- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter

- Heidi Grant

Research shows they’re more successful in three important ways.

Striving to increase workplace diversity is not an empty slogan — it is a good business decision. A 2015 McKinsey report on 366 public companies found that those in the top quartile for ethnic and racial diversity in management were 35% more likely to have financial returns above their industry mean, and those in the top quartile for gender diversity were 15% more likely to have returns above the industry mean.

- DR David Rock is cofounder of the Neuroleadership Institute and author of Your Brain at Work .

- Heidi Grant is a social psychologist who researches, writes, and speaks about the science of motivation. Her most recent book is Reinforcements: How to Get People to Help You . She’s also the author of Nine Things Successful People Do Differently and No One Understands You and What to Do About It . She is EY US Director of Learning R&D.

Partner Center

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How Diversity Makes Us Smarter

The first thing to acknowledge about diversity is that it can be difficult.

In the U.S., where the dialogue of inclusion is relatively advanced, even the mention of the word “diversity” can lead to anxiety and conflict. Supreme Court justices disagree on the virtues of diversity and the means for achieving it. Corporations spend billions of dollars to attract and manage diversity both internally and externally, yet they still face discrimination lawsuits, and the leadership ranks of the business world remain predominantly white and male.

It is reasonable to ask what good diversity does us. Diversity of expertise confers benefits that are obvious—you would not think of building a new car without engineers, designers, and quality-control experts—but what about social diversity? What good comes from diversity of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation? Research has shown that social diversity in a group can cause discomfort, rougher interactions, a lack of trust, greater perceived interpersonal conflict, lower communication, less cohesion, more concern about disrespect, and other problems. So, what is the upside?

The fact is that if you want to build teams or organizations capable of innovating, you need diversity. Diversity enhances creativity. It encourages the search for novel information and perspectives, leading to better decision making and problem solving. Diversity can improve the bottom line of companies and lead to unfettered discoveries and breakthrough innovations. Even simply being exposed to diversity can change the way you think.

This is not just wishful thinking: It is the conclusion I draw from decades of research from organizational scientists, psychologists, sociologists, economists, and demographers.

Informational diversity fuels innovation

The key to understanding the positive influence of diversity is the concept of informational diversity. When people are brought together to solve problems in groups, they bring different information, opinions, and perspectives.

This makes obvious sense when we talk about diversity of disciplinary backgrounds—think again of the interdisciplinary team building a car. The same logic applies to social diversity. People who are different from one another in race, gender, and other dimensions bring unique information and experiences to bear on the task at hand. A male and a female engineer might have perspectives as different from one another as an engineer and a physicist—and that is a good thing.

“We need diversity if we are to change, grow, and innovate”

Research on large, innovative organizations has shown repeatedly that this is the case.

For example, business professors Cristian Deszö of the University of Maryland and David Ross of Columbia University studied the effect of gender diversity on the top firms in Standard & Poor’s Composite 1500 list, a group designed to reflect the overall U.S. equity market. First, they examined the size and gender composition of firms’ top management teams from 1992 through 2006. Then they looked at the financial performance of the firms. In their words, they found that, on average, “female representation in top management leads to an increase of $42 million in firm value.” They also measured the firms’ “innovation intensity” through the ratio of research and development expenses to assets. They found that companies that prioritized innovation saw greater financial gains when women were part of the top leadership ranks.

Racial diversity can deliver the same kinds of benefits. In a study conducted in 2003, Orlando Richard, a professor of management at the University of Texas at Dallas, and his colleagues surveyed executives at 177 national banks in the U.S., then put together a database comparing financial performance, racial diversity, and the emphasis the bank presidents put on innovation. For innovation-focused banks, increases in racial diversity were clearly related to enhanced financial performance.

Of course, not all studies get the same results. Even those that haven’t found benefits for racially diverse firms suggest that there is certainly no negative financial impact—and there are benefits that may go beyond the short-term bottom line. For example, in a paper published in June of this year , researchers examined the financial performance of firms listed in DiversityInc ’s list of Top 50 Companies for Diversity. They found the companies on the list did outperform the S&P 500 index—but the positive impact disappeared when researchers accounted for the size of the firms. That doesn’t mean diversity isn’t worth pursuing, conclude the authors:

In an age of increasing globalization, a diverse workforce may provide both tangible and intangible benefits to firms over the long run, including increased adaptability in a changing market. Also, as the United States moves towards the point in which no ethnic majority exists, around 2050, companies’ upper management and lower-level workforce should naturally be expected to reflect more diversity. Consequently, diversity initiatives would likely generate positive reputation effects for firms.

Evidence for the benefits of diversity can be found well beyond the U.S. In August 2012, a team of researchers at the Credit Suisse Research Institute issued a report in which they examined 2,360 companies globally from 2005 to 2011, looking for a relationship between gender diversity on corporate management boards and financial performance. Sure enough, the researchers found that companies with one or more women on the board delivered higher average returns on equity, lower gearing (that is, net debt to equity), and better average growth.

How diversity provokes new thinking

More on diversity.

Read about the meaning and benefits of diversity .

Discover how students benefit from school diversity .

Learn about the neuroscience of prejudice .

Explore the top ten strategies for reducing prejudice .

Large data-set studies have an obvious limitation: They only show that diversity is correlated with better performance, not that it causes better performance. Research on racial diversity in small groups, however, makes it possible to draw some causal conclusions. Again, the findings are clear: For groups that value innovation and new ideas, diversity helps.

In 2006, I set out with Margaret Neale of Stanford University and Gregory Northcraft of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to examine the impact of racial diversity on small decision-making groups in an experiment where sharing information was a requirement for success.

Our subjects were undergraduate students taking business courses at the University of Illinois. We put together three-person groups—some consisting of all white members, others with two whites and one nonwhite member—and had them perform a murder mystery exercise. We made sure that all group members shared a common set of information, but we also gave each member important clues that only they knew. To find out who committed the murder, the group members would have to share all the information they collectively possessed during discussion. The groups with racial diversity significantly outperformed the groups with no racial diversity. Being with similar others leads us to think we all hold the same information and share the same perspective. This perspective, which stopped the all-white groups from effectively processing the information, is what hinders creativity and innovation.

Other researchers have found similar results. In 2004, Anthony Lising Antonio, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education, collaborated with five colleagues from the University of California, Los Angeles, and other institutions to examine the influence of racial and opinion composition in small group discussions. More than 350 students from three universities participated in the study. Group members were asked to discuss a prevailing social issue (either child labor practices or the death penalty) for 15 minutes. The researchers wrote dissenting opinions and had both black and white members deliver them to their groups. When a black person presented a dissenting perspective to a group of whites, the perspective was perceived as more novel and led to broader thinking and consideration of alternatives than when a white person introduced that same dissenting perspective .

The lesson: When we hear dissent from someone who is different from us, it provokes more thought than when it comes from someone who looks like us. It’s a result echoed by a longitudinal study published last year, which tracked the moral development of students on 17 campuses who took a class on diversity in their freshman year. The analysis led the researchers to a robust conclusion: Students who were trained to negotiate diversity from the beginning showed much more sophisticated moral reasoning by the time they graduated. This was especially true for students who entered with lower academic ability.

Active Listening

Connect with a partner through empathy and understanding.

This effect is not limited to race and gender. For example, last year professors of management Denise Lewin Loyd of the University of Illinois, Cynthia Wang of Oklahoma State University, Robert B. Lount, Jr., of Ohio State University, and I asked 186 people whether they identified as a Democrat or a Republican, then had them read a murder mystery and decide who they thought committed the crime. Next, we asked the subjects to prepare for a meeting with another group member by writing an essay communicating their perspective. More important, in all cases, we told the participants that their partner disagreed with their opinion but that they would need to come to an agreement with the other person. Everyone was told to prepare to convince their meeting partner to come around to their side; half of the subjects, however, were told to prepare to make their case to a member of the opposing political party, and half were told to make their case to a member of their own party.

The result: Democrats who were told that a fellow Democrat disagreed with them prepared less well for the discussion than Democrats who were told that a Republican disagreed with them. Republicans showed the same pattern. When disagreement comes from a socially different person, we are prompted to work harder. Diversity jolts us into cognitive action in ways that homogeneity simply does not.

For this reason, diversity appears to lead to higher-quality scientific research.

In 2014, two Harvard University researchers examined the ethnic identity of the authors of 1.5 million scientific papers written between 1985 and 2008 using Thomson Reuters’s Web of Science, a comprehensive database of published research. They found that papers written by diverse groups receive more citations and have higher impact factors than papers written by people from the same ethnic group. Moreover, they found that stronger papers were associated with a greater number of author addresses; geographical diversity, and a larger number of references, is a reflection of more intellectual diversity.

What we believe makes a difference

Diversity is not only about bringing different perspectives to the table. Simply adding social diversity to a group makes people believe that differences of perspective might exist among them and that belief makes people change their behavior.

Members of a homogeneous group rest somewhat assured that they will agree with one another; that they will understand one another’s perspectives and beliefs; that they will be able to easily come to a consensus.

But when members of a group notice that they are socially different from one another, they change their expectations. They anticipate differences of opinion and perspective. They assume they will need to work harder to come to a consensus. This logic helps to explain both the upside and the downside of social diversity: People work harder in diverse environments both cognitively and socially. They might not like it, but the hard work can lead to better outcomes.

In a 2006 study of jury decision making, social psychologist Samuel Sommers of Tufts University found that racially diverse groups exchanged a wider range of information during deliberation about a sexual assault case than all-white groups did. In collaboration with judges and jury administrators in a Michigan courtroom, Sommers conducted mock jury trials with a group of real selected jurors. Although the participants knew the mock jury was a court-sponsored experiment, they did not know that the true purpose of the research was to study the impact of racial diversity on jury decision making.

Sommers composed the six-person juries with either all white jurors or four white and two black jurors. As you might expect, the diverse juries were better at considering case facts, made fewer errors recalling relevant information, and displayed a greater openness to discussing the role of race in the case.

These improvements did not necessarily happen because the black jurors brought new information to the group—they happened because white jurors changed their behavior in the presence of the black jurors. In the presence of diversity, they were more diligent and open-minded.

Consider the following scenario: You are a scientist writing up a section of a paper for presentation at an upcoming conference. You are anticipating some disagreement and potential difficulty communicating because your collaborator is American and you are Chinese. Because of one social distinction, you may focus on other differences between yourself and that person, such as their culture, upbringing and experiences—differences that you would not expect from another Chinese collaborator. How do you prepare for the meeting? In all likelihood, you will work harder on explaining your rationale and anticipating alternatives than you would have otherwise—and you might work harder to reconcile those differences.

This is how diversity works : by promoting hard work and creativity; by encouraging the consideration of alternatives even before any interpersonal interaction takes place. The pain associated with diversity can be thought of as the pain of exercise. You have to push yourself to grow your muscles. The pain, as the old saw goes, produces the gain. In just the same way, we need diversity—in teams, organizations, and society as a whole—if we are to change, grow, and innovate.

This essay was originally published in 2014 by Scientific American. It has been revised and updated to include new research.

About the Author

Katherine W. Phillips

Katherine W. Phillips, Ph.D. , is the Paul Calello Professor of Leadership and Ethics Management at Columbia Business School.

You May Also Enjoy

How to Close the Gap Between Us and Them

Four Ways Teachers Can Reduce Implicit Bias

How to Help Diverse Students Find Common Ground

Three Lessons from Zootopia to Discuss with Kids

Does Neurodiversity Have a Future?

Can Diversity Make You a Better Communicator?

22 Working in Diverse Teams

Learning Objectives

- Describe how diversity can enhance decision-making and problem-solving

- Identify challenges and best practices for working with multicultural teams

- Discuss divergent cultural characteristics and list several examples of such characteristics in the culture(s) you identify with

Decision-making and problem-solving can be much more dynamic and successful when performed in a diverse team environment. The multiple diverse perspectives can enhance both the understanding of the problem and the quality of the solution. Yet, working in diverse teams can be challenging given different identities, cultures, beliefs, and experiences. In this chapter, we will discuss the effects of team diversity on group decision-making and problem-solving, identify best practices and challenges for working in and with multicultural teams, and dig deeper into divergent cultural characteristics that teams may need to navigate.

Does Team Diversity Enhance Decision Making and Problem Solving?

In the Harvard Business Review article “Why Diverse Teams are Smarter,” David Rock and Heidi Grant (2016) support the idea that increasing workplace diversity is a good business decision. A 2015 McKinsey report on 366 public companies found that those in the top quartile for ethnic and racial diversity in management were 35% more likely to have financial returns above their industry mean, and those in the top quartile for gender diversity were 15% more likely to have returns above the industry mean. Similarly, in a global analysis conducted by Credit Suisse, organizations with at least one female board member yielded a higher return on equity and higher net income growth than those that did not have any women on the board.

Additional research on diversity has shown that diverse teams are better at decision-making and problem-solving because they tend to focus more on facts, per the Rock and Grant article. A study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology showed that people from diverse backgrounds “might actually alter the behavior of a group’s social majority in ways that lead to improved and more accurate group thinking.” It turned out that in the study, the diverse panels raised more facts related to the case than homogeneous panels and made fewer factual errors while discussing available evidence. Another study noted in the article showed that diverse teams are “more likely to constantly reexamine facts and remain objective. They may also encourage greater scrutiny of each member’s actions, keeping their joint cognitive resources sharp and vigilant. By breaking up workforce homogeneity, you can allow your employees to become more aware of their own potential biases—entrenched ways of thinking that can otherwise blind them to key information and even lead them to make errors in decision-making processes.” In other words, when people are among homogeneous and like-minded (non-diverse) teammates, the team is susceptible to groupthink and may be reticent to think about opposing viewpoints since all team members are in alignment. In a more diverse team with a variety of backgrounds and experiences, the opposing viewpoints are more likely to come out and the team members feel obligated to research and address the questions that have been raised. Again, this enables a richer discussion and a more in-depth fact-finding and exploration of opposing ideas and viewpoints in order to solve problems.

Diversity in teams also leads to greater innovation. A Boston Consulting Group article entitled “The Mix that Matters: Innovation through Diversity” explains a study in which they sought to understand the relationship between diversity in managers (all management levels) and innovation (Lorenzo et al., 2017). The key findings of this study show that:

- The positive relationship between management diversity and innovation is statistically significant—and thus companies with higher levels of diversity derive more revenue from new products and services.

- The innovation boost isn’t limited to a single type of diversity. The presence of managers who are either female or are from other countries, industries, or companies can cause an increase in innovation.

- Management diversity seems to have a particularly positive effect on innovation at complex companies—those that have multiple product lines or that operate in multiple industry segments.

- To reach its potential, gender diversity needs to go beyond tokenism. In the study, innovation performance only increased significantly when the workforce included more than 20% women in management positions. Having a high percentage of female employees doesn’t increase innovation if only a small number of women are managers.

- At companies with diverse management teams, openness to contributions from lower-level workers and an environment in which employees feel free to speak their minds are crucial for fostering innovation.

When you consider the impact that diverse teams have on decision-making and problem-solving—through the discussion and incorporation of new perspectives, ideas, and data—it is no wonder that the BCG study shows greater innovation. Team leaders need to reflect upon these findings during the early stages of team selection so that they can reap the benefits of having diverse voices and backgrounds.

Challenges and Best Practices for Working with Multicultural Teams

As globalization has increased over the last decades, workplaces have felt the impact of working within multicultural teams. The earlier section on team diversity outlined some of the highlights and benefits of working on diverse teams, and a multicultural group certainly qualifies as diverse. However, there are some key practices that are recommended to those who are leading multicultural teams so that they can parlay the diversity into an advantage and not be derailed by it.

People may assume that communication is the key factor that can derail multicultural teams, as participants may have different languages and communication styles. In the Harvard Business Review article “Managing Multicultural Teams,” Brett et al. (2006) outline four key cultural differences that can cause destructive conflicts in a team. The first difference is direct versus indirect communication, also known as high-context vs. low-context communication . Some cultures are very direct and explicit in their communication, while others are more indirect and ask questions rather than pointing our problems. This difference can cause conflict because, at the extreme, the direct style may be considered offensive by some, while the indirect style may be perceived as unproductive and passive-aggressive in team interactions.

The second difference that multicultural teams may face is trouble with accents and fluency. When team members don’t speak the same language, there may be one language that dominates the group interaction—and those who don’t speak it may feel left out. The speakers of the primary language may feel that those members don’t contribute as much or are less competent. The next challenge is when there are differing attitudes toward hierarchy. Some cultures are very respectful of the hierarchy and will treat team members based on that hierarchy. Other cultures are more egalitarian and don’t observe hierarchical differences to the same degree. This may lead to clashes if some people feel that they are being disrespected and not treated according to their status. The final difference that may challenge multicultural teams is conflicting decision-making norms. Different cultures make decisions differently, and some will apply a great deal of analysis and preparation beforehand. Those cultures that make decisions more quickly (and need just enough information to make a decision) may be frustrated with the slow response and relatively longer thought process.

These cultural differences are good examples of how everyday team activities (decision-making, communication, interaction among team members) may become points of contention for a multicultural team if there isn’t adequate understanding of everyone’s culture. The authors propose that there are several potential interventions to try if these conflicts arise. One simple intervention is adaptation , which is working with or around differences. This is best used when team members are willing to acknowledge the cultural differences and learn how to work with them. The next intervention technique is structural intervention , or reorganizing to reduce friction on the team. This technique is best used if there are unproductive subgroups or cliques within the team that need to be moved around. Managerial intervention is the technique of making decisions by management and without team involvement. This technique is one that should be used sparingly, as it essentially shows that the team needs guidance and can’t move forward without management getting involved. Finally, exit is an intervention of last resort, and is the voluntary or involuntary removal of a team member. If the differences and challenges have proven to be so great that an individual on the team can no longer work with the team productively, then it may be necessary to remove the team member in question.

Developing Cultural Intelligence

There are some people who seem to be innately aware of and able to work with cultural differences on teams and in their organizations. These individuals might be said to have cultural intelligence . Cultural intelligence is a competency and a skill that enables individuals to function effectively in cross-cultural environments. It develops as people become more aware of the influence of culture and more capable of adapting their behavior to the norms of other cultures. In the IESE Insight article entitled “Cultural Competence: Why It Matters and How You Can Acquire It,” Lee and Liao (2015) assert that “multicultural leaders may relate better to team members from different cultures and resolve conflicts more easily. Their multiple talents can also be put to good use in international negotiations.” Multicultural leaders don’t have a lot of “baggage” from any one culture, and so are sometimes perceived as being culturally neutral. They are very good at handling diversity, which gives them a great advantage in their relationships with teammates.

In order to help people become better team members in a world that is increasingly multicultural, there are a few best practices that the authors recommend for honing cross-cultural skills. The first is to “broaden your mind”—expand your own cultural channels (travel, movies, books) and surround yourself with people from other cultures. This helps to raise your own awareness of the cultural differences and norms that you may encounter. Another best practice is to “develop your cross-cultural skills through practice” and experiential learning. You may have the opportunity to work or travel abroad—but if you don’t, then getting to know some of your company’s cross-cultural colleagues or foreign visitors will help you to practice your skills. Serving on a cross-cultural project team and taking the time to get to know and bond with your global colleagues is an excellent way to develop skills.

Once you have a sense of the different cultures and have started to work on developing your cross-cultural skills, another good practice is to “boost your cultural metacognition” and monitor your own behavior in multicultural situations. When you are in a situation in which you are interacting with multicultural individuals, you should test yourself and be aware of how you act and feel. Observe both your positive and negative interactions with people, and learn from them. Developing “ cognitive complexity ” is the final best practice for boosting multicultural skills. This is the most advanced, and it requires being able to view situations from more than one cultural framework. In order to see things from another perspective, you need to have a strong sense of emotional intelligence, empathy, and sympathy, and be willing to engage in honest communications.

In the Harvard Business Review article “Cultural Intelligence,” Earley and Mosakowski (2004) describe three sources of cultural intelligence that teams should consider if they are serious about becoming more adept in their cross-cultural skills and understanding. These sources, very simply, are head, body, and heart . One first learns about the beliefs, customs, and taboos of foreign cultures via the head . Training programs are based on providing this type of overview information—which is helpful, but obviously isn’t experiential. This is the cognitive component of cultural intelligence. The second source, the body , involves more commitment and experimentation with the new culture. It is this physical component (demeanor, eye contact, posture, accent) that shows a deeper level of understanding of the new culture and its physical manifestations. The final source, the heart , deals with a person’s own confidence in their ability to adapt to and deal well with cultures outside of their own. Heart really speaks to one’s own level of emotional commitment and motivation to understand the new culture.

The authors have created a quick assessment to diagnose cultural intelligence, based on these cognitive, physical, and emotional/motivational measures (i.e., head, body, heart). Please refer to the table below for a short diagnostic that allows you to assess your cultural intelligence.

Cultural intelligence is an extension of emotional intelligence. An individual must have a level of awareness and understanding of the new culture so that he or she can adapt to the style, pace, language, nonverbal communication, etc. and work together successfully with the new culture. A multicultural team can only find success if its members take the time to understand each other and ensure that everyone feels included. Multiculturalism and cultural intelligence are traits that are taking on increasing importance in the business world today. By following best practices and avoiding the challenges and pitfalls that can derail a multicultural team, a team can find great success and personal fulfillment well beyond the boundaries of the project or work engagement.

Digging in Deeper: Divergent Cultural Dimensions

Let’s dig in deeper by examining several points of divergence across cultures and consider how these dimensions might play out in organizations and in groups or teams.

Low-Power versus High-Power Distance

How comfortable are you with critiquing your boss’s decisions? If you are from a low-power distance culture, your answer might be “no problem.” In low-power distance cultures , according to Dutch researcher Geert Hofstede, people relate to one another more as equals and less as a reflection of dominant or subordinate roles, regardless of their actual formal roles as employee and manager, for example.

In a high-power distance culture , you would probably be much less likely to challenge the decision, to provide an alternative, or to give input. If you are working with people from a high-power distance culture, you may need to take extra care to elicit feedback and involve them in the discussion because their cultural framework may preclude their participation. They may have learned that less powerful people must accept decisions without comment, even if they have a concern or know there is a significant problem. Unless you are sensitive to cultural orientation and power distance, you may lose valuable information.

Individualistic versus Collectivist Cultures

People in individualistic cultures value individual freedom and personal independence, and cultures always have stories to reflect their values. You may recall the story of Superman, or John McLean in the Diehard series, and note how one person overcomes all obstacles. Through personal ingenuity, in spite of challenges, one person rises successfully to conquer or vanquish those obstacles. Sometimes there is an assist, as in basketball or football, where another person lends a hand, but still the story repeats itself again and again, reflecting the cultural viewpoint.

When Hofstede explored the concepts of individualism and collectivism across diverse cultures (Hofstede, 1982, 2001, 2005), he found that in individualistic cultures like the United States, people perceived their world primarily from their own viewpoint. They perceived themselves as empowered individuals, capable of making their own decisions, and able to make an impact on their own lives.

Cultural viewpoint is not an either/or dichotomy, but rather a continuum or range. You may belong to some communities that express individualistic cultural values, while others place the focus on a collective viewpoint. Collectivist cultures (Hofstede, 1982), including many in Asia and South America, focus on the needs of the nation, community, family, or group of workers. Ownership and private property is one way to examine this difference. In some cultures, property is almost exclusively private, while others tend toward community ownership. The collectively owned resource returns benefits to the community. Water, for example, has long been viewed as a community resource, much like air, but that has been changing as business and organizations have purchased water rights and gained control over resources. Public lands, such as parks, are often considered public, and individual exploitation of them is restricted. Copper, a metal with a variety of industrial applications, is collectively owned in Chile, with profits deposited in the general government fund. While public and private initiatives exist, the cultural viewpoint is our topic. How does someone raised in a culture that emphasizes the community interact with someone raised in a primarily individualistic culture? How could tensions be expressed and how might interactions be influenced by this point of divergence?

Masculine versus Feminine Orientation

There was a time when many cultures and religions valued a female figurehead, and with the rise of Western cultures we have observed a shift toward a masculine ideal. Each carries with it a set of cultural expectations and norms for gender behavior and gender roles across life, including business.

Hofstede describes the masculine-feminine dichotomy not in terms of whether men or women hold the power in a given culture, but rather the extent to which that culture values certain traits that may be considered masculine or feminine . Thus, “the assertive pole has been called ‘masculine’ and the modest, caring pole ‘feminine.’ The women in feminine countries have the same modest, caring values as the men; in the masculine countries they are somewhat assertive and competitive, but not as much as the men, so that these countries show a gap between men’s values and women’s values” (Hofstede, 2009).

We can observe this difference in where people gather, how they interact, and how they dress. We can see it during business negotiations, where it may make an important difference in the success of the organizations involved. Cultural expectations precede the interaction, so someone who doesn’t match those expectations may experience tension. Business in the United States has a masculine orientation—assertiveness and competition are highly valued. In other cultures, such as Sweden, business values are more attuned to modesty (lack of self-promotion) and taking care of society’s weaker members. This range of difference is one aspect of intercultural communication that requires significant attention when the business communicator enters a new environment.

Uncertainty-Accepting Cultures versus Uncertainty-Rejecting Cultures

When we meet each other for the first time, we often use what we have previously learned to understand our current context. We also do this to reduce our uncertainty. Some cultures, such as the United States and Britain, are highly tolerant of uncertainty , while others go to great lengths to reduce the element of surprise. Cultures in the Arab world, for example, are high in uncertainty avoidance ; they tend to be resistant to change and reluctant to take risks. Whereas a U.S. business negotiator might enthusiastically agree to try a new procedure, the Egyptian counterpart would likely refuse to get involved until all the details are worked out.

Short-Term versus Long-Term Orientation

Do you want your reward right now or can you dedicate yourself to a long-term goal? You may work in a culture whose people value immediate results and grow impatient when those results do not materialize. Geert Hofstede discusses this relationship of time orientation to a culture as a “time horizon,” and it underscores the perspective of the individual within a cultural context. Many countries in Asia, influenced by the teachings of Confucius, value a long-term orientation, whereas other countries, including the United States, have a more short-term approach to life and results. Native American cultures are known for holding a long-term orientation, as illustrated by the proverb attributed to the Iroquois that decisions require contemplation of their impact seven generations removed.

If you work within a culture that has a short-term orientation , you may need to place greater emphasis on reciprocation of greetings, gifts, and rewards. For example, if you send a thank-you note the morning after being treated to a business dinner, your host will appreciate your promptness. While there may be a respect for tradition, there is also an emphasis on personal representation and honor, a reflection of identity and integrity. Personal stability and consistency are also valued in a short-term oriented culture, contributing to an overall sense of predictability and familiarity.

Long-term orientation is often marked by persistence, thrift and frugality, and an order to relationships based on age and status. A sense of shame for the family and community is also observed across generations. What an individual does reflects on the family and is carried by immediate and extended family members.

Time Orientation

Edward T. Hall and Mildred Reed Hall (1987) state that monochronic time-oriented cultures consider one thing at a time, whereas polychronic time-oriented cultures schedule many things at one time, and time is considered in a more fluid sense. In monochromatic time , time is thought of as very linear, interruptions are to be avoided, and everything has its own specific time. Even the multitasker from a monochromatic culture will, for example, recognize the value of work first before play or personal time. The United States, Germany, and Switzerland are often noted as countries that value a monochromatic time orientation.

Polychromatic time looks a little more complicated, with business and family mixing with dinner and dancing. Greece, Italy, Chile, and Saudi Arabia are countries where one can observe this perception of time; business meetings may be scheduled at a fixed time, but when they actually begin may be another story. Also note that the dinner invitation for 8 p.m. may in reality be more like 9 p.m. If you were to show up on time, you might be the first person to arrive and find that the hosts are not quite ready to receive you.

When in doubt, always ask before the event; many people from polychromatic cultures will be used to foreigner’s tendency to be punctual, even compulsive, about respecting established times for events. The skilled business communicator is aware of this difference and takes steps to anticipate it. The value of time in different cultures is expressed in many ways, and your understanding can help you communicate more effectively.

Review & Reflection Questions

- Why are diverse teams better at decision-making and problem-solving?

- What are some of the challenges that multicultural teams face?

- How might you further cultivate your own cultural intelligence?

- What are some potential points of divergence between cultures?

- Brett, J., Behfar, K., Kern, M. (2006, November). Managing multicultural teams. Harvard Business Review . https://hbr.org/2006/11/managing-multicultural-teams

- Dodd, C. (1998). Dynamics of intercultural communication (5th ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Earley, P.C., & Mosakowski, E. (2004, October). Cultural intelligence. Harvard Business Review . https://hbr.org/2004/10/cultural-intelligence

- Hall, M. R., & Hall, E. T. (1987). Hidden differences: Doing business with the Japanese . New York, NY: Doubleday.

- Hofstede, G. (1982). Culture’s consequences (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede, G. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Lee, Y-T., & Liao, Y. (2015). Cultural competence: Why it matters and how you can acquire it. IESE Insight . https://www.ieseinsight.com/doc.aspx?id=1733&ar=20

- Lorenzo, R., Yoigt, N., Schetelig, K., Zawadzki, A., Welpe, I., & Brosi, P. (2017). The mix that matters: Innovation through diversity. Boston Consulting Group. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2017/people-organization-leadership-talent-innovation-through-diversity-mix-that-matters.aspx

- Rock, D., & Grant, H. (2016, November 4). Why diverse teams are smarter . Harvard Business Review . https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter

Author & Attribution

This remix comes from Dr. Jasmine Linabary at Emporia State University. This chapter is also available in her book: Small Group Communication: Forming and Sustaining Teams.

The sections “How Does Team Diversity Enhance Decision Making and Problem Solving?” and “Challenges and Best Practices for Working with Multicultural Teams” are adapted from Black, J.S., & Bright, D.S. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/ . Access the full chapter for free here . The content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license .

The section “Digging in Deeper: Divergent Cultural Dimensions” is adapted from “ Divergent Cultural Characteristics ” in Business Communication for Success from the University of Minnesota. The book was adapted from a work produced and distributed under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA) by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution. This work is made available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license .

A set of negative group-level processes, including illusions of invulnerability, self-censorship, and pressures to conform, that occur when highly cohesive groups seek concurrence when making a decision.

a culture that emphasize nonverbal communication and indirect communication styles

a culture that emphasizes verbal expression and direct communication styles

a competency and a skill that enables individuals to function effectively in cross-cultural environments

cultures in which people relate to one another more as equals and less as a reflection of dominant or subordinate roles, regardless of their actual formal roles

culture tends to accept power differences, encourage hierarchy, and show respect for rank and authority

cultures that place greater importance on individual freedom and personal independence

cultures that place more value on the needs and goals of the group, family, community or nation

cultures that tend to value assertiveness, and concentrate on material achievements and wealth-building

cultures that tend to value nurturing, care and emotion, and are concerned with the quality of life

cultures with a high tolerance for uncertainty, ambiguity, and risk-taking. The unknown is more openly accepted, and rules and regulations tend to be more lax

cultures with a low tolerance for uncertainty, ambiguity, and risk-taking. The unknown is minimized through strict rules and regulations

focus on the near future, involves delivering short-term success or gratification and places a stronger emphasis on the present than the future

cultures that focus on the future and delaying short-term success or gratification in order to achieve long-term success

an orientation to time is considered highly linear, where interruptions are to be avoided, and everything has its own specific time

an orientation to time where multiple things can be done at once and time is viewed more fluidly

Working in Diverse Teams Copyright © 2021 by Cameron W. Piercy, Ph.D. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University

Organizations Leadership Oct 1, 2010

Better decisions through diversity, heterogeneity can boost group performance..

Katherine W. Phillips

Katie A. Liljenquist

Margaret A. Neale

Expanding diversity in the workplace is often seen as a good way to inject fresh ideas into an otherwise stagnant environment, and incorporating new perspectives can help members tackle problems from a number of different angles. But only a few have looked into exactly why or how this is so.

New research finds that socially different group members do more than simply introduce new viewpoints or approaches. In the study, diverse groups outperformed more homogeneous groups not because of an influx of new ideas, but because diversity triggered more careful information processing that is absent in homogeneous groups.

The mere presence of diversity in a group creates awkwardness, and the need to diffuse this tension leads to better group problem solving, says Katherine Phillips, an associate professor of management and organizations at the Kellogg School of Management. She and her coauthors, Katie A. Liljenquist, an assistant professor at Brigham Young University, and Margaret A. Neale, a professor at Stanford University, demonstrate that while homogenous groups feel more confident in their performance and group interactions, it is the diverse groups that are more successful in completing their tasks.

Diversity in the Workplace Can Produce New Ideas

Though people often feel more comfortable with others like themselves, homogeneity can hamper the exchange of different ideas and stifle the intellectual workout that stems from disagreements. “Generally speaking, people would prefer to spend time with others who agree with them rather than disagree with them,” Phillips explains. But this unbridled affirmation does not always produce the best results. “When you think about diversity, it often comes with more cognitive processing and more exchange of information and more perceptions of conflict,” Phillips says. In diverse settings, people tend to view conversations as a potential source of conflict that can breed negative emotions, and it is these emotions that can blind people to diversity’s upsides: new ideas can emerge, individuals can learn from one another, and they may discover the solution to a problem in the process. “It’s kind of surprising how difficult it is for people to actually see the benefit of the conversations they are having in a diverse setting,” observes Phillips.

“Generally speaking, people would prefer to spend time with others who agree with them rather than disagree with them.”

Phillips says the study is one of the first to look beyond the newcomer’s impact on a group and to focus instead on how the newcomer shifts alliances, thereby enlivening group interaction. “A lot of the research on newcomers has really specifically focused on the effect of newcomers as a source of new information,” Phillips says. “We know though that not all new ideas come from newcomers. Sometimes new ideas are sitting in the group already, just waiting for the right moment to come up.”

In their study, the researchers focus on whether the newcomer to the group agreed or disagreed with established group members, or “oldtimers” as Phillips refers to them. Sometimes a newcomer’s perspective aligned with one held by one or more of the current oldtimers (these agreeing oldtimers were called allies). By identifying allies, Phillips and her colleagues could determine if the benefits of having a newcomer only occurred when they brought in a new idea.

In the experiment, participants from fraternities and sororities were divided into fifty same-gender four-person groups. Each group performed the same task: read a set of interviews conducted by a detective investigating a murder. Participants decided on the most likely suspect individually before entering the groups to discuss his or her decision. In each four-person group, three individuals were always members of the same fraternity or sorority (the oldtimers) and the fourth individual (the newcomer) was either from that same fraternity or sorority (an “in-group”) or from a different one (an “out-group”).

After completing an unrelated task, the oldtimers were brought together and were given twenty minutes to come to a consensus on the most likely murder suspect. Five minutes into the discussion, a newcomer joined the group. Their task remained the same, but now they had to take the newcomer’s views into consideration. After the discussions were finished, each member rated their confidence in the group’s decision on the murder suspect, their feelings on how effective the group discussion went, how each person felt they fit into the group, and who they believed really committed the murder.

The Out-group Advantage

Unsurprisingly, oldtimers felt more comfortable with newcomers who belonged to their sorority or fraternity. But the biggest discovery was the sheer advantage an out-group newcomer gave a group—and this advantage was even more pronounced when the newcomer did not bring in a new idea. Diverse groups with out-group newcomers guessed the correct murder suspect with far greater frequency, while in-group newcomers hindered the groups’ accuracy (Figure 1). And though out-group newcomers increased group accuracy and performance, these groups reported much lower confidence in their decisions.

“When these diverse groups perform well, they don’t recognize their improved performance,” Phillips points out. “When people have visceral feelings and emotions,” she says, “it’s really hard to explain them away as “good” when they are feeling really bad.” Regardless of the outcome, a diverse group’s members will typically feel less confident about their progress largely due to the lack of homogeneity.

Homogeneous groups, on the other hand, were more confident in their decisions, even though they were more often wrong in their conclusions. In non-diverse groups, Phillips says, “often times the disagreements are just squelched so people don’t really talk about the issue. They come out of these groups really confident that everybody agreed when in fact not everybody agreed. There were new ideas and different opinions that never got discussed in the group.”

Phillips believes understanding the relationship between oldtimers who ally themselves with both in-group and out-group newcomers is important, because these relationships allow for disagreements to occur as well as newcomers’ opinions to be heard. “It is important to remember that these group members did not know each other for very long before identifying strongly with the group,” she says.

“When a newcomer comes in, it interrupts the group. It changes the flow of the process and makes people stop and pay attention to the person,” Phillips says. Whether they stop and pay attention to the newcomer is up to the group. But if they do, the pain will probably be worth the gain.

Member of the Department of Management & Organizations faculty until 2011

About the Writer Bunkhuon Chhun is a freelance science and legal writer based in Longmont, Colorado.

Phillips, Katherine W., Katie A. Liljenquist and Margaret A. Neale. 2009. Is the pain worth the gain? The advantages and liabilities of agreeing with socially distinct newcomers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 35: 336-350.

Read the original

We’ll send you one email a week with content you actually want to read, curated by the Insight team.

October 1, 2014

How Diversity Makes Us Smarter

Being around people who are different from us makes us more creative, more diligent and harder-working

By Katherine W. Phillips

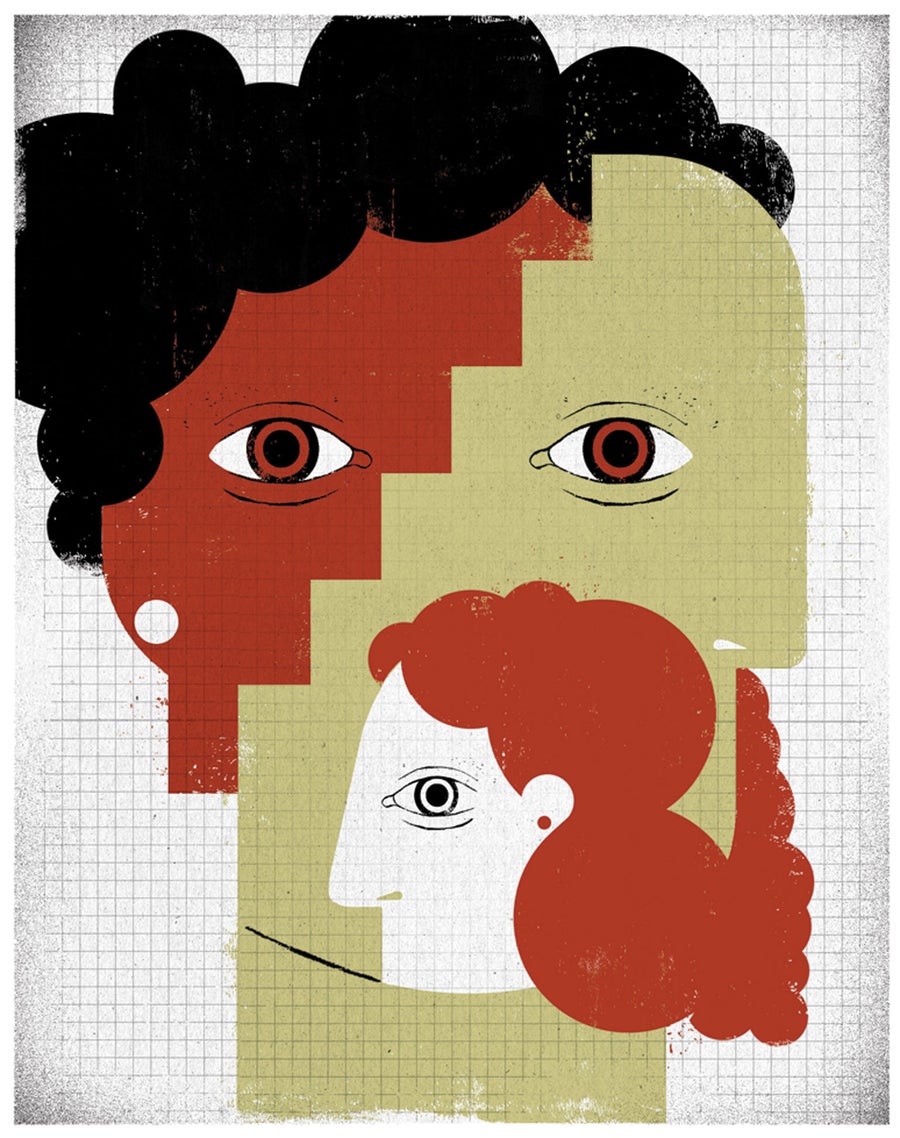

Edel Rodriguez

The first thing to acknowledge about diversity is that it can be difficult. In the U.S., where the dialogue of inclusion is relatively advanced, even the mention of the word “diversity” can lead to anxiety and conflict. Supreme Court justices disagree on the virtues of diversity and the means for achieving it. Corporations spend billions of dollars to attract and manage diversity both internally and externally, yet they still face discrimination lawsuits, and the leadership ranks of the business world remain predominantly white and male.

It is reasonable to ask what good diversity does us. Diversity of expertise confers benefits that are obvious—you would not think of building a new car without engineers, designers and quality-control experts—but what about social diversity? What good comes from diversity of race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation? Research has shown that social diversity in a group can cause discomfort, rougher interactions, a lack of trust, greater perceived interpersonal conflict, lower communication, less cohesion, more concern about disrespect, and other problems. So what is the upside?

The fact is that if you want to build teams or organizations capable of innovating, you need diversity. Diversity enhances creativity. It encourages the search for novel information and perspectives, leading to better decision-making and problem-solving. Diversity can improve the bottom line of companies and lead to unfettered discoveries and breakthrough innovations. Even simply being exposed to diversity can change the way you think. This is not just wishful thinking: it is the conclusion I draw from decades of research from organizational scientists, psychologists, sociologists, economists and demographers.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Information and Innovation

The key to understanding the positive influence of diversity is the concept of informational diversity. When people are brought together to solve problems in groups, they bring different information, opinions and perspectives. This makes obvious sense when we talk about diversity of disciplinary backgrounds—think again of the interdisciplinary team building a car. The same logic applies to social diversity. People who are different from one another in race, gender and other dimensions bring unique information and experiences to bear on the task at hand. A male and a female engineer might have perspectives as different from each other as an engineer and a physicist—and that is a good thing.

Research on large, innovative organizations has shown repeatedly that this is the case. For example, business professors Cristian Dezsö of the University of Maryland and David Gaddis Ross of the University of Florida studied the effect of gender diversity on the top firms in Standard & Poor’s Composite 1500 list, a group designed to reflect the overall U.S. equity market. First, they examined the size and gender composition of firms’ top management teams from 1992 through 2006. Then they looked at the financial performance of the firms. In their words, they found that, on average, “female representation in top management leads to an increase of $42 million in firm value.” They also measured the firms’ “innovation intensity” through the ratio of research and development expenses to assets. They found that companies that prioritized innovation saw greater financial gains when women were part of the top leadership ranks.

Racial diversity can deliver the same kinds of benefits. In a study conducted in 2003, Orlando Richard, now at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and his colleagues surveyed executives at 177 national banks in the U.S., then put together a database comparing financial performance, racial diversity and the emphasis the bank presidents put on innovation. For innovation-focused banks, increases in racial diversity were clearly related to enhanced financial performance.

Evidence for the benefits of diversity can be found well beyond the U.S. In August 2012 a team of researchers at the Credit Suisse Research Institute issued a report in which they examined 2,360 companies globally from 2005 to 2011, looking for a relation between gender diversity on corporate management boards and financial performance. Sure enough, the researchers found that companies with one or more women on the board delivered higher average returns on equity, lower gearing (that is, net debt to equity) and better average growth.

How Diversity Provokes Thought

Large data-set studies have an obvious limitation: they can show only that diversity is correlated with better performance, not that it causes better performance. Research on racial diversity in small groups, however, makes it possible to draw some causal conclusions. Again, the findings are clear: for groups that value innovation and new ideas, diversity helps.

In 2006 Margaret Neale of Stanford University, Gregory Northcraft of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and I set out to examine the impact of racial diversity on small decision-making groups in an experiment where sharing information was a requirement for success. Our subjects were undergraduate students taking business courses at the University of Illinois. We put together three-person groups—some consisting of all white members, others with two white members and one nonwhite member—and had them perform a murder mystery exercise. We made sure that all group members shared a common set of information, but we also gave each member important clues that only he or she knew. To find out who committed the murder, the group members would have to share all the information they collectively possessed during discussion. The groups with racial diversity significantly outperformed the groups with no racial diversity. Being with similar others leads us to think we all hold the same information and share the same perspective. This perspective, which stopped the all-white groups from effectively processing the information, is what hinders creativity and innovation.

Credit: Edel Rodriguez

Other researchers have found similar results. In 2004 Anthony Lising Antonio, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education, collaborated with five colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles, and other institutions to examine the influence of racial and opinion composition in small group discussions. More than 350 students from three universities participated in the study. Group members were asked to discuss a prevailing social issue (either child labor practices or the death penalty) for 15 minutes. The researchers wrote dissenting opinions and had both Black and white members deliver them to their groups. When a Black person presented a dissenting perspective to a group of white people, the perspective was perceived as more novel and led to broader thinking and consideration of alternatives than when a white person introduced that same dissenting perspective . The lesson: when we hear dissent from someone who is different from us, it provokes more thought than when it comes from someone who looks like us.

This effect is not limited to race. For example, in 2013 professors of management Denise Lewin Loyd of the University of Illinois, Cynthia Wang of Northwestern University, Robert B. Lount, Jr., of the Ohio State University and I asked 186 people whether they identified as a Democrat or a Republican, then had them read a murder mystery and decide who they thought committed the crime. Next, we asked the subjects to prepare for a meeting with another group member by writing an essay communicating their perspective. More important, in all cases, we told the participants that their partner disagreed with their opinion but that they would need to come to an agreement with the other person. Everyone was told to prepare to convince their meeting partner to come around to their side; half of the subjects, however, were told to prepare to make their case to a member of the opposing political party, and half were told to make their case to a member of their own party.

The result: Democrats who were told that a fellow Democrat disagreed with them prepared less well for the discussion than Democrats who were told that a Republican disagreed with them. Republicans showed the same pattern. When disagreement comes from a socially different person, we are prompted to work harder. Diversity jolts us into cognitive action in ways that homogeneity simply does not.

For this reason, diversity appears to lead to higher-quality scientific research. In 2014 Richard Freeman, an economics professor at Harvard University and director of the Science and Engineering Workforce Project at the National Bureau of Economic Research, along with Wei Huang, then a Harvard economics Ph.D. candidate, examined the ethnic identity of the authors of 1.5 million scientific papers written between 1985 and 2008 using Thomson Reuters’s Web of Science, a comprehensive database of published research. They found that papers written by diverse groups receive more citations and have higher impact factors than papers written by people from the same ethnic group. Moreover, they found that stronger papers are associated with greater numbers of not only references but also author addresses—geographical diversity is a reflection of more intellectual diversity.

The Power of Anticipation

Diversity is not only about bringing different perspectives to the table. Simply adding social diversity to a group makes people believe that differences of perspective might exist among them, and that belief makes people change their behavior.

Members of a homogeneous group rest somewhat assured that they will agree with one another, understand one another’s perspectives and beliefs, and be able to easily come to a consensus. But when members of a group notice that they are socially different from one another, they change their expectations. They anticipate differences of opinion and perspective. They assume they will need to work harder to come to a consensus. This logic helps to explain both the upside and the downside of social diversity: people work harder in diverse environments both cognitively and socially. They might not like it, but the hard work can lead to better outcomes.

In a 2006 study of jury decision-making, social psychologist Samuel Sommers of Tufts University found that racially diverse groups exchanged a wider range of information during deliberation about a sexual assault case than all-white groups did. In collaboration with judges and jury administrators in a Michigan courtroom, Sommers conducted mock jury trials with a group of real selected jurors. Although the participants knew the mock jury was a court-sponsored experiment, they did not know that the true purpose of the research was to study the impact of racial diversity on jury decision-making.

Sommers composed the six-person juries with either all white jurors or four white and two Black jurors. As you might expect, the diverse juries were better at considering case facts, made fewer errors recalling relevant information and displayed a greater openness to discussing the role of race in the case. These improvements did not necessarily happen because the Black jurors brought new information to the group—they happened because white jurors changed their behavior in the presence of the Black jurors. In the presence of diversity, they were more diligent and open-minded.

Group Exercise

Consider the following scenario: You are writing up a section of a paper for presentation at an upcoming conference. You are anticipating some disagreement and potential difficulty communicating because your collaborator is American and you are Chinese. Because of one social distinction, you may focus on other differences between yourself and that person, such as their culture, upbringing and experiences—differences that you would not expect from another Chinese collaborator. How do you prepare for the meeting? In all likelihood, you will work harder on explaining your rationale and anticipating alternatives than you would have otherwise.

This is how diversity works: by promoting hard work and creativity; by encouraging the consideration of alternatives even before any interpersonal interaction takes place. The pain associated with diversity can be thought of as the pain of exercise. You have to push yourself to grow your muscles. The pain, as the old saw goes, produces the gain. In just the same way, we need diversity—in teams, organizations and society as a whole—if we are to change, grow and innovate.

Why Diversity and Inclusion Are Important for Problem-Solving

Simone Bradley 22 March 2022

Change Management Activate Behavior Change

What happens when we bring in new perspectives? This article explores this and how to activate inclusive problem-solving.

Diversity in our backgrounds equips us with varying mental toolkits. When people with diverse perspectives work inclusively to solve problems, the results are powerful. Take the example of the million-dollar Netflix algorithm challenge :

In 2006, Netflix's CEO, Reed Hastings, announced an open competition to create an algorithm that would predict customers' movie ratings. The algorithm had to be 10% more efficient than Netflix's algorithm, Cinematch. This task was so difficult that Netflix offered a million dollars to anyone who could achieve this. Of course, this competition attracted thousands of participants from various backgrounds – from math majors at an Ivy League university in the US to Austrian computer programmers and even a British psychologist and his daughter! Dry erase markers scribbled across whiteboards, notebooks piled up, and brains were tested. It became clear to contestants that this was not going to be solved by one brilliant individual who had all the answers. Early on, teams realized that the most significant improvements came when individuals combined their results. The secret sauce for the eventual winners (a blended team called BellKor’s Pragmatic Chaos) was, in the end, the collaboration between people with diverse perspectives. Finally, in 2009, the top two teams combined forces, combined their algorithms, and surpassed the 10% threshold. What happened in this competition is what Scott E. Page refers to as the " diversity bonus ." Diversity improves problem-solving and increases innovation which leads to better performance and results for your organization. Our objective in this article is to explore the power of diversity in problem-solving and to provide three ways to improve problem-solving in your organization by activating diversity-embracing behaviors in your employees.

The Power of Activating Diversity of Thought

People tend to solve problems by first looking at their own experiences, habits, culture, and understanding. The brain does this to determine whether we have faced a similar situation before and if we know how to solve it. Psychologists refer to this as a " mental set. "

Mental sets save us time and energy in the decision-making process but can hamper our problem-solving abilities. Different perspectives lead to different kinds of solutions. For example, an obvious solution to one person may seem abstract or irrelevant to someone else. The more perspectives you have when analyzing a problem, the more likely you will consider a broader range of solutions. How can you show your employees how to embrace different perspectives in your organization? To activate diversity , you need to create an environment that embraces the different ways individuals think, feel, and act. This is achieved by taking small actions over time to make inclusive behaviors a habit. Below we'll discuss three ways to help your team encourage diversity and inclusion when problem-solving.

1. Make All Voices Count

True diversity and inclusion mean that everyone in your team gets the opportunity to be heard. Sometimes though, we aren't conscious of who doesn't have a voice in a meeting or event. So, in many situations, the opinions of the most assertive people often carry the most weight. On the opposite side, women of color and other marginalized groups often don’t feel empowered to speak up. In your organization, do you currently have a balance between who gets to talk in meetings and who doesn't?

In your next conference call or in-person meeting, take a back seat and mostly observe while still making sure that you participate when called upon.

After your call, reflect on what stood out for you. Also, consider what strategies you can create to ensure that the only time people on your team aren't heard is because they are on mute!

2. Welcome All Ideas

Organizations that embrace diversity solve problems by fostering an environment where all ideas are welcome. Embracing everyone's thoughts gives your team members the freedom to get creative without worrying about someone else's opinion. Don't miss out on your next great idea because someone was too embarrassed to share it. The next time you have a brainstorming session, encourage your team to share their thoughts, no matter how out of the box they are. Afterward, reflect on what happened in the session:

- What stood out for you when you encouraged all ideas?

- What can you leverage from what you have learned to enable your teams to share their ideas regularly?

3. Normalize Disagreements

A team can only be truly inclusive and allow a wide diversity of thoughts and ideas if it’s possible for members to disagree with each other in an empathetic and considerate way.

Diverse perspectives continue to flow when we normalize disagreements. If your team doesn't have a good strategy for dealing with conflict, only the most forceful personalities will be the ones who get their way.

Prepare yourself and your team for conflict with the following steps:

- Don't make it personal

- Avoid putting down the other person's ideas and beliefs

- Instead of saying "you", use "I" statements to communicate how you feel, what you think, and what you want or need

- Listen to the other point of view without interrupting

- Avoid absolute statements

Final Thoughts

The Netflix algorithm challenge is a perfect illustration of the importance of diversity in problem-solving. The contestants understood that combining different ideas and perspectives was the only way to progress forward. Likewise, organizations need to take this approach too. In this article, we explored how to activate behavior change in your employees by giving them small actions that they can use to be more inclusive when problem-solving. There are many other steps that organizations can take to embrace diversity.

If you are interested in other ways to activate inclusivity, book a consultation to discuss creating a custom D&I program.

Related Articles

23 February 2024

How do you shape a GenAI mindset?

To realise the value of GenAI it's not enough to create experiences that build adoption. Organizations should also focus on...

19 October 2023

ChatGPT - What you should do next

There's so much buzz about ChatGPT, but how can you assist your organization in adopting it safely and ethically? Chief Strategy...

18 July 2023

Change Made Easy

Why is change so hard? And how can it be made easy? In this thought-provoking blog post, our Chief Strategy Officer, Colin...

Cognician’s founding belief is that people are capable of great things when their behavior is driven by meaningful conversations, great questions, powerful ideas, and deeply felt emotions. Our core capability is enabling large organizations to activate behavior change at scale. We achieve this by creating personalized, data-driven digital experiences that are grounded in action, follow-through, reflection, and social engagement. With our multi-day challenges, you can drive measurable change in 30 days or less.

- ACTIVATION VIDEOS

- Book a Call

12.3 Diversity and Its Impact on Companies

- How does diversity impact companies and the workforce?

Due to trends in globalization and increasing ethnic and gender diversity, it is imperative that employers learn how to manage cultural differences and individual work attitudes. As the labor force becomes more diverse there are both opportunities and challenges to managing employees in a diverse work climate. Opportunities include gaining a competitive edge by embracing change in the marketplace and the labor force. Challenges include effectively managing employees with different attitudes, values, and beliefs, in addition to avoiding liability when leadership handles various work situations improperly.

Reaping the Advantages of Diversity

The business case for diversity introduced by Taylor Cox and Stacy Blake outlines how companies may obtain a competitive advantage by embracing workplace diversity. 96 Six opportunities that companies may receive when pursuing a strategy that values diversity include cost advantages, improved resource acquisition, greater marketing ability, system flexibility, and enhanced creativity and better problem solving (see Exhibit 12.6 ).

Cost Advantages

Traits such as race, gender, age, and religion are protected by federal legislation against various forms of discrimination (covered later in this chapter). Organizations that have policies and procedures in place that encourage tolerance for a work climate of diversity and protect female and minority employees and applicants from discrimination may reduce their likelihood of being sued due to workplace discrimination. Cox and Blake identify this decreased liability as an opportunity for organizations to reduce potential expenses in lawsuit damages compared to other organizations that do not have such policies in place.

Additionally, organizations with a more visible climate of diversity experience lower turnover among women and minorities compared to companies that are perceived to not value diversity. 97 Turnover costs can be substantial for companies over time, and diverse companies may ameliorate turnover by retaining their female and minority employees. Although there is also research showing that organizations that value diversity experience a higher turnover of White employees and male employees compared to companies that are less diverse, 98 some experts believe this is due to a lack of understanding of how to effectively manage diversity. Also, some research shows that White people with a strong ethnic identity are attracted to diverse organizations similarly to non-White people. 99

Resource Acquisition

Human capital is an important resource of organizations, and it is acquired through the knowledge, skills, and abilities of employees. Organizations perceived to value diversity attract more women and minority job applicants to hire as employees. Studies show that women and minorities have greater job-pursuit intentions and higher attraction toward organizations that promote workplace diversity in their recruitment materials compared to organizations that do not. 100 When employers attract minority applicants, their labor pool increases in size compared to organizations that are not attractive to them. As organizations attract more job candidates, the chances of hiring quality employees increases, especially for jobs that demand highly skilled labor. In summary, organizations gain a competitive advantage by enlarging their labor pool by attracting women and minorities.

When organizations employ individuals from different backgrounds, they gain broad perspectives regarding consumer preferences of different cultures. Organizations can gain insightful knowledge and feedback from demographic markets about the products and services they provide. Additionally, organizations that value diversity enhance their reputation with the market they serve, thereby attracting new customers.

System Flexibility

When employees are placed in a culturally diverse work environment, they learn to interact effectively with individuals who possess different attitudes, values, and beliefs. Cox and Blake contend that the ability to effectively interact with individuals who differ from oneself builds cognitive flexibility , the ability to think about things differently and adapt one’s perspective. When employees possess cognitive flexibility, system flexibility develops at the organizational level. Employees learn from each other how to tolerate differences in opinions and ideas, which allows communication to flow more freely and group interaction to be more effective.

Creativity and Problem Solving

Teams from diverse backgrounds produce multiple points of view, which can lead to innovative ideas. Different perspectives lead to a greater number of choices to select from when addressing a problem or issue.