What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Rawan Elbaba, Student Reporting Labs Rawan Elbaba, Student Reporting Labs

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/why-on-screen-representation-matters-according-to-these-teens

Why on-screen representation matters, according to these teens

Why does representation in pop culture matter?

For some young students, portrayals of minorities in the media not only affect how others see them, but it affects how they see themselves.

“I do think it’s powerful for people of a minority race to be represented in pop culture to really show a message that everybody has a place in this world,” said Alec Fields, a junior at Forest Hills High School in Pennsylvania.

Fields was one of 144 middle and high school students who were interviewed about seeing themselves reflected — or not — on the screen. PBS NewsHour turned to our Student Reporting Labs from across the country to hear what students had to say a topic that research shows still has room for growth.

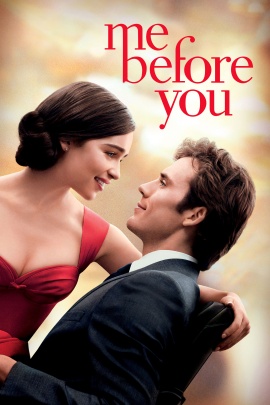

The success of recent films like “Black Panther” and “Crazy Rich Asians” have — again — sent a message about the importance of representation of minorities, not only in Hollywood but in other aspects of pop culture as well.

Only two out of every 10 lead film actors (or 19.8 percent) were people of color in 2017, this year’s UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report found. Still, that’s a jump from the year before, when people of color accounted for 13.9 percent of lead roles. People of color have yet to reach proportional representation within the film industry, but there have been gains in specific areas, including film leads and overall cast diversity.

According to 2018 U.S. Census Bureau estimates , the nation’s population is nearly 40 percent non-white. By 2055, the country’s racial makeup is expected to change dramatically, the U.S. will not have one racial or ethnic majority group by 2055, the Pew Research Center estimated .

Some students said that not seeing yourself represented in elements of pop culture can affect mental health.

“It just makes you feel like, ‘Why don’t I see anybody like me?’ [It] kind of like brings your self-esteem down,” said Kimore Willis, a junior at Etiwanda High School in California.

Others said they often look to trends in pop culture when forming their own identities.

“We need to see people that look like ourselves and can say, ‘Oh, that looks like me!’ or ‘I identify with that,’” said Sonali Chhotalal, a junior at Cape May Technical High School in New Jersey.

Others, however, feel that Hollywood is overcompensating for their lack of diversity by depicting exaggerated and stereotypical characters.

Eric Wojtalewicz from Black River Falls High School in Wisconsin said that he sees a lot of gay characters that seem “over-the-top,” playing on old tropes. “I definitely think that not all gays are like that,” he said.

Kate Casper, a junior at T.C. Williams High School in Virginia, called Hollywood’s attempt at diversity “disingenuous.” Although there can never be enough diversity, Casper said, she feels that the entertainment industry is using diversity for economic benefit. “Diversity equals money in today’s world, which is cool, I guess,” she said, adding that “it’s cooler to have pure motives.”

The UCLA report agrees that diversity sells. It says that the median global box office has been the highest for films featuring casts that were more than 20-percent minority, making nearly $450 million in 2017.

Although public opinion may be divided about whether the entertainment industry is doing enough to represent all types of people, South Mountain High School student Dazhane Brown in Arizona said that feeling represented is “empowering.”

“If you see people who look like you and act like you and speak like you and come from the same place you come from … it serves as an inspiration,” Brown said.

PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs produced this story in an effort to highlight the importance of representation of minorities in popular culture. Students from 31 Labs across the country submitted these responses.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Why Jane Fonda is putting herself on the line to fight climate change

Arts Nov 07

The importance of representation

When I write creatively, I write about white people. Not the same white person, sure: There’s the awkward misunderstood white person, or the rich white woman destined to solve crime or the hard working white man that robs a store at gunpoint. Sitting in a conference with my creative writing teacher, I told her I’m scared to write about things that I don’t know.

I fell in love with writing as I fell in love with books. I would read the Magic Tree House, Judy Bloom, Andrew Clements and Ann M. Martin during lunch, at recess, in my room when the lights were meant to be off. I told myself I would be a writer — that I could be a writer. On the covers of my second grade novels I’d draw a girl, using the peach shade crayon, and name her Grace. Or Lindsay or Abby or Charlotte. This is a girl I felt I knew. She was all around me, in my white school, in my white town. She was on Disney Channel and Nickelodeon. She was on magazines and American Girl dolls. As I got older, this white wash became more apparent. Classical literature praises this peach-shade figment: Jane Eyre, Elizabeth Bennet, Anna Karenina. These adventurous yet respectful white women — I eventually branched out to white men — became my muse.

Representation in the media is a constant source of controversy. For decades, award shows like the Oscars and Grammys have consistently overlooked the work of black artists. Black Panther is proving to be one of the most influential movies of our time with its assertion of black power both in its plot and cast. Many other films and TV shows released in the past few years have sought to provide representation for minority groups in the media. Representation isn’t just a nice way to appease complaining minorities. The media is a reflection of who America is and isn’t. America isn’t just white, and it never has been. When America looks into a mirror, the reflection is white, Christian, financially well-off. The picturesque American citizen.

I, along with so many people of color, write about white people because that is the only face the media deems as a full character. The complexity awarded to white Americans in the media is not seen in minority characters. There is no drive to explore the sassy black sidekick when there’s the multi-faceted white person. There is no incentive to explore minority characters when they exist to further stereotypes. I assumed this was normal. Fiction is about channeling something ideal or fantastical. In my childhood, the ideal was always white. Black people were side characters or villains. They were thugs or drug lords. They were never the hero. The media is partially responsible in the process of constructing what blackness and whiteness are, and in America, the furthering of racial stereotypes only helps justify racist actions. The fight for adequate representation isn’t a new thing. Amazing people have been advocating for cultural diversity in the media since before I was born. But there is more work that needs to be done.

We are in such a place where fundamental American thought can be shifted. Right now, minorities are starting to be listened to. Minorities have been yelling for decades at a country that doesn’t acknowledge us as part of its cultural makeup. Now there are more movies, TV shows, podcasts, models, activists that are beginning to be appreciated and listened to. This is the time. Children don’t have to write about peach-colored girls. The foundations created finally have room for some footing. By pushing for representation, we can change the way America is seen by Americans. When media is white, the stories of the marginalized, of racism, unfair housing, income inequality are never told. The media is a way to bring stories to life. The complexities of different races are not realized by most Americans because they are not visible to most Americans. The media is a pivotal start in forcing Americans to confront the harsh truth of our current political dynamic. Our media is silencing the voices of millions.

Representation is a vicious cycle. We write about what we see and what we experience. When all we study is white and all we see is white, all we create is white. I applaud the great authors and thinkers that have managed to test these boundaries, to push our current media and literature out of balance. They inspire young writers like me to explore the unseen characters, the traditional sidekicks, the never forgotten villains. They also encourage us to find characters in our own identity. We are encouraged to write characters with our strength and weaknesses and flaws.

Everyday, the media reassures us that America is white. Minorities are sidekicks or the help, the American Dream is alive and well, and racism is dead. Representation in the media means that America can finally see itself in all its multicultural, multiracial, beautiful self. Representation in the media means that America sees more to minorities than stereotypes. Representation can make disadvantaged groups become real people.

Contact Natachi Onwuamaegbu at natachi ‘at’ stanford.edu.

Natachi Onwuamaegbu is a freshman from Bethesda, Maryland. She is currently undecided but is leaning towards Political Science and English. Currently, Natachi is part of the Black Student Union and hopes to run a radio station on campus. When she's not wandering around campus, Natachi likes to sit in the sun, listen to music and overuse semi-colons.

Login or create an account

Apply to the daily’s high school summer program, priority deadline is april 14.

- JOURNALISM WORKSHOP

- MULTIMEDIA & TECH BOOTCAMPS

- GUEST SPEAKERS

- FINANCIAL AID AVAILABLE

- Family Life

- Kindergarten Help

- Personal Stories

- Preschool Help

- Tweens & Teens

Why Is Representation So Important?

I was born in 1950, the youngest of five children in a white, working-class family living in a predominately blue-collar neighborhood in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. There were not many books in my household, but I distinctly remember the “Dick and Jane” series, which were the school textbooks that were used to teach reading, back in the day. And I definitely remember the illustrations and how the families in those books were portrayed.

Television shows like “ Father Knows Best,” “The Donna Reed Show,” and “ Ozzie and Harriet “reinforced a father’s image, always dressed in a suit and tie, which was not a common sight in my community. I remember asking my mother why my father or any of the dads we knew didn’t dress like the fathers represented in those books or on the TV shows we watched.

I have heard from friends who are Black describe what happened in their homes during that same time period when a person of color appeared on television… everyone in the family would excitedly come running to witness this rare occurrence.

These anecdotes illustrate a child’s natural inclination to look for a reflection of themselves in the world around them. This is what representation – or the portrayal of a person or group in books and other media—is all about.

And it matters!

Children need to see themselves included and represented, and that representation should be truthful and not based on stereotypes. How people are depicted shapes how they see themselves and how others see them. It also defines or limits possibilities that one can aspire to depending on whether the representation is positive or negative.

For those readers who responded to my recent blog: Should We Continue To Celebrate Dr. Seuss? with a “don’t like it, don’t read it” reaction, I would counter that continuing to publish children’s books with offensive illustrations sends the wrong message to anyone who comes across them. It is crucial for all children to be exposed to truthful and positive images, not just non-white children; otherwise, we as Americans have no chance at becoming a better nation where all are seen, heard, and treated equally.

I hold out little hope for any mutual understanding from those respondents who replied with hate and disdain to my posting.

But I was heartened to hear from people who said they reconsidered their impulse to roll their eyes at the Dr. Seuss news. While they frankly expressed fatigue at times with the reexamination of misguided and immoral thinking and actions from the past, they acknowledged that they had discovered some understanding of the power of representation with further consideration. Many offered that when they recognized the significance of negative and offensive illustrations and how they contribute to division and hate—which is on the rise—they realized this fatigue was nothing compared to what non-white individuals had and continue to experience.

I have always cringed when people talk about the “good old days.” While I have many fond memories of the past, I am quick to recognize that it was far from perfect. I acknowledge that women, people of color, and any group considered to be “other” had to be submissive in that past. And that there were unjust laws in place or the mores of the time that limited the freedom of many of our citizens. That history must be confronted and identified for what it was…wrong. Calling it out doesn’t cancel anything or take away from what was positive about those times, nor does it proclaim that everything nowadays is ideal and without reproach.

Fortunately, progress is being made and representation in books and other media is becoming more inclusive and more positive; that said, we need to be vigilant in looking honestly at the past, as well as critically at how people are represented going forward.

Need some fresh ideas?

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for expert parenting tips and simple solutions that make life instantly better.

By subscribing you agree to Tinybeans Terms and Privacy Policy

Related reads

Why Are Gen Z Kids Covering Their Noses in Family Photos?

Screen Time for Babies Linked to Sensory Differences in Toddlerhood, Study Shows

Kids Shouldn’t Have to Finish Dinner to Get Dessert, Dietitian Explains

The Questions Parents Should Be Asking Their Pediatrician—but Aren’t

6 Better Phrases to Say Instead of ‘Be Careful’ When Kids Are Taking Risks

- your daily dose

- and connection

- Your daily dose

The power of political representation

Lisa Jane Disch, Making Constituencies: Representation as Mobilization in Mass Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021)

- Critical Exchange

- Open access

- Published: 16 December 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lawrence Hamilton 1 , 2 ,

- Monica Brito Vieira 3 ,

- Lisa Disch 4 ,

- Lasse Thomassen 5 &

- Nadia Urbinati 6

1265 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This Critical Exchange takes up a conversation David Plotke inaugurated twenty-five years ago with this simple statement: ‘Representation is democracy’ ( 1997 ). This sentence announced a unique and powerful reframing that ‘transformed what was commonly believed to be an oxymoron into an equivalence’, as Mónica Brito Vieira so aptly and eloquently described it ( 2017 , p. 6). Rather than promote representation from the typical standpoint of republicanism, Plotke took up a vantage point informed by and grateful for the successes of twentieth-century democratic movements. By extending voice and rights to the formerly marginalized and replacing ‘direct personal domination’ and favoritism with abstract rules and procedures, he argued, democratic movements made ‘politics more complex and less direct’ (Plotke., 1997 , p. 24). Increased complexity gave representation ‘a central positive role in democratic politics’, making it an outcome and ally of democracy rather than ‘an unfortunate compromise between an ideal of direct democracy and messy modern realities’ (Plotke, 1997 , p. 24).

That same year, Iris Marion Young also questioned the privilege accorded to ‘direct democracy’, arguing that directness betrays ideals of equality, mutuality, and accountability wherever face-to-face gatherings cede power to ‘arrogant loud mouths whom no one chose to represent them’ (Young, 1997 , p. 353). Her words affirmed Jane J. Mansbridge’s classic study, published twenty years earlier, which documented how town hall governance brings out deep-seated habits of deference to gender- and race-based hierarchies ( 1980 ). These works proved harbingers of what Nadia Urbinati termed the ‘democratic rediscovery of representation’ that took hold in the early 2000s and challenged the ‘standard model’ of representative politics (Urbinati, 2006 , p. 5; Castiglione & Warren, 2019 , p. 22).

The standard model focuses on elections. It conceives of democratic representation as a principal-agent relationship that is territorially based, located within constitutionally sanctioned institutions of political decision-making, and the source for ‘a simple means and measure of political equality’: the vote (Castiglione & Warren, 2019 , p. 21). Accordingly, representative institutions are democratic insofar as they ensure responsiveness to the ‘interests and opinions of the people constituted by territorial membership’ (Castiglione & Warren, 2019 , p. 21). Due to the proliferation of transnational and subnational practices of representation and the generation of economic and ecological externalities that confound territorial boundaries, twenty-first-century globalization created a ‘disjunction’ between model and practice that provided one catalyst for the turn toward representation in democratic theory (Urbinati & Warren, 2008 , p. 388).

New forms of political action gave scholars an even more powerful catalyst. Various experiments defied the traditional opposition between participatory and representative governance: ‘citizen juries, consensus conferences, planning cells’ (Brown, 2006 , p. 203); ‘accountable autonomy’ in community policing and school budgeting (Fung, 2004 , p. 6); sortition (Sintomer, 2011 , 2023 ). Scholars proposed new categories to conceptualize this activity—’informal’, ‘lay’, and ‘self-appointed’ representation (Montanaro, 2012 , 2017 ; Warren, 2008 ). Scholars also transformed the practice of democratic theory, plumbing historical instances where representative and democratic practices conjoined (Hayat) and working the intersection between normative and empirical research (Hawkesworth, 2003 ; Mansbridge, 2003 , 2009 ; Sabl, 2015 ).

The ‘representative turn’ stood out for its proponents’ ‘willingness to question the polarity of representation and democracy’ (Brito Vieira, 2017 , p. 5). They emphasized that representative functions can be fulfilled by a broad variety of non-electoral political actors including social movements, organizations, individual citizens, and influential media figures. They also maintained that political representation ‘does not simply allow the social to be translated into the political, but also facilitates the formation of political groups and identities’ (Urbinati, 2006 , p. 37; Brito Vieira and Runciman, 2008 ; Brito Vieira, 2009 ; Schwartz, 1998 ; Thomassen, 2019 ; Young, 1997 ). Above all, their work made it clear that Hanna Fenichel Pitkin’s classic definition of representation as the ‘making present in some sense of something which is nevertheless not present literally or in fact’ needed amending (Pitkin, 1967 , pp. 8, 9; emphasis original). These theorists, proponents of a ‘constructivist’ variant on the representative turn, emphasized making the represented and its interests over making them present (Disch, 2011 ; Hayward, 2009 ).

Michael Saward’s conceptualization of representation as claims-making provided an especially influential framework for analyzing this ‘performativity’ in both the speech act sense (as constitutive) and the theatrical sense (as performance) (Saward, 2014 , p. 725). He trained analysts’ attention on the work that would-be representatives do to ‘make representations’ of their constituents, by soliciting the ‘latter to recognize themselves’ in the portraits created by claims, policies, and other acts of representation (Saward, 2014 , p. 726; 2006 , 2010 ). He and others explored ‘representation’s aesthetic and cultural character’ (Saward, 2014 , p. 726) in the thought of Thomas Hobbes (Brito Vieira, 2009 ), in ‘enactments’ of race and gender through Congressional welfare reform (Hawkesworth, 2003 ), and in an array of staged public appearances (Salmon, 2010 ; Finlayson, 2021 ; Spary, 2021 ). Shirin Rai developed a ‘political performance framework’ that breaks political performances into their ‘component parts’ to identify the ‘materiality of performance’ and to analyze ‘why and how some performances mark a rupture in the everyday reproduction of social relations’ while others reproduce those relations (Rai, 2015 , pp. 1180, 1181). Laura Montanaro specified the category of ‘self-appointed’ representatives—charismatic individuals and organized advocacy groups who claim to speak for constituencies and are recognized as doing so even though they are neither elected nor appointed—and proposed normative criteria for assessing when they serve democracy and when they do not ( 2017 ).

This new work focused an urgent concern: ‘if representative politics is performative, how can we ensure that it is also democratic?’ (Thomassen in this Critical Exchange). By recognizing that political representation happens outside constitutionally sanctioned liberal democratic institutions and acknowledging its performativity, this work neutralized traditional election-based yardsticks for assessing its democratic legitimacy: authorization by and responsiveness to a geographically specified constituency.

It also provoked astute objections. Sophia Näsström observes an ambiguity about this work’s ‘diagnostic or normative’ aims ( 2011 , p. 502). Noting the pronounced asymmetries of voice in the non-electoral domain of global politics that favor the wealthy, she cautions that the emphasis on non-electoral representation may ‘serve as a warning of what may lie ahead, as a call for democratic theorists to rethink numerical equality beyond election’, or provide a ‘subtle’ means of acclimating people to the ‘idea that there may be acceptable forms of global representative government without democracy’ ( 2011 , p. 508). Jennifer Rubenstein similarly objects that the activities of global non-governmental organizations are not and do not claim to be acts of representation; they are exercises of power that should be analyzed as such rather than through a ‘representation lens’ ( 2007 , p. 208). Andrew Rehfeld ( 2017 ) pointedly observed that for all the new attention to representation, scholars failed to ask the simplest of questions: What is a representative and how does one come to be one?

Lisa Disch’s Making Constituencies emerges from the representative turn in democratic theory and is inspired by a specific problem: What are empirical researchers to make of the fact that they can affirm citizens’ capacity for preference-formation only at the cost of revealing their susceptibility to the self-seeking rhetoric of competing elites? This question originates from a reconsideration of early survey research that called traditional yardsticks of representative democracy into question long before democratic theorists made the turn. In 1964, Philip Converse famously debunked both responsiveness and accountability, arguing that voters offer little in the way of consistent beliefs or coherent ideologies for representatives to respond to and that they pay too little attention to politics to hold their representatives to account. Today, empirical scholars find that individuals in mass democracies do form political opinions, preferences, and identities but in response to political contexts rather than prior to them (see, for example, Carmines & Kuklinski, 1990 ; Lupia, 1992 , 1994 ; Druckman, 2001 ).

Making Constituencies emphasizes that empirical researchers offer distinct accounts of political learning processes that reach significantly different conclusions regarding the viability of representative democracy. One account holds that humans adapt their opinions and preferences to antagonistic group affiliations which they are psychologically disposed to form (Achen & Bartels, 2016 ; Iyengar et al., 2012 ). The other posts a political divide emerging in response to increasing polarization among political elites (Abrams & Fiorina, 2012 ; Levendusky, 2009 ). These accounts bear on the widely cited phenomenon of ‘sorting’, popularly known as the antagonistic division into partisan camps that pundits lament for rendering mass democracies increasingly ungovernable. The first account depoliticizes sorting by depicting it as a fact or state grounded in human psychology; the second treats it as a portrait of the political landscape—a representation. Rather than reflect a deep-seated partisan cleavage, talk of sorting, studies of sorting, and strategies designed to exploit it participate in constituting that antagonistic divide.

Despite the influence of the psychological account, empirical research frequently supports the political explanation. Recall the intractable partisan differences that were said to have influenced states’ pandemic-related regulations regarding masks and quarantine in the United States and people’s responses to those regulations. Sorting influenced how people understood and experienced the pandemic. Residents of blue [i.e. Democrat] states and/or counties blamed red-state [i.e. Republican] policy and the reckless actions of red-state residents for accelerating both the spread of the pandemic and the propagation of new variants.

Lessons from the Covid War: An Investigative Report ( 2023 ) re-examines this narrative, highlighting the ‘great untold story’ that it was ‘common’ during the first months of the pandemic ‘to find selfless cooperation, people sharing best practices and regularly supporting one another across state lines and all political persuasions’ ( 2023 , p. 150). Only as the pandemic wore on, and the 2020 presidential election approached, did policy and behavior with respect to masking, social-distancing, and—ultimately—vaccine mandates exhibit partisan antagonism. The authors emphasize:

…there is a common view that politics, a ‘[r]ed response’ and a ‘blue response’, were the main obstacle to protecting citizens, not competence and policy failures. We found, instead, that it was more the other way around. Incompetence and policy failures, including the failure of federal executive leadership, produced bad outcomes, flying blind, and resorting to blunt instruments. Those failures and tensions fed toxic politics that further divided the country in a crisis rather than bringing it together ( 2023 , p. 151).

Spotlighting this key paragraph, David Wallace-Wells observes that ‘the partisanship of our pandemic response was not a pre-existing condition…[but] was, at least partly, a result of that response’ ( 2023 ). Applied to the pandemic, the sorting narrative entrenched the condition that its subscribers lament—a country cleaved by antagonistic partisanship and unable to cooperate to achieve clear public goods.

I wrote Making Constituencies to better align our ideals of representative democracy with empirical findings about how it works in practice. This required displacing representative democracy from its (mythical) ground in the ‘bedrock’ of voter preferences—the constructivist turn (Disch, 2011 ). The intuition driving the book is that the constructivist turn has the potential to shore up rather than undermine mass democracy. If representative democracy is at its best when representatives of all kinds—elected officials, opinion-shapers, advocacy groups, and more—build creative and unlikely coalitions, perhaps the turn to constructivism inspires optimism about those agents’ ability to do just that. The generative and perceptive essays that follow offer a wealth of insight into where democratic theory is moving today, particularly in western democracies. They also persuade me that my book gave too little consideration to an important element of this vision: political judgment and the political conditions that foster and distort it in mass publics.

An excellent introduction to a great absent

The constructivist conception of political representation allows Disch to advance two very important arguments, which are the pillars of this excellent book: the vindication of critical realism, and its distinction from what I would call ‘simplistic’ realism. The former inspires a theoretical and practical attitude that is supportive of democracy, while the latter fosters a pessimistic and skeptical, if not overtly critical, attitude toward it. This dualism leads us directly to the topics that have divided scholars of democracy since time immemorial: the role of competence and, indeed, of the competent in political decision-making, and a negative assessment of the role of political parties. While Disch comprehensively covers the former, she leaves out the latter.

Political theorists are well acquainted with Disch’s work, which over the years has become a valuable contribution to the theory of representation as ‘claim-making’—a constructivist approach that corrects the formalist reading and connects representation with participation rather than only voting and institutions. The enormous implications of the constructivist turn have not yet been fully appreciated. They concern the understanding of politics, the role of conflict as constitutive of democratic politics and political freedom, and the inclination of democratic theory toward critical realism. Critical realism is a guide to decoding the factors that determine the formation of citizens’ reasons for their political choices, without falling into moralism and pedagogical paternalism, or alternatively justifying the status quo.

Representation entails the construction of constituencies. The latter give unity to the claims and problems that bring us into the political arena, shape the linguistic frame that conveys to others our reasons and goals—they represent us to our fellow citizens and the audience. Organizational strategies are essential to the making of the several roles and actors that comprise the collective work of representation, which is in all respects a process of participation through which citizens construct their political identities (movements and parties) and goals, and seek and acquire the power to determine the direction of the government of their society; in doing all of that citizens construct ties among each other and side for or against other constituencies. Representation is the name of a form of participation, whose Latin root means two things at once: taking sides and taking part.

Disch brilliantly sketches the process through which this conception of representation emerged: a long journey that began with Pitkin’s seminal 1967 book, which took representation out of the corner to which behaviorist and elitist theories of democracy had confined it, albeit at the cost of emphasizing its formalistic character. ‘Pitkin modified interest representation in several radical ways. She redefined democratic representation from an interpersonal relationship to an anonymous and impersonal’ or formal system process (p. 38). While elitist theory emphasized the individual-to-individual relationship (between the represented and the representatives) and the role of individual preferences and interests—a perspective that is still predominant in political science—Pitkin unpacked representation in relation to the form of the mandate and ascribed relevance to the moment of ‘acting for’. This choice opened the way to issues of advocacy and leadership, and fatally to those of manipulation and ideological constructions. However, although Pitkin did not make the representative claim bi-directional, and insisted on the formalist moment to detract from the plebiscitary or demagogic strategy, she nevertheless opened the way for the active role of citizens, both as respondents and as creators of leaders. Mansbridge refined that trajectory in relation to the deliberative system, proposing the idea of anticipatory representation linked to and in fact promoted by retrospective voting. Disch writes that this move pushed Mansbridge ‘into the constituency paradox’ and into the tension between ‘manipulation’ and ‘education’ that characterizes representative democracy. Disch’s critical work is situated within this ‘paradox’ but with a view to its solution, foregoing the need to identify ‘criteria for distinguishing between persuasion and manipulations’ (p. 45).

Based on the constructivist turn, Disch mounts an assault on contemporary realists, notably Christopher H. Achen, Larry M. Bartel and Jason Brennan, who in fact are anything but realists insofar as they judge citizens’ decisions (election results) on the basis of an idea of ‘competent’ decision-making that claims authority over citizens’ judgment and decision. But, Disch suggests, understanding how and why citizens voted for this or that candidate is not the same as staging a court of law to pass a verdict on them. Contemporary realists rely on a psychological approach in analyzing preferences and beliefs; this individualistic poll-based method leads them to conclude that ignorance is the structural flaw that elections generate, a flaw that can only be contained but never erased. The prescription is predictable: democracy is to be saved from itself by narrowing the role of suffrage in two ways: expanding the role of the competent (Achen and Bartel) or limiting the right to vote to those who pass an exam (Brennan).

These realists argue that the psychological need of individuals to bond with a group is like an instinctive force toward belonging, a kind of ‘primordialism’. It could be said that the more competent and intellectually sharp we are, the more we can reason apart from a group or an instinctive need to belong. The more rational we are, the more individualistic we are, and the more competent we are as citizens—a condition that is of the few, not the many. According to these realists, therefore, any grouping is a sign of ignorance and intellectual laziness. They draw on Gustave Le Bon and Gabriel Tarde, who wrote before democracy raised the fear of the (blind, irrational, emotional and reactive) masses that demagogues conquer. The distrust of contemporary realists mimics Robert Michels’ point that individual citizens need to associate to resolve their weakness, with the paradoxical consequence that association brings them into the arms of an oligarchy and makes them dependent on partisan views.

This simplistic realism is certainly not conducive to representative democracy. As Disch shows, it is the child of behaviorism and a negative conception of politics. It has a pessimistic attitude that is difficult to substantiate, even if very pronounced. Simplistic realism identifies citizenship with voting, and representation with recording individual preferences, and reads preferences as emotional reactions to a world that ordinary citizens have no means of knowing or are not interested in knowing. How can we address this ideological construct that claims to be an objective account of reality?

The most important contribution of Disch’s book lies in offering an answer to this question. Disch responds to realist critics, not by rejecting realism but by reinterpreting it. She argues, very persuasively, that realism is not identifiable with the empirical investigation of individual opinions that assigns a central role to researchers and assumes that citizens are simply reactive; an approach, as we have seen, that draws on crowd psychology. The interdisciplinary approach proposed by the critical realism Disch advocates assumes that political judgments (the reasons for citizens’ decisions) occur within a structural social context. Citizens develop their representative claims and, thus, their electoral choices within reflections on a range of considerations of governmental choices, social and economic conditions, and confrontations between different parts of society. Therefore, we should not blame the ignorance of citizens but the presumption of political scientists, who reduce political judgment to a matter of individual psychological reactions that discard ex ante social relations.

Disch masterfully sketches two realisms by opposing to the one exemplified by Achen, Bartel and Brennan a realism exemplified by Katherine J. Cramer and Suzanne Mettler. The latter is the child of a socio-economic structural analysis of the environment in which people form their beliefs, develop their reasons for making decisions, and eventually organize. For simplistic realism, politics has the defect of being a domain in which opinions are manipulated and preferences are simply wrong, because they often are irrational responses to a reality that eludes citizens. For critical realism, politics is the complex art of interpretation and action, a kind of knowledge that aims at ‘effectuality’ and is pragmatically action-oriented. To understand how citizens opine and decide, we must rely on various disciplines and interrogate the relationship between institutions, leaders, and constituencies.

Based on critical realism, Disch takes an important step outside the demarcation drawn by Mansbridge between manipulation and education, partisan politics and reasonable deliberation. Disch goes to the source of political scientists’ distrust of power. ‘To accept that political speech moves people as much or more than it educates them is to acknowledge the irreducible “ambiguities” of manipulation as a concept’ (p. 94), because indeed the result might be that any form of consensus-seeking persuasion is a form of manipulation. Yet if this were the case what would be the role of elections, party pluralism, and conflict to achieve consensus and govern?

The train of ideas that leads Disch to place the theory of democracy within critical realism is represented by some prominent figures: Elmer E. Schattschneider (for his theory of the contagiousness of conflict and the tension between vested interests and political interests), Robert Goodin (for his critique of the fear of manipulation as a fear of ‘competitive political rhetoric’), Claude Lefort (for bringing the theory of power back to its Machiavellian roots as ‘empty space’ and the choral and individual work of contestation in free (democratic) societies), and Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe (for bringing antagonism and hegemonic articulation of claims into representative politics). These are Disch’s coordinates for thinking democracy as a place of ‘plurality’ and struggle against hierarchy, thus rejecting plurality as made up of groups ‘out there’. Disch argues that, ‘Thinking democracy means thinking of it as plural in this precise sense’ (p. 140).

I fully share Disch’s views about critical realism and pluralism. Her argument is strong, persuasive, and very important. However, I think her position needs a complement to address two issues that are absent in her critical realism. The first issue pertains to ‘antagonism’ as ‘sharp conflict’ that ‘forces decisions on fundamental, often zero-sum issues’ (p. 139). The examples Disch proposes are foundational ‘yes’ or ‘no’ issues as the basic thresholds of democracy: issues of slavery or equal rights, for instance. This kind of ‘zero sum’ antagonism does not, however, seem to qualify ordinary party politics (not even in a two-party system). Not all politics can be antagonistic in this foundational sense if democratic conflict is to be distinguished from civil war. Does Disch distinguish between foundational antagonism and ordinary conflict politics?

This question brings me to the second issue, namely the role of political parties. It is odd that a book based on Schattschneider’s theory of politics and conflict does not have an entry in its index on ‘party’, ‘parties’, or ‘political parties’ and does not mention Schattschneider’s 1942 book Party Government , a pivotal anti-Schumpeterian work. Disch prefers to refer to movements, which at times she seems to use synonymously with parties, in order to make the case for representative constructivism. But of course, movements and parties are not the same. Unless we ascribe hegemonic or equivalence work to a single leader (a demagogue or a populist), we should consider the pivotal role of a collective organizer and organized body like the ‘political party’. This was the ‘collective Prince’ that Antonio Gramsci had in mind when he opposed the hegemonic agency of collective leadership against the politics of domination by individual leadership. Disch’s book is about ‘making constituencies’, which is a collective enterprise. Among the makers of this enterprise are parties, even if they are an object of contempt when they aim to be something more than machines for selecting and campaigning for candidates. Yet this is a Schumpeterian reading with which Disch’s critical realism cannot be content.

Nadia Urbinati

Making representation matter

We are experiencing a ‘representative turn’ in democratic theory. Despite important advances in understanding representation at the level of ‘high’ theory (Saward, 2010 , and Brito Vieira, 2017 ) and empirical political science (Guasti & Geissel, 2019 ), there have been very few attempts to theorize from the real world of political representation on the ground. Until now.

Lisa Disch’s Making Constituencies: Representation as Mobilization in Mass Democracy ( 2021 ) does just this, and very neatly. It is a short book full of ideas and crisp, convincing moves. Its mix of the theoretical and the empirical enables Disch to ground her theoretical arguments and helps the reader grasp the complexities of mobilizing her novel account of representation. Disch has a very important point to make, and she makes it well, engaging a remarkable variety of literatures and perspectives.

This is a book about representation in democracy or representative democracy. More specifically, the book is ‘a crusade against competence’ (p. 137) that ‘asks you to change the way you think about political representation’ (p. 1). What links representation and competence? As Disch argues, although politics is ultimately all about interests, conflict, and power, classic accounts of representation rest on an ‘interest-first’ model in which constituencies form around things they want and elected representatives respond to their demands. In other words, they assume that interests (and associated group affiliations) exist prior to the dynamics of representation, and that the job of the representative is about responding to expressed interests. This assumption informs how ordinary citizens assess their representatives: they judge them better or worse depending on how responsive they are to their preferences. This framing forms part of a larger history and discourse about representative democracy. As Disch shows in chapters 1 to 5 (especially in chapter 3), since the middle of the twentieth century this has led a swath of supposedly ‘realist’ thinkers especially, but not only, in American political science and journalism to become pessimistic about democracy.

On this kind of responsiveness model of representation, where the representative is assumed to be not much more than the citizens’ delegate, it is all too easy to explain the vagaries of democracy, and why some groups may even seem to vote for candidates opposed to furthering their own interests, via the idea of citizen incompetence. If the representative process is viewed in these simplistic terms, this not only underplays the role of the representative in shaping interests but also makes the unrealistic assumption that interests are fixed and prior to representation. Therefore, if citizens fail to elect those who are responsive to or act in their interests, they must in some way be incompetent: unable to identify their interests, easily manipulated, sticking to the groups with which they associate and affiliate, and not thinking independently about what is in their interest.

The next logical step for these more pessimistic thinkers is to argue that democracy itself is irredeemably flawed because it fails to enable citizens to identify their interests and then hold their representatives to account in terms of their responsiveness to these interests. Moreover, these mistakes are not confined to anti-democratic or ‘elite’ democratic theorists. They apply even to those who correctly point out that most elected representatives do not serve lower income (or even middle income) interests but elite interests held by those that fund or support their parties, campaigns, and lives. Because corruption is endemic, representative democracy, in this view, is inherently flawed (Vergara, 2022 )—unless, of course, this entire argumentative edifice is shown to rest on a delusion or a form of wishful thinking (Geuss, 2015 ) regarding the nature of representation and representative democracy.

Before discussing how Disch helps us escape this unhelpful way of understanding representation, it is worth noting that she also reveals a related problem, namely, the tendency of most normative political theory that has predominated in the west for sixty years to begin from the individual, despite the evident facts of our relational, embedded and interdependent lives. While there are ethically sound reasons for such individualism, Disch keeps groups front and center of political understanding. However, she disputes the idea that groups and group identities are fixed and pre-political. As Disch notes throughout her book, social scientists and citizens commonly think of politically significant group identities as determined by economic or other social interests and regard these groups as forming relatively spontaneously whenever these interests are at stake. This view takes discrete groups as basic constituents of social life and the main source of social conflict.

This view is also common amongst democratic theorists trained in social science. Pluralist and participatory theories of democracy are just two examples. They assume an existing (if sometimes dormant) group or constituency that simply requires mobilization (or rather targeting). They imply that groups form around shared interests to demand laws and policies that serve those interests. By contrast, Disch sees groups not as foundations or starting points of politics but as ‘constituency effects’—outcomes rather than origins of acts of political representation. Following Brubaker ( 2004 , p. 11), Disch thinks that race exemplifies this. She writes:

Brubaker recommends that we think about ‘groups’ as we think about race. We may accept the fact that ‘racial idioms, ideologies, narratives, categories and systems of classification… are real and consequential, especially when they are embedded in powerful organizations’, but this acceptance in no way obligates us to ‘posit the existence of races’. Just as ‘race’—when conceived as a real difference or natural basis for hierarchy—gives little analytical purchase on white supremacy, ‘group’ affords little analytical purchase on the phenomena of identity, loyalty, and mobilization that primordialists use it to explain. Groups hold together not by any essential property shared among their members, but by virtue of representations of divisions and difference that position them in the social field (pp. 21, 22).

For Disch, whether we are talking about groups mobilized around class, race, or gender, it is important to see that groups and group identities are always mobilized or fashioned. In her terms, ‘acts of political representation solicit groups and constitute interests’ (p. 19). Thus, Disch suggests a new term to capture or ‘register’ the power of representation to divide the social field: ‘constituency effects’ (p. 18). She catalogues a range of direct and indirect constituency effects to show how mobilization by representatives does not merely register social cleavages but forges them.

Faithful to Laclau and Mouffe’s account of radical democracy and plurality, Disch argues that plurality and conflict are vital for this idea of representation constituting groups (ch. 7). This brings us back to, what I take to be, the central triangulation of ideas at work here: interests, groups and related mechanisms of representation.

There is little doubt that the French Revolution marks a new beginning for our understanding of representation. Elsewhere I have defended the remarkable theoretical novelty of the Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès’s account of representation, especially in his ‘What is the Third Estate?’ (Hamilton, 2014 ). Disch reveals an additional component of his moves that links him to Laclau and Mouffe’s point about ‘representation cutting new divisions into the irreducible plurality of the social’. Sieyès aimed not just to enfranchise more of the French people but to radically reform the whole representative structure by changing how we conceive of representation. In his proposal to transform the Estates General into the National Assembly, Sieyès proposed a radical repudiation of the traditional notion of the binding mandate. In a context where existing institutions and theories were concerned with limiting representation by securing it to social interests, the Tennis Court Oath proclaimed a ‘revolution of the deputies against the condition of their election’: representatives, Sieyes argued and the Oath proclaimed, would no longer be mere delegates, which constrained them to express the explicitly stated wills and needs of their constituencies. They liberated themselves from this straitjacket to take up a dual role ‘as both sovereign representatives of the nation and makers of the social order’ (p. 127).

Claude Lefort ( 1988 ) claimed that this opened a new mode of political representation: by establishing the National Assembly, the revolutionaries threw off their shackles that bound representatives to reflect and reproduce a hierarchical order. They thus freed acts of representation—speeches, pamphlets, protests, bills—to rally popular political force in the face of existing conventions and towards the expansion of liberty. Sieyès not only aimed thus to persuade the most educated and upwardly mobile part of French society to disidentify with the privileged classes and align their sympathies downwards but opened up the possibility of new forms of representation beyond the restricted delegate model. This ‘rhetoric of social revolution’ opened a new cleavage, a new ordering, a new arena of conflict, involving the ‘identification and denunciation of a class enemy’. In John Dunn’s words, with reference to this period, ‘democracy was a reaction, above all, not to monarchy, let alone tyranny, but to another relatively concrete social category…—the nobility or aristocracy … Democrat was a label in and for political combat; and what that combat was directed against was aristocrats, or at the very least aristocracy’ (cited in Przeworski, 2009 , p. 283). Sieyès thus mounted an exemplary ‘representative claim’—in Laclau and Mouffe’s terminology, he launched a hegemonic bid. This new form of conflict between classes or groups brought about modern democracy as we know it.

This is what binds Sieyès to Laclau and Mouffe. As Lasse Thomassen has argued, ‘the hegemonic relation is essentially a relation of representation, where the representation is not the representation of an original presence but what brings about the represented—in short, a relation of articulation’ ( 2005 , p. 106, cited in Disch, p. 123). As is well known, Laclau and Mouffe do not use hegemony in its everyday sense of reducing politics to a struggle for domination between opposing political forces (Howarth, 2004 , p. 256, cited at p. 124). Rather, hegemony names the battle whereby political representatives (elected and unelected, formal and informal) ‘compete to activate new social divisions, provoke unaccustomed conflicts, and engage disaffected people in unexpected alliances—all with the aim of taking power’ (pp. 124, 125).

This is the crux for Laclau and Mouffe as well as for Disch. These processes involve antagonism not in the sense of disagreement, conflict, or unending hostility but as resistance in a social relationship that had previously reached equilibrium generated by a ‘confrontation between groups’ (Laclau, 1990 , p. 6, cited in Disch, p. 130). As Disch shows, Laclau and Mouffe describe a social field both unlike the mid-twentieth century pluralists’ complex terrain of competing social groups and the reduction to dichotomous class struggle wbich Marx hoped for (and the same can be said for the renewed plebian/elite divide espoused by contemporary left neo-Machiavellians). ‘Worker’, ‘woman’, ‘rural people, ‘Black’, ‘male’ or ‘female’: even as these categories seem to mark self-evidently different groups, Laclau and Mouffe argue that it is political division which has made them so, not demographic characteristics and certainly not essential properties. ‘Economic or historical logics do not create political actors… Representatives do more than stand for the interests of groups populated by “Black”, “White”, “rural”, etc., they constitute those groups by cutting divisions into the “irreducible plurality of the social”‘ (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985 , p. 139, cited in Disch, pp. 130, 131). This is then linked to a process of creating alliances that are not formed between pre-constituted groups whose interests and identities coincide but by what Laclau and Mouffe call ‘articulation’: the creation of a graft or link from one struggle to the next by asserting an ‘equivalence’ that alters what they identify and what they might fight for (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985 , pp. 23, 63, cited in Disch, p. 131). Disch lists how a wide range of feminisms have articulated with arguments around biological essentialism and ‘separate spheres’ at one extreme to Marxism at the other. Like Laclau and Mouffe, she lauds rights as having had an ‘irradiating’ effect on many struggle-movements in the twentieth century, from Black people’s struggles for civil and political rights, to feminist struggles for reproductive and economic rights, to struggles by gay, lesbian and transgender persons. Yet, like Laclau and Mouffe, she notes that rights have worked both ways, as a ‘subversive power’ which serves emancipatory and not-so-emancipatory ends alike. In fact, ‘the neoliberal Right seized that subversive power to as great or greater effect than had the radical democratic Left’ (p. 132).

Even if we grant Disch the deserts of her mobilization account of representation, it remains hard to see how processes of forging cleavages work in practice towards goals of freedom and equality that are so central to her and others’ accounts of the progressive role of democratic representation. She claims that ‘Political representatives in democratic societies—elected officials, social movements, opinion shapers, and advocates of all kinds—do not represent in the typical substitutionist, mimetic understanding of the term. They engage in articulation, the stitching together of collectivities or groups by way of a “metaphorical transposition” of one struggle to another’ (p. 132). Having made this claim, the example she then mobilizes—the long-term detrimental effects of the triumph of free-labor republicanism arguments over labor-movement antislavery positions in the struggle to abolish slavery in the United States (leaving us the legacy of equating freedom with contract and the ‘right to work’ and the resultant decimation of unions)—is a perfect example of this problem. Both discourses claimed to be freedom enhancing, but the one that was ultimately successful used the language of rights and has had deleterious effects on worker power. Given Disch’s view of the dynamics of representation, how can she be sure the outcomes she supports will be progressive? If, as she argues, ‘[p]references form and group identifications take shape in response to cues and appeals from political parties, from opinion-shapers, from advocacy organizations, for candidates and office-holders—and more’ (p. 137), how can she be certain that cleavage and conflict will lead to increased freedom rather than apathy, elite domination, and waning political agency for the least powerful? She admits that she cannot: ‘[t]o believe in the power and possibility of countermobilization among sporadically inattentive people—people like myself, who follow more cues than we give— that comes down to faith’ (p. 140).

I want to suggest that we can ask more of our representatives by sticking faithfully to a more performative account of representation and avoiding the strict claims-making structure proposed by Disch and other constructivists. There are two related problems with these kinds of constructivist accounts, which are inherent in how representation is conceived. First, everything seems, ultimately, to depend on representatives’ capacities (and interests) to mobilize us ordinary citizens in the right directions, or at least create enough conflict for us to identify alternatives, and then claim that it is the representatives themselves that take us in these new directions. Constructivist accounts that frame representation as dependent on claims-making seem with one hand to provide hope for the role and importance of our individual and group agency in democratic politics and then to take away this agency with the other. The representative (as opposed to the represented) ends up with most of the agency. Second, what of the older, important idea that representatives also represent the state? And what of the role of parties in the representative dynamic defended by Disch? It is striking that so little is said about the role of parties, given their presence and power in representative democracies. Can the state or political party be said to be a constituency in a way analogous to individuals and groups? This is not obviously the case, at least not without significant modification of the constructivists’ view. And what of those without voice or representation? Think of the Black residents in apartheid South Africa: the reason the fight took the form it did (primarily for civil and political rights) was due to the very fact that they had no voice or representation under apartheid. To think that change came about primarily because representatives created the cleavages and groups necessary for change is to miss the obvious brute fact that the de-, under-, and mis-represented groups could only be seen or heard (at least) initially by laying their bodies and lives on the line. That’s not to say that representation did not exist at all but that in certain circumstances it may not be enough.

Some may be tempted to think that the problem lies in a lack of normative guidance—that Disch’s view is too empirically grounded and insufficiently normative. I disagree. In fact, I think the empirical, real-world grounding is its major strength. The problem is not a lack of normative guidance but a lack of positive view of how to build into the account institutions that enable two seemingly irreconcilable things: more independence for representatives to create cleavages, groups, needs, interests and conflict; and more direct means for residents to judge and critique the performance and judgments of their representatives in terms of their needs and interests. This does not have to bring us back to pointing fingers at (in)competence amongst the ruled (or rulers) or to the idea that we are rooted within the various groups that make up our shared lives together.

Contrary to the framing offered by Disch, we can view representation through a constructivist lens and offer positive ideas and proposals about how to maintain and revivify institutions that enable the kind of political judgment necessary for effective representation, resistance, solidarity, inclusion and emancipation. We can constantly destabilize the institutional fabric of our democracies. To see how, we need to keep two goals front and center: residents and citizens must have control over their representatives who are determining their needs and interests and those of the state, alongside other formative institutions and practices; and they must be constrained sufficiently to give representatives the independence they need to make their own judgements regarding these needs and interests. Elsewhere (Hamilton, 2014 , pp. 133, 153, 192–205) I detail how these (often) partisan political institutions can be justified and sustained to the good of representative democracy. Here I can only note that the reason they can is that, like Disch’s account, with a little more emphasis on positive institution-building in line with an aesthetic view of representation, they help to break down the very common, yet unhelpful distinction in political thinking between ‘judgement’ and ‘opinion’.

If we escape both poles of thinking about representation—that representation is either about completely independent judgement or the direct transmission of opinion—either by means of Disch’s elegant constructivist account or an aesthetic view, it is possible to see that judgement becomes central at two levels of representation: acquiring and assessing the relevant factual information regarding existing needs and interests (which takes place via representatives and constituents); and the process of representing and evaluating needs, interest, and institutions (which leads to enhanced judgements amongst both rulers and ruled) (Hamilton, 2009 ). We thereby retain all the constructivist insights and keep representation material, grounded in the things that matter (involving representation): needs and interests.

Lawrence Hamilton

Representation and political strategy

Despite being embroiled in legal trouble, and despite his continuous lies, Donald Trump is leading the field of candidates for the Republican nomination for the 2024 presidential election. One commentator explained Trump’s success as follows:

Give Trump this: he doesn’t necessarily accept public opinion as it is but tries to shape it. Although there’d be widespread Republican doubts about the 2020 election no matter what he said, the belief that it was stolen wouldn’t be as deep and pervasive without his persistent (and deceptive) advocacy. He’s changed the landscape in his favor, and his opponents simply accept it at their peril. (Lowry, 2023 )

I would like to suggest that what this commentator proposes as an explanation for Trump’s success can be extended to all representative politics. When Trump claims to represent the real America, he does not mimic or reflect a real America out there but constructs it. He does not take public opinion as given, but shapes it. He makes a MAGA constituency by mobilizing interests and identities.

I take Making Constituencies to be making just this point: that representatives’ claims to represent their constituencies simultaneously construct—i.e. make—those constituencies. Moreover, (political) representation works insofar as it performatively constitutes what it claims to represent. Arguing this, Disch places herself in the so-called constructivist turn in the political theory of representation (Disch et al., 2019 ) by drawing on Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe ( 1985 ), among many others.

Populism is a discourse that claims to represent an entity that it simultaneously constitutes: the people. The people is an effect of populist discourse. Populism is the clearest expression of this performative aspect of representation and, for Laclau ( 2005 ), of politics in general: politics is about the construction of collective identities through their representation. Populism constructs a people, although the collective identity can have other names. The constructivist conception of representation shows, however, that it is not only populism that constructs identities and subjectivities: socialism constructs the working class as a revolutionary subject; liberalism constructs individual citizens and consumers as rights-bearers; and so on. In short, the performative aspect of populist representation is a general characteristic of representation.

Populism is the clearest expression of another general aspect of politics: antagonism. A populist discourse divides society in two, most obviously the people against the oligarchy. Populism divides, and it divides in such a way that the populist stands on the side of the (silent or not) majority. Populism is, therefore, a way to construct majorities.

Even though Disch draws on Laclau and Mouffe for her argument about the performative character of representation, she does not mention populism in her book. Trump is mentioned only three times (pp. 138, 140, 181 n. 42). And yet, my claim is that Trump allows us to learn something important, and general, about representation and politics. In one of the places Disch mentions Trump, she refers to him as an example of a ‘“Frankenstein” hybrid’ and a ‘monstrous hybrid’ (p. 140). She writes:

I wrote this book as a realist who has faith in mass democracy. My realism compels me to acknowledge the monstrous hybrids as real. They are not mangled versions of the American Dream but products of exclusions and entitlements that are built into its basic premises. My realism also counsels me that the democrat’s job is not to denounce any of democracy’s creatures but to take part in mobilizing counterforces against the ones I oppose. To believe in the power and possibility of countermobilization among sporadically inattentive people—people like myself, who follow more cues than we give— that comes down to faith. (p. 140)

This quote forcefully communicates the dilemma in which we find ourselves in the face of Trump and other monstrous hybrids: if representative politics is performative, (how) can we ensure that it is also democratic? Disch does not develop an answer in reference to populism, but I would like to do so here in order to cast more light on the dilemma.

Representation is mobilization and countermobilization. This is the terrain of politics. Politics is about constructing majorities, as Republicans from Nixon to Reagan did when they claimed to represent the silent majority. Those majorities may then be represented electorally and gradually become sedimented through policy. Thatcherism constructed a new majority at the end of the 1970s by mobilizing hardworking individuals, and Thatcherite policies then sedimented this majority, for instance by selling off council housing and thereby privatizing and individualizing how people thought about and ‘practiced’ housing (Hall, 1990 ). Strictly speaking, there is only countermobilization: we always find ourselves in a terrain where identities are already mobilized in some way. Trump’s claim about the stolen election amplifies existing claims about the election being stolen, but he is also mobilizing those claims in new ways. That terrain of already mobilized identities may be more or less dislocated and, therefore, open to countermobilization. Following Laclau and Mouffe, Disch refers to this as the ‘unfixity’ of identities that opens the social field as a plurality—and pluralization—of identities (pp. 9, 10; Laclau & Mouffe, 1985 , p. 85). To say that countermobilization always takes place in a (partly) mobilized terrain is also to say that countermobilization starts from this already (partly) mobilized terrain.

The danger for a progressive political project is to take that terrain as given rather than as something to be changed through mobilization. New Labour mobilized new constituencies from the mid-1990s onwards, and they did so in contrast to Thatcherism, for instance around sexuality and race. As such, they mobilized a new Britain (as Cool Britannia, for example). But New Labour also treated as given the Thatcherite majority around economic policy, so the new Britain was still a Britain of individuals who thought of social problems as individual problems. The realism of New Labour was to take certain things as given that were, in fact, the result of contingent hegemonic struggles. Disch proposes that we be realistic about how hegemonic struggles shape what we take to be real.

Countermobilization may consist in claiming to represent the ‘real’ interests of a constituency. We often find this in critiques of populists like Trump that they do not represent the real interests of working-class Americans. The point of the constructivist conception of representation is that real interests are real interests insofar as they have been represented and constructed as such. In other words, any representative claim may be a claim to represent something already there—the silent, moral majority, for instance—but we should treat that as a constative speech act that functions simultaneously as a performative speech act. This performative speech act only functions insofar as it appears as a constative claim to represent a state of affairs in the world. This does not mean that representations are not real. Insofar as they are successful, representations have real effects. For instance, the circulation of racist representations of Black Americans makes it more dangerous to be a young, Black male, because people act on those representations. I take this to be at the heart of Disch’s realism—that we shift focus from the individual representation to the institutions, practices, and discourses that generate certain kinds of representations: ‘critics and even friends of mass democracy … must focus on the systemic conditions for public-opinion and judgment-formation, rather than on the truth or falsehood of individual beliefs’ (p. 105).

The question, then, is what kinds of constituencies institutions mobilize. For instance, what constituencies are mobilized by different electoral systems? First-past-the-post systems may tend to mobilize identification with only two parties, sedimenting a two-party system over time. In such a system, what happens when competitive third-party candidates emerge? And what are the kinds of tweaks to such an electoral system that may break the polarization of constituencies into, for instance, ‘Democrat’ and ‘Republican’? Does Ranked Choice Voting, as practiced in Alaska, and in more and more places across the United States, mobilize less polarizing and more moderate constituencies (Jacobs, 2022 )? Does Ranked Choice Voting work against populists who divide society into two antagonistic camps? Likewise, does electoral fusion mobilize less or more polarized constituencies? Electoral fusion may help articulate a chain of equivalence among otherwise different parties—for instance, the Democratic Party and the Populist Party in the 1890s—thus fostering the division of the electoral field into two opposed camps. (While electoral fusion has largely disappeared from the American electoral system, one of the latest beneficiaries of electoral fusion was one Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential election when he appeared on the ballot for both the Republican Party and the far-right American Independent Party in California.) But it may equally be that electoral fusion (as well as Ranked Choice Voting) challenge voters’ self-identifications, thus pluralizing the social field and opening the possibility for new constituencies to be articulated.

The discussion as to how an electoral system mobilizes polarized constituencies is relevant in the context of Disch’s view that, ‘The greater threat comes from a picture that partisans use to rally their supporters: that of an America sorted into opposing camps so deeply rooted that they cannot be shaken loose and remade’ (p. 2). I take Disch to be identifying polarization as a threat in two respects. First, polarization is a threat to democracy insofar as opposing camps are taken as pre-given to politics, rather than the result of power relations sedimented in American political institutions. This much follows from her mobilization-conception of representation: we should focus on the source of polarized constituencies, and that source lies in the institutional make-up rather than in some primordial, pre-political constituencies.

Second, there is a critique here, and in the rest of her book, of the polarized shape of contemporary American politics. Disch is clear that politics involves conflict and exclusion: ‘To analyze constituency effects is to analyze the politics of conflict. It is to regard group mobilization as an index of the institutional biases that organize some groups into and others out of politics, rather than as the expression of a common interest or affinity’ (p. 33). This is particularly interesting in the context of Laclau and Mouffe, on whom Disch draws, and who theorize politics as inherently antagonistic. There are two things at stake here, in Disch and in Laclau and Mouffe. The first is how we understand political conflict: antagonism, cleavage, difference, division, line-drawing, polarization, and so on. The second is the status of antagonism as a form of politics that divides society in two opposing camps.

In Hegemony and Socialist Strategy , Laclau and Mouffe ( 1985 , pp. 122–127) use the term antagonism in two ways. First, they refer to the limit of objectivity or, in terms of the discussion here, the limits of representation. Second, they use it in the sense of a frontier between two opposed camps, a Schmittian friend/enemy relationship where the Other is the obstacle that prevents me from realizing my identity. It should be clear, however, that there is a tension between these two meanings of antagonism: if antagonism is the limit to representation, it cannot be represented as an enemy. This is why Laclau later conceptualized the limit of representation in terms of, first, dislocation and, later, heterogeneity (Thomassen, 2005 ). More important for my discussion here is how Laclau and Mouffe theorize antagonism as an antagonistic frontier. In Laclau, the antagonistic frontier becomes associated with populist discourse, which divides the social into two camps, and where each camp consists of a chain of equivalence among otherwise different constituencies. For instance, in Trump’s discourse, real Americans are opposed to a chain of equivalence of, among others, liberal elites, radical Democrats, weak Republicans, Muslims, and China. Mouffe’s agonistic democracy is organized around a we/they relationship, but importantly this relationship should not be one between enemies but between adversaries: ‘The challenge for democracy, therefore, is to establish the we/they distinction, which is constitutive of politics, in a way that is compatible with the recognition of pluralism’ (Mouffe, 2022 , p. 28).

I take Disch to be arguing something similar. If politics is about mobilizing constituencies, then democratic politics is about the struggle between different representations. In Laclau and Mouffe’s terms, democracy is a struggle for hegemony. However, it is important that this hegemonic struggle takes a democratic form. Disch points to a distinction Laclau and Mouffe draw between democratic and popular antagonisms in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (pp. 129, 130; Laclau & Mouffe, 1985 , pp. 131, 132, 137). Democratic antagonisms are associated with plurality, that is, with the unfixity of identities; popular antagonisms are those antagonisms which Laclau later refers to as populist antagonisms.

Disch concludes that in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy , ‘dichotomous division moves from being the very definition of antagonism to being strategically subordinate to democratic antagonism’ (p. 130). Disch is correct to identify this dichotomy between democratic and popular antagonisms and the priority of the former over the latter. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy was written as an attempt to theorize the implications for the Marxist view, that history tends towards a single antagonism between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, of the emergence of a plurality of antagonisms around gender, race, the environment, and so on. Laclau and Mouffe’s point was that the antagonism between workers and capitalists—that is, class—was only one possible antagonism among many. Moreover, insofar as the pluralization of antagonisms shows the unfixity, or contingency, of identities, there is no hegemonic struggle—democratic or popular—without this pluralization of antagonisms. Mouffe’s theory of agonistic democracy is a continuation of these concerns: it is an attempt to theorize how democratic hegemonic struggle is possible, and how we should think of the democratic institutions that facilitate these struggles. At the same time, Laclau’s ( 2005 ) theory of populism—and, to a lesser degree, Mouffe’s ( 2018 , 2022 ) recent work on Left populism—connects popular antagonisms to emancipatory rupture. Laclau is closer to the Marxist imaginary that connects emancipation to an antagonistic struggle between two opposed camps. Indeed, while Hegemony and Socialist Strategy challenges the idea that society can be defined in its totality by a single antagonism, Laclau’s On Populist Reason tends to take the populist antagonism between people and oligarchy as somehow primordial (Laclau, 2005 ).

However, I would add to Disch’s reading of Laclau and Mouffe that we do not need to accept their dichotomy between democratic and popular antagonisms, even on their own premises. I read Hegemony and Socialist Strategy as identifying two basic logics of difference and equivalence, respectively, (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985 , pp. 127–134). Those logics intersect and interrupt one another, and this is how we should understand the contingency (plurality, unfixity, non-closure) of the social. But if that is the case, then, as Laclau and Mouffe ( 1985 , p. 129) themselves point out, there are no purely democratic or popular struggles; difference is always inscribed (to some extent) in equivalence, and equivalence is always interrupted (to some extent) by difference. We then have a continuum with difference at one end and equivalence at the other, but with the caveat that we always find ourselves between the two ends of the continuum. This allows a finer differentiation of forms of political conflict, ranging from more to less antagonistic.