Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

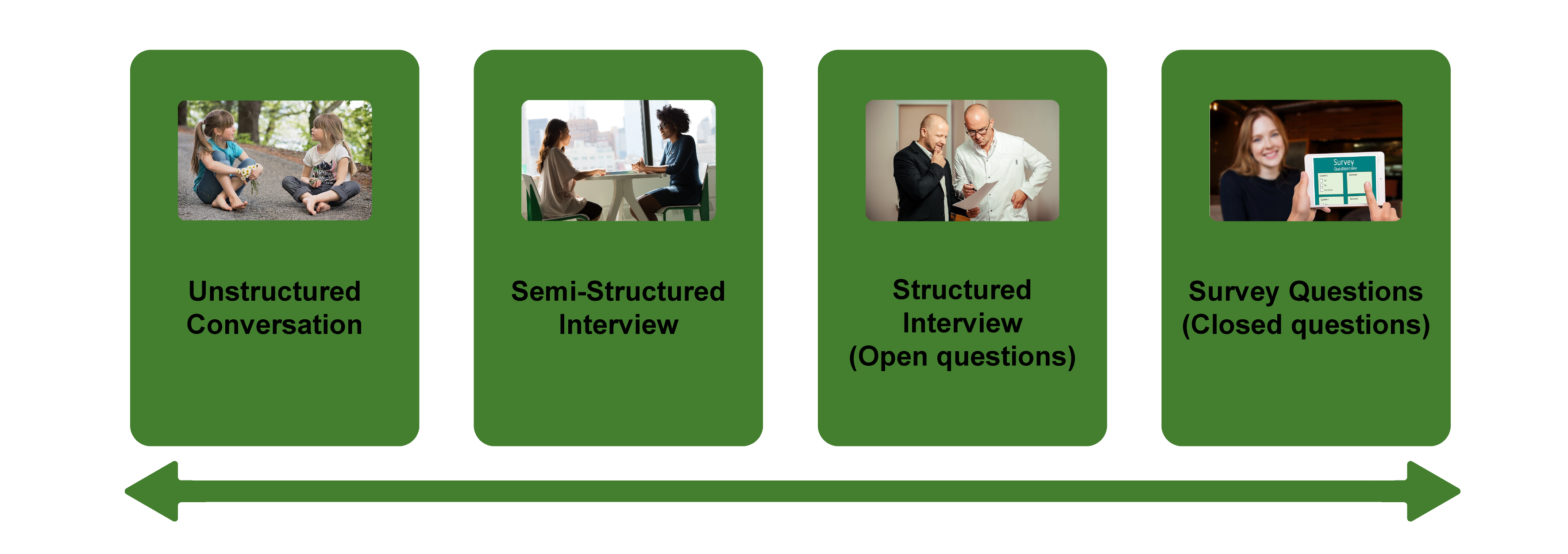

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Conducting qualitative interviews by telephone: Lessons learned from a study of alcohol use among sexual minority and heterosexual women

Laurie drabble.

San José State University School of Social Work, One Washington Square, San José, CA 95192-0124, (408) 924-5836, FAX: (408) 924-5912

Karen F. Trocki

Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute, 6475 Christie Ave. Suite 400, Emeryville, CA 94608, phone: 510-597-3440, fax: 510-985-6459

Brenda Salcedo

Social Worker, Special Services, East Side Union High School District, 830 N Capitol Ave, San Jose, CA 95133, Phone: 408.332.2836

Patricia C. Walker

Catholic Charities of Santa Clara County, 1670 Cherry Grove Drive, San Jose, CA 95125, phone: (408) 723-5201, fax: (408) 723-5201

Rachael A. Korcha

This study explored effective interviewer strategies and lessons-learned based on collection of narrative data by telephone with a sub-sample of women from a population-based survey, which included sexual minority women. Qualitative follow-up, in-depth life history interviews were conducted over the telephone with 48 women who had participated in the 2009–2010 National Alcohol Survey. Questions explored the lives and experiences of women, including use of alcohol and drugs, social relationships, identity, and past traumatic experiences. Strategies for success in interviews emerged in three overarching areas: 1) cultivating rapport and maintaining connection, 2) demonstrating responsiveness to interviewee content, concerns, and 3) communicating regard for the interviewee and her contribution. Findings underscore both the viability and value of telephone interviews as a method for collecting rich narrative data on sensitive subjects among women, including women who may be marginalized.

Introduction

Although the use of telephones for collecting quantitative survey data is common and well-represented in research literature, using telephones for qualitative interviews has generally been considered an inferior alternative to face-to-face interviews ( Novick, 2008 ). Qualitative interviews provide “a way of generating empirical data about the social world by asking people to talk about their lives” ( Holstein and Gubrium, 2003 , p. 3). Consequently, concerns about the use of telephones for qualitative interviews described in the literature predominately focus on the possible negative impact on the richness and quality of empirical data collected by telephone compared to face-to-face interviews ( Novick, 2008 ; Irvine et al., 2013 ). Some of the most commonly articulated concerns about telephone interviews include the challenges to establishing rapport, the inability to respond to visual cues, and potential loss of contextual data (i.e., the ability to observe the individual in a work or home environment) ( Novick, 2008 ; Holt, 2010 ; Smith, 2005 ).

A small but growing body of literature has documented the potential of in-depth telephone interviews as a viable option for qualitative research. Many methodological studies point to logistical conveniences and other practical advantages of telephone interviews, including enhanced access to geographically dispersed interviewees, reduced costs, increased interviewer safety, and greater flexibility for scheduling ( Cachia and Millward, 2011 ; Sturges and Hanrahan, 2004 ; Shuy, 2003 ; Carr and Worth, 2001 ; Musselwhite et al., 2007 ; Stephens, 2007 ). In addition to benefits related to convenience, several studies emphasize the methodological strengths of conducting qualitative interviews by telephone, such as perceived anonymity, increased privacy for respondents, and reduced distraction (for interviewees) or self-consciousness (for interviewers) when interviewers take notes during interviews ( Cachia and Millward, 2011 ; Sweet, 2002 ; Stephens, 2007 ; Lechuga, 2012 ). For example, privacy was noted as a strength of telephone interviews as an alternative to interviewing patients in a hospital setting ( Carr and Worth, 2001 ) or interviewing family members of incarcerated adults in a county jail ( Sturges and Hanrahan, 2004 ). Telephone interviews may also require interviewees to be explicit in follow-up questions, rather than relying on non-verbal cues ( Cachia and Millward, 2011 ). Finally, some researchers suggest that telephone interviews in qualitative data collection may mediate power dynamics that might otherwise emerge in the researcher-subject relationship. Specifically, telephone interviews, compared to in-person interviews, may be less intrusive and confer greater power and control to interviewees in terms of negotiating interviews to suit their schedules as well as rescheduling interrupting, or ending the interview ( Holt, 2010 ; Trier-Bieniek, 2012 ; Saura and Balsas, 2014 ).

A few studies have compared explicitly the outcomes and dynamics between telephone and in-person qualitative interviews. Irvine and colleagues found that interviews by telephone were somewhat shorter in duration than in-person interviews ( Irvine, 2011 ; Irvine et al., 2013 ). By contrast, other studies found no differences in the length, depth, and type of responses between telephone and in-person interviews ( Sturges and Hanrahan, 2004 ; Sweet, 2002 ; Vogl, 2013 ). In one of the few studies to examine dynamics between interviewer and interviewee, Irvine and colleagues (2013) found that interviewees were more likely to make requests for clarification and to check on the adequacy (specifically the sufficiency and relevance) of their responses during telephone interviews ( Irvine et al., 2013 ). Although studies typically have not investigated interviewee perspectives on their experiences, Sturges and Hanrahan (2004) allowed interviewees to select their mode of interview and followed up with a question about their perception of the choice at the close of the interview. Interviewees were equally positive about their respective interview modes, but telephone interviewees were more likely to comment on privacy as an advantage ( Sturges and Hanrahan, 2004 ).

In addition to the growing body of literature documenting telephone interviews as a viable mode for collecting qualitative data, a few studies draw on case examples to focus more explicitly on “how-to” strategies for successful in-depth telephone interviewing ( Glogowska et al., 2011 ; Musselwhite et al., 2007 ; Smith, 2005 ). In general, these studies emphasize the importance of ensuring that advance communications (such as letters) and initial telephone communications (such as telephone scripts) communicate the purpose of the study and the importance of the participant contribution ( Glogowska et al., 2011 ; Musselwhite et al., 2007 ; Smith, 2005 ). Other important success strategies include scheduling interviews at times convenient to interviewees, establishing rapport through small-talk and reviewing the purpose of the interview ( Glogowska et al., 2011 ), and taking time for pre-interview training and post-interview de-briefing ( Glogowska et al., 2011 ; Smith, 2005 ). Several authors of methodological studies of qualitative telephone interviews caution explicitly against “cold-calls” ( Glogowska et al., 2011 ; Musselwhite et al., 2007 ; Smith, 2005 ). For example, to avoid cold-calls, some studies described establishing rapport and recruiting participants in person, then scheduling a telephone interview at a later date ( Sweet, 2002 ; Sturges and Hanrahan, 2004 ; Musselwhite et al., 2007 ).

Irvine and colleagues (2013) note that there is still a need for methodological studies on qualitative telephone interviews focused on different topics and with interviewees who have different background characteristics. Methodological studies on the population-based National Alcohol Survey in the United States suggest that telephone interviews, like face-to-face interviews, are effective in collecting data about alcohol use, alcohol problems, and other sensitive questions in population-based surveys ( Greenfield et al., 2000 ; Midanik and Greenfield, 2003 ; Midanik et al., 2001 ). However, few studies explore the utility and strategies associated with collecting narrative data by telephone on sensitive topics such as alcohol use, sexuality, and traumatic life-experiences. Because telephone interviews appear to increase a perceived sense of anonymity ( Greenfield et al., 2000 ; Sturges and Hanrahan, 2004 ), they may be well suited to collecting data on sensitive topics ( Trier-Bieniek, 2012 ), but additional studies are needed to verify whether such interviews yield rich data.

In addition, there is a paucity of studies examining the effectiveness of telephone interviews with stigmatized or hard-to-reach populations, an issue that is particularly salient to social work, health, and other applied sciences. One notable exception is the study by Sturges and Hanrahan (2004) , which involved collecting qualitative data from correctional officers and visitors at county jails. The authors noted that “visitors to the jail felt stigmatized by their association with a jail inmate” (p. 114) and that the relative anonymity of the telephone interview reduced anxiety about participating in an interview. Sturges and Hanrahan also emphasized that recruitment of all participants was accomplished face-to-face, and that it was unclear whether another method of sampling would have been effective with hard-to-reach respondents. Another exception is a study by Trier-Bieniek (2012) , who interviewed women over the telephone about their emotional connection to an artist whose music addressed themes such as sexual violence, religious upbringing, and repressed sexuality. Trier-Bieniek found that use of the telephone appeared to create a safe space for participants to share traumatic experiences because of the relative anonymity and opportunity to stay in settings that were comfortable to them during phone interviews. The question of whether telephone interviews are viable with stigmatized or marginalized populations when using recruiting methods other than face-to-face (e.g., Sturges and Hanrahan) or internet social networks (e.g., Trier-Bieniek) is relatively unexplored.

The current study is based on our experience conducting in-depth follow-up interviews with women participants of the population-based National Alcohol Survey, including an oversample of sexual minority women. The aim of this study was twofold: 1) to explore effective interviewer strategies for collection of narrative data on sensitive topics by telephone, and 2) to document challenges and advantages of telephone interviews with a population-based sample, including marginalized populations of women such as sexual minority women.

Research Design

This research was conducted as part of a larger study examining mediators of hazardous drinking among sexual minority women compared to heterosexual women based on the National Alcohol Survey (NAS), a national telephone-based quantitative household probability survey. The term “sexual minority” is increasingly used in research to describe diverse groups who identify as lesbian, bisexual, or whose behavior or attractions are other than exclusively heterosexual ( Mayer et al., 2008 ); we use this term in the current study while noting that it does not reflect the variation in language that individual respondents used to describe their own identities during the interviews. Qualitative in-depth life history interviews were conducted over the telephone with women who were originally recruited as a part of a sample from the 2009–2010 NAS (n=3,825 women). The original quantitative interviews were conducted from 12–24 months prior to the qualitative interview after separate funding was acquired for this study of sexual minority women.

The original NAS probability sample included women who were classified as sexual minorities (identified as lesbian or bisexual and heterosexual-identified women who reported same-sex partners, n=122). The sampling frame for the follow-up interviews, which was designed to generate an oversample of sexual minority women, included all sexual minority women and a matched sample of heterosexual women. The matched heterosexual sample was created by generating list of randomly selected exclusively heterosexual women matched to key characteristics including age, ethnicity, relationship status, education, drinking status in the past year (drinker/none), and a lifetime measure of having consumed five or more drinks at least monthly throughout at least one decade of their life. The lifetime measure was constructed as a dichotomous variable based on responses to questions about how often respondents had five or more drinks on one or more occasions in each decade of their life (i.e., teens, 20’s, 30’s, and 40’s). The lifetime five-plus measure correlated with lifetime alcohol problem and dependence measures, and was assessed as a useful variable for matching respondents with a history of heavier drinking. The list of prospective heterosexual matches was identified as interviews with sexual minority women progressed. We did not plan to have one-to-one matching and this process allowed us to obtain matches for individuals or groups of respondents who shared similar characteristics. For example, one white heterosexual women, aged 50–59, in a partnered relationship and with a high school education, might serve as “match” for three sexual minority women with similar characteristics.

Excluding disconnected/wrong numbers or ineligible respondents, the response rate was 50 percent (48 interviewed, 26 refusals, 5 incomplete interviews, and 17 no response). Approximately 27.9 percent (n=41) were wrong numbers or no longer operative. Two of the individuals initially contacted were men (and not eligible for participation), and seven were mono-lingual Spanish-speaking (interviews were conducted in English). A 50% response rate has been typical for U.S. telephone surveys since the widespread use of caller identification ( Keeter et al., 2006 ). There were no significant differences in final response rates between prospective interviewees who were mailed information in advance compared to those who were contacted solely by telephone.

To assess for nonresponse bias, we conducted several analyses to compare the final interview sample to non-respondents (including 17 sexual minority or heterosexual women who did not respond and 41 wrong or disconnected numbers; n=63) and refusals (who were contacted but declined; n=26). There were no differences in drinking measures (abstaining, drinking, heavier drinking, dependence, alcohol-related consequences, or past treatment) and few demographic differences between the final sample and non-respondents or refusals. No differences were found by ethnicity or relationship status. Non-respondents were generally younger and less educated than interviewees, and refusals were less likely to be employed.

The final sample included 32 sexual minority women (15 lesbians, 10 bisexuals, and 7 women who identified as heterosexual and reported same-sex partners) and 16 matched exclusively heterosexual women. Age of participants ranged from 21 to 67 years of age. Approximately 64.6 percent (n=31) of the participants were White, 22.9 percent (n=11) were African American, and 12.5 percent (n=6) were Latina. Approximately 31.3 percent (n=15) were heavier drinkers at some point in their lives. The original NAS study had an oversample of Blacks and Hispanics thus resulting in slightly disproportionate numbers of minorities, which was considered an advantage. Additional details about the follow-up interview methods are available in published manuscripts about a pilot study ( Condit et al., 2011 ) and analysis of narratives (Drabble and Trocki, 2013).

Prior to initiating telephone calls, a number of efforts were made to facilitate ease of communication with prospective interviewees. Approximately half of the sexual minority women in the original NAS provided a contact address and were mailed notification in advance of the initial telephone contact. The research team created a web page with information about the NAS and the follow-up study. The address of the web page was provided to prospective interviewees in the advance letter. A toll-free number was also established to minimize potential cost barriers for participants in calling with questions or to schedule an interview.

Three members of the research team conducted interviews: one lead investigator with prior experience conducting research based on qualitative interviews and two MSW graduate students. Graduate student researchers received training on skills, attributes, practices, and specific project tools for coordinating and conducting interviews. Students also reviewed pretest interview transcripts; they participated in role-plays; in addition, they discussed personal strengths, experiences and possible preconceived perceptions that they might bring to the research project and the interviews. In this process, students were trained in establishing rapport, minimizing interviewer bias, using probing questions, managing transitions, and determining when they had sufficient information to move to the next question. The senior research team member and students also debriefed after interview sessions to discuss dynamics of the interview, reflect on personal reactions, examine what went well, and identify opportunities for improving future interviews. Preparation for addressing possible distress among respondents included the adoption of a detailed protocol which provided interviewers with tools to recognize and respond to possible signs of distress, identification of local referral resources in advance (based on phone exchanges or zip code), and back-up support from senior research team members (on site) and clinical psychologists (on call) during interview sessions.

Interviews were conducted between March and December of 2011. A semi-structured interview guide was used, which included eight primary questions and follow-up probes related to study participants’ life experiences in several areas including family, friendships, identity, substance use, intimate relationships, trauma, and management of mood. Interviews generally ranged from approximately 45 minutes to 1.5 hours (mean 62.5 minutes). There were no differences in length of interviews between sexual minority and exclusively heterosexual respondents. Each respondent was given a $25 gift card. Interviews were audio taped and transcribed.

For the purposes of this paper, a content analysis of all 48 interviews was conducted to explore strategies employed by interviewers to engage interviewees and obtain rich narrative data. Qualitative data were managed with the assistance of a qualitative software program (NVIVO). Initial open coding to conceptualize, compare, and categorize data was followed by an iterative process to further define and identify connections between categories in the data ( Strauss, 1987 ; Strauss & Corbin, 1990 ). Specifically, two authors read a sample of transcripts and independently developed a list of provisional codes, which were reviewed and refined to use for coding transcripts. This was followed by an iterative process to further refine and use codes for defining and categorizing elements of successful interviews. For the purposes of analysis, success was defined as engagement of respondents from initial contact and throughout the lengthy interview, and respondent willingness to disclose and share their perceptions and experiences in multiple life domains, including personal or potentially sensitive topics. The authors used a consensus model in reviewing, revising, and finalizing categories, as well as in identifying connections between categories to define overarching themes. In addition, a separate review of debriefing notes was conducted to identify “lessons learned” from both planning and implementation phases of the interviews.

Effective Interviewer Strategies: Rapport, Responsiveness, and Regard

Specific strategies for success in interviews emerged in three overarching thematic areas: 1) cultivating rapport and maintaining connection, 2) demonstrating responsiveness to interviewee content, concerns, and 3) communicating regard for the interviewee and her contribution. Themes and specific strategies that emerged in each of these thematic areas are summarized in Table 1 and described with illustrations below.

Themes related to effective interviewer strategies for collection of narrative data through telephone interviews

Cultivating rapport and maintaining connection

This was critical to engaging interviewees and to maintaining a productive interviewer-interviewee relationship. Specific strategies identified in this general area included being friendly and personable through informal conversational exchanges, providing orienting statements to help guide the participants through the interview, and providing occasional reciprocal information.

Informal conversational exchanges

This included small talk before the start of the interview to put the interviewee at ease, friendly conversational exchanges, and the use of humor (light comments, laughter, and joking exchanges). Interviewers would sometimes participate in brief “side conversations,” then guide the respondent back to the interview, creating a balance between naturalness and structure. Some of the informal exchanges were directly related to the content of the interviews. For example, the following interchange occurred in the context of a question about a time that the respondent consumed significantly more alcohol that was typical for her (in this case, the respondent was with friends, who were driving, on her birthday):

Interviewee: …but typically I’m the driver, so I don’t drink, but since it was my birthday Interviewer: But it was your birthday after all <both laugh>. Interviewee: Right, it was my 30th birthday—so I was like, “Well, the hell with that.”

Orienting Statements

These statements were informally woven throughout the interview and commonly used to help participants know what to expect. Orienting statements early in the interview helped to inoculate the interviewee against feeling unheard when questions were redundant, illustrated by the following interviewer statement: “ Okay, and I’m real sorry if this sounds redundant, it’s the nature of the beast here, I’m asking questions that may sound similar, but they’re kind of different, they have different nuances .” Later in the interview, orienting statements helped reinforce interviewee participation when interview fatigue might otherwise become an issue, such as: “ So, we’re just about done and—again, I want to thank you for your patience—I’m going to ask a few final questions .” Orienting statements included giving permission to the interviewee to add information at any time: “ At any point, if you want to add anything else that you think you want me to know, might be important to the study or anything, you’re certainly welcome to do that too, okay?” Sometimes statements reinforced interviewee rights to exercise control during the interview, illustrated by the exchange below:

Interviewer: Okay. I’m going to move onto the substance use theme, and, of course, you just talked to me rather extensively about your alcohol experience. I’m going to go ahead and ask the question. Interviewee: Okay. <laughs> Am I allowed to say I already answered it? Interviewer: You certainly are. Interviewee: Okay. <both laugh> Well, maybe I’ll even expound.

Reciprocity

This involved interviewers giving back to interviewees by briefly sharing personal information pertinent to the topic in order to validate or encourage interviewees. For example, the human subjects protocol included procedures for checking in with clients about their level of distress; one interviewer made this check-in less intrusive through her personal disclosure: “ I lost both my parents and I still get very emotional and so I’m not saying you’re doing anything wrong, it’s perfectly fine with me, I just want to make sure you’re okay.” Interviewers sometimes included informal comments about their own enthusiasm about the research project. In debriefing, one interviewer commented: “ My excitement seemed to increase their excitement of being a part of such an important project.”

Demonstrating responsiveness to interviewee content and concerns

These strategies were also important to create a safe and empathetic interview environment. Specific strategies in this area included active listening, supportive vocalizations, and validation and clarification exchanges.

Active listening

This strategy included using of reflective and summary statements as well as follow-up questions specific to interviewee content. For example, the following reflective statement was followed by an interviewee-specific probe: “ You mentioned it was about six months that you were really having a rough time. What did you do to cope during that period?” Although interviewers were not able to respond to visual cues, there were instances where it was possible to respond to both narrative content and tone of voice. For example, one interviewer noted, “ I detect something in your tone ,” which prompted the interviewee to elaborate in detail about conflicts with a family member.

Supportive vocalizations

These vocalizations included encouraging tones, encouraging words, and non-language encouragement such as the following: “sure,” “right,” “yeah,” “I know what you mean,” “mm-hmm,” “wow,” “okay” “I see,” and “interesting.”

Validation and clarification exchanges

These exchanges involved the interviewer checking to ensure accuracy and understanding, responding to interviewee requests for clarification about questions, and reassuring interviewees about the content and quality of their responses. The following exchange typified this interaction—Interviewee: “ Am I being to lengthy ?” Interviewer: “ No, absolutely not. I’m enjoying listening to you .” Interviewees also expressed insecurity about whether the content of their narrative was valuable, such as, “ I don’t know if that answers your question or not ,” or “ I don’t know if I’m answering this very well ,” which prompted reassuring comments from interviewers such as, “ There are no wrong answers you can give me ” or “ You’re doing just fine .”

Communicating regard for the interviewee and her contribution

This involved acknowledgement of disclosure and statements of appreciation . For example, interviewers frequently expressed appreciation for disclosure of personal information, particularly in response to sensitive questions, exemplified by the following exchange:

Interviewer: Thank you very much for sharing that with me. I know that’s very personal, and it can be hard to share with someone on the phone, a stranger, but I want to thank you for being open and sharing that information with me. Interviewee: It’s really easier with a stranger than it is with someone that you know.

Interviewers also demonstrated respectful attention by maintaining an accepting, non-judgmental tone. Respect and positive regard were often communicated through simple affirming statements. This is illustrated by an exchange with one young sexual minority respondent during her response to questions about identity:

Interviewee: I mean, a couple of months ago I had pink hair in (names rural state). Nobody has pink hair in (state). Interviewer: That was pretty bold, huh? Interviewee: Exactly, but I liked it, and I do what I like….

It was notable that interviewees often expressed appreciation for “feeling heard” toward the end of the interview or otherwise commented about what they were getting out of participating in the study. For example, one interviewee commented, “Well, my experiences would not help anyone if I did not share them. And since you called and asked for it, I was more than glad to help you with it.” Upon being given gift certificate information at the end of the interview, another interviewee noted: “Oh yeah, I forgot all about that. That’s not why I was doing this—I would have done it anyway.”

Advantages, Challenges, and “Lessons Learned” for Addressing Challenges

The ability to conduct interviews across geographically disparate interviewees in the U.S. was a critical advantage for the purposes of our study. It would not have been feasible, in term of cost or logistics, to conduct follow-up interviews with a sub-sample of former respondents of a national sample through in-person interviews. The use of the telephone proved to maximize flexibility for interviewee scheduling and re-scheduling interviews. The telephone mode also made it possible for interviewees to schedule interviews at times that suited them and, in several cases, re-schedule. Some interviewees missed or were “late” to interview appointments, and research team members were able to reschedule. In addition to logistical advantages, it appeared that interviewees were comfortable creating privacy for their interview call and were open to providing details about their life experiences over the telephone. For example, one interviewee asked to skip a question and then, when the interviewer later asked if she was willing to answer the question (related to past trauma), the interviewee explained that her boyfriend had been in the room earlier and she postponed answering until he left.

The research team anticipated challenges in recruiting interviews given a lapse in time between the initial NAS interview and the follow-up calls (approximately 1–2 years) and the necessity for making “cold calls” in cases where mailing addresses were not available for sending advance notification. Other challenges included establishing rapport over the telephone and scheduling interviews in the context of a small research team with limited hours for scheduling interviews. Through debriefing, the team identified a number of “lessons learned” for addressing or minimizing challenges, which included the following: substantial pre-interview preparation, training, de-briefing, and effective use of relational skills.

Pre-interview preparation

Lessons learned from the debriefing include the following:

- In the absence of opportunities for face-to-face participant recruitment, options for communicating with participants in advance were critical. Specific strategies employed by the team and deemed helpful in retrospect included the following: developing telephone introductory and message scripts, sending introductory letters (by mail or email) to prospective interviewees for whom address information was available, establishing toll-free numbers for call-backs to minimize possible cost barriers for respondents returning calls from land-lines or from work, and creating a project web-page that prospective interviewees could visit to learn about the project and verify the legitimacy of the project,.

- Communication about designated blocks of time for interviews was more important than having mechanisms for access at any time. We initially put substantial effort into identifying a way to forward calls to project-specific cells phones to avoid losing opportunities to arrange interviews when respondents called back (as it was not feasible to support full time staffing). Interviewees frequently (and to the initial surprise of the researchers) agreed to be interviewed at the time that they answered the telephone. It is worth noting that the scripts for leaving telephone messages allowed the research team to mention the next windows in which calls would be made (typically on one or two weekday evenings and Saturdays). Participants may have already deliberated about their willingness to participate and, as such, simply answered the phone when they were inclined to be interviewed.