my daily art display

A daily dip into the world of art

Vanitas Still-life with a Portrait of a Young Painter by David Bailly

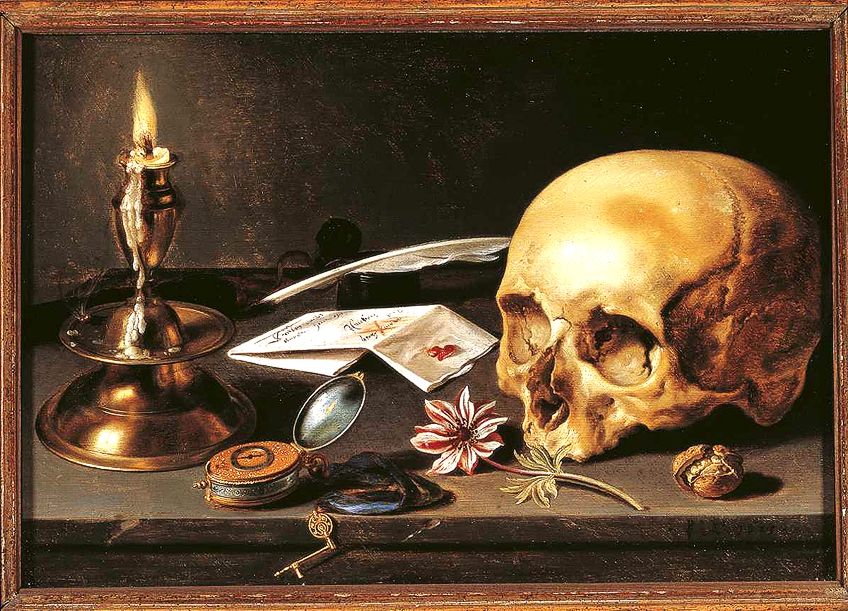

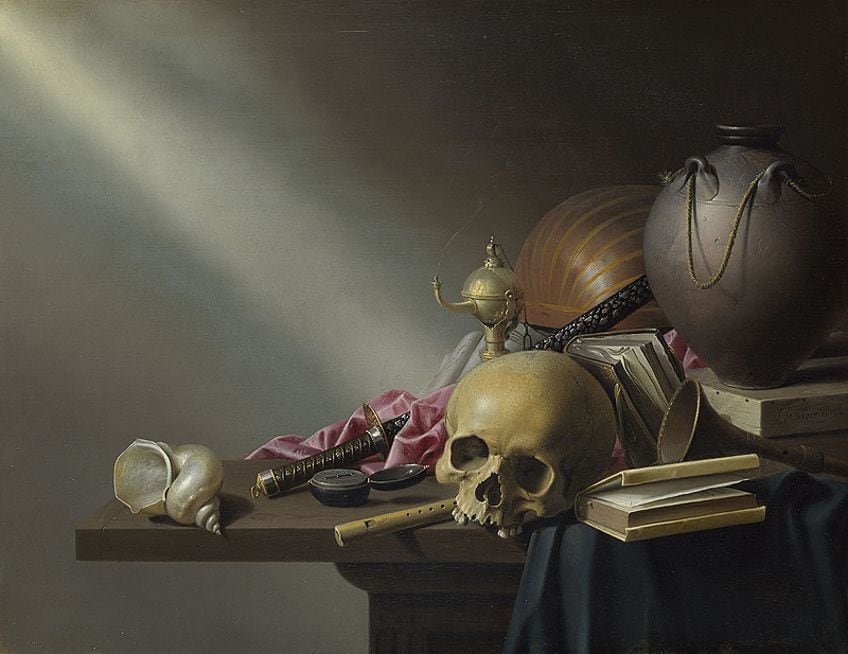

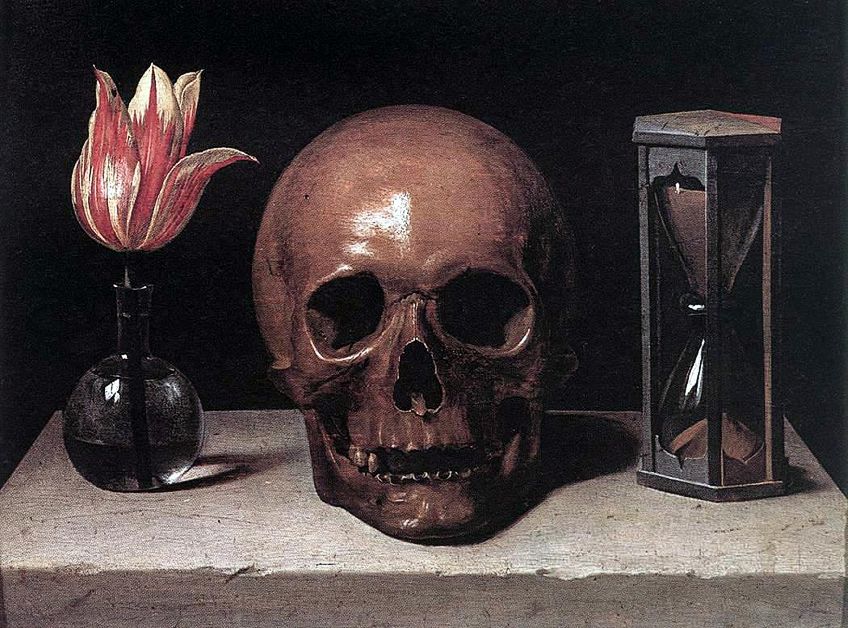

Vanitas is an explicit genre of art in which the artist uses gloomy and moody symbolic objects in order that the viewer becomes very aware of the brevity of life and the inevibility of death. The origins of the term vanitas can be traced back to the Latin biblical adage from the Book of Ecclesiastes (1:2):

“…vanitas vanitatum omnia vanitas…”

which when translated means:

“…vanity of vanities; all is vanity…”

This specific artistic genre was very popular in the 16 th and 17 th century especially in the Netherlands, Flanders and France.

My Daily Art Display blog today looks at one of the works by the great Dutch still life and vanitas painter David Bailly. Bailly was born in Leiden in 1584. His father, Pieter, a Flemish immigrant from Antwerp, was a writing master. Being a practicing Protestant he had fled from the Catholic Spanish rule of his homeland to the safer, more tolerant Northern Netherlands, eventually settling in the town of Leiden. It was whilst living here that he married Willempgen Wolphaertsdr. and the couple went on to have four children, Anthony, Anna, Neeltgen and David. In 1592 David’s father took up the position as writing master at the University of Leiden. He remained there until 1597 at which time he changed careers and became fencing master at a school run by the mathematician Ludolph van Cuelen, which was an establishment set up to train aspiring army officers in the various facets of warfare.

David’s initial training in drawing came from his father and in 1597, at the age of thirteen, he trained at the Leiden studio of the Dutch draughtsman and copper engraver, Jacques de Gheyn II. David Bailly soon came to believe that his future did not lie as a draughtsman but as a painter and he was somewhat fortunate to live in the town of Leiden which was the home of many established and aspiring artists. The leading artist in Leiden at the time was Isaac van Swanenburgh, who with his three sons, had set up a thriving studio in the town. However it was not to this family concern that young David sort employment and tuition but instead his father arranged his son to become an apprentice to the painter and surgeon, Adriaen Verburgh. In 1602 David moved to Amsterdam and became an apprentice in the city studio of the very successful portraitist and art dealer, Cornelius van der Voort.

At the end of 1608, then aged twenty-four, David Bailly, now a journeyman painter, set off on his own Grand Tour, all the time seeking out commissions. He travelled around Europe visiting a number of German cities such as Frankfurt, Nuremburg and Augsburg before crossing the Tyrolean Alps into Italy where he visited Venice and Rome. In all, his journey lasted five years and it was not until 1613 that he returned to the Netherlands.

Once back home his work concentrated on drawing and painting portraits and vanitas still-life works and would often, as is the case in today’s featured work, combine the two genres. His portraiture at the time consisted of many works featuring some of the students and professors of the University of Leiden. He built up a very illustrious clientele which was testament to his artistic ability. Bailly also had a number of pupils, two of whom were his nephews Harmen and Pieter van Steenwyck, who rank amongst the best still-life Dutch Golden Age painters. In 1642 David Bailly married Agneta van Swanenburgh. The couple did not have any children. In 1648, he along with other artists including Gabriel Metsu, Gerard Dou, and Jan Steen founded the Leidse Sint Lucasgilde – Leiden Guild of St Luke. David Bailly died in Leiden in October 1657, aged73.

The painting I am featuring today is entitled Vanitas Still Life with a Portrait of a Young Painter which was completed by David Bailly in 1651 when he was sixty-six years of age and six years before he died. It is now housed in the Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal in Leiden . It is a fascinating painting full of symbolism. To the left of the painting we have, what some believe, is a self-portrait of the artist himself, but of course as we know Bailly’s age when he painted the work we know this was a depiction of himself as a young man in his early twenties. In his right hand he holds a maulstick, or mahlstick, which is a stick with a soft leather or padded head, used by painters to support the hand that holds the brush. In his other hand he holds upright on the table a framed oval portrait of himself as he was at the time of painting this work. So in fact the man sitting on the left of the painting and the man in the frame are one and the same and the inclusion of both images in the painting simply reminds us of the transience of life.

Behind the framed self-portrait we have another oval painting, that of a young woman and this has always interested art historians. It is believed to be a portrait of his wife Agneta in her younger days. However at the time the painting was completed Bailly’s wife was gravely ill, in fact, it could well be that she had already died. Look closely at the wall in the right background, just behind the half empty fluted glass, can you make out a ghost-like portrait of a woman, en grisaille , painted on it, across which drifts the smoke from the extinguished candle? This is another classic vanitas symbolisation. This could well be alluding to the fact that his wife had died from contracting the plague. On the table we also see a standing figure of Saint Stephen bound to a tree, pierced with arrows. So what is the connection with St Stephen and the other objects on the table? One theory is that there was a link between Saint Stephen and the plague, which killed so many people in Europe, including Bailly’s wife. The infections produced by the bubonic plague caused people to compare the “random attacks” of the plague with attacks by arrows and these folk desperately sort out a saint who was martyred by arrows, to intercede on their behalf and so prayers were offered up to St Stephen for him to intercede.

This is a vanitas still-life painting and we see the usual vanitas symbolism amongst the objects depicted in the work of art. Vanitas works allude to the transience of life. Time passes. It cannot be halted. We all must eventually die. Look at the background of the painting. Look at the angle of the wall as it vertically divides the painting. To the left, the painting is brightly lit and we have the young man, the aspiring artist, with his unused artist’s palettes hanging on the wall. To the right of the vertical divide, the room is in shadow and we have the portrait of the old artist. On the vertical line we have a bubble, which is a classic metaphor for the impermanence and fragility of life.

There are many other items to note. On the wall we see a print of Franz Hals 1626 painting, The Lute Player . There is a plethora of objects on the table including a picture of a bearded man which could have been a portrait of Bailly’s father or maybe one of his teachers. On the table, there are also many noteworthy items indicating death such as the skull, the extinguished candle, the tipped-over Roemer glass, the grains of sand of an hour glass running down and the wilting flowers. There are also reminders of the luxuries of life which are of little use to us once we are dead, such as the coins and the pearls as well as items that have once helped us to relax and add to our enjoyment such as the pipe and the book, as well as the art in the form of paintings and sculpture. Sadly, pleasure and wealth are short-lived and ultimately unimportant. This is about the temporality of life. Overhanging the table in the foreground is a scroll with the words:

VANITAS VANIT(AT)VM

ET OMNIA VANITAS

which remind us of the words from the book of Ecclesiastes I quoted at the start of this blog.

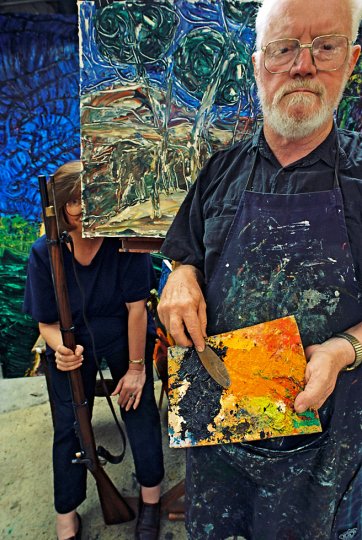

So the next time you decide to have somebody take your photograph, think carefully what you would place by your side or on a nearby table so as to convey a subtle and symbolic message to the people who will view the photograph in years to come.

Share this:

Author: jonathan5485

Just someone who is interested and loves art. I am neither an artist nor art historian but I am fascinated with the interpretaion and symbolism used in paintings and love to read about the life of the artists and their subjects. View all posts by jonathan5485

2 thoughts on “Vanitas Still-life with a Portrait of a Young Painter by David Bailly”

Hello! Thank you for this awesome page, it helped me alot.

- Pingback: David BAILLY, Autoportrait ou Vanité, Nature Morte avec portrait d’un jeune peintre, 1651 | L E S V A N I T E S D 'A M S T E R D A M

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Memento Mori and Vanitas

Summary of Memento Mori and Vanitas

The idea of the "Memento Mori" - a Latin phrase meaning "remember that you must die" - is a fertile theme in art than can be traced back to the Ancient Egyptians. But as a defined genre its beginning is connected specifically with the period of Roman Antiquity (hence the Latin title). Although the purpose of Memento Mori is always to remind the viewer of their own mortality, it is not necessarily presented as an ominous warning. Rather, viewers have been either encouraged to consider each day as a gift to be prized, or, artfully reminded that any chance of a blissful heavenly afterlife is contingent on how one conducts themself while here on earth. The theme of Memento Mori has grown into sub-genres, most notably the "Danse Macabre" and "Vanitas" tendencies. Contemporary artists, who have been much less exposed to death to those of earlier eras, work within the range of time-honored symbolic motifs - skeletons, skulls, flowers, fruit, candles, clocks, hourglasses, and so on - but artists in the modern age tend to treat the Memento Mori theme in a more self-conscious or playful way.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- While the Stoic philosophers promoted the idea that the inevitability of death should act as a reminder to "seize the day", and to live one's life in the present, in early Christianity the Memento Mori acted rather as a reminder that with death comes the possibility of one's soul ascending to heaven. The role of Memento Mori was thus to bring ideas about heaven, hell, and salvation of the soul to the forefront of the worshippers' consciousness. This was achieved through a combination of scripture, and funerary art, such as mosaics and sculpture, which worshippers encountered on display in churches, graveyards, and ossuaries.

- Vanitas images are associated initially with the Dutch Golden Age and its great tradition of still life painting. They are closely related to Memento Mori in that their aim was to remind viewers of their own mortality. But Vanitas went further by condemning the "empty and vain" pursuit of material wealth during one's life on earth. Vanitas images - featuring iconography that symbolized the transience of time/life such as wilting flowers, hourglasses, skulls, candles, watches, and decaying fruit - were thus a means of encouraging viewers to resist the lure of luxurious possessions, to accept their fate, and to devote their day-to-day existence to leading a pure and humble life.

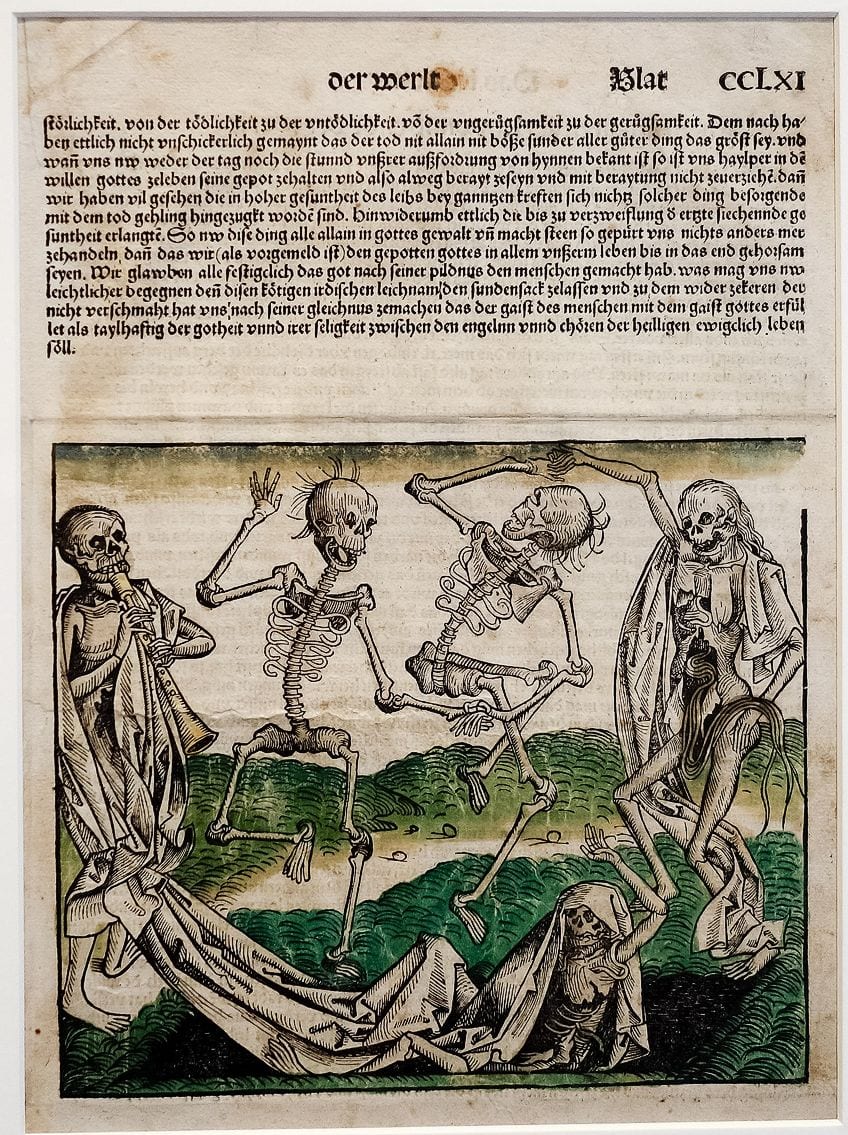

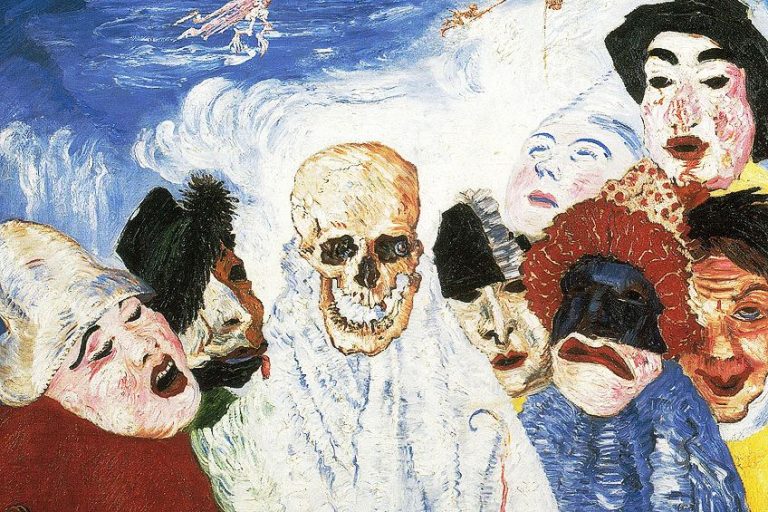

- The ghoulish tradition of the "Danse Macabre" ("dance of death") was a direct response to the devastating effects of the plagues and wars that blighted the Late Middle Ages. The Danse Macabre was represented in the visual art, drama, poetry, and music, and presented death as a dance that joined the living and the dead (typically represented a skeletons). The dances, which cojoined figures from all walks of human life - royals to peasants - were not represented as joyful events (although they were hugely popular with audiences) but rather a reminder to all that death was the "great leveller".

- The 19 th Century saw the birth of photography; a medium well suited to expanding the long tradition of still-life Vanitas compositions. But the birth of the Daguerreotype (and, soon after, less expensive systems) gave rise to a positively macabre photographic genre: the "post-mortem portrait". For many living through the disease-ravaged Victorian era, the new technology presented an opportunity to capture a permanent (and very often - the only) image of a deceased loved one. An uncanny peculiarity of the post-mortem portrait was that an exact likeness of the deceased "sitter" was in fact easier to capture on film than to photograph living relatives who found it hard to sit or stand motionless for the duration of long exposure times.

Overview of Memento Mori and Vanitas

The Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius wrote: "Remember how precious is the privilege of living, breathing, being happy. The perfection of our conduct consists in using each day we live as if it were our last, and in never having impatience, languor, or falseness. We must feed the soul with the wisdom that comes from accepting death".

The Important Artists and Works of Memento Mori and Vanitas

Memento Mori

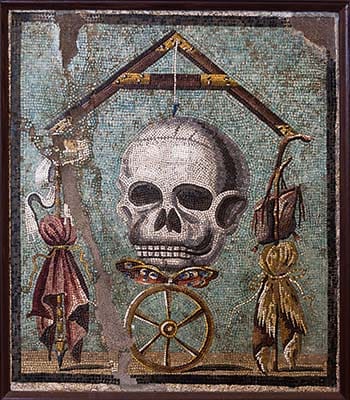

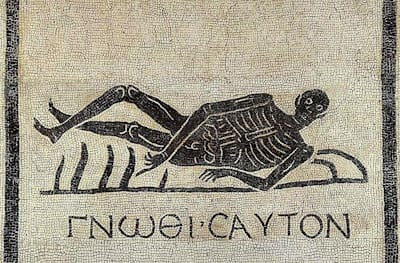

Artist: Unknown artist

This small mosaic, discovered at the ancient Italian resort city of Pompeii (the site of one of the most famous natural disasters recorded in human history when it was engulfed by lava following the eruption of the volcanic mount Vesuvius in 79 AD) dates back to the early medieval age. At the top of the image are balancing and measuring tools (a libella and plumb line) that support the skull (curiously, with ears), that itself sits atop a butterfly, that sits atop a wheel. The butterfly is a symbol of the living soul of the dead, while the "wheel of fortune" ( rota fortunae ), was believed to belong to the goddess Fortuna, who would spin it at random, causing some to prosper; others to suffer. On the left, supporting the libella, is a scepter wrapped in purple fabric representing wealth, while on the right, a wooden stick wrapped in brown fabric, represents poverty. Archaeologist Stefano De Caro writes, the image is "striking for the clarity of its allegorical representation. The topic is Hellenistic in origin and presents death as the great leveller who cancels out all differences of wealth and class [and] was intended to remind diners of the fleeting nature of earthly fortunes". The message "remember you will die" is particularly poignant given that it was discovered (during excavations in 1874) buried under three meters of rubble, debris, and volcanic ash. It is especially interesting to note that the mosaic was sitting atop a dining table in a triclinium (formal dining room), thereby underscoring the belief that, for the ancients, reminders of death were not so much moralizing messages, but more a justification to eat, drink, and make the most of life. As archaeologist Vivian van Heekeren notes, "the Carpe Diem or 'Seize the Day' theme took a central place" in Roman society. Similar Memento Mori mosaics have been found in other triclinium around Pompeii, such as one in the House of the Faun showing skeletons carrying wine jugs, and others showing dancing skeletons with cups at the villas in the nearby town of Boscoreale (which was also buried by the eruption).

Mosaic - Pompeii, Italy (now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli)

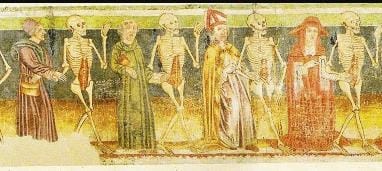

Danse Macabre (Dance of Death)

Artist: Bernt Notke

Danse Macabre ("Dance of Death") images typically feature living people accompanied by allegories or personifications of Death (usually skeletons or decaying corpses) dancing close to a grave. The living typically appear somber, whereas the dead appear more animated, even gleeful or giddy with joy. This example, by late Gothic artist Bernt Notke (who was active in the Baltic region), is the only surviving medieval Dance Macabre in the world painted on canvas, and is, as art historian Krista Andreson notes "undoubtedly the most famous medieval work of art in Estonia". It is believed to be based on another Danse Macabre that Notke painted for St. Mary's Church in Lübeck, Northern Germany, which was finished in 1463, and has unfortunately since been lost. Only a fragment (twenty-five feet in length) of the Tallinn version survives, but it is believed to have been 100 feet long with about fifty figures (with equal numbers of dead and living figures). What we see in the surviving fragment are thirteen figures, including the Dead playing bagpipes and carrying coffins, and living figures such as the Pope, the Emperor, the Empress, the Cardinal, and the King. As was typical of Danse Macabre images, the living figures are arranged by social status, with the richest and most powerful at the front of the procession. Despite this implied hierarchy, the overriding message of these images was that all become equal in death, and worldly attributes, like material possessions or noble rank, cease to matter. In many Danse Macabre images, text accompanies the picture narrative, serving as a sort of dialogue between the dead and the living. In this example the text, in Low German (a dialect native to Northern Germany), sits on a scroll below the parade of figures. The verses alternate between the living attempting to complain about or avoid death (in a pleading tone), and the dead figures summoning them and sarcastically telling them of death's inevitability. For instance, the Empress says "I know, Death means me! I was never terrified so greatly! [...] after all, I am young and also an empress. I thought I had a lot of power, I had not thought of him or that anybody could do something against me. Oh, let me live on, this I implore you!", to which Death replies, "Empress, highly presumptuous, methinks you have forgotten me. Fall in! It is now time. You thought I should let you off? No way!". Historian Marie-Madeleine Renauld adds that "Later, the theme was taken out of its religious context, and artists used it to criticize the ideas of their time and to comment on politics. For instance, the Danse Macabre strongly appealed to artists of the Romantic movement".

Oil on canvas - St. Nicholas Church, Tallinn, Estonia

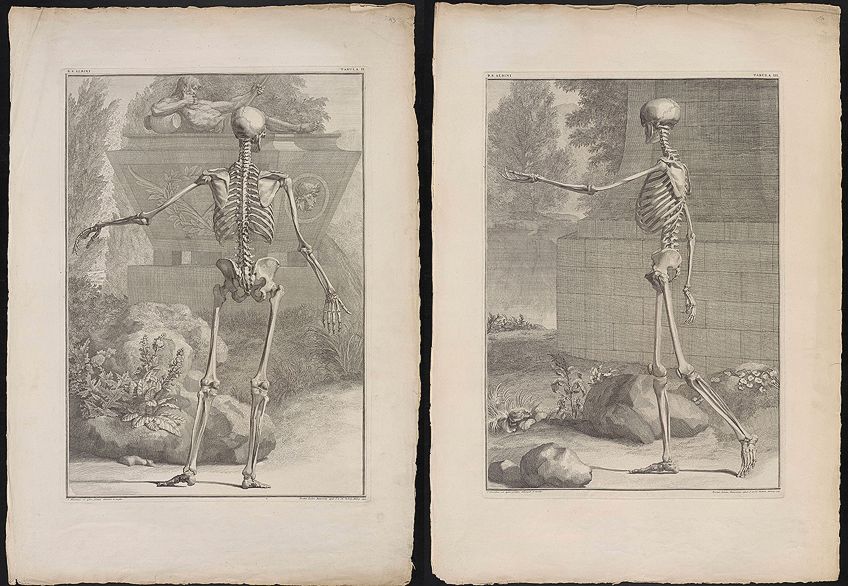

Moving into the 16 th and 17 th centuries, as arts writer Allyssia Alleyne explains, small ivory Memento Mori objects, such as this rosary, became "part of a larger cultural moment that emphasized humility, reflection and moral obligation. Traveling preachers would deliver sermons on mortality to peasants in Paris cemeteries, the working class would buy prints on the theme [...] and the rich had their ivory carvings. [...] It seems inevitable - if ironic - that the ivory devotionals would become the very luxury items they were designed to warn against". Art historian Stephen Perkinson notes, too, that ivory Memento Mori were "sold directly to wealthy collectors, rather than being commissioned by the church [and therefore] should be considered through a secular lens [they were] more about invoking other sorts of moralizing notions of the time that aren't paraliturgical". In this example, each ivory segment features an image of a living person on one side, and a skeletal figure on the reverse. The ivory beads at either end also feature an image of a living human head on one side, and a skull on the other, with a vertical division through the middle. Religious writer Menachem Wecker notes that, because of their small size and fine detail, objects like this "were a beloved part of collectors' kunstkammers, or curiosity cabinets, which were all the rage in Europe at the time", and examples like this one, "which do not bear evidence of use or wear, were more likely intended purely for display purposes rather than being used for prayer". Wecker also observes that many of these works featured tiny pinpricks above and below the eyes, which are "foramina: anatomical features on the skull that allow for vein and nerve passage", exemplifying the way in which medieval medical researchers were "increasingly dissecting and studying corpses". Perkinson states that these ivory objects are among many examples that show that in the Middle Ages, "people were fixated on this idea that your individual identity is conveyed through your face and your appearance - your costume, your heraldry and your insignia of office [so the] message that, in the end, everybody is indistinguishable and the same on some level, social differences are erased, is a pretty powerful one".

Ivory, silver, and partially gilded mounts - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

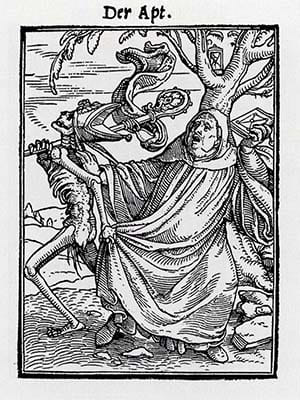

The Abbot (from, The Dance of Death series)

Artist: Hans Holbein the Younger

Germany came relatively late to the Renaissance. Indeed, as Italy was moving into the period of High (or Late) Renaissance, Germany was just beginning to move on from the dominant Gothic style. As Germany's artists began to travel into neighboring European countries, their work evolved accordingly and their interest in the human anatomy and representing the human form more naturalistically followed. Yet even in light of these new influences, Germanic art developed in a way that retained a uniquely national element. Germany became known for its woodcuts and engravings, and with the creation of the printing press, it produced cheap, mass produced, art that could be disseminated amongst the public. Early German printmaking was characterized by themes of superstition and Christian and pagan myth which came with a reminder of the certainty of death and damnation, and chief amongst its practitioners, was Hans Holbein the Younger. Historian Ted Pennant-Rea describes Holbein's The Dance of Death as "a great, grim triumph of Renaissance woodblock printing. In a series of action-packed scenes Death intrudes on the everyday lives of thirty-four people from various levels of society - from pope to physician to ploughman [...] The year before he began The Dance, he had illustrated Martin Luther's influential translation of the New Testament into German. So Holbein was working close to the heart of the accelerating movement for Church reform. It comes as little surprise, then, that Death reserves particularly grim treatment for members of the Catholic clergy. It drags off a fat abbot by his cassock [as seen in this example], leads an abbess away by the habit as though she were an animal, and takes the form of two skeletons and two demons to see to the pope himself". The Dance series was an adaptation of the Danse Macabre and, as such, Death typically appears in the guise of a skeleton. Historian Stephanie Buck argues that "What makes [Holbein's Death vignettes] particularly interesting are the varying reactions of the doomed figures, whom Holbein depicts with vivid gestures and facial expressions". Pennant-Rae adds, "In Holbein's series no one is actually engaged in a dance with Death. This removes an element of comic catharsis found in the mutuality of earlier dances. Holbein's more static figures respond to Death realistically". He concludes that "Reproductions obscure just how tiny the wooden blocks were - no bigger than four postage stamps arranged in a rectangle. The blocks were cut by Hans Lützelburger, a frequent and highly skilled collaborator of Holbein's. Lützelburger had cut forty-one blocks and had ten remaining when Death surprised him too. The blocks were then sold to creditors, and eventually printed and published for the first time in Lyons in 1538 as Les simulachres and historiees faces de la mort. Since the book's great success Holbein's series has been consistently in print, inspiring writers and artists from Rubens in Flanders, to Millet in France, and Dickens in England".

Woodcut - Kunstmuseum Basel

Still Life with Dead Hare and Birds

Artist: Jan Fyt (Jan Fijt)

17 th -century Flemish Baroque painter Jan Fyt (or Jan Fijt) produced several still lives of game depicted as hunting trophies, including this image of a dead hare and birds. The creatures have yet to have their fur and feathers plucked. They lay piled on stones, and thorny vines are visible around them. The animals here serve as a clear reminder of death. As still-life painting was dominant in Northern Europe at the time, the Memento Mori message was often conveyed through depictions of dead animals, wilting flowers, and rotting fruit. Works like this can also be understood as a Vanitas, a genre that carried an added symbolic warning against focusing one's life on the pursuit of luxuries. As curator Axel Vécsey says, "Hunting has long been entertainment for the privileged. No wonder then that the genre of painted hunting trophies flourished most in Flanders in Rubens's time, which more than any other era was in the sway of the cult of heaving plenty and worldly extravagance. Surprisingly, though obviously not coincidentally, in the other half of the Netherlands, newly seceded Protestant Holland, an art of the most puritan approach sprang up simultaneously". Vécsey adds that, after a visit to Holland in 1642, the tone of Fyt's work "changed considerably [...] into the triumphant uproar of brazen Baroque there crept more muted, melancholy chords. The magnificent spread of the kill of game here is more a lament to mortality, than an invitation to a vain banquet. The message is completed with a symbol aptly Dutch in its directness: thorns referring to the passion of Christ". Arts writer Fraser Hibbitt pointed to an innate paradox with Vanitas like these when he wrote, "Vanitas subsisted during the seventeenth century to guide the mind to the contemplation of death and the vanities of living. Yet it was borne from a contradiction that the act of painting itself, creating a beautiful artifact, was vanity itself. Vanitas paintings became objects of earthly value, something it was trying to denounce".

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, Hungary

Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle

Artist: Arnold Böcklin

There has long existed a tradition of artists creating self-portraits with Memento Mori imagery, such as English painter Thomas Smith's, Self Portrait (c. 1680), and Dutch Golden Age painter David Bailly's, Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols (1651). In this 19 th century example, Swiss Symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin looks out past the viewer, appearing to be listening as much as looking, with a paintbrush in his right hand and a paint palette in his left. Death is personified as a grinning skeleton standing over his left shoulder, playing a single-stringed violin. The image, which references the concepts of both Memento Mori and Danse Macabre, is strikingly similar to, and likely influenced by, a 16 th century portrait of British nobleman, Sir Brian Tuke, by an anonymous painter (on display at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich where Böcklin lived at the time), in which a skeleton looms behind the subject holding what appears to be the neck of a stringed instrument in its left hand, while pointing at an hourglass with its right hand. Böcklin was all too familiar with death. He was in Paris during the February Revolution of 1848, and was witness, through his bedroom window, to countless prisoners being transported to execution. His first wife died just a year after their marriage (in 1850), and though he remarried a few years later, seven of the couple's fourteen children died during infancy. In this painting, Böcklin seems to have become blasé towards death, or perhaps he believed that, even after his own passing, he would live on through his art (represented here by the brush and palette). Legend has it (though this was never confirmed) that Böcklin only added the skeleton after his friends saw the self-portrait and, puzzled by his expression, asked what he was listening to. Alma Mahler, wife of the composer Gustav Mahler, explained how her husband was inspired by Böcklin's painting to add a violin solo to his Fourth Symphony (1899-1900). Musicologist Maureen Buja explains that "The second movement is generally described as a Totendanz (Dance of Death). [...] The violin presents the character 'Freund Hein' (Friend Henry) who is a German medieval personification of Death. [...] Originally, Mahler had headed this movement: 'Death strikes up the dance for us; she scrapes her fiddle bizarrely and leads us up to heaven'". Meanwhile, the Memento Mori self-portrait tradition has continued after Böcklin, with works as diverse as Norwegian expressionist artist Edvard Munch's, Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm (1895), and the Young British Artist (YBA) Sarah Lucas's, Self Portrait with Skull (1997).

Oil on canvas - Alte Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Deceased child with flowers

The rise of commercial photography in the mid 19 th century provided new opportunities for creating Memento Mori images. While British pioneers such as Thomas Richard Williams created photographs in the tradition of Vanitas paintings (his Sands of Time (1850-52), for instance, features a human skull, an hour glass, an open book and discarded reading glasses), the birth of the Daguerreotype gave rise to a more macabre photographic genre: the "post-mortem portrait" (or the "Victorian Death Portrait"). As the Victorian poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning said of this new phenomenon, "It is not merely the likeness which is precious, but the association and the sense of nearness involved in the thing ... the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever!". Victorian England was witness to high mortality rates, especially amongst infants. Diseases like measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, rubella, cholera, and typhoid were widespread. The death of a family relative, often a child, was a trigger to having a photographic portrait made in the first place. Post-mortem photography was popular amongst all classes thanks to the affordability (when compared to painted portraits) of the silver-plated Daguerreotype and, in time, less expensive glass- or paper-based alternatives. In 1860, renowned letter-writer Jane Carlyle (wife of Scottish writer and historian Thomas Carlyle) exclaimed "Blessed be the inventor of photography! I set him above even the inventor of chloroform! It has given more positive pleasure to poor suffering humanity than anything else that has cast up in my time or is like to -- this art by which even the poor can possess themselves of tolerable likenesses of their absent dear ones". The historian Genevieve Carlton writes, "Unlike many portraits, which were taken in photo studios, post-mortem photos were usually taken at home. As the trend of death portraits took hold, families put effort into preparing their deceased relatives for the photoshoot. That could mean styling the subject's hair or their clothes. Some relatives opened the dead person's eyes. Photographers and family members sometimes decorated the scene to make the purpose of the photograph clear. In some images, flowers surround the deceased. In others, symbols of death and time - like an hourglass or a clock - mark the portrait as a post-mortem photograph".

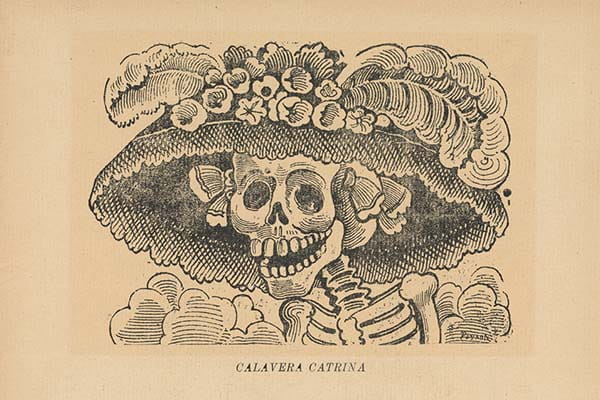

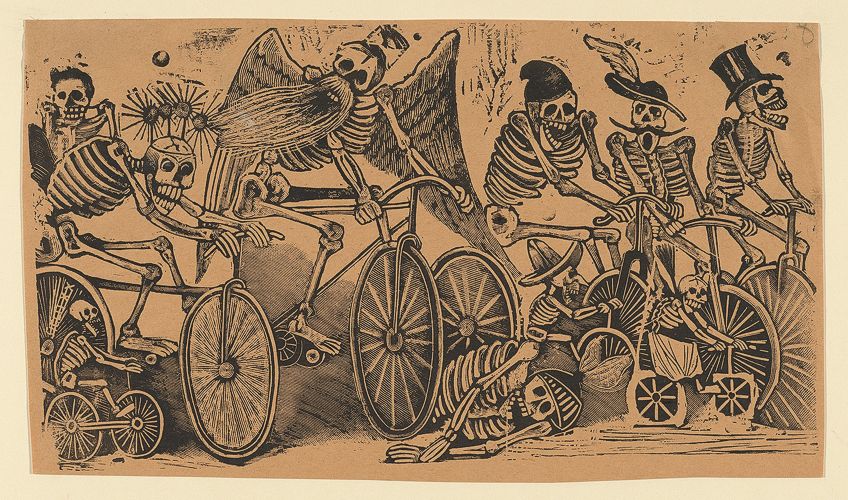

Calavera Catrina (The Garbancera Skull)

Artist: José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar

Mexican illustrator, cartoonist, and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar once declared: "Todos somos calaveras - We are all skeletons". Posada created satirical political images, and illustrations that accompanied "literary calaveras" which, as culture writer Isabel Carrasco explains, are short, "irreverent verses (or poems) that tackle death with irony, satire, and just plain good humor". Drawing on the way in which skeleton figures in Danse Macabre images had typically mocked the living, literary calaveras, as Mexican culture writer Dale Hoty Palfrey adds, were "written to poke fun at living friends, politicians and celebrities, pointing to incidents and personal foibles that single them out for imagined selection by the Grim Reaper". The most iconic of Posada's works is his creation, Calavera Catrina , an upper-class woman who may have lived in the lap of luxury, but, as indicated by her skeletal form, was doomed to die just like every other mortal. Curator Susanna Brooks writes, "Her stylish appearance and amusing, naïve sensibility endeared her to the disgruntled masses. She quickly became a satirical emblem of the sins of vanity and greed and the folly of government corruption. La Calavera Catrina was among the first of many animated skeleton characters Posada created to populate his tongue-in-cheek, pro-revolutionary illustrations. She was also the most popular and enduring. The chic, chapeau-wearing lady skull became a kind of national folk icon". Posada died in poverty in 1913. He was by then largely forgotten and was even buried in an unmarked grave. Given, moreover, that they were only to be found printed in daily newspapers, there are few extant Posada works. But, as historian Philip Kennedy writes, "thankfully, he found veneration through a number of other artists that emerged in Mexico after the revolution. They recognised his contribution to the art of engraving, and saw how he had shaped the visual language of Mexican art and illustration". Calavera Catrina was perhaps most famously reworked by Mexican muralist Diego Rivera in his 1947 mural Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon along Central Alameda) . Kennedy concludes that "In many ways, Posada was a revolutionary. He helped to establish a national art that was independent of European tradition and that was built around a language of indigenous symbols and motifs. Today humorous political cartoons and satirical comic strips are incredibly popular in Mexico and, for many, Posada is often considered to be the founding father of the genre". Indeed, Catrina has become one of the most iconic symbols of "Mexicanidad" (Mexican-ness), and no trip to Mexico is considered complete without the purchase of a decorative Calavera souvenir.

Zinc etching

Marilyn (Vanitas)

Artist: Audrey Flack

Audrey Flack is an American artist who made her name as a Photorealist painter. Before Flack, Photorealist artists addressed what she called the "unemotional and banal" (often featuring cars, motorcycles, aeroplanes, and bland urban scenery). Flack was inspired (amongst other things) by the Dutch and Spanish Vanitas traditions and produced still lifes that addressed the themes of life and death, as well-as ideas about femininity. Archivist Lily Hopkins writes "Flack incorporated both everyday feminine ephemera as well as items of a macabre nature to create vibrant, complex, and emotional still life images that stood in stark contrast to their male-driven counterparts. These works, which garnered a considerable amount of attention and helped to pioneer the Photorealist movement as it is known today, began with detailed photographic still lifes from which the artist drew inspiration". Flack's Vanitas are brought into the 20 th century through the introduction of modern day objects and photographic imagery, producing what she termed "narrative still lives". For Marilyn Flack created what resembles a shop-window shrine to the actress and pop culture icon (Marilyn Monroe) who died in tragic circumstances aged 36 (in 1962). The two Marilyn portraits are black and white and, with the childhood photograph of Flack and her brother that sits between them, contrast sharply with the intense colors that saturate the other objects that complete the shrine. These images are painted with a level of exaggerated realism (or hyperrealism): the various textures of delicate rose petals, shiny fruit and transparent glass meticulously copied here from still-life photographs. Behind the two portraits of Marilyn, we see a page from a biography that tells of her sexual allure and how "through the power of make-up" a woman could "paint oneself into an instrument of one's own will". Given the faded monochrome photographs, the melting candle, the draining hourglass and the over-ripened fruit, Flack's Marilyn possess a symbolic lament to the waning of memory, and given that portraits of Monroe seem to predate her rise to the rank of Hollywood sex symbol, very possibly the loss of innocence.

Oil over acrylic on canvas - University of Arizona Art Museum, Tucson

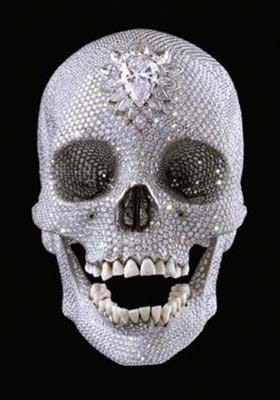

For the Love of God

Artist: Damien Hirst

This sculpture, by British conceptual artist Damien Hirst, is an 18 th -century human skull (purchased from a London taxidermist), still containing the deceased's teeth, and encrusted with 8601 flawless diamonds attached to 32 platinum plates. Hirst took the title from his mother who, when told of what he was planning to do, exclaimed, "For the love of god, what are you going to do next!". The artist himself said of the work, "Every artwork that's ever interested me is about death. I thought, well what's the maximum you could pit against death, and diamonds came to mind". Thought to be the most expensive work of art by a living artist at the time, the materials themselves cost tens of millions of dollars. The sculpture serves thus, not only as a Memento Mori (since the skull patently reminds the viewer of death), but also as an ironic Vanitas, given what it implies about anyone with enough wealth to purchase such an extravagant ornamental item and who will ultimately meet the same end (death) as the most impoverished pauper. Art dealer Celine Fraser called For the Love of God "the ultimate expression of [...] material overindulgence". Hirst was particularly inspired by the Mexican Día de Los Muertos (Day of the Dead) and the British Museum's collection of Aztec skulls. Early in his career, Hirst produced a photograph of himself titled With Dead Head (1991), in which he is pictured, aged sixteen, half-grinning, half-grimacing, and posing next to a severed human head he came across at the county morgue in Leeds. He later explained, "I was doing anatomy drawing. I took some photos when I shouldn't have done. [...] But I just suddenly thought [...] to me, the smile and everything seemed to sum up this problem between life and death. It was such a ridiculous way of [...] being at the point of trying to come to terms with it, especially being sixteen and everything: this is life and this is death. And I'm trying to work it out". Since then, Hirst has dealt with death in other controversial ways, perhaps most famously in his sculptural vitrines, like The Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Somebody Living (1991). In these works, Hirst, a leading member of the YBA (Young British Artists) movement, took dead animals (some of them bisected) and placed them in glass tanks filled with formaldehyde. For the artist, these types of works encourage the modern viewer, who is usually cushioned from the realities of death through the luxuries of modern living, to reflect perhaps on their own mortality. He stated that the use of precious stones in For the Love of God was not to glamorize diamonds, but rather to make a statement about death: "[diamonds] bring out the best and the worst in people ... people kill for diamonds. They kill each other".

Platinum, diamond, human teeth - White Cube Gallery, London, England

Memento Mori in the Age of Antiquity

The custom of acknowledging the certainty of death dates back to the Ancient Egyptian civilization. In his essay, "That to Study Philosophy is to learn to Die" (1580), for instance, the French Renaissance philosopher Michel de Montaigne wrote about the Egyptian ritual at which a death feast was concluded with the raising of a skeleton to the chant of, "Drink and be merry, for such shalt thou be when thou are dead". However, the idea of "Memento Mori" - Latin for "remember you must die" - is generally agreed to have originated with the school of Stoicism, a Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in Ancient Greece and Rome. Stoicism proposed to treat each day as a gift and not to waste time on trifling and vain matters. Epictetus, the Greek Stoic philosopher exiled in Rome, told his students that to fear death was tantamount to cowardice, "discipline yourself against such fear", he warned, "direct all your thinking, exercises, and reading this way - and you will know the only path to human freedom". The Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca also advised, "let us compose our thoughts as if we've reached the end. Let us postpone nothing. Let's settle our accounts with life every day".

Epictetus would illustrate his argument with the telling of a fabled story of Roman military heroism. Following a key military victory, a group of jubilant military generals organized a day-long street parade. The military general, idolized by his own men and the cheering public, led the parade in a chariot drawn by four horses. However, also riding in the chariot, was a slave. His sole responsibility was to remind the general of his mortality by continuously whispering in the general's ear: "Respice post te. Hominem te esse memento. Memento mori!" ("Look behind. Remember thou art mortal. Remember you must die!"). Epictetus impressed on his students that they too should remain humble, conscientious, and mindful of the passing of all earthly things. At the same time philosophers like Epictetus and Seneca were musing upon the nature of death, so too were visual artists. The preferred Memento Mori symbols of the ancient artists - such as skulls and skeletons, coffins, and hourglasses - would be passed down through the ages.

Memento Mori and Christianity

While the philosophy of Stoicism saw the inevitability of death as a reminder to seek growth and fulfillment in everyday life, in early Christianity Memento Mori took on a more cautionary tone. The fall of the Roman empire in the fifth century gave rise to a confused and disorderly period from which the Catholic Church emerged as the most powerful institutional body. Emperors and leaders soon learned that the best way to exert and retain power was through forming close allegiances with the Church (hence the widespread building of grand cathedrals and churches). Places of worship housed funerary art that compelled the faithful to reflect on God's gift of life (however fleeting that may be). In the Bible, Psalm 90, Moses prays to God (on behalf of himself and his followers) "to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom"; Isaiah 40:7 states that "The grass withers, the flower fades when the breath of the LORD blows on it; surely the people are grass"; and Ecclesiasticus 7:40 reads "in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin". Believers were, then, left in no doubt that when they die they will face judgement at the gates of Heaven, and if they wished for a divine afterlife, they must take heed of these words and the associated artworks.

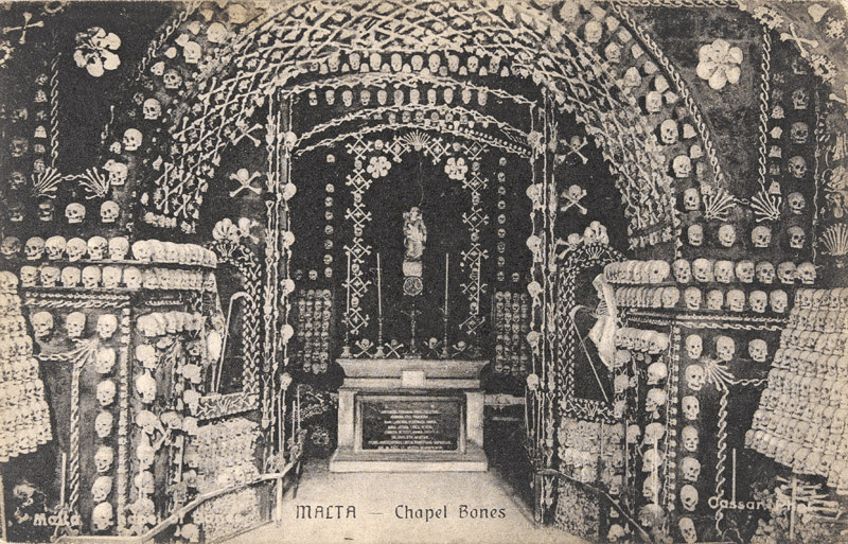

Author René Ostberg writes that "Memento mori was also used in Christianity as an artistic expression that was intended to inspire piety. In architecture, ossuaries, or 'bone churches,' lined with human bones functioned both as memento mori and places for storage if a cemetery became too crowded". Some notable ossuaries include the 15 th -century Sedlec Ossuary in the Czech Republic, and the 16 th -century Capela dos Ossos in Portugal, whose entrance features the warning "We bones, lying here bare, await yours". In the late Middle Ages (around the 1300s) cadaver tombs, or transi , began to be created, which featured a sculpted representation of the deceased person's body, usually in the process of decomposing, atop the tomb. Theologian Christina Welch writes that the cadavers tombs "were a form of memento mori sculpture reminding all who looked on them that death was inevitable and thus the afterlife should be at the centre of one's earthly thoughts and deeds".

Danse Macabre

The "Danse Macabre" ("dance of death") is a ghoulish tradition that emerged in Europe during the Late Middle Ages as a response to numerous diseases, disasters, and wars. The great famine (1314-22), the Black Death (that killed over 25 million Europeans between 1346-51), and the Hundreds' Years war (1337-1453) all contributed to a life expectancy at around 35-40 years of age. The Danse Macabre, which was represented in the visual art, drama, poetry, and music, typically denoted death as a circular dance joining the living and the dead. It did not discriminate between rich and poor; male and female, young and old, with death being understood by allcomers as the "great leveller". Danse Macabre carried a satirical element, too, in the way it mocked the perils of human vice. Indeed, the dances were not represented as a joyous occasion at all, but rather as a penance. In the past, dancing had been dismissed by Christians as an amoral pagan ritual, but this prejudice was now starting to dissolve with dancing allowed in churches or cemeteries during Christian festivals and ceremonies.

Historian Marie-Madeleine Renauld writes "According to the journal of a Parisian bourgeois, a Danse Macabre was painted in 1424 in the Holy Innocents' Cemetery in Paris, making it the first known pictorial representation of the subject in Europe. The Holy Innocents' Cemetery was an important place located at the center of medieval Parisian life. Over the years, over 10 million bodies were buried or piled up in mass graves. In medieval tradition, it was not a quiet place but was actually quite lively. People could cut across and meet in cemeteries, buy food or goods from salesmen, or enjoy actors' performances there. Although a sacred place, the cemetery acted as a center for everyday life. Jehan of Orléans, the painter of Charles VI, King of France, and his brother Louis I, Duke of Orléans, supposedly painted the scene on an arcade wall bordering one of the cemetery's mass graves. Jehan portrayed delegates of the royal and religious powers, majestically dancing among skeletons and corpses". The Holy Innocents Cemetery was destroyed in 1669, but other Danse Macabre images from this period include Giacomo Borlone's The Triumph of Death (1485) at the Disciplini Oratory in Clusone, Lombardy, Italy, and Michael Wolgemut's The Dance of Death (1493) in his illustrated encyclopedia The Nuremberg Chronicle . Many later artists also produced Danse Macabre imagery, including Hans Holbein the Younger for his Dance of Death woodcut illustration series (1523-25), and Jakob von Wyl's, Dance of Death (1610-15), at the Ritterscher Palace, Lucerne, Switzerland.

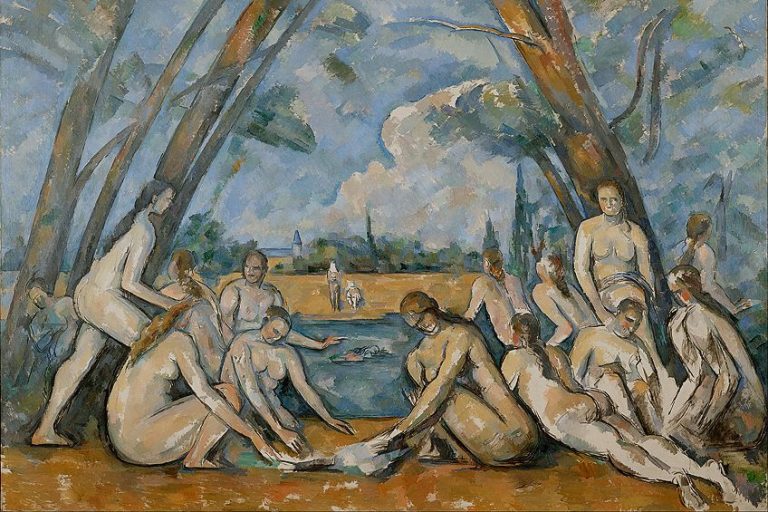

Vanitas in the Netherlands

The Protestant Reformation in the 16 th century effectively divided Christian Europe between Catholicism and Protestantism. The latter fostered a more individualistic approach to devotion (when compared with the grand ceremonial leanings of Catholicism). "Vanitas" emerged as a distinct protestant genre in the Netherlands at the same time the country was breaking away from Catholic Spanish rule. The idea that images could serve as aids to spiritual contemplation was at the root of Vanitas (Latin for emptiness or vanity), a sub-genre of the still life. Vanitas (the title is drawn from a passage in The Bible (Ecclesiastes 1:2; 12:8): "Vanity of vanities, all is vanity") were thus closely associated with the emergence of the Dutch Republic, and initially, with the municipality of Leiden (40 kms north of Amsterdam). As arts writer Fraser Hibbitt notes, "There are several motifs integral to Vanitas. The Dutch Master paintings emphasized different motifs depending on their geographical location as certain regions preferred different motifs [...] the city of Leiden preferred images of books, being a university town". Artists such as Harmen Steenwijck, David Bailly, and Pieter Claesz are today considered the genre's chief practitioners.

Vanitas images are closely related to Memento Mori in that their aim was to remind viewers of their own mortality. But Vanitas went further by condemning the "empty and vain" accumulation of material wealth during one's life on earth. Vanitas images were conceived of as a means of encouraging viewers to turn away from the pursuit of luxurious possessions and focus their energies on accepting a humble, more pious, daily existence. Vanitas were highly detailed still lifes and associated with representing the reality of earthly things (rather than the dramatic Biblical vignettes preferred by Catholic worshippers). Hibbitt goes on, "Vanitas paintings differ from standard still-life paintings by the fact that they are symbolic. It is not to showcase objects, or as an aesthetic display of an artist's skill - though both traits show themselves in a Vanitas painting [...] Vanitas is a variety of the still-life form [...] The most common motifs are representations of wealth: gold, purses, and jewellery; representations of knowledge: books, spyglass, maps, and pens; representations of pleasure: food, wine cups, and fabrics. Lastly, representations of decay; skulls, flowers, candles, and hourglasses [...] It is not that it consists of these objects that makes it important but that the attention and focus of the painting are these objects alone".

Vanitas in Spain

The Spanish Vanitas was heavily influenced by the thematic and stylistic traits of the Dutch example (finely detailed still lifes that carried the message that all earthly riches are meaningless in the face of death). But they were produced at a time when the Spanish Golden Age was nearing its end, and the paintings reflected this decline too. The Spanish Golden Age was a period of prosperity and renewal in art and literature that lasted roughly between the late 15 th and the end of the Franco-Spanish War (1635-59) with the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees (between Spain and France). It also coincided with the demise of the devoutly Catholic Habsburg dynasty that had dominated Europe politically and militarily. The most notable difference between the Dutch and Spanish Vanitas is that, while both focused on still lifes, the latter would accommodate a living presence, such as devout religious figures (including angels, knights, and bishops) or even animate skeletons.

Historian Anisia Iacob writes "A very well-known work of this genre of vanitas still-life is that of Antonio de Pereda, entitled Allegory of Transience , which depicts precisely the fall of the Spanish Habsburgs. In the painting, an angel holds in their hand a cameo portrait of Emperor Charles V, gesturing with the other hand to the globe nearby to express the once-great expansion of the Habsburg Empire, which, almost a century after the emperor's death, is divided and on the brink of ruin. Skulls surround the lavish armor and sophisticated weapons on the table to indicate that military endeavors are pointless. Even if one builds an empire of the great extent and influence as that of the Spanish emperors, it will be ruined one day and disappear eventually, as all earthly things do. As it can be seen, this still life is deeply rooted in the Spanish political situation of the time, expressing both a particular lesson and a more universal one. If an empire can't last, the lives and projects of individuals are even less likely to last".

Memento Mori - Charms and Trinkets

By the turn of the 15 th -16 th century, Memento Mori, rendered through ivory carvings and handheld pieces (what curator Stephen Perkinson calls, "miniature masterpieces"), were the height of fashion. Journalist Allyssia Alleyne (in conversation with Perkinson) writes that at a time of "relative social and political stability, ivory memento mori were part of a larger cultural moment that emphasized humility, reflection and moral obligation. Traveling preachers would deliver sermons on mortality to peasants in Paris cemeteries, the working class would buy prints on the theme [...] and the rich had their ivory carvings". Perkinson adds that they were "a response to the fact that people might (have been getting) distracted from their faith, from their moral duties. They might be distracted into obsessing over luxury goods and treasures instead of remembering the fragility of life".

Although the use of mourning rings dates back to the 14 th century, the wearing of rings and lockets in memory of a passed loved one became popular during the 17 th century. London's vintage jewellery traders, Berganza , writes, "Generally the name and dates of the loved one would be engraved on a ground of black enamel with some embellishments. These rings or brooches would have been expensive and the money was traditionally left in a will for the express purpose of having a piece of jewellery made. There was a massive surge in the amount of mourning rings being made in the 1660's as a direct result of the Black Death. The motifs remain constant throughout the centuries although the styles change. They would include, primarily, a skull and cross-bones, a skeleton, sometimes an hour-glass to remind people of the short span of life or even a spade in some cases, this was usually coupled with the legend 'Memento Mori'". Later still, during the 19 th century Regency and Victorian eras, Britain was witness to some of the highest infant mortality rates in history. This desperate situation gave rise to a macabre new fashion for so-called "post-mortem portraits" (the practice of photographing recently deceased loved ones as a way of memorializing them) and the mass production of Memento Mori rings but cast in cheaper materials such as enamel and hard, black vulcanized rubber. The rings would often feature a photograph of the deceased, and sometimes contain a lock of hair. Like post-mortem portraiture, the rings were soon seen as tasteless and had fallen out of fashion by the end of the century.

Concepts and Styles

Skulls and skeletons.

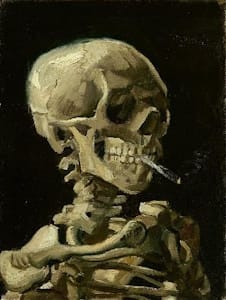

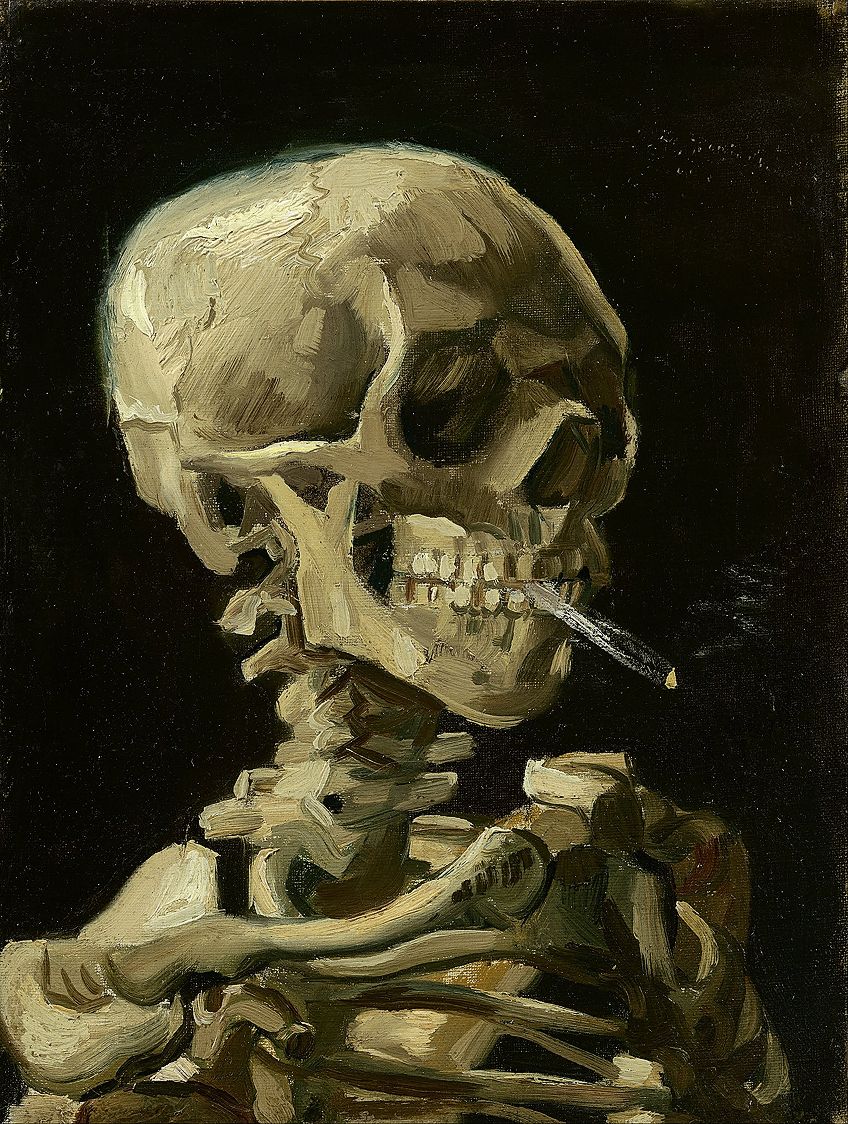

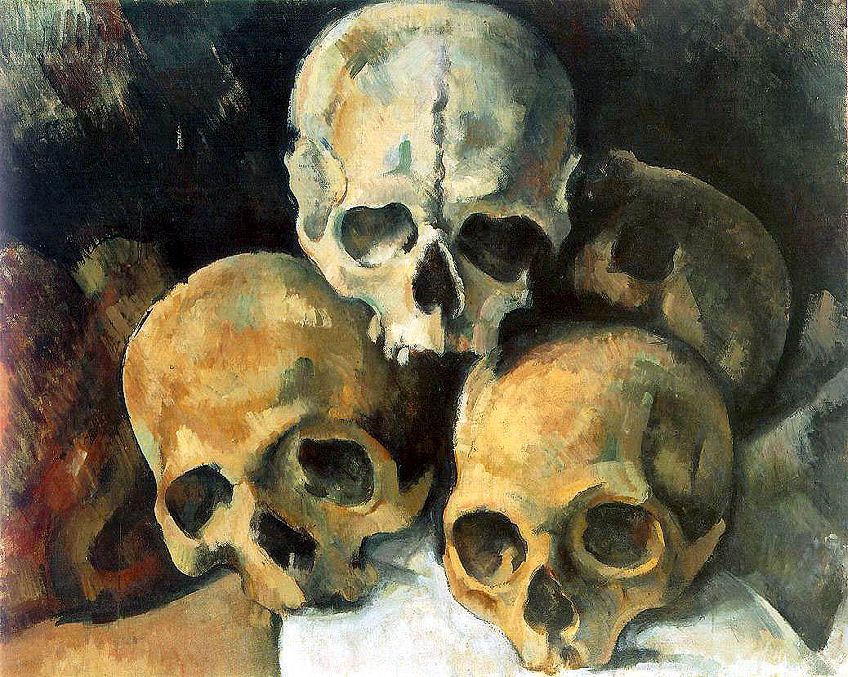

Memento Mori employed many metaphors to evoke the inevitability of death. The human skull and/or skeleton are physical fragments of a life once lived and rank therefore as the most ubiquitous and long-standing symbols of mortality. Examples are legion throughout the history of art: from the tabletop mosaics discovered at the ancient ruins of Pompeii, throughout the Vanitas traditions of the Netherlands and Spain, to the work of the Romantic painters and poets such as William Blake ( Skeleton of Urizen (1794) for example). However, by the late 19 th century, skulls and skeleton bones have been treated with a more individual, less portentous, tone by some of the greatest modern and postmodern artists. Well known examples include: Vincent van Gogh ( Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette (c. 1885-86)), Paul Cézanne ( Pyramid of Skulls (1901)), Salvador Dalí ( Women Forming a Skull (1951)), Jean-Michel Basquiat ( Untitled (Scull/Skull) (1981)), and Gerhard Richter ( Schädel (Skull) (1988)).

Others, such as, Georgia O'Keeffe , have turned their artistic attentions from human to animal skulls. With works such as, Cow's Skull: Red, White, and Blue (1931), O'Keeffe drew upon the hundreds of cattle skulls she happened upon in the New Mexico desert to effectively reverse the symbolism associated historically with the human skull. She called her cow skulls "as beautiful as anything I know" and presented them as symbols, not of death, but rather as emblems of longevity and American strength and resilience during the years when the great depression and drought were threatening the very future of the nation. Perhaps the contemporary artist who became most consistently engaged with the image of the human skull (since 2001) was South African artist, Steven Gregory. His decorative art skulls (which often feature precast eyes) such as, Beyond Suspicion (2007), are at once humorous and profound. Gregory said of his skulls that they force the viewer to confront the idea that "art only exists because death exists" while adding that he had "always felt bones were less morbid and more beautiful".

The theme of death is also addressed in more circuitous ways (than skeletons and skulls). Timepieces are a long-standing motif in Memento Mori art with hourglasses, pocket watches and clocks representing the passage of time. During the 16 th century, watches in particular were all but unattainable for the peasant classes. Watches, much like crowns and coins, becoming a symbol of wealth in Vanitas and were thus presented as reminders that there was no value attached to such items in the afterlife. So-called "Form Watches" also rose in popularity during the 16 th century. Form Watches were in fact handheld clocks shaped in the likeness of other things, including skulls and animals. Even Mary, Queen of Scots, gifted a Form Watch in the shape of a skull to her companion from chilhood (and future nun) Mary Seton. The watch also carried engravings of figures representing death and Adam and Eve, and served as reminder/warning to her friend of the inevitable "the fall of man".

The symbol of the watch/clock has passed down through the ages and featured in the work of Francis Bacon , a figurative artist who complained that people seemed to drop dead "around me like flies", and for whom mortality and death became a recurring theme. His, Study for Self-Portrait (1971), was painted shortly after the suicide of his lover and partner, George Dyer. Bacon painted himself with a typically tortured expression, his twisted head resting on his hand, giving pictorial and symbolic prominence to his wristwatch. Commenting on Félix González-Torres's , Untitled (Perfect Lovers) , meanwhile, historian Rhonda Riche writes, "This powerful piece, produced between 1987-1990 and 1991, consists of a pair of Seth Thomas clocks set to the same time and eventually fall out of sync. [...] González-Torres was a Cuban-born American process artist [Process art is when the creative process itself is the most significant element of the finished piece] who died at a tragically young age due to complications from AIDS. [...] While Untitled (Perfect Lovers) deals with the subject of death, it could also be read as a tribute to love. After his partner, Ross Laycock, died in 1991, González-Torres revisited this work to help cope with the loss. More than a meditation on mortality, the clocks became a reflection on their relationship and the time they spent together. Recently critics have suggested that the work representing the continuation of life with the possibility of regeneration - life goes on as gallerists must conserve the piece (and replace the batteries)".

Butterflies

The butterfly, an insect whose lifespan typically last just a few weeks between spring and early summer, has come to symbolize the fragility of life and the eternal nature of a soul which lives on after death. They appear in the earliest Memento Mori mosaics and are a feature in Dutch Vanitas. Maria van Oosterwyck, for instance, was well known for her fondness for butterflies, and in particular, her love of Red Admirals (Vanessa atalanta), which are seen in her meticulously detailed still lifes. Perhaps her best known work, Vanitas - Still Life (1668), features several symbolic objects common to Dutch Vanitas, not least a skull, an hourglass, and wilting flora. But through the placing of the astrological globe and the butterfly, van Oosterwyck draws her viewers' attention to the theme of the transcendence from earth to heaven. Indeed, her Red Admiral is symbolic of that journey, with the metamorphosis of the caterpillar into a cocoon, before emerging as a butterfly, embodying the story of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus himself.

The symbolic potency of the butterfly is not restricted to Western art. During the 1980s and 1990s, the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama depicted butterflies in an array of colour and in simple monochromatic black and white. Her art, that embodies her strong spiritual beliefs while simultaneously honouring ancient Japanese tradition and culture, treats the butterfly as the carrier of mortal souls (as they depart the living realm). Each of Kusama's butterflies has of its own shape, colours, and patterns thereby representing the individuality of every human being. The art critic Matthew Wilson argues, meanwhile, that "Maybe the most famous contemporary practitioner to use butterflies in their art is Damien Hirst . Also aware of the traditional symbolism of butterflies, Hirst has been using them since the beginning of his career in the early 90s but his culminating works deployed butterflies on an epic scale. I am Become Death, Shatterer of Worlds (2006) is a kaleidoscopic composition which used 2,700 real sets of butterfly wings. They strobe across a 5m-long canvas creating a cinematic and sublime spectacle. Death is disconcertingly electrified into a thing of great beauty".

Later Developments

Hibbitt notes that "Vanitas painting lost its commercial popularity by the end of the Dutch Golden Age [c.1672]. The meaning behind Vanitas lost its potency with the spirit of the combative reformation losing its momentum. Vanitas subsisted during the seventeenth century to guide the mind to the contemplation of death and the vanities of living. Yet it was borne from a contradiction that the act of painting itself, creating a beautiful artifact, was vanity itself. Vanitas paintings became objects of earthly value, something it was trying to denounce". In the modern era, artists were apt to approach the theme of Memento Mori from a more personal and/or more analytical, angle. For example, Vincent van Gogh's , Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette (1885), represented a break with his vividly colored Post-Impressionist paintings in favor of a satirical irony, grey and beige "smoking skeleton" that amounted to a critique of Belgium's Royal Academy of Fine Art where he became "bored to death" in classes devoted to documenting the human anatomy.

In his crayon and ink still life lithograph, Black Jug and Skull (1946), meanwhile, Pablo Picasso depicted a jug, a skull, and an open book on a table. As the Tate Museum describes, "the book traditionally alludes to excessive pride through learning and the wine jug to the transitoriness of worldly pleasures. The skull is a memento mori, a reminder of the inevitable approach of death. Picasso was superstitious about death, kept a skull in his studio and had included human or animal skulls in his work as early as 1908 [ Composition with Skull ]". Given its date, Picasso's Cubist Vanitas would also appear to reflect the enormity of the death and suffering during the Second World War. Moving into the second half of the 20 th century, Pop artist Andy Warhol's images of skulls (such as Skulls (1976)) sought to address (without moral judgement) the caprices of consumer and celebrity culture. Arts writer Sukayna Powell, comments, "For a man obsessed with replication, identity and eternal life through material beauty, the memento mori [was] both a challenge and a motivating force" for the artist.

Mexican Art

The concept of Memento Mori finds unique expression in Mexican art, literature, and cultural practices, particularly in relation to the national, Día de los Muertos (or Day of the Dead ). On this day, (actually two days, November 1-2, when the souls of children are believed to return on the 1st, and adults on the 2nd), Mexicans visit the graves of deceased relatives, and/or gather in their homes or public spaces where they erect temporary altars ( ofrendas ) to their ancestors. The altars feature photographs of the deceased, as well as skull sculptures ( calaveras ) and orange marigold flowers ( cempazúchitl ). Relatives place the favorite foods and drinks of the deceased on their graves/altars in the belief that the souls of the dead come back to commune with the living. Author Don Winslow remarks, "The Mexicans, they don't mind talking about death. [...] They don't try to keep it at arm's length. They're tight with death, intimate with it. They keep their dead close to them".

The custom of Día de los Muertos carried over into Mexican art, most notably in the Calavera Catrina figure who was first drawn around 1910-12 by Mexican illustrator and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada. Curator Susanna Brooks writes, "A wide-eyed lady skeleton donning a large, lace brimmed hat festooned with flowers and feathers flashes a broad toothy grin. The smiling dandified dame is [...] a corpse with a lively aristocratic air and fashionable dress to match. Oblivious to the current state of her demise, she clutches nonchalantly to her long lost human existence". Catrina crossed over into iconic Mexican works, such as muralist Diego Rivera's , Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon along Central Alameda) (1947), while skeletal imagery featured in works by Frida Kahlo , including Girl With a Death Mask (1938), and The Dream, The Bed (1940). As well as being a motif in Mexican art, it features widely in the works of American Chicano artists, such as Carlos Almaraz, Chaz Bojórquez, Yreina Cervántez, and Magú, who took inspiration from the Mexican Muralists , pre-Columbian art, and everyday Memento Mori symbols such as calendars.

Photography

Two hugely influential texts on the relationship between photography and death emerged in the 1970s. In 1973 the American essayist and critic, Susan Sontag, published, On Photography . In it she wrote, "All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person's (or thing's) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time's relentless melt". It was a sentiment her partner of 15 years, American photographer Annie Leibovitz , took to heat when she controversially published a photograph of Sontag's corpse soon after her passing (in 2004). In 1980, France's most famous philosopher and literary critic, Roland Barthes, took up the same theme in his book, Camera Lucida (1980). Barthes also read the photograph as a relic of the dead, in his case an early photograph of his beloved mother. Through her picture Barthes introduced the idea of the "punctum", an element that was wholly unique to photography: "The punctum of a photograph is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)", he wrote. Andy Grundberg of The New York Times wrote '''Camera Lucida' is, in a sad and almost tragic way, a record of [Barthes's] attempts to come to terms with grief. His fascination with the portrait of his mother [as a child], leading to the discovery that the ultimate punctum is death, is the fascination of a man who is seeking, like Proust, to recover a life that has vanished".

In photographic practice, meanwhile, the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum held an exhibition titled The Illumination of Life by Death: Memento Mori & Photography in 2022. The exhibition aimed to explore "how people have lived robustly while facing death through approximately 150 photographic works, stimulating the imagination to live positively through difficult times". The exhibition featured works of photographers as wide ranging as Robert Capa , Walker Evans , Lee Friedlander , Robert Frank , William Eggleston , Diane Arbus , Araki , and Eugène Atget . Contemporary photographers, such as the Britain's Nick Knight, have continued to mine the Memento Mori tradition through images of dripping roses (such as Rose IV (2012)). As he explained, "roses are this sort of most poetic moment of life and death. The rose blooms and blossoms and it's most incredible, but you know it's incredible because it's going to die, and that makes the rose more poignant than any other flower in a way, because you have this incredible beauty, [but] it's announcing its own death". Another British photographer, Peter Mitchell, expanded upon the Memento Mori theme through manmade structures. In his 2016 series, Memento Mori , he photographed derelict, or "condemned" (soon-to-be-demolished) buildings in the Quarry Hill area of his hometown of Leeds in Northern England. He intended for the series to serve as a reminder "to the power of photography, to those who engineered and built the Flats, to the people who lived and died in the Flats and to the city of Leeds itself".

Contemporary Art and Design

The theme of the Memento Mori has shown remarkable longevity. One of the most direct heirs to the vanitas genre is the American photorealist artist, Audrey Flack , who produced her titled Vanitas series during the mid-to-late 1970s. As Curatorial Consultant, Robert R. Shane, explained, "Flack's recurring themes - life and death, luxury and consumption [are symbolized] using traditional iconography from 17 th -century Dutch vanitas still life as a starting point. [Her vanitas often feature] fruit and flowers, which, while luxurious, show signs of decay and the vanity of life. In addition to incorporating personal objects and cosmetics, Flack gave this genre a 20 th -century update by mirroring the spectacle of contemporary consumer culture through glittering light that sparkles among mirrored and glass objects". Flack's contemporary, the Conceptual artist Jenny Holzer , argued that it was "unsurprising that art which can be seen as the descendant of the memento mori genre, remains one of the ways to explore and express feelings of doubt and alienation surrounding human mortality". In her own series, Living (1980-82), for instance, Holzer posted bronze plaques in public spaces featuring text such as: " You realise you're shedding parts of the body and leaving mementos everywhere ".

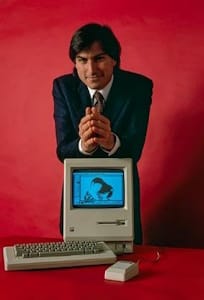

Bringing the theme of Memento Mori into the 21st century was Steve Jobs, designer, inventor, and pioneer of the personal computer revolution, and co-founder (with Steve Wozniak) of the global Apple empire. Jobs recognized that by accepting his own mortality he was liberated to take creative risks and to think innovatively. Indeed, one of Jobs's most famous quotes demonstrates that the topic of Memento Mori is as pertinent today as it was during the days of the ancient Stoics. It went as follows: "Remembering that I'll be dead soon is the most important tool I've ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life. Almost everything - all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure - these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important. Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart". Jobs died in 2011, aged 56 (from complications brought on by pancreatic cancer), having first transformed the way the world experiences music, movies, and digital communications.

Useful Resources on Memento Mori and Vanitas

- Hans Holbein der Jungere (Masters of German art) By Stephanie Buck

- Memento Mori in Contemporary Art Our Pick By Taylor Worley

- Death in Documentaries: The Memento Mori Experience By Benjamin Bennett-Carpenter

- Art of Death: Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual c.1500 - c.1800 Our Pick By Nigel Llewellyn

- Women and the Material Culture of Death By Beth Fowkes Tobin

- Vanitas: Meditations on Life and Death in Contemporary Art By John B. Ravenal

- Photographing Death: Representations of Death in Memorial and Art Photography in Victorian Britain By Jannie Uhre Kongsgaard

- The Vision of Death: Wax Sculpture in the Seventeenth Century By Davide Stefanacci

- The Dance of Death Our Pick By Hans Holbein and Ulinka Rublack

- John Lydgate, the Dance of Death, and Its Model, the French Danse Macabre By Clifford Davidson and Sophie Oosterwijk

- The Dance of Death: A Graphic Commentary on the Danse Macabre Through the Centuries By Fritz Eichenberg

- Art and Death By Chris Townsend

- Butterflies: The ultimate icon of our fragility By Matthew Wilson / BBC Culture / September 16, 2021

- Watching The Watches: Taking A Look at Timepieces In Contemporary Art By Rhonda Riche / Watchonista

- Art Only Exists Because Death Exists. Skulls in Art By Candy Bedworth / Daily Art / November 2, 2022

- José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar: Skulls, Skeletons and Macabre Mischief By Philip Kennedy / Illustration Chronicles

- Victorian Death Photos - And the Disturbing History Behind Them By Genevieve Carlton / ATI / July 20, 2021

- La Calavera Catrina: Mexico's Eternal Feminine Muse By Susanna Brooks / Whatcom Museum

- Fruit Soup By Lilly Hopkins / University Art Museum, University at Albany / January 25 - April 2, 2022

- Vanitas By Adam Augustyn / Britannica.com

- Death in the Photograph By Andy Grundberg / The New York Times / August 23, 1981

- Pablo Picasso, Black Jug and Skull 1946 Tate Museum

- Danse Macabre: The Allegorical Representation of Death By Marie-Madeleine Renauld / TheCollector.com / November 20, 2021

- Antique Engagement Rings & Vintage Jewellery Berganza Vintage Jewellers, Hatton Garden, London

- How a macabre reminder of death became a Renaissance status symbol By Allyssia Alleyne / CNN / October 31, 2017

- Hans Holbein's Dance of Death (1523-5) By Ted Pennant-Rea / The Public Domain Review / April 17, 2018

- Macabre Themes in German Renaissance Printwork Talking Objects / April 24, 2007

- History of Memento Mori The Daily Stoic

- The Art of Dying - Memento Mori Paintings Through Art History By Balasz Takac / Widewalls / January 10, 2022

- Memento Mori: Life and Death in Western Art from Skulls to Still Life By Jessica Stewart / My Modern Met / June 23, 2019

- Vanitas Painting or Memento Mori: What are the Differences? Our Pick By Anisia Iacob / The Collector / November 17, 2022

- 7 Ways of Looking at the Memento Mori, Art History's Spookiest - and Most Misunderstood - Genre Our Pick By Menachem Wecker / Artnet News / September 14, 2017

- Vanitas: Dutch Master Paintings Explained Our Pick By Fraser Hibbitt / The Collector / July 14, 2020

- The Fascinating Traits of Spanish Vanitas Paintings Our Pick By Anisia Iacob / The Collector / January 3, 2023

- Vanitas: Paintings by the Dutch Old Masters Inspired by Life and Death By Madeleine Muzdakis / My Modern Met / February 12, 2022

- A Method and an Object: An Art Historical Approach Applied to the 'Memento-Mori' Mosaic from Pompeii, Italy By Vivian van Heekeren / International Journal of Student Research in Archaeology / March 2016

- Danse Macabre: The Allegorical Representation of Death By Marie-Madeleine Renauld / The Collector / November 20, 2021

- The Skull, the Butterfly and God: Damien Hirst on Death & Religion By Lucie Howie / MyArtBroker

- Arnold Böcklin, Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle Smart History

- Art 101: What is a Memento Mori? P.S. You are going to die CBC Arts

- Decorating with Death: The Morbid World of VANITAS Paintings Our Pick Empire of the Mind

- How Vanitas Is Secretly Uplifting Our Pick Zox

- Memento Mori and The Macabre Allure of Michaelina Wautier Sotheby's

- Hidden Symbols of Still Live Paintings: Vanitas! Our Pick Informe

- Memento Mori: The Personification of Death - Dean Cantù Our Pick TEDx Talks

- Memento Mori: The Importance of Remembering Mortality Reading the Past

- Memento Mori Imagery and the Limits of the Self in Late Medieval Europe Our Pick The Courtauld

- Death in Arnold Bocklin's Art The Canvas

- In Conversation: Memento Mori - Art & Fashion Forum by Grażyna Kulczyk Our Pick SHOWstudio

Related Artists

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Alexandra Duncan

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Antony Todd

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services Editing Proofreading Rewriting

- Extra Tools Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us About Us Testimonials FAQ

- Studentshare

- Visual Arts & Film Studies

- The Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols by David Bailly

The Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols by David Bailly - Essay Example

- Subject: Visual Arts & Film Studies

- Type: Essay

- Level: Ph.D.

- Pages: 3 (750 words)

- Downloads: 36

- Author: garryfeil

Extract of sample "The Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols by David Bailly"

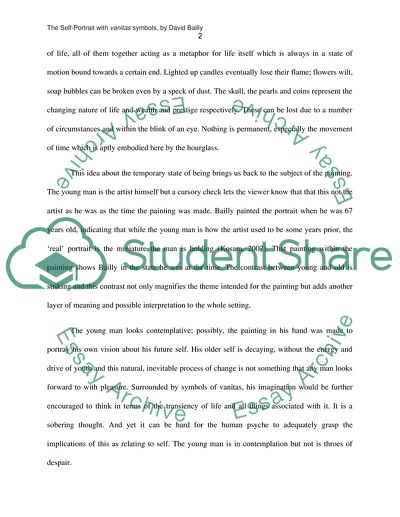

As much space is given to the objects as the subject of the painting, which is, ostensibly, the young man sitting beside the table. The interesting thing to note is that the young man (the painter himself) is not the only person in this ‘self-portrait’; he is holding a miniature painting in his hand with the depiction of a much older person in it. So, can this really be called a self-portrait? It would be implausible to consider that the objects in the painting exist in isolation.

These symbols of ‘vanitas’ have been selected to illustrate a uniform theme of the “swift passage of time and the terrible instability of life” (Duffy, 2012) in the painting. A style of painting popular in the 16th and 17th century, vanitas paintings were also known by another name of ‘memento mori' (remember death). All the symbols in the painting are objects in a transient state of life, all of them together acting as a metaphor for life itself which is always in a state of motion bound towards a certain end.

Lighted up candles eventually lose their flame; flowers wilt, soap bubbles can be broken even by a speck of dust. The skull, the pearls, and coins represent the changing nature of life and wealth and prestige respectively. These can be lost due to a number of circumstances and within the blink of an eye. Nothing is permanent, especially the movement of time which is aptly embodied here by the hourglass. This idea about the temporary state of bringing us back to the subject of the painting.

The young man is the artist himself but a cursory check lets the viewer know that that this, not the artist as he was at the time the painting was made. Bailly painted the portrait when he was 67 years old, indicating that while the young man is how the artist used to be some years prior, the ‘real’ portrait is the miniature the man is holding (Kosara, 2007). That painting within the painting shows Bailly in the state he was at the time. The contrast between young and old is striking and this contrast not only magnifies the theme intended for the painting but adds another layer of meaning and possible interpretation to the whole setting.

The young man looks contemplative; possibly, the painting in his hand was made to portray his own vision about his future self. His older self is decaying, without the energy and drive of youth and this natural, inevitable process of change is not something that any man looks forward to with pleasure. Surrounded by symbols of vanitas, his imagination would be further encouraged to think in terms of the transiency of life and all things associated with it.