A Beginner’s Guide to Finding User Needs

Qualitative research on user motivations, activities, and problems

Jan Dittrich

A Beginner’s Guide to Finding User Needs shows you how to gain an in-depth understanding of motivations, activities, and problems of (potential) users. The book is written for UX researchers, UX designers and product managers.

Contributors

- lisacharlotterost

- Claudia Landivar

Additional information and co-documentation templates can be found at urbook.fordes.de

Suggestions and Feedback

This book is free/libre, if you help to improve it, it helps all other fellow readers. To point out mistakes you can:

- file an issue (If you are on GitHub)

- write me a mail: dittrich.c.jan AT gmail DOT com

Payed and free versions of this book

- If you/your team/your company wants to buy this book and pay for my coffees, visit its page on leanpub .

- You can read this book for free at github pages or download versions for ebook readers on urbook.fordes.de

Research focused on understanding

This chapter covers:

- What qualitative research is about

- In which projects you can use qualitative research methods

- Why research is not a linear process

Although I am a user researcher since a while, every research project still brings a lot of surprises. What me and my colleagues want to know seems rather simple in the beginning, yet often turns out to be complex and surprising: “Oh, I did not see it this way, but it makes a lot of sense now”. These surprises and complexities lead to a better understanding of why (potential) users of a product do what they do.

This book is about methods for understanding people you design for and about communicating what you learned. The methods used for this are interviews, observation and structuring the data into meaningful patterns. This is sometimes called design ethnography . In such research, you directly engage with people and data you analyze is language- or image-based. This means you use qualitative methods .

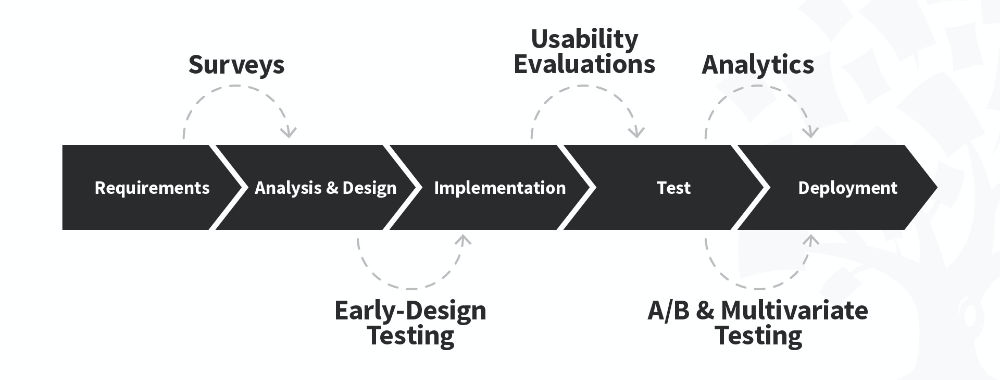

There are also research methods that use number-based data and focus on testing hypothesis using measurements and statistical analysis. These are often referred to as quantitative methods . A typical example for quantitative research is A/B testing: A/B testing compares two versions of an interface by measuring which of the versions performs better in a certain metrics e.g., how many people clicked the “buy”-button.

Note: Other research methods Maybe this book is not what you are interested in. Perhaps you rather want to learn about quantitative research using measurements and statistics. In this case, I recommend getting Jeff Sauro and James R. Lewis’ book “Quantifying the User Experience” . If you then crave yet more math and complex methods, try Andy Field’s “Discovering Statistics” and his “How to Design and Report Experiments” . If you are undecided whether you want to use qualitative or quantitative methods or just wonder what research methods exist, you can get an excellent overview and introduction to several methods with Erica Hall’s brief “Just Enough Research” or Goodman, Kuniavsky and Moed’s “Observing the User Experience”

Qualitative research helps you to get a holistic understanding of how a future product could be used by finding out about motivations, activities, and problems of users and gain an in-depth understanding for their activities, replacing stereotypical assumptions. For example, when people cook, it might be plausible to assume that:

- They decide what to eat

- Get a recipe for the meal

- Buy ingredients

- Cook following the recipe

But in everyday life, people often don’t follow this clear script: It will influence their actions that their kid or spouse prefer another food than they do; They might wish for variety; they might see something that they fancy even more than what they initially decided for; they might not trust their cooking skills… If you want to build a product that supports people when cooking or shopping groceries, it makes sense to understand how people actually do it. This does not mean that initial ideas or existing knowledge should be discarded: Concepts like “Programming is typing text that makes computers do stuff” or “Cooking is combining different groceries to get a meal” are not wrong . Such knowledge is just not rich enough to develop products based on it.

There are different ways in which such understanding can be helpful for a project. In the following sections, I show several typical setups in which qualitative research can help you to develop a product.

Types of projects you can use qualitative research in

It makes sense to understand motivations, activities, and problems of potential users before a lot of time and money has been invested in product development. You can do research to understand potential users without having a working product at all and find out what their motivations, activities, and problems are now.

Still, understanding-focused research can also make sense when product development is already ongoing, as long as this research can still influence the products further development. Depending on what is already set or not, there are different project types you can use understanding-focused research in.

Research for open topic exploration

Putting research at the very beginning of a project and having it as the primary driver puts the user needs first and gives you much freedom in your research, allowing you to focus directly on the user. An example would be to explore “Sharing recipes on the web” or “the future of cooking”. If you read case studies about design research led by famous agencies, you will read about this type of research. Such projects are not common: Often there are more constraints.

Research based on an idea for a new product or feature

You want to find out user motivations, activities, and problems that are important to consider when building a product or service. This is the scenario in which I use user need research most often, for example in tasks like “We would like to build an app that allows people to curate recipes and use recipes when cooking”. The research is shaped by the initial idea, but what will be created in the end is not yet certain.

Research based on an overhaul of a product or feature

If a team plans a substantial overhaul of a product, it makes sense to observe how users are using the product to find out where needs are not being met. A task could be “We provide an app for curating and reading recipes. It has not been updated in several years, and we want to increase its use among a younger target group by providing features that are attractive for them.” The research task is rather focused: What is to be done is already mostly set, but research shall shape the way it is done.

In all of these situations, understanding users can help to shape new products and features. But what the research focuses on, is shaped by the initial goals. These constraints are an important influence on your research project. Another important factor is the collaboration with others in the research project.

Researching alone and together

Researchers can collaborate with others in different ways: Researching as a contractor is different from the research as a member of a product team.

All methods in this book work well if you need to run the research on your own. But researching alone is not a requirement: Research can and should be done collaboratively, sharing both work load and gained knowledge.

The way of collaboration depends on your way of work. The following are three prototypical models for using the methods taught in this book: Research for you , research for a team, and research with a team.

Research for you

You can research even as a one-person-team—for example, if you are an entrepreneurial developer who wants to create a product yourself. Most entrepreneurial developers talk to others about the challenges they try to solve for their users and using the methods described in this book is similar, but more rigorous.

Researching by-you, for-you gives a lot of freedom but often has only tight resources and can easily lack structure.

Research for a team

Research for a team is a typical situation for many research contractors. You develop a research question, usually together with some key representatives of client; do the research; and deliver the results back to your client. Often, people hire contractors because they do not have a researcher on their team, because the workload is too high, or because they want an outsider to bring knowledge into the team. While there is some collaboration, particularly when creating a research question and when delivering the results, you will do a large part of the work by yourself.

Research with a team

Product development often involves several people and different roles. At least you have a product manager and developers, but you might also have UX designers, UI designers, market analysts, tech writers, and many more roles.

It is important to have a common direction. This is partly provided by communicating what you find out in your research. But even the best reports can not convey the rich impressions that one has when researching. Involving people directly as co-researchers can be very helpful: You can set them up with some simple tasks and as they learn, give them more responsibilities and help them to bring in their individual skills. For me, the most common way of collaboration is people being co-researchers in interviews. They help with taking notes, but depending on their skill and confidence, they also can shape the research themselves and, for example, ask questions.

Understanding is a messy process

In qualitative research, you are constantly dealing with new people and new situations. Uncertainty and surprises are therefore part of all projects. It has been my experience that dealing with these uncertainties is one of the biggest challenges for beginners.

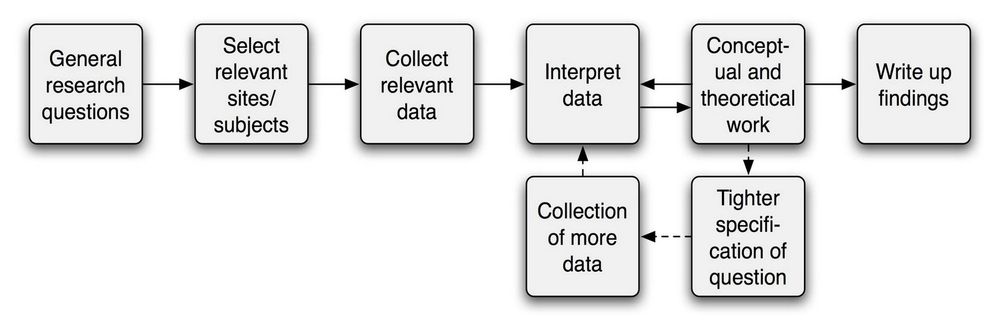

University teachers, conference speakers, and agencies often present research as finding clear facts with rigorous methods and execution of research in clear subsequent steps. Such models are very helpful for giving structure to your plans and actions, but they are idealized. It is helpful to keep this in mind.

When you do an actual research project, it won’t always follow a clear and linear structure. It will need iterations and adjustments. Don’t think of it failing to do “good research” when something does not go as planned. In fact, it is often a good sign if you feel that you need to adjust plans: It shows that you have learned something new and are aware of it. Plan in time for such adjustments. If your research project is only possible if everything runs very smooth, it might be at the risk of going over time and budget. Also, you and the team might not learn a lot of new things as you can only do what you have expected anyway.

- The methods discussed in this book focus on understanding and documenting the activities of people to design better products for them

- Research projects can vary in their constraints they put on research: They can be very open and explorative or suggest a solution already

- Research projects can vary in how you collaborate with other roles (or not): You can research for yourself, you can be part of a team you do research for, or you can be brought in

- Understanding-focused research methods can be challenging: Be prepared to learn new, surprising things and to adjust your plans

Preparing your research

- Defining what you want to find out in the research project

- Writing the questions you want to ask participants

- Learning about your research field before going there

- Recruiting participants for your research

- Preparing research sessions

- Preventing to harm participants or yourself

- Writing a cheat-sheet

It would be awesome if you could start with learning from people immediately. But before you meet your research participants, you need to do some preparation. It might not be the most glamorous part of being a researcher, but it is crucial to be well-prepared. Planning the research is important for you and your collaborators to get a common understanding of the research goals. The preparation is also useful for learning about the field you are going to do research in. This prepares you for the next step: finding potential participants and asking them if they would like to participate. As a researcher, you are responsible for the impact of your research—on society, on participants and on you. Anticipating this in advance prevents harm.

A good preparation will enable you to focus on learning from participants when the time comes, as you, your team and your participants will be well-prepared for the research. A good way to start with your research preparation is to get a clear understanding of what you and stakeholders of the project want to learn.

What do you want to learn?

The question of what you want to learn leads to two kinds of questions: research project questions and research session questions . Research project questions are about what the goal of the research project itself is. You will work towards that goal by learning from participants in your research. For this, you will ask your participants questions. These are the research session questions . They are questions focused on what the participants do or feel.

Before you work on the research session questions that you ask the participants in the research sessions, you should clarify the overall goal of the research project with your research project question .

Imagine, you are asked to support a company in finding out more about a business area they potentially want to move in: They currently publish content and recipes for cooking enthusiasts online and in a paper magazine. They would like to explore improving their offers to younger people who might not be cooking enthusiasts yet. You were brought in by their product manager. While your contract outlines the topic you should research, it is not yet clear what exactly you will work on in practice. For this, you create a research project question.

Writing a research project question

A research project question briefly outlines the question you want to explore in the research project. It is helpful to start your research project by writing a research project question as it will help you to think about your research and communicate it.

Research project question examples “How and why do students use digital media to learn better?” “How and why do people become Wikipedia editors?” “How and why do developers use Docker images in collaborative software development?”

There will be many situations in which your research touches on other people’s concerns. At least they will be interested in the purpose of your research: Curious colleagues and research participants will be happy to know what it’s about. Telling them your research project question is an efficient way to describe why you do the research. Some people have a stake in your research. They will not only be curious but want to ensure that your research helps them. This is most obvious when you’re researching for a client, but also when you are researching as part of a product team in your organization. A clear research project question helps to communicate the project’s goal. It also ensures that everyone understands what the research will be about.

In the example I use throughout the book, I’m researching for a client and I have at least one person with whom I should have a shared understanding of the research project question: The product manager.

The initial task proposal you are approached with might be vague or very broad. For example, the initial question could be “We want to find out how to appeal to younger people” or “Explore if an app for recipes is right for us”. While these are questions that the client has, they are still focused on a future product—but a product that does not exist yet, can’t be researched, so it makes sense to focus on (potential) users and how and why they do.

Here are the questions you should be able to answer before proceeding:

- “I think we do this to learn how people actually cook in practice”

- “We have been thinking about using videos in our app since quite some time, but it seemed too expensive. I wonder if we will find out that we actually should be doing that.”

- “There was a discussion if we actually want to move in this field and be more ‘tech’ and have this app.”

- “According to research we had done so far, a lot of younger people seem to have an interest in learning to cook better. However, most people we cater to are in their 40s to 50s, so I am unsure if it works for us.”

Even if you are researching for your own project, without a team, it can be helpful to ask yourself these questions and write down the answers.

The research project question should be concise. This can be difficult to achieve when many people with different interests are involved. To allow for input while keeping the research question short and simple, keep a visible “research interest backlog”, a table of smaller, specific questions and who asked them. This prevents the research question from becoming a long list of individual questions.

I have already mentioned that initial questions for a research project might be focused on the product rather than on (potential) users. Instead of dismissing the initial product focus, you transform these initial ideas and use them as a starting point to create a user- and activity-focused research project question:

- Take the initial idea for a future product (or market, or feature)

- Ask yourself why the product would be good for an activity people do.

- Take the activity from 2. and ask yourself how and why people do this activity.

- Refine the question.

Here is an example:

- The initial idea the team wants to explore is “creating an app that offers recipes and teaches cooking skills.”

- The related meaningful activity can be “Learning new cooking skills when cooking with recipes”

- Asking how and why I got to “How do people learn new cooking skills when cooking from recipes?”

- We can then refine the question a bit. The people we work with may not want to focus on enthusiasts but on people who have less cooking skills yet, given that enthusiasts are probably a more saturated market. So, we can refine the research question to: “How do people with low to intermediate existing cooking skills learn new skills when cooking from recipes?”

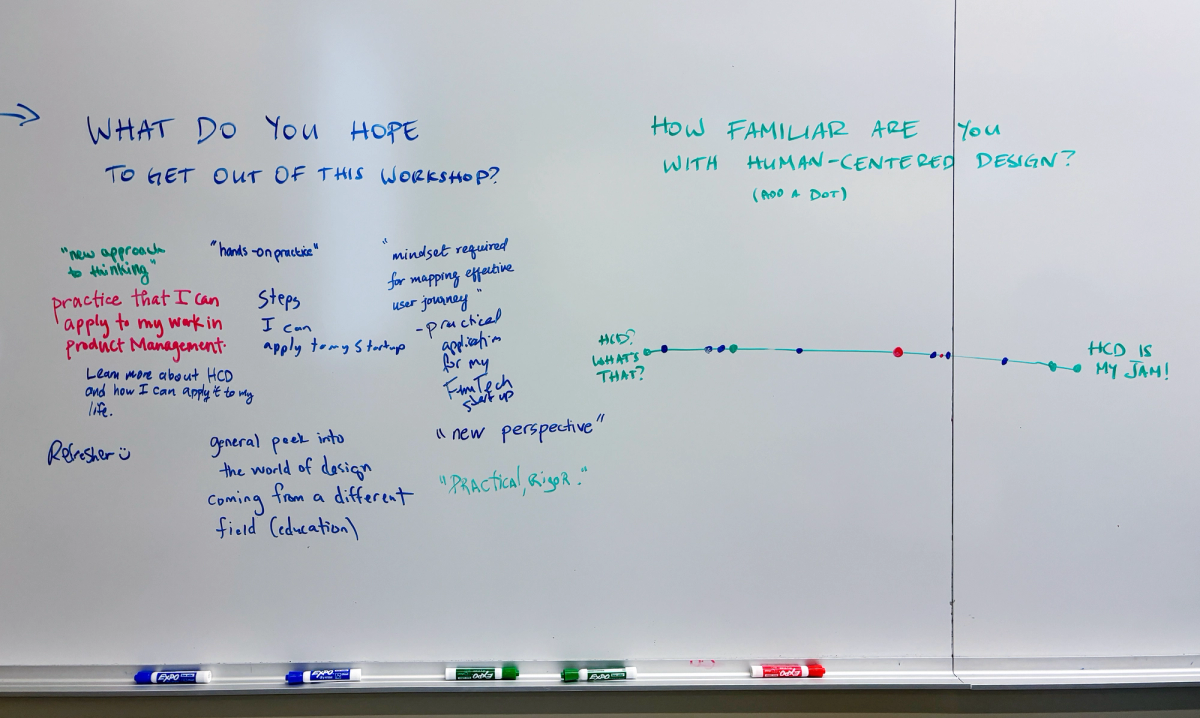

Tip: In many research projects, you might not just have several people who need to be involved in shaping the research project question. In this case, a research planning workshop might be helpful to gather input and to help the team to gain a mutual understanding of their interests.

The research project question serves to align, communicate and plan the research project. It is relevant to you and the people you work with, but it is not relevant to your direct work with participants in research sessions. What matters in research sessions are the research session questions.

Writing research session questions

The research session questions are the questions you want to ask participants, for example, “Can you tell me about how you cook?” They can also be invitations you want to give, like “Can you show me some recipes you like to use?” or “Can you show me around your kitchen?” Some of your questions are not voiced at all, you ask them yourself to guide your attention, for example, “Are there annotations in their recipes?”

You may have noticed that such questions don’t target specific, short answers typical of surveys, like “How much do you like your job on a scale from 1(I hate it) to 5 (I love it)?” or “Please name your most frequently used app”. Such surveys are usually analyzed quantitatively. In this book, I focus on understanding how and why people do what they do—qualitative research. I show you how to ask questions to which you can get in longer and more descriptive answers. By this, you will learn what you did not know before. Such questions are called open questions because they don’t have a pre-determined (closed) set of answers. Open questions are, for example, “Describe how you started your work today” or “Why did you add sugar to the dough?”

It makes sense to write down your research session questions. This helps you to remember what to ask and allows you to review and improve your questions. Writing down the session questions is also useful for collaborating with co-researchers: They might have good ideas about what could be asked and collaborating on the questions will help you to understand the motivations and strengths of your co-researchers.

When I start writing my research session questions, I often structure them around three themes: Motivations , Activities and Problems . They are relevant for design, and easy to remember with the mnemonic M-A-P .

Questions about motivations are concerned with what the participant wants to achieve and what is important to them. Motivations can give you context to what the participants do.

- “What is the most annoying thing about cooking?”

- “Can you tell me why you chose this recipe?”

- “What is a meal that you have not cooked yourself but would like to try?”

Questions about activities are about what the participant is doing and how they are doing it. Activities are the core of research; this is where the action takes place.

- [Invitation] “Shall we start with cooking?”

- [while observing] “How did you know the pan was hot enough?”

- “You said you are going to replace that ingredient—can you tell me more about that?”

Questions about problems are about what is getting in the way of what the participant wants to do. They can show opportunities to improve existing designs and can surface activities that are so familiar that participants don’t think about them—until something gets in the way.

- [question] “What is getting in your way when you cook?”

- [observation] Watch out for participants abandoning plans and finding new ways.

- [question] “What makes a ‘bad’ recipe?”

The research session questions are flexible and should be treated as a tool for reflection and preparation. There are usually more questions than can get answers to in any single research session.

Your session questions are not static. You should revise them as you learn more about the field. This can be done even before you speak to participants: By speaking with experts and doing desk research, you can learn about the field before you go there.

Get to know the field without going there, yet

A basic understanding of the field will help you to interpret what is going on. Otherwise, what you hear and observe can easily seem like an overwhelming amount of new terms, puzzling behaviors, and unspoken expectations. I’ll show you two ways to learn about a field before you go there: desk research and talking to experts.

Desk research

Desk research means you can do it from your desk by reading and summarizing reports, books, websites, and so forth. Ideally, you can start with easy-to-grasp introductions. For our example project, you could get some cookbooks for beginners and see how they teach cooking. It may also be worth watching some videos of people explaining cooking techniques to get a feel for how participant observation might be like.

Some areas have a lot of “onboarding material” like books, tutorials, and brochures—for example, parenting or web development. In other areas, documentation might be lacking, for example, because the field is highly professionalized (like being a pilot or a medical doctor), because some procedures are considered bad practice (like shortcuts to get work done quickly), or because the topic is considered not actually part of the discipline (like managing your finances as a freelance designer). Particularly for information on what actually happens aside of what is documented, experts might be a good source of information.

Talk to experts

Although searching the web for information is quick and easy, talking to an expert can help you answer specific questions and get tips on what to consider in practice.

Frequently, the team you work with already has some connections to experts: A company creating digital design tools will have close contact with some designers, and a company producing medical devices will have contact with medical doctors. Very often you can use these existing connections to reach out to experts who already have an established connection to your team or organization.

If you need to contact the expert without knowing them beforehand, you might get lucky, and they’ll talk with you for free. Otherwise, you’ll pay them for their time. What you have to pay varies and some experts are really expensive. But in general, talking to an expert is an efficient way to get an overview of a field and the relevant issues for practitioners.

Find people who participate in your research

Once you have written your research questions and learned about the field you want to research in, it is time to find people who participate in the research sessions. To be able to do this, you need to get in contact with them, ask if they could participate, and organize that participation. This is often referred to as “recruiting” research participants. You do this by defining criteria that potential participants should meet and by reaching out to them. You also need to set what you can pay participants for their work. Paying makes it easier to find people and makes your research more fair.

Define recruiting criteria

You are probably familiar with demographic recruiting criteria like “30-40-year-old male, earning more than $60k/year and being interested in technology.” However, your interest is in what people do and the problems they encounter. Demographic criteria are only spuriously related to that. This is why you should describe the potential research participants based on the activity that is part of our research project question.

In my example project, the research project question is “How do people with low to intermediate existing cooking skills learn new skills when they cook with recipes?”, so the activity is “Learning new cooking skills when cooking with recipes.” This is a good start, but it could be a bit easier to understand though: “People who want to improve their cooking skills and use recipes” is probably better, since potential participants could more easily relate to it and think: “Seems they are looking for people like me!”

Recruiting your potential research participants based on activities does not mean that you should ignore criteria that are not activities. Age, gender, ethnicity, and other criteria have a large influence on how people act. It will make your research more interesting and potentially more equitable if you include potential participants from a wide range of such criteria. You can set criteria for the diversity of the participants you involve in your research.

In my example project, I know that cooking, as a domestic activity, is usually associated with women. I could say, that I want at least a quarter of the participants to not be women. Similarly, if I would do research with programmers, it is a reasonable guess that many programmers are young, male, and white. Again, I can set criteria to have some participants older than 35, some non-male, and some non-white.

By defining your recruitment criteria along with the activities that are interesting for you ensures that you recruit participants who actually do what you want to learn more about. While activities are the primary criterion, demographics should not be ignored: Having a demographically diverse group of people makes it more likely to observe a wider range of ways people go about their activities.

Where does the research happen?

Research should take place where the participants are doing the activity you want to learn about. In the example project, I’m interested in how the participants cook with recipes, so their kitchen would be the place to do the research: There, they can talk about the context and show me what they do. I can experience the context and see how much space they have in their kitchen, how they use the space when cooking, and where they keep their recipes. Researching at the place where participants do the activities you are interested in, is called a site visit .

However, it is not always feasible to do the research at the site of the activity. For example, some workplaces have a strict no-visitors policy. Some audiences are distributed globally and long flights to each single participant would be very resource-intensive. In-person site visits are also not always the best way to gather data. For example, if almost all relevant interaction happens on a screen, talking and observing via video chat and screen-sharing might give you better opportunities to observe than looking over somebody’s shoulder in their office.

Knowing what your research project will be like and where the research is going take place is helpful when trying to find your participants for the research. You may also learn more about the field and the participants in the process of finding people and adjust the planned setup accordingly.

Payment and incentives

Payment for research (also called compensation or incentive ) is important for two reasons: It makes participating more attractive to participants and allows some participants to participate at all, for example, if they could not afford to interrupt their usual job for talking to you.

There are several factors that influence the amount you should pay participants:

- Time spent with you, time spent with organizing, time spent traveling.

- Living expenses for the participants: A compensation that is considered just about okay in a Swedish city might be considered high in rural India.

- People who are hard to recruit might be swayed by a larger compensation.

As a starting point, you can use an online calculator, like this one by ethnio , that gives you a suggestion for a sum to pay.

Ideally, you should pay your participants in cash as this poses the fewest restrictions on participants and does not require being a user of a specific service (like using PayPal or having a bank account). It may not be very relevant to research involving middle-class people in a Western country, but not everyone in the world has a bank account.

However, paying in cash is infeasible for many organizations. It may not be allowed or only be permitted for very small sums. Gift cards or vouchers are a common alternative. Sometimes, pre-paid VISA cards can also be a good choice. If your participants already use a product of yours, you can also reduce their monthly service fees for it or give them a free upgrade of their plan.

People might reject your compensation. In this situation, explain to them that they spend time on your questions that they are experts in what you want to learn about, and that it is only fair for them to be paid. Participants may not be allowed to take any compensation, for example, because they work for the government. If people reject the compensation or are not allowed to take it, it can be a nice alternative to instead offer to donate the money instead and let them choose from a list of well-known charities to choose where the money should go.

Tip: Sarah Fathallah’s article “Why Design Researchers Should Compensate Participants” discusses not only the “why” of compensation but also typically raised objections to compensation.

If your work is commercial, pay your participants. However, if you do research as a student or for a small NGO you might only have a very tight budget and people might be supportive of your cause already. If this is the case, I’ve had good experiences with giving a small gift to people—some premium chocolate bars or the like. The costs are relatively small and participants enjoyed the gift a lot.

Plan how many participants you need

There are no clear rules as to how many participants you need. However, most of my projects had more than three and fewer than twenty participants.

If you have done quantitative research in the past, this will seem like a very small number of people. Indeed, it is plausible to assume that user research with more participants is generally better in qualitative research as well. However, unless you invest more resources, more participants would mean shortening each research session, asking fewer questions, and skipping participant observation. But you need time with each participant if you want to understand how and why they work the way they do. To this end, several sessions in a hurry yield less useful results than research with one participant done right.

Nevertheless, doing research on only a very few users restricts the range of behaviors and opinions that will be reflected in your research. For example, you may not notice that different people have different preferred ways of doing activity. Also, you may not see which patterns are consistent across different people and which patterns vary.

My rule of thumb is to have 3 to 7 participants in each user group. Our user group in our example project would be people who have low to medium cooking skills and who cook with recipes. This means that if you want to learn about many groups of people, you also need more participants to cover these different groups. Our research question is currently focused on beginners, but we would need to recruit more people if we would also be interested in people who consider themselves cooking enthusiasts.

When estimating how many participants you need, consider how much time or money you can spend on doing the research. Each additional participant gives you additional data and a broader view of your potential users. However, each research session needs time and adds to the amount of data to be analyzed.

An efficient way to include the “right” number of participants is to do your research iteratively: start with two or three participants and analyze the data (How to do this is described in the section on analyzing data ). Take a look at the preliminary findings: If the results seem clear and consistent, you can do research with a few additional participants to refine and check and explore details; or, if time is up, leave it as it is.

If preliminary findings are unclear or contradictory, you may need to include more participants.

Reasons for such unsatisfactory results can be:

- The participants encompass different groups of people with different needs—For example, for cooking it may be important whether participants are parents who cook for their kids or whether they just cook for themselves.

- The topic of your research is too broad—for example, “How and why do people cook” would be very, very broad.

- Even if your research is focused and involves only one single group of participants, the actual patterns may just vary.

In all these cases you can include more participants—but try to check beforehand whether you…

- …need to clarify your research topic (to focus your efforts)

- …need to specify the group(s) involved more clearly (to recruit the right participants)

Coming from research based on measurements and statistics, refinement of criteria during research will feel very unusual or even like cheating. But qualitative research follows a different paradigm. The research I describe here aims at understanding and describing. To do this, it is not only fine but advantageous to do our recruiting iteratively, since we can build upon our improved understanding.

Recruit with an agency

Recruiting participants through an agency costs money but saves your work. It also means that you relinquish control of recruiting details. You provide the agency with your recruitment criteria (also known as screener ), how many participants you need, and when you want to conduct the research sessions. The agency will get back to you and tell you the cost and an estimate of when they will have found your participants.

Agencies usually have databases of possible participants. They filter their databases according to your criteria for the desired participants and will talk with them to find a time that works for them. The agency will typically get in touch with you after a few days and give you a list of names, times, and contact details of the participants.

Each recruiting agency is a little different, but they will tell you what they need—and they can answer your questions if you are unsure about something.

Recruit by Yourself

Recruiting by yourself might be needed when you do not have the budget to pay an agency or when it is easier for you to find participants than it is for an agency—for example, because you are familiar with the group of people you would recruit your participants from.

Let’s see what needs to happen for people actually joining your research:

- They know about the possibility of participating in the study.

- They are motivated to actually participate.

It is motivating for potential participants when the research improves their lives: A shopkeeper will likely be interested if you work on making it easier to keep track of bills; neighbors will be motivated to help when you try to make living in the neighborhood better. Another important factor can be being reimbursed for time and effort.

When you know what you can offer to potential participants, you can write down what they can expect when they participate. This includes:

- What the research will be about

- How much time it will take to participate

- What the research will be like/what you will do

- How the research results might benefit them or others

- What they get as an incentive

You can use this information to reach out to potential participants.

After speaking to the team you learn that you could recruit potential participants through the company’s website. When talking to a web developer in another team, you find out that the company could add a small recruitment banner to existing content and limit showing it to the geographic area you are located in. So you ask them to add to all recipes of the “Beginner” category a little banner that says: Participate in a study on cooking and recipes This leads to a page that says this: We would like to learn more about how people use smartphones and tablets/iPads for recipes and for learning to cook better. We’re looking for people who do not yet consider themselves cooking enthusiasts—so if you are still learning, that’s not only fine with us, but actually helpful! In the research, a member of our product development team would visit you and look over your shoulder while you cook. This would take approximately 1:30h. If you like to participate, please fill out this form: [contact form]

In the previous example, it was easy to reach out to participants because they were already using a product of the company you work for. But sometimes, field access is harder than just putting up some notes or banners. Often, this is because you actually don’t know where to find potential research participants yet. In this case, you first need to do some research to find them.

Here is an example for a scenario where accessing potential participants is more complex: Working with an NGO on using citizen science for environmental protection, you want to find out how people use freely available data on air pollution data, published by the city administration. However, you don’t know anyone who does work with such data. You give it a try and post about your research project on Facebook. A friend of yours answers. He happens to know that a local hackspace is hosting a bi-weekly data for good -meeting. The friend sends you a link. On the linked page, you find the meeting organizer’s email address. You write them an email and ask if you could join the meeting and introduce your project.

In the previous example, I outlined a step-by-step process of reaching out: In each step, you try to be referred to a next person who is more knowledgeable and familiar with the people you want to do research with. You do this, until you are referred to possible participants.

At each step, you can learn how to approach the next one: If your friend refers you to a meeting of data hackers, that friend can probably also tell you how you should present yourself and what you should avoid doing. Implicit rules are also relevant: For the hacker meeting, it might make sense NOT to wear a suit. In other places, the smart clothes might be helpful.

Some people who could help you are in a position that allows them to give or deny you access to potential participants. The ethnographic jargon for them is gatekeepers . They can decide to help you and let you through the metaphorical “gate” to your research field and your participants—or they can stop you, if they have reasons to do so. In the preceding example, a gatekeeper could be the person who runs the “data hackers” meetup or the person being responsible for the city’s open data initiative.

Once you have found people who would like to be your research participants, you can ask them if they know others who would also like to participate. This is also called “snowball sampling”.

In any case, it is useful to consider different ways to get to your participants. If one way fails (for example, friends of friends), you may be successful in another (such as writing a mail to a contact person of a community). In case several approaches work, you get more potential participants. But more importantly, you now have a more diverse group of people, leading to richer results.

Invite participants to the research sessions

When you have found people who want to participate, you can schedule the research sessions with them. If you are recruiting with an agency, the agency can do this for you, but since there are varying levels of support from agencies and because you may be recruiting by yourself, I will guide you through the whole process.

Let participants know what to expect and ask for their consent

To help attendees decide whether to participate in the research session, share information about what to expect and what you’re going to do with what you’ve learned. After the participants are informed about the project, they can decide to give their consent by signing a consent form.

However, treating it as just a form-to-be-signed hides that consent and the information given for it are a vital part of the communication between researcher and participant. You should shape the process of informed consent so that the participant is always in charge.

You should share relevant information and ask for consent early on. For examples, you can send the information about your project and the consent form a week ahead of the research session. This is better than presenting the information and consent form the first time at the beginning of the research session, with the clock ticking and the researcher expecting a “yes” gives the participant little autonomy, although it might suffice legally.

When preparing the information about the research project, I usually include the following information:

- What the research is about

- What the research will be used for

- What the research will be like

- If there are any risks that I am aware of

- How much time the research session will take

- What the participant gets in return

- That the participant can ask me at any time if they have questions about the research and a contact to do so

- How they can consent (that is, should they sign it on paper? Send me a mail?)

In the following example, keep in mind that the correct way for your research may look different.

Hello [Name], You said you were interested in taking part in a study. My team and I are trying to learn more about how people use recipes on their smartphones, tablets, or iPads. The research sessions would take place in your home and take about 60-90min, at a time when you will cook. It is very important to me and my colleagues that we do not test you in any way. There are no wrong answers or wrong approaches. There are no known risks of this research, but still: You can end the research session at any time without giving a reason. You will still get the compensation. I will record our conversation, which will help me to focus on our conversation instead of taking notes. I will only use the recording to supplement my notes. I will be the only one accessing the recording. What I learn from you will only be used to improve our products and nowhere else. You can ask the researcher questions during and before the research session. You can contact them under: [email protected] I have attached our consent form to this email. Please fill in the date and sign it with your name and send it back to me.

If signing a paper is not possible—for example because you are doing the research remotely—you can also ask the participant to send you an email with the text, “I have read the forms attached” or by having them write their name in a shared document or something like that.

With the consent information and form, I also send out a short survey.

At the beginning I usually ask which pronouns they prefer. This helps in the research session to address people properly and to represent them faithfully in the research results. You may think that you can guess people’s pronouns correctly from the name they used in a contact mail or from their appearance. But guessing by looks and getting it wrong can be embarrassing for you and hurtful for the participant, and guessing from name has its limits, too. Some names are not clearly gendered, particularly if you research across different languages and cultures. For example, Andrea might signify female gender to you, but people from Italy would expect it to signify male gender. So, it is easier to just ask.

Asking for pronouns What are your pronouns? He/Him She/Her They/Them Self-describe: _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

If there is no obvious risk associated with the research, I also ask how they want to be referred to in the study results. I usually give the choice between “Pick a name for me” and a free text field for their name with the note that it does not need to be their legal name.

Self-defining option for one’s name How would you like to be named when I talk about you in the research? Pick a name for me (pseudonymous) I would like to be named as: _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ (can be legal name or a nickname or any other name you like to used)

In many cases, it can be helpful to check for basic demographic variables too, like age ranges or where they live to ensure that your research is not accidentally excluding certain demographics. What is important here depends on your research topic. When you research in higher education, for example, you might want to ask if a person’s parents have already attended college; if you research around mobile apps you might want to know how familiar a person is with certain technologies, and so on.

Tip: Creating surveys, even if they are short, is not easy. If you know people who have experience with this, ask them to review your questions. If not, you can find best practices online that demonstrate established ways to ask commonly used questions.

Setting the date and time for the research session

If you recruit through an agency, they will usually take care of the coordination for you. If not, it is up to you to ensure that participants remember the time and place to meet. The following are some relevant aspects to keep in mind:

- Be clear about time and date : Even if it is a bit awkward, I try to be very clear about time and date. I mention the day of the week, day, month, and time in my mails or phone calls. If I research internationally, I also mention the time zone I talk about. In an email, that might look like: I could meet you on Monday, the 8th of November, 1pm (“Berlin time”/CET) . Sending a calendar invite is also helpful as the calendar apps automatically convert times, and it makes it easy for participants to set a notification.

- For remote meetings, be clear about the technology used : Most video chat software runs also in any modern browser, so people do not need to install a special software. Let participants know how they can join the call. If you use a software you are not familiar with, give it a test run first.

- For real-life-meetings, find out if there are any special requirements : Places have their own rules in many cases. I share what I expect with participants, so they can fill me in if the expectations would not match: “I will come to Big Street 6 and ring the bell for ‘Miller’” and maybe they tell you: “Oh, right, the bell has the name of my flat mate, Nguyen. So, ring there.”

Getting clarity on date, time, technology, and place helps you start the research session without problems when time comes. In the next section, I want to cover some less obvious issues. However, they can have dire consequences, and it is important to consider them.

Bad things that can happen—and how to prevent them

Research should yield helpful results, but even more importantly, it should not cause harm to you or the participants. “Harmful research” probably conjures up images of non-consensual experiments in medical research which feels very far distant from the research you are doing. But your research can also cause harm. By considering possible risks and avoiding or mitigating them, you can research ethically and in a way that does not harm you nor the participants.

Preventing harm to participants

As a researcher, you have experience in doing research and you can determine how you carry out the research. Participants have no experience in being participants nor can they easily control how the research is conducted. This makes it essential for you to plan ahead to prevent harm and make the research a good experience for your participants.

Participants should be well-informed and feel prepared before the research, they should have a good experience when they are in the research session with you and there should be a positive outcome for them afterward.

The participant does actual work to help you learn. They take time to participate in your research, keep that time free of other commitments, take care that they are there on time and last, but not least, they also do share knowledge and skills that often take a long time to acquire. This work they do should be honored. Paying them is one aspect of this. Another is to use the data well and not do research for research’s sake or because someone said that “more participants are better”. In order for participants to judge whether your research is fair for them, you need to share what the purpose of the study is and how you will reimburse them.

Participant autonomy

People should be free to choose to participate in your research and also what to share with you and how. This means that you may not get answers to all of your questions or may not observe everything you like to observe. You have to accept that.

Participant safety

Much of user need research is not particularly dangerous. Nevertheless, research that can cause physical harm indirectly (imagine researching how people navigate in traffic—distractions could lead to accidents) or research topics that are particularly sensitive (for example, researching with victims of crime). The concerns for participant autonomy are particularly important here, as people often know when something will cause them harm. However, they might not act on it in order to be a “proper research participant.” If you research in fields where physical or psychological harm is a possibility, it makes sense to speak with domain experts, particularly those from the group of potential research participants to get an assessment of your plans.

Protection of identity

There are many reasons why participants do not want to be identifiable. They may just do not want others to know that they are “bad at computers.” It also could be that you observe real work processes that are not exactly like their bosses dictate. For vulnerable populations, it might be the case that they have a stigmatized cognition (for example people having schizophrenia) or targets of law enforcement (such as undocumented immigrants). Thus, the identity of your participants should be protected. This can be achieved by not using their usual name but a made-up one and by describing your observations in a way that context clues do not reveal their identity.

For example, pseudonymizing research is a standard procedure: You replace the names of the participants with other names to protect their identity. However, being credited and being shown with one’s own name can also be important and a matter of pride for the skilled participants. In many research projects, I thus give people the opportunity to self-define how they want to be referred to in the research reports.

Note: Laws to protect personal data: GDPR and CCPA There are laws that protect participants’ personal data in many jurisdictions. The most relevant regulations are probably the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation . There are differences between them, but their basic idea is to give people control over their personal data and what can be done with it. This means that data can’t just be collected, stored, and used for whatever a company likes. Data needs to be collected for a specific purpose and then used for this purpose only. In addition, the personal data needs to be deleted again if it is not needed anymore or if former participants request it to be deleted. Personal data can be the person’s name, but also their email address, their age, and their gender. You use such data to get in contact with participants and to process incentive payments. Before you collect such data, you should have a plan for how to delete it. The organization you work with might also have faced similar questions before and a concept for handling personal data is already in place.

The safety of participants is essential. However, do not forget that research might also carry risks for you as a researcher.

Preventing harm to yourself

Just like the participants, you should not feel uncomfortable during the research. It is okay and professional to avoid research situations that are dangerous or just feel dangerous. Err on the side of caution.

In some situations, it may be safer to research together with another researcher or a colleague who likes to assist you. This way, you so can look out for each other. It is very common to have a main researcher and a note-taker, anyway. It is also fine to arrange to meet at places where you feel safer or to shift a meeting online so that both sides can call from whatever place they feel fine at.

Only a fraction of research topics are inherently debilitating, but in some projects, you might hear sad or shocking stories from participants. For example, if you are researching for a hospital you might hear about shocking diagnoses from participants. If you take on such a project, consider whether you are ready for it. It is professional to know your limits to refuse the job. If you are reading this book, you are probably a beginner in user research and may want to gather research experiences before researching inherently difficult topics. Personally, I would only take on such projects if I could collaborate with subject-matter-experts since there would be high risks for me and the participants.

Regardless of the topic of the research, it is important to take the time to process what you have learned. If you are conducting the research with other people, do a joint debrief after the research session and talk about what you learned. Hearing something sad or irritating can happen even with very mundane topics. Talking about it helps you to put it into context. Debriefs also jog one’s memory and you can use them to supplement notes without haste.

Beyond individual harm: Ethics of project outcome

Research can be a lot of fun and make you money. It can also be immensely motivating to be involved in the development of a new product. The culture of the tech industry is driven by the idea of being a force for good by creating greater efficiency, information, and connections with the technologies it introduces. User research is often part of creating these technologies—and what we enable with our research is also a question of ethics.

The technologies we help to develop also might do unjust things more efficiently, they might encourage the spread of false and inflammatory information or destroy existing social fabrics. User research can advance such developments, too. For example, research into people’s ideas of good social relationships can be used to make them spend more time on social media. Such research can be done perfectly ethically by itself, but its outcomes might not be ethical at all.

You too have to pay your bills and in many cases, it will not be possible only and always research on projects you are 100% aligned with. But be aware that technology has social consequences and that your research can be part of building that technology.

Write your cheat sheet

A cheat sheet is a little memory aid that you can take with you when you collect data. Most of the cheat sheet will be topics you want to explore and the questions that you want to ask.

Recipe use research cheat sheet User Code:_______ , Date: ________ Tell the reason for research: Learn about how people use their smartphones and tablets when cooking. Tell how the research session will be (asking, listening, observing; 60-90min) Ask to read the consent form again and sign if OK Intro [mutual introduction] “Can you tell me a bit about how and when you cook?” “Can you tell me about your use of recipes?” …

When writing the questions, start with the general topics and progress towards more specific ones. This is the order that makes sense over the course of a research session. Nevertheless, the sequence of questions is just a helpful guess. You will usually deviate a little (or a lot) from your cheat sheet.

I often include a checklist on the top, especially when it comes to legal matters, such as signing a consent form. That way, I can check off what I have already done and immediately see if I have forgotten anything.

You may be wondering about the “User Code” in the previous example. When I do research, I give every participant an identification code that can be used in place of their name (like “User2”). Later, when you publish the research, you want to retract all names and other identifying information. Such code allows you to identify participants without their names. This is useful for maintaining participant privacy. If you need to keep the names, you can keep a separate list that matches participant codes and legal names. This way, you can revert the codes if necessary. An alternative to codes is to ask participants how they would like to appear in the (published) research.

The cheat sheet is a tool that will support you during the interview and help you when your mind goes blank for a moment. It is not intended to ensure that you ask all questions in the same manner and in the same order. Rather than controlling the situation, qualitative research emphasizes exploring the situation. If the participant does or says something that is new to you, use it to learn, and feel free to come up with new questions that are not on the cheat sheet.

- Define what you want to learn in the research project by formulating your research project question .

- Define what you want to learn from participants by writing your research session questions .

- Get to know the field before you go there by desk research and asking experts.

- Recruit based on activities, not demographics.

- User need research is in-depth, with few participants.

- Pay users for helping you.

- Prevent harm by assessing the risks the research itself could pose to you and participants as well as the harm a product your research is helping to create could do.

- Write a cheat sheet with the questions you want to research, and what you want to observe and ask.

Learning from research participants

- Preparing your research sessions

- Observing, listening and co-documenting with research participants

- Collecting data for later analysis

You have prepared your research, arranged a meeting with a participant, and informed them of what to expect. Now you are ready to learn first-hand about the participant’s motivations, activities, and problems by meeting them, listening to their stories, and observing their work.

This chapter gives you guidance of how to learn best from your participant. A large part is about asking questions and guiding conversations. You are also interested in what people do . To learn about activities, your conversation is mixed with participants demonstrating their work. You take notes and pictures to aid your memory. Participants can take an active role and document their work: You can involve them in drawing diagrams of processes or social relations, to document their work together. At the end of the research session, you will summarize what you learned and give the participant an opportunity to ask questions. After the session ends, you will complement and organize your data. Only then is the research session over.

It is a common misconception about user research that it is asking what people want or how much they like a feature. But your research won’t delve into future ideas and designs—you are not going to ask “do you think that [a gadget] would help you?”

It is hard to guess if an imaginary thing would be great to have in the future. Instead of working with product ideas, you will learn the how and why of your participants’ activities. This allows you to evaluate your ideas (“Are my ideas consistent with what participants consider essential?”) and get inspiration for new ideas (“how can I support this activity?”).

See your participants as competent in what they do: they are experts in their daily work. This goes against the notion that people “don’t get it” and need help from designers and programmers. Assume participants have a reason for doing their work the way they do it. If you’re wondering about the actions of the participants, find out why they act the way they do.

Before you learn from the participant, let’s go over what you need to prepare.

Set up the research session

Preparing the research session prevents later problems. Send a reminder to participants and have your recording equipment ready.

Remind participants

It can be helpful for you and your participants to send a short reminder mail to participants the day before you meet them. (If you recruit via an agency, they might do it.) Here is an example:

Hello Sarah, I look forward to meeting you tomorrow at Small Avenue 123 at 12:00pm. If you have any questions, please feel free to reach contact me. Jan

If you are coming with a research partner, let the participant know, so they are not surprised if a second person comes. Also tell the participant know your research partner’s name and pronouns, so the participant can address them properly.

Prepare your note-taking and recording equipment

To collect data, you should have your recording equipment ready. This is what I usually bring along for in-person meetings:

- Printed Cheat sheet (I described how to write a cheat sheet in a previous section)

- Paper on clipboard : You might need to write on your lap or while standing.

- Pens or pencils : Whatever you like to use. If you plan to sketch or co-document with the participants, take some felt pens in black, red, and green along.

- Audio recorder : A simple device for about 50€ is sufficient. It should connect to your computer via USB or take micro SD cards, so you can transfer the files on your computer easily. More expensive models, like a Zoom H2 , have better microphones and more settings. You can also record with your phone if the quality is fine for you. Test it beforehand in an environment similar to where you will hold the research session.

When you meet online, the tools are different. In this situation, you should have the following prepared:

- Video-conferencing app : There are many of them. Which one you choose depends on your organization, potential legal restrictions (like GDPR ) and participant preferences.

- Headset : Often has better sound quality than the built-in microphone. If you want or need to use your built-in microphone, check how audible keystrokes and mouse clicks are—on some devices they drown out any other sounds!

- Printed cheat-sheet : Opening it on your computer would take up screen space that you might want to use for the video chat and notetaking.

- Writing on paper or computer : Both writing in a text file or writing on paper is fine. If you can touch-type, you can write notes and look at the camera.

- Whiteboarding-app : Whiteboarding apps like miro, mural, or tldraw are a remote equivalent to pens and sheets for collaborative activities. They’ve improved a lot in recent years, but ease of using pen and paper is still unmatched—your mileage may vary, especially for people who are not familiar with such tools.

Brief your research partner

If you are conducting research with a research partner, you should have a conversation about what you are going to do in the research session, how you want to divide tasks, and what you both should be aware of. Your research partner should also know when and where you are going to meet for the research session itself and if they should bring equipment.

It is common for research partners to be new to user research but curious about it. If your research partner does not have experience with user research, it is best if they start with supporting tasks like taking notes. In a later section I explain how to take notes, sketch, and make photos and audio recordings. It’s also good to show your research partner an example of notes from previous research. It may be unusual for them to make detailed notes instead of summarizing strongly. For example, they may only write “Likes the software” when the participant talks for a couple of minutes how they like to use a product. An example easily shows what you think the notes should look like.

As your research partner gains experience, they may take a more active role from time to time. If you think that your research partner can and should ask the participant questions, tell your research partner—otherwise they may not. Remember that, if the research partner takes an active role, you need to take the notes.

How to start the research session

When you arrive at the location you do the research at, greet the participant and take care the both you and your co-researcher (if present) are introduced to the participant. Usually, a short bit of small talk will follow. This is pretty normal and it happens intuitively. It helps to build trust and to get used to the research situation. But after a brief time both you and your participant will want to get started with your research session proper. You can initiate this by saying something like: “So… I’m happy that we can do this and that you could free some time for showing and telling me about your experiences with cooking with online recipes.”

Give some context of why that is interesting to you: “We are thinking about improving the usefulness of the recipes that we present to people. We have some enthusiasts in our community, but also a lot of people who do not consider themselves particularly good at cooking and we are wondering what we could do for them.”

Explain that you are here to learn—and not to judge the quality of the participant’s work: “…that’s why we would like to know more about how you cook and how you use recipes or videos for it. This is not a test. No matter if you cook elaborate meals or not: You are an expert in your kitchen, you know best what you need, and we like to learn more.”

Although you may have already described the time frame and the research method when recruiting the participant, tell them again what you will do: “We will talk about your work and will ask some questions. In addition, I’m interested in watching you cook. This is, as we talked when we had contact via mail, why we came slightly ahead of the usual time you prepare your meal. The whole process takes about an hour.”

In case they did not already agree to the consent form via email, you can use a written consent form and explain its purpose and content.

The participant must know how you record data and who will access it, even if they already agreed to recording before via mail. So, tell the participant: “I’d like to take notes, and, in addition, record audio—if you’re okay with that. The recording helps me to focus on your work, because then I don’t have to concentrate on writing everything down. A colleague and I will listen to the audio for transcription; We will anonymize the transcribed data before we share it with the product design team. If you feel uncomfortable with being recorded at any time, we can pause or stop the recording.”

In my experience, it is rare that someone does not agree to being recorded. If that happens, you can ask politely if they have any specific worries—they might agree when they have additional information about how the data is used and handled.

This is an example form an in-house research project, where I visited a programmer from another department in a larger company. After explaining the process, the participant said this: Participant : “Audio recording… I’m not sure…” Researcher : “That’s fine with me. May I ask what worries are?” Participant : “Hmm… yeah, aren’t you from HR?” Researcher : “I understand your concern. It is fine if you don’t agree to the audio recording. I can assure you that HR is a separate department. We work in the product department on internal tool, that is, we help to improve the applications you use to do your work. We do not share personal data and what we record today is not accessible to them. Also, any data that leaves my computer or the one of my colleague is anonymized, and we remove any data that points to you as person, including the names and so on.” Participant : “Oh, sure, them… I just assumed you were from HR and wouldn’t have liked the recording thing, you know.” It could have happened that the concerns of the participant were not resolved by me clarifying that I am not from Human Resources. If they were still fine with the research, but not with the recording—so be it. We would have taken notes instead: It’s their choice.

It goes without saying that it is important that you accommodate the participant’s wishes and respect their agency. There may be situations where the participant, for example, hesitates to respond or seems uneasy, possibly because of a question or a request of yours. Do not push them if they seem uncomfortable, even if you want to hear their answer. Offer them a way out of such situations if you unintentionally caused one. You can, for example suggest an alternative task or say that it is fine not to answer and go to the next question. The well-being of the participant is your primary concern.

Note: Dealing with difficult situations Most research sessions go smoothly—but if you are worried about being offhand in a sticky situation, I recommend “The Moderator’s Survival Guide” by Donna Tedesco and Fiona Tranquada: Bite-sized, actionable advice for all sorts of researcher problems.

Now you and the participant are ready to move into the conversation about the topics you want to learn about. To do this it’s helpful to consider how you can learn from the participant.

Methods to learn from participants

You can engage with participants in several ways: listening, observing, and co-documenting their activities. Each method has its own strengths, and provides insight into different aspects, so it’s common to combine different approaches.

Listening and asking questions

A common way of learning from a participant is by asking questions and listening to the participant’s answers. Aim for rich, story-like descriptions that about the user’s motivations, activities, and their context. To encourage the participant to provide such story-like answers, you often need to ask for descriptions of an activity and the reasons for doing it. So, your questions may be something like this: “Can you tell me why you chose this recipe?” or “You said you will brown the onions—how do you do that?”

Asking questions and getting answers from a participant is a very versatile tool. It can be done without many resources. In addition, you are not tied to a specific place, and you can talk about both past events and future plans.

However, it can happen that you hardly focus on actual experiences and instead talk about events in the abstract. Observations are therefore a good complement to asking questions and listening.

Only listening to people might not be the best way to understand what they are doing. Just like a picture is worth a thousand words, it is often helpful to ask participants to show what they talk about and to demonstrate how they work. Frequently, it is also easier for participant and researcher alike.

As you observe, you can notice things your participants would never consider to mentioning, because they’re second nature to them: The tools they use, how they apply these tools, and which problems they meet. But you can observe it. You also can learn about the context of their work, like means of communicating with colleagues or cues in the environment that point out problems—for example quick fixes on devices using tape and cardboard, or added instructions on machines.

It is not necessary to have observation as a separate step in the research process. It is best to interweave observation with asking questions and listening. For example, you can ask for a demonstration instead of a description.

If the participant tells you: “So, as I have the recipe opened here, and read through the list of things I need, I would now start getting out the ingredients” you could suggest: “Great—if it’s fine with you, let’s actually do that!”

Think of yourself as the participant’s apprentice. The participant is the expert who can teach you some of their skills. This means that understanding the participant by observing is not a passive process. Like an apprentice, you can and should ask questions.

You can ask about reasons , for example “You did measure the weight of the flour on the scale, but the for the water you just used a cup. Why?” Or ask about things you notice in the environment , for example: “Are there certain things you do at specific places?”

Teaching an apprentice is not a theoretical or artificially set-up process: The tasks you observe should be tasks that the participant is actually doing (and not something set up for you).

If the participant asks you “What should I do now?”, you can reply with “What would you do if I would not be here?”

Of course, what you observe should also be relevant to your interests. The conversation could continue in this way:

Participant : “I would either start to make this stir-fry vegetables, or actually, only heat something up for lunch and rather make some apple crumble for dessert” Researcher : “If you don’t have a preference, I would be curious to see how you make the apple crumble—I have not seen how people make dessert in our research, yet!”

From time to time, you might observe actions that seem wrong or at least not optimal: People might seem to ignore a feature that could make their work much more efficient, or they just never use a product that you focus your research interests on. Remain curious and don’t be judgmental. If you start judging and even possibly “correcting” their practices, you close yourself off to the reasons for the participant’s actions. Also, your participant would stop being open about showing you how they work.

Participants are experts in their work and have a reason for what they do. Maybe they do not want to be more effective because it would mean that their superiors would increase expectations, leaving no wiggle room for everyday contingencies. Maybe they routinely prevent situations from happening where they would need a certain technological solution and thus have no need for it.

Co-documenting

You can also document the work with the participant directly. I call this co-documenting because both you and the participant document some aspect of the participant’s life directly through drawing and writing. This can be as simple as asking the participant: “Draw a floor plan of your kitchen. Please highlight what is important for your work and write why!”

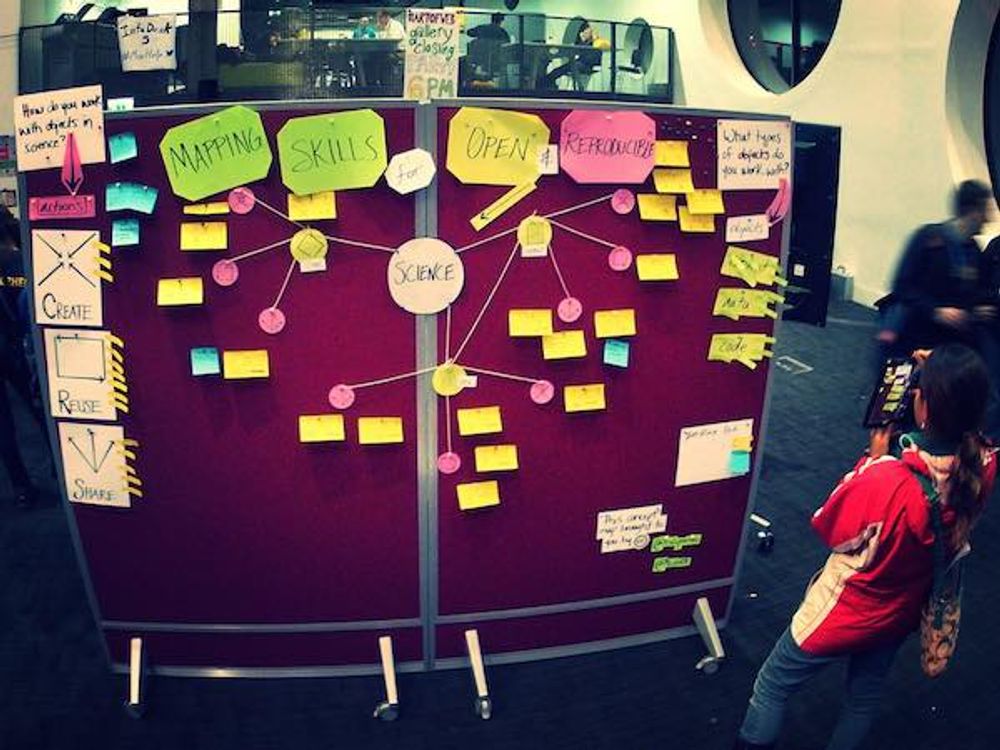

Here are examples of co-documenting results. Most of them are based on a template that guides the participant. To document the context of the participant, you can use a social space map as shown in the following figure . The participant is in the center, and they add who is relevant for them. Many participants do not limit themselves to people and might add institutions, roles, or technologies that are also important to them.

The timeline-diagram in the next figure is great for getting an overview of which parts of a longer process participants like and dislike.

The timeline-diagram usually covers a longer period of time from a bird’s eye view. Often, you also want to know details about a process. To do this, you can use a recipe-like list of steps, as shown in the next figure:

If you have the documentation in front of you and the participant, you can easily improve as you create it. You as a researcher, can refer to the documentation and ask for elaboration (“Is this the cupboard where you keep the ingredients?”).

The fact that researcher and participant both need to understand the documentation is a check against unclear terms, vague references, and sloppy handwriting. This makes the results accessible and useful.

A situation in which this is relevant could happen like this: