Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NATURE INDEX

- 29 November 2023

Why is China’s high-quality research footprint becoming more introverted?

- Brian Owens 0

Brian Owens is a freelance writer in New Brunswick, Canada.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic are among the factors that have altered China’s patterns of international research collaboration. Credit: Greg Baker/AFP via Getty

When China overtook the United States in the Nature Index for contributions to natural-sciences research articles last year, it marked a watershed moment for the database and for Chinese science. Since the index was launched in 2014, China’s ‘Share’ — a Nature Index metric that takes into account the percentage of authors from a particular location on each paper — has been rising. In 2022, for the first time, China led the world, with a Share of 19,373, an increase of more than 21% from the previous year, well ahead of the US Share of 17,610.

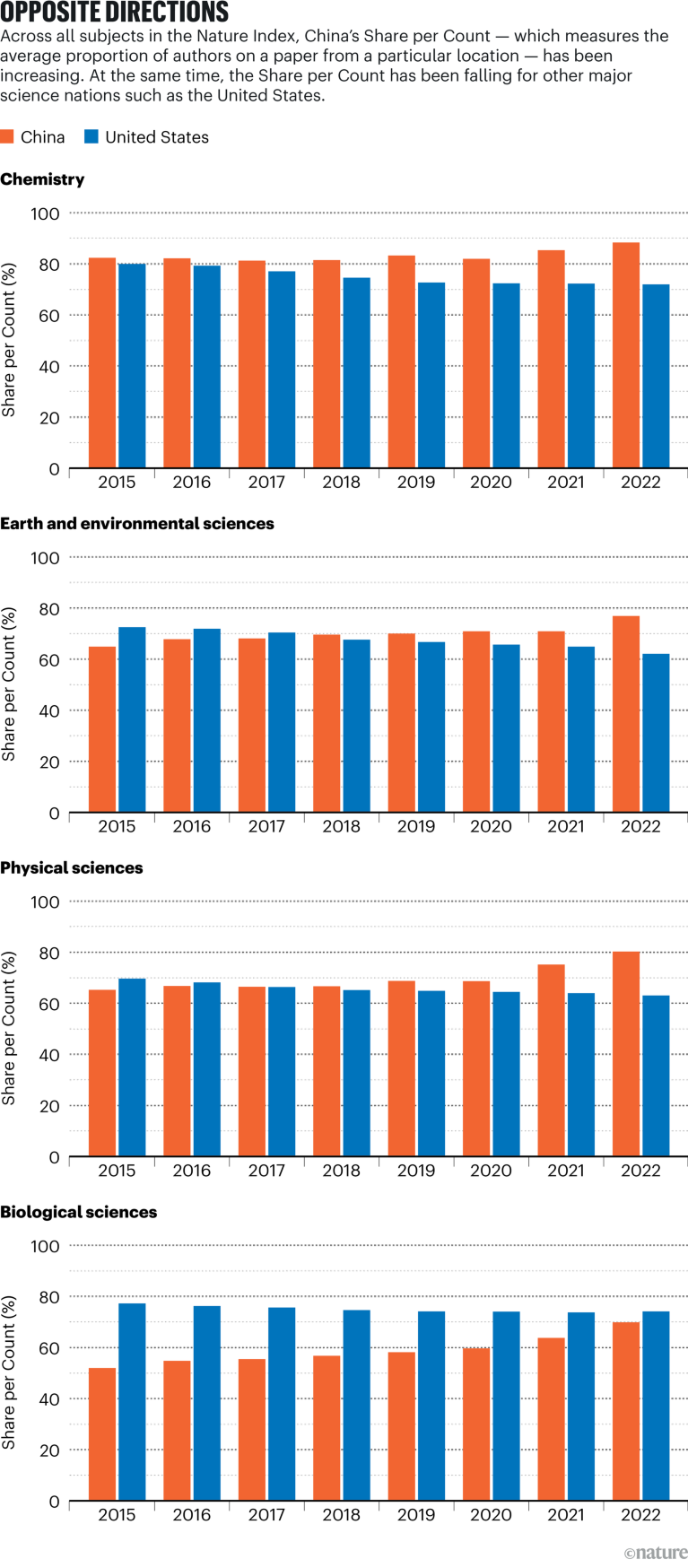

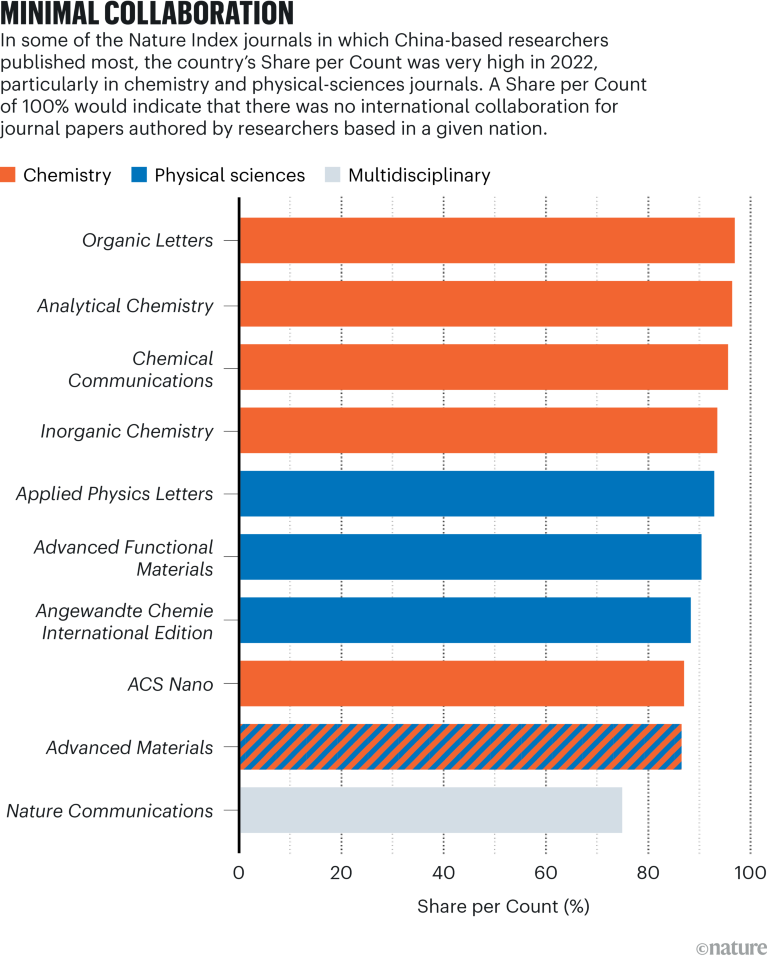

Digging into the data, however, confirms another stark trend in global science. When China’s Share is divided by its ‘Count’ — a Nature Index metric that counts every article that has at least one author from a certain country — it becomes clear that, although the country is contributing more to high-quality research than ever before, much less of that research is being conducted with collaborators from other countries. In 2022, China’s Share/Count ratio reached 82% (a ratio of 100% would indicate no international collaboration at all). This number has been rising steadily for several years: in 2015, China’s ratio was 72%, for instance. At the same time, the ratio for most other major science nations has been falling. For example, the US ratio was 75% in 2015 and 70% in 2022, and for Germany, the ratio fell from 56% to 50% over the same period . In some scientific journals and fields, the trend is even more pronounced (see ‘Minimal collaboration’ and ‘Opposite directions’). China’s Share/Count ratio in the journal Analytical Chemistry , for example, was 96% in 2022.

Pandemic hangover

China’s decline in international collaboration in journals tracked by the Nature Index has been under way for several years, although it was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The trend began prior to the pandemic, but you can’t dismiss COVID-19 as having an impact on anything and everything,” says Denis Simon, former executive vice-chancellor of Duke Kunshan University in Suzhou, China.

Global science is splintering into two — and this is becoming a problem

China had some of the strictest and longest-lasting travel restrictions in the world, making it more difficult for scientists to meet potential collaborators. That led to policy changes in China that made international collaboration less important to researchers’ careers. For example, many Chinese institutions had required international collaborations for a researcher to be considered for promotion, but this was dropped during the pandemic, says Fei Shu, a consultant on research assessment at the University of Calgary in Canada. “I’m not sure if it will be brought back, but for now it’s not a requirement, so there is less motivation,” he says.

The Chinese Scholarship Council, a non-profit organization run by the Chinese Ministry of Education, which pays for many Chinese academics to spend time as visiting scholars abroad, also paused funding during the pandemic, says Shu. It will take time for the number of Chinese scholars visiting the West to recover.

Although ways of facilitating virtual collaboration took off during the pandemic, Caroline Wagner, who studies international scientific collaboration at the Ohio State University in Columbus, says that face-to-face meetings are still crucial for bringing researchers together in the first place. “My research shows that 90% of international collaborations begin face-to-face, when people meet at conferences, research centres, or during visiting professorships,” she says. “Hardly any partnerships begin completely virtually.”

The importance of these kinds of personal relationship is especially apparent in US–China collaborations, says Richard Freeman, an economist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. One analysis shows that 78.5% of collaborative US–China papers have at least one Chinese author who either works as a scientist at a US institution or has returned home after studying in the United States 1 . It is clear that the disruption of the pandemic will have a notable effect on collaborations for some time, says Wagner.

Larger trends

Both Wagner and Freeman also noticed a pre-pandemic drop — particularly in US–China collaboration — in their own research, which uses much larger databases than the Nature Index.

Freeman says that some of this is simply owing to relative shifts in domestic and international publishing. His work found that, despite the drop in US–China collaboration, there was a rise in the total number of international collaborative papers published between 2018 and 2022. But there was a much larger increase in the number of papers with only China-based authors — often people who had been educated solely in China and who had little or no international experience. “China has ramped up domestic science so much, and international collaborations are not keeping pace,” says Freeman.

That increase, and the high quality of the country’s domestic publications, means that international collaboration might be becoming less necessary. “As China makes more progress, the need for collaboration could diminish in some fields,” says Simon. “They have enough options within the country to produce good partners.”

Domestic collaborations tend to go more smoothly than international ones during times of pandemic disruption and political tensions, he adds.

Certain policies in Chinese academia might also be driving the trend. In many cases, says Shu, only the first author of a paper gets credit for a publication in China’s evaluation and promotion systems. So China-based researchers might be less motivated to collaborate internationally if they will end up in the middle of the author list. “They will focus on their own projects, and may be less likely to join others’ projects,” he says.

The Chinese government has also been trying to encourage scientists to publish more of their work in Chinese journals, rather than international publications, says Simon. More collaborative research might gradually be appearing in local journals.

‘A new cold war’

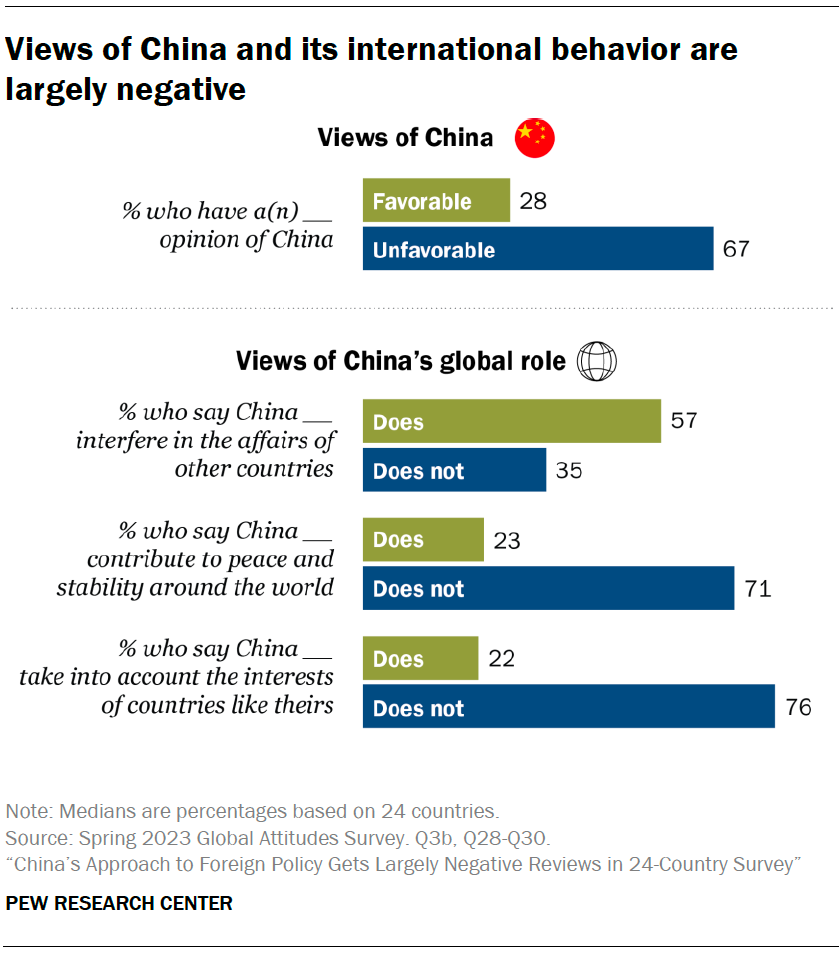

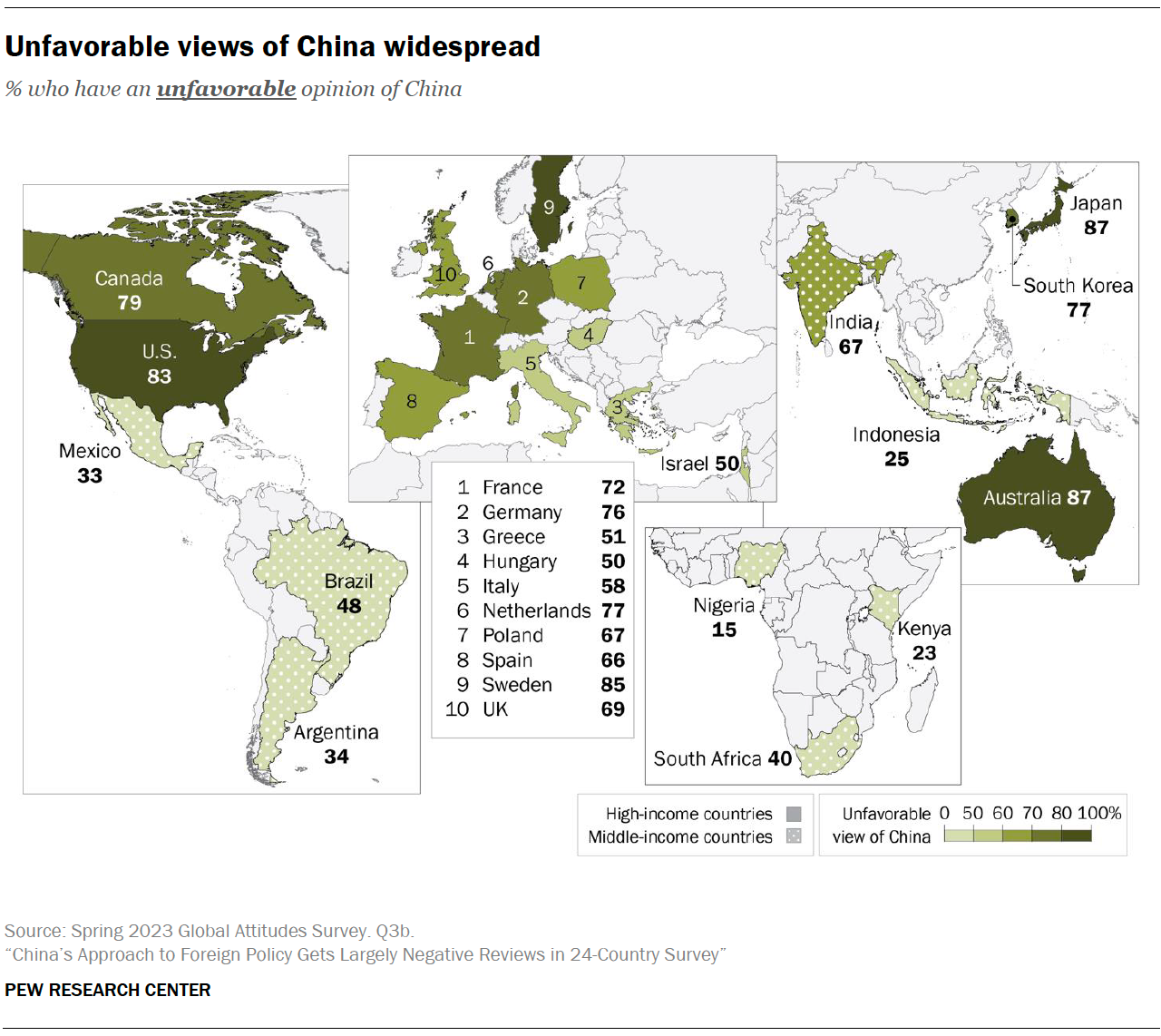

Political tensions between China and many Western nations are also taking a toll on collaboration. Many Western governments have become more suspicious of Chinese scientists in the past five to six years, with fears that they might be part of attempts to steal technology and cutting-edge research.

The US China Initiative, launched under former US president Donald Trump in 2018, led to fraud cases being brought against researchers who failed to disclose ties to China on grant applications, although many of those charges were later dropped. Earlier this year, Canada banned government funding for research collaborations involving scientists with connections to the defence or state-security entities of foreign countries that it deems a risk to Canada’s national security. Germany is developing a similar policy.

The heightened suspicion has led to lengthy and complex visa processes, which are starting to discourage some Chinese scientists from visiting Western countries. “I have colleagues who spent six months waiting to get a visa for a conference,” says Shu. “This side effect of these political issues is having a heavy influence on scientific collaboration. The last four to five years have been like a new cold war.”

The tense political climate is having a chilling effect on collaboration, says Simon. “Chinese scientists don’t know if they are going to get fingered for doing something nefarious, even when they are not,” he says. “They may decide it’s not worth the risk.”

Earlier this year, Simon resigned from his job at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in protest against what he saw as the university’s restrictive policies on Chinese collaborations. He told Times Higher Education ( THE ) that he had faced undue bureaucracy when organizing research trips to China, had been stopped from taking students to visit the country, and that the university had tried to shut down an informal policy discussion that he had arranged between colleagues and Chinese embassy staff. The university would not comment on personnel matters, but told THE that it had had a “steadfast commitment to maintaining the integrity of research” and “take[s] very seriously legitimate concerns about the need to safeguard US academic research from improper foreign influence”.

There are still many countries that would welcome collaboration with China, however. The balance might be shifting away from the scientific powerhouses of the West to other countries, such as those taking part in China’s Belt and Road Initiative — a global infrastructure-development strategy aimed at improving trade — most of whose members are countries in Asia, the Middle East, Africa and South America. The results of these collaborations might be published in a broader variety of journals, but this might not be of concern to China if its ultimate goal is wider scientific influence. “China is expanding its collaborative footprint around the world. For example, they have signed science and technology cooperative agreements with 116 countries,” says Wagner. China has also made agreements with middle- and low-income nations in South America and Africa. “So, perhaps there is less focus on the elite journals.”

It is important not to extrapolate an irreversible trend from these data. Relations between China and the West might slowly begin to improve in the future: the China Initiative was discontinued in February, and the United States and China renewed their science and technology cooperation agreement in August, although only for six months. Wagner and Simon both say that their colleagues in China remain keen to work with international peers. A forum on open innovation in China in May, that Simon attended, featured a letter from Chinese President Xi Jinping, stressing the importance of international collaboration.

“My sense is that China is still very highly engaged in international science,” says Simon. “Even if the US relationship is in decline, China wants to maintain its relationship with other countries.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03762-4

Xie, Q. & Freeman, R. B. NBER https://doi.org/10.3386/w31306 (2023).

Article Google Scholar

Download references

Related Articles

Standardized metadata for biological samples could unlock the potential of collections

Correspondence 14 MAY 24

A guide to the Nature Index

Nature Index 13 MAR 24

Decoding chromatin states by proteomic profiling of nucleosome readers

Article 06 MAR 24

Protests over Israel-Hamas war have torn US universities apart: what’s next?

News Explainer 22 MAY 24

A DARPA-like agency could boost EU innovation — but cannot come at the expense of existing schemes

Editorial 14 MAY 24

Dozens of Brazilian universities hit by strikes over academic wages

News 08 MAY 24

US halts funding to controversial virus-hunting group: what researchers think

News 16 MAY 24

Professor, Division Director, Translational and Clinical Pharmacology

Cincinnati Children’s seeks a director of the Division of Translational and Clinical Pharmacology.

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati Children's Hospital & Medical Center

Data Analyst for Gene Regulation as an Academic Functional Specialist

The Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn is an international research university with a broad spectrum of subjects. With 200 years of his...

53113, Bonn (DE)

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität

Recruitment of Global Talent at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

The Institute of Zoology (IOZ), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), is seeking global talents around the world.

Beijing, China

Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

Full Professorship (W3) in “Organic Environmental Geochemistry (f/m/d)

The Institute of Earth Sciences within the Faculty of Chemistry and Earth Sciences at Heidelberg University invites applications for a FULL PROFE...

Heidelberg, Brandenburg (DE)

Universität Heidelberg

Postdoctoral scholarship in Structural biology of neurodegeneration

A 2-year fellowship in multidisciplinary project combining molecular, structural and cell biology approaches to understand neurodegenerative disease

Umeå, Sweden

Umeå University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

China now publishes more high-quality science than any other nation – should the US be worried?

Milton & Roslyn Wolf Chair in International Affairs, The Ohio State University

Disclosure statement

Caroline Wagner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Ohio State University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

By at least one measure, China now leads the world in producing high-quality science . My research shows that Chinese scholars now publish a larger fraction of the top 1% most cited scientific papers globally than scientists from any other country.

I am a policy expert and analyst who studies how governmental investment in science, technology and innovation improves social welfare. While a country’s scientific prowess is somewhat difficult to quantify, I’d argue that the amount of money spent on scientific research, the number of scholarly papers published and the quality of those papers are good stand-in measures.

China is not the only nation to drastically improve its science capacity in recent years, but China’s rise has been particularly dramatic. This has left U.S. policy experts and government officials worried about how China’s scientific supremacy will shift the global balance of power . China’s recent ascendancy results from years of governmental policy aiming to be tops in science and technology. The country has taken explicit steps to get where it is today, and the U.S. now has a choice to make about how to respond to a scientifically competitive China.

Growth across decades

In 1977, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping introduced the Four Modernizations , one of which was strengthening China’s science sector and technological progress. As recently as 2000, the U.S. produced many times the number of scientific papers as China annually. However, over the past three decades or so, China has invested funds to grow domestic research capabilities, to send students and researchers abroad to study, and to encourage Chinese businesses to shift to manufacturing high-tech products.

Since 2000, China has sent an estimated 5.2 million students and scholars to study abroad . The majority of them studied science or engineering. Many of these students remained where they studied, but an increasing number return to China to work in well-resourced laboratories and high-tech companies.

Today, China is second only to the U.S. in how much it spends on science and technology . Chinese universities now produce the largest number of engineering Ph.D.s in the world, and the quality of Chinese universities has dramatically improved in recent years .

Producing more and better science

Thanks to all this investment and a growing, capable workforce, China’s scientific output – as measured by the number of total published papers – has increased steadily over the years. In 2017, Chinese scholars published more scientific papers than U.S. researchers for the first time.

Quantity does not necessarily mean quality though. For many years, researchers in the West wrote off Chinese research as low quality and often as simply imitating research from the U.S. and Europe . During the 2000s and 2010s, much of the work coming from China did not receive significant attention from the global scientific community.

But as China has continued to invest in science, I began to wonder whether the explosion in the quantity of research was accompanied by improving quality.

To quantify China’s scientific strength, my colleagues and I looked at citations. A citation is when an academic paper is referenced – or cited – by another paper. We considered that the more times a paper has been cited, the higher quality and more influential the work. Given that logic, the top 1% most cited papers should represent the upper echelon of high-quality science.

My colleagues and I counted how many papers published by a country were in the top 1% of science as measured by the number of citations in various disciplines. Going year by year from 2015 to 2019, we then compared different countries. We were surprised to find that in 2019, Chinese authors published a greater percentage of the most influential papers , with China claiming 8,422 articles in the top category, while the U.S had 7,959 and the European Union had 6,074. In just one recent example, we found that in 2022, Chinese researchers published three times as many papers on artificial intelligence as U.S. researchers; in the top 1% most cited AI research, Chinese papers outnumbered U.S. papers by a 2-to-1 ratio. Similar patterns can be seen with China leading in the top 1% most cited papers in nanoscience, chemistry and transportation.

Our research also found that Chinese research was surprisingly novel and creative – and not simply copying western researchers. To measure this, we looked at the mix of disciplines referenced in scientific papers. The more diverse and varied the referenced research was in a single paper, the more interdisciplinary and novel we considered the work. We found Chinese research to be as innovative as other top performing countries.

Taken together, these measures suggest that China is now no longer an imitator nor producer of only low-quality science. China is now a scientific power on par with the U.S. and Europe, both in quantity and in quality.

Fear or collaboration?

Scientific capability is intricately tied to both military and economic power. Because of this relationship, many in the U.S. – from politicians to policy experts – have expressed concern that China’s scientific rise is a threat to the U.S., and the government has taken steps to slow China’s growth. The recent Chips and Science Act of 2022 explicitly limits cooperation with China in some areas of research and manufacturing. In October 2022, the Biden administration put restrictions in place to limit China’s access to key technologies with military applications .

A number of scholars, including me, see these fears and policy responses as rooted in a nationalistic view that doesn’t wholly map onto the global endeavor of science.

Academic research in the modern world is in large part driven by the exchange of ideas and information. The results are published in publicly available journals that anyone can read. Science is also becoming ever more international and collaborative , with researchers around the world depending on each other to push their fields forward. Recent collaborative research on cancer , COVID-19 and agriculture are just a few of many examples. My own work has also shown that when researchers from China and the U.S. collaborate, they produce higher quality science than either one alone.

China has joined the ranks of top scientific and technological nations, and some of the concerns over shifts of power are reasonable in my view. But the U.S. can also benefit from China’s scientific rise. With many global issues facing the planet – like climate change , to name just one – there may be wisdom in looking at this new situation as not only a threat, but also an opportunity.

- Geopolitics

- Science policy

- Globalization

- Science and technology

- Chinese science

- CHIPS and Science Act

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, africa's oil economies amidst the energy transition: nigeria, china's rise, russia's invasion, and america's struggle to defend the west: a conversation with david sanger, the axis of upheaval: capital cable #95, adopting ai in the workplace: the eeoc's approach to governance.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

China Power Project

Chinese business and economics.

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Critical Minerals Security

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation Project

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Transnational Threats Project

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

CSIS research on China, led by Freeman Chair in China Studies , the China Power Project , and the Chinese Business and Economics programs, seeks to advance popular understanding and inform U.S. policy on the global implications of the country's rise.

The Defense Industrial Implications of Putin’s Appointment of Andrey Belousov as Minister of Defense

An audio version of “The Defense Industrial Implications of Putin’s Appointment of Andrey Belousov as Minister of Defense,” a new commentary by CSIS’s Nicholas Velazquez, Maeve Sockwell, and Cynthia Cook. This audio was generated with text-to-speech by Eleven Labs.

Podcast Episode by Nicholas Velazquez, Maeve Sockwell, and Cynthia Cook — May 23, 2024

Commentary by Nicholas Velazquez, Maeve Sockwell, and Cynthia Cook — May 23, 2024

Featured Contribution: Korea’s Role as a Facilitator of Trilateral Cooperation in Northeast Asia

Newsletter by Park Cheol Hee — May 23, 2024

Collaboration for a Price: Russian Military-Technical Cooperation with China, Iran, and North Korea

Podcast Episode by Max Bergmann, Maria Snegovaya, Tina Dolbaia, and Nick Fenton — May 23, 2024

Latest Podcast Episodes

Intellectual property rights in the u.s.-china innovation competition.

Podcast Episode by Chris Borges — May 17, 2024

Taiwan's Upcoming Presidential Inauguration: A Conversation with Dr. Lauren Dickey

Podcast Episode by Bonny Lin and Lauren Dickey — May 17, 2024

Beyond China's Black Box

Podcast Episode by Jude Blanchette — May 16, 2024

Face Off: US-China

Podcast Episode by H. Andrew Schwartz — May 16, 2024

Featured Digital Report

Photo: Naval Air Crewman 1st Class Justin Sherman/U.S. Air Force

In the Shadow of Warships

How foreign companies help modernize China’s navy

Digital Report by Matthew P. Funaiole, Brian Hart, and Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. — December 15, 2021

Recent Events

The Erosion of Hong Kong’s Autonomy Since 2020: Implications for the United States

The Future of the Indo-Pacific with the Coast Guard Commandant

The Belt and Road Initiative at 10: Challenges and Opportunities

Book Event: The Mountains Are High

Book Event - We Win, They Lose: Republican Foreign Policy & the New Cold War

Chinese Interference in Taiwan's 2024 Elections and Lessons Learned

China’s Tech Sector: Economic Champions, Regulatory Targets

Chinese Assessments of AI: Risks and Approaches to Mitigation

Related programs.

Hidden Reach

Jude Blanchette

Scott Kennedy

Christopher B. Johnstone

Matthew P. Funaiole

Ilaria Mazzocco

Benjamin Jensen

Lily McElwee

Harrison Prétat

All china content, type open filter submenu.

- Article (609)

- Event (428)

- Expert/Staff (49)

- Podcast Episode (684)

- Podcast Series (3)

- Report (314)

Article Type open filter submenu

Report type open filter submenu, topic open filter submenu.

- American Innovation (17)

- Artificial Intelligence (18)

- Asian Economics (427)

- Civic Education (1)

- Civil Society (21)

- Climate Change (69)

- Counterterrorism and Homeland Security (34)

- COVID-19 (64)

- Cybersecurity (88)

- Data Governance (30)

- Defense and Security (521)

- Defense Budget and Acquisition (13)

- Defense Industry, Acquisition, and Innovation (29)

- Defense Strategy and Capabilities (154)

- Economics (617)

- Energy and Geopolitics (89)

- Energy and Sustainability (144)

- Energy Innovation (32)

- Energy Markets, Trends, and Outlooks (54)

- Family Planning, Maternal and Child Health, and Immunizations (4)

- Food Security (20)

- Gender and International Security (24)

- Geopolitics and International Security (628)

- Global Economic Governance (210)

- Global Health (56)

- Governance and Rule of Law (115)

- Health and Security (31)

- Humanitarian Assistance (7)

- Human Mobility (3)

- Human Rights (65)

- Human Security (11)

- Infectious Disease (35)

- Intellectual Property (7)

- Intelligence (6)

- Intelligence, Surveillance, and Privacy (58)

- International Development (184)

- Maritime Issues and Oceans (26)

- Military Technology (57)

- Missile Defense (8)

- Multilateral Institutions (11)

- Nuclear Issues (32)

- On the Horizon (2)

- Private Sector Development (36)

- Satellite Imagery (12)

- Technology (231)

- Technology and Innovation (175)

- Trade and International Business (480)

- Transitional Justice (2)

- Transnational Threats (7)

- U.S. Development Policy (55)

- Water Security (2)

On the 95th episode of The Capital Cable, we are joined by Richard Fontaine to discuss the "axis of upheaval" and how America's adversaries, China, Iran, North Korea and Russia are uniting to overtn the global order.

Event — May 30, 2024

An audio version of Collaboration for a Price: Russian Military-Technical Cooperation with China, Iran, and North Korea , a new report by CSIS’s Max Bergmann, Maria Snegovaya, Tina Dolbaia, and Nick Fenton. This audio was generated with text-to-speech by Eleven Labs.

On May 14, 2024, Andrey Belousov assumed the office of Russian minister of defense. He succeeded long-time Putin ally Sergei Shoigu and is set to apply his economic background to posture Russia for a prolonged conflict in Ukraine.

Park Cheol Hee, Chancellor of Korea National Diplomatic Academy discusses the significance of the Ninth Trilateral Summit Meeting among the Republic of Korea, Japan, and the People's Republic of China on May 26 and 27 and Korea's role as a facilitator of trilateral cooperation in Northeast Asia.

Russia has directly benefited from increased military-technical partnerships with China, Iran, and North Korea, with these countries allowing the Kremlin to maintain consistent intensity of attacks on Ukraine and contributing to Russia’s battlefield successes.

Report by Max Bergmann, Maria Snegovaya, Tina Dolbaia, and Nick Fenton — May 22, 2024

How Foes Can Defeat a Common Enemy: U.S.-China Collaboration to Combat Ebola

Gayle Smith, CEO of the ONE Campaign and former administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), details the spread of Ebola in the mid-2010s and how the United States and China came together to address the crisis.

Brief by Gayle Smith — May 21, 2024

An audio version of “Intellectual Property Rights in the U.S.-China Innovation Competition,” a new commentary by CSIS’s Chris Borges. This audio was generated with text-to-speech by Eleven Labs.

In this episode of the China Power Podcast, Dr. Lauren Dickey joins us to discuss Taiwan’s upcoming inauguration of president-elect William Lai.

Mexico Imposes Tariffs on China

Mariana speaks with Juan Carlos Baker about the recent Chinese investment announcements in Mexico.

Podcast Episode by Mariana Campero — May 16, 2024

Advertisement

China’s Research Evaluation Reform: What are the Consequences for Global Science?

- Published: 30 April 2022

- Volume 60 , pages 329–347, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Fei Shu 1 , 2 ,

- Sichen Liu 1 &

- Vincent Larivière ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2733-0689 2 , 3

9830 Accesses

17 Citations

29 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In the 1990s, China created a research evaluation system based on publications indexed in the Science Citation Index (SCI) and on the Journal Impact Factor. Such system helped the country become the largest contributor to the scientific literature and increased the position of Chinese universities in international rankings. Although the system had been criticized by many because of its adverse effects, the policy reform for research evaluation crawled until the breakout of the COVID-19 pandemic, which accidently accelerates the process of policy reform. This paper highlights the background and principles of this reform, provides evidence of its effects, and discusses the implications for global science.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Evolution of Research Evaluation in China

`Walking between the lines’: research evaluation in China beyond COVID-19

Research Assessment in the Humanities: Introduction

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In parallel with the exponential growth of its economy, China’s emergence in science and technology has had a far-reaching impact on global science. In 2017, China has surpassed the US and became the largest source country in terms of the number of scholarly papers (National Science Board 2018 ), and its R&D expenditures are almost on par with those of the US (543 vs. 582 billion USD in 2018) (UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2018 ). Such growth in international research output can be associated with the implementation of China’s national strategy of science and education, in which science, technology and education are given priority in the national development plan (National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China 2007 ). The key elements of the national strategy include the increasing investment in R&D and promotion of internationalisation of research (Marginson 2021 ). It is also partly attributed to the creation of a SCI-based research evaluation system, favoring publications indexed by the Science Citation Index (SCI). Since the 1990s, the number of such international publications as well as other related bibliometric indicators (e.g. Journal Impact Factors (JIF), Essential Science Indicators (ESI), etc.) have been overweighed in research evaluation, tenure assessment, funding application as well as performance salaries in China (Quan et al. 2017 ; Shu et al. 2020a ) to develop China’s leadership in global science.

In China, SCI-based indicators are applied to research evaluations at both individual and institutional levels. However, they have been criticized for their negative effects on academic integrity (Quan et al. 2017 ; Tang 2019 ) and national knowledge dissemination (Chu et al. 2015 ; Duan et al. 2015 ; W. Li et al. 2015 ; C.-e. Liu 2018 ; Yanyang Liu et al. 2003 ; X. Wang 2012 ; Jiping Zhang 2019 ; Zhu 2020 ; Zou and Zhang 2017 ) for several years. A policy reform against indicator-based research evaluation has also been called for a long time (L. Zhang and Sivertsen 2020 ). As early as 2011, Ministry of Education (MoE) issued a document regarding the change of research evaluation in social sciences and humanities (Ministry of Education of China 2011 ). The policy reform even gained the attention from China’s leaders; in 2016, China’s Chairman Xi ( 2016 ) asked Chinese scientists to “publish papers on homeland”. As a response in 2018, MoE, Ministry of Science and Technology of China (MoST), Ministry of Human Resource and Social Security (MoHRSS), Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), and Chinese Academy of Engineering (CAE) issued a joint document asking universities and research institutes not to abusively use indicators relative to papers, titles, ranks, degrees and awards (Ministry of Education of China 2018 ). However, significant changes were not observed in China’s research evaluation system, and SCI-based indicators have still been abundantly used.

Perhaps unexpectedly, a real change to the SCI-based evaluation system was triggered by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Chinese researchers prioritized publication of findings on the new coronavirus in international journals (Huang et al. 2020 ; Q. Li et al. 2020 ) rather than national journals, which would have helped disseminating them to those who were fighting the pandemic (Ministry of Science and Technology of China 2020a ). The publication of these two articles aroused public anger and was accused of delaying the control of the pandemic (An 2020 ; Du 2020 ; Qin 2020 ). In response to this (H. Li 2020 ; Yan Liu 2020 ), MoST and MoE issued two official documents in February 2020 that aim to reshape scholarly communication and research evaluation in China (Ministry of Education of China and Ministry of Science and Technology of China 2020a , b ; Ministry of Science and Technology of China 2020b ), which attempt to overcome the abusive use of SCI-based indicators on research evaluation (Quan et al. 2017 ; Shu et al. 2020a ) and build a new scientific research evaluation system.

As the largest contributor, China publishes almost one fourth of scientific literature and one fifth of international collaboration (ISTIC 2020 ). The possible impact of China’s research evaluation reform on global science has been of concern (Mallapaty 2020 ). In this study, we highlight the principles of policy reform as well as their background, and analyze the possible implications for global science.

Policy Reform

The two documents issued by MoE and MoST contain seven major measures, which can be divided into three aspects of scholarly communication and research evaluation as shown in Table 1 .

Farewell to the SCI

SCI-based indicators were introduced in the 1990s when the country initiated its ambious plan Footnote 1 to embrace the global science. Nanjing University was the first university to use SCI papers for research evaluation, and topped China’s university rankings afterwards. SCI-based indicators then spread across the country, as research administrators regarded them as a solution to increase China’s share of international publications (Qiu and Ji 2003 ). Many Chinese scholars also believed that SCI-based indicators were fairer than peer review, which was considered to be biased by personal relationship and seniority in China (Shi and Rao 2010 ).

In order to promote university research, three national programs (i.e., Project 211, Project 985, and Double First Class) have been initiated one by one since the 1990s. These programs provide substantial financial support to a small group of selected universities, and one key admission requirement is the number of international publications (Shu et al. 2020b ). To encourage scholars to publish internationally and improve their rankings, Chinese universities apply the SCI-based indicators that have, since then, been considered as the gold standard in China’s research evaluation. SCI papers became mandatory requirements for doctoral degrees, faculty hiring and promotion, funding applications, and university rankings. Publishing in a subset of SCI-indexed elite journals leads to major research funding, as well as additional rewards, such as promotion from assistant to full professor, appointment as Chair or Dean, and even to university president (Shu et al. 2020a ). Cash-per-publication policies have also been widespread, leading to additional revenues of up to 1 million CNY per paper (150,000USD) (Quan et al. 2017 ).

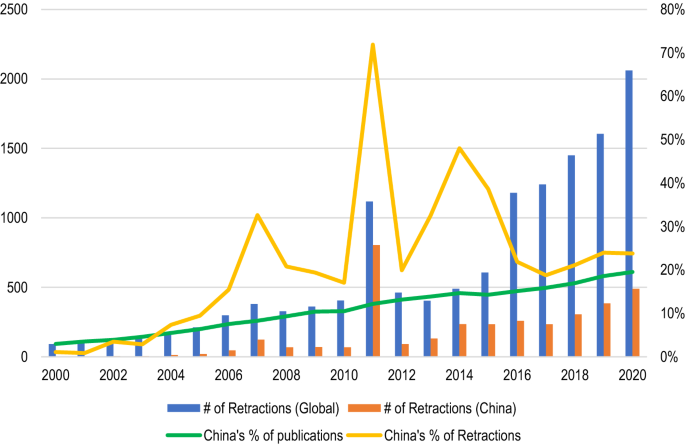

The strong pressures to publish in SCI journals may lead to the effect of goal displacement (Frey et al. 2013 ; Osterloh and Frey 2014 ) which the Chinese government became acutely aware of at the outbreak of the pandemic. The purpose of research for some Chinese institutions and scholars is not to advance knowledge, but rather to improve their rankings and indicators, even at the cost of research integrity (Tang 2019 ). Indeed, over the last two decaces, along with the growing number of international publications from China, cases of academic misconduct (plagiarism, academic dishonesty, ghostwritten papers, fake peer review, etc.) have also increased (Jia 2017 ; Hvistendahl 2013 ). The scale of adacemic misconduct cases evolved from individual cases to “paper mills” (Chawla 2020 ; Else and Van Noorden 2021 ). In this context, it is not surprising that the number of China’s retracted papers has been increasing in the past two decades, and China has the largest number of retracted papers, contributing to 24% of all retracted papers (490/2,061) in 2020, followed by the US (122) and Iran (79) as reported by Web of Science (Figure 1 ). Figure 1 also shows that the share of China’s retractions to all retractions across the world has been higher than the share of China’s publications to all publications worldwide since 2004.

Number and share of China’s publications and retractions indexed by the Web of Science (2000–2020)

Priority to National Journals

SCI-based evaluation policies have created incentives for Chinese scholars to publish their research in international journals rather than in national journals (Zou and Zhang 2017 ; C.-e. Liu 2018 ). In China, however, international journals are less accessible than national Chinese journals due to the paywalls and language (Schiermeier 2018 ). As a result, dissemination of findings to the international scientific community comes at the expense of the national Chinese community (Larivière et al. 2020 ), and this was clearly observed at the outbreak of the pandemic, when Chinese scholars disseminated their findings on human-to-human transmission of coronavirus internationally rather than nationally. Local health practitioners were not informed by their colleagues, but aware of such a crucial finding from the paper (Q. Li et al. 2020 ) published in the New England Journal of Medicine (Du 2020 ; Qin 2020 ; Wuhan Municipal Health Commission 2020 ).

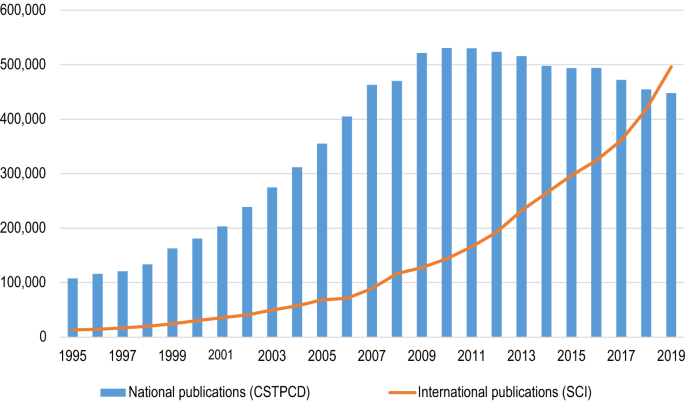

Since the end of World War II, dissemination of science has been dominated by English, leading to a corresponding decrease for other languages (Larivière and Warren 2019 ). This was also observed for papers published in Chinese, as the number of national publications indexed by China Scientific and Technical Papers and Citation Database (CSTPCD) Footnote 2 started to decrease in 2010 (Figure 2 ). In some disciplines such as Condensed Matter Physics, Applied Mathematics, or Crystallography and Electrochemistry, Chinese scholars even give up publishing papers in local Chinese journals (Shu et al. 2019 ). Some Chinese scholars argue that publishing internationally prevents knowledge dissemination through national journals (Zou and Zhang 2017 ; C.-e. Liu 2018 ). Indeed, in 2019, Chinese researchers have published more papers internationally than they have nationally for the first time.

Number of national and international publications in China (1995-2019) (National Bureau of Statistics of China 1996 –2019)

This can also be observed at the ownership shares of international journals: while Chinese researchers contribute to about 25% of international literature, less than 2% of these international journals are owned by Chinese publishers (ISTIC 2020 ). Such imbalance has been noted by China’s leaders, with Chairman Xi requesting that scientists publish nationally (Xi 2016 ). As a response (Ministry of Science and Technology of China 2020a ), the reform gives emphasis to national scholarly communication by requiring researchers to publish at least one third of their papers in national journals.

Restrictions to Open Access Publishing

Despite limited access to subscription journals (Schiermeier 2018 ), open access (OA) publishing remains controversial in China. Papers published in OA journals are often valued less as those published in subscription journals, and are even excluded from research evaluations. This can be attributed to the perception that OA journals are predatory and perform very little peer review (Li 2006 ; Xu et al. 2018 ; Liu and Huang 2007 ).

Despite this perception, the percentage of Chinese papers published in Gold OA journals has been increasing from 4.9% in 2008 to 30.0% in 2020 in the dimensions.ai database. This percentage is higher than that of the United States (20.5%) and the United Kingdom (21.5%), on a par with that of Japan (30.4%), but remains lower than that of Brazil (55.3%), which publishes mainly in the non-APC journals indexed by its national platform, SciELO. China is, however, among the countries with the lower share of hybrid OA (around 2%), which suggests that paying APCs in subscription journals is not rewarded. The main reason for Chinese scholars to choose OA journals is not research impact or global reach, but whether the journal is indexed by WoS (Xu et al. 2020 ). Commercial publishers have taken advantage of such focus on WoS, and created low quality journals with nominal or no peer review and quick acceptance (Xia et al. 2017 ). For example, IvySpring International Publisher, an Australian OA publisher, has four journals indexed by WoS; almost two thirds of papers published in 2018 were contributed by Chinese authors.

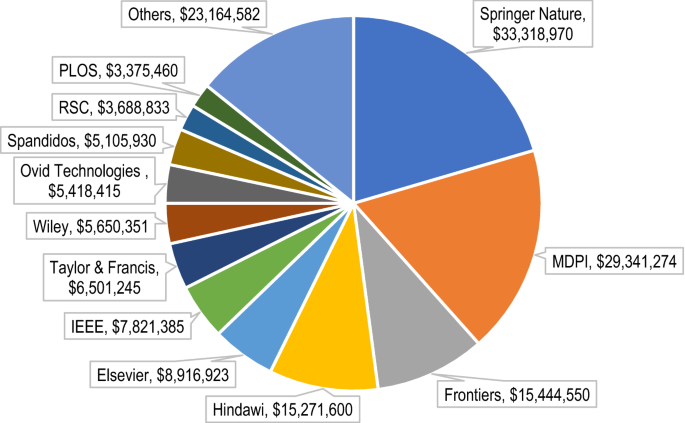

As most OA journals are published outside China, it is believed that a large amount of research funding is lost through APCs (Liu 2018 ). A list of APCs (in 2018) of all OA journals indexed by Web of Science was collected and built in this study. The number of APC paid, and APC revenue generated were calculated on the basis of first affiliated institution in the byline and regular APC rate. Although the APCs are normally billed to the corresponding authors, Chinese scholars only can receive the reimbursement of APC payments when their affiliated institutions are ranked first in the byline. In 2018, the 89,165 OA papers (Gold and Hybrid OA indexed by WoS) published by Chinese institutions as the first affiliated institution incurred around 165 million USD APCs as calculated. Springer Nature generated more than 33 million USD revenue from APCs in China, followed by MDPI (29 million USD), Frontiers (15 million USD) and Hindawi (15 million USD), which focus on the OA publishing (Figure 3 ).

Publishers’ share of China’s OA publishing (2018)

Since the 1990s, the number of international papers indexed by SCI has been applied to research evaluation in China to increase the international visibility of China’s research (Gong and Qu 2010 ; Quan et al. 2017 ). In addition to the research evaluation policies, monetary incentives and performance bonus are also used to encourage Chinese scholars to publish SCI papers (Peng 2011 ; Quan et al. 2017 ; Shu et al. 2020a ), eventually forming a SCI-based research evaluation system in which SCI-based indicators become the most important criterion in tenure assessment, funding application, university ranking and other research assessment activities (Quan et al. 2017 ; Zhao and Ma 2019 ; Shu et al. 2020a ). As a result, Chinese scholars, especially in Natural Sciences, are required to publish SCI papers for their tenure and promotion as university and research institutes rely on such SCI-based indicators for their ranking and funding records (Shu et al. 2020a ; Wang and Li 2015 ).

Although the SCI-based research evaluation system partly contributes to China’s rise in global science, the abusive use of SCI-based indicators in research evaluation has been criticized for a long time since international publications only do not adequately represent China’s research activities (Guan and He 2005 ; Shu et al. 2019 ; Jin and Rousseau 2004 ; Jin et al. 2002 ; Liang and Wu 2001 ; Moed 2002 ; Zhou and Leydesdorff 2007 ). Some scholars even point out that the increase of international publications may come at the expense of dissemination of research to local Chinese communities (Zou and Zhang 2017 ; Xu 2020 ; Liu 2018 ), considering many international publications are less accessible in China because of the paywalls and language barriers. Indeed, the number of local national publications in China has been declining in the past decade as Chinese scholars have published more international publications than local national publications since 2019 (ISTIC 2021 ).

In addition, the SCI-based research evaluation brings a negative goal displacement effect (Frey et al. 2013 ; Osterloh and Frey 2014 ) as the purpose of publishing for some Chinese scholars is not to advance and disseminate knowledge but to complete the research evaluation and receive monetary awards (Quan et al. 2017 ), forming a different reward system of science (Merton 1973 , 1957 ). Furthermore, with the growth of the number of international publications, the number of academic misconducts such as plagiarism, paper mills, fake peer review and so on have also been increasing in China, which seriously affects China’s academic reputation (Hu et al. 2019 ; Tang 2019 ).

Although a science policy reform regarding the SCI-based research evaluation has been called for several years, the SCI-based indicators are still favored by research administration. China’s research evaluation policy is trapped in a dilemma of antinomy (Zhou and Zhang 2017 )—some official documents against the use of SCI-based indicators were issued while some research programs using SCI-based indicators were still promoted (Zhao and Ma 2019 ).

Implications

The new policy by MoST and MoE aims to create a rebalance contributing to global science and supporting national interests. This will not only affect Chinese scholars but the international research community, as China is the largest source contributor to scientific literature. However, no immediate changes to Chinese researchers’ dissemination practices have been noticed over the last eighteen months as Chinese scholars published 590,649 papers indexed by WoS in 2020, reaching its historical high.

What are the Alternative Research Evaluation Criteria?

Although both MoST and MoE intend to say farewell to SCI-based evaluation, they did not reveal how to achieve this beyond general principles. The two ministries delegated this responsibility to provincial departments, which have to design new evaluation systems based on those principles. Considering the top-down administration model in China that officials get used to implementing the policies and executing the orders from the top, it is hard to imagine that the provincial departments could formulate any detailed policies regarding the new evaluation system in a short term. In the following 12 months, all 31 provincial divisions (including 22 provinces, 4 municipalities and 5 autonomous regions) answered the call from MoST and MoE, but in different ways. According to the documents collected in this study, 16 Provincial Departments of Science and Technology issued their corresponding documents while the rest only forwarded the two official documents of MoST and MoE. Furthermore, these 16 new provincial documents do not reveal any alternatives to the SCI, and simply quote the statements made by MoST and MoE.

Indeed, Chinese scholars pointed out the impossibility of finding an alternative in a short term (L. Yu 2020 ), considering the SCI-based research evaluation system has deep roots in China. MoST and MoE emphasize that the future of research evaluation lies in peer review. However, peer review in China is also very controversial, given the strong influence of guanxi (personal relationships) (Shi and Rao 2010 ). Along those lines, given its time and resource consuming aspect, it is difficult to complete a large amount of research evaluations through peer review only (Bornmann 2011 ).

The Voice of the Silent Majority

MoST is responsible for coordinating science and technology activities, whereas MoE administrates universities, which are responsible for most research conducted in the country (83.5% of monographs and 75.5% of journal articles) (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2019 ). National research institutes and funding agencies are affiliated to MoST while MoE operates national research programs such as Project 211, Project 985, and Double First-Class, which provide substantial financial support to a small group of selected universities. Thus, in such dual administration, the policy reform needs to be coordinated by both MoST and MoE.

However, that does not seem to be the case. For instance, the MoE does not seem to push the policy as much as the MoST. On the contrary, MoE keeps promoting the Double First-Class program, which uses WoS/ESI indicators as a key criterion for admission (Chen and Qiu 2019 ; G. Zhao and Ma 2019 ). Recently, MoE issued two documents regarding research evaluation in social sciences and humanities (Ministry of Education of China 2020 ) and university tenure assessment (Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and Ministry of Education of China 2021 ). Those did not contain anything new, and simply restated the measures announced in February 2020. Indeed, some universities have already figured out how to deal with the prohibition—they replaced direct cash-per-publication by a score assigned to each individual SCI paper… a score that could be converted into salary at the end of the year (Quan et al. 2017 ). Since the documents issued by MoST and MoE only prohibit direct cash awards for individual publications, universities or research institutes can use indirect monetary awards instead. Thus, we are far from a revolutionary change in the research evaluation practices of Chinese universities.

Global Leadership

In the 1990s, China launched an ambitious plan (Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and State Council of China 1995 ) for global leadership in science. One may consider the plan to be successful, as the country is now the largest contributor to research papers worldwide. China intends to expand its leadership to academic publishing. The purpose of the new China Science and Technology Journal Excellence Action Plan (CSTJEAP) is not only to encourage Chinese scientists to publish papers in national journals, but also to make their national journals more global.

CSTJEAP will not prevent Chinese researchers from publishing in top international journals. However, it aims to restrict publication in those with less impact, especially Gold and Hybrid OA journals with APCs. For example, we may no longer see many Chinese papers in the Czech Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding (an OA journal indexed by WoS), in which more than half of papers published in 2018 came from Chinese authors. Indeed, those 89,165 China’s OA papers (either Gold or Hybrid OA) were published in 2,638 journals indexed by WoS in 2018; as Table 2 shows, only 335 and 913 journals were respectively included in Quartile 1 of Chinese Academy of Science Journal Partition (CASJP) and Journal Citation Report (JCR) that are used to define the high-quality journals in China. It means that the vast majority of OA papers (between 58,769 and 83,961) are ineligible to be high quality publications (HQPs) for the reimbursement of APCs under the new policy. This may also lead to a decrease of 14.1–20.3% in OA publications worldwide.

Uncertain Future

More than 30 years ago, China opened its doors to the West and embraced the international society; since then, China’s economy has experienced a tremendous growth and has become the fastest growing economy in the world. As a rising power, China created tensions challenging the existing international order (Kim and Gates 2015 ; Punnoose and Vinodan 2019 ), controlled and dominated by Western countries. Under the leadership of Chairman Xi, China has adopted an increasingly ambitious strategy pursuing global leadership not only in politics and economics but also in science, which will influence China’s science policies in the future.

In Chinese perspectives, although China is the largest contributor to global science, its power of discourse (Foucault 1971 ) in academia is still limited as the international scholarly communication system is controlled by Western countries in terms of academic journals, professional association, and academic norms (Zhang 2012 ; Liang 2014 ; Wang 2011 ). It is believed that the Western-centrism (Hobson 2012 ) exists in global science (especially in social sciences) as research topics, paradigms, methodologies, and evaluation are dominated by Western countries through their control over international scholarly communication venues as well as their peer-review process (Yu and Qiu 2021 ; Zhang 2016 ; Wang 2011 ). Some scholars even argue that Western countries use scholarly communication to disseminate Western culture, value and ideology for the purpose of politics (Jiang 2018 ; Xie 2014 ; Zhao 2020 ).

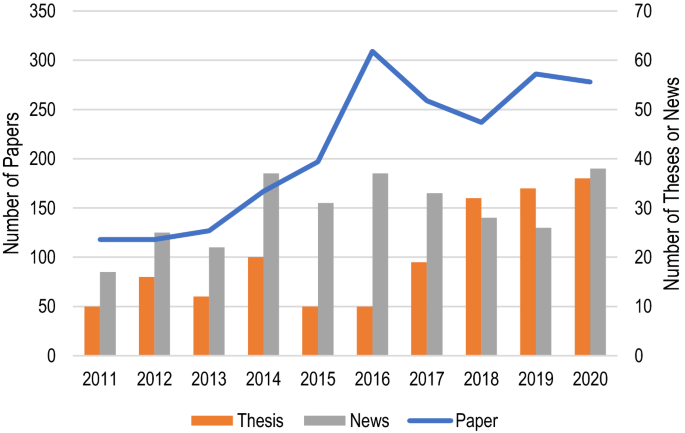

With the increase of the global share of scientific literature, Chinese scholars attempt to convert their roles in global science, from participants to leaders; sharing and gaining the power of academic discourse is considered as the prerequisite (Zhang 2016 ; Xu 2020 ; Zhang 2012 ; Shen 2016 ; Hu 2013 ). One example is that IEEE had to drop its ban on using Huawei scientists as reviewers under the pressure amid boycott from China’s academia (Mervis 2019 ; IEEE 2019 ). Indeed, Academic Discourse Power has become a popular research and news topic in China in the past decade (Figure 4 ). Some proposals suggest building a new global scholarly communication system including China-owned English journals, self-reliant citation index, and a database indexing English abstracts of Chinese papers (Wu and Tong 2017 ; Zhou 2012 ; Zhang and Zhen 2017 ; Fang 2020 ; Lu 2018 ), which was adopted in the two official documents by MoST and MoE.

Number of Chinese Publications Regarding Academic Discourse Power from CNKI (2011–2020)

Recently, China released its 14th five-year social and economic development plan, which identifies scholarly communication as an approach disseminating China’s culture, beliefs and values, and emphasises more self-reliance rather than international collaboration in science and technology development (Government of People's Republic of China 2021 ). The plan mentions the proposal building a national scholarly communication system in response to Chairman Xi’s call to “publish papers on homeland” (Xi 2016 ). Although these long term goals will not come into effect immediately, even be replaced by other strategies in the next five-year plan, they create uncertainty for the future of global science considering the possible conflict between the rising power and traditional powers in science.

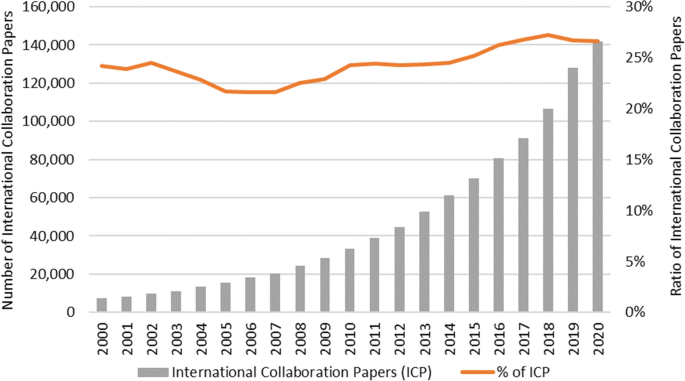

China’s future involvement in international collaboration is another uncertain consequence to global science. In the past decades, China has been promoting international collaborations through various mobility funding initiatives (Quan et al. 2019 ). The China Scholarship Council, administrated by MoE, annually funds almost 20,000 Chinese scholars for a 6–12-month international stay as visiting scholars (Wu 2017 ), while National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), administrated by MoST, offers funding for foreign researchers to encourage international collaboration (Yuan et al. 2018 ). As Figure 5 shows, the number of international collaboration papers (indexed by WoS) in China has been increasing in the past two decades; however, the ratio of international collaboration papers to all international papers decreased in 2019 and 2020. We are not sure whether the decrease is attributed to the policy reform or due to the pandemic when international mobility was strictly limited (Lee and Haupt 2021 ).

International Collaboration Publications in China (2000–2020)

Two years into the pandemic, the documents issued by MoST and MoE appear more like a communication exercise to appease public anger than the start of a strong policy reform. With the top-down administration model based on the centralized Chinese government, the SCI-based evaluation system was promoted from the top (e.g., MoST, MoE, etc.) and followed by the bottom (e.g., universities, research institutes, etc.). Thus, the MoST and MoE should not shirk their responsibilities and create ambiguous and non-transparent policies (Qi 2017 ; Shu et al. 2020b ) when promoting the policy reform. For example, MoE should reconstruct the Double First Class program that is highly based on ESI indicators (Chen and Qiu 2019 ; Zhao and Ma 2019 ); MSFC, administrated by MoST, should give national publications the same weight as international publications when evaluating funding applications. Chinese universities and research institutes need to receive a clear and consistent signal that the policy reform is not only an armchair strategist.

Indeed, many negative effects don’t originate from the nature of the SCI-based indicators but come from the administrative purpose of research evaluation, which contributed many “beautiful” numbers in terms of the number of publications and rankings rather than real advancement of knowledge. China’s scientific administration should be aware that a successful research evaluation system should be completely merit-based; and the policy reform should start from the top.

In July 2021, the General Office of the State Council of China ( 2021 ) issued another new document providing the principles for designing a new research evaluation system in science and technology, which duplicates most contents of previous documents. Unfortunately, a detailed proposal regarding the new research evaluation system is still missing.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Although the first Chinese scientific development plan (Project 863) started in 1986, the milestone of China’s scientific development is Xiaoping Deng’s (China’s former leader) declaration “Science and technology are primary productive forces” in 1988, which has guided China’s scientific development in several decades. In 1993, China legislated the first version of the Law of the People's Republic of China on Science and Technology Progress; in 1995, China initiated the national strategy of “invigorating China through the development of science and education”. As a result, Project 211 and Project 985 were launched in 1995 and 1998 respectively.

CSTPCD, developed by the Institute of Scientific and Technical Information of China (ISTIC) in 1987, indexes more than 2,000 national scientific journals for the purpose of research evaluation of China’s scientists and engineers. The number of papers indexed by CSTPCD and number of Chinese papers indexed by SCI, representing national and international publications respectively, are reported in annual Statistical Data of China’s S&T Papers , and included in the China Statistical Yearbook .

An, Delie. 2020. Guan yu wu han fei yan de ke xue lun wen yin bao zheng yi (Scientific paper on Wuhan coronavirus sparks controversy). Radio France Internationale. https://www.rfi.fr/cn/20200131-%E5%85%B3%E4%BA%8E%E6%AD%A6%E6%B1%89%E8%82%BA%E7%82%8E%E7%9A%84%E7%A7%91%E5%AD%A6%E8%AE%BA%E6%96%87%E5%BC%95%E7%88%86%E4%BA%89%E8%AE%AE-%E7%A9%B6%E7%AB%9F%E8%B0%81%E5%9C%A8%E7%94%A9%E9%94%85 . Accessed 31 January 2022.

Bornmann, Lutz. 2011. Scientific peer review. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 45(1): 197–245.

Article Google Scholar

Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, and State Council of China. 1995. Guan yu jia su ke xue ji shu jin bu de jue ding (Decision on Accelerating the Advancement of Science and Technology). Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Chawla, Dalmeet. 2020. A single ‘paper mill’ appears to have churned out 400 papers. Science . https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/02/single-paper-mill-appears-have-churned-out-400-papers-sleuths-find . Accessed 31 January 2022.

Chen, Shiji, and Jun-ping Qiu. 2019. Yi liu xue ke yu xue ke pai ming de dui bi yan jiu — ji yu jiao yu bu xue ke ping gu, ESI he QS xue ke pai ming de yi liu xue ke dui bi fen xi (A comparative study of first-class disciplines and discipline rankings—a comparative analysis of first-class disciplines based on the discipline evaluation of the Ministry of Education, ESI and QS discipline rankings). Evaluation and Management 17(4): 27–32.

Google Scholar

Chu, Jingli, Hongxiang Zhang, and Zheng Wang. 2015. Dui Ke Ji Qi Kan Ji Qi Yu Xue Shu Ping Jia Guan Xi De Ren Zhi Yu Jian Yi —10 Suo Da Xue Yu Ke Yan Ji Gou Ke Yan Ren Yuan Fang Tan Lu (The recognition and suggestion on the relationship between scholarly journals and Research Evaluation: Interviews with scholars from 10 universities). Chinese Journal of Scientific and Technical Periodicals 26(8): 785–791.

Du, Hu. 2020. Qiang fa lun wen dan wu ji kong? (Rushing to publish papers delays disease control). Sohu. https://www.sohu.com/a/369715786_665455 . Accessed 31 January 2022.

Duan, Zhiguang, Yanbo Zhang, and Lijun Yang. 2015. SCI Ping Jia Zhi Biao Yu Di Fang Yi Xue Yuan Xiao De Jian She Fa Zhan (The SCI indicators and the development of local medical schools). Medicine and Philosophy 36(1): 4–7.

Else, Holly, and Richard Van Noorden. 2021. The fight against fake-paper factories that churn out sham science. Nature 591(7851): 516–519.

Fang, Qing. 2020. Chuang Xin Xue Shu Chu Ban Ti Zhi Ji Zhi Zhu Li Xue Shu Hua Yu Quan Jian She (Innovate the academic publishing system and mechanism to help the construction of academic discourse power). Publishing Journal 28(2): 1.

Foucault, Michel. 1971. L’ordre du discours: leçon inaugurale au Collège de France prononcée le 2 décembre 1970 . Paris: Gallimard.

Frey, Bruno S., Fabian Homberg, and Margot Osterloh. 2013. Organizational control systems and pay-for-performance in the public service. Organization Studies 34(7): 949–972.

General Office of the State Council China. 2021. Guo Wu Yuan Ban Gong Ting Guan Yu Wan Shan Ke Ji Cheng Guo Ping Jia Ji Zhi De Zhi Dao Yi Jian (Guideline on Improving the Research Evaluation System of Science and Technology). Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Gong, Fang, and Qu Mingfeng. 2010. Nanjing daxue ge an: SCI ying ru pingjia tixi dui zhongguo dalu jichu yanjiu de yingxiang. Higher Education of Sciences 3: 4–17.

Government of People's Republic of China. 2021. Outline of the 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development of the People's Republic of China. Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Guan, Jiancheng, and Ying He. 2005. Comparison and evaluation of domestic and international outputs in information science & technology research of China. Scientometrics 65(2): 215–244.

Hobson, John M. 2012. The Eurocentric conception of world politics: Western international theory, 1760–2010 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Hu, Qingtai. 2013. Zhong Guo Xue Shu Guo Ji Hua Yu Quan De Li Ti Hua Jian Gou (The three-dimensional construction of Chinese academic international discourse power). Academic Monthly 2013(3): 5–13.

Hu, Guangyuan, Yuhan Yang, and Li Tang. 2019. Retraction and research integrity education in China. Science & Engineering Ethics 25(1): 13–14.

Huang, Chaolin, et al. 2020. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet 395(10223): 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 .

Hvistendahl, Maha. 2013. China’s publication bazaar. Science 342(6162): 1035–1039.

IEEE. 2019. IEEE Lifts Restrictions on Editorial and Peer Review Activities. IEEE. https://www.ieee.org/about/news/2019/statement-update-ieee-lifts-restrictions-on-editorial-and-peer-review-activities.html . Accessed 2 February 2022.

ISTIC. 2020. Statistical Data of Chinese S&T Papers 2019. Beijing: ISTIC.

ISTIC. 2021. Statistical Data of Chinese S&T Papers 2020. Beijing: ISTIC.

Jia, Hepeng. 2017. Retractions pulling China back. Nature index. https://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/call-for-tougher-sanctions-in-response-to-growth-in-papers-recalled-for-misconduct . Accessed 2 February 2022.

Jiang, Zhida. 2018. Hua Yu Quan Shi Jiao Xia De She Ke Xue Shu Qi Kan Guo Ji Hua Yan Jiu (Research on the Internationalization of Academic Journals in Social Sciences from the Perspective of Discourse Power). Publishing Research 2018(1): 79–82.

Jin, Bihui, Jiangong Zhang, Dingquan Chen, and Xianyou Zhu. 2002. Development of the Chinese Scientometric Indicators (CSI). Scientometrics 54(1): 145–154.

Jin, Bihui, and Ronald Rousseau. 2004. Evaluation of research performance and scientometric indicators in China. In Handbook of quantitative science and technology research: the use of publication and patent statistics in studies of S&T systems, eds. Henk F. Moed, Wolfgang Glänzel, & Ulrich Schmoch, 497-514. Dordrecht; London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Kim, Woosang, and Scott Gates. 2015. Power transition theory and the rise of China. International Area Studies Review 18(3): 219–226.

Larivière, Vincent, Fei Shu, and Cassidy R. Sugimoto. 2020. The Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak highlights serious deficiencies in scholarly communication. LSE Impact Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2020/03/05/the-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak-highlights-serious-deficiencies-in-scholarly-communication/ . Accessed 31 January 2022.

Larivière, Vincent, and Jean-Philippe Warren. 2019. Introduction: The dissemination of national knowledge in an internationalized scientific community. Canadian Journal of Sociology 44(1): 1–8.

Lee, Jenny J., and John P. Haupt. 2021. Scientific globalism during a global crisis: Research collaboration and open access publications on COVID-19. Higher Education 81(5): 949–966.

Li, Ling. 2006. Attitudes of Chinese scientists toward open access to scientific information—a case study of scientists of the Chinese Academy of sciences. Library and Information Service 50(7): 34–38.

Li, Wei, Xia Wang, and Zeyong Feng. 2015. Dui SCI Zai Yi Yao Yuan Xiao Jiao Shi Zhi Cheng Ping Shen Zhong Zuo Yong De Si Kao (A review on the use of SCI on the tenure assessment in medical schools). Negative 7(5): 52–55.

Li, Qun, Xuhua Guan, et al. 2020. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. New England Journal of Medicine 382(13): 1199–1207. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 .

Li, Huimin. 2020. ke ji bu: Yi qing fang kong ren wu wan cheng zhi qian bu ying jiang jing li fang zai lun wen fa biao shang (MoST: We should not focus on publishing papers before the completion of the epidemic prevention and control tasks). https://finance.sina.com.cn/wm/2020-02-01/doc-iimxyqvy9564445.shtml . Accessed 31 January 2022.

Liang, Xiaojian. 2014. Wo Guo Xue Shu Qi Kan De Guo Ji Hua Yu Quan Que Shi Yu Ying Dui (The lack of international discourse power of Chinese academic journals and its countermeasures). Publishing Journal 22(6): 12.

Liang, Liming, and Wu Yishan. 2001. Selection of databases, indicators and models for evaluating research performance of Chinese universities. Research Evaluation 10: 105–114.

Liu, Cai-e. 2018. Ba Lun Wen Xie Zai Zu Guo Da Di Shang —Guo Nei Ke Yan Lun Wen Wai Liu Xian Xiang Fen Xi (Publishing papers at home - Analysis of the outflow of the domestic scientific research papers). Journal of Beijing University of Technology (Social Science Edition) 18(2): 64–72.

Liu, Jianhua, and Shuiqin Huang. 2007. User’s acceptance of open access in China: A case study. Journal of Library Science in China 33(2): 103–107.

Liu, Yanyang, Danqing Wu, Guanghao Wu, and Yongcai famg. 2003. SCI Yong Zuo Ke Yan Ping Jia Zhi Biao De Si Kao — Xue Ke Fen Bu Dui Zhi Biao Gong Zheng Xing De Ying Xiang (Review of SCI indicators on research evaluation: The impact of disciplinary distribution on indicator accuracy). Science Research Management 2003(5): 59–64.

Liu, Yan. 2020. Qiang fa ke yan lun wen yin feng bo zhong guo ke ji bu ci shi fa sheng yi zai he zhi (What is the intention of the MoST of China to speak at this time). DW News. https://www.dwnews.com/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD/60166517/%E6%AD%A6%E6%B1%89%E8%82%BA%E7%82%8E%E6%8A%A2%E5%8F%91%E7%A7%91%E7%A0%94%E8%AE%BA%E6%96%87%E5%BC%95%E9%A3%8E%E6%B3%A2%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E7%A7%91%E6%8A%80%E9%83%A8%E6%AD%A4%E6%97%B6%E5%8F%91%E5%A3%B0%E6%84%8F%E5%9C%A8%E4%BD%95%E6%8C%87 . Accessed 31 January 2022.

Lu, Cuitao. 2018. Wo Guo Ke Ji Qi Kan Guo Ji Hua Yu Quan Jian She Chu Tan (A preliminary study on the construction of international discourse power of Chinese sci-tech journals). Collections 2018: 23–28.

Mallapaty, Smriti. 2020. China bans cash rewards for publishing papers. Nature 579(7797): 18–18.

Marginson, Simon. 2021. National modernisation and global science in China. International Journal of Educational Development 84: 102407.

Merton, Robert King. 1957. Priorities in scientific discovery: A chapter in the sociology of science. American Sociological Review 22(6): 635–659.

Merton, Robert King. 1973. The sociology of science: theoretical and empirical investigations . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mervis, Jeffrey. 2019. Update: In reversal, science publisher IEEE drops ban on using Huawei scientists as reviewers. Science. https://www.science.org/content/article/update-reversal-science-publisher-ieee-drops-ban-using-huawei-scientists-reviewers . Accessed 31 January 2022.

Ministry of Education of China. 2011. Guan yu jin yi bu gai jin gao deng xue xiao zhe xue she hui ke xue yan jiu ping jia de yi jian (A guide on further improving the evaluation of philosophy and social sciences research in higher education). Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Ministry of Education of China. 2018. Guan Yu Kai Zhan Qing Li “ Wei Lun Wen, Wei Mao Zi, Wei Zhi Cheng, Wei Xue Li, Wei Jiang Xiang ” Zhuan Xiang Xing Dong De Tong Zhi (Notice of the special action of clearing up ‘only paper, only title, only diploma, and only award). Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Ministry of Education of China. 2020. Guan yu po chu gao xiao zhe xue she hui ke xue yan jiu ping jia zhong “ wei lun wen ” bu liang dao xiang de ruo gan yi jian (Several opinions on eliminating the publication-based research evaluation in social science and humanities). Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Ministry of Education of China, and Ministry of Science and Technology of China. 2020. Guan yu gui fan gao deng xue xiao SCI lun wen xiang guan zhi biao shi yong shu li zheng que ping jia dao xiang de ruo gan yi jian (On regulating the use of the number of SCI papers as well as bibliometric indicators on university research evaluation). In Ministry of Education of China, & Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Eds.). Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, and Ministry of Education of China. 2021. Guan yu shen hua gao deng xue xiao jiao shi zhi cheng zhi du gai ge de zhi dao yi jian (A guide on the reform of tenure and promotion in colleges and universities). Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Ministry of Science and Technology of China. 2020a. Guan yu jia qiang xin xing guan zhuang bing du fei yan ke ji gong guan xiang mu guan li you guan shi xiang de tong zhi (Notice on strengthening the management of new coronavirus pneumonia science and technology projects). Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Ministry of Science and Technology of China. 2020b. Guan yu po chu ke ji ping jia zhong “wei lun wen ”bu liang dao xiang de ruo gan cuo shi (On eliminating the abusive use of number of publications in research evaluation). Beijing: Government of People's Republic of China.

Moed, Henk. 2002. Measuring China’s research performance using the science citation index. Scientometrics 53(3): 281–296.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2019. China Statistical Yearbook . Beijing: China Statistics Press.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. 1996-2019. China Statistics Yearbook on Science and Technology. Beijing: National Bureau of Statistics of China.

National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. 2007. Law of the People’s Republic of China on Progress of Science and Technology. 82 . Beijing, China: President of People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China.

National Science Board. 2018. Science and Engineering Indicators 2018. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation.

Osterloh, Margit, and Bruno S. Frey. 2014. Ranking games. Evaluation Review 39(1): 102–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X14524957 .

Peng, Changhui. 2011. Focus on quality, not just quantity. Nature 475(7356): 267.

Punnoose, Sebin K., and C. Vinodan. 2019. The rise of China and power transition in contemporary international relations. IUP Journal of International Relations 13(1): 7–27.

Qi, Wang. 2017. Comment: Programmed to fulfill global ambitions. Nature 545: S53. https://doi.org/10.1038/545S53a .

Qin, Amy. 2020. Coronavirus Anger Boils Over in China and Doctors Plead for Supplies. New York Times. https://cn.nytimes.com/china/20200131/china-coronavirus-epidemic/dual/ . Accessed 31 January 2022.

Qiu, Jun-Ping, and Li Ji. 2003. Research on SCI and scientific evaluation. Science Research Management 24(4): 22–28.

Quan, Wei, Bikun Chen, and Fei Shu. 2017. Publish or impoverish: An investigation of the monetary reward system of science in China (1999–2016). Aslib Journal of Information Management 69(5): 486–502.

Quan, Wei, Philippe Mongeon, Maxime Sainte-Marie, Rongying Zhao, and Vincent Larivière. 2019. On the development of China’s leadership in international collaborations. Scientometrics 120(2): 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03111-1 .

Schiermeier, Quirin. 2018. China backs bold plan to tear down journal paywalls. Nature 564(7735): 171–173.

Shen, Zhuanghai. 2016. Shi Lun Ti Sheng Guo Ji Xue Shu Hua Yu Quan (On promoting international academic discourse power). Studies on Cultural Soft Power 2016(1): 97–105.

Shi, Yigong, and Yi Rao. 2010. China’s research culture. Science 329(5996): 1128. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1196916 .

Shu, Fei, Charles-Antoine Julien, and Vincent Larivière. 2019. Does the Web of Science accurately represent Chinese scientific performance? Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 70(10): 1138–1152. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24184 .

Shu, Fei, Wei Quan, Bikun Chen, Junping Qiu, Cassidy R. Sugimoto, and Vincent Larivière. 2020a. The role of Web of Science publications in China’s tenure system. Scientometrics 122(3): 1683–1695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03339-x .

Shu, Fei, Cassidy R. Sugimoto, and Vincent Larivière. 2020b. The institutionalized stratification of the Chinese higher education system. Quantitative Science Studies 2(1): 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00104 .

Tang, Li. 2019. Five ways China must cultivate research integrity. Nature 575: 589–591.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2018. How Much Does Your Country Invest in R&D? Montreal, Canada: UNESCO.

Wang, Bowen. 2011. Guo Ji Hua Yu Xue Shu Hua Yu Quan (Internationalization and academic discourse power). World Affairs 2011(6): 6–6.

Wang, Xiaofeng. 2012. Gao Xiao Jiao Shi Ji Xiao Kao He De Huan Jing Fen Xi Yu Lu Jing Xuan Ze (An analysis of the background and path on performance evaluation in higher education). Journal of Hunan University of Science & Technology (Social Science Edition) 15(5): 178–180.