- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Exploring Critical Thinking vs. Systems Thinking

There are many differences between Critical Thinking vs Systems Thinking. Critical Thinking involves examining and challenging thoughts or ideas, while Systems Thinking focuses on examining the effects of actions or ideas on a system.

Chances are, most people have used Critical Thinking and Systems Thinking at some point in their life without knowing it. Both modes of thought help everyone, from students to politicians, solve problems, but they manage it differently.

What Is “Critical Thinking?”

Critical Thinking relies heavily on applying and studying logic and assessing illogical statements, beliefs, data, or information. It involves conceptualizing and evaluating information generated from observations, communication, and information that guides thoughts, ideas, and actions.

The school of thought behind Critical Thinking requires the application of the following skills:

- Develop and ask concise, objective questions challenging traditional modes of thought.

- Gather and investigate information to support and challenge thoughts and questions.

- Use empathy to think and relate to other modes of thoughts or beliefs.

- Focuses on generating clear communication to help solve problems.

- Critical Thinkers work to overcome their personal biases and beliefs to create a whole, clear picture of the world.

Critical Thinking requires examining the weaknesses and flaws in traditional Thinking or beliefs and looking for ways to improve personal thinking skills. In short, Critical Thinking requires the applier to look and think outside the box.

Steps To The Critical Thinking Process

- Analysis – Examining thoughts, ideas, or concepts to identify areas of improvement or containing flaws. This step identifies the topic or area of thought to apply Critical Thinking to.

- Evaluation – Evaluating the thoughts, ideas, or concepts’ quality and integrity. This step looks for why something is flawed, what the strengths of thought are, and identifies the areas that need the final stage of improvement.

- Improvement – The final step evaluates how and where modes of thought, beliefs, or ideas can improve. The last step allows the information gathered and interpreted in the first two steps to be used to create better quality thinking.

How Is Critical Thinking Applied In Life?

Critical Thinking applies to a variety of aspects of daily life. Some common examples include:

- Interviewing new job applicants without bias.

- Assessing large quantities of data to draw logical conclusions.

- Understanding and evaluating communication problems in a relationship.

- Identify bias and manipulation in political ads, commercials for brands, and news information.

- Examining why someone dislikes a person they have never met.

- Analyzing preferences towards certain brands or stores.

- Exploring personal feelings towards political beliefs or subjects in the news.

What Is “Systems Thinking?”

The world is not made up of random pieces and parts, at least not to a Systems Thinker. Instead of dissecting various aspects of life, data, or thinking as single entities, Systems Thinking views and analyzes relationships between things.

The idea of Systems Thinking aligns well with the imagery of a ripple effect or the butterfly effect; a single action spreads out to impact countless people, places, or things. Systems Thinking, however, only applies to actual systems. A system must fit the following criteria:

- A system has clear boundaries between the inside and outside of the system itself.

- A system connects and flows into and from the environment.

- A system takes in information, materials, and energy.

- A system gathers and stores nutrients or resources to generate work or results.

- A system produces waste , heat, and results of work.

- A system produces feedback that indicates how well the system is working.

Systems Thinking is dynamic. It looks at a system and identifies problems or issues throwing off what was inherently a functioning system. It requires looking at the Big Picture of an issue and finding the small ripples of input, output, and feedback that led to disarray in the system.

Steps To The Systems Thinking Process

- Identify – Systems Thinking starts like many scientific processes: finding a problem to fix.

- Hypothesize – After identifying the problem, thinkers generate a hypothesis to address the issue.

- Test and Evaluate – Once generated, thinkers apply the hypothesis via testing, data, and experimentation and evaluate the results.

- Implement Changes – After the hypothesis and data create an understanding and good quality information on how to fix the problem, the thinker applies the changes to the system. Steps 1-3 are repeated until the thinker can achieve step 4 with promising results.

How Is Systems Thinking Applied In Life?

The school of thought behind Systems Thinking applies to many aspects of life. Common situations where Systems Thinking works well include:

- Examining the effects of pollution on the Earth’s climate.

- The impact of a new medicine on the human body’s systems.

- The impact of poverty on education scores of students.

- The effect of the economy on the political beliefs of a population.

- Analyzing the effect of coffee on the human body.

- Examining how where someone shops impact their political views.

Critical Thinking vs. Systems Thinking (In A Nutshell)

Critical Thinking and Systems Thinking are not perpetually at odds. The two methodologies work well together to identify and evaluate problems. But they do have core differences that make them unique, separate ways of thinking and processing information.

Critical Thinking vs. Systems Thinking: The Main Differences

- Systems Thinking looks at the relationship between systems (e.g., the human body, economy, or environment) and their impact on each other. On the other hand, Critical Thinking examines thoughts, information, or beliefs to assess their quality and logic.

- Systems Thinking can only apply to a system , where Critical Thinking can apply to any concept, idea, belief, or information.

- Systems Thinkers look at the whole picture of a problem. Critical Thinkers examine parts or the whole of a thought, idea, or data to draw their conclusions.

Can Critical Thinking and Systems Thinking Work Together?

Yes, Critical Thinking and Systems Thinking can work together. Concise thinkers utilize Critical Thinking and Systems Thinking together when addressing many problems, often without knowing it!

Both modes of thought complement each other, with Critical Thinking providing logical support towards Systemic problems and Systemic Thinking providing “whole” pictures that pair well with Critical Thinking problems.

Systems Thinking, Critical Thinking, and Personal Resilience

The “Thinking” in Systems Thinking: How Can We Make It Easier to Master?

https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766

https://louisville.edu/ideastoaction/about/criticalthinking/what

You may also like

Systems Thinking for School Leaders: A Comprehensive Approach to Educational Management

Systems thinking is a powerful approach that school leaders can harness to navigate the complex landscape of education. With increasing challenges, such […]

Taking a systems thinking approach to problem solving

Systems thinking is an approach that considers a situation or problem holistically and as part of an overall system which is more […]

5 Ways to Apply Systems Thinking to Your Business Operations: A Strategic Guide

In today’s fast-paced business world, success depends on the ability to stay agile, resilient, and relevant. This is where systems thinking, an […]

Systems Thinking vs. Linear Thinking: Understanding the Key Differences

Systems Thinking and Linear Thinking are two approaches to problem-solving and decision-making that can significantly impact the effectiveness of a given solution. […]

What 'systems thinking' actually means - and why it matters for innovation today

Systems thinking helps us see the part of the iceberg that's beneath the water Image: Ezra Jeffrey

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Christian Tooley

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Innovation is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- Systems thinking can help us grasp the interconnectedness of our world.

- During the uncertainty of the pandemic, it can spur innovation.

We are currently living through VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) times.

As innovators, general professionals, key workers, citizens and humans, everything we do is ever more interdependent on each other. ‘No man is an island’ is a well-known phrase, yet in practice, how often do we understand the interconnectedness of everything around us? Enter systems thinking.

In some circles, there has been a lot of hype around taking an "ecosystems view" during this global pandemic, which frankly is not something new. Systems thinking has been an academic school of thought used in engineering, policy-making and more recently adapted by businesses to ensure their products and services are considering the ‘systems’ that they operate within.

Defining innovation

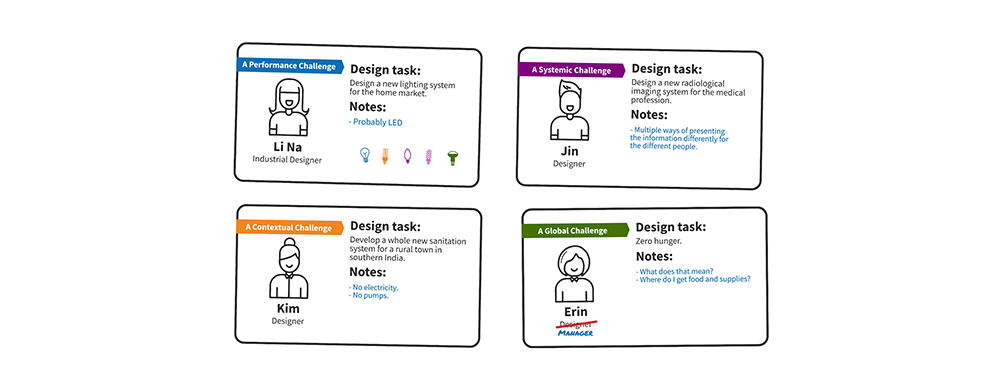

Every firm defines innovation in a different way. I enjoy using the four-quadrant model (see figure below) for simplicity: incremental innovation utilises your existing technology within your current market; architectural innovation is applying your technology in different markets; disruptive innovation involves applying new technology to current markets; and radical innovation displaces an entire business model.

During COVID-19, we are seeing a mixture of these. Many firms will start with incremental changes, adapting their products to a new period of uncertainty. With the right methodology and balance of internal and external capabilities, there is potential for radical and disruptive innovation that meets new needs, or fundamentally, creates new needs based on our current circumstances. Systems thinking is essential in untapping these types of innovation and ensuring they flourish long-term.

A dynamic duo

‘Systems thinking’ does not have one set toolkit but can vary across different disciplines, for example, in service design some may consider a ‘blueprint’ a high-level way to investigate one’s ‘systems of interest’. Crucially, this school of thought is even more powerful when combined with more common approaches, such as human-centered design (HCD).

The latter is bottom-up – looking in detail at a specific problem statement, empathising with its users and developing solutions to target them. Whereas the former is top-down – understanding the bigger picture, from policy and economics to partnerships and revenue streams. Systems thinking unpacks the value chain within an organisation and externally. It complements design thinking: together they’re a dynamic duo.

For starters, this philosophy needs to enter our everyday thinking. Yes, it is crucial for innovation, but an easy first step is to use systems thinking casually throughout your life. How is this purchase affecting other systems in the supply chain? What is the local economic impact of me shopping at the larger supermarket? Who will be the most negatively impacted if I don’t practice social distancing?

This mapping tool from the World Economic Forum is central in understanding causal relationships and effects during COVID-19. It helps to drive systems-informed decision making. Once this becomes mainstream, we can begin integrating data for systems modelling tools that will help us map impact across the multiple layers of influence from this pandemic. So, what does this mean for businesses?

Systems thinking for business

To illustrate how systems thinking applies in business, let's use a simplified example of a bank branch.

Event: COVID-19 declared a pandemic, lockdown implemented for all people and businesses, except key workers and essential firms. Branches are shutting, people are afraid to go to non-essential establishments.

Patterns/trends: what trends have there been over time? Scientists have warned us about being ‘pandemic-ready’ for years, but we have had misinformation or a lack of transparency from other ‘systems’ who should have been driving this.

However, what about banking patterns? More customer service has moved online, digital banks and fintech developments have decreased the urgency for face-to-face business in branches. Are there trends in customer behaviours? More consumers are searching for all their products and services online, and this was common before the pandemic had begun.

Underlying structures: what has influenced these patterns and how are they interconnected? A growing desire for digitalised experiences and convenience is popular in financial services and customers will begin to seek and only interact with businesses who have the infrastructure to operate this way. A minimal number of touchpoints is seen as desirable, providing quicker, stress-free experiences, as consumers want to spend less time on these engagements when work-life balance has become more integrated, and therefore is important to preserve.

Mental models: what assumptions, beliefs and values do people hold about the system? Behavioural economics tells us that customers will adapt and change their consumer spending habits. Used to the convenience of online, less relevance will be seen for branches, and banks will need to further adapt. The ‘new normal’ will contain old and new beliefs. Which ones keep bank branches in place? Human contact and customer service? The agency in dealing with your finances face-to-face? Will a new experience or service be required to keep bank branches relevant or are online digital banks all consumers will need?

Beyond this, do banks have an ethical obligation to monitor spending habits to identify signs of debt and underlying mental health problems? What relationship should banks have with data? How do they balance intuitive service with consumer privacy?

Going through the layers of this iceberg unearths part of the power from using systems thinking and exemplifies how to guide your strategy in a sustainable way.

Only focusing on events? You’re reacting.

Thinking about patterns/trends? You’re anticipating.

Unpicking underlying structures? You’re designing.

Understanding mental models? You’re transforming.

Transformative thinking is how we innovate and systems thinking is essential for this journey.

We’ve only explored the tip of the iceberg (pun intended) on the philosophy of systems thinking. There are many in-depth tools available to discover the approach in more depth.

Ask yourselves if you want to survive the VUCA future ahead. Do you want your organisation to have the capacity to innovate and sustain itself? Are you willing to change your thought pattern to consider the systems in which we all live in?

If the answers to any of the questions above are yes, then you are on the right path to mastering systems thinking to successfully innovate.

The more we begin to use systems thinking every day, the better our innovation will become. We can all be architects for a better world with sustainable growth if we understand the core tenants of this approach. To echo my introduction, no customer, or citizen, or business, or policy, or company, or idea itself is an island. Whatever ‘new normal’ we have, systems thinking should drive this future and will ensure innovation is pursued with knowledge of the complex intricacies that we are living through.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Leadership .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

This is what businesses need to be focusing on in 2024, according to top leaders

Victoria Masterson

April 16, 2024

3 ways leaders can activate responsible leadership in uncertain times

Ida Jeng Christensen

April 8, 2024

The catalysing collective: Announcing the Class of 2024

April 4, 2024

What we learned about effective decision making from Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman

Kate Whiting

March 28, 2024

Women founders and venture capital – some 2023 snapshots

Lessons in leadership and adventure from Kat Bruce

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Systems Thinking

What is systems thinking.

Systems thinking is an approach that designers use to analyze problems in an appropriate context. By looking beyond apparent problems to consider a system as a whole, designers can expose root causes and avoid merely treating symptoms. They can then tackle deeper problems and be more likely to find effective solutions.

“You have to look at everything as a system and you have to make sure you're getting at the underlying root causes.”

— Don Norman, “Grand Old Man of User Experience”

See why systems thinking helps prevent wasted time and resources on the wrong problem.

- Transcript loading…

Everything is a System: Think of Each as One

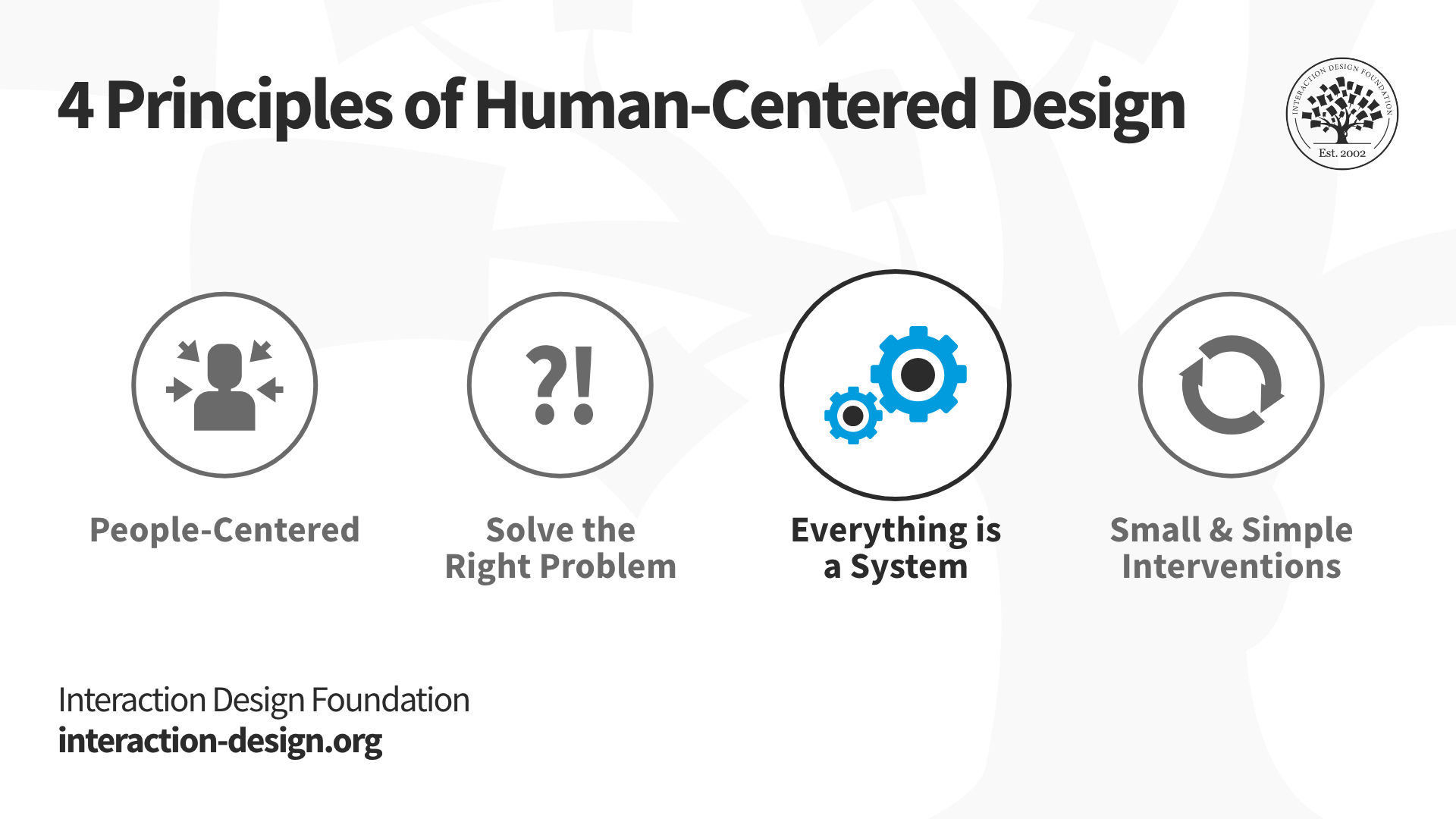

Systems surround us, including within our own bodies, and they’re often highly complex. For example, that’s why doctors must know patients’ medical histories before prescribing them medicines. However, our brains are hardwired to find simple, direct causes of problems from the effects we see. We typically isolate issues we notice by considering how to combat their symptoms, since we’re more comfortable with “If X, then Y” cause-and-effect relationships. Cognitive science and usability engineering expert Don Norman identifies the need for designers to push far beyond this tendency if they want to address serious global-level problems effectively. That’s why systems thinking is not only an essential ingredient of 21st century design but also a principle of human-centered design .

The concept of systems thinking emerged in 1956, when Professor Jay W. Forrester of MIT’s Sloan School of Management created the Systems Dynamic Group. Its purpose was to predict system behavior graphically, including through the behavior over time graph and causal loop diagram. For designers, systems thinking is therefore vital to tackling larger global evils such as hunger, poor sanitation and environmental abuse. Norman calls such problems complex socio-technical systems , which, like wicked problems , are:

● Difficult to define.

● Complex systems.

● Difficult to know how to approach.

● Difficult to know whether a solution has worked.

The danger of not using a systems thinking approach is that we might oversimplify a situation, take problems out of context, treat symptoms and end up making matters even worse. Norman considers electric vehicles an example of an apparently good solution (to pollution) that can obscure what should be the real focus. If the fuel source that generates their electricity comes from coal, etc., it defeats the purpose and, worse, could cause even more world-damaging pollution, especially if so much electricity perishes between the generating source and the consumers’ power supply.

© Daniel Skrok and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

How to Use Systems Thinking in Design

Systems thinking is also the third principle of humanity-centered design ; therefore, integrate it within this approach:

● Be people-centered. Spend a long time living among the people you want to help, to understand the true nature of their problems, their viewpoints and solutions they’ve tried. For example, a village’s crops might be failing even though the water source seems adequate.

● Solve the right problem . Closely examine the factors driving the people’s problems. Try the 5 Whys approach. E.g., the soil is damp enough, so might it be exhausted of nutrients? Or does it contain toxins? Why? Sewage? If not, what then?

● Consider everything as a system . Now, leverage systems thinking to untangle as many parts of the problem(s) as possible. Complex socio-technical systems such as (potential) famine demand hard investigation and working alongside others: principally, the community concerned; so:

Keep consulting the community leaders for their insights into the problems you uncover.

Evaluate the feedback loops . E.g., the collected clean water from a small stream and secondary well should be enough to irrigate the village’s few fields. The people seem to be doing things correctly: using pipes and a small ditch they’ve diverted from the stream and enclosed using plastic sheets strung over metal frames. The soil is adequately fertilized; the farmers water after dusk (operating taps and a sluice from the tunnel). Still, the problem persists.

Dig past the apparent problems to root causes. E.g., thinking of the village’s irrigation system as a system, you notice it’s not the amount of water or soil quality . The water is slightly too hot — due to the dark-colored plastic pipes and the black plastic sheeting of the improvised tunnel — for the crops to handle.

● Proceed towards a viable solution using incrementalism :

Wait for the opportunity to do a small test of the small-scale solution you’ve co-created with the community. E.g., fortunately, here, a good solution involves just lightening the color of the irrigation system to reflect sunlight. The village has enough white paint for the pipes, and you collect white sheeting and tarpaulins to cover the stream tunnel.

If it’s successful, evaluate how successful; then adapt and modify it or repeat it several times until you fine-tune a sustainable solution. E.g., fortunately, you just need to find more light-colored tarpaulins.

Overall, systems thinking is about reframing a problem to expose its addressable underlying causes. Thinking broadly, you can deduce real problems and stop to consider potential solutions with (e.g.) design thinking . That’s how community-driven projects — and people-centered design — arrive at inventive, economical and culturally acceptable best-possible solutions.

Learn More about Systems Thinking

Use the 5 Whys method to help you find the root causes. Take our 21st Century Design course with Don Norman if you want to dig deeper and help solve some of the world’s most complex problems. You can of course also use the insights to design “normal” products and services.

If you want to know more about how you can apply system thinking and many other humanity-centered design tools to help solve the world’s biggest problems you can take our course Design for a Better World with Don Norman .

Here’s an article on why we need to see our work through a systems thinking lens .

Here’s another designer’s insight-rich piece about what systems thinking means and how it’s related to design thinking .

Literature on Systems Thinking

Here’s the entire UX literature on Systems Thinking by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Systems Thinking

Take a deep dive into Systems Thinking with our course Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman .

In this course, taught by your instructor, Don Norman, you’ll learn how designers can improve the world , how you can apply human-centered design to solve complex global challenges , and what 21st century skills you’ll need to make a difference in the world . Each lesson will build upon another to expand your knowledge of human-centered design and provide you with practical skills to make a difference in the world.

“The challenge is to use the principles of human-centered design to produce positive results, products that enhance lives and add to our pleasure and enjoyment. The goal is to produce a great product, one that is successful, and that customers love. It can be done.” — Don Norman

All open-source articles on Systems Thinking

What are wicked problems and how might we solve them.

Which Skills Does a 21st Century Designer Need to Possess?

- 2 years ago

Human-Centered Design: How to Focus on People When You Solve Complex Global Challenges

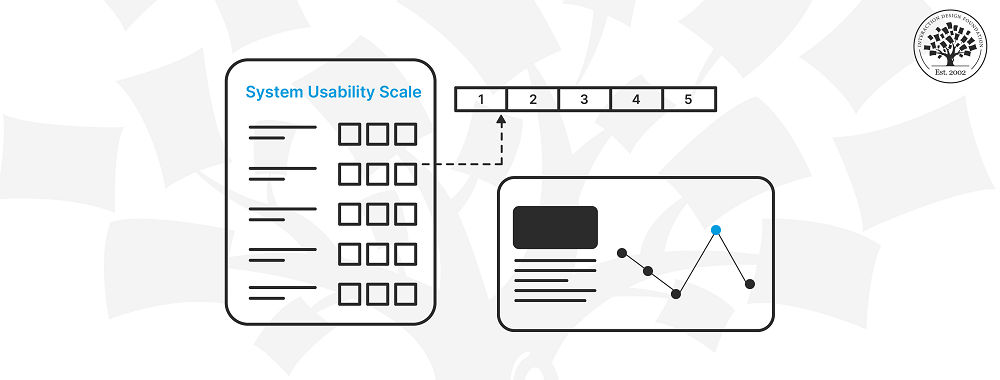

System Usability Scale for Data-Driven UX

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

Insight and inspiration in turbulent times.

- All Latest Articles

- Environment

- Food & Water

- Featured Topics

- Get Started

- Online Course

- Holding the Fire

- What Could Possibly Go Right?

- About Resilience

- Fundamentals

- Submission Guidelines

- Commenting Guidelines

Act: Inspiration

Systems thinking, critical thinking, and personal resilience.

By Richard Heinberg , originally published by Resilience.org

May 24, 2018

As a writer focused on the global sustainability crisis, I’m often asked how to deal with the stress of knowing—knowing, that is, that we humans have severely overshot Earth’s long-term carrying capacity, making a collapse of both civilization and Earth’s ecological systems likely; knowing that we are depleting Earth’s resources (including fossil fuels and minerals) and clogging its waste sinks (like the atmosphere’s and oceans’ ability to absorb CO2); knowing that the decades of rapid economic growth that characterized the late 20 th and early 21 st centuries are ending, and that further massive interventions by central banks and governments can’t do more than buy us a little bit more time of relative stability; knowing that technology (even renewable energy technology) won’t save our fundamentally unsustainable way of life.

In the years I’ve spent investigating these predicaments, I’ve been fortunate to meet experts who have delved deeply into specific issues—the biodiversity crisis, the population crisis, the climate crisis, the resource depletion crisis, the debt crisis, the plastic waste crisis, and on and on. In my admittedly partial judgment, some of the smartest people I’ve met happen also to be among the more pessimistic. (One apparently smart expert I haven’t had opportunity to meet yet is 86-year-old social scientist Mayer Hillman, the subject of this recent article in The Guardian .)

In discussing climate change and all our other eco-social predicaments, how does one distinguish accurate information from statements intended to elicit either false hope or needless capitulation to immediate and utter doom? And, in cases where pessimistic outlooks do seem securely rooted in evidence, how does one psychologically come to terms with the information?

Systems Thinking

First, if you want to have an accurate picture of the world, it’s vital to pay attention to the connections between things. That means thinking in systems. Evidence of failure to think in systems is all around us, and there is no better example than the field of economics, which treats the environment as simply a pile of resources to be plundered rather than as the living and necessary context in which the economy is grounded. No healthy ecosystems, no economy. This single crucial failure of economic theory has made it far more difficult for most people, and especially businesspeople and policy makers, to understand our sustainability dilemma or do much about it.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the field in which systems thinking is most highly developed is ecology—the study of the relationships between organisms and their environments. Since it is a study of relationships rather than things in isolation, ecology is inherently systems-oriented.

Systems thinking has a pre-history in indigenous thought ( Mitákuye Oyás’i ŋ , or “All are related,” is a common phrase in the Lakota language). But as a formal scientific pursuit it emerged only during the latter part of the twentieth century. Previously, Western scientists often assumed that they could understand systems just by analyzing their parts; however, it gradually became clear—in practical fields from medicine to wildlife management to business management—that this often led to unintended consequences.

In medicine, it is understood that treating diseases by managing symptoms is not as desirable as treating the disease itself; that’s partly because symptomatic treatment with pharmaceuticals can produce side effects that can be as distressing as the original disease symptoms. Take a pill and you may feel better for a while, but you may soon have to deal with a whole new slew of aches, rashes, sleep problems, mood swings, or digestive ailments. Further, truly curing a disease often involves addressing exposure to environmental toxins; or lifestyle choices including poor nutrition, smoking, lack of exercise, or job-related repetitive stress injuries—all of which are systemic issues that require treating the whole person and their environment, not just the symptoms, or even just the disease in isolation.

In order to address systemic problems we need to understand what systems are, and how to intervene in them most effectively.

All systems have:

- Boundaries , which are semi-permeable separations between the inside and outside of systems;

- Inputs of energy, information, and materials;

- Outputs , including work of various kinds, as well as waste heat and waste materials;

- Flows to and from the environment;

- Stocks of useful nutrients, resources, and other materials; and

- Feedbacks , of which there are two kinds: balancing or negative, like a thermostat; and self-reinforcing or positive, which is the proverbial vicious circle. Systems need balancing feedback loops to remain stable and can be destabilized or even destroyed by self-reinforcing feedback loops.

The human body is a system that is itself composed of systems, and the body exists within larger social and ecological systems; the same could be said of a city or a nation or a company. A brick wall, in contrast, doesn’t have the characteristics of a system: it may have a boundary, but there are few if any meaningful ongoing inputs and outputs, information flows, or feedbacks.

The global climate is a system, and climate change is therefore a systemic problem. Some non-systems thinkers have proposed solving climate change by putting chemicals in the Earth’s atmosphere to manage solar radiation. Because this solution addresses only part of the systemic problem, it is likely to have many unintended consequences. Systems thinking would suggest very different approaches—such as reducing fossil fuel consumption while capturing and storing atmospheric carbon in replanted forests and regenerated topsoil. These approaches recognize the role of inputs (such as fossil fuels), outputs (like carbon dioxide), and feedbacks (including the balancing feedback provided by soil carbon flows).

In some cases, a systemic approach to addressing climate change could have dramatic side benefits: regenerative agriculture would not just sequester carbon in the soil, it would also make our food system more sustainable while preserving biodiversity. Interventions based in systems thinking often tend to solve many problems at once.

Donella Meadows, who was one of the great systems thinkers of the past few decades, left us a brilliant essay titled “ Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System .” There are places within every complex system where “a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything.” Meadows suggested that these leverage points have a hierarchy of effectiveness. She said that the most powerful interventions in a system address its goals, rules, and mindsets, rather than parameters and numbers—things like subsidies and taxes. This has powerful implications for addressing climate change, because it suggests that subsidizing renewable energy or taxing carbon is a fairly weak way of inducing systemic change. If we really want to address a deeply rooted, systemic problem like climate change, we may need to look at our society’s most fundamental paradigms—like, for example, the assumption that we must have continual economic growth.

We intuitively know that systems are more than the sum of their parts. But digging deeper into the insights of systems theory—going beyond the basics—can pay great dividends both in our understanding of the world, and in our strategic effectiveness at making positive change happen. A terrific resource in this regard is Meadows’s book Thinking in Systems .

Systems thinking often tends to lead to a more pessimistic view of our ecological crisis than thinking that focuses on one thing at a time, because it reveals the shortcomings of widely touted techno-fixes. But if there are truly useful strategies to be found, systems thinking will reveal them.

Critical Thinking

Human thought is rooted partly in words, partly in emotions, and partly in the body states (whether you feel alert, sleepy, hungry, agitated, etc.) that may accompany or give rise to emotions; another way of saying this is that our thought processes are partly conscious but mostly unconscious. In our conscious lives we are immersed in a soup of language, which often simply expresses judgments, intuitions, and observations that emerge from unconscious thought. But thought that’s expressed in language has great potential. Using language (including mathematics), we can assess the validity of statements about the world, then build upon proven statements until we ultimately achieve comprehensive scientific understandings and the capacity to manipulate reality in new ways (to build a bridge, for example, or land a probe on a distant asteroid, or update an app).

Of course, language can be powerful in another way. Some of us use language to persuade, confuse, or mislead others so as to gain social or economic power. Appeals to unconscious prejudices, including peer group-think, are frequently employed to sway the masses. The best protection against being the subject of verbal manipulation is the ability to use language to distinguish logic from illogic, truth from untruth. Critical thinking helps us separate information from propaganda. It can help us think more clearly and productively.

One way to approach critical thinking is through the study of logic—including formal logic (which builds conclusions almost mathematically, using syllogisms), informal logic (which also considers content, context, and delivery), and fuzzy logic (which recognizes that many qualities are subjective or matters of degree). Most of our daily thinking consists of informal and fuzzy logic.

The study of formal logic starts with learning the difference between deductive reasoning (which proceeds from a general principle to a special case, sometimes referred to as “top-down reasoning”) and inductive reasoning (which makes broad generalizations from specific observations, also called “bottom-up reasoning”).

Both deductive and inductive forms of reasoning can be misapplied. One might deduce from the general rule “human history is a grand narrative of progress” that therefore humanity will successfully deal with the ecological challenges of the 21 st century and emerge smarter, wealthier, and more virtuous than ever. Here the problem is that the general rule is laden with value judgments and subject to many exceptions (such as the collapse of various historical civilizations). Inductive reasoning is even more perilous, because there is always the danger that specific observations, from which one is drawing general conclusions, are incomplete or even misleading (economic growth has occurred in most years since World War II; therefore, economic growth is normal and can be expected to continue, with occasional brief setbacks, forever).

My favorite book on logic and its fallacies is Lean Logic by the late David Fleming, a British economist-philosopher who cofounded what eventually became the Green Party in the UK, and who originated the idea of Tradable Energy Quotas . There’s no simple way to sum up Fleming’s book, which is organized as a dictionary. Among many other things, it explores a wide range of logical fallacies—especially as they relate to our sustainability crises—and does so in a way that’s playful, artful, and insightful.

One of my favorite sections of the book is a four-page collection of ways to cheat at an argument. Here are just a few of the entries, chosen mostly at random:

Absence. Stop listening. Abstraction. Keep the discussion at the level of high-flown generality. Anger. Present it as proof of how right you are. Blame. Assume that the problem is solved when you have found someone to blame. Bullshit. Talk at length about nothing. Causes. Assume that an event which follows another event was therefore caused by it. Evil motive. Explain away the other side’s argument by the brilliance of your insight about their real intentions. False premise. Start with nonsense. Build on it with meticulous accuracy and brilliance. Old hat. Dismiss an argument on the grounds that you have disregarded it before.

Critical thinking should not necessarily elevate reason above intuition. Remember: most thought is unconscious and emotion-driven—and will continue to be, no matter how rigorously we analyze our verbal and mathematical expressions of thought. Just as we seek coherence and consistency in our conscious logic, we should seek to develop emotional intelligence if we hope to contribute to a society based on truth and conviviality. Lean Logic reveals on almost every page its author’s commitment to this deeper concept of critical thinking. Here’s one illustrative entry:

Reasons, The Fallacy of. The fallacy that, because a person can give no reasons, or only apparently poor reasons, her conclusion can be dismissed as wrong. But, on the contrary, it may be right: her thinking may have the distinction of being complex, intelligent and systems-literate, but she may not yet have worked out how to make it sufficiently clear and robust to objections to survive in an argument.

As politics becomes more tribal, critical thinking skills become ever more important if you want to understand what’s really going on and prevent yourself from becoming collateral damage in the war of words.

Personal Resilience

Let’s return to the premise of this essay. Suppose you’ve applied systems thinking and critical thinking to the information available to you about the status of the global ecosystem and have come to the conclusion that we are—to use a technical phrase—in deep shit. You want to be effective at helping minimize risk and damage to ecosystems, humanity, yourself, and those close to you. To achieve this, one of the first things you will need to do is learn to maintain and use your newfound knowledge without becoming paralyzed or psychologically injured by it.

Knowledge of impending global crisis can cause what’s been called “ pre-traumatic stress disorder .” As with other disorders, success in coping or recovery can be enhanced through developing personal or psychological resilience. Fortunately, psychological resilience is a subject that is increasingly the subject of research.

Some people bounce back from adversity relatively easily, while others seem to fall apart. The reason doesn’t seem to have much to do with being more of an optimist than a pessimist. Research has shown that resilient people realistically assess risks and threats; studies suggest that in some ways pessimists can have the advantage . What seems to distinguish resilient people is their use of successful coping techniques to balance negative emotions with positive ones, and to maintain an underlying sense of competence and assurance.

Researchers have isolated four factors that appear critical to personal psychological resilience:

- The ability to make realistic plans and to take the steps necessary to follow through with them;

- A positive self-concept and confidence in one’s strengths and abilities;

- Communication and problem-solving skills; and

- The ability to manage strong impulses and feelings.

An important question: To what degree is psychological resilience based on inherited or innate brain chemistry, or childhood experiences, versus learned skills? We each have a brain chemistry that is determined partly by genetic makeup and partly by early life experience. Some people enjoy a naturally calm disposition, while others have a hair-trigger and are easily angered or discouraged. In seeking to develop psychological resilience, it’s important to recognize and deal with your personal predispositions. For example, if you find that you are easily depressed, then it may not be a good idea to spend hours each day glued to a computer, closely following the unraveling of global ecological and social systems. Don’t beat yourself up for getting depressed; just learn to recognize your strengths and limits, and take care of yourself.

Nevertheless, research suggests that, regardless of your baseline temperament, you can make yourself more psychologically resilient through practice. The American Psychological Association suggests “10 Ways to Build Resilience,” which are:

- Maintain good relationships with close family members, friends and others.

- Avoid seeing crises or stressful events as unbearable problems.

- Accept circumstances that cannot be changed.

- Develop realistic goals and move towards them.

- Take decisive actions in adverse situations.

- Look for opportunities of self-discovery after a struggle with loss.

- Develop self-confidence.

- Keep a long-term perspective and consider the stressful event in a broader context.

- Maintain a hopeful outlook, expecting good things and visualizing what is wished.

- Take care of your mind and body, exercise regularly, and pay attention to your needs and feelings.

These recommendations are easier said than done. Learning new behaviors, especially ones that entail changing habitual emotional responses to trigger events, can be difficult. The most effective way to do so is to find a way to associate a neurotransmitter reward with the information or behavior being learned. For example, if you are just beginning an exercise regimen, continually challenge yourself to make incremental improvements that are just barely within your reach. This activates the dopamine reward circuits in your brain.

Psychological resilience may also entail learning to deal with grief . Awareness of species extinctions, habitat destruction, and the peril to human beings from climate change naturally evokes grief, and unexpressed grief can make us numb, depressed, and ineffective. It’s helpful therefore to find a safe and supportive environment in which to acknowledge and express our grief. Joanna Macy , in her “work that reconnects,” has for many years been hosting events that provide a safe and supportive environment for grief work.

Personal resilience extends beyond the psychological realm; developing it should also include identifying and learning practical skills (such as gardening, small engine maintenance, plumbing, cooking, natural building, primitive technology, and wilderness survival skills). Knowing practically how to take care of yourself improves your psychological state, as well as making you more resilient in physical terms.

Further, your personal resilience will be greatly enhanced as you work with others who are also blessed (or burdened) with knowledge of our collective overshoot predicament. For many years we at PCI have been assisting in the formation of ongoing communities of reflection and practice such as Transition Initiatives . If that strategy makes sense to you, but you don’t have a Transition group close by, you might take the Think Resilience course and then host a discussion group in your school, home, or public library.

Systems thinking, critical thinking, and personal resilience building don’t, by themselves, directly change the world. However, they can support our ability and efforts to make change. The key, of course, is to apply whatever abilities we have—in community resilience building, ecological restoration, or efforts to resist the destruction of nature and the exploitation of human beings. As we remain open to learning, action presents opportunities for still more learning, in the form of what systems thinkers would call balancing feedback. We test what we think we know, and discover new things about the world and ourselves. It’s a life-long process.

Even if we do all we can, there is no guarantee that problems will be solved, extinctions prevented, collapse forestalled. But paralysis only guarantees the very worst outcome. In the words of the Bhagavad Gita, “The wise should work, without attachment to results, for the welfare of the world.” Act from love with the best understanding you have, and always seek to improve your understanding. It’s all that any of us can do.

Feature Image Credit: Renaud Camus , c/o Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/renaud-camus/8434440715/

Richard Heinberg

Related articles.

Discussion Session with the Good Grief Network: Lessons and Practices for Facing the Great Unraveling

LaUra Schmidt of the Good Grief Network will lead an interactive session featuring grounding exercises, reflections on the webinar with Lise van Susteren and Dekila Chungyalpa, chances to share your experiences with eco-anxiety, and deep listening among colleagues.

April 26, 2024

Crazy Town 85. Escaping Globalism: Rebuilding the Local Economy One Pig Thyroid at a Time

By Asher Miller , Rob Dietz , Jason Bradford , Resilience.org

From the top of a skyscraper in Dubai, Jason, Rob, and Asher chug margaritas made from the purest Greenland glacier ice as they cover the “merits” of globalism. International trade brings so many things, like murder hornets and deadly supply chain disruptions. The opposite of globalism is localism — learn how to build a secure local economy that can keep Asher alive, hopefully at least through the end of the season.

April 24, 2024

Kumi Naidoo: Origins and Self-Care in the Journey for Justice

By Post Carbon Institute , Resilience.org

For more than 40 years, Kumi Naidoo has been a voice for social, economic and environmental justice. To get a glimpse into Kumi’s story and what he will talk about in our May 14th event, watch this interview with Post Carbon Institute’s Asher Miller.

April 23, 2024

- Ideas for Action

- Join the MAHB

- Why Join the MAHB?

- Current Associates

- Current Nodes

- What is the MAHB?

- Who is the MAHB?

- Acknowledgments

Systems Thinking, Critical Thinking, and Personal Resilience

| May 25, 2018 | Leave a Comment

Image by Saad Faruque | Flickr | CC BY-SA 2.0

Item Link: Access the Resource

Date of Publication: May 24, 2018

Year of Publication: 2018

Publication City: Santa Rosa, CA

Publisher: Post Carbon Institute

Author(s): Richard Heinberg

Richard Heinberg discusses how systems thinking, critical thinking, and personal resilience are central to dealing with “knowing —knowing, that is, that we humans have severely overshot Earth’s long-term capacity making a collapse of both civilization and Earth’s ecological systems likely…”

In discussing climate change and all our other eco-social predicaments, how does one distinguish accurate information from statements intended to elicit either false hope or needless capitulation to immediate and utter doom? And, in cases where pessimistic outlooks do seem securely rooted in evidence, how does one psychologically come to terms with the information?

For Heinberg, systems thinking provides the most accurate picture, critical thinking helps us think more clearly and productively, and personal resilience aids us in maintaining and using knowledge of the world without becoming paralyzed or psychologically injured by it.

Read the full article .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMJ Open Qual

- v.9(1); 2020

Development and application of ‘systems thinking’ principles for quality improvement

Duncan mcnab.

1 Medical Directorate, NHS Education for Scotland, Glasgow, UK

2 Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom

Steven Shorrock

3 EUROCONTROL, Brussels, Belgium

4 University of the Sunshine Coast Sippy Downs Campus, Sippy Downs, Queensland, Australia

Associated Data

bmjoq-2019-000714supp001.pdf

bmjoq-2019-000714supp002.pdf

Introduction

‘Systems thinking’ is often recommended in healthcare to support quality and safety activities but a shared understanding of this concept and purposeful guidance on its application are limited. Healthcare systems have been described as complex where human adaptation to localised circumstances is often necessary to achieve success. Principles for managing and improving system safety developed by the European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL; a European intergovernmental air navigation organisation) incorporate a ‘Safety-II systems approach’ to promote understanding of how safety may be achieved in complex work systems. We aimed to adapt and contextualise the core principles of this systems approach and demonstrate the application in a healthcare setting.

The original EUROCONTROL principles were adapted using consensus-building methods with front-line staff and national safety leaders.

Six interrelated principles for healthcare were agreed. The foundation concept acknowledges that ‘most healthcare problems and solutions belong to the system’. Principle 1 outlines the need to seek multiple perspectives to understand system safety. Principle 2 prompts us to consider the influence of prevailing work conditions—demand, capacity, resources and constraints. Principle 3 stresses the importance of analysing interactions and work flow within the system. Principle 4 encourages us to attempt to understand why professional decisions made sense at the time and principle 5 prompts us to explore everyday work including the adjustments made to achieve success in changing system conditions.

A case study is used to demonstrate the application in an analysis of a system and in the subsequent improvement intervention design.

Conclusions

Application of the adapted principles underpins, and is characteristic of, a holistic systems approach and may aid care team and organisational system understanding and improvement.

Adopting a ‘systems thinking’ approach to improvement in healthcare has been recommended as it may improve the ability to understand current work processes, predict system behaviour and design modifications to improve related functioning. 1–3 ‘Systems thinking’ involves exploring the characteristics of components within a system (eg, work tasks and technology) and how they interconnect to improve understanding of how outcomes emerge from these interactions. It has been proposed that this approach is necessary when investigating incidents where harm has, or could have, occurred and when designing improvement interventions. While acknowledged as necessary, ‘systems thinking’ is often misunderstood and there does not appear to be a shared understanding and application of related principles and approaches. 4–6 There is a need, therefore, for an accessible exposition of systems thinking.

Systems in healthcare are described as complex. In such systems it can be difficult to fully understand how safety is created and maintained. 7 Complex systems consist of many dynamic interactions between people, tasks, technology, environments (physical, social and cultural), organisational structures and external factors. 8–10 Care system components can be closely ‘coupled’ to other system elements and so change in one area can have unpredicted effects elsewhere with non-linear, cause–effect relations. 11 The nature of interactions results in unpredictable changes in system conditions (such as patient demand, staff capacity, available resources and organisational constraints) and goal conflicts (such as the frequent pressure to be efficient and thorough). 12 13 To achieve success, people frequently adapt to these system conditions and goal conflicts. But rather than being planned in advance, these adaptations are often approximate responses to the situations faced at the time. 14 Therefore, to understand safety (and other emergent outcomes such as workforce well-being) we need to look beyond the individual components of care systems to consider how outcomes (wanted and unwanted) emerge from interactions in, and adaptations to, everyday working conditions. 14

Despite the complexity of healthcare systems, we often appear to treat problems and issues in simple, linear terms. 15–17 In simple systems (eg, setting your alarm clock to wake you up) and many complicated systems (eg, a car assembly production line) ‘cause and effect’ are often linked in a predictable or linear manner. This contrasts sharply with the complexity, dynamism and uncertainty associated with much of healthcare practice. 1 7 18 For example, in a study to evaluate the impact of a comprehensive pharmacist review of patients’ medication after hospital discharge, the linear perspective suggested that this specific intervention would improve the safety and quality of medication regimens and so reduce healthcare utilisation. 19 Unexpectedly the opposite result was observed. The authors suggested that this emergent outcome may have been due to the increased number of interactions with different healthcare professionals increasing the complexity of care resulting in greater anxiety, confusion and dependence on healthcare workers.

Analyses of safety issues in healthcare routinely examine how safety is destroyed or degraded but have surprisingly little to say about how it is created and maintained. In the UK, like many parts of the world, root cause analysis is the recommended method for analysing events with an adverse outcome. 20 At its best, this should take a ‘systems approach’ to identify latent system conditions that interacted and contributed to the event and recommend evidence-based change to reduce the risk of recurrence. 20 However, we find that the results of such analyses are commonly based on linear ‘cause and effect’ assumptions and thinking. 15 16 21 22 Despite allusions to ‘root causes’, investigation approaches have a tendency to focus on single system elements such as people and/or items of equipment, rather than attempting to understand the interacting relationships and dependencies between people and other elements of the sociotechnical system from which safety performance and other outcomes in complex systems emerge. 21 By focusing on components in isolation, proposed improvement interventions risk unintended consequences in other parts of the systems and enhanced performance of the targeted component rather than the overall system. The validity of focusing on relatively infrequent, unwanted events has been questioned as it does not always reveal how wanted outcomes usually occur and may limit our learning on how to improve care. 22

Despite much related activity internationally, the impact of current safety improvement efforts in healthcare is limited. 23–25 Similar to other safety-critical industrial sectors, such as nuclear power or air traffic control, there is a growing realisation in healthcare that exploring how safety is created in complex systems may add value to existing learning and improvement efforts. The European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL), a pan-European intergovernmental air navigation organisation, published a white paper, Systems Thinking for Safety: Ten Principles . 26 This sets out a way of thinking about safety in organisations that aligns with systems thinking and applies ‘Safety-II’ principles, for which there is also growing interest in healthcare. 27 This latter approach attempts to explain and potentially resolve some of the ‘intractable problems’ associated with complex systems such as those found in healthcare, which traditional safety management thinking and responses (termed Safety-I) have struggled to adequately understand and improve on. 28 The Safety-II approach aims to increase the number of events with a positive outcome by exploring and understanding how everyday work is done under different conditions and contexts. This can lead to a more informed appreciation of system functioning and complexity that may facilitate a deeper understanding of safety within systems. 29 30

In this paper, we describe principles for systems thinking in healthcare that have been adapted and contextualised from the themes within the EUROCONTROL ‘Systems Thinking for Safety’ white paper. Our goal was to provide an accessible framework to explore how work is done under different conditions to facilitate a deeper understanding of safety within systems. A case report applying these principles to healthcare systems is described to illustrate systems thinking in everyday clinical practice and how this may inform quality improvement (QI) work.

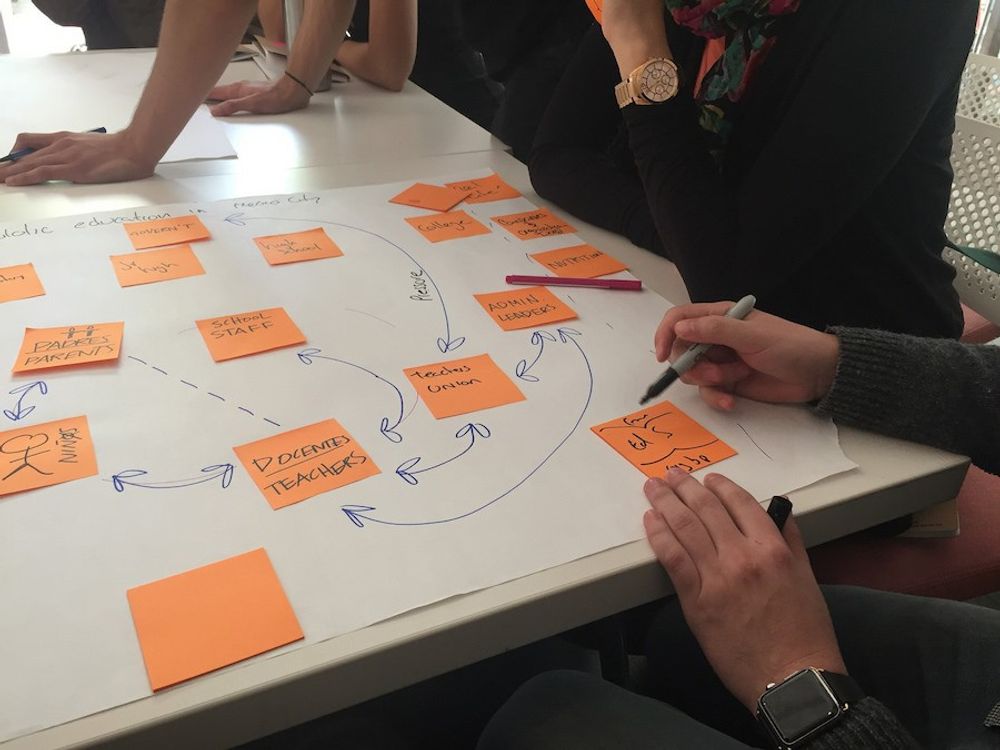

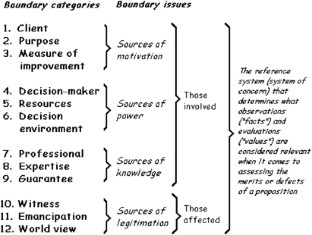

Adaptation of EUROCONTROL Systems Thinking Principles

A participatory codesign approach 31 was employed with informed stakeholders. 32 33 First, in March 2016, a 1-day systems thinking workshop was held for participants who held a variety of roles in front-line primary care (general practitioners (GP), practice nurses, practice managers and community pharmacists) and National Health Service (NHS) Scotland patient safety leaders ( table 1 ). The relevance and applicability of the EUROCONTROL white paper system principles were explored through presentations and discussion led by two experts in the field (including the original lead author of this document—SS). This was followed by a facilitated small group simulation exercise to apply the 10 principles to a range of clinical and administrative healthcare case studies ( online supplementary appendix 1 ) ( figure 1 ).

Systems Thinking for Everyday Work model.

Characteristics of attendees at Stage 1—‘Systems thinking’ workshop

Supplementary data

Second, two rounds of consensus building using the Questback online survey tool were undertaken with workshop participants in April and July 2016. 34

Finally, in May 2017, two 90 min workshops were held to test and refine the adapted principles with primary and secondary care medical appraisers (experienced medical practitioners with responsibility for the critical review of improvement and safety work performed by front-line peers).

At each stage, feedback was collected and analysed to identify themes related to applicability including wording, merging and missing principles. These themes directed the modification of the original principles and descriptors, which were then used at the next stage of development.

Throughout the process, external guidance and ‘sense-checking’ were provided by a EUROCONTROL human factors expert and lead author of the original systems thinking for safety white paper. While we believe the outputs from this work are generically applicable to all healthcare contexts, we have focused on the primary care setting for pragmatic purposes. The agreed principles are illustrated graphically in the Systems Thinking for Everyday Work (STEW) conceptual model ( figure 1 ), and detailed descriptions are provided in online supplementary appendix 2 .

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design of the study or the adaptation of the principles. The presented case study included a patient in the application of the principles to analyse the system. A service user read and commented on the manuscript and their feedback was incorporated into the final paper.

Systems Thinking for Everyday Work

The STEW principles consist of six inter-related principles ( figure 1 , tables 2 and 3 , online supplementary appendix 2 ). A fundamental, overarching conclusion is that the principles should not be viewed as isolated ideas, but instead as inter-related and interdependent concepts that can aid our understanding of complex work processes to better inform safety and improvement work by healthcare teams and organisations.

Adaptation of Systems Thinking Principles

EUROCONTROL, European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation.

Analysis of GP-based pharmacist work system

GP, general practitioner; STEW, Systems Thinking for Everyday Work.

Foundation concept

The foundation concept acknowledges that ‘ most healthcare problems and solutions belong to the system ’. This emphasises that the aim of applying a systems approach is to improve overall system functioning and not the functioning of one individual component within a system. For example, improving clinical assessments will not improve overall system performance unless patients can access assessments appropriately.

All systems interact with other systems, but out of necessity those analysing the system need to agree boundaries for the analysis. This may mean the GP practice building, a single hospital ward, the emergency department, a pharmacy or nursing home. Despite this, it is important to remember that external factors will influence the system under study and changes may have effects in parts of the system outside the boundary.

Multiple perspectives

Appreciate that people, at all organisational levels and regardless of responsibilities and hierarchical status, are the local experts in the work they do. Exploring the different perspectives held by these people, especially in relation to the other principles, is crucial when analysing incidents and designing and implementing change.

System conditions

Obtaining multiple perspectives allows an exploration of variability in demand and capacity, availability of resources (such as information or physical resources) and constraints (such as guidance that directs work to be performed in a particular way). These considerations can help identify leading indicators of impending trouble by identifying where demand may exceed capacity or where resources may not be available. Multiple perspectives can also help explore how work conditions affect staff well-being (eg, health, safety, motivation, job satisfaction, comfort, joy at work) and performance (eg, care quality, safety, productivity, effectiveness, efficiency).

Interactions and flow

System outputs are dependent on the constantly changing interactions between people, tasks, equipment and the wider environment. Multiple perspectives on system functioning help explore interactions to better understand the effects of actions and proposed changes on other parts of the system. Examining flow of work can help identify how these interactions and the conditions of work contribute to bottlenecks and blockages.

Understand why decisions made sense at the time

This principle directs us that, when looking back on individual, team or organisational decision-making, we should appreciate that people do what makes sense to them based on the system conditions experienced at the time (demand, capacity, resources and constraints), interactions and flow of work. It is easy (and common) to look back with hindsight to blame or judge individual components (usually humans) and recommend change such as refresher training and punitive actions. This must consider why such decisions were made, or change is unlikely to be effective. The same conditions may occur again, and the same decision may need to be made to continue successful system functioning. By exploring why decisions were made, we move beyond blaming ‘human error’ which can help promote a ‘Just Culture’—where staff are not punished for actions that are in keeping with their experience and training and which were made to cope with the work conditions faced at the time. 35

Performance variability

As work conditions and interactions change rapidly and often in an unpredicted manner, people adapt what they do to achieve successful outcomes. They make trade-offs, such as efficiency thoroughness trade-offs, and use workarounds to cope with the conditions they face. In retrospect these could be seen as ‘errors’, but are often adaptations used to cope with unplanned or unexpected system conditions. They result in a difference between work-as-done and work-as-imagined and define everyday work from which outcomes, both good and bad, emerge.

Case report

The included case report describes the practical application of these principles to understand work within a system and the subsequent design of organisational change ( table 3 ). The presented details are a small part of a larger project in which the authors (DM, PB and SL) were involved. The new appointment of a health board employed pharmacist to a general practice had not had the anticipated impact and there had been unexpected effects. The GPs had hoped for a greater reduction in workload quantity, the health board had hoped for increased formulary compliance and there had been increased workload in secondary care.

Traditional ways of exploring this problem may include working backwards from the problem to identify an area for improvement. In this case, further training of the pharmacist may have been suggested and targets may have been introduced in relation to workload or formulary compliance. However, without understanding why the pharmacist worked this way, it is likely any retraining or change would be ineffective. The STEW principles provided a framework to analyse the problem from a systems perspective, understand what influenced the pharmacist’s decisions and explore the effects of these decisions elsewhere in the system. Obtaining multiple perspectives identified that the pharmacist had to trade off between competing goals (productivity vs thoroughness including safety and formulary compliance). The application of the principles identified how pharmacists varied their approach to increase productivity while remaining safe. Learning from this everyday work helped bring work-as-done and work-as-imagined closer and several changes to improve system performance were identified and implemented.

Access to hospital electronic prescribing information

This ensured pharmacists had the information needed to complete the task ( System condition—resources ). It also reduced work in other sectors ( Interactions ) and increased the efficiency of task completion and so reduced delays for patients ( Flow ).

Work scheduling

The timetable for the week was changed to prioritise other prescribing tasks at the start of the week and complete medication reconciliation later in the week ( System condition—capacity/demand ). Through discussion of system conditions, the pharmacist identified that certain discharges took longer to complete, resulted in further contact with the practice (with a resultant increased GP workload) or had an increased risk of patient harm. Discharges that included these factors were prioritised and completed early in the week in attempt to mitigate these problems.

Protocols were changed to have minimum specification to allow local adaptation by pharmacists ( System conditions—constraints ). This supported the pharmacists to employ a variety of responses dependent on the context ( Performance Variability ) which reduced pharmacists’ concerns of blame if they did not follow the protocol ( Understand why decision made sense ). For example, after a short admission where it was unlikely medication was changed, pharmacists did not need to contact secondary care regarding medication not recorded on the discharge letter ( Understand why decision made sense ). If they felt they did have to check, the option of contacting the patient was included. Similarly, the need to contact all patients after discharge was removed. Pharmacists could use other options such as contacting the community pharmacy if more appropriate ( Performance Variability ).

Pharmacist mentoring

Regular GP mentoring sessions were included as pharmacists’ found discussing cases with GPs allowed them to consider the benefits and potential problems of their actions in other parts of the system (Interactions and Performance Variability ). For example, not limiting the number of times certain medication can be issued but instead ensuring practice systems for monitoring are used. This also allowed them to consider when they needed to be more thorough at the expense of efficiency ( Performance Variability ), for example, when there were leading indicators of problems such as high-risk medication.

This paper describes the adaptation and redesign of previously developed system principles for generic application in healthcare settings. The STEW principles underpin and are characteristic of a holistic systems approach. The case report demonstrates application of the principles to analyse a care system and to subsequently design change through understanding current work processes, predicting system behaviour and designing modifications to improve system performance.

We propose that the STEW principles can be used as a framework for teams to analyse, learn and improve from unintended outcomes, reports of excellent care and routine everyday work ‘hassles’. 36 37 The overall focus is on team and organisational learning by, for example, small group discussion to promote a deep understanding of ‘how everyday work is actually done’ (rather than just fixating on things that go wrong). This allows an exploration of the system conditions that result in the need for people to vary how they work; the identification and sharing of successful adaptations and an understanding of the effect of adaptations elsewhere in the system (mindful adaptation). From this, we can decide if variation is useful (and thus support staff in doing this effectively) or unwanted (and system conditions can then be considered to try to damp variation). These discussions can help reconcile work-as-done and work-as-imagined . Although, as conditions change unpredictably, new ways of working will continue to evolve and so we must continue to explore and share learning from everyday work, not just when something goes wrong.

The focus of safety efforts, in incident investigation and other QI activity, is often on identifying things that have gone wrong and implementing change to prevent ‘error’ recurring. 20 The focus is often on the ‘root causes’ of adverse events or categorising events most likely to cause systems to fail (eg, using Pareto charts). 20 38 This linear ‘cause and effect’ thinking can lead to single components, deemed to be the ‘cause’ of the unwanted event or care problem, being prioritised for improvement. Although this may improve the performance of that component it may not improve overall system functioning and, due to the complex interactions in healthcare systems, may generate unwanted unintended consequences. The principles promote examining and treating the relevant system as a whole which may strengthen the way we conduct incident investigation and how we design QI projects.

To successfully align corrective actions or improvement interventions with contributing factors, and therefore ensure actions have the desired effect, a deep understanding of everyday work is essential. 39 Methods such as process mapping are often promoted to explore how systems work which, when used properly, can be a useful method to aid healthcare improvers. To more closely model and understand work-as-done , the STEW principles could be considered to show the influences on components that affect performance such as feedback loops, coupling to other components and internal and external influences.