- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Today's FT newspaper for easy reading on any device. This does not include ft.com or FT App access.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Premium Digital

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

How the American dream turned into greed and inequality

'Promoting individual happiness as our utmost ethos is self-defeating, as deeply divided societies turn unstable and unhappy'

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Alberto Gallo

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Economic Progress is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, economic progress.

The American Dream is broken. Paul Ryan, speaker of the House of Representatives, recently stated that "in our country, the condition of your birth does not determine the outcome of your life."

Yet the idea that every American has an equal opportunity to move up in life is false. Social mobility has declined over the past decades, median wages have stagnated and today's young generation is the first in modern history expected to be poorer than their parents . The lottery of life - the postcode where you were born - can account for up to two thirds of the wealth an individual generates.

The growing gap between the rich and the poor, the old and the young, has been largely ignored by policymakers and investors until the recent rise of anti-establishment votes, including those for Brexit in the UK and for President Trump in the US. This is a mistake.

Inequality is much more than a side-effect of free market capitalism. It is a symptom of policy negligence, where for decades, credit and monetary stimulus shortcuts too easily substituted for structural reform, investment and economic strategy. Capitalism has been incredibly successful at boosting wealth, but it has failed at redistributing it. Today, without a push to redistribute wealth and opportunity, our model of capitalism and democracy may face self-destruction.

The widening of inequality has deep historical roots. Keynes' interventionist policies worked well during the post-war recovery, as fiscal stimulus for the reconstruction boosted demand for US goods from Europe and Japan. But soon the stimulus faded. The U.S. found itself with declining growth and rising inflation at a time when it was mired in the Cold War and Vietnam conflicts. The baby boomer generation demanded higher living standards. The response was the Nixon shock in 1971: a set of policies which moved away from the gold standard, initiating the era of fiat money and free credit.

Credit was the answer to declining growth and rising inequality: if you couldn't afford university, a new house or a new car, Uncle Sam would lend you the key to the American Dream in the form of that extra loan you needed. Over the following decades, state subsidies to private credit became popular, spreading to the U.K. and Europe.

It was the start of debt-based democracies. Private debt outgrew GDP four times in the US and Europe over the following decades up to the 2008 financial crisis, accompanied by the deregulation of financial markets and of banks. The rest is history: nine long years after the crisis, our economies are still healing from excess debt, and regulators are still working on strengthening our financial system. Inequality, however, has deepened even further. Has capitalism failed?

The deus ex- machina of capitalism was competition; a distorted interpretation of Adam Smith’s invisible hand. Competition among individuals and companies created efficient markets, increasing production and GDP. Government intervention became unnecessary: any wealth generated in the economic process would automatically trickle down from the haves to the have-nots. Greed, the unshackled pursuit of individual wealth, turned from vice to virtue.

Have you read?

The future of jobs report 2023, how to follow the growth summit 2023.

Today, we know the neoliberal policies initiated by Reagan and Thatcher have been successful at generating growth: the United States and the UK have outpaced others. But we also know that the same neoliberal policies have failed at redistributing resources and opportunity. If individual economic success is deemed the highest possible achievement, poverty becomes justified by someone’s lack of effort or ability. But with rising social and corporate inequality , productivity has stagnated, lowering potential growth rates for the whole economy. The result has been a self-reinforcing cycle of lower productivity, lower interest rates, higher debt levels and even higher inequality.

If trickle-down and neoliberalism have failed the good news is there are some policy fixes. One of them is taxation, combined with investment in productive infrastructure and education. The bad news is policy is going exactly in the opposite direction, especially in the US and the UK.

The Trump Administration’s tax breaks may boost markets, but will likely increase public debt even further, calling for more cuts to education and healthcare.

Defenders of neoliberal policies like Mr Ryan argue that equality of opportunity is fair, while equality of outcome – which Milton Friedman called socialism – is unfair and not meritocratic. The reality is that both wealth and income inequality are closely linked. Richer parents can afford to send their children to better schools: nearly half of the variation in wages of sons in the United States can be explained by looking at the wages of their fathers a generation before. That compares to less than 20% in relatively egalitarian and tuition-free countries like Finland, Norway and Denmark. The story is similar in the UK , where over half of judges, MPs and CEOs of UK companies attended expensive private schools, while around one third of children live below the poverty line – 67% of those from working families . Better education means better opportunities and more wealth later in life: the cycle reinforces itself from generation to generation.

But today this cycle may be at breaking point. If " let-them-eat-credit " policies allowed the 99% to borrow and increase their well-being over the past decades, interest rates have now reached rock-bottom and private debt levels are at their highest. There are signs that monetary policy may have reached its limits – creating asset bubbles and keeping zombie companies alive – and that it may no longer be able to support this ever-growing debt mountain.

The risk is that rising inequality, lower social mobility and the disenfranchisement of younger generations could result into even more polarised and short-sighted politics, creating a populist trap. The US and the UK could already be stuck: many of the policies on the table in both countries are far from sustainable, and damaging for the people they were to protect. Brexit or an exit from NAFTA are both striking examples.

Continental Europe and Scandinavia – even though far from perfect – have so far escaped from the worst of the populist threat of the Front National, Alternative for Germany, True Finns or the Danish People's Party, perhaps thanks to their stronger safety net and welfare policies. However, these parties continue to gain ground, as recent elections in Germany and Austria show.

There are two ways we think the world may exit this loop of rising inequality, political polarisation and short-sighted politics. One is to make the poor richer through education and investment. The other is to make the rich poorer.

Last year, the IMF ditched neoliberalism and recommended measures to redistribute wealth and opportunity. This policy mix could reduce inequality, boost political stability and improve long-term growth. In its five-year plan, China's leadership recently announced a renewed focus on reducing inequality. The US and UK, too, should acknowledge they have a structural, not a cyclical problem, that cannot be solved with one more round of monetary stimulus. Redistribution should be coupled with a reform of the financial system , still too centered on risk-taking and debt incentives; as well as changes to the tax system , which still places too much burden on income and too little on assets.

The alternative to redistribution is instability and crisis. Inequality provides fertile ground for populist parties to harvest support. The US, for instance, has recently been downgraded from full democracy to a flawed democracy . Over time, populist policies can destabilize democracies, turning them towards nationalism, militarism and anti-capitalism. The outcome of populist regimes in history ranges from higher taxes to nationalizations and violations of private property, to commercial and military conflicts.

Neoliberal theory and its policy offshoots have failed. Promoting individual happiness as our utmost ethos is self-defeating, as deeply divided societies turn unstable and unhappy. We need a new American dream based on equality and sustainable growth. The cost of sharing opportunity and wealth may be high for today's elites, but the alternative is far worse.

The end of neoliberalism?

Shift work is hurting our health and happiness. here's why, to save globalization, its benefits need to be more broadly shared, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Economic Progress .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

IMF says global economy 'remains remarkably resilient', and other economics news

April 19, 2024

The latest from the IMF on the global economy, and other economics stories to read

April 12, 2024

Eurozone inflation, Asian factory activity and other economics news to read

April 5, 2024

Top weekend reads on Agenda: Paris Olympics, Japan's negative interest rates, and more

Pooja Chhabria

March 28, 2024

What we learned about effective decision making from Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman

Kate Whiting

China's industrial profits grow, and other economics stories to read this week

Is the American dream really dead?

Subscribe to global connection, carol graham carol graham senior fellow - economic studies @cgbrookings.

June 20, 2017

This piece was originally published on The Guardian on June 20, 2017.

T he United States has a long-held reputation for exceptional tolerance of income inequality, explained by its high levels of social mobility. This combination underpins the American dream – initially conceived of by Thomas Jefferson as each citizen’s right to the pursuit of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

This dream is not about guaranteed outcomes, of course, but the pursuit of opportunities. The dream found a persona in the fictional characters of the 19th-century writer Horatio Alger Jr – in which young working-class protagonists go from from rags to riches (or at least become middle class) in part due to entrepreneurial spirit and hard work.

Yet the opportunity to live the American dream is much less widely shared today than it was several decades ago. While 90% of the children born in 1940 ended up in higher ranks of the income distribution than their parents, only 40% of those born in 1980 have done so .

Attitudes about inequality have also changed. In 2001, a study found the only Americans who reported lower levels of happiness amid greater inequality were left-leaning rich people – with the poor seeing inequality as a sign of future opportunity . Such optimism has since been substantially tempered: in 2016, only 38% of Americans thought their children would be better off than they are.

In the meantime, the public discussion about inequality has completely by-passed a critical element of the American dream: luck .

Just as in many of Alger’s stories the main character benefits from the assistance of a generous philanthropist, there are countless real examples of success in the US where different forms of luck have played a major role. And yet, social support for the unlucky – in particular, the poor who cannot stay in full-time employment – has been falling substantially in recent years, and is facing even more threats today.

In short, from new research based on some novel metrics of wellbeing, I find strong evidence that the American dream is in tatters, at least.

White despair, minority hope

My research began by comparing mobility attitudes in the US with those in Latin America, a region long known for high levels of poverty and inequality (although with progress in the past decades). I explored a question in the Gallup world poll, which asks respondents a classic American dream question: “Can an individual who works hard in this country get ahead?”

I found very large gaps between the responses of ‘the rich’ and ‘the poor’ in the US (represented by the top and bottom 20% income distributions of the Gallup respondents). This was in stark contrast to Latin America, where there was no significant difference in attitudes across income groups. Poor people in the US were 20 times less likely to believe hard work would get them ahead than were the poor in Latin America, even though the latter are significantly worse off in material terms.

Another question in the poll explores whether or not respondents experience stress on a daily basis. Stress is a marker of poor health, and the kind of stress typically experienced by the poor – usually due to negative shocks that are beyond their control (“bad stress”) – is significantly worse for well being than “good stress”: that which is associated with goal achievement, for those who feel able to focus on their future.

In general, Latin Americans experience significantly less stress – and also smile more – on a daily basis than Americans. The gaps between the poor and rich in the US were significantly wider (by 1.5 times on a 0–1 score) than those in Latin America, with the poor in the US experiencing more stress than either the rich or poor in Latin America.

The gaps between the expectations and sentiments of rich and poor in the US are also greater than in many other countries in east Asia and Europe (the other regions studied). It seems that being poor in a very wealthy and unequal country – which prides itself on being a meritocracy, and eschews social support for those who fall behind – results in especially high levels of stress and desperation.

But my research also yielded some surprises. With the low levels of belief in the value of hard work and high levels of stress among poor respondents in the US as a starting point, I compared optimism about the future across poor respondents of different races. This was based on a question in the US Gallup daily poll that asks respondents where they think they will be five years from now on a 0-10 step life satisfaction ladder.

I found that poor minorities – and particularly black people – were much more optimistic about the future than poor white people. Indeed, poor black respondents were three times as likely to be a point higher up on the optimism ladder than were poor whites, while poor Hispanic people were one and a half times more optimistic than whites. Poor black people were also half as likely as poor whites to experience stress the previous day, while poor Hispanics were only two-thirds as likely as poor whites.

What explains the higher levels of optimism among minorities, who have traditionally faced discrimination and associated challenges? There is no simple answer.

One factor is that poor minorities have stronger informal safety nets and social support, such as families and churches, than do their white counterparts. Psychologists also find that minorities are more resilient and much less likely to report depression or commit suicide than are whites in the face of negative shocks, perhaps due to a longer trajectory of dealing with negative shocks and challenges.

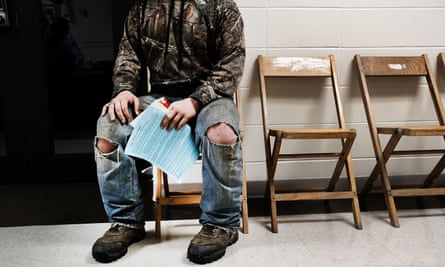

Another critical issue is the threat and reality of downward mobility for blue-collar whites, particularly in the heartland of the country where manufacturing, mining, and other jobs have hollowed out. Andrew Cherlin of Johns Hopkins University finds that poor black and Hispanic people are much more likely than poor white people to report that they live better than their parents did. Poor whites are more likely to say they live worse than their parents did; they, in particular, seem to be living the erosion of the American dream.

The American problem

Why does this matter? My research from a decade ago – since confirmed by other studies – found that individuals who were optimistic about their futures tended to have better health and employment outcomes. Those who believe in their futures tend to invest in those futures, while those who are consumed with stress, daily struggles and a lack of hope, not only have less means to make such investments, but also have much less confidence that they will pay off.

The starkest marker of lack of hope in the US is a significant increase in premature mortality in the past decade – driven by an increase in suicides and drug and alcohol poisoning and a stalling of progress against heart disease and lung cancer – primarily but not only among middle-aged uneducated white people. Mortality rates for black and Hispanic people, while higher on average than those for whites, continued to fall during the same time period.

The reasons for this trend are multi-faceted. One is the coincidence of an all-too-readily-available supply of drugs such as opioids, heroin and fentanyl, with the shrinking of blue-collar jobs – and identities – primarily due to technological change. Fifteen per cent of prime age males are out of the labour force today; with that figure projected to increase to 25% by 2050. The identity of the blue-collar worker seems to be stronger for white people than for minorities, meanwhile. While there are now increased employment opportunities in services such as health, white males are far less likely to take them up than are their minority counterparts.

Lack of hope also contributes to rising mortality rates, as evidenced in my latest research with Sergio Pinto . On average, individuals with lower optimism for the future are more likely to live in metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) with higher mortality rates for 45- to 54-year-olds.

Desperate people are more likely to die prematurely, but living with a lot of premature death can also erode hope. Higher average levels of optimism in metropolitan areas are also associated with lower premature mortality rates. These same places tend to be more racially diverse, healthier (as gauged by fewer respondents who smoke and more who exercise), and more likely to be urban and economically vibrant.

Technology-driven growth is not unique to the US, and low-skilled workers face challenges in many OECD countries. Yet by contrast, away from the US, they have not had a similar increase in premature mortality. One reason may be stronger social welfare systems – and stronger norms of collective social responsibility for those who fall behind – in Europe.

Ironically, part of the problem may actually be the American dream. Blue-collar white people – whose parents lived the American dream and who expected their children to do so as well – are the ones who seem most devastated by its erosion and yet, on average, tend to vote against government programmes. In contrast, minorities, who have been struggling for years and have more experience multi-tasking on the employment front and relying on family and community support when needed – are more resilient and hopeful, precisely because they still see a chance for moving up the ladder.

There are high costs to being poor in America, where winners win big but losers fall hard. Indeed, the dream, with its focus on individual initiative in a meritocracy, has resulted in far less public support than there is in other countries for safety nets, vocational training, and community support for those with disadvantage or bad luck. Such strategies are woefully necessary now, particularly in the heartland where some of Alger’s characters might have come from, but their kind have long since run out of luck.

Related Content

Carol Graham

December 1, 2017

May 27, 2016

Carol Graham, Sergio Pinto

June 8, 2017

Related Books

Luis Felipe López-Calva, Nora Claudia Lustig

May 28, 2010

Nora Claudia Lustig

September 1, 1995

Robert M. Ball

November 1, 2000

Economic Security & Mobility

Global Economy and Development

The Brookings Institution, Washington DC

1:00 pm - 2:30 pm EDT

Janet Gornick, David Brady, Ive Marx, Zachary Parolin

April 17, 2024

Lauren Bauer, Bradley Hardy, Olivia Howard

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Do You Think the American Dream Is Real?

By Jeremy Engle

- Feb. 12, 2019

What does the American dream mean to you? A house with a white picket fence? Lavish wealth? A life better than your parents’?

Do you think you will be able to achieve the American dream?

In “ The American Dream Is Alive and Well ,” Samuel J. Abrams writes:

I am pleased to report that the American dream is alive and well for an overwhelming majority of Americans. This claim might sound far-fetched given the cultural climate in the United States today. Especially since President Trump took office, hardly a day goes by without a fresh tale of economic anxiety, political disunity or social struggle. Opportunities to achieve material success and social mobility through hard, honest work — which many people, including me, have assumed to be the core idea of the American dream — appear to be diminishing. But Americans, it turns out, have something else in mind when they talk about the American dream. And they believe that they are living it. Last year the American Enterprise Institute and I joined forces with the research center NORC at the University of Chicago and surveyed a nationally representative sample of 2,411 Americans about their attitudes toward community and society. The center is renowned for offering “deep” samples of Americans, not just random ones, so that researchers can be confident that they are reaching Americans in all walks of life: rural, urban, exurban and so on. Our findings were released on Tuesday as an American Enterprise Institute report.

What our survey found about the American dream came as a surprise to me. When Americans were asked what makes the American dream a reality, they did not select as essential factors becoming wealthy, owning a home or having a successful career. Instead, 85 percent indicated that “to have freedom of choice in how to live” was essential to achieving the American dream. In addition, 83 percent indicated that “a good family life” was essential. The “traditional” factors (at least as I had understood them) were seen as less important. Only 16 percent said that to achieve the American dream, they believed it was essential to “become wealthy,” only 45 percent said it was essential “to have a better quality of life than your parents,” and just 49 percent said that “having a successful career” was key.

The Opinion piece continues:

The data also show that most Americans believe themselves to be achieving this version of the American dream, with 41 percent reporting that their families are already living the American dream and another 41 percent reporting that they are well on the way to doing so. Only 18 percent took the position that the American dream was out of reach for them

Collectively, 82 percent of Americans said they were optimistic about their future, and there was a fairly uniform positive outlook across the nation. Factors such as region, urbanity, partisanship and housing type (such as a single‐family detached home versus an apartment) barely affected these patterns, with all groups hovering around 80 percent. Even race and ethnicity, which are regularly cited as key factors in thwarting upward mobility, corresponded to no real differences in outlook: Eighty-one percent of non‐Hispanic whites; 80 percent of blacks, Hispanics and those of mixed race; and 85 percent of those with Asian heritage said that they had achieved or were on their way to achieving the American dream.

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

— What does the American dream mean to you? Did reading this article change your definition? Do you think your own dreams are different from those of your parents at your age? Your grandparents?

— Do you believe your family has achieved, or is on the way to achieving, the American dream? Why or why not? Do you think you will be able to achieve the American dream when you are older? What leads you to believe this?

— Do you think the American dream is available to all Americans or are there boundaries and obstacles for some? If yes, what are they?

— The article concludes:

What conclusions should we draw from this research? I think the findings suggest that Americans would be well served to focus less intently on the nastiness of our partisan politics and the material temptations of our consumer culture, and to focus more on the communities they are part of and exercising their freedom to live as they wish. After all, that is what most of us seem to think is what really matters — and it’s in reach for almost all of us.

Do you agree? What other conclusions might be drawn? Does this article make you more optimistic about this country and your future?

— Is the American dream a useful concept? Is it helpful in measuring our own or our country’s health and success? Do you believe it is, or has ever been, an ideal worth striving for? Is there any drawback to continuing to use the concept even as its meaning evolves?

Students 13 and older are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Is the American dream really dead?

Research shows that poor people in the US are 20 times less likely to believe hard work will get them ahead than their (poorer) Latin American counterparts – with white Americans particularly pessimistic. What’s driving their despair?

T he United States has a long-held reputation for exceptional tolerance of income inequality, explained by its high levels of social mobility. This combination underpins the American dream – initially conceived of by Thomas Jefferson as each citizen’s right to the pursuit of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

This dream is not about guaranteed outcomes, of course, but the pursuit of opportunities. The dream found a persona in the fictional characters of the 19th-century writer Horatio Alger Jr – in which young working-class protagonists go from from rags to riches (or at least become middle class) in part due to entrepreneurial spirit and hard work.

Yet the opportunity to live the American dream is much less widely shared today than it was several decades ago. While 90% of the children born in 1940 ended up in higher ranks of the income distribution than their parents, only 40% of those born in 1980 have done so .

Attitudes about inequality have also changed. In 2001, a study found the only Americans who reported lower levels of happiness amid greater inequality were left-leaning rich people – with the poor seeing inequality as a sign of future opportunity . Such optimism has since been substantially tempered: in 2016, only 38% of Americans thought their children would be better off than they are.

In the meantime, the public discussion about inequality has completely by-passed a critical element of the American dream: luck .

Just as in many of Alger’s stories the main character benefits from the assistance of a generous philanthropist, there are countless real examples of success in the US where different forms of luck have played a major role. And yet, social support for the unlucky – in particular, the poor who cannot stay in full-time employment – has been falling substantially in recent years, and is facing even more threats today.

In short, from new research based on some novel metrics of wellbeing, I find strong evidence that the American dream is in tatters, at least.

White despair, minority hope

My research began by comparing mobility attitudes in the US with those in Latin America, a region long known for high levels of poverty and inequality (although with progress in the past decades). I explored a question in the Gallup world poll, which asks respondents a classic American dream question: “Can an individual who works hard in this country get ahead?”

I found very large gaps between the responses of ‘the rich’ and ‘the poor’ in the US (represented by the top and bottom 20% income distributions of the Gallup respondents). This was in stark contrast to Latin America, where there was no significant difference in attitudes across income groups. Poor people in the US were 20 times less likely to believe hard work would get them ahead than were the poor in Latin America, even though the latter are significantly worse off in material terms.

Another question in the poll explores whether or not respondents experience stress on a daily basis. Stress is a marker of poor health, and the kind of stress typically experienced by the poor – usually due to negative shocks that are beyond their control (“bad stress”) – is significantly worse for wellbeing than “good stress”: that which is associated with goal achievement, for those who feel able to focus on their future.

In general, Latin Americans experience significantly less stress – and also smile more – on a daily basis than Americans. The gaps between the poor and rich in the US were significantly wider (by 1.5 times on a 0–1 score) than those in Latin America, with the poor in the US experiencing more stress than either the rich or poor in Latin America.

The gaps between the expectations and sentiments of rich and poor in the US are also greater than in many other countries in east Asia and Europe (the other regions studied). It seems that being poor in a very wealthy and unequal country – which prides itself on being a meritocracy, and eschews social support for those who fall behind – results in especially high levels of stress and desperation.

But my research also yielded some surprises. With the low levels of belief in the value of hard work and high levels of stress among poor respondents in the US as a starting point, I compared optimism about the future across poor respondents of different races. This was based on a question in the US Gallup daily poll that asks respondents where they think they will be five years from now on a 0-10 step life satisfaction ladder.

I found that poor minorities – and particularly black people – were much more optimistic about the future than poor white people. Indeed, poor black respondents were three times as likely to be a point higher up on the optimism ladder than were poor whites, while poor Hispanic people were one and a half times more optimistic than whites. Poor black people were also half as likely as poor whites to experience stress the previous day, while poor Hispanics were only two-thirds as likely as poor whites.

What explains the higher levels of optimism among minorities, who have traditionally faced discrimination and associated challenges? There is no simple answer.

One factor is that poor minorities have stronger informal safety nets and social support, such as families and churches, than do their white counterparts. Psychologists also find that minorities are more resilient and much less likely to report depression or commit suicide than are whites in the face of negative shocks, perhaps due to a longer trajectory of dealing with negative shocks and challenges.

Another critical issue is the threat and reality of downward mobility for blue-collar whites, particularly in the heartland of the country where manufacturing, mining, and other jobs have hollowed out. Andrew Cherlin of Johns Hopkins University finds that poor black and Hispanic people are much more likely than poor white people to report that they live better than their parents did. Poor whites are more likely to say they live worse than their parents did; they, in particular, seem to be living the erosion of the American dream.

The American problem

Why does this matter? My research from a decade ago – since confirmed by other studies – found that individuals who were optimistic about their futures tended to have better health and employment outcomes. Those who believe in their futures tend to invest in those futures, while those who are consumed with stress, daily struggles and a lack of hope, not only have less means to make such investments, but also have much less confidence that they will pay off.

The starkest marker of lack of hope in the US is a significant increase in premature mortality in the past decade – driven by an increase in suicides and drug and alcohol poisoning and a stalling of progress against heart disease and lung cancer – primarily but not only among middle-aged uneducated white people. Mortality rates for black and Hispanic people, while higher on average than those for whites, continued to fall during the same time period.

The reasons for this trend are multi-faceted. One is the coincidence of an all-too-readily-available supply of drugs such as opioids, heroin and fentanyl, with the shrinking of blue-collar jobs – and identities - primarily due to technological change. Fifteen per cent of prime age males are out of the labour force today; with that figure projected to increase to 25% by 2050. The identity of the blue-collar worker seems to be stronger for white people than for minorities, meanwhile. While there are now increased employment opportunities in services such as health, white males are far less likely to take them up than are their minority counterparts.

Lack of hope also contributes to rising mortality rates, as evidenced in my latest research with Sergio Pinto . On average, individuals with lower optimism for the future are more likely to live in metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) with higher mortality rates for 45- to 54-year-olds.

Desperate people are more likely to die prematurely, but living with a lot of premature death can also erode hope. Higher average levels of optimism in metropolitan areas are also associated with lower premature mortality rates. These same places tend to be more racially diverse, healthier (as gauged by fewer respondents who smoke and more who exercise), and more likely to be urban and economically vibrant.

Technology-driven growth is not unique to the US, and low-skilled workers face challenges in many OECD countries. Yet by contrast, away from the US, they have not had a similar increase in premature mortality. One reason may be stronger social welfare systems – and stronger norms of collective social responsibility for those who fall behind – in Europe.

Ironically, part of the problem may actually be the American dream. Blue-collar white people – whose parents lived the American dream and who expected their children to do so as well – are the ones who seem most devastated by its erosion and yet, on average, tend to vote against government programmes. In contrast, minorities, who have been struggling for years and have more experience multi-tasking on the employment front and relying on family and community support when needed – are more resilient and hopeful, precisely because they still see a chance for moving up the ladder.

There are high costs to being poor in America, where winners win big but losers fall hard. Indeed, the dream, with its focus on individual initiative in a meritocracy, has resulted in far less public support than there is in other countries for safety nets, vocational training, and community support for those with disadvantage or bad luck. Such strategies are woefully necessary now, particularly in the heartland where some of Alger’s characters might have come from, but their kind have long since run out of luck.

Carol Graham is the author of Happiness for All? Unequal Hopes and Lives in Pursuit of the American Dream (Princeton University Press, 2017).

Do you believe the American dream is dead? Please share your experiences in confidence at [email protected]

- Income inequality

- US income inequality

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

A business journal from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

Is the American Dream Dying?

May 2, 2016 • 10 min read.

The idea behind the American Dream — if you work hard, you will get somewhere — is less true than ever as the wealth gap widens, according to James M. Stone, author of 'Five Easy Theses.'

- Public Policy

That income and wealth inequality was a worsening problem for the United States didn’t fully sink in until I was the Insurance Commissioner of Massachusetts in the 1970s. I had grown up believing that America was already pushing the edges of what was possible for mankind and headed steadfastly further in the direction of an inherent and universally admired fairness. We were lucky not to have to live with the inequities of a Latin American banana republic, a European hereditary aristocracy, or an ancient oriental empire to weigh on our consciences. Our country, I was taught, had both a higher level of distributional equity and more social mobility than just about any nation-state in all of history.

Quite a few of us believed then that if we could only overcome race and gender bias, our society would be on the way to near perfection. Looking back, it seems apparent that the perfection many of us had in mind was ill defined, with some seeking a pure, unbridled meritocracy and others preferring the far edge of an egalitarian flat plane — neither of which is in reality a sound destination. Whatever definition of perfection with respect to distributional equity is used, more importantly, it has by now become clear that this country isn’t going to get there, and in fact, if we were ever on the road at all, we missed our turn and we are now headed in the wrong direction.

At the Massachusetts Division of Insurance, the issue that opened my eyes revolved around setting premiums for car insurance on the basis of a policyholder’s socioeconomic status, a technique used in most of the country. Income is not a terribly bad predictor of claims cost and is statistically better than most — and it is easy to find proxies for it that sound like palatable pricing factors. The problem with this approach is twofold: It lacks incentives for responsible driving behavior that could improve outcomes and lower costs for the population as a whole, and it frequently results in charging clean drivers from disadvantaged neighborhoods unaffordable rates while giving bargain prices to drivers with poor records in wealthier areas, thus worsening the disparities.

The deeper I delved into the issue, and the more I learned about our income and wealth distribution generally, the faster my rosy, distorted view of economic equality in the United States fell away. The topic of inequality has stayed high on my list of interests since the Massachusetts government job ended long ago. But it was a source of no small disappointment to discover how small an audience, including among academics, the emerging picture drew until quite recently.

The American dream that “able and hard-working citizens can move upward freely from one [class] to the next … is less true than it used to be.”

Recent events have made it harder to ignore the issue of distributional equity. If you wonder where the Occupy Wall Street movement that arose after the 2008 crash got its steam, despite its singular lack of leadership or focus, consider that the three-year recovery from the recession that followed was absorbed almost in its entirety by the top 1% of the income distribution. The same reality, ironically, may also be lending additional power to the Tea Party movement. Since 2000, income for 70% or more of Americans has actually been flat or declined a little, thanks in part to the financial crisis.

Meanwhile, for the top decile in this millennium, income is up by double digits, despite the crisis. The average net worth of households in the upper 7% rose by 28% in the initial recovery years of 2009 through 2011 while the wealth of the other 93% fell by 4%. It should not be surprising that so many people think the recession isn’t over yet, and some are pretty angry. The only silver lining is that political and scholarly attention is finally being paid to the increasing economic inequality and the fading of our long-admired mobility.

The view over a longer timeline provides no more comfort. The median income in this country hasn’t risen at all in real terms for 40 years. The United States since most of us were born has regularly harvested more wealth than any other nation in the history of the world, but the fruits have been increasingly carried toward the tip of the pyramid. While income in the middle brackets stagnated over the past four decades, income for the upper 1% tripled. As recently as the middle of the 20th century, the share of the United States’ national income taken by the top 10% of income earners was about one-third. Now it is more like 50%. The fortunate pinnacle, the top 1% of all households, received 10% of the nation’s total income in the middle of the 20th century. Now the upper 1% takes about one-quarter of the grand total. If you are in this segment, I hope you can be grateful without believing that this is the way things ought to be.

Meanwhile, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the share of total income held by the bottom 20% of American households, which was never out of the single digits, has fallen by two points. That means that the middle classes have absorbed the loss of fifteen of the national income points that shifted to the possession of the top decile. Another widely quoted measure of growing disparity, affecting mainly the middle class, is the ratio of CEO pay to the average American worker’s pay. This ratio, which stood at about 20 to one when I was young, is now close to 300 to one. These trends are just not healthy for the nation.

“You are not being an alarmist if you fear that lobbyists and superrich contributors have excessive influence nowadays in every aspect of politics.”

I have always used a kind of shorthand to describe our socioeconomic classes. In this categorization, the all-important middle class consists of those people who can live reasonably comfortably if they are willing and able to work and improve their comfort level by harder or better work. The upper class is composed of those folks who can live well without work if they so choose. The lower class consists of those who can’t scratch together enough money to live decently even if they are willing to work hard.

The economics of our society just isn’t working for the middle class, the majority of its citizenry, when those who are willing and able to work cannot better their financial position. This is increasingly becoming the case in the 21st century. The American dream, moreover, has embodied an assumption that able and hard-working citizens can move upward freely from one of these classes to the next, including exits from the lowest classes and access to the top spots, and that sloth or incompetence will lead to a downward class shift. This is less true than it used to be, and it will be less so still as concentration at the pinnacle vacuums the opportunities from the spaces below.

Legitimate worry, moreover, should extend well beyond individual income and wealth imbalances. The growing concentration of corporate power is equally threatening to the values most Americans share. You are not being an alarmist if you fear that lobbyists and superrich contributors have excessive influence nowadays in every aspect of politics. Corporate power in the halls of Congress has waxed and waned over the history of our republic. It is probably greater now than at any time since Boss Tweed and Mark Hanna reigned from behind the scenes. Statistics show that the great majority of elections are won by whoever raises the largest war chest, and a friend of mine who served in the Senate told me that U.S. senators now typically spend about one-third of their time raising money. For House members, with a two-year election cycle, the situation must be worse.

Democracy itself is endangered by this trend. Our treasured form of government is not something to take for granted. The more you learn about governments around the world, the more grateful you should be for our democracy, and the more clearly you should discern what a delicate flower it is. Not only is democracy far from inevitable for all places and all times, it is historically rare and fragile. Look how seldom democracies have occurred and thrived, in both time and place. The United States and Switzerland, after all, have the oldest two functioning democratic republics on the planet. Contrary to what some in our government thought as they tried to transplant our system elsewhere, democracy requires more than selection of leaders by popular elections. A true democracy is characterized by due process, minority rights, an independent press, reservations of various liberties, and effective separation of church and state. Without those essential corollaries, majority voting can become little more than what a wise humorist suggested: a dozen wolves and a sheep voting on what to have for lunch.

“Democracy requires as a precondition a healthy measure of pluralism — an underlying society with a wide distribution of money and power.”

At its fundamental core, democracy requires as a precondition a healthy measure of pluralism — an underlying society with a wide distribution of money and power. Although they are nicely symbiotic, democracy and a market economy are not the same, and democracy is certainly not identical to prosperity. America’s attachment to a market economy is relatively robust and its prosperity secure … as long as we can maintain our culture of challenge and innovation.

The threat is that we may find ourselves living in a market economy where a tiny fraction of the people and a small number of institutions reap virtually all of the rewards and make all of the social and economic policy decisions, presumably with a bias toward serving their own interests. This would be a democracy in name only. True democracy is surely not the most natural form of government for human beings, and perhaps it is only barely compatible with human nature, but it may well be mankind’s greatest invention. And the growing degree of concentration of wealth and power in our country today threatens its continuation. If our pluralism erodes, with it will vanish America’s brightest gem.

Some political economists will tell you that wealth and income disparities don’t matter because large distinctions in a mobile society spur ambition to succeed. But America is rapidly becoming less mobile as the distinctions grow. More wealth held tightly in the hands of fewer families implies a diminishing reward for hard, honest work on the part of everyone else.

More From Knowledge at Wharton

How Social Insurance Drives Credit Card Debt

How Financial Literacy Helps Underserved Students | David Musto

Cass Sunstein on Nudging, Sludge, and the Power of ‘Dishabituation’

Looking for more insights.

Sign up to stay informed about our latest article releases.

American Compass

- Compass Point

- The Edgerton Essays

- Talkin’ (Policy) Shop

- Globalization

- Financialization

- Understanding America

- Conservative Economics Family, community, and industry provide the foundation for our nation’s liberty and prosperity -->

- Productive Markets Family, community, and industry provide the foundation for our nation’s liberty and prosperity -->

- Supportive Communities Family, community, and industry provide the foundation for our nation’s liberty and prosperity -->

- Responsive Politics Family, community, and industry provide the foundation for our nation’s liberty and prosperity -->

- Annual Report

The American Dream Isn’t Dead, It’s Just Misunderstood

Recommended reading.

Some people believe the American Dream is dead and the game is rigged against them.

That isn’t my mindset or attitude. In order to fulfill your dreams, you must aspire to be what you desire. That is the American Dream, to me. And I think some people don’t understand what fulfilling that American Dream can take.

I live in Washington, D.C., and am surrounded by ambitious people aspiring to be politicians, writers, and journalists. Many of them are immigrants that came from repressive places where the government decides what your fate will be. In America, you’re not forced to work, you can choose to hold a cup panhandling or you can take risks and start a business. Trust me, I know people who have done both.

Part of the problem is that too many equate the American Dream with doing well—making money, the big house, the nice cars. Too many Americans suffer from a sense of entitlement, wanting instant gratification, rather than paying their dues. They envy someone running a business, who has two cars and a trophy wife. You don’t see the behind-the-scenes work it took to get there. You don’t know how someone may have started his business, working in his garage, may have spent days in the soup line and was mocked for thinking outside of the box.

Ten years ago I came to Washington, D.C., with $10 dollars, broke and homeless. I was unemployed and unemployable. I hadn’t bathed in weeks and the only prospect I had was to beg or sell a newspaper written and sold by the homeless, Street Sense . If anyone had a reason to give up, it was me. Many had and they have passed away. Being proud and competitive, I refused to be a beggar and charity case and saw that selling papers was better than panhandling.

Make sure your dreams are your own, not others’ expectations. Dreams start with plans and come down to choices. If you let others set your expectations for you, you’re letting them make your plans for you. Do I become a comfortable slave or do I take risks by becoming someone who is independent?

Sometimes that means marching to the beat of your own drum. It also means having a positive mindset. If you go into something with the mindset that your task is impossible, you’ll find yourself just wasting another day in bed dreaming. America will give you an opportunity, but you have to be the one to take action.

When it comes to solutions for those facing poverty, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. There isn’t one factor or stereotype. I was lucky to find organizations such as Street Sense, S.O.M.E. (So Others May Eat), Miriam’s Kitchen, and Bread for the City. Being addicted, I never went to rehabilitation, but found a sponsor at AA meetings and haven’t taken a drink in 12 years. Instead of complaining about my first job, which wasn’t great, I used it as a resume-builder. I focused on staying away from negative people and looking at the big picture.

Following those dreams, being able to call your own shots and defining your own meaning of success, also means not taking rejection personally. I always say to myself, I’m sure the Apostles Paul, Peter, and Timothy were rejected, but eventually, they found the right audience to hear their message. Some of the greatest books in history, such as Gone With The Wind and Lord of the Flies have been rejected. It’s one thing to dream but don’t complain about America if you are not willing to fight, get knocked down, and pick yourself back up again.

Lastly, despite what you read or hear, America is still the land of opportunity. But at the same time, you must be realistic. I’m 5’11” and can’t jump or dribble, so I don’t think the NBA will be calling anytime soon. Again—the Dream isn’t about having the most or being the best. It’s about wanting to make the most of yourself without anyone telling you what you need to be doing.

As you can see, I’m an optimist. I define success as living my life on my terms. I’ve worked in companies that paid me handsomely and wanted to jump off a bridge. I was miserable living off the pressures of living by someone else’s definition of success. I was happier homeless than having the government, politicians, or corporate bosses imposing themselves on what I can or cannot do.

Follow your dreams and you will find success in America. It might not be success as you think of it right now. The American Dream isn’t about getting rich. It’s about living life the way you want to, and that is something we still have the freedom to choose every single day.

Edgerton Essays feature the perspectives of working-class Americans on the challenges facing their communities and families and the debates central to the nation’s politics. If you or someone you know might be interested in contributing to the series, click here for more information.

Recommended Reading

A Dream Achieved—Through Mere Luck

My American Dream feels stolen, like I purchased it with the blood of brothers and enemies.

COVID’s Toll on the American Dream

The American Dream—people have hung on to those three little words for decades, passed them down for generations. But it’s hard to see how we can believe in the dream right now.

American Scream

American Compass’s Wells King reviews Michael Strain’s new book The American Dream Is Not Dead (But Populism Could Kill It).

Join our mailing list to receive our latest research, news, and commentary.

Subscribe to receive updates, previews, and more.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Waking Up from the American Dream

By Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

If you are an undocumented person anywhere in America, some of the things you do to make a dignified life for yourself and your loved ones are illegal. Others require a special set of skills. The elders know some great tricks—crossing deserts in the dead of night, studying the Rio Grande for weeks to find the shallowest bend of river to cross, getting a job on their first day in the country, finding apartments that don’t need a lease, learning English at public libraries, community colleges, or from “Frasier.” I would not have been able to do a single thing that the elders have done. But the elders often have only one hope for survival, which we tend not to mention. I’m talking about children. And no, it’s not an “anchor baby” thing. Our parents have kids for the same reasons as most people, but their sacrifice for us is impossible to articulate, and its weight is felt deep down, in the body. That is the pact between immigrants and their children in America: they give us a better life, and we spend the rest of that life figuring out how much of our flesh will pay off the debt.

I am a first-generation immigrant, undocumented for most of my life, then on DACA , now a permanent resident. But my real identity, the one that follows me around like a migraine, is that I am the daughter of immigrants. As such, I have some skills of my own.

You pick them up young. Something we always hear about, because Americans love this shit, is that immigrant children often translate for their parents. I began doing this as a little girl, because I lost my accent, dumb luck, and because I was adorable in the way that adults like, which is to say I had large, frightened eyes and a flamboyant vocabulary. As soon as doctors or teachers began talking, I felt my parents’ nervous energy, and I’d either answer for them or interpret their response. It was like my little Model U.N. job. I was around seven. My career as a professional daughter of immigrants had begun.

In my teens, I began to specialize. I became a performance artist. I accompanied my parents to places where I knew they would be discriminated against, and where I could insure that their rights would be granted. If a bank teller wasn’t accepting their I.D., I’d stroll in with an oversized Forever 21 blazer, red lipstick, a slicked-back bun, and fresh Stan Smiths. I brought a pleather folder and made sure my handshake broke bones. Sometimes I appealed to decency, sometimes to law, sometimes to God. Sometimes I leaned back in my chair, like a sexy gangster, and said, “So, you tell me how you want my mom to survive in this country without a bank account. You close at four, but I have all the time in the world.” Then I’d wink. It was vaudeville, but it worked.

My parents came to America in their early twenties, naïve about what awaited them. Back in Ecuador, they had encountered images of a wealthy nation—the requisite flashes of Clint Eastwood and the New York City skyline—and heard stories about migrants who had done O.K. for themselves there. But my parents were not starry-eyed people. They were just kids, lost and reckless, running away from the dead ends around them.

My father is the only son of a callous mother and an absent father. My mother, the result of her mother’s rape, grew up cared for by an aunt and uncle. When she married my father, it was for the reasons a lot of women marry: for love, and to escape. The day I was born, she once told me, was the happiest day of her life.

Soon after that, my parents, owners of a small auto-body business, found themselves in debt. When I was eighteen months old, they left me with family and settled in Brooklyn, hoping to work for a year and move back once they’d saved up some money. I haven’t asked them much about this time—I’ve never felt the urge—but I know that one year became three. I also know that they began to be lured by the prospect of better opportunities for their daughter. Teachers had remarked that I was talented. My mother, especially, felt that Ecuador was not the place for me. She knew how the country would limit the woman she imagined I would become—Hillary Clinton, perhaps, or Princess Di.

My parents sent loving letters to Ecuador. They said that they were facing a range of hardships so that I could have a better life. They said that we would reunite soon, though the date was unspecified. They said that I had to behave, not walk into traffic—I seem to have developed a habit of doing this—and work hard, so they could send me little gifts and chocolates. I was a toddler, but I understood. My parents left to give me things, and I had to do other things in order to repay them. It was simple math.

They sent for me when I was just shy of five years old. I arrived at J.F.K. airport. My father, who seemed like a total stranger, ran to me and picked me up and kissed me, and my mother looked on and wept. I recall thinking she was pretty, and being embarrassed by the attention. They had brought roses, Teddy bears, and Tweety Bird balloons.

Getting to know one another was easy enough. My father liked to read and lecture, and had a bad temper. My mother was soft-spoken around him but funny and mean—like a drag queen—with me. She liked Vogue . I was enrolled in a Catholic school and quickly learned English—through immersion, but also through “Reading Rainbow” and a Franklin talking dictionary that my father bought me. It gave me a colorful vocabulary and weirdly over-enunciated diction. If I typed the right terms, it even gave me erotica.

Meanwhile, I had confirmed that my parents were not tony expats. At home, meals could be rice and a fried egg. We sometimes hid from our landlord by crouching next to my bed and drawing the blinds. My father had started out driving a cab, but after 9/11, when the governor revoked the driver’s licenses of undocumented immigrants, he began working as a deliveryman, carrying meals to Wall Street executives, the plastic bags slicing into his fingers. Some of those executives forced him to ride on freight elevators. Others tipped him in spare change.

My mother worked in a factory. For seven days a week, sometimes in twelve-hour shifts, she sewed in a heat that caught in your throat like lint, while her bosses, also immigrants, hurled racist slurs at her. Some days I sat on the factory floor, making dolls with swatches of fabric, cosplaying childhood. I didn’t put a lot of effort into making the dolls—I sort of just screwed around, with an eye on my mom at her sewing station, stiffening whenever her supervisor came by to see how fast she was working. What could I do to protect her? Well, murder, I guess.

Our problem appeared to be poverty, which even then, before I’d seen “Rent,” seemed glamorous, or at least normal. All the protagonists in the books I read were poor. Ramona Quimby on Klickitat Street, the kids in “Five Little Peppers and How They Grew.” Every fictional child was hungry, an orphan, or tubercular. But there was something else setting us apart. At school, I looked at my nonwhite classmates and wondered how their parents could be nurses, or own houses, or leave the country on vacation. It was none of my business—everyone in New York had secrets—but I cautiously gathered intel, toothpick in mouth. I finally cracked the case when I tried to apply to an essay contest and asked my parents for my Social Security number. My father was probably reading a newspaper, and I doubt he even looked up to say, “We don’t have papers, so we don’t have a Social.”

It was not traumatic. I turned on our computer, waited for the dial-up, and searched what it meant not to have a Social Security number. “Undocumented immigrant” had not yet entered the discourse. Back then, the politically correct term, the term I saw online, was “illegal immigrant,” which grated—it was hurtful in a clinical way, like having your teeth drilled. Various angry comments sections offered another option: illegal alien . I knew it was form language, legalese meant to wound me, but it didn’t. It was punk as hell. We were hated , and maybe not entirely of this world. I had just discovered Kurt Cobain.

Obviously, I learned that my parents and I could be deported at any time. Was that scary? Sure. But a deportation still seemed like spy-movie stuff. And, luckily, I had an ally. My brother was born when I was ten years old. He was our family’s first citizen, and he was named after a captain of the New York Yankees. Before he was old enough to appreciate art, I took him to the Met. I introduced him to “S.N.L.” and “Letterman” and “Fun Home” and “Persepolis”—all the things I felt an upper-middle-class parent would do—so that he could thrive at school, get a great job, and make money. We would need to armor our parents with our success.

We moved to Queens, and I entered high school. One day, my dad heard about a new bill in Congress on Spanish radio. It was called the DREAM Act, and it proposed a path to legalization for undocumented kids who had gone to school here or served in the military. My dad guaranteed that it’d pass by the time I graduated. I never react to good news—stoicism is part of the brand—but I was optimistic. The bill was bipartisan. John McCain supported it, and I knew he had been a P.O.W., and that made me feel connected to a real American hero. Each time I saw an “R” next to a sponsor’s name my heart fluttered with joy. People who were supposed to hate me had now decided to love me.

But the bill was rejected and reintroduced, again and again, for years. It never passed. And, in a distinctly American twist, its gauzy rhetoric was all that survived. Now there was a new term on the block: “Dreamers.” Politicians began to use it to refer to the “good” children of immigrants, the ones who did well in school and stayed off the mean streets—the innocents. There are about a million undocumented children in America. The non-innocents, one presumes, are the ones in cages, covered in foil blankets, or lost, disappeared by the government.

I never called myself a Dreamer. The word was saccharine and dumb, and it yoked basic human rights to getting an A on a report card. Dreamers couldn’t flunk out of high school, or have D.U.I.s, or work at McDonald’s. Those kids lived with the pressure of needing a literal miracle in order to save their families, but the miracle didn’t happen, because the odds were against them, because the odds were against all of us. And so America decided that they didn’t deserve an I.D.

Link copied

The Dream, it turned out, needed to demonize others in order to help the chosen few. Our parents, too, would be sacrificed. The price of our innocence was the guilt of our loved ones. Jeff Sessions, while he was Attorney General, suggested that we had been trafficked against our will. People actually pitied me because my parents brought me to America. Without even consulting me.

The irony, of course, is that the Dream was our inheritance. We were Dreamers because our parents had dreams.

It’s painful to think about this. My mother, an aspiring interior designer, has gone twenty-eight years without a sick day. My dad, who loves problem-solving, has spent his life wanting a restaurant. He’s a talented cook and a brilliant manager, and he often did the work of his actual managers for them. But, without papers, he could advance only so far in a job. He needed to be paid in cash; he could never receive benefits.

He often used a soccer metaphor to describe our journey in America. Our family was a team, but I scored the goals. Everything my family did was, in some sense, a pass to me. Then the American Dream could be mine, and then we could start passing to my brother. That’s how my dad explained his limp every night, his feet blistered from speed-running deliveries. It’s why we sometimes didn’t have money for electricity or shampoo. Those were fouls. Sometimes my parents did tricky things to survive that you’ll never know about. Those were nutmegs. In 2015, when the U.S. women’s team won the World Cup, my dad went to the parade and sent me a selfie. “Girl power!” the text read.

My father is a passionate, diatribe-loving feminist, though his feminism often seems to exclude my mother. When I was in elementary school, he would take me to the local branch of the Queens Public Library and check out the memoir of Rosalía Arteaga Serrano, the only female President in Ecuador’s history. Serrano was ousted from office, seemingly because she was a woman. My father would read aloud from the book for hours, pausing to tell me that I’d need to toughen up. He would read from dictators’ speeches—not for the politics, but for the power of persuasive oratory. We went to the library nearly every weekend for thirteen years.

My mother left her factory job to give me, the anointed one, full-time academic support. She pulled all-nighters to help me make extravagant posters. She grilled me with vocabulary flash cards, struggling to pronounce the words but laughing and slapping me with pillows if I got something wrong. I aced the language portions of my PSATs and SATs, partly because of luck, and partly because of my parents’ locally controversial refusal to let me do household chores, ever, because they wanted me to be reading, always reading, instead.

If this all seems strategic, it should. The American Dream doesn’t just happen to cheery Pollyannas. It happens to iconoclasts with a plan and a certain amount of cunning. The first time I encountered the idea of the Dream, it was in English class, discussing “The Great Gatsby.” My classmates all thought that Gatsby seemed sort of sad, a pathetic figure. I adored him. He created his own persona, made a fortune in an informal economy, and lived a quiet, paranoid, reclusive life. Most of all, he longed. He stood at the edge of Long Island Sound, longing for Daisy, and I took the train uptown to Columbia University and looked out at the campus, hoping it could one day be mine. At the time, it was functionally impossible for undocumented students to enroll at Columbia. The same held for many schools. Keep dreaming, my parents said.

I did. I was valedictorian of my class, miraculously got into Harvard, and was tapped to join a secret society that once included T. S. Eliot and Wallace Stevens. I was the only Latina inducted, I think, and I was very chill when an English-Spanish dictionary appeared in our club bathroom after I started going to teas. When I graduated, in 2011, our country was deporting people at record rates. I knew that I needed to add even more of a golden flicker to my illegality, so that if I was deported, or if my parents were deported, we would not go in the middle of the night, in silence, anonymously, as Americans next door watched another episode of “The Bachelor.” So I began writing, with the explicit aim of entering the canon. I wrote a book about undocumented immigrants, approaching them not as shadowy victims or gilded heroes but as people, flawed and complex. It was reviewed well, nominated for things. A President commended it.

But it’s hard to feel anything. My parents remain poor and undocumented. I cannot protect them with prizes or grades. My father sobbed when I handed him my diploma, but it was not the piece of paper that would make it all better, no matter how heavy the stock.

By the time I was in grad school, my parents’ thirty-year marriage was over. They had spent most of those years in America, with their heads down and their bodies broken; it was hard not to see the split as inevitable. My mom called me to say she’d had enough. My brother supported her decision. I talked to each parent, and helped them mutually agree on a date. On a Tuesday night, my father moved out, leaving his old parenting books behind, while my mom and brother were at church. I asked my father to text my brother that he loved him. I think he texted him exactly that. Then I collapsed onto the floor beneath an open drawer of knives, texted my partner to come help me, and convulsed in sobs.

After that, my mom became depressed. I did hours of research and found her a highly qualified, trauma-informed psychiatrist, a Spanish speaker who charged on a sliding scale I could afford. My mom got on Lexapro, which helped. She also started a job that makes her very happy. In order to find her that job, I took a Klonopin and browsed Craigslist for hours each day, e-mailing dozens of people, being vague about legal status in a clever but truthful way. I impersonated her in phone interviews, hanging off my couch, the blood rushing to my head, struggling not to do an offensive accent.

You know how, when you get a migraine, you regret how stupid you were for taking those sweet, painless days for granted? Although my days are hard, I understand that I’m living in an era of painlessness, and that a time will come when I look back and wonder why I was such a stupid, whining fool. My mom’s job involves hard manual labor, sometimes in the snow or the rain. I got her a real winter coat, her first, from Eddie Bauer. I got her a pair of Hunter boots. These were things she needed, things I had seen on women her age on the subway, their hands bearing bags from Whole Foods. My mom’s hands are arthritic. She sends me pictures of them covered in bandages.

My brother and I now have a pact: neither of us can die, because then the other would be stuck with our parents. My brother is twenty-two, still in college, and living with my mom. He, too, has some skills. He is gentle, kind, and excellent at deëscalating conflict. He mediated my parents’ arguments for years. He has also never tried to change them, which I have, through a regimen of therapy, books, and cheesy Instagram quotes. So we’ve decided that, in the long term, since his goal is to get a job, get married, have kids, and stay in Queens, he’ll invite Mom to move in with him, to help take care of the grandkids. He’ll handle the emotional labor, since it doesn’t traumatize him. And I’ll handle the financial support, since it doesn’t traumatize me.

I love my parents. I know I love them. But what I feel for them daily is a mixture of terror, panic, obligation, sorrow, anger, pity, and a shame so hot that I need to lie face down, in my underwear, on very cold sheets. Many Americans have vulnerable parents, and strive to succeed in order to save them. I hold those people in the highest regard. But the undocumented face a unique burden, due to scorn and a lack of support from the government. Because our parents made a choice—the choice to migrate—few people pity them, or wonder whether restitution should be made for decades of exploitation. That choice, the original sin, is why our parents were thrown out of paradise. They were tempted by curiosity and hunger, by fleshly desires.

And so we return to the debt. However my parents suffer in their final years will be related to their migration—to their toil in this country, to their lack of health care and housing support, to psychic fatigue. They were able, because of that sacrifice, to give me their version of the Dream: an education, a New York accent, a life that can better itself. But that life does not fully belong to me. My version of the American Dream is seeing them age with dignity, being able to help them retire, and keeping them from being pushed onto train tracks in a random hate crime. For us, gratitude and guilt feel almost identical. Love is difficult to separate from self-erasure. All we can give one another is ourselves.

Scholars often write about the harm that’s done when children become caretakers, but they’re reluctant to do so when it comes to immigrants. For us, they say, this situation is cultural . Because we grow up in tight-knit families. Because we respect our elders. In fact, it’s just the means of living that’s available to us. It’s a survival mechanism, a mutual-aid society at the family level. There is culture, and then there is adaptation to precarity and surveillance. If we are lost in the promised land, perhaps it’s because the ground has never quite seemed solid beneath our feet.

When I was a kid, my mother found a crystal heart in my father’s taxi. The light that came through it was pretty, shimmering, like a gasoline spill on the road. She put it in her jewelry box, and sometimes we’d take out the box, spill the contents onto my pink twin bed, and admire what we both thought was a heart-shaped diamond. I grew up, I went to college. I often heard of kids who had inherited their grandmother’s heirlooms, and I sincerely believed that there were jewels in my family, too. Then, a few years ago, my partner and I visited my mom, and she spilled out her box. She gave me a few items I cherish: a nameplate bracelet in white, yellow, and rose gold, and the thick gold hoop earrings that she wore when she first moved to Brooklyn. Everything else was costume jewelry. I couldn’t find the heart.