What Is Creative Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 20 Examples)

Creative writing begins with a blank page and the courage to fill it with the stories only you can tell.

I face this intimidating blank page daily–and I have for the better part of 20+ years.

In this guide, you’ll learn all the ins and outs of creative writing with tons of examples.

What Is Creative Writing (Long Description)?

Creative Writing is the art of using words to express ideas and emotions in imaginative ways. It encompasses various forms including novels, poetry, and plays, focusing on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary tropes.

Table of Contents

Let’s expand on that definition a bit.

Creative writing is an art form that transcends traditional literature boundaries.

It includes professional, journalistic, academic, and technical writing. This type of writing emphasizes narrative craft, character development, and literary tropes. It also explores poetry and poetics traditions.

In essence, creative writing lets you express ideas and emotions uniquely and imaginatively.

It’s about the freedom to invent worlds, characters, and stories. These creations evoke a spectrum of emotions in readers.

Creative writing covers fiction, poetry, and everything in between.

It allows writers to express inner thoughts and feelings. Often, it reflects human experiences through a fabricated lens.

Types of Creative Writing

There are many types of creative writing that we need to explain.

Some of the most common types:

- Short stories

- Screenplays

- Flash fiction

- Creative Nonfiction

Short Stories (The Brief Escape)

Short stories are like narrative treasures.

They are compact but impactful, telling a full story within a limited word count. These tales often focus on a single character or a crucial moment.

Short stories are known for their brevity.

They deliver emotion and insight in a concise yet powerful package. This format is ideal for exploring diverse genres, themes, and characters. It leaves a lasting impression on readers.

Example: Emma discovers an old photo of her smiling grandmother. It’s a rarity. Through flashbacks, Emma learns about her grandmother’s wartime love story. She comes to understand her grandmother’s resilience and the value of joy.

Novels (The Long Journey)

Novels are extensive explorations of character, plot, and setting.

They span thousands of words, giving writers the space to create entire worlds. Novels can weave complex stories across various themes and timelines.

The length of a novel allows for deep narrative and character development.

Readers get an immersive experience.

Example: Across the Divide tells of two siblings separated in childhood. They grow up in different cultures. Their reunion highlights the strength of family bonds, despite distance and differences.

Poetry (The Soul’s Language)

Poetry expresses ideas and emotions through rhythm, sound, and word beauty.

It distills emotions and thoughts into verses. Poetry often uses metaphors, similes, and figurative language to reach the reader’s heart and mind.

Poetry ranges from structured forms, like sonnets, to free verse.

The latter breaks away from traditional formats for more expressive thought.

Example: Whispers of Dawn is a poem collection capturing morning’s quiet moments. “First Light” personifies dawn as a painter. It brings colors of hope and renewal to the world.

Plays (The Dramatic Dialogue)

Plays are meant for performance. They bring characters and conflicts to life through dialogue and action.

This format uniquely explores human relationships and societal issues.

Playwrights face the challenge of conveying setting, emotion, and plot through dialogue and directions.

Example: Echoes of Tomorrow is set in a dystopian future. Memories can be bought and sold. It follows siblings on a quest to retrieve their stolen memories. They learn the cost of living in a world where the past has a price.

Screenplays (Cinema’s Blueprint)

Screenplays outline narratives for films and TV shows.

They require an understanding of visual storytelling, pacing, and dialogue. Screenplays must fit film production constraints.

Example: The Last Light is a screenplay for a sci-fi film. Humanity’s survivors on a dying Earth seek a new planet. The story focuses on spacecraft Argo’s crew as they face mission challenges and internal dynamics.

Memoirs (The Personal Journey)

Memoirs provide insight into an author’s life, focusing on personal experiences and emotional journeys.

They differ from autobiographies by concentrating on specific themes or events.

Memoirs invite readers into the author’s world.

They share lessons learned and hardships overcome.

Example: Under the Mango Tree is a memoir by Maria Gomez. It shares her childhood memories in rural Colombia. The mango tree in their yard symbolizes home, growth, and nostalgia. Maria reflects on her journey to a new life in America.

Flash Fiction (The Quick Twist)

Flash fiction tells stories in under 1,000 words.

It’s about crafting compelling narratives concisely. Each word in flash fiction must count, often leading to a twist.

This format captures life’s vivid moments, delivering quick, impactful insights.

Example: The Last Message features an astronaut’s final Earth message as her spacecraft drifts away. In 500 words, it explores isolation, hope, and the desire to connect against all odds.

Creative Nonfiction (The Factual Tale)

Creative nonfiction combines factual accuracy with creative storytelling.

This genre covers real events, people, and places with a twist. It uses descriptive language and narrative arcs to make true stories engaging.

Creative nonfiction includes biographies, essays, and travelogues.

Example: Echoes of Everest follows the author’s Mount Everest climb. It mixes factual details with personal reflections and the history of past climbers. The narrative captures the climb’s beauty and challenges, offering an immersive experience.

Fantasy (The World Beyond)

Fantasy transports readers to magical and mythical worlds.

It explores themes like good vs. evil and heroism in unreal settings. Fantasy requires careful world-building to create believable yet fantastic realms.

Example: The Crystal of Azmar tells of a young girl destined to save her world from darkness. She learns she’s the last sorceress in a forgotten lineage. Her journey involves mastering powers, forming alliances, and uncovering ancient kingdom myths.

Science Fiction (The Future Imagined)

Science fiction delves into futuristic and scientific themes.

It questions the impact of advancements on society and individuals.

Science fiction ranges from speculative to hard sci-fi, focusing on plausible futures.

Example: When the Stars Whisper is set in a future where humanity communicates with distant galaxies. It centers on a scientist who finds an alien message. This discovery prompts a deep look at humanity’s universe role and interstellar communication.

Watch this great video that explores the question, “What is creative writing?” and “How to get started?”:

What Are the 5 Cs of Creative Writing?

The 5 Cs of creative writing are fundamental pillars.

They guide writers to produce compelling and impactful work. These principles—Clarity, Coherence, Conciseness, Creativity, and Consistency—help craft stories that engage and entertain.

They also resonate deeply with readers. Let’s explore each of these critical components.

Clarity makes your writing understandable and accessible.

It involves choosing the right words and constructing clear sentences. Your narrative should be easy to follow.

In creative writing, clarity means conveying complex ideas in a digestible and enjoyable way.

Coherence ensures your writing flows logically.

It’s crucial for maintaining the reader’s interest. Characters should develop believably, and plots should progress logically. This makes the narrative feel cohesive.

Conciseness

Conciseness is about expressing ideas succinctly.

It’s being economical with words and avoiding redundancy. This principle helps maintain pace and tension, engaging readers throughout the story.

Creativity is the heart of creative writing.

It allows writers to invent new worlds and create memorable characters. Creativity involves originality and imagination. It’s seeing the world in unique ways and sharing that vision.

Consistency

Consistency maintains a uniform tone, style, and voice.

It means being faithful to the world you’ve created. Characters should act true to their development. This builds trust with readers, making your story immersive and believable.

Is Creative Writing Easy?

Creative writing is both rewarding and challenging.

Crafting stories from your imagination involves more than just words on a page. It requires discipline and a deep understanding of language and narrative structure.

Exploring complex characters and themes is also key.

Refining and revising your work is crucial for developing your voice.

The ease of creative writing varies. Some find the freedom of expression liberating.

Others struggle with writer’s block or plot development challenges. However, practice and feedback make creative writing more fulfilling.

What Does a Creative Writer Do?

A creative writer weaves narratives that entertain, enlighten, and inspire.

Writers explore both the world they create and the emotions they wish to evoke. Their tasks are diverse, involving more than just writing.

Creative writers develop ideas, research, and plan their stories.

They create characters and outline plots with attention to detail. Drafting and revising their work is a significant part of their process. They strive for the 5 Cs of compelling writing.

Writers engage with the literary community, seeking feedback and participating in workshops.

They may navigate the publishing world with agents and editors.

Creative writers are storytellers, craftsmen, and artists. They bring narratives to life, enriching our lives and expanding our imaginations.

How to Get Started With Creative Writing?

Embarking on a creative writing journey can feel like standing at the edge of a vast and mysterious forest.

The path is not always clear, but the adventure is calling.

Here’s how to take your first steps into the world of creative writing:

- Find a time of day when your mind is most alert and creative.

- Create a comfortable writing space free from distractions.

- Use prompts to spark your imagination. They can be as simple as a word, a phrase, or an image.

- Try writing for 15-20 minutes on a prompt without editing yourself. Let the ideas flow freely.

- Reading is fuel for your writing. Explore various genres and styles.

- Pay attention to how your favorite authors construct their sentences, develop characters, and build their worlds.

- Don’t pressure yourself to write a novel right away. Begin with short stories or poems.

- Small projects can help you hone your skills and boost your confidence.

- Look for writing groups in your area or online. These communities offer support, feedback, and motivation.

- Participating in workshops or classes can also provide valuable insights into your writing.

- Understand that your first draft is just the beginning. Revising your work is where the real magic happens.

- Be open to feedback and willing to rework your pieces.

- Carry a notebook or digital recorder to jot down ideas, observations, and snippets of conversations.

- These notes can be gold mines for future writing projects.

Final Thoughts: What Is Creative Writing?

Creative writing is an invitation to explore the unknown, to give voice to the silenced, and to celebrate the human spirit in all its forms.

Check out these creative writing tools (that I highly recommend):

Read This Next:

- What Is a Prompt in Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 200 Examples)

- What Is A Personal Account In Writing? (47 Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Short Story (Ultimate Guide + Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Romance Novel [21 Tips + Examples)

How to Write a Band 6 Creative?

HSC Module B: Band 6 Notes on T.S. Eliot’s Poetry

Full mark band 6 creative writing sample.

- Uncategorized

- creative writing

- creative writing sample

Following on from our blog post on how to write creatives , this is a sample of a creative piece written in response to:

“Write a creative piece capturing a moment of tension. Select a theme from Module A, B or C as the basis of your story.”

The theme chosen was female autonomy from Kate Chopin’s The Awakening (Module C prescribed text).

This creative piece also took inspiration from Cate Kennedy’s Whirlpool .

Summer of 2001

For a moment, the momentum she gained galloping in the blossoming garden jolted, and she deflated like a balloon blown by someone suddenly out of breath. A half-smile, captured by the blinking shutter.

Out spluttered the monochrome snapshot. A bit crumpled. A little too bright.

Two dark brown braids, held by clips and bands and flowers, unruliness constrained. The duplicate of her figure came out in the Polaroid sheltered between a stoic masculine figure, and two younger ones just as unsmiling as their father. The mother stood like a storefront mannequin, the white pallor of her skin unblemished by her lurid maroon blush.

Father told the children that their mother was sick. That’s all. Having nightmares about their grandmother who left mother as a child. “Ran off,” he had said, and his nose twitched violently. “Left a family motherless, wifeless.”

I run, too, the girl had thought excitedly. When she ran, she could see the misty grey of the unyielding lamp-posts, and hear the same grunts and coos of pigeons unable to sing, melodies half-sang, half-dissonant. Why don’t they ever sing? Like the parrots and the cockatoos and lorikeets?

Out spluttered another photograph.

Void of the many distresses as analogous to adulthood, her face brimmed with childlike innocence, untroubled by the silhouettes of her father and brothers.

Spring of 2012

“Can you take a picture for us?”

She was on the other side of the camera, and for a moment she was lost in a transitory evocation of her childhood. The soft blush of the children and the hardened faces of the adults. The forced tightness of their figures. They too looked happy, she supposed, amidst the golden sand and waves that wash the shore.

Away from the flippancy of clinking wine glasses and high-pitched gossip, she felt could almost hear the ticking seconds of each minute, each hour.

She returned the phone to the family.

How still they stood! The unmoving figures on the compact screen. A snapshot of the present that has instantaneously become the past. If only her childhood could extend infinitely to her present, and future, then she would again experience that luscious happiness that seemed to ebb with age. The warm embrace by her mother. The over-protectiveness of her father. How strange it was, to think that she had once avoided both.

But no matter.

She can’t return to the past. All she could do is reminisce about it. It was futile, she knew. The physician had told her so.

“Think about the present!” he had said. “You live too much in the past! Talk to your family! Your husband!”. After a glance at the confounded face, he added, “You grew up with caring brothers, I believe?”.

She nodded.

“Surely,” he elongated the word so that it extended into the unforeseeable future, “they must understand.”

No, they didn’t, she thought. Not after their Marmee left.

She remembered how perfect her family had been, captured undyingly on that monochrome photograph. Her brothers and her, mother and father. Yes, what a perfect family. Oh, how the opened eye of the camera would watch apathetically as they fastened together, to perfection.

It all fell apart five weeks afterwards, as they listened her father’s monotonous voice reading the last remnant of their mother – a note declaring how their perfection had compromised her, been too stifling, just as that Summer’s humidity had been. Wasn’t that what it meant to be a family, she had thought, to let give you to others willingly for the happiness of the entire family?

Absentmindedly, the grown woman picked up a bayberry branch and drew circles upon circles on the siliceous shore. Where it touched, the sand darkened and lightened again as the water rose.

The ultimatum of my life, she proposed to herself, a rebellious dive at sea! Amused by her dramatism, she continued to muse. How simple it would be, washed away and never coming back. Her family now was perfect enough. Big house. Big car. Big parties. Big dreams. But happiness? She thought of the riot of colour and flashing cameras that her husband loved. Oh, how they caused her migraines! And his insistence for her to abandon those childhood passions of hers, strolling amidst sunny afternoons amidst the greenery, only embody their “Marmee” and his “Honey”. How ridiculous!

Her hand halted to a stop.

For a fleeting moment, the continuum of her oblivion terminated, the angular momentum her hand gained by drawing those perfect circles on the shore jolted. She inflated with the sudden realisation of what she had written on the sand.

Short, and incomplete without the usual Jennings that followed it. But her name nonetheless.

Yes, those ephemeral imprints of her name will be washed away by the infinite rise and fall of the tide. But she still watched. So that when the present became the past, she would still have a snapshot in her memory to hold on to.

She knew she could not go, just like her name. Into the ocean and never come back. She could not possibly go like her mother, who when she was eleven, left a family without a mother and husband without a wife. She could not possibly go like her mother, who left a daughter crushed by the milliseconds of perfection that succumbs so soon after the click of a camera.

With a long sigh, she turned back and the sea becoming a reverberating picture of her past. Intangible, yet outrageously glorious…

11th March, 2015

The mother, on her phone, manicured fingernails swiping the screen absentmindedly. Across the room, the father looked concerned at both the inattentiveness of his wife and the sounds of clanking metal emanating from the cameramen.

“We’re ready, Mrs Jennings,” said one of them, “Please get into position for the family photo!”

The opened eye of the camera watched as the family fastened itself together, the rosy-cheeked daughter and son, the unison of the family creating the epitome of perfection. They smiled vibrant smiles, posed jovially at the flashing lights.

But immediately after the click of the shutters, they all fell apart, insubstantial as a wish.

- Amy #molongui-disabled-link How our ex-student and current tutor transferred to a Selective School

- Amy #molongui-disabled-link HSC Module B: Band 6 Notes on T.S. Eliot's Poetry

- Amy #molongui-disabled-link How to Write a Band 6 Creative?

- Amy #molongui-disabled-link How to Write a Band 6 Discursive?

Related posts

When to start preparing for OC exam and why is it important to prep early

Top Selective School Graduate’s Tips on the English section of the OC exam

JP English Student Successes: How Andy scored 99.95 ATAR and Band 6 in English Advanced

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 14, 2023

10 Types of Creative Writing (with Examples You’ll Love)

A lot falls under the term ‘creative writing’: poetry, short fiction, plays, novels, personal essays, and songs, to name just a few. By virtue of the creativity that characterizes it, creative writing is an extremely versatile art. So instead of defining what creative writing is , it may be easier to understand what it does by looking at examples that demonstrate the sheer range of styles and genres under its vast umbrella.

To that end, we’ve collected a non-exhaustive list of works across multiple formats that have inspired the writers here at Reedsy. With 20 different works to explore, we hope they will inspire you, too.

People have been writing creatively for almost as long as we have been able to hold pens. Just think of long-form epic poems like The Odyssey or, later, the Cantar de Mio Cid — some of the earliest recorded writings of their kind.

Poetry is also a great place to start if you want to dip your own pen into the inkwell of creative writing. It can be as short or long as you want (you don’t have to write an epic of Homeric proportions), encourages you to build your observation skills, and often speaks from a single point of view .

Here are a few examples:

“Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.

This classic poem by Romantic poet Percy Shelley (also known as Mary Shelley’s husband) is all about legacy. What do we leave behind? How will we be remembered? The great king Ozymandias built himself a massive statue, proclaiming his might, but the irony is that his statue doesn’t survive the ravages of time. By framing this poem as told to him by a “traveller from an antique land,” Shelley effectively turns this into a story. Along with the careful use of juxtaposition to create irony, this poem accomplishes a lot in just a few lines.

“Trying to Raise the Dead” by Dorianne Laux

A direction. An object. My love, it needs a place to rest. Say anything. I’m listening. I’m ready to believe. Even lies, I don’t care.

Poetry is cherished for its ability to evoke strong emotions from the reader using very few words which is exactly what Dorianne Laux does in “ Trying to Raise the Dead .” With vivid imagery that underscores the painful yearning of the narrator, she transports us to a private nighttime scene as the narrator sneaks away from a party to pray to someone they’ve lost. We ache for their loss and how badly they want their lost loved one to acknowledge them in some way. It’s truly a masterclass on how writing can be used to portray emotions.

If you find yourself inspired to try out some poetry — and maybe even get it published — check out these poetry layouts that can elevate your verse!

Song Lyrics

Poetry’s closely related cousin, song lyrics are another great way to flex your creative writing muscles. You not only have to find the perfect rhyme scheme but also match it to the rhythm of the music. This can be a great challenge for an experienced poet or the musically inclined.

To see how music can add something extra to your poetry, check out these two examples:

“Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen

You say I took the name in vain I don't even know the name But if I did, well, really, what's it to ya? There's a blaze of light in every word It doesn't matter which you heard The holy or the broken Hallelujah

Metaphors are commonplace in almost every kind of creative writing, but will often take center stage in shorter works like poetry and songs. At the slightest mention, they invite the listener to bring their emotional or cultural experience to the piece, allowing the writer to express more with fewer words while also giving it a deeper meaning. If a whole song is couched in metaphor, you might even be able to find multiple meanings to it, like in Leonard Cohen’s “ Hallelujah .” While Cohen’s Biblical references create a song that, on the surface, seems like it’s about a struggle with religion, the ambiguity of the lyrics has allowed it to be seen as a song about a complicated romantic relationship.

“I Will Follow You into the Dark” by Death Cab for Cutie

If Heaven and Hell decide that they both are satisfied Illuminate the no's on their vacancy signs If there's no one beside you when your soul embarks Then I'll follow you into the dark

You can think of song lyrics as poetry set to music. They manage to do many of the same things their literary counterparts do — including tugging on your heartstrings. Death Cab for Cutie’s incredibly popular indie rock ballad is about the singer’s deep devotion to his lover. While some might find the song a bit too dark and macabre, its melancholy tune and poignant lyrics remind us that love can endure beyond death.

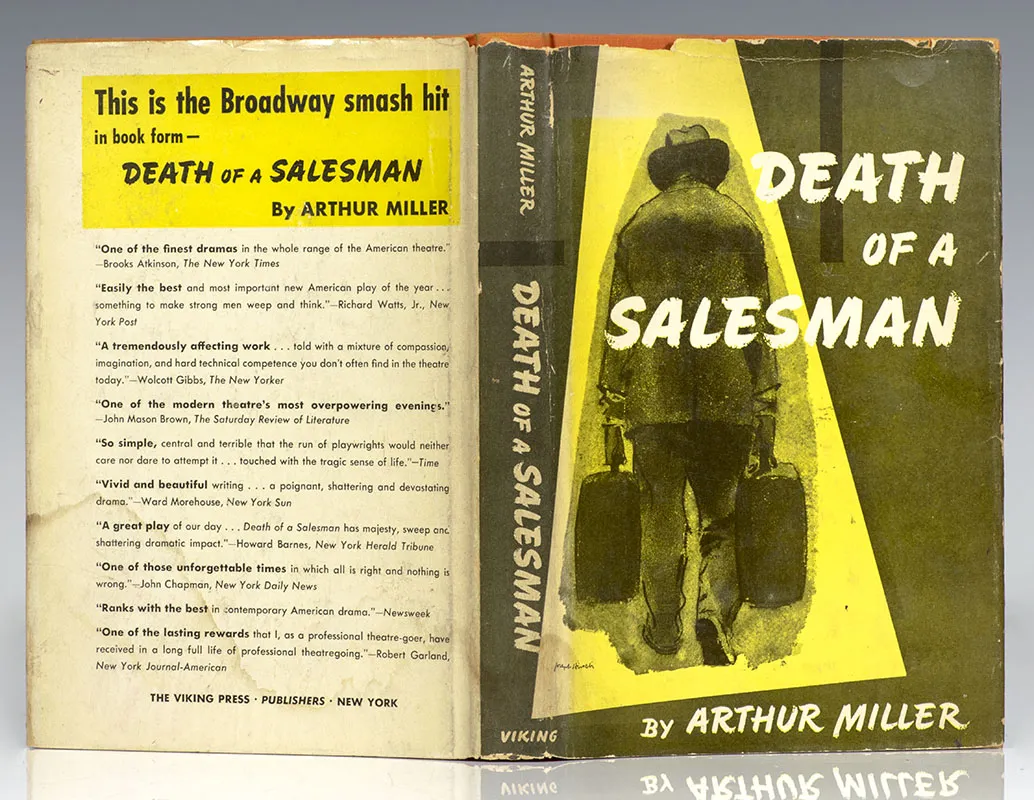

Plays and Screenplays

From the short form of poetry, we move into the world of drama — also known as the play. This form is as old as the poem, stretching back to the works of ancient Greek playwrights like Sophocles, who adapted the myths of their day into dramatic form. The stage play (and the more modern screenplay) gives the words on the page a literal human voice, bringing life to a story and its characters entirely through dialogue.

Interested to see what that looks like? Take a look at these examples:

All My Sons by Arthur Miller

“I know you're no worse than most men but I thought you were better. I never saw you as a man. I saw you as my father.”

Arthur Miller acts as a bridge between the classic and the new, creating 20th century tragedies that take place in living rooms and backyard instead of royal courts, so we had to include his breakout hit on this list. Set in the backyard of an all-American family in the summer of 1946, this tragedy manages to communicate family tensions in an unimaginable scale, building up to an intense climax reminiscent of classical drama.

💡 Read more about Arthur Miller and classical influences in our breakdown of Freytag’s pyramid .

“Everything is Fine” by Michael Schur ( The Good Place )

“Well, then this system sucks. What...one in a million gets to live in paradise and everyone else is tortured for eternity? Come on! I mean, I wasn't freaking Gandhi, but I was okay. I was a medium person. I should get to spend eternity in a medium place! Like Cincinnati. Everyone who wasn't perfect but wasn't terrible should get to spend eternity in Cincinnati.”

A screenplay, especially a TV pilot, is like a mini-play, but with the extra job of convincing an audience that they want to watch a hundred more episodes of the show. Blending moral philosophy with comedy, The Good Place is a fun hang-out show set in the afterlife that asks some big questions about what it means to be good.

It follows Eleanor Shellstrop, an incredibly imperfect woman from Arizona who wakes up in ‘The Good Place’ and realizes that there’s been a cosmic mixup. Determined not to lose her place in paradise, she recruits her “soulmate,” a former ethics professor, to teach her philosophy with the hope that she can learn to be a good person and keep up her charade of being an upstanding citizen. The pilot does a superb job of setting up the stakes, the story, and the characters, while smuggling in deep philosophical ideas.

Personal essays

Our first foray into nonfiction on this list is the personal essay. As its name suggests, these stories are in some way autobiographical — concerned with the author’s life and experiences. But don’t be fooled by the realistic component. These essays can take any shape or form, from comics to diary entries to recipes and anything else you can imagine. Typically zeroing in on a single issue, they allow you to explore your life and prove that the personal can be universal.

Here are a couple of fantastic examples:

“On Selling Your First Novel After 11 Years” by Min Jin Lee (Literary Hub)

There was so much to learn and practice, but I began to see the prose in verse and the verse in prose. Patterns surfaced in poems, stories, and plays. There was music in sentences and paragraphs. I could hear the silences in a sentence. All this schooling was like getting x-ray vision and animal-like hearing.

This deeply honest personal essay by Pachinko author Min Jin Lee is an account of her eleven-year struggle to publish her first novel . Like all good writing, it is intensely focused on personal emotional details. While grounded in the specifics of the author's personal journey, it embodies an experience that is absolutely universal: that of difficulty and adversity met by eventual success.

“A Cyclist on the English Landscape” by Roff Smith (New York Times)

These images, though, aren’t meant to be about me. They’re meant to represent a cyclist on the landscape, anybody — you, perhaps.

Roff Smith’s gorgeous photo essay for the NYT is a testament to the power of creatively combining visuals with text. Here, photographs of Smith atop a bike are far from simply ornamental. They’re integral to the ruminative mood of the essay, as essential as the writing. Though Smith places his work at the crosscurrents of various aesthetic influences (such as the painter Edward Hopper), what stands out the most in this taciturn, thoughtful piece of writing is his use of the second person to address the reader directly. Suddenly, the writer steps out of the body of the essay and makes eye contact with the reader. The reader is now part of the story as a second character, finally entering the picture.

Short Fiction

The short story is the happy medium of fiction writing. These bite-sized narratives can be devoured in a single sitting and still leave you reeling. Sometimes viewed as a stepping stone to novel writing, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Short story writing is an art all its own. The limited length means every word counts and there’s no better way to see that than with these two examples:

“An MFA Story” by Paul Dalla Rosa (Electric Literature)

At Starbucks, I remembered a reading Zhen had given, a reading organized by the program’s faculty. I had not wanted to go but did. In the bar, he read, "I wrote this in a Starbucks in Shanghai. On the bank of the Huangpu." It wasn’t an aside or introduction. It was two lines of the poem. I was in a Starbucks and I wasn’t writing any poems. I wasn’t writing anything.

This short story is a delightfully metafictional tale about the struggles of being a writer in New York. From paying the bills to facing criticism in a writing workshop and envying more productive writers, Paul Dalla Rosa’s story is a clever satire of the tribulations involved in the writing profession, and all the contradictions embodied by systemic creativity (as famously laid out in Mark McGurl’s The Program Era ). What’s more, this story is an excellent example of something that often happens in creative writing: a writer casting light on the private thoughts or moments of doubt we don’t admit to or openly talk about.

“Flowering Walrus” by Scott Skinner (Reedsy)

I tell him they’d been there a month at least, and he looks concerned. He has my tongue on a tissue paper and is gripping its sides with his pointer and thumb. My tongue has never spent much time outside of my mouth, and I imagine it as a walrus basking in the rays of the dental light. My walrus is not well.

A winner of Reedsy’s weekly Prompts writing contest, ‘ Flowering Walrus ’ is a story that balances the trivial and the serious well. In the pauses between its excellent, natural dialogue , the story manages to scatter the fear and sadness of bad medical news, as the protagonist hides his worries from his wife and daughter. Rich in subtext, these silences grow and resonate with the readers.

Want to give short story writing a go? Give our free course a go!

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

Perhaps the thing that first comes to mind when talking about creative writing, novels are a form of fiction that many people know and love but writers sometimes find intimidating. The good news is that novels are nothing but one word put after another, like any other piece of writing, but expanded and put into a flowing narrative. Piece of cake, right?

To get an idea of the format’s breadth of scope, take a look at these two (very different) satirical novels:

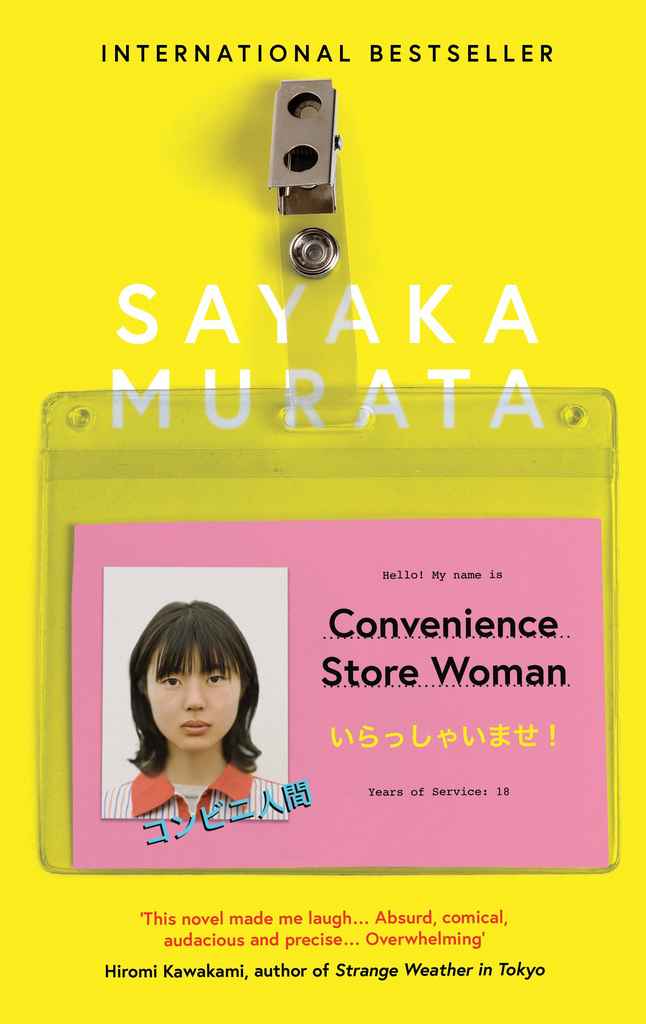

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

I wished I was back in the convenience store where I was valued as a working member of staff and things weren’t as complicated as this. Once we donned our uniforms, we were all equals regardless of gender, age, or nationality — all simply store workers.

Keiko, a thirty-six-year-old convenience store employee, finds comfort and happiness in the strict, uneventful routine of the shop’s daily operations. A funny, satirical, but simultaneously unnerving examination of the social structures we take for granted, Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman is deeply original and lingers with the reader long after they’ve put it down.

Erasure by Percival Everett

The hard, gritty truth of the matter is that I hardly ever think about race. Those times when I did think about it a lot I did so because of my guilt for not thinking about it.

Erasure is a truly accomplished satire of the publishing industry’s tendency to essentialize African American authors and their writing. Everett’s protagonist is a writer whose work doesn’t fit with what publishers expect from him — work that describes the “African American experience” — so he writes a parody novel about life in the ghetto. The publishers go crazy for it and, to the protagonist’s horror, it becomes the next big thing. This sophisticated novel is both ironic and tender, leaving its readers with much food for thought.

Creative Nonfiction

Creative nonfiction is pretty broad: it applies to anything that does not claim to be fictional (although the rise of autofiction has definitely blurred the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction). It encompasses everything from personal essays and memoirs to humor writing, and they range in length from blog posts to full-length books. The defining characteristic of this massive genre is that it takes the world or the author’s experience and turns it into a narrative that a reader can follow along with.

Here, we want to focus on novel-length works that dig deep into their respective topics. While very different, these two examples truly show the breadth and depth of possibility of creative nonfiction:

Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward

Men’s bodies litter my family history. The pain of the women they left behind pulls them from the beyond, makes them appear as ghosts. In death, they transcend the circumstances of this place that I love and hate all at once and become supernatural.

Writer Jesmyn Ward recounts the deaths of five men from her rural Mississippi community in as many years. In her award-winning memoir , she delves into the lives of the friends and family she lost and tries to find some sense among the tragedy. Working backwards across five years, she questions why this had to happen over and over again, and slowly unveils the long history of racism and poverty that rules rural Black communities. Moving and emotionally raw, Men We Reaped is an indictment of a cruel system and the story of a woman's grief and rage as she tries to navigate it.

Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker

He believed that wine could reshape someone’s life. That’s why he preferred buying bottles to splurging on sweaters. Sweaters were things. Bottles of wine, said Morgan, “are ways that my humanity will be changed.”

In this work of immersive journalism , Bianca Bosker leaves behind her life as a tech journalist to explore the world of wine. Becoming a “cork dork” takes her everywhere from New York’s most refined restaurants to science labs while she learns what it takes to be a sommelier and a true wine obsessive. This funny and entertaining trip through the past and present of wine-making and tasting is sure to leave you better informed and wishing you, too, could leave your life behind for one devoted to wine.

Illustrated Narratives (Comics, graphic novels)

Once relegated to the “funny pages”, the past forty years of comics history have proven it to be a serious medium. Comics have transformed from the early days of Jack Kirby’s superheroes into a medium where almost every genre is represented. Humorous one-shots in the Sunday papers stand alongside illustrated memoirs, horror, fantasy, and just about anything else you can imagine. This type of visual storytelling lets the writer and artist get creative with perspective, tone, and so much more. For two very different, though equally entertaining, examples, check these out:

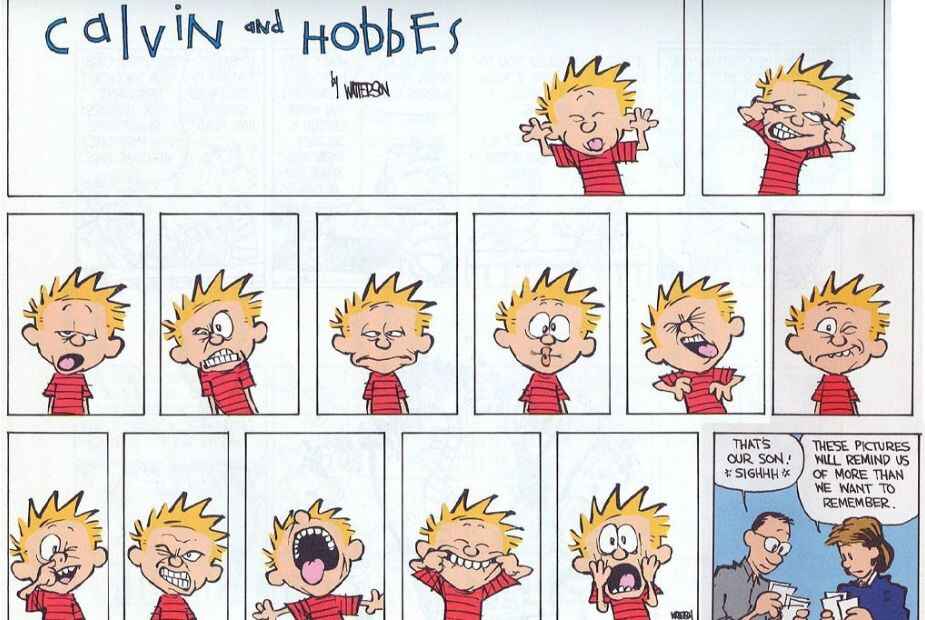

Calvin & Hobbes by Bill Watterson

"Life is like topography, Hobbes. There are summits of happiness and success, flat stretches of boring routine and valleys of frustration and failure."

This beloved comic strip follows Calvin, a rambunctious six-year-old boy, and his stuffed tiger/imaginary friend, Hobbes. They get into all kinds of hijinks at school and at home, and muse on the world in the way only a six-year-old and an anthropomorphic tiger can. As laugh-out-loud funny as it is, Calvin & Hobbes ’ popularity persists as much for its whimsy as its use of humor to comment on life, childhood, adulthood, and everything in between.

From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell

"I shall tell you where we are. We're in the most extreme and utter region of the human mind. A dim, subconscious underworld. A radiant abyss where men meet themselves. Hell, Netley. We're in Hell."

Comics aren't just the realm of superheroes and one-joke strips, as Alan Moore proves in this serialized graphic novel released between 1989 and 1998. A meticulously researched alternative history of Victorian London’s Ripper killings, this macabre story pulls no punches. Fact and fiction blend into a world where the Royal Family is involved in a dark conspiracy and Freemasons lurk on the sidelines. It’s a surreal mad-cap adventure that’s unsettling in the best way possible.

Video Games and RPGs

Probably the least expected entry on this list, we thought that video games and RPGs also deserved a mention — and some well-earned recognition for the intricate storytelling that goes into creating them.

Essentially gamified adventure stories, without attention to plot, characters, and a narrative arc, these games would lose a lot of their charm, so let’s look at two examples where the creative writing really shines through:

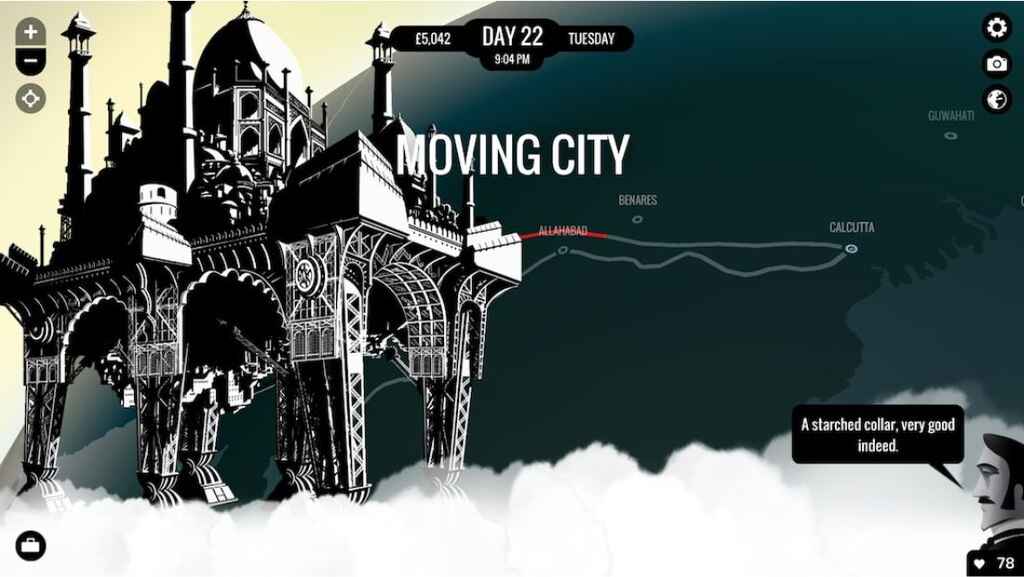

80 Days by inkle studios

"It was a triumph of invention over nature, and will almost certainly disappear into the dust once more in the next fifty years."

Named Time Magazine ’s game of the year in 2014, this narrative adventure is based on Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne. The player is cast as the novel’s narrator, Passpartout, and tasked with circumnavigating the globe in service of their employer, Phileas Fogg. Set in an alternate steampunk Victorian era, the game uses its globe-trotting to comment on the colonialist fantasies inherent in the original novel and its time period. On a storytelling level, the choose-your-own-adventure style means no two players’ journeys will be the same. This innovative approach to a classic novel shows the potential of video games as a storytelling medium, truly making the player part of the story.

What Remains of Edith Finch by Giant Sparrow

"If we lived forever, maybe we'd have time to understand things. But as it is, I think the best we can do is try to open our eyes, and appreciate how strange and brief all of this is."

This video game casts the player as 17-year-old Edith Finch. Returning to her family’s home on an island in the Pacific northwest, Edith explores the vast house and tries to figure out why she’s the only one of her family left alive. The story of each family member is revealed as you make your way through the house, slowly unpacking the tragic fate of the Finches. Eerie and immersive, this first-person exploration game uses the medium to tell a series of truly unique tales.

Fun and breezy on the surface, humor is often recognized as one of the trickiest forms of creative writing. After all, while you can see the artistic value in a piece of prose that you don’t necessarily enjoy, if a joke isn’t funny, you could say that it’s objectively failed.

With that said, it’s far from an impossible task, and many have succeeded in bringing smiles to their readers’ faces through their writing. Here are two examples:

‘How You Hope Your Extended Family Will React When You Explain Your Job to Them’ by Mike Lacher (McSweeney’s Internet Tendency)

“Is it true you don’t have desks?” your grandmother will ask. You will nod again and crack open a can of Country Time Lemonade. “My stars,” she will say, “it must be so wonderful to not have a traditional office and instead share a bistro-esque coworking space.”

Satire and parody make up a whole subgenre of creative writing, and websites like McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and The Onion consistently hit the mark with their parodies of magazine publishing and news media. This particular example finds humor in the divide between traditional family expectations and contemporary, ‘trendy’ work cultures. Playing on the inherent silliness of today’s tech-forward middle-class jobs, this witty piece imagines a scenario where the writer’s family fully understands what they do — and are enthralled to hear more. “‘Now is it true,’ your uncle will whisper, ‘that you’ve got a potential investment from one of the founders of I Can Haz Cheezburger?’”

‘Not a Foodie’ by Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell (Electric Literature)

I’m not a foodie, I never have been, and I know, in my heart, I never will be.

Highlighting what she sees as an unbearable social obsession with food , in this comic Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell takes a hilarious stand against the importance of food. From the writer’s courageous thesis (“I think there are more exciting things to talk about, and focus on in life, than what’s for dinner”) to the amusing appearance of family members and the narrator’s partner, ‘Not a Foodie’ demonstrates that even a seemingly mundane pet peeve can be approached creatively — and even reveal something profound about life.

We hope this list inspires you with your own writing. If there’s one thing you take away from this post, let it be that there is no limit to what you can write about or how you can write about it.

In the next part of this guide, we'll drill down into the fascinating world of creative nonfiction.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We made a writing app for you

Yes, you! Write. Format. Export for ebook and print. 100% free, always.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Home › Study Tips › Creative Writing Resources For Secondary School Students

Creative Writing Examples: 9 Types Of Creative Writing

- Published July 28, 2022

Table of Contents

Creative writing takes a lot of brainpower. You want to improve your creative writing skills, but you feel stuck. And nothing’s worse than feeling dry and wrung out of ideas!

But don’t worry. When our creative writing summer school students feel they’re in a rut, they expand their horizons. Because sometimes, all you need is to try something new .

And this article will give you a glimpse into what you need to thrive at creative writing.

Here you’ll find creative writing examples to help give you the creative boost you’re looking for. Are you dreaming of writing a novel but can’t quite get there yet?

No worries! Maybe you’d want to try your hand writing short stories first, or maybe flash fiction. You’ll know more about these in the coming sections.

9 Scintillating Creative Writing Examples

Let’s go through the 9 examples of creative writing and some of their famous pieces penned under each type.

There is hardly a 21st-century teenager who hasn’t laid their hands on a novel or two. A novel is one of the most well-loved examples of creative writing.

It’s a fictional story in prose form found in various genres, including romance, horror, Sci-Fi, Fantasy and contemporary. Novels revolve around characters whose perspectives in life change as they grow through the story. They contain an average of 50,000 to 70,000 words.

Here are some of the most famous novels:

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- Harry Potter by J.K. Rowling

- The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis

- Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

2. Flash Fiction

Flash Fiction is similar to a novel in that it offers plot development and characters. But unlike novels, it’s less than 1000 words. Some even contain fewer than 100 words! Legend has it that the shortest story ever told was Ernest Hemmingway’s six-word story, which goes like this, “For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn.”

Do you know that there are sub-categories of Flash Fiction? There’s the “Sudden Fiction” with a maximum of 750 words. “Microfiction” has 100 words at most. And the “six-word story” contains a single-digit word count.

Remarkable Flash Fiction include:

- The Long and Short of It by Michael A. Arnzen

- Chapter V Ernest Hemingway

- Gasp by Michael A. Arnzen

- Angels and Blueberries by Tara Campbell

- Curriculum by Sejal Shah

3. Short Story

What’s shorter than a novel but longer than flash fiction? Short story. It’s a brief work of fiction that contains anywhere from 1,000 to 10,000 words. Whereas a novel includes a complex plot, often with several characters interacting with each other, a short story focuses on a single significant event or mood. It also has fewer characters.

The best short stories are memorable and evoke strong emotions. They also contain a twist or some type of unexpected resolution.

Check out these famous short stories:

- The Lottery by Shirley Jackson

- The Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allan Poe

- The Gift of the Magi by O. Henry

- The Sniper by Liam OFlaherty

- A Good Man is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor

4. Personal Essay

In a personal essay, you write about your personal experience. What lesson did the experience teach you? And how does it relate to the overarching theme of the essay? Themes can be about anything! From philosophical questions, political realizations, historical discussions, you name it.

Since writing a personal essay involves talking about actual personal events, it’s often called “autobiographical nonfiction.” Its tone is informal and conversational.

Have you observed that applications at universities and companies usually involve submitting personal essays? That’s because having the capability to write clear essays displays your communication and critical thinking skills.

Some of the most famous personal essays include:

- Self-Reliance by Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Once More To The Lake by E.B. White

- What I Think and Feel at 25 by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Ticket to the Fair by David Foster Wallace

Memoirs and personal essays are autobiographical. But while you use your experiences in a personal essay to share your thoughts about a given theme, a memoir focuses on your life story. What past events do you want to share? And how has your life changed?

In a word, a memoir is all about self-exploration.

Here are among the most famous memoirs:

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- West with the Night by Beryl Markham

- Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant by Ulysses Grant

- Night By Elie Wiesel

- A Long Way Gone By Ishmael Beah

6. Poetry

Poetry is one of the oldest examples and types of creative writing . Did you know that the oldest poem in the world is the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is known to be 4,000 years old? Poetry is a type of literature that uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language—such as sound, imagery, and metaphor—to evoke meaning.

There are 5 types of rhythmic feet common in poetry: trochee, anapest, dactyl, iamb, and anapest.

The most beloved poems include:

- No Man Is An Island by John Donne

- Still I Rise by Maya Angelou

- Ode to a Nightingale by John Keats

- If You Forget Me by Pablo Neruda

- Fire And Ice by Robert Frost

7. Script (Screenplay)

A script is a type of creative writing (a.k.a. screenwriting) that contains instructions for movies. Instructions indicate the characters’ movements, expressions, and dialogues. In essence, the writer is giving a visual representation of the story.

When a novel says , “Lucy aches for the love she lost,” a script must show . What is the actress of Lucy doing? How can she portray that she is aching for her lost love? All these must be included in screenwriting.

The following are some of the most brilliant scripts:

- Citizen Kane by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles

- The Godfather by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola

- Pulp Fiction by Quentin Tarantino

- The Silence of the Lambs by Ted Tally

- Taxi Driver by Paul Schrader

8. Play (Stageplay)

If screenplay is for movies, stageplay is for live theatre. Here’s another distinction. A screenplay tells a story through pictures and dialogues, whereas a stageplay relies on the actors’ performances to bring the story to life.

That’s why dialogue is THE centre of live performance. A play doesn’t have the benefit of using camera angles and special effects to “show, don’t tell.”

Some of the most renowned plays are:

- Hamlet by William Shakespeare

- The Crucible by Arthur Miller

- A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams

- Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

- The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

What was the best speech you heard that moved you to action? Speeches are among the most powerful examples of creative writing. It’s meant to stir the audience and persuade them to think and feel as you do about a particular topic.

When you write a speech, you intend to present it orally. So not only do you have to consider the words you choose and the phrasing. But you also have to think about how you’ll deliver it.

Will the sentences flow smoothly onto each other so as to roll off the tongue? Do the words give you the confidence and conviction you need to express your thoughts and beliefs?

Here are some of the most stirring speeches in history:

- I Have A Dream by Martin Luther King Jr.

- The Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln

- First Inaugural Address by Franklin D. Roosevelt

- I Choose To Live by Sabine Herold

- Address to the Nation on the Challenger by Ronald Reagan

What Are The Elements of Creative Writing?

You’re now familiar with the various examples of creative writing. Notice how creative writing examples fall under different categories. Can you guess what they are? That’s right! Poetry and Prose .

The Prose section can be broken down further into Prose Fiction and Prose Nonfiction.

Where do the Elements of Creative Writing come in? For Prose fiction . If there’s one word that can describe all forms of prose fiction, it’s STORY. So what are the Elements of a Story (Creative Writing?)

The character is a being (person, animal, thing) through which the reader experiences the story. They speak, act, and interact with the environment and other characters.

- Elizabeth Bennet in Pride & Prejudice

- Simba in Lion King

- Woody in Toy Story

The two most essential types of characters are the Protagonist and Antagonist. Who is the Protagonist? They’re the main character, and the story revolves around them. Elizabeth, Simba, and Woody are the protagonists in their stories.

And who is the Antagonist? The one who causes conflict for the protagonist.

The setting answers the question, “when and where does the story set place?” It’s the story’s time and location. Providing context that helps the reader visualise the events in clearer detail.

What is the Plot? It’s the sequence of events in the story. If you break it down, the plot looks like this:

Exposition – you can also call this the introduction. Where you first catch a glimpse of the characters and setting. In the Lion King (Part 1), this is where Simba is introduced to all the animals on top of Pride Rock as the future King.

Rising Action – the story gets complicated. The tension builds, and you see the conflict arise. It’s a time of crisis for the main characters. So what’s the Rising Action for Lion King? It would be when Simba’s uncle Scar murders his father and tells him to “Run away and NEVER return.”

Climax – you’re at the edge of your seat as the story reaches its crescendo. The most defining (and intense) moment arrives when the protagonist faces the conflict (enemy/challenge) head-on. Simba finally goes back to Pride Rock to confront his wicked uncle Scar. And an epic fight begins. Simba even almost falls off a cliff! *gasp

Falling Action – here you catch your breath as the story starts to calm down. The characters unwind and work towards their respective conclusions. Simba didn’t fall off the cliff. Instead, he won the fight. And he roars atop Pride Rock to reclaim his rightful place as King. The lionesses proclaim their joyful acceptance by roaring back.

Resolution – remaining conflict concludes, and the story ends. In Lion King, Pride Land is once again lush and peaceful. And Simba looks on with pride as he introduces his daughter Kiara on top of Pride Rock.

You can think of the theme as the main idea. What meaning is the writer trying to express in the story? The other elements, such as setting, plot, and characters, work together to convey the theme.

Point of View

Through what lens or “eye” does the narrating voice tell the story? There are three points of view common in writing stories:

First Person

In the first person point of view, the narrating voice is the main character. Much of the lines talk of “I” and “me.” Everything you know about the other characters, places, and dialogues in the story comes from the main character’s perspective.

Third Person

From the third person point of view, the narrating voice is separate from the main character. Meaning the narrator uses “he/she/they” when following the main character in the story. There are generally two types of third-person points of view.

Limited. In a third-person limited point of view, the narrator only knows about the main character’s inner world – their thoughts and feelings. But they have no idea about the thoughts and feelings of other characters.

Omniscient. What does “omniscient” mean? All-knowing. So in the Third Person Omniscient point of view, the narrator knows about the feelings and thoughts of all the characters. Not just that of the main character.

In a story that uses a third-person omniscient point of view, the all-knowing narrator sometimes follows the story from multiple characters’ perspectives.

There you have it! By now, you’ve learned about creative writing examples, plus creative elements should you want to write a story. Browse our creative writing tips if you’re looking for a bit of help to engage your audience.

Still feel like you need more heavy-lifting? If it’s a talented Oxford, Cambridge, or Ivy League tutor you need to help you master creative writing, check out these creative writing online courses .

Related Content

Tackling homework anxiety: your guide to a calmer study life.

Discovery: The Ultimate Guide to Creative Writing

Friday 4th, March 2016

Elyse Popplewell

If you’re a first time reader, then you might not be aware of my free online HSC tutoring for English (including HSC creative writing), and other subjects. Check it out! Also – I have a deal for you. If this post is crazy helpful, then you should share it with your friends on Facebook . Deal? Awesome.

HSC Creative Writing: The Guide.

HSC creative writing can be a pain for some and the time to shine for others. Getting started is the most difficult part. When you have something to work with, it is simply a matter of moulding it to perfection. When you have nothing, you have a seemingly difficult road ahead. After several ATAR Notes members expressed that they need help with HSC creative writing, I wrote this to give you some starting points. Then I edited this, and re-wrote it so that it helps you from the beginning stages until the very last days of editing. Fear no more, HSC creative writing doesn’t have to be the foe that it is in your head! Let’s get started.

Surprise: You’re the composer!

Write about what you know

In the years 2010-2015, not once has Paper 1 specified a form that you have to use. Every year in that time frame they have asked for “imaginative writing” except in 2011 when they asked for a “creative piece” of writing. Most commonly, students write in the short story form. However, students can also write speeches, opinion articles, memoirs, monologues, letters, diary entries, or hybrid medium forms. Think about how you can play to your strengths. Are you the more analytical type and less creative? Consider using that strength in the “imaginative writing” by opting to write a feature article or a speech. If you want to ask questions about your form, then please check out my free online HSC tutoring for English and other subjects.

Tense is a very powerful tool that you can use in your writing to increase intensity or create a tone of detachment, amongst other things. Writing entirely in the present tense is not as easy as it seems, it is very easy to fall into past tense. The present tense creates a sense of immediacy, a sense of urgency. If you’re writing with suspense or about action, consider the present tense.

“We stand here together, linking arms. The car screeches to a stop in front of our unified bodies. The frail man alights from the vehicle and stares into my eyes.”

The past tense is the most common in short stories. The past tense can be reflective, recounting, or perhaps just the most natural tense to write in.

“We stood together, linking arms. The car screeched to a stop in front of us. The frail man alighted from his vehicle and stared into my eyes.”

The future tense is difficult to use for short stories. However, you can really manipulate the future tense to work in your favour if you are writing a creative speech. A combination of tenses will most probably create a seamless link between cause and effect in a speech.

“We will stand together with our arms linked. The man may intimidate us all he likes, but together, when we are unified, we are stronger he will ever be.”

It is also important to point out that using a variety of tenses may work best for your creative. If you are flashing back, the easiest way to do that is to establish the tense firmly.

Giving your setting some texture

You ultimately want your creative writing to take your marker to a new place, a new world, and you want them to feel as though they understand it like they would their own kitchen. The most skilled writers can make places like Hogwarts seem like your literary home. At the Year 12 level, we aren’t all at that level. The best option is to take a setting you know and describe it in every sense – taste, smell, feel, sound and sight.

Choose a place special and known to you. Does your grandmother’s kitchen have those old school two-tone brown tiles? Did you grow up in another country, where the air felt different and the smell of tomatoes reminded you of Sundays? Does your bedroom have patterned fabric hanging from the walls and a bleached patch on the floor from when you spilled nail polish remover? Perhaps your scene is a sporting field – describe the grazed knees, the sliced oranges and the mums on the sideline nursing babies. The more unique yet well described the details are, the more tangible your setting is.

Again, it comes back to: write about what you know.

How much time has elapsed?

You want to consider whether your creative piece is focused on a small slot of ordinary time, or is it covering years in span? Are you flashing back between the past and the present? Some of the most wonderful short stories focus on the minutiae that is unique to ordinary life but is perpetually overlooked or underappreciated. By this I mean, discovering that new isn’t always better may be the product of a character cooking their grandmother’s recipe for brownies (imagine the imagery you could use!). Discovering that humans are all one and the same could come from a story based on one single shift at a grocery store, observing customers. Every day occurrences offer very special and overlooked discoveries.

You could create a creative piece that actually spans the entire life span of someone (is this the life span of someone who lived to 13 years old or someone who lived until 90 years old?). Else, you could create a story that compares the same stage of life of three different individuals in three different eras. Consider how much time you want to cover before embarking on your creative journey.

Show, don’t tell:

The best writers don’t give every little detail wrapped up and packaged, ready to go. As a writer, you need to have respect for your reader in that you believe in their ability to read between the lines at points, or their ability to read a description and visualise it appropriately.

“I was 14 at the time. I was young, vulnerable and naïve. At 14 you have such little life experience, so I didn’t know how to react.”

This is boring because the reader is being fed every detail that they could have synthesised from being told the age alone. To add to the point of the age, you could add an adjective that gives connotations to everything that was written in the sentence, such as “tender age of 14.” That’s a discretionary thing, because it’s not necessary. When you don’t have to use extra words: probably don’t. When you give less information, you intrigue the reader. There is a fine line between withholding too much and giving the reader the appropriate rope for them to pull. The best way to work out if you’re sitting comfortably on the line is to send your creative writing to someone, and have them tell you if there was a gap in the information. How many facts can you convey without telling the reader directly? Your markers are smart people, they can do the work on their end, you just have to feed them the essentials.

Here are some examples of the difference between showing and telling.

Telling: The beach was windy and the weather was hot. Showing: Hot sand bit my ankles as I stood on the shore.

Telling: His uniform was bleakly coloured with a grey lapel. He stood at attention, without any trace of a smile. Showing: The discipline of his emotions was reflected in his prim uniform.

Giving your character/persona depth

If your creative writing involves a character – whether that be a protagonist or the persona delivering your imaginative speech – you need to give them qualities beyond the page. It isn’t enough to describe their hair colour and gender. There needs to be something unique about this character that makes them feel real, alive and possibly relatable. Is it the way that they fiddle with loose threads on their cardigan? Is it the way they comb their hair through their fingers when they are stressed? Do they wear an eye patch? Do they have painted nails, but the pinky nail is always painted a different colour? Do they have an upward infliction when they are excited? Do the other characters change their tone when they are in the presence of this one character? Does this character only speak in high/low modality? Are they a pessimist? Do they wear hand-made ugly brooches?

Of course, it is a combination of many qualities that make a character live beyond the ink on the page. Hopefully my suggestions give you an idea of a quirk your character could have. Alternatively, you could have a character that is so intensely normal that they are a complete contrast to their vibrant setting?

Word Count?

Mine was 1300. I am a very fast writer in exam situations. Length does not necessarily mean quality, of course. A peer of mine wrote 900 words and got the same mark as me. For your first draft, I would aim for a minimum of 700 words. Then, when you create a gauge for how much you can write in an exam in legible handwriting, you can expand. For your half yearly, I definitely recommend against writing a 1300 word creative writing unless you are supremely confident that you can do that, at high quality, in 40 minutes (perhaps your half yearly exam isn’t a full Paper 1 – in which case you need to write to the conditions).

There is no correct word count range. You need to decide how many words you need to effectively and creatively express your ideas about discovery.

Relating to a stimulus

Since 2010, Paper 1 has delivered quotes to be used as the first sentence, general quotes to be featured anywhere in the text and visual images to be incorporated. Every year, there has been a twist on the area of study concept (belonging or discovery) in the question. In the belonging stage, BOSTES did not say “Write a creative piece about belonging. Include the stimulus ******.” Instead, they have said to write an imaginative piece about “belonging and not belonging” or to “Compose a piece of imaginative writing which explores the unexpected impact of discovery.” These little twists always come from the rubric, so there isn’t really any excuse to not be prepared for that!

If the stimulus is a quote such as “She was always so beautiful” there is lenience for tense. Using the quote directly, if required to do that, is the best option. However, if this screws up the tense you are writing in, it is okay to say “she is always so beautiful.” (Side note: This would be a really weird stimulus if it ever occurred.) Futhermore, gender can be substituted, although also undesirable. If the quote is specified to be the very first sentence of your work: there is no lenience. It must be the very first sentence.

As for a visual image, the level of incorporation changes. Depending on the image, you could reference the colours, the facial expressions, the swirly pattern or the salient image. Unfortunately, several stimuli from past papers are “awaiting copyright” online and aren’t available. However, there are a few, and when you have an imaginative piece you should try relate them to these stimuli as preparation.

The techniques:

Don’t forget to include some techniques in there. You study texts all year and you know what makes a text stand out. You know how a metaphor works, so use it. Be creative. Use a motif that flows through your story. If you’re writing a speech, use imperatives to call your reader to action. Use beautiful imagery that intrigues a reader. Use amazing alliteration (see what I did there). Avoid clichés like the plague (again…see what I did) unless you are effectively appropriating it. In HSC creative writing, you need to show that you have studied magnificent wordsmiths, and in turn, you can emulate their manipulation of form and language.

Some quirky prompts:

Click here if you want 50 quirky writing prompts – look for the spoiler in the post!

How do I incorporate Discovery?

If you click here you will be taken to an AOS rubric break down I have done with some particular prompts for HSC creative writing.

Part two: Editing and Beyond!

This next part is useful for your HSC creative writing when you have some words on the page waiting for improvement.

Once you’ve got a creative piece – or at least a plot – you can start working on how you will present this work in the most effective manner. You need to be equipped with knowledge and skill to refine your work on a technical level, in order to enhance the discovery that you will be heavily marked on. By synthesising the works of various genius writers and the experiences of HSC writers, I’ve compiled a list of checks and balances, tips and tricks, spells and potions, that will help you create the best piece of HSC creative writing that you can.

Why should you critique your writing and when?

What seems to be a brilliant piece of HSC creative writing when you’re cramming for exams may not continue to be so brilliant when you’re looking at it again after a solid sleep and in the day light. No doubt what you wrote will have merit, perhaps it will be perfect, but the chances lean towards it having room for improvement. You can have teachers look at your writing, peers, family, and even me here at ATAR Notes. Everyone can give their input and often, an outsider’s opinion is preciously valuable. However, at the end of the day this is your writing and essentially an artistic body that you created from nothing. That’s special. It is something to be proud of, and when you find and edit the faults in your own work, you enhance your writing but also gain skills in editing.

Your work should be critiqued periodically from the first draft until the HSC exams. After each hand-in of your work to your teacher you should receive feedback to take on board. You have your entire year 12 course to work on a killer creative writing piece. What is important is that you are willing to shave away the crusty edges of the cake so that you can present it in the most effective and smooth icing you have to offer. If you are sitting on a creative at about 8/15 marks right now (as of the 29/02/2016), you only have to gain one more mark per month in order to sit on a 15/15 creative. This means that you shouldn’t put your creative to bed for weeks without a second thought. This is the kind of work that benefits from small spontaneous bursts of editing, reading and adjusting. Fresh eyes do wonders to writer’s block, I promise. You will also find that adapting your creative writing to different stimuli is also very effective in highlighting strengths and flaws in the work. This is another call for editing! Sometimes you will need to make big changes, entirely re-arranging the plot, removing characters, changing the tense, etc. Sometimes you will need to make smaller changes like finely grooming the grammar and spelling. It is worth it when you have an HSC creative writing piece that works for you, and is effective in various situations that an exam could give you.

The way punctuation affects things:

I’ll just leave this right here…

Consistency of tense:

Are your sentences a little intense?

It is very exhausting for a responder to read complex and compound sentences one after the other, each full of verbose and unnecessary adjectives. It is such a blessed relief when you reach a simple sentence that you just want to sit and mellow in the beauty of its simplicity. Of course, this is a technique that you can use to your advantage. You won’t need the enormous unnecessary sentences though, I promise. “Jesus wept.” This is the shortest verse in the Bible (found John 11:35) and is probably one of the most potent examples of the power of simplicity. The sentence only involves a proper noun and a past-tense verb. It stands alone to be very powerful. It also stands as a formidable force in among other sentences. Sentence variation is extremely important in engaging a reader through flow.

Of course, writing completely in simple sentences is tedious for you and the reader. Variation is the key in HSC creative writing. This is most crucial in your introduction because there is opportunity to lose your marker before you have even shown what you’re made of! Reading your work out loud is one of the most effective ways to realise which sentences aren’t flowing. If you are running out of breath before you finish a sentence – you need to cut back. Have a look here and read this out loud:

The grand opening:

Writer’s Digest suggested in their online article “5 Wrong Ways to Start a Story” that there are in fact, ways to lose your reader and textual credibility before you even warm up. It is fairly disappointing to a reader to be thrown into drastic action, only to be pulled into consciousness and be told that the text’s persona was in a dream. My HSC English teacher cringed at the thought of us starting or resolving our stories with a dream that defeats everything that happened thus far. It is the ending you throw on when you don’t know how to end it, and it is the beginning you use to fake that you are a thrilling action writer. Exactly what you don’t want to do in HSC creative writing.

Hopefully neither of these apply to you – so when Johnny wakes up to realise “it was all just a dream” you better start hitting the backspace.Students often turn to writing about their own experiences. This is great! However, do not open your story with the alarm clock buzzing, even if that is the most familiar daily occurrence. Writer’s Digest agrees. They say, “the only thing worse than a story opening with a ringing alarm clock is when the character reaches over to turn it off and then exclaims, “I’m late.””So, what constitutes a good opening? If you are transporting a reader to a different landscape or time period than what they are probably used to, you want to give them the passport in the very introduction otherwise the plane to the discovery will leave without them. This is your chance to grab the marker and keep them keen for every coming word. Of course, to invite a reader to an unfamiliar place you need to give them some descriptions. This is the trap of death! Describing the location in every way is tedious and boring. You want to respect the reader and their imagination. Give them a rope, they’ll pull.However, if your story is set in a familiar world, you may need to take a different approach. These are some of my favourite first lines from books (some I have read, some I haven’t). I’m sure you can appreciate why each one is so intriguing.

“Call me Ishmael.” -Herman Melville, Moby Dick.

This works because it is simple, stark, demanding. Most of all, it is intriguing.

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” – George Orwell, 1984.

Usually, bright and sunny go together. Here, bright and cold are paired. What is even more unique? The clocks tick beyond 12. What? Why? How? You will find out if you read on! See how that works?

“It was a pleasure to burn.” Ray Bradbury, Farenheit 451.

This is grimacing, simple, intriguing.

“I write this sitting in the kitchen sink.” -Dodie Smith, I Capture the Castle.

Already I’m wondering why the bloody hell is this person in a kitchen sink? How did they get there? Are they squashed? This kind of unique sentence stands out.

“In case you hadn’t noticed, you have a mental dialogue going on inside your head that never stops. It just keeps going and going. Have you ever wondered why it talks in there? How does it decide what to say and when to say it?” – Michael A Singer, The Untethered Soul: The Journal Beyond Yourself.

This works because it appeals to the reader and makes them question a truth about themselves that they may have never considered before.

“Mr and Mrs Dursley, of number four Pivet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.” JK Rowling, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

Who was questioning that they weren’t perfectly normal? Why are they so defensive and dismissive? I already feel a reaction to the pompous nature of the pair!

Resolving the story well!

There are so many ways to end stories. SO many. What stories have ended in a very efficient way for you? Which stories left you wanting more? Which stories let you down?

Because you are asked to write about discovery in HSC creative writing, you want the ending to be wholesome. This means, you need your marker to know that the ending justifies the discovery. You can’t leave your marker confused about whether or not the discovery had yet occurred because this may jeopardise your marks. If your discovery is an epiphany for the reader, you may want to finish with a stark, stand alone sentence that truly has a resonating effect. If your story is organised in a way that the discovery is transformative of a persona’s opinions, make sure that the ending clearly justifies the transformation that occurred. You could find it most effective to end your story with your main character musing over the happenings of the story.

In the pressure of an exam, it is tempting to cut short on your conclusion to save time. However, you MUST remember that the last taste of your story that your marker has comes from the final words. They simply cannot be compromised!

George Orwell’s wise words:

Looking for a bit of extra help?

We also have a free HSC creative writing marking thread here!

Don’t be shy, post your questions. If you have a question on HSC creative writing or anything else, it is guaranteed that so many other students do too. So when you post it on here, not only does another student benefit from the reply, but they also feel comforted that they weren’t the only one with the question!

You must be logged in to leave a comment

No comments yet…

What does it actually mean to “study smart”?

How to study in high school - the 'dos' and 'don'ts'

Spare 5 minutes? Here are 7 quick study strategies

How to get more out of your textbook

The benefit of asking questions in high school

Your Year 12 study questions answered!

Sponsored by the Victorian Government - Department of Education

Early childhood education: a career that makes a difference

Early childhood education is seeing growth like no other profession – creating thousands of jobs available over the decade. With financial support to study at university and Free TAFE courses available, there’s never been a better time to become a kinder teacher or educator.