Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

A conversation with a Wheelock researcher, a BU student, and a fourth-grade teacher

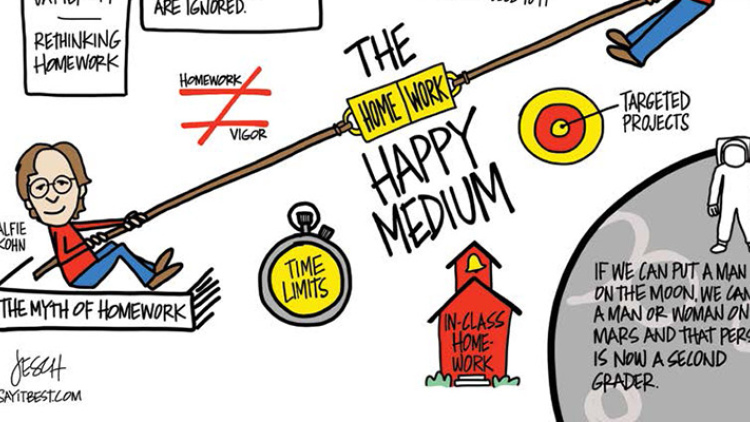

“Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives,” says Wheelock’s Janine Bempechat. “It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.” Photo by iStock/Glenn Cook Photography

Do your homework.

If only it were that simple.

Educators have debated the merits of homework since the late 19th century. In recent years, amid concerns of some parents and teachers that children are being stressed out by too much homework, things have only gotten more fraught.

“Homework is complicated,” says developmental psychologist Janine Bempechat, a Wheelock College of Education & Human Development clinical professor. The author of the essay “ The Case for (Quality) Homework—Why It Improves Learning and How Parents Can Help ” in the winter 2019 issue of Education Next , Bempechat has studied how the debate about homework is influencing teacher preparation, parent and student beliefs about learning, and school policies.

She worries especially about socioeconomically disadvantaged students from low-performing schools who, according to research by Bempechat and others, get little or no homework.

BU Today sat down with Bempechat and Erin Bruce (Wheelock’17,’18), a new fourth-grade teacher at a suburban Boston school, and future teacher freshman Emma Ardizzone (Wheelock) to talk about what quality homework looks like, how it can help children learn, and how schools can equip teachers to design it, evaluate it, and facilitate parents’ role in it.

BU Today: Parents and educators who are against homework in elementary school say there is no research definitively linking it to academic performance for kids in the early grades. You’ve said that they’re missing the point.

Bempechat : I think teachers assign homework in elementary school as a way to help kids develop skills they’ll need when they’re older—to begin to instill a sense of responsibility and to learn planning and organizational skills. That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success. If we greatly reduce or eliminate homework in elementary school, we deprive kids and parents of opportunities to instill these important learning habits and skills.

We do know that beginning in late middle school, and continuing through high school, there is a strong and positive correlation between homework completion and academic success.

That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success.

You talk about the importance of quality homework. What is that?

Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives. It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.

What are your concerns about homework and low-income children?

The argument that some people make—that homework “punishes the poor” because lower-income parents may not be as well-equipped as affluent parents to help their children with homework—is very troubling to me. There are no parents who don’t care about their children’s learning. Parents don’t actually have to help with homework completion in order for kids to do well. They can help in other ways—by helping children organize a study space, providing snacks, being there as a support, helping children work in groups with siblings or friends.

Isn’t the discussion about getting rid of homework happening mostly in affluent communities?

Yes, and the stories we hear of kids being stressed out from too much homework—four or five hours of homework a night—are real. That’s problematic for physical and mental health and overall well-being. But the research shows that higher-income students get a lot more homework than lower-income kids.

Teachers may not have as high expectations for lower-income children. Schools should bear responsibility for providing supports for kids to be able to get their homework done—after-school clubs, community support, peer group support. It does kids a disservice when our expectations are lower for them.

The conversation around homework is to some extent a social class and social justice issue. If we eliminate homework for all children because affluent children have too much, we’re really doing a disservice to low-income children. They need the challenge, and every student can rise to the challenge with enough supports in place.

What did you learn by studying how education schools are preparing future teachers to handle homework?

My colleague, Margarita Jimenez-Silva, at the University of California, Davis, School of Education, and I interviewed faculty members at education schools, as well as supervising teachers, to find out how students are being prepared. And it seemed that they weren’t. There didn’t seem to be any readings on the research, or conversations on what high-quality homework is and how to design it.

Erin, what kind of training did you get in handling homework?

Bruce : I had phenomenal professors at Wheelock, but homework just didn’t come up. I did lots of student teaching. I’ve been in classrooms where the teachers didn’t assign any homework, and I’ve been in rooms where they assigned hours of homework a night. But I never even considered homework as something that was my decision. I just thought it was something I’d pull out of a book and it’d be done.

I started giving homework on the first night of school this year. My first assignment was to go home and draw a picture of the room where you do your homework. I want to know if it’s at a table and if there are chairs around it and if mom’s cooking dinner while you’re doing homework.

The second night I asked them to talk to a grown-up about how are you going to be able to get your homework done during the week. The kids really enjoyed it. There’s a running joke that I’m teaching life skills.

Friday nights, I read all my kids’ responses to me on their homework from the week and it’s wonderful. They pour their hearts out. It’s like we’re having a conversation on my couch Friday night.

It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Bempechat : I can’t imagine that most new teachers would have the intuition Erin had in designing homework the way she did.

Ardizzone : Conversations with kids about homework, feeling you’re being listened to—that’s such a big part of wanting to do homework….I grew up in Westchester County. It was a pretty demanding school district. My junior year English teacher—I loved her—she would give us feedback, have meetings with all of us. She’d say, “If you have any questions, if you have anything you want to talk about, you can talk to me, here are my office hours.” It felt like she actually cared.

Bempechat : It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Ardizzone : But can’t it lead to parents being overbearing and too involved in their children’s lives as students?

Bempechat : There’s good help and there’s bad help. The bad help is what you’re describing—when parents hover inappropriately, when they micromanage, when they see their children confused and struggling and tell them what to do.

Good help is when parents recognize there’s a struggle going on and instead ask informative questions: “Where do you think you went wrong?” They give hints, or pointers, rather than saying, “You missed this,” or “You didn’t read that.”

Bruce : I hope something comes of this. I hope BU or Wheelock can think of some way to make this a more pressing issue. As a first-year teacher, it was not something I even thought about on the first day of school—until a kid raised his hand and said, “Do we have homework?” It would have been wonderful if I’d had a plan from day one.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

Senior Contributing Editor

Sara Rimer A journalist for more than three decades, Sara Rimer worked at the Miami Herald , Washington Post and, for 26 years, the New York Times , where she was the New England bureau chief, and a national reporter covering education, aging, immigration, and other social justice issues. Her stories on the death penalty’s inequities were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and cited in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision outlawing the execution of people with intellectual disabilities. Her journalism honors include Columbia University’s Meyer Berger award for in-depth human interest reporting. She holds a BA degree in American Studies from the University of Michigan. Profile

She can be reached at [email protected] .

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 81 comments on Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

Insightful! The values about homework in elementary schools are well aligned with my intuition as a parent.

when i finish my work i do my homework and i sometimes forget what to do because i did not get enough sleep

same omg it does not help me it is stressful and if I have it in more than one class I hate it.

Same I think my parent wants to help me but, she doesn’t care if I get bad grades so I just try my best and my grades are great.

I think that last question about Good help from parents is not know to all parents, we do as our parents did or how we best think it can be done, so maybe coaching parents or giving them resources on how to help with homework would be very beneficial for the parent on how to help and for the teacher to have consistency and improve homework results, and of course for the child. I do see how homework helps reaffirm the knowledge obtained in the classroom, I also have the ability to see progress and it is a time I share with my kids

The answer to the headline question is a no-brainer – a more pressing problem is why there is a difference in how students from different cultures succeed. Perfect example is the student population at BU – why is there a majority population of Asian students and only about 3% black students at BU? In fact at some universities there are law suits by Asians to stop discrimination and quotas against admitting Asian students because the real truth is that as a group they are demonstrating better qualifications for admittance, while at the same time there are quotas and reduced requirements for black students to boost their portion of the student population because as a group they do more poorly in meeting admissions standards – and it is not about the Benjamins. The real problem is that in our PC society no one has the gazuntas to explore this issue as it may reveal that all people are not created equal after all. Or is it just environmental cultural differences??????

I get you have a concern about the issue but that is not even what the point of this article is about. If you have an issue please take this to the site we have and only post your opinion about the actual topic

This is not at all what the article is talking about.

This literally has nothing to do with the article brought up. You should really take your opinions somewhere else before you speak about something that doesn’t make sense.

we have the same name

so they have the same name what of it?

lol you tell her

totally agree

What does that have to do with homework, that is not what the article talks about AT ALL.

Yes, I think homework plays an important role in the development of student life. Through homework, students have to face challenges on a daily basis and they try to solve them quickly.I am an intense online tutor at 24x7homeworkhelp and I give homework to my students at that level in which they handle it easily.

More than two-thirds of students said they used alcohol and drugs, primarily marijuana, to cope with stress.

You know what’s funny? I got this assignment to write an argument for homework about homework and this article was really helpful and understandable, and I also agree with this article’s point of view.

I also got the same task as you! I was looking for some good resources and I found this! I really found this article useful and easy to understand, just like you! ^^

i think that homework is the best thing that a child can have on the school because it help them with their thinking and memory.

I am a child myself and i think homework is a terrific pass time because i can’t play video games during the week. It also helps me set goals.

Homework is not harmful ,but it will if there is too much

I feel like, from a minors point of view that we shouldn’t get homework. Not only is the homework stressful, but it takes us away from relaxing and being social. For example, me and my friends was supposed to hang at the mall last week but we had to postpone it since we all had some sort of work to do. Our minds shouldn’t be focused on finishing an assignment that in realty, doesn’t matter. I completely understand that we should have homework. I have to write a paper on the unimportance of homework so thanks.

homework isn’t that bad

Are you a student? if not then i don’t really think you know how much and how severe todays homework really is

i am a student and i do not enjoy homework because i practice my sport 4 out of the five days we have school for 4 hours and that’s not even counting the commute time or the fact i still have to shower and eat dinner when i get home. its draining!

i totally agree with you. these people are such boomers

why just why

they do make a really good point, i think that there should be a limit though. hours and hours of homework can be really stressful, and the extra work isn’t making a difference to our learning, but i do believe homework should be optional and extra credit. that would make it for students to not have the leaning stress of a assignment and if you have a low grade you you can catch up.

Studies show that homework improves student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicates that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” On both standardized tests and grades, students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school.

So how are your measuring student achievement? That’s the real question. The argument that doing homework is simply a tool for teaching responsibility isn’t enough for me. We can teach responsibility in a number of ways. Also the poor argument that parents don’t need to help with homework, and that students can do it on their own, is wishful thinking at best. It completely ignores neurodiverse students. Students in poverty aren’t magically going to find a space to do homework, a friend’s or siblings to help them do it, and snacks to eat. I feel like the author of this piece has never set foot in a classroom of students.

THIS. This article is pathetic coming from a university. So intellectually dishonest, refusing to address the havoc of capitalism and poverty plays on academic success in life. How can they in one sentence use poor kids in an argument and never once address that poor children have access to damn near 0 of the resources affluent kids have? Draw me a picture and let’s talk about feelings lmao what a joke is that gonna put food in their belly so they can have the calories to burn in order to use their brain to study? What about quiet their 7 other siblings that they share a single bedroom with for hours? Is it gonna force the single mom to magically be at home and at work at the same time to cook food while you study and be there to throw an encouraging word?

Also the “parents don’t need to be a parent and be able to guide their kid at all academically they just need to exist in the next room” is wild. Its one thing if a parent straight up is not equipped but to say kids can just figured it out is…. wow coming from an educator What’s next the teacher doesn’t need to teach cause the kid can just follow the packet and figure it out?

Well then get a tutor right? Oh wait you are poor only affluent kids can afford a tutor for their hours of homework a day were they on average have none of the worries a poor child does. Does this address that poor children are more likely to also suffer abuse and mental illness? Like mentioned what about kids that can’t learn or comprehend the forced standardized way? Just let em fail? These children regularly are not in “special education”(some of those are a joke in their own and full of neglect and abuse) programs cause most aren’t even acknowledged as having disabilities or disorders.

But yes all and all those pesky poor kids just aren’t being worked hard enough lol pretty sure poor children’s existence just in childhood is more work, stress, and responsibility alone than an affluent child’s entire life cycle. Love they never once talked about the quality of education in the classroom being so bad between the poor and affluent it can qualify as segregation, just basically blamed poor people for being lazy, good job capitalism for failing us once again!

why the hell?

you should feel bad for saying this, this article can be helpful for people who has to write a essay about it

This is more of a political rant than it is about homework

I know a teacher who has told his students their homework is to find something they are interested in, pursue it and then come share what they learn. The student responses are quite compelling. One girl taught herself German so she could talk to her grandfather. One boy did a research project on Nelson Mandela because the teacher had mentioned him in class. Another boy, a both on the autism spectrum, fixed his family’s computer. The list goes on. This is fourth grade. I think students are highly motivated to learn, when we step aside and encourage them.

The whole point of homework is to give the students a chance to use the material that they have been presented with in class. If they never have the opportunity to use that information, and discover that it is actually useful, it will be in one ear and out the other. As a science teacher, it is critical that the students are challenged to use the material they have been presented with, which gives them the opportunity to actually think about it rather than regurgitate “facts”. Well designed homework forces the student to think conceptually, as opposed to regurgitation, which is never a pretty sight

Wonderful discussion. and yes, homework helps in learning and building skills in students.

not true it just causes kids to stress

Homework can be both beneficial and unuseful, if you will. There are students who are gifted in all subjects in school and ones with disabilities. Why should the students who are gifted get the lucky break, whereas the people who have disabilities suffer? The people who were born with this “gift” go through school with ease whereas people with disabilities struggle with the work given to them. I speak from experience because I am one of those students: the ones with disabilities. Homework doesn’t benefit “us”, it only tears us down and put us in an abyss of confusion and stress and hopelessness because we can’t learn as fast as others. Or we can’t handle the amount of work given whereas the gifted students go through it with ease. It just brings us down and makes us feel lost; because no mater what, it feels like we are destined to fail. It feels like we weren’t “cut out” for success.

homework does help

here is the thing though, if a child is shoved in the face with a whole ton of homework that isn’t really even considered homework it is assignments, it’s not helpful. the teacher should make homework more of a fun learning experience rather than something that is dreaded

This article was wonderful, I am going to ask my teachers about extra, or at all giving homework.

I agree. Especially when you have homework before an exam. Which is distasteful as you’ll need that time to study. It doesn’t make any sense, nor does us doing homework really matters as It’s just facts thrown at us.

Homework is too severe and is just too much for students, schools need to decrease the amount of homework. When teachers assign homework they forget that the students have other classes that give them the same amount of homework each day. Students need to work on social skills and life skills.

I disagree.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what’s going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Homework is helpful because homework helps us by teaching us how to learn a specific topic.

As a student myself, I can say that I have almost never gotten the full 9 hours of recommended sleep time, because of homework. (Now I’m writing an essay on it in the middle of the night D=)

I am a 10 year old kid doing a report about “Is homework good or bad” for homework before i was going to do homework is bad but the sources from this site changed my mind!

Homeowkr is god for stusenrs

I agree with hunter because homework can be so stressful especially with this whole covid thing no one has time for homework and every one just wants to get back to there normal lives it is especially stressful when you go on a 2 week vaca 3 weeks into the new school year and and then less then a week after you come back from the vaca you are out for over a month because of covid and you have no way to get the assignment done and turned in

As great as homework is said to be in the is article, I feel like the viewpoint of the students was left out. Every where I go on the internet researching about this topic it almost always has interviews from teachers, professors, and the like. However isn’t that a little biased? Of course teachers are going to be for homework, they’re not the ones that have to stay up past midnight completing the homework from not just one class, but all of them. I just feel like this site is one-sided and you should include what the students of today think of spending four hours every night completing 6-8 classes worth of work.

Are we talking about homework or practice? Those are two very different things and can result in different outcomes.

Homework is a graded assignment. I do not know of research showing the benefits of graded assignments going home.

Practice; however, can be extremely beneficial, especially if there is some sort of feedback (not a grade but feedback). That feedback can come from the teacher, another student or even an automated grading program.

As a former band director, I assigned daily practice. I never once thought it would be appropriate for me to require the students to turn in a recording of their practice for me to grade. Instead, I had in-class assignments/assessments that were graded and directly related to the practice assigned.

I would really like to read articles on “homework” that truly distinguish between the two.

oof i feel bad good luck!

thank you guys for the artical because I have to finish an assingment. yes i did cite it but just thanks

thx for the article guys.

Homework is good

I think homework is helpful AND harmful. Sometimes u can’t get sleep bc of homework but it helps u practice for school too so idk.

I agree with this Article. And does anyone know when this was published. I would like to know.

It was published FEb 19, 2019.

Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college.

i think homework can help kids but at the same time not help kids

This article is so out of touch with majority of homes it would be laughable if it wasn’t so incredibly sad.

There is no value to homework all it does is add stress to already stressed homes. Parents or adults magically having the time or energy to shepherd kids through homework is dome sort of 1950’s fantasy.

What lala land do these teachers live in?

Homework gives noting to the kid

Homework is Bad

homework is bad.

why do kids even have homework?

Comments are closed.

Latest from Bostonia

Could boston be the next city to impose congestion pricing, alum has traveled the world to witness total solar eclipses, opening doors: rhonda harrison (eng’98,’04, grs’04), campus reacts and responds to israel-hamas war, reading list: what the pandemic revealed, remembering com’s david anable, cas’ john stone, “intellectual brilliance and brilliant kindness”, one good deed: christine kannler (cas’96, sph’00, camed’00), william fairfield warren society inducts new members, spreading art appreciation, restoring the “black angels” to medical history, in the kitchen with jacques pépin, feedback: readers weigh in on bu’s new president, com’s new expert on misinformation, and what’s really dividing the nation, the gifts of great teaching, sth’s walter fluker honored by roosevelt institute, alum’s debut book is a ramadan story for children, my big idea: covering construction sites with art, former terriers power new professional women’s hockey league, five trailblazing alums to celebrate during women’s history month, alum beata coloyan is boston mayor michelle wu’s “eyes and ears” in boston neighborhoods.

Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

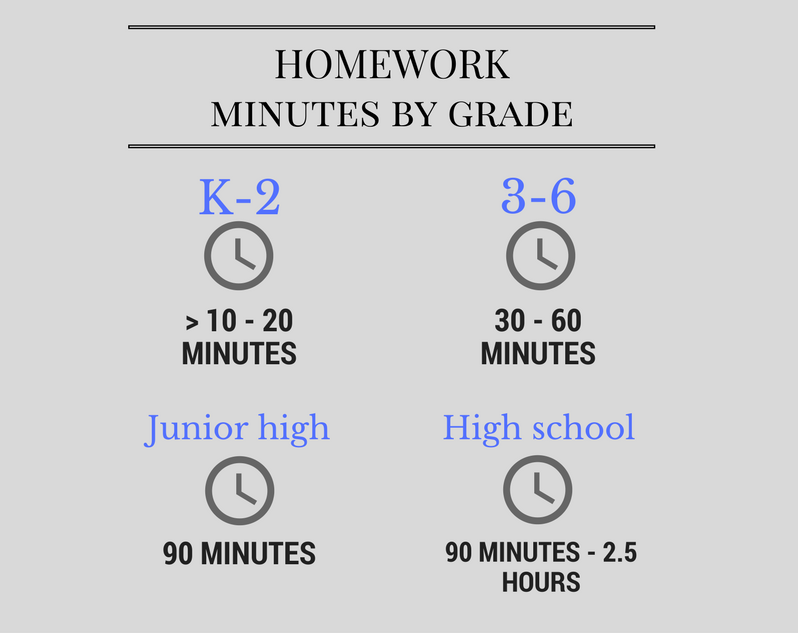

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

You May Also Like

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Credit: August de Richelieu

Does homework still have value? A Johns Hopkins education expert weighs in

Joyce epstein, co-director of the center on school, family, and community partnerships, discusses why homework is essential, how to maximize its benefit to learners, and what the 'no-homework' approach gets wrong.

By Vicky Hallett

The necessity of homework has been a subject of debate since at least as far back as the 1890s, according to Joyce L. Epstein , co-director of the Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships at Johns Hopkins University. "It's always been the case that parents, kids—and sometimes teachers, too—wonder if this is just busy work," Epstein says.

But after decades of researching how to improve schools, the professor in the Johns Hopkins School of Education remains certain that homework is essential—as long as the teachers have done their homework, too. The National Network of Partnership Schools , which she founded in 1995 to advise schools and districts on ways to improve comprehensive programs of family engagement, has developed hundreds of improved homework ideas through its Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program. For an English class, a student might interview a parent on popular hairstyles from their youth and write about the differences between then and now. Or for science class, a family could identify forms of matter over the dinner table, labeling foods as liquids or solids. These innovative and interactive assignments not only reinforce concepts from the classroom but also foster creativity, spark discussions, and boost student motivation.

"We're not trying to eliminate homework procedures, but expand and enrich them," says Epstein, who is packing this research into a forthcoming book on the purposes and designs of homework. In the meantime, the Hub couldn't wait to ask her some questions:

What kind of homework training do teachers typically get?

Future teachers and administrators really have little formal training on how to design homework before they assign it. This means that most just repeat what their teachers did, or they follow textbook suggestions at the end of units. For example, future teachers are well prepared to teach reading and literacy skills at each grade level, and they continue to learn to improve their teaching of reading in ongoing in-service education. By contrast, most receive little or no training on the purposes and designs of homework in reading or other subjects. It is really important for future teachers to receive systematic training to understand that they have the power, opportunity, and obligation to design homework with a purpose.

Why do students need more interactive homework?

If homework assignments are always the same—10 math problems, six sentences with spelling words—homework can get boring and some kids just stop doing their assignments, especially in the middle and high school years. When we've asked teachers what's the best homework you've ever had or designed, invariably we hear examples of talking with a parent or grandparent or peer to share ideas. To be clear, parents should never be asked to "teach" seventh grade science or any other subject. Rather, teachers set up the homework assignments so that the student is in charge. It's always the student's homework. But a good activity can engage parents in a fun, collaborative way. Our data show that with "good" assignments, more kids finish their work, more kids interact with a family partner, and more parents say, "I learned what's happening in the curriculum." It all works around what the youngsters are learning.

Is family engagement really that important?

At Hopkins, I am part of the Center for Social Organization of Schools , a research center that studies how to improve many aspects of education to help all students do their best in school. One thing my colleagues and I realized was that we needed to look deeply into family and community engagement. There were so few references to this topic when we started that we had to build the field of study. When children go to school, their families "attend" with them whether a teacher can "see" the parents or not. So, family engagement is ever-present in the life of a school.

My daughter's elementary school doesn't assign homework until third grade. What's your take on "no homework" policies?

There are some parents, writers, and commentators who have argued against homework, especially for very young children. They suggest that children should have time to play after school. This, of course is true, but many kindergarten kids are excited to have homework like their older siblings. If they give homework, most teachers of young children make assignments very short—often following an informal rule of 10 minutes per grade level. "No homework" does not guarantee that all students will spend their free time in productive and imaginative play.

Some researchers and critics have consistently misinterpreted research findings. They have argued that homework should be assigned only at the high school level where data point to a strong connection of doing assignments with higher student achievement . However, as we discussed, some students stop doing homework. This leads, statistically, to results showing that doing homework or spending more minutes on homework is linked to higher student achievement. If slow or struggling students are not doing their assignments, they contribute to—or cause—this "result."

Teachers need to design homework that even struggling students want to do because it is interesting. Just about all students at any age level react positively to good assignments and will tell you so.

Did COVID change how schools and parents view homework?

Within 24 hours of the day school doors closed in March 2020, just about every school and district in the country figured out that teachers had to talk to and work with students' parents. This was not the same as homeschooling—teachers were still working hard to provide daily lessons. But if a child was learning at home in the living room, parents were more aware of what they were doing in school. One of the silver linings of COVID was that teachers reported that they gained a better understanding of their students' families. We collected wonderfully creative examples of activities from members of the National Network of Partnership Schools. I'm thinking of one art activity where every child talked with a parent about something that made their family unique. Then they drew their finding on a snowflake and returned it to share in class. In math, students talked with a parent about something the family liked so much that they could represent it 100 times. Conversations about schoolwork at home was the point.

How did you create so many homework activities via the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program?

We had several projects with educators to help them design interactive assignments, not just "do the next three examples on page 38." Teachers worked in teams to create TIPS activities, and then we turned their work into a standard TIPS format in math, reading/language arts, and science for grades K-8. Any teacher can use or adapt our prototypes to match their curricula.

Overall, we know that if future teachers and practicing educators were prepared to design homework assignments to meet specific purposes—including but not limited to interactive activities—more students would benefit from the important experience of doing their homework. And more parents would, indeed, be partners in education.

Posted in Voices+Opinion

You might also like

News network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement?

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

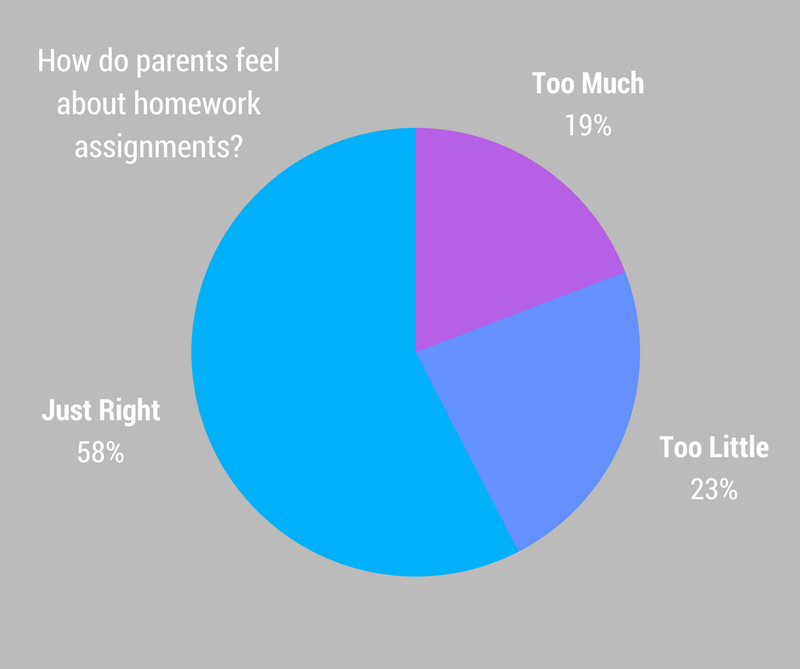

Educators should be thrilled by these numbers. Pleasing a majority of parents regarding homework and having equal numbers of dissenters shouting "too much!" and "too little!" is about as good as they can hope for.

But opinions cannot tell us whether homework works; only research can, which is why my colleagues and I have conducted a combined analysis of dozens of homework studies to examine whether homework is beneficial and what amount of homework is appropriate for our children.

The homework question is best answered by comparing students who are assigned homework with students assigned no homework but who are similar in other ways. The results of such studies suggest that homework can improve students' scores on the class tests that come at the end of a topic. Students assigned homework in 2nd grade did better on math, 3rd and 4th graders did better on English skills and vocabulary, 5th graders on social studies, 9th through 12th graders on American history, and 12th graders on Shakespeare.

Less authoritative are 12 studies that link the amount of homework to achievement, but control for lots of other factors that might influence this connection. These types of studies, often based on national samples of students, also find a positive link between time on homework and achievement.

Yet other studies simply correlate homework and achievement with no attempt to control for student differences. In 35 such studies, about 77 percent find the link between homework and achievement is positive. Most interesting, though, is these results suggest little or no relationship between homework and achievement for elementary school students.

Why might that be? Younger children have less developed study habits and are less able to tune out distractions at home. Studies also suggest that young students who are struggling in school take more time to complete homework assignments simply because these assignments are more difficult for them.

These recommendations are consistent with the conclusions reached by our analysis. Practice assignments do improve scores on class tests at all grade levels. A little amount of homework may help elementary school students build study habits. Homework for junior high students appears to reach the point of diminishing returns after about 90 minutes a night. For high school students, the positive line continues to climb until between 90 minutes and 2½ hours of homework a night, after which returns diminish.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what's going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Opponents of homework counter that it can also have negative effects. They argue it can lead to boredom with schoolwork, since all activities remain interesting only for so long. Homework can deny students access to leisure activities that also teach important life skills. Parents can get too involved in homework -- pressuring their child and confusing him by using different instructional techniques than the teacher.

My feeling is that homework policies should prescribe amounts of homework consistent with the research evidence, but which also give individual schools and teachers some flexibility to take into account the unique needs and circumstances of their students and families. In general, teachers should avoid either extreme.

Link to this page

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

- Our Mission

Research Trends: Why Homework Should Be Balanced

Research suggests that while homework can be an effective learning tool, assigning too much can lower student performance and interfere with other important activities.

Homework: effective learning tool or waste of time?

Since the average high school student spends almost seven hours each week doing homework, it’s surprising that there’s no clear answer. Homework is generally recognized as an effective way to reinforce what students learn in class, but claims that it may cause more harm than good, especially for younger students, are common.

Here’s what the research says:

- In general, homework has substantial benefits at the high school level, with decreased benefits for middle school students and few benefits for elementary students (Cooper, 1989; Cooper et al., 2006).

- While assigning homework may have academic benefits, it can also cut into important personal and family time (Cooper et al., 2006).

- Assigning too much homework can result in poor performance (Fernández-Alonso et al., 2015).

- A student’s ability to complete homework may depend on factors that are outside their control (Cooper et al., 2006; OECD, 2014; Eren & Henderson, 2011).

- The goal shouldn’t be to eliminate homework, but to make it authentic, meaningful, and engaging (Darling-Hammond & Ifill-Lynch, 2006).

Why Homework Should Be Balanced

Homework can boost learning, but doing too much can be detrimental. The National PTA and National Education Association support the “10-minute homework rule,” which recommends 10 minutes of homework per grade level, per night (10 minutes for first grade, 20 minutes for second grade, and so on, up to two hours for 12th grade) (Cooper, 2010). A recent study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90–100 minutes of homework per day, their math and science scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015). Giving students too much homework can lead to fatigue, stress, and a loss of interest in academics—something that we all want to avoid.

Homework Pros and Cons

Homework has many benefits, ranging from higher academic performance to improved study skills and stronger school-parent connections. However, it can also result in a loss of interest in academics, fatigue, and a loss of important personal and family time.

Grade Level Makes a Difference

Although the debate about homework generally falls in the “it works” vs. “it doesn’t work” camps, research shows that grade level makes a difference. High school students generally get the biggest benefits from homework, with middle school students getting about half the benefits, and elementary school students getting few benefits (Cooper et al., 2006). Since young students are still developing study habits like concentration and self-regulation, assigning a lot of homework isn’t all that helpful.

Parents Should Be Supportive, Not Intrusive

Well-designed homework not only strengthens student learning, it also provides ways to create connections between a student’s family and school. Homework offers parents insight into what their children are learning, provides opportunities to talk with children about their learning, and helps create conversations with school communities about ways to support student learning (Walker et al., 2004).

However, parent involvement can also hurt student learning. Patall, Cooper, and Robinson (2008) found that students did worse when their parents were perceived as intrusive or controlling. Motivation plays a key role in learning, and parents can cause unintentional harm by not giving their children enough space and autonomy to do their homework.

Homework Across the Globe

OECD , the developers of the international PISA test, published a 2014 report looking at homework around the world. They found that 15-year-olds worldwide spend an average of five hours per week doing homework (the U.S. average is about six hours). Surprisingly, countries like Finland and Singapore spend less time on homework (two to three hours per week) but still have high PISA rankings. These countries, the report explains, have support systems in place that allow students to rely less on homework to succeed. If a country like the U.S. were to decrease the amount of homework assigned to high school students, test scores would likely decrease unless additional supports were added.

Homework Is About Quality, Not Quantity

Whether you’re pro- or anti-homework, keep in mind that research gives a big-picture idea of what works and what doesn’t, and a capable teacher can make almost anything work. The question isn’t homework vs. no homework ; instead, we should be asking ourselves, “How can we transform homework so that it’s engaging and relevant and supports learning?”

Cooper, H. (1989). Synthesis of research on homework . Educational leadership, 47 (3), 85-91.

Cooper, H. (2010). Homework’s Diminishing Returns . The New York Times .

Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003 . Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1-62.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Ifill-Lynch, O. (2006). If They'd Only Do Their Work! Educational Leadership, 63 (5), 8-13.

Eren, O., & Henderson, D. J. (2011). Are we wasting our children's time by giving them more homework? Economics of Education Review, 30 (5), 950-961.

Fernández-Alonso, R., Suárez-Álvarez, J., & Muñiz, J. (2015, March 16). Adolescents’ Homework Performance in Mathematics and Science: Personal Factors and Teaching Practices . Journal of Educational Psychology. Advance online publication.

OECD (2014). Does Homework Perpetuate Inequities in Education? PISA in Focus , No. 46, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). Parent involvement in homework: A research synthesis . Review of Educational Research, 78 (4), 1039-1101.

Van Voorhis, F. L. (2003). Interactive homework in middle school: Effects on family involvement and science achievement . The Journal of Educational Research, 96 (6), 323-338.

Walker, J. M., Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Whetsel, D. R., & Green, C. L. (2004). Parental involvement in homework: A review of current research and its implications for teachers, after school program staff, and parent leaders . Cambridge, MA: Harvard Family Research Project.

- The Journal

- Vol. 19, No. 1

The Case for (Quality) Homework

Janine Bempechat

Any parent who has battled with a child over homework night after night has to wonder: Do those math worksheets and book reports really make a difference to a student’s long-term success? Or is homework just a headache—another distraction from family time and downtime, already diminished by the likes of music and dance lessons, sports practices, and part-time jobs?

Allison, a mother of two middle-school girls from an affluent Boston suburb, describes a frenetic afterschool scenario: “My girls do gymnastics a few days a week, so homework happens for my 6th grader after gymnastics, at 6:30 p.m. She doesn’t get to bed until 9. My 8th grader does her homework immediately after school, up until gymnastics. She eats dinner at 9:15 and then goes to bed, unless there is more homework to do, in which case she’ll get to bed around 10.” The girls miss out on sleep, and weeknight family dinners are tough to swing.

Parental concerns about their children’s homework loads are nothing new. Debates over the merits of homework—tasks that teachers ask students to complete during non-instructional time—have ebbed and flowed since the late 19th century, and today its value is again being scrutinized and weighed against possible negative impacts on family life and children’s well-being.

Are American students overburdened with homework? In some middle-class and affluent communities, where pressure on students to achieve can be fierce, yes. But in families of limited means, it’s often another story. Many low-income parents value homework as an important connection to the school and the curriculum—even as their children report receiving little homework. Overall, high-school students relate that they spend less than one hour per day on homework, on average, and only 42 percent say they do it five days per week. In one recent survey by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a minimal 13 percent of 17-year-olds said they had devoted more than two hours to homework the previous evening (see Figure 1).

Recent years have seen an increase in the amount of homework assigned to students in grades K–2, and critics point to research findings that, at the elementary-school level, homework does not appear to enhance children’s learning. Why, then, should we burden young children and their families with homework if there is no academic benefit to doing it? Indeed, perhaps it would be best, as some propose, to eliminate homework altogether, particularly in these early grades.

On the contrary, developmentally appropriate homework plays a critical role in the formation of positive learning beliefs and behaviors, including a belief in one’s academic ability, a deliberative and effortful approach to mastery, and higher expectations and aspirations for one’s future. It can prepare children to confront ever-more-complex tasks, develop resilience in the face of difficulty, and learn to embrace rather than shy away from challenge. In short, homework is a key vehicle through which we can help shape children into mature learners.

The Homework-Achievement Connection

A narrow focus on whether or not homework boosts grades and test scores in the short run thus ignores a broader purpose in education, the development of lifelong, confident learners. Still, the question looms: does homework enhance academic success? As the educational psychologist Lyn Corno wrote more than two decades ago, “homework is a complicated thing.” Most research on the homework-achievement connection is correlational, which precludes a definitive judgment on its academic benefits. Researchers rely on correlational research in this area of study given the difficulties of randomly assigning students to homework/no-homework conditions. While correlation does not imply causality, extensive research has established that at the middle- and high-school levels, homework completion is strongly and positively associated with high achievement. Very few studies have reported a negative correlation.

As noted above, findings on the homework-achievement connection at the elementary level are mixed. A small number of experimental studies have demonstrated that elementary-school students who receive homework achieve at higher levels than those who do not. These findings suggest a causal relationship, but they are limited in scope. Within the body of correlational research, some studies report a positive homework-achievement connection, some a negative relationship, and yet others show no relationship at all. Why the mixed findings? Researchers point to a number of possible factors, such as developmental issues related to how young children learn, different goals that teachers have for younger as compared to older students, and how researchers define homework.

Certainly, young children are still developing skills that enable them to focus on the material at hand and study efficiently. Teachers’ goals for their students are also quite different in elementary school as compared to secondary school. While teachers at both levels note the value of homework for reinforcing classroom content, those in the earlier grades are more likely to assign homework mainly to foster skills such as responsibility, perseverance, and the ability to manage distractions.

Most research examines homework generally. Might a focus on homework in a specific subject shed more light on the homework-achievement connection? A recent meta-analysis did just this by examining the relationship between math/science homework and achievement. Contrary to previous findings, researchers reported a stronger relationship between homework and achievement in the elementary grades than in middle school. As the study authors note, one explanation for this finding could be that in elementary school, teachers tend to assign more homework in math than in other subjects, while at the same time assigning shorter math tasks more frequently. In addition, the authors point out that parents tend to be more involved in younger children’s math homework and more skilled in elementary-level than middle-school math.

In sum, the relationship between homework and academic achievement in the elementary-school years is not yet established, but eliminating homework at this level would do children and their families a huge disservice: we know that children’s learning beliefs have a powerful impact on their academic outcomes, and that through homework, parents and teachers can have a profound influence on the development of positive beliefs.

How Much Is Appropriate?

Harris M. Cooper of Duke University, the leading researcher on homework, has examined decades of study on what we know about the relationship between homework and scholastic achievement. He has proposed the “10-minute rule,” suggesting that daily homework be limited to 10 minutes per grade level. Thus, a 1st grader would do 10 minutes each day and a 4th grader, 40 minutes. The National Parent Teacher Association and the National Education Association both endorse this guideline, but it is not clear whether the recommended allotments include time for reading, which most teachers want children to do daily.

For middle-school students, Cooper and colleagues report that 90 minutes per day of homework is optimal for enhancing academic achievement, and for high schoolers, the ideal range is 90 minutes to two and a half hours per day. Beyond this threshold, more homework does not contribute to learning. For students enrolled in demanding Advanced Placement or honors courses, however, homework is likely to require significantly more time, leading to concerns over students’ health and well-being.

Notwithstanding media reports of parents revolting against the practice of homework, the vast majority of parents say they are highly satisfied with their children’s homework loads. The National Household Education Surveys Program recently found that between 70 and 83 percent of parents believed that the amount of homework their children had was “about right,” a result that held true regardless of social class, race/ethnicity, community size, level of education, and whether English was spoken at home.

Learning Beliefs Are Consequential

As noted above, developmentally appropriate homework can help children cultivate positive beliefs about learning. Decades of research have established that these beliefs predict the types of tasks students choose to pursue, their persistence in the face of challenge, and their academic achievement. Broadly, learning beliefs fall under the banner of achievement motivation, which is a constellation of cognitive, behavioral, and affective factors, including: the way a person perceives his or her abilities, goal-setting skills, expectation of success, the value the individual places on learning, and self-regulating behavior such as time-management skills. Positive or adaptive beliefs about learning serve as emotional and psychological protective factors for children, especially when they encounter difficulties or failure.

Motivation researcher Carol Dweck of Stanford University posits that children with a “growth mindset”—those who believe that ability is malleable—approach learning very differently than those with a “fixed mindset”—kids who believe ability cannot change. Those with a growth mindset view effort as the key to mastery. They see mistakes as helpful, persist even in the face of failure, prefer challenging over easy tasks, and do better in school than their peers who have a fixed mindset. In contrast, children with a fixed mindset view effort and mistakes as implicit condemnations of their abilities. Such children succumb easily to learned helplessness in the face of difficulty, and they gravitate toward tasks they know they can handle rather than more challenging ones.

Of course, learning beliefs do not develop in a vacuum. Studies have demonstrated that parents and teachers play a significant role in the development of positive beliefs and behaviors, and that homework is a key tool they can use to foster motivation and academic achievement.

Parents’ Beliefs and Actions Matter

It is well established that parental involvement in their children’s education promotes achievement motivation and success in school. Parents are their children’s first teachers, and their achievement-related beliefs have a profound influence on children’s developing perceptions of their own abilities, as well as their views on the value of learning and education.

Parents affect their children’s learning through the messages they send about education, whether by expressing interest in school activities and experiences, attending school events, helping with homework when they can, or exposing children to intellectually enriching experiences. Most parents view such engagement as part and parcel of their role. They also believe that doing homework fosters responsibility and organizational skills, and that doing well on homework tasks contributes to learning, even if children experience frustration from time to time.

Many parents provide support by establishing homework routines, eliminating distractions, communicating expectations, helping children manage their time, providing reassuring messages, and encouraging kids to be aware of the conditions under which they do their best work. These supports help foster the development of self-regulation, which is critical to school success.

Self-regulation involves a number of skills, such as the ability to monitor one’s performance and adjust strategies as a result of feedback; to evaluate one’s interests and realistically perceive one’s aptitude; and to work on a task autonomously. It also means learning how to structure one’s environment so that it’s conducive to learning, by, for example, minimizing distractions. As children move into higher grades, these skills and strategies help them organize, plan, and learn independently. This is precisely where parents make a demonstrable difference in students’ attitudes and approaches to homework.

Especially in the early grades, homework gives parents the opportunity to cultivate beliefs and behaviors that foster efficient study skills and academic resilience. Indeed, across age groups, there is a strong and positive relationship between homework completion and a variety of self-regulatory processes. However, the quality of parental help matters. Sometimes, well-intentioned parents can unwittingly undermine the development of children’s positive learning beliefs and their achievement. Parents who maintain a positive outlook on homework and allow their children room to learn and struggle on their own, stepping in judiciously with informational feedback and hints, do their children a much better service than those who seek to control the learning process.

A recent study of 5th and 6th graders’ perceptions of their parents’ involvement with homework distinguished between supportive and intrusive help. The former included the belief that parents encouraged the children to try to find the right answer on their own before providing them with assistance, and when the child struggled, attempted to understand the source of the confusion. In contrast, the latter included the perception that parents provided unsolicited help, interfered when the children did their homework, and told them how to complete their assignments. Supportive help predicted higher achievement, while intrusive help was associated with lower achievement.

Parents’ attitudes and emotions during homework time can support the development of positive attitudes and approaches in their children, which in turn are predictive of higher achievement. Children are more likely to focus on self-improvement during homework time and do better in school when their parents are oriented toward mastery. In contrast, if parents focus on how well children are doing relative to peers, kids tend to adopt learning goals that allow them to avoid challenge.

Homework and Social Class

Social class is another important element in the homework dynamic. What is the homework experience like for families with limited time and resources? And what of affluent families, where resources are plenty but the pressures to succeed are great?

Etta Kralovec and John Buell, authors of The End of Homework, maintain that homework “punishes the poor,” because lower-income parents may not be as well educated as their affluent counterparts and thus not as well equipped to help with homework. Poorer families also have fewer financial resources to devote to home computers, tutoring, and academic enrichment. The stresses of poverty—and work schedules—may impinge, and immigrant parents may face language barriers and an unfamiliarity with the school system and teachers’ expectations.

Yet research shows that low-income parents who are unable to assist with homework are far from passive in their children’s learning, and they do help foster scholastic performance. In fact, parental help with homework is not a necessary component for school success.

Brown University’s Jin Li queried low-income Chinese American 9th graders’ perceptions of their parents’ engagement with their education. Students said their immigrant parents rarely engaged in activities that are known to foster academic achievement, such as monitoring homework, checking it for accuracy, or attending school meetings or events. Instead, parents of higher achievers built three social networks to support their children’s learning. They designated “anchor” helpers both inside and outside the family who provided assistance; identified peer models for their children to emulate; and enlisted the assistance of extended kin to guide their children’s educational socialization. In a related vein, a recent analysis of survey data showed that Asian and Latino 5th graders, relative to native-born peers, were more likely to turn to siblings than parents for homework help.

Further, research demonstrates that low-income parents, recognizing that they lack the time to be in the classroom or participate in school governance, view homework as a critical connection to their children’s experiences in school. One study found that mothers enjoyed the routine and predictability of homework and used it as a way to demonstrate to children how to plan their time. Mothers organized homework as a family activity, with siblings doing homework together and older children reading to younger ones. In this way, homework was perceived as a collective practice wherein siblings could model effective habits and learn from one another.

In another recent study, researchers examined mathematics achievement in low-income 8th-grade Asian and Latino students. Help with homework was an advantage their mothers could not provide. They could, however, furnish structure (for example, by setting aside quiet time for homework completion), and it was this structure that most predicted high achievement. As the authors note, “It is . . . important to help [low-income] parents realize that they can still help their children get good grades in mathematics and succeed in school even if they do not know how to provide direct assistance with their child’s mathematics homework.”

The homework narrative at the other end of the socioeconomic continuum is altogether different. Media reports abound with examples of students, mostly in high school, carrying three or more hours of homework per night, a burden that can impair learning, motivation, and well-being. In affluent communities, students often experience intense pressure to cultivate a high-achieving profile that will be attractive to elite colleges. Heavy homework loads have been linked to unhealthy symptoms such as heightened stress, anxiety, physical complaints, and sleep disturbances. Like Allison’s 6th grader mentioned earlier, many students can only tackle their homework after they do extracurricular activities, which are also seen as essential for the college résumé. Not surprisingly, many students in these communities are not deeply engaged in learning; rather, they speak of “doing school,” as Stanford researcher Denise Pope has described, going through the motions necessary to excel, and undermining their physical and mental health in the process.

Fortunately, some national intervention initiatives, such as Challenge Success (co-founded by Pope), are heightening awareness of these problems. Interventions aimed at restoring balance in students’ lives (in part, by reducing homework demands) have resulted in students reporting an increased sense of well-being, decreased stress and anxiety, and perceptions of greater support from teachers, with no decrease in achievement outcomes.

What is good for this small segment of students, however, is not necessarily good for the majority. As Jessica Lahey wrote in Motherlode, a New York Times parenting blog, “homework is a red herring” in the national conversation on education. “Some otherwise privileged children may have too much, but the real issue lies in places where there is too little. . . . We shouldn’t forget that.”

My colleagues and I analyzed interviews conducted with lower-income 9th graders (African American, Mexican American, and European American) from two Northern California high schools that at the time were among the lowest-achieving schools in the state. We found that these students consistently described receiving minimal homework—perhaps one or two worksheets or textbook pages, the occasional project, and 30 minutes of reading per night. Math was the only class in which they reported having homework each night. These students noted few consequences for not completing their homework.

Indeed, greatly reducing or eliminating homework would likely increase, not diminish, the achievement gap. As Harris M. Cooper has commented, those choosing to opt their children out of homework are operating from a place of advantage. Children in higher-income families benefit from many privileges, including exposure to a larger range of language at home that may align with the language of school, access to learning and cultural experiences, and many other forms of enrichment, such as tutoring and academic summer camps, all of which may be cost-prohibitive for lower-income families. But for the 21 percent of the school-age population who live in poverty—nearly 11 million students ages 5–17—homework is one tool that can help narrow the achievement gap.