latest in US News

Homeless man accused of killing 3 relatives in Pa. standoff will...

Florida man shoots roommate in front of kids in bizarre...

NYC bartender fatally stabbed by enraged boyfriend told coworkers...

Texas asks court to decide if the state’s migrant arrest law...

NY Assembly Republicans demand Dems get tough on crime, bash Carl...

New York’s antiquated adultery ban one step closer to being...

Justice Department sues Utah after transgender inmate 'removed...

Nicholas Roske negotiating plea deal over plot to assassinate...

Who is vinay reddy, joe biden’s speechwriter.

- View Author Archive

- Email the Author

- Follow on Twitter

- Get author RSS feed

Contact The Author

Thanks for contacting us. We've received your submission.

Thanks for contacting us. We've received your submission.

Joe Biden’s speechwriter is a first-generation Indian American who lives in New York and previously worked for the new commander-in-chief, reports said Wednesday.

Vinay Reddy, who penned Biden’s inaugural speech for Wednesday’s ceremony , is currently the speechwriter on the Biden-Harris transition team and also worked as a senior adviser and speechwriter for the team’s campaign, the Hindustan Times reported .

Previously, Reddy did stints writing speeches for the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Health and Human Services and the Obama-Biden re-election campaign.

He also worked for the National Basketball Association as the vice president of strategic communications after serving as Biden’s chief speechwriter during his second term as vice president in the Obama-Biden White House, the outlet reported.

Reddy was born and raised in Ohio, but his family comes from the Telangana Pothireddypeta village in Karimnagar, India, the outlet said. Reddy’s father, Narayana Reddy, started his life in the US in 1970 following his completion of medical school in Karimnagar.

The speechwriter’s family is well connected in their hometown: Reddy’s grandfather Thirupathi Reddy served as the village head and the family still owns acres of land in the area, visiting regularly.

Reddy currently lives in New York with his wife and two daughters.

Share this article:

When Did U.S. Presidents Start Using Speechwriters?

By quora .com | jan 23, 2017.

When did U.S. presidents start outsourcing the writing of their speeches? Ross Cohen :

According to Robert Schlesinger, author of Presidents and Their Speechwriters , “Judson Welliver, 'literary clerk' during the Harding administration, from 1921 to 1923, is generally considered the first presidential speechwriter in the modern sense—someone whose job description includes helping to compose speeches.”

And then FDR had a number of people helping him.

That said, some of it started right from the beginning, to some extent. Not outsourcing, per se—at least not consistently—but certainly collaboration.

The first draft of George Washington’s famous farewell address was prepared with the assistance of James Madison, five years before he ultimately delivered it. Years later, Alexander Hamilton put in a lot of work helping Washington revise it before it reached its final form.

James Monroe delivered his famous doctrine in a State of the Union Address, but it was primarily written by his Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams.

“When James K. Polk asked Congress for a declaration of war against Mexico in 1846, his words were written by Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft, the most distinguished American historian of the time," according to Profiles of U.S. Presidents. "Years later Bancroft was again the presidential amanuensis, this time of Andrew Johnson.”

According to the same source, Woodrow Wilson was the last president to write his own speeches.

After Wilson came Harding, who was the first president with a dedicated speechwriter (though I’m not sure if his immediate successors, Coolidge and Hoover, had one as well). Once they were through it becomes a little clearer, as FDR is known to have used a number of ghost writers for his speeches.

This post originally appeared on Quora. Click here to view .

How Speechwriters Delve Into a President's Mind: Lots of Listening, Studying and Becoming a Mirror

There are few times in a American presidency that the art of speechwriting is more on display than during a State of the Union

How Speechwriters Delve Into a President's Mind: Lots of Listening, Studying and Becoming a Mirror

Patrick Semansky

FILE - President Joe Biden delivers the State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress at the U.S. Capitol, Feb. 7, 2023, in Washington. It’s an annual process that former presidential speechwriters say take months. Speechwriters have the uneviable task of taking dozens of ideas and stitching into a cohesive narrative of a president’s vision for the year. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

WASHINGTON (AP) — Speechwriting, in one sense, is essentially being someone else’s mirror.

“You can try to find the right words,” said Dan Cluchey, a former speechwriter for President Joe Biden . “But ultimately, your job is to ensure that when the speech is done, that it has a reflection of the speaker.”

That concept is infinitely magnified in the role of the presidential speechwriter. Over the course of U.S. history, those aides have absorbed the personalities, the quirks, the speech cadences of the most powerful leader on the globe, capturing his thoughts for all manner of public remarks, from the mundane to the historic and most consequential.

There are few times in a presidency that the art — and the rigorous, often painful process — of speechwriting is more on display than during a State of the Union , when the vast array of a president’s policy aspirations and political messages come together in one, hour-plus carefully choreographed address at the Capitol. Biden will deliver the annual address on Thursday .

It’s a process that former White House speechwriters say take months, with untold lobbying and input from various federal agencies and others outside the president’s inner circle who are all working to ensure their favored proposals merit a mention. Speechwriters have the unenviable task of taking dozens of ideas and stitching them into a cohesive narrative of a president’s vision for the year.

It’s less elegant prose, more laundry list of policy ideas.

Photos You Should See

Amid all those formalities and constraints of a State of the Union address, there is also how a president executes the speech.

Biden’s biggest political liability remains his age (81) and voters’ questions about whether he is still up to the job (his doctor this past week declared him fit to serve ). His every word is watched by Republican operatives eager to capture any misspeak to plant doubt about Biden’s fitness among the public.

“This year, of course, is an election year. It also comes as there’s much more chatter about his age,” said Michael Waldman, who served as a speechwriter for President Bill Clinton. “People are really going to be scrutinizing him for how he delivers the speech, as much as what he says.”

Biden will remain at Camp David through Tuesday and is expected to spend much of that time preparing for the State of the Union. Bruce Reed, the White House deputy chief of staff, accompanied Biden to the presidential retreat outside Washington on Friday evening.

The White House has said lowering costs, shoring up democracy and protecting women’s reproductive care will be among the topics that Biden will address on Thursday night.

Biden likely won’t top the list of the most talented presidential orators. He has thrived the most during small chance encounters with Americans, where interactions can be more off the cuff and intimate.

The plain-spoken Biden is known to hate Washington jargon and the alphabet soup of government acronyms, and he has challenged aides, when writing his remarks, to cut through the clutter and to get to the point with speed. Cluchey, who worked for Biden from 2018 to 2022, said the president was very engaged in the speech drafting process, all the way down to individual lines and words.

Biden can also come across as stiff at times when standing and reading from a teleprompter, but immediately loosens up and appears more comfortable when he switches to a hand-held microphone mid-remark. Biden has also learned to navigate a childhood stutter that he says helped him develop empathy for others facing similar challenges.

To become engrossed in another person’s voice, past presidential speechwriters list things that are critical. One is just doing a lot of listening to the principal, to get a sense of his rhythms and how he uses language.

Lots of direct conversation with the president is key, to try and get inside the commander in chief's thinking and how that leader frames arguments and make their case.

“This is not an act of impression, where you’re simply just trying to get the accent down,” said Jeff Shesol, another former Clinton speechwriter. “What you really are learning to do and need to learn to do -– this is true of speechwriters in any role, but particularly for a president –- is to understand not just how he sounds, but how he thinks.”

Shesol added: “You’re absorbing not just the rhythms and cadences of speech, but you’re absorbing a worldview.”

Then there is always the matter of the speech-giver going rogue.

Biden is often candid, and White House aides are sometimes left to clean up and clarify what he said in unvarnished moments. But other times when he deviates from the script, it ends up being an improvement on what his aides had scripted.

Take last year’s State of the Union . Biden had launched into an attack prepared in advance against some Republicans who were insisting on requiring renewal votes on popular programs such as Medicare and Social Security, which would effectively threaten their fate every five years.

That prompted heckling from Republicans and shouts of “Liar!” from the audience.

Biden immediately pivoted, egging on the Republicans to contact his office for a copy of the proposal and joking that he was enjoying their “conversion.”

“Folks, as we all apparently agree, Social Security and Medicare is off the — off the books now, right? They’re not to be touched?” Biden continued. The crowd of lawmakers applauded. “All right. All right. We got unanimity!"

Speechwriters do try and prepare for such moments, particularly if a president is known to speak extemporaneously.

Shesol recalled that Clinton's speechwriters would draft remarks that were relatively spare, to account for him veering off on his own. The writers would write a clear structure into the speech that would allow Clinton to easily return to his prepared remarks once his riff was over.

“Clinton used to liken it to playing a jazz solo and then he’s going back to the score,” Waldman added.

Cluchey, when asked for his reaction when his former boss would go off-script, described it as a “ballet with several movements of, you know, panic, to ‘Wait a minute, this is actually very good,’ and then ‘Oh man, he really nailed it.’”

Biden is “at his best when he’s most authentically, most loosely, just speaking the plain truth,” Cluchey said. “The speechwriting process even at its best has strictures around it.”

Copyright 2024 The Associated Press . All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Join the Conversation

Tags: Associated Press , politics

America 2024

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

Feb. 1, 2017, at 1:24 p.m.

Photos: Obama Behind the Scenes

April 8, 2022

Photos: Who Supports Joe Biden?

March 11, 2020

Powell: Rate Cuts Still Likely in 2024

Tim Smart April 3, 2024

EXPLAINER: Rare Human Case of Bird Flu

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder April 3, 2024

Key Takeaways From 4 Primaries

Susan Milligan April 3, 2024

ADP: Employers Keep on Hiring

The Worst Presidential Scandals

Seth Cline April 2, 2024

Trump Hits the Trail Amid Legal Dramas

Lauren Camera April 2, 2024

Listen Live

Think with Krys Boyd

Think is a national call-in radio program, hosted by acclaimed journalist Krys Boyd and produced by KERA — North Texas’ PBS and NPR member station. Each week, listeners across the country tune in to the program to hear thought-provoking, in-depth conversations with newsmakers from across the globe.

- Politics & Policy

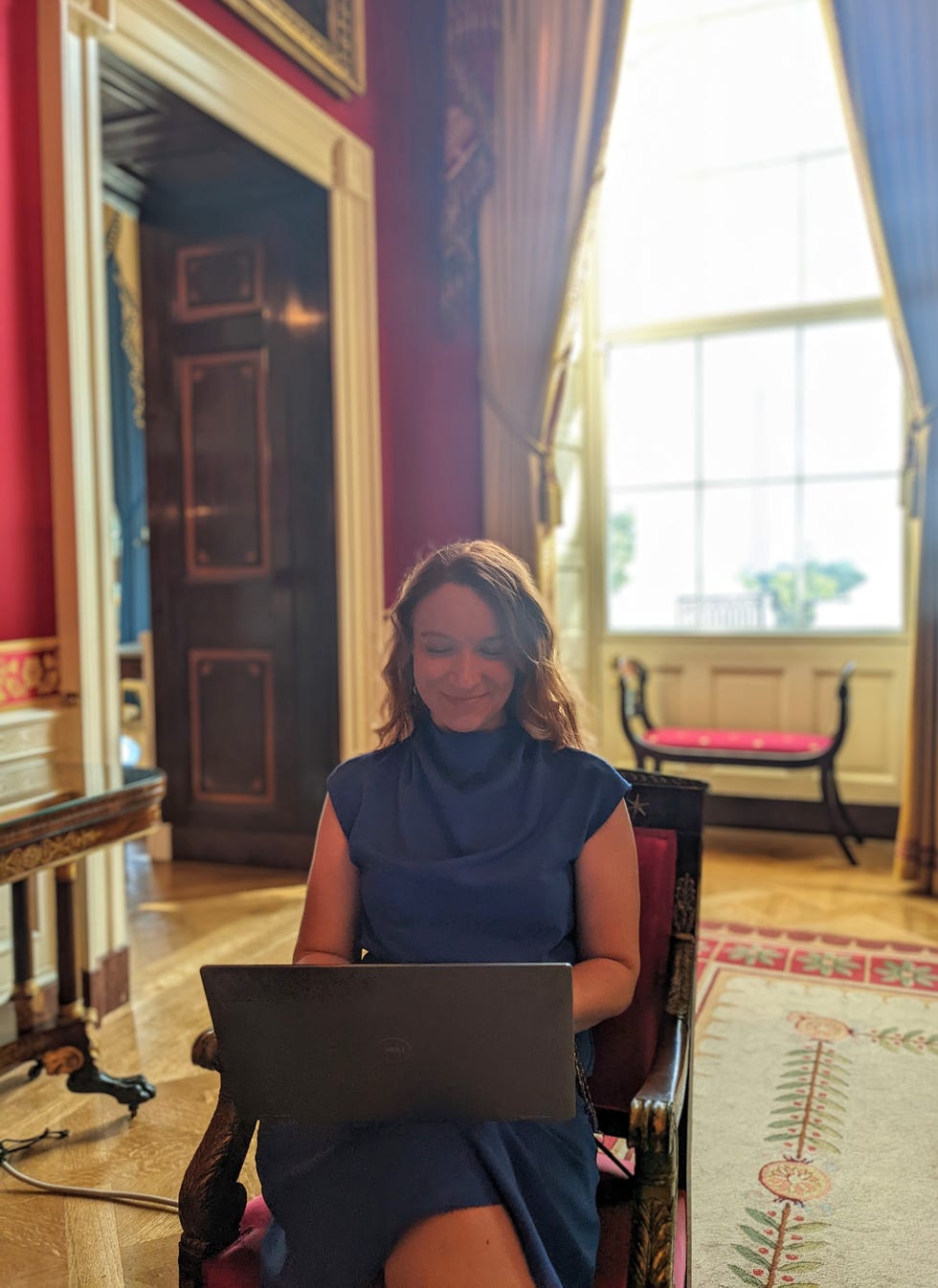

‘Incredible ability to translate your thoughts’: Gov. Carney’s wordsmith is President Biden’s newest speechwriter

The 36-year-old wilmington native has been gov. john carney’s chief of staff since 2019. now she’s moving to the white house..

- Cris Barrish

Wilmingtonian Sheila Grant is stepping down as Gov. Carney's chief of staff to become senior speechwriter for President Biden. (State of Delaware)

Related Content

‘The danger it poses to our democracy’: Digital literacy standards to help Delaware students discern truth from fiction

Lead sponsor Sen. Sarah McBride says the measure was spurred by the election lies that led to the Capital insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021.

2 years ago

Rising up the political ladder ‘to bigger and better things’

$50M in grants available to help Delaware homeowners impacted by pandemic

Eligible applicants can get up to $40,000 to pay their delinquent mortgage, property taxes, water and sewer bills, and condominium fees.

Grant had to write “literally hundreds of responses to people from Delaware and across the country,’’ Carper said. Her talent as a writer was evident at the outset but “by the time she left us and went on to bigger and better things, it was just great,’’ Carper said.

In 2011, Grant joined then-U.S. Rep. Carney’s office in 2011, serving as director of communications and then legislative affairs — all while helping craft his speeches. Her leadership ability shone through, so Carney eventually made her chief of staff.

When Carney became governor in 2017, Grant joined the new administration as deputy chief of staff. She got the top job in October 2019, just a few months before COVID-19 clobbered the world and Delaware.

Grant knows the ‘personal touch’ Biden likes in speeches

Through Carney’s nearly six years as governor, Grant also has been his go-to staffer for speechifying. Her range is vast, he said.

She crafted his eulogies for former Govs. Ruth Ann Minnner and Pete du Pont, retired Supreme Court Justice Randy Holland, and Warner Elementary School principal Terrance Newton, who died in the March motorcycle wreck. She even helped write the one Carney gave for his late father Jack in 2014.

During those speeches, Grant was able to help Carney’s oratory meet “the emotional and personal nature” of those somber events, the governor said.

But Grant also penned speeches on a variety of topics, including his annual State of the State address.

‘It’s hard in that it’s long and there’s a lot of detail, but you’ve got to simplify it,’’ Carney said.

The governor said Grant’s addition to Biden’s speechwriting team can only benefit the president, whether it’s for an intimate talk in the White House to a small audience, a sobering message during a national primetime address, or a monumental speech on the global stage.

“We all know the stories that he tells. We all know the emotion that he brings to it. We all know the personal touch,’’ Carney said of Biden’s style. “And she does as well. And I think that’ll really be helpful for her role in this new position.”

Carper agreed.

“I think she’ll rise to the occasion,’’ the senator said. “She’s not only skilled as a communicator, she’s also quite skilled at getting people to work together.”

Carper noted that as chief of staff for Carney, she was the behind-the-scenes force leading Delaware’s “ship of state” through the crippling pandemic for the last two and a half years. He compared the role of chief of staff to that of an orchestra conductor.

“You have all these different instruments, different sounds. And the idea is to try to, at the end of the day, produce a musical product that is pleasant to the ear and welcoming,’’ Carper said.

“And if she can handle all that, she can handle this.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

The free WHYY News Daily newsletter delivers the most important local stories to your inbox.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

You may also like

Bidens return to Pa., visit private family home in Philly suburb before campaign speech

Biden later spoke to a packed house at Strath Haven Middle School in Delaware County where the president took the campaign stage.

4 weeks ago

7 takeaways from Biden’s State of the Union address: Combative attacks on a foe with no name

Here are some key takeaways from the speech.

Mayor Parker to attend State of the Union as guest of U.S. Rep. Dwight Evans

President Biden will deliver his third State of the Union address beginning at 9 p.m. Thursday. Follow WHYY on air and online for live special coverage.

About Cris Barrish

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

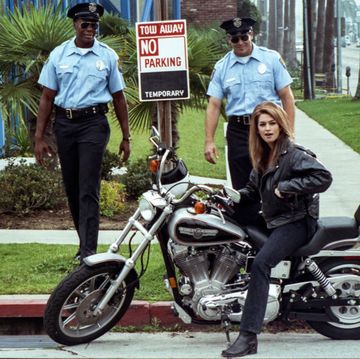

How Amber Macdonald Went From Clowning to Presidential Speechwriting

After nearly seven years of writing Dr. Jill Biden’s speeches and working for the president, Macdonald reflects on how she got there.

“I always wanted to be onstage,” says the Washington, D.C., resident, who jovially admits that she loved being the center of attention. As a child, she was always involved in theater and performance, and through her parents’ church activities she managed to give her first sermon at age 12. As a 20-something in Los Angeles, where she moved after college to pursue her dream of becoming an actress, she worked as a clown and birthday party princess. “There’s nothing like walking into a room dressed as Cinderella and having 20 5-year-olds rush you and tell you that they love you. It’s a great ego boost.”

The daughter of two very religious and politically conservative parents, Macdonald moved around a lot and changed schools a bunch. She lived in New York, Indiana, Georgia, again in Indiana, Florida, and again back in Indiana, all before she graduated high school. Growing up so mobile made her very adaptable. Whenever she had to find new friends or learn her way around a new school or neighborhood, if ever that made her feel untethered, she knew she could always come back to the theater.

“Every school had a theater program,” says Macdonald. “[Moving around that much] made me very attuned to storytelling. That religious tradition of storytelling and rhetoric made a big impression on me.”

If you’re wondering how someone who grew up as a conservative Christian came to be a part of the Biden administration, to Macdonald it doesn’t feel far-fetched.

“Everybody comes to their career for different reasons,” says Macdonald, who has complicated feelings about Christianity but attends a “very liberal Episcopalian Church” every Sunday. “For me, ironically, my mom and I just don’t agree on a lot of things, and we decide what we’re willing to fight about. But the values, her values, the ones she taught me, are why I do what I do. Compassion, justice, mercy, volunteering, giving back — those Christian values that I was raised with, that’s why I do everything I do now [regardless of our] different worldview. At the end of the day, we both want similar things. And if we can find a way to talk to each other, then it becomes less contentious.”

At the other end of the spectrum, the relationship with Dr. Biden seemed to gel from the very beginning.

“When I first met Amber,” says Dr. Biden, “we immediately bonded over our shared love of poetry and literature. Since then, she has been my writing partner and collaborator. From the early days at the Biden Foundation to the 2020 campaign to the White House, she’s been with me every step of the way. She’s incredibly talented, and I’m grateful to her for her years of friendship and teamwork.”

Since she’s taking some time for herself and her family before gearing up for the 2024 presidential election, Macdonald had a rare free moment and talked to Shondaland about what it was like working in the Obama and Biden administrations, how she got started in speechwriting, and why she’s an eternal optimist even though she lives in D.C.

VALENTINA VALENTINI: So, I think the big question is: How did you transition from clowning and princess play into politics?

AMBER MACDONALD: After I had been in Los Angeles for maybe five years, I started to realize that I was not going to be famous [ laughs ]. I wanted someone to care [about] what I had to say, and how else do you do that if not as an actress, a famous person? Like, those people get listened to. But I failed at that, so I need a plan B. I had been volunteering a lot for Planned Parenthood and trying to get involved in campaigns, and eventually I got a job with the Democrats in the [San Fernando] Valley. That eventually led me to a job for a California assemblymember at the time, Bob Blumenfield. I worked as a field rep, which is, you know, the lowest job there, but I was thrilled to be in politics. But I really didn’t know what I was doing, like what my job should be — I’m not a policy person. I’m not a reporter person. So, I just didn’t know what my space there looked like. I finally began to realize how many speeches he had to be giving, and that really, speeches are just playwriting for one person.

VV: And you have a background in playwriting?

AM: In college, I majored in English and theater with an independent study in playwriting. I had written and performed a two-woman show with my best friend. And so, when it came to speechwriting, I thought, “I can do that. I know dialogue; I love writing. I can do this.” I was still writing sketches and blogs in L.A. while I was doing improv at UCB [Upright Citizens Brigade] and auditioning for things and working all those other crazy jobs that people do in L.A. — waitressing, bartending, I was a Merry Maid for a bit and cleaned houses. But I knew that writing was my skill that I had held on to for all these years. So, I thought I could offer to be Blumenfield’s speechwriter.

Speechwriting is a very weird path because there are not a ton of jobs in it. Most offices don’t have the budget for speechwriters besides the Senate. So, Blumenfield couldn’t hire me as a speechwriter, but I would contact him when I knew he was coming into town and ask if I could write his five minutes of remarks. He was really sweet and supportive of me and would say yes. But I remember the first five-minute speech I wrote for him — I spent all day pouring my heart into it, and he read a single line of the 600 words I had put together. It was the best moment of my life, though! That he had read a thing that I wrote, I was so excited. That was when I knew this was a path for me. I could be a writer; I could write inside this world of politics that I really am passionate about and really care about.

VV: It sounds like you learned a lot on the job.

AM: After making the move to D.C., which seemed like the next logical step because of the work I was doing, I interviewed with Congressman Jim McDermott from Seattle. He interviewed me as a speechwriter, I did all these writing tests, and when he gave me the job, he was like, “I can’t afford a speechwriter. So, you have to be my comms director.”

I said that I could definitely do that. And I had no idea how to do that at all. It was very much jump in the fire and figure it out. But he was such a firebrand and wanted really bold speeches. He was in Seattle and could say whatever was in his heart, and it was much less, like, political minded than D.C. usually is. He didn’t mind making people angry. It was a very fun job.

VV: Did you start working with Dr. Biden right after that?

AM: No, no. When I was with him, I was asked to interview for the deputy director of speech-writing [position] for [former] Secretary at Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius, a political appointee under [former President] Obama. I was with HHS for a little while, and I worked for both Kathleen Sebelius and [her successor] Sylvia Mathews Burwell. I became Sylvia’s chief speechwriter and an adviser for her and had amazing experiences working in a cabinet and for HHS. But then I started doing some contracted speechwriting, and that’s when I met Dr. Biden. I was supposed to do just one stump speech for her, but we had a lot of chemistry and got along so well. I think she liked my writing style. So, from that point on in 2017, almost right after the administration ended, we worked together through her foundation, through the campaign, and then the White House.

VV: What is it, exactly, that you do as a presidential speechwriter? Can you pull back the curtain for us?

AM: Having worked on the Hill, having worked at HHS and the private sector and in the White House, there are different approaches, and each speechwriter is going to have a different method. Speechwriting is so much research. I think there’s this idea that it’s like The West Wing with Sam Seaborn [Rob Lowe] as a romantic version of a tortured writer in a little room pouring out poetry, which of course it can be, but it’s so much more. It’s so much research; it’s so much negotiation. Before the writing even starts, I will talk to anybody and everybody that I need to talk to to get the details — who is the audience? What is the message? Why are we doing this speech? What is the point that needs to be made, and what are the policies we need to highlight? All that groundwork needs to be laid out before I even talk to a principal. At that point, it’s “Here are my ideas on what you should talk about” or “What are your ideas? What are the stories that you want to tell? What’s the connection that you have?” Obviously, for Dr. Biden, I know her so well at this point that we had a shorthand. She’d say, “I want to tell that story of my sister.” And I’d know exactly what story she was referring to. But for a new client, a lot of my job is to listen to them and know that they have a story they’re going to give me. I want them to brain-dump on me so that I can tell them what I think is interesting, what I think we can pull from their life, what the themes are that they may not hear. My job is to find those narratives in their personal stories and to communicate that through the work they’re doing, through the policy they’re trying to advance.

Then, there’s all this negotiation that goes on. It might be what the secretary wants to say, but I need to go to their comms team and ask if they’re good with it; then I go to the policy team and ask if we’re getting it right. I always want to speak to people’s hearts to tell stories that compel people, but I still need to be characterizing some tax credit correctly. And then, we need to make sure the lawyers are good with it, or other parties involved. Depending on how big the organization [is], there are anywhere from three to 40 people on my clearance list, with dozens of people often weighing in. That negotiation process is a big part of the job and figuring out how to say something meaningful and inspirational and also true and factual and relevant to the audience. I can then end up going back and forth for a while on drafts. It’s all a very collaborative process. There have definitely been speeches where I wrote a draft and it was done, but that’s rarer.

VV: What does the collaboration with Dr. Biden look like?

AM: One of her favorite critiques was “I like this speech, but it doesn’t make me feel anything.” Not that it always happened, but when there was a speech that had the right message and the right argument and stats, it was speaking to the issues and the audience, but didn’t make her feel anything, I’d have to fix it. Because Dr. Biden always wanted to speak to people’s hearts, to appeal to their sense of love and community and humanity. That was why we worked together for so long, why we enjoy each other so much, because we both have that sense of “I don’t care how many stats you throw at me; if you don’t make me care about this thing, I’m going to walk away from this speech and forget it immediately.”

HHS is such a great example of this because you’re talking about a million acronyms that no one has heard of, phrases like “delivery system reform” and “comorbidities,” and words that everybody hates and nobody knows, and they all shut down. But what we’re talking about — what I’m writing speeches about — is so critical: health insurance. Health insurance saves people’s lives; it changes their lives. It is so difficult sometimes in D.C. to talk about these really complicated things, but they always boil down to “How am I helping my neighbor? How am I going to get this kid to school? How can this person raise a family with a life of dignity?” Those are the stories that we’re trying to tell. And I think the best speeches do that. Some people are great researchers, or they’re doctors or they’re lawyers, and they get the logic and they get the numbers; they’re economists, and that stuff is so important. But at the end of the day, if you can’t talk to my mom who loves Trump about why she needs to sign up for health care …

.css-1n3l8cl{font-family:GTWalsheim,GTWalsheim-weightbold-roboto,GTWalsheim-weightbold-local,Helvetica,sans-serif;font-size:1.625rem;font-weight:bold;line-height:1.2;margin:0rem;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-1n3l8cl{font-size:1.75rem;line-height:1.2;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-1n3l8cl{font-size:1.875rem;line-height:1.2;}}.css-1n3l8cl b,.css-1n3l8cl strong{font-family:inherit;font-weight:bold;}.css-1n3l8cl em,.css-1n3l8cl i{font-style:italic;font-family:inherit;} “I am disheartened all the time by the way [both party's] dialogue is pulling further and further apart, but I’m also an eternal optimist, and I wouldn’t do this job if I didn’t believe that there was a way for us to bridge those gaps.”

VV: That was going to be my next question — the politics of it. You come from a conservative, religious family and now work for the Bidens. I think to all of us outside of D.C., it looks really divided, and there are two stalwart camps, and nobody can talk to each other. But is it really like that?

AM: I am disheartened all the time by the way our dialogue is pulling further and further apart, but I’m also an eternal optimist, and I wouldn’t do this job if I didn’t believe that there was a way for us to bridge those gaps. This is my small part: If I can help a super-liberal congressman from Seattle, or an incredibly brilliant tech Democrat in the HHS, or the first lady talk about these things in a way that says, “Actually, we do both want good jobs; we do both want our kids to have the same access,” and it sounds so Pollyanna, but I really do believe that most Americans want the same things. We just have these very, very different paths to get there. So, if we just sit here, and we say that all Republicans are horrible, where does that get us? I started this job because of women’s rights. I’m so passionate about abortion rights and reproductive justice, and that is an issue that I will never agree with my mother on. But we’ve had these moments where, if we talk for long enough, we can find a place where we agree. It doesn’t happen easily or often, but I know that there is a humanity and a compassion that we share. I have to believe we just have to keep trying. Democracy is a terrible system and the best system we have. So, if we want to elect more people who will do good things, we’ve got to make their case.

VV: So, if you’re a pessimist, political speechwriting might not be the job for you?

AM: Look, there are a lot of cynics in D.C., and I get that. But I have also seen the amazing capacity for hope in that city too. There are people who want power and money, but there are also a lot of people who are there because they want to make things better. And it’s not like we get paid a ton of money or have easy work hours. We’re working hard, and it can be tough out there. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been at a party, and someone found out I worked at the White House and took that as their opportunity to tell me everything that they hate about Joe Biden. And I’ve gotten that from both the right and the left.

VV: Going from clowning, improv, and acting to being this invisible force behind powerful people, how does that sit with you?

AM: It’s funny because I did love performing; I loved improv. But there is also a safety in writing for someone else. I’ve often wondered … and I don’t want to call myself a coward, but it’s that idea of wanting someone to listen to me and becoming a speechwriter was a way to make sure I had a voice and influence in a conversation that I care about without having to be rich or famous or whatever. That was a huge revelation because I am a creative person and I’m still getting a chance to be creative in my writing. It just happens to be in the context of what someone else wants to say. But I still have an angle, a voice inside of that, and nobody knows it’s me. I do think I’m getting to a point in my career, though, where I want to be a little braver and put more out in my own name. And that is hopefully my next chapter.

VV: When you think back on your time with the Bidens, what stands out?

AM: I’m so proud of the work I’ve done. I’m incredibly lucky to have had the chance to be a part of some really important conversations. It was the most important election of our lives, and the next one will be the most important election of our lives, and they will continue to be world-changing elections, and the fact that I got to play a small part in that is so gratifying and so rewarding. Dr. Biden is such a powerful advocate and voice, and she’s such a good messenger for Joe Biden and for herself with this incredible platform. As first lady, she is doing really important stuff . First ladies often get wrongly discounted, but so many of them have done so much, and that goes for Dr. Biden too. Her work helping military families, supporting community colleges, and all of her pillars are so powerful, and they are things I care about too. I’ve seen kids who are truly struggling whose lives are going to be made better because of the work that Dr. Biden is doing.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Valentina Valentini is a London-based entertainment, travel, and food writer and is also a senior contributor to Shondaland. Elsewhere, she has written for Vanity Fair , Vulture , Variety , Thrillist , Heated , and The Washington Post . Her personal essays can be read in the Los Angeles Times and Longreads , and her tangents and general complaints can be seen on Instagram at @ByValentinaV .

Career & Money

Should You Turn Down a Promotion at Work?

I Felt More Lonely in the Office

Head Turners: Brittney Morris

Head Turners: Archaeologist Alexandra Jones

Head Turners: Build-A-Bear CEO Sharon Price John

How to Cut Costs on Pricey Recipes at Home

The Wonderful World of Women Brewers

Head Turners: Astrobiologist Aomawa Shields

The Unstoppable Ambition of Women in Sports

How to Get Paid What You Deserve

5 Traits You Need to Make Ambition Work for You

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

White House Announces Additional Staff

Today, President Biden and Vice President Harris announced the appointments of additional White House staff who will serve in the Office of Administration, White House Counsel’s Office, Office of Legislative Affairs, Office of Management and Administration, White House Military Office, Office of Presidential Correspondence, and Speechwriting. The new staff bring a breadth of exceptional talent, diverse experience, and steadfast dedication to the White House and will play key roles supporting the Biden-Harris Administration’s commitment to tackling the crises facing the country and building back better.

Biographies of the appointees are listed below in alphabetical order and by White House office:

Office of Administration and Office of Management and Administration Faisal Amin, Deputy Director of Management and Administration and the Office of Administration Faisal Amin was most recently on the Vetting Operations team and on the Executive Office of the President Management and Administration Agency Review Team on the Biden-Harris Transition. Prior to the Transition, he served as an Assistant General Counsel for Appropriations Law at the United States Government Accountability Office. Amin served in several roles during the Obama-Biden Administration, including as Director of Administration and Associate Counsel for Fiscal Law in the Office of the Vice President, as Chief Financial Officer of the Executive Office of the President, and as Deputy Chief of Staff in the Office of the Vice President. Originally from California, he earned his undergraduate degree at the University of California, Berkeley, and his law degree at the University of Arizona. He lives in Maryland with his wife and two sons. Dan Jacobson, General Counsel for the Office of Administration Before joining the Biden-Harris Administration, Daniel Jacobson was an attorney at Arnold & Porter in Washington D.C. where he focused on voting rights litigation. Jacobson previously served as an Associate Counsel in the White House Counsel’s Office during the Obama-Biden Administration. Following law school, Jacobson served as a law clerk for the Honorable A. Wallace Tashima on the Ninth Circuit and the Honorable Naomi Reice Buchwald in the Southern District of New York. Originally from New York, Jacobson is a graduate of Harvard Law School and Yale University. Dana Rosenzweig, Deputy Director of Management and Administration for Operations Before joining the Biden-Harris Administration, Dana Rosenzweig was an Engagement Manager at McKinsey & Company, where she led large-scale change management programs focused on leadership and development training and strategic operations. Prior to that, she served in the Obama-Biden Administration as Director of Administration for the Office of the Vice President. Originally from Pennsylvania, Rosenzweig is a graduate of Yale University and The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. White House Counsel’s Office Alicia O’Brien, Senior Counsel Alicia O’Brien served at the Department of Justice as an Associate Deputy Attorney General in the office of Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates, and as a Deputy Assistant Attorney General in the Office of Legislative Affairs during the Obama-Biden Administration. In these roles, she managed the Department’s responses to congressional oversight, prepared senior officials for congressional hearings, and played a key role in the Senate confirmation process for presidentially appointed Department nominees. Before joining the Biden-Harris Administration, O’Brien most recently was a partner at King & Spalding LLP in Washington, D.C. Originally from northern Ohio, O’Brien is a graduate of the University of Maryland and American University Washington College of Law. She lives in Washington, D.C. with her husband and two daughters. Office of Legislative Affairs Jonathan Black, Special Assistant to the President and Senate Legislative Affairs Liaison Jonathan Black served as a Senior Policy Advisor to U.S. Senator Tom Udall of New Mexico on energy and environmental issues from 2013-2021. Prior to that, he served as a Professional Staff Member on the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources Democratic Staff for Chairman Jeff Bingaman of New Mexico and held a variety of other positions on the Committee since 2001. Originally from Long Island, New York, Black is a graduate of the University of Richmond, Virginia and has a M.A. from the George Washington University in Washington, DC. Elizabeth Jurinka, Special Assistant to the President and Senate Legislative Affairs Liaison Elizabeth Jurinka most recently served as Chief Health Advisor to Chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) and the Senate Finance Committee. During her time on the Committee, Jurinka oversaw passage of several major health care bills including the repeal of the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR), the longest CHIP extension since the program’s enactment, and chronic care reform; and led the development of arguments and strategy against several attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Jurinka spearheaded negotiations with the Committee Republicans on prescription drug pricing reform, resulting in Senate Finance Committee passage of the Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act (PDPRA). Prior to her ten years in the Senate, she worked for Congresswoman Melissa L. Bean (IL-8). Born in Washington, DC and raised in Maryland, Elizabeth graduated from University of Maryland with a bachelor’s degree in government and received her master’s in government from Johns Hopkins University. She lives in Washington, DC with her husband and two daughters. Chad Metzler, Special Assistant to the President and Senate Legislative Affairs Liaison Chad Metzler was Legislative Director for U.S. Senator Angus King. Before that he was the Staff Director for the United States Senate Special Committee on Aging, and served as Legislative Director for U.S. Senator Herb Kohl. Metzler is a native of Wisconsin and graduated from the University of Chicago and earned a M.A. in Security Policy at George Washington University’s Elliot School of International Affairs. Jim Secreto, Special Assistant to the President and Director of Confirmations Jim Secreto previously served as Counsel to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, Chief Counsel to the Senate Democratic Policy Committee, and Chief Investigative Counsel to then-Ranking Member Tom Carper on Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee. During the Obama-Biden Administration, he served as Deputy Associate Counsel in the White House Counsel’s Office and in various roles at the U.S. Department of Energy. Born and raised in Michigan, Secreto is a graduate of the University of Michigan, Georgetown University Law Center, and the Harvard Kennedy School. White House Military Office Maju Varghese, Director of the White House Military Office Maju Varghese most recently served as Executive Director of the Presidential Inaugural Committee. Prior to that, Varghese served as Chief Operating Officer and Senior Advisor on the Biden campaign from the primaries through the general election. In the Obama-Biden Administration, Varghese served in multiple roles, including Assistant to the President for Management and Administration and Special Assistant to the President and Deputy Director of Advance. Varghese has also served as a Senior Advisor at Dentons, Chief Operating Officer at the Hub Project and as an Associate at Wade Clark Mulcahy in New York. The son of immigrants from Kerala, India, Varghese was born in New York City and raised in Elmont, New York. Varghese is a graduate of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and the Maurice A. Dean School of Law at Hofstra University. Office of Presidential Correspondence Eva Kemp, Director of Presidential Correspondence Eva Kemp was Vice President of Program at SKDKnickerbocker, managing the direct mail program for the Biden for President campaign. Prior to her role on the campaign, she served as an IE Political Desk at the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and Deputy States Paid Media Director for Mike Bloomberg 2020. Kemp was previously the Louisiana State Director at Democrats for Education Reform (DFER). She also served as a Legislative Assistant for United States Senator Mary Landrieu (D-LA) and Director of Policy and Planning at the Louisiana Department of Education and Recovery School District. Born in Hammond, Louisiana, Kemp is a graduate of Louisiana State University. Speechwriting Amber Macdonald, Senior Presidential Speechwriter Amber Macdonald served as Dr. Jill Biden’s speechwriter during the Biden-Harris campaign. Prior to joining the campaign, she ran her own speechwriting shop, writing for Dr. Biden and other high-profile clients. During the Obama-Biden Administration, Macdonald served as Senior Advisor and Director of Speechwriting for HHS Secretary Sylvia Burwell and Deputy Director of Speechwriting for HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius. Before joining the Administration, she was communications director to Congressman Jim McDermott (WA-07), political director for Howard Berman for Congress, and a field representative for California Assemblymember Bob Blumenfield. Macdonald began her political career working on reproductive health and local political campaigns in Los Angeles, CA. Originally from Indiana, she graduated from Hanover College with a B.A. in Theatre and English. She lives in Washington, D.C. with her husband and twin daughters. Jeff Nussbaum, Senior Presidential Speechwriter Jeff Nussbaum most recently served as a partner at the speechwriting and strategy firm West Wing Writers. He traveled with President Biden during the 2008 Obama-Biden campaign and previously wrote for Vice President Al Gore and Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle. Nussbaum helped oversee speechwriting operations for the 2020 Democratic National Convention and was involved in the past six Democratic conventions. Nussbaum has co-authored books with James Carville and former Senator Bob Graham and has served as a creative consultant for the Kennedy Center Mark Twain Prize for American Humor. Nussbaum was raised in Weston, Massachusetts and is a graduate of Brown University. He is the proud father of two daughters.

Stay Connected

We'll be in touch with the latest information on how President Biden and his administration are working for the American people, as well as ways you can get involved and help our country build back better.

Opt in to send and receive text messages from President Biden.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

How speechwriters delve into a president’s mind: Lots of listening, studying and becoming a mirror

FILE - President Joe Biden delivers the State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress at the U.S. Capitol, Feb. 7, 2023, in Washington. It’s an annual process that former presidential speechwriters say take months. Speechwriters have the uneviable task of taking dozens of ideas and stitching into a cohesive narrative of a president’s vision for the year. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

- Copy Link copied

WASHINGTON (AP) — Speechwriting, in one sense, is essentially being someone else’s mirror.

“You can try to find the right words,” said Dan Cluchey, a former speechwriter for President Joe Biden . “But ultimately, your job is to ensure that when the speech is done, that it has a reflection of the speaker.”

That concept is infinitely magnified in the role of the presidential speechwriter. Over the course of U.S. history, those aides have absorbed the personalities, the quirks, the speech cadences of the most powerful leader on the globe, capturing his thoughts for all manner of public remarks, from the mundane to the historic and most consequential.

There are few times in a presidency that the art — and the rigorous, often painful process — of speechwriting is more on display than during a State of the Union , when the vast array of a president’s policy aspirations and political messages come together in one, hour-plus carefully choreographed address at the Capitol. Biden will deliver the annual address on Thursday .

It’s a process that former White House speechwriters say take months, with untold lobbying and input from various federal agencies and others outside the president’s inner circle who are all working to ensure their favored proposals merit a mention. Speechwriters have the unenviable task of taking dozens of ideas and stitching them into a cohesive narrative of a president’s vision for the year.

It’s less elegant prose, more laundry list of policy ideas.

Amid all those formalities and constraints of a State of the Union address, there is also how a president executes the speech.

Biden’s biggest political liability remains his age (81) and voters’ questions about whether he is still up to the job (his doctor this past week declared him fit to serve ). His every word is watched by Republican operatives eager to capture any misspeak to plant doubt about Biden’s fitness among the public.

“This year, of course, is an election year. It also comes as there’s much more chatter about his age,” said Michael Waldman, who served as a speechwriter for President Bill Clinton. “People are really going to be scrutinizing him for how he delivers the speech, as much as what he says.”

Biden will remain at Camp David through Tuesday and is expected to spend much of that time preparing for the State of the Union. Bruce Reed, the White House deputy chief of staff, accompanied Biden to the presidential retreat outside Washington on Friday evening.

The White House has said lowering costs, shoring up democracy and protecting women’s reproductive care will be among the topics that Biden will address on Thursday night.

Biden likely won’t top the list of the most talented presidential orators. He has thrived the most during small chance encounters with Americans, where interactions can be more off the cuff and intimate.

The plain-spoken Biden is known to hate Washington jargon and the alphabet soup of government acronyms, and he has challenged aides, when writing his remarks, to cut through the clutter and to get to the point with speed. Cluchey, who worked for Biden from 2018 to 2022, said the president was very engaged in the speech drafting process, all the way down to individual lines and words.

Biden can also come across as stiff at times when standing and reading from a teleprompter, but immediately loosens up and appears more comfortable when he switches to a hand-held microphone mid-remark. Biden has also learned to navigate a childhood stutter that he says helped him develop empathy for others facing similar challenges.

To become engrossed in another person’s voice, past presidential speechwriters list things that are critical. One is just doing a lot of listening to the principal, to get a sense of his rhythms and how he uses language.

Lots of direct conversation with the president is key, to try and get inside the commander in chief’s thinking and how that leader frames arguments and make their case.

“This is not an act of impression, where you’re simply just trying to get the accent down,” said Jeff Shesol, another former Clinton speechwriter. “What you really are learning to do and need to learn to do -– this is true of speechwriters in any role, but particularly for a president –- is to understand not just how he sounds, but how he thinks.”

Shesol added: “You’re absorbing not just the rhythms and cadences of speech, but you’re absorbing a worldview.”

Then there is always the matter of the speech-giver going rogue.

Biden is often candid, and White House aides are sometimes left to clean up and clarify what he said in unvarnished moments. But other times when he deviates from the script, it ends up being an improvement on what his aides had scripted.

Take last year’s State of the Union . Biden had launched into an attack prepared in advance against some Republicans who were insisting on requiring renewal votes on popular programs such as Medicare and Social Security, which would effectively threaten their fate every five years.

That prompted heckling from Republicans and shouts of “Liar!” from the audience.

Biden immediately pivoted, egging on the Republicans to contact his office for a copy of the proposal and joking that he was enjoying their “conversion.”

“Folks, as we all apparently agree, Social Security and Medicare is off the — off the books now, right? They’re not to be touched?” Biden continued. The crowd of lawmakers applauded. “All right. All right. We got unanimity!”

Speechwriters do try and prepare for such moments, particularly if a president is known to speak extemporaneously.

Shesol recalled that Clinton’s speechwriters would draft remarks that were relatively spare, to account for him veering off on his own. The writers would write a clear structure into the speech that would allow Clinton to easily return to his prepared remarks once his riff was over.

“Clinton used to liken it to playing a jazz solo and then he’s going back to the score,” Waldman added.

Cluchey, when asked for his reaction when his former boss would go off-script, described it as a “ballet with several movements of, you know, panic, to ‘Wait a minute, this is actually very good,’ and then ‘Oh man, he really nailed it.’”

Biden is “at his best when he’s most authentically, most loosely, just speaking the plain truth,” Cluchey said. “The speechwriting process even at its best has strictures around it.”

Joe Biden's inaugural address is his moment to capture a snapshot of a divided and overwhelmed country

- President-elect Joe Biden will deliver his inaugural address in a moment unlike any other in modern US history.

- Biden has a well-established reputation of delivering remarks that lean on his own personal experiences with grief and tragedy. But his speech after taking the presidential oath of office will be something else entirely.

- Experts in presidential speechwriting say Biden's task at the inauguration is to come up with just the right language to express far more than any singular policy promise, campaign pledge or personal anecdote.

"You want to have words to speak to the moment," said Peter Wehner, a former speechwriter to President George W. Bush. "You want to be able to capture the mood of the country and speak in a way that resonates with the country."

- Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories .

Joe Biden will deliver a presidential inaugural speech unlike any other in modern US history.

It's a monumental oratorical challenge for a career Democratic politician who has given countless speeches as a senator, a vice-president, and three-time White House candidate.

And it comes just 14 days after rioters stormed the Capitol and amid a deadly pandemic that has left hundreds of thousands of Americans dead.

Sure, Biden has going for him a well-established reputation as a master eulogizer whose personal experience with grief and tragedy helped him become the perfect person to deliver memorial service goodbyes.

But his public remarks after completing the famous 35-word presidential oath of office just after noon on January 20th are shaping up to be something totally different than anything like that, according to several experts in White House and inaugural speech making. They'll also be made to a hugely downscaled crowd and as thousands of National Guardsmen watch over a frazzled capital.

Presidential speechwriting experts said the current unprecedented circumstances — the end of Donald Trump's presidency and the double whammy of a global COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic turmoil — will force Biden to come up with just the right language to express far more than any singular policy promise, campaign pledge or personal anecdote.

Biden's inaugural theme is "America United" — a message many Americans are seeking to heal a frazzled country. Biden worked with his chief speechwriter Vinay Reddy, senior advisor Mike Donilon and his family on his inaugural spech, which no doubt has seen big changes since the mob attack.

'You want elegance'

Biden is of course no stranger to delivering big speeches. He's been serving in public office for so long that his lengthy career became a regular Trump attack line of its own during the 2020 presidential campaign.

"My hunch is that at some point in 78 years Joe Biden has thought about what he might say if he were inaugurated as president of the United States," said Daniel Pink, a former speechwriter to Vice President Al Gore.

But this Biden speech is sure to be different than any of those previous ones.

It'll be different from the one he gave earlier this summer in Delaware to accept his party's presidential nomination at the Democratic National Convention. By its very nature, that partisan event was about exciting voters even as his campaign tried to portray their candidate as a uniting force against the divisive politics of the Trump era.

It'll also be different than what Biden said upon defeating Trump in November with a pledge "to be a president who seeks not to divide but unify, who doesn't see red states and blue states, only sees the United States."

When Biden delivers his inaugural address, Americans will be looking for signals of what's to come under his leadership. What they'll likely remember are a couple of lofty phrases.

"You want elegance," Wehner said. "You want to be high, not low. You want to lift the mood of the country. You don't want to override it. You want to be hopeful and often you want to try and put America in this moment. You want to put this moment in the larger arch area of the American story."

COVID-19 logistics and teleprompters

Biden's speech is also shaping up to have significant logistical differences from past inaugurals.

Related stories

There won't be anywhere close to the number of spectators who every four years line the streets of Washington and pack onto the National Mall to listen to the first remarks from the country's newly-sworn in leader. And that decision was made even before security threats.

The plan was always to consult with the organizers of the Democratic National Convention, who helped turn that event into a virtual show featuring people speaking on their phones and desktop computers from across the country.

Much remains under wraps as to the words Biden will actually use. One thing is clear: Biden is surrounded by qualified speech writers. Donilon took on the title last month of chief strategist to the president-elect after serving on the 2020 campaign in a role that included helping to write the DNC speech. Biden also counts among his personal wordsmiths Reddy, Carlyn Reichel, Michael Sheehan, and Jon Meacham, a presidential historian who the New York Times reported helped to craft campaign speeches and his remarks accepting the Democratic party nomination.

And even if the words Biden is supposed to say sing like Shakespeare, it's anyone's guess how much he sticks to the script. The next president is well known for ad-libbing, bringing up personal anecdotes about grief and loss, and for using awkward non-sequitur like "anyway."

There's a reason why the Washington Post in August wrote about the running joke that Biden's speech writers have one of the most challenging jobs in American politics because their boss doesn't like teleprompters and can easily veer off course.

Beat this: 'With malice toward none'

Bill Clinton combed through about 50 drafts of his first presidential inaugural address, pulling all-nighters and practicing his elocution as the incoming commander-in-chief prepped for his big 1993 speech .

Barack Obama edited and edited too, frequently pushing back on his speechwriter's words. But the country's first Black president also amazingly only took one try at practicing his historic 2009 inaugural address before delivering it.

"It was just the type of thing that the president wanted to put to bed in plenty of time so that we could pull off a smooth inaugural," said speechwriter Cody Keenan. He described a timeline for preparing the speech starting in mid-December as excited campaign staffers rushed to move their lives from Chicago to Washington and ultimately wrapped up by Christmas.

"I think we finished up remarkably early for us," Keenan said.

Speech writing experts also cautioned that Biden will need to be careful about getting too personal with his speech. The new president is considered a master of delivering spoken words about grief and loss and personalizing the stories of Americans by relating them via Scripture and his early childhood upbringing in Pennsylvania coal country.

But that kind of approach has fallen flat in the past.

For example, Jimmy Carter in 1977 offered up an anecdote from a high school teacher during his inaugural address that pundits said at the time wasn't up to the historical significance of that speech, according to David Kusnet, a former Clinton chief speechwriter who drafted his 1993 speech.

"Public rhetoric has become much more personal over the years," Kusnet said. "But Franklin Roosevelt didn't talk about overcoming polio, John F. Kennedy didn't talk about being the first Catholic to serve as president or about his own service and injury in World War II."

Unlike campaign speeches or even presidential acceptance speeches, an inaugural address shouldn't be packed with personal reminiscences, anecdotes or "anything in a confessional nature," Kusnet said.

"They tend not to be that personal," he said.

Presidential speechwriting experts said that for Biden to hit a home run in his inaugural he needs to paint a picture of the current moment he's facing — one that shows what he expects to wade through as a leader.

This is how past inaugural speeches get remembered. It's why Abraham Lincoln's remarks from 1865 as the Civil War approached its end — "With malice toward none with charity for all" — are etched on the interior wall of the Washington DC monument to the country's 16th president. It's why school children learn about John F. Kennedy's impassioned plea in 1961 to "ask not what your country can do for you - ask what you can do for your country."

And it's also why Trump will have a place in the history books for his 2017 inauguration pledge to stop the "American carnage" causing violence and poverty in inner cities.

"It tells you," Wehner said, "that there's something about words that live in people's memories and hearts."

Watch: What coronavirus stress is doing to your brain and body

- Main content

Help inform the discussion

Miller Center Presents

The Presidency

Translating presidential ideas into words: Speechwriters in the White House

Watch the UVA Democracy Biennial

The Biennial was originally broadcast September 24-25, 2021

About this video

May 23, 2019

John McConnell, Sarada Peri, Kyle O’Connor (moderator)

By Anna Katherine Clay

“If there’s one thing I hope you take away from this whole session, it’s that being a presidential speechwriter is exactly like you’d think it would be on the West Wing ,” grinned Kyle O’Connor, a speechwriter for President Barack Obama, as laughter rippled through the over-capacity crowd for “Translating presidential ideas into words: Speechwriters in the White House.”

O’Connor joined Sarada Peri, another Obama speechwriter, and John McConnell, speechwriter for President George W. Bush, to share anecdotes and lessons-learned from crafting the words that presidents spoke.

“In a weird way, as speechwriters, we are not coming up with the ideas—there are much smarter people in the building who are developing those ideas,” Peri said. “But in a way, I think that these ideas don’t get crystallized until they get litigated on the page.”

McConnell talked about the week following 9/11, when Bush was scheduled to address a joint session of Congress. On the morning of September 17, McConnell and his staff learned that they had to submit a speech draft to Bush by that evening.

Around 1 p.m., they were called into the Oval Office. “‘How’s the drafting going?’” McConnell recalled Bush asking. “‘Fine, but we’re not quite there,’” McConnell remembered someone responding, as the team struggled with direction and structure.

Bush looked at each writer. “‘Americans have questions,’ he said. ‘They want to know who attacked our country. They want to know why they hate us. They want to know what’s expected of us now. They want to know if we’re at war, how we’re going to fight and win the war.’

“And from there,” McConnell said, “we had a structure for the speech itself.”

O’Connor and Peri pointed out how Obama, as a writer himself, “would write the speech better than we would ourselves, if he had the time,” Peri said. She would meet with the president and he’d start talking about what he wanted to say in the speech; then, he would offer up the format—opening, next paragraph, etc.

“It was so irritating as a writer, because you’d been sitting in your office trying to come up with a structure for hours, and you spend ten minutes with him and he has the whole thing down,” Peri said with a smile, as the crowd laughed.

All three panelists cited the busy and divergent day of a president, moving from one event to another, very different event and still another, and how those events influenced speeches.

Peri remembered working on a speech for Obama prior to Pope Francis’s visit; the two had sent the speech back and forth several times over a few days. On the day before the Pope’s visit, Peri was called into the president’s private dining room, where he sat at the table, poring over the speech. He showed Peri that he had added a specific section about refugees; Peri later learned that Obama had been in a meeting about refugees earlier in the day, which influenced the addition.

“What was so interesting about that day was to watch the evolution of his thinking—even though there was so much going on, in those few minutes he had to focus in on this speech, and give it the thinking it needed,” Peri said.

While Bush wasn’t a writer, McConnell said, he was a scrupulous editor. “He could read an eight-page speech draft, throw it down, look at the ceiling and recite to you the outline of the speech,” McConnell said.

McConnell also talked about the importance of authenticity and the contrasting styles of direct messaging through a medium like Twitter versus the back-and-forth between a president and his speechwriting team, where “you are also authentic when you are saying what you want to say in the best way you know how to say it.”

O’Connor and Peri talked of the pressures of “being funny” for the White House Correspondents’ Dinner speech, as well as how Obama’s presidency in particular followed the growth of social media, learning to communicate in a new way. First Lady Michelle Obama, Peri said, was “on the cutting edge of reaching audiences through social media.”

The trio also discussed process: While the Bush speechwriting team passed around paper drafts of each speech among staff in the White House, marking with pen, the Obama teams shared speech files electronically.

“Colin Powell said one time, ‘Everyone likes to grade papers,’” McConnell said, in reference to the preferred methodology at the time. The lead speechwriter’s name and phone number were also written at the bottom of the page, McConnell said, so they could be contacted about it at any time.

All three stressed the importance of learning your audience—before you begin writing.

“The audience is the world for any speech,” Peri said. Just as important, McConnell said, was capturing the president’s style and voice, remembering as you wrote: “This isn’t me talking—it’s him.”

PRESIDENTIAL SPEECHWRITERS

TOM PUTNAM: What better way to celebrate Presidents’ Day than at the nation’s memorial to our 35 th President and in the company of one of his most trusted advisors? I'm Tom Putnam, the Director of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. And on behalf of John Shattuck, CEO of the Kennedy Library Foundation and all of my Library and Foundation colleagues, I want to welcome you to this very special forum. Let me begin by thanking all of you for coming, by acknowledging those watching this program on C-SPAN and listening on public radio, and by expressing appreciation to the sponsors of the Kennedy Library forums, including lead sponsor, Bank of America, Boston Capital, The Lowell Institute, the Boston Foundation, Corcoran Jennison Companies, as well as our media sponsors, The Boston Globe, WBUR, and NECN.

As you know, today’s national holiday began first as a tribute to George Washington, then was later wedded to the birthday of Abraham Lincoln. In more recent times, it has become popularly known as Presidents’ Day, continuing the tradition of honoring Washington and Lincoln and highlighting one of the hallmarks of our democracy, the peaceful transfer of power between all those who have served in our nation’s highest office. It is a day devoted to history, to harkening back to the famous words of Abraham Lincoln, to the mystic chords of memory, and to learning from those who have preceded us. For just as President Kennedy instructed Theodore Sorensen to study the secret of Lincoln’s rhetoric, many recent presidential speechwriters describe how they in turn spent hours examining the speech craft of Kennedy and Sorensen. For those budding speechwriters in today’s audience, one of Mr. Sorensen’s conclusions was that Abraham Lincoln never used two or three words where one would do, so I promise to try and make my introduction of today’s speakers brief. [laughter]

Theodore Sorensen served for 11 years as policy advisor, legal counsel and speechwriter to Senator and President John F. Kennedy. He was deeply involved in such presidential decisions as the Cuban Missile Crisis, civil rights legislation, and the decision to send a man to the moon. He is the author of numerous books, including his best-selling biography, Kennedy , and Let the Word Go Forth , a selection of the best JFK speeches. He is also an international lawyer, lecturer and writer.

If you’ll allow me one anecdote, I once had the privilege of going through our Museum with Mr. Sorensen, his wife Gillian, who is here with us today and will be a featured speaker at our next Kennedy Library Forum, and their daughter Juliet. After watching the renowned 1961 inaugural address, I asked Mr. Sorensen the following question. Recalling the catechism of my youth, I speculated that some of the religious references in President Kennedy’s speeches were more Unitarian in their world view than Roman Catholic. And I asked Mr. Sorensen, who was raised Unitarian in Lincoln, Nebraska, if that topic had ever come up in conversation with the President. It turns out it had. He recounted to me an exchange in which President Kennedy once asked him, “So, Ted, has my Catholicism begun to rub off on you yet?” Mr. Sorensen’s reply was, “No, I’m sorry, Mr. President. On the contrary, it’s my Unitarianism that's finding its way into your speeches.” [laughter]

We're honored to have three other presidential speechwriters joining in today’s conversation who I’ll introduce chronologically. It was exactly 40 years ago on this very holiday, Washington’s Birthday in 1967, that Raymond K. Price received the phone call that would change his life. It was an invitation to join the campaign staff of Richard Nixon, who was considering mounting a second run for the presidency in 1968. Over time, Mr. Price became a close friend, advisor, speechwriter, and special consultant to the President. He was the President’s collaborator on both inaugural addresses, all of his State of the Union speeches, and President Nixon’s 1974 announcement from the Oval Office that he would resign. Mr. Price had a distinguished career as a journalist, editor and public policy analyst and served for many years as the President of the Economic Club of New York.

Chriss Winston was the first woman to head the White House Office of Speechwriting and she was named Director of Speechwriting for President George H. W. Bush. She was also the Deputy Director of Communications for Bush/Quayle in 1988 and oversaw communications for the Department of Labor under President Reagan. She’s the author of numerous books, including the forthcoming How to Raise an American in which, among other suggestions, she advises parents to bring their children to Boston to learn of this city’s rich history and to visit the Museum at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. We’ll provide a free plug for any book that does the same for our Museum. [laughter] Ms. Winston is currently serving as a fellow at the Institute of Politics at the John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Ted Widmer came to the Kennedy Library six years ago when he was charged by President Clinton to survey the field of presidential libraries in preparation for the design of the Clinton Library in Arkansas. It is no surprise that President Clinton would have charged him with this task, for not only is Mr. Widmer a historian by training, he also served from 1997 to 2001 as a foreign policy speechwriter and senior advisor to President Clinton. He is known for the creative programs he has designed to enliven the teaching of American history and politics to diverse groups, ranging from Muslim college students living in countries that have been historically suspicious of western culture, and to underprivileged children living in our own country with limited access to libraries and history museums. He is currently the Director of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Moderating today’s forum is one of the most recognizable and trusted voices in national journalism, Linda Wertheimer. Currently Senior National Correspondent for National Public Radio, for 13 years she was the host of NPR’s flagship news magazine All Things Considered . In her 30 years with NPR, she anchored dozens of nominating conventions and election nights, and has reported on countless presidential addresses. She knows a good speech when she hears one, and we're so fortunate to have her here today to guide today’s conversation, Linda Wertheimer. [applause]

LINDA WERTHEIMER: Thank you very much. Thank you. As perhaps you know, the format of this event will be to hear from the speechwriters, to hear some of the speeches that presidents have given, and to then have an opportunity for you all to ask questions. So I'm going to keep my part of this very brief, since these are all people who have a way with words. I don’t need to do very much. So let me just begin by saying that the first clip you will hear, this is a speech that John Kennedy gave at American University. And it was an important policy speech, because he introduced the idea of a test ban treaty and said that the United States would take the voluntary step of banning atmospheric testing. So it was a very important speech in terms of making news for people like me, but it was also a tremendously important speech because it talked about world peace, as you're just about to hear. We have two clips that have been put together, so this is a somewhat telescoped version of the speech.

PRESIDENT KENNEDY: I have, therefore, chosen this time and place to discuss a topic on which ignorance too often abounds and the truth too rarely perceived – yet it is the most important topic on earth, peace.

What kind of a peace do I mean? What kind of a peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, the kind that enables men and nations to grow and to hope and build a better life for their children. Not merely peace for Americans, but peace for all men and women. Not merely peace in our time, but peace for all time.

I speak of peace because of the new face of war. Total war makes no sense in an age where great powers can maintain large and relatively invulnerable nuclear forces and refuse to surrender without resort to those forces. It makes no sense in an age where a single nuclear weapon contains almost ten times the explosive force delivered by all the allied air forces in the Second World War. It makes no sense in an age when the deadly poisons produced by a nuclear exchange would be carried by wind and water and soil and seed to the far corners of the globe and a generation yet unborn.

Today, the expenditure of billions of dollars every year on weapons acquired for the purpose of making sure we never need to use them is essential to the keeping of peace. But surely the acquisition of such idle stockpiles, which can only destroy and never create, is not the only, much less the most efficient, means of assuring peace.

I speak of peace, therefore, as the necessary rational end of rational man. I realize the pursuit of peace is not as dramatic as the pursuit of war and frequently the words of the pursuers fall on deaf ears. But we have no more urgent task.

For we are both devoting massive sums of money to weapons that could be better devoted to combat ignorance, poverty and disease. We are both caught up in a vicious and dangerous cycle in which suspicion on one side breeds suspicion on the other, and new weapons beget counter weapons.

In short, both the United States and its allies, and the Soviet Union and its allies, have a mutually deep interest in a just and genuine peace and in halting the arms race. Agreements to this end are in the interests of the Soviet Union as well as ours. And even the most hostile nations can be relied upon to accept and keep those treaty obligations, and only those treaty obligations, which are in their own interests.