Advertisement

Introduction

How we investigate maha in a cancer patient, drug-associated tma, other differential diagnoses, how i treat microangiopathic hemolytic anemia in patients with cancer.

- Split-Screen

- Request Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

- Open the PDF for in another window

M. R. Thomas , M. Scully; How I treat microangiopathic hemolytic anemia in patients with cancer. Blood 2021; 137 (10): 1310–1317. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019003810

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Visual Abstract

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) with thrombocytopenia, suggests a thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), linked with thrombus formation affecting small or larger vessels. In cancer patients, it may be directly related to the underlying malignancy (initial presentation or progressive disease), to its treatment, or a separate incidental diagnosis. It is vital to differentiate incidental thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura or atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in cancer patients presenting with a TMA, as they have different treatment strategies, and prompt initiation of treatment impacts outcome. In the oncology patient, widespread microvascular metastases or extensive bone marrow involvement can cause MAHA and thrombocytopenia. A disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) picture may be precipitated by sepsis or driven by the cancer itself. Cancer therapies may cause a TMA, either dose-dependent toxicity, or an idiosyncratic immune-mediated reaction due to drug-dependent antibodies. Many causes of TMA seen in the oncology patient do not respond to plasma exchange and, where feasible, treatment of the underlying malignancy is important in controlling both cancer-TMA or DIC driven disease. Drug-induced TMA should be considered and any putative causal agent stopped. We will discuss the differential diagnosis and treatment of MAHA in patients with cancer using clinical cases to highlight management principles.

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) refers to a subgroup of hemolytic anemia where there is fragmentation and hemolysis due to damage of erythrocytes in the small blood vessels. It is characterized by the presence of red cell fragments or schistocytes on blood film review. Further evidence of hemolysis may include a reticulocytosis, raised lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), low or absent haptoglobin, and increased unconjugated bilirubin levels. MAHA may occur in isolation due to a direct effect on red blood cells, such as trauma due to mechanical heart valves or infections (eg, malaria or march hemoglobinuria), but it is more commonly seen as part of a thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA).

The combination of MAHA and thrombocytopenia (MAHAT) clinically defines the syndrome of a TMA. Clinical features are variable and will partly depend on the underlying diagnosis. 1 TMAs are characterized by endothelial cell activation and thrombus formation, leading to nonimmune hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and organ failure. Histological review reveals micro- and macrovascular thrombosis with thrombi varying in their composition depending on the cause of the TMA.

MAHAT in oncology patients may be directly related to the underlying cancer (either initial presentation or disease progression) or its treatment, or it may be a separate and incidental diagnosis. Although less common, it is vital to differentiate thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP) as quickly as possible, as it has a distinct treatment strategy, and early initiation of treatment has a critical impact on survival.

The diagnosis of cancer-associated TMA or chemotherapy-induced TMA is crucial, as the treatment in each case is to remove the driver of the condition (either the cancer or the drug) and avoid unwarranted therapies, such as plasma exchange (PEX), which has risk of potential complications .

Here, we describe our approach to the evaluation and management of the cancer patient with MAHA using illustrative case histories. Further references where readers can find more detailed information on specific diagnoses are included. This article is intended not to provide a thorough description of each syndrome or address still-debated topics but rather to focus on practical aspects.

A 69-year-old man with a background of congestive cardiac failure and atrial fibrillation on rivaroxaban presented with a short history of worsening fatigue. Physical examination was unremarkable. Full blood count showed hemoglobin 102 g/L; platelet count 26 × 10 9 /L; white blood cells 5.6 × 10 9 /L with a normal differential, and peripheral blood film examination showed a clear excess of red cell fragments with genuine thrombocytopenia and mild polychromasia. Further investigations revealed creatinine 88 μmol/L, LDH 1069 IU/L, and haptoglobin <0.1 g/L. Liver function tests showed bilirubin 26 μmol/L, alanine aminotransferase 86 IU/L, albumin 34 g/L, alkaline phosphatase 525 IU/L, coagulation screen prothrombin time (PT) 19.6 s, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) 31 s, and fibrinogen 1.45 g/L.

A clinical diagnosis of a TMA was made, and urgent PEX commenced pending investigations for the underlying cause. Anticoagulation was held given the thrombocytopenia. Pre-exchange ADAMTS13 activity result available the next day was normal, but a computed tomography (CT) scan of chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed a likely pancreatic primary tumor with sclerotic bone metastases, multiple hepatic metastases, and micronodularity within both lungs. PEX was stopped and oncology consult requested. He developed rapidly worsening coagulopathy and deteriorating liver function tests and was not suitable for biopsy and chemotherapy. There were no bleeding or thrombotic events. A fast-track discharge with community palliative care support was arranged, and he died on day 10 at home.

Investigations can be considered in 2 categories: (1) those to confirm fragmentation, hemolysis, and accompanying thrombocytopenia; and (2) those that help to elucidate the underlying cause ( Figure 1 ). TMA is defined clinically, based on standard laboratory investigations. Scoring systems, such as the PLASMIC score 2 or French scoring system, 3 can help to differentiate TTP from other TMAs. Definitive confirmation or exclusion of TTP can now occur in real time due to the widespread availability of commercial ADAMTS13 assays. ADAMTS13 activity levels <10% are diagnostic of TTP, while ADAMTS13 activity levels between 10% and 20% may rarely be seen in other conditions, such as severe sepsis, and require the presence of anti-ADAMTS13 immunoglobulin G autoantibodies to make a diagnosis of immune TTP.

Summary of the laboratory features in patients with TMA. A differential diagnosis of the causes of a TMA are included, focusing specifically on cancer or its treatment and a summary of treatments beneficial in the individual subgroups. abdo, abdomen; adenoCa, adenocarcinoma; aPL, antiphospholipid; DAT, direct antiglobulin test; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; ENA, extractable nuclear antigen; FBC, full blood count; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RF, rheumatoid factor; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; STEC, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli; U&E, urea and electrolytes; Vit, vitamin.

The degree of thrombocytopenia and lesser degree of renal injury in this case were in keeping with a possible diagnosis of TTP. The abnormal liver function test (LFT) results at presentation were not typical of TTP, although the patient had a history of previously mildly abnormal LFT results in an obstructive pattern, likely related to congestive cardiac failure. Similarly, the coagulation screen was not normal at presentation, but the patient was on rivaroxaban, which may cause prolongation of the PT. 4 There were no specific features in the presenting symptoms to suggest an underlying diagnosis of cancer, but the LFTs and coagulation were not normal, and CT scanning was warranted. PEX was appropriate as an initial measure, pending exclusion of TTP, but was stopped when the diagnosis of a cancer-induced TMA was made.

TMA may be driven directly by the underlying cancer as is seen here. This may be the first presentation of malignancy or seen in advanced disease. Two different mechanisms are postulated to be responsible and may coexist. Systemic microvascular metastases can cause MAHAT, as vessel obstruction by tumor cells leads to fragmentation of red cells and platelet consumption in the tumor emboli (the likely mechanism in this case). MAHAT may also be due to widespread bone marrow infiltration with cancer or secondary necrosis. 5-8

Most cases of cancer-associated TMA are secondary to solid organ tumors, but hematological malignancies such as lymphoma make up ∼8% of cases. 9 Intravascular lymphoma is a rare but recognized cause of hemolytic anemia and neurological disorders and may present with a TTP-like picture. 10,11 Gastric, lung, breast, and prostate cancers, primarily adenocarcinoma, are the most likely solid tumor diagnoses, with signet ring cell (mucin-producing) carcinoma being highlighted in several case reports. 12,13

In terms of clinical features, bone pain at presentation is well described in cancer-associated TMA and is not a feature of TTP, 14 likely related to cases with extensive bone marrow infiltration or secondary marrow necrosis. Respiratory symptoms (which are rare in TTP) occurred in >70% of cases of cancer-associated TMA in one case series. 15 Abnormal LFT results, moderate to severe renal dysfunction, or abnormalities of the coagulation screen are also seen more frequently in cancer-associated TMA than TTP. 5 Review of the blood film, an early bone marrow biopsy, and cross-sectional imaging may help expedite the underlying cancer diagnosis. 16 The blood film in cancer-associated TMA may show a leucoerythroblastic picture suggesting the diagnosis.

The initial treatment of MAHAT without a clear precipitant is PEX. PEX should be undertaken as soon as the diagnosis is considered, as TTP is a hematological emergency with high untreated mortality. The benefit of PEX in TTP has been established in a randomized controlled trial, 17 and PEX should be continued to clinical remission in patients with a diagnosis of TTP confirmed by ADAMTS13 testing. The requirement for ongoing PEX in other differential diagnoses will depend on the clinical response and results of additional laboratory investigations ( Figure 1 ).

No intervention is risk-free, and potential complications of PEX include those related to central line insertion, citrate toxicity, and reactions to plasma. 18 However, many of the tests to identify the etiology of the MAHAT picture should be available within 24 to 48 hours, and PEX can then be halted if another diagnosis is identified for which PEX has no benefit. If TTP is confirmed by demonstrating severe ADAMTS13 deficiency, then further targeted treatment is required with immunosuppression (steroids and anti-CD20 therapy), plus adjunctive caplacizumab (an anti-von Willebrand factor [anti-VWF] nanobody that blocks formation of VWF-platelet microthrombi). 19

Making the diagnosis of a cancer-associated TMA is crucial, as there is no beneficial role for PEX, steroids, or other immunosuppression that is used in TTP. Platelet transfusions may be given for severe thrombocytopenia in a case of cancer-associated TMA, based on the clinical picture and following usual platelet transfusion thresholds, unlike in TTP, where platelet transfusions are usually avoided because of risk of exacerbating microthrombotic complications. Treatment with chemotherapy has been associated with improved survival in cancer-associated TMA, 9 but many patients have an extremely limited prognosis, with nearly a 50% mortality rate within 1 month of diagnosis, 5,9,20 as highlighted in our case. His rapid death was probably not preventable, given the advanced stage of the cancer at presentation.

A 59-year-old man presented with a subglottic mass requiring a laryngopharyngectomy for squamous cell carcinoma, followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Four months later, he presented with vomiting and retrosternal chest pain. Blood tests showed hemoglobin 81 g/L, platelets 42 × 10 9 /L, reticulocytes 4.5%, and normal renal function. Schistocytes were noted on the blood film. He deteriorated rapidly, requiring intubation and ventilation and inotrope support. Further investigations revealed LDH 310 IU/L, APTT 49 s, PT 10.9 s, and fibrinogen 4.4 g/L. D-dimers were 23 900 μg/L fibrinogen equivalent units, C-reactive protein (CRP) 207 mg/L, and alkaline phosphatase 663 IU/L. ADAMTS13 activity was normal, and the patient continued with supportive care. His coagulation screen worsened to a PT of 17 s, APTT 55 s, and fibrinogen 0.5g/L. He was bleeding from the endotracheal tube and urinary catheter, and bruises were noted on his arms, legs, and torso. A CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed bilateral renal cortical infarcts, bilateral consolidation, and a large right-sided pleural effusion. A mass suspicious of metastatic cancer was noted in the upper lobe of his right lung. An occipital infarct was noted on the CT head. Aspiration of the pleural effusion, sent for culture, identified Streptococci milleri and Candida albicans. An echocardiogram was normal.

In this case, the initial picture based on routine blood counts and the acute clinical scenario suggested a TMA. However, the LDH was only mildly elevated, the CRP was high, and the coagulation screen was deranged and deteriorated.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a clinicopathological syndrome that can be precipitated in cancer patients by sepsis or driven by the disease itself. This patient had metastatic cancer and 2 confirmed infective agents, likely causing the DIC picture, with evidence of bleeding and thrombosis.

Thrombocytopenia is the initial and most sensitive sign of DIC, occurring in >90% of cases, and half of cases have platelet counts <50 × 10 9 /L. 21 The falling platelet count is associated with an increase in thrombin formation and fibrinolytic activity, resulting in raised D-dimers. There is variability in the results of the coagulation screen (PT and/or APTT). Clotting times are prolonged in 60% to 70% cases but may be normal or even shortened. Fibrinogen levels may be reduced but are not usually below the normal reference range unless the DIC is very severe. 21 This case demonstrates how fibrinogen levels were in the normal laboratory range in the earlier stages of DIC and that it is the progressive changes in these parameters that is more helpful in confirming the diagnosis of DIC. Use of scoring systems for DIC improves the accuracy of diagnosis. The International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis scoring system demonstrates >90% sensitivity and specificity and is associated with clinical outcome (ie, increased mortality). 21

Despite prolongation of coagulation parameters and thrombocytopenia, in cancer patients, the principal clinical feature may be thrombosis rather than hemorrhage, or, as in this case, both may occur simultaneously. Although not present in this case, severe sepsis-related DIC can be associated with reduced ADAMTS13 activity with increased large VWF multimers and related to the risk of acute kidney injury. 22 ADAMTS13 is synthesized in the liver; thus, any degree of hepatic failure may result in reduced ADAMTS13 activity. However, the levels of ADAMTS13 activity are not typically <10 IU/dL, as is the case in acute TTP.

Certain cancers are more likely to provoke DIC, particularly adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract (frequently signet ring cell type), pancreas, breast, prostate, or lung. Mucinous tumors may secrete enzymes that can activate factor X. 5 DIC occurs in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia, caused by release of procoagulants by abnormal promyelocytes 23 and also in acute monocytic leukemia.

Treatment of cancer-associated DIC is primarily of the underlying driver of the condition, be it the malignancy or sepsis. Patients may require blood product support if bleeding or requiring a procedure, aiming for a PT and APTT <1.5 upper limit of normal, fibrinogen >1.5 g/L, and platelets >50 × 10 9 /L. Adjunctive vitamin K may be used, especially if LFT results are abnormal, affecting coagulation factor production. Concurrently, initiation of low-molecular-weight heparin may be required, at least at thromboprophylactic levels, if the phenotype is predominantly thrombotic

Management in this case was therefore complex. There was no further therapy available for his cancer. Appropriate antibiotics based on sensitivities and antifungal therapy were initiated. Vitamin K was started 10 mg IV daily for 3 days, and 10 mL/kg fresh frozen plasma with cryoprecipitate was given. Further blood products were administered to improve the coagulation parameters, stop bleeding, and allow initiation of low-molecular-weight heparin, initially at prophylactic intensity and incremented based on laboratory tests and clinical findings. This case highlights a number of potential precipitants causing MAHA with a DIC picture, but treatments are supportive.

A 50-year-old man was diagnosed with myeloma, having previously been completely fit and well. He received 4 cycles of cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone, and carfilzomib and was continued on carfilzomib maintenance therapy. Fifteen months later, he presented with a 1-week history of nausea and reduced urine output, having had a normal full blood count and renal function the preceding week. On admission, hemoglobin was 89 g/L, platelets 18 × 10 9 /L, reticulocytes 1.05%, haptoglobin <0.1 g/L, LDH 3070 IU, CRP 24, urea 35.8 mmol/L, and creatinine 748 μmol/L; the coagulation screen was normal, but schistocytes was evident on a blood film. PEX and hemofiltration were initiated. ADAMTS13 activity was normal. His blood pressure was increased to 160/90. Carfilzomib was stopped. He received 5 daily PEX procedures with rapid resolution of his MAHA and normalization of the platelet count. He required ongoing renal replacement therapy on discharge and triple antihypertensive therapy. Four months later, his hematology parameters remained normal, creatinine 119 umol/L and eGFR 58mls/min off renal replacement therapy, but continued on antihypertensive therapy. His paraprotein was undetectable.

Proteasome inhibitors (PIs) are now known to be associated with a TMA, 24,25 at a rate greater than that of complement-mediated hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), which has an incidence of 1 or 2 per million. The clinical picture is comparable to HUS with more severe renal impairment than is usually seen in other TMAs.

PI-induced TMA can be a challenging diagnosis in patients with myeloma. The differential diagnoses for worsening thrombocytopenia include disease progression or myeloma therapy, while renal impairment is common in the myeloma patient with a wide differential. In these patients, an acute and unexplained thrombocytopenia, hemolysis, and renal failure (with hypertension), while the disease itself is under control, should lead clinicians to consider this complication. Monitoring of blood pressure during PI therapy is important, with prompt withdrawal of the medication if there is evidence of emerging TMA, given the timing of this complication cannot be predicted.

Currently, there are 3 FDA-approved PIs: bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib. Bortezomib, the first PI that was approved, is currently indicated for the treatment of patients with multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. Carfilzomib and ixazomib are indicated for the treatment of relapsed/refractory myeloma. The prevalence of TMA with carfilzomib is much higher than with bortezomib. 25 Isolated microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, without all the features of a full-blown TMA, was observed at very high rates in carfilzomib-treated patients in a recent case series where it occurred in 16 out of 24 patients (67%). 26 In this single-center cohort, 11 out of 16 patients had mild hemolysis with haptoglobin <0.1 g/L but no transfusion requirement; 5 out of 16 required transfusion, and 1 patient had a severe and subsequently fatal TMA. 26 Cases of TMA have also been reported with the newer generation of PIs such as ixazomib. 27

The most important principles of management of PI-induced TMA are cessation of the culprit agent, blood pressure control, and renal replacement therapy where required. The relative role of PEX and/or complement inhibition as part of the supportive management strategy in proteasome-induced TMA is not yet clear. PEX may be helpful in improving the hematology parameters, as is seen in complement-mediated HUS (CM-HUS, previously known as atypical HUS). 28

CM-HUS itself is initially a diagnosis of exclusion. The diagnosis is subsequently confirmed by the presence of mutations in the alternative complement pathway affecting its regulation, which are found in approximately two-thirds of cases. 29 Definitive treatment of CM-HUS, however, is with complement inhibition (eculizumab), and the earlier anticomplement therapy is started, the better the longer-term renal outcome. 30

Guidelines published by one US group on the management of PI-induced TMA argue against the use of PEX and for initial empiric treatment with eculizumab. 31 One group found C5b-C9 deposition on endothelial cells in culture exposed to plasma from patients with acute carfilzomib-induced TMA, potentially allowing identification of patients who could benefit from complement blockade. 32 However, further data are needed before any definitive recommendation about the role of these therapies in PI-induced TMA can be made.

Drugs are a rare but increasingly important cause of MAHA, usually in association with thrombocytopenia, and may cause TMA either by cumulative dose-dependent toxicity or an idiosyncratic reaction after development of drug-dependent antibodies. 33

Extremely rarely, a drug may be associated with true anti-ADAMTS13 antibody-mediated TTP. This has been described for the antiplatelet agent ticlopidine 34 and more recently as a possible association of the immune checkpoint inhibitors that are used to treat metastatic melanoma and other cancers and the immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide, which is used to treat multiple myeloma.

Three cases have been described in which patients developed immune TTP with ADAMTS13 inhibitors during checkpoint inhibitor therapy (1 case with ipilimumab and 2 cases with dual checkpoint inhibitor therapy [ipilimumab plus nivolumab]) that responded to PEX, steroids, and rituximab and cessation of the drug. 35-37 TTP with severe ADAMTS13 deficiency has been described in 5 cases of patients treated with lenalidomide, 4 of whom had detectable anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies, who were successfully managed with PEX, immunosuppression, and discontinuation of the drug. 38-40 While there is no direct evidence for a role of the drug as a cause of the anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies and hence ADADMTS3 deficiency, a wide variety of other immune-related adverse events have been reported with both checkpoint inhibitors and lenalidomide. 41

However, in the vast majority of cases of drug-associated TMA, the mechanism is not ADAMTS13 mediated, and clinical presentation involves primarily renal impairment in conjunction with MAHAT. Sudden onset of symptoms that recur with repeated administration of a drug should prompt consideration of an immune mechanism with a drug-dependent antibody. However, if there is slowly progressive kidney injury with MAHAT, then dose-dependent toxicity is more likely. 5

Some anticancer agents have long been associated with TMA. Probably the best described is gemcitabine, which causes cumulative dose-dependent toxicity, with damage predominantly to the renal endothelium. In a large national retrospective cohort of 120 French patients with gemcitabine TMA, diagnosis occurred after a median of 210 days of treatment and a cumulative dose of 12 941 mg/m 2 . 42 Ninety-five percent had MAHA, and three-quarters were thrombocytopenic. Almost all patients (97%) had an acute kidney injury, with dialysis required in 28%. 42

TMAs occurring after vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors (eg, bevacizumab) are a relatively common complication in oncology. 43 Proteinuria is the earliest feature, followed by hypertension and renal failure. Cytopenias are seen with MAHA. The mechanism is dose-dependent toxicity and renal biopsy demonstrates microthrombi limited to glomerular capillaries with glomerular basal membrane alterations due to VEGF inhibition in podocytes. 43 Treatment consists of stopping the culprit agent, and the outcome is usually favorable.

Oxaliplatin therapy is associated with the formation of drug-dependent antibodies against platelets and erythrocytes, and an acute onset immune-mediated TMA is well recognized. 33,44,45 A list of other drugs used in the setting of cancer that have been associated with MAHAT, with potential mechanisms and management strategies, is given in Table 1 .

Drugs used in the setting of cancer and associated with MAHA

Ab, antibody; EGFR, endothelial growth factor receptor; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin.

When evaluating oncology patients with MAHA, their anticancer therapy and other drugs should be considered as a possible cause and any potential culprit agent stopped immediately. This may be difficult in those therapies resulting in TMAs following a cumulative drug dose. The differential between cancer-associated TMA, chemotherapy-associated TMA, and CM-HUS can be challenging, as all are diagnoses of exclusion and none are associated with severe ADAMTS13 deficiency.

There is a very limited role for PEX in drug-associated TMA, as only a small proportion of cases (those related to ticlopidine and potentially the immune checkpoint inhibitors or the immune modulatory drug lenalidomide) have antibodies against ADAMTS13 .

There are an increasing number of case reports of anticomplement therapy being used in the management of drug-associated TMA, particularly where the mechanism is dose-dependent toxicity, as seen with gemcitabine and mitomycin C, given the similarity of the presentation with CM-HUS. 42,46-49 Some groups have identified mutations or polymorphisms in complement regulatory genes in patients who respond, suggesting a role for complement dysregulation in the underlying pathophysiology. 50 Further data are needed before any definitive recommendation about the role of complement inhibition in subgroups of drug-induced TMA can be made.

Transplant-associated TMA (TA-TMA) may affect allogeneic haemopoietic cell transplant (allo-HCT) or solid-organ transplant patients. The following discussion centers around our management approach to TA-TMA as a complication of allo-HCT. TA-TMA is associated with a high mortality, no definitive diagnostic criteria, and therapy limited to supportive care, with no beneficial role for PEX. 51 It presents with MAHAT, and renal dysfunction, hypertension, and neurological features such as seizures are common organ-related symptoms. 52 Diagnosis of TA-TMA may be difficult, especially in the setting of conditioning-related cytopenias. 53

There are a number of factors that contribute to and may have an additive effect resulting in endothelia cell injury. These include the conditioning therapy, HLA-associated mismatches (particularly in unrelated donors), and high therapeutic levels of calcineurin inhibitors used to prevent graft rejection. Additional infections, especially viruses such as adenovirus or cytomegalovirus, need to be excluded and treated. Proteinuria, raised LDH, and hypertension have been used as prognostic factors and associated with increased mortality. 52

PEX has not been shown to demonstrate a positive benefit in TA-TMA, but reduction or using an alternative immunosuppressive regimen to prevent graft-versus-host disease and treatment of coexisting infections, meticulous blood pressure control, and general supportive therapy. More recently, as serological, cellular, and genetic evidence of complement activation has been demonstrated in TA-TMA, 54,55 the use of eculizumab has been increasingly reported. 56 Newer agents have also been used that target nitric oxide pathways. 51 However, it is becoming clear that not all allo-HCT TA-TMA is complement driven; thus, identifying a reliable biomarker that can ascertain these cases will be helpful in directing therapy. 53,57

In contrast, recurrent TMA after renal transplant may represent recurrence of CM-HUS (atypical HUS) or related to calcineurin inhibitors and should be managed accordingly.

Infections may present with MAHAT and are particularly relevant in patients who are immunosuppressed because of chemotherapy. TTP with severe ADAMTS13 deficiency may be a presentation of HIV. Many other infections may present with a MAHA and low platelets, such as adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, or even tuberculosis, and differential diagnosis requires not only a careful history but also detailed microbiological and virology investigations. Treatment requires the appropriate antimicrobial therapy. 58

Severe vitamin B12 deficiency may cause anemia with significant red cell fragmentation, and LDH levels are often markedly elevated. The condition may mimic a TMA with severe thrombocytopenia, but the issue is ineffective hematopoiesis with low reticulocytes, and the thrombocytopenia is due to a failure of bone marrow production. The presentation may be difficult to distinguish from TTP, and PEX has even been initiated in some cases. 59 Other causes of a MAHA include malignant hypertension and autoimmune conditions such as vasculitis or lupus nephritis. Management of these other causes of MAHAT involves treating the underlying condition (eg, blood pressure control for malignant hypertension), and PEX should be discontinued.

In conclusion, the differential diagnosis of MAHAT in patients with cancer is wide. Early exclusion of TTP is essential, but it is the subsequent diagnosis that drives appropriate management. PEX is not effective in many of the causes of TMA seen in cancer patients, and, where feasible, treatment of the underlying malignancy is important in controlling both cancer-associated TMA and DIC driven by the disease. The possibility of drug-associated TMA should be considered and any potential causative medication stopped. There is emerging evidence for the potential role of complement inhibition in selected cases of drug-associated and TA-TMA.

Contribution: M.R.T. and M.S. wrote the paper and reviewed the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: M. Scully, University College London Hospitals, 250 Euston Rd, London, nw1 2pg, United Kingdom; e-mail: [email protected] .

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Email alerts

Affiliations.

- Current Issue

- First edition

- Collections

- Submit to Blood

- About Blood

- Subscriptions

- Public Access

- Permissions

- Blood Classifieds

- Advertising in Blood

- Terms and Conditions

American Society of Hematology

- 2021 L Street NW, Suite 900

- Washington, DC 20036

- TEL +1 202-776-0544

- FAX +1 202-776-0545

ASH Publications

- Blood Advances

- Blood Neoplasia

- Blood Vessels, Thrombosis & Hemostasis

- Hematology, ASH Education Program

- ASH Clinical News

- The Hematologist

- Publications

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Thrombotic Microangiopathy with Polymyositis/Dermatomyositis: Three Case Reports and a Literature Review

Affiliation.

- 1 Division of Rheumatic Diseases, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Japan.

- PMID: 30068898

- PMCID: PMC6120848

- DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.0512-17

Thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs) rarely accompany polymyositis/dermatomyositis. We treated three patients with dermatomyositis combined with TMA. A literature review identified 13 previously reported cases. Exacerbation of myositis at the time of the TMA onset was observed in 62.5% of all patients, suggesting that the TMA onset may be associated with autoantibody production. We also found that cases of TMA with polymyositis/dermatomyositis often had a poor treatment response rate (37.5%). Furthermore, even if treatment was effective, the mortality rate associated with subsequent complications was high, and the survival rate was low (18.8%). Therefore, careful attention should be paid to patient management after TMA treatment.

Keywords: hemolytic-uremic syndrome; polymyositis/dermatomyositis; thrombotic microangiopathies; thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Dermatomyositis / complications*

- Dermatomyositis / mortality

- Dermatomyositis / therapy

- Middle Aged

- Polymyositis / complications

- Thrombotic Microangiopathies / complications*

- Thrombotic Microangiopathies / mortality

- Thrombotic Microangiopathies / therapy

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

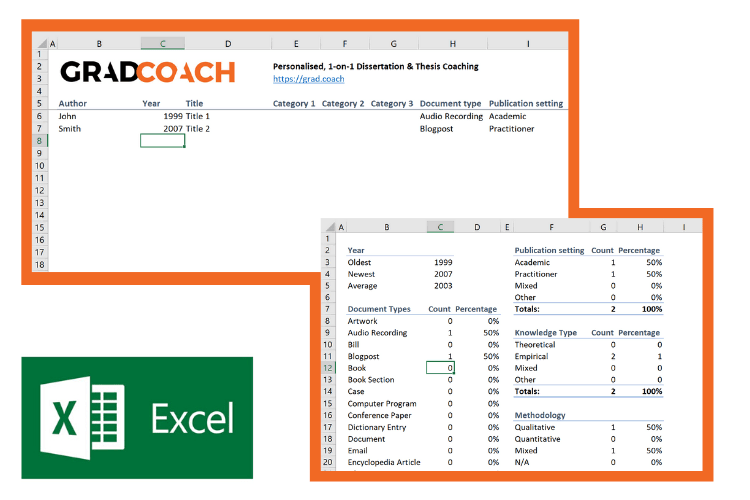

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

- How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

- Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

- Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

- Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

- Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

- Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

- Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

How to write a good literature review

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.