An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.14(12); 2022 Dec

A Comprehensive Review on Postpartum Depression

Om suryawanshi, iv.

1 Obstetrics and Gynecology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, IND

Sandhya Pajai

One of the most common psychological effects following childbirth is postpartum depression. Postpartum depression (PPD) has a significant negative impact on the child's emotional, mental as well as intellectual development if left untreated, which can later have long-term complications. Later in life, it also results in the mother developing obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety. Many psychological risk factors are linked with PPD. The pathophysiology of the development of PPD is explained by different models like biological, psychological, integrated, and evolutionary models, which relate the result of the condition with particular conditions and factors. This article also explains the role of methyldopa as a medication used during pregnancy and the postpartum phase with the development of PPD. There are different mechanisms by which methyldopa causes depression. The large-scale screening of the condition can be done by Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). The diagnosis can be made by clinical assessment, simple self-report instruments, and questionnaires provided to mothers. Currently, there has not been any specific treatment for PPD, but selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) like sertraline are effective in acute management. Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine are serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors used for the relief of symptoms. The SSRI and tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) used in combination have a prophylactic role in PPD. Nowadays, women prefer psychological therapies, complementary health practices, and neuromodulatory interventions like electroconvulsive therapy more than previous pharmacological treatments of depression. Allopregnanolone drug made into sterile solution brexanolone leads to a rapid decline of PPD symptoms. PPD is a common and severe disorder that affects many mothers following childbirth but is ignored and not given much importance. Later it affects the child's psychological and intellectual abilities and mother-child bonding. We can easily prevent it by early diagnosis and timely care and management of the mother. Understanding the underlying pathophysiology would also go a long way in preventing and managing the disorder.

Introduction and background

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a significant mental health constraint in females, which has an effect on nearly 13-19% of the females who newly attained motherhood [ 1 ]. PPD is identified by a continuous feeling of a low state of mind in new mothers, followed by sad feelings, less worthy, and despondence. It differs from baby blues, a short-lived period of emotional disruption that includes weeping, irritability, sleep troubles, and anxiety. It is identified and felt by every four in five women in very few days after child delivery and mostly remits by 10 days [ 1 , 2 ]. Currently, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) has classified depression associated with the onset of childbirth as starting in pregnancy or by the first month of postpartum [ 3 ]. According to the International Classification of Disease (ICD), postpartum depression is labeled as one beginning by the first six weeks of the postpartum phase [ 4 ]. Many research studies have further revised the guidelines for the first six months following childbirth, while few use the time frame for up to the first year following the period of delivery for the beginning of PPD [ 5 ].

In most aspects, PPD has many likely features with depression which occur at other times in a mother's life; in some prospects, it has few differences as many significant changes occur during pregnancy and the postpartum phase [ 1 , 6 ]. In approximation, nearly 80% of postpartum women face the prodrome of emotional disturbances in the first few days following childbirth [ 7 ]. More of, a large proportion of postpartum women following pregnancy experience symptoms attributed to depression-like disturbed appetite, lack of sleep, and low energy levels for working [ 8 ]. The above factors make it hard to separately identify the commonly occurring symptoms following childbirth and new infant care from those of a depressive condition. Sometimes the phase of postpartum depression in nearly 30% of women can continue for two years postpartum [ 9 ], while 50% of women have major depression throughout in which the course of depression may vary and have stable moderate depression, major stable depression, or repetitive intervals of significant depression [ 10 ]. A comparison of symptoms between postpartum blues, postpartum depression, and postpartum psychosis is shown in Table Table1 1 .

The table is adapted from Fishbein (2017) (Open source) [ 11 ].

Psychological risk factors of PPD

The risk factors can be grouped based on the strength of association with PPD. Depression and anxiety in pregnancy, postpartum blues, history of depression, neuroticism, excessive stress indulging life events, poor marital relations, lack of social support, and low self-esteem are strongly associated with postpartum depression [ 12 ]. On the other side, low socioeconomic status, single marital status, unwanted pregnancy, obstetrical stressors, and grieving infant temperament are reported to have a relatively weaker association [ 13 , 14 ]. The attitude of a mother [ 15 ] and her experience of different related complications like preterm delivery, prenatal hospitalization, emergency cesarean section, preeclampsia, and deceased infant health [ 16 ] are shown to have increased risk of developing PPD [ 17 - 19 ]. The above risk factors are more strongly associated with social and psychological aspects than biological aspects. A bar chart showing percentage of factors attributed to PPD is shown in Figure Figure1 1 .

The image is adapted from Shriraam et al. (2019) (Open source) [ 20 ].

Pathophysiology of PPD

The exact mechanism for the development of postpartum depression is still unknown. There are many different models and theories explaining the condition's cause over time. Biological model explains the development of the condition due to the drastic and sudden decrease in many pregnancy hormones like progesterone, estradiol, and cortisol. In the withdrawal model, stress and reproductive hormones increase in pregnancy and fall drastically during childbirth and in the postpartum phase, which leads to dysregulation of the system and causes PPD [ 21 - 23 ]. However, they fail to explain the mechanism of hormone withdrawal with depression and the depressive symptoms which begin during pregnancy. The depression model states the association of PPD with the stress hormones dysregulation, mainly cortisol [ 24 ]. There is a suggestion from a few recent reviews for the role of dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis in the causation of PPD [ 25 , 26 ]. Declined dopaminergic regulation may also have a role in PPD [ 27 ]. Many neuroendocrine changes in pregnancy can also affect PPD development, including inhibited Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling and low levels of allopregnanolone [ 28 - 30 ].

Psychological models focus mainly on the effect of pregnancy, childbirth, and new parenthood as the major stress factors which cause PPD symptoms in women. There has been much support in the psychological literature [ 31 ]. Integrated models bridge the above and state the role of both biological factors, such as stress causing PPD symptoms in women having genetic and hormonal susceptibility [ 23 ]. Evolutionary models have an evolutionary perspective in which the PPD is believed to be due to human civilization because of psychological adaptation in the course of human evolution. A "mismatch hypothesis" of PPD was recently proposed by Hahn-Holbrook and Haselton that suggests that PPD might be a "disease of civilization" due to significant cultural shifts over the past century that have resulted in substantial deviations from typical human evolutionary lifestyles and the current high incidence rate [ 32 ].

Role of methyldopa in the induction of postpartum depression

Methyldopa, an agonist of presynaptic alpha-2 adrenergic receptors, prevents neurons from releasing norepinephrine and, consequently, inhibits the sympathetic nervous system. This medication is actively transported to the brain as an amino acid, where it is metabolized into the active form, -methyl norepinephrine. In the biosynthesis pathway of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine, methyldopa replaces dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), forming inactive structures of neurotransmitters. Methyldopa blocks the baroreceptor signaling pathway by activating presynaptic 2-adrenergic receptors and altering a single nucleus through inactive neurotransmitters [ 33 ].

Methyldopa significantly raises the level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is both an angiogenic factor and a neurotrophic agent. Although neuronal function alteration is probably more complex, VEGF dysfunctions neurogenesis and the functioning of sustained neurons by decreasing serotonin concentration and catecholamine levels due to this property. These changes characterize the neurotrophic depression model.

Methyldopa reduces cerebral blood flow by impairing baroreceptor signaling pathways and decreasing sympathetic system stimulation. Impaired neuronal function, cognitive decline, and depression are all consequences of decreased cerebral blood flow, particularly in the orbitofrontal cortex. These modifications characterize the vascular model of depression.

Methyldopa raises nitric oxide (NO) levels by reducing nitric-compound excretion in the kidneys and increasing endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression. In high concentrations, NO is neurotoxic, causing mild inflammation and decreased levels of cofactors (tryptophan, tetrahydrobiopterin, and others).and decreased levels of catecholamines and serotonin; consequently, elevated NO levels can cause depression. Methyldopa lowers dopamine concentration by interfering with its production. The excretion of prolactin is controlled by dopamine. Low dopamine levels cause hyperprolactinemia, which impairs sexual behavior and contributes to depression. Disruption of the reward system is an integral part of the development of depression. Methyldopa lowers dopamine levels, a neurotransmitter essential to the reward system. Depression is brought on by methyl-dopa through this mechanism.

In light of the preceding, taking methyldopa can cause depression. Because methyl-dopa is the first-line treatment for preeclampsia and hypertension in pregnancy and because mood swings and sluggishness are common after labor, this side effect of methyldopa is more likely to occur in pregnant women. To fully understand the problem and provide appropriate mental health care for patients, extensive prospective studies evaluating depression that occurs during the treatment of methyldopa and identifying potential prevention and treatment are required in light of the solid theoretical foundation.

Methyldopa may be considered a depression risk factor, inducer in postpartum depression, with the cause of maternal blues in light of the preceding data. This process's pathomechanism is intricate and classified into following five categories: (1) neurotrophic alteration, (2) reduction of cerebral blood flow, (3) neurotoxicity induced by NO, (4) high levels of prolactin, and (5) reward system impairment (Figure (Figure2 2 ).

The image is adapted from Wicinski et al. (2020) (CC BY 4.0) [ 33 ].

Diagnosis of PPD

The criteria for when PPD first appears is still debatable [ 34 ]. The United States Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) includes episodes that begin during pregnancy and last for six months after birth [ 35 ]. Postpartum depression (PPD) has been estimated to occur up to one year after childbirth in clinical practice and published research. For example, DSM-IV’s Structured Clinical Interview can be used to diagnose PPD Simple self-report instruments like questionnaires have been used for many clinical assessments. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is reliable, validated, frequently more practical, and economical in large-scale screenings for PPD risk and is the most well-known and widely used [ 36 ]. To lessen the burden placed on common symptoms experienced by most new mothers, EPDS emphasizes psychic depression symptoms. Two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) and nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) questionnaire-based screening tools are familiar. The first two items of the PHQ-9 can be found in PHQ-2. A typical score of 10 or higher on the EPDS or PHQ-9 [ 37 - 40 ] is used as the threshold for being positive for PPD Many brief E.P.D.S. subscales, including three-item, seven-item, and -item subscales, have also been developed [ 41 ]. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), which isn’t explicitly made for PPD, is one of the other screening tools [ 42 ]. HAM-D's reliability varies significantly between 0.46 and 0.98 in various evaluations [ 43 ]. The Bipolar Spectrum Diagnostic Scale (BSDS) for bipolar disorders (BD) and other scales for diagnosis of related mood disorders may also be functional in the perinatal period [ 44 ].

Present-day treatment options of PPD and its constraints

There are many therapeutic interventions in the treatment of PPD, most adapted from the treatment of the major depressive disorder (MDD), as to date, there aren't any pharmacological therapies explicitly approved for PPD

Acute Treatment

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI): The primitive line treatment for moderate to severe PPD by use of an SSRI. Among all clinical trial drugs, Sertraline is the most effective drug among SSRIs for treating PPD [ 45 ]. De Crescenzo and colleagues conducted a systematic review in which they found psychotherapy, SSRIs, and Nortriptyline are adequate for the acute treatment of PPD [ 46 ]. However, insufficiently proven studies clearly distinguish one remedy from another.

Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and antidepressants: There hasn't been much-randomized control trials (RCT) trial data for SNRIs and antidepressants. Open-label trials recommend venlafaxine [ 47 ] and desvenlafaxine [ 48 ] to relieve symptoms.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI): Till today, nortriptyline is one TCA used for PPD [ 49 ]. There are not much RCT-level data for MAOI.

Prophylactic Treatment

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCA's): The risk of recurrence for women who have previously experienced PPD is approximately 25% [ 50 ]. To conclude the efficacy of antidepressants in preventing PPD, a newly published Cochrane review found that additional studies involving more participants are required [ 51 ].

Psychotherapies, Complementary Health Practices, and Neuromodulatory Interventions

When considering antidepressant treatment, women having PPD experience mild to high rates of decisional conflict, particularly during pregnancy [ 52 ], and many prefer psychotherapies to pharmacotherapies [ 53 ]. Nearly 26-75% of pregnant women worldwide use complementary health practices due to their significant health-related advantages [ 54 ]. In the United States, 54% of women who suffer from depression say they have used complementary health practices in the past year [ 55 ]. In more severe and remitting cases of postpartum depression (PPD) and postpartum psychosis, an important neuromodulatory option is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Compared to treatment for non-postpartum depression or psychosis, ECT is said to have a higher response rate [ 56 ]. There are no RCT-level data for using ECT to treat PPD, despite the publication of guidelines for its use during Pregnancy [ 57 ]. For the treatment of PPD, additional neuromodulatory methods, such as transcranial direct current stimulation (TCCS) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are in their initial trial stages [ 58 - 62 ]. Other non-invasive neuromodulation interventions and the effectiveness of ECT versus pharmacotherapy in severe PPD should be subject to additional RCT.

Implications for novel pharmacological treatment

A clinical study has used intravenous preparations for endogenous allopregnanolone CNS drugs due to its less oral bioavailability and excessive in vivo clearance. Allopregnanolone given intravenously has been shown to cause sedation and decreased saccadic eye velocity, with women experiencing these effects more than men [ 63 ]. Some women who receive intravenous allopregnanolone may experience only episodic and not semantic or working memory impairment [ 64 ]. Acute intravenous administration of allopregnanolone does not affect the startle response or prepulse inhibition of the startle reaction, indicating that it does not have anxiolytic effects on healthy women [ 65 ]. Allopregnanolone may regulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis through GABA-A receptor modulation, as evidenced by the fact that intravenous administration in healthy women during the follicular phase of a menstrual cycle is linked with decreased plasma concentration of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone but not plasma levels of estradiol or progesterone [ 66 ]. Investigation of synthetic Non-allogenic steroids (NAS) and their analogs as primary treatments for PPD is supported by the evidence mentioned above that NAS and GABA play a role in the pathophysiology of PPD Brexanolone (USAN) was developed by Sage Therapeutics, formerly known as SAGE-547 Injection), a proprietary, soluble synthetic allopregnanolone intravenous preparation. Brexanolone, which is a sterile solution of 5 mg/mL allopregnanolone in 250 mg/mL sulfobutylether-cyclodextrin buffered with citrate and diluted until it is isotonic with sterile water [ 67 ]. Brexanolone causes potent, dose-dependent activation of GABA-mediated currents in whole-cell patch electrophysiology studies. Studies on drug interactions have shown that co-administration of brexanolone can alter the metabolic rate of CYP2C9 substrates. Brexanolone in PPD was the subject of the latest series of open-label and few RCTs, which are placebo-controlled that demonstrated a rapid decline in PPD symptoms.

Consequences of PPD

There are few denotations related to women who experience postpartum depression being more likely to have comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety than women who experience depression at other times in their lives [ 68 ]. Postpartum depression is linked to various outcomes in other areas and an increased risk of comorbid disorders [ 69 ]. There have been reports of adverse long-term effects on infants' social, emotional, intellectual, and physical development [ 70 ]. Postpartum depression-afflicted mothers' children may also be more likely to have intellectual disabilities and psychosocial, emotional, or behavioral problems [ 71 ]. Deficient parenting and parental safety practices are also linked to postpartum depression and difficulties in bonding and mother-child interactions. Research must identify the significant risk factors and protective factors for postpartum depression because of the potentially devastating effects on the mother, the child, and their family postpartum depression.

Conclusions

PPD is a disorder that can be crippling and common. There are several effective pharmacological therapies, psychological therapies, psychosocial, and neuromodulation intercession, but the majority are understudied, particularly in RCT. Sadly, there is a significant underutilization of available treatments in the community. Even though PPD is now more readily discussed, a considerable stigma exists against few women seeking treatment. In low socioeconomic countries, mental health might not be prioritized; women may have restrictions in reaching out to providers specially trained in perinatal mental health even when they seek treatment. Because of the complexity of treatment modalities of peripartum psychiatric illness demands integrative work among multiple health service providers, including obstetrics, psychiatry, pediatrics, and nursing/midwifery. Reproductive psychiatric tutorials should be spread widely within the discipline of psychiatry in residency and fellowship programs.

It is necessary to develop novel therapeutics that specifically target the disorder's underlying pathophysiology and expand access to the treatments that are already in place and improve the quality of those treatments. The underlying neurobiology of PPD is still poorly understood, despite increased research into its causes. There is mounting evidence that psychiatric disorders are neural network disorders characterized by complex, multimodal patterns of neurobiological abnormalities. As a result, there is a pressing need for additional research into the underlying mechanisms of these disorders. We can detect, diagnose, and treat PPD more effectively during pregnancy and postpartum if we learn more about the neurobiology of PPD.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

Exploring predictors and prevalence of postpartum depression among mothers: Multinational study

- Samar A. Amer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9475-6372 1 ,

- Nahla A. Zaitoun ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5274-6061 2 ,

- Heba A. Abdelsalam 3 ,

- Abdallah Abbas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5101-5972 4 ,

- Mohamed Sh Ramadan 5 ,

- Hassan M. Ayal 6 ,

- Samaher Edhah Ahmed Ba-Gais 7 ,

- Nawal Mahboob Basha 8 ,

- Abdulrahman Allahham 9 ,

- Emmanuael Boateng Agyenim 10 &

- Walid Amin Al-Shroby 11

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1308 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

345 Accesses

Metrics details

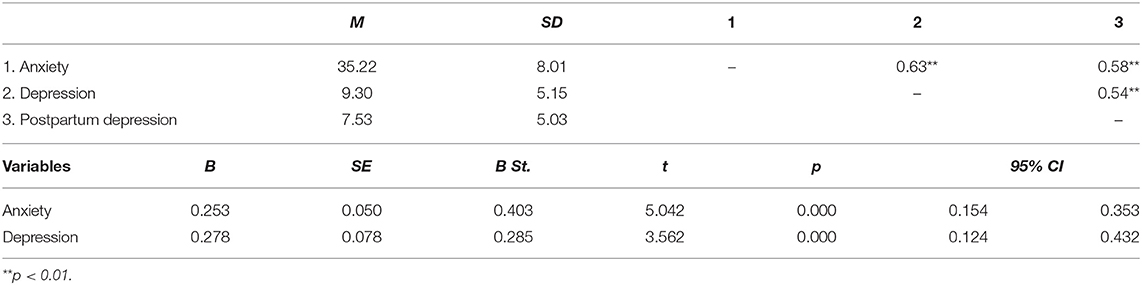

Postpartum depression (PPD) affects around 10% of women, or 1 in 7 women, after giving birth. Undiagnosed PPD was observed among 50% of mothers. PPD has an unfavorable relationship with women’s functioning, marital and personal relationships, the quality of the mother-infant connection, and the social, behavioral, and cognitive development of children. We aim to determine the frequency of PPD and explore associated determinants or predictors (demographic, obstetric, infant-related, and psychosocial factors) and coping strategies from June to August 2023 in six countries.

An analytical cross-sectional study included a total of 674 mothers who visited primary health care centers (PHCs) in Egypt, Yemen, Iraq, India, Ghana, and Syria. They were asked to complete self-administered assessments using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). The data underwent logistic regression analysis using SPSS-IBM 27 to list potential factors that could predict PPD.

The overall frequency of PPD in the total sample was 92(13.6%). It ranged from 2.3% in Syria to 26% in Ghana. Only 42 (6.2%) were diagnosed. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed there were significant predictors of PPD. These factors included having unhealthy baby adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 11.685, 95% CI: 1.405–97.139, p = 0.023), having a precious baby (aOR 7.717, 95% CI: 1.822–32.689, p = 0.006), who don’t receive support (aOR 9.784, 95% CI: 5.373–17.816, p = 0.001), and those who are suffering from PPD. However, being married and comfortable discussing mental health with family relatives are significant protective factors (aOR = 0.141 (95% CI: 0.04–0.494; p = 0.002) and (aOR = 0.369, 95% CI: 0.146–0.933, p = 0.035), respectively.

The frequency of PPD among the mothers varied significantly across different countries. PPD has many protective and potential factors. We recommend further research and screenings of PPD for all mothers to promote the well-being of the mothers and create a favorable environment for the newborn and all family members.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) is among the most prevalent mental health issues [ 1 ]. The onset of depressive episodes after childbirth occurs at a pivotal point in a woman’s life and can last for an extended period of 3 to 6 months; however, this varies based on several factors [ 2 ]. PPD can develop at any time within the first year after childbirth and last for years [ 2 ]. It refers to depressive symptoms that a mother experiences during the postpartum period, which are vastly different from “baby blues,” which many mothers experience within three to five days after the birth of their child [ 3 ].

Depressive episodes are twice as likely to occur during pregnancy compared to other times in a woman’s life, and they frequently go undetected and untreated [ 4 ]. According to estimates, almost 50% of mothers with PPD go undiagnosed [ 4 ]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria for PPD include mood instability, loss of interest, feelings of guilt, sleep disturbances, sleep disorders, and changes in appetite [ 5 ], as well as decreased libido, crying spells, anxiety, irritability, feelings of isolation, mental liability, thoughts of hurting oneself and/or the infant, and even suicidal ideation [ 6 ].

Approximately 1 in 10 women will experience PPD after giving birth, with some studies reporting 1 in 7 women [ 7 ]. Globally, the prevalence of PPD is estimated to be 17.22% (95% CI: 16.00–18.05) [ 4 ], with a prevalence of up to 15% in the previous year in eighty different countries or regions [ 1 ]. This estimate is lower than the 19% prevalence rate of PPD found in studies from low- and middle-income countries and higher than the 13% prevalence rate (95% CI: 12.3–13.4%) stated in a different meta-analysis of data from high-income countries [ 8 ].

The occurrence of postpartum depression is influenced by various factors, including social aspects like marital status, education level, lack of social support, violence, and financial difficulties, as well as other factors such as maternal age (particularly among younger women), obstetric stressors, parity, and unplanned pregnancy [ 4 ]. When a mother experiences depression, she may face challenges in forming a satisfying bond with her child, which can negatively affect both her partner and the emotional and cognitive development of infants and adolescents [ 4 ]. As a result, adverse effects may be observed in children during their toddlerhood, preschool years, and beyond [ 9 ].

Around one in seven women can develop PPD [ 7 ]. While women experiencing baby blues tend to recover quickly, PPD tends to last longer and severely affects women’s ability to return to normal function. PPD affects the mother and her relationship with the infant [ 7 ]. The prevalence of postpartum depression varies depending on the assessment method, timing of assessment, and cultural disparities among countries [ 7 ]. To address these aspects, we conducted a cross-sectional study focusing on mothers who gave birth within the previous 18 months. Objectives: to determine the frequency of PPD and explore associated determinants or predictors, including demographic, obstetric, infant-related, and psychosocial factors, and coping strategies from June to August 2023 in six countries.

Study design and participants

This is an analytical cross-sectional design and involved 674 mothers during the childbearing period (CBP) from six countries, based on the authors working settings, namely Egypt, Syria, Yemen, Ghana, India, and Iraq. It was conducted from June to August 2023. It involved all mothers who gave birth within the previous 18 months, citizens of one of the targeted countries, and those older than 18 years and less than 40 years. Women who visited for a routine postpartum follow-up visit and immunization of their newborns were surveyed.

Multiple pregnancies, illiteracy, or anyone deemed unfit to participate in accordance with healthcare authorities, mothers who couldn’t access or use the Internet, mothers who couldn’t read or speak Arabic or English and couldn’t deal with the online platform or smart devices, mothers whose babies were diagnosed with serious health problems, were stillborn, or experienced intrauterine fetal death, and participants with complicated medical, mental, or psychological disorders that interfered with completing the questionnaire were all exclusion criteria. There were no incentives offered to encourage participation.

Sample size and techniques

The sample size was estimated according to the following equation: n = Z 2 P (1-P)/d 2 . This calculation was based on the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2020 of 17% as the worldwide prevalence of PPD and 12% as the worldwide incidence of PPD, as well as a 5% precision percentage, 80% power of the study, a 95% confidence level, and an 80% response rate [ 11 ]. The total calculated sample size is 675. The sample was diverse in terms of nationality, with the majority being Egyptian (16.3%), followed by Yemeni (24.3%) and Indian (19.1%), based on many factors discussed in the limitation section.

The sampling process for recruiting mothers utilized a multistage approach. Two governorates were randomly selected from each country. Moreover, we selected one rural and one urban area from each governorate. Through random selection, participants were chosen for the study. Popular and officially recognized online platforms, including websites and social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp groups, and registered emails across various health centers, were utilized for reaching out to participants. Furthermore, a community-based sample was obtained from different public locations, including well-baby clinics, PHCs, and family planning units.

Mothers completed the questionnaire using either tablets or cellphones provided by the data collectors or by scanning the QR code. All questions were mandatory to prevent incomplete forms. Once they provided their informed consent, they received the questionnaire, which they completed and submitted. To enhance the response rate, reminder messages and follow-up communications were employed until the desired sample size was achieved or until the end of August. To avoid seasonal affective disorders, the meteorological autumn season began on the 1st day of September, which may be associated with Autum depressive symptoms that may confound or affect our results.

Data collection tool

Questionnaire development and structure.

The questionnaire was developed and adapted based on data obtained from previous studies [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Initially, it was created in English and subsequently translated into Arabic. To ensure accuracy, a bilingual panel consisting of two healthcare experts and an externally qualified medical translator translated the English version into Arabic. Additionally, two English-speaking translators performed a back translation, and the original panel was consulted if any concerns arose.

Questionnaire validation

To collect the data, an online, self-administered questionnaire was utilized, designed in Arabic with a well-structured format. We conducted an assessment of the questionnaire’s reliability and validity to ensure a consistent interpretation of the questions. The questionnaire underwent validation by psychiatrists, obstetricians, and gynecologists. Furthermore, in a pilot study involving 20 women of CBA, the questionnaire’s clarity and comprehensibility were evaluated. It is important to note that the findings from the pilot study were not included in our main study.

The participants were asked to rate the questionnaire’s organization, clarity, and length, as well as provide a general opinion. Following that, certain questions were revised in light of their input. To check for reliability and reproducibility, the questionnaire was tested again on the same people one week later. The final data analysis will not include the data collected during the pilot test. We calculated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 for the questionnaire.

The structure of the questionnaire

After giving their permission to take part in the study. The questionnaire consisted of the following sections:

Study information and electronic solicitation of informed consent.

Demographic and health-related factors: age, gender, place of residence, educational level, occupation, marital status, weight, height, and the fees of access to healthcare services.

Obstetric history: number of pregnancies, gravida, history of abortions, number of live children, history of dead children, inter-pregnancy space (y), current pregnancy status, type of the last delivery, weight gain during pregnancy (kg), baby age (months), premature labor, healthy baby, baby admitted to the NICU, Feeding difficulties, pregnancy problems, postnatal problems, and natal problems The nature of baby feeding.

Assessment of postpartum depression (PPD) levels using the Edinburgh 10-question scale: This scale is a simple and effective screening tool for identifying individuals at risk of perinatal depression. The EPDS (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale) is a valuable instrument that helps identify the likelihood of a mother experiencing depressive symptoms of varying severity. A score exceeding 13 indicates an increased probability of a depressive illness. However, clinical discretion should not be disregarded when interpreting the EPDS score. This scale captures the mother’s feelings over the past week, and in cases of uncertainty, it may be beneficial to repeat the assessment after two weeks. It is important to note that this scale is not capable of identifying mothers with anxiety disorders, phobias, or personality disorders.

For Questions 1, 2, and 4 (without asterisks): Scores range from 0 to 3, with the top box assigned a score of 0 and the bottom box assigned a score of 3. For Questions 3 and 5–10 (with asterisks): Scores are reversed, with the top box assigned a score of 3 and the bottom box assigned a score of 0. The maximum score achievable is 30, and a probability of depression is considered when the score is 10 or higher. It is important to always consider item 10, which pertains to suicidal ideation [ 12 ].

Psychological and social characteristics: received support or treatment for PPD, awareness of symptoms and risk factors, experienced cultural stigma or judgment about PPD in the community, suffer from any disease or mental or psychiatric disorder, have you ever been diagnosed with PPD, problems with the husband, and financial problems.

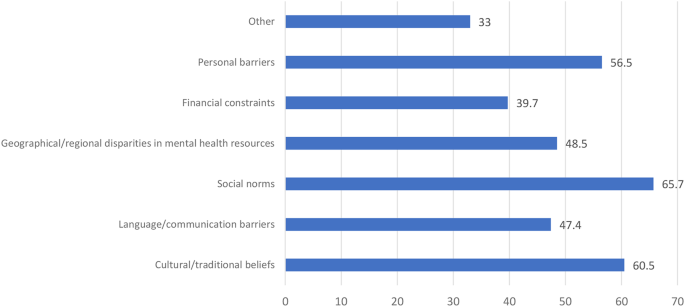

Coping strategies and causes for not receiving the treatment and reactions to PPD, in descending order: social norms, cultural or traditional beliefs, personal barriers, 48.5% geographical or regional disparities in mental health resources, language or communication barriers, and financial constraints.

Statistical analysis

The collected data was computerized and statistically analyzed using the SPSS program (Statistical Package for Social Science), version 27. The data was tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Walk test. Qualitative data was represented as frequencies and relative percentages. Quantitative data was expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation) if it was normally distributed; otherwise, median and interquartile range (IQR) were used. The Mann-Whitney test (MW) was used to calculate the difference between quantitative variables in two groups for non-parametric variables. Correlation analysis (using Spearman’s method) was used to assess the relationship between two nonparametric quantitative variables. All results were considered statistically significant when the significant probability was < 0.05. The chi-square test (χ 2 ) and Fisher exact were used to calculate the difference between qualitative variables.

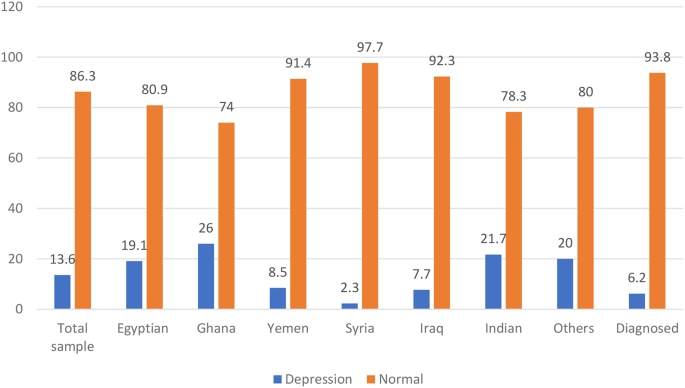

The frequency of PPD among mothers (Fig. 1 )

The frequency of PPD among the studied mothers

The frequency of PPD in the total sample using the Edinburgh 10-question scale was 13.5% (Table S1) and 92 (13.6%). Which significantly ( p = 0.001) varied across different countries, being highest among Ghana mothers 13 (26.0%) out of 50 and Indians 28 (21.7%) out of 129. Egyptian 21 (19.1) out of 110, Yemen 14 (8.5%) out of 164, Iraq 13 (7.7%) out of 168, and Syria 1 (2.3%) out of 43 in descending order. Nationality is also significantly associated with PPD ( p = 0.001).

Demographic, and health-related characteristics and their association with PPD (Table 1 )

The study included 674 participants. The median age was 27 years, with 407 (60.3%) of participants falling in the >25 to 40-year-old age group. The majority of participants were married, 650 (96.4%), had sufficient monthly income, 449 (66.6%), 498 (73.9%), had at least a preparatory or high school level of education, and were urban. Regarding health-related factors, 270 (40.01%) smoked, 645 (95.7%) smoked, 365 (54.2%) got the COVID-19 vaccine, and 297 (44.1%) got COVID-19. Moreover, 557 (82.6%) had no comorbidities, 623 (92.4%) had no psychiatric illness or family history, and they charged for health care services for themselves 494 (73.3%).

PPD is significant ( p < 0.05). Higher among single or widowed women 9 (56.3%) and mothers who had both medical, mental, or psychological problems 2 (66.7%), with ex-cigarette smoking 5 (35.7%) ( p = 0.033), alcohol consumption ( p = 0.022) and mothers were charged for the health care services for themselves 59 (11.9%).

Obstetric, current pregnancy, and infant-related characteristics and their association with PPD (Table 2 )

The majority of the studied mothers were on no hormonal treatment or contraceptive pills 411 (60.9%), the current pregnancy was unplanned and wanted 311 (46.1%), they gained 10 ≥ kg 463 (68.6%), 412 (61.1%) delivered vaginal, a healthy baby 613 (90.9%), and, on breastfeeding, only 325 (48.2%).

There was a significant ( P < 0.05) association observed between PPD, which was significantly higher among mothers on contraceptive methods, and those who had 1–2 live births (76.1%) and mothers who had interpregnancy space for less than 2 years. 86 (93.5%), and those who had a history of dead children. Moreover, among those who had postnatal problems (27.2%).

The psychosocial characteristics and their association with PPD (Table 3 )

Regarding the psychological and social characteristics of the mothers, the majority of mothers were unaware of the symptoms of PPD (75%), and only 236 (35.3%) experienced cultural stigma or judgment about PPD in the community. About 41 (6.1%) were diagnosed with PPD during the previous pregnancy, and only 42 (6.2%) were diagnosed and on medications.

A p -value of less than 0.001 demonstrates a highly statistically significant association with the presence of PPD. Mothers with PPD were significantly more likely to have a history of or be currently diagnosed with PPD, as well as financial and marital problems. Experienced cultural stigma or judgment about PPD and received more support.

Coping strategies and causes for not receiving the treatment and reaction to PPD (Table 3 ; Fig. 2 )

Causes for not receiving the treatment and reaction to PPD

Around half of the mothers didn’t feel comfortable discussing mental health: 292 (43.3%) with a physician, 307 (45.5%) with a husband, 326 (48.4%) with family, and 472 (70.0%) with the community. Moreover, mothers with PPD felt significantly more comfortable discussing mental health in descending order: 46 (50.0%) with a physician, 41 (44.6%) with a husband, and 39 (42.3%) with a family (Table 3 ).

There were different causes for not receiving the treatment and reactions to PPD, in descending order: 65.7% social norms, 60.5% cultural or traditional beliefs, 56.5% personal barriers, 48.5% geographical or regional disparities in mental health resources, 47.4% language or communication barriers, and 39.7% financial constraints.

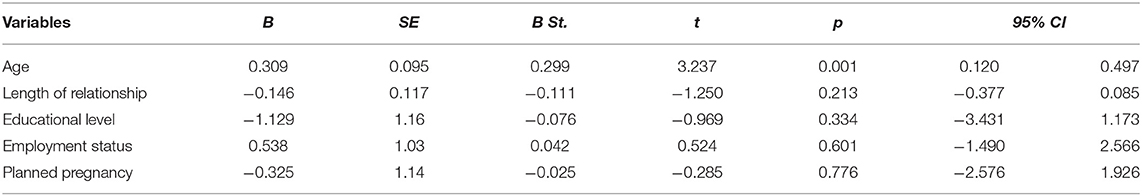

Prediction of PPD (significant demographics, obstetric, current pregnancy, and infant-related, and psychosocial), and coping strategies derived from multiple logistic regression analysis (Table 4 ).

Significant demographic predictors of ppd.

Marital Status (Married or Single): The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) among PPD mothers who were married in comparison to their single counterparts was 0.141 (95% CI: 0.04–0.494; p -value = 0.002).

Nationality: For PPD Mothers of Yemeni nationality compared to those with Egyptian nationality, the aOR was 0.318 (95% CI: 0.123–0.821, p = 0.018). Similarly, for Syrian nationality in comparison to Egyptian nationality, the aOR was 0.111 (95% CI: 0.0139–0.887, p = 0.038), and for Iraqi nationality compared to Egyptian nationality, the aOR was 0.241 (95% CI: 0.0920–0.633, p = 0.004).

Significant obstetric, current pregnancy, and infant-related characteristics predictors of PPD

Current Pregnancy Status (Precious Baby—Planned): The aOR for the occurrence of PPD among women with a “precious baby” relative to those with a “planned” pregnancy was 7.717 (95% CI: 1.822–32.689, p = 0.006).

Healthy Baby (No-Yes): The aOR for the occurrence of PPD among women with unhealthy babies in comparison to those with healthy ones is 11.685 (95% CI: 1.405–97.139, p = 0.023).

Postnatal Problems (No–Yes): The aOR among PPD mothers reporting postnatal problems relative to those not reporting such problems was 0.234 (95% CI: 0.0785–0.696, p = 0.009).

Significant psychological and social predictors of PPD

Receiving support or treatment for PPD (No-Yes): The aOR among PPD mothers who were not receiving support or treatment relative to those receiving support or treatment was 9.784 (95% CI: 5.373–17.816, p = 0.001).

Awareness of symptoms and risk factors (No-Yes): The aOR among PPD mothers who lack awareness of symptoms and risk factors relative to those with awareness was 2.902 (95% CI: 1.633–5.154, p = 0.001).

Experienced cultural stigma or judgement about PPD in the community (No-Yes): The aOR among PPD mothers who had experienced cultural stigma or judgment in the community relative to those who have not was 4.406 (95% CI: 2.394–8.110, p < 0.001).

Suffering from any disease or mental or psychiatric disorder: For “Now I am suffering—not at all,” the aOR among PPD mothers was 12.871 (95% CI: 3.063–54.073, p = 0.001). Similarly, for “Had a past history but was treated—not at all,” the adjusted odds ratio was 16.6 (95% CI: 2.528–108.965, p = 0.003), and for “Had a family history—not at all,” the adjusted odds ratio was 3.551 (95% CI: 1.012–12.453, p = 0.048).

Significant coping predictors of PPD comfort: discussing mental health with family (maybe yes)

The aOR among PPD mothers who were maybe more comfortable discussing mental health with family relatives was 0.369 (95% CI: 0.146–0.933, p = 0.035).

PDD is a debilitating mental disorder that has many potential and protective risk factors that should be considered to promote the mental and psychological well-being of the mothers and to create a favorable environment for the newborn and all family members. This multinational cross-sectional survey was conducted in six different countries to determine the frequency of PDD using EPDS and to explore its predictors. It was found that PPD was a prevalent problem that varied across different nations.

The frequency of PPD across the studied countries

Using the widely used EPDS to determine the current PPD, we found that the overall frequency of PPD in the total sample was 92 (13.6%). Which significantly ( p = 0.001) varied across different countries, being highest among Ghana mothers 13 (26.0%) out of 50 and Indians 28 (21.7%) out of 129. Egyptian 21 (19.1) out of 110, Yemen 14 (8.5%) out of 164, Iraq 13 (7.7%) out of 169, and Syria 1 (2.3%) out of 43 in descending order. This prevalence was similar to that reported by Hairol et al. (2021) in Malaysia (14.3%) [ 13 ], Yusuff et al. (2010) in Malaysia (14.3%) [ 14 ], and Nakku et al. (2006) in New Delhi (12.75%) [ 15 ].

While the frequency of PPD varied greatly based on the timing, setting, and existence of many psychosocial and post-partum periods, for example, it was higher than that reported in Italy (2012), which was 4.7% [ 16 ], in Turkey (2017) was 9.1%/110 [ 17 ], 9.2% in Sudan [ 18 ], Eritrea (2020) was 7.4% [ 19 ], in the capital Kuala Lumpur (2001) was (3.9%) [ 20 ], in Malaysia (2002) was (9.8%) [ 21 ], and in European countries. (2021) was 13–19% [ 22 ].

Lower frequencies were than those reported; PPD is a predominant problem in Asia, e.g., in Pakistan, the three-month period after childbirth, ranging from 28.8% in 2003 to 36% in 2006 to 94% in 2007, while after 12 months after childbirth, it was 62% in 2021 [ 23 – 24 ]. While in 2022 Afghanistan 45% after their first labour [ 25 ] in Canada (2015) was 40% [ 26 ], in India, the systematic review in 2022 was 22% of Primipara [ 27 ], in Malaysia (2006) was 22.8% [ 28 ], in India (2019) was 21.5% [ 29 ], in the Tigray zone in Ethiopia (2017) was 19% [ 30 ], varied in Iran between 20.3% and 35% [ 31 – 32 ], and in China was 499 (27.37%) out of 1823 [ 33 ]. A possible explanation might be the differences in the study setting and the type of design utilized. Other differences should be considered, like different populations with different socioeconomic characteristics and the variation in the timing of post-partum follow-up. It is vital to consider the role of culture, the impact of patients’ beliefs, and the cultural support for receiving help for PPD.

Demographic and health-related associations, or predictors of PPD (Tables 1 and 4 )

Regarding age, our study found no significant difference between PPD and non-PPD mothers with regard to age. In agreement with our study [ 12 , 34 , 35 ], other studies [ 36 , 37 , 38 ] found an inverse association between women’s age and PPD, with an increased risk of PPD (increases EPDS scores) at a younger age significantly, as teenage mothers, being primiparous, encounter difficulty during the postpartum period due to their inability to cope with financial and emotional difficulties, as well as the challenge of motherhood. Cultural factors and social perspectives of young mothers in different countries could be a reason for this difference. [ 38 – 39 ] and Abdollahi et al. [ 36 ] reported that older mothers were a protective factor for PPD (OR = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.84–0.92].

Regarding marital status, after controlling for other variables, married mothers exhibited a significantly diminished likelihood of experiencing PPD in comparison to single women (0.141; 95% CI: 0.04–0.494; p = 0.002). Also, Gebregziabher et al. [ 19 ] reported that there were statistically significant differences in proportions between mothers’ PPD and marital status.

Regarding the mother’s education, in agreement with our study, Ahmed et al. [ 34 ] showed that there was no statistically significant difference between PPD and a mother’s education. While Agarwala et al. [ 29 ] showed that a higher level of mother’s education. increases the risk of PPD, Gebregziabher et al. [ 19 ] showed that the housewives were 0.24 times less likely to develop PPD as compared to the employed mothers (aOR = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.06–0.97; p = 0.046); those mothers who perceived their socioeconomic status (SES) as low were 13 times more likely to develop PPD as compared to the mothers who had good SES (aOR = 13.33, 95% CI: 2.66–66.78; p = 0.002).

Regarding the SES or monthly income, while other studies [ 18 , 40 ] found that there was a statistically significant association between PPD mothers and different domains of SES, 34% of depressed women were found to live under low SES conditions in comparison to only 15.4% who were found to live in high SES and experienced PPD. In disagreement with our study, Hairol et al. [ 12 ] demonstrated that the incidence of PPD was significantly p = 0.01 higher for participants from the low-income group (27.27%) who were 2.58 times more likely to have PDD symptoms (OR: 2.58, 95% CI: 1.23–5.19; p = 0.01 compared to those from the middle- and high-income groups (8.33%), and low household income (OR = 3.57 [95% CI: 1.49–8.5] increased the odds of PPD [ 41 ].

Adeyemo et al. (2020),and Al Nasr et al. (2020) revealed that there was no significant difference between the occurrence of PPD and socio-demographic characteristics. This difference may be due to a different sample size and ethnicity [ 42 , 43 ]. In agreement with our findings, Abdollahi et al. [ 36 ] demonstrated that after multiple logistic regression analyses, there were increased odds of PPD with a lower state of general health (OR = 1.08 [95% CI: 1.06–1.11]), gestational diabetes (OR = 2.93 [95% CI = 1.46–5.88]), and low household income (OR = 3.57 [95% CI: 1.49–8.5]). The odds of PPD decreased.

Regarding access to health care, in agreement with studies conducted at Gondar University Hospital, Ethiopia [ 18 ], North Carolina, Colorado [ 21 ], Khartoum, Sudan [ 44 ], Asaye et al. [ 45 ], the current study found that participants who did not have free access to the healthcare system were riskier for the development of PPD. the study results may be affected by the care given during the antenatal care (ANC) visits. This can be explained by the fact that PPD was four times higher than that of mothers who did not have ANC, where counseling and anticipatory guidance care are given that build maternal self-esteem and resiliency, along with knowledge about normal and problematic complications to discuss at care visits and their right to mental and physical wellness, including access to care. The increased access to care (including postpartum visits) will increase the diagnosis of PPD and provide guidance, reassurance, and appropriate referrals. Healthcare professionals have the ability to both educate and empower mothers as they care for their babies, their families, and themselves [ 46 ].

Regarding nationality, for PPD mothers of Yemeni nationality compared to those of Egyptian nationality, the aOR is 0.318 (95% CI: 0.123–0.821, p = 0.018). Similarly, for Syrian nationality in comparison to Egyptian nationality, the aOR is 0.111 (95% CI: 0.0139–0.887, p = 0.038), and for Iraqi nationality compared to Egyptian nationality, the aOR is 0.241 (95% CI: 0.0920–0.633, p = 0.004). These findings indicated that, while accounting for other covariates, individuals from the aforementioned nationalities were less predisposed to experiencing PPD than their Egyptian counterparts. These findings can be explained by the fact that, in Egypt, the younger age of marriage, especially in rural areas, poor mental health services, being illiterate, dropping out of school early, unemployment, and the stigma of psychiatric illnesses are cultural factors that hinder the diagnosis and treatment of PPD [ 40 ].

Obstetric, current pregnancy, and infant-related characteristics and their association or predictors of PPD (Tables 2 and 4 )

In the present study, the number of dead children was significantly associated with PPD. This report was supported by studies conducted with Gujarati postpartum women [ 41 ] and rural southern Ethiopia [ 43 ]. This might be because mothers who have dead children pose different psychosocial problems and might regret it for fear of complications developing during their pregnancy. Agarwala et al. [ 29 ] found that a history of previous abortions and having more than two children increased the risk of developing PPD due to a greater psychological burden. The inconsistencies in the findings of these studies indicate that the occurrence of postpartum depression is not solely determined by the number of childbirths.

In obstetric and current pregnancy , there was no significant difference regarding the baby’s age, number of miscarriages, type of last delivery, premature labour, healthy baby, baby admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), or feeding difficulties. In agreement with Al Nasr et al. [ 42 ], inconsistent with Asaye et al. [ 45 ], they showed that concerning multivariable logistic regression analysis, abortion history, birth weight, and gestational age were significant associated factors of postpartum depression at a value of p < 0.05.

However, a close association was noted between the mode of delivery and the presence of PPD in mothers, with p = 0.107. There is a high tendency towards depression seen in mothers who have delivered more than three times (44%). In disagreement with what was reported by Adeyemo et al. [ 41 ], having more than five children ( p = 0.027), cesarean section delivery ( p = 0.002), and mothers’ poor state of health since delivery ( p < 0.001) are associated with an increase in the risk of PPD [ 47 ]. An increased risk of cesarean section as a mode of delivery was observed (OR = 1.958, p = 0.049) in a study by Al Nasr et al. [ 42 ].

We reported breastfeeding mothers had a lower, non-significant frequency of PPD compared to non-breast-feeding mothers (36.6% vs. 45%). In agreement with Ahmed et al. [ 34 ], they showed that with respect to breastfeeding and possible PPD, about 67.3% of women who depend on breastfeeding reported no PPD, while 32.7% only had PP. Inconsistency with Adeyemo et al. [ 41 ], who reported that unexclusive breastfeeding ( p = 0.003) was associated with PPD, while Shao et al. [ 40 ] reported that mothers who were exclusively formula feeding had a higher prevalence of PPD.

Regarding postnatal problems, our results revealed that postnatal problems display a significant association with PPD. In line with our results, Agarwala et al. [ 29 ] and Gebregziabher et al. [ 19 ] showed that mothers who experienced complications during childbirth, those who became ill after delivery, and those whose babies were unhealthy had a statistically significant higher proportion of PPD.

Hormone-related contraception methods were found to have a statistically significant association with PPD, consistent with the literature [ 46 ]; this can be explained by the hormones and neurotransmitters as biological factors that play significant roles in the onset of PPD. Estrogen hormones act as regulators of transcription from brain neurotransmitters and modulate the action of serotonin receptors. This hormone stimulates neurogenesis, the process of generating new neurons in the brain, and promotes the synthesis of neurotransmitters. In the hypothalamus, estrogen modulates neurotransmitters and governs sleep and temperature regulation. Variations in the levels of this hormone or its absence are linked to depression [ 19 ].

Participants whose last pregnancy was unplanned were 3.39 times more likely to have postpartum depression (aOR = 3.39, 95% CI: 1.24–9.28; p = 0.017). Mothers who experienced illness after delivery were more likely to develop PPD as compared to their counterparts (aOR = 7.42, 95% CI: 1.44–34.2; p = 0.016) [ 40 ]. In agreement with Asaye et al. [ 45 ] and Abdollahi et al. [ 36 ], unplanned pregnancy has been associated with the development of PPD (aOR = 2.02, 95% CI: 1.24, 3.31) and OR = 2.5 [95% CI: 1.69–3.7] than those of those who had planned, respectively.

The psychosocial characteristics and their association with PPD

Mothers with a family history of mental illness were significantly associated with PPD. This finding was in accordance with studies conducted in Istanbul, Turkey [ 47 ], and Bahrain [ 48 ]. Other studies also showed that women with PPD were most likely to have psychological symptoms during pregnancy [ 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ]. A meta-analysis of 24,000 mothers concluded that having depression and anxiety during pregnancy and a previous history of psychiatric illness or a history of depression are strong risk factors for developing PPD [ 50 , 51 , 52 ]. Asaye et al. [ 45 ], mothers whose relatives had mental illness history were (aOR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.09, 3.05 0) be depressed than those whose relatives did not have mental illness history.

This can be attributed to the links between genetic predisposition and mood disorders, considering both nature and nurture are important to address PDD. PPD may be seen as a “normal” condition for those who are acquainted with relatives with mood disorders, especially during the CBP. A family history of mental illness can be easily elicited in the ANC first visit history and requires special attention during the postnatal period. There are various risk factors for PPD, including stressful life events, low social support, the infant’s gender preference, and low income [ 53 ].

Concerning familial support and possible PPD, a statistically significant association was found between them. We reported that mothers who did not have social support (a partner or the father of the baby) had higher odds (aOR = 5.8, 95% CI: 1.33–25.29; p = 0.019) of experiencing PPD. Furthermore, Al Nasr et al. [ 42 ] revealed a significant association between the PPD and an unsupportive spouse ( P value = 0.023). while it was noted that 66.5% of women who received good familial support after giving birth had no depression, compared to 33.5% who only suffered from possible PPD [ 40 ]]. Also, Adeyemo et al. [ 41 ] showed that some psychosocial factors were significantly associated with having PPD: having an unsupportive partner ( p < 0.001), experiencing intimate partner violence ( p < 0.001), and not getting help in taking care of their baby ( p < 0.001). Al Nasr et al. (2020) revealed that the predictor of PPD was an unsupportive spouse (OR = 4.53, P = 0.049) [ 48 ].

Regarding the perceived stigma, in agreement with our study, Bina (2020) found that shame, stigma, the fear of being labeled mentally ill, and language and communication barriers were significant factors in women’s decisions to seek treatment or accept help [ 53 ]. Other mothers were hesitant about mental health services [ 54 ]. It is noteworthy that some PPD mothers refused to seek treatment due to perceived insufficient time and the inconvenience of attending appointments [ 55 ].

PPD was significantly higher among mothers with financial problems or problems with their husbands. This came in agreement with Ahmed et al. [ 34 ], who showed that, regarding stressful conditions and PPD, there was a statistically significant association with a higher percentage of PPD among mothers who had a history of stressful conditions (59.3%), compared to those with no history of stressful conditions (40.7%). Furthermore, Al Nasr et al. (2020) revealed that stressful life events contributed significantly ( P value = 0.003) to the development of PPD in the sample population. Al Nasr et al. stressful life events (OR = 2.677, p = 0.005) [ 42 ].

Coping strategies: causes of fearing and not seeking

Feeling at ease discussing mental health topics with one’s husband, family, community, and physician and experiencing cultural stigma or judgment regarding PPD within the community was significantly associated with the presence of PPD. In the current study, there were different reasons for not receiving the treatment, including cultural or traditional beliefs, language or communication barriers, social norms, and geographical or regional disparities in mental health resources. Haque and Malebranche [ 56 ] portrayed culture and the various conceptualizations of the maternal role as barriers to women seeking help and treatment.

In the present study, marital status, nationality, current pregnancy status, healthy baby, postnatal problems, receiving support or treatment for PPD, having awareness of symptoms and risk factors of PPD, suffering from any disease or mental or psychiatric disorder, comfort discussing mental health with family, and experiencing cultural stigma or judgment about PPD in the community were the significant predictors of PPD. In agreement with Ahmed et al. [ 34 ], the final logistic regression model contained seven predictors for PPD symptoms: SES, history of depression, history of PPD, history of stressful conditions, familial support, unwanted pregnancy, and male preference.

PPD has been recognized as a public health problem and may cause negative consequences for infants. It is estimated that 20 to 40% of women living in low-income countries experience depression during pregnancy or the postpartum period. The prevalence of PPD shows a wide variation, affecting 8–50% of postnatal mothers across countries [ 19 ].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include its multinational scope, which involved participants from six different countries, enhancing the generalizability of the findings. The study also boasted a large sample size of 674 participants, increasing the statistical power and reliability of the results. Standardized measures, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), were used for assessing postpartum depression, ensuring consistency and comparability across diverse settings. Additionally, the study explored a comprehensive range of predictors and associated factors of postpartum depression, including demographic, obstetric, health-related, and psychosocial characteristics. Rigorous analysis techniques, including multiple logistic regression analyses, were employed to identify significant predictors of postpartum depression, controlling for potential confounders and providing robust statistical evidence.

However, the study has several limitations that should be considered. Firstly, its cross-sectional design limits causal inference, as it does not allow for the determination of temporal relationships between variables. Secondly, the reliance on self-reported data, including information on postpartum depression symptoms and associated factors, may be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias. Thirdly, the use of convenience sampling methods may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader population. Lastly, cultural differences in the perception and reporting of postpartum depression symptoms among participants from different countries could influence the results.

Moreover, the variation in sample size and response rates among countries can be attributed to two main variables. (1) The methodology showed that the sample size was determined by considering several parameters, such as allocating proportionately to the mothers who gave birth and fulfilling the selection criteria during the data collection period served by each health center. (2) The political turmoil in Syria affects how often and how well people can use the Internet, especially because the data was gathered using an online survey link, leading to a relatively low number of responses from those areas. (3) Language barrier in Ghana: as we used the Arabic and English-validated versions of the EPDS, Ghana is a multilingual country with approximately eighty languages spoken. Although English is considered an official language, the primarily spoken languages in the southern region are Akan, specifically the Akuapem Twi, Asante Twi, and Fante dialects. In the northern region, primarily spoken are the Mole-Dagbani ethnic languages, Dagaare and Dagbanli. Moreover, there are around seventy ethnic groups, each with its own unique language [ 57 ]. (4) At the end of the data collection period, to avoid seasonal affective disorders, the meteorological autumn season began on the 1st day of September, which may be associated with autumm depressive symptoms that may confound or affect our results. Furthermore, the sampling methods were not universal across all Arabic countries, potentially constraining the generalizability of our findings.

Recommendations

The antenatal programme should incorporate health education programmes about the symptoms of PPD. Health education programs about the symptoms of PPD should be included in the antenatal program.

Mass media awareness campaigns have a vital role in raising public awareness about PPD-related issues. Mass media.

The ANC first visit history should elicit a family history of mental illness, enabling early detection of risky mothers. Family history of mental illness can be easily elicited in the ANC first visit history.

For effective management of PPD, effective support (from husband, friends, and family) is an essential component. For effective management of PPD effectiveness of support.

The maternal (antenatal, natal, and postnatal) services should be provided for free and of high quality The maternal (antenatal, natal, postnatal) services should be provided free and of high quality.

It should be stressed that although numerous studies have been carried out on PPD, further investigation needs to be conducted on the global prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in pregnant women and related risk factors, especially in other populations.

Around 14% of the studied mothers had PPD, and the frequency varies across different countries and half of them do not know. Our study identified significant associations and predictors of postpartum depression (PPD) among mothers. Marital status was significantly associated with PPD, with married mothers having lower odds of experiencing PPD compared to single mothers. Nationality also emerged as a significant predictor, with Yemeni, Syrian, and Iraqi mothers showing lower odds of PPD compared to Egyptian mothers. Significant obstetric, current pregnancy, and infant-related predictors included the pregnancy status, the health status of the baby, and the presence of postnatal problems. Among psychological and social predictors, receiving support or treatment for PPD, awareness of symptoms and risk factors, experiencing cultural stigma or judgment about PPD, and suffering from any disease or mental disorder were significantly associated with PPD. Additionally, mothers who were maybe more comfortable discussing mental health with family relatives had lower odds of experiencing PPD.

These findings underscore the importance of considering various demographic, obstetric, psychosocial, and coping factors in the identification and management of PPD among mothers. Targeted interventions addressing these predictors could potentially mitigate the risk of PPD and improve maternal mental health outcomes.

Data availability

Yes, I have research data to declare.The data is available when requested from the corresponding author [email protected].

Abbreviations

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- Postpartum depression

Primary Health Care centers

Socioeconomic Status

program (Statistical Package for Social Science

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Sultan P, Ando K, Elkhateb R, George RB, Lim G, Carvalho B et al. (2022). Assessment of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for Maternal Postpartum Depression Using the Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments Guideline: A Systematic Review. JAMA Network Open; 1;5(6).

Crotty F, Sheehan J. Prevalence and detection of postnatal depression in an Irish community sample. Ir J Psychol Med. 2004;21:117–21.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Goodman SH, Brand SR. Parental psychopathology and its relation to child psychopathology. In: Hersen M, Gross AM, editors. Handbook of clinical psychology vol 2: children and adolescents. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2008. pp. 937–65.

Google Scholar

Wang Z, Liu J, Shuai H, Cai Z, Fu X, Liu Y, Xiao et al. (2021). Mapping global prevalence of depression among postpartum women. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01663-6 . Erratum in: Transl Psychiatry; 20;11(1):640. PMID: 34671011IF: 6.8 Q1 B1; PMCID: PMC8528847IF: 6.8 Q1 B1.Lase accessed Jan 2024.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; Lase accessed October 2023.

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:289–95.

Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, Brody S, Miller WC. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes: Summary. AHRQ evidence report summaries; 2005. pp. 71–9.

O’hara MW, Swain AM. (1996). Rates and risk of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996; 8:37–54.

Goodman SH, Brand SR. (2008). Parental psychopathology and its relation to child psychopathology. In: Hersen M, Gross AM, editors. Handbook of clinical psychology Vol 2: Children and adolescents. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. pp. 937–65.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Martín-Gómez C, Moreno-Peral P, Bellón J, SC Cerón S, Campos-Paino H, Gómez-Gómez I, Rigabert A, Benítez I, Motrico E. Effectiveness of psychological, psychoeducational and psychosocial interventions to prevent postpartum depression in adolescent and adult mothers: study protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ open. 2020;10(5):e034424. [accessed Mar 16 2024].

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sehairi Z. (2020). Validation Of The Arabic Version Of The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale And Prevalence Of Postnatal Depression On An Algerian Sample. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:216391386 . Accessed August 2023.

Hairol MI, Ahmad SA, Sharanjeet-Kaur S et al. (2021). Incidence and predictors of postpartum depression among postpartum mothers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 16(11), e0259782.

Yusuff AS, Tang L, Binns CW, Lee AH. Prevalence and risk factors for postnatal depression in Sabah, Malaysia: a cohort study. Women Birth. 2015;1(1):25–9. pmid:25466643

Article Google Scholar

Nakku JE, Nakasi G, Mirembe F. Postpartum major depression at six weeks in primary health care: prevalence and associated factors. Afr Health Sci. 2006;6(4):207–14. https://doi.org/10.5555/afhs.2006.6.4.207 . PMID: 17604509IF: 1.0 Q4 B4; PMCID: PMC1832062

Clavenna A, Seletti E, Cartabia M, Didoni A, Fortinguerra F, Sciascia T, et al. Postnatal depression screening in a paediatric primary care setting in Italy. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):42. pmid:28122520

Serhan N, Ege E, Ayrancı U, Kosgeroglu N. (2013). Prevalence of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers and its correlates. Journal of clinical nursing; 1;22(1–2):279–84. pmid:23216556

Deribachew H, Berhe D, Zaid T, et al. Assessment of prevalence and associated factors of postpartum depression among postpartum mothers in eastern zone of Tigray. Eur J Pharm Med Res. 2016;3(10):54–60.

Gebregziabher NK, Netsereab TB, Fessaha YG, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of postpartum depression among postpartum mothers in central region, Eritrea: a health facility based survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–10.

Grace J, Lee K, Ballard C, et al. The relationship between post-natal depression, somatization and behaviour in Malaysian women. Transcult Psychiatry. 2001;38(1):27–34.

Mahmud WMRW, Shariff S, Yaacob MJ. Postpartum depression: a survey of the incidence and associated risk factors among malay women in Beris Kubor Besar, Bachok, Kelantan. The Malaysian journal of medical sciences. Volume 9. MJMS; 2002. p. 41. 1.

Anna S. Postpartum depression and birthexperience in Russia. Psychol Russia: State Theart. 2021;14(1):28–38.

Yadav T, Shams R, Khan AF, Azam H, Anwar M et al. (2020).,. Postpartum Depression: Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors Among Women in Sindh, Pakistan. Cureus.22;12(12):e12216. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.12216 . PMID: 33489623IF: 1.2 NA NA; PMCID: PMC7815271IF: 1.2 NA NA.

Abdullah M, Ijaz S, Asad S. (2024). Postpartum depression-an exploratory mixed method study for developing an indigenous tool. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24, 49 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-06192-2 .

Upadhyay RP, Chowdhury R, Salehi A, Sarkar K, Singh SK, Sinha B et al. (2022). Postpartum depression in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 2017 October 10 [cited 2022 October 6];95(10):706. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.192237/ .

Khalifa DS, Glavin K, Bjertness E et al. (2016). Determinants of postnatal depression in Sudanese women at 3 months postpartum: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 6(3), e00944327).

Khadija Sharifzade BK, Padhi S, Manna etal. (2022). Prevalence and associated factors of postpartum depression among Afghan women: a phase-wise cross-sectional study in Rezaie maternal hospital in Herat province.; Razi International Medical Journa2| 2|59| https://doi.org/10.56101/rimj.v2i2.59 .

Azidah A, Shaiful B, Rusli N, et al. Postnatal depression and socio-cultural practices among postnatal mothers in Kota Bahru, Kelantan, Malaysia. Med J Malay. 2006;61(1):76–83.

CAS Google Scholar

Agarwala A, Rao PA, Narayanan P. Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression among mothers in the rural areas of Udupi Taluk, Karnataka, India: a cross-sectional study. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2019;7(3):342–5.

Arikan I, Korkut Y, Demir BK et al. (2017). The prevalence of postpartum depression and associated factors: a hospital-based descriptive study.

Azimi-Lolaty HMD, Hosaini SH, Khalilian A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression among pregnant women referred to mother-child health care clinics (MCH). Res J Biol Sci. 2007;2:285–90.

Najafi KFA, Nazifi F, Sabrkonandeh S. Prevalence of postpartum depression in Alzahra Hospital in Rasht in 2004. Guilan Univ Med Sci J. 2006;15:97–105. (In Persian.).

Deng AW, Xiong RB, Jiang TT, Luo YP, Chen WZ. (2014). Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in a population-based sample of women in Tangxia Community, Guangzhou. Asian Pacific journal of tropical medicine; 1;7(3):244–9. pmid:24507649

Ahmed GK, Elbeh K, Shams RM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression in Upper Egypt: a multicenter primary health care study. J Affect Disord. 2021;290:211–8.

Cantilino A, Zambaldi CF, Albuquerque T, et al. Postpartum depression in Recife–Brazil: prevalence and association with bio-socio-demographic factors. J Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;59:1–9.

Abdollahi F, Zarghami M, Azhar MZ, et al. Predictors and incidence of post-partum depression: a longitudinal cohort study. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2014;40(12):2191–200.

McCoy SJB, Beal JM, et al. Risk factors for postpartum depression: a retrospective investigation at 4-weeks postnatal and a review of the literature. JAOA. 2006;106:193–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Sierra J. (2008). Risk Factors Related to Postpartum Depression in Low-Income Latina Mothers. Ann Arbor: ProQuest Information and Learning Company, 2008.

Çankaya S. The effect of psychosocial risk factors on postpartum depression in antenatal period: a prospective study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2020;34(3):176–83.

Shao HH, Lee SC, Huang JP, et al. Prevalence of postpartum depression and associated predictors among Taiwanese women in a mother-child friendly hospital. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2021;33(4):411–7.

Adeyemo EO, Oluwole EO, Kanma-Okafor OJ, et al. Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression among postnatal women in Lagos. Nigeria Afr Health Sci. 2020;20(4):1943–54.

Al Nasr RS, Altharwi K, Derbah MS et al. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. PLoS ONE, 15(2), e0228666.

Desai ND, Mehta RY, Ganjiwale J. Study of prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression. Natl J Med Res. 2012;2(02):194–8.

Azale T, Fekadu A, Medhin G, et al. Coping strategies of women with postpartum depression symptoms in rural Ethiopia: a cross-sectional community study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–13.

Asaye MM, Muche HA, Zelalem ED. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression: Northwest Ethiopia. Psychiatry journal, 2020.

Ayele TA, Azale T, Alemu K et al. (2016). Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression among women attending antenatal care service at Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE, 11(5), e0155125.

Saraswat N, Wal P, Pal RS et al. (2021). A detailed Biological Approach on Hormonal Imbalance Causing Depression in critical periods (Postpartum, Postmenopausal and Perimenopausal Depression) in adult women. Open Biology J, 9.

Guida J, Sundaram S, Leiferman J. Antenatal physical activity: investigating the effects on postpartum depression. Health. 2012;4:1276–86.

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:289–95.

Watanabe M, Wada K, Sakata Y, et al. Maternity blues as predictor of postpartum depression: a prospective cohort study among Japanese women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2008;29:211–7.

Kirpinar I˙, Gözüm S, Pasinliog˘ lu T. Prospective study of post-partum depression in eastern Turkey prevalence, socio- demographic and obstetric correlates, prenatal anxiety and early awareness. J Clin Nurs. 2009;19:422–31.

Zhao XH, Zhang ZH. Risk factors for postpartum depression: an evidence-based systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;53:102353.

Bina R. Predictors of postpartum depression service use: a theory-informed, integrative systematic review. Women Birth. 2020;33(1):e24–32.