 0.532; 95% CI 0.456; 0.609).

Different proxy perspectives affect the ratings of QoL, whereby adopting a proxy-proxy QoL perspective has a higher inter-rater gap in comparison with the proxy-patient perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring self-report and proxy-report quality-of-life measures for people living with dementia in care homes

Convergent validity of EQ-5D with core outcomes in dementia: a systematic review

Proxy reporting of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: a psychometric solution

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Quality of life (QoL) has become an important outcome for research and practice but obtaining reliable and valid estimates remains a challenge in people living with dementia [ 1 ]. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria [ 2 ], dementia, termed as Major Neurocognitive Disorder (MND), involves a significant decline in at least one cognitive domain (executive function, complex attention, language, learning, memory, perceptual-motor, or social cognition), where the decline represents a change from a patient's prior level of cognitive ability, is persistent and progressive over time, is not associated exclusively with an episode of delirium, and reduces a person’s ability to perform everyday activities. Since dementia is one of the most pressing challenges for healthcare systems nowadays [ 3 ], it is critical to study its impact on QoL. The World Health Organization defines the concept of QoL as “individuals' perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” [ 4 ]. It is a broad ranging concept incorporating in a complex way the persons' physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs, and their relationships to salient features of the environment.

Although there is evidence that people with mild to moderate dementia can reliably rate their own QoL [ 5 ], as the disease progresses, there is typically a decline in memory, attention, judgment, insight, and communication that may compromise self-reporting of QoL [ 6 ]. Additionally, behavioral symptoms, such as agitation, and affective symptoms, such as depression, may present another challenge in obtaining self-reported QoL ratings due to emotional shifts and unwillingness to complete the assessment [ 7 ]. Although QoL is subjective and should ideally be assessed from an individual’s own perspective [ 8 ], the decline in cognitive function emphasizes the need for proxy-reporting by family members, health professionals, or care staff who are asked to report on behalf of the person with dementia. However, proxy-reports are not substitutable for self-reports from people with dementia, as they offer supplementary insights, reflecting the perceptions and viewpoints of people surrounding the person with dementia [ 9 ].

Previous research has consistently highlighted a disagreement between self-rated and proxy-rated QoL in people living with dementia, with proxies generally providing lower ratings (indicating poorer QoL) compared with person’s own ratings [ 8 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Impairment in cognition associated with greater dementia severity has been found to be associated with larger difference between self-rating and proxy-rating obtained from family caregivers, as it becomes increasingly difficult for severely cognitively impaired individuals to respond to questions that require contemplation, introspection, and sustained attention [ 13 , 14 ]. Moreover, non-cognitive factors, such as awareness of disease and depressive symptoms play an important role when comparing QoL ratings between individuals with dementia and their proxies [ 15 ]. Qualitative evidence has also shown that people with dementia tend to compare themselves with their peers, whereas carers make comparisons with how the person used to be in the past [ 9 ]. The disagreement between self-reported QoL and carer proxy-rated QoL could be modulated by some personal, cognitive or relational factors, for example, the type of relationship or the frequency of contact maintained, person’s cognitive status, carer’s own feeling about dementia, carer’s mood, and perceived burden of caregiving [ 14 , 16 ]. Disagreement may also arise from the person with dementia’s problems to communicate symptoms, and proxies’ inability to recognize certain symptoms, like pain [ 17 ], or be impacted by the amount of time spent with the person with dementia [ 18 ]. This may also prevent proxies to rate accurately certain domains of QoL, with previous evidence showing higher level of agreement for observable domains, such as mobility, compared with less observable domains like emotional wellbeing [ 8 ]. Finally, agreement also depends on the type of proxy (i.e., informal/family carers or professional staff) and the nature of their relationship, for instance, proxy QoL scores provided by formal carers tend to be higher (reflecting better QoL) compared to the scores supplied by family members [ 19 , 20 ]. Staff members might associate residents’ QoL with the quality of care delivered or the stage of their cognitive impairment, whereas relatives often focus on comparison with the person’s QoL when they were younger, lived in their own home and did not have dementia [ 20 ].

What has been not been fully examined to date is the role of different proxy perspectives employed in QoL questionnaires in explaining disagreement between self-rated and proxy-rated scores in people with dementia. Pickard et al. (2005) have proposed a conceptual framework for proxy assessments that distinguish between the proxy-patient perspective (i.e., asking proxies to assess the patient’s QoL as they think the patient would respond) or proxy-proxy perspective (i.e., asking proxies to provide their own perspective on the patient’s QoL) [ 21 ]. In this context, the intra-proxy gap describes the differences between proxy-patient and proxy-proxy perspective, whereas the inter-rater gap is the difference between self-report and proxy-report [ 21 ].

Existing generic and dementia-specific QoL instruments specify the perspective explicitly in their instructions or imply the perspective indirectly in their wording. For example, the instructions of the Dementia Quality of Life Measure (DEMQOL) asks proxies to give the answer they think their relative would give (i.e., proxy-patient perspective) [ 22 ], whereas the family version of the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QOL-AD) instructs the proxies to rate their relative’s current situation as they (the proxy) see it (i.e., proxy-proxy perspective) [ 7 ]. Some instruments, like the EQ-5D measures, have two proxy versions for each respective perspective [ 23 , 24 ]. The Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit (ASCOT) proxy version, on the other hand, asks proxies to complete the questions from both perspectives, from their own opinion and how they think the person would answer [ 25 ].

QoL scores generated using different perspectives are expected to differ, with qualitative evidence showing that carers rate the person with dementia’s QoL lower (worse) when instructed to comment from their own perspective than from the perspective of the person with dementia [ 26 ]. However, to our knowledge, no previous review has fully synthesized existing evidence in this area. Therefore, we aimed to undertake a systematic literature review to examine the role of different proxy-assessment perspectives in explaining differences between self-rated and proxy-rated QoL in people living with dementia. The review was conducted under the hypothesis that the difference in QoL estimates will be larger when adopting the proxy-proxy perspective compared with proxy-patient perspective.

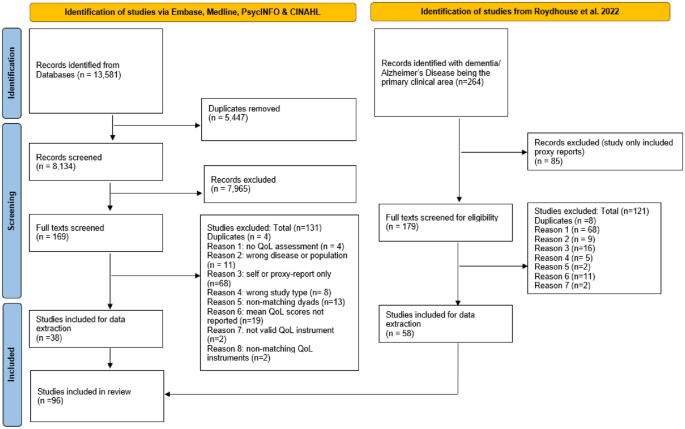

The review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42022333542) and followed the Preferred Reporting Items System for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (see Appendix 1 ) [ 27 ].

Search strategy

This review used two approaches to obtain literature. First, primary articles from an existing review by Roydhouse et al. were retrieved [ 28 ]. The review included studies published from inception to February 2018 that compared self- and proxy-reports. Studies that focused explicitly on Alzheimer’s Disease or dementia were retrieved for the current review. Two reviewers conducted a full-text review to assess whether the eligibility criteria listed below for the respective study were met. An update of the Roydhouse et al. review was undertaken to capture more recent studies. The search strategy by Roydhouse et al. was amended and covered studies published after January 1, 2018, and was limited to studies within the context of dementia. The original search was undertaken over a three-week period (17/11/2021–9/12/2021) and then updated on July 3, 2023. Peer-reviewed literature was sourced from MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases via EBSCOHost as well as EMBASE. Four main search term categories were used: (1) proxy terms (i.e., care*-report*), (2) QoL/ outcome terms (i.e., ‘quality of life’), (3) disease terms (i.e., ‘dementia’), and (4) pediatric terms (i.e., ‘pediatric*’) (for exclusion). Keywords were limited to appear in titles and abstracts only, and MeSH terms were included for all databases. A list of search strategy can be found in Appendix 2 . The first three search term categories were searched with AND, and the NOT function was used to exclude pediatric terms. A limiter was applied in all database searches to only include studies with human participants and articles published in English.

Selection criteria

Studies from all geographical locations were included in the review if they (1) were published in English in a peer-reviewed journal (conference abstracts, dissertations, a gray literature were excluded); (2) were primary studies (reviews were excluded); (3) clearly defined the disease of participants, which were limited to Alzheimer’s disease or dementia; (4) reported separate QoL scores for people with dementia (studies that included mixed populations had to report a separate QoL score for people with dementia to be considered); (5) were using a standardized and existing QoL instrument for assessment; and (6) provided a mean self-reported and proxy-reported QoL score for the same dyads sample (studies that reported means for non-matched samples were excluded) using the same QoL instrument.

Four reviewers (LE, VS, KB, AL) were grouped into two groups who independently screened the 179 full texts from the Roydhouse et. al (2022) study that included Alzheimer’s disease or dementia patients. If a discrepancy within the inclusion selection occurred, articles were discussed among all the reviewers until a consensus was reached. Studies identified from the database search were imported into EndNote [ 29 ]. Duplicates were removed through EndNote and then uploaded to Rayyan [ 30 ]. Each abstract was reviewed by two independent reviewers (any two from four reviewers). Disagreements regarding study inclusions were discussed between all reviewers until a consensus was reached. Full-text screening of each eligible article was completed by two independent reviewers (any two from four reviewers). Again, a discussion between all reviewers was used in case of disagreements.

Data extraction

A data extraction template was created in Microsoft Excel. The following information were extracted if available: country, study design, study sample, study setting, dementia type, disease severity, Mini-Mental Health State Exam (MMSE) score details, proxy type, perspective, living arrangements, QoL assessment measure/instrument, self-reported scores (mean, SD), proxy-reported scores (mean, SD), and agreement statistics. If a study reported the mean (SD) for the total score as well as for specific QoL domains of the measure, we extracted both. If studies reported multiple scores across different time points or subgroups, we extracted all scores. For interventional studies, scores from both the intervention group and the control group were recorded. In determining the proxy perspective, we relied on authors’ description in the article. If the perspective was not explicitly stated, we adopted the perspective of the instrument developers; where more perspectives were possible (e.g., in the case of the EQ-5D measures) and the perspective was not explicitly stated, it was categorized as ‘undefined.’ For agreement, we extracted the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), a reliability index that reflects both degree of correlation and agreement between measurements of continuous variables. While there are different forms of ICC based on the model (1-way random effects, 2-wy random effects, or 2-way fixed effects), the type (single rater/measurement or the mean k raters/measurements), and definition of relationship [ 31 ], this level of information was not extracted due to insufficient information provided in the original studies. Values for ICC range between 0 and 1, with values interpreted as poor (less than 0.5), moderate (0.5–0.75), good (0.75–0.9), and excellent (greater than 0.9) reliability between raters [ 31 ].

Data synthesis and analysis

Characteristics of studies were summarized descriptively. Self-reported and proxy-reported means and SD were extracted from the full texts and the mean difference was calculated (or extracted if available) for each pair. Studies that reported median values instead of mean values were converted using the approach outlined by Wan et al. (2014) [ 32 ]. Missing SDs (5 studies, 20 observations) were obtained from standard errors or confidence intervals reported following the Cochrane guidelines [ 33 ]. Missing SDs (6 studies, 29 observations) in studies that only presented the mean value without any additional summary statistics were imputed using the prognostic method [ 34 ]. Thereby, we predicted the missing SDs by calculating the average SDs of observed studies with full information by the respective measure and source (self-report versus proxy-report).