- All Programs

- Top Activities

- Scavenger Hunts

- Indoor Team Building

- Outdoor Team Building

- Charity & Philanthropic

- Budget Activities

- Training & Development

- Coaching & Consulting

- Downloadable Resources

- Helpful Links

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Why Choose Us

- Corporate Groups

- DMC & Event Planners

- Hotel & Resorts

- School & Universities

- Charities & Non profits

- Meet Our Team

- Join Our Team

Outback Team Building & Training Blog

Tips, expert advice, exclusive interviews, and more on team building and employee engagement, 10 team building case studies & training case studies.

The key to a strong business is creating a close-knit team. Here's how 15 corporate teams did so using team building, training, and coaching solutions.

From corporate groups to remote employees and everything in between, the key to a strong business is creating a close-knit team. In this comprehensive case study, we look at how real-world organizations benefited from team building, training, and coaching programs tailored to their exact needs.

We’re big believers in the benefits of team building , training and development , and coaching and consulting programs. That’s why our passion for helping teams achieve their goals is at the core of everything we do. At Outback Team Building and Training, our brand promis e is to be recommended , flexible, and fast. Because we understand that when it comes to building a stronger and more close-knit team, there’s no one-size-fits-all formula. Each of our customers have a unique set of challenges, goals, and definitions of success. And they look to us to support them in three key ways: making their lives easy by taking on the complexities of organizing a team building or training event; acting fast so that they can get their event planned and refocus on all the other tasks they have on their plates; and giving them the confidence that they’ll get an event their team will benefit from – and enjoy. In this definitive case study, we’ll do a deep dive into:

- 3 Unique Events Custom-Tailored for Customer Needs

- 3 Momentum-Driving Events for Legacy Customers

- 4 Successful Activities Executed on Extremely Tight Timelines

Unique Events Custom-Tailored for Customer Needs We know that every team has different needs and goals which is why we are adept at being flexible and have mastered the craft of creating custom events for any specifications

When the Seattle, Washington -based head office of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation – a world-renowned philanthropic organization – approached us in search of a unique charity event, we knew we needed to deliver something epic. Understanding that their team h ad effectively done it all when it comes to charity events, it was important for them to be able to get together as a team and give back in new ways .

Our team decided the best way to do this was to creat e a brand-new event for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation which had never been executed before. We created an entirely new charitable event – Bookworm Builders – for them and their team loved it! It allowed them to give back to their community, collaborate, get creative, and work together for a common goal. Bookworm Builders has since gone on to become a staple activity for tons of other Outback Team Building and Training customers!

To learn more about how it all came together, read the case study: A Custom Charity Event for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation .

Who said hosting an impactful training program means having your full team in the same place at the same time? Principia refused to let distance prevent them from having a great team, so they contacted us to help them find a solution. Their goals were to find better ways of working together and to create a closer-knit company culture among their 20 employees and contractors living in various parts of the country.

We worked with Principia to host an Emotional Intelligence skill development training event customized to work perfectly for their remote team. The result was a massive positive impact for the company. They found they experienced improved employee alignment with a focus on company culture, as well as more emotionally aware and positive day-to-day interactions. In fact, the team made a 100% unanimous decision to bring back Outback for additional training sessions.

To learn more about this unique situation, read the full case study: How Principia Built a Stronger Company Culture Even with its Remote Employees Working Hundreds of Miles Apart .

W e know that employee training which is tailored to your organization can make the difference between an effective program and a waste of company time. That’s why our team jumped at the opportunity to facilitate a series of custom development sessions to help the Royal Canadian Mint discover the tools they needed to manage a large change within their organization.

We hosted three custom sessions to help the organization recognize the changes that needed to be made, gain the necessary skills to effectively manage the change, and define a strategy to implement the change:

- Session One: The first session was held in November and focused on preparing over 65 employees for change within the company.

- Session Two: In December, the Mint’s leadership team participated in a program that provided the skills and mindset required to lead employees through change.

- Session Three: The final session in February provided another group of 65 employees with guidance on how to implement the change.

To learn more, read the full case study: Custom Change Management Program for the Royal Canadian Mint .

3 Momentum-Driving Events for Legacy Customers We take pride in being recommended by more than 14,000 corporate groups because it means that we’ve earned their trust through delivering impactful results

1. How a Satellite Employee “Garnered the Reputation” as Her Team’s Pro Event Planner

We’ve been in this business for a long time, and we know that not everybody who’s planning a corporate event is a professional event planner. But no matter if it’s their first time planning an event or their tenth, we love to help make our customers look good in front of their team. And when an employee at Satellite Healthcare was tasked with planning a team building event for 15 of her colleagues, she reached out to us – and we set out to do just that!

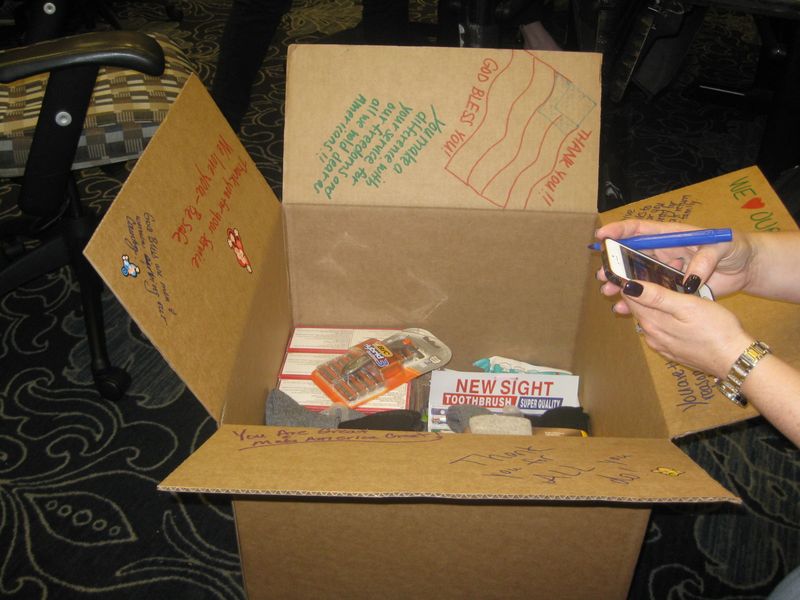

Our customer needed a collaborative activity that would help a diverse group of participants get to know each other, take her little to no time to plan, and would resonate with the entire group.

With that in mind, we helped her facilitate a Military Support Mission . The event was a huge success and her colleagues loved it. In fact, she has now garnered the reputation as the team member who knows how to put together an awesome team building event.

To learn more, read the case study here: How a Satellite Employee “Garnered the Reputation” as Her Team’s Pro Event Planner .

2. Why PlentyOfFish Continues to Choose ‘The Amazing Race’ for Their Company Retreat

In 2013, international dating service POF (formerly known as PlentyOfFish ) reached out to us in search of an exciting outdoor team building activity that they could easily put to work at their annual retreat in Whistler, B.C . An innovative and creative company, they were in search of an activity that could help their 60 staff get to know each other better. They also wanted the event to be hosted so that they could sit back and enjoy the fun.

The solution? We helped them host their first-ever Amazing Race team building event.

Our event was so successful that POF has now hosted The Amazing Race at their annual retreat for five consecutive years .

To learn more, check out our full case study: Why PlentyOfFish Continues to Choose ‘The Amazing Race’ for Their Company Retreat .

3. How Team Building Helped Microsoft Employees Donate a Truckload of Food

As one of our longest-standing and most frequent collaborators, we know that Microsoft is always in search of new and innovative ways to bring their teams closer together. With a well-known reputation for being avid advocates of corporate social responsibility, Microsoft challenged us with putting together a charitable team building activity that would help their team bond outside the office and would be equal parts fun, interactive, and philanthropic.

We analyzed which of our six charitable team building activities would be the best fit for their needs , and we landed on the perfect one : End-Hunger Games . In this event, the Microsoft team broke out into small groups, tackled challenges like relay races and target practice, and earned points in the form of non-perishable food items. Then, they used their cans and boxes of food to try and build the most impressive structure possible in a final, collaborative contest. As a result, they were able to donate a truckload of goods to the local food bank.

For more details, check out the comprehensive case study: How Team Building Helped Microsoft Employees Donate a Truckload of Food .

4 Successful Activities Executed on Extremely Tight Timelines Time isn’t always a luxury that’s available to our customers when it comes to plan ning a great team activity which is why we make sure we are fast, agile, and can accommodate any timeline

Nothing dampens your enjoyment of a holiday more than having to worry about work – even if it’s something fun like a team building event. But for one T-Mobile employee, this was shaping up to be the case. That’s because , on the day before the holiday weekend, she found out that she needed to organize a last-minute activity for the day after July Fourth.

So, she reached out to Outback Team Building and Training to see if there was anything we could do to help - in less than three business days . We were happy to be able to help offer her some peace of mind over her holiday weekend by recommending a quick and easy solution: a Code Break team building activity. It was ready to go in less than three days, the activity organized was stress-free during her Fourth of July weekend, and, most importantly, all employees had a great experience.

For more details, check out the full story here: Finding a Last-Minute Activity Over a Holiday .

At Outback Team Building and Training, we know our customers don’t always have time on their side when it comes to planning and executing an event. Sometimes, they need answers right away so they can get to work on creating an unforgettable experience for their colleagues.

This was exactly the case when Black & McDonald approached us about a learning and development session that would meet the needs of their unique group, and not take too much time to plan. At 10:20 a.m., the organization reached out with an online inquiry. By 10:50 a.m., they had been connected with one of our training facilitators for a more in-depth conversation regarding their objectives.

Three weeks later, a group of 14 Toronto, Ontario -based Black & McDonald employees took part in a half-day tailor-made training program that was built around the objectives of the group, including topics such as emotional intelligence and influence, communication styles, and the value of vulnerability in a leader.

To learn more about how this event was able to come together so quickly, check out the full story: From Inquiry to Custom Call in Under 30 Minutes .

When Conexus Credit Union contacted us on a Friday afternoon asking if we could facilitate a team building event for six employees the following Monday morning, we said, “Absolutely!”

The team at Conexus Credit Union were looking for an activity that would get the group’s mind going and promote collaboration between colleagues. And we knew just what to recommend: Code Break Express – an activity filled with brainteasers, puzzles, and riddles designed to test the group’s mental strength.

The Express version of Code Break was ideal for Conexus Credit Union’s shorter time frame because our Express activities have fewer challenges and can be completed in an hour or less. They’re self-hosted, so the company’s group organizer was able to easily and efficiently run the activity on their own.

To learn more about how we were able to come together and make this awesome event happen, take a look at our case study: A Perfect Group Activity Organized in One Business Day .

We’ve been lucky enough to work with Accenture – a company which has appeared on FORTUNE’s list of “World’s Most Admired Companies” for 14 years in a row – on a number of team building activities in the past.

T he organization approached us with a request to facilitate a philanthropic team building activity for 15 employees . The hitch? They needed the event to be planned, organized, and executed within one week.

Staying true to our brand promise of being fast to act on behalf of our customers, our team got to work planning Accenture’s event . We immediately put to work the experience of our Employee Engagement Consultants , the flexibility of our solutions, and the organization of our event coordinators. And six days later, Accenture’s group was hard at work on a Charity Bike Buildathon , building bikes for kids in need.

To learn more about how we helped Accenture do some good in a short amount of time, read the full case study: Delivering Team Building for Charity in Under One Week .

Learn More About Team Building, Training and Development, and Coaching and Consulting Solutions

For more information about how Outback Team Building and Training can help you host unforgettable team activities to meet your specific goals and needs on virtually any time frame and budget, just reach out to our Employee Engagement Consultants.

Subscribe to Our Blog

- Team Building (104)

- Employee Engagement (42)

- Training & Development (29)

- Case Studies (23)

- Podcast (23)

- Online Guides (22)

- Leadership Training (21)

- Charity Team Building (17)

- Employee Training (13)

- Team Consulting (12)

- Featured Events (11)

- Core Values (8)

- Experiential Learning (8)

- Team Coaching (8)

- Meetings (7)

- Outback Team Building & Training (7)

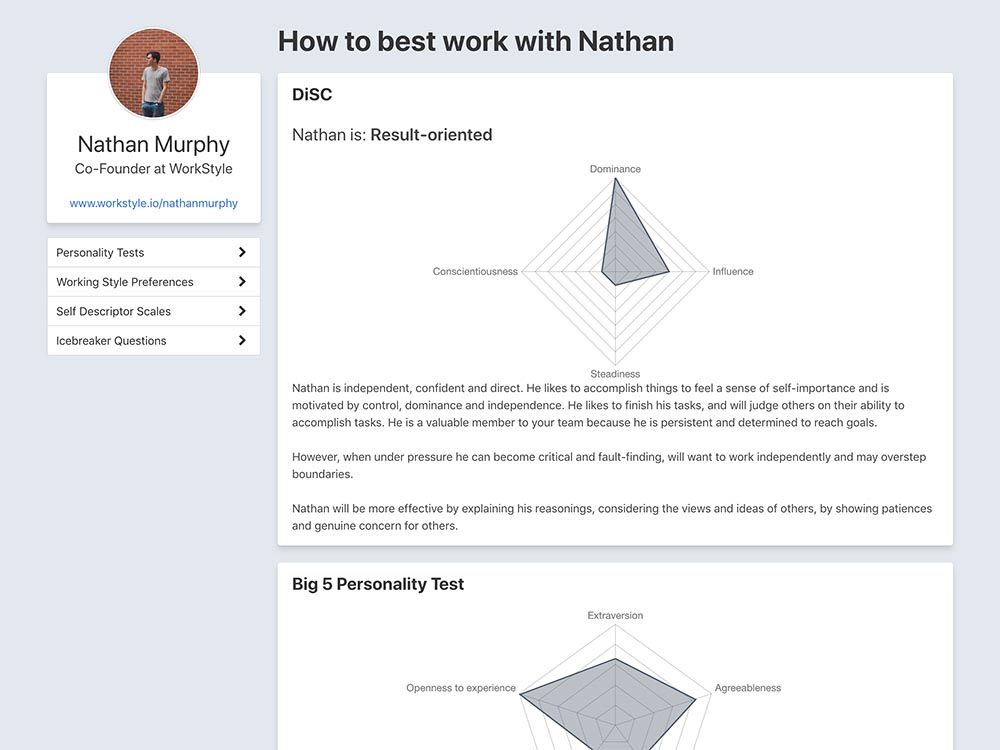

- D.I.S.C. (6)

- HR Resources (6)

- Company Retreats (5)

- Meet the Team (4)

- Charity Event (3)

- Recruitment (3)

- Indoor Team Building (2)

- event planning (2)

- "Outdoor Team Building" (1)

- Icebreakers (1)

- Outback Cares (1)

- Ropes Courses (1)

- March 2020 (3)

- February 2020 (9)

- January 2020 (10)

- December 2019 (5)

- November 2019 (7)

- October 2019 (9)

- September 2019 (5)

- August 2019 (3)

- July 2019 (11)

- June 2019 (6)

- May 2019 (10)

- April 2019 (4)

- March 2019 (4)

- February 2019 (5)

- January 2019 (7)

- December 2018 (5)

- November 2018 (10)

- October 2018 (6)

- September 2018 (6)

- August 2018 (6)

- July 2018 (7)

- June 2018 (6)

- May 2018 (7)

- April 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (2)

- February 2018 (2)

- January 2018 (5)

- November 2017 (2)

- October 2017 (5)

- September 2017 (3)

- August 2017 (6)

- July 2017 (4)

- June 2017 (5)

- May 2017 (3)

- April 2017 (4)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (2)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (3)

- August 2016 (2)

- July 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (2)

- April 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (4)

- January 2016 (2)

- November 2015 (2)

- October 2015 (1)

- September 2015 (1)

- August 2015 (1)

- More Team Building

- More Training & Development

- More Coaching & Consulting

Latest News

Additional links.

- Team Building In Your City

- Reasons to Choose Us

- Site Selector: USA | Canada

Proud Members of

© 2018 Outback Team Building & Training, All Rights Reserved. | Site Map | Privacy Policy

- Culture

4 Team Building Experiences to Create a Harmonizing Team

Team building experience helps organizations create a positive company culture, align employees with shared values, and improve communication among employees.

Table of Contents

A report suggests that the number of companies investing in virtual team building has risen by 2,500, and why wouldn't it? A Gallup study has reported that an engaged team can show immense productivity and record a 23% in profitability showcasing the need to invest in generating team building experience. Take the Bills and Gates Melinda Organization for example.

They aim to enhance the well-being of billions of people globally and they achieve this by supporting initiatives in healthcare, education, and poverty reduction.

So, as a philanthropic organization, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has a long history of charitable and philanthropic work. Therefore, to come up with a unique team building experience that resonates with the employees in a meaningful way, they collaborated with Outback.

They quickly came up with an activity called 'the Bookworm Builders' for this event. There were small teams of two or three, and the group members collaboratively constructed bookshelves for underprivileged children. Each team designed and built a unique shelf, which was then donated by the organization to Treehouse, a local non-profit dedicated to supporting the education of foster youth.

This initiative provided a valuable opportunity for each team to work together, express their creativity, and contribute to the educational development of local children in a meaningful way. This small event helped them collaborate, communicate, and be understanding of each other.

With the Gallup research showing that “concentrating on employee engagement can help companies withstand, and possibly even thrive, in tough economic times,” it is important to create an engaging team-building experience. This article will explain different types of team building experiences, how to create a good one, and more for your better understanding.

What is a team building experience?

A team building experience is a planned activity or program that helps a group of colleagues work together more effectively. These activities can involve games, challenges, or discussions designed to improve communication, trust, and problem-solving skills among team members.

Team building experiences play a valuable role in shaping a positive corporate culture. When elicited rightly, these activities provide opportunities for employees to,

- Collaborate outside the pressures of everyday work.

- Fosters better communication, trust, and understanding among colleagues.

- Improve their problem-solving skills and develop a stronger sense of camaraderie.

Ultimately, these positive team dynamics contribute to a more productive and enjoyable work environment for everyone.

What are the different types of team-building experiences?

Team-building experiences can take a variety of formats to enhance collaboration and communication within a group. These include:

- Outdoor activities : Engaging in physical activities outside the workplace fosters teamwork in a new environment.

- Indoor challenges : Problem-solving exercises conducted indoors can encourage creative thinking and communication within a team.

- Workshops and seminars: Educational sessions focused on teamwork and communication skills can provide valuable knowledge and tools.

- Volunteering and community service: Working together for a charitable cause can build camaraderie and social responsibility within a team.

- Team Retreats: Spending dedicated time away from the usual work environment allows teams to focus on collaboration and team development.

How to create a team-building experience?

Effective teamwork is essential for any organization's success. Following is how you can create a successful team-building experience:

1. Identify your objectives

Begin by defining the desired outcome of the team-building activity. Are you aiming to improve communication? Strengthen problem-solving skills? Or perhaps boost overall team morale? A clearly defined objective will guide your selection of activities and ensure the experience is focused and productive.

2. Know your team

Consider the size, personalities, and interests of your team members. This will help you choose an activity that is both engaging and accessible to everyone. For instance, an introverted team might benefit more from a collaborative problem-solving challenge, while an extroverted group might enjoy a high-energy activity that encourages active participation.

3. Plan the timeline

Determine the timeframe for the team-building experience. Will it be a short activity integrated into a regular meeting, a dedicated half-day event to allow for in-depth exploration or a multi-day retreat for a more immersive experience? The ideal timeframe depends on your goals and your team's availability.

4. Select the best activity

Choose an activity that aligns with your goals and is suitable for your team. There are numerous options available, from creative brainstorming sessions to strategic escape rooms or collaborative games. Consider activities that encourage interaction and communication, while also providing opportunities for team members to discover and utilize each other's strengths.

5. Align with team values

Ensure the chosen activity reflects the team's core values and fosters a sense of shared purpose. For example, if your team prioritizes innovation, consider a design thinking challenge. A team focused on client satisfaction might benefit from a role-playing exercise that simulates client interactions. Aligning the activity with team values reinforces these values and strengthens the team's identity.

6. Promote inclusivity

Make sure everyone feels comfortable participating, regardless of background or skill level. Offer options for different abilities and encourage open communication. This might involve providing clear instructions, breaking down complex tasks into smaller steps, or offering alternative ways to contribute. An inclusive environment ensures everyone feels valued and fosters a stronger sense of team spirit.

7. Reflection is key

After the activity, hold a discussion to reflect on the experience. What were the key takeaways? How can these learnings be applied to future teamwork? Encourage honest feedback and open discussion to solidify the learnings and translate them into actionable steps for improved collaboration within the team. By reflecting on the experience, you can ensure that the team-building activity has a lasting positive impact.

What are a few team-building experience ideas?

Some effective team-building experience ideas include:

1. Volunteer activity: Organize an opportunity for team members to work together for a social cause. This will build camaraderie and a sense of shared purpose.

2. Collaborative scavenger hunt: Plan a scavenger hunt that requires teamwork and problem-solving skills. This will encourage communication and collaboration among team members.

3. Professional development workshops: Host workshops or seminars on skill development, industry trends, or leadership. These sessions will allow team members to learn from each other and build relationships.

4. Group sporting event : Organize a sporting event or activity for the team, such as a tournament or a casual game. This can help to break the ice and promote bonding among team members.

Case studies

Following are the two case studies to showcase the significance of generating team building experience.

1. Amazon organize a thrilling scavenger hunt for 30 employees in Milan for enhanced employee engagement

Amazon needs no introduction, and its approach to establishing employee engagement has always remained unique. Amazon recently was planning a conference in Milan and desired a "fun Scavenger Hunt" for their 30 employees.

Since these employees didn't frequently work together, the goal was to create a team-building activity that would encourage exploration of the new city. Meanwhile, they wanted to foster camaraderie and connections within the group. Considering budget constraints for the conference's social events, a cost-effective solution was also a key factor. So, they collaborated with Wildgoose.

Wildgoose proposed a perfect team-building activity for Amazon in Milan. They designed a Self-Managed Milan City Explorer Challenge; a high-tech scavenger hunts accessible through a mobile app on attendees' smartphones.

The content creators at Wildgoose crafted unique challenges around Milan's history, culture, and landmarks. Teams navigated the city centre using the app, encountering trivia questions, photo opportunities, and interactions with locals.

This activity fostered team bonding while allowing participants to experience the beauty of Milan. The teams used the app to form groups, download the software, and access the challenges. A live map guided them throughout the city. An event manager monitored the activity online, scoring photos and videos, and keeping teams engaged.

Nearing the end, the manager prompted teams to return to a designated finish point. A countdown timer added excitement as teams raced to complete final challenges. Afterward, the client received links to a photo/video presentation and final scores to celebrate the winning team.

Clients thoroughly enjoyed exploring the city through our engaging and interactive team challenge. The user-friendly app, accessible on personal devices, allowed Wildgoose to offer a flexible and cost-effective solution that maintained high attendee participation. Furthermore, the remote support team ensured the client's confidence and provided the necessary guidance for a smooth, self-managed experience.

2. Deloitte holds exceptional team building experience to encourage a shared sense of community

Deloitte , a multinational professional services network wanted to hold a thrilling event. They aimed to create a fun and engaging experience for all 140 employees, including a significant number of recent additions to their team. The ideal event would encourage participation from everyone and provide a refreshing change of scenery by taking place outside of the office environment.

Deloitte sought The Big Smoke's assistance in planning a celebratory event for their summer party. The scavenger hunt proved to be the ideal solution for Deloitte's summer celebration. The Big Smoke designed a personalized hunt featuring challenging cryptic clues, puzzles tailored to their company, and activities that resulted in humorous video footage. This experience served as the perfect way to initiate their summer festivities.

This event provided a fun and engaging experience that fostered creativity and teamwork. More importantly, it allowed colleagues who may not have had prior opportunities for social interaction, gel properly with each other. It successfully removed participants from their usual work environment and encouraged collaboration, laughter, and a shared sense of enjoyment.

Conclusion

Team building experiences significantly contribute to employee engagement as it helps foster a sense of friendship, trust, and collaboration among coworkers. These activities help employees develop stronger relationships, which in turn leads to improved communication, problem-solving, and overall job satisfaction. However, to maximize the experience, try implementing Empuls . It helps organizations create a positive company culture, align employees with shared values, and drive multiple people initiatives from a single platform by:

- Running employee engagement surveys . Analyze engagement metrics and identify areas for improvement after each team-building experience.

- Running employee satisfaction and loyalty survey, namely the Pulse survey , by analyzing employee behavior and providing real-time actionable insights to improve company culture.

- Allowing for open communication and collaboration through one-on-one feedback and peer recognition.

Enable continuous feedback and improvement throughout the employee lifecycle through real-time surveys, allow peer-to-peer recognition, and drive multiple people initiatives from Empuls.

Employee Reward Program: 5 Unique Ideas with Examples to Breed Engagement & Satisfaction

14 team building ideas in a budget to strengthen team unity, learn to build and sustain a culture that connects, engages, and motivates your people..

-->Nagma Nasim -->

Nagma is a content writer who creates informative articles, blogs & other engaging content. In her free time, you can find her immersed in academic papers, novels, or movie marathons.

Make culture your biggest competitive advantage!

Cultivate your company culture through continuous feedback, connection, and motivation.

Let's begin this new year with an engaged workforce!

Empuls is the employee engagement platform for small and mid-sized businesses to help engage employees and improve company culture.

Quick Links

employee engagement survey software | employee engagement software | employee experience platform | employee recognition software

hr retention software | employee feedback software | employee benefits software | employee survey software | employee rewards platform | internal communication software | employee communication software | reward system for employees | employee retention software | digital employee experience platform | employee health software | employee perks platform | employee rewards and recognition platform | social intranet software | workforce communications platform | company culture software | employee collaboration software | employee appreciation software | social recognition platform | virtual employee engagement platform | peer recognition software | retail employee engagement | employee communication and engagement platform | gamification software for employee engagement | corporate communication software | digital tools for employee engagement | employee satisfaction survey software | all in one communication platform | employee benefits communication software | employee discount platform | employee engagement assessment tool | employee engagement software for aged care | employee engagement software for event management | employee engagement software for healthcare | employee engagement software for small business | employee engagement software uk | employee incentive platform | employee recognition software for global companies | global employee rewards software | internal communication software for business | online employee recognition platform | remote employee engagement software | workforce engagement software | voluntary benefits software | employee engagement software for hospitality | employee engagement software for logistics | employee engagement software for manufacturing | employee feedback survey software | employee internal communication platform | employee learning engagement platform | employee awards platform | employee communication software for hospitality | employee communication software for leisure | employee communication software for retail | employee engagement pulse survey software | employee experience software for aged care | employee experience software for child care | employee experience software for healthcare | employee experience software for logistics | employee experience software for manufacturing | employee experience software for mining | employee experience software for retail | employee experience software for transportation | restaurant employee communication software | employee payout platform | culture analytics platform

Benefits of employee rewards | Freelancer rewards | Me time | Experience rewards

Employee experience platform | Rules of employee engagement | Pillars of employee experience | Why is employee experience important | Employee communication | Pillars of effective communication in the work place | Build strong employee loyalty

Building Culture Garden | Redefining the Intranet for Your Organization | Employee Perks and Discounts Guide

Employee Benefits | Getting Employee Recognition Right | Integrates with Slack | Interpreting Empuls Engagement Survey Dashboard | Building Culture of Feedback | Remote Working Guide 2021 | Engagement Survey Guide for Work Environment Hygiene Factors | Integrates with Microsoft Teams | Engagement Survey Guide for Organizational Relationships and Culture | Ultimate Guide to Employee Engagement | The Employee Experience Revolution | Xoxoday Empuls: The Employee Engagement Solution for Global Teams | Employee Experience Revolution | Elastic Digital Workplace | Engagement Survey Guide for Employee Recognition and Career Growth | Engagement Survey Guide for Organizational Strategic Connect | The Only Remote Working Guide You'll Need in 2021 | Employee Experience Guide | Effective Communication | Working in the Times of COVID-19 | Implementing Reward Recognition Program | Recognition-Rich Culture | Remote Working Guide | Ultimate Guide to Workplace Surveys | HR Digital Transformation | Guide to Managing Team | Connect with Employees

Total Rewards | Employee Background Verification | Quit Quitting | Job Description | Employee of the Month Award

Extrinsic Rewards | 360-Degree Feedback | Employee Self-Service | Cost to Company (CTC) | Peer-to-Peer Recognition | Tangible Rewards | Team Building | Floating Holiday | Employee Surveys | Employee Wellbeing | Employee Lifecycle | Social Security Wages | Employee Grievance | Salaried Employee | Performance Improvement Plan | Baby Boomers | Human Resources | Work-Life Balance | Compensation and Benefits | Employee Satisfaction | Service Awards | Gross-Up | Workplace Communication | Hiring Freeze | Employee Recognition | Positive Work Environment | Performance Management | Organizational Culture | Employee Turnover | Employee Feedback | Loud Quitting | Employee Onboarding | Informal Communication | Intrinsic Rewards | Talent Acquisition | Employer Branding | Employee Orientation | Social Intranet | Disgruntled Employee | Seasonal Employment | Employee Discounts | Employee Burnout | Employee Empowerment | Paid Holiday | Employee Retention | Employee Branding | Payroll | Employee Appraisal | Exit Interview | Millennials | Staff Appraisal | Retro-Pay | Organizational Development | Restricted Holidays | Talent Management Process | Hourly Employee | Monetary Rewards | Employee Training Program | Employee Termination | Employee Strength | Milestone Awards | Induction | Performance Review | Contingent Worker | Layoffs | Job Enlargement | Employee Referral Rewards | Compensatory Off | Performance Evaluation | Employee Assistance Programs | Garden Leave | Resignation Letter | Human Resource Law | Resignation Acceptance Letter | Spot Awards | Generation X | SMART Goals | Employee Perks | Generation Y | Generation Z | Employee Training Development | Non-Monetary Rewards | Biweekly Pay | Employee Appreciation | Variable Compensation | Minimum Wage | Remuneration | Performance-Based Rewards | Hourly to Yearly | Employee Rewards | Paid Time Off | Recruitment | Relieving Letter | People Analytics | Employee Experience | Employee Retention | Employee Satisfaction | Employee Turnover | Intrinsic Rewards | People Analytics | Employee Feedback | Employee of the Month Award | Extrinsic Rewards | Employee Surveys | Employee Experience | Total Rewards | Performance-Based Rewards | Employee Referral Rewards | Employee Lifecycle | Social Intranet | Tangible Rewards | Service Awards | Milestone Awards | Peer-to-Peer Recognition | Employee Turnover

- Testimonials

- Our Client List

Effective Team Building Case Studies & Insights

Written by Lisa Lawrence

Game show themes, april 20, 2024.

If you think team building is just a corporate icebreaker, think again. Nearly 75% of employers say teamwork and collaboration are vital.

However, only 18% of staff are evaluated on communication during reviews. This gap highlights a big chance to better team building in companies.

As a Team Building Facilitator on workplace culture, I’ve seen how team building case studies can change how a team works.

Indeed, stories of team building success often begin by highlighting the need for trust and good communication. This is especially true when teams shift from working remotely to being in the office.

But what about real outcomes? Are these efforts making a real difference? That’s what results from team building activities want to show us.

By looking at real examples, their wins, and the planning behind them, companies can use these powerful approaches. They can improve how their teams talk, work together, and get things done.

holiday-team-building-activities

Key Takeaways

- The importance of team building is underscored by the gap between employer expectations and employee evaluations.

- In-depth team building case studies demonstrate the transformative potential of well-engineered team building activities.

- Corporate team building success stories often emphasize the role of trust and truthful communication in a cohesive workplace culture.

- Quantifying team building activities results is crucial for understanding their true impact on an organization’s performance.

- Strategic insights from case studies can guide companies in creating more effective team building experiences.

- Focusing on these insights helps businesses transition smoothly from virtual to physical workspaces while maintaining team integrity.

The Link Between Truth-Telling and Trust in Team Building

Teams today often switch between meeting in person and working online. This makes a trustworthy atmosphere more important than ever. Gossip and backbiting can hurt team performance.

This is especially true after working from home. Understanding how truth-telling and trust work together is key for team success.

The Problem: Gossip and Backbiting in Post-Remote Work Environments

Returning to shared workspaces can bring back workplace negativity, like gossip. In these times, clear communication is crucial. Gossip can damage the process of building a strong team .

The Trust Model: A Foundation for Effective Team Building

On the other hand, truth-telling is vital for building a good team. Leaders who are open and honest create a culture of trust. This trust is crucial for the team to work well together.

Companies that embrace honesty see great teamwork and success.

Truth-telling in the workplace is not just a moral imperative but a strategic one that has a profound effect on team alignment and overall business health. – Based on corporate leadership observations

The table below shows how trust can make teams work better:

Embracing the values of the trust model can change workplace culture. This shift is crucial for the long-term success of any team.

Exploring Self-Awareness in Leadership Development Programs

As I explore self-awareness in leadership development programs , I see its huge impact. It’s more than just looking inward; it opens the door to better team interactions.

In essence, it strengthens team building case studies for companies . It’s amazing to see how personal insight and team work together, boosting performance.

>>>> Click here for fun team building games to boost morale.

Leaders who focus on self-awareness make their teams stronger and more united. They handle tough situations better, thanks to empathy and smart planning.

I have found evidence showing the big difference self-aware leaders make. Here’s a brief overview:

Being self-aware is crucial not just for personal growth. It helps leaders create a positive team environment. This makes team members feel important and understood.

In studying leadership development programs , I stress this point: teaching leaders to know themselves benefits the whole organization. It leads to big achievements and success stories.

Assessing Team Building Outcomes with Case Studies for Companies

In my study of team building’s impact, I looked at different kinds. I found many cases showing team building’s big benefits for groups. These examples highlight how well-planned team activities can boost teamwork and spark innovation.

Teaming Strategies in Large Corporations

Big companies like Google and Amazon have shared their experiences. They’ve used team building to improve their complex systems. They aim to overcome department barriers and increase communication across different teams.

Their efforts enhanced teamwork and raised productivity. This gave them an edge in their markets.

Case Studies: Family Firms and Start-Up Dynamics

Family businesses and startups may be smaller but face big challenges. Studies on team building in these setups show it’s very useful. They use specific team activities to connect generations and unite everyone’s goals.

This leads to a smoother and more flexible way of working.

These examples prove investing in team building is essential. It drives long-term success and keeps employees committed.

Dissecting the Five Stages of Team Development

Exploring team evolution reveals the value of the five-stage model. It guides a group from individuals to a united force. This journey is key to facing corporate challenges together.

Case Study: The Storming Phase in Action

The storming phase is crucial in team development . Facing conflicts here promotes open communication. It helps in crafting team building success stories by aligning individual strengths towards a common goal.

Success Stories and Pitfalls

After storming, successful teams reach the norming stage. They set rules and move smoothly into performing. Here, effective team building activities highlight their worth in achieving project success.

Team building success stories always highlight the structured development’s importance. They offer valuable lessons to organizations. These insights help build teams that exceed business goals.

Addressing Inter-Team Conflict with Proven Team Building Activities

In my search to solve inter-team conflict, I’ve learned something important. Team building activities are key to keeping teams together. Such activities help set the right standards and improve how we talk within the group.

The Importance of Normative Behavior for Team Cohesion

Following set behaviors is crucial for a good team vibe. For instance, in our team-building efforts, we emphasize behaviors that match our company values. This guides everyone towards working better together, reducing tension.

Insights into Communication Styles and Conflict Resolution

Team-building exercises are great for checking out different ways to talk to each other. They teach us to chat better and fix disagreements in a peaceful way. It’s the small changes in how we communicate that help a team go from okay to great.

- Workshop on Active Listening – Helps us grasp the value of listening well in a team.

- Role-playing Scenarios – Lets members try out fixing conflicts in a safe space.

- Feedback Circles – Makes us more open and honest in sharing thoughts, improving how we solve problems together.

Let’s look at two examples where these approaches made a big difference:

The workshops and training discussed show how carefully chosen team building can build trust and efficiency. It’s all about picking the right activities to match the team’s needs.

The Role of Transformation in Team Building

Transformation in teams is vital for organizations to succeed in changing markets. My research highlights the crucial role of team building impact analysis in understanding transformation.

It shows how teams can reach their full potential through team building activities results .

Teams that partake in structured team building become more adaptable and resilient. This adaptability is essential in today’s fast-paced work environment.

Adapting to Rapid Change: A Case Study

A tech firm once faced a huge industry shift. By analyzing team building impact, they pinpointed innovation blocks. Strategic team building activities then led to major improvements.

These actions revolutionized the company’s adaptability. It showed how transformation and team dynamics are key for survival and growth.

Surviving and Thriving through Team Transformation

Survival alone isn’t enough for teams. They must also flourish in times of change. Teams need to transform, becoming stronger and more united.

This change isn’t solely for survival. It’s for gaining a competitive advantage. Team building activities are crucial in this transformation journey.

> Click here for fun team building games to boost morale.

In summary, combining team building analysis with real transformation stories shows the importance of adaptability.

The tech firm’s story proves that welcoming change leads to organizational success. Right team building activities turn challenges into opportunities for growth.

Creating Effective Team Building Experiences Across Global Corporations

I work to improve team dynamics in global companies. I’ve learned that cultural differences matter in team building. It’s tough to bring teams together from different parts of the world. They must understand how culture affects communication and teamwork.

Cultural Considerations in Team Dynamics

I’ve looked at many team building cases. It’s clear we must consider each team’s culture. This means more than just language. We must respect social norms and business practices that vary globally. This respect is key to inclusivity and success.

Global Team Building Success: Diverse Approaches and Outcomes

Looking at case studies shows no single way to build a team. Tailoring activities to the team’s diverse needs boosts creativity and team spirit. Mixing social events with business tasks helps create strong bonds.

The key to global team building is valuing each person’s unique input. Building activities that embrace diversity drives innovation. It helps companies stay ahead in the world.

Tailored Team Building for Specific Challenges and Opportunities

Identifying a company’s unique needs and crafting special team building plans is key. It’s amazing how focusing on specific challenges changes team dynamics. This leads to great project results.

Case Example: Overcoming Interdepartmental Silos

Looking at case studies of companies overcoming interdepartmental barriers is enlightening. One effective approach involved cross-training sessions .

These sessions let employees learn about their colleagues’ roles in other departments.

Understanding each other’s work brought employees closer. It created a feeling of unity and shared goals.

Strategies for High-Stakes Project Teams

High-stakes projects need exactness, hard work, and everyone working smoothly together. Including team building activities throughout the project helps improve efficiency. Meeting tight deadlines becomes easier without sacrificing quality.

For example, team retreats with workshops on communication and stress relief boost team performance under stress. I’ve seen these retreats make a big difference in how a team handles pressure.

In my work with various industries, I’ve seen first-hand how these approaches bring strong benefits. Proactively using these strategies significantly boosts team dynamics and project success.

Truly, grasping the unique challenges of a team is crucial for effective team building.

Benefits of Team Building in Organizations Based on Research

My research into team building shows it’s very valuable for companies. These activities boost teamwork and make the workplace better.

Wondering if these efforts matter? Many studies show they do. They lead to:

- Improved Communication: Post-team building, employees often report clearer and more open lines of dialogue with their peers.

- Enhanced Productivity: A strong team is like a well-oiled machine—coordinated efforts often result in greater output and efficiency.

- Better Employee Morale: When staff feel connected and valued, their satisfaction and enthusiasm for work soar.

Team building starts a cycle of improvements. Better morale boosts productivity. In turn, this improves how teams communicate. It’s a cycle that starts with team building.

Team building isn’t just for the moment. It brings long-term changes to a company’s culture. Leaders say it’s key for success.

Here are some stats to show it. I’ve looked at studies to see the real effects of team building.

All the evidence shows team building works. It leads to a stronger, more innovative workplace. This sets a company up for success.

Team Building Case Studies

In the world of corporate growth, I’ve seen a key fact. The real proof of successful team building is in the details of team building activities results . Studying team building impact analysis teaches us a lot.

It’s not just about reaching a goal but how the team changes along the way.

At first glance, team building’s effects may seem hard to measure. But, looking closer at case studies shows us numbers and facts.

A comparative table below shows how different team building activities have helped organizations. It links the activities directly with their results.

The difference between short-term effects and long-term gains shows why team building impact analysis is vital. It ensures that team unity lasts long in a company’s culture .

I’ve seen how well-planned team building can change the work environment. It transforms competitive individuals into team players who trust and depend on each other.

When we talk about team building activities results , let’s think about not just now but the future.

After all, isn’t that the goal of a great team effort?

Verbal communication

Leveraging Insights Tool for Enhanced Team Effectiveness

In my work with team building, the Insights tool has been a game-changer. It helps uncover what teams like and the challenges they face.

What’s great about the Insights tool is its ability to show teams how they work together. This helps them make better decisions for success.

Case Study: Discovering Team Preferences and Blockers

A tech company had trouble with its developers and sales teams communicating. They used the Insights tool and saw they had different ways of talking.

The sales people were fast-paced, while the developers were more detailed. Knowing this, the company started workshops to help both teams understand each other better.

Improving Performance Through Team Preferences Alignment

Another story is about a consumer goods company facing low morale. The Insights tool showed a big difference between what the team liked and the company’s culture.

The leaders changed the workspaces and schedules to match the team’s preferences better. This made employees happier and more likely to stay.

After making changes from what they learned from the Insights tool, the consumer goods company saw a 25% increase in how well the teams did and fewer employees left.

This shows how important it is to match work with personal preferences for success.

These examples show how useful tools like Insights are in solving team issues. By really understanding what each team needs, companies can overcome problems. This leads to better results for teams in all kinds of work.

Innovative Team Building Activities That Work

In my experience, innovative team building exercises improve team connections. They add a fresh twist to usual activities.

For example, The Chocolate Challenge uses hands-on tasks to boost teamwork and think ahead. MBTI tools help with self-knowledge and valuing team variety.

Hands-On Learning: The Chocolate Challenge

The Chocolate Challenge is a great team-building activity. Teams make chocolate products together. This boosts engagement and promotes teamwork and learning.

It lets participants connect in meaningful ways. Here’s what The Chocolate Challenge does for teams:

Unlocking Creativity with Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Programs

MBTI workshops are great for team building. They help teams understand their personality types. This boosts creativity and team work.

MBTI makes teams more cohesive by:

- Improving communication and reducing conflicts through understanding differences.

- Encouraging innovative problem-solving by valuing unique perspectives.

- Focusing on personal development to increase team performance and happiness.

Activities like The Chocolate Challenge and MBTI workshops mix fun, creativity, and growth.

They’re not just original. They blend play with purpose. This helps teams become strong and ready to face any challenge together.

Got Team Building Games? – PRESS PLAY #funatwork #gameshows #boostmorale

Book a live game show experience today! Contact us for further details. For Immediate assistance by text – 917-670-4689 No deposit required. We plan and facilitate all activities

Overcoming Challenges with Tailored Team Building Solutions

Looking closely at team dynamics shows that general solutions don’t always work. A deep insight into each company’s culture is essential.

By understanding what makes each team unique, we apply the most effective team building best practices . This is something many team building case studies have shown to be true.

When a team’s core values are part of their daily routine, they handle problems better. These challenges then help the team grow and innovate together. Team building isn’t just for solving issues. It’s about turning these issues into chances for improvement.

Take a global company dealing with communication problems due to cultural differences. Creating team building activities that value everyone’s background can improve work relationships. It makes cultural diversity a key benefit to the company.

In small businesses, personal conflicts can really hold back progress. Tailored team building that teaches conflict resolution and understanding makes teams stronger.

This way, they can be creative and solve not only current problems but also future ones. This strategy has been proven by many team building case studies .

But, it’s crucial to check if these strategies actually work. We look at feedback, performance data, and team behavior before and after team building. This ensures lasting improvements in teamwork and strength.

In summary, addressing team challenges with specific solutions proves most effective. Giving teams the right tools for their unique needs improves their work and motivation. When done right, the impact on performance and team spirit is incredible.

Measuring Impact and Success of Team Building Interventions

Exploring the real impact of team building in companies is fascinating. We see clear benefits from these efforts. These benefits range from better performance to improved team dynamics.

Quantitative Analysis: Performance Metrics Post Team Building

Quantitative metrics help us see if team building works. We use numbers to look at the positive changes team building makes. By checking performance before and after, we learn about the benefits of these activities.

Qualitative Feedback: Employee Engagement and Morale

Measuring success goes beyond numbers. We also focus on feelings and social changes from team building. Personal stories and surveys show us the unseen advantages.

They tell us about better teamwork, more joy at work, and a more positive culture.

- Increases in reported job satisfaction

- Testimonials about improved workplace relationships

- Growth in employee engagement levels

- Expressions of a stronger alignment with company values

To wrap up, looking at both data and stories is key. This way, we see all the benefits of team building . It proves team building is crucial for strong, healthy companies.

Team Building Best Practices from Real-World Applications

I’ve learned a lot about team building by looking at the real world. Transparent communication is key, I found. It strengthens trust and keeps away misunderstandings that could lead to conflict.

Teams work better when everyone feels they are listened to and understood.

In my journey, I saw how important including everyone in decisions is. It brings out creative ideas and strong strategies.

This not only strengthens the team but also improves how well they perform. When each person can share their thoughts and feels valued, the team’s output is amazing.

Support in a team means more than just encouragement. It involves helpful feedback, resources for growth, and celebrating achievements.

Teams that get this kind of support work better together. They have strong connections, high morale, and a united front. These practices aren’t just advice; they’re clear steps towards building a successful, collaborative team.

FAQ – Team Building Case Studies

What are some effective team building case studies.

Companies big and small have benefited from team building. These activities focus on improving communication, trust, and working together.

For instance, tech companies might mix workers from different departments for projects.

Startups may have retreats to unify their teams and set common goals.

How does truth-telling contribute to trust in team building?

Being honest is key in teams. It makes a team’s culture strong and trustworthy. Leaders play a big role by encouraging open talks.

This reduces gossip and helps teams in any work setting.

How is self-awareness integrated into leadership development programs?

Self-awareness is vital in leadership programs. It makes leaders mindful of their impact on the team. Through tools, feedback, and coaching, leaders learn to better the group’s unity and results.

Can you give an example of how large corporations approach team building?

Big companies tackle team building amidst their vast and varied workforce. They use special programs to break down barriers and boost teamwork. Global firms might include training on cultural intelligence to aid diverse teams.

What does the storming phase of team development entail?

The storming phase comes second in developing a team. Members test their limits and roles here. It’s a time for setting how to communicate and solve conflicts in positive ways.

What team building activities can help resolve inter-team conflict?

Focus on activities that foster talking and solving problems together. Workshops on resolving conflicts, role-playing, and team assessments are good. They help see each other’s views and collaborate better.

How can teams adapt to rapid changes effectively?

Ready teams can quickly adjust to changes. A shared goal, good conflict skills, and adaptable rules are key. Training for change helps teams adjust swiftly.

How important are cultural considerations in global team building?

They’re crucial. Cultural differences can confuse and slow down global teams. Building such teams needs an understanding of various cultures to include everyone and work well together.

What specific challenges can tailored team building address?

Custom team building can solve particular problems. It can improve talk between sections, help people collaborate on big projects, or welcome new folks from various cultures. Right activities make a difference.

What are some benefits of team building in organizations?

Studies confirm team building boosts communication, productivity, and morale. It also strengthens bonds, sparks creativity, and helps in solving problems.

How can the Insights tool help improve team effectiveness?

The Insights tool gives a clear view of a team’s preferences and challenges. Knowing this, teams can play to their strengths. This leads to better results and teamwork.

What are some innovative team building activities that have proven successful?

Some fun activities include The Chocolate Challenge for strategy and teamwork. Programs like Myers-Briggs help understand different personalities. These activities are engaging and promote unity.

How do organizations measure the impact of team building interventions?

Results are seen in improved numbers, like better performance and productivity. Feedback and how happy employees feel also show success. Keeping track of these can highlight a program’s value.

What best practices have emerged from real-world team building applications?

Best practices involve open communication, celebrating shared achievements, valuing different ideas, and matching activities with the group’s main values. These help build a lasting spirit of teamwork.

Source Links

- https://medium.com/@lafair.sylvia/case-study-for-leadership-development-and-team-collaboration-4b1c1f0d6b89

- https://www.insights.com/us/products/insights-team-effectiveness/

- https://www.freshtracks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/FreshTracksCaseStudies.pdf

Attention: HR Managers, Team Leaders, and Executive Assistants

Looking to book your next team building experience with no deposit required? Give us a call. Live Game Shows are our specialty.

You May Also Like…

Engaging Client Entertainment Ideas for Businesses

May 2, 2024

Did you know that 76% of clients are more likely to recommend a business after attending a memorable client...

Local Office Party Entertainment Services & Ideas | NJ/NYC

Are you in search of local office party entertainment in NJ? Are you looking to elevate your corporate events with a...

Executive Team Building Retreat Games

May 1, 2024

Executive team building retreat games are a crucial aspect of developing a high-functioning and effective executive...

PROMO: 10% OFF

No deposit required.

Book a game show within next 48 hours and get a discount upto 10%.

We will contact you shortly.

- Share full article

The Work Issue

What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team

New research reveals surprising truths about why some work groups thrive and others falter.

Credit... Illustration by James Graham

Supported by

By Charles Duhigg

- Feb. 25, 2016

L ike most 25-year-olds, Julia Rozovsky wasn’t sure what she wanted to do with her life. She had worked at a consulting firm, but it wasn’t a good match. Then she became a researcher for two professors at Harvard, which was interesting but lonely. Maybe a big corporation would be a better fit. Or perhaps a fast-growing start-up. All she knew for certain was that she wanted to find a job that was more social. ‘‘I wanted to be part of a community, part of something people were building together,’’ she told me. She thought about various opportunities — Internet companies, a Ph.D. program — but nothing seemed exactly right. So in 2009, she chose the path that allowed her to put off making a decision: She applied to business schools and was accepted by the Yale School of Management.

When Rozovsky arrived on campus, she was assigned to a study group carefully engineered by the school to foster tight bonds. Study groups have become a rite of passage at M.B.A. programs, a way for students to practice working in teams and a reflection of the increasing demand for employees who can adroitly navigate group dynamics. A worker today might start the morning by collaborating with a team of engineers, then send emails to colleagues marketing a new brand, then jump on a conference call planning an entirely different product line, while also juggling team meetings with accounting and the party-planning committee. To prepare students for that complex world, business schools around the country have revised their curriculums to emphasize team-focused learning.

Every day, between classes or after dinner, Rozovsky and her four teammates gathered to discuss homework assignments, compare spreadsheets and strategize for exams. Everyone was smart and curious, and they had a lot in common: They had gone to similar colleges and had worked at analogous firms. These shared experiences, Rozovsky hoped, would make it easy for them to work well together. But it didn’t turn out that way. ‘‘There are lots of people who say some of their best business-school friends come from their study groups,’’ Rozovsky told me. ‘‘It wasn’t like that for me.’’

Instead, Rozovsky’s study group was a source of stress. ‘‘I always felt like I had to prove myself,’’ she said. The team’s dynamics could put her on edge. When the group met, teammates sometimes jockeyed for the leadership position or criticized one another’s ideas. There were conflicts over who was in charge and who got to represent the group in class. ‘‘People would try to show authority by speaking louder or talking over each other,’’ Rozovsky told me. ‘‘I always felt like I had to be careful not to make mistakes around them.’’

So Rozovsky started looking for other groups she could join. A classmate mentioned that some students were putting together teams for ‘‘case competitions,’’ contests in which participants proposed solutions to real-world business problems that were evaluated by judges, who awarded trophies and cash. The competitions were voluntary, but the work wasn’t all that different from what Rozovsky did with her study group: conducting lots of research and financial analyses, writing reports and giving presentations. The members of her case-competition team had a variety of professional experiences: Army officer, researcher at a think tank, director of a health-education nonprofit organization and consultant to a refugee program. Despite their disparate backgrounds, however, everyone clicked. They emailed one another dumb jokes and usually spent the first 10 minutes of each meeting chatting. When it came time to brainstorm, ‘‘we had lots of crazy ideas,’’ Rozovsky said.

One of her favorite competitions asked teams to come up with a new business to replace a student-run snack store on Yale’s campus. Rozovsky proposed a nap room and selling earplugs and eyeshades to make money. Someone else suggested filling the space with old video games. There were ideas about clothing swaps. Most of the proposals were impractical, but ‘‘we all felt like we could say anything to each other,’’ Rozovsky told me. ‘‘No one worried that the rest of the team was judging them.’’ Eventually, the team settled on a plan for a microgym with a handful of exercise classes and a few weight machines. They won the competition. (The microgym — with two stationary bicycles and three treadmills — still exists.)

Rozovsky’s study group dissolved in her second semester (it was up to the students whether they wanted to continue). Her case team, however, stuck together for the two years she was at Yale.

It always struck Rozovsky as odd that her experiences with the two groups were dissimilar. Each was composed of people who were bright and outgoing. When she talked one on one with members of her study group, the exchanges were friendly and warm. It was only when they gathered as a team that things became fraught. By contrast, her case-competition team was always fun and easygoing. In some ways, the team’s members got along better as a group than as individual friends.

‘‘I couldn’t figure out why things had turned out so different,’’ Rozovsky told me. ‘‘It didn’t seem like it had to happen that way.’’

O ur data-saturated age enables us to examine our work habits and office quirks with a scrutiny that our cubicle-bound forebears could only dream of. Today, on corporate campuses and within university laboratories, psychologists, sociologists and statisticians are devoting themselves to studying everything from team composition to email patterns in order to figure out how to make employees into faster, better and more productive versions of themselves. ‘‘We’re living through a golden age of understanding personal productivity,’’ says Marshall Van Alstyne, a professor at Boston University who studies how people share information. ‘‘All of a sudden, we can pick apart the small choices that all of us make, decisions most of us don’t even notice, and figure out why some people are so much more effective than everyone else.’’

Yet many of today’s most valuable firms have come to realize that analyzing and improving individual workers — a practice known as ‘‘employee performance optimization’’ — isn’t enough. As commerce becomes increasingly global and complex, the bulk of modern work is more and more team-based. One study, published in The Harvard Business Review last month , found that ‘‘the time spent by managers and employees in collaborative activities has ballooned by 50 percent or more’’ over the last two decades and that, at many companies, more than three-quarters of an employee’s day is spent communicating with colleagues.

In Silicon Valley, software engineers are encouraged to work together, in part because studies show that groups tend to innovate faster, see mistakes more quickly and find better solutions to problems. Studies also show that people working in teams tend to achieve better results and report higher job satisfaction. In a 2015 study, executives said that profitability increases when workers are persuaded to collaborate more. Within companies and conglomerates, as well as in government agencies and schools, teams are now the fundamental unit of organization. If a company wants to outstrip its competitors, it needs to influence not only how people work but also how they work together .

Five years ago, Google — one of the most public proselytizers of how studying workers can transform productivity — became focused on building the perfect team. In the last decade, the tech giant has spent untold millions of dollars measuring nearly every aspect of its employees’ lives. Google’s People Operations department has scrutinized everything from how frequently particular people eat together (the most productive employees tend to build larger networks by rotating dining companions) to which traits the best managers share (unsurprisingly, good communication and avoiding micromanaging is critical; more shocking, this was news to many Google managers).

The company’s top executives long believed that building the best teams meant combining the best people. They embraced other bits of conventional wisdom as well, like ‘‘It’s better to put introverts together,’’ said Abeer Dubey, a manager in Google’s People Analytics division, or ‘‘Teams are more effective when everyone is friends away from work.’’ But, Dubey went on, ‘‘it turned out no one had really studied which of those were true.’’

In 2012, the company embarked on an initiative — code-named Project Aristotle — to study hundreds of Google’s teams and figure out why some stumbled while others soared. Dubey, a leader of the project, gathered some of the company’s best statisticians, organizational psychologists, sociologists and engineers. He also needed researchers. Rozovsky, by then, had decided that what she wanted to do with her life was study people’s habits and tendencies. After graduating from Yale, she was hired by Google and was soon assigned to Project Aristotle.

P roject Aristotle’s researchers began by reviewing a half-century of academic studies looking at how teams worked. Were the best teams made up of people with similar interests? Or did it matter more whether everyone was motivated by the same kinds of rewards? Based on those studies, the researchers scrutinized the composition of groups inside Google: How often did teammates socialize outside the office? Did they have the same hobbies? Were their educational backgrounds similar? Was it better for all teammates to be outgoing or for all of them to be shy? They drew diagrams showing which teams had overlapping memberships and which groups had exceeded their departments’ goals. They studied how long teams stuck together and if gender balance seemed to have an impact on a team’s success.

No matter how researchers arranged the data, though, it was almost impossible to find patterns — or any evidence that the composition of a team made any difference. ‘‘We looked at 180 teams from all over the company,’’ Dubey said. ‘‘We had lots of data, but there was nothing showing that a mix of specific personality types or skills or backgrounds made any difference. The ‘who’ part of the equation didn’t seem to matter.’’

Some groups that were ranked among Google’s most effective teams, for instance, were composed of friends who socialized outside work. Others were made up of people who were basically strangers away from the conference room. Some groups sought strong managers. Others preferred a less hierarchical structure. Most confounding of all, two teams might have nearly identical makeups, with overlapping memberships, but radically different levels of effectiveness. ‘‘At Google, we’re good at finding patterns,’’ Dubey said. ‘‘There weren’t strong patterns here.’’

As they struggled to figure out what made a team successful, Rozovsky and her colleagues kept coming across research by psychologists and sociologists that focused on what are known as ‘‘group norms.’’ Norms are the traditions, behavioral standards and unwritten rules that govern how we function when we gather: One team may come to a consensus that avoiding disagreement is more valuable than debate; another team might develop a culture that encourages vigorous arguments and spurns groupthink. Norms can be unspoken or openly acknowledged, but their influence is often profound. Team members may behave in certain ways as individuals — they may chafe against authority or prefer working independently — but when they gather, the group’s norms typically override individual proclivities and encourage deference to the team.

Project Aristotle’s researchers began searching through the data they had collected, looking for norms. They looked for instances when team members described a particular behavior as an ‘‘unwritten rule’’ or when they explained certain things as part of the ‘‘team’s culture.’’ Some groups said that teammates interrupted one another constantly and that team leaders reinforced that behavior by interrupting others themselves. On other teams, leaders enforced conversational order, and when someone cut off a teammate, group members would politely ask everyone to wait his or her turn. Some teams celebrated birthdays and began each meeting with informal chitchat about weekend plans. Other groups got right to business and discouraged gossip. There were teams that contained outsize personalities who hewed to their group’s sedate norms, and others in which introverts came out of their shells as soon as meetings began.

After looking at over a hundred groups for more than a year, Project Aristotle researchers concluded that understanding and influencing group norms were the keys to improving Google’s teams. But Rozovsky, now a lead researcher, needed to figure out which norms mattered most. Google’s research had identified dozens of behaviors that seemed important, except that sometimes the norms of one effective team contrasted sharply with those of another equally successful group. Was it better to let everyone speak as much as they wanted, or should strong leaders end meandering debates? Was it more effective for people to openly disagree with one another, or should conflicts be played down? The data didn’t offer clear verdicts. In fact, the data sometimes pointed in opposite directions. The only thing worse than not finding a pattern is finding too many of them. Which norms, Rozovsky and her colleagues wondered, were the ones that successful teams shared?

I magine you have been invited to join one of two groups.

Team A is composed of people who are all exceptionally smart and successful. When you watch a video of this group working, you see professionals who wait until a topic arises in which they are expert, and then they speak at length, explaining what the group ought to do. When someone makes a side comment, the speaker stops, reminds everyone of the agenda and pushes the meeting back on track. This team is efficient. There is no idle chitchat or long debates. The meeting ends as scheduled and disbands so everyone can get back to their desks.

Team B is different. It’s evenly divided between successful executives and middle managers with few professional accomplishments. Teammates jump in and out of discussions. People interject and complete one another’s thoughts. When a team member abruptly changes the topic, the rest of the group follows him off the agenda. At the end of the meeting, the meeting doesn’t actually end: Everyone sits around to gossip and talk about their lives.

Which group would you rather join?

In 2008, a group of psychologists from Carnegie Mellon, M.I.T. and Union College began to try to answer a question very much like this one. ‘‘Over the past century, psychologists made considerable progress in defining and systematically measuring intelligence in individuals,’’ the researchers wrote in the journal Science in 2010 . ‘‘We have used the statistical approach they developed for individual intelligence to systematically measure the intelligence of groups.’’ Put differently, the researchers wanted to know if there is a collective I. Q. that emerges within a team that is distinct from the smarts of any single member.