News from the Columbia Climate School

Six Tough Questions About Climate Change

Whenever the focus is on climate change, as it is right now at the Paris climate conference , tough questions are asked concerning the costs of cutting carbon emissions, the feasibility of transitioning to renewable energy, and whether it’s already too late to do anything about climate change. We posed these questions to Laura Segafredo , manager for the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project . The decarbonization project comprises energy research teams from 16 of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitting countries that are developing concrete strategies to reduce emissions in their countries. The Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project is an initiative of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network .

- Will the actions we take today be enough to forestall the direct impacts of climate change? Or is it too little too late?

There is still time and room for limiting climate change within the 2˚C limit that scientists consider relatively safe, and that countries endorsed in Copenhagen and Cancun. But clearly the window is closing quickly. I think that the most important message is that we need to start really, really soon, putting the world on a trajectory of stabilizing and reducing emissions. The temperature change has a direct relationship with the cumulative amount of emissions that are in the atmosphere, so the more we keep emitting at the pace that we are emitting today, the more steeply we will have to go on a downward trajectory and the more expensive it will be.

Today we are already experiencing an average change in global temperature of .8˚. With the cumulative amount of emissions that we are going to emit into the atmosphere over the next years, we will easily reach 1.5˚ without even trying to change that trajectory.

Two degrees might still be doable, but it requires significant political will and fast action. And even 2˚ is a significant amount of warming for the planet, and will have consequences in terms of sea level rise, ecosystem changes, possible extinctions of species, displacements of people, diseases, agriculture productivity changes, health related effects and more. But if we can contain global warming within those 2˚, we can manage those effects. I think that’s really the message of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports—that’s why the 2˚ limit was chosen, in a sense. It’s a level of warming where we can manage the risks and the consequences. Anything beyond that would be much, much worse.

- Will taking action make our lives better or safer, or will it only make a difference to future generations?

It will make our lives better and safer for sure. For example, let’s think about what it means to replace a coal power plant with a cleaner form of energy like wind or solar. People that live around the coal power plant are going to have a lot less air pollution, which means less asthma for children, and less time wasted because of chronic or acute diseases. In developing countries, you’re talking about potentially millions of lives saved by replacing dirty fossil fuel based power generation with clean energy.

It will also have important consequences for agricultural productivity. There’s a big risk that with the concentration of carbon and other gases in the atmosphere, agricultural yields will be reduced, so preventing that means more food for everyone.

And then think about cities. If you didn’t have all that pollution from cars, we could live in cities that are less noisy, where the air’s much better, and have potentially better transportation. We could live in better buildings where appliances are more efficient. And investing in energy efficiency would basically leave more money in our pockets. So there are a lot of benefits that we can reap almost immediately, and that’s without even considering the biggest benefit—leaving a planet in decent condition for future generations.

- How will measures to cut carbon emissions affect my life in terms of cost?

To build a climate resilient economy, we need to incorporate the three pillars of energy system transformation that we focus on in all the deep decarbonization pathways. Number one is improving energy efficiency in every part of the economy—buildings, what we use inside buildings, appliances, industrial processes, cars…everything you can think of can perform the same service, but using less energy. What that means is that you will have a slight increase in the price in the form of a small investment up front, like insulating your windows or buying a more efficient car, but you will end up saving a lot more money over the life of the equipment in terms of decreased energy costs.

The second pillar is making electricity, the power sector, carbon-free by replacing dirty power generation with clean power sources. That’s clearly going to cost a little money, but those costs are coming down so quickly. In fact there are already a lot of clean technologies that are at cost parity with fossil fuels— for example, onshore wind is already as competitive as gas—and those costs are only coming down in the future. We can also expect that there are going to be newer technologies. But in any event, the fact that we’re going to use less power because of the first pillar should actually make it a wash in terms of cost.

The Australian deep decarbonization teams have estimated that even with the increased costs of cleaner cars, and more efficient equipment for the home, etc., when the power system transitions to where it’s zero carbon, you still have savings on your energy bills compared to the previous situation.

The third pillar that we think about are clean fuels, essentially zero-carbon fuels. So we either need to electrify everything— like cars and heating, once the power sector is free of carbon—or have low-carbon fuels to power things that cannot be electrified, such as airplanes or big trucks. But once you have efficiency, these types of equipment are also more efficient, and you should be spending less money on energy.

Saving money depends on the three pillars together, thinking about all this as a whole system.

- Given that renewable sources provide only a small percentage of our energy and that nuclear power is so expensive, what can we realistically do to get off fossil fuels as soon as possible?

There are a lot of studies that have been done for the U.S. and for Europe that show that it’s very realistic to think of a power sector that is almost entirely powered by renewables by 2050 or so. It’s actually feasible—and this considers all the issues with intermittency, dealing with the networks, and whatever else represents a technological barrier—that’s all included in these studies. There’s also the assumption that energy storage, like batteries, will be cheaper in the future.

That is the future, but 2050 is not that far away. 35 years for an energy transition is not a long time. It’s important that this transition start now with the right policy incentives in place. We need to make sure that cars are more efficient, that buildings are more efficient, that cities are built with more public transit so less fossil fuels are needed to transport people from one place to another.

I don’t want people to think that because we’re looking at 2050, that means that we can wait—in order to be almost carbon free by 2050, or close to that target, we need to act fast and start now.

- Will the remedies to climate change be worse than the disease? Will it drive more people into poverty with higher costs?

I actually think the opposite is true. If we just let climate go the way we are doing today by continuing business as usual, that will drive many people into poverty. There’s a clear relationship between climate change and changing weather patterns, so more significant and frequent extreme weather events, including droughts, will affect the livelihoods of a large portion of the world population. Once you have droughts or significant weather events like extreme precipitation, you tend to see displacements of people, which create conflict, and conflict creates disease.

I think Syria is a good example of the world that we might be going towards if we don’t do anything about climate change. Syria is experiencing a once-in-a-century drought, and there’s a significant amount of desertification going on in those areas, so you’re looking at more and more arid areas. That affects agriculture, so people have moved from the countryside to the cities and that has created a lot of pressure on the cities. The conflict in Syria is very much related to the drought, and the drought can be ascribed to climate change.

And consider the ramifications of the Syrian crisis: the refugee crisis in Europe, terrorism, security concerns and 7 million-plus people displaced. I think that that’s the world that we’re going towards. And in a world like that, when you have to worry about people being safe and alive, you certainly cannot guarantee wealth and better well-being, or education and health.

- So finally, doing what needs to be done to combat climate change all comes down to political will?

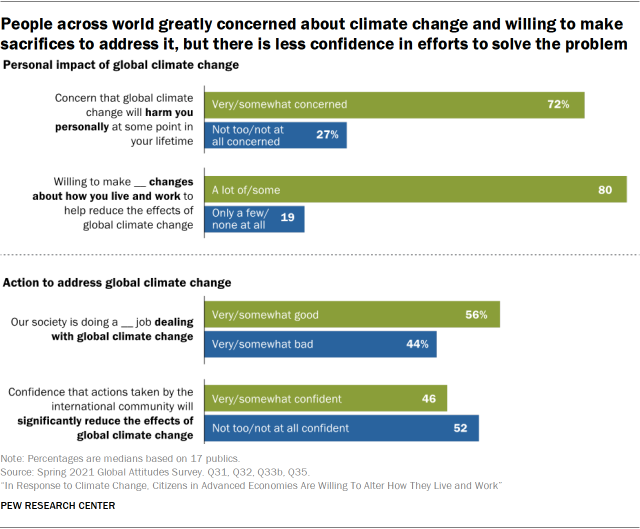

The majority of the American public now believe that climate change is real, that it’s human induced and that we should do something about it.

But there’s seems to be a disconnect between what these numbers seem to indicate and what the political discourse is like… I can’t understand it, yet it seems to be the situation.

I’m a little concerned because other more immediate concerns like terrorism and safety always come first. Because the effects of climate change are going to be felt a little further away, people think that we can always put it off. The Department of Defense, its top-level people, have made the connection between climate change and conflict over the next few decades. That’s why I would argue that Syria is actually a really good example to remind us that if we are experiencing security issues today, it’s also because of environmental problems. We cannot ignore them.

The reality is that we need to do something about climate change fast—we don’t have time to fight this over the next 20 years. We have to agree on this soon and move forward and not waste another 10 years debating.

Read the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project 2015 report . The full report will be released Dec. 2.

Laura Segafredo was a senior economist at the ClimateWorks Foundation, where she focused on best practice energy policies and their impact on emission trajectories. She was a lead author of the 2012 UNEP Emissions Gap Report and of the Green Growth in Practice Assessment Report. Before joining ClimateWorks, Segafredo was a research economist at Electricité de France in Paris.

She obtained her Ph.D. in energy studies and her BA in economics from the University of Padova (Italy), and her MSc in economics from the University of Toulouse (France).

Related Posts

Solar Geoengineering To Cool the Planet: Is It Worth the Risks?

Army Veteran and Environmental Advocate: A Sustainability Science Student’s Journey to Columbia

Sustainable Development Program Hosts Annual Alumni Career Conversations Panel

Celebrate over 50 years of Earth Day with us all month long! Visit our Earth Day website for ideas, resources, and inspiration.

Many find low wages prohibits saving. Changing personal vehicles and heating systems costs. Will there be financial support for people on low wages?

The energy innovation and dividend bill has already been introduced in the house. It’s a carbon fee and dividend plan. The carbon fee rises every year and 100% of it goes back directly into the hands of the people by a check each month. This helps offset rising costs, especially for lower income folks.

81 cosponsors now Tell your rep in Congress to support this HR 763!

Results show that yields for all four crops grown at levels of carbon dioxide remaining at 2000 levels would experience severe declines in yield due to higher temperatures and drier conditions. But when grown at doubled carbon dioxide levels, all four crops fare better due to increased photosynthesis and crop water productivity, partially offsetting the impacts from those adverse climate changes. For wheat and soybean crops, in terms of yield the median negative impacts are fully compensated, and rice crops recoup up to 90 percent and maize up to 60 percent of their losses.

When is Russia, China, and Mexico going to work toward a better environment instead of the United States trying to do it all? They continue to pollute like they have for years. Who is going to stop the deforestation of the rain forest?

I’m curious if climate change has any effect on seismic activity. It seems with ice melting on the poles and increasing water dispersement and temp of that water, it might cause the plates to shift to compensate. Is there any evidence of this?

this isn’t because of doldrums or jet streams. the pattern keeps having the same action. we must save trees :3

How long do we have, before it’s too late?

Climate Change isn’t nearly as big of a deal as everyone makes it out to be. Meaning no disrespect to the author, but I really don’t see how this is something that we should be worrying about given that one human recycling their soda cans or getting their old phone refurbished rather than dumping it isn’t going to restore the polar ice caps or lower the temperature of the planet. And supposedly agriculture is the problem, but I point-blank refuse to give up my beef night, or bacon and eggs for breakfast on Saturdays. Also, nuclear power is supposed to be a solution, but the building of the power plants is going to add more greenhouse gases than the plant will take out. The whole planet needs a reality check. Earth isn’t going to explode because it’s slightly hotter than it used to be!

Thank you and I need in your help

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter →

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- TikTok’s fate

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- 9 questions about climate change you were too embarrassed to ask

Basic answers to basic questions about global warming and the future climate.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: 9 questions about climate change you were too embarrassed to ask

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/55048475/North_America_from_low_orbiting_satellite_Suomi_NPP.0.jpg)

This explainer was updated by Umair Irfan in December 2018 and draws heavily from a card stack written by Brad Plumer in 2015. Brian Resnick contributed the section on the Paris climate accord in 2017.

There’s a vast and growing gap between the urgency to fight climate change and the policies needed to combat it.

In 2018, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that it is possible to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius this century, but the world may have as little as 12 years left to act. The US government’s National Climate Assessment , with input from NASA, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Pentagon, also reported that the consequences of climate change are already here, ranging from nuisance flooding to the spread of mosquito-borne viruses into what were once colder climates. Left unchecked, warming will cost the US economy hundreds of billions of dollars.

However, these facts have failed to register with the Trump administration, which is actively pushing policies that will increase the emissions of heat-trapping gases.

Ever since he took office, President Donald Trump has rejected or undermined President Barack Obama’s signature climate achievements: the Paris climate agreement; the Clean Power Plan , the main domestic policy for limiting greenhouse gas emissions; and fuel economy standards , which target transportation, the largest US source of greenhouse gases.

At the same time, the Trump administration has aggressively boosted fossil fuels: opening unprecedented swaths of public lands to mining and drilling , attempting to bail out foundering coal power plants , and promoting hydrocarbon exploitation at climate change conferences .

Trump has also appointed climate change skeptics to key positions. Quietly, officials at these and other science agencies have been removing the words “climate change” from government websites and press releases.

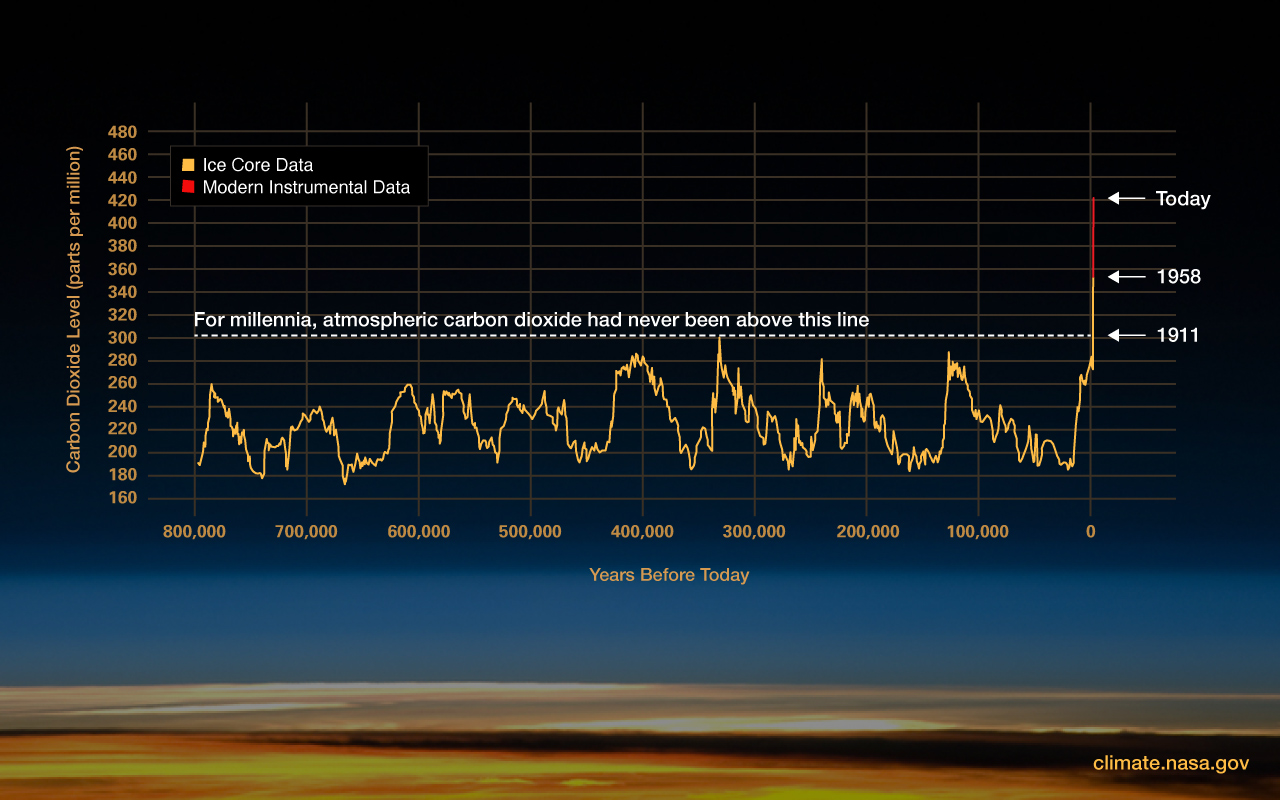

Yet the evidence for humanity’s role in changing the climate continues to mount, and its consequences are increasingly difficult to ignore. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations now top 408 parts per million, a threshold the planet hasn’t seen in millions of years . Greenhouse gas emissions reached a record high in 2018. Disasters worsened by climate change have taken hundreds of lives, destroyed thousands of homes, and cost billions of dollars.

The big questions now are how these ongoing changes in the climate will reverberate throughout the rest of the world, and what we should do about them. The answers bridge decades of research across geology, economics, and social science, which have been confounded by uncertainty and obscured by jargon. That’s why it can be a bit daunting to join the discussion for the first time, or to revisit the conversation after a hiatus.

To help, we’ve provided answers to some fundamental questions about climate change you may have been afraid to ask.

1) What is global warming?

In short: The world is getting hotter, and humans are responsible.

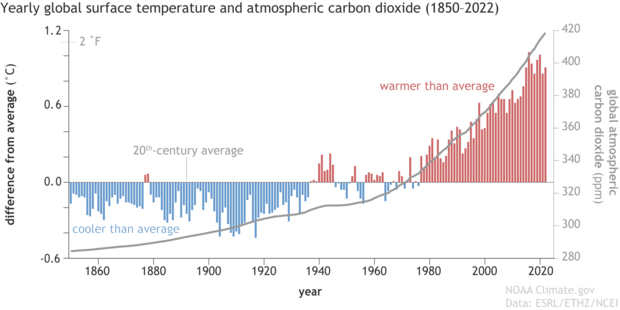

Yes, the planet’s temperature has changed before, but it’s the rise in average temperature of the Earth's climate system since the late 19th century, the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, that’s important here. Temperatures over land and ocean have gone up 0.8° to 1° Celsius (1.4° to 1.8° Fahrenheit), on average, in that span:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10346257/Screen_Shot_2018_03_05_at_10.29.11_AM.png)

Many people use the term “climate change” to describe this rise in temperatures and the associated effects on the Earth's climate. (The shift from the term “global warming” to “climate change” was also part of a deliberate messaging effort by a Republican pollster to undermine support for environmental regulations.)

Like detectives solving a murder, climate scientists have found humanity’s fingerprints all over the planet’s warming, with the overwhelming majority of the evidence pointing to the extra greenhouse gases humans have put into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide trap heat at the Earth’s surface, preventing that heat from escaping back out into space too quickly. When we burn coal, natural gas, or oil for energy, or when we cut down forests that usually soak up greenhouse gases, we add even more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, so the planet warms up.

Global warming also refers to what scientists think will happen in the future if humans keep adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

Though there is a steady stream of new studies on climate change, one of the most robust aggregations of the science remains the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s fifth assessment report from 2013. The IPCC is convened by the United Nations, and the report draws on more than 800 expert authors. It projects that temperatures could rise at least 2°C (3.6°F) by the end of the century under many plausible scenarios — and possibly 4°C or more. A more recent study by scientists in the United Kingdom found a narrower range of expected temperatures if atmospheric carbon dioxide doubled, rising between 2.2°C and 3.4°C.

Many experts consider 2°C of warming to be unacceptably high , increasing the risk of deadly heat waves, droughts, flooding, and extinctions. Rising temperatures will drive up global sea levels as the world’s glaciers and ice sheets melt. Further global warming could affect everything from our ability to grow food to the spread of disease.

That’s why the IPCC put out another report in 2018 comparing 2°C of warming to a scenario with 1.5°C of warming . The researchers found that this half-degree difference is actually pretty important, since every bit of warming matters. Between the two outlooks, less warming means fewer people will have to move from coastal areas, natural weather events will be less severe, and economies will take a smaller hit.

However, limiting warming would likely require a complete overhaul of our energy system. Fossil fuels currently provide just over 80 percent of the world’s energy. To zero out emissions this century, we’d have to replace most of that with low-carbon sources like wind, solar, nuclear, geothermal, or carbon capture.

Beyond that, we may have to electrify everything that uses energy and start pulling greenhouse gases straight from the air. And to get on track for 1.5°C of warming, the world would have to halve greenhouse gas emissions from current levels by 2030.

That’s a staggering task, and there are huge technological and political hurdles standing in the way. As such, the world's nations have been slow to act on global warming — many of the existing targets for curbing greenhouse gas emissions are too weak , yet many countries are falling short of even these modest goals.

2) How do we know global warming is real?

The simplest way is through temperature measurements. Agencies in the United States, Europe, and Japan have independently analyzed historical temperature data and reached the same conclusion: The Earth’s average surface temperature has risen roughly 0.8° Celsius (1.4° Fahrenheit) since the early 20th century.

But that’s not the only clue. Scientists have also noted that glaciers and ice sheets around the world are melting. Satellite observations since the 1970s have shown warming in the lower atmosphere. There’s more heat in the ocean, causing water to expand and sea levels to rise. Plants are flowering earlier in many parts of the world. There’s more humidity in the atmosphere. Here’s a summary from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8613575/HowDoWeKnowGWisReal.png)

These are all signs that the Earth really is getting warmer — and that it’s not just a glitch in the thermometers. That explains why climate scientists say things like , “Warming in the climate system is unequivocal.” They’re really confident about this one.

3) How do we know humans are causing global warming?

Climate scientists say they are more than 95 percent certain that human influence has been the dominant cause of global warming since 1950. They’re about as sure of this as they are that cigarette smoke causes cancer.

Why are they so confident? In part because they have a good grasp of how greenhouse gases can warm the planet, in part because the theory fits the available evidence, and in part because alternate theories have been ruled out. Let's break it down in six steps:

1) Scientists have long known that greenhouse gases in the atmosphere — such as carbon dioxide, methane, or water vapor — absorb certain frequencies of infrared radiation and scatter them back toward the Earth. These gases essentially prevent heat from escaping too quickly back into space, trapping that radiation at the surface and keeping the planet warm.

2) Climate scientists also know that concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have grown significantly since the Industrial Revolution. Carbon dioxide has risen 45 percent . Methane has risen more than 200 percent . Through some relatively straightforward chemistry and physics , scientists can trace these increases to human activities like burning oil, gas, and coal.

3) So it stands to reason that more greenhouse gases would lead to more heat. And indeed, satellite measurements have shown that less infrared radiation is escaping out into space over time and instead returning to the Earth’s surface. That’s strong evidence that the greenhouse effect is increasing.

4) There are other human fingerprints that suggest increased greenhouse gases are warming the planet. For instance, back in the 1960s, simple climate models predicted that global warming caused by more carbon dioxide would lead to cooling in the upper atmosphere (because the heat is getting trapped at the surface). Later satellite measurements confirmed exactly that . Here are a few other similar predictions that have also been confirmed.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8613609/HumansGW.jpg)

5) Meanwhile, climate scientists have ruled out other explanations for the rise in average temperatures over the past century. To take one example: Solar activity can shift from year to year, affecting the Earth's climate. But satellite data shows that total solar irradiance has declined slightly in the past 35 years, even as the Earth has warmed.

6) More recent calculations have shown that it’s impossible to explain the temperature rise we’ve seen in the past century without taking the increase in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into account. Natural causes, like the sun or volcanoes, have an influence, but they’re not sufficient by themselves.

Ultimately, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded that most of the warming since 1951 has been due to human activities. The Earth’s climate can certainly fluctuate from year to year due to natural forces (including oscillations in the Pacific Ocean, such as El Niño ). But greenhouse gases are driving the larger upward trend in temperatures.

And as the Climate Science Special Report , released by 13 US federal agencies in November 2017, put it, “For the warming over the last century, there is no convincing alternative explanation supported by the extent of the observational evidence.”

More: This chart breaks down all the different factors affecting the Earth’s average temperature. And there’s much more detail in the IPCC’s report , particularly this section and this one .

4) How has global warming affected the world so far?

Here’s a list of ongoing changes that climate scientists have concluded are likely linked to global warming, as detailed by the IPCC here and here .

Higher temperatures: Every continent has warmed substantially since the 1950s. There are more hot days and fewer cold days, on average, and the hot days are hotter.

Heavier storms and floods : The world’s atmosphere can hold more moisture as it warms. As a result, the overall number of heavier storms has increased since the mid-20th century, particularly in North America and Europe (though there’s plenty of regional variation). Scientists reported in December that at least 18 percent of Hurricane Harvey’s record-setting rainfall over Houston in August was due to climate change.

Heat waves: Heat waves have become longer and more frequent around the world over the past 50 years, particularly in Europe, Asia, and Australia.

Shrinking sea ice: The extent of sea ice in the Arctic, always at its maximum in winter, has shrunk since 1979, by 3.3 percent per decade. Summer sea ice has dwindled even more rapidly, by 13.2 percent per decade. Antarctica has seen recent years with record growth in sea ice, but it’s a very different environment than the Arctic, and the losses in the north far exceed any gains at the South Pole, so total global sea ice is on the decline:

Global, Arctic and Antarctic Sea Ice Area Spiral February 2018 #GlobalWarming #ClimateChange pic.twitter.com/gayoLFSJ5u — Kevin Pluck (@kevpluck) March 1, 2018

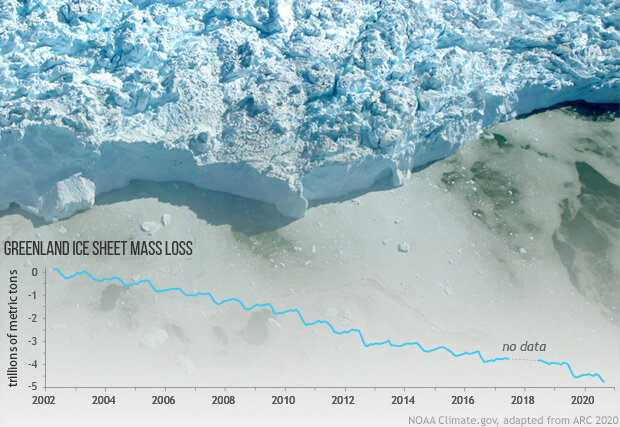

Shrinking glaciers and ice sheets : Glaciers around the world have, on average, been losing ice since the 1970s. In some areas, that is reducing the amount of available freshwater. The ice sheet on Greenland, which would raise global sea levels by 25 feet if it all melted, is declining, with some sections experiencing a sudden surge in the melt rate. The Antarctic ice sheet is also getting smaller, but at a much slower rate .

Sea level rise: Global sea levels rose 9.8 inches (25 centimeters) in the 19th and 20th centuries, after 2,000 years of relatively little change , and the pace is speeding up . Sea level rise is caused by both the thermal expansion of the oceans — as water warms up, it expands — and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets (but not sea ice).

Food supply: A hotter climate can be both good for crops (it lengthens the growing season, and more carbon dioxide can increase photosynthesis) and bad for crops (excess heat can damage plants). The IPCC found that global warming was currently benefiting crops in some high-latitude areas but that negative effects are becoming increasingly common worldwide. In areas like California, crop yields are estimated to decline 40 percent by 2050.

Shifting species: Many land and marine species have had to shift their geographic ranges in response to warmer temperatures. So far, several extinctions have been linked to global warming, such as certain frog species in Central America.

Warmer winters: In general, winters are warming faster than summers . Average low temperatures are rising all over the world. In some cases, these temperatures are climbing above the freezing point of water. We’re already seeing massive declines in snow accumulation in the United States, which can paradoxically increase flood, drought, and wildfire risk — as water that would ordinarily dispatch slowly over the course of a season instead flows through a region all at once.

Debated impacts

Here are a few other ways the Earth’s climate has been changing — but scientists are still debating whether and how they’re linked to global warming:

Droughts have become more frequent and more intense in some parts of the world — such as the American Southwest, Mediterranean Europe, and West Africa — though it’s hard to identify a clear global trend. In other parts of the world, such as the Midwestern United States and Northwestern Australia, droughts appear to have become less frequent. A recent study shows that, globally, the time between droughts is shrinking and more areas are affected by drought and taking longer to recover from them.

Hurricanes have clearly become more intense in the North Atlantic Ocean since 1970, the IPCC says. But it’s less clear whether global warming is driving this. 2017 was an exceptionally bad year for Atlantic hurricanes in terms of strength and damage. And while scientists are still uncertain whether they were a fluke or part of a trend, they are warning we should treat it as a baseline year. There doesn’t yet seem to be any clear trajectory for tropical cyclones worldwide.

5) What impacts will global warming have in the future?

It depends on how much the planet actually heats up. The changes associated with 4° Celsius (or 7.2° Fahrenheit) of warming are expected to be more dramatic than the changes associated with 2°C of warming.

Here’s a basic rundown of big impacts we can expect if global warming continues, via the IPCC ( here and here ).

Hotter temperatures: If emissions keep rising unchecked, then global average surface temperatures will be at least 2°C higher (3.6°F) than preindustrial levels by 2100 — and possibly 3°C or 4°C or more.

Higher sea level rise: The expert consensus is that global sea levels will rise somewhere between 0.2 and 2 meters by the end of the century if global warming continues unchecked (that’s between 0.6 and 6.6 feet). That’s a wide range, reflecting some of the uncertainties scientists have in how ice will melt. In specific regions like the Eastern United States, sea level rise could be even higher, and around the world, the rate of rise is accelerating .

Heat waves: A hotter planet will mean more frequent and severe heat waves .

Droughts and floods: Across the globe, wet seasons are expected to become wetter, and dry seasons drier. As the IPCC puts it , the world will see “more intense downpours, leading to more floods, yet longer dry periods between rain events, leading to more drought.”

Hurricanes: It’s not yet clear what impact global warming will have on tropical cyclones. The IPCC said it was likely that tropical cyclones would get stronger as the oceans heat up, with faster winds and heavier rainfall. But the overall number of hurricanes in many regions was likely to “either decrease or remain essentially unchanged.”

Heavier storm surges: Higher sea levels will increase the risk of storm surges and flooding when storms do hit.

Agriculture: In many parts of the world, the mix of increased heat and drought is expected to make food production more difficult. The IPCC concluded that global warming of 1°C or more could start hurting crop yields for wheat, corn, and rice by the 2030s, especially in the tropics. (This wouldn’t be uniform, however; some crops may benefit from mild warming, such as winter wheat in the United States.)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8613683/WGII_AR5_Fig7_4.jpg)

Extinctions: As the world warms, many plant and animal species will need to shift habitats at a rapid rate to maintain their current conditions. Some species will be able to keep up; others likely won’t. The Great Barrier Reef, for instance, may not be able to recover from major recent bleaching events linked to climate change. The National Research Council has estimated that a mass extinction event “could conceivably occur before the year 2100.”

Long-term changes: Most of the projected changes above will occur in the 21st century. But temperatures will keep rising after that if greenhouse gas levels aren’t stabilized. That increases the risk of more drastic longer-term shifts. One example: If West Antarctica’s ice sheet started crumbling, that could push sea levels up significantly. The National Research Council in 2013 deemed many of these rapid climate surprises unlikely this century but a real possibility further into the future.

6) What happens if the world heats up more drastically — say, 4°C?

The risks of climate change would rise considerably if temperatures rose 4° Celsius (7.2° Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels — something that’s possible if greenhouse gas emissions keep rising at their current rate.

The IPCC says 4°C of global warming could lead to “substantial species extinctions,” “large risks to global and regional food security,” and the risk of irreversibly destabilizing Greenland’s massive ice sheet.

One huge concern is food production: A growing number of studies suggest it would become significantly more difficult for the world to grow food with 3°C or 4°C of global warming. Countries like Bangladesh, Egypt, Vietnam, and parts of Africa could see large tracts of farmland turn unusable due to rising seas. Scientists are also concerned about crops getting less nutritious due to rising CO2.

Humans could struggle to adapt to these conditions. Many people might think the impacts of 4°C of warming will simply be twice as bad as those of 2°C. But as a 2013 World Bank report argued, that’s not necessarily true. Impacts may interact with each other in unpredictable ways. Current agriculture models, for instance, don’t have a good sense of what will happen to crops if increased heat waves, droughts, new pests and diseases, and other changes all start to combine.

“Given that uncertainty remains about the full nature and scale of impacts,” the World Bank report said, “there is also no certainty that adaptation to a 4°C world is possible.” Its conclusion was blunt: “The projected 4°C warming simply must not be allowed to occur.”

7) What do climate models say about the warming that could actually happen in the coming decades?

That depends on your faith in humanity.

Climate models depend on not only complicated physics but the intricacies of human behavior over the entire planet.

Generally, the more greenhouse gases humanity pumps into the atmosphere, the warmer it will get. But scientists aren’t certain how sensitive the global climate system is to increases in greenhouse gases. And just how much we might emit over the coming decades remains an open question, depending on advances in technology and international efforts to cut emissions.

The IPCC groups these scenarios into four categories of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations known as Representative Concentration Pathways . They serve as standard benchmarks for evaluating climate models, but they also have some assumptions baked in .

RCP 2.6, also called RCP 3PD, is the scenario with very low greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. It bets on declining oil use, a population of 9 billion by 2100, increasing energy efficiency, and emissions holding steady until 2020, at which point they’ll decline and even go negative by 2100. This is, to put it mildly, very optimistic.

The next tier up is RCP 4.5, which still banks on ambitious reductions in emissions but anticipates an inflection point in the emissions rate around 2040. RCP 6 expects emissions to increase 75 percent above today’s levels before peaking and declining around 2060 as the world continues to rely heavily on fossil fuels.

The highest tier, RCP 8.5, is the pessimistic business-as-usual scenario, anticipating no policy changes nor any technological advances. It expects a global population of 12 billion and triple the rate of carbon dioxide emissions compared to today by 2100.

Here’s how greenhouse gas emissions under each scenario stack up next to each other:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10350069/RCP_IEA_Emissions.jpg)

And here’s what that means for global average temperatures, assuming that a doubling of carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere leads to 3°C of warming:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10350081/3C_Sensitivity.jpg)

As you can see, RCP 3PD is the only trajectory that keeps the planet below 2°C of warming. Recall what it would take to keep emissions in line with this pathway and you’ll understand the enormity of the challenge of meeting this goal.

8) How do we stop global warming?

The world’s nations would need to cut their greenhouse gas emissions by a lot. And even that wouldn’t stop all global warming.

For example, let’s say we wanted to limit global warming to below 2°C. To do that, the IPCC has calculated that annual greenhouse gas emissions would need to drop at least 40 to 70 percent by midcentury.

Emissions would then have to keep falling until humans were hardly emitting any extra greenhouse gases by the end of the century. We’d also have to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere .

Cutting emissions that sharply is a daunting task. Right now, the world gets 87 percent of its primary energy from fossil fuels: oil, gas, and coal. By contrast, just 13 percent of the world’s primary energy is “low carbon”: a little bit of wind and solar power, some nuclear power plants, a bunch of hydroelectric dams. That’s one reason global emissions keep rising each year.

To stay below 2°C, that would all need to change radically. By 2050, the IPCC notes, the world would need to triple or even quadruple the share of clean energy it uses — and keep scaling it up thereafter. Second, we’d have to get dramatically more efficient at using energy in our homes, buildings, and cars. And stop cutting down forests. And reduce emissions from agriculture and from industrial processes like cement manufacturing.

The IPCC also notes that this task becomes even more difficult the longer we put it off, because carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases will keep piling up in the atmosphere in the meantime, and the cuts necessary to stay below the 2°C limit become more severe.

9) What are we actually doing to fight climate change?

A global problem requires global action, but with climate change, there is a yawning gap between ambition and action.

The main international effort is the 2015 Paris climate accord, of which the United States is the only country in the world that wants out . The deal was hammered out over weeks of tense negotiations and weighs in at 31 pages . What it does is actually pretty simple.

The backbone is the global target of keeping global average temperatures from rising 2°C (compared to temperatures before the Industrial Revolution) by the end of the century. Beyond 2 degrees, we risk dramatically higher seas, changes in weather patterns, food and water crises, and an overall more hostile world.

Critics have argued that the 2-degree mark is arbitrary, or even too low , to make a difference. But it’s a starting point, a goal that, before Paris, the world was on track to wildly miss.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7291239/global_CO2_emissions_graphic.jpg)

Paris is voluntary

To accomplish this 2-degree goal, the accord states that countries should strive to reach peak emissions “as soon as possible.” (Currently, we’re on track to hit peak emissions around 2030 or later , which will likely be too late.)

But the agreement doesn’t detail exactly how these countries should do that. Instead, it provides a framework for getting momentum going on greenhouse gas reduction, with some oversight and accountability. For the US, the pledge involves 26 to 28 percent reductions by 2025. (Under Trump’s current policies, that goal is impossible .)

There’s also no defined punishment for breaking it. The idea is to create a culture of accountability (and maybe some peer pressure) to get countries to step up their climate game.

In 2020, delegates are supposed to reconvene and provide updates about their emission pledges and report on how they’re becoming more aggressive on accomplishing the 2-degree goal.

However, many countries are already falling behind on their climate change commitments, and some, like Germany, are giving up on their near-term targets.

Paris asks richer countries to help out poorer countries

There’s a fundamental inequality when it comes to global emissions. Rich countries have plundered and burned huge amounts of fossil fuels and gotten rich from them. Poor countries seeking to grow their economies are now being admonished for using the same fuels. Many low-lying poor countries also will be among the first to bear the worst impacts of climate change.

The main vehicle for rectifying this is the Green Climate Fund , via which richer countries, like the US, are supposed to send $100 billion a year in aid and financing by 2020 to the poorer countries. The United States’ share was $3 billion , but with President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris accord, this goal is unlikely to be met.

The agreement matters because we absolutely need momentum on this issue

The Paris agreement is largely symbolic, and it will live on even though Trump is aiming to pull the US out. But, as Jim Tankersley wrote for Vox , “the accord will be weakened, and, much more importantly, so will the fragile international coalition” around climate change.

We’re already seeing the Paris agreement lose steam. At a follow-up climate meeting this year in Katowice, Poland , negotiators forged an agreement on measuring and verifying their progress in cutting greenhouse gases, but left many critical questions of how to achieve these reductions unanswered.

But the Paris accord isn’t the only international climate policy game in town

There are regional international climate efforts like the European Union’s Emissions Trading System . However, the most effective global policy at keeping warming in check to date doesn’t have to do with climate change, at least on the surface.

The 1987 Montreal Protocol , which was convened by countries to halt the destruction of the ozone layer, had a major side effect of averting warming. In fact, it’s been the single most effective effort humanity has undertaken to fight climate change. Since many of the substances that eat away at the ozone layer are potent heat-trappers, limiting emissions of gases like chlorofluorocarbons has an outsize effect.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10354423/Screen_Shot_2017_11_27_at_2.33.42_PM.png)

And the Trump administration doesn’t appear as hostile to Montreal as it does to Paris. The White House may send the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol to the Senate for ratification, giving the new regulations the force of law. If implemented, the amendment would avert 0.5°C of warming by 2100.

Regardless of what path we choose, the key thing to remember is that we are going to pay for climate change one way or another. We have the opportunity now to address warming on our own terms, with investments in clean energy, moving people away from disaster-prone areas, and regulating greenhouse gas emissions. Otherwise, we’ll pay through diminished crop harvests, inundated coastlines, destroyed homes, lost lives, and an increasingly unlivable planet. Ignoring or stalling on climate change chooses the latter option by default. Our choices do matter, but we’re running out of time to make them.

F urther reading:

Avoiding catastrophic climate change isn’t impossible yet. Just incredibly hard.

Reckoning with climate change will demand ugly tradeoffs from environmentalists — and everyone else

Show this cartoon to anyone who doubts we need huge action on climate change

It’s time to start talking about “negative” carbon dioxide emissions

A history of the 2°C global warming target

Scientists made a detailed “roadmap” for meeting the Paris climate goals. It’s eye-opening.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

In This Stream

Trump withdraws the us from paris climate agreement.

- The rumors that Trump was changing course on the Paris climate accord, explained

Next Up In Science

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

The AI grift that can literally poison you

Everything’s a cult now

We could be heading into the hottest summer of our lives

How today’s antiwar protests stack up against major student movements in history

What the backlash to student protests over Gaza is really about

You need $500. How should you get it?

We're moving!

Understanding our planet to benefit humankind

News & features.

What Is Climate Change?

How do we know climate change is real, why is climate change happening, what are the effects of climate change, what is being done to solve climate change, earth science in action.

More to Explore

Ask nasa climate.

People Profiles

Images of Change

Before-and-after images of earth, climate change resources, an extensive collection of global warming resources for media, educators, weathercasters, and public speakers..

- Images of Change Before-and-after images of Earth

- Global Ice Viewer Climate change's impact on ice

- Earth Minute Videos Animated video series illustrating Earth science topics

- Climate Time Machine Climate change in recent history

- Multimedia Vast library of images, videos, graphics, and more

- En español Creciente biblioteca de recursos en español

- For Educators Student and educator resources

- For Kids Webquests, Climate Kids, and more

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 February 2024

Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action

- Peter Andre ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8213-527X 1 ,

- Teodora Boneva ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4227-3686 2 ,

- Felix Chopra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7621-1045 3 &

- Armin Falk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7284-3002 2

Nature Climate Change volume 14 , pages 253–259 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

51k Accesses

2 Citations

1248 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Climate-change mitigation

- Psychology and behaviour

Mitigating climate change necessitates global cooperation, yet global data on individuals’ willingness to act remain scarce. In this study, we conducted a representative survey across 125 countries, interviewing nearly 130,000 individuals. Our findings reveal widespread support for climate action. Notably, 69% of the global population expresses a willingness to contribute 1% of their personal income, 86% endorse pro-climate social norms and 89% demand intensified political action. Countries facing heightened vulnerability to climate change show a particularly high willingness to contribute. Despite these encouraging statistics, we document that the world is in a state of pluralistic ignorance, wherein individuals around the globe systematically underestimate the willingness of their fellow citizens to act. This perception gap, combined with individuals showing conditionally cooperative behaviour, poses challenges to further climate action. Therefore, raising awareness about the broad global support for climate action becomes critically important in promoting a unified response to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

The economic commitment of climate change

Worldwide divergence of values

Climate damage projections beyond annual temperature

The world’s climate is a global common good and protecting it requires the cooperative effort of individuals across the globe. Consequently, the ‘human factor’ is critical and renders the behavioural science perspective on climate change indispensable for effective climate action. Despite its importance, limited knowledge exists regarding the willingness of the global population to cooperate and act against climate change 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 . To fill this gap, we designed and conducted a globally representative survey in 125 countries, with the aim of examining the potential for successful global climate action. The central question we seek to answer is to what extent are individuals around the globe willing to contribute to the common good, and how do people perceive other people’s willingness to contribute (WTC)?

Drawing on a multidisciplinary literature on the foundations of cooperation, our study focuses on four aspects that have been identified as critical in promoting cooperation in the context of common goods: the individual willingness to make costly contributions, the approval of pro-climate norms, the demand for political action and beliefs about the support of others. We start with exploring the individual willingness to make costly contributions to act against climate change, which is particularly relevant given that cooperation is costly and involves free-rider incentives 9 . Using a behaviourally validated measure, we assess the extent to which individuals around the globe are willing to contribute a share of their income, and which factors predict the observed cross-country variation.

Furthermore, the provision of common goods crucially depends on the existence and enforcement of social norms. These norms prescribe cooperative behaviour 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 and affect behaviour either through internalization (shame and guilt 16 ) or the enforcement of norms by fellow citizens (sanctions and approval 17 ). In our survey, we elicit support for pro-climate social norms and examine the extent to which such norms have emerged globally.

It is widely recognized that addressing common-good problems effectively necessitates institutions and concerted political action 18 , 19 , 20 . In democracies, the implementation of effective climate policies relies on popular support, and even in non-democratic societies, leaders remain attentive to prevailing political demands. Therefore, we also elicit the demand for political action as a critical input in the fight against climate change 21 .

Previous research in the behavioural sciences has shown that many individuals can be characterized as conditional cooperators 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 . This means that individuals are more likely to contribute to the common good when they believe others also contribute. We test this central psychological mechanism of cooperation using our data on actual and perceived WTC. Moreover, we investigate whether beliefs about others’ WTC are well calibrated or whether they are systematically biased. If beliefs are overly pessimistic, this would imply that the world is in a state of pluralistic ignorance 27 , where systematic misperceptions about others’ WTC hinder cooperation and reinforce further pessimism. In such an equilibrium, correcting beliefs holds tremendous potential for fostering cooperation 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 .

The global survey

To obtain globally representative evidence on the willingness to act against climate change, we designed the Global Climate Change Survey. The survey was administered as part of the Gallup World Poll 2021/2022 in a large and diverse set of countries ( N = 125) using a common sampling and survey methodology ( Methods ). The countries included in this study account for 96% of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, 96% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 92% of the global population. To ensure national representativeness, each country sample is randomly selected from the resident population aged 15 and above. Interviews were conducted via telephone (common in high-income countries) or face to face (common in low-income countries), with randomly drawn phone numbers or addresses. Most country samples include approximately 1,000 respondents, and the global sample comprises a total of 129,902 individuals.

To assess respondents’ willingness to incur a cost to act against climate change, we elicit their willingness to contribute a fraction of their income to climate action. More specifically, we ask respondents whether they would be ‘willing to contribute 1% of [their] household income every month to fight global warming’ (answered yes or no), and, if not, whether they would be willing to contribute a smaller amount (yes or no). To account for the substantial variation in income levels across countries, the question is framed in relative terms. Respondents’ answers thus reflect how strongly they value climate action relative to alternative uses of their income. The figure of 1% is deliberately chosen as it falls within the range of plausible previously reported estimates of climate change mitigation costs 32 , 33 .

Our WTC measure has been empirically validated and shown to predict incentivized pro-climate donation decisions ( Methods ). In a representative US sample 30 , respondents who state they would be willing to contribute 1% of their monthly income donate 43% more money to a climate charity ( P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test, N = 1,993; Supplementary Fig. 1 ) and are 21–39 percentage points more likely to avoid fossil-fuel-based means of transport (car and plane), restrict their meat consumption, use renewable energy or adapt their shopping behaviour (all P < 0.001 for two-sided t -tests, N = 1,996; Supplementary Table 1 ).

To measure respondents’ beliefs about other people’s WTC, we first tell respondents that we are surveying many other individuals in their country about their willingness to contribute 1% of their household income every month to fight global warming. We then ask respondents to estimate how many out of 100 other individuals in their country would be willing to contribute this amount, that is, possible answers range from 0 to 100.

To assess individual approval of pro-climate social norms, we ask respondents to indicate whether they think that people in their country ‘should try to fight global warming’ (answered yes or no). Following recent research on social norms 15 , 34 , the item elicits respondents’ views about what other people should do, that is, what kind of behaviour they consider normatively appropriate (so-called injunctive norms 10 ).

Finally, we measure demand for political action by asking respondents whether they think that their ‘national government should do more to fight global warming’ (answered yes or no). This item assesses the extent to which individuals regard their government’s current efforts as insufficient and sheds light on the potential for increased political action in the future.

The approval of pro-climate norms and the demand for political action are deliberately measured in a general manner to account for the fact that suitable concrete mitigation strategies may differ across countries. Our general measures strongly correlate with the approval of specific pro-climate norms and the demand for concrete policy measures ( Methods ). In a representative US sample, individuals who approve of the general norm to act against climate change are substantially more likely to state that individuals ‘should try to’ avoid fossil-fuel-based means of transport (car and plane), restrict their meat consumption, use renewable energy or adapt their shopping behaviour (correlation coefficients ρ between 0.35 and 0.51, all P < 0.001 for two-sided t -tests, N = 1,994; Supplementary Table 2 ). Similarly, the general demand for more political action is strongly correlated with demand for specific climate policies, such as a carbon tax on fossil fuels, regulatory limits on the CO 2 emissions of coal-fired plants, or funding for research on renewable energy ( ρ between 0.49 and 0.59, all P < 0.001 for two-sided t -tests, N = 1,996; Supplementary Table 3 ).

To ensure comparability across countries and cultures, professional translators translated the survey into the local languages following best practices in survey translation by using an elaborate multi-step translation procedure. The survey was extensively pre-tested in multiple countries of diverse cultural heritage to ensure that respondents with different cultural, economic and educational backgrounds could comprehend the questions in a comparable way. We deliberately refer to ‘global warming’ rather than ‘climate change’ throughout the survey to prevent confusion with seasonal changes in weather 35 , 36 , and provide all respondents with a brief definition of global warming to ensure a common understanding of the term.

A list of variables, definitions and sources is available in Methods . In all analyses, we use Gallup’s sampling weights, which were calculated by Gallup in multiple stages. A probability weight factor (base weight) was constructed to correct for unequal selection probabilities resulting from the stratified random sampling procedure. At the next step, the base weights were post-stratified to adjust for non-response and to match the weighted sample totals to known population statistics. The standard demographic variables used for post-stratification are age, gender, education and region. When describing the data at the supranational level, we also weight each country sample by its share of the world population.

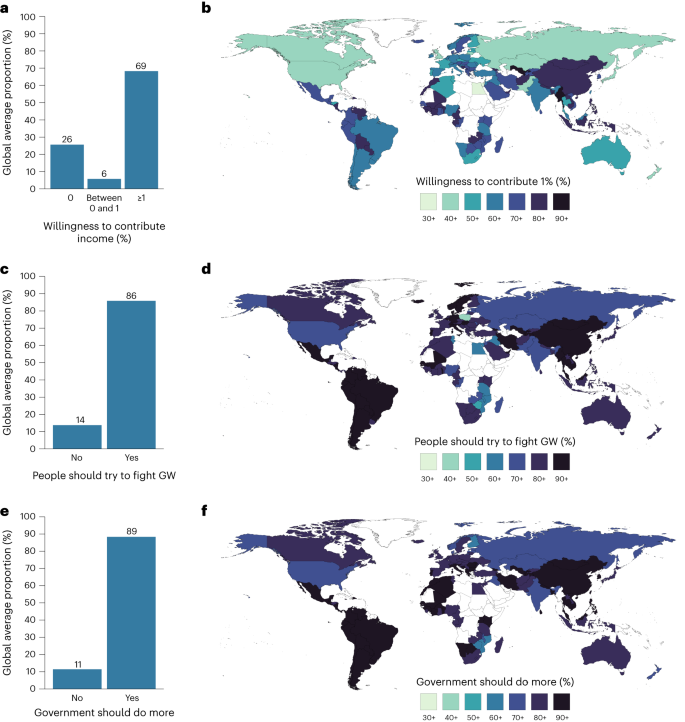

Widespread global support for climate action

The globally representative data reveal strong support for climate action around the world. First, a large majority of individuals—69%—state they would be willing to contribute 1% of their household income every month to fight global warming (Fig. 1a ). An additional 6% report they would be willing to contribute a smaller fraction of their income, and 26% state they would not be willing to contribute any amount. The proportion of respondents willing to contribute 1% of their income varies considerably across countries (Fig. 1b ), ranging from 30% to 93%. In the vast majority of countries (114 of 125) the proportion is greater than 50%, and in a large number of countries (81 of 125) the proportion is greater than two-thirds.

a , c , e , The global average proportions of respondents willing to contribute income ( a ), approving of pro-climate social norms ( c ) and demanding political action ( e ). Population-adjusted weights are used to ensure representativeness at the global level. b , d , f , World maps in which each country is coloured according to its proportion of respondents willing to contribute 1% of income ( b ), approving of pro-climate social norms ( d ) and demanding political action ( f ). Sampling weights are used to account for the stratified sampling procedure. Supplementary Table 4 presents the data. GW, global warming.

Second, we document widespread approval of pro-climate social norms in almost all countries. Overall, 86% of respondents state that people in their country should try to fight global warming (Fig. 1c ). In 119 of 125 countries, the proportion of supporters exceeds two-thirds (Fig. 1d ).

Third, we identify an almost universal global demand for intensified political action. Across the globe, 89% of respondents state that their national government should do more to fight global warming (Fig. 1e ). In more than half the countries in our sample, the demand for more government action exceeds 90% (Fig. 1f ).

Stronger willingness to contribute in vulnerable countries

Although the approval of pro-climate social norms and the demand for intensified political action is substantial in almost all countries (Fig. 1d,f ), there is considerable variation in the proportion of individuals willing to contribute 1% across countries (Fig. 1b ) and world regions (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5) . What explains the cross-country variation in individual WTC? Two patterns stand out.

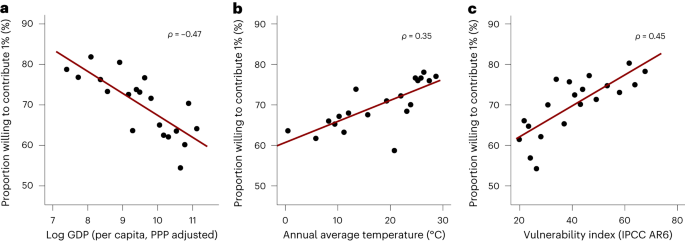

First, there is a negative relationship between country-level WTC and (log) GDP per capita ( ρ = −0.47; 95% confidence interval (CI), [−0.60, −0.32]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test; N = 125; Fig. 2a ). To illustrate, in the wealthiest quintile of countries, the average proportion of people willing to contribute 1% is 62%, whereas it is 78% in the least wealthy quintile of countries. A country’s GDP per capita reflects its resilience, that is, its economic capacity to cope with climate change. Put differently, in countries that are most resilient, individuals are least willing to contribute 1% of their income to climate action. At the same time, a country’s GDP is strongly related to its current dependence on GHG emissions 37 . For the countries studied here, the correlation coefficient between log GDP and log GHG emissions is 0.87. From a behavioural science perspective, this pattern is consistent with the interpretation that individuals are less willing to contribute if they perceive the adaptation costs as too high, that is, when the required lifestyle changes are perceived as too drastic.

a – c , Binned scatter plots of the country-level proportion of individuals willing to contribute 1% of their income and log average GDP (per capita, purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted) for 2010–2019 ( a ), annual average temperature (°C) for 2010–2019 ( b ) and the vulnerability index used in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) ( c ) 41 , 42 . The vulnerability index ranges from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating higher vulnerability. Correlation coefficients are calculated from the unbinned country-level data. We use sampling weights to derive the country-level WTC. Number of bins, 20; 6–7 countries per bin; derived from x axis. The red line represents linear regression.

Second, we find a positive relationship between country-level WTC and country-level annual average temperature ( ρ = 0.35; 95% CI, [0.18, 0.49]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test, N = 125; Fig. 2b ). The average proportion of people who are willing to contribute increases from 64% among the coldest quintile of countries to 77% among the warmest quintile of countries. Average annual temperature captures how exposed a country is to global warming risks 38 , 39 . Countries with higher annual temperatures have already experienced greater damage due to global warming, potentially making future threats from climate change more salient to their residents 40 .

Both results replicate in a joint multivariate regression and are robust to the inclusion of continent fixed effects and other economic, political, cultural or geographic factors (Supplementary Tables 6 – 9 ). Focusing on North America, we also find a significantly positive association between WTC and average temperature on the subnational level (Supplementary Fig. 2 ). Moreover, as low GDP and high temperatures constitute two important aspects of vulnerability to climate change, we also draw on a more comprehensive summary measure of vulnerability, derived for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report 41 , 42 . In addition to national income and poverty levels, the index also takes into account non-economic factors, such as the quality of public infrastructure, health services and governance. It captures a country’s general lack of resilience and adaptive capacity, and it is highly correlated with log GDP ( ρ = −0.93) and temperature ( ρ = 0.62). Figure 2c confirms that people living in more vulnerable countries report a stronger WTC.

The country-level variation in pro-climate norms and demand for intensified political action is much smaller than that for the WTC. Nevertheless, we find that higher temperature predicts stronger norms and support for more political action. We do not detect a significant relationship with GDP (Supplementary Table 10 ).

Beliefs and systematic misperceptions

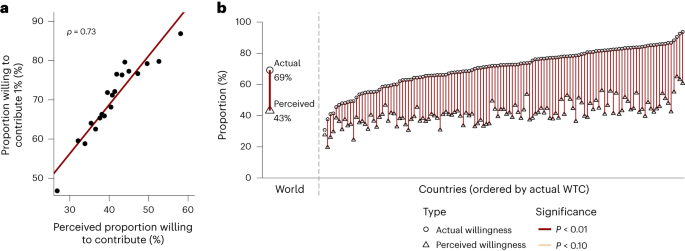

In line with previous research 11 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , our data support the importance of conditional cooperation at the global level. Figure 3a shows a strong and positive correlation between the country-level proportions of individuals willing to contribute 1% and the corresponding average perceived proportions of fellow citizens willing to contribute 1% ( ρ = 0.73; 95% CI, [0.64, 0.81]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test; N = 125).

a , Binned scatter plots of the country-level proportions of individuals willing to contribute 1% of their income and the average perceived proportions of others who are willing to contribute 1% of their income. We use sampling weights to derive the country-level WTC and perceived WTC. Number of bins, 20; 6–7 countries per bin; derived from x axis. The red line shows the linear regression. b , Gap between the global and country proportions of respondents who are willing to contribute 1% of their income (circles) and the global and country average perceived proportions of others willing to contribute (triangles). The reported significance levels result from two-sided t -tests testing whether the proportion of individuals who are willing to contribute is equal to the average perceived proportion. We use population-adjusted weights to derive the global averages and the standard sampling weights otherwise. We derive the averages based on all available data, that is, we exclude missing responses separately for each question. See Supplementary Figure 4 for additional descriptive statistics for the perceived WTC (median, 25–75% quartile range).

We document the same pattern at the individual level. In a univariate linear regression analysis, a 1-percentage-point increase in the perceived proportion of others’ WTC is associated with a 0.46-percentage-point increase in one’s own probability of contributing (95% CI, [0.41, 0.50]; P < 0.001; N = 111,134; Supplementary Table 11 ). This effect size aligns closely with the degree of conditional cooperation that has been documented in the laboratory 26 .

The critical role of beliefs raises the question of whether beliefs are well calibrated. In fact, Fig. 3b reveals sizeable and systematic global misperceptions. At the global level, there is a 26-percentage-point gap (95% CI, [25.6, 26.0]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test; N = 125; Supplementary Table 4 ) between the actual proportion of respondents who report being willing to contribute 1% of their income towards climate action (69%) and the average perceived proportion (43%). Put differently, individuals around the globe strongly underestimate their fellow citizens’ actual WTC to the common good. At the country level, the vast majority of respondents underestimate the actual proportion in their country (81%), and a large proportion of respondents underestimate the proportion by more than 10 percentage points (73%). This pattern holds for each country in our sample (Fig. 3b ). In all 125 countries, the average perceived proportion is lower than the actual proportion, significantly so in all but one country (two-sided t -tests, actual versus perceived WTC). If we limit the analysis to those respondents for whom we have non-missing data for both the actual and the perceived WTC, the global perception gap is estimated to be 29 percentage points (95% CI, [27.2, 30.0]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test; N = 125; Supplementary Table 12 ), and the average perceived proportion is estimated to be significantly lower than the actual proportion in all 125 countries (Supplementary Fig. 3 ).

Although the perception gap is positive in all countries, we note that the size of the perception gap varies across countries (s.d. = 8.7 percentage points). Examining the same country-level characteristics as before, we find that the gap is significantly larger in countries with higher annual temperatures and significantly smaller in countries with high GDP (Supplementary Table 13 ). These results are largely robust to the inclusion of other economic, political or cultural factors, which we do not find to be significantly related to the perception gap. These findings are robust to only using respondents for whom we have non-missing data for both the actual and perceived WTC.

Climate scientists have stressed that immediate, concerted and determined action against climate change is necessary 32 , 41 , 43 , 44 . Against this backdrop, our study sheds light on people’s willingness to contribute to climate action around the world. What sets our study apart from existing cross-cultural studies on climate change perceptions 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 and policy views 4 , 5 , 6 is its globally representative coverage and its behavioural science perspective.

The results are encouraging. About two-thirds of the global population report being willing to incur a personal cost to fight climate change, and the overwhelming majority demands political action and supports pro-climate norms. This indicates that the world is united in its normative judgement about climate change and the need to act.

The four aspects of cooperation discussed in this article are likely to interact with one another. For example, consensus on pro-climate norms is likely to strengthen individuals’ WTC and vice versa 13 . Similarly, the enactment of climate policies is likely to strengthen climate norms and vice versa 45 . We find a strong positive correlation between the WTC, pro-climate norms, policy support and beliefs about others’ WTC across countries (Supplementary Table 14 ). Moreover, countries with a stronger approval of pro-climate social norms have passed significantly more climate-change-related laws and policies ( ρ = 0.20; 95% CI, [0.02, 0.36]; P = 0.028 for a two-sided t -test; N = 122). These positive interactions suggest that a change in one factor can unlock potent, self-reinforcing feedback cycles, triggering social-tipping dynamics 46 , 47 . Our findings can inform system dynamics models and social climate models that explicitly take into account the interaction of human behaviour with natural, physical systems 48 , 49 .

The widespread willingness to act against climate change stands in contrast to the prevailing global pessimism regarding others’ willingness to act. The world is in a state of pluralistic ignorance, which occurs when people systematically misperceive the beliefs or attitudes held by others 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 50 . The reasons underlying this perception gap are probably multifaceted, encompassing factors such as media and public debates disproportionately emphasizing climate-sceptical minority opinions 51 , and the influence of interest groups’ campaigning efforts 52 , 53 . Moreover, during periods of transition, individuals may erroneously attribute the inadequate progress in addressing climate change to a persistent lack of individual support for climate-friendly actions 54 .

Importantly, these systematic perception gaps can form an obstacle to climate action. The prevailing pessimism regarding others’ support for climate action can deter individuals from engaging in climate action, thereby confirming the negative beliefs held by others. Therefore, our results suggest a potentially powerful intervention, that is, a concerted political and communicative effort to correct these misperceptions. In light of a global perception gap of 26 percentage points (Fig. 3b ) and the observation that a 1-percentage-point increase in the perceived proportion of others willing to contribute 1% is associated with a 0.46-percentage-point increase in one’s own probability to contribute (Supplementary Table 11 ), such an intervention may yield quantitatively large, positive effects. Rather than echoing the concerns of a vocal minority that opposes any form of climate action, we need to effectively communicate that the vast majority of people around the world are willing to act against climate change and expect their national government to act.

Sampling approach

The survey was carried out as part of the Gallup World Poll 2021/2022 in 125 countries, with a median total response duration of 30 min. The four questions were included towards the end of the Gallup World Poll survey and were timed to take about 1.5 min.

Each country sample is designed to be representative of the resident population aged 15 and above. The geographic coverage area from which the samples are drawn generally includes the entire country. Exceptions relate to areas where the safety of the surveyors could not be guaranteed or—in some countries—islands with a very small population.

Interviews are conducted in one of two modes: computer-assisted telephone interviews via landline or mobile phone or face to face (mostly computer assisted). Telephone interviews were used in countries with high telephone coverage, countries in which it is the customary survey methodology and countries in which the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic ruled out a face-to-face approach. There is one exception: paper-and-pencil interviews had to be used in Afghanistan for 73% of respondents to minimize security concerns.

The selection of respondents is probability based. The concrete procedure depends on the survey mode. More details are available in the documentation of the Gallup World Poll ( https://news.gallup.com/poll/165404/world-poll-methodology.aspx ) 55 .

Telephone interviews involved random-digit dialling or sampling from nationally representative lists of phone numbers. If contacted via landline, one household member aged 15 or older is randomly selected. In countries with a landline or mobile telephone coverage of less than 80%, this procedure is also adopted for mobile telephone calls to improve coverage.

For face-to-face interviews, primary sampling units are identified (cluster of households, stratified by population size or geography). Within those units, a random-route strategy is used to select households. Within the chosen households, respondents are randomly selected.

Each potential respondent is contacted at least three (for face-to-face interviews) or five (telephone) times. If the initially sampled respondent can not be interviewed, a substitution method is used. The median country-level response rate corresponds to 65% for face-to-face interviews and 9% for telephone interviews. These response rates are comparatively high considering that survey participants are not offered financial incentives for participating in the Gallup World Poll. For telephone interviews, the Pew Research Center reports a response rate of 6% in the United States in 2019 ( https://pewrsr.ch/2XqxgTT ). For face-to-face interviews, ref. 56 found a non-response rate of 23.7% even in a country with very high levels of trust, such as Denmark.

The median and most common sample size is 1,000 respondents. An overview of survey modes and sample sizes can be found in Supplementary Table 15 .

Sampling weights

Although the sampling approach is probability based, some groups of respondents are more likely to be sampled by the sampling procedure. For instance, residents in larger households are less likely to be selected than residents in smaller households because both small and large households have an equal chance of being chosen. For this reason, Gallup constructs a probability weight factor (base weight) to correct for unequal selection probabilities. In a second step, the base weights are post-stratified to adjust for non-response and to match known population statistics. The standard demographic variables used for post-stratification are age, gender, education and region. In some countries, additional demographic information is used based on availability (for example, ethnicity or race in the United States). The weights range from 0.12 to 6.23, with a 10–90% quantile range of 0.28 to 2.10, ensuring that no observation is given an excessively disproportionate weight. Of all weights, 93% are between 0.25 and 4. More details are available in the documentation of the Gallup World Poll ( https://news.gallup.com/poll/165404/world-poll-methodology.aspx ) 55 .

We use these weights in our main analyses in two ways: first, when deriving national averages, we weight individual responses with Gallup’s sampling weights; and, second, when conducting individual-level regression analyses, we weight respondents with Gallup’s sampling weights.