Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3: Cyberbullying Within the Context of Peers and School

Krista Mehari and Natasha Basu

Effective cyberbullying prevention is based on an accurate understanding of risk and protective factors of cyberbullying across systems. Cyberbullying prevention should include individual, relationship, community, and societal factors. Cyberbullying is closely related to in-person bullying and aggression, but it has some unique risk and protective factors also. This chapter conceptualizes cyberbullying as broadly within the umbrella of peer interactions. In this chapter, we describe how other peer interactions and peer relationships can predict the occurrence of cyberbullying and cybervictimization. Similarly, given that youth spend the majority of their time at school, school plays a fundamental role in adolescents’ lives. In this chapter, we also discuss school-level factors that predict or reduce cyberbullying. These factors can be leveraged for school-based prevention. The chapter concludes with the current understanding of effective school-based prevention and school practices in responding to cyberbullying.

As discussed in previous chapters, cyberbullying is perpetrated through electronic communication technologies. Individual, peer, and school factors play an important role in the development of cyberbullying behaviors. Cyberbullying involvement has significant implications for adolescents’ peer and school interactions. Within the context of the socio-ecological model introduced in Chapter 1, peer interactions fall within “relationship” factors, and school factors fall within the “community” level. Cyberbullying happens among peers, so it is important to understand how other peer interactions and peer relationships can predict the occurrence of cyberbullying and cybervictimization. Similarly, understanding school-level factors that predict or reduce cyberbullying is vital for effective intervention.

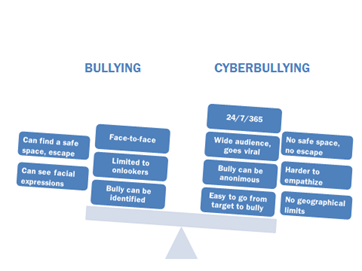

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT AND BULLYING INVOLVEMENT

Cyberbullying and cybervictimization are closely related to in-person bullying and in-person victimization. Many studies have demonstrated strong concurrent relations between cyberbullying and in-person bullying. According to a meta-analysis, in-person bullying is one of the best predictors of cyberbullying. The only stronger correlate of cyberbullying identified in the meta-analysis was cybervictimization. [1] Most of the research on what predicts cyberbullying has been conducted in Western countries. [2]

Research across Asian countries is limited. The available research demonstrates a positive association between in-person bullying and cyberbullying. In a study conducted among adolescents in New Delhi, India, cyberbullying was correlated with indirect or relational bullying but not with physical bullying. [3] In a study conducted with Chinese high school students, in-person bullying was found to be a significant and strong predictor of cyberbullying. [4] Research conducted among South Korean adolescents found a significant positive association between in-person bullying and cyberbullying. [5] Additionally, Kwan and Skoric [6] found strong associations between school bullying and cyberbullying ( r = .56) in adolescents from Singapore. In Hong Kong, a study conducted with 1917 adolescents found a positive correlation between in-person bullying and cyberbullying ( r = .51). [7] Further, in-person bullying was positively associated with cyberbullying in Cyprus ( r = .61). [8]

Based on the existing research in both Western and Asian countries, it is likely that both cyberbullying and in person bullying are types of bullying that manifest through different media. Almost all youth who perpetrate cyberbullying also perpetrate in-person bullying. It is highly uncommon for youth to perpetrate cyberbullying without also having perpetrated in-person bullying. However, it is likely that a smaller percentage of youth who perpetrate in-person bullying also perpetrate cyberbullying. [9] , [10] , [11] These findings suggest that interventions to reduce in-person bullying may be effective in reducing cyberbullying. However, given that cyberbullying is different from bullying, those interventions may need to be adapted slightly to address the unique aspects of cyberbullying.

Similarly, cybervictimization and in-person victimization are also closely correlated. In the meta-analysis conducted by Kowalski and colleagues, [12] cybervictimization and in-person victimization were correlated at r = .4 indicating a small-to-medium relationship. Again, the only stronger correlate of cybervictimization was cyberbullying. [13] More recent research using behavior-based measures has identified correlations between cybervictimization and in-person victimization as large as .85, indicating a large relationship. Again, most research has been conducted in Western countries.

Emerging research in Asia provides emerging support for the relation between cybervictimization and in-person victimization. For example, a study conducted in Hong Kong found in-person victimization was positively associated with cyberbullying victimization. [14] This relationship was also significant in South Korean adolescents. [15] A positive relationship was demonstrated between in-person victimization and cybervictimization in China ( r = .18), [16] Cyprus ( r = .48), [17] Japan ( r = .32), [18] India ( r = .13), [19] Indonesia ( r = .73), [20] and Singapore ( r = .48). [21] However, one study conducted among middle school students in New Delhi, India did not find a relation between cybervictimization and in-person victimization. [22] However, the majority of the research suggests that cybervictimization and in-person victimization are correlated in Asia. Together, there appears to be a significant association between in-person bullying and cyberbullying across different cultures and countries in Asia.

Based on emerging longitudinal research, it appears that youth are first victimized in person. Youth who are victimized in-person are more likely to experience increases in cybervictimization. For example, it is possible that rumors that are started about an adolescent in person are then spread via text messages or social media. It is also possible that adolescents who victimize a particular adolescent in person begin victimizing that adolescent online in other ways (e.g., making fun of photos, posting rude comments, sending threats). In contrast, youth who are cyber-victimized are not more likely to experience increases in in-person victimization. [23] , [24] That is, there is no evidence that victimization that starts online causes an increase in in-person victimization.

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT AND INDIVIDUAL FACTORS

A range of individual-level characteristics, such as demographics (e.g., gender, age) and psycho-social factors (such as attitudes and impulsivity) have been explored as possible factors of cyberbullying. These factors can predict why some youth are more likely to be involved in cyberbullying than others.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN CYBERBULLYING

There is varying evidence about the rates of cyberbullying across gender. Multiple studies have identified higher prevalence of self-reported cyberbullying among male adolescents. This includes a sample adolescents in Australia, Canada, Finland, Taiwan, Turkey, Singapore, and Switzerland. [25] , [26] , [27] , [28] , [29] , [30] However, several of these studies used the word “bullied” in their measure, which male adolescents may be more willing to endorse because it is less socially undesirable for a boy to admit to bullying than for a girl. Ybarra and Mitchell (2007), who avoided the word “bullied” in their measure, found no gender differences in prevalence of cyberbullying. Still, male adolescents were more likely to be frequent aggressors. [31] On the other hand, Calvete and colleagues (2010) found that there were no gender differences in frequency of perpetration overall, but that male adolescents were more likely to send sexual messages and to post videos of assaults. [32]

No gender differences in perpetration of cyberbullying were found in a number of studies in Canada. These studies included ethnically diverse samples of adolescents in Europe, the United States, and online. [33] , [34] , [35] , [36] , [37] , [38] , [39] , [40] , [41] , [42] Overall, findings indicate that there are no gender differences. If gender differences exist, male adolescents are slightly more likely to self-report perpetration of cyberbullying. Despite these findings, researchers continue to argue that female adolescents prefer indirect and relational forms of aggression that are easily perpetrated through electronic means. [43] This is not supported, and in fact often contradicted, by research.

Gender differences in cyberbullying in Asian countries and specifically in India have yet to be fully explored. One study of 11-15-year-old students in the Delhi area found that male adolescents reported higher prevalence of cybervictimization. There were no gender differences in cyberbullying perpetration. [44] In general, existing surveillance data suggest that male adolescents have greater access to electronic communication devices than female adolescents in India, especially in rural areas. [45] It is possible that male adolescents may be more likely to have cyberbullying involvement simply due to access. More research is needed to explore whether there are gender differences in cyberbullying involvement in India.

AGE DIFFERENCES IN CYBERBULLYING ACROSS ADOLESCENCE

In addition to gender differences, several studies have explored age differences in cyberbullying across adolescence. There is some evidence that cyberbullying peaks in early adolescence (11-14 years old) and decreases in later adolescence (15 years old and older). This finding is comparable to the trajectory observed in in-person bullying. This broad pattern has been found in the U.S. and Canada. [46] , [47] , [48] It is possible that as adolescents enter secondary schools (e.g., middle school, junior high, high school) where they are first exposed to cyberbullying. Then they begin to perpetrate cyberbullying due to observational learning and perhaps reactive aggression. It is unclear whether this pattern is comparable in other countries, especially in lower or middle-income countries, where private access to electronic communication devices might be less common in early adolescence.

PSYCHO-SOCIAL RISK FACTORS FOR CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT

Most research on individual-level factors associated with cyberbullying involvement has been cross-sectional. That is, the hypothesized “risk” factors are assessed at the same time point as the outcome (cyberbullying involvement). Therefore, it is impossible to determine whether these factors cause cyberbullying, whether cyberbullying causes those other factors, or whether something else (something that was not assessed) causes both cyberbullying involvement and the other factors. Because of this, at most, we can assume that these factors co-occur with cyberbullying involvement.

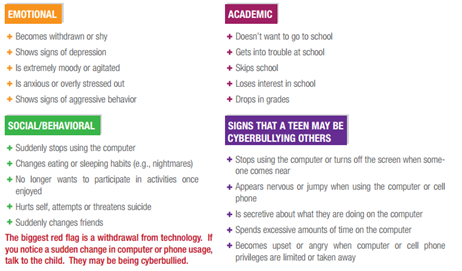

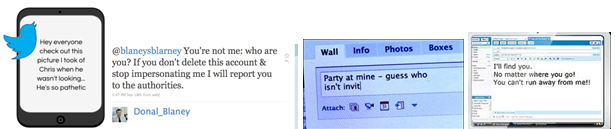

Psycho-social characteristics that may place adolescents at risk for cyberbullying perpetration include low levels of empathy, moral disengagement, beliefs supporting aggression, impulsivity, other delinquent behavior, and substance use. [49] , [50] , [51] , [52] , [53] , [54] In addition, adolescents who use the Internet more frequently and engage in more risky online behaviors (e.g., sharing personal information, agreeing to meet in person with someone they met online) are more likely to perpetrate cyberbullying. [55] Patterns of Internet usage also predict other digital risks such as online sexual solicitations and sexual risk behaviors, exposure to a variety of explicit content, and information breaches and privacy violations. This is explained in further detail in Chapter 5 of this book.

Similar to cyberbullying perpetration, psycho-social characteristics that place adolescents at risk for cybervictimization include low levels of empathy, beliefs supporting aggression, lower social intelligence and social anxiety, lower academic achievement, substance use, and loneliness. [56] As with cyberbullying perpetration, adolescents who spend more time on the Internet and engage in more risky online behaviors are more likely to be victimized. [57] , [58] It is important to note that most of the research on psycho-social predictors of cyberbullying involvement was conducted in Western and high-income countries. It is unclear whether risks for cyberbullying perpetration would be the same or different in Asian countries and lower- to middle-income countries. Because of this, more research is needed to understand what individual-level factors may explain individual differences in cyberbullying involvement among youth in Asian countries.

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT AND PEER FACTORS

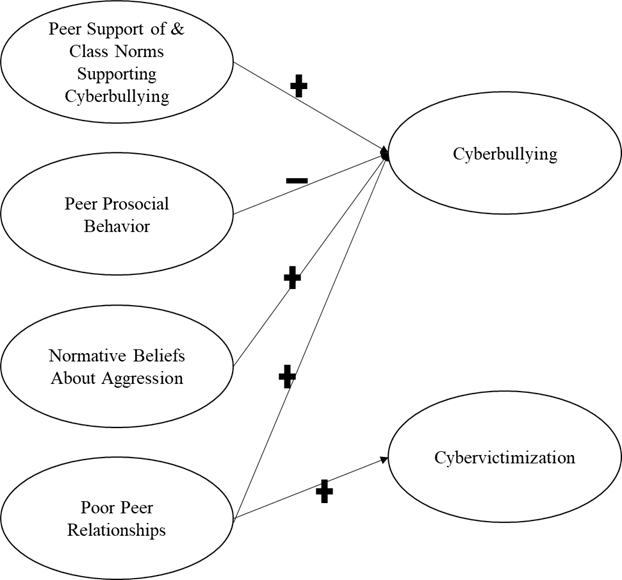

Peer factors fall within the “relationship” domain of the socio-ecological model. Like individual-level factors, they explain a significant percentage of differences in youths’ levels of cyberbullying involvement. Broadly, peer attitudes supporting bullying or cyberbullying predict individual youths’ levels of bullying and cyberbullying perpetration. [59] This may be due to social mimicry. Specifically, peers who support cyberbullying may be more likely to model cyberbullying behaviors. This may cause increased cyberbullying due to increased exposure to aggressive peer models. [60] In addition, when adolescents do try out aggressive behaviors, they are likely to be reinforced by their peers if their peers have attitudes justifying cyberbullying perpetration. For example, when adolescents believe their peers support and approve of cyberbullying, they are more likely to take online risks like cyberbullying. [61] Adolescents who have pro-social peers have lower levels of cyberbullying.

In a peer group that supports aggression, using aggression may provide adolescents with power, status, and privilege among their peers. This finding is consistent with a research study conducted with adolescents from Singapore and Malaysia, whose ethnic identification included Chinese, Malay, and Indian. It found a positive association between cyberbullying and normative beliefs about aggression. [62] Reinforcement by friends was found to be positively associated with cyberbullying in Japan. [63] This finding is supported by a qualitative study in Indonesia which demonstrated that group conformity facilitated an increase in the prevalence of cyberbullying among adolescents. [64] Finally, a study in China found that pro-cyberbullying class norms predicted the occurrence of cyberbullying in high school. [65] Interestingly, this was only true when students perceived their class to be highly cohesive. In contrast, when a high school student perceived their class to have low cohesion, there was not a significant relationship between pro-cyberbullying class norms and incidents of cyberbullying. [66] This study demonstrated one possible mechanism for why these normative beliefs might vary across groups.

Popularity and social acceptance may play an interesting role in cyberbullying. One study of adolescents in the western United States found that both cyberbullying and cybervictimization were positively associated with popularity and social acceptance cross-sectionally. In addition, popularity predicted increases in cyberbullying, whereas cyberbullying predicted increases in popularity for girls but decreases in popularity for boys. Social acceptance predicted increased cyberbullying for boys but not for girls. [67] In a sample of students in secondary schools in Germany, cybervictimization during chat sessions was negatively associated with self-reported perceived popularity with other chatters. [68] In a sample of elementary school children in a predominantly white, upper SES school in the United States, cyberbullying perpetration was concurrently associated with lower popularity and social acceptance. Both popularity and social acceptance were measured by peer report. Similarly, cyberbullying was associated with fewer mutual friendships. [69] Currently, the majority of the research on popularity, social acceptance, and cyberbullying is conducted in Europe and North America. As such, there is no research on the generalizability of these relationships in Asian countries.

The relation between peer rejection and cyberbullying is complex. In a study of middle school students in the midwestern United States, peer rejection was concurrently correlated with relational and verbal cyberbullying. It also predicted increases in cyberbullying. [70] Cyberbullying was also linked to loneliness in a sample of elementary school children in the United States. [71] Research conducted in Asia also suggests that cyberbullying involvement is associated with poor peer relationships. For example, a study of Chinese middle school students found a positive association between cyberbullying and loneliness. [72] Similarly, another cross-sectional study of Chinese middle school students reported better peer relationships were negatively associated with engagement in cyberbullying. [73] Cross-national research conducted with adolescents living in China, India, and Japan found that peer attachment was negatively associated with cyberbullying perpetration in China and India, but not in Japan. Additionally, within China, India, and Japan, adolescents who were not involved in cyberbullying had greater peer attachment compared to youth with any involvement in cyberbullying (victimization, perpetration, or some combination of those). [74]

It is possible that peer rejection and aggression are part of a vicious cycle. In this cycle, children who are aggressive in a non-socially skilled way are more likely to be rejected. Children may react to rejection with increased aggression. It is also possible that adolescents engage in cyberbullying as a way to establish their social position and to attempt to maintain their social status. However, it is possible that the skill level of adolescents varies widely. This means that cyberbullying may promote the social status of socially skilled youth, but that it may harm the social status of socially awkward youth. It is also possible that cyberbullying is less reinforced than in-person bullying. Thus, is less likely to promote social dominance, than in-person bullying [75] because of the asynchronicity of interactions during online communications. That is, an adolescent could post a mocking picture of a peer, but not know or notice when it was shared, laughed at, or commented on. It is also possible that fewer peers in the same social circles would know about the post than if it happened in person at school, where youth spend the majority of their time together.

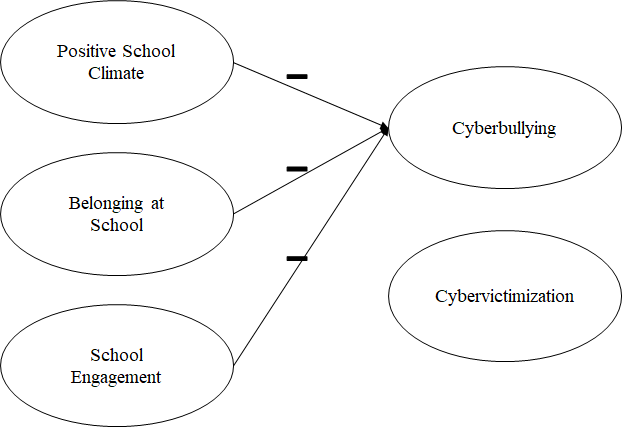

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT AND SCHOOL FACTORS

School factors fall within the “community” level of the socio-ecological model. Like individual and relationship level factors, school factors explain a small but significant amount of individual differences in cyberbullying. Although schools are often on the front lines of confronting cyberbullying behaviors (Pelfrey et al., 2015), little is known about the associations between school factors and cyberbullying involvement. It is important to note that cyberbullying appears to have higher rates of perpetration during out-of-school time compared to during school hours (e.g., Smith et al., 2008). Therefore, although supervision and restriction may reduce cyberbullying during the school day, it may not help in prevention of all acts of cyberbullying. Other factors related to school climate, including fostering a positive climate and promoting healthy relationships, may be more important. In a meta-analysis of research mostly conducted in Western countries, school climate and school safety had small but significant correlations with lower rates of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization (Kowalski et al., 2014). That is, adolescents in schools that they perceived to be safe, with positive student-student and student-teacher relationships, were less likely both to perpetrate cyberbullying and experience cybervictimization. In school environments, close relationships with teachers are associated with reduced likelihood of bullying and cyberbullying. [76] Teachers’ awareness of cyberbullying and intervention has also been related to lower rates cyberbullying. [77] At an individual level, youth who are involved in cyberbullying may have more problems at school than youth who are not involved in cyberbullying, such as getting in trouble and not feeling safe at school. [78] , [79]

School risk factors for cyberbullying involvement is an emerging body of research in Asian countries. Wang and colleagues (2019) found in a study conducted in China that adolescents who perceived a more positive school climate were less likely to perpetrate cyberbullying. [80] Further, in a study of Hong Kong youth, a sense of belonging at school was associated with lower levels of cyberbullying perpetration. [81] A more recent study in Hong Kong found different relations between school factors and cyberbullying for male and female students. [82] For male adolescents, positive school experiences and school involvement were negatively associated with cyberbullying perpetration. For female adolescents, a sense of belonging in school was negatively associated with cyberbullying perpetration. [83] Together, these studies underscore the importance of considering school influences to understand developmental processes that lead to cyberbullying.

SCHOOL-BASED PREVENTION PROGRAMS

Schools can be an ideal setting for prevention efforts due to their reach. The heavy majority of youth attend school. Because of this, schools have a golden opportunity to promote the safety, health, well-being, and citizenship of the majority of youth in a country. School-based prevention strategies include primary prevention (strategies to prevent cyberbullying before it begins) and secondary prevention (strategies to reduce the frequency of cyberbullying or mitigate the impact of cyberbullying). A combination of the two strategies is important for a holistic prevention approach. In addition to specific prevention programs, schools can create policies that may serve as primary and secondary prevention strategies. There can be two approaches to these prevention strategies: a punitive, fear-based approach, or a resilience-based approach. A fear-based approach includes heavy restrictions of digital media, zero-tolerance policies, and punishment for undesired behavior without training, modeling, scaffolding of, and reinforcement of desired behavior. In contrast, a resilience-based approach focuses on creating a positive school climate; training, modeling, and reinforcing desired behaviors. It also focuses on building capacity in adult stakeholders to prevent and intervene in cyberbullying. Further it focuses on providing remedial skill-building for youth who engage in cyberbullying.

PRIMARY PREVENTION

Existing reviews of cyberbullying prevention programs suggest that most cyberbullying prevention programs are school-based and show promise of effectiveness. [84] , [85] , [86] However, in general, individual programs have only been supported by a single research study conducted by the program developers. [87] More research is needed to identify the active ingredients for effective school-based cyberbullying prevention programs. Due to the high degree of overlap between cyberbullying and in-person bullying, many of the skills taught in school-based violence or bullying prevention programs are likely to be relevant to the reduction of cyberbullying. Such programs may include anger management, empathy, and problem-solving.

However, because of the differences in circumstances surrounding in-person and electronic communication, those programs may need to be adapted or include cyberbullying-specific modules. For example, teaching adolescents to read facial expressions or other physical cues will not improve empathy in situations where the other person’s facial expressions are not visible. In that case, teaching perspective-taking based on identifying the situation and thinking about how people might feel when they were in that situation may help to improve empathy in electronic communications. Beliefs about aggression are also particularly relevant to aggressive behaviors and may be different for cyberbullying. There is some emerging evidence to support this. [88] Intervention programs may need to target cyberbullying-specific beliefs. It is possible that adolescents perceive the social context for electronic aggression to be less disapproving than for in-person aggression. Initial focus group data also suggests that adults in India may be more tolerant of cyberbullying than of physical bullying. This may cause youth to believe that they may not have effective advocates in the adults close to them. [89] Because of this, school-based efforts may need to include education for parents and guardians on cyberbullying, its impact, and its prevention. In addition, for both youth and adults, digital safety behaviors, including protection of private information, should be taught as part of intervention programs. [90] , [91] A more comprehensive description of digital safety is provided in Chapter 5.

Promoting a positive school climate and positive peer relationships may also help to reduce cyberbullying. Adolescents are unlikely to tell their parents about victimization experiences, and even more unlikely to tell teachers. [92] , [93] , [94] , [95] On the other hand, as much as 75% of victimized adolescents will tell their friends. [96] Friendship is a strong resource for adolescents. It has been shown to mitigate the effects of victimization as well as to reduce the likelihood of victimization occurring in the future. [97] Because of this, interventions could also teach adolescents how they can best help their friends when they know that their friends are perpetrating cyberbullying, being cyber-victimized, or both.

PRIMARY PREVENTION: SCHOOL-LEVEL POLICY

Currently, many schools do not have policies and procedures around appropriate and safe behavior online. There is an urgent need for schools to establish and promulgate expectations for digital behavior and to identify procedures for when those expectations are not met. [98] Clear expectation-setting prior to problematic behavior can often reduce the occurrence of problematic behaviors. These policies should include identification and reinforcement of pro-social behavior both online and in-person. An example of an intervention based on clear expectation-setting and reinforcement of desired behaviors is School-Wide Positive Behavior Support (SWPBS). SWPBS is a widely-used, whole-school behavior support program that focuses on establishing clear behavior expectations for students. It also focuses on consistently reinforcing desired behavior across school settings, and identifying and implementing a range of consequences for problem behaviors. [99] Such school-level strategies can be helpful in preventing cyberbullying before it becomes a problem.

SECONDARY PREVENTION: SCHOOL RESPONSES TO CYBERBULLYING INCIDENTS

Even if the most effective primary prevention strategies are implemented, it is likely that some cyberbullying will occur. This creates a need to establish procedures to respond to cyberbullying. Cyberbullying is unusual in that it does not occur in a physical space. This raises the question of whose responsibility it is to monitor electronic interactions and enforce consequences for adolescents who are perpetrating cyberbullying. Most researchers have pointed to the schools as the primary responsible authority. Despite most cyberbullying occurring outside of school property, schools have an ethical and legal responsibility to intervene when cyberbullying creates an unsafe environment that impedes students’ ability to learn. [100] Schools are placed in a difficult position. On one hand, they may not violate students’ freedom of speech in countries that protect freedom of speech, particularly when that speech is occurring off school grounds. On the other hand, the school is required to provide a safe learning environment with equal access to education. A school is liable in the United States if it has “effectively caused, encouraged, accepted, tolerated, or failed to correct” a hostile environment that impairs a student’s ability to learn (p. S65). [101] Because of schools’ somewhat vague position as monitor and enforcer, it is also important for parents and guardians to be involved. Schools are only responsible to intervene when they are aware of the situation and can demonstrate that the situation is interfering in the learning process in some way. Parents and guardians can advocate for changes in school policy and government regulations, as well as draw media attention to areas of concern. [102] Parents and guardians can also monitor their children’s digital behavior, teach and model respectful interactions, and intervene if their child is aggressive or victimized.

As schools craft policies related to cyberbullying and digital behavior, there are important issues to keep in mind:

- Youth who are victimized should not be responsible for investigating or proving the incident. Before the aggressor is identified and the wrongful nature of the act is established, it is important that the person who reported the aggression (bystander, victim, or parent) does not bear the burden of proving what happened and who did it. It is an unfortunate effect of “innocent until proven guilty” that the victims or reporters are wrong until they prove themselves right. This approach decreases the likelihood that adolescents will put themselves through that painful process. One way to circumvent this unintentional punishment is to establish a school staff member to receive complaints, anonymously if desired, and to investigate the incident. Then, if aggression is established, the steps outlined in school policy must be followed. This will remove the burden of proof from reporters, thus teaching reporters that they will not be punished for seeking help. It will also teach adolescents who are perpetrating aggression that their behavior will be detected and addressed. The process of implementing clear, just school policies and procedures may change the dynamics from a conflict between the aggressor and the reporter (likely the victim) into an established procedure in which school officials take action against a violation of school policy.

- Restriction of victimized youths’ access to electronic media may be punitive and unhelpful. Encouraging adolescents who have been victimized to simply reduce their electronic interactions (e.g., taking down personal pages on social networking sites, or not going online at all) may be the first intervention response that comes to mind for adults. However, fear of online restriction is one of the primary reasons that adolescents do not tell adults about their victimization experiences. It is important to understand that adolescents consider reduced access to communication technologies to be a punishment. [103] , [104] It may be productive to encourage communication between adolescents and their teachers. But before this is done, adolescents must first know that reporting will both resolve the problem and not result in negative outcomes for themselves.

- Abusing youth who perpetrate cyberbullying is not effective in changing behavior. It is important not to place all the blame on adolescents who cyberbully. As shown by the high correlation between cyberbullying and cybervictimization, there are often no purely provocative adolescents or blameless victims. Adolescents learn negative patterns of interactions through modeling and reinforcement. They are often impulsive and misinterpret cues. Sometimes they may simply have difficulty taking the other person’s perspective into account or understanding the damage caused by their actions. In addition, there are currently few clear rules or expectations regarding electronic behavior, which may feed into a perception that aggressive behavior is not a problem and will not be punished. Anticipation of blame also reduces adolescents’ likelihood to report their experiences when victimized, because they believe that the only negative consequences will be for themselves (Mishna et al., 2009). The consequences for aggressive adolescents should be aversive but should also help them to identify pro-social strategies for reaching goals, managing anger, controlling impulsivity, and resolving conflict. Doing this will avoid abusing adolescents who likely have been victimized themselves while promoting a healthy and respectful electronic culture. Specific ways to accomplish these goals may include anger management or perspective-taking training.

- Most policy changes have not been empirically tested. Currently, the best-practice recommendations for school policy are based on descriptive research and anecdotal evidence. To address these issues, creating, implementing, and evaluating policies and procedures for cyberbullying involvement is vital (Hertz & David-Ferdon, 2008).

The following chapters discuss how to avoid cyberbullying and to some extent how to effectively deal with cyberbullying. Chapter four addresses parents’ and caregivers’ needs for guidance and reassurance on how best maintain their children’s safety online and protect against cyberbullying. We emphasize the importance of parent-child communication, warm parent-child relationships, and parental monitoring that supports adolescents’ search for autonomy. In short, this chapter details the role of family, especially parental relationships and media parenting with respect to cyberbullying behavior among youth.

Cyberbullying and cybervictimization are closely related to in-person bullying and victimization. Because we know that a range of individual psychosocial factors, relationship factors, and community factors predict cyberbullying, intervention strategies should not just target individual youth, but should also target peer groups and schools. Schools have the potential to play an important role in cyberbullying prevention. It is important to use the existing research on cyberbullying prevention and bullying prevention so that we can make sure that we are investing our resources in prevention strategies that keep youth safe online.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Peer and school factors predict perpetration of cyberbullying.

- Best practice cyberbullying prevention strategies should promote healthy relationship, emotion regulation, and problem-solving skills, as well as digital safety and citizenship.

- Effective prevention and intervention must include school-level policies and procedures that promote a positive school climate, create clear expectations for appropriate behavior, and identify resilience-based strategies to respond to cyberbullying incidents.

- Both school policy and prevention programs must be evaluated and modified to be maximally effective.

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin 2014;140(4):1073-1073-1137. ↵

- Farrell AD, Thompson EL, Mehari KR, Sullivan TN, Goncy EA. Assessment of in-person and cyber aggression and victimization, substance use, and delinquent behavior during early adolescence. Assessment 2020;27(6):1213-1229. ↵

- Sharma D, Kishore J, Sharma N, Duggal M. Aggression in schools: cyberbullying and gender issues. Asian journal of psychiatry 2017;29:142-145. ↵

- Li Q. Bullying in the new playground: Research into cyberbullying and cyber victimisation. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2007;23(4). ↵

- Hong JS, Kim DH, Thornberg R, Kang JH, Morgan JT. Correlates of direct and indirect forms of cyberbullying victimization involving South Korean adolescents: An ecological perspective. Comput Hum Behav 2018;87:327-336. ↵

- Kwan GCE, Skoric MM. Facebook bullying: An extension of battles in school. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(1):16-25. ↵

- Wong DS, Chan HCO, Cheng CH. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Children and youth services review 2014;36:133-140. ↵

- Solomontos-Kountouri O, Tsagkaridis K, Gradinger P, Strohmeier D. Academic, socio-emotional and demographic characteristics of adolescents involved in traditional bullying, cyberbullying, or both: Looking at variables and persons. International Journal of Developmental Science 2017;11(1-2):19-30. ↵

- Raskauskas J, Stoltz AD. Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Dev Psychol 2007;43(3):564. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Morgan CA, Limber SP. Traditional bullying as a potential warning sign of cyberbullying. School Psychology International 2012;33(5):505-519. ↵

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 2008;49(4):376-385. ↵

- Wright MF, Aoyama I, Kamble SV, Li Z, Soudi S, Lei L, et al. Peer attachment and cyber aggression involvement among Chinese, Indian, and Japanese adolescents. Societies 2015;5(2):339-353. ↵

- Safaria T. Prevalence and impact of cyberbullying in a sample of indonesian junior high school students. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET 2016;15(1):82-91. ↵

- Jose PE, Kljakovic M, Scheib E, Notter O. The joint development of traditional bullying and victimization with cyber bullying and victimization in adolescence. J Res Adolesc 2012;22(2):301-309. ↵

- Mehari KR, Thompson EL, Farrell AD. Differential longitudinal outcomes of in-person and cyber victimization in early adolescence. Psychology of violence 2020;10(4):367. ↵

- i Q. Cyberbullying in schools: A research of gender differences. School psychology international 2006;27(2):157-170. ↵

- Huang Y, Chou C. An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(6):1581-1590. ↵

- Aricak T, Siyahhan S, Uzunhasanoglu A, Saribeyoglu S, Ciplak S, Yilmaz N, et al. Cyberbullying among Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychology & behavior 2008;11(3):253-261. ↵

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2010;41(4):387-397. ↵

- Sourander A, Brunstein Klomek A, Ikonen M,et al. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: A population-based study. Archives of General Psychiatry 2010 July 1;67(7):720-728. ↵

- Perren S, Dooley J, Shaw T, Cross D. Bullying in school and cyberspace: Associations with depressive symptoms in Swiss and Australian adolescents. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health 2010;4(1):1-10. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Prevalence and frequency of Internet harassment instigation: Implications for adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(2):189-195. ↵

- Calvete E, Orue I, Estévez A, Villardón L, Padilla P. Cyberbullying in adolescents: Modalities and aggressors’ profile. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(5):1128-1135. ↵

- Slonje R, Smith PK, Frisén A. The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(1):26-32. ↵

- Beran T, Li Q. Cyber-harassment: A study of a new method for an old behavior. Journal of educational computing research 2005;32(3):265. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Limber SP. Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of adolescent health 2007;41(6):S22-S30. ↵

- Sontag LM, Graber JA, Clemans KH. The role of peer stress and pubertal timing on symptoms of psychopathology during early adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence 2011;40(10):1371-1382. ↵

- Werner NE. Do Hostile Attribution Biases in Children and Parents Predict Relationally Aggressive Behavior? The Journal of genetic psychology 07/2012;173(3):221; 221-245; 245. ↵

- Wade A, Beran T. Cyberbullying: The new era of bullying. Canadian Journal of School Psychology 2011;26(1):44-61. ↵

- Bauman S. Cyberbullying in a rural intermediate school: An exploratory study. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2010;30(6):803-833. ↵

- Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behav 2008;29(2):129-156. ↵

- UNICEF. Child online protection in India. 2017. ↵

- Navarro R, Serna C, Martínez V, Ruiz-Oliva R. The role of Internet use and parental mediation on cyberbullying victimization among Spanish children from rural public schools. European journal of psychology of education 2013;28(3):725-745. ↵

- Casas JA, Del Rey R, Ortega-Ruiz R. Bullying and cyberbullying: Convergent and divergent predictor variables. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(3):580-587. ↵

- Elledge LC, Williford A, Boulton AJ, DePaolis KJ, Little TD, Salmivalli C. Individual and contextual predictors of cyberbullying: The influence of children’s provictim attitudes and teachers’ ability to intervene. Journal of youth and adolescence 2013;42(5):698-710. ↵

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 1993;100(4):674. ↵

- Sasson H, Mesch G. Parental mediation, peer norms and risky online behavior among adolescents. Comput Hum Behav 2014;33:32-38. ↵

- Ang RP, Tan K, Talib Mansor A. Normative beliefs about aggression as a mediator of narcissistic exploitativeness and cyberbullying. J Interpers Violence 2011;26(13):2619-2634. ↵

- Barlett CP, Gentile DA, Anderson CA, Suzuki K, Sakamoto A, Yamaoka A, et al. Cross-cultural differences in cyberbullying behavior: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 2014;45(2):300-313. ↵

- Rahmawati R. Cyberbullying Behavior among Teens Moslem in Pekalongan Indonesia. Proceedings of Universiti Sains Malaysia 2015;238. ↵

- Dang J, Liu L. When peer norms work? Coherent groups facilitate normative influences on cyber aggression. Aggressive Behav 2020;46(6):559-569. ↵

- Badaly D, Kelly BM, Schwartz D, Dabney-Lieras K. Longitudinal associations of electronic aggression and victimization with social standing during adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence 2013;42(6):891-904. ↵

- Katzer C, Fetchenhauer D, Belschak F. Cyberbullying: Who are the victims? A comparison of victimization in Internet chatrooms and victimization in school. Journal of media Psychology 2009;21(1):25-36. ↵

- Schoffstall CL, Cohen R. Cyber aggression: The relation between online offenders and offline social competence. Social Development 2011;20(3):587-604. ↵

- Wright MF, Li Y. The association between cyber victimization and subsequent cyber aggression: The moderating effect of peer rejection. Journal of youth and adolescence 2013;42(5):662-674. ↵

- Jiang Q, Zhao F, Xie X, Wang X, Nie J, Lei L, et al. Difficulties in emotion regulation and cyberbullying among Chinese adolescents: a mediation model of loneliness and depression. J Interpers Violence 2020:0886260520917517. ↵

- Wang P, Wang X, Lei L. Gender differences between student–student relationship and cyberbullying perpetration: An evolutionary perspective. J Interpers Violence 2019:0886260519865970. ↵

- Salmivalli C, Sainio M, Hodges EV. Electronic victimization: Correlates, antecedents, and consequences among elementary and middle school students. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2013;42(4):442-453. ↵

- Doty JL, Gower AL, Sieving RE, Plowman SL, McMorris BJ. Cyberbullying victimization and perpetration, connectedness, and monitoring of online activities: Protection from parental figures. Social Sciences 2018;7(12):265. ↵

- Chan HC, Wong DS. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying perpetration: Examining the psychosocial characteristics of Hong Kong male and female adolescents. Youth & Society 2019;51(1):3-29. ↵

- Gaffney H, Farrington DP, Espelage DL, Ttofi MM. Are cyberbullying intervention and prevention programs effective? A systematic and meta-analytical review. Aggression and violent behavior 2019;45:134-153. ↵

- Doty JL, Giron K, Mehari KR, Sharma D, Smith SJ, Su Y, et al. Interventions to Prevent Cyberbullying Perpetration and Victimization: A Systematic Review. Prevention Science in press. ↵

- Pearce N, Cross D, Monks H, Waters S, Falconer S. Current evidence of best practice in whole-school bullying intervention and its potential to inform cyberbullying interventions. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools 2011;21(1):1-21. ↵

- Gonzales J, Mehari KR. Attitudes about Cyber Intimate Partner Violence: Scale Development and Preliminary Psychometrics. 2021. ↵

- Sharma D, Mehari KR, Doty JL. Stakeholder Focus Groups on Cyberbullying in India. 2021. ↵

- Willard NE. The authority and responsibility of school officials in responding to cyberbullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(6):S64-S65. ↵

- Agatston PW, Kowalski R, Limber S. Students’ perspectives on cyber bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(6):S59-S60. ↵

- Slonje R, Smith PK. Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scand J Psychol 2008;49(2):147-154. ↵

- Cassidy W, Brown K, Jackson M. “Making Kind Cool”: Parents’ Suggestions for Preventing Cyber Bullying and Fostering Cyber Kindness. Journal of Educational Computing Research 2012;46(4):415-436. ↵

- Hodges EV, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM. The power of friendship: protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Dev Psychol 1999;35(1):94. ↵

- Hertz MF, David-Ferdon C. Electronic media and youth violence: A CDC issue brief for educators and caregivers. : Centers for Disease Control Atlanta, GA; 2008. ↵

- Horner RH, Sugai G. School-wide PBIS: An example of applied behavior analysis implemented at a scale of social importance. Behavior analysis in practice 2015;8(1):80-85. ↵

- Shariff S. Confronting Cyber-Bullying: What Schools Need to Know to Control Misconduct and Avoid Legal Consequences. : ERIC; 2009. ↵

Cyberbullying and Digital Safety: Applying Global Research to Youth in India Copyright © 2022 by Krista Mehari and Natasha Basu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Methods: Guiding Principles

- Disability and Psychoeducation Studies

- Family and Consumer Sciences, School of

Research output : Chapter in Book/Report/Conference proceeding › Chapter

In this chapter, we propose five principles to serve as guidelines for cyberbullying research methods: engaging multidisciplinary teams, using a broad selection of quality methods, understanding the importance of formative research, realizing the value of target audience involvement, and promoting ethical practice in online environments. We do not describe these guidelines as “best practice, " as there is insufficient evidence to date that these methods (some of which are unique to measure cyberbullying behavior) produce superior results. Nevertheless, considering what is known about research in general and research on aggression; victimization; and bullying, in particular, we believe these principles are grounded in sound scientific methods and fundamental beliefs about the research enterprise. We are also mindful that scientific inquiry into the use of technology is a relatively new area, and we have taken this into account in our recommendations.

ASJC Scopus subject areas

- General Psychology

Access to Document

- 10.4324/9780203084601-24

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Cyberbullying Medicine & Life Sciences 100%

- Bullying Medicine & Life Sciences 39%

- Crime Victims Medicine & Life Sciences 38%

- Guidelines Medicine & Life Sciences 38%

- victimization Social Sciences 32%

- aggression Social Sciences 31%

- Aggression Medicine & Life Sciences 30%

- research method Social Sciences 29%

T1 - Methods

T2 - Guiding Principles

AU - Bauman, Sheri

AU - Cross, Donna

N1 - Publisher Copyright: © 2013 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

PY - 2012/1/1

Y1 - 2012/1/1

N2 - In this chapter, we propose five principles to serve as guidelines for cyberbullying research methods: engaging multidisciplinary teams, using a broad selection of quality methods, understanding the importance of formative research, realizing the value of target audience involvement, and promoting ethical practice in online environments. We do not describe these guidelines as “best practice, " as there is insufficient evidence to date that these methods (some of which are unique to measure cyberbullying behavior) produce superior results. Nevertheless, considering what is known about research in general and research on aggression; victimization; and bullying, in particular, we believe these principles are grounded in sound scientific methods and fundamental beliefs about the research enterprise. We are also mindful that scientific inquiry into the use of technology is a relatively new area, and we have taken this into account in our recommendations.

AB - In this chapter, we propose five principles to serve as guidelines for cyberbullying research methods: engaging multidisciplinary teams, using a broad selection of quality methods, understanding the importance of formative research, realizing the value of target audience involvement, and promoting ethical practice in online environments. We do not describe these guidelines as “best practice, " as there is insufficient evidence to date that these methods (some of which are unique to measure cyberbullying behavior) produce superior results. Nevertheless, considering what is known about research in general and research on aggression; victimization; and bullying, in particular, we believe these principles are grounded in sound scientific methods and fundamental beliefs about the research enterprise. We are also mindful that scientific inquiry into the use of technology is a relatively new area, and we have taken this into account in our recommendations.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85121888210&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=85121888210&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.4324/9780203084601-24

DO - 10.4324/9780203084601-24

M3 - Chapter

AN - SCOPUS:85121888210

SN - 9780415897495

BT - Principles of Cyberbullying Research

PB - Taylor and Francis

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Teens and Cyberbullying 2022

- Methodology

Table of Contents

- Age and gender are related to teens’ cyberbullying experiences, with older teen girls being especially likely to face this abuse

- Black teens are about twice as likely as Hispanic or White teens to say they think their race or ethnicity made them a target of online abuse

- Black or Hispanic teens are more likely than White teens to say cyberbullying is a major problem for people their age

- Roughly three-quarters of teens or more think elected officials and social media sites aren’t adequately addressing online abuse

- Large majorities of teens believe permanent bans from social media and criminal charges can help reduce harassment on the platforms

- Acknowledgments

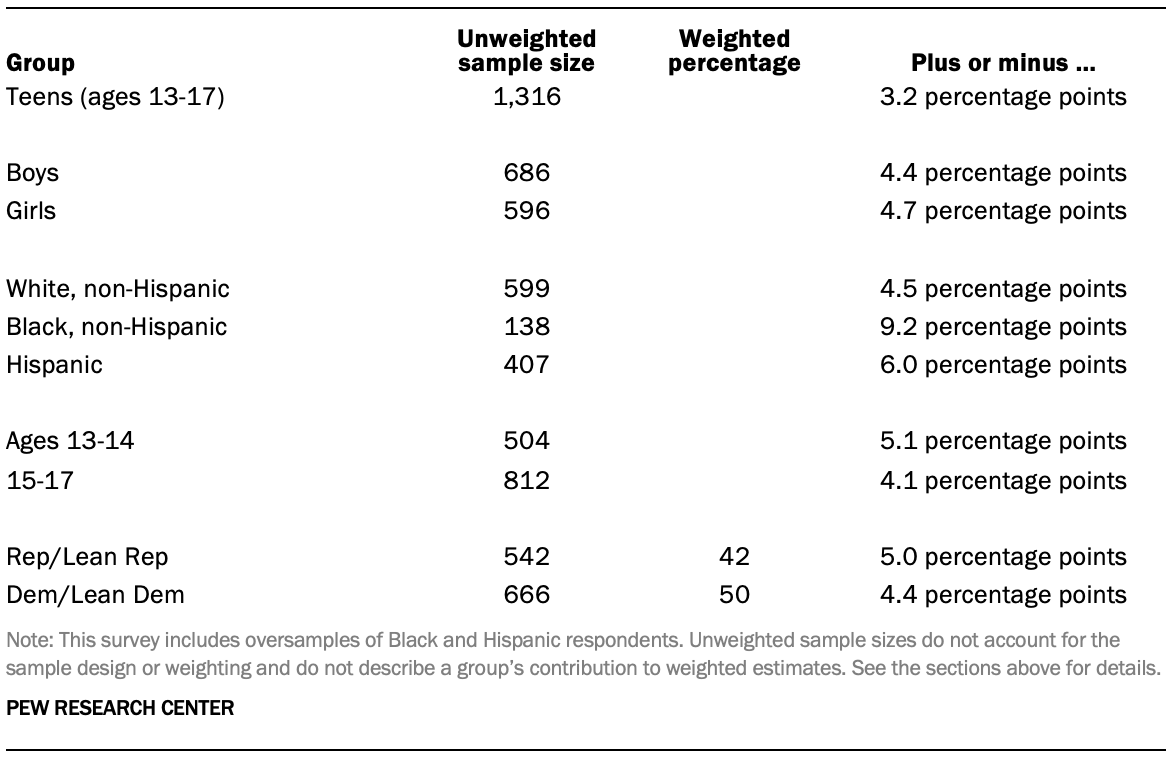

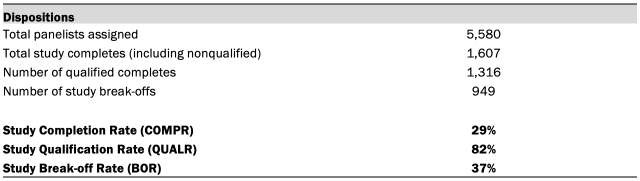

The analysis in this report is based on a self-administered web survey conducted from April 14 to May 4, 2022, among a sample of 1,316 dyads, with each dyad (or pair) comprised of one U.S. teen ages 13 to 17 and one parent per teen. The margin of sampling error for the full sample of 1,316 teens is plus or minus 3.2 percentage points. The survey was conducted by Ipsos Public Affairs in English and Spanish using KnowledgePanel, its nationally representative online research panel.

The research plan for this project was submitted to an external institutional review board (IRB), Advarra, which is an independent committee of experts that specializes in helping to protect the rights of research participants. The IRB thoroughly vetted this research before data collection began. Due the risks associated with surveying minors, this research underwent a full board review and received approval (Pro00060166).

KnowledgePanel members are recruited through probability sampling methods and include both those with internet access and those who did not have internet access at the time of their recruitment. KnowledgePanel provides internet access for those who do not have it and, if needed, a device to access the internet when they join the panel. KnowledgePanel’s recruitment process was originally based exclusively on a national random-digit-dialing (RDD) sampling methodology. In 2009, Ipsos migrated to an address-based sampling (ABS) recruitment methodology via the U.S. Postal Service’s Delivery Sequence File (DSF). The Delivery Sequence File has been estimated to cover as much as 98% of the population, although some studies suggest that the coverage could be in the low 90% range. 3

Panelists were eligible for participation in this survey if they indicated on an earlier profile survey that they were the parent of a teen ages 13 to 17. A random sample of 5,580 eligible panel members were invited to participate in the study. Responding parents were screened and considered qualified for the study if they reconfirmed that they were the parent of at least one child ages 13 to 17 and granted permission for their teen who was chosen to participate in the study. In households with more than one eligible teen, parents were asked to think about one randomly selected teen and that teen was instructed to complete the teen portion of the survey. A survey was considered complete if both the parent and selected teen completed their portions of the questionnaire, or if the parent did not qualify during the initial screening.

Of the sampled panelists, 1,607 (excluding break-offs) responded to the invitation and 1,316 qualified, completed the parent portion of the survey, and had their selected teen complete the teen portion of the survey yielding a final stage completion rate of 29% and a qualification rate of 82%. 4 The cumulative response rate accounting for nonresponse to the recruitment surveys and attrition is 1%. The break-off rate among those who logged on to the survey (regardless of whether they completed any items or qualified for the study) is 37%.

Upon completion, qualified respondents received a cash-equivalent incentive worth $10 for completing the survey.

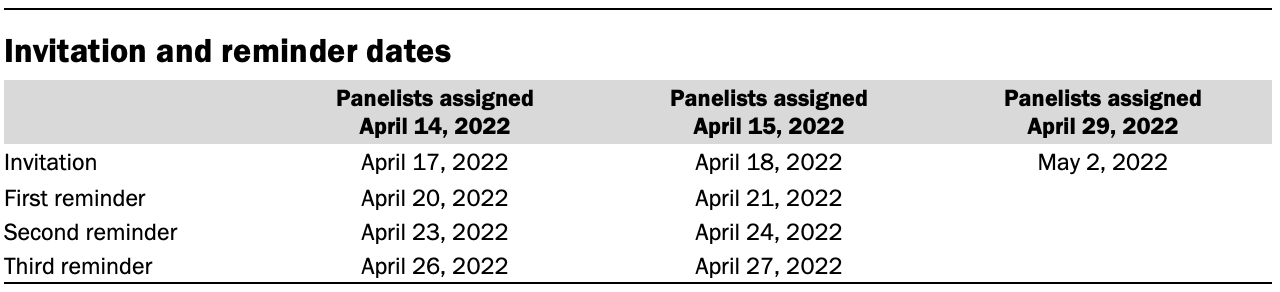

Panelists were assigned to take the survey in batches. Email invitations and reminders were sent to panelists according to a schedule based on when they were assigned this survey in their personalized member portal, shown in the table below. The field period was closed on May 4, 2022, and thus no further email contacts past the invitation were sent for the final set of panelists.

The analysis in this report was performed using a teen weight. A weight for parents was also constructed, forming the basis of the teen weight. The parent weight was created in a multistep process that begins with a base design weight for the parent, which is computed to reflect their probability of selection for recruitment into the KnowledgePanel. These selection probabilities were then adjusted to account for the probability of selection for this survey, which included oversamples of Black and Hispanic parents. Next, an iterative technique was used to align the parent design weights to population benchmarks for parents of teens ages 13 to 17 on the dimensions identified in the accompanying table to account for any differential nonresponse that may have occurred.

To create the teen weight, an adjustment factor was applied to the final parent weight to reflect the selection of one teen per household. Finally, the teen weights were further raked to match the demographic distribution for teens ages 13 to 17 who live with parents. The teen weights were adjusted on the same teen dimensions as parent dimensions with the exception of teen education, which was not used in the teen weighting.

Sampling errors and tests of statistical significance take into account the effect of weighting. Interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish.

In addition to sampling error, one should bear in mind that question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of opinion polls.

The following tables show the unweighted sample sizes and the error attributable to sampling that would be expected at the 95% level of confidence for different groups in the survey:

Sample sizes and sampling errors for other subgroups are available upon request.

Dispositions and response rates

The tables below display dispositions used in the calculation of completion, qualification and cumulative response rates. 5

- AAPOR Task force on Address-based Sampling. 2016. “AAPOR Report: Address-based Sampling.” ↩

- The 1,316 qualified and completed interviews exclude seven cases that were dropped because respondents did not answer one-third or more of the survey questions. ↩

- For more information on this method of calculating response rates, see Callegaro, Mario & DiSogra, Charles. 2008. “Computing response metrics for online panels.” Public Opinion Quarterly 72(5). pp. 1008-1032. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Online Harassment & Bullying

- Teens & Tech

- Teens & Youth

Teens and Video Games Today

9 facts about bullying in the u.s., life on social media platforms, in users’ own words, after musk’s takeover, big shifts in how republican and democratic twitter users view the platform, the behaviors and attitudes of u.s. adults on twitter, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Defining cyberbullying: A qualitative research into the perceptions of youngsters

2008, CyberPsychology & …

Related Papers

New media & society

Heidi Vandebosch

Hapindi Arista

Psychological Bulletin

Amber Schroeder

Zeitschrift Fur Psychologie-journal of Psychology

Jacek Pyzalski

Zeitschrift für Psychologie / Journal of Psychology

Jacek Pyzalski , Julian Dooley

Haley Burgess , Mitchell Hobbs

Cyberbullying is a relatively recent phenomenon that can have significant consequences for young people’s wellbeing due to the specific technological affordances of social media. To date, research into cyberbullying has been largely quantitative; thus, it often elides the complexity of the issue. Moreover, most studies have been “top down,” excluding young people’s views. Our qualitative research findings suggest that young people engage in cyberbullying to accrue social benefits over peers and to manage social pressures and anxiety, while cultural conventions in gender performance see girls engage differently in cyberbullying. We conclude that cyberbullying, like offline bullying, is a socially constructed behavior that provides both pleasure and pain.

International Journal of Consumer Studies

Carrie La Ferle

Cyberbullying in the digital sphere has impacted individuals of all age groups. Recent findings indicate an increase in suicidal tendencies among victims. An opportunity to prevent cyberbullying exists in the actions of bystanders. The current study proposes the possible impact of religion (Christianity) in motivating bystanders to aid victims of abuse. Using an experimental design, the research explored the interplay of individual religiosity and religious symbolism on American bystanders’ ad attitudes and intentions to call a helpline. Findings indicate a congruency effect for low religiosity individuals between the control and religious ads. High religiosity individuals liked both ads equally well, but within the religious ad, again a congruency effect appeared where highly religious individuals found the religious ad significantly more appealing than low religious individuals. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Mitchell Hobbs

Peter Smith , Sonia Livingstone

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry

Sonia Livingstone

RELATED PAPERS

Georges Steffgen , trijntje vollink , francine dehue

Sameer Hinduja , Justin W . Patchin

Jacek Pyzalski , Camilla Hällgren

Aggressive Behavior

Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling

Anja Schultze-krumbholz

Barbara Spears

Education and Information Technologies

Tali Heiman

Rizalyn Castillo

Gilberto Marzano

Conor Guckin

Behaviour & Information Technology

Computers in Human Behavior

Gayle Brewer

Calvin Dota

wesley bruce

Katie Davis , Carrie James

Triantoro Safaria , Triantoro Safaria

francine dehue

Scandinavian journal of psychology

Rita Zukauskiene

Ray Block , Laurie Cooper Stoll

Sora Park , Jee Young Lee , Soeun Yang

Http Dx Doi Org 10 1080 15388220 2012 762921

Rivka Witenberg

glenda reyes

Pedro Ferraz de Abreu

Giulia Mura

Journal of School Violence

Emma-Kate Corby , phillip slee

Toks Dele Oyedemi

Nicholas Brody

Lilian Lechner

Studies in health technology and informatics

Cigdem Topcu

Michel Walrave

Tiffany Jones

The western journal of emergency medicine

Joel Meyers , Kris Varjas

Łukasz Tomczyk

Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

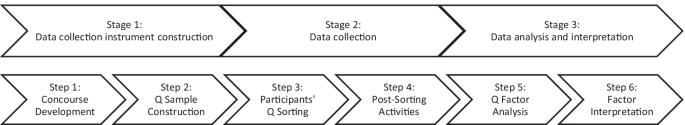

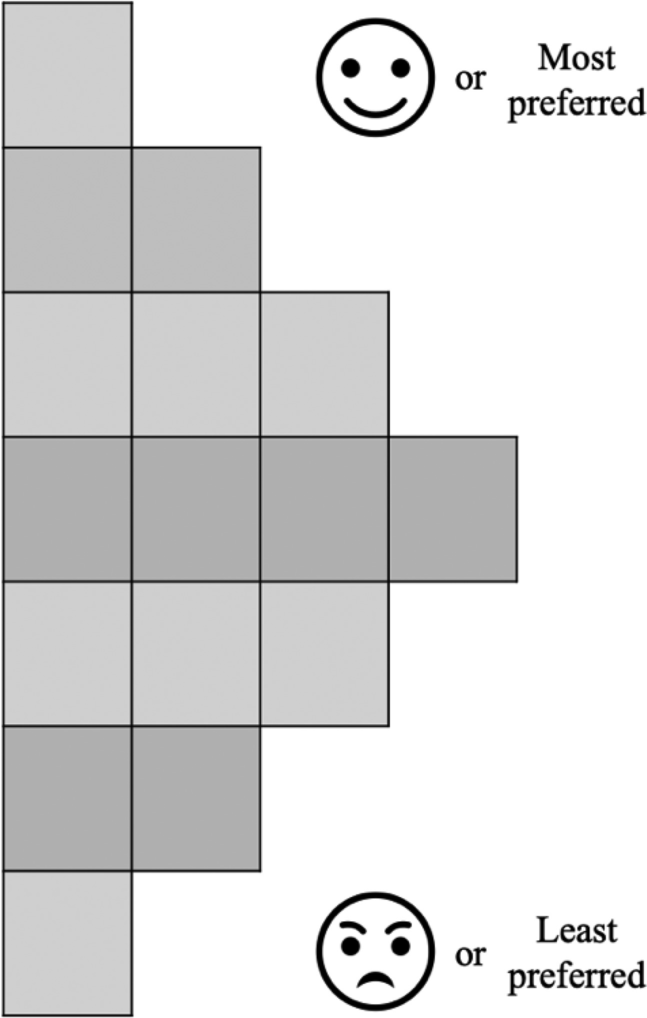

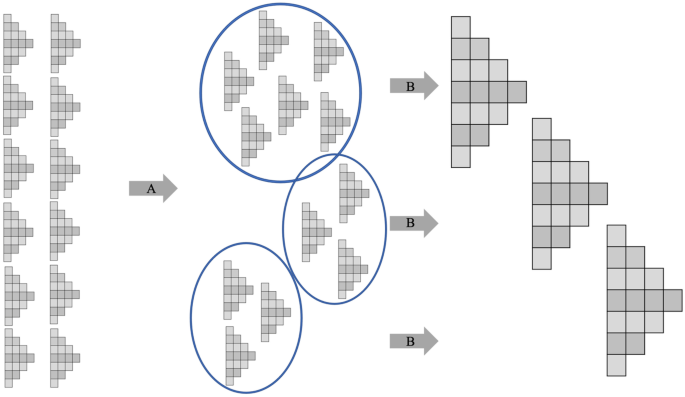

Q Methodology as an Innovative Addition to Bullying Researchers’ Methodological Repertoire

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 May 2022

- Volume 4 , pages 209–219, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Adrian Lundberg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8555-6398 1 &

- Lisa Hellström ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9326-1175 1

6388 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 18 July 2022

This article has been updated

The field of bullying research deals with methodological issues and concerns affecting the comprehension of bullying and how it should be defined. For the purpose of designing relevant and powerful bullying prevention strategies, this article argues that instead of pursuing a universal definition of what constitutes bullying, it may be of greater importance to investigate culturally and contextually bound understandings and definitions of bullying. Inherent to that shift is the transition to a more qualitative research approach in the field and a stronger focus on participants’ subjective views and voices. Challenges in qualitative methods are closely connected to individual barriers of hard-to-reach populations and the lack of a necessary willingness to share on the one hand and the required ability to share subjective viewpoints on the other hand. By reviewing and discussing Q methodology, this paper contributes to bullying researchers’ methodological repertoire of less-intrusive methodologies. Q methodology offers an approach whereby cultural contexts and local definitions of bullying can be put in the front. Furthermore, developmentally appropriate intervention and prevention programs might be created based on exploratory Q research and could later be validated through large-scale investigations. Generally, research results based on Q methodology are expected to be useful for educators and policymakers aiming to create a safe learning environment for all children. With regard to contemporary bullying researchers, Q methodology may open up novel possibilities through its status as an innovative addition to more mainstream approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Using Qualitative Methods to Measure and Understand Key Features of Adolescent Bullying: A Call to Action

The importance of being attentive to social processes in school bullying research: adopting a constructivist grounded theory approach.

Problems and Coping Strategies in Conducting Comparative Research in School Bullying Between China and Norway

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bullying, internationally recognized as a problematic and aggressive form of behavior, has negative effects, not only for those directly involved but for anybody and in particular children in the surrounding environment (Modin, 2012 ). However, one of the major concerns among researchers in the field of bullying is the type of research methods employed in the studies on bullying behavior in schools. The appropriateness of using quantitative or qualitative research methods rests on the assumption of the researcher and the nature of the phenomena under investigation (Hong & Espelage, 2012 ). There is a need for adults to widen their understanding and maintain a focus on children’s behaviors to be able to provide assistance and support in reducing the amount of stress and anxiety resulting from online and offline victimization (Hellström & Lundberg, 2020 ). A crucial step for widening this understanding is an increased visibility of children’s own viewpoints. When the voices of children, particularly those of victims and perpetrators, but also those of bystanders are heard in these matters, effective support can be designed based specifically on what children want and need rather than what adults interpret and understand to be supporting the child (O’Brien, 2019 ). However, bullying victims and their perpetrators are hard-to-reach populations (Shaghaghi et al., 2011 ; Sydor, 2013 ) for a range of reasons. To name but a few, researchers perennially face difficulties regarding potential participants’ self-identification, the sensitivity of bullying topics, or the power imbalance between them and their young respondents. Furthermore, limited verbal literacy and/or a lack of cognitive ability of some respondents due to age or disability contribute to common methodological issues in the field. Nevertheless, and despite ethical restrictions around the immediate questioning of younger children or children with disabilities that prohibit researchers to perform the assessments with them directly, it would be ethically indefensible to not study a sensitive topic like bullying among vulnerable groups of children. Hence, the research community is responsible for developing valid and reliable methods to explore bullying among different groups of children, where the children’s own voices are heard and taken into account (Hellström, 2019 ). Consequently, this paper aims to contribute to bullying researchers’ methodological repertoire with an additional less-intrusive methodology, particularly suitable for research with hard-to-reach populations.

Historically, the field of bullying and cyberbullying has been dominated by quantitative research approaches, most often with the aim to examine prevalence rates. However, recent research has seen an increase in the use of more qualitative and multiple data collection approaches on how children and youth explain actions and reactions in bullying situations (e.g., Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021 ; Eriksen & Lyng, 2018 ; Patton et al., 2017 ). This may be translated into a need to more clearly understand the phenomenon in different contexts. As acknowledged by many researchers, bullying is considerably influenced by the context in which it occurs and the field is benefitting from studying the phenomenon in the setting where all the contextual variables are operating (see, e.g., Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021 ; Scheithauer et al., 2016 ; Torrance, 2000 ). Cultural differences in attitudes regarding violence as well as perceptions, attitudes, and values regarding bullying are likely to exist and have an impact when bullying is being studied. For this reason, listening to the voices of children and adolescents when investigating the nature of bullying in different cultures is essential (Hellström & Lundberg, 2020 ; Scheithauer et al., 2016 ).

In addition to studying outcomes or products, bullying research has also emphasized the importance of studying processes (Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021 ). Here, the use of qualitative methods allows scholars to not only explore perceptions and understandings of bullying and its characteristics, but also interpret bullying in light of a specific social context, presented from a specific internal point of view. In other words, qualitative approaches may offer methods to understand how people make sense of their experiences of the bullying phenomenon. The processes implemented by a qualitative approach allow researchers to build hypotheses and theories in an inductive way (Atieno, 2009 ). Thus, a qualitative approach can enrich quantitative knowledge of the bullying phenomenon, paying attention to the significance that individuals attribute to situations and their own experiences. It can allow the research and clinical community to better project and implement bullying assessment and prevention programs (Hutson, 2018 ).

Instead of placing qualitative and quantitative approaches in opposition, they can both be useful and complementary, depending on the purpose of the research (Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021 ). In their review of mixed methods research on bullying and peer victimization in school, Hong and Espelage ( 2012 ) underlined that instead of using single methods, mixed methods have the advantage of generating a deeper and more complex understanding of the phenomenon. By combining objective data with information about the personal context within which the phenomenon occurs, mixed methods can generate new insights and new perspectives to the research field (Hong & Espelage, 2012 ; Kulig et al., 2008 ; Pellegrini & Long, 2002 ). However, Hong and Espelage ( 2012 ) also argued that mixed methods can lead to divergence and contradictions in findings that may serve as a challenge to researchers. For example, Cowie and Olafsson ( 2000 ) examined the impact of a peer support program to reduce bullying using both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. While a quantitative approach collecting pre-test and post-test data showed no effects in decreasing bullying, interviews with peer supporters, students, and potential users of the intervention revealed the strength of the program and its positive impact, in light of students and peer supporters. Thus, rather than rejecting the program, the divergence in findings leads to a new rationale for modifying the program and addressing its limits.

Understandably, no single data collection approach is complete but deals with methodological issues and concerns affecting the research field and the comprehension of bullying. To provide a robust foundation for the introduction of an additional methodological perspective in bullying research, common data collection methods and methodological issues are outlined below.

Methodological Issues in Bullying Research

Large-scale cohort studies generating statistical findings often use R-statistics, descriptive analyses, averages, and correlations to estimate and compare prevalence rates of bullying, to explore personality traits of bullies and victims, and the main correlates and predictors of the phenomenon. Nevertheless, large-scale surveys have a harder time examining why bullying happens (O’Brian, 2019 ) and usually do not give voice to study objects’ own unique understanding and experiences (Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021 ; Bosacki et al., 2006 ; Woodhead & Faulkner, 2008 ). Other concerns using large-scale surveys include whether a definition is used or the term bullying is operationalized, which components are included in the definition, what cut-off points for determining involvement are being used, the lack of reliability information, and the absence of validity studies (Swearer et al., 2010 ).

Other issues include the validity in cross-cultural comparisons using large-scale surveys. For example, prevalence rates across Europe are often established using standard questionnaires that have been translated into appropriate languages. Comparing four large-scale surveys, Smith et al. ( 2016 ) found that when prevalence rates by country are compared across surveys, there are some obvious discrepancies, which suggest a need to examine systematically how these surveys compare in measuring cross-national differences. Low external validity rates between these studies raise concerns about using these cross-national data sets to make judgments about which countries are higher or lower in victim rates. The varying definitions and words used in bullying research may make it difficult to compare findings from studies conducted in different countries and cultures (Griffin & Gross, 2004 ). However, some argue that the problem seems to be more about inconsistency in the type of assessments (e.g., self-report, nominations) used to measure bullying rather than the varying definition of bullying (Jia & Mikami, 2018 ). When using a single-item approach (e.g., “How often have you been bullied?”) it is not possible to investigate the equivalency of the constructs between countries, which is a crucial precondition for any statistically valid comparison between them (Scheithauer et al., 2016 ). Smith et al. ( 2016 ) conclude that revising definitions and how bullying is translated and expressed in different languages and contexts would help examine comparability between countries.

Interviews, focus groups and the use of vignettes (usually with younger children) can all be regarded as suitable when examining youths’ perceptions of the bullying phenomenon (Creswell, 2013 ; Hellström et al., 2015 ; Hutson, 2018 ). They all allow an exploration of the bullying phenomenon within a social context taking into consideration the voices of children and might solve some of the methodological concerns linked to large-scale surveys. However, these data collection methods are also challenged by individual barriers of hard-to-reach populations (Ellard-Gray et al., 2015 ) and may include the lack of a necessary willingness to share on the one hand and the required ability to share subjective viewpoints on the other hand.

Willingness to Share

In contrast to large-scale surveys requiring large samples of respondents with reasonable literacy skills, interviews, which may rely even heavier on students’ verbal skills, are less plentiful in bullying research. This might at least partially be based on a noteworthy expectation of respondents to be willing to share something. It must be remembered that asking students to express their own or others’ experiences of emotionally charged situations, for example concerning bullying, is particularly challenging (Khanolainen & Semenova, 2020 ) and can be perceived as intrusive by respondents who have not had the opportunity to build a rapport with the researchers. This constitutes a reason why research in this important area is difficult and complex to design and perform. Ethnographic studies may be considered less intrusive, as observations offer a data collection technique where respondents are not asked to share any verbal information or personal experiences. However, ethnographical studies are often challenging due to the amount of time, resources, and competence that are required by the researchers involved (Queirós et al., 2017 ). In addition, ethnographical studies are often used for other purposes than asking participants to share their views on certain topics.

Vulnerable populations often try to avoid participating in research about a sensitive topic that is related to their vulnerable status, as recalling and retelling painful experiences might be distressing. The stigma surrounding bullying may affect children’s willingness to share their personal experiences in direct approaches using the word bullying (Greif & Furlong, 2006 ). For this reason, a single-item approach, in which no definition of bullying is provided, allows researchers to ask follow-up questions about perceptions and contexts and enables participants to enrich the discussion by adjusting their answers based on the suggestions and opinions of others (Jacobs et al., 2015 ). Generally, data collection methods with depersonalization and distancing effects have proven effective in research studying sensitive issues such as abuse, trauma, stigma and so on (e.g., Cromer & Freyd, 2009 ; Hughes & Huby, 2002 ). An interesting point raised by Jacobs and colleagues ( 2015 ) is that a direct approach that asks adolescents if they have ever experienced cyberbullying may lead to a poorer discussion and an underestimation of the phenomenon. This is because perceptions and contexts often differ between persons and because adolescents do not perceive all behaviors as cyberbullying. The same can be true for bullying taking place offline (Hellström et al., 2015 ).