Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Mr. E.A. is a 40-year-old black male who presented to his Primary Care Provider for a diabetes follow up on October 14th, 2019. The patient complains of a general constant headache that has lasted the past week, with no relieving factors. He also reports an unusual increase in fatigue and general muscle ache without any change in his daily routine. Patient also reports occasional numbness and tingling of face and arms. He is concerned that these symptoms could potentially be a result of his new diabetes medication that he began roughly a week ago. Patient states that he has not had any caffeine or smoked tobacco in the last thirty minutes. During assessment vital signs read BP 165/87, Temp 97.5 , RR 16, O 98%, and HR 86. E.A states he has not lost or gained any weight. After 10 mins, the vital signs were retaken BP 170/90, Temp 97.8, RR 15, O 99% and HR 82. Hg A1c 7.8%, three months prior Hg A1c was 8.0%. Glucose 180 mg/dL (fasting). FAST test done; negative for stroke. CT test, Chem 7 and CBC have been ordered.

Past medical history

Diagnosed with diabetes (type 2) at 32 years old

Overweight, BMI of 31

Had a cholecystomy at 38 years old

Diagnosed with dyslipidemia at 32 years old

Past family history

Mother alive, diagnosed diabetic at 42 years old

Father alive with Hypertension diagnosed at 55 years old

Brother alive and well at 45 years old

Sister alive and obese at 34 years old

Pertinent social history

Social drinker on occasion

Smokes a pack of cigarettes per day

Works full time as an IT technician and is in graduate school

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Graphical Abstracts and Tidbit

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About American Journal of Hypertension

- Editorial Board

- Board of Directors

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- AJH Summer School

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Clinical management and treatment decisions, hypertension in black americans, pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in black americans.

- < Previous

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Suzanne Oparil, Case study, American Journal of Hypertension , Volume 11, Issue S8, November 1998, Pages 192S–194S, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(98)00195-2

- Permissions Icon Permissions

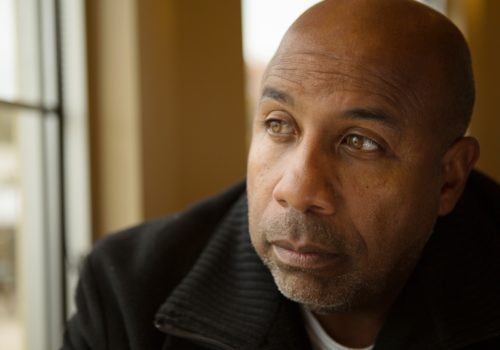

Ms. C is a 42-year-old black American woman with a 7-year history of hypertension first diagnosed during her last pregnancy. Her family history is positive for hypertension, with her mother dying at 56 years of age from hypertension-related cardiovascular disease (CVD). In addition, both her maternal and paternal grandparents had CVD.

At physician visit one, Ms. C presented with complaints of headache and general weakness. She reported that she has been taking many medications for her hypertension in the past, but stopped taking them because of the side effects. She could not recall the names of the medications. Currently she is taking 100 mg/day atenolol and 12.5 mg/day hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), which she admits to taking irregularly because “... they bother me, and I forget to renew my prescription.” Despite this antihypertensive regimen, her blood pressure remains elevated, ranging from 150 to 155/110 to 114 mm Hg. In addition, Ms. C admits that she has found it difficult to exercise, stop smoking, and change her eating habits. Findings from a complete history and physical assessment are unremarkable except for the presence of moderate obesity (5 ft 6 in., 150 lbs), minimal retinopathy, and a 25-year history of smoking approximately one pack of cigarettes per day. Initial laboratory data revealed serum sodium 138 mEq/L (135 to 147 mEq/L); potassium 3.4 mEq/L (3.5 to 5 mEq/L); blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 19 mg/dL (10 to 20 mg/dL); creatinine 0.9 mg/dL (0.35 to 0.93 mg/dL); calcium 9.8 mg/dL (8.8 to 10 mg/dL); total cholesterol 268 mg/dL (< 245 mg/dL); triglycerides 230 mg/dL (< 160 mg/dL); and fasting glucose 105 mg/dL (70 to 110 mg/dL). The patient refused a 24-h urine test.

Taking into account the past history of compliance irregularities and the need to take immediate action to lower this patient’s blood pressure, Ms. C’s pharmacologic regimen was changed to a trial of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril, 5 mg/day; her HCTZ was discontinued. In addition, recommendations for smoking cessation, weight reduction, and diet modification were reviewed as recommended by the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI). 1

After a 3-month trial of this treatment plan with escalation of the enalapril dose to 20 mg/day, the patient’s blood pressure remained uncontrolled. The patient’s medical status was reviewed, without notation of significant changes, and her antihypertensive therapy was modified. The ACE inhibitor was discontinued, and the patient was started on the angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) losartan, 50 mg/day.

After 2 months of therapy with the ARB the patient experienced a modest, yet encouraging, reduction in blood pressure (140/100 mm Hg). Serum electrolyte laboratory values were within normal limits, and the physical assessment remained unchanged. The treatment plan was to continue the ARB and reevaluate the patient in 1 month. At that time, if blood pressure control remained marginal, low-dose HCTZ (12.5 mg/day) was to be added to the regimen.

Hypertension remains a significant health problem in the United States (US) despite recent advances in antihypertensive therapy. The role of hypertension as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is well established. 2–7 The age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension in non-Hispanic black Americans is approximately 40% higher than in non-Hispanic whites. 8 Black Americans have an earlier onset of hypertension and greater incidence of stage 3 hypertension than whites, thereby raising the risk for hypertension-related target organ damage. 1 , 8 For example, hypertensive black Americans have a 320% greater incidence of hypertension-related end-stage renal disease (ESRD), 80% higher stroke mortality rate, and 50% higher CVD mortality rate, compared with that of the general population. 1 , 9 In addition, aging is associated with increases in the prevalence and severity of hypertension. 8

Research findings suggest that risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke, particularly the role of blood pressure, may be different for black American and white individuals. 10–12 Some studies indicate that effective treatment of hypertension in black Americans results in a decrease in the incidence of CVD to a level that is similar to that of nonblack American hypertensives. 13 , 14

Data also reveal differences between black American and white individuals in responsiveness to antihypertensive therapy. For instance, studies have shown that diuretics 15 , 16 and the calcium channel blocker diltiazem 16 , 17 are effective in lowering blood pressure in black American patients, whereas β-adrenergic receptor blockers and ACE inhibitors appear less effective. 15 , 16 In addition, recent studies indicate that ARB may also be effective in this patient population.

Angiotensin-II receptor blockers are a relatively new class of agents that are approved for the treatment of hypertension. Currently, four ARB have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, and valsartan. Recently, a 528-patient, 26-week study compared the efficacy of eprosartan (200 to 300 mg/twice daily) versus enalapril (5 to 20 mg/daily) in patients with essential hypertension (baseline sitting diastolic blood pressure [DBP] 95 to 114 mm Hg). After 3 to 5 weeks of placebo, patients were randomized to receive either eprosartan or enalapril. After 12 weeks of therapy within the titration phase, patients were supplemented with HCTZ as needed. In a prospectively defined subset analysis, black American patients in the eprosartan group (n = 21) achieved comparable reductions in DBP (−13.3 mm Hg with eprosartan; −12.4 mm Hg with enalapril) and greater reductions in systolic blood pressure (SBP) (−23.1 with eprosartan; −13.2 with enalapril), compared with black American patients in the enalapril group (n = 19) ( Fig. 1 ). 18 Additional trials enrolling more patients are clearly necessary, but this early experience with an ARB in black American patients is encouraging.

Efficacy of the angiotensin II receptor blocker eprosartan in black American with mild to moderate hypertension (baseline sitting DBP 95 to 114 mm Hg) in a 26-week study. Eprosartan, 200 to 300 mg twice daily (n = 21, solid bar), enalapril 5 to 20 mg daily (n = 19, diagonal bar). †10 of 21 eprosartan patients and seven of 19 enalapril patients also received HCTZ. Adapted from data in Levine: Subgroup analysis of black hypertensive patients treated with eprosartan or enalapril: results of a 26-week study, in Programs and abstracts from the 1st International Symposium on Angiotensin-II Antagonism, September 28–October 1, 1997, London, UK.

00195-2/2/m_ajh.192S.f1.jpeg?Expires=1715912260&Signature=m2JuurBni9XVjiybM3wXE401VWu4HNWdtD79r0atsyyKUC2aP3ObV-PT7Is78Qblcdrt5EPN3x3KfsCiJGsSTx1mEEBJokzNSQnsRxO6y2rP0wQwOub0kjziZp1wW8sr5aXAZrePCbZcYswK5-Yao-wojv7yn3Z-hiQU2mAD-oiytEMnDwMZft~WXpzxZTF5VOaj1DuXeJ~gldf0LKbtdHDOtvytG7ywcwd4cPMULAVxXSHMeX9JQJAaLqQ2Cr2Q9NefpOeccUKUQU94nY6f0sUAiPI5RlZ93CzskWmJkCf2gEv307Dt~DhaOFE6xPs38RP-HEa285lZ0X1ADKGhcg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Approximately 30% of all deaths in hypertensive black American men and 20% of all deaths in hypertensive black American women are attributable to high blood pressure. Black Americans develop high blood pressure at an earlier age, and hypertension is more severe in every decade of life, compared with whites. As a result, black Americans have a 1.3 times greater rate of nonfatal stroke, a 1.8 times greater rate of fatal stroke, a 1.5 times greater rate of heart disease deaths, and a 5 times greater rate of ESRD when compared with whites. 19 Therefore, there is a need for aggressive antihypertensive treatment in this group. Newer, better tolerated antihypertensive drugs, which have the advantages of fewer adverse effects combined with greater antihypertensive efficacy, may be of great benefit to this patient population.

1. Joint National Committee : The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure . Arch Intern Med 1997 ; 24 157 : 2413 – 2446 .

Google Scholar

2. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension: Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg . JAMA 1967 ; 202 : 116 – 122 .

3. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension: II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg . JAMA 1970 ; 213 : 1143 – 1152 .

4. Pooling Project Research Group : Relationship of blood pressure, serum cholesterol, smoking habit, relative weight and ECG abnormalities to the incidence of major coronary events: Final report of the pooling project . J Chronic Dis 1978 ; 31 : 201 – 306 .

5. Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program Cooperative Group : Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program: I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension . JAMA 1979 ; 242 : 2562 – 2577 .

6. Kannel WB , Dawber TR , McGee DL : Perspectives on systolic hypertension: The Framingham Study . Circulation 1980 ; 61 : 1179 – 1182 .

7. Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program Cooperative Group : The effect of treatment on mortality in “mild” hypertension: Results of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program . N Engl J Med 1982 ; 307 : 976 – 980 .

8. Burt VL , Whelton P , Roccella EJ et al. : Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population: Results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991 . Hypertension 1995 ; 25 : 305 – 313 .

9. Klag MJ , Whelton PK , Randall BL et al. : End-stage renal disease in African-American and white men: 16-year MRFIT findings . JAMA 1997 ; 277 : 1293 – 1298 .

10. Neaton JD , Kuller LH , Wentworth D et al. : Total and cardiovascular mortality in relation to cigarette smoking, serum cholesterol concentration, and diastolic blood pressure among black and white males followed up for five years . Am Heart J 1984 ; 3 : 759 – 769 .

11. Gillum RF , Grant CT : Coronary heart disease in black populations II: Risk factors . Heart J 1982 ; 104 : 852 – 864 .

12. M’Buyamba-Kabangu JR , Amery A , Lijnen P : Differences between black and white persons in blood pressure and related biological variables . J Hum Hypertens 1994 ; 8 : 163 – 170 .

13. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group : Five-year findings of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program: mortality by race-sex and blood pressure level: a further analysis . J Community Health 1984 ; 9 : 314 – 327 .

14. Ooi WL , Budner NS , Cohen H et al. : Impact of race on treatment response and cardiovascular disease among hypertensives . Hypertension 1989 ; 14 : 227 – 234 .

15. Weinberger MH : Racial differences in antihypertensive therapy: evidence and implications . Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1990 ; 4 ( suppl 2 ): 379 – 392 .

16. Materson BJ , Reda DJ , Cushman WC et al. : Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men: A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo . N Engl J Med 1993 ; 328 : 914 – 921 .

17. Materson BJ , Reda DJ , Cushman WC for the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Department of Veterans Affairs single-drug therapy of hypertension study: Revised figures and new data . Am J Hypertens 1995 ; 8 : 189 – 192 .

18. Levine B : Subgroup analysis of black hypertensive patients treated with eprosartan or enalapril: results of a 26-week study , in Programs and abstracts from the first International Symposium on Angiotensin-II Antagonism , September 28 – October 1 , 1997 , London, UK .

19. American Heart Association: 1997 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update . American Heart Association , Dallas , 1997 .

- hypertension

- blood pressure

- african american

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1941-7225

- Copyright © 2024 American Journal of Hypertension, Ltd.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Newly diagnosed hypertension: case study

Affiliation.

- 1 Trainee Advanced Nurse Practitioner, East Belfast GP Federation, Northern Ireland.

- PMID: 37344134

- DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2023.32.12.556

The role of an advanced nurse practitioner encompasses the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of a range of conditions. This case study presents a patient with newly diagnosed hypertension. It demonstrates effective history taking, physical examination, differential diagnoses and the shared decision making which occurred between the patient and the professional. It is widely acknowledged that adherence to medications is poor in long-term conditions, such as hypertension, but using a concordant approach in practice can optimise patient outcomes. This case study outlines a concordant approach to consultations in clinical practice which can enhance adherence in long-term conditions.

Keywords: Adherence; Advanced nurse practitioner; Case study; Concordance; Hypertension.

- Diagnosis, Differential

- Hypertension* / diagnosis

- Hypertension* / drug therapy

- Nurse Practitioners*

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Presentation

Clinical pearls, case study: treating hypertension in patients with diabetes.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Evan M. Benjamin; Case Study: Treating Hypertension in Patients With Diabetes. Clin Diabetes 1 July 2004; 22 (3): 137–138. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.22.3.137

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

L.N. is a 49-year-old white woman with a history of type 2 diabetes,obesity, hypertension, and migraine headaches. The patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 9 years ago when she presented with mild polyuria and polydipsia. L.N. is 5′4″ and has always been on the large side,with her weight fluctuating between 165 and 185 lb.

Initial treatment for her diabetes consisted of an oral sulfonylurea with the rapid addition of metformin. Her diabetes has been under fair control with a most recent hemoglobin A 1c of 7.4%.

Hypertension was diagnosed 5 years ago when blood pressure (BP) measured in the office was noted to be consistently elevated in the range of 160/90 mmHg on three occasions. L.N. was initially treated with lisinopril, starting at 10 mg daily and increasing to 20 mg daily, yet her BP control has fluctuated.

One year ago, microalbuminuria was detected on an annual urine screen, with 1,943 mg/dl of microalbumin identified on a spot urine sample. L.N. comes into the office today for her usual follow-up visit for diabetes. Physical examination reveals an obese woman with a BP of 154/86 mmHg and a pulse of 78 bpm.

What are the effects of controlling BP in people with diabetes?

What is the target BP for patients with diabetes and hypertension?

Which antihypertensive agents are recommended for patients with diabetes?

Diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Approximately two-thirds of people with diabetes die from complications of CVD. Nearly half of middle-aged people with diabetes have evidence of coronary artery disease (CAD), compared with only one-fourth of people without diabetes in similar populations.

Patients with diabetes are prone to a number of cardiovascular risk factors beyond hyperglycemia. These risk factors, including hypertension,dyslipidemia, and a sedentary lifestyle, are particularly prevalent among patients with diabetes. To reduce the mortality and morbidity from CVD among patients with diabetes, aggressive treatment of glycemic control as well as other cardiovascular risk factors must be initiated.

Studies that have compared antihypertensive treatment in patients with diabetes versus placebo have shown reduced cardiovascular events. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), which followed patients with diabetes for an average of 8.5 years, found that patients with tight BP control (< 150/< 85 mmHg) versus less tight control (< 180/< 105 mmHg) had lower rates of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and peripheral vascular events. In the UKPDS, each 10-mmHg decrease in mean systolic BP was associated with a 12% reduction in risk for any complication related to diabetes, a 15% reduction for death related to diabetes, and an 11% reduction for MI. Another trial followed patients for 2 years and compared calcium-channel blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors,with or without hydrochlorothiazide against placebo and found a significant reduction in acute MI, congestive heart failure, and sudden cardiac death in the intervention group compared to placebo.

The Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial has shown that patients assigned to lower BP targets have improved outcomes. In the HOT trial,patients who achieved a diastolic BP of < 80 mmHg benefited the most in terms of reduction of cardiovascular events. Other epidemiological studies have shown that BPs > 120/70 mmHg are associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in people with diabetes. The American Diabetes Association has recommended a target BP goal of < 130/80 mmHg. Studies have shown that there is no lower threshold value for BP and that the risk of morbidity and mortality will continue to decrease well into the normal range.

Many classes of drugs have been used in numerous trials to treat patients with hypertension. All classes of drugs have been shown to be superior to placebo in terms of reducing morbidity and mortality. Often, numerous agents(three or more) are needed to achieve specific target levels of BP. Use of almost any drug therapy to reduce hypertension in patients with diabetes has been shown to be effective in decreasing cardiovascular risk. Keeping in mind that numerous agents are often required to achieve the target level of BP control, recommending specific agents becomes a not-so-simple task. The literature continues to evolve, and individual patient conditions and preferences also must come into play.

While lowering BP by any means will help to reduce cardiovascular morbidity, there is evidence that may help guide the selection of an antihypertensive regimen. The UKPDS showed no significant differences in outcomes for treatment for hypertension using an ACE inhibitor or aβ-blocker. In addition, both ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to slow the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy. In the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE)trial, ACE inhibitors were found to have a favorable effect in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, whereas recent trials have shown a renal protective benefit from both ACE inhibitors and ARBs. ACE inhibitors andβ-blockers seem to be better than dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers to reduce MI and heart failure. However, trials using dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers in combination with ACE inhibitors andβ-blockers do not appear to show any increased morbidity or mortality in CVD, as has been implicated in the past for dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers alone. Recently, the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) in high-risk hypertensive patients,including those with diabetes, demonstrated that chlorthalidone, a thiazide-type diuretic, was superior to an ACE inhibitor, lisinopril, in preventing one or more forms of CVD.

L.N. is a typical patient with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Her BP control can be improved. To achieve the target BP goal of < 130/80 mmHg, it may be necessary to maximize the dose of the ACE inhibitor and to add a second and perhaps even a third agent.

Diuretics have been shown to have synergistic effects with ACE inhibitors,and one could be added. Because L.N. has migraine headaches as well as diabetic nephropathy, it may be necessary to individualize her treatment. Adding a β-blocker to the ACE inhibitor will certainly help lower her BP and is associated with good evidence to reduce cardiovascular morbidity. Theβ-blocker may also help to reduce the burden caused by her migraine headaches. Because of the presence of microalbuminuria, the combination of ARBs and ACE inhibitors could also be considered to help reduce BP as well as retard the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Overall, more aggressive treatment to control L.N.'s hypertension will be necessary. Information obtained from recent trials and emerging new pharmacological agents now make it easier to achieve BP control targets.

Hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular complications of diabetes.

Clinical trials demonstrate that drug therapy versus placebo will reduce cardiovascular events when treating patients with hypertension and diabetes.

A target BP goal of < 130/80 mmHg is recommended.

Pharmacological therapy needs to be individualized to fit patients'needs.

ACE inhibitors, ARBs, diuretics, and β-blockers have all been documented to be effective pharmacological treatment.

Combinations of drugs are often necessary to achieve target levels of BP control.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs are agents best suited to retard progression of nephropathy.

Evan M. Benjamin, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of medicine and Vice President of Healthcare Quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

Email alerts

- Online ISSN 1945-4953

- Print ISSN 0891-8929

- Diabetes Care

- Clinical Diabetes

- Diabetes Spectrum

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes

- Scientific Sessions Abstracts

- BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care

- ShopDiabetes.org

- ADA Professional Books

Clinical Compendia

- Clinical Compendia Home

- Latest News

- DiabetesPro SmartBrief

- Special Collections

- DiabetesPro®

- Diabetes Food Hub™

- Insulin Affordability

- Know Diabetes By Heart™

- About the ADA

- Journal Policies

- For Reviewers

- Advertising in ADA Journals

- Reprints and Permission for Reuse

- Copyright Notice/Public Access Policy

- ADA Professional Membership

- ADA Member Directory

- Diabetes.org

- X (Twitter)

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

- © Copyright American Diabetes Association

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Abegaz TM, Shehab A, Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, Elnour AA. Nonadherence to antihypertensive drugs. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017; 96:(4) https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000005641

Armitage LC, Davidson S, Mahdi A Diagnosing hypertension in primary care: a retrospective cohort study to investigate the importance of night-time blood pressure assessment. Br J Gen Pract. 2023; 73:(726)e16-e23 https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2022.0160

Barratt J. Developing clinical reasoning and effective communication skills in advanced practice. Nurs Stand. 2018; 34:(2)48-53 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11109

Bostock-Cox B. Nurse prescribing for the management of hypertension. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2013; 8:(11)531-536

Bostock-Cox B. Hypertension – the present and the future for diagnosis. Independent Nurse. 2019; 2019:(1)20-24 https://doi.org/10.12968/indn.2019.1.20

Chakrabarti S. What's in a name? Compliance, adherence and concordance in chronic psychiatric disorders. World J Psychiatry. 2014; 4:(2)30-36 https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v4.i2.30

De Mauri A, Carrera D, Vidali M Compliance, adherence and concordance differently predict the improvement of uremic and microbial toxins in chronic kidney disease on low protein diet. Nutrients. 2022; 14:(3) https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030487

Demosthenous N. Consultation skills: a personal reflection on history-taking and assessment in aesthetics. Journal of Aesthetic Nursing. 2017; 6:(9)460-464 https://doi.org/10.12968/joan.2017.6.9.460

Diamond-Fox S. Undertaking consultations and clinical assessments at advanced level. Br J Nurs. 2021; 30:(4)238-243 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.4.238

Diamond-Fox S, Bone H. Advanced practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Br J Nurs. 2021; 30:(9)526-532 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.9.526

Donnelly M, Martin D. History taking and physical assessment in holistic palliative care. Br J Nurs. 2016; 25:(22)1250-1255 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2016.25.22.1250

Fawcett J. Thoughts about meanings of compliance, adherence, and concordance. Nurs Sci Q. 2020; 33:(4)358-360 https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318420943136

Fisher NDL, Curfman G. Hypertension—a public health challenge of global proportions. JAMA. 2018; 320:(17)1757-1759 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.16760

Green S. Assessment and management of acute sore throat. Pract Nurs. 2015; 26:(10)480-486 https://doi.org/10.12968/pnur.2015.26.10.480

Harper C, Ajao A. Pendleton's consultation model: assessing a patient. Br J Community Nurs. 2010; 15:(1)38-43 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.1.45784

Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E. The Top 100 Drugs; Clinical Pharmacology and Practical Prescribing, 2nd edn. Scotland: Elsevier; 2019

Hobden A. Strategies to promote concordance within consultations. Br J Community Nurs. 2006; 11:(7)286-289 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2006.11.7.21443

Ingram S. Taking a comprehensive health history: learning through practice and reflection. Br J Nurs. 2017; 26:(18)1033-1037 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.18.1033

James A, Holloway S. Application of concepts of concordance and health beliefs to individuals with pressure ulcers. British Journal of Healthcare Management. 2020; 26:(11)281-288 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2019.0104

Jamison J. Differential diagnosis for primary care. A handbook for health care practitioners, 2nd edn. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006

History and Physical Examination. 2021. https://patient.info/doctor/history-and-physical-examination (accessed 26 January 2023)

Kumar P, Clark M. Clinical Medicine, 9th edn. The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017

Matthys J, Elwyn G, Van Nuland M Patients' ideas, concerns, and expectations (ICE) in general practice: impact on prescribing. Br J Gen Pract. 2009; 59:(558)29-36 https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X394833

McKinnon J. The case for concordance: value and application in nursing practice. Br J Nurs. 2013; 22:(13)766-771 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2013.22.13.766

McPhillips H, Wood AF, Harper-McDonald B. Conducting a consultation and clinical assessment of the skin for advanced clinical practitioners. Br J Nurs. 2021; 30:(21)1232-1236 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.21.1232

Moulton L. The naked consultation; a practical guide to primary care consultation skills.Abingdon: Radcliffe Publishing; 2007

Medicine adherence; involving patients in decisions about prescribed medications and supporting adherence.England: NICE; 2009

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. How do I control my blood pressure? Lifestyle options and choice of medicines patient decision aid. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/resources/patient-decision-aid-pdf-6899918221 (accessed 25 January 2023)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline NG136. 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136 (accessed 15 June 2023)

Nazarko L. Healthwise, Part 4. Hypertension: how to treat it and how to reduce its risks. Br J Healthc Assist. 2021; 15:(10)484-490 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjha.2021.15.10.484

Neighbour R. The inner consultation.London: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; 1987

The Code. professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates.London: NMC; 2018

Nuttall D, Rutt-Howard J. The textbook of non-medical prescribing, 2nd edn. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2016

O'Donovan K. The role of ACE inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2018; 13:(12)600-608 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2018.13.12.600

O'Donovan K. Angiotensin receptor blockers as an alternative to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2019; 14:(6)1-12 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2019.0009

Porth CM. Essentials of Pathophysiology, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2015

Rae B. Obedience to collaboration: compliance, adherence and concordance. Journal of Prescribing Practice. 2021; 3:(6)235-240 https://doi.org/10.12968/jprp.2021.3.6.235

Rostoft S, van den Bos F, Pedersen R, Hamaker ME. Shared decision-making in older patients with cancer - What does the patient want?. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021; 12:(3)339-342 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.08.001

Schroeder K. The 10-minute clinical assessment, 2nd edn. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2017

Thomas J, Monaghan T. The Oxford handbook of clinical examination and practical skills, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014

Vincer K, Kaufman G. Balancing shared decision-making with ethical principles in optimising medicines. Nurse Prescribing. 2017; 15:(12)594-599 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2017.15.12.594

Waterfield J. ACE inhibitors: use, actions and prescribing rationale. Nurse Prescribing. 2008; 6:(3)110-114 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2008.6.3.28858

Weiss M. Concordance, 6th edn. In: Watson J, Cogan LS Poland: Elsevier; 2019

Williams H. An update on hypertension for nurse prescribers. Nurse Prescribing. 2013; 11:(2)70-75 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2013.11.2.70

Adherence to long-term therapies, evidence for action.Geneva: WHO; 2003

Young K, Franklin P, Franklin P. Effective consulting and historytaking skills for prescribing practice. Br J Nurs. 2009; 18:(17)1056-1061 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2009.18.17.44160

Newly diagnosed hypertension: case study

Angela Brown

Trainee Advanced Nurse Practitioner, East Belfast GP Federation, Northern Ireland

View articles · Email Angela

The role of an advanced nurse practitioner encompasses the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of a range of conditions. This case study presents a patient with newly diagnosed hypertension. It demonstrates effective history taking, physical examination, differential diagnoses and the shared decision making which occurred between the patient and the professional. It is widely acknowledged that adherence to medications is poor in long-term conditions, such as hypertension, but using a concordant approach in practice can optimise patient outcomes. This case study outlines a concordant approach to consultations in clinical practice which can enhance adherence in long-term conditions.

Hypertension is a worldwide problem with substantial consequences ( Fisher and Curfman, 2018 ). It is a progressive condition ( Jamison, 2006 ) requiring lifelong management with pharmacological treatments and lifestyle adjustments. However, adopting these lifestyle changes can be notoriously difficult to implement and sustain ( Fisher and Curfman, 2018 ) and non-adherence to chronic medication regimens is extremely common ( Abegaz et al, 2017 ). This is also recognised by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2009) which estimates that between 33.3% and 50% of medications are not taken as recommended. Abegaz et al (2017) furthered this by claiming 83.7% of people with uncontrolled hypertension do not take medications as prescribed. However, leaving hypertension untreated or uncontrolled is the single largest cause of cardiovascular disease ( Fisher and Curfman, 2018 ). Therefore, better adherence to medications is associated with better outcomes ( World Health Organization, 2003 ) in terms of reducing the financial burden associated with the disease process on the health service, improving outcomes for patients ( Chakrabarti, 2014 ) and increasing job satisfaction for professionals ( McKinnon, 2013 ). Therefore, at a time when growing numbers of patients are presenting with hypertension, health professionals must adopt a concordant approach from the initial consultation to optimise adherence.

Great emphasis is placed on optimising adherence to medications ( NICE, 2009 ), but the meaning of the term ‘adherence’ is not clear and it is sometimes used interchangeably with compliance and concordance ( De Mauri et al, 2022 ), although they are not synonyms. Compliance is an outdated term alluding to paternalism, obedience and passivity from the patient ( Rae, 2021 ), whereby the patient's behaviour must conform to the health professional's recommendations. Adherence is defined as ‘the extent to which a person's behaviour, taking medication, following a diet and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider’ ( Chakrabarti, 2014 ). This term is preferred over compliance as it is less paternalistic ( Rae, 2021 ), as the patient is included in the decision-making process and has agreed to the treatment plan. While it is not yet widely embraced or used in practice ( Fawcett, 2020 ), concordance is recognised, not as a behaviour ( Rae, 2021 ) but more an approach or method which focuses on the equal partnership between patient and professional ( McKinnon, 2013 ) and enables effective and agreed treatment plans.

NICE last reviewed its guidance on medication adherence in 2019 and did not replace adherence with concordance within this. This supports the theory that adherence is an outcome of good concordance and the two are not synonyms. NICE (2009) guidelines, which are still valid, show evidence of concordant principles to maximise adherence. Integrating the theoretical principles of concordance into this case study demonstrates how the trainee advanced nurse practitioner aimed to individualise patient-centred care and improve health outcomes through optimising adherence.

Patient introduction and assessment

Jane (a pseudonym has been used to protect the patient's anonymity; Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) 2018 ), is a 45-year-old woman who had been referred to the surgery following an attendance at an emergency department. Jane had been role-playing as a patient as part of a teaching session for health professionals when it was noted that her blood pressure was significantly elevated at 170/88 mmHg. She had no other symptoms. Following an initial assessment at the emergency department, Jane was advised to contact her GP surgery for review and follow up. Nazarko (2021) recognised that it is common for individuals with high blood pressure to be asymptomatic, contributing to this being referred to as the ‘silent killer’. Hypertension is generally only detected through opportunistic checking of blood pressure, as seen in Jane's case, which is why adults over the age of 40 years are offered a blood pressure check every 5 years ( Bostock-Cox, 2013 ).

Consultation

Jane presented for a consultation at the surgery. Green (2015) advocates using a model to provide a structured approach to consultations which ensures quality and safety, and improves time management. Young et al (2009) claimed that no single consultation model is perfect, and Diamond-Fox (2021) suggested that, with experience, professionals can combine models to optimise consultation outcomes. Therefore, to effectively consult with Jane and to adapt to her individual personality, different models were intertwined to provide better person-centred care.

The Calgary–Cambridge model is the only consultation model that places emphasis on initiating the session, despite it being recognised that if a consultation gets off to a bad start this can interfere throughout ( Young et al, 2009 ). Being prepared for the consultation is key. Before Jane's consultation, the environment was checked to minimise interruptions, ensuring privacy and dignity ( Green, 2015 ; NMC, 2018 ), the seating arrangements optimised to aid good body language and communication ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ) and her records were viewed to give some background information to help set the scene and develop a rapport ( Young et al, 2009 ). Being adequately prepared builds the patient's trust and confidence in the professional ( Donnelly and Martin, 2016 ) but equally viewing patient information can lead to the professional forming preconceived ideas ( Donnelly and Martin, 2016 ). Therefore, care was taken by the trainee advanced nurse practitioner to remain open-minded.

During Jane's consultation, a thorough clinical history was taken ( Table 1 ). History taking is common to all consultation models and involves gathering important information ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ). History-taking needs to be an effective ( Bostock-Cox, 2019 ), holistic process ( Harper and Ajao, 2010 ) in order to be thorough, safe ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ) and aid in an accurate diagnosis. The key skill for taking history is listening and observing the patient ( Harper and Ajao, 2010 ). Sir William Osler said:‘listen to the patient as they are telling you the diagnosis’, but Knott and Tidy (2021) suggested that patients are barely given 20 seconds before being interrupted, after which they withdraw and do not offer any new information ( Demosthenous, 2017 ). Using this guidance, Jane was given the ‘golden minute’ allowing her to tell her ‘story’ without being interrupted ( Green, 2015 ). This not only showed respect ( Ingram, 2017 ) but interest in the patient and their concerns.

Once Jane shared her story, it was important for the trainee advanced nurse practitioner to guide the questioning ( Green 2015 ). This was achieved using a structured approach to take Jane's history, which optimised efficiency and effectiveness, and ensured that pertinent information was not omitted ( Young et al, 2009 ). Thomas and Monaghan (2014) set out clear headings for this purpose. These included:

- The presenting complaint

- Past medical history

- Drug history

- Social history

- Family history.

McPhillips et al (2021) also emphasised a need for a systemic enquiry of the other body systems to ensure nothing is missed. From taking this history it was discovered that Jane had been feeling well with no associated symptoms or red flags. A blood pressure reading showed that her blood pressure was elevated. Jane had no past medical history or allergies. She was not taking any medications, including prescribed, over the counter, herbal or recreational. Jane confirmed that she did not drink alcohol or smoke. There was no family history to note, which is important to clarify as a genetic link to hypertension could account for 30–50% of cases ( Nazarko, 2021 ). The information gathered was summarised back to Jane, showing good practice ( McPhillips et al, 2021 ), and Jane was able to clarify salient or missing points. Green (2015) suggested that optimising the patient's involvement in this way in the consultation makes her feel listened to which enhances patient satisfaction, develops a therapeutic relationship and demonstrates concordance.

During history taking it is important to explore the patient's ideas, concerns and expectations. Moulton (2007) refers to these as the ‘holy trinity’ and central to upholding person-centredness ( Matthys et al, 2009 ). Giving Jane time to discuss her ideas, concerns and expectations allowed the trainee advanced nurse practitioner to understand that she was concerned about her risk of a stroke and heart attack, and worried about the implications of hypertension on her already stressful job. Using ideas, concerns and expectations helped to understand Jane's experience, attitudes and perceptions, which ultimately will impact on her health behaviours and whether engagement in treatment options is likely ( James and Holloway, 2020 ). Establishing Jane's views demonstrated that she was eager to engage and manage her blood pressure more effectively.

Vincer and Kaufman (2017) demonstrated, through their case study, that a failure to ask their patient's viewpoint at the initial consultation meant a delay in engagement with treatment. They recognised that this delay could have been avoided with the use of additional strategies had ideas, concerns and expectations been implemented. Failure to implement ideas, concerns and expectations is also associated with reattendance or the patient seeking second opinions ( Green, 2015 ) but more positively, when ideas, concerns and expectations is implemented, it can reduce the number of prescriptions while sustaining patient satisfaction ( Matthys et al, 2009 ).

Physical examination

Once a comprehensive history was taken, a physical examination was undertaken to supplement this information ( Nuttall and Rutt-Howard, 2016 ). A physical examination of all the body systems is not required ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ) as this would be extremely time consuming, but the trainee advanced nurse practitioner needed to carefully select which systems to examine and use good examination technique to yield a correct diagnosis ( Knott and Tidy, 2021 ). With informed consent, clinical observations were recorded along with a full cardiovascular examination. The only abnormality discovered was Jane's blood pressure which was 164/90 mmHg, which could suggest stage 2 hypertension ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ). However, it is the trainee advanced nurse practitioner's role to use a hypothetico-deductive approach to arrive at a diagnosis. This requires synthesising all the information from the history taking and physical examination to formulate differential diagnoses ( Green, 2015 ) from which to confirm or refute before arriving at a final diagnosis ( Barratt, 2018 ).

Differential diagnosis

Hypertension can be triggered by secondary causes such as certain drugs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, decongestants, sodium-containing medications or combined oral contraception), foods (liquorice, alcohol or caffeine; Jamison, 2006 ), physiological response (pain, anxiety or stress) or pre-eclampsia ( Jamison, 2006 ; Schroeder, 2017 ). However, Jane had clarified that these were not contributing factors. Other potential differentials which could not be ruled out were the white-coat syndrome, renal disease or hyperthyroidism ( Schroeder, 2017 ). Further tests were required, which included bloods, urine albumin creatinine ratio, electrocardiogram and home blood pressure monitoring, to ensure a correct diagnosis and identify any target organ damage.

Joint decision making

At this point, the trainee advanced nurse practitioner needed to share their knowledge in a meaningful way to enable the patient to participate with and be involved in making decisions about their care ( Rostoft et al, 2021 ). Not all patients wish to be involved in decision making ( Hobden, 2006 ) and this must be respected ( NMC, 2018 ). However, engaging patients in partnership working improves health outcomes ( McKinnon, 2013 ). Explaining the options available requires skill so as not to make the professional seem incompetent and to ensure the patient continues to feel safe ( Rostoft et al, 2021 ).

Information supported by the NICE guidelines was shared with Jane. These guidelines advocated that in order to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, a clinic blood pressure reading of 140/90 mmHg or higher was required, with either an ambulatory or home blood pressure monitoring result of 135/85 mmHg or higher ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ). However, the results from a new retrospective study suggested that the use of home blood pressure monitoring is failing to detect ‘non-dippers’ or ‘reverse dippers’ ( Armitage et al, 2023 ). These are patients whose blood pressure fails to fall during their nighttime sleep. This places them at greater risk of cardiovascular disease and misdiagnosis if home blood pressure monitors are used, but ambulatory blood pressure monitors are less frequently used in primary care and therefore home blood pressure monitors appear to be the new norm ( Armitage et al, 2023 ).

Having discussed this with Jane she was keen to engage with home blood pressure monitoring in order to confirm the potential diagnosis, as starting a medication without a true diagnosis of hypertension could potentially cause harm ( Jamison, 2006 ). An accurate blood pressure measurement is needed to prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary therapy ( Jamison, 2006 ) and this is dependent on reliable and calibrated equipment and competency in performing the task ( Bostock-Cox, 2013 ). Therefore, Jane was given education and training to ensure the validity and reliability of her blood pressure readings.

For Jane, this consultation was the ideal time to offer health promotion advice ( Green, 2015 ) as she was particularly worried about her elevated blood pressure. Offering health promotion advice is a way of caring, showing support and empowerment ( Ingram, 2017 ). Therefore, Jane was provided with information on a healthy diet, the reduction of salt intake, weight loss, exercise and continuing to abstain from smoking and alcohol ( Williams, 2013 ). These were all modifiable factors which Jane could implement straight away to reduce her blood pressure.

Safety netting

The final stage and bringing this consultation to a close was based on the fourth stage of Neighbour's (1987) model, which is safety netting. Safety netting identifies appropriate follow up and gives details to the patient on what to do if their condition changes ( Weiss, 2019 ). It is important that the patient knows who to contact and when ( Young et al, 2009 ). Therefore, Jane was advised that, should she develop chest pains, shortness of breath, peripheral oedema, reduced urinary output, headaches, visual disturbances or retinal haemorrhages ( Schroeder, 2017 ), she should present immediately to the emergency department, otherwise she would be reviewed in the surgery in 1 week.

Jane was followed up in a second consultation 1 week later with her home blood pressure readings. The average reading from the previous 6 days was calculated ( Bostock-Cox, 2013 ) and Jane's home blood pressure reading was 158/82 mmHg. This reading ruled out white-coat syndrome as Jane's blood pressure remained elevated outside clinic conditions (white-coat syndrome is defined as a difference of more than 20/10 mmHg between clinic blood pressure readings and the average home blood pressure reading; NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ). Subsequently, Jane was diagnosed with stage 2 essential (or primary) hypertension. Stage 2 is defined as a clinic blood pressure of 160/100 mmHg or higher or a home blood pressure of 150/95 mmHg or higher ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ).

A diagnosis of hypertension can be difficult for patients as they obtain a ‘sick label’ despite feeling well ( Jamison, 2006 ). This is recognised as a deterrent for their motivation to initiate drug treatment and lifestyle changes ( Williams, 2013 ), presenting a greater challenge to health professionals, which can be addressed through concordance strategies. However, having taken Jane's bloods, electrocardiogram and urine albumin:creatinine ratio in the first consultation, it was evident that there was no target organ damage and her Qrisk3 score was calculated as 3.4%. These results provided reassurance for Jane, but she was keen to engage and prevent any potential complications.

Agreeing treatment

Concordance is only truly practised when the patient's perspectives are valued, shared and used to inform planning ( McKinnon, 2013 ). The trainee advanced nurse practitioner now needed to use the information gained from the consultations to formulate a co-produced and meaningful treatment plan based on the best available evidence ( Diamond-Fox and Bone, 2021 ). Jane understood the risk associated with high blood pressure and was keen to begin medication as soon as possible. NICE guidelines ( 2019 ; 2022 ) advocate the use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blockers in patients under 55 years of age and not of Black African or African-Caribbean origin. However, ACE inhibitors seem to be used as the first-line treatment for hypertensive patients under the age of 55 years ( O'Donovan, 2019 ).

ACE inhibitors directly affect the renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system which plays a central role in regulation of blood pressure ( Porth, 2015 ). Renin is secreted by the juxtaglomerular cells, in the kidneys' nephrons, when there is a decrease in renal perfusion and stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system ( O'Donovan, 2018 ). Renin then combines with angiotensinogen, a circulating plasma globulin from the liver, to form angiotensin I ( Kumar and Clark, 2017 ). Angiotensin I is inactive but, through ACE, an enzyme present in the endothelium of the lungs, it is transformed into angiotensin II ( Kumar and Clark, 2017 ). Angiotensin II is a vasoconstrictor which increases vascular resistance and in turn blood pressure ( Porth, 2015 ) while also stimulating the adrenal gland to produce aldosterone. Aldosterone reduces sodium excretion in the kidneys, thus increasing water reabsorption and therefore blood volume ( Porth, 2015 ). Using an ACE inhibitor prevents angiotensin II formation, which prevents vasoconstriction and stops reabsorption of sodium and water, thus reducing blood pressure.

When any new medication is being considered, providing education is key. This must include what the medication is for, the importance of taking it, any contraindications or interactions with the current medications being taken by the patient and the potential risk of adverse effects ( O'Donovan, 2018 ). Sharing this information with Jane allowed her to weigh up the pros and cons and make an informed choice leading to the creation of an individualised treatment plan.

Jamison (2006) placed great emphasis on sharing information about adverse effects, because patients with hypertension feel well before commencing medications, but taking medication has the potential to cause side effects which can affect adherence. Therefore, the range of side effects were discussed with Jane. These include a persistent, dry non-productive cough, hypotension, hypersensitivity, angioedema and renal impairment with hyperkalaemia ( Hitchings et al, 2019 ). ACE inhibitors have a range of adverse effects and most resolve when treatment is stopped ( Waterfield, 2008 ).

Following discussion with Jane, she proceeded with taking an ACE inhibitor and was encouraged to report any side effects in order to find another more suitable medication and to prevent her hypertension from going untreated. This information was provided verbally and written which is seen as good practice ( Green, 2015 ). Jane was followed up with fortnightly blood pressure recordings and urea and electrolyte checks and her dose of ramipril was increased fortnightly until her blood pressure was under 140/90 mmHg ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ).

Conclusions

Adherence to medications can be difficult to establish and maintain, especially for patients with long-term conditions. This can be particularly challenging for patients with hypertension because they are generally asymptomatic, yet acquire a sick label and start lifelong medication and lifestyle adjustments to prevent complications. Through adopting a concordant approach in practice, the outcome of adherence can be increased. This case study demonstrates how concordant strategies were implemented throughout the consultation to create a therapeutic patient–professional relationship. This optimised the creation of an individualised treatment plan which the patient engaged with and adhered to.

- Hypertension is a growing worldwide problem

- Appropriate clinical assessment, diagnosis and management is key to prevent misdiagnosis

- Long-term conditions are associated with high levels of non-adherence to treatments

- Adopting a concordance approach to practice optimises adherence and promotes positive patient outcomes

CPD reflective questions

- How has this article developed your assessment, diagnosis or management of patients presenting with a high blood pressure?

- What measures can you implement in your practice to enhance a concordant approach?

Clinical Autonomic Dysfunction pp 365–382 Cite as

Sample Case Studies

- Joseph Colombo PhD 5 , 6 ,

- Rohit Arora MD, FACC, FAHA, FACP, FSCAI 7 , 8 ,

- Nicholas L. DePace MD, FACC 9 &

- Aaron I. Vinik MD, PhD, FCP, MACP 10

- First Online: 01 January 2014

1847 Accesses

In this chapter, we discuss some common sample case studies, including hypertension with depression, unexplained dizziness, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN), sleep apnea, atrial fibrillation, cardiac pathology, diabetes, and depression. It is important to remember that the main goal of autonomic assessment and therapy is not to cure disease. While that may happen, the goal is to slow the progression of autonomic dysfunction and to minimize morbidity and mortality risk. This enables the physician to be more aggressive towards the primary disease and to promote and maintain wellness once the primary disease is controlled. For example, autonomic assessment may not cure heart disease, arrhythmia, COPD, diabetes, or Parkinson’s disease; treating documented autonomic dysfunction will lead to relief from dizziness, depression, secondary hypertension, sleep disorder, etc. This leads to reduced medication load, reducing the potential for conflicting or confounding therapies. This also leads to reduced hospitalization and helps to promote reduced healthcare costs for both the patient and the nation while improving outcomes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

See “Possible Therapy Options.”

See the trend plot (Fig. 30.10 , middle graph). Note that the peak sympathetic (red) response to standing (section “F”) is comparable to that for Valsalva (section “D”). The reason why this does not show on the average is that the time duration of the stand is 300 s and that for Valsalva is 90 s. So the stand peaks often are averaged out.

Arora RR, Bulgarelli RJ, Ghosh-Dastidar S, Colombo J. Autonomic mechanisms and therapeutic implications of postural diabetic cardiovascular abnormalities. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2(4):568–71.

Article Google Scholar

Vinik AI, Murray GL. Autonomic neuropathy is treatable. US Endocrinol. 2008;2:82–4.

Google Scholar

Arora RR, Iffrig K, Aysin E, Aysin B, Colombo J. Resting sympathetic/parasympathetic imbalance effects outcomes in geriatric heart failure patients. New Orleans: American College of Cardiology; 2007. 56th Annual Scientific Session.

Arora RR, Iffrig K, Colombo J. Geriatric female longevity associated with elevated parasympathetic tone. Can the same be affected in geriatric males? Presented at the American Autonomic Society’s 17th International Symposium on the Autonomic Nervous System, Rio Grande. Accessed 1–4 Nov 2006.

Waheed A, Ali MA, Jurivich DA, et al. Gender differences in longevity and autonomic function. Presented at the Geriatric Medicine Society Meeting, Chicago. Accessed 3–7 May 2006.

Arora RR, Iffrig K, Aysin E, Aysin B, Colombo J. Geriatric gender differences in parasympathetic tone may modify treatment of geriatric men and women. New Orleans: American College of Cardiology; 2007. 56th Annual Scientific Session.

Pereira E, Baker S, Bulgarelli RJ, Murray G, Arora RR, Colombo J. Gender differences in longevity and sympathovagal balance. Presented at the Cleveland Clinic Heart-Brain Summit, Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, Las Vegas. Accessed 23–24 Sept 2010.

Umetani K, Singer DH, McCraty R, Atkinson M. Twenty-four hour time domain heart rate variability and heart rate: relations to age and gender over nine decades. JACC. 1998;31(3):593–601.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Litchman JH, Bigger Jr JT, Blumenthal JA, et al. Depression and coronary heart disease recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118:1768–75.

Sandroni P, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Singer W, Low PA. Pyridostigmine for treatment of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension: a follow up survey study. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:51–3.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Autonomic Laboratory Department of Cardiology, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Joseph Colombo PhD

ANSAR Medical Technologies, Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA

Department of Medicine, Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center, North Chicago, IL, USA

Rohit Arora MD, FACC, FAHA, FACP, FSCAI

Department of Cardiology, The Chicago Medical School, North Chicago, IL, USA

Department of Cardiology, Hahnemann Hospital Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Nicholas L. DePace MD, FACC

Department of Medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School Strelitz Diabetes Research Center, Norfolk, VA, USA

Aaron I. Vinik MD, PhD, FCP, MACP

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Colombo, J., Arora, R., DePace, N.L., Vinik, A.I. (2015). Sample Case Studies. In: Clinical Autonomic Dysfunction. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07371-2_30

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07371-2_30

Published : 05 July 2014

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-07370-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-07371-2

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Making Best Practice, Every Day Practice

Case study: The hypertensive patient

Working with patients who are not willing to engage fully with healthcare services is a common occurrence. The process requires patience and a focus on providing the patient with full information about their condition and then allowing them to make decisions about their treatment. Here, Dr Terry McCormack (GP and Cardiovascular Lead, North Yorks) describes the approach of his practice to a man with hypertension.

A 57-year old man Mr ‘Hawk’ Ward attends a routine NHS Health Check with a health care assistant (HCA) in the local surgery. He had had no contact with healthcare for many years and was not keen on any interventions. Repeated blood pressure (BP) measurements showed very high BP of 205/91 mmHg. The assessment also showed:

- A strong family history of CV disease (brother

- Smoker 30/day

- Appearance healthy

- Alcohol intake 100 units/week

The HCA immediately referred him to the GP who had a long discussion with him and was able to persuade him to take a blood test and have home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) although he declined ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

He returned to see the practice senior nurse after HBPM and further investigations showed:

- HBPM average of 8 readings (first 2 discounted) 180/95 mmHg

- Total cholesterol 7.2 mmol/L, HDL 1.4 mmol/L, non-HDL 5.8 mmol/L

- QRISK2 36.1

- Liver Function Tests normal

Mr Ward agreed with the senior nurse to stop smoking, excess alcohol intake, adding salt to food, but would not take medication. He reluctantly agreed to make an appointment to see Dr McCormack.

At the GP appointment

- Mr Ward announces that ‘medication is not an option’

- The GP explains all his risks (including the relevance of non-HDL cholesterol and QRISK2 assessment) and then ask him what he would like to do about it.

- Shared, informed decision making explained

- The GP offers ABPM to confirm the diagnosis

After some time spent considering the GPs evidence and advice, the patient decided to accept some medication and was put on amlodipine 5mg.

Current situation

At a later visit Mr Ward’s blood pressure had reduced to 147/84 mmHg. He has cut down on alcohol and was less agitated. He agreed to take atorvastatin 20 mg and is continuing on therapy and has improved his engagement with the practice team. This patient and ongoing approach has produced significant improvements in his condition, lowered his risk of subsequent events and provides promise for ongoing interaction with health care services.

Case study: Nurse COPD assessment

Case study: Painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy

Case study: Statin intolerance in a patient with high cardiovascular risk

Join our community of primary care professionals today, educational partners.

A Patient/Family Care Study on Hypertension

Original bundle.

License bundle

Collections.

- Open access

- Published: 09 April 2024

On-demand mobile hypertension training for primary health care workers in Nigeria: a pilot study

- Joseph Odu 1 ,

- Kufor Osi 1 ,

- Leander Nguyen 2 ,

- Allison Goldstein 1 ,

- Lawrence J. Appel 3 ,

- Kunihiro Matsushita 3 ,

- Dike Ojji 4 ,

- Ikechukwu A. Orji 5 ,

- Morenike Alex-Okoh 6 ,

- Deborah Odoh 6 ,

- Malau Mangai Toma 6 ,

- Chris Ononiwu Elemuwa 7 ,

- Suleiman Lamorde 7 ,

- Hasana Baraya 7 ,

- Mary T. Dewan 8 ,

- Obagha Chijioke 8 ,

- Andrew E. Moran 1 , 2 ,

- Emmanuel Agogo 1 &

- Marshall P. Thomas 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 444 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

133 Accesses

Metrics details

Only one out of every ten Nigerian adults with hypertension has their blood pressure controlled. Health worker training is essential to improve hypertension diagnosis and treatment. In-person training has limitations that mobile, on-demand training might address. This pilot study evaluated a self-paced, case-based, mobile-optimized online training to diagnose and manage hypertension for Nigerian health workers.

Twelve hypertension training modules were developed, based on World Health Organization and Nigerian guidelines. After review by local academic and government partners, the course was piloted by Nigerian health workers at government-owned primary health centers. Primary care physician, nurse, and community health worker participants completed the course on their own smartphones. Before and after the course, hypertension knowledge was evaluated with multiple-choice questions. Learners provided feedback by responding to questions on a Likert scale.

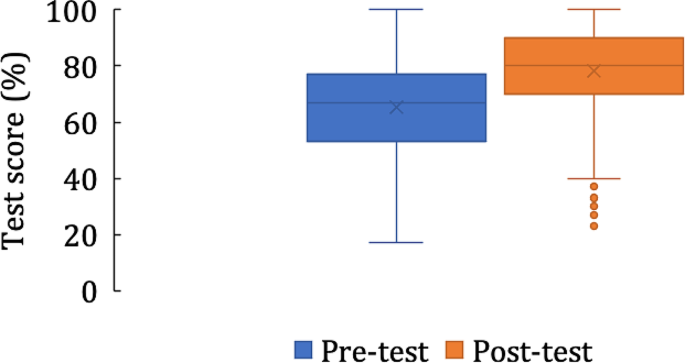

Out of 748 users who sampled the course, 574 enrolled, of whom 431 (75%) completed the course. The average pre-test score of completers was 65.4%, which increased to 78.2% on the post-test ( P < 0.001, paired t-test ). Health workers who were not part of existing hypertension control programs had lower pre-test scores and larger score gains. Most participants (96.1%) agreed that the training was applicable to their work, and nearly all (99.8%) agreed that they enjoyed the training.

Conclusions

An on-demand mobile digital hypertension training increases knowledge of hypertension management among Nigerian health workers. If offered at scale, such courses can be a tool to build health workforce capacity through initial and refresher training on current clinical guidelines in hypertension and other chronic diseases in Nigeria as well as other countries.

Peer Review reports

Hypertension in Nigeria

In Nigeria, cardiovascular disease accounts for 9% of all deaths each year [ 1 ]. Hypertension is a major driver of cardiovascular disease burden, with a prevalence between 32.5% and 38.1% among adults in Nigeria [ 2 , 3 ]. However, access to care and treatment for hypertension in Nigeria is inadequate, with only 12.0–33.6% of hypertensive individuals estimated to receive treatment [ 2 , 3 ]. Moreover, blood pressure control rates are extremely low, ranging from 2.8 to 12.4% [ 2 , 3 ]. Several factors contribute to this situation, including poor detection and management of hypertension at primary health centers (PHCs), a shortage of health workers (HWs), limited knowledge among some HWs, and inadequate equipment and supplies at health facilities [ 4 ].

The Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) has established national targets and developed a roadmap to address the rising burden of non-communicable diseases based on the World Health Organization (WHO) HEARTS hypertension control technical package [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. In collaboration with the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHCDA), WHO, and Resolve to Save Lives, the FMOH launched the Nigerian Hypertension Control Initiative in 2020 [ 8 ]. The initiative aims to improve population-level blood pressure control by strengthening and scaling up screening, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, and health education at the primary health care level.

Nigeria Hypertension Control Initiative strategies include standardizing hypertension treatment with a simple treatment protocol and implementing task shifting and task sharing of hypertension service delivery duties. This approach engages all cadres of PHC staff in hypertension management. The government is currently conducting in-person training of HWs in PHCs across the country using Nigeria-specific guidelines. However, traditional in-person training has several limitations.

Current gaps in health worker training

Low- and middle-income countries face significant challenges in establishing and maintaining a skilled health workforce to combat the growing burden of non-communicable diseases and other health challenges [ 9 ]. Conventional HW in-service training methods have not kept up with the rapid evolution of clinical guidelines and best practices [ 10 , 11 ]. Nigeria has over 30,000 PHCs that are staffed by hundreds of thousands of HWs [ 12 ]. Providing in-person training to upskill the entire PHC workforce on new hypertension guidelines would be a costly and logistically challenging endeavor. The system of pre-service HW training is also under strain. Meanwhile, developing countries continue to face severe shortages of HWs, particularly in rural and underserved areas [ 13 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the need for innovative approaches to HW training. The pandemic significantly disrupted traditional training methods like in-person seminars and workshops [ 14 , 15 ]. Online training is emerging as a viable option to provide health professionals with the flexibility to study at their own pace and from any location while minimizing the risk of the spread of infection [ 14 ].

Present study

Our team previously piloted and evaluated a short, mobile-optimized online infection prevention and control course with HWs in Nigeria [ 15 ]. We found that the course had high completion rates and strong learning gains. Based on the success of the online infection prevention and control course, we applied a similar methodology to train HWs based in PHCs in Nigeria on new national hypertension diagnosis and management guidelines.

Program design informed by learning science

We expanded on the learning approach we developed in previous pilots of an infection prevention and control course in Nigeria [ 15 ]. We used insights from the learning sciences and our understanding of HWs’ learning and technology needs to develop a set of design principles. These include:

Structuring the learning around clinical cases that are directly relevant to HWs’ practice. This approach can boost HWs’ interest and motivation [ 16 ]. It also allows HWs to directly apply experiences and knowledge stored in long-term memory.

Engaging HWs through continuous low-stakes assessments (quiz questions) with constructive feedback. These assessments are intended to promote learning rather than merely evaluate learners [ 17 ]. Each question is accompanied by a brief explanation, which improves learners’ subjective experience [ 18 ].

Developing modules that repeat and expand upon key concepts, harnessing the benefits of spaced repetition to facilitate learning [ 19 ].

Focusing on essential content and eliminating nonessential material, which improves factual retention [ 20 ].

Teaching basic knowledge and skills, which may be more appropriate for online HW training than teaching advanced clinical practices [ 16 ].

Offering short courses, which increases course completion [ 21 ].

Implementing a user-friendly and well-organized learning experience, which reduces frustration and maintains learners’ self-efficacy [ 22 ].

Requiring learners to complete a short “sample” module to enroll in the full course. Some learners who sign up for free online courses do not intend to complete them [ 23 ], so this small commitment helps to ensure that those who enroll are invested in the learning.

Evaluation methodology

To assess short-term knowledge gains we used a pre-/post-test design. The 10-question multiple choice test was given once at the beginning of the course, with the same set of questions given again at the end of the course. Questions were presented in the same order each time, with the order of answers randomized. Although the pre-/post-test emphasized the content taught in the course, the pre-/post-test questions were not repeated in other modules of the course. Learners could only take each of these tests once and no minimum score was required on the test to advance in the course. Learners received minimal feedback (they could see the correct answers but there were no explanations given) after submitting their answers. To evaluate learners’ reactions, HWs answered a short survey at the beginning of the last module of the course. This survey included the net promoter score question, “How likely is it that you would recommend this course to a friend or colleague?” The survey also included two 5-point Likert scale questions assessing learners’ enjoyment of the course and its relevance to their work. Learners provided basic demographic data by answering a short survey at the end of the first (sample) module of the course. We based the survey questions (supplementary file 1 ) on questions we used in previous courses [ 15 ], with some additions and refinements to match the context of this course.

Collaborative course development

The development of the course was a collaborative and coordinated process that involved multiple government stakeholders, academic partners, and non-governmental organizations. These entities included the FMOH, NPHCDA, WHO-Nigeria Office, Johns Hopkins University, the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital’s Hypertension Treatment in Nigeria Project team, and Resolve to Save Lives.

The FMOH coordinated the co-creation of course materials aligned with the National Hypertension Treatment Guideline, developed in 2021. Prior to the pilot study, four hypertension program managers from WHO, NPHCDA, the Hypertension Treatment in Nigeria Project, and RTSL, three FMOH policymakers, and four clinical experts reviewed the course to ensure alignment with local guidelines and cultural context. An example module from the course is provided in supplementary file 2 . After the content was reviewed, the course was built on our learning management system and quality assurance was conducted by the team at Resolve to Save Lives.

Next, we conducted user testing at a PHC in Abuja to ensure the course’s usability and effectiveness. Four HWs from different cadres took part in the testing, including a medical doctor, a nurse/midwife, a community health extension worker (CHEW), and a pharmacy technician. HWs were selected who had a smartphone, an email account, and access to cellular data or Wi-Fi internet at the testing site. We carried out individual user testing sessions with each HW. Throughout these sessions, we offered an overview and context for the online hypertension course, secured consent from the participants, and clarified the procedure for accessing the course. The HW then received a text message with a link to the course and accessed selected modules on their mobile device. They were encouraged to provide feedback on their progress, including difficulties encountered, observations, and suggestions. The results of user acceptance testing were used to improve the course content and navigation for the subsequent pilot.

Course dissemination

Enrollment in the pilot online training was open from February 13 to April 20, 2023. Learners who enrolled had access through May 4, 2023 to ensure that they had enough time to complete the course. The FMOH, NPHCDA, the Hypertension Treatment in Nigeria Project manager, and state non-communicable disease coordinators distributed the link to the online course to HWs at Nigeria Hypertension Control Initiative facilities, hypertension treatment in Nigeria project facilities, and other facilities implementing hypertension control programs. The link was primarily shared via email and WhatsApp. The target audiences included doctors, nurses, and community health workers at PHCs who care for hypertensive patients. Due to task shifting and task sharing, all of these HW cadres contribute to hypertension diagnosis and management in PHCs in Nigeria.

Technologies used