Virtual Lab School

Installation staff login.

- Reset your password

Social Emotional Learning for Teachers: An Introduction

Your ability to manage stress and to take care of your own social-emotional health influences your ability to model appropriate emotional expression, to build and maintain effective interpersonal relationships, and to support productive social skills for children. This course introduces the concept of resilience and offers strategies you can use to promote and sustain your emotional and physical health. As you move through the course, identify strategies that work well for you and try others that have the potential to be a good fit. Like most things in life, regular practice will equip you with helpful skills for growth.

- Reflect on challenges that affect your work as an early-childhood teacher or caregiver.

- Understand the links between stress and physical health and emotional wellness.

- Define resilience and identify its importance in promoting health and well-being.

- Discuss the brain’s role in managing stress and fostering resilience.

Take a moment to think about your work with young children and youth. What are some of the emotions that you feel? Do you feel energized and resourceful, or maybe frustrated and overwhelmed by some of what you face?

Teaching and caring for young children is important work. Teachers shape the tone of the classroom, model kindness and problem solving, and help children learn to manage emotions and gain the social skills needed to form healthy relationships.

Teaching and caring for young children is also emotionally demanding work. Classrooms provide opportunities for joy and laughter, but they also involve responding to children’s negative emotions, managing relationships between children and with parents, and dealing with the need to be constantly “on” and vigilant when it comes to children’s safety and learning. Many early-childhood teachers report feeling stressed, and some report feelings of depression.

It is not surprising that researchers find that, beyond education and professional development training, there is a link between teachers’ social-emotional well-being and the development of children in their care. Researchers also have found links between teachers’ coping strategies—how they manage stress—and job burnout.

Thus, as a teacher and caregiver, you have two powerful reasons for taking care of yourself: It makes a difference to your own physical and mental well-being, and it makes a difference for the children in your classroom.

One way to think about strategies for attending to your social-emotional health is to divide these strategies into two categories: practices that are preventive and those that are helpful in situations that are more acute. Much like the daily brushing and flossing of our teeth and what we do when we crack a tooth, both are important to our health.

The Social Emotional Learning for Teachers course is designed to equip you with both types of strategies as well as an understanding of how stress, and the coping strategies you use to deal with stress, affect your social-emotional and physical well-being.

The Nature of Stress

Stress is defined as a physical or emotional factor that causes bodily or mental tension. It is a normal part of human life—a little stress keeps us from being bored and checked out. But too much stress in a short amount of time or stress that is constant or chronic has a negative impact on our physical and mental health. In care and education settings, stress can affect how we interact with children and families, how we treat our colleagues, and how much satisfaction and commitment we feel when it comes to our work.

When we experience stress, our body reacts as a whole—both mentally and physically. And it makes no difference if the source is personal or professional, as both are intertwined and mutually influential. Stress is accompanied by changes in our physiology and our behavior. Stressors , those things which cause this response, may be experienced differently by each person. Think about giving a speech at a community meeting. You might be comfortable in front of a crowd and welcome the opportunity to share your thoughts about a particular issue, or you may be someone who experiences a near panic attack at the very thought of speaking in front of a group. This individual variation in responding to the event highlights two very important aspects of stress. First, its meaning is unique to the person experiencing it, and this interpretation drives a particular response. Second, the thought alone of a stressful event can be enough to trigger a stress response. Anticipating a difficult conversation with an angry parent or some worrisome personal circumstance can bring about a wide range of reactions.

Stress and Health

“The diseases that plague us now are ones of slow accumulation of damage—heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disorders. … We have come to recognize the vastly complex intertwining of our biology and our emotions, the endless ways in which our personalities, feelings, and thoughts both reflect and influence the events in our bodies…extreme emotional disturbances can adversely affect us…stress can make us sick.” —Robert M. Sapolsky, 2004

From an evolutionary perspective, stress provides us an advantage that can be traced back to our ancient ancestors when life in a cave came with lots of threats. We evolved so that when faced with immediate danger, the brain prepares a reaction: muscles are primed, attention is diverted away from distractions and narrowed toward the source of danger, and all our systems are steeled for the fight or flight response. Mission critical—survive the threat!

In our modern world, survival has moved beyond overcoming the physical threats of our ancestors. Psychological stressors common across workplace settings (e.g., managing difficult behaviors in the classroom) and home life (e.g., arguments with romantic partners or children) confront us daily and challenge our ability to remain relaxed and focused on day-to-day tasks, and our brain responds to the perceived “threats” as if our lives depend on surviving them.

Although evolution has positioned us to react to danger, both physical and psychological, with a sophisticated set of bodily reactions, this state of readiness is not without consequence. Continued engagement in the “stress struggle” depletes physiological resources of the body and may lead to physical and mental health issues and accelerated aging. On the physical side, stress has been linked to lowered immune system functioning, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory problems, problems with weight control, sleep dysfunction, gastrointestinal disorders, and chronic muscle tension. Psychologically, stress is linked to mental health concerns such as anxiety and depression. Furthermore, stress affects perception, cognitive processing, role functioning, morale, job satisfaction, and performance. Stress affects your body, mood, and behavior and, therefore, it affects those around you as well.

Typical Reactions in Response to Ongoing Stress

Physical domain: body.

- Muscle Tension/Pain

- Change in Sex Drive

- Stomach Disturbance

- Sleep Problems

- Jaw Clenching

Emotional Domain: Mood

- Restlessness

- Lack of Motivation

- Feeling Overwhelmed

- Irritability or Anger

- Sadness or Depression

- Attention/Concentration Difficulties

- Feeling Out of Control

- Feeling Incompetent

Behavioral Domain: Behavior

- Overeating or Undereating

- Angry Outbursts

- Drug or Alcohol Use

- Tobacco Use

- Social Withdrawal

- Exercising Less Frequently

- Avoidance of Stressor

- Absenteeism

- Lack of Punctuality

Stress and the Brain

Neuroscientific research has identified the various ways the brain directs our bodily responses, how the brain responds to the environment, and how it is shaped by it (neuroplasticity). This information has helped us understand the brain’s role in both conscious and nonconscious processes involved in behavior.

The brain works as the master organ that controls bodily functions and behaviors through a complex system of electrochemical signals distributed throughout the body via the various parts of the nervous system. In a sense, it is the air-traffic controller of our behavior.

One part of the nervous system, the autonomic nervous system, has two parts: the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic system. These two systems are complementary and work in opposition to keep the body functioning and to preserve life. Your sympathetic nervous system is activated by perceived threats in the environment (your brain interprets events as threatening or nonthreatening) and through a series of messages that call into play the “fight, flight, or freeze” response. When you experience fear, this system shuts down functions that are not necessary so the body systems can be engaged for defense. Typical sympathetic nervous system reactions include increased blood flow to muscles, increased heart rate, sweating, and pupil constriction. Bodily functions such as digestion are temporarily stopped as they are not needed for survival at that moment. The goal of the sympathetic nervous system is to protect your life from some immediate threat. It is a system that is designed for strategic short-term engagement and has been perfected through evolution.

The parasympathetic system is often referred to as the “rest and digest” portion of the autonomic nervous system. Once the immediate threat is removed, the sympathetic system functions slowly fade into the background and the parasympathetic system takes over. The body returns to a calm state and restarts the functions that rebuild physical health and wellness. Functions return, such as digestion, muscle repair, and cognitive processes, including creative thinking and problem solving. The body is free from stress and is able to relax.

The autonomic nervous system is an elegant, evolutionary design that has been perfected to maximize survival. Both humans and other mammals have this instinctive brain-initiated response, which occurs outside of consciousness. Humans and other mammals respond to physical threats in the immediate environment and are equipped to evade or fight-off a threat and eventually return to a pre-stressed state within minutes. Human brains are far more sophisticated than those of other mammals, and we are able to use the power of thought and reason to identify a stressor, evaluate its level of threat, and determine how we should respond. Changing your mind changes your biochemistry, your physical and emotional feelings, and possibly, your behavior. How we view a situation matters.

With higher brain power comes the ability not only to consider immediate threat events but also to consider those in the past and the potential for threat events in the future. Whether the threat is real or imagined, psychological or physical, in the present, past or future, our stress response may be the same. And it may start automatically without our conscious recognition of it.

Prolonged stressors lead to a prolonged stress response; in turn, the physiological stress response may be activated repeatedly or the system may fail to turn off the unnecessary reactions. In this way, humans overuse a system that was designed for short-term use. Scientists now believe that an individual’s personal vulnerability to heightened or prolonged stress reactions may be related to how one views external events. Research supports the notion that variability among people in perception of experiences as stressful is linked to the way individuals view the thing, event, or threat. One’s view of the world and events in it influences physiological responses. Through the use of resilience strategies, we are in a stronger position to identify stressors and diminish their impact on our daily functioning.

Stress and Teachers, Caregivers

Teachers and caregivers working with young children often report a common set of stressors, and researchers have linked teacher stress to their behavior in the classroom. You may be facing some of those stressors that others often experience, or you may be experiencing stressors that are unique to your circumstances. This course will guide you through how to recognize, identify, and deal with stressors that you are experiencing. Some common sources of stress are:

- Personal life challenges

- Working conditions, such as pay, promotion opportunities, and facilities

- Relationships with administrators, co-workers, families, and children

- Children’s challenging behaviors

- A lack of autonomy, control, and motivation

- A lack of stress-reduction resources and strategies

What is Resilience?

Resilience is often thought of as the ability to bounce back from adversity and to overcome obstacles in moving toward one’s goals. Within the world of teaching and caregiving, resilience is a personal quality that allows one to remain committed to teaching despite ongoing challenges in the workplace. It is a sense of personal control and the abilities to commit to learning outcomes and to manage our emotions and behaviors.

Teachers’ and caregivers’ resilience also includes the ability to manage the uncertainties that present themselves in the course of teaching and to maintain social-emotional balance in the classroom and beyond. Building and maintaining this resilience involves several principles. First, resilience is composed of many strategies that can be learned, and what strategies work is uniquely personal—not all strategies work for all people. Second, resilience waxes and wanes across the life span and across careers, making it important to build a personal collection of strategies that can be used during times that are particularly challenging. Third, culture influences the choice of appropriate strategies within various contexts —another reason for a broad collection of strategies. Fourth, resilience strategies support social-emotional learning in teachers and caregivers and in students. Finally, recent research finds that job-related stress in teachers is related to stress reactions among students in the classroom, which suggests a “contagion” effect. Thus, modeling personal resilience may reduce the likelihood of stress-related behaviors being mimicked and increase the likelihood of resilient behaviors being adopted through a modeling effect.

Watch this brief video for a better understanding of why stress affects you.

Stress Response: Savior to Killer

Stanford University

Body-Mind Review Exercise

As you begin to work on managing your stress, it is helpful to have a baseline of stress-related symptoms that you experience. The frequency with which you experience symptoms is related directly to your ability to use resilience strategies and positive coping methods when needed. While it is impossible to control all stressful events and circumstances that face you, it is possible to identify how you react and under what circumstances those reactions occur. This review takes the first step of identifying how you are responding to typical stressors in your life and the different ways in which your body or mind is coping with those challenges. Keep in mind that each person’s response to stress is unique and may vary over time. The exercise here is designed to capture a snapshot of your functioning within the last month.

Review the statements below and reflect on whether each statement is accurate regarding your experience of stress in either your personal or professional world within the last month . You may not necessarily connect the following experiences with stress or with particular events, but recognizing that you experience them is the first step in managing their impact on your wellness and vitality.

Within the last month,

- I experienced tension in my head, shoulders or other body part.

- I felt tired most of the time.

- I often felt as if I hadn’t slept well.

- I experienced some problems related to eating.

- I felt tense and wound up.

- I noticed that I don’t seem to enjoy things as I used to.

- My self-care suffered because of other responsibilities.

- I noticed that my attitude is not as positive as it once was.

- It seemed to take me longer to complete even easy tasks.

- I wondered if I am competent in my role.

- I felt there was not enough time in the day to complete all the tasks on my “to-do” list.

- I relied on alcohol or other drugs such as aspirin to relieve tension.

- I observed that I was short-tempered or expressed frustration.

- I noted that my eating habits had changed.

- I attempted to avoid any stress-related issues or situations.

- I wanted to be left alone.

Having identified the ways in which you typically respond to stressors, keep these in mind as you move through the various activities of this course. Work to implement strategies when you notice that tension headache or feel tense when you face challenging behavior in the classroom. While no one can live a stress-free life (and as you learned, that would not be very adaptive), we can minimize the impact of stressors that are essentially psychological in nature and disruptive to positive functioning and self-enjoyment.

Completing this Course

For more information on what to expect in this course, and a list of the accompanying Learn, Explore, and Apply resources and activities offered throughout the lessons, visit the Focused Topics Social Emotional Learning for Teachers Course Guide .

Please note the References & Resources section at the end of each lesson outlines reference sources and resources to find additional information on the topics covered. As you complete lessons, you are not expected to review all the online references available. However, you are welcome to explore the resources further if you have interest, or at the request of your trainer, coach, or administrator.

How do you define stress? What are your views about your own abilities to manage stress? Download the Thinking About Stress handout. Take a few minutes to read and respond to these questions. Then, discuss your responses with a supportive colleague, friend, or family member.

Thinking About Stress

A great deal of research suggests the importance of managing stress and building resilience. Here you can find a resource from the National Institute of Mental Health. Use this as a resource to learn more about the importance of recognizing and managing stress.

5 Things You Should Know About STRESS

Demonstrate.

Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Raver, C. C., Morris, P. A., & Jones, S. M. (2014). The Role of Classroom-Level Child Behavior Problems in Predicting Preschool Teacher Stress and Classroom Emotional Climate. Early Education and Development , 25 (4), 530-552.

Hall-Kenyon, K. M., Bullough Jr., R. V., MacKay, K. L., & Marshall, E. E. (2014). Preschool Teacher Well-Being: A review of the literature. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42 (3), 153-162. doi:10.1007/s10643-013-0595-4

Huebner C.R. (2019). Health and Mental Health Needs of Children in US Military Families. AAP Section on Uniformed Services, AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects Of Child And Family Health. Pediatrics. 143(1). Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/143/1/e20183258.full.pdf

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79 (1), 491-525. doi:10.3102/0034654308325693

Sapolsky, R.M. (2004). Social Status and Health in Humans and Other Animals. Annual Review of Anthropology, 33 , 393-418. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.144000

- Board of Directors

- National Advisory Board

- OUR RESOURCES

- OUR STORIES

- Our Newsletters

SEL for Educators Toolkit

What is sel for educators.

Social-emotional learning (SEL) shares some similarities with terms such as emotional intelligence, resilience, well-being and self-care. However, the specific components of SEL for adults in school settings are unique.

Educator SEL is:

- The competencies that adults need in order to manage stress and create a safe and supportive classroom environment

- The skills and mindsets that adults need to effectively embody, teach, model and coach SEL for students

- The overall well-being and emotional state of adults in school settings

Why Download the SEL for Educators Toolkit?

This toolkit can be used in Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), staff meetings, professional development, training sessions, or for individual learning, reflection, and practice.

For the purposes of this resource, educator refers to any adult in a school setting who interacts with students. This can include, but is not limited to, classroom teachers, paraprofessionals, principals, deans, instructional coaches, specialists, special education teachers, and coaches. Although this resource can be used by individuals, we encourage collaboration as a way to understand the content, engage in practice, and to expand perspective by processing in community.

The toolkit focuses on the following objectives:

- Educators will reflect on the importance and impact of their own social-emotional learning.

- Educators will learn Five High-Leverage Practices to support their own social-emotional development and well-being.

- Using embedded activities, educators will deepen their understanding and strengthen their skills related to the Five High-Leverage Practices.

The toolkit is designed to be flexible and adaptable; educators can review and use the tools in their entirety, or select one or more focus areas. Due to the wealth of resources focused on system-level support, this toolkit focuses on what educators can do to support their individual growth.

Below, you can download TransformEd’s SEL for Educators Toolkit for educators and school leaders focusing on the social-emotional development and well-being of the adults in school settings.

The Toolkit contains the following resources:

- The Professional Learning Presentation is divided into three sections: The What: Defining Educator SEL, The Why: Supporting Evidence, and The How: High-Leverage Practice . It is designed to provide both content and opportunities for engagement and practice.

- The Companion Guide presents additional details about the interactive components outlined in the presentation, as well as suggestions for pacing, facilitation, application, and further learning.

- The Snapshot summarizes the Five High-Leverage Practices and their corresponding strategies in a simple and accessible handout.

- The Reference List provides a comprehensive list of the resources consulted during the development of this tool for those who would like to dig deeper into the research on this topic.

Mini Modules

We will be releasing six mini modules to introduce our SEL for Educators Toolkit. This toolkit is extensive, therefore each module aims to synthesize the material and walk you through it using the following breakdown:

Module 1 – An Overview: The What, The Why, & The How

Module 2 – Examine Identity

Module 3 – Explore Emotions

Module 4 – Cultivate Compassionate Curiosity

Module 5 – Orient Towards Optimism

Module 6 – Establish Balance & Boundaries

Mini Module #1

Mini Module #2

Mini Module #3

Mini Module #4

Mini Module #5

Mini Module #6

“We must resist thinking in siloed terms when it comes to social-emotional learning (SEL), academics, and equity. Rather, these elements of our work as educators and partners go hand in hand.”

HEAD & HEART, TransformEd & ANet

Get the Latest Updates

© Copyright 2020 Transforming Education. All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Transforming Education is a registered 501(c)3 based in Boston, Massachusetts

Recent Tweet

Take action.

SEL 101 Sample Introductory Presentation

This presentation can be adapted and used to introduce SEL to staff, families, and community partners. It gives an overview of what is SEL, why it’s important, and the process for schoolwide SEL. Talking points and activity instructions are provided in the notes section.

How to Apply Social-Emotional Learning Activities in Education

Now in the classroom, you face the challenge of implementing social-emotional learning (SEL) to help children build the social-emotional skills needed to be “ready to learn.”

But how can you embed SEL skill building into existing classroom routines and lesson plans with efficiency? How do you know if your efforts are working? How do you make adjustments?

We all want to support student learning from a position of safety, responsiveness, inclusion, and connectedness. Strong social-emotional skills, including our own, provide the foundation.

In this article, we will navigate through the skills that we as teachers need, social-emotional learning activities that can make a difference, and assessments that can show if we are on track.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will enhance your ability to understand and work with your emotions and give you the tools to foster the emotional intelligence of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains

- 3 Interventions & Skills for Teachers in the Classroom

8 SEL Activities, Worksheets, and Games for Kids

5 online games and sel activities for virtual classes.

- Best Assessments: 3 Questionnaires & Questions for Students

Building an SEL Curriculum and Lesson Plans: 3 Tools

Ideas for social emotional learning activities for adults, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message, frequently asked questions, 3 interventions & skills for teachers in the classroom.

For a refresher on SEL theory, the five core competencies of social emotional learning, examples of evidence-based SEL curricula, and training and certification opportunities, check out our article What Is Social-Emotional Learning? + Training Courses by educator Dr. Tiffany Sauber Millacci.

In your classroom, you are the driver of SEL. This is true whether you are implementing an SEL program selected by your state or school district, or independently integrating SEL into your lesson plans.

The Social, Emotional, and Ethical (SEE) Learning (2019) framework encourages teachers to approach learning experiences with a three-role mindset. You are a facilitator, you are a model for students, and you are also a learner.

1. Build your own social-emotional competence

Your interactions with students are one of the most powerful contexts in which SEL skills develop. Use the strength of your own social-emotional competence to create an emotionally healthy classroom for students.

Start by reflecting on your own SEL skills. Identify your strengths and challenges with this Personal Assessment and Reflection Tool developed by the Collaborative for Academic and Social Emotional Learning.

Complete the tool individually for self-reflection or with a group of colleagues to discover school-level patterns and attitudes that may influence interactions with students.

Brainstorm ways to model your strengths for students throughout the day. Analyze how your strengths can be leveraged to solve specific challenges in the classroom. Continually problem-solve your own self-care practices as you deepen relationships with students.

If you’d like to start out more gently, listen to this Audio-Guided Mindfulness Practice from Panorama designed specifically for educators focused on self-compassion and building relationship skills.

2. Build trauma-informed skills

Early childhood adversity in the form of poverty, racism, psychological maltreatment, parental depression and addiction, and exposure to violence can cause excessive activation of the stress system that interferes with learning (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020).

Schools and educators play a vital role in supporting children who face adversity, from identifying children in need who may otherwise be overlooked to creating healthy classroom environments where children feel connected and safe.

Extending trauma-informed practices into schools is part of a multi-tiered system of support for children (Chafouleas et al., 2016; Thomas et al., 2019). Intentionally building schools into trauma-sensitive and trauma-informed environments is one way to address the effects of adversity on learning and long-term health.

Trauma-informed training may also alleviate teacher burnout and stress associated with chronic behavior problems in the classroom. Teachers who received trauma-informed training alongside a mindfulness-based SEL program reported feeling more capable of meeting the demands of students who have experienced trauma and had more favorable attitudes about managing their own personal wellness in order to help their students (Kim et al., 2021).

Take a moment to watch this TED talk by educator Syndey Jenson as she describes the powerful role teachers play in the lives of their students and the secondary trauma teachers may experience.

Find actionable steps to support children experiencing trauma in the Trauma Toolkit for Educators available for download by the National Education Association. To build your trauma-informed skills, review these 11 trauma-informed practices used by educators .

Keep SAMSA’s Understanding Childhood Trauma handout readily available to recognize the signs of trauma in children of different ages and how to respond supportively to a child in the moment.

3. Build an SEL community of practice

Communities of practice (CoPs) are groups of people who share a common interest and choose to learn together on a regular basis as they pursue that interest (Merriam, 2017).

Connect with like-minded colleagues with a shared passion for using SEL in the classroom. Dedicate a set meeting time and set objectives. CoPs are rich resources for encouragement and team-oriented problem-solving about social-emotional learning activities that benefit the entire group.

As a start, download this CASEL playbook designed to support teams in building and sustaining powerful SEL-focused CoPs.

Download this CASEL Circle Discussion Guide to create a safe space for collaboration in initial team meetings.

To identify colleagues who share your interests or to ensure everyone in your CoP shares the same understanding of SEL, consider enrolling in the free Introduction to SEL course from CASEL.

What is the purpose of the activity? Is there a challenge in the classroom you would like to address by building SEL skills in your students?

Identify the specific SEL skills you want to target in order to meet your purpose. Operationalize them to communicate them to students and measure them. To get you started, this video describes the five key competencies common to SEL along with specific SEL skills you may choose to target.

Transparency

What do you want students to know about your purpose or about the SEL skills you are targeting?

Determine who is the focus of the activity. Student-to-student interaction, pairs, triads, teacher-to-student interaction, an independent activity, or a mix?

Based on the results of the PATT method, consider these SEL activities as potential starting points:

- Wish, outcome, obstacles, plan (WOOP) This method helps to build self-control in kids to achieve personal goals. Students specify a wish , identify and imagine the best outcome , identify potential obstacles , and form a plan . Watch the WOOP video introduction and download the educator facilitation guide, exercise templates, and social-emotional learning activities from Character Lab .

- Emotions and feelings games Use this crossword puzzle, pairing emotion words to their definitions. Also from Better Kids , use this word search to introduce new emotional words, followed by a circle-time discussion about different intensities of particular emotions.

- Emogometer In this embodied activity, children identify an emotion they are feeling, how big they are feeling the emotion, and demonstrate to others the emotion they are feeling. It is an ideal activity to start the day. Watch a video demonstration of the emogometer from Move This World .

- Flower worksheet Children identify people in their lives who support them and describe how they feel supported. Each petal of the flower represents a person in their support system. Learn more about the benefits to children of knowing who to count on, along with activity instructions and a downloadable flower worksheet from Better Kids .

- Community-building circle Circle discussions provide a physical setting and a structured process to improve communication and build community among students in the classroom. Step-by-step instructions for opening the circle, doing the work, and closing the circle along with sample scripts are provided by CASEL .

- Focusing on me and you Children engage in mindfulness practice, active listening , and perspective-taking exercises to learn to appreciate differences in others and build empathy. Educator instructions and presentation slides are available from Soar with Wings .

- Problem, options, outcomes, choices (POOCH) protocol The POOCH protocol is a method for walking through the steps of making tough decisions that require judgment, assessing risk, or may not have an answer that benefits everyone equally.

- Time to play Children explore responsible decision-making in the context of building a board game with others. Educator instructions and presentation slides are available for download from Soar with Wings .

As you select, facilitate, and adapt SEL activities to meet the needs of your students, use four characteristics of effective and evidence-based approaches to SEL that align with the acronym “SAFE” (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, n.d.).

- Sequenced Connect and coordinate multiple social-emotional learning activities to strengthen targeted skills.

- Active Keep learning active with physical movement, conversation, and learning materials.

- Focused Establish dedicated time and attention for developing social-emotional skills.

- Explicit Communicate to students the specific SEL skills you are teaching as you are teaching them.

Download 3 Free Emotional Intelligence Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients understand and use emotions advantageously.

Download 3 Free Emotional Intelligence Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

You can also teach SEL skills in virtual classes with online games and apps. Options range from simple SEL games played in small groups to interactive games with avatars and built-in SEL assessment tools for teachers.

1. How we feel

Track emotions throughout the day, find the words and feelings to describe emotions, and try strategies to help regulate emotions. This app was developed by researchers at the Yale University Center for Emotional Intelligence .

Available on iOS .

2. Wisdom: The World of Emotions

3. MyPeekaville

Available on Google Play .

4. Classcraft

Available on iOS and Google Play .

5. Virtual read-alouds

Use video call software for interactive class read-alouds . Pause to allow students to identify, imitate, and predict character emotions, propose solutions to social problems, and take different perspectives. Recommended SEL-focused books:

- The Dot : Self-awareness for pre-kindergarten to fourth grade

- Decibella and Her 6-inch Voice : Self-management for kindergarten to fifth grade

- All Are Welcome : Social awareness for pre-kindergarten to second grade

- Enemy Pie : Relationship skills for kindergarten to third grade

- The Empty Pot ; Responsible decision-making for kindergarten to third grade

Best Assessments: 3 Questionnaires & Questions for Students

The best student assessments are selected with purpose. To guide your selection, ask yourself:

- Is the assessment informational to track student progress?

- Is the assessment going to be used to communicate with parents, other teachers, or school administrators?

- Will the assessment be used to track accountability required of your school, district, or funding organization?

Ideally, an assessment should be selected before implementing the activity or intervention to ensure you are measuring the student skill or outcome you intend to improve.

1. Panorama Social-Emotional Learning Survey

Questions for students in grades 3–5 and 6–12 to assess:

- Competencies and skills (e.g., grit, growth mindset, self-regulation, self-efficacy)

- Student support and environment (e.g., sense of belonging, school safety, engagement)

- Student wellbeing (e.g., positive feelings, supportive relationships)

Response format is Likert scale and free-response.

Access the survey here .

2. EPOCH Measure of Adolescent Wellbeing

This is a free student report assessment of five positive characteristics that support higher levels of wellbeing in adolescents: engagement, perseverance, optimism, connectedness, happiness.

Modified from Seligman’s (2018) five-pillar PERMA model of adult wellbeing, this assessment can be used as a before-and-after intervention measure of adolescent wellbeing and happiness (Kern et al., 2016).

Access the assessment here .

Use prompts, questions, and check-ins individually or in a group setting as an informal assessment of social-emotional competence and student wellbeing.

- Describe a time when you felt really proud of yourself.

- Describe a behavior you are working to improve.

- What is something you take for granted that someone else may not have?

- Where is a place you would love to visit?

- If you could have any superpower, what would you choose?

- What is something that calms you down?

- How have you been sleeping lately?

- How included in class did you feel today?

- What emotion are you feeling the most today?

- What would you be known for if you were famous?

- If you could travel back in time to X grade, what advice would you give yourself?

- If you could make one rule everyone at school had to follow, what would it be?

- What does a typical morning look like for you?

For additional assessments of SEL and student wellbeing by grade and outcome, review this comprehensive SEL assessment toolbox from the American Institutes for Research.

1. CASEL Program Guide

The Collaborative for Academic and Social Emotional Learning (CASEL) provides a comprehensive program guide to walk you through the selection of an effective SEL program from start to finish.

All CASEL-recommended SEL programs are evidence-based. The end-to-end tool involves three steps:

- Identify your SEL goals.

- Identify features of SEL programs you want to prioritize to meet your goals.

- Explore SEL programs and compare your top selections.

Filter programs by approach (such as free-standing lesson, integrated lessons, or classroom management), outcome (such as improved academic performance, social behaviors, reduced problem behaviors, or reduced emotional distress), student characteristics (such as low-income, multi-race, Hispanic/Latinx), school characteristics (such as urban, suburban, or Midwest) program support offered, and training offered.

Download the Quickstart Guide for a summary of the CASEL tool.

2. Navigating SEL From the Inside Out

This comprehensive SEL guide (Jones et al., 2021) includes an evaluation of 33 evidence-based programs for kindergarten through elementary school-aged children. Get a birds-eye view of each program individually and collectively on three metrics in easy-to-read tables.

Once you have a few programs in mind, dig into the snapshot summary of each program, which describes program effectiveness, grade range, duration of program, and unique features.

3. Explore SEL

Explore SEL is an evidence-based interactive tool to navigate widely used nonacademic frameworks of SEL. Begin by browsing through the different SEL frameworks to see which you recognize. Get a feel for the complexity of SEL that comes from differences in how we define, teach, and measure it.

Next, use the tool to select the framework that will guide your SEL work and reduce the complexity.

- Compare frameworks across different domains of learning (e.g., cognitive, emotions, social, values, perspective, identity).

- Compare SEL skills targeted by different frameworks (e.g., overlapping SEL skills targeted by the CASEL framework vs. P21’s 21st Century Learning framework).

- Identify related SEL skills used across frameworks,

Play! Games and group SEL activities are rich contexts for adults to practice a wide range of social-emotional skills. Most involve some form of active learning about yourself and others, embodied action, social interaction, competitiveness, and creativity.

1. We’re Not Really Strangers

We’re Not Really Strangers is a multiplayer card game to learn about yourself, strengthen your relationships, and get to know new people. Check out versions for first dates, couples, families, and self-awareness.

2. The Hygge Game

This multiplayer card game has interesting and entertaining questions to bring more joy to your life based on the Danish concept hygge.

3. Organized group activities

Get involved with a group that meets regularly for a specific purpose. For example, join a choir, knitting group, running club, book club, dance group, volunteer group, or recreational sports league. For older adults, participating in choir and group exercise predicts positive emotional wellbeing (Maury et al., 2022).

4. Self-reflection

As adults, we may not be aware of the SEL skills we already use to nurture relationships, calm ourselves, and manage emotions. Bring awareness to your own SEL strengths and challenges with this Personal SEL Reflection tool. Use individually or as a community of practice activity.

17 Exercises To Develop Emotional Intelligence

These 17 Emotional Intelligence Exercises [PDF] will help others strengthen their relationships, lower stress, and enhance their wellbeing through improved EQ.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

We have a variety of resources that can supplement your academic learning, all well worth checking out.

As a start, you may be interested in our article filled with training resources: Social Skills Training for Kids .

You can also identify SEL strengths and weaknesses through self-awareness. Check out our blog on How to Increase Self-Awareness: 16 Activities and Tools .

Prompting children with more self-reflection questions is made easier with our article, Learning Through Reflection: Questions to Inspire Others .

Another brilliant article filled with activities and games: 16 Activities to Stimulate Emotional Development in Children .

Besides our blog articles, here are two worksheets that can be used in the classroom.

Increase awareness of the different emotions experienced throughout the day through simple observation with our Emotional Awareness worksheet .

Use this Conflict at School worksheet with children to bring awareness to different relationships they have at school and difficulties they have with individual friends.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop emotional intelligence (EI), check out this collection of 17 validated EI tools . Use them to help others understand and use their emotions to their advantage.

So much of academic learning relies on feeling safe and accepted at school, recognizing and managing emotions, cooperating and working well with others, resolving conflict, and understanding emotions and perspectives of classmates.

The classroom is rich with opportunities to build and actively practice these SEL skills, and they go hand in hand with academic learning.

Academic mastery alone cannot lead to “student success”. We must be brave enough to believe that for each child, lifelong success is a unique combination of social, emotional, cognitive, and academic skills.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free .

Examples of social-emotional learning activities include brain breaks, daily teacher–student greetings, journal writing, partner work, emotion check-ins, class agreements, and gratitude lists.

Activities that can help child development include pretend play, labeling emotions in self and others, joint book reading, perspective taking, mindfulness, asking for help, offering help to others, and identifying goals.

Yes, SEL can be implemented outside the classroom. Adults, parents, and caregivers can embed SEL into after-school programs, organized sports, during dinner, and at the grocery store.

- Chafouleas, S. M., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., & Santos, N. M. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health , 8 , 144–162.

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (n.d.). Adopt an evidence-based program for SEL . https://schoolguide.casel.org/focus-area-3/school/adopt-an-evidence-based-program-for-sel/.

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2019). Social emotional learning: 3 Signature practices playbook . https://casel.org/casel_sel-3-signature-practices-playbook-v3/

- Jones, S. M., Brush, K., Bailey, R., Brion-Meisels, G., McIntyre, J., Kahn, J., & Stickle, L. (2021). Navigating SEL from the inside out: Looking inside and across 25 leading SEL programs: A practical resource for schools and OST providers. Preschool and elementary focus (2nd ed.). The Wallace Foundation.

- Kern, M. L., Benson, L., Steinberg. E. A., & Steinberg, L. (2016). The EPOCH Measure of Adolescent Well-being. Psychological Assessment , 28 (5), 586–597.

- Kim, S., Crooks, C. V., Bax, K., & Shokoohi, M. (2021). Impact of trauma-informed training and mindfulness-based social–emotional learning program on teacher attitudes and burnout: A mixed-methods study. School Mental Health , 13 , 5–68.

- Maury, S., Vella-Brodrick, D., Davidson, J., & Rickard, N. (2022). Socio-emotional benefits associated with choir participation for older adults related to both activity characteristics and motivation factors. Music & Science , 5 .

- Merriam, S. B. (2017). Theories of adult learning: Evolution and future directions. PAACE Journal of Lifelong Learning , 26 , 21–37.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2020). Connecting the brain to the rest of the body: Early childhood development and lifelong health are deeply intertwined . https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/connecting-the-brain-to-the-rest-of-the-body-early-childhood-development-and-lifelong-health-are-deeply-intertwined/

- SEE Learning. (2019). The SEE Learning companion: Social, Emotional, and Ethical Learning . Emory University.

- Seligman, M. (2018). PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology , 13 (4), 333–335.

- Thomas, M. S., Crosby, S., & Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: An interdisciplinary review of research. Review of Research in Education , 43 (1), 422–452.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Learning Disabilities: 9 Types, Symptoms & Tests

Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, Sylvester Stalone, Thomas Edison, and Keanu Reeves. What do all of these individuals have in common? They have all been diagnosed [...]

Best Courses for Counselors to Grow & Develop Your Skills

Counselors come from a great variety of backgrounds often with roots in a range of helping professions. Every counselor needs to keep abreast of the [...]

What Is Social–Emotional Learning? + Training Courses

The days of just teaching kids their ABC’s are long gone. Modern educators are tasked with the seemingly impossible responsibility of ensuring today’s youth are [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (48)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

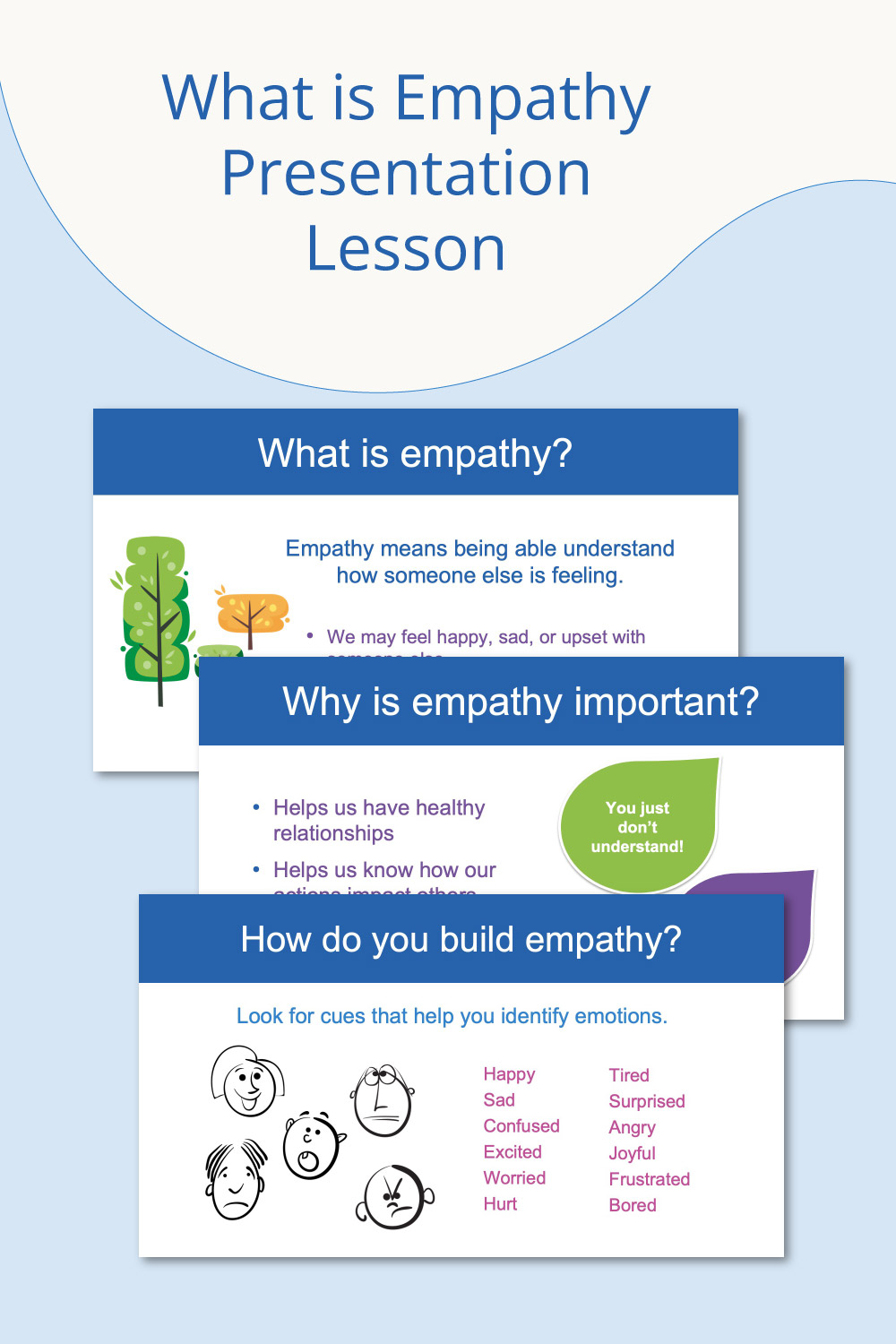

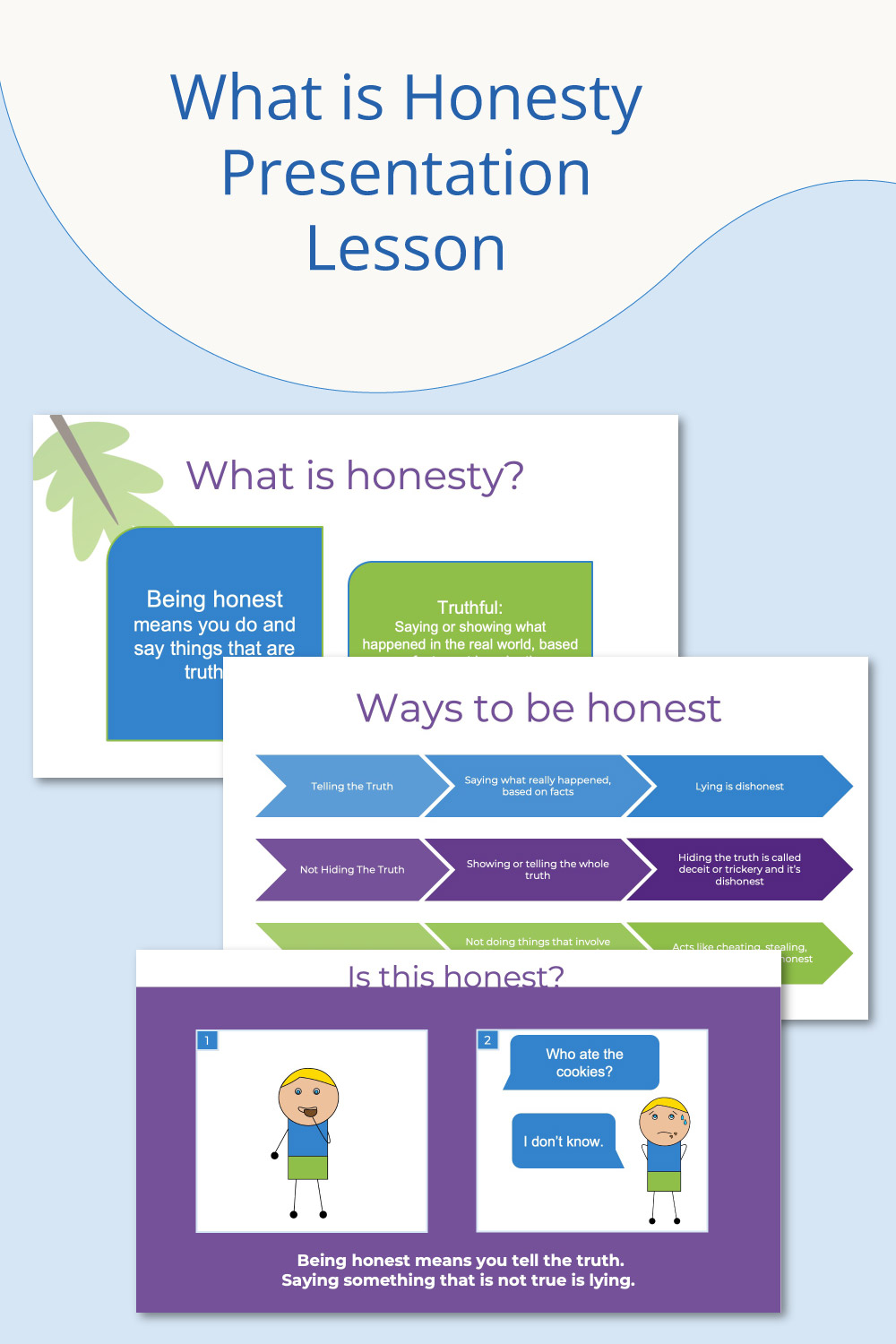

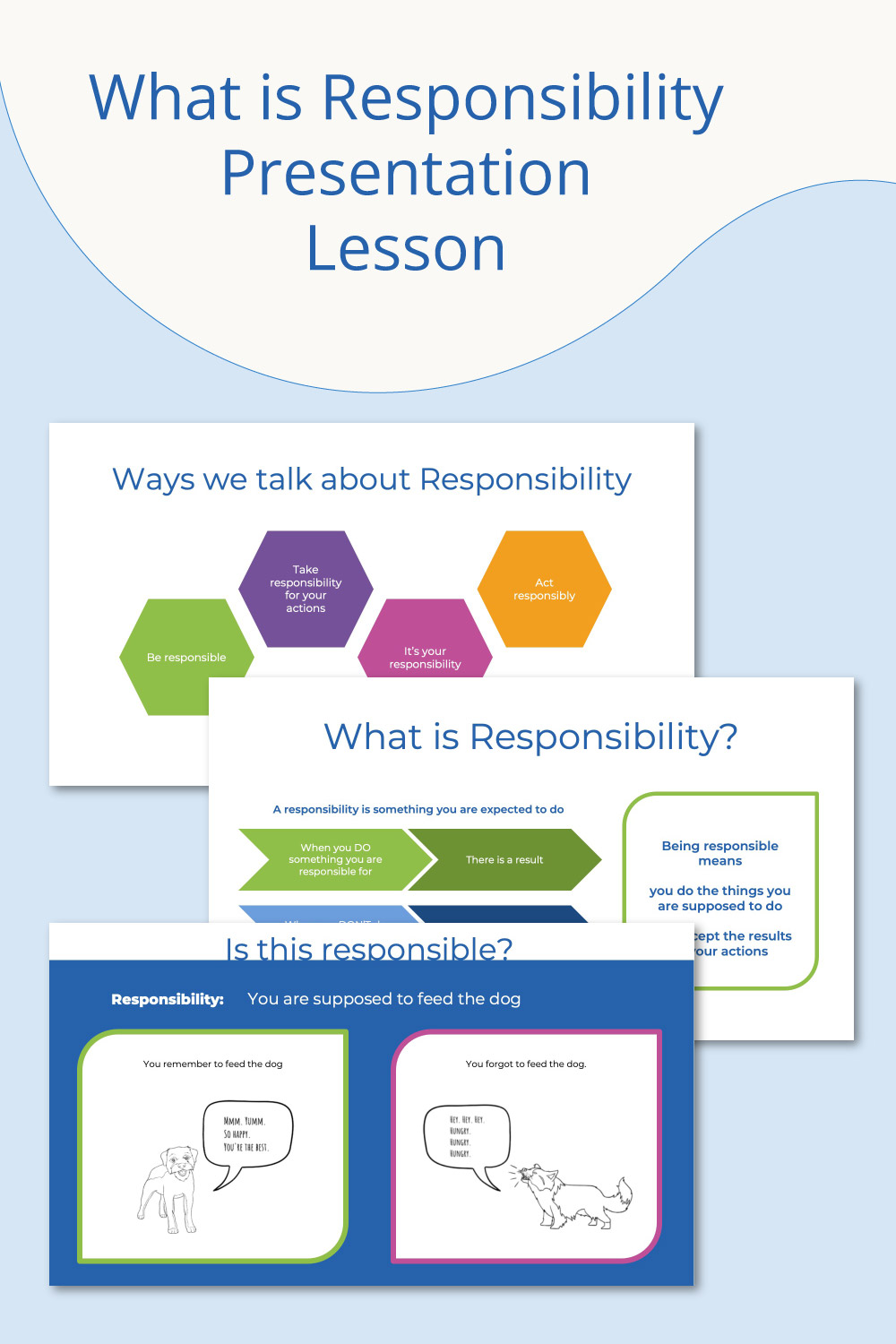

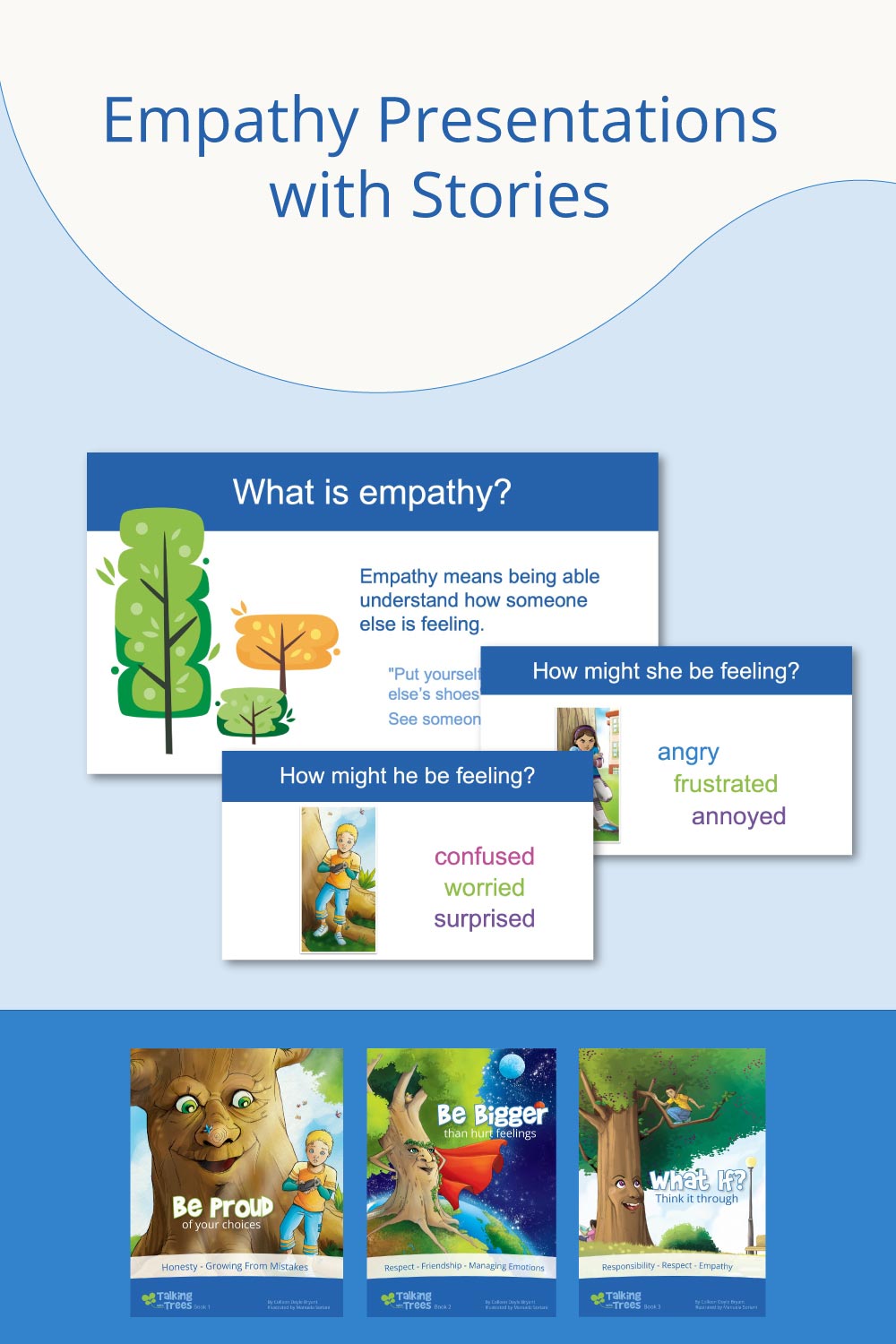

Free Presentationsfor Elementary Social Emotional Learning

These PowerPoint / Google Slides presentations are ready to post for your next social emotional learning lesson. Discover presentations on topics in empathy, honesty, and more social emotional topics to come.

Create an SEL Lesson

Our presentations can be used alone, or together with our other social emotional learning teaching resources, including books, worksheets, and lesson plans. Explore teaching resources . Our presentations are free to share for non-commercial use.

Empathy Presentation

What is empathy, why it's important, and how to build empathy.

Presentation Info

Honesty Presentation

Explore several aspects of honesty with this picture-based presentation.

Responsibility Presentation

Explain what responsibility is and why it's important.

Respect Presentation

Teach how to show respect for people, places, things.

Empathy Presentations

Using stories and a presentation, help students learn to identify others' emotions.

You may also like:

- Online Degree Explore Bachelor’s & Master’s degrees

- MasterTrack™ Earn credit towards a Master’s degree

- University Certificates Advance your career with graduate-level learning

- Top Courses

- Join for Free

The Teacher's Social and Emotional Learning

This course is part of The Teacher and Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Specialization

Taught in English

Some content may not be translated

Instructors: Dan Liston +1 more

Instructors

Instructor ratings.

We asked all learners to give feedback on our instructors based on the quality of their teaching style.

Financial aid available

17,312 already enrolled

(601 reviews)

What you'll learn

Explore the place of sadness and related emotions in teaching

Explore the role of joy and passion related in teaching and how they can concretize a teacher’s set of beliefs about education and teaching

Reflect on the definitions and roles of grit, grace, and personal wholeness in the profession of teaching

Details to know

Add to your LinkedIn profile

See how employees at top companies are mastering in-demand skills

Build your subject-matter expertise

- Learn new concepts from industry experts

- Gain a foundational understanding of a subject or tool

- Develop job-relevant skills with hands-on projects

- Earn a shareable career certificate

Earn a career certificate

Add this credential to your LinkedIn profile, resume, or CV

Share it on social media and in your performance review

There are 5 modules in this course

Social and emotional learning, or SEL, programs have flourished in schools during the last decade. While this growth has been impressive, inadequate attention has been paid to teachers’ social and emotional learning. In this course Dan Liston and Randy Testa introduce you to various rationales for why teacher SEL is needed as well as examine and reflect on various emotions in teaching and learning.

This course is a part of the 5-course Specialization “The Teacher and Social Emotional Learning (SEL)”. Interested in earning 3 university credits from the University of Colorado-Boulder for this specialization?? If so check out "How you can earn 3 university credits from the University of Colorado-Boulder for this specialization" reading in the first module of this course for additional information. We want to note that the courses in this Specialization were designed with a three-credit university course load in mind. As a participant you may notice a bit more reading content and a little less video/lecture content. Completing and passing the SEL Specialization allows the participant to apply for 3 graduate credits toward teacher re-certification and professional enhancement. We want to ensure the quality and high standards of a University of Colorado learning experience. Interested in earning 3 graduate credits from the University of Colorado-Boulder for The Teacher and Social Emotional Learning (SEL) Specialization? Check out "How you can earn 3 university credits from the University of Colorado-Boulder for this specialization" reading in the first week of this course for more information.

Why SEL and the teacher?

Here we introduce what SEL is and why it is important for all teachers. We elaborate the need for the teacher to enhance her/his knowledge of self, especially his/her own social and emotional terrain. A guiding premise is that deeper teacher self-understanding facilitates and enhances deeper student relations and greater chances for the transformative possibilities for student and teacher. A related premise is that by examining our deeply held cherished beliefs and emotional responses to situations and texts, we create opportunities for further insights into why and the ways we teach.

What's included

4 videos 2 readings 1 quiz 1 discussion prompt

4 videos • Total 20 minutes

- Introduction to the Specialization • 1 minute • Preview module

- Course Introduction Video • 3 minutes

- Instructional Introduction - Randy and Dan • 7 minutes

- Every Kid Needs a Champion - Rita Pierson • 7 minutes

2 readings • Total 109 minutes

- How you can earn 3 university credits from the University of Colorado-Boulder for this specialization • 4 minutes

- Module 1 Materials- PDFs and Website • 105 minutes

1 quiz • Total 10 minutes

- Module 1 • 10 minutes

1 discussion prompt • Total 30 minutes

- Self and Professional Understandings • 30 minutes

What does teaching do to teachers?

Here we further elaborate the need for the teacher to enhance her/his knowledge of self, especially his/her emotional responses as well as deeply held beliefs.

1 video 1 reading 1 quiz 1 discussion prompt

1 video • Total 3 minutes

- Instructional Introduction - Randy • 3 minutes • Preview module

1 reading • Total 90 minutes

- Module 2 Materials- Videos and PDFs • 90 minutes

- Module 2 • 10 minutes

- What Does Teaching Do to Teachers • 30 minutes

Sadness and despair in teaching

The value of reflection on and examination of sadness, despair, and related emotions in teaching is seen as one example of an enhanced “granularity” offered to teachers through reflection on emotions.

- Instructional Introduction - Randy and Dan • 3 minutes • Preview module

1 reading • Total 160 minutes

- Module 3 Materials- Film and PDF • 160 minutes

- Module 3 • 10 minutes

1 discussion prompt • Total 10 minutes

Joy, passion, and enjoyment in teaching.

The value of reflection on and examination of joy and passion, as well as other related emotions in teaching is seen as another example of an enhanced “granularity” that can be gained by teachers through a reflection on emotions.

2 videos 1 reading 1 quiz 1 discussion prompt

2 videos • Total 13 minutes

- Instructional Introduction Video – Randy and Dan • 2 minutes • Preview module

- Attentive Love - Lure of Learning in Teaching - Dan • 11 minutes

1 reading • Total 110 minutes

- Module 4 Materials- PDFs • 110 minutes

- Module 4 • 10 minutes

- Module 4 Discussion • 30 minutes

Grit and wholeness in teaching

By contrasting “grit” and “wholeness” in teaching and learning we explore further the value we as individuals place on these two orienting dispositions.

3 videos 1 reading 1 quiz 1 discussion prompt

3 videos • Total 20 minutes

- Instructional Introduction Video – Randy and Dan • 6 minutes • Preview module

- Angela Lee Duckworth - Grit: The Passion and Perseverance • 6 minutes

- Angela Lee Duckworth - Character Traits • 7 minutes

- Module 5 Materials - PDFs and Website • 90 minutes

- Module 5 • 10 minutes

- Grit and Wholeness in Teaching • 30 minutes

CU-Boulder is a dynamic community of scholars and learners on one of the most spectacular college campuses in the country. As one of 34 U.S. public institutions in the prestigious Association of American Universities (AAU), we have a proud tradition of academic excellence, with five Nobel laureates and more than 50 members of prestigious academic academies.

Recommended if you're interested in Education

University of Colorado Boulder

SEL Capstone

Expanding SEL

SEL for Students: A Path to Social Emotional Well-Being

Teacher SEL: Programs, Possibilities, and Contexts

Why people choose coursera for their career.

Learner reviews

Showing 3 of 601

601 reviews

Reviewed on Jun 1, 2020

Very helpful and easy to understand. Videos and learning recordings are very helpful. Thank you for all the support. Look ahead for more learnings and insights.

Reviewed on Jun 3, 2020

This is a great initiation to the SEL specialization. It covers an integral part which is the teacher's own well being that allows them to engage in SEL with their students.

Reviewed on May 4, 2020

I loved the readings and videos in this program. I am grateful to be able to expand on my own well-being so that I can continue to pursue supporting the 'whole being' of my students.

Open new doors with Coursera Plus

Unlimited access to 7,000+ world-class courses, hands-on projects, and job-ready certificate programs - all included in your subscription

Advance your career with an online degree

Earn a degree from world-class universities - 100% online

Join over 3,400 global companies that choose Coursera for Business

Upskill your employees to excel in the digital economy

Frequently asked questions

When will i have access to the lectures and assignments.

Access to lectures and assignments depends on your type of enrollment. If you take a course in audit mode, you will be able to see most course materials for free. To access graded assignments and to earn a Certificate, you will need to purchase the Certificate experience, during or after your audit. If you don't see the audit option:

The course may not offer an audit option. You can try a Free Trial instead, or apply for Financial Aid.

The course may offer 'Full Course, No Certificate' instead. This option lets you see all course materials, submit required assessments, and get a final grade. This also means that you will not be able to purchase a Certificate experience.

What will I get if I subscribe to this Specialization?

When you enroll in the course, you get access to all of the courses in the Specialization, and you earn a certificate when you complete the work. Your electronic Certificate will be added to your Accomplishments page - from there, you can print your Certificate or add it to your LinkedIn profile. If you only want to read and view the course content, you can audit the course for free.

What is the refund policy?

If you subscribed, you get a 7-day free trial during which you can cancel at no penalty. After that, we don’t give refunds, but you can cancel your subscription at any time. See our full refund policy Opens in a new tab .

Is financial aid available?

Yes. In select learning programs, you can apply for financial aid or a scholarship if you can’t afford the enrollment fee. If fin aid or scholarship is available for your learning program selection, you’ll find a link to apply on the description page.

More questions

SOCIAL EMOTIONAL LEARNING

SUPERINTENDENT’S COFFEE

OCTOBER 10, 2019

PHYLLIS ALPAUGH & JAMIE ARGENZIANO

What is SOCIAL EMOTIONAL LEARNING (SEL)?

- Defined by experts as “the process in which both adults and children develop the self-awareness, self-control, and interpersonal skills that are vital for school, work, and life success”.

- Research show that people with strong social emotional skills are better able to cope with everyday challenges and benefit academically, professionally and socially.

- Also SEL is best accomplished through effective classroom instruction, student engagement in positive activities in and out of the classroom and broad parent and community involvement.

The Five (5) Competencies

- Self-Awareness —Involves understanding one’s own emotions, personal goals, and values

- Self-Management —Requires skills and attitudes that facilitate the ability to regulate one’s own emotions and behaviors

- Social Awareness— The ability to understand, empathize and feel compassion for those with different backgrounds or cultures

- Relationship Skills —Helps establish and maintain healthy and rewarding relationships to act in accordance with social norms

- Responsible Decision Making— Learning how to make constructive choices about personal behavior and social interactions across diverse settings.

WHAT are the SHORT and LONG term benefits?

- Students are more successful in school and daily life when they:

- Know and can manage themselves

- Understand the perspectives of others and relate effectively

- Make sound choices about personal and social decisions

- ALSO, students with strong SEL skills frequently demonstrate :

- More positive attitudes towards themselves, others and tasks

- More positive social behaviors and relationships with peers and adults

- Reduce conduct problems and risk-taking behaviors

- Decreased emotional stress

- Improved test scores, grades and attendance

HOW is the Best Way to Teach Social Emotional Skills?

- School is one the primary places where students learn SEL skills with integrated programs considered the most effective

- Effective programs should incorporate the following elements:

- S equenced, connected and coordinated sets of activities

- A ctive forms of learning to help students master skills

- F ocused emphasis on developing personal and social skills

- E xplicit targeting of specific social and emotional skills

Building Upon School Programs

- Effective SEL programming not only involves school and district wide coordination, but relies on Family and Community Partnerships to both strengthen and reinforce the impact of school approaches.

- This involves bringing the learning into both the home and the neighborhood

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2d0da6BZWA&t=289s

WHAT is the Borough doing to promote SEL?

- It is a district goal for the 2019-20 school year that is reflected in building and individual staff Professional Development Plans

- There is training and professional development in place for administrators, staff and STUDENTS including motivational pep rallies and programs

- There is a Teacher Resource Platform with a plethora of resources

- We as a district have a made a pledge to infuse and integrate all aspects of SEL into the curriculum and daily instruction

Thank you for coming !

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

12 templates

68 templates

el salvador

32 templates

41 templates

48 templates

33 templates

Social-Emotional Learning Infographics

Premium google slides theme and powerpoint template.

Social Emotional Learning, or SEL, is the process in which competences like self-awareness, control, or communication skills are learned. It is a very important part of the development of children since it affects how they interact with the world and with other people. If you want to speak about SEL, infographics like the ones of this set might be helpful, they make data comprehensible and easily retainable since they represent it in a visual way, and they’re also very easy to use. Download this set and start preparing your presentation about the importance of SEL in education!

Features of these infographics

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 31 different infographics to boost your presentations

- Include icons and Flaticon’s extension for further customization

- Designed to be used in Google Slides, Microsoft PowerPoint and Keynote

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Include information about how to edit and customize your infographics

How can I use the infographics?

What are the benefits of having a Premium account?

What Premium plans do you have?

What can I do to have unlimited downloads?

Don’t want to attribute Slidesgo?

Gain access to over 22300 templates & presentations with premium from 1.67€/month.

Are you already Premium? Log in

Related posts on our blog

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

Register for free and start editing online

Social and Emotional Learning

Oct 31, 2014

470 likes | 1.12k Views

Social and Emotional Learning. A Foundation for Vocational Training and Success. Social & Emotional Learning (SEL):. An educational process intended to develop emotional intelligence. Social & Emotional Competencies. Self-awareness Self-management Social awareness Relationship skills

Share Presentation

- emotional learning

- emotional intelligence

- decision making

- comprehensive sel intervention

- staff develop core competencies

Presentation Transcript

Social and Emotional Learning A Foundation for Vocational Training and Success

Social & Emotional Learning (SEL): An educational process intended to develop emotional intelligence

Social & Emotional Competencies • Self-awareness • Self-management • Social awareness • Relationship skills • Responsible decision making From the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL)

SEL skills are essential to academic, personal, social and civic success.

Social and Emotional Learning Improves Student Outcomes Meta-analysis of 213 SEL and related interventions Students and staff showed increased social and emotional competence.

Seattle Social Development Project SEL interventions in elementary school classrooms resulted in long term gains ____________________________ • Longitudinal study • Began 1981 • 808 elementary school children • Comprehensive SEL intervention from 1st thru 6th grade

Employability SEL builds: Communication skills Cooperative team members Strong leaders Caring community members

WANTED: Big company seeks emotionally intelligent individuals to contribute to team effort and to be strong leaders in the business world. Possibility for growth. Good salary. Full benefits.

Applying what we know…… At Cascades Job Corps Center: • 10 week group • SEL, character development and leadership materials • Mostly experiential

Group Curriculum Weeks 1-5 • Emotional awareness and expression • Emotional awareness and regulation • Emotion regulation and impact on decision making • Gratitude • Physical self-awareness

Group Curriculum Weeks 6-10 • Physical self-awareness • Values • Decision making and group dynamics • Empathy • Review of topics and group discussion

Using SEL concepts with staff: Staff Training Help staff develop core competencies ---- Teach staff why emotional intelligence is important in the workplace ---- Identify ways staff can help students develop core competencies as employability skills

Using SEL concepts with staff: Staff Assessment Center Director and CMHC asked management level staff to complete Bar-On EQi ---- Areas for further training were identified

Resources for learning about and applying SEL at Job Corps: • Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) • School Connect • Greater Good Science Center • Communities for Children • Mindsight Institute • Edutopia

Bibliography • Ciarrochi, Joseph, Forgas, Joseph P., and Mayer, John D. (Eds.). (2006). Emotional Intelligence in Everyday Life (2nd ed.). New York: Psychology Press. • DeAngelis, Tori (2010, April). Social Awareness + Emotional Skills=Successful Kids. Monitor on Psychology, 46-49. • Project EXSEL: Excellence in Social and Emotional Learning in the City of New York http://pd.lit.columbia.edu/projects/exsel/index.html • The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning http://www.casel.org/SEL.htm

- More by User

Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning

Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning. Oldway Primary School NPD 3 rd September 2007. There are five social and emotional aspects of learning:. Self awareness Managing feelings Motivation Empathy Social skills. Why is it important to develop these aspects of learning?.

435 views • 13 slides

Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL)

Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) . Whole School Inset Press here for the staff development activities you will need for this presentation. Programme. Session 1: Setting the scene What is SEAL and what’s in it for our school? Session 2: Where are we now?

546 views • 25 slides

![social emotional learning presentation for teachers Social and Emotional Learning: An Introduction [Date]](https://cdn4.slideserve.com/696332/social-and-emotional-learning-an-introduction-date-dt.jpg)

Social and Emotional Learning: An Introduction [Date]

Social and Emotional Learning: An Introduction [Date]. Presenter:. Welcome. Guiding Questions:. What is SEL ? Why does SEL matter? How can school communities promote SEL for young people ?. What are your hopes and dreams for your child or the children in our community?.

614 views • 28 slides

Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning. Which SEAL skills will you need to use in today's lesson?. Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning. Self awareness Knowing myself Understanding my feelings. Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning. Managing my feelings

226 views • 7 slides

Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Overview

Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Overview. Trish Shaffer, MTSS Coordinator Sam Shoolroy, SEL Specialist. Guess Who…. Write one little known fact about YOU, personal or professional, on a sticky. No need for names Please hand to one of us!. Objectives.

768 views • 19 slides

Social-Emotional Learning

Social-Emotional Learning. Developing personal investment, knowledge, and the regulation of self in connection to staff and classmates. Objective for this session:.

243 views • 11 slides

Social Emotional Learning Feelings and Friendships

Social Emotional Learning Feelings and Friendships. Everyone gets ANGRY -What makes you feel wild?. DIFFERENT TASTES…. DIFFERENT INTERESTS…. Healthy friendships at school. Expect good and bad. Trust one another and be trustworthy What does ‘trustworthy’ mean?.

520 views • 36 slides

Schoolwide Social Emotional Learning

Schoolwide Social Emotional Learning. Jointly Developed By:. The Autism Society. The IDEA Partnership Project (at NASDSE). With funding from the US Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP).

580 views • 29 slides

Social and Emotional Learning. Questions For Our Session. What is Social and Emotional Learning (SEL)? How does SEL promote success in school and life? What is SCUSD's plan for the next three years? What will SEL integration look like at the district, school, and classroom levels?

480 views • 15 slides

Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL). Whole School Inset Press here for the staff development activities you will need for this presentation. Programme. Session 1: Setting the scene What is SEAL and what’s in it for our school? Session 2: Where are we now?

421 views • 25 slides

Social and Emotional Learning :

Social and Emotional Learning :. In the Elementary School at BFIS. What is SEL?. Social and Emotional Learning Five Key Areas : Self-Awareness Self -Management Social Awareness Relationship skills Responsible decision making

419 views • 15 slides

SEAL ( Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning)

SEAL ( Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning). “Where will we fit this in !!” The aim of this workshop is to allow participants to consider and address implementation issues when planning SEAL within or alongside their PSHE and Citizenship provision.

376 views • 17 slides

Wedging in Social Emotional Learning:

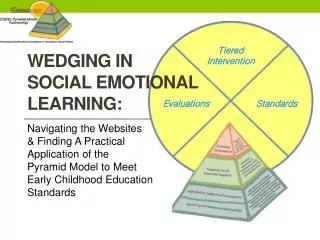

Tiered Intervention. Wedging in Social Emotional Learning:. Evaluations. Standards. Navigating the Websites & Finding A Practical Application of the Pyramid Model to Meet Early Childhood Education Standards. IF YOU DID NOT GET A HANDOUT:. GO TO: http://teamtn.tnvoices.org

984 views • 65 slides

Social and Emotional Learning in Schools

Social and Emotional Learning in Schools. Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl Shelley Hymel TEO Orientation, August 26, 2014. “ Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all . ”. - Aristotle. http://educatingtheheart.org/. Why Now?.

713 views • 33 slides

What is Social and Emotional Learning?

What is Social and Emotional Learning?. Building Resilience in Children and Young People. Teacher Professional Development. What is Social and Emotional Learning?.

1.48k views • 21 slides

Social Emotional Learning and Peacemaking

Social Emotional Learning and Peacemaking. An Introduction training designed by Peace Games www.peacegames.org. Goals. To introduce Social Emotional Learning (SEL) using a combination of theoretical foundations and practical application

463 views • 23 slides

Social / Emotional / Behavioral (SEB) Learning

Social / Emotional / Behavioral (SEB) Learning. What’s new in the SEB world?. Early Learning Programs Middle Schools. Early Learning. Middle School. …at the elementary level…. Student Learning Expectations (SLEs). I Can Statements. Alignment with Student Progress Report.

281 views • 14 slides

Improving the Odds. Social-Emotional Learning. Linda E. Miller Iowa Department of Education Meeting of the UEN – Middle School Administrators November 10, 2004 Council Bluffs, Iowa. Results for Iowa Youth. All youth are: successful in school; healthy and socially competent;

647 views • 46 slides

477 views • 15 slides

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Social and Emotional Learning

Published by Gwenda French Modified over 9 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Social and Emotional Learning"— Presentation transcript:

GUIDELINES on INCORPORATING SOCIAL EMOTIONAL LEARNING into ACADEMIC SUPPORT Anne L. Gilligan, M.P.H. Safe and Healthy School Specialist Learning Support.

Afterschool Programs That Follow Evidence- based Practices to Promote Social and Emotional Development Are Effective Roger P. Weissberg, University of.

The Core Competencies for Youth Development Professionals were developed with leadership from the OPEN Initiative, Missouri Afterschool Network (MASN),

Parents as Partners in Education

Social and Emotional Learning (SEL): For School and Life Success

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGISTS Helping children achieve their best. In school. At home. In life. National Association of School Psychologists.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning Social and Emotional Learning for School and Life Success Presenter School/District.

THE FOUNDATION FOR STUDENT SUCCESS IN SCHOOL, WORK, AND LIFE

Social and Emotional Learning for School and Life Success: SEL 101

PACT/TPAC and the social- emotional dimensions of teaching and learning: what can we assess? Presentors Nancy L. Markowitz, Professor Director, SJSU Center.

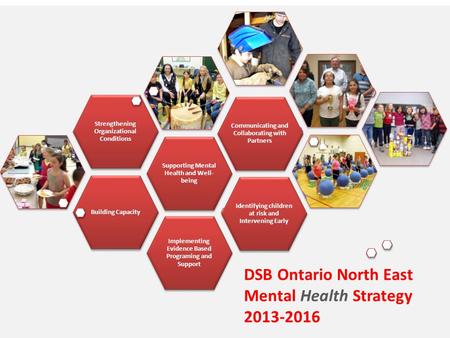

Building Capacity Implementing Evidence Based Programing and Support Strengthening Organizational Conditions Supporting Mental Health and Well- being Communicating.

Social and Emotional Learning in Schools Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl Shelley Hymel TEO Orientation, August 26, 2014.