- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 27 October 2022

Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia

- Habtamu Mekonnen 1 ,

- Zemenu Bires ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4156-3235 2 &

- Kassegn Berhanu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9981-5901 3

Heritage Science volume 10 , Article number: 172 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

54k Accesses

19 Citations

Metrics details

Cultural heritage treasures are precious communal assets that show the past human legacy. It depicts present and future way of life as well as cultural values of a society, and enhances solidarity and social integration of communities. This study is designed to investigate the practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservations in North Shoa Zone, Central Ethiopia. The research employed a mixed research approach and cross-sectional descriptive and explanatory research design. The researchers applied multiple data gathering instruments including questionnaire survey, interview, focus group discussion and observation. Concerning sampling techniques, systematic random sampling technique was applied to select samples from local communities, and purposive sampling was designed to choose interviewees from government authorities, and culture and tourism office experts of North Shoa Zone and respective districts. The actual and valid sample size of the study is 236. The findings of the study revealed that the cultural heritage properties in North Shoa are not safeguarded from being damaged and found in a poor status of conservation. The major conclusion sketched from the study is that the principal factors affecting heritage conservation are lack of proper management, monitoring and evaluation, lack of funds and stakeholder involvement, urbanization, settlement programs and agricultural practice, poor government concern and professional commitment, poor attitude towards cultural heritage and low level of community concern, vandalism and illicit trafficking, low promotions of cultural heritage, and natural catastrophes such as invasive intervention, climate change (humidity and frost, excessive rainfall and flood, heat from the sun). The study implied that the sustainability of cultural heritage in the study area are endanger unless conservation practice is supported by conservation guidelines, heritage site management plans and research outputs, stakeholders’ integration, and community involvement. Most importantly, the study recommends the integration of heritage conservation and sustainable development, and the promotion of conservation is a way of achieving economic and social sustainability.

Introduction

Heritage is our legacy from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to the future generations. Our cultural and natural heritage resources are both irreplaceable sources of life and inspiration. They are our touchstones, our points of reference, and our identity [ 1 ]. Cultural heritage is the legacy of physical artifacts, cultural property, and intangible attributes of a group or society that are inherited from past generations, maintained in the present, and bestowed for the benefit of future generations [ 2 , 3 ].

According to Bleibleh and Awad [ 4 ], and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 1972: Article 1), cultural heritage includes monuments: architectural works, sculpture, painting, inscriptions, archaeological structure, cave dwellings; buildings: groups of separate or connected buildings and their architectures, homogeneity or place in the landscape; and sites: man made creativity or the combined work of nature and man. Cultural heritage should have outstanding universal value from the historical, architectural, commemorative, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological point of view. Cultural heritage provides communities, groups, and individuals with a sense of identity and continuity, helping them to visualize their world and giving meaning to their way of living together [ 5 ].

In Ethiopian nations, nationalities, and people’s context, the definition of cultural heritage could be used to incorporate their varied social, economic, political, administrative, moral, religious, and psychological conditions [ 6 ]. Ethiopia is a great country with its fabulous 3000 years history [ 7 ], a population of about 114 million people endowed with astonishingly rich linguistic and cultural diversity with more than 80 living languages and 200 dialects, spoken by as many ethno-linguistic communities [ 8 ].

In this era of globalization, there is a growing fear that culture around the world will become more uniform, leading to a decrease in cultural diversity. To counter this potential homogeneity, strategies have been developed to preserve culture of various communities whose very existence could be threatened. Living culture is highly susceptible to becoming extinct [ 9 , 10 ]. Currently, the surge of interest in culture is creating new possibilities for safeguarding cultural heritage as a major component in building a sustainable cultural vision for the world [ 11 ]. In the context of UNESCO’s activities, the value and the importance of safeguarding cultural heritage is universally recognized [ 1 ].

Conservation of cultural heritage can be defined as all measures and actions aimed at safeguarding cultural heritage while ensuring its accessibility to present and future generations. Conservation embraces preventive preservation, adaptation, reconstruction, and restoration. All measures and actions should respect the significance and physical properties of the cultural heritage item [ 12 ].

In Ethiopia, the Authorities for Research and Conservation of Cultural Heritage (ARCCH) within the Ministry of Tourism and UNESCO Addis Ababa Office established a joint work plan (2006–2007) concerning inventorying and safeguarding both tangible and intangible cultural heritage in the country [ 7 ]. Besides, both the 1995 constitution and the 1997 cultural policy of Ethiopia refers to equal safeguard, recognition of and respect for all Ethiopian languages, heritage, history, handicraft, fine arts, oral literature, traditional lore, beliefs, and other cultural features. Following the ratification of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Cultural Heritage, the ARCCH designed a strategy on the identification, safeguarding, and promotion of cultural heritage through a national inventory-making exercise.

In principle, in Ethiopia, there are policies, guidelines and regulations of cultural heritage conservation. In practice, however, the majority of the heritage attractions are in poor conservation status (for instance light shelter protection to the world heritage site of Lalibela Rock hewn Churches); demolished due to ignorance (e.g. Ankober Archaeological site); intentionally destructed due to misinterpretation and interethnic conflict (as evidenced on Ras Mekonnen Monument in Harar, Ethiopia), and the destruction of Al-Negash Mosque in Tigray, Ethiopia due to the war between the Federal Government of Ethiopia and Tigray Liberation Front.

North Shoa is a special focus from cultural and historical perspectives. Historically, the region had been administrative centres or seats of government for the Kings of Shoa and Ethiopia from the reign of Amde-Tsion (1314–1344) and Zera Yakob (1434–1468) up to Emperor Menelik II (1865–1913). In this regard, the historical sites such as Menz, Tegulet, Debre Berhan, Sela Dingay, Ankober, Liche, and Angolela had served as a headquarter of the government of Ethiopia in the medieval history and in the second half of nineteenth century.

When almost all African nations were under European colonization in the late 19 th and in the first half of twentieth century, Shoa in general and North Shoa in particular, was in position to establish formal diplomatic relations with the Europeans countries. Consequently, European embassies (for instance British, France and Italy) were opened at Ankober for the first time. Most importantly, the region is a birth place of prominent patriots (e.g. Ras Abebe Aregay, Hailemariam Mamo, Buayalew Abate, Fiwtarari Gebeyehu to mention few among many) who sacrificed a lot in defending the sovereignty of Ethiopia against foreign aggressors.

Culturally, North Shoa is also rich with Christian religious sites such as churches, monasteries, and holy water. Famous religious sites include but not limited to Tsadikanie St. Mary Church, Kukyelesh St. Mary, Abune Melike Tsedik monastery, Zebir Gabriel church, Seminesh Kidane Mihiret church which are known for their annual religious ceremonies, holy water that cure diseases and cleanse sins. Important traditional games such as hockey and horse racing or horse galloping are practiced along with feast days. Besides, North Shoa is not only a special attention for the Christians, but also known for its rich history and incredible Islamic heritage relics. The sultanates of Shoa (9th–thirteenth century), Ifat (thirteenth–fifteenth century) as well as the 13th medieval great mosque of Goze (still existing Islamic architecture) are some of the evidences of the historical and religious Islamic civilizations [ 13 , 14 ].

However, despite the presence of plenty of cultural and historical heritage in Ethiopia in general and North Shoa Zone in particular, their sustainability is in question and the contribution of heritage tourism to the host community is very low due to various impacts such as developmental projects near or on heritage sites, absence of demarked buffer zones, lack of awareness or ignorance, theft and looting, embezzlement, inappropriate conservation practices, and natural damage/ deteriorations. The most widely known problems of cultural heritage include archaeological looting, destruction of cultural sites, and the theft of works of art from churches and museums all over the world are testimonies of cultural heritage destructions [ 15 ].

According to Eken, Taşcı, and Gustafsson [ 16 ] cultural heritage properties are vulnerable to various physical, chemical, natural and anthropogenic factors that worsening the sustainability of heritage attractions. Though North Shoa has a paramount significance from historical and cultural perspectives, it has never received due attention from the government, researchers and other conservationists stakeholders as bold as its potentials. Besides, scholarly works regarding cultural heritage conservation are not sufficient in East Africa in general and in Ethiopia in particular. Hence, to address this research gap, the need to research on challenges and practices of cultural heritage conservation is one of the top priorities.

Literature review

Issues of cultural heritage, cultural ownership, rights, politics and representation.

When the homogenization and standardization of heritage occur, the politics of cultural identity emerges as a critical issue. This is particularly true since heritage is not just a matter of the past, but very much a conduit for constructing the future [ 17 ]. In other words, how the local communities present their cultural heritage to the outside visitors affects the way the community members envisage their future. This has been observed in numerous cross-cultural ethnographic cases [ 18 , 19 ]. Needless to say, how to represent the cultural heritage reflects the present condition of political hierarchies that exist within the society.

Members of local communities have diverse opinions that are positioned in different contexts of their lives. A unified representation of cultural heritage may not be something that some members of the community can easily accept [ 20 ]. This may affect the community negatively in both socio-cultural and political domains. Sometimes, the cohesiveness within the community is weakened, and some members even decide to leave the community altogether which is a serious breach of the cultural rights of these members.

Identification and documentation of cultural heritage

Inventories should identify threats that certain elements of cultural heritage is facing. Based on such information, a plan for safeguarding or revitalization can be developed. When conservation of heritage property is impossible due to lack of funds and experts; digital preservation deemed to be an alternative means of safeguarding cultural heritage. According to Koiki- Owoyele, Alabi and Egbunu [ 21 ] heritage digitization is a process of taking photographs or scanning a material and transferring it to a computer. The dissemination of digital preserved heritage on websites, social media platforms and Google search optimization helps to reach more users which in turn reduce the cost and energy of users to undertake a journey to a library, archive or museum to visit the heritage. Digital preservation is a long lasting solution to threats such as decay, war, fire and flood and enables to secure the availability of useful resources for academicians of future generations [ 22 ].

Danger of extinction

According to Karin and Philippe [ 23 ] the new alternative approaches to cultural heritage conservation recognize the importance of preserving vital and living elements of culture. Because of natural and human factors, developments around cultural heritage, conflict of interest among stakeholders, theft and vandalism, and inappropriate conservational practices, and hence, the danger of losing them is sometimes underestimated [ 24 ].

Truscott [ 25 ] argued that local communities themselves often do not see the importance of preserving their cultural heritage properties. They may consider their cultural heritage as backward and as a hindrance to their ability to access "modern society" and economic wealth. It is essential, therefore, not only to create a system that values and respects minority culture but also to encourage communities to become aware of their cultural treasures and to help them find ways to preserve those treasures [ 26 ].

Roy and Kalidindi [ 27 ] stated that rapid growth of urbanization, mass tourism, lack of funds, improper project selection, lack of traditional know-how among conservation professionals, poor handling system or heritage management, corruption, and erroneous conservation policy are responsible for the poor performance of heritage conservation projects [ 28 ]. Besides, adverse factors that threaten heritage conservation include heritage trafficking, limited community participation in conservation, cultural degradation, and inadequate attention from government bodies, and poor coordination among stakeholders [ 29 ]. Other critical issues of heritage conservation encompass indigenous claims of ownership and access to material culture, authentic, original value embodied in material culture [ 30 ]; removal of monuments from their original site, damage through the flooding of agricultural land, resettlement programs and rebuilding of urban centres [ 31 ].

Cultural heritage properties have been attacked in wars of conquest and colonization, during interstate and civil conflicts, by governments, protestors or rebels across the world [ 32 ]. Monuments such as historical buildings and statues; religious sites like synagogues, mosques, temples, monasteries, churches; material culture exhibitions and collection sites (e.g. museums, art galleries, and libraries) which depict the collective narratives, stories and memories of people have become vulnerable to destructions [ 33 ].

It has been documented that over 13,000 cultural heritage sites were destroyed in the Middle East particularly in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Libya [ 34 ]. The widespread devastation or attacks include world heritage sites. For instance, the six UNESCO World Heritage sites of Syria such as the Ancient City of Damascus, the Ancient City of Bosra, the Site of Palmyra (ancient temples, tombs and antiquities with the age of more than 2000 years), the Ancient City of Aleppo, Crac des Chevaliers and Qal’at Salah El-Din, and the Ancient Villages of Northern Syria or Dead Cities are either destroyed or partially damaged during the armed conflict between ISIS (also called IS, ISIL, Da’esh or the Islamic State) and state government [ 35 , 36 ].

The ISIS has systematically been destroying the cultural heritage (ancient monuments, mosques, shrines, cemeteries, works of art at museums and libraries) blowing up the Armenian, Syrian Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches, monasteries and the tombs of prophets. Thousands of archaeological and cultural sites (including those aged in the Bronze, Iron, Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Islamic periods) in Syria are victims of the on-going fighting or war [ 37 ].

The destruction of Yazidi shrines and the obliteration of ancient sculptures called “lamassu", a vital symbol to the modern Assyrian Christian population, and the devastation and vandalism of other Christian relics and churches in the Tadmor and Palmyra area were deliberate to deface the minority religious and cultural sites as well as to terrorize and subdue the minorities [ 38 ].

As noted in the work of Wollentz [ 39 ] during the Yugoslavian Civil War, cultural heritage such as the medieval Stari Most Bridge was destroyed, and the old town of Dubrovnik, one of the first sites inscribed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites was bombarded.

In Africa, the most outstanding cultural site of Timbuktu (Mali) famous for its world heritage sites of mausoleums and mosques having exceptional cultural, historical and spiritual significance were targeted to destruction [ 40 ].

By the same token, the Eritrea–Ethiopia war in 1998–2000 was responsible for the devastation of an essential archaeological monument nearby the Ethio-Eritrea border [ 41 ].

The major causes for the destruction of cultural heritage and systematic cultural cleansing include civil war, ignorance and negligence, religious differences or fundamentalism and radical ideologies (for instance, ISIS perceived that most of the cultural and religious heritage in the middle east are false idols that are heretical to Islam) [ 42 , 43 ], a mission to accomplish military, political, and economic objectives [ 34 ] and developmental projects such as urban reconstruction [ 44 ].

Lack of funds and experts, and organizational structure problem

The custodian of cultural heritage is not always good at organizing or management of funds [ 31 ]. On the other hand, those who are experts in organizing and managing funds are not always experts or even interested in cultural heritage. So the solution has been creating collaboration between these two kinds of people: between the cultural heritage custodians and those who are experts in managing and organizing these kinds of projects [ 45 ]. Another mechanism of securing funds and initiating experts is devising means of discussions regarding the values of cultural heritage on different media such as social media, broadcast media, and printed media. The other issue mentioned by Mancacaritadipura [ 45 ] the younger generation is less interested in the local culture. To overcome this issue, Mancacaritadipura suggested that the school curriculum should include cultural heritage at local content [ 45 ]. Besides the main curriculum, Mike and David [ 46 ] forwarded that awareness creation about the significance and promotion of cultural heritage should be undertaken in schools, colleges, and universities.

As observed in many African countries, states have not yet created an official section and positions in the Department of Culture and Tourism to be specifically responsible for cultural heritage [ 26 ]. Truscoot (2000) forwarded that the government may create a sub-directorate of cultural heritage which will make it easier to do long-term programs [ 25 ]. Besides, UNESCO (2005) has been identified difficulties in finding qualified human resources to participate in efforts to preserve and develop cultural heritage [ 47 ].

Opportunities for safeguarding cultural heritage

Stakeholders involvement.

Cultural heritage must be thoughtfully managed if it is to survive in an increasingly globalized world [ 47 ]. True partnerships are required between all relevant stakeholders, particularly governments, private tourism sectors, NGOs, and local communities. Through mutual understanding, key stakeholders can build on their shared interest in cultural assets, in close consultation with local communities, the ultimate bearers of humankind’s cultural legacy [ 48 ]. The awareness and attitude of among stakeholders towards the conservation of cultural heritage is crucial to have a common stake among interest groups towards cultural heritage and development, to keep sustainable conservation management, and to promote cultural tourism [ 49 ]. Community-based tourism projects allow for direct communication between communities and heritage tourism while sustainably developing cultural assets as tourism products [ 50 ].

Community participation

Communities must be actively involved in safeguarding and managing their cultural heritage since it is only the one who can consolidate their presence and ensure its future [ 51 ]. Each community, using its collective memory and consciousness of its past, is responsible for the identification as well as the management of its heritage [ 52 ]. Communities, in particular indigenous communities, groups, and, in some cases, individuals, play an important role in the production, safeguarding, maintenance, and re-creation of the intangible cultural heritage. Within the framework of safeguarding the cultural heritage, each state party shall endeavour to ensure the widest possible participation of communities, groups, and, where appropriate, individuals that create, maintain, and transmit such heritage, and to involve them actively in its management [ 53 ]. Apart from stakeholders’ participation and community involvement, resource mobilization, ecotourism activities, and corporate fundraising mechanisms could be devised to achieve conservation programmes, and contribution should be based on willingness and abilities of stakeholders [ 54 ].

UNESCO committee and convention for safeguarding cultural heritage

Today, even in a world of mass communication and global cultural flows, many forms of cultural heritage properties are being preserved or conserved in every corner of the world [ 55 ]. Other forms and elements of cultural heritage resources which are more fragile, and some are even endangered and needs measures called for by the UNESCO Convention of safeguarding cultural heritage at the national and international levels can help communities to ensure that their heritage remains available to their descendants for decades and centuries to come [ 56 ]. The Convention recognizes that the communities, groups, and, in some cases, individuals who safeguard and maintain cultural heritage must be its primary stewards and guardians, but their efforts can be supported or undercut by state policies and institutions [ 5 ]. The challenges facing such communities, and those who work on their behalf, are to ensure that their children and grandchildren continue to have the opportunity to experience the heritage of the generations that preceded them and that measures intended to safeguard such heritage are carried out with the full involvement and the free, prior and informed consent of the communities, groups, and individuals concerned [ 56 ].

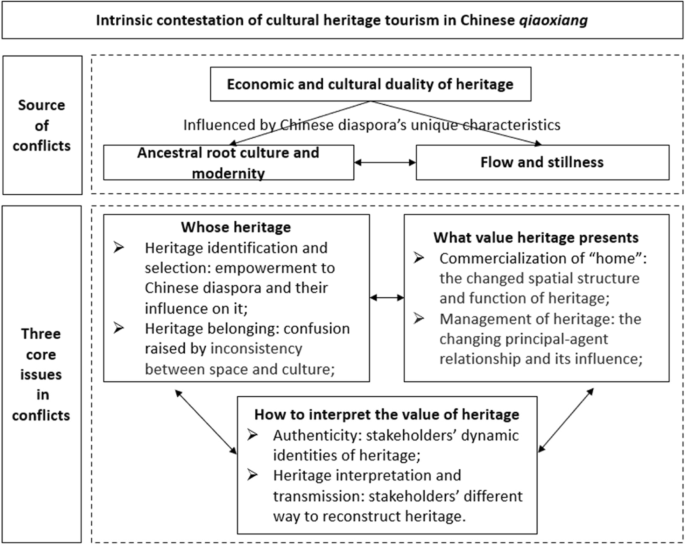

Theoretical framework of the study

Recently, heritage conservation domains received adequate attention from both the academia and practitioners [ 57 ]. According to Sinamai [ 58 ] the practices of heritage conservation and management must align with the principle of community-based cultural heritage conservation which recognizes the communities’ well-being and empowers the host community through the harnessing of endogenous knowledge and skills. And, heritage conservation practices shall respect local culture such as vernacular architecture. Certain principles shall be adhered when cultural heritage conservation is applied. The heritage shall continue to be used according to its earlier purpose, and when this is not feasible, a compatible use should be sought with minimal alteration to the heritage and its context. Conservation techniques shall also focus on repairing rather than replacing. Since, heritage relics are authentic evidence of our past, historic fabrics should be kept as much as possible. While repairing and maintaining the heritage, emphasis shall be paid to respect the heritage context, location and significant views shall be maintained [ 59 ]. Cultural heritage can be deteriorated, damaged or destructed due to anthropogenic and natural factors. The anthropogenic or human factors include conflict of interest and ownership issues, contestation and cultural politics [ 12 , 60 ], negligence, ignorance and poor handling system, theft and illicit trafficking, civil war, unprofessional conservation, urbanization, developmental projects, large scale agriculture and mining activities [ 58 ]. The natural factors may encompass climatic and geological factors such as solar radiation, rainfall, humidity, wind pressure, and natural catastrophes such as earth quake, flooding, lighting and thunder as well as biological factors like plants (e.g. invasive specious, weeds) and animals such as rat can harm the heritage [ 16 ]. Depending on the level of impact on the heritage, various conservation approaches can be applied or practiced. These are: Maintenance -continuous protective care of the fabric and setting of heritage [ 57 ]; Preservation - maintaining the fabric of heritage in its existing state and retarding deterioration [ 61 ]; Restoration -returning the existing fabric of a place to a known earlier state by removing accretions or by reassembling existing components without the introduction of new material [ 62 ]; Reconstruction - returning a place to a known earlier state and is distinguished from restoration by the introduction of new material into the fabric [ 61 ]; and Adaptation - modifying a place to suit the existing use or a proposed use [ 63 ].

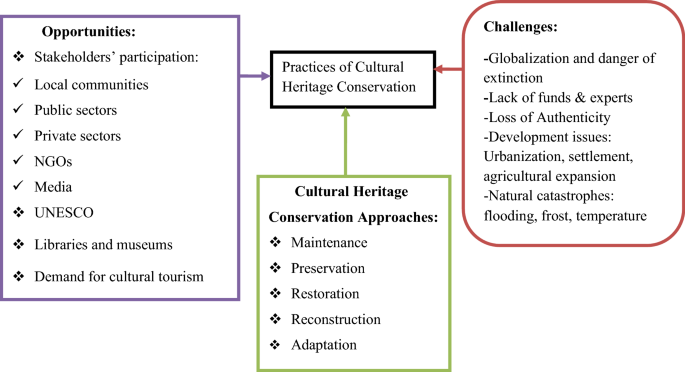

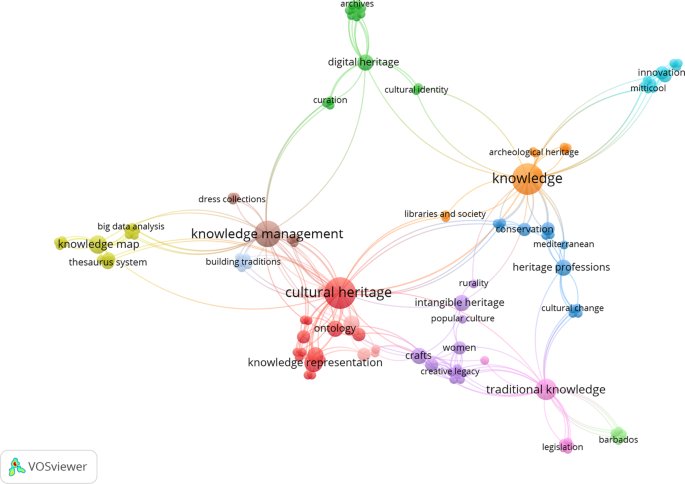

Based on the literature review and theoretical framework, a conceptual framework is formulated as illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Conceptual framework of the study (Own compilation, 2021)

Methods and materials

Description of the study area.

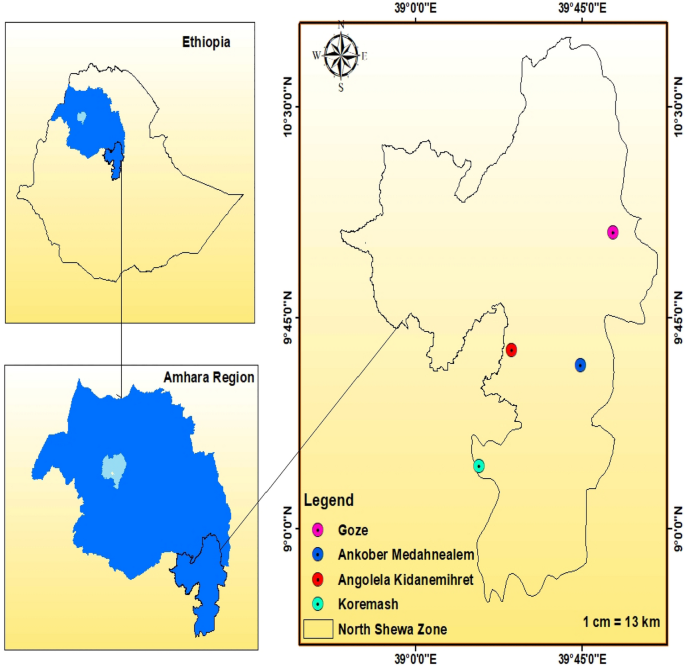

North Shoa Zone of Amhara regional state is located in the central part of Ethiopia, north of the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. North Shoa Zone is blessed with plenty of cultural, historical, and natural tourism resources [ 64 ]. The study area is chosen due to its rich medieval Christian and Islamic historical and cultural heritage relics of Ankober historical site, Koremash of bullet factory, Angolela Tera of King Sahilesillassie palace and Goze Mosque (See Fig. 2 ).

Map of the Study Area (Researchers own map, 2021)

Research approach and data analysis techniques

The research employed both qualitative and quantitative research approaches which is a mixed research approach. A descriptive and explanatory method of cross-sectional research design was used. The descriptive research design helps to describe the current heritage conservation practices and challenges. And, explanatory research design was used to examine the impacts of predictors or explanatory variables such as anthropogenic and natural factors on cultural heritage conservations.

The quantitative data was collected through a questionnaire survey whereas qualitative data was gathered using interviews, site observations, focus group discussions and document analysis. Due to the nature of the study, the researchers applied multiple data gathering instruments as stated above. For instance, survey questionnaire helps to collect information regarding community’s sense of belongingness, access to capacity building trainings, community’s concern or attitude of cultural heritage. And, information such as status of cultural heritage conservation, on-going conservation practices, and buffer zones demarcation can be obtained through field observations. Interview and focus group discussions help to get information with respect to roles of stakeholders towards cultural conservation, promotion of cultural heritage, fund and expert issues. Document analysis helps to gather information such as action plans of respective offices, conservation procedures and guidelines and management of heritage.

The subjects of this study include the local communities, North Shoa Zone and district’s Culture and Tourism office staff, Authority for Research and Conservation of Cultural Heritage (ARCCH) and religious institutions having direct and indirect involvement in tourism activities. Self-administered questionnaire were disseminated using random sampling techniques to 384 households.

Informants for interview were selected purposively based on their knowledge and closeness to the research problem under study. A total of 10 purposively selected individuals (from North Shoa Culture and Tourism, Debre Berhan Culture and Tourism Office, Angolola and Tera Culture and Tourism Office, Ankober Culture and Tourism Office, and ARCCH) were interviewed. Focus group discussants were selected from local representatives such as religious leaders, local elders, and 4 focus group discussions (total 28 discussants) was performed at prominent heritage sites, namely: Ankober, Koremash, Goze and Angolela district. The interview and focus group discussions were undertaken through taking notes and recording followed by transcribing.

The quantitative data was analysed through descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage, mean and standard deviations) and inferential statistics such as exploratory factor analysis, correlations and regressions whereas, content analysis was employed to thematically analyse the qualitative data.

Reliability and validity analysis

The reliability and validity test has been conducted to assure the appropriateness of the instrument and the consistency of the results using the pilot study. The validity of the research explains how well the collected data covers the actual area of investigation [ 36 ]. Hence, to assure the validity of the instruments, the research adapted the standardized questionnaires and interview checklists from literature [ 8 , 15 , 18 , 27 , 29 , 50 , 57 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 65 , 66 ] and the items were checked by consulting the research advisors and subject area experts. Hence 15 questionnaires were distributed to tourism and heritage management experts working at universities, culture and tourism offices, and ARCCH to check content validity. And, experts forwarded important inputs regarding the contents, layout and structure of the questionnaire.

Besides, the reliability concerns the extent to which a measurement of a phenomenon provides stable and consist result, or it is all about the consistency of the result to measure inter-item homogeneity of each construct using Cronbach’s alpha value greater than or equal to 0.70 and the inter-item correlations were greater than or equal to 0.30 were included to collect data and included in the analysis [ 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 ]. According to Sharma [ 71 ] reliability statistics is classified the depending on the Cronbach alpha value: α ≥ 0.90 = Excellent, 0.90 > α ≥ 0.80 = Good, 0.80 > α ≥ 0.70 = Acceptable, 0.70 > α ≥ 0.60 = Questionable, 0.60 > α ≥ 0.50 = Poor and α < 0.50 = Unacceptable.

In the present study, the reliability analysis was made by employing 58 observations which are nearly 15% of the total sample population [i.e., 15%*384 = 57.6) for a pilot survey. The items from each of the constructs having very low inter-item correlation below.30 were removed. The reliability analysis (see Table 1 ) revealed the Cronbach alpha coefficient that exhibited the consistency of the results that ranges from 0.741 to 0.802 that made the result acceptable [ 69 , 70 ].

Results and discussion

Respondents characteristics.

From a total of 384 disseminated questionnaires, 198 valid observations (52% response rate) were useful for analysis, and the majority of the respondents were males that account for 143 (72. 2%) whereas 55 (27.8%) were female respondents (see Table 2 ). And, the majority of them were youngsters under 18–35 years of age that accounting for 175 (79.3%). The survey indicates the youngsters are the majority of employees working and residing around cultural heritage which can be basic to apply cultural heritage conservation practices for better off.

Regarding place of residence and livelihood strategy of the respondents, 68 (34.3%), 52 (26.3%) and 44 (22.2%) reside in and around heritage sites namely, Ankober Medahnealem , Koremash and Goze whereas few respondents accounted for 34 (17.2%) lived in Angolela Kidanemihret area. Regarding the livelihood strategy people employed, the majority of the respondent led their household through employment in government offices followed by engaging in agriculture and working as a private employee accounts for 61.6%, 12.1% and 9.6% respectively (see Table 3 ).

Practices of cultural heritage conservation

The research finding indicates that 12.1% and 30.8% of respondents strongly disagreed, and disagreed respectively whereas 33.8% and 7.6% of respondents agreed and strongly agreed regarding an attempt of cultural heritage conservation in the study areas. The result revealed that there is insufficient attempt to conserve the heritage. Similar to this study, in Africa and many developing countries, cultural heritage have been facing hindrances of multiple platforms in unplanned manner that didn’t account for heritages sustainable use [ 72 ]. Unlike the finding of the present study, Ekwelem, Okafor and Ukwoma [ 72 ] pointed that the preservation of cultural heritage properties enhances historical and cultural continuity, fosters social cohesion, enables to visualization of the past and envisioning the future, and hence it is indispensable for sustainable development. Another study that supports this argument revealed that a need for conservation of heritage is subjected to a desire to transfer away from object oriented conservation and preservation practices, and the theoretical commitment to social constructivism that consider heritage a socio-cultural process [ 73 ]. The aforementioned two findings assured that heritage conservation practices should not only prepare for their objective value like source of economy but also as a social and cultural process that could maintain history which in turn escalate social cohesion, promote identity and proud. The finding revealed that the local community has a sense of belongingness and identity to the cultural heritage as it is portrayed by the respondents' response shown by 34.3% and 7.1% of agreement and strong agreement. This significant level of community belongingness and awareness about the cultural heritage will overpoweringly support the conservation efforts at heritage sites [ 74 ].

The practice of cultural heritage conservation in the study area is not based on research as 16.2% & 38.4% of the respondents strongly disagreed and disagreed in this regard. The present finding suggests that in-depth and strong research to develop conservation guidelines and undertake conservation activities in heritage sites. According to Garrod and Fyall [ 75 ], conservation management should consider timeliness and managerial prudence. The timeliness concept stated that conservation funds should be allotted in a timely fashion to save high conservation costs in the future. From the managerial prudence angle, parallel measures or techniques should be designed to prevent further deterioration [ 75 ]. Moreover, the study of Oevermann [ 76 ] scrutinized the “Good Practice Wheel” that is composed of management, conservation, reuse, community engagement, sustainable development and climate change, education, urban development, and research that expresses each of the good practice criteria spinning wheels which also needs the consideration of those criteria while practising heritage conservation. In this regard, the conservationist expert from ARCCH (personal communication, 21 June 2021) also underlined that,

Though there are efforts by the conservationists to undertake in-depth research, there are initiations mainly from the political leaders showing a commitment to conserve the heritage without adequate research and analysis.

Another participant from the Authority for Conservation of Cultural Heritage (Head, Conservators, personal communication, June 17, 2021) portrayed;

The basis and detrimental problem in the practices of conservation especially in cultural heritage is either lack of original material to conserve perfectly as it was or unavailability of raw materials that resemble originality which makes the conservation practice less effective. He added that the problem exacerbated by the lack of conservationists in the field makes the Ethiopian Heritage in danger.

Besides, regular follow-up of existing status for conservation hasn't been made with 20.7% and 37.9% of strong disagreements and disagreements that revealed poor status of conservation. Similarly, capacity building training on heritage conservation is not delivered at different times to the communities, conservationists and other key stakeholders that are exhibited by a total of 65.7% level of disagreement (where 26.3 replied with strong disagreement and 29.4% replied with a disagreement scale). Only 17.7% of respondents were found in the agreement response category whereas 16.7% were unable to fall in the two categories either (see Table 4 ). Hence, the finding of this study revealed that there is a low-level practice of cultural heritage which needs to be improved. Analogues to this, the conservation of heritage requires the three most important elements of heritage conservation underlined by professionals (curators, academics and consultants) are training and expertise of maintenance staff, budget and financial planning, and conservation plan [ 77 ]. Conservation efforts should be monitored that could follow up information for condition, risks and value assessment, strengths and support strategic heritage planning regularly which in turn should be developed based on an inventory system that requires continuous monitoring [ 78 ].

Challenges of cultural heritage conservation

This study was also concerned with the investigation of the various barriers that hinder cultural heritage conservation practices for better management and sustainability of cultural heritage. Thus, to identify these factors, factor analysis was employed to extract the list of factors and to group each of the linear components onto each factor if found significant. A total of 22 items or linear component factors (variables) were employed after checking the reliability of items in the pilot survey. Those variables were coded as: 01-The local community have no positive attitude towards cultural heritage; 02- The local community are not concerned to the cultural heritage; 03- Population growth and settlement programs have impacts on cultural heritage of the area; 04- Conflict of interest among stakeholders to safeguard the cultural heritage; 05- A practices of heritage conservation without the involvement of professional; 06- Practice of illicit trafficking of cultural objects; 07- The cultural heritage is not promoted for sustainable tourism development; 08- Practice of farming in and around the cultural heritage; 09- Adequate budget/ financial allocation for conservation of cultural heritage; 10- Little concern of government and local authorities about the heritage; 11- Professionals lack enough commitment to engage in conservation practices; 12- Media failed to expose the problems of heritage to the community in time; 13- Travel agents and tour operators are negligent to the sustainability of heritage; 14- Inappropriate conservation practices of cultural heritage; 15- Lack of buffer zone demarcations of the heritage sites; 16- Natural catastrophes and climate variations (flooding, frost, acidic rain, storm, heat from the sun) deteriorate cultural heritage; 17- Development projects such as buildings, roads affect the sustainability of heritage; 18- The heritage hosts more than its carrying capacity during different events; 19- Funding agencies lack willingness to provide aids and loans to cultural heritage; 20- There is no regular monitoring and evaluation of cultural heritage status by the concerned body; 21- The growth of vegetation over the heritage, and 22- The heritage are challenged by biological factor such as rat and other biological organisms.

The assumptions of relationship, randomness and sampling adequacy were checked in the analysis of exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

The descriptive statistics revealed that all the 22 linear component factors or variables have a mean value greater than 3 with a range varied from 3.41 to 3.95 for a total of 198 valid observations made for analysis. And, there was no missing data in the analysis.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity (see Table 5 ) also indicated that the sample size employed was adequate and the assumption is met with the KMO and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity value of 0.768 and Sig. = 0.000. A value varies between 0 and 1 where the value close to 1 indicates that patterns of correlations are relatively compact and so factor analysis should yield distinct and reliable factors. Kaiser [ 79 ] recommends accepting values greater than 0.5 as acceptable. Hence, the current value of KMO Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity meets the assumption [ 79 ].

The communalities table also presented the relationship of one of the variables with the other variables before rotation with which a value greater or equal to 0.30 indicates the employed sample is acceptable and results will not be distorted. The current finding has confirmed this assumption of factor analysis with the value ranging from 0.315 to 0.784 which is significantly above 0.30.

Factor extraction and variance explained

The present finding indicated that 59.51% of the total variance is explained by the seven factors extracted out of 21 linear components variables included in the model with Eigenvalues greater than one. Hence, the Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings indicated that the first factor contributed about 14.726% and the 2nd contributes 9.412% whereas the 3rd and 4th factors accounted for 8.808% and 7.503% of the variance explained. The 5th, 6th, and 7th factors contributed to about 7.222%, 6.509% and 5.325% of variance explained in cultural heritage conservation (see Table 6 ).

Factor rotation

The rotated factor matrix indicates the rotated component matrix (also called the rotated factor matrix in factor analysis) which is a matrix of the factor loadings for each variable on to each factor. The component loadings for each factor are positive that shows the positive relationship between the variable and each principal component. The values below 0.45 were suppressed while extracting the factors, and are not displayed in the rotated component matrix and the factor loadings were sorted by size. The orthogonal rotation was used with the assumption that the variables are independent of each other [ 80 ]. Before rotation, most variables loaded highly onto the first factor (21.554% variance explained) and the remaining factors didn't get a look in. However, the rotation of the factor structure has clarified things considerably with the equivalence of variance explained. As can be depicted in the rotated matrix table, there are seven components or factors that have been extracted as a factor hindering the management of cultural heritage conservation. Hence, Principal Component factor analysis with Varimax rotation was conducted to assess the underlying structure for the 22 items of the challenges of cultural heritage conservation practices. The assumption of independent sampling, normality, linear relationships between pairs of variables, and the variables being correlated at a moderate level were checked.

Seven factors were extracted after rotation, the first factor accounted for 14.726% of the variance and was composed of seven items related to lack of proper management, monitoring and evaluation, whereas the second factor accounted for 9.412% that consisted of a cluster of three variables that were related to lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement. The third factor accounted for 8.808% and it comprised of two items which are related to lack of government concern and professional commitment. The fourth factor consisted of three items and it is related to lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and promotion for sustainable development and accounted for 7.503%. The group of two items related to poor destination management and conservation practice make the fifth factor that accounted for 7.222% whereas the sixth factor accounted for 6.509% and comprises two items that are related to natural catastrophes and agricultural practices (see Table 7 ). The 7th factor encompasses only a single variable that is related to the lack of communities' positive attitudes towards cultural heritage.

Table 7 displays the items and factor loadings for the rotated factors, with factor loadings less than 0.40 omitted to improve clarity. Similar to the present study, heritage properties can be affected by the impacts of visitors such as overcrowding which may result in wear and tear including trampling, handling, humidity, temperature, pilfering and graffiti [ 75 ].

Mathematical representations of factor loadings

Like regression, a linear model of the mathematical equation can be applied to the scenario of describing a factor. The factor loadings are represented by b ‘s. According to Field [ 80 ], the equation can be written as.

Fi = b1X1i + b2X2i + … + bnXni.

Where Fi is the estimate of the ith Factor; b 1 is the weight or factor loading of variable X1, b2 is the factor loading of variable X2, bn is the factor loading of variable Xn, and n is the number of variables.

Accordingly, it was stated that seven factors were found underlying the construct Factors affecting cultural heritage conservation. Consequently, an equation can be constructed for each factor in terms of the items that have been measured.

Factor 1 = 0.671(X1) + 0.668 (X2) + 0.664 (X3) + 0.626(X4) + 0.571 (X5) + 0.571 (X6) + 0.485(X7).

By substituting the mean value of each item (question), the approximate percentage variance that factor 1 can explain can be calculated.

Factor1 = 0.671(3.58) + 0.668 (3.36) + 0.664 (4.33) + 0.626(3.60) + 0.571 (3.60) + 0.571 (2.88) + 0.485(2.86) = 14.2

Factor 2 = 0.742(X8) + 0.710(X9) + 0.576(X10) = 0.742 (4.53) + 0.710(4.42) + 0.576(4.72) = 9.23.

Applying similar formula for the remaining factors, and adding the calculated values together, or the summation of all factors will be a total of 58.51 which means using the mathematical equations, the seven factors together can explain 58.51% of the variance. As explained before in the total variance explained in Table 7 , in the rotated sums of squared loadings column, it has been said that the seven components explained 59.51% of the variance. Hence with a minor difference, values calculated from the equation and summations of a percentage of variance in the total variance explained Table 7 provide an approximately similar result. The difference may be resulted either from using the approximate values after the decimal point or the factor loadings less than 0.4 that were suppressed.

After conducting the exploratory factor analysis and extracting the seven factors, the multiple linear regressions was applied to confirm which factors affect the practice of cultural heritage conservation.

Assumptions of multiple linear regression

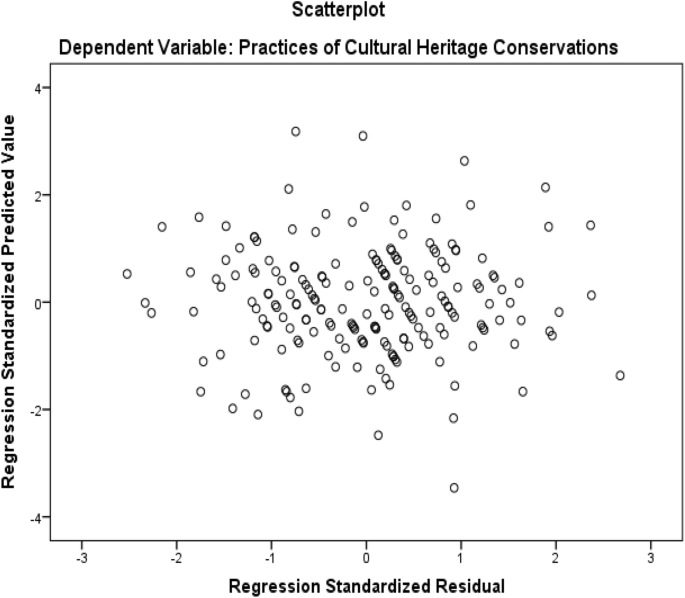

The relationship between the independent variable and dependent variables is linear. This assumption was confirmed as it is reflected by the scatter plot that showed the relationship is linear for all independent variables: lack of proper management, monitoring and evaluation, lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement, lack of government concern and professional commitment, lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and promotion towards sustainable development, poor destination management and conservation practice, natural catastrophes and agricultural practices, and the local community have no positive attitude towards cultural heritage conservation.

There is no multicollinearity in the data set. Multicollinearity exists when the correlation coefficient r between independent variables is above 0.80. Hence, no independent variable was found to have multicollinearity problems with each other with all below 0.80 where the highest Pearson correlation value of 0.688. Besides, the multicollinearity issue can be checked by VIF and tolerance level where VIF is below 10 and tolerance level > 0.20 [ 81 ]. Hence, VIF and Tolerance are found within the acceptable region.

The values of the residual are independent. The residuals of the data set in the sample stratum were found independent or uncorrelated which can also be tested based on Durbin-Watson statistics (above one and below 3). The Durbin Watson statistics is 1.821.

The assumption of homoscedasticity: the assumption that shows the variation in the residual is a similar constant at each point of the model. As it can be shown, the closer the data points to a straight line when plotted, the points are about the same distance from the line meaning the data points have the same scatter. This can be shown by the normality probability curve of the scatter plot (see Fig. 3 ).

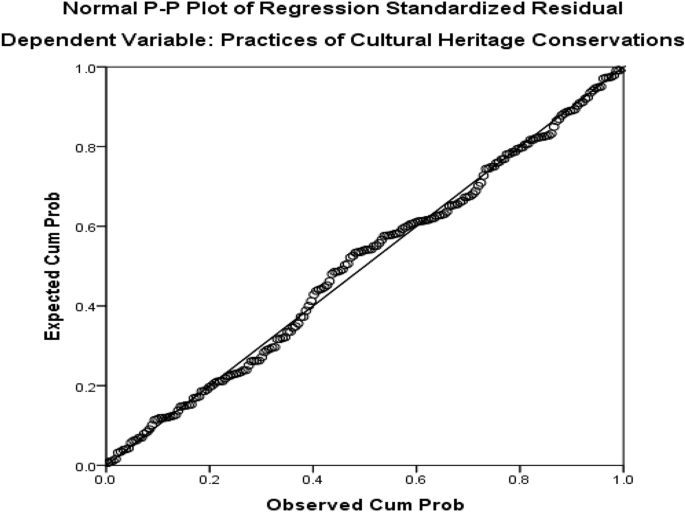

The values of the residual are normally distributed. This assumption can be tested by looking at the p-p plot for the model. The closer the dote lies to the diagonal line; the closer to normal the residuals are distributed. The normal p-p plot dotes (see Fig. 4 ) line indicates that the assumption of normality has not to be violated.

Scatter Plot; Conservation of Cultural Heritage (Field Survey, 2021)

Normal P-P Plot of Dependent Variable (Field Survey, 2021)

Regression results

The Pearson`s correlation table indicates (see Table 8 ) that there was a significant relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable i.e. cultural heritage conservation at a p value of 0.05 level of significance. However, lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement, poor destination management and conservation practice and lack of the local community positive attitude towards cultural heritage were not significantly correlated with the cultural heritage conservation practice (r = 0.057, sig = 0.212; r = − 0.008, sig. = 0.458 and r = 0.016, Sig = 0.410). Thus, the indicators were removed from the regression model.

The Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) table (see Table 9 ) exhibits the goodness of fit of the model and revealed the model is appropriate and the introduction of the independent variables has improved by at least one predictor (P = 0.001) significant at 1% level of significance. Thus, the model is the best-fitted model presenting the regression that presents the significant independent variables that significantly explain the dependent variable.

The model summary shows the predicted variable i.e. practices of cultural heritage conservation is explained by the introduced independent variables viz., natural catastrophes and agricultural practices, lack of community concern, illicit trafficking, promotion towards sustainable development, lack of government concern and professional commitment, and lack proper management, monitoring and evaluation accounted for 7.9% with an adjusted R square value of 0.079 (see Table 10 ). The variance explained in the model summary table is also supported by the coefficients table that exhibited some of the extracted factors that were significant.

The coefficient result shows that the largest β value is the greatest predictor of heritage conservation. Among the independent variables, lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and promotion towards sustainable development was found the most significant factor affecting practices of cultural heritage conservation (β = − 0.213, p < 0.05) followed by natural catastrophes and agricultural practices (β = − 0.132, p < 0.05). Besides, lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement was the factor found to be significant β-value (β = 0.179 & Sig. = 0.007). Furthermore, there was a negative relationship between lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and promotion towards sustainable development, and natural catastrophes and agricultural practices with the predicted variable.

As far as this study was concerned, lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and lack of promotion towards sustainable tourism development with β = − 213; p. = 0.002 and natural catastrophes and agricultural practices in and around the cultural heritage with β = − 0.132; p = 0.026 were found to be significant challenges hindering the heritage conservation practices (see Table 11 ). This finding was confirmed by the previous studies that revealed air pollution; biological causes like invasive intervention, humidity and vandalism have negative consequences on the survival of heritage tourism. The present finding was also in line with the findings of Irandu and Shah [ 82 ] that portrayed the cultural heritage conservation of Kenya faced challenges such as funding, poor enactment of policies, land grabbing and lack of adequate trained personnel. Besides, another finding revealed that tackling the calamities of climate change mainly global warming and extreme weather events combined with the implementation of varied strategies to moderate the impact of a growing tourist demand towards heritage sites become the growing problem in the conservation efforts of cultural heritage conservation which supports the present finding [ 83 ]. This finding also revealed the land use issue is an emerging problem for conservation. Therefore, the present study underlines that effective planning, proper land use strategy and environmental conservation policies shall be enhanced by the local and national governments.

Unlike the present study, as noted in the work of Eken, Taşcı, and Gustafsson [ 16 ] public participation along with governmental strategies is vital to deciding preventive conservation. Their finding indicated that local communities have an awareness regarding the significance and preservation of the World Heritage Site of Visibility, but they were not adequately cognizant of the practical aspect of preservation. The other issues raised by the authors are difficulties concerning guidance and promotion of regular maintenance which is also similar to the present study. Besides, restoration works have been carried out without a detailed report of the current condition of the cultural heritage [ 16 ]. On the opposite, the interview was found in line with the aforementioned previous study revealing the disintegration of the heritage concerned authorities, the poor intervention of the government and inadequate collaboration of the local and regional governments with the local communities. Besides, the political implication of understanding the heritage also nailed our challenge in the conservation of cultural heritage. Similar to the present finding, the study scrutinized owing to conflicting claims, representations and discourse of urban heritages become contested [ 84 ]. Unlike the present finding, the study of Tweed and Sutherland [ 85 ] indicates that conserving heritage properties contributes to the sustainability of the built environment, and it is a crucial element of the cultural identity of the community which describes the character of a place.

Moreover, lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement was identified as a significant challenge with β = 0.179; p = 0.007 in the present study. The previous findings revealed that the lack of collaborations to date in terms of managing the assets between the local authority and other stakeholders was found a significant challenge in cultural heritage conservation [ 86 ]. The findings of this study were supported by the findings of the previous study on the adaptation of land use for new purposes and functions, especially for the heritage buildings which demand new strategies for the indoor quality and efficiency of heritage for the new functional use was found the challenge that affects heritage conservation and management of heritage sites [ 83 ]. To overcome this problem, stakeholder collaboration and involvement, community empowerment and the adaptive reuse approach should be adopted that in turn increases the tourism demand and receipts which again escalate the multiplier effects within the industry combined with the job creation [ 87 ] and livelihood diversification through the enhancement of conservation enterprises around protected areas [ 88 ]. It is argued that cultural heritage sustainability relies on training and education that can produce competent human capital who are in charge of heritage protection and promotion [ 89 ]. The cultural heritage understudy is facing various natural and manmade problems which were verified by the interview made with officials of ARCCH who are working at the department of Heritage Restoration and Conservation (Personal communication, 21 June 2021) that revealed structural problems of the heritage authority from federal to the local level, lack of skilled manpower, and lack of clear proclamations and guidelines regarding private heritage conservation. This finding was supported by the technical aspects such as limited availability of experts (lack of skilled forces, absence of educational training for new skills, and lack of technical staff in the heritage maintenance team) and availability of original or authentic materials were the major constraints in conservation projects [ 90 ]. Besides, the interviewees added lack of sufficient funds for restoration and conservation and the difficulty of conservation of heritage in and nearby urban areas due to urbanization and urban renovation were significant challenges for conservation. In line with the interview, the findings of Dias Pereira et al. [ 83 ] pinpointed the conservation of cultural heritage and the maintenance of its original characteristics and identity which could have been exacerbated by the unavailability of raw materials for conservation. Moreover, the unavailability of raw materials for restoration and maintenance of heritage, and keeping authenticity was found a very serious problem in the applicability of cultural heritage conservation practices [ 91 ]. Besides, there is an increasing interest to replace old cultural heritage with modern buildings, and hiding movable heritage are problems in escalating conservation efforts. An ideal example is the church of Ankober Medahnealem Church where only remnants or ruins of buildings are visible and the historical ruins of old church was replaced with the new modern buildings. Generally, the finding of the present study indicates the various challenges that should be overcome to assure the sustainability of cultural heritage. This was also supported by the study of [ 85 ], whose heritage conservation theme encompasses technical, environmental, organizational, financial and human issues.

Practical implications

There should be a mechanism and plan to evaluate, follow up and supervise the conservation status of heritage side by side with the activities of heritage inventory made each year in each study area by the respective district. In this regard, it has been suggested that heritage sites shall receive an urgent response from the government in collaboration with the host community [ 92 ].

Appropriate guidelines for conservation should be developed based on research and scientific evidence to escalate the conservation practices. In line with this, to make the conservation effort effective, the right heritage management professionals and appropriate mapping guidelines should be hired to conduct the management of cultural heritage conservations and preservations [ 92 , 93 ].

Besides, conservation activities should be made through allocating sufficient budget, training, technical support and human resources equipped with the latest technology and required raw materials to keep the authenticity of the heritage.

Furthermore, heritage conservation funds should be organized institutionally and come into the practice to support conservation efforts. The local communities, the private travel and tourism organizations and government bodies should be engaged in the planning, execution and monitoring of the heritage conservation and renovation process. In addition, better platforms for stakeholder collaboration should be developed and management of conflict of interest threats should be seriously addressed. The study of Aas, Ladkin, and Fletcher [ 94 ] recommended that the function of involving the local communities and all other key stakeholders in decision making and the view of right participation which in turn can empower the stakeholders’ engagement in conservation activities [ 66 , 95 ].

Though there are a few attempts, especially at Angolela Kidanemihret Site at King Sahle Sellassie Palace and Goze Mosque, the practices of cultural heritage conservation were found to be very low which needs to be enhanced to assure the sustainability of cultural heritage. The finding of this study revealed that local communities feel as if the heritage belongs to them and consider it as part and parcel of their identity. However, conservation of activities was not based on research, conservation practices and the status of heritage follow-up are not made on regular basis and capacity buildings are not provided for the sustainable conservation of cultural heritage in the study areas.

Concerning the status and practice of cultural heritage conservation, lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and promotion of sustainable tourism development and natural catastrophes and agricultural practices in and around the cultural heritage were found to be significant factors affecting the heritage conservation practices in the study areas. Lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement around the heritage sites were also identified as the challenges hindering the conservation of cultural heritage and their environs. On top of these, lack of government concern, community interest, lack of appropriate funding and skilled manpower were also found to be significant factors that hinder the practices of conservation of cultural heritage. Moreover, the structural weakness of the heritage-related government institutions and political implication of leaders and the urbanization and urban renovation programs added are exacerbating the existence and practices of cultural heritage conservation. From the findings of the present study, it can be understood that the conservation of cultural heritage is not an easy task which cannot be undertaken by a single actor such as the government or heritage destination managers. The multitude of the contribution of various relevant stakeholders is demanding to upscale the conservation efforts and grant sustainability of cultural heritage. The sustainable conservation of cultural heritage will also be important for the wise use of the heritage for many purposes such as a means for enhancing socio-cultural ties, building the image of a place or destination and fosters tourism development.

Generally, poor conservation practices of cultural heritage and insufficient commitment of concerned bodies to conserve cultural heritage exacerbated by various manmade and natural factors demand strong and vivid solutions to the problems to reverse the existing severe conditions of the cultural heritage. The present study revealed that the likelihood of cultural heritage conservation highly depends on not only man-made bottlenecks but also natural catastrophes such as flooding, climatic variations and invasive species. Thus, to improve the effective conservation and use of cultural heritage, especially in developing countries like Ethiopia, government and political leaders’ positive attitude and understanding of the relevance of cultural heritage to the society and the country at large should play a fundamental role in this regard. The improved view of the leaders toward cultural heritage has the potential to enhance funding possibilities and pave the way for a meaningful participation of stakeholders.

Moreover, the enhancement of conservation practices and sustainable use of cultural heritages should be supported through proper land use planning around heritage sites, preparation of heritage conservation plans and efficient heritage destination management. This tells us the practices of conservation efforts for cultural heritage and heritage sites demand the involvement of various actors from various sectors viz., tourism, agriculture, government administration bodies, religious and community institutions and heritage conservation organizations, environmentalists and development agencies to assure sustainability and community benefits from the heritage.

Furthermore, the conservation of cultural heritage shall be seen in a wider scope beyond the conservation of heritage property itself. It should include the vitality of cultural heritages for promotion of destination and country image, enhancement of socio-cultural bondage, and serving as a tool of economic integration through tourism. Therefore, a system of management of cultural heritage needs to be developed that takes significant issues and challenges into consideration through participatory decision-making process to optimize the values and sustainability of cultural heritage in Ethiopia.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Analysis of Variance

Authorities for Research and Conservation of cultural heritage

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNESCO. Globalization and intangible heritage. Belgium; 2005.

Kurin R. Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage in the 2003 UNESCO convention: a critical appraisal. Mus Int. 2004;56(1–2):66–77.

Article Google Scholar

Bolin A. Imagining genocide heritage: material modes of development and preservation in Rwanda. J Mater Cult. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183519860881 .

Bleibleh S, Awad J. Preserving cultural heritage: shifting paradigms in the face of war, occupation, and identity. J Cult Herit. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2020.02.013 .

UNESCO. Safeguarding intangible heritage and sustainable cultural tourism: opportunities and challenges. UNESCO-EIIHCAP Regional Meeting.Hué; Viet Nam; 2007.

FDRE (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia). The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Cultural Policy. Addis Ababa: FDRE. 1997.

Ministry of Culture and Tourism, ARCCH and UNESCO. Meeting on inventorying; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2007.

Mengistu G. Heritage tourism in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2008.

Pietrobruno S. Cultural research and intangible heritage. J Curr Cult Res. 2009;1(2):227–47.

Nesbeth G.Art and globalization: the place of intangible heritage in a globalizing environment, Ph.D. dissertation. University of South Africa.2013.

Lévi-Strauss C. Anthropology confronts the problems of the modern world. Cambridge, London, England: Harvard University Press; 2013.

Google Scholar

ICOM‐CC (International Council for Museums – Conservation Committee).Terminology to Characterize the Conservation of Tangible Cultural Heritage. 2008., http://www.icom‐cc.org/242/about‐icom‐cc/what‐is‐conservation. Accessed September 14 2020.

Begashew K. The Archaeology of Islam in North East Shoa. 16th International conference of Ethiopian Studies. 2009; 11–22.

Omer AH. Centres of traditional Muslim education in Northern Shäwa (Ethiopia): a historical survey with particular reference to the twentieth century. J Ethiopian Studies. 2006;39(1/2):13–33.

Stiffman E. Cultural Preservation in Disasters, War Zones. Presents Big Challenges in the Chronicle of Philanthropy. 2015.

Eken E, Taşcı B, Gustafsson C. An evaluation of decision-making process on maintenance of built cultural heritage: the case of Visby Sweden. Cities. 2019;94:24–32.

Herzfeld M. A place in history: social and monumental time in a Cretan town. Princeton New Jersey, UK: Princeton University Press; 1991.

Babb FE. Theorizing gender, race, and cultural tourism in Latin America: a view from Peru and Mexico. Lat Am Perspect. 2012;39(6):36–50.

Olwig KF. The burden of heritage: claiming a place for a West Indian culture. Am Ethnol. 1999;26(2):370–88.

During R. Cultural heritage and identity politics. Hong Kong, China: Silk Road Research Foundation; 2011.

Koiki- Owoyele AE, Alabi AO, Egbunu AJ. Safeguarding Africa’s cultural heritage through digital preservation. J Applied Inform Sci Technol. 2020;13(1):76–86.

Moseti I. Digital preservation and institutional repositories: case study of universities in Kenya. J South African Society Archivists. 2016;49:137–54.

Karin C, Philippe D. Preserving intangible cultural heritage in Indonesia: A pilot project on oral tradition and language preservation UNESCO. Jakarta: Indonesia; 2003.

Czermak K, Delanghe P,Weng W. Preserving intangible cultural heritage in Indonesia. In Conference on Language Development, Language Revitalization and Multilingual Education in Minority Communities in Asia. 2003; 1–8.

Truscott M. Intangible values as heritage in Australia. Hist Environ. 2000;14(5):22–30. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.591886148622588 .

Munjeri D. Intangible heritage in Africa: could it be a case of much ado about nothing? ICOMOS Newsletter; 2000. Retrieved from https://www.international.icomos.org/munjeri-eng.htm . Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Roy D, Kalidindi S. Critical challenges in the management of heritage conservation projects in India. J Cult Heritage Manag Sustaina Dev. 2017;7(3):290–307.

Berhanu E. Potentials and challenges of religious tourism development in Lalibela, Ethiopia. African J Hosp Tour Leis. 2018;7(4):1–17.

Wharton G. Indigenous claims and heritage conservation: an opportunity for critical dialogue. Public Archaeol. 2005;4(2–3):199–204.

Le Mentec K. The Three Gorges Dam Project—Religious Practices and Heritage Conservation. A study of cultural remains and local popular religion in the xian of Yunyang (municipality of Chongqing). China Perspectives. 2006;65:1–15. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.626 .

Navaneethakrishnan S. Preservation and documentation of intangible cultural heritage: the Strategic Role of the Library and Information Science Professionals in Sri Lanka. J Univ Librarians Association Sri Lanka. 2013;17(1):58–65.

Brosché J, Legnér M, Kreutz J, Ijla A. Heritage under attack: motives for targeting cultural property during armed conflict. Int J Herit Stud. 2017;23(3):248–60.

Azzouz A. A tale of a Syrian city at war. City. 2019;23(1):107–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2019.1575605 .

Danti M, Branting S, Penacho S. The American schools of oriental research cultural heritage initiatives: monitoring cultural heritage in Syria and Northern Iraq by Geospatial imagery. Geosciences. 2017;7(4):1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences7040095 .

Cunliffe E, Pedersen W, FiolM, Jellison T, Saslow C,Bjørgo E, Boccardi G. Satellite-based Damage Assessment to Cultural Heritage Sites in Syria . A report submitted to United Nations Institute for Research and Training. Geneva: Switzerland; 2014; Retrieved from https://unosat.web.cern.ch/unitar/downloads/chs/FINAL_Syria_WHS.pdf . Accessed 20 May 2021.

Muddie E. Palmyra and the radical other on the politics of monument destruction in Syria : deliberate destruction of heritage properties. Otherness: Essays and Studies. 2018;6(2):140–60.

Clapperton M, Jones M, Smith R. Iconoclasm and strategic thought: Islamic State and cultural heritage in Iraq and Syria. Int Aff. 2017;93(5):1205–31.

Fisher J. Violence against architecture: The lost cultural heritage of Syria and Iraq. 2017; City University of New York. Thesis. Retrieved from https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi. Accessed on 30 March 2022 http://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1898 .

Wollentz G. Making a home in Mostar: heritage and the temporalities of belonging. Int J Herit Stud. 2017;23(10):928–45.

Wierczynska K, Jakubowski A. Individual responsibility for deliberate destruction of cultural heritage: contextualizing the ICC judgment in the Al-Mahdi case. Chin J Int Law. 2017;16(4):695–721.

Jakubowski A. Resolution 2347: Mainstreaming the protection of cultural heritage at the global level. Questions International Law. 2018;48:21–44.

Kalman H. Destruction, mitigation, and reconciliation of cultural heritage. Int J Herit Stud. 2017;23(6):538–55.

Zarandona J, Albarrán-Torres C, Isakhan B. Digitally mediated iconoclasm: the Islamic State and the war on cultural heritage. Int J Herit Stud. 2018;24(6):649–71.

Harrowell E. Looking for the future in the rubble of Palmyra: destruction, reconstruction, and identity. Geoforum. 2016;69:81–3.

Mancacaritadipura G. Safeguarding the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Indonesia: Systems, Schemes, Activities and Problem. In The 30th International Symposium on the Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Property, Japan; 2007.

Mike R, David P. Tourism, culture and sustainable development. UNESCO : Spain: Madrid. 2006.

UNESCO. Safeguarding Intangible Heritage and Sustainable Cultural Tourism: Opportunities and Challenges. Bangkok; 2008

Xulu, M. Indigenous Culture, Heritage and Tourism: An Analysis of the Official Tourism Policy and Its Implementation in the Province of Kwazulu-Natal: A Thesis submitted To the Faculty of Arts in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Centre for Recreation and Tourism at the University of Zululand. 2007.

MohdAriffin NF, Ahmad Y, Alias A. Stakeholders’ Attitude on the Willingness-To-Pay value for the conservation of the George Town, Penang World Heritage Site. J Survey Construct Property. 2015;6(1):1–10.

Eleonora L. Intangible Cultural Heritage Valorization: A New Field for Design Research and Practice. Italia: Milano; 2007.

European Construction Technology Platform. Cultural heritage guide, technology integration division: Travel world news section. 2008.

UNESCO-ICOMOS. Documentation Centre.Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage.2011.

Richard K . Museums and Intangible Heritage Culture Dead or Alive? : ICOM news. 2004

Jamieson W. The Challenges of Sustainable Community Cultural Heritage Tourism. Asian Institute of Technology: Bangkok, Thailand; 2000.

Rukwaro R. Community participation in conservation of gazetted cultural heritage sites: a case study of the Agikuyu shrine at MukurwewaNyagathanga. In: Deisser AM, editor. Conservation of Natural and Cultural Heritage in Kenya. London: UCL Press; 2016. Retrieved from https://ucldigitalpress.co.uk/Book/Article/19/44/1421/ . Accessed 19 Jan 2022.

Boonyakiet C. Introduction to the Intangible Cultural Heritage and Museums Field School by Alexandra Denes, Anthropology Centre, Thailand Intangible Cultural Heritage and Museums Learning Resources. 2011.

Gursoy D, Zhang C, Chi OH. Determinants of locals’ heritage resource protection and conservation responsibility behaviors. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2019;31(6):2339–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0344 .

Sinamai A. African cultural heritage conservation and management: theory and practice from southern Africa. Conserv Manag Archaeol Sites. 2018;20(1):52–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2018.1430444 .

Tadesse B. Visual representation in the Ethiopian orthodox church: church paintings and conservation problems. Asian Man Int J. 2012;6(1):1–7.

Haspel J. Contrast versus context: A conflict between the authenticity of the pastand the authenticity of the present? In Conservation and Preservation: Interactions between Theory and Practice: In Memoriam AloisRiegl (1858–1905): Proceedings of the International Conference of the ICOMOS International Scientific Committee for the Theory and the Philosophy of Conservation; Polistampa: Vienna, Austria; 2008; 1000–1017.

Umar SB A Conservation Guideline for Traditional Palaces in Nigeria for the Resilience of Cultural Heritage and Identity in a Cultural Milieu Universiti Teknologi Malaysia: Skudai: Malaysia; 2018

Vaccaro A. Restoration and anti-restoration. In: Historical and Philisophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute; 1996. p. 308–13.

YazdaniMehr S. Analysis of 19th and 20th century conservation key theories in relation to contemporary adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Heritage. 2019;2(1):920–37.

Hailu WA. Prospects for Environmental Protection and Eco-Tourism in Semen Shewa. A Project Proposal. Retrieved from http://www.cyberethiopia.com/net/docs/hailu.pdf . Accessed 18 Mar 2021.

Adane Y. Practices and Challenges of Cultural Heritage Conservation in Ethiopia: The Case of Ankober, Ethiopia. 2019.

Abebayehu B. Key stakeholders’integration for religious heritage site conservation: The case of AngolelaSemineshKidanemihret Monastery North Shewa Zone, Ethiopia. Doctoral Dissertation: University of Gondar; 2021.

Taherdoost H. Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. SSRN Electronic J. 2016. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3205040 .

Carmines EG, Zeller RA. Reliability and validity assessment. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage Publications; 1979.

Book Google Scholar

Cronbach LJ, Warrington WG. Time-limit tests: estimating their reliability and degree of speeding. Psychometrika. 1951;16(2):167–88.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53.

Sharma B. A focus on reliability in developmental research through Cronbach’s Alpha among medical, dental and paramedical professionals. Asian Pac J Health Sci. 2016;3(4):271–8.

Ekwelem VO, Okafor VN, Ukwoma SC. Preservation of cultural heritage: The strategic role of the library and information science professionals in South East Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice, 2011. p. 14

Sterling C. Critical heritage and the posthumanities: problems and prospects. Int J Herit Stud. 2020;26(11):1029–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1715464 .