What Is A Warrant In Writing? (Explained + 20 Examples)

Ever wondered how writers make their claims stick?

That’s where warrants come in, bridging the gap between evidence and conclusion.

What is a warrant in writing?

A warrant in writing connects a claim to evidence, serving as the underlying logic, ethical principle, or emotional appeal that makes an argument persuasive. It’s the bridge that ensures an argument’s coherence and strength.

In this guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know about warrants in writing.

What Is a Warrant in Writing (Long Explanation)?

Table of Contents

When we talk about a warrant in writing, we’re diving into the backbone of persuasive and argumentative writing.

It’s not the flashy evidence or the bold claim that gets the spotlight.

Rather, it’s the unsung hero that connects the two, ensuring your argument stands strong and coherent.

Through trial and error, I’ve learned that a well-crafted warrant can turn a skeptical reader into a believer, highlighting the nuanced art of persuasion that goes beyond mere facts.

Imagine you’re building a bridge.

Your claim is on one side, your evidence on the other, and the warrant is what lies beneath, holding it all together.

It answers the silent question of “Why does this evidence support my claim?” without which your argument might just fall into the water.

Warrants are based on logic, ethics, or emotions, tailored to your audience’s beliefs and values.

They’re not always explicitly stated but are crucial for the argument’s acceptability.

Think of them as the glue that binds your argument, making it not just a collection of statements but a coherent, persuasive message.

Types of Warrants in Writing (10 Types)

Warrants come in various forms, each serving a unique purpose in strengthening your argument.

Let’s explore the ten types of warrants that can transform your writing:

- Logical Warrants – These are grounded in logic, appealing to the reader’s sense of reason.

- Ethical Warrants – These appeal to the reader’s sense of morality and ethics.

- Emotional Warrants – Aimed at stirring the reader’s emotions.

- Authoritative Warrants – Rely on the credibility of the source or author.

- Analogical Warrants – Use analogies to draw parallels between concepts.

- Causal Warrants – Establish a cause-effect relationship.

- Generalization Warrants – Apply a general principle to a specific case.

- Sign Warrants – Use signs or indicators as evidence for the claim.

- Analogy Warrants – Similar to analogical but often use metaphors or similes for comparison.

- Statistical Warrants – Use statistics and numerical data to support the claim.

Understanding these types is crucial for effectively incorporating warrants into your writing, ensuring your arguments are not only heard but resonate with your audience.

20 Examples of Warrants in Writing

Before we dive into the examples, it’s essential to grasp the significance of each warrant type.

By understanding and applying these warrants, you can enhance the persuasiveness of your writing, making your arguments more compelling and impactful.

Logical Warrants: The Bridge of Reason

Imagine arguing that a well-balanced diet improves academic performance.

The logical warrant here connects the nutritional benefits of a balanced diet to enhanced brain function and, consequently, better academic outcomes.

It’s the reasoning that if your body gets the right nutrients, your brain operates more efficiently.

And that leads to improved academic performance.

Ethical Warrants: The Moral Compass

Consider the claim that companies should adopt more sustainable practices.

The ethical warrant appeals to the moral obligation of preserving the environment for future generations.

It’s the understanding that, as stewards of the planet, companies have a moral duty to minimize environmental harm, making the argument not just logical but morally compelling.

Emotional Warrants: The Heart’s Argument

Take the argument that animal shelters should receive more funding.

The emotional warrant plays on the audience’s compassion for animals, linking the plight of shelter animals to the emotional response of the audience.

It’s the heart-tugging connection that motivates action, not just through logic but through feeling.

Authoritative Warrants: The Voice of Credibility

Arguing that vaccinations are safe and effective might draw on authoritative warrants.

This warrant relies on the credibility of medical institutions and experts, asserting that if trusted sources endorse vaccinations, they must be safe and beneficial.

It’s the trust in authority that bolsters the argument’s weight.

Analogical Warrants: Connecting Dots with Similarity

If arguing for the importance of cybersecurity measures in small businesses, you might use an analogical warrant comparing cyber threats to burglaries.

This analogy highlights the necessity of protective measures, both physical and digital, to safeguard valuable assets.

Analogical warrants make the argument relatable and understandable.

Causal Warrants: Cause and Effect

In arguing that excessive screen time leads to poor sleep patterns, the causal warrant establishes a cause-effect relationship between screen time and sleep quality.

It’s the logical link that prolonged exposure to screens before bedtime disrupts sleep.

Casual warrants ground the argument in a cause-and-effect reality.

Generalization Warrants: The Broad Stroke

When claiming that reading enhances empathy, a generalization warrant might apply the broad principle that exposure to diverse perspectives through literature broadens one’s understanding and acceptance of different life experiences.

This warrant generalizes the benefit of reading to a wider application.

It suggests that engaging with a variety of characters and stories inherently fosters empathy among readers.

Sign Warrants: Reading the Signs

Consider the argument that a thriving local arts scene indicates a city’s economic health.

The sign warrant here uses the vibrancy of the arts community as an indicator or sign of broader economic prosperity.

It’s the interpretation of thriving cultural initiatives as evidence of sufficient disposable income and investment in community well-being, linking cultural vibrancy to economic health.

Analogy Warrants: Seeing in a New Light

In advocating for renewable energy sources, an analogy warrant might compare the transition from fossil fuels to renewables to upgrading from an old, inefficient car to a modern, fuel-efficient model.

This analogy makes the concept more accessible and relatable.

Analogy warrants illustrate the benefits of modernization and efficiency in energy sources through a familiar scenario.

Statistical Warrants: The Power of Numbers

This warrant leans on numerical data to substantiate the claim.

Arguing for the effectiveness of a new teaching method, a statistical warrant could highlight improved test scores in classes where the method was implemented.

These warrants offers concrete evidence that the new teaching approach leads to better academic outcomes.

Generalization Warrants: The Universal Principle

The warrant suggests that the benefits observed in the past are likely to recur under similar systems.

When arguing that democracy is the most effective form of government, a generalization warrant might draw from historical examples where democratic systems led to prosperous and stable societies.

This warrant applies the broad principle that, given the success of democracy across various contexts and times, it can be considered the best form of governance.

It’s a leap from specific historical instances to a universal conclusion.

Sign Warrants: The Indicator

In the debate over economic policies, one might claim that low unemployment rates signal a healthy economy.

The sign warrant here interprets low unemployment as an indicator of economic strength, suggesting that when more people are employed, it reflects well on the economic policies in place.

This warrant relies on the observable condition (employment rates) as a sign of broader economic health.

It makes a case for the effectiveness of current policies.

Analogy Warrants: Visual Metaphors

Advocating for regular breaks from digital devices, an analogy warrant could compare digital consumption to eating junk food.

For example, just as the latter requires moderation to maintain physical health, the former needs limits to preserve mental well-being.

This analogy helps audiences understand the concept of digital detox by relating it to a familiar practice of dietary moderation, enhancing the argument’s relatability and persuasiveness.

Statistical Warrants: Facts and Figures

This approach uses hard numbers to demonstrate the direct consequences of inaction.

Presenting an argument for urgent action on climate change, a statistical warrant might utilize data showing rising global temperatures and increasing frequency of natural disasters.

It aims to convince skeptics through undeniable evidence that climate change is not only real but also an immediate threat.

Logical Warrants: Deductive Reasoning

This warrant connects the dots between individual immunization and community health benefits.

In discussions about public health, arguing that vaccinations prevent widespread outbreaks relies on the logical warrant that vaccines build herd immunity, making it harder for diseases to spread.

Logical warrants employ deductive reasoning to make a case for widespread vaccination programs.

Ethical Warrants: The Right Thing to Do

Arguing for equal access to education, the ethical warrant might stem from the belief that education is a fundamental human right.

This warrant appeals to the sense of fairness and justice, positing that denying anyone access to education is morally wrong.

It’s an argument built on the ethical principle that equality in education is not just beneficial but a moral imperative.

Emotional Warrants: Pathos in Play

When making a case for conservation efforts, an emotional warrant could highlight the plight of endangered species facing extinction.

By evoking empathy for these animals, the warrant seeks to motivate action based on emotional response.

You can leverage the power of pathos to make the argument for conservation not just logical but emotionally compelling.

In my own writing, I’ve discovered that the most compelling arguments are those where the warrant is implicitly understood, yet powerfully resonant with the audience’s core beliefs.

Authoritative Warrants: Expert Endorsements

In advocating for a new health guideline, using authoritative warrants involves citing recommendations from health organizations or experts.

This type of warrant leans on the credibility and expertise of authorities in the field.

The warrant suggests that if such entities endorse a guideline, it is based on solid research and should be followed.

It’s an appeal to authority that lends weight to the argument through expert endorsement.

Causal Warrants: Tracing Effects to Causes

Arguing that social media can result in more loneliness and isolation, a causal warrant examines the effect (loneliness) and traces it back to its cause (social media usage).

This warrant establishes a direct link between the cause and effect.

Casual warrants offer a logical explanation for how too much social media exposure can disrupt and decrease your mental health.

Analogical Warrants: Bridging Concepts

In discussions about governance and policy, comparing the state to a ship and its government to the crew provides an analogical warrant that governance requires cooperation and direction, much like navigating a ship.

This analogy helps illustrate the complexity of governance and the importance of unified direction and teamwork.

Analogical warrants make the argument more accessible and understandable through the comparison.

Here is a good video about warrants in writing:

Final Thoughts: What Is a Warrant in Writing?

Understanding warrants is key to unlocking the full potential of your arguments.

Reflecting on my writing journey, I’ve come to appreciate that mastering the use of warrants is akin to fine-tuning a musical instrument—it’s delicate, requires practice, and when done right, makes your argument sing.

Read This Next:

- 50 Best Counterclaim Transition Words (+ Examples)

- What Is A Personal Account In Writing? (47 Examples)

- What Is A Lens In Writing? (The Ultimate Guide)

- What Is On-Demand Writing? (Explained with Examples

Argumentation and Persuasion

Sometimes an argument needs further reinforcement through the use of what is known as a warrant, which is an underlying belief that connects a reason and the claim. Usually it is unnecessary to include warrants in an argument since the audience will generally also hold those beliefs, but there are occasions when they are critical to use, such as:

- If the audience is outside of the discourse community, so it is not (as) familiar with the topic and needs additional information;

- If the reason is a new way of thinking or is heavily debated; and

- If the audience is likely to be (highly) resistant to the reason.

Including a warrant when any of these apply can make the difference between whether the argument is successful or unsuccessful.

Take, for example, the following paragraph, written to support the claim that bullying should be collaboratively addressed by educators, parents, and those who experience bullying:

When an adolescent is bullied, he/she often undergoes behavioral and emotional changes, changes that can pose significant harm to him/her as well as others. For example, sometimes the young person who is bullied will abuse substances in order to cope with what he/she is going through, as Litwiller and Brausch (2013) explain: “Several painful and provocative behaviors have been identified consistently as behaviors that relate to both bullying and adolescent suicidal behavior. Of all such risk behaviors, alcohol and/or illicit drug use has most frequently been shown to relate” (p. 676.). If these behaviors go unnoticed, then the person being bullied is likely to continue engaging in the alcohol and/or drug use, which can lead to further consequences for him/her as well as others. Hinduja and Patchin (2013) explain that “bullying (offline and online) has been tied to a host of other negative psychosocial and behavioral outcomes such as suicidal ideation, dropping out of school, aggression and fighting…and carrying a weapon to school” (p. 712). All of these outcomes affect not only the individual being bullied, but also those around him/her, with the potential for violence to occur in the school setting. Ignoring the effects of bullying is not an option, then, and bullying must be addressed by all parties involved.

In the paragraph, the first sentence is the topic sentence, which establishes a reason to support the claim and prepares the reader for the content that will appear in the paragraph. The next sentence then offers an example of the changes the topic sentence refers to, leading into the third sentence that integrates source material to show that substance abuse is indeed one of the behavioral changes that occur. At this point in the paragraph, we have been provided a reason to support the claim as well as evidence that supports the reason, and as the paragraph continues we are given additional examples and source material to demonstrate why the reason is a sound reason to support the claim. The paragraph then concludes by reinforcing the claim, asserting that the harm these changes present to the person who is bullied as well as others makes it critical for all relevant parties to address bullying. Presumably, for most readers, the paragraph represents a clear chain of reasoning, because if bullying presents a threat to the person who is bullied as well as those around him/her, then it is sensible to claim that the bullying should be stopped; further, since in many cases the bullied will be unable to end the abuse himself/herself, it is necessary for others in positions of power to step in.

However, some readers may not think that just because there are potential consequences of bullying for the bullied as well as those around him/her that educators, parents, and the bullied should work together to end the bullying. Instead, some readers may think that stopping bullying is the responsibility of educators and/or parents alone since adolescents are not in the same position of power as these other parties, and the bullying may only escalate if the bullied try to end it. Others may think that, depending on how the bullying is occurring (such as if it is limited to online bullying outside of school grounds) that it is beyond the scope and power of educators to step in, leaving the burden for parents and/or their children who are experiencing the bullying. For these readers then, a warrant would be necessary to demonstrate why the reason clearly supports the claim; otherwise, they would be unpersuaded by this part of the argument—and possibly the argument overall, depending on how central the reason was to supporting the claim.

Thus, when developing your argument you must keep in mind that its structure is sort of like the structure of a building. There are certain parts that are essential (i.e., the claim, reasons, and evidence, just like the foundation, walls, and entry/exit routes), whereas other parts may be useful, but are not always needed (i.e., counterarguments, acknowledgment and response, and warrants, just like upgrades such as heated flooring).

- Counterarguments, Acknowledgement and Response, and Warrants. Authored by : Karla Lyles and Jeanine Rauch. Provided by : University of Mississippi. Project : WRIT 250 Committee OER Project. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Organizing Your Argument

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

How can I effectively present my argument?

In order for your argument to be persuasive, it must use an organizational structure that the audience perceives as both logical and easy to parse. Three argumentative methods —the Toulmin Method , Classical Method , and Rogerian Method — give guidance for how to organize the points in an argument.

Note that these are only three of the most popular models for organizing an argument. Alternatives exist. Be sure to consult your instructor and/or defer to your assignment’s directions if you’re unsure which to use (if any).

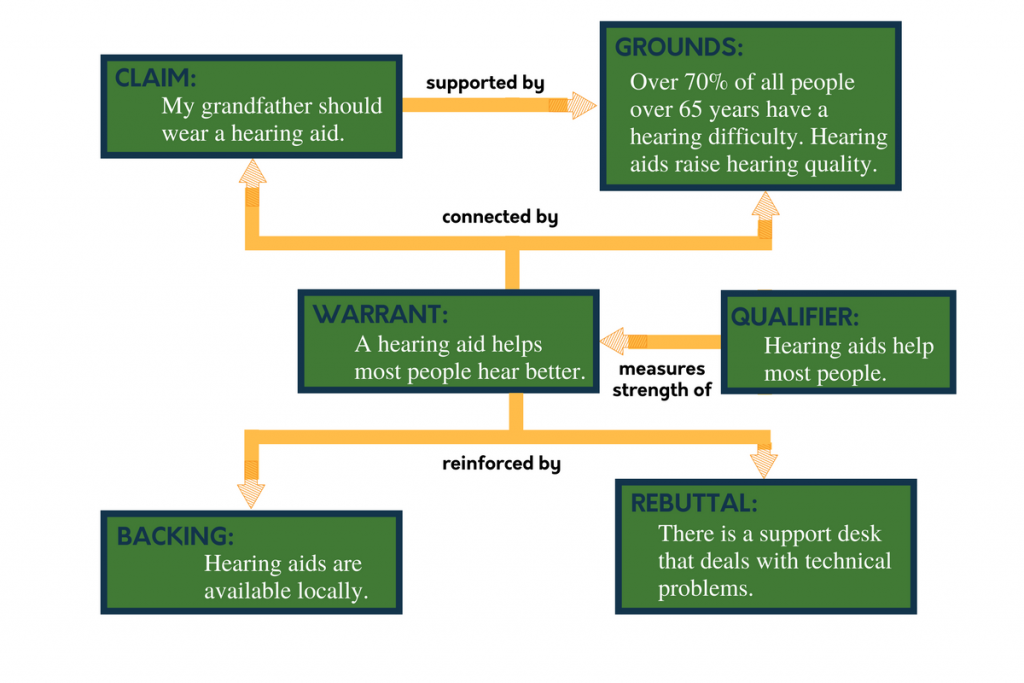

Toulmin Method

The Toulmin Method is a formula that allows writers to build a sturdy logical foundation for their arguments. First proposed by author Stephen Toulmin in The Uses of Argument (1958), the Toulmin Method emphasizes building a thorough support structure for each of an argument's key claims.

The basic format for the Toulmin Method is as follows:

Claim: In this section, you explain your overall thesis on the subject. In other words, you make your main argument.

Data (Grounds): You should use evidence to support the claim. In other words, provide the reader with facts that prove your argument is strong.

Warrant (Bridge): In this section, you explain why or how your data supports the claim. As a result, the underlying assumption that you build your argument on is grounded in reason.

Backing (Foundation): Here, you provide any additional logic or reasoning that may be necessary to support the warrant.

Counterclaim: You should anticipate a counterclaim that negates the main points in your argument. Don't avoid arguments that oppose your own. Instead, become familiar with the opposing perspective. If you respond to counterclaims, you appear unbiased (and, therefore, you earn the respect of your readers). You may even want to include several counterclaims to show that you have thoroughly researched the topic.

Rebuttal: In this section, you incorporate your own evidence that disagrees with the counterclaim. It is essential to include a thorough warrant or bridge to strengthen your essay’s argument. If you present data to your audience without explaining how it supports your thesis, your readers may not make a connection between the two, or they may draw different conclusions.

Example of the Toulmin Method:

Claim: Hybrid cars are an effective strategy to fight pollution.

Data1: Driving a private car is a typical citizen's most air-polluting activity.

Warrant 1: Due to the fact that cars are the largest source of private (as opposed to industrial) air pollution, switching to hybrid cars should have an impact on fighting pollution.

Data 2: Each vehicle produced is going to stay on the road for roughly 12 to 15 years.

Warrant 2: Cars generally have a long lifespan, meaning that the decision to switch to a hybrid car will make a long-term impact on pollution levels.

Data 3: Hybrid cars combine a gasoline engine with a battery-powered electric motor.

Warrant 3: The combination of these technologies produces less pollution.

Counterclaim: Instead of focusing on cars, which still encourages an inefficient culture of driving even as it cuts down on pollution, the nation should focus on building and encouraging the use of mass transit systems.

Rebuttal: While mass transit is an idea that should be encouraged, it is not feasible in many rural and suburban areas, or for people who must commute to work. Thus, hybrid cars are a better solution for much of the nation's population.

Rogerian Method

The Rogerian Method (named for, but not developed by, influential American psychotherapist Carl R. Rogers) is a popular method for controversial issues. This strategy seeks to find a common ground between parties by making the audience understand perspectives that stretch beyond (or even run counter to) the writer’s position. Moreso than other methods, it places an emphasis on reiterating an opponent's argument to his or her satisfaction. The persuasive power of the Rogerian Method lies in its ability to define the terms of the argument in such a way that:

- your position seems like a reasonable compromise.

- you seem compassionate and empathetic.

The basic format of the Rogerian Method is as follows:

Introduction: Introduce the issue to the audience, striving to remain as objective as possible.

Opposing View : Explain the other side’s position in an unbiased way. When you discuss the counterargument without judgement, the opposing side can see how you do not directly dismiss perspectives which conflict with your stance.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): This section discusses how you acknowledge how the other side’s points can be valid under certain circumstances. You identify how and why their perspective makes sense in a specific context, but still present your own argument.

Statement of Your Position: By this point, you have demonstrated that you understand the other side’s viewpoint. In this section, you explain your own stance.

Statement of Contexts : Explore scenarios in which your position has merit. When you explain how your argument is most appropriate for certain contexts, the reader can recognize that you acknowledge the multiple ways to view the complex issue.

Statement of Benefits: You should conclude by explaining to the opposing side why they would benefit from accepting your position. By explaining the advantages of your argument, you close on a positive note without completely dismissing the other side’s perspective.

Example of the Rogerian Method:

Introduction: The issue of whether children should wear school uniforms is subject to some debate.

Opposing View: Some parents think that requiring children to wear uniforms is best.

Statement of Validity (Understanding): Those parents who support uniforms argue that, when all students wear the same uniform, the students can develop a unified sense of school pride and inclusiveness.

Statement of Your Position : Students should not be required to wear school uniforms. Mandatory uniforms would forbid choices that allow students to be creative and express themselves through clothing.

Statement of Contexts: However, even if uniforms might hypothetically promote inclusivity, in most real-life contexts, administrators can use uniform policies to enforce conformity. Students should have the option to explore their identity through clothing without the fear of being ostracized.

Statement of Benefits: Though both sides seek to promote students' best interests, students should not be required to wear school uniforms. By giving students freedom over their choice, students can explore their self-identity by choosing how to present themselves to their peers.

Classical Method

The Classical Method of structuring an argument is another common way to organize your points. Originally devised by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (and then later developed by Roman thinkers like Cicero and Quintilian), classical arguments tend to focus on issues of definition and the careful application of evidence. Thus, the underlying assumption of classical argumentation is that, when all parties understand the issue perfectly, the correct course of action will be clear.

The basic format of the Classical Method is as follows:

Introduction (Exordium): Introduce the issue and explain its significance. You should also establish your credibility and the topic’s legitimacy.

Statement of Background (Narratio): Present vital contextual or historical information to the audience to further their understanding of the issue. By doing so, you provide the reader with a working knowledge about the topic independent of your own stance.

Proposition (Propositio): After you provide the reader with contextual knowledge, you are ready to state your claims which relate to the information you have provided previously. This section outlines your major points for the reader.

Proof (Confirmatio): You should explain your reasons and evidence to the reader. Be sure to thoroughly justify your reasons. In this section, if necessary, you can provide supplementary evidence and subpoints.

Refutation (Refuatio): In this section, you address anticipated counterarguments that disagree with your thesis. Though you acknowledge the other side’s perspective, it is important to prove why your stance is more logical.

Conclusion (Peroratio): You should summarize your main points. The conclusion also caters to the reader’s emotions and values. The use of pathos here makes the reader more inclined to consider your argument.

Example of the Classical Method:

Introduction (Exordium): Millions of workers are paid a set hourly wage nationwide. The federal minimum wage is standardized to protect workers from being paid too little. Research points to many viewpoints on how much to pay these workers. Some families cannot afford to support their households on the current wages provided for performing a minimum wage job .

Statement of Background (Narratio): Currently, millions of American workers struggle to make ends meet on a minimum wage. This puts a strain on workers’ personal and professional lives. Some work multiple jobs to provide for their families.

Proposition (Propositio): The current federal minimum wage should be increased to better accommodate millions of overworked Americans. By raising the minimum wage, workers can spend more time cultivating their livelihoods.

Proof (Confirmatio): According to the United States Department of Labor, 80.4 million Americans work for an hourly wage, but nearly 1.3 million receive wages less than the federal minimum. The pay raise will alleviate the stress of these workers. Their lives would benefit from this raise because it affects multiple areas of their lives.

Refutation (Refuatio): There is some evidence that raising the federal wage might increase the cost of living. However, other evidence contradicts this or suggests that the increase would not be great. Additionally, worries about a cost of living increase must be balanced with the benefits of providing necessary funds to millions of hardworking Americans.

Conclusion (Peroratio): If the federal minimum wage was raised, many workers could alleviate some of their financial burdens. As a result, their emotional wellbeing would improve overall. Though some argue that the cost of living could increase, the benefits outweigh the potential drawbacks.

Writing Nestling

What Is A Warrant In Writing? (Explained+ 4 Types)

In the intricate tapestry of persuasive writing, warrants emerge as the linchpins that bridge the gap between evidence and claim, lending credibility and coherence to arguments.

Simply put, a warrant in writing acts as the logical connection or reasoning that links the evidence presented to the assertion or claim being made. It serves as the underlying justification or principle that allows readers to accept the leap from data to conclusion.

As such, warrants play a pivotal role in crafting convincing arguments, guiding readers through the intricacies of reasoning and persuasion.

However, warrants are not always explicitly stated; they can be implicit, implied through context or inferred from the structure of the argument.

Understanding the nuances of warrants is essential for effective communication and critical thinking, as they underpin the foundation of logical discourse in various fields, from academia to law to everyday rhetoric.

In this exploration, we delve into the multifaceted nature of warrants in writing, dissecting their forms, functions, and applications across diverse contexts to illuminate their significance in shaping our understanding and interpretation of the world around us.

Table of Contents

What Is A Warrant In Writing?

A warrant in writing is a legal document that authorizes or empowers a person or entity to perform certain actions or make specific decisions.

Identification of Parties

It typically involves at least two parties: the issuer of the warrant and the recipient or holder of the warrant.

The warrant is issued by an authorized party, such as a court, government agency, or corporate entity.

Authorization

The warrant confers authority upon the holder to carry out actions specified within the document.

Warrants are commonly used in various contexts, including law enforcement, finance, and business transactions, to grant permission, execute trades, or conduct searches.

Scope and Limitations

The warrant outlines the scope of authority granted to the holder and may include limitations or conditions under which it can be exercised.

Warrants may have an expiration date or remain valid until a specific event occurs.

Legal Implications

Violating the terms of a warrant or exceeding its authority can result in legal consequences for the holder.

Enforcement

In cases of non-compliance or misuse, the issuer of the warrant may take legal action to enforce its terms or revoke the warrant.

Documentation

Warrants are typically documented in writing to provide clarity and enforceability, often in the form of a written order or certificate.

Review and Renewal

Depending on the circumstances, warrants may need periodic review or renewal to remain valid.

Record-Keeping

Proper documentation and record-keeping of warrants are essential for accountability and legal compliance.

The Conceptual Framework of Warrants

In the vast tapestry of persuasive writing, the Conceptual Framework of Warrants stands as the luminary guiding star, illuminating the intricate pathways between evidence and conclusion.

Like the unseen architect of a grand cathedral, warrants provide the blueprint upon which compelling arguments are constructed.

They are the invisible threads weaving together logic, credibility, and persuasion, transcending mere assertion to forge the steel of conviction.

Rooted in the fertile soil of Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation, warrants burgeon forth as the fertile ground for the seeds of rational discourse to flourish.

Here, within this conceptual realm, ideas transcend the mundane and soar into the realm of the profound, transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary with each stroke of the writer’s pen.

Origins and Evolution of Warrants

The origins of warrants trace back through the annals of human discourse, echoing the ancient debates of philosophers and orators in the bustling agora of Athens and the hallowed halls of Rome.

Evolving alongside the evolution of argumentation itself, warrants have weathered the tides of intellectual history, adapting to the shifting currents of thought and belief.

From Aristotle’s enthymemes to the dialectics of the Enlightenment, warrants have been the bedrock upon which civilizations have built their edifices of knowledge and persuasion.

Over time, they have metamorphosed from simple syllogisms to complex frameworks of reasoning, as thinkers from diverse traditions have enriched and refined their conceptual underpinnings.

Today, in the digital age, warrants continue to evolve, shaped by the crucible of modernity and the transformative power of technology, yet still retaining the timeless essence of their ancient lineage.

Types of Warrants

Embark on a journey through the labyrinth of persuasion, where the Types of Warrants stand as formidable guardians, each holding the key to unlock the mysteries of compelling argumentation.

From the explicit declarations that boldly proclaim their presence to the subtle whispers of implicit assumptions, these warrants weave a tapestry of logic and persuasion that captivates the mind and ignites the soul.

Substantive warrants stand as pillars of strength, grounded in empirical evidence and rigorous analysis, while structural warrants dance gracefully between the lines, guiding the reader through the intricate architecture of thought.

Within this realm, the dichotomy of deduction and induction intertwines, as analogical reasoning draws unexpected connections and comparison illuminates the path forward.

As you navigate the rich tapestry of types, let each warrant be a beacon of inspiration, guiding you toward the pinnacle of persuasive mastery.

Explicit Warrants

Explicit warrants, like beacons in the fog of argumentation, shine forth with unyielding clarity, leaving no room for ambiguity or interpretation.

These warrants boldly declare their presence, standing as veritable signposts that guide the reader along the path of reasoning.

Through explicit warrants, writers lay bare the foundation of their arguments, articulating the logical connections between evidence and claim with unwavering precision.

Whether stated explicitly or implied through meticulous wording, these warrants serve as the linchpin of persuasive discourse, offering a solid foothold upon which readers can anchor their understanding.

In a world inundated with information and competing narratives, explicit warrants cut through the noise, commanding attention and demanding intellectual engagement.

They are the cornerstone of effective communication, empowering writers to build compelling cases that resonate with clarity and conviction.

Implicit Warrants

Implicit warrants, shrouded in the subtleties of language and inference, are the enigmatic sorcerers of persuasive writing, casting their spell upon the minds of readers without overt proclamation.

Unlike their explicit counterparts, implicit warrants operate in the realm of suggestion, beckoning the audience to discern the underlying assumptions and connections woven into the fabric of the text.

Like whispers in the wind, these warrants insinuate themselves into the subconscious, nudging readers towards particular interpretations and conclusions without ever fully revealing themselves.

Through the artful use of implication, innuendo, and context, implicit warrants invite readers on a journey of discovery, challenging them to unravel the intricacies of the argument and uncover the hidden truths concealed within.

In the dance between explicit and implicit warrants, it is often these elusive whispers that wield the greatest influence, shaping perceptions and swaying opinions with a deft touch that belies their ephemeral nature.

Substantive Warrants

Substantive warrants, sturdy pillars of logical reasoning, anchor the edifice of persuasive discourse with their robust foundation of empirical evidence and sound analysis.

Unlike their ethereal counterparts, substantive warrants stand firm in the face of scrutiny, fortified by the weight of data, research, and expert testimony.

These warrants serve as the bedrock upon which persuasive arguments are built, providing the necessary support to bridge the gap between evidence and claim.

Through meticulous attention to detail and rigorous examination of facts, substantive warrants lend credibility and authority to the writer’s assertions, imbuing them with a sense of trustworthiness and reliability.

In a world where misinformation and conjecture often masquerade as truth, substantive warrants stand as beacons of clarity and rationality, guiding readers towards informed conclusions and enlightened perspectives.

Structural Warrants

Structural warrants, the silent architects of persuasive discourse, intricately design the framework upon which arguments are constructed, directing the flow of logic and guiding readers through the labyrinth of reasoning. These warrants operate beyond the realm of explicit statement, weaving their influence subtly within the structure and organization of the text.

Through strategic placement of evidence, arrangement of ideas, and coherence of presentation, structural warrants shape the narrative trajectory, compelling readers to follow a predetermined path towards the desired conclusion.

Like the unseen hand of a master craftsman, they orchestrate the symphony of argumentation, ensuring that each element harmonizes seamlessly to produce a compelling and persuasive whole.

Within this intricate web of structure and form, structural warrants wield immense power, influencing not only what is said but also how it is perceived, ultimately shaping the reader’s understanding and interpretation of the argument.

Functions of Warrants in Writing

In the grand tapestry of persuasive writing, warrants serve as the clandestine guardians of coherence and conviction, wielding their influence with a subtle yet undeniable authority.

Like the masterful conductor of an orchestra, warrants harmonize the cacophony of evidence and claims into a symphony of logic, guiding readers on a mesmerizing journey of comprehension and persuasion.

Beyond mere connectivity, these warrants infuse arguments with the lifeblood of credibility and trust, elevating them from the mundane to the extraordinary.

They are the secret alchemists of rhetoric, transmuting raw data and abstract ideas into the golden currency of persuasion, compelling readers to surrender their doubts and embrace the truths laid bare before them.

In the hands of skilled writers, warrants transcend the boundaries of language and logic, transcending mere words to evoke profound insights and stir the deepest emotions.

Warrant Development Strategies

Navigating the labyrinth of persuasion demands not only clarity of thought but also mastery of the elusive art of warrant development.

Like a seasoned alchemist, writers wield an array of strategies to distill the essence of compelling reasoning from the cacophony of information.

From the alchemy of evidential support, where empirical data and expert testimony are transmuted into the gold of persuasive argumentation, to the intricate dance of reasoning techniques, where deduction, induction, and analogy intertwine to forge the steel of logical coherence, every strategy is a brushstroke on the canvas of persuasion.

Yet, the true alchemy lies in the ability to navigate the treacherous waters of contextual considerations, where warrants must be tailored to the audience’s disposition and the argument’s purpose, anticipating objections and weaving counterarguments into the very fabric of the discourse.

In this crucible of creativity and intellect, writers emerge as sorcerers of persuasion, wielding warrants as their potent spells to captivate minds and stir souls.

Examples and Case Studies

Embark on a captivating journey through the corridors of persuasion, where examples and case studies illuminate the path to mastery.

Like ancient artifacts unearthed from the depths of history, these narratives beckon readers to unravel their mysteries and glean wisdom from their depths.

From the riveting dramas of legal arguments and case briefs, where the clash of justice and injustice echoes through the halls of the courtroom, to the scholarly tapestries of academic essays and research papers, where the pursuit of knowledge leads seekers to the farthest reaches of human understanding, each example is a window into a world of intellectual discovery.

Yet, it is within the labyrinth of advertising campaigns and marketing copy that the true artistry of persuasion reveals itself, as writers wield the alchemy of language and imagery to weave spells of desire and captivate the hearts of consumers.

Through the lens of examples and case studies, readers are invited to traverse the boundaries of imagination and reality, where every turn offers new insights and every revelation sparks inspiration.

Challenges and Pitfalls in Warrant Usage

Embarking on the journey of persuasion, one must navigate the treacherous terrain of challenges and pitfalls that lurk beneath the surface.

Like hidden traps in a labyrinth, these obstacles threaten to ensnare even the most skilled rhetoricians. From the seductive allure of fallacies that masquerade as truth to the siren song of oversimplification that lulls the mind into complacency, the pitfalls of warrant usage are as varied as they are perilous.

Yet, perhaps the greatest danger lies in the murky waters of ethical ambiguity, where writers must tread carefully to avoid the pitfalls of manipulative practices that undermine the integrity of their arguments.

In this crucible of contention, where the clash of ideas reverberates through the corridors of discourse, writers must remain vigilant, guarding against the siren call of intellectual laziness and the temptation to sacrifice honesty on the altar of persuasion.

Only by confronting these challenges head-on, with courage and integrity, can writers hope to emerge unscathed, their arguments fortified by the crucible of adversity and their convictions tempered by the fires of ethical scrutiny.

Advanced Applications of Warrants

Step into the realm of advanced applications of warrants, where the boundaries of persuasion are pushed to their limits and innovation reigns supreme.

Here, in this crucible of intellectual exploration, warrants transcend the confines of traditional discourse, morphing into potent tools wielded by pioneers of communication.

From the dazzling world of multimodal communication, where words intertwine with images and sound to create immersive experiences that captivate the senses, to the cross-disciplinary frontiers where warrants bridge the chasm between disparate fields, ushering in a new era of collaboration and discovery.

In the digital age, where the boundaries between reality and virtuality blur, warrants find new expression in interactive and digital platforms, empowering users to engage with information in ways never before imagined.

Yet, amidst this whirlwind of innovation, ethical considerations loom large, challenging writers to wield warrants with integrity and responsibility, lest they become entangled in the web of manipulation and deceit.

In this brave new world of communication, where the possibilities are as limitless as the imagination, warrants stand as beacons of guidance, guiding seekers of truth through the labyrinth of information towards the light of understanding.

Future Directions and Innovations

As we stand on the precipice of a new dawn in communication, the future of warrants gleams with the promise of innovation and discovery.

Like pioneers charting unexplored territories, writers are poised to harness the transformative power of technology and insight to propel warrants into uncharted realms of possibility.

In the ever-expanding universe of computational approaches, warrants emerge as the focal point of cutting-edge algorithms and machine learning techniques, enabling the analysis of vast troves of data with unprecedented speed and accuracy.

Moreover, the integration of artificial intelligence promises to revolutionize warrant generation, as algorithms evolve to anticipate and adapt to the nuances of human thought and emotion, forging connections that transcend the limitations of mere logic.

Yet, amidst this whirlwind of progress, ethical considerations loom large, challenging writers to navigate the delicate balance between innovation and responsibility, lest they become ensnared in the web of manipulation and deceit.

In this brave new world of communication, where the boundaries between reality and virtuality blur, warrants stand as beacons of guidance, guiding seekers of truth through the labyrinth of information towards the light of understanding.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about What Is A Warrant In Writing?

What exactly is a warrant in writing.

A warrant in writing serves as the logical bridge between the evidence provided and the claim being made in an argument. It provides the reasoning or justification that connects the two, essentially explaining why the evidence supports the claim.

How does a warrant differ from evidence and claims?

While evidence consists of factual information or data supporting an argument, and claims are the assertions or conclusions being made, warrants provide the reasoning or logical connection between the two. Think of evidence as the bricks, claims as the structure, and warrants as the mortar holding them together.

Are warrants always explicitly stated in writing?

No, warrants can be either explicit or implicit. Explicit warrants are directly stated within the text, while implicit warrants are implied through the context or structure of the argument. Identifying implicit warrants often requires critical thinking and analysis of the writer’s intent.

What are some common examples of warrants in writing?

Examples of warrants include appeals to authority, logical reasoning, empirical evidence, analogical reasoning, and cause-and-effect relationships. For instance, in a persuasive essay about climate change, a warrant might be the assumption that scientific consensus is a reliable indicator of truth.

How do warrants contribute to the overall effectiveness of writing?

Warrants play a crucial role in crafting persuasive and coherent arguments. They provide the necessary reasoning and justification to convince readers of the validity of the claims being made, thereby enhancing the credibility and persuasiveness of the writing.

Can warrants be misused or misrepresented in writing?

Yes, warrants can be misused in various ways, such as by employing faulty logic, cherry-picking evidence, or making unsupported assumptions. Misrepresenting warrants can undermine the integrity of the argument and lead to misleading or unconvincing conclusions.

How can I strengthen the warrants in my writing?

To strengthen warrants, it’s essential to ensure they are supported by relevant and credible evidence, employ sound reasoning and logic, consider alternative perspectives or counterarguments, and maintain clarity and coherence in the overall argument structure.

Are warrants only used in formal writing, or do they apply to everyday communication as well?

Warrants are fundamental elements of effective communication and critical thinking, applicable to various forms of writing, including academic essays, legal arguments, persuasive speeches, and everyday discourse. Understanding warrants can help improve clarity, coherence, and persuasiveness in both formal and informal writing contexts.

In conclusion, warrants in writing serve as the vital nexus between evidence and claim, providing the essential reasoning and justification that underpin persuasive arguments.

Whether explicit or implicit, warrants play a pivotal role in guiding readers through the complexities of logical discourse, enhancing the credibility and persuasiveness of the overall message.

By understanding the nuances of warrants and their applications across diverse contexts, writers can wield these powerful tools to craft compelling narratives, foster critical thinking, and ultimately, shape our understanding of the world.

As we navigate the intricacies of communication, let us remember that warrants are not merely components of writing but the very essence of reasoned discourse, illuminating the path to clarity, coherence, and persuasion.

Related Posts:

- How To Write An Editorial (12 Important Steps To Follow)

- How Can You Show Transparency In Your Writing (12 Best Ways)

- How To Improve Literacy Writing Skills (14 Best Tips)

What Is A Universal Statement In Writing? (Explained)

- How To Improve Dissertation Writing (14 Important Tips)

- How To Describe A Smart Person (12 Best Ways You…

Similar Posts

Can I Blog About Random Things? (12 Important Tips)

Embarking on the digital odyssey of blogging opens up a world of possibilities, and a common question that often arises is, “Can I blog about random things?” The short answer? Absolutely. In fact, the beauty of blogging lies in its inherent versatility, offering creators the freedom to explore an eclectic array of topics. Imagine your…

How Do You Write A Dream Blogging? (12 Best Tips)

Embarking on the enchanting odyssey of dream blogging is a venture into the realm where the subconscious meets the digital cosmos. Writing about dreams transcends mere storytelling; it’s an exploration of the ethereal landscapes within our minds, a journey that transforms the intangible threads of nocturnal adventures into a captivating tapestry of words. In this…

Is Content Writing A Stressful Job? (Yes, 12 Big Stressors)

In the ever-evolving digital landscape, where words wield the power to shape perceptions and drive engagement, content writing stands at the forefront of communication. However, behind the artful prose and strategic narratives, a question looms: Is content writing a stressful job? This inquiry delves into the dynamic interplay between creativity and pressure, exploring the multifaceted…

What Is Freelance Writing? (Definition,07 Types)

Freelance writing is the dynamic intersection of passion, creativity, and entrepreneurship, where individuals wield the power of words to craft compelling narratives, inform, entertain, and inspire. In its essence, freelance writing represents the embodiment of freedom and autonomy, offering writers the flexibility to pursue their craft on their own terms, unfettered by the constraints of…

How To Describe Clouds In Writing (10 Important Tips)

Embarking on the journey of describing clouds in writing is akin to stepping into a celestial realm where language becomes the brush and the sky transforms into an ever-shifting canvas of wonders. In this exploration, words transcend mere descriptors; they become the architects of atmospheric landscapes, the weavers of emotional tapestries, and the conduits for…

In the realm of writing, a universal statement stands as a literary lodestar, guiding authors through the expansive seas of human expression. It encapsulates ideas or themes that possess an enduring relevance, transcending the constraints of time, culture, and individual perspectives. Akin to a literary North Star, a universal statement beckons readers from diverse backgrounds,…

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.3.4: Warrant – How Do Your Reasons Support Your Claim? Five Essential Parts of an Argument

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 74458

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Five Essential Parts of an Argument

Read article on the parts of an argument, especially warrants. How do warrants differ from reasons and evidence?

Why Does Little Red Schoolhouse (LRS) View Writing as Argument?

When we disagree about an issue, care deeply about an outcome, or try to convince others of the validity of our approach, we often resort to argument. Argument as it is depicted on television and experienced in times of stress or conflict carries with it many negative connotations of anger, high emotion, and even irrationality. But each of us also makes arguments every day, and in settings that help us become more rational, better informed, and more clearly understood.

Arguments help us to gather information from our own experience and that of others, to make judgments based on evidence, and to marshal information toward sound conclusions. Argument is appropriate when we seek understanding or agreement, when we want to solve a problem or answer a question, and when we want others to act or think in ways we deem beneficial, suitable, or necessary. Argument also comes in handy when we seek to convince, persuade, or produce change in our audience, and when circumstances require trust, respect, belief in our evidence or agreement with our reasoning.

Argument is everywhere – on television and radio, in politics and publications, and also in our day-to-day decisions about what to have for dinner, when to schedule the next meeting, and who should walk the family dog. As Colomb and Williams point out, the common notion that argument must be combative is built into our very language: opposing sides attack, defend, hold off, triumph, struggle, crush objections and slaughter competitors. On the other hand, in order to use argument as productive and collaborative communication, we must certainly find a way to transcend the vocabulary of argument-as-war. We must negotiate the audience's needs along with the speaker's agenda.

Argument is also about conversation. Although sometimes we forget, the best arguments are a forum for:

- Obtaining and expressing information;

- Airing and sharing assumptions and reasons;

- Establishing common ground;

- Coming to mutual agreement.

Productive argumentation starts with a problem. It makes us realize why we have an interest in seeing that problem solved. It also claims a solution, convincing its audience of the validity of that solution with evidence and reasons that it will accept.

Writing and Argument

The Little Red Schoolhouse (LRS) focus on argumentation raises writers' and readers' awareness of:

- The importance of audience;

- The intersecting languages of information and persuasion; and

- The reading process through which we share the tasks of critical thinking and decision-making.

Argument structure also helps writers to avoid:

- The formulaic "five paragraph essay" that is often assigned in high school ("Scientific progress is good. Here are several reasons why scientific progress is good. In conclusion, scientific progress is good.");

- The default structure of chronological order (First I set up the lab, then I opened my notebook, then performed the first step in my experiment…);

- Simple summary with no so what; and

- Binary structures where two issues or ideas are described without connection to each other.

Preparing Your Argument

To prepare to make an effective argument you must first:

- Translate your topic into a problem statement;

- Frame a situation that is debatable or contestable;

- Formulate a question about which reasonable people might disagree; and

- Find a claim your analysis has led you to assert.

Now you can begin to imagine what it will take to convince your audience. What evidence, methods, or models do they expect? What conventions must you follow to win approval?

Sketch Your Approach

- What do you want to show?

- Why should readers agree?

- Based on what evidence?

- What are some possible alternatives or objections?

- What conclusion will you offer, and why should your readers accept it as valuable?

The Five Parts of Argument

The questions that lead to your topic, broadly conceived, also steer you toward what The Craft of Argument formalizes in the five parts of argument.

- Acknowledgment and Response.

These Correspond to the Williams' and Colomb's Five Questions of Argument:

- What are you claiming?

- What reasons do you have for believing your claim?

- What evidence do you base those reasons on?

- What principle connects or makes your reasons relevant to your claims?

- What about such-and-such potential disagreement/difficulty?

Constructing Claims

We learn that, at bottom, an argument is just a claim and its support:

Reason therefore Claim

Claim because of Reason.

Your claim is your main point. It should either be clearly conceptual (seeking to change how we think) or clearly pragmatic (seeking to change how we act). Claims should, by definition, require good reasons. Audiences should be able to disagree with your claim and, by extension, to be convinced and converted by your evidence.

More about Claims

- Make sure your readers can recognize why your claim is significant.

- Ensure that your claim is clear and concise. Readers should be able to tell what is at stake and what principles you intend to use to argue your point.

- Confirm that the claim accurately describes the main tenets of the argument to follow.

- Moderate your claim with appropriate qualifiers like "many", "most", "often", in place of "all", "always", etc.

Evaluating Good Claims

- Your solution is possible.

- Your solution is ethical (moral, legal, fair, etc.).

- Your solution is prudent – it takes into consideration both the problem you seek to resolve and the possible ramifications of your proposal.

Reasons and Evidence

Most arguers know from experience that reasons and evidence help to convince audiences. In the simplest terms, reasons answer the question: "Why are you making that claim?" Evidence offers tangible support for reasons.

When stating reasons, always be aware of your audience. You will need to choose the reasons that support your evidence that are also the most likely to convince your specific readers or listeners. Knowing the general values and priorities of your readers will help you to determine what they will count as compelling reasons.

Knowing what kind of arguments and evidence they will expect from you will guide you in choosing reasons that meet those expectations.

Tailor your appeal to the specific needs and acknowledged concerns of your reading community, because arguments are always audience specific.

Evidence should be reliable and based upon authoritative and trustworthy research and sources. It should be appropriately cited, and ample enough to convince. Evidence should also be designed to appeal to your target audience's values and priorities.

When Arguing through Evidence

- Present evidence from general to specific.

- Build on what readers know.

- Do not rehearse your own work process; instead, support your conclusions.

- Use diagrams, graphs, and other visuals.

- Keep support appropriate and simple.

- Make sure data is authoritative/expert.

- Help the audience to know what is important.

The words reason and evidence are much more familiar to most students of written and oral argument than the term warrant. But reasons and evidence are most powerful when they are utilized within the structure of argument we have been discussing.

To be convincing, the reasons and evidence you present in support of your claim need to be connected through warrants. Warrants express a general belief or principle in a way that influences or explains our judgments in specific cases.

Take, for example, the old saying: "Measure twice, cut once".

Expressing as it does a general belief or principle – that when you take the time to do a thing properly, you don't make mistakes – the saying provides a viable warrant for an argument like:

"It is never a good idea to hurry a task. [Reason] [Connected by the beliefs and assumptions expressed by the warrant to the supporting evidence that] Careless mistakes take longer to fix than it would to do things right the first time." [Evidence]

Warrants express justifying principles, shared beliefs, or general assumptions. They are the spoken or unspoken logic that connects your reasons to your evidence. Warrants take many forms, but Williams and Colomb emphasize that they always have or imply two parts:

- One articulating a general belief or circumstance.

- One stating a conclusion we can infer from applying that circumstance to a specific situation.

Warrants often take the form: Whenever X, then Y. For example, take the commonly held belief expressed by the old saying "When it rains, it pours". The same sentiment and set of assumptions could be described by the general truism "If one thing goes wrong, everything goes wrong". Whether implied or explicit, and whether it takes the form of a general observation or a cultural belief, a warrant states a broader principle that can be applied in a particular case to justify the thinking behind an argument.

More on Clear Warrants

Warrants connect your reasons to your claim in logical ways. Whether a warrant is assumed or implied, it is still crucial that the audience be able to recognize your warrant and be able to determine that they agree with or accept your warrant.

Questions for Determining Good Warrants

- Do readers know the warrant already?

- Will all readers think it is true?

- Will they see its connection to this circumstance or situation?

- If they think it is both valid and appropriate, will they think it applies to their family, corporation, or community?

Warranting: A Specific Case

Consider a case when an audience might not accept your argument unless it first accepts your warrant. Take, for example, the following discussion between a mother and her child.

Child (to mother): "I need new shoes."

Mother: "But why, what are your reasons?"

Child: "Because all the other kids have them." X

Child: "Because red is 'in' this season and my shoes are blue." X

Mother: "Sorry, but I don't accept your argument that you need new shoes."

Above all, warrants require common ground. In the example above, the success of the child's argument depends upon his mother's sharing the values and assumptions upon which the argument for new shoes is based.

Productive argument will require that the child find, and address, some common belief or assumption about what constitutes "need". While his mother might not be influenced by peer pressure or style trends, she probably does share a set of values that would ultimately lead to agreement (Common Ground).

Consider a situation in which the child's previous reasons had not convinced his mother to accept his argument, and we can see how compelling reasons and evidence can be developed alongside shared warrants.

Child: "I need new shoes because these ones have holes in them and it's the rainy season." √

Mother: "Well why didn't you say so?! I agree that you shouldn't be walking around with wet feet!"

We are most likely to accept an argument when we share a warrant. In this case, it is unstated, but implied:

Warrant = When shoes no longer protect the feet from stones and weather, it is time to buy new ones.

There is another way to look at warrants that don't necessarily fit a certain mold. If you believe in a general principle stated about general circumstances (for example, "People who fall asleep at work probably aren't getting enough sleep at home".), then you are likely to link a specific instance (of nodding off at your computer) with a specific conclusion (that you haven't gotten adequate rest). Warrants here can be defined as general truths that lead us to accepted conclusions.

Acknowledgment and Response

Acknowledgment and response can be included in your argument in order to:

- Produce trust;

- Mediate or moderate objections;

- Limit the scope of your claim;

- Demonstrate experience or immersion in a wider field or discipline.

Brainstorm useful concessions to potential dissenters by thinking about the difficulties or questions your argument is likely to produce. Within your argument, acknowledgements and responses often begin with: To be sure, admittedly, some have claimed, etc.

Concessions allow the writer to predict problems that might weaken an argument and respond with rebuttals and reassessments. Acknowledgement and response frequently employs terms like but, however, on the other hand, etc.

Using the Five Parts of Argument

After you have sketched out your full argument, and even after you have drafted the entire piece of writing, you should revisit your claim. Ask yourself: Does the claim still introduce and frame the discussion that follows? Are there elements of the claim that need to be revised? Built upon? Eliminated? Explained?

- Is your claim clear and concise?

- Is it contestable?

- Is there good evidence for your solution?

- Will your audience agree?

Evaluate and Revise Reasons

Consider the specific needs and perspectives of your audience and select reasons that will connect to their priorities and motivations. Make sure that you provide ample reasons for each claim or subclaim you assert. Order your reasons in a way that is logical and compelling: Depending on your argument, you may want to lead with your best reason or save your strongest reason for last. Finally, ask yourself whether any essential evidence is missing from your discussion of the problem.

- Do your reasons make a strong case for the validity of your claim?

- Can you imagine other reasons that would appeal more strongly to your audience?

Assess and Improve Evidence

If there are authorities to appeal to, experts who agree, or compelling facts that support your argument, make sure you have included them in full. Whether you are speaking from experience, research, or reading, make sure to situate yourself firmly in your field. Create confidence in your authority and establish the trustworthiness of your account.

- Have you consulted reputable sources?

- Have you conducted your research and formatted your findings according to accepted standards?

- What does your audience need to know to appreciate the solution you propose?

- What makes it easy or difficult to accept?

- What further support might you offer?

Scrutinize Your Warrants

If you can't articulate the connection between what you claim and why you believe the audience should accept your assertion, your readers probably can't either! Good warrants often take the form of assumptions shared by individuals, communities or organizations. They stem from a shared culture, experience, or perspective. If understanding your claim means sharing a particular set of beliefs or establishing common ground with your reader, make sure your argument takes time to do so.

- Can your audience easily connect your claim to your reasons?

- Are your warrants shared? Explicit? Implied?

- What unspoken agreements do your conclusions depend upon?

Concede and Explain

Gracefully acknowledge potential objections when it can produce trust and reinforce the fairness and authority of your perspective. Try to anticipate the difficulties that different types of readers might have with your evidence or reasoning

- Where are my readers most likely to object or feel unsettled?

- How can I concede potential problems while still advancing the authority of my claim?

Assessing and Revising Your Argument

By way of conclusion, we can revisit the issue of method. Little Red Schoolhouse (LRS) encourages thinking about the parts of argument in order to produce logic that is

- Easy to understand, and

- Easy to acknowledge or accept.

Argument structures comprehension by giving readers a framework within which to understand a given discussion. Argument supplies criteria for judgment, and connects reasons with claims through implicit or explicit warrants. Sometimes, crafting a good argument is as simple as asking yourself three basic questions:

- What do you want to say?

- Why should readers care?

When you set about answering these questions using the five parts of argument, you will hone introductions and thesis statements to make clear and precise claims, make relevant costs and benefits explicit, and connect reasons and evidence through shared and compelling warrants.

Examples taken or adapted from:

- Williams, J. (2005). Style: Ten Lessons in Clarity and Grace. (8th ed.). New York: Pearson.

- Williams, J., Colomb, G. (2003). The Craft of Argument. (Concise ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.

- Publish Your Course

- US EN US English

- Partnerships

- Link to Educator.com

- Study Guide

- Terms of Service

Home » English » AP English Language & Composition » Rhetoric Crash Course: Warrants

Rebekah Hendershot

Rhetoric Crash Course: Warrants

Table of contents, ap english language & composition rhetoric crash course: warrants.

Section 4: Rhetoric: Lecture 3 | 10:29 min

In the lesson, our professor Rebekah Hendershot goes through an introduction on a rhetoric crash course of warrants. She starts by reviewing the three elements of argument and then explains what a warrant is, the types of warrants and evaluation of warrants.

Share this knowledge with your friends!

Copy & Paste this embed code into your website’s HTML

- Show resize button - Allow users to view the embedded video in full-size.

Study Guides

Download lecture slides, related books & services.

Lecture Slides are screen-captured images of important points in the lecture. Students can download and print out these lecture slide images to do practice problems as well as take notes while watching the lecture.

Download All Slides

- Lesson Overview 0:11

- The Three Elements of Argument 0:38

- An Example 1:17

- What is a Warrant? 1:53

- May Not Be Stated At All in Your Essay

- Types of Warrants 3:14

- Authoritative Warrants

- Substantive Warrants

- Motivational Warrants

- Evaluation of Warrants 5:32

- Ask These Questions to Evaluate Authoritative Warrants

- Ask These Questions to Evaluate Substantive Warrants

- Ask These Questions to Evaluate Motivational Warrants

AP English Language & Composition

Related books.

Start Today!

- System Requirements

- Brand Logos

- © 2023 Educator, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

- Course Index

Please sign in to participate in this lecture discussion.

- Available 24/7. Unlimited Access to Our Entire Library.

Over 100+ comprehensive high school, college, and university courses taught by passionate educators.

Searchable Lessons

All lessons are segmented into easily searchable and digestible parts. This is to save you time.

Get Answers & Community Support

Ask lesson questions and our educators will answer it.

Downloadable Lecture Notes

Save time by downloading readily available lectures notes. Download, print, and study with them!

Study Guides, Worksheets and Extra Example Lessons

Practice makes perfect!

Start Learning Now

Our free lessons will get you started ( Adobe Flash ® required). Get immediate access to our entire library.

Membership Overview

- Search and jump to exactly what you want to learn.

- *Ask questions and get answers from the community and our teachers!

- Practice questions with step-by-step solutions.

- Download lecture slides for taking notes.

- Track your course viewing progress.

- Accessible anytime, anywhere with our Android and iOS apps.

Warrants in the Toulmin Model of Argument

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In the Toulmin model of argument , a warrant is a general rule indicating the relevance of a claim . A warrant may be explicit or implicit, but in either case, says David Hitchcock, a warrant is not the same as a premise . "Toulmin's grounds are premises in the traditional sense, propositions from which the claim is presented as following, but no other component of Toulmin's scheme is a premise."

Hitchcock goes on to describe a warrant as "an inference -licensing rule": "The claim is not presented as following from the warrant; rather it is presented as following from the grounds in accordance with the warrant"

Examples and Observations

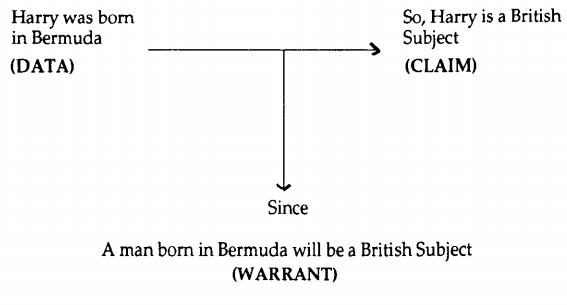

"[T]he Toulmin warrant usually consists of a specific span of text which relates directly to the argument being made. To use a well-worn example, the datum 'Harry was born in Bermuda' supports the claim 'Harry is a British subject' via the warrant 'Persons born in Bermuda are British subjects.'"

"The connection between the data and the conclusion is created by something called a 'warrant.' One of the important points made by Toulmin is that the warrant is a kind of inference rule and in particular not a statement of facts."

"In enthymemes , warrants are often unstated but recoverable. In 'alcoholic beverages should be outlawed in the U.S. because they cause death and disease each year,' the first clause is the conclusion, and the second the data. The unstated warrant is fairly phrased as 'In the U.S. we agree that products causing death and disease should be made illegal.' Sometimes leaving the warrant unstated makes a weak argument seem stronger; recovering the warrant to examine its other implications is helpful in argument criticism. The warrant above would also justify outlawing tobacco, firearms, and automobiles."

- Philippe Besnard et al., Computational Models of Argument . IOS Press, 2008

- Jaap C. Hage, Reasoning With Rules: An Essay on Legal Reasoning . Springer, 1997

- Richard Fulkerson, "Warrant." Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition: Communication from Ancient Times to the Information Age , ed. by Teresa Enos. Routledge, 1996/2010

- What Is the Toulmin Model of Argument?

- Backing (argument)

- Data Definition and Examples in Argument

- Definition and Examples of Conclusions in Arguments

- What Is an Argument?

- Propositions in Debate Definition and Examples

- Argument (Rhetoric and Composition)

- Inference in Arguments

- Premise Definition and Examples in Arguments

- Definition and Examples of Sorites in Rhetoric

- False Dilemma Fallacy

- Fallacies of Relevance: Appeal to Authority

- Bounty Land Warrants

- Definition and Examples of Syllogisms

- What Is Deductive Reasoning?

The Enlightened Mindset

Exploring the World of Knowledge and Understanding

Welcome to the world's first fully AI generated website!