- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Problem-Solving Therapy?

Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ArlinCuncic_1000-21af8749d2144aa0b0491c29319591c4.jpg)

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

Verywell / Madelyn Goodnight

Problem-Solving Therapy Techniques

How effective is problem-solving therapy, things to consider, how to get started.

Problem-solving therapy is a brief intervention that provides people with the tools they need to identify and solve problems that arise from big and small life stressors. It aims to improve your overall quality of life and reduce the negative impact of psychological and physical illness.

Problem-solving therapy can be used to treat depression , among other conditions. It can be administered by a doctor or mental health professional and may be combined with other treatment approaches.

At a Glance

Problem-solving therapy is a short-term treatment used to help people who are experiencing depression, stress, PTSD, self-harm, suicidal ideation, and other mental health problems develop the tools they need to deal with challenges. This approach teaches people to identify problems, generate solutions, and implement those solutions. Let's take a closer look at how problem-solving therapy can help people be more resilient and adaptive in the face of stress.

Problem-solving therapy is based on a model that takes into account the importance of real-life problem-solving. In other words, the key to managing the impact of stressful life events is to know how to address issues as they arise. Problem-solving therapy is very practical in its approach and is only concerned with the present, rather than delving into your past.

This form of therapy can take place one-on-one or in a group format and may be offered in person or online via telehealth . Sessions can be anywhere from 30 minutes to two hours long.

Key Components

There are two major components that make up the problem-solving therapy framework:

- Applying a positive problem-solving orientation to your life

- Using problem-solving skills

A positive problem-solving orientation means viewing things in an optimistic light, embracing self-efficacy , and accepting the idea that problems are a normal part of life. Problem-solving skills are behaviors that you can rely on to help you navigate conflict, even during times of stress. This includes skills like:

- Knowing how to identify a problem

- Defining the problem in a helpful way

- Trying to understand the problem more deeply

- Setting goals related to the problem

- Generating alternative, creative solutions to the problem

- Choosing the best course of action

- Implementing the choice you have made

- Evaluating the outcome to determine next steps

Problem-solving therapy is all about training you to become adaptive in your life so that you will start to see problems as challenges to be solved instead of insurmountable obstacles. It also means that you will recognize the action that is required to engage in effective problem-solving techniques.

Planful Problem-Solving

One problem-solving technique, called planful problem-solving, involves following a series of steps to fix issues in a healthy, constructive way:

- Problem definition and formulation : This step involves identifying the real-life problem that needs to be solved and formulating it in a way that allows you to generate potential solutions.

- Generation of alternative solutions : This stage involves coming up with various potential solutions to the problem at hand. The goal in this step is to brainstorm options to creatively address the life stressor in ways that you may not have previously considered.

- Decision-making strategies : This stage involves discussing different strategies for making decisions as well as identifying obstacles that may get in the way of solving the problem at hand.

- Solution implementation and verification : This stage involves implementing a chosen solution and then verifying whether it was effective in addressing the problem.

Other Techniques

Other techniques your therapist may go over include:

- Problem-solving multitasking , which helps you learn to think clearly and solve problems effectively even during times of stress

- Stop, slow down, think, and act (SSTA) , which is meant to encourage you to become more emotionally mindful when faced with conflict

- Healthy thinking and imagery , which teaches you how to embrace more positive self-talk while problem-solving

What Problem-Solving Therapy Can Help With

Problem-solving therapy addresses life stress issues and focuses on helping you find solutions to concrete issues. This approach can be applied to problems associated with various psychological and physiological symptoms.

Mental Health Issues

Problem-solving therapy may help address mental health issues, like:

- Chronic stress due to accumulating minor issues

- Complications associated with traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- Emotional distress

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Problems associated with a chronic disease like cancer, heart disease, or diabetes

- Self-harm and feelings of hopelessness

- Substance use

- Suicidal ideation

Specific Life Challenges

This form of therapy is also helpful for dealing with specific life problems, such as:

- Death of a loved one

- Dissatisfaction at work

- Everyday life stressors

- Family problems

- Financial difficulties

- Relationship conflicts

Your doctor or mental healthcare professional will be able to advise whether problem-solving therapy could be helpful for your particular issue. In general, if you are struggling with specific, concrete problems that you are having trouble finding solutions for, problem-solving therapy could be helpful for you.

Benefits of Problem-Solving Therapy

The skills learned in problem-solving therapy can be helpful for managing all areas of your life. These can include:

- Being able to identify which stressors trigger your negative emotions (e.g., sadness, anger)

- Confidence that you can handle problems that you face

- Having a systematic approach on how to deal with life's problems

- Having a toolbox of strategies to solve the issues you face

- Increased confidence to find creative solutions

- Knowing how to identify which barriers will impede your progress

- Knowing how to manage emotions when they arise

- Reduced avoidance and increased action-taking

- The ability to accept life problems that can't be solved

- The ability to make effective decisions

- The development of patience (realizing that not all problems have a "quick fix")

Problem-solving therapy can help people feel more empowered to deal with the problems they face in their lives. Rather than feeling overwhelmed when stressors begin to take a toll, this therapy introduces new coping skills that can boost self-efficacy and resilience .

Other Types of Therapy

Other similar types of therapy include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) . While these therapies work to change thinking and behaviors, they work a bit differently. Both CBT and SFBT are less structured than problem-solving therapy and may focus on broader issues. CBT focuses on identifying and changing maladaptive thoughts, and SFBT works to help people look for solutions and build self-efficacy based on strengths.

This form of therapy was initially developed to help people combat stress through effective problem-solving, and it was later adapted to address clinical depression specifically. Today, much of the research on problem-solving therapy deals with its effectiveness in treating depression.

Problem-solving therapy has been shown to help depression in:

- Older adults

- People coping with serious illnesses like cancer

Problem-solving therapy also appears to be effective as a brief treatment for depression, offering benefits in as little as six to eight sessions with a therapist or another healthcare professional. This may make it a good option for someone unable to commit to a lengthier treatment for depression.

Problem-solving therapy is not a good fit for everyone. It may not be effective at addressing issues that don't have clear solutions, like seeking meaning or purpose in life. Problem-solving therapy is also intended to treat specific problems, not general habits or thought patterns .

In general, it's also important to remember that problem-solving therapy is not a primary treatment for mental disorders. If you are living with the symptoms of a serious mental illness such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia , you may need additional treatment with evidence-based approaches for your particular concern.

Problem-solving therapy is best aimed at someone who has a mental or physical issue that is being treated separately, but who also has life issues that go along with that problem that has yet to be addressed.

For example, it could help if you can't clean your house or pay your bills because of your depression, or if a cancer diagnosis is interfering with your quality of life.

Your doctor may be able to recommend therapists in your area who utilize this approach, or they may offer it themselves as part of their practice. You can also search for a problem-solving therapist with help from the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Society of Clinical Psychology .

If receiving problem-solving therapy from a doctor or mental healthcare professional is not an option for you, you could also consider implementing it as a self-help strategy using a workbook designed to help you learn problem-solving skills on your own.

During your first session, your therapist may spend some time explaining their process and approach. They may ask you to identify the problem you’re currently facing, and they’ll likely discuss your goals for therapy .

Keep In Mind

Problem-solving therapy may be a short-term intervention that's focused on solving a specific issue in your life. If you need further help with something more pervasive, it can also become a longer-term treatment option.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Shang P, Cao X, You S, Feng X, Li N, Jia Y. Problem-solving therapy for major depressive disorders in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials . Aging Clin Exp Res . 2021;33(6):1465-1475. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01672-3

Cuijpers P, Wit L de, Kleiboer A, Karyotaki E, Ebert DD. Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: An updated meta-analysis . Eur Psychiatry . 2018;48(1):27-37. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.11.006

Nezu AM, Nezu CM, D'Zurilla TJ. Problem-Solving Therapy: A Treatment Manual . New York; 2013. doi:10.1891/9780826109415.0001

Owens D, Wright-Hughes A, Graham L, et al. Problem-solving therapy rather than treatment as usual for adults after self-harm: a pragmatic, feasibility, randomised controlled trial (the MIDSHIPS trial) . Pilot Feasibility Stud . 2020;6:119. doi:10.1186/s40814-020-00668-0

Sorsdahl K, Stein DJ, Corrigall J, et al. The efficacy of a blended motivational interviewing and problem solving therapy intervention to reduce substance use among patients presenting for emergency services in South Africa: A randomized controlled trial . Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy . 2015;10(1):46. doi:doi.org/10.1186/s13011-015-0042-1

Margolis SA, Osborne P, Gonzalez JS. Problem solving . In: Gellman MD, ed. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine . Springer International Publishing; 2020:1745-1747. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-39903-0_208

Kirkham JG, Choi N, Seitz DP. Meta-analysis of problem solving therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder in older adults . Int J Geriatr Psychiatry . 2016;31(5):526-535. doi:10.1002/gps.4358

Garand L, Rinaldo DE, Alberth MM, et al. Effects of problem solving therapy on mental health outcomes in family caregivers of persons with a new diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia: A randomized controlled trial . Am J Geriatr Psychiatry . 2014;22(8):771-781. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.07.007

Noyes K, Zapf AL, Depner RM, et al. Problem-solving skills training in adult cancer survivors: Bright IDEAS-AC pilot study . Cancer Treat Res Commun . 2022;31:100552. doi:10.1016/j.ctarc.2022.100552

Albert SM, King J, Anderson S, et al. Depression agency-based collaborative: effect of problem-solving therapy on risk of common mental disorders in older adults with home care needs . The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry . 2019;27(6):619-624. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.01.002

By Arlin Cuncic, MA Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Solving problems the cognitive-behavioral way, problem solving is another part of behavioral therapy..

Posted February 2, 2022 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?

- Find a therapist who practices CBT

- Problem-solving is one technique used on the behavioral side of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

- The problem-solving technique is an iterative, five-step process that requires one to identify the problem and test different solutions.

- The technique differs from ad-hoc problem-solving in its suspension of judgment and evaluation of each solution.

As I have mentioned in previous posts, cognitive behavioral therapy is more than challenging negative, automatic thoughts. There is a whole behavioral piece of this therapy that focuses on what people do and how to change their actions to support their mental health. In this post, I’ll talk about the problem-solving technique from cognitive behavioral therapy and what makes it unique.

The problem-solving technique

While there are many different variations of this technique, I am going to describe the version I typically use, and which includes the main components of the technique:

The first step is to clearly define the problem. Sometimes, this includes answering a series of questions to make sure the problem is described in detail. Sometimes, the client is able to define the problem pretty clearly on their own. Sometimes, a discussion is needed to clearly outline the problem.

The next step is generating solutions without judgment. The "without judgment" part is crucial: Often when people are solving problems on their own, they will reject each potential solution as soon as they or someone else suggests it. This can lead to feeling helpless and also discarding solutions that would work.

The third step is evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of each solution. This is the step where judgment comes back.

Fourth, the client picks the most feasible solution that is most likely to work and they try it out.

The fifth step is evaluating whether the chosen solution worked, and if not, going back to step two or three to find another option. For step five, enough time has to pass for the solution to have made a difference.

This process is iterative, meaning the client and therapist always go back to the beginning to make sure the problem is resolved and if not, identify what needs to change.

Advantages of the problem-solving technique

The problem-solving technique might differ from ad hoc problem-solving in several ways. The most obvious is the suspension of judgment when coming up with solutions. We sometimes need to withhold judgment and see the solution (or problem) from a different perspective. Deliberately deciding not to judge solutions until later can help trigger that mindset change.

Another difference is the explicit evaluation of whether the solution worked. When people usually try to solve problems, they don’t go back and check whether the solution worked. It’s only if something goes very wrong that they try again. The problem-solving technique specifically includes evaluating the solution.

Lastly, the problem-solving technique starts with a specific definition of the problem instead of just jumping to solutions. To figure out where you are going, you have to know where you are.

One benefit of the cognitive behavioral therapy approach is the behavioral side. The behavioral part of therapy is a wide umbrella that includes problem-solving techniques among other techniques. Accessing multiple techniques means one is more likely to address the client’s main concern.

Salene M. W. Jones, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist in Washington State.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Problem solving therapy - use and effectiveness in general practice

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Rural Health, Rural Health Academic Centre, the University of Melbourne, Ballarat, Victoria, Australia. [email protected]

- PMID: 22962642

Background: Problem solving therapy (PST) is one of the focused psychological strategies supported by Medicare for use by appropriately trained general practitioners.

Objective: This article reviews the evidence base for PST and its use in the general practice setting.

Discussion: Problem solving therapy involves patients learning or reactivating problem solving skills. These skills can then be applied to specific life problems associated with psychological and somatic symptoms. Problem solving therapy is suitable for use in general practice for patients experiencing common mental health conditions and has been shown to be as effective in the treatment of depression as antidepressants. Problem solving therapy involves a series of sequential stages. The clinician assists the patient to develop new empowering skills, and then supports them to work through the stages of therapy to determine and implement the solution selected by the patient. Many experienced GPs will identify their own existing problem solving skills. Learning about PST may involve refining and focusing these skills.

- General Practice / methods*

- National Health Programs

- Problem Solving*

- Psychotherapy / methods*

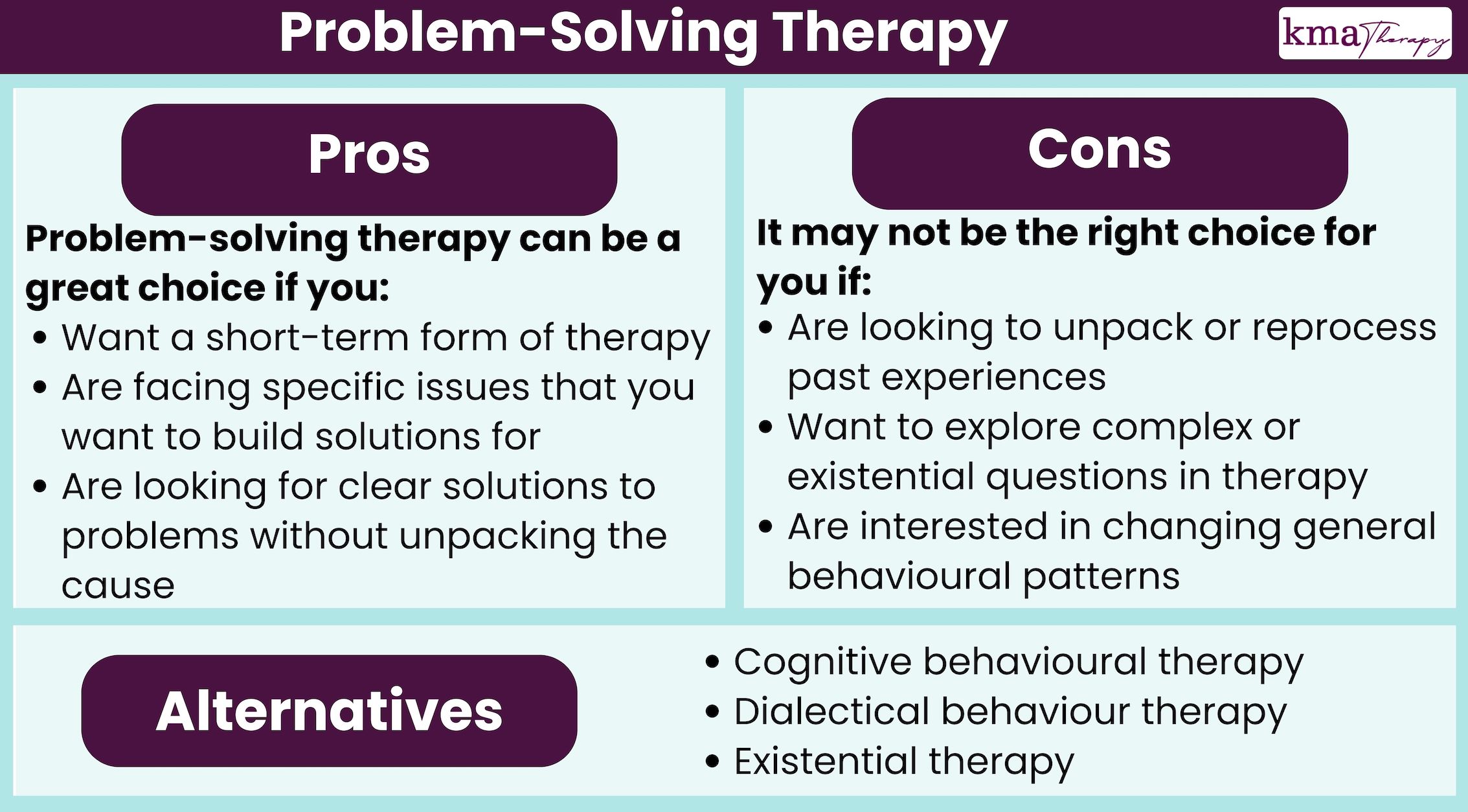

What is Problem-Solving Therapy? (The Pros and Cons)

When you’re navigating a difficult situation, it can feel like problems keep piling up. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed and discouraged when you can’t seem to find a solution to any of them.

Fortunately, problem-solving therapy can be a short-term, effective way to find the answers you need.

Here at KMA Therapy, we know that choosing a type of therapy should be the least of your problems. We’re passionate about educating our clients and community about the different types of therapy available, and how to know which ones could be a great choice for them.

After reading this article, you’ll know what problem-solving therapy is, what happens during problem-solving therapy, and its pros and cons.

What is Problem-Solving Therapy?

Problem-solving therapy is a short-form treatment that usually lasts between four and twelve sessions.

It is most frequently used to treat depression, with a primary focus on helping you build the tools needed to identify and solve problems.

The main goal of problem-solving therapy is to improve your overall quality of life by helping you reduce the impact of stressors and problems you’re facing.

Problem-solving therapy is used to treat:

- Suicidal ideation

- Self-harm behaviours

If you’re experiencing suicidal ideation or are having thoughts of harming yourself, you can connect with Talk Suicide Canada for immediate support.

What Happens During Problem-Solving Therapy?

During problem-solving therapy, your therapist will focus on two main components.

1. Positive problem-solving framework

Positive problem-solving involves creating a framework that allows you to view things in a positive way by allowing yourself to feel confident and capable when handling your problems.

This means figuring out how to accept that you’ll still face problems in your life, while feeling more sure about your ability to face, address, and overcome them.

2. Planful problem-solving

Planful problem-solving involves four steps that help you learn how to solve problems in a healthy way:

- Defining the problem that you need to solve in a way where potential solutions can be created

- Exploring alternative solutions to the problem you’re facing by listing as many creative solutions to your problem as you can

- Discussing decision-making strategies to help you know which solution to choose and how to adapt to overcome obstacles

- Implementing your solution for your problem and assessing whether it was the right choice

What are the Pros of Problem-Solving Therapy?

Problem-solving therapy is an effective and helpful form of therapy that can help you see meaningful changes in your life in a short amount of time.

Problem-solving therapy may be a great choice for you if:

- You want a short-term form of therapy

- You’re facing specific issues that you want to build solutions for

- You’re looking for clear solutions to problems without unpacking the cause

In general, problem-solving therapy is a great choice if there’s something specific in your life that’s causing additional problems.

For example, if you’re struggling with depression that makes you unable to keep in touch with loved ones or stay on top of your bills, problem-solving therapy can be a great choice to help you find solutions that work for these specific issues.

However, if you’re struggling to find the motivation to get out of bed in the morning because you want a deeper sense of purpose in your life, another form of therapy might be a better choice.

What are the Cons of Problem-Solving Therapy?

While problem-solving therapy can be quick, effective, and empowering, it’s not always the best choice if you’re interested in more in-depth conversations in therapy.

Problem-solving therapy may not be the right fit if you:

- Are looking to unpack or reprocess past experiences

- Want to explore complex or existential questions in therapy

- Are interested in changing general behavioural patterns (rather than specific problems)

Alternatives to Problem-Solving Therapy

After learning about the pros and cons of problem-solving therapy, you may be interested in some alternative forms of therapy to explore.

Alternatives to problem-solving therapy include:

- Existential therapy , which allows you to explore your sense of purpose and meaning in life

- Cognitive behavioural therapy , which focuses on helping you restructure your thought and behaviour patterns

- Dialectical behaviour therapy, which helps you build skills to change and solve problems, with an additional focus on mindfulness and relationships

Next Steps for Beginning Therapy

After reading this article, you know what problem-solving therapy is and how to know if it’s the right choice for you.

Here at KMA Therapy, our passionate team of therapists has been supporting our clients with tailored therapy plans for over 15 years.

You don’t have to know exactly what type of therapy you want to pursue when you meet a therapist for the first time, so don’t worry if you’re feeling overwhelmed.

It’s helpful to have a sense of what you like and dislike, and what types of therapy sound interesting to you - but your therapist will help you choose what will work best and create a treatment plan customized to you.

Register online for more information or download our free Therapy 101 Guide to learn more.

If you’d prefer to keep reading, explore these articles we’ve chosen for you:

- What is Psychodynamic Therapy? (The Pros and Cons)

- Therapy 101: The Ultimate Guide to Beginning Therapy

- What is a Therapy Introductory Session?

Register Online

What is systemic therapy (the pros and cons).

Our team of experts will support you throughout your mental health journey to help you become your most authentic self!

What’s the Difference Between Anxiety and Depression?

Are situationships good or bad 3 experts weigh in, or, are you all set and ready to book, ontario's premier counselling practice.

What is Solution-Focused Therapy: 3 Essential Techniques

You’re at an important business meeting, and you’re there to discuss some problems your company is having with its production.

At the meeting, you explain what’s causing the problems: The widget-producing machine your company uses is getting old and slowing down. The machine is made up of hundreds of small parts that work in concert, and it would be much more expensive to replace each of these old, worn-down parts than to buy a new widget-producing machine.

You are hoping to convey to the other meeting attendees the impact of the problem, and the importance of buying a new widget-producing machine. You give a comprehensive overview of the problem and how it is impacting production.

One meeting attendee asks, “So which part of the machine, exactly, is getting worn down?” Another says, “Please explain in detail how our widget-producing machine works.” Yet another asks, “How does the new machine improve upon each of the components of the machine?” A fourth attendee asks, “Why is it getting worn down? We should discuss how the machine was made in order to fully understand why it is wearing down now.”

You are probably starting to feel frustrated that your colleagues’ questions don’t address the real issue. You might be thinking, “What does it matter how the machine got worn down when buying a new one would fix the problem?” In this scenario, it is much more important to buy a new widget-producing machine than it is to understand why machinery wears down over time.

When we’re seeking solutions, it’s not always helpful to get bogged down in the details. We want results, not a narrative about how or why things became the way they are.

This is the idea behind solution-focused therapy . For many people, it is often more important to find solutions than it is to analyze the problem in great detail. This article will cover what solution-focused therapy is, how it’s applied, and what its limitations are.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is solution-focused therapy, theory behind the solution-focused approach, solution-focused model, popular techniques and interventions, sfbt treatment plan: an example, technologies to execute an sfbt treatment plan (incl. quenza), limitations of sfbt counseling, what does sfbt have to do with positive psychology, a take-home message.

Solution-focused therapy, also called solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT), is a type of therapy that places far more importance on discussing solutions than problems (Berg, n.d.). Of course, you must discuss the problem to find a solution, but beyond understanding what the problem is and deciding how to address it, solution-focused therapy will not dwell on every detail of the problem you are experiencing.

Solution-focused brief therapy doesn’t require a deep dive into your childhood and the ways in which your past has influenced your present. Instead, it will root your sessions firmly in the present while working toward a future in which your current problems have less of an impact on your life (Iveson, 2002).

This solution-centric form of therapy grew out of the field of family therapy in the 1980s. Creators Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg noticed that most therapy sessions were spent discussing symptoms, issues, and problems.

De Shazer and Berg saw an opportunity for quicker relief from negative symptoms in a new form of therapy that emphasized quick, specific problem-solving rather than an ongoing discussion of the problem itself.

The word “brief” in solution-focused brief therapy is key. The goal of SFBT is to find and implement a solution to the problem or problems as soon as possible to minimize time spent in therapy and, more importantly, time spent struggling or suffering (Antin, 2018).

SFBT is committed to finding realistic, workable solutions for clients as quickly as possible, and the efficacy of this treatment has influenced its spread around the world and use in multiple contexts.

SFBT has been successfully applied in individual, couples, and family therapy. The problems it can address are wide-ranging, from the normal stressors of life to high-impact life events.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

The solution-focused approach of SFBT is founded in de Shazer and Berg’s idea that the solutions to one’s problems are typically found in the “exceptions” to the problem, meaning the times when the problem is not actively affecting the individual (Iveson, 2002).

This approach is a logical one—to find a lasting solution to a problem, it is rational to look first at those times in which the problem lacks its usual potency.

For example, if a client is struggling with excruciating shyness, but typically has no trouble speaking to his or her coworkers, a solution-focused therapist would target the client’s interactions at work as an exception to the client’s usual shyness. Once the client and therapist have discovered an exception, they will work as a team to find out how the exception is different from the client’s usual experiences with the problem.

The therapist will help the client formulate a solution based on what sets the exception scenario apart, and aid the client in setting goals and implementing the solution.

You may have noticed that this type of therapy relies heavily on the therapist and client working together. Indeed, SFBT works on the assumption that every individual has at least some level of motivation to address their problem or problems and to find solutions that improve their quality of life .

This motivation on the part of the client is an essential piece of the model that drives SFBT (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

Solution-focused theorists and therapists believe that generally, people develop default problem patterns based on their experiences, as well as default solution patterns.

These patterns dictate an individual’s usual way of experiencing a problem and his or her usual way of coping with problems (Focus on Solutions, 2013).

The solution-focused model holds that focusing only on problems is not an effective way of solving them. Instead, SFBT targets clients’ default solution patterns, evaluates them for efficacy, and modifies or replaces them with problem-solving approaches that work (Focus on Solutions, 2013).

In addition to this foundational belief, the SFBT model is based on the following assumptions:

- Change is constant and certain;

- Emphasis should be on what is changeable and possible;

- Clients must want to change;

- Clients are the experts in therapy and must develop their own goals;

- Clients already have the resources and strengths to solve their problems;

- Therapy is short-term;

- The focus must be on the future—a client’s history is not a key part of this type of therapy (Counselling Directory, 2017).

Based on these assumptions, the model instructs therapists to do the following in their sessions with clients:

- Ask questions rather than “selling” answers;

- Notice and reinforce evidence of the client’s positive qualities, strengths, resources, and general competence to solve their own problems;

- Work with what people can do rather than focusing on what they can’t do;

- Pinpoint the behaviors a client is already engaging in that are helpful and effective and find new ways to facilitate problem-solving through these behaviors;

- Focus on the details of the solution instead of the problem;

- Develop action plans that work for the client (Focus on Solutions, 2013).

SFBT therapists aim to bring out the skills, strengths, and abilities that clients already possess rather than attempting to build new competencies from scratch. This assumption of a client’s competence is one of the reasons this therapy can be administered in a short timeframe—it is much quicker to harness the resources clients already have than to create and nurture new resources.

Beyond these basic activities, there are many techniques and exercises used in SFBT to promote problem-solving and enhance clients’ ability to work through their own problems.

Working with a therapist is generally recommended when you are facing overwhelming or particularly difficult problems, but not all problems require a licensed professional to solve.

For each technique listed below, it will be noted if it can be used as a standalone technique.

Asking good questions is vital in any form of therapy, but SFBT formalized this practice into a technique that specifies a certain set of questions intended to provoke thinking and discussion about goal-setting and problem-solving.

One such question is the “coping question.” This question is intended to help clients recognize their own resiliency and identify some of the ways in which they already cope with their problems effectively.

There are many ways to phrase this sort of question, but generally, a coping question is worded something like, “How do you manage, in the face of such difficulty, to fulfill your daily obligations?” (Antin, 2018).

Another type of question common in SFBT is the “miracle question.” The miracle question encourages clients to imagine a future in which their problems are no longer affecting their lives. Imagining this desired future will help clients see a path forward, both allowing them to believe in the possibility of this future and helping them to identify concrete steps they can take to make it happen.

This question is generally asked in the following manner: “Imagine that a miracle has occurred. This problem you are struggling with is suddenly absent from your life. What does your life look like without this problem?” (Antin, 2018).

If the miracle question is unlikely to work, or if the client is having trouble imagining this miracle future, the SFBT therapist can use “best hopes” questions instead. The client’s answers to these questions will help establish what the client is hoping to achieve and help him or her set realistic and achievable goals.

The “best hopes” questions can include the following:

- What are your best hopes for today’s session?

- What needs to happen in this session to enable you to leave thinking it was worthwhile?

- How will you know things are “good enough” for our sessions to end?

- What needs to happen in these sessions so that your relatives/friends/coworkers can say, “I’m really glad you went to see [the therapist]”? (Vinnicombe, n.d.).

To identify the exceptions to the problems plaguing clients, therapists will ask “exception questions.” These are questions that ask about clients’ experiences both with and without their problems. This helps to distinguish between circumstances in which the problems are most active and the circumstances in which the problems either hold no power or have diminished power over clients’ moods or thoughts.

Exception questions can include:

- Tell me about the times when you felt the happiest;

- What was it about that day that made it a better day?

- Can you think of times when the problem was not present in your life? (Counselling Directory, 2017).

Another question frequently used by SFBT practitioners is the “scaling question.”

It asks clients to rate their experiences (such as how their problems are currently affecting them, how confident they are in their treatment, and how they think the treatment is progressing) on a scale from 0 (lowest) to 10 (highest). This helps the therapist to gauge progress and learn more about clients’ motivation and confidence in finding a solution.

For example, an SFBT therapist may ask, “On a scale from 0 to 10, how would you rate your progress in finding and implementing a solution to your problem?” (Antin, 2018).

Do One Thing Different

This exercise can be completed individually, but the handout may need to be modified for adult or adolescent users.

This exercise is intended to help the client or individual to learn how to break his or her problem patterns and build strategies to simply make things go better.

The handout breaks the exercise into the following steps (Coffen, n.d.):

- Think about the things you do in a problem situation. Change any part you can. Choose to change one thing, such as the timing, your body patterns (what you do with your body), what you say, the location, or the order in which you do things;

- Think of a time that things did not go well for you. When does that happen? What part of that problem situation will you do differently now?

- Think of something done by somebody else does that makes the problem better. Try doing what they do the next time the problem comes up. Or, think of something that you have done in the past that made things go better. Try doing that the next time the problem comes up;

- Think of something that somebody else does that works to make things go better. What is the person’s name and what do they do that you will try?

- Think of something that you have done in the past that helped make things go better. What did you do that you will do next time?

- Feelings tell you that you need to do something. Your brain tells you what to do. Understand what your feelings are but do not let them determine your actions. Let your brain determine the actions;

- Feelings are great advisors but poor masters (advisors give information and help you know what you could do; masters don’t give you choices);

- Think of a feeling that used to get you into trouble. What feeling do you want to stop getting you into trouble?

- Think of what information that feeling is telling you. What does the feeling suggest you should do that would help things go better?

- Change what you focus on. What you pay attention to will become bigger in your life and you will notice it more and more. To solve a problem, try changing your focus or your perspective.

- Think of something that you are focusing on too much. What gets you into trouble when you focus on it?

- Think of something that you will focus on instead. What will you focus on that will not get you into trouble?

- Imagine a time in the future when you aren’t having the problem you are having right now. Work backward to figure out what you could do now to make that future come true;

- Think of what will be different for you in the future when things are going better;

- Think of one thing that you would be doing differently before things could go better in the future. What one thing will you do differently?

- Sometimes people with problems talk about how other people cause those problems and why it’s impossible to do better. Change your story. Talk about times when the problem was not happening and what you were doing at that time. Control what you can control. You can’t control other people, but you can change your actions, and that might change what other people do;

- Think of a time when you were not having the problem that is bothering you. Talk about that time.

- If you believe in a god or a higher power, focus on God to get things to go better. When you are focused on God or you are asking God to help you, things might go better for you.

- Do you believe in a god or a higher power? Talk about how you will seek help from your god to make things go better.

- Use action talk to get things to go better. Action talk sticks to the facts, addresses only the things you can see, and doesn’t address what you believe another person was thinking or feeling—we have no way of knowing that for sure. When you make a complaint, talk about the action that you do not like. When you make a request, talk about what action you want the person to do. When you praise someone, talk about what action you liked;

- Make a complaint about someone cheating at a game using action talk;

- Make a request for someone to play fairly using action talk;

- Thank someone for doing what you asked using action talk.

Following these eight steps and answering the questions thoughtfully will help people recognize their strengths and resources, identify ways in which they can overcome problems, plan and set goals to address problems, and practice useful skills.

While this handout can be extremely effective for SFBT, it can also be used in other therapies or circumstances.

To see this handout and download it for you or your clients, click here .

Presupposing Change

The “presupposing change” technique has great potential in SFBT, in part because when people are experiencing problems, they have a tendency to focus on the problems and ignore the positive changes in their life.

It can be difficult to recognize the good things happening in your life when you are struggling with a painful or particularly troublesome problem.

This technique is intended to help clients be attentive to the positive things in their lives, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant. Any positive change or tiny step of progress should be noted, so clients can both celebrate their wins and draw from past wins to facilitate future wins.

Presupposing change is a strikingly simple technique to use: Ask questions that assume positive changes. This can include questions like, “What’s different or better since I saw you last time?”

If clients are struggling to come up with evidence of positive change or are convinced that there has been no positive change, the therapist can ask questions that encourage clients to think about their abilities to effectively cope with problems, like, How come things aren’t worse for you? What stopped total disaster from occurring? How did you avoid falling apart? (Australian Institute of Professional Counsellors, 2009).

The most powerful word in the Solution Focused Brief Therapy vocabulary – The Solution Focused Universe

A typical treatment plan in SFBT will include several factors relevant to the treatment, including:

- The reason for referral, or the problem the client is experiencing that brought him or her to treatment;

- A diagnosis (if any);

- List of medications taken (if any);

- Current symptoms;

- Support for the client (family, friends, other mental health professionals, etc.);

- Modality or treatment type;

- Frequency of treatment;

- Goals and objectives;

- Measurement criteria for progress on goals;

- Client strengths ;

- Barriers to progress.

All of these are common and important components of a successful treatment plan. Some of these components (e.g., diagnosis and medications) may be unaddressed or acknowledged only as a formality in SFBT due to its usual focus on less severe mental health issues. Others are vital to treatment progress and potential success in SFBT, including goals, objectives, measurement criteria, and client strengths.

To this end, therapists are increasingly leveraging the benefits of technology to help develop, execute, and evaluate the outcomes of treatment plans efficiently.

Among these technologies are many digital platforms that therapists can use to carry out some steps in clients’ treatment plans outside of face-to-face sessions.

For example, by adopting a versatile blended care platform such as Quenza , an SFBT practitioner may carry out some of the initial steps in the assessment/diagnosis phase of a treatment plan, such as by inviting the client to complete a digital diagnostic questionnaire.

Likewise, the therapist may use the platform to send digital activities to the client’s smartphone, such as an end-of-day reflection inviting the client to recount their application of the ‘Do One Thing Different’ technique to overcome a problem.

These are just a few ideas for how you might use a customizable blended care tool such as Quenza to help carry out several of the steps in an SFBT treatment plan.

Some of the potential disadvantages for therapists include (George, 2010):

- The potential for clients to focus on problems that the therapist believes are secondary problems. For example, the client may focus on a current relationship problem rather than the underlying self-esteem problem that is causing the relationship woes. SFBT dictates that the client is the expert, and the therapist must take what the client says at face value;

- The client may decide that the treatment is successful or complete before the therapist is ready to make the same decision. This focus on taking what the client says at face value may mean the therapist must end treatment before they are convinced that the client is truly ready;

- The hard work of the therapist may be ignored. When conducted successfully, it may seem that clients solved their problems by themselves, and didn’t need the help of a therapist at all. An SFBT therapist may rarely get credit for the work they do but must take all the blame when sessions end unsuccessfully.

Some of the potential limitations for clients include (Antin, 2018):

- The focus on quick solutions may miss some important underlying issues;

- The quick, goal-oriented nature of SFBT may not allow for an emotional, empathetic connection between therapist and client.

- If the client wants to discuss factors outside of their immediate ability to effect change, SFBT may be frustrating in its assumption that clients are always able to fix or address their problems.

Generally, SFBT can be an excellent treatment for many of the common stressors people experience in their lives, but it may be inappropriate if clients want to concentrate more on their symptoms and how they got to where they are today. As noted earlier, it is also generally not appropriate for clients with major mental health disorders.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

First, both SFBT and positive psychology share a focus on the positive—on what people already have going for them and on what actions they can take. While problems are discussed and considered in SFBT, most of the time and energy is spent on discussing, thinking about, and researching what is already good, effective, and successful.

Second, both SFBT and positive psychology consider the individual to be his or her own best advocate, the source of information on his or her problems and potential solutions, and the architect of his or her own treatment and life success. The individual is considered competent, able, and “enough” in both SFBT and positive psychology.

This assumption of the inherent competence of individuals has run both subfields into murky waters and provoked criticism, particularly when systemic and societal factors are considered. While no respectable psychologist would disagree that an individual is generally in control of his or her own actions and, therefore, future, there is considerable debate about what level of influence other factors have on an individual’s life.

While many of these criticisms are valid and bring up important points for discussion, we won’t dive too deep into them in this piece. Suffice it to say that both SFBT and positive psychology have important places in the field of psychology and, like any subfield, may not apply to everyone and to all circumstances.

However, when they do apply, they are both capable of producing positive, lasting, and life-changing results.

Solution-focused therapy puts problem-solving at the forefront of the conversation and can be particularly useful for clients who aren’t suffering from major mental health issues and need help solving a particular problem (or problems). Rather than spending years in therapy, SFBT allows such clients to find solutions and get results quickly.

Have you ever tried Solution-Focused Brief Therapy, as a therapist or as a client? What did you think of the focus on solutions? Do you think SFBT misses anything important by taking the spotlight off the client’s problem(s)? Let us know in the comments section.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

Antin, L. (2018). Solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT). Good Therapy. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/solution-focused-therapy

- Australian Institute of Professional Counsellors. (2009, March 30). Solution-focused techniques. Counseling Connection. Retrieved from http://www.counsellingconnection.com/index.php/2009/03/30/solution-focused-techniques/

- Berg, I. K. (n.d.). About solution-focused brief therapy. SFBTA . Retrieved from http://www.sfbta.org/about_sfbt.html

- Coffen, R. (n.d.). Do one thing different [Handout]. Retrieved from https://www.andrews.edu/~coffen/Do%20one%20thing%20different.pdf

- Focus on Solutions. (2013, October 28). The brief solution-focused model. Focus on solutions: Leaders in solution-focused training. Retrieved from http://www.focusonsolutions.co.uk/solutionfocused/

- George, E. (2010). Disadvantages of solution focus? BRIEF. Retrieved from https://www.brief.org.uk/resources/faq/disadvantages-of-solution-focus

- Iveson, C. (2002). Solution-focused brief therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 8 (2), 149-156.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Vinnicombe, G. (n.d.). Greg’s SFBT handout. Useful Conversations. Retrieved from http://www.usefulconversations.com/downloads

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thank you. I’m about to start an MMFT internship, and SFBT is the model I prefer. You put everything in perspective.

Great insights. I have a client who has become a bit disengaged with our work together. This gives me a really helpful new approach for our upcoming sessions. He’s very focused on the problem and wanting a “quick fix.” This might at least get us on that path. Thank you!

Hi Courtney, great paper! I will like to know more about the limitations to SFT and noticed that you provided an intext citation to Antin 2016. Would you be able to provide the full reference? Thank you!

Thank you for bringing this to our attention. The reference has now been updated in the reference list — this should be Antin (2018):

– Nicole | Community Manager

The only thing tat was revealed to me while reading this article is the client being able to recognize the downfall of what got them into their problem in the first place. I felt that maybe a person should understand the problem to the extent that they may understand how to recognize what led to the problem in the first place. Understanding the process of how something broke down would give one knowledge and wisdom that may be able to be applied in future instances when something may go wrong again. Even if the thing is new (machine or person) having the wisdom and understanding of the cause that led to the effect may help prevent and or overcome an arising problem in the future. Not being able to recognize the process that brought down the machine and or human may be like adhering to ignorance, although they say ignorance is bliss in case of an emergency it would be better to be informed rather then blindly ignorant, as the knowledge of how the problem surfaced in the first place may alleviate unwarranted suffering sooner rather than later. But then again looking at it this way I may work myself out of a job if my clients never came back to see me. However is it about me or them or the greater societal structural good that we can induce through our education, skills, training, experience, and good will good faith effort to instill social justice coupled with lasting change for the betterment of human society and the world as a whole.

Very very helpful, thank you for writing. Just one point “While no respectable psychologist would disagree that an individual is generally in control of his or her own actions and, therefore, future, there is considerable debate about what level of influence other factors have on an individual’s life.” I think any psychologist that has worked in neurological dysfunction would probably acknowledge consciousness and ‘voluntary control’ are not that straight-forward. Generally though, I suppose there’s that whole debate of if we are ever in control of our actions or even our thoughts. It may well boil down to what we mean by ‘we’, as in what are we? A bundle of fibres acting on memories and impulses? A unique body of energy guided by intangible forces? Maybe I am not a respectable psychologist 🙂

This article provided me with insight on how to proceed with a role-play session in my CBT graduate course. Thank you!

Hi Derrick, That’s fantastic that you were able to find some guidance in this post. Best of luck with your grad students! – Nicole | Community Manager

Thank You…Great input and clarity . I now have light…

I was looking everywhere for a simple explanation for my essay and this is it!! thank you so much for this is was very useful and I learned a lot.

Very well done. Thank you for the multitude of insights.

Thank you for such a good passage discussed. I really have a great time understanding it.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Holistic Therapy: Healing Mind, Body, and Spirit

The term “holistic” in health care can be dated back to Hippocrates over 2,500 years ago (Relman, 1979). Hippocrates highlighted the importance of viewing individuals [...]

Trauma-Informed Therapy Explained (& 9 Techniques)

Trauma varies significantly in its effect on individuals. While some people may quickly recover from an adverse event, others might find their coping abilities profoundly [...]

Recreational Therapy Explained: 6 Degrees & Programs

Let’s face it, on a scale of hot or not, attending therapy doesn’t make any client jump with excitement. But what if that can be [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

Today's Therapist

What Is Problem Solving Therapy and Who Can It Help

February 1, 2017 By TodaysTherapist

Stressful events are part of everyday life. For some, coping with the negative effects of these events can be difficult, whether stressors are considered large (such as the death of a loved one) or small (like making a mistake at work). Stressors can create or exacerbate psychological and physical health problems. Problem solving therapy can help individuals develop effective coping methods for dealing with stressors in their lives by providing structured goals and coaching adaptation skills for decision-making situations. While this article provides some facts on problem solving therapy, it is strongly advised that individuals considering problem solving therapy receive care from licensed professionals.

What Is Problem Solving Therapy?

Problem Solving Therapy (PST), or structured problem solving, is psychological treatment used to help clients manage stressful life events. Therapists employ behavioral and cognitive intervention techniques to assist clients in establishing and actualizing goals and creating effective problem-solving, stress management techniques. Clients are encouraged and guided in how to be more proactive in their daily lives and make decisions that help them achieve goals. Core components of PST are addressing problem orientation, explicitly defining problems the client faces, coming up with and evaluating solutions, and breaking problems down into achievable, reasonable, and ultimately less stressful steps.

Solving Problems Outcomes

PST involves finding ways for individuals to change the stressful nature of situations and how they respond to stressors. Generally, problem-solving outcomes are based upon problem-solving style and problem orientation . Problem orientation is the feelings and thoughts a person has about their problems and perceived ability to resolve them. A positive problem orientation generally leads the person to enhance problem-solving efforts while a negative problem orientation tends to lead to the person being inhibited in solving their problems. Problem-solving style is behavioral and cognitive activities targeted at coping with stressors. Those with ineffective styles tend to report having more stressors and negative life events.

Problem solving therapy is essentially a series of training sessions in learning how to utilize adaptive problem solving skills that help clients better deal with and/or resolve problems that arise in their daily lives. Clients learn how to make more effective decisions for themselves, come up with their own creative ways to solve problems, and identify barriers or obstacles that surface when trying to reach their goals and how best to negate these hurdles. The overall intended outcome is that a client will feel more confident in their decision-making and problem-solving techniques and will be able to carry on their solutions as independently as possible.

Medical Conditions and Problem Solving Therapy

PST can be used by General Practitioners (GPs) to help treat difficult medical conditions, such as chronic pain management. As with a therapist, GPs have clients identify problems they want solved, set up goals, have clients come up with solutions for how they would like to solve the problem, weigh pros and cons of each solution in order to select the best one, and implement the solution. Together, a GP and client can review how well the selected solution is working and make any necessary changes. Again, this article is to provide helpful information in learning about PST; it is, therefore, highly recommended that one seeks help from a licensed, well-reputed professional who can help implement and analyze PST goals.

Developing and Achieving Problem Solving Therapy Goals

Therapists and GPs tend to use PST with clients who seem to be having difficulties coping with stressful life situations that can become confusing and overwhelming. The goals of PST revolve around meeting four key therapy objectives:

- Improving the client’s positive orientation;

- Reducing the client’s negative orientation;

- Enhancing the client’s ability to identify what is causing a problem, coming up with a few potential solutions, conducting cost-benefit analysis to determine the best solution, implementing the solution, then analyzing the outcome;

- Reducing impulsive and ultimately ineffective methods for attempting to solve problems.

Since every client is a different person and has diverse needs, therapists and doctors try to allow as much creative and analytic processing by the client as possible, although PST relies on the four basic components mentioned in the list above.

Therapists and clients alike should be aware of several obstacles that can occur during the PST process, including the client experiencing cognitive overload, difficulties with emotional regulation, usage of ineffective or maladaptive problem solving styles, feelings of hopelessness leading to decreased motivation to follow through on goals, and difficulties removing oneself from negative moods or thought patterns.

Who Can Benefit from Problem Solving Therapy?

Problem solving therapy can be beneficial for many different people. Since there is flexibility in regard to treatment goals and methods for achieving them, PST can be used in a group setting or one-on-one with an individual client. Since negative stressors are scientifically linked to mental and physical health problems, problem solving therapy can be beneficial to almost anyone, so long as they are open to the idea of pursuing treatment and engaging in the process.

PST has been found to be an effective therapeutic method for clients who are dealing with a vast array of mental, physical and emotional conditions. These conditions include some personality disorders, major depressive disorder, suicidal ideation, generalized anxiety disorder, relationship issues, emotional duress, and medically-based issues that result in emotional and physical pain (such as fibromyalgia, Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism, diabetes, and cancer).

Problem solving therapy is a widely-acknowledged tool used by therapists and general medical practitioners alike to help clients find proactive and reasonable ways to deal with the stressful events that occur in their lives. Overall, PST can help people find meaningful, creative, and adjustable ways of reaching their problem-resolution goals and ultimately lead to a better quality of living for those dealing with major physical and mental health concerns. Anyone considering PST should contact a trained medical or counseling professional to inquire about how this type of therapy could potentially suit their needs.

Image from depositphotos.com.

Encyclopedia of Geropsychology pp 1874–1883 Cite as

Problem-Solving Therapy

- Sherry A. Beaudreau 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Christine E. Gould 2 , 5 ,

- Erin Sakai 6 &

- J. W. Terri Huh 6 , 7

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2017

101 Accesses

Behavioral intervention; Skills-based therapy; Treatment

Problem-solving therapy (PST), developed by Nezu and colleagues, is a non-pharmacological, empirically supported cognitive-behavioral treatment (D’Zurilla and Nezu 2006 ; Nezu et al. 1989 ). The problem-solving framework draws from a stress-diathesis model, namely, that life stress interacts with an individual’s predisposition toward developing a psychiatric disorder. The driving model behind PST posits that individuals who experience difficulty solving life’s problems or coping with stressors of everyday living struggle with psychiatric symptoms more often than individuals considered as good problem solvers. This psychological treatment teaches a step-by-step approach to the process of identifying and implementing adaptive solutions for daily problems. By teaching individuals to solve their problems more effectively and efficiently, this model assumes that their stress and related psychiatric symptoms will...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Alexopoulos, G. S., Kiosses, D. N., Heo, M., Murphy, C. F., Shanmugham, B., & Gunning-Dixon, F. (2005). Executive dysfunction and the course of geriatric depression. Biological Psychiatry, 58 (3), 204–210.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Areán, P. A., & Huh, J. W. T. (2006). Problem-solving therapy with older adults. In S. H. Qualls & B. G. Knight (Eds.), Psychotherapy for depression in older adults (1st ed., pp. 133–149). Hoboken: Wiley.

Google Scholar

Areán, P., Hegel, M., Vannoy, S., Fan, M. Y., & Unuzter, J. (2008). Effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for older, primary care patients with depression: Results from the IMPACT project. Gerontologist, 48 (3), 311–323.

Ciechanowski, P., Wagner, E., Schmaling, K., Schwartz, S., Williams, B., Diehr, P., Kulzer, J., Gray, S., Collier, C., & LoGerfo, J. (2004). Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 291 (13), 1569–1577.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Crabb, R. M., & Areán, P. A. (2015). Problem-solving treatment for late-life depression. In P. A. Areán (Ed.), Treatment of late-life depression, anxiety, and substance abuse (pp. 83–102). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Chapter Google Scholar

D’Zurilla, T. J., & Nezu, A. M. (2006). Problem-solving therapy: A positive approach to clinical intervention (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

D’Zurilla, T. J., Nezu, A. M., & Maydeu-Olivarez, A. (2002). Social problem-solving inventory – Revised (SPSI-R) . North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems.

Kiosses, D. N., & Alexopoulos, G. (2014). Problem-solving therapy in the elderly. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 1 (1), 15–26.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Knight, B. (2009). Adapting psychotherapy for working with older adults [DVD]. American Psychological Association. ISBN 9781433803666.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping . New York: Springer.

Lynch, T. R., & Smoski, M. J. (2009). Individual and group psychotherapy. In M. D. Steffens, D. Blazer, D. C. Steffens, & M. E. Thakur (Eds.), The American Psychiatric Publishing text book of geriatric psychiatry (4th ed., pp. 521–538). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Mikami, K., Jorge, R. E., Moser, D. J., Arndt, S., Jang, M., Solodkin, A., Small, S. L., Fonzetti, P., Hegel, M. T., & Robinson, R. G. (2014). Prevention of post-stroke generalized anxiety disorder, using escitalopram or problem-solving therapy. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 26 (4), 323–328.

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & Perri, M. G. (1989). Problem-solving therapy for depression: Therapy, research, and clinical guidelines . New York: Wiley.

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., Friedman, S. H., Faddis, S., & Houts, P. S. (1998). Helping cancer patients cope: A problem-solving approach . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Book Google Scholar

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2007). Solving life’s problems: A 5 step guide to enhanced well-being . New York: Springer.

Shah, A., Scogin, F., & Floyd, M. (2012). Evidence-based psychological treatments for geriatric depression. In F. Scogin & A. Shah (Eds.), Making evidence-based psychological treatments work with older adults (1st ed., pp. 87–130). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sharpe, L., Gittins, C. B., Correia, H. M., Meade, T., Nicholas, M. K., Raue, P. J., McDonald, S., & Areán, P. A. (2012). Problem-solving versus cognitive restructuring of medically ill seniors with depression (PROMISE-D trial): Study protocol and design. BMC Psychiatry, 12 (1), 207–216.

Simon, S. S., Cordás, T. A., & Bottino, C. M. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapies in older adults with depression and cognitive deficits: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30 (3), 223–233.

Zarit, S. (1996). Interventions with family caregivers. In S. H. Zarit & B. G. Knight (Eds.), Effective clinical interventions in a life-stage context: A guide to psychotherapy and aging (1st ed., pp. 139–159). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

Sherry A. Beaudreau & Christine E. Gould

Sierra Pacific Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, CA, USA

Sherry A. Beaudreau

School of Psychology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC), VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, CA, USA

Christine E. Gould

VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, CA, USA

Erin Sakai & J. W. Terri Huh

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

J. W. Terri Huh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sherry A. Beaudreau .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Nancy A. Pachana

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore (outside the USA)

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Beaudreau, S.A., Gould, C.E., Sakai, E., Huh, J.W.T. (2017). Problem-Solving Therapy. In: Pachana, N.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Geropsychology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-082-7_90

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-082-7_90

Published : 31 January 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-287-081-0

Online ISBN : 978-981-287-082-7

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Reference Module Biomedical and Life Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Free Therapy Techniques

- Anxiety Treatment

- Business and Marketing

- CBT Techniques

- Client Motivation

- Dealing With Difficult Clients

- Hypnotherapy Techniques

- Insomnia and Sleep

- Personal Skills

- Practitioner in Focus

- Psychology Research

- Psychotherapy Techniques

- PTSD, Trauma and Phobias

- Relationships

- Self Esteem

- Sensible Psychology Dictionary

- Smoking Cessation and Addiction

- The Dark Side of Your Emotional Needs

- Uncommon Philosophy

How to Use Problem-Solving Therapy with Your Clients

8 questions you can ask to help clients solve problems faster.

“Any idiot can face a crisis – it’s day to day living that wears you out.”

– Anton Chekhov

“Persistence and resilience only come from having been given the chance to work through difficult problems.”

– Gever Tulley

A common fantasy is of a golden and entirely problem-free future. Sound familiar? The assumption of such a fantasy is, of course, that a life free of problems is (a) possible and (b) by definition, one of happiness.

But could you really live without problems?

We are problem-solving creatures. 1 I suspect we can only be truly happy if we have problems, because rising to challenge gives life meaning. 2 But, paradoxically, we often feel un happy until we have solved our problems. Ah, the paradox of being human! But if we dig into this, the paradox dissolves.

This is because some problems are more problematic, depressing, and overwhelming than others. Some problems are intriguing and fun, while some are depressing and limiting, or at least seem like that. Problems are the fertilizer that helps us grow and develop. But, of course, it’s the kind of problems we have, and how we respond to them, that determines how meaningful life is for us.

Research has found that the kind of happiness associated with taking and getting is less physically beneficial for people than the kind we experience when we seek to help other people and make the world better in some way. The kind of happiness, or perhaps I should say enjoyment, associated with drug taking and drinking, for example, had similar effects on the body to the stress response from terrible adversity. 3

Which leads us to a cliché, but one worth considering.

The more you give, the more you get

When we help others, even when we help ‘us’ rather than simply ‘I’, we are seeking to solve problems that are connected to a sense of a wider, more meaningful life. This kind of satisfaction tends to be more nourishing. Simply looking for repeated thrills or highs can, pretty quickly, start to feel as meaningful as continually trying to fill a bucket with no bottom to it. A ‘bucket list’ is all very well… if the bucket being filled leads to fulfillment .

So, we can, I think, learn a lot about a person from their stated problems. Compare “My life isn’t providing me with meaning!” with “How can I make a difference?”

It’s a terrible cliché to say: “The more you give the more you get” but I would add to this truism “… especially when you forget about getting.”

But if finding solutions to problems and rising to the challenge of making things better can give us that all-important sense of meaning, what is the problem with problems?

Problematic problems

Problems become problematic when our clients lose hope that they can solve them, and especially when they can’t stop thinking about them.

Learned helplessness causes our clients to wrongly feel they’re less empowered than they actually are. They may have come to feel that life simply happens to them, and it had better treat them kindly because they don’t have any influence over life.

The other problem with problems is when people can think of nothing else. If we mull over our problems in the absence of hope, then we become dangerously vulnerable to depression. 4,5 If we feel we can’t solve problems, then we may substitute imagination and circular thinking for action.

If a person doesn’t have volition over where they place their attention, they will find that their focus becomes locked on what makes them feel bad. They will feel unable to withdraw their attention from that particular focus. We see this locking of attention, and difficulty withdrawing it, in addiction, obsession, and, of course, depression.

Sometimes, this kind of locked attention on problems can prove to be worse than the problems themselves.

The problem behind the problem

Because professionals like to slice reality thinly, problem-solving therapy has come to be seen as a type of therapy.

But all therapy is problem-solving therapy. Either we seek to help our clients ‘solve the problem’ by feeling and thinking differently about it, or we help them find ways to solve an actual practical problem (or both!).

Seek to establish how many of your clients’ problems are themselves maladaptive attempts to solve problems.

A client may have come to you for help because they are a control freak . But what problems is their control freakery maladaptively trying to solve? Anxiety ? Fear ? Jealousy ?

The first part of a therapy session, along with building rapport , is information gathering . So what questions can we ask our clients about their problems as a first step to helping them solve them?

Problem-solving therapy questions