News from the Columbia Climate School

Six Tough Questions About Climate Change

Whenever the focus is on climate change, as it is right now at the Paris climate conference , tough questions are asked concerning the costs of cutting carbon emissions, the feasibility of transitioning to renewable energy, and whether it’s already too late to do anything about climate change. We posed these questions to Laura Segafredo , manager for the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project . The decarbonization project comprises energy research teams from 16 of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitting countries that are developing concrete strategies to reduce emissions in their countries. The Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project is an initiative of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network .

- Will the actions we take today be enough to forestall the direct impacts of climate change? Or is it too little too late?

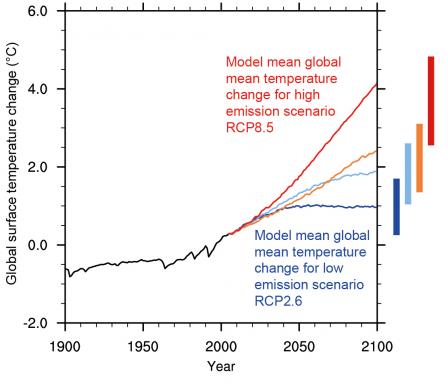

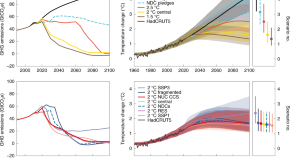

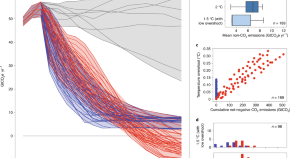

There is still time and room for limiting climate change within the 2˚C limit that scientists consider relatively safe, and that countries endorsed in Copenhagen and Cancun. But clearly the window is closing quickly. I think that the most important message is that we need to start really, really soon, putting the world on a trajectory of stabilizing and reducing emissions. The temperature change has a direct relationship with the cumulative amount of emissions that are in the atmosphere, so the more we keep emitting at the pace that we are emitting today, the more steeply we will have to go on a downward trajectory and the more expensive it will be.

Today we are already experiencing an average change in global temperature of .8˚. With the cumulative amount of emissions that we are going to emit into the atmosphere over the next years, we will easily reach 1.5˚ without even trying to change that trajectory.

Two degrees might still be doable, but it requires significant political will and fast action. And even 2˚ is a significant amount of warming for the planet, and will have consequences in terms of sea level rise, ecosystem changes, possible extinctions of species, displacements of people, diseases, agriculture productivity changes, health related effects and more. But if we can contain global warming within those 2˚, we can manage those effects. I think that’s really the message of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports—that’s why the 2˚ limit was chosen, in a sense. It’s a level of warming where we can manage the risks and the consequences. Anything beyond that would be much, much worse.

- Will taking action make our lives better or safer, or will it only make a difference to future generations?

It will make our lives better and safer for sure. For example, let’s think about what it means to replace a coal power plant with a cleaner form of energy like wind or solar. People that live around the coal power plant are going to have a lot less air pollution, which means less asthma for children, and less time wasted because of chronic or acute diseases. In developing countries, you’re talking about potentially millions of lives saved by replacing dirty fossil fuel based power generation with clean energy.

It will also have important consequences for agricultural productivity. There’s a big risk that with the concentration of carbon and other gases in the atmosphere, agricultural yields will be reduced, so preventing that means more food for everyone.

And then think about cities. If you didn’t have all that pollution from cars, we could live in cities that are less noisy, where the air’s much better, and have potentially better transportation. We could live in better buildings where appliances are more efficient. And investing in energy efficiency would basically leave more money in our pockets. So there are a lot of benefits that we can reap almost immediately, and that’s without even considering the biggest benefit—leaving a planet in decent condition for future generations.

- How will measures to cut carbon emissions affect my life in terms of cost?

To build a climate resilient economy, we need to incorporate the three pillars of energy system transformation that we focus on in all the deep decarbonization pathways. Number one is improving energy efficiency in every part of the economy—buildings, what we use inside buildings, appliances, industrial processes, cars…everything you can think of can perform the same service, but using less energy. What that means is that you will have a slight increase in the price in the form of a small investment up front, like insulating your windows or buying a more efficient car, but you will end up saving a lot more money over the life of the equipment in terms of decreased energy costs.

The second pillar is making electricity, the power sector, carbon-free by replacing dirty power generation with clean power sources. That’s clearly going to cost a little money, but those costs are coming down so quickly. In fact there are already a lot of clean technologies that are at cost parity with fossil fuels— for example, onshore wind is already as competitive as gas—and those costs are only coming down in the future. We can also expect that there are going to be newer technologies. But in any event, the fact that we’re going to use less power because of the first pillar should actually make it a wash in terms of cost.

The Australian deep decarbonization teams have estimated that even with the increased costs of cleaner cars, and more efficient equipment for the home, etc., when the power system transitions to where it’s zero carbon, you still have savings on your energy bills compared to the previous situation.

The third pillar that we think about are clean fuels, essentially zero-carbon fuels. So we either need to electrify everything— like cars and heating, once the power sector is free of carbon—or have low-carbon fuels to power things that cannot be electrified, such as airplanes or big trucks. But once you have efficiency, these types of equipment are also more efficient, and you should be spending less money on energy.

Saving money depends on the three pillars together, thinking about all this as a whole system.

- Given that renewable sources provide only a small percentage of our energy and that nuclear power is so expensive, what can we realistically do to get off fossil fuels as soon as possible?

There are a lot of studies that have been done for the U.S. and for Europe that show that it’s very realistic to think of a power sector that is almost entirely powered by renewables by 2050 or so. It’s actually feasible—and this considers all the issues with intermittency, dealing with the networks, and whatever else represents a technological barrier—that’s all included in these studies. There’s also the assumption that energy storage, like batteries, will be cheaper in the future.

That is the future, but 2050 is not that far away. 35 years for an energy transition is not a long time. It’s important that this transition start now with the right policy incentives in place. We need to make sure that cars are more efficient, that buildings are more efficient, that cities are built with more public transit so less fossil fuels are needed to transport people from one place to another.

I don’t want people to think that because we’re looking at 2050, that means that we can wait—in order to be almost carbon free by 2050, or close to that target, we need to act fast and start now.

- Will the remedies to climate change be worse than the disease? Will it drive more people into poverty with higher costs?

I actually think the opposite is true. If we just let climate go the way we are doing today by continuing business as usual, that will drive many people into poverty. There’s a clear relationship between climate change and changing weather patterns, so more significant and frequent extreme weather events, including droughts, will affect the livelihoods of a large portion of the world population. Once you have droughts or significant weather events like extreme precipitation, you tend to see displacements of people, which create conflict, and conflict creates disease.

I think Syria is a good example of the world that we might be going towards if we don’t do anything about climate change. Syria is experiencing a once-in-a-century drought, and there’s a significant amount of desertification going on in those areas, so you’re looking at more and more arid areas. That affects agriculture, so people have moved from the countryside to the cities and that has created a lot of pressure on the cities. The conflict in Syria is very much related to the drought, and the drought can be ascribed to climate change.

And consider the ramifications of the Syrian crisis: the refugee crisis in Europe, terrorism, security concerns and 7 million-plus people displaced. I think that that’s the world that we’re going towards. And in a world like that, when you have to worry about people being safe and alive, you certainly cannot guarantee wealth and better well-being, or education and health.

- So finally, doing what needs to be done to combat climate change all comes down to political will?

The majority of the American public now believe that climate change is real, that it’s human induced and that we should do something about it.

But there’s seems to be a disconnect between what these numbers seem to indicate and what the political discourse is like… I can’t understand it, yet it seems to be the situation.

I’m a little concerned because other more immediate concerns like terrorism and safety always come first. Because the effects of climate change are going to be felt a little further away, people think that we can always put it off. The Department of Defense, its top-level people, have made the connection between climate change and conflict over the next few decades. That’s why I would argue that Syria is actually a really good example to remind us that if we are experiencing security issues today, it’s also because of environmental problems. We cannot ignore them.

The reality is that we need to do something about climate change fast—we don’t have time to fight this over the next 20 years. We have to agree on this soon and move forward and not waste another 10 years debating.

Read the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project 2015 report . The full report will be released Dec. 2.

Laura Segafredo was a senior economist at the ClimateWorks Foundation, where she focused on best practice energy policies and their impact on emission trajectories. She was a lead author of the 2012 UNEP Emissions Gap Report and of the Green Growth in Practice Assessment Report. Before joining ClimateWorks, Segafredo was a research economist at Electricité de France in Paris.

She obtained her Ph.D. in energy studies and her BA in economics from the University of Padova (Italy), and her MSc in economics from the University of Toulouse (France).

Related Posts

Rising Wheat Prices and Unprecedented Demonstrations: Pakistani Protestors Demand Autonomy

In the Jersey Suburbs, a Search for Rocks To Help Fight Climate Change

Solar Geoengineering To Cool the Planet: Is It Worth the Risks?

Congratulations to our Columbia Climate School MA in Climate & Society Class of 2024! Learn about our May 10 Class Day celebration. #ColumbiaClimate2024

Many find low wages prohibits saving. Changing personal vehicles and heating systems costs. Will there be financial support for people on low wages?

The energy innovation and dividend bill has already been introduced in the house. It’s a carbon fee and dividend plan. The carbon fee rises every year and 100% of it goes back directly into the hands of the people by a check each month. This helps offset rising costs, especially for lower income folks.

81 cosponsors now Tell your rep in Congress to support this HR 763!

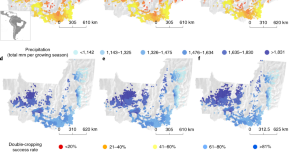

Results show that yields for all four crops grown at levels of carbon dioxide remaining at 2000 levels would experience severe declines in yield due to higher temperatures and drier conditions. But when grown at doubled carbon dioxide levels, all four crops fare better due to increased photosynthesis and crop water productivity, partially offsetting the impacts from those adverse climate changes. For wheat and soybean crops, in terms of yield the median negative impacts are fully compensated, and rice crops recoup up to 90 percent and maize up to 60 percent of their losses.

When is Russia, China, and Mexico going to work toward a better environment instead of the United States trying to do it all? They continue to pollute like they have for years. Who is going to stop the deforestation of the rain forest?

I’m curious if climate change has any effect on seismic activity. It seems with ice melting on the poles and increasing water dispersement and temp of that water, it might cause the plates to shift to compensate. Is there any evidence of this?

this isn’t because of doldrums or jet streams. the pattern keeps having the same action. we must save trees :3

How long do we have, before it’s too late?

Climate Change isn’t nearly as big of a deal as everyone makes it out to be. Meaning no disrespect to the author, but I really don’t see how this is something that we should be worrying about given that one human recycling their soda cans or getting their old phone refurbished rather than dumping it isn’t going to restore the polar ice caps or lower the temperature of the planet. And supposedly agriculture is the problem, but I point-blank refuse to give up my beef night, or bacon and eggs for breakfast on Saturdays. Also, nuclear power is supposed to be a solution, but the building of the power plants is going to add more greenhouse gases than the plant will take out. The whole planet needs a reality check. Earth isn’t going to explode because it’s slightly hotter than it used to be!

Thank you and I need in your help

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter

Thesis Helpers

Find the best tips and advice to improve your writing. Or, have a top expert write your paper.

Top 100 Climate Change Topics To Write About

Climate change issues have continued to increase over the years. That’s because human activities like fossil fuel usage, excavation, and greenhouse emissions continue to drastically change the climate negatively. For instance, burning fossil fuels continues to release greenhouse emissions and carbon dioxide in large quantities. And the lower atmosphere of the earth traps these gasses thereby affecting the global climate. To enhance their awareness of the impact of global warming, educators ask learners to write academic papers and essays on different climate change topics.

According to statistics, global warming affects the climate in different ways. However, the earth has experienced a general temperature increase of 0.85 degrees centigrade over the last 100 years. Such statistics show that this increase will eventually pass the acceptable thresholds in the next 10 years or less. And this will have dire consequences on human health and the global climate. As such, writing a paper about a topic on climate change is a great way to educate the masses.

However, some learners have difficulties choosing topics for their papers and essays on climate change. That’s because this is a relatively new subject. Nevertheless, students that are pursuing ecology, political, and biology studies are conversant with this subject. If struggling to decide what to write about, consider this list of topics related to climate change.

Climate Change Topics for Short Essays

Perhaps, your educator has asked you to write a short essay on climate change. Maybe you’re yet to decide what to write about because every topic you think about seems to have been written about. In that case, use this list of climate change topics for inspiration. You can write about one of these topics or develop it to make it more unique.

- How climate change is responsible for the disappearing rainforest

- The effects of global warming on air quality within the urban areas

- Global warming and greenhouse emissions- Possible health risks

- Is climate change responsible for irregular weather patterns?

- How has climate change affected the food chain?

- The negative effects of climate change on human wellbeing

- How global warming affects agriculture

- How climate change works

- Why is climate change dangerous to human health?

- How to minimize global warming effects on human health

- How global warming affects the healthcare

- Effects of climate change of life quality in rural and urban areas

- How warmer temperatures support allergy-related illnesses

- How climate change is a risk to life on earth

- How climate change and natural disasters correlate

- How climate change affects the population of the earth

- How climate change relates to global warming

- How global warming has caused extreme heating in most urban areas

- How wildfires relate to climate change

- How ocean acidification and climate change affect the world’s habitat

These climate change essay topics cover different aspects of human activities and their effects on the earth’s ecosystem. As such, writing a research paper or essay on any of these topics requires extensive research and analysis of information. That’s the only way you can come up with a solid paper that will impress the educator to award you the top grade.

Climate Change Issues that Make for Good Topics

Maybe you want to research issues that relate to climate change. Most people may have not considered such issues but they are worthy of climate change debate topics. In that case, consider these issues when choosing your climate topics for papers and essays.

- Climate change and threat to natural biodiversity are equally important

- Climate change in Miami and Saudi Arabia- How the effects compare

- Climate change as a human activity’s effect on the environment

- Preventing climate change by protecting forests

- Climate change in China- How the country has declined to head to the global call about saving Mother Nature

- Common causes of climate change

- Common effects of climate change

- The definition of climate change

- What is anthropogenic climate change

- Describe climate change

- What drives climate change?

- Renewable energy sources and climate change

- Human and economics induced climate change

- Climate change biology

- Climate change and business

- Science, Spin, and climate change

- Climate change- How global warming affects populations

- Climate change and social concepts

- Extreme weather and climate change- How they relate

- Global warming as a complex issue in climate change

These are great climate change topics for research papers and essays. However, writing about these topics requires extensive research. You should also be ready to spend energy and time finding relevant and latest sources of information before you write about these topics.

Interesting Climate Change Topics for Papers and Essays

Perhaps, you want to write an essay or paper about something interesting. In that case, consider this list of interesting climate change research paper topics.

- Climate change across the globe- What experts say

- Development, climate change, and disaster reduction

- Critical review- Climate change and agriculture

- Schools should include climate change as a subject in geography courses

- Consumption and climate change- How the wind blows in Indiana

- How the United Nations responds to climate change

- Snowpack and climate change

- How climate change threatens global security

- The effects of climate change on coastal areas’ tourism

- How climate change relates to Queensland Australia’s floods

- How climate change affects the tourism and hospitality industry

- Possible strategies for addressing the effects of climate change on urban areas

- How climate change affects indigenous people

- How to avoid the threats of climate change

- How climate change affects coral triangle turtles

- Climate change drivers in the Asian countries

- Economic discourse analysis methodology in climate change

- How climate change affects New Hampshire businesses

- How climate change affects the life of an individual

- The economic cost of the effects of climate change

These are fantastic climate change paper topics to explore. Nevertheless, you must be ready to research your topic extensively before you start writing your academic paper or essay.

Major Topics on Climate Change for Academic Writing

Perhaps, you’re looking for topics related to climate change that you write major papers about. In that case, you should consider these global climate change topics.

- Early science on climate change

- How the world can manage the effects of climate change

- Environmental issues relating to climate change

- Views comparison about the climate change problem

- Asset-based community development and climate change

- Experts’ evaluation of climate change

- How science affects climate change

- How climate change affects the ocean life

- Scotland’s vulnerability to climate change

- How energy conservation can solve the climate change problem

- How climate change affects the world economy

- International collaboration and climate change

- International relations view on climate change

- How transportation affects climate change

- Climate change and technology

- Climate change policies and human rights

- Climate change from an anthropological perspective

- Climate change as an international security issue

- Role of the United Nations in addressing climate change

- Climate change and pollution

This category has some of the best climate change thesis topics. That’s because most people will be interested in reading papers on such topics due to their global perspectives. Nevertheless, you should prepare to spend a significant amount of time researching and writing about any of these topics on climate change.

Climate Change Topics for Presentation

Perhaps, you want to write papers on topics related to climate change for presentation purposes. In that case, you need topics that most people can resonate with. Here is a list of topics about climate change that will interest most people.

- How can humans stop global warming in the next ten years

- Could humans have stopped global warming a decade ago?

- How has the environment changed over the years and how has this change caused global warming?

- How did the Obama administration try to limit climate change?

- What is the influence of chemical engineering on global warming?

- How is urbanization connected to climate change?

- Theories that explain why some nations ignore climate change

- How global warming affects the rising sea levels

- How anthropogenic and natural climate change differ

- How the war against terrorism differs from the war on climate change

- How atmospheric change influences global climate change

- Negative effects of global climate change on Minnesota

- The greenhouse effect and ozone depletion

- How greenhouse affects the earth’s environment

- How can individuals reduce the emissions of greenhouse gasses

- How climate change will affect humans in their lifetime

- What are the social, physical, and economic effects of climate change

- Problems and solutions to climate change on the Pacific Ocean

- How climate change relates to species’ extinction

- How the phenomenon of denying climate change affects animals

This list prepared by our research helpers has some of the best essay topics on climate change. Pick one of these ideas, research it, and then compose a winning paper.

Make PhD experience your own

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Explore your training options in 10 minutes Get Started

- Graduate Stories

- Partner Spotlights

- Bootcamp Prep

- Bootcamp Admissions

- University Bootcamps

- Coding Tools

- Software Engineering

- Web Development

- Data Science

- Tech Guides

- Tech Resources

- Career Advice

- Online Learning

- Internships

- Apprenticeships

- Tech Salaries

- Associate Degree

- Bachelor's Degree

- Master's Degree

- University Admissions

- Best Schools

- Certifications

- Bootcamp Financing

- Higher Ed Financing

- Scholarships

- Financial Aid

- Best Coding Bootcamps

- Best Online Bootcamps

- Best Web Design Bootcamps

- Best Data Science Bootcamps

- Best Technology Sales Bootcamps

- Best Data Analytics Bootcamps

- Best Cybersecurity Bootcamps

- Best Digital Marketing Bootcamps

- Los Angeles

- San Francisco

- Browse All Locations

- Digital Marketing

- Machine Learning

- See All Subjects

- Bootcamps 101

- Full-Stack Development

- Career Changes

- View all Career Discussions

- Mobile App Development

- Cybersecurity

- Product Management

- UX/UI Design

- What is a Coding Bootcamp?

- Are Coding Bootcamps Worth It?

- How to Choose a Coding Bootcamp

- Best Online Coding Bootcamps and Courses

- Best Free Bootcamps and Coding Training

- Coding Bootcamp vs. Community College

- Coding Bootcamp vs. Self-Learning

- Bootcamps vs. Certifications: Compared

- What Is a Coding Bootcamp Job Guarantee?

- How to Pay for Coding Bootcamp

- Ultimate Guide to Coding Bootcamp Loans

- Best Coding Bootcamp Scholarships and Grants

- Education Stipends for Coding Bootcamps

- Get Your Coding Bootcamp Sponsored by Your Employer

- GI Bill and Coding Bootcamps

- Tech Intevriews

- Our Enterprise Solution

- Connect With Us

- Publication

- Reskill America

- Partner With Us

- Resource Center

- Bachelor’s Degree

- Master’s Degree

The Top 10 Most Interesting Climate Change Research Topics

Finishing your environmental science degree may require you to write about climate change research topics. For example, students pursuing a career as environmental scientists may focus their research on environmental-climate sensitivity or those studying to become conservation scientists will focus on ways to improve the quality of natural resources.

Climate change research paper topics vary from anthropogenic climate to physical risks of abrupt climate change. Papers should focus on a specific climate change research question. Read on to learn more about examples of climate change research topics and questions.

Find your bootcamp match

What makes a strong climate change research topic.

A strong climate change research paper topic should be precise in order for others to understand your research. You must use research methods to find topics that discuss a concern about climate issues. Your broader topic should be of current importance and a well-defined discourse on climate change.

Tips for Choosing a Climate Change Research Topic

- Research what environmental scientists say. Environmental scientists study ecological problems. Their studies include the threat of climate change on environmental issues. Studies completed by these professionals are a good starting point.

- Use original research to review articles for sources. Starting with a general search is a good place to get ideas. However, as you begin to refine your search, use original research papers that have passed through the stage of peer review.

- Discover the current climatic conditions of the research area. The issue of climate change affects each area differently. Gather information on the current climate and historical climate conditions to help bolster your research.

- Consider current issues of climate change. You want your analyses on climate change to be current. Using historical data can help you delve deep into climate change effects. First, however, it needs to back up climate change risks.

- Research the climate model evaluation options. There are different approaches to climate change evaluation. Choosing the right climate model evaluation system will help solidify your research.

What’s the Difference Between a Research Topic and a Research Question?

A research topic is a broad area of study that can encompass several different issues. An example might be the key role of climate change in the United States. While this topic might make for a good paper, it is too broad and must be narrowed to be written effectively.

A research question narrows the topic down to one or two points. The question provides a framework from which to start building your paper. The answers to your research question create the substance of your paper as you report the findings.

How to Create Strong Climate Change Research Questions

To create a strong climate change research question, start settling on the broader topic. Once you decide on a topic, use your research skills and make notes about issues or debates that may make an interesting paper. Then, narrow your ideas down into a niche that you can address with theoretical or practical research.

Top 10 Climate Change Research Paper Topics

1. climate changes effect on agriculture.

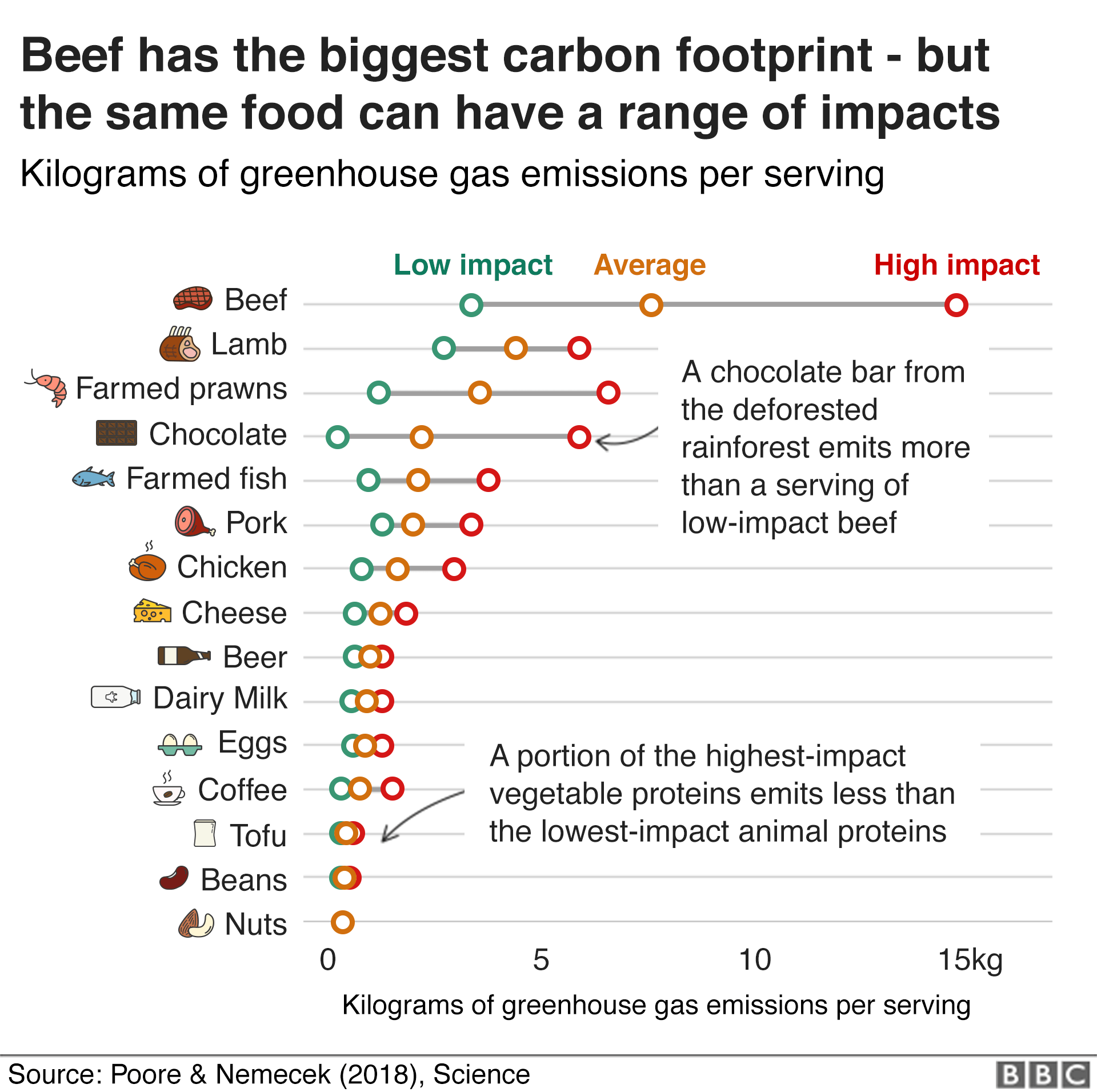

Climate change’s effect on agriculture is a topic that has been studied for years. The concern is the major role of climate as it affects the growth of crops, such as the grains that the United States cultivates and trades on the world market. According to the scientific journal Nature , one primary concern is how the high levels of carbon dioxide can affect overall crops .

2. Economic Impact of Climate Change

Climate can have a negative effect on both local and global economies. While the costs may vary greatly, even a slight change could cost the United States a loss in the Global Domestic Product (GDP). For example, rising sea levels may damage the fiber optic infrastructure the world relies on for trade and communication.

3. Solutions for Reducing the Effect of Future Climate Conditions

Solutions for reducing the effect of future climate conditions range from reducing the reliance on fossil fuels to reducing the number of children you have. Some of these solutions to climate change are radical ideas and may not be accepted by the general population.

4. Federal Government Climate Policy

The United States government’s climate policy is extensive. The climate policy is the federal government’s action for climate change and how it hopes to make an impact. It includes adopting the use of electric vehicles instead of gas-powered cars. It also includes the use of alternative energy systems such as wind energy.

5. Understanding of Climate Change

Understanding climate change is a broad climate change research topic. With this, you can introduce different research methods for tracking climate change and showing a focused effect on specific areas, such as the impact on water availability in certain geographic areas.

6. Carbon Emissions Impact of Climate Change

Carbon emissions are a major factor in climate change. Due to the greenhouse effect they cause, the world is seeing a higher number of devastating weather events. An increase in the number and intensity of tsunamis, hurricanes, and tornados are some of the results.

7. Evidence of Climate Change

There is ample evidence of climate change available, thanks to the scientific community. However, some of these implications of climate change are hotly contested by those with poor views about climate scientists. Proof of climate change includes satellite images, ice cores, and retreating glaciers.

8. Cause and Mitigation of Climate Change

The causes of climate change can be either human activities or natural causes. Greenhouse gas emissions are an example of how human activities can alter the world’s climate. However, natural causes such as volcanic and solar activity are also issues. Mitigation plans for these effects may include options for both causes.

9. Health Threats and Climate Change

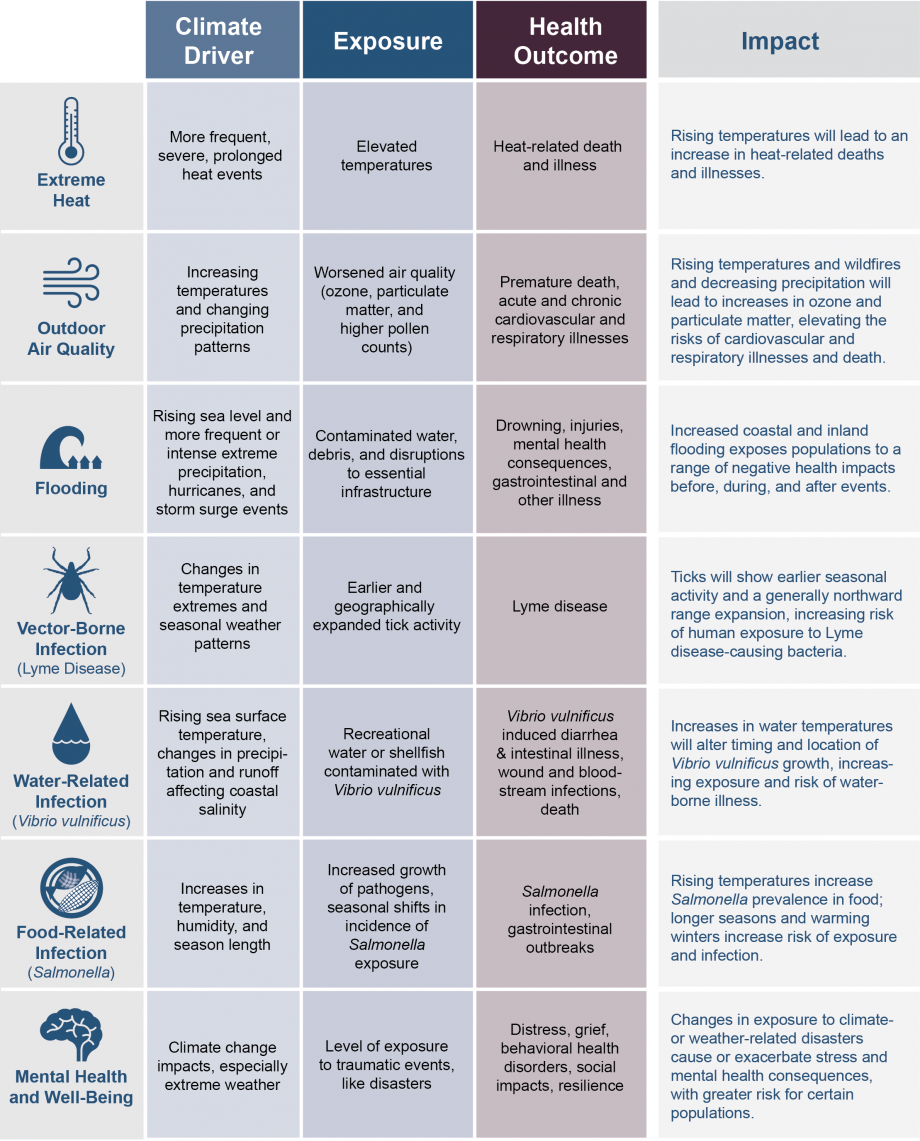

Climate change can have an adverse effect on human health. The impacts on health from climate change can include extreme heat, air pollution, and increasing allergies. The CDC warns these changes can cause respiratory threats, cardiovascular issues, and heat-related illnesses.

10. Industrial Pollution and the Effects of Climate Change

Just as car emissions can have an adverse effect on the climate, so can industrial pollution. It is one of the leading factors in greenhouse gas effects on average temperature. While the US has played a key role in curtailing industrial pollution, other countries need to follow suit to mitigate the negative impacts it causes.

Other Examples of Climate Change Research Topics & Questions

Climate change research topics.

- The challenge of climate change faced by the United States

- Climate change communication and social movements

- Global adaptation methods to climate change

- How climate change affects migration

- Capacity on climate change and the effect on biodiversity

Climate Change Research Questions

- What are some mitigation and adaptation to climate change options for farmers?

- How do alternative energy sources play a role in climate change?

- Do federal policies on climate change help reduce carbon emissions?

- What impacts of climate change affect the environment?

- Do climate change and social movements mean the end of travel?

Choosing the Right Climate Change Research Topic

Choosing the correct climate change research paper topic takes continuous research and refining. Your topic starts as a general overview of an area of climate change. Then, after extensive research, you can narrow it down to a specific question.

You need to ensure that your research is timely, however. For example, you don’t want to address the effects of climate change on natural resources from 15 or 20 years ago. Instead, you want to focus on views about climate change from resources within the last five years.

Climate Change Research Topics FAQ

A climate change research paper has five parts, beginning with introducing the problem and background before moving into a review of related sources. After reviewing, share methods and procedures, followed by data analysis . Finally, conclude with a summary and recommendations.

A thesis statement presents the topic of your paper to the reader. It also helps you as you begin to organize your paper, much like a mission statement. Therefore, your thesis statement may change during writing as you start to present your arguments.

According to the US Forest Service, climate change issues are related to topics regarding forest management, biodiversity, and species distribution. Climate change is a broad focus that affects many topics.

To write a research paper title, a good strategy is not to write the title right away. Instead, wait until the end after you finish everything else. Then use a short and to-the-point phrase that summarizes your document. Use keywords from the paper and avoid jargon.

About us: Career Karma is a platform designed to help job seekers find, research, and connect with job training programs to advance their careers. Learn about the CK publication .

What's Next?

Get matched with top bootcamps

Ask a question to our community, take our careers quiz.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

Frequently Asked Questions About Climate Change

Below are answers to some frequently asked questions about climate change. For information about evidence of climate change, the greenhouse effect, and the human role in climate change, please see EPA Climate Science .

On this page:

What is the difference between weather and climate?

What is climate change, what is the difference between global warming and climate change, what is the difference between climate change and climate variability, why has my town experienced record-breaking cold and snowfall if the climate is warming, is there scientific consensus that people are causing today’s climate change, do natural variations in climate contribute to today’s climate change, why be concerned about a degree or two change in the average global temperature, how does climate change affect people’s health, who is most at risk from the impacts of climate change, how can people reduce the risks of climate change, what are the benefits of taking action now.

Some of the following links exit the site.

"Weather" refers to the day-to-day state of the atmosphere such as the combination of temperature, humidity, rainfall, wind, and other factors. "Climate" describes the weather of a place averaged over a period of time, often 30 years. Think about it this way: climate is something that can be expected to happen in general, like a cold winter season, whereas weather is what a person might experience on any given day, like a snowstorm in January or a sunny day in July.

Climate change involves significant changes in average conditions—such as temperature, precipitation, wind patterns, and other aspects of climate—that occur over years, decades, centuries, or longer. Climate change involves longer-term trends, such as shifts toward warmer, wetter, or drier conditions. These trends can be caused by natural variability in climate over time, as well as human activities that add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere like burning fossil fuels for energy.

The terms "global warming" and "climate change" are sometimes used interchangeably, but global warming is just one of the ways in which climate is affected by rising concentrations of greenhouse gases. "Global warming" describes the recent rise in the global average temperature near the earth's surface, which is caused mostly by increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases (such as carbon dioxide and methane) in the atmosphere from human activities such as burning fossil fuels for energy.

Climate change occurs over a long period of time, typically over decades or longer. In contrast, climate variability includes changes that occur within shorter timeframes, such as a month, season, or year. Climate variability explains the natural variability within the system. For example, one unusually cold or wet year followed by an unusually warm or dry year would not be considered a sign of climate change.

Today’s Climate Change

Even though the planet is warming, some areas may be experiencing extra cold or snowy winters. These cold spells are due to variability in local weather patterns, which sometimes lead to colder-than-average seasons or even colder-than-average years at the local or regional level. In fact, a warmer climate traps more water vapor in the air, which may lead to extra snowy winters in some areas. As long as it is still cold enough to snow, a warming climate can lead to bigger snowstorms.

Yes. Climate scientists overwhelmingly agree that people are contributing significantly to today’s climate change, primarily by releasing excess greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from activities such as burning fossil fuels for energy, cultivating crops, raising livestock, and clearing forests. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Sixth Assessment Report , which represents the work of hundreds of leading experts in climate science, states that "it is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere, and biosphere have occurred.”

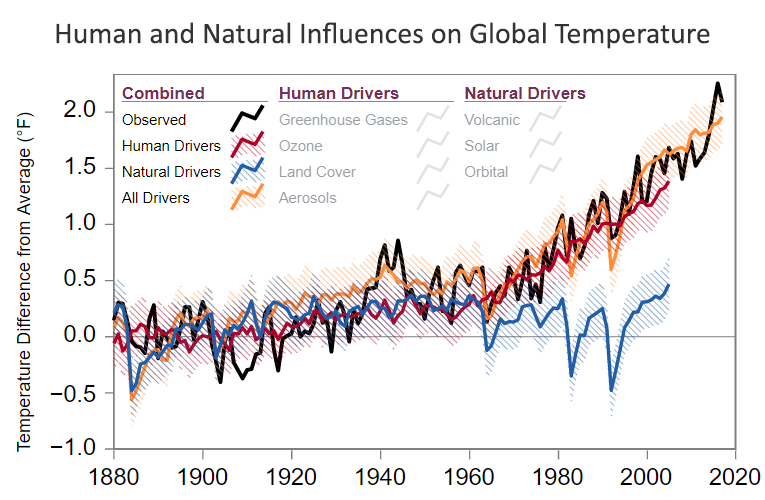

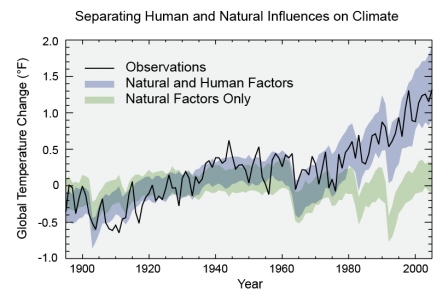

The 2018 National Climate Assessment , developed by the U.S. Global Change Research Program—which is composed of 13 federal scientific agencies—concluded that scientific evidence consistently points to human activities, rather than natural climate trends, as the “dominant cause” behind the rapid global temperature increase of 1.8°F from 1901 to 2016 (see Figure 1). Hundreds of independent and governmental scientific organizations have released similar statements, both in the United States and worldwide, including the World Meteorological Organization , the American Meteorological Society , and the American Geophysical Union .

The earth does go through natural cycles of warming and cooling caused by factors such as changes in the sun or volcanic activity. For example, there were times in the distant past when the earth was warmer than it is now. However, natural variations in climate do not explain today’s climate change. Most of the warming since 1950 has been caused by human emissions of greenhouse gases that come from a variety of activities, including burning fossil fuels.

A degree or two change in average global temperature might not sound like much to worry about, but relatively small changes in the earth’s average temperature can mean big changes in local and regional climate, creating risks to public health and safety , water resources , agriculture , infrastructure , and ecosystems . Among the many examples cited by the 2018 National Climate Assessment are an increase in heat waves and days with temperatures above 90°F; more extreme weather events such as storms, droughts, and floods; and a projected sea level rise of 1 to 4 feet by the end of this century, which could put certain areas of the country underwater.

Climate change poses many threats to people’s health and well-being. Among the health impacts cited by the 2018 National Climate Assessment are the following:

- Atmospheric warming has the potential to increase ground-level ozone in many regions, which can cause multiple health issues (e.g., bronchitis, emphysema, and asthma) and worsen lung function.

- Higher summer temperatures are linked to an increased risk of heat-related illnesses and death . Older adults, pregnant women, and children are at particular risk, as are people living in urban areas because of the additional heat associated with urban heat islands .

- Climate change is expected to expose more people to ticks that carry Lyme disease or other bacterial and viral agents, and to mosquitoes that transmit West Nile and other viruses.

- More frequent extreme weather events such as droughts , hurricanes , floods , and wildfires will not only put people’s lives at risk, but can also worsen underlying medical conditions, increase stress, and lead to adverse mental health effects.

- Rising temperatures and extreme weather have the potential to disrupt the availability, safety, and nutritional quality of food.

See EPA’s Climate Indicators website for more information about the effects of climate change in the United States.

Everyone will be affected by climate change, but some people may be more affected than others. Among the most vulnerable people are those in overburdened, underserved, and economically distressed communities. Three key factors influence a person’s vulnerability to the impacts of climate change:

- Exposure . Some people are more at risk simply because they are more exposed to climate change hazards where they live or work. For example, people who live on the coast can be more vulnerable to sea level rise, coastal storms, and flooding.

- Sensitivity . Some people are more sensitive to the impacts of climate change, such as children, pregnant women, and those with pre-existing medical conditions such as asthma.

- Adaptability . Older adults, those with disabilities, those with low income, and some indigenous people may have more difficulty than others in adapting to climate change hazards.

In addition, there is a wide range of other factors that influence people’s vulnerability. For example, people with less access to healthcare, adequate housing, and financial resources are less likely to rebound from climate disasters. People who are excluded from planning processes, experience racial and ethnic discrimination, or have language barriers are also more vulnerable to and less able to prepare for and avoid the risks of climate change.

Learn more about the connections between climate change and human health .

People can reduce the risks of climate change by making choices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and by preparing for the changes expected in the future. Decisions that people make today will shape the world for decades and even centuries to come. Communities can also prepare for the changes in the decades ahead by identifying and reducing their vulnerabilities and considering climate change risks in planning and development . Such actions can ensure that the most vulnerable populations —such as young children, older adults, and people living in poverty—are protected from the health and safety threats of climate change.

The longer people wait to act on climate change, the more damaging its effects will become on the planet and people’s health. If people fail to take action soon, more drastic and costly measures to prevent greenhouse gases from exceeding dangerous levels could be needed later. The most recent National Climate Assessment found that global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions could avoid tens of thousands of deaths per year in the United States by the end of the century, as well as billions of dollars in damages related to water shortages, wildfires, agricultural losses, flooding, and other impacts. There are many actions that people can take now to help reduce the risk of climate change while also improving the natural environment, community infrastructure and transportation systems, and overall health.

- Frequently Asked Questions

5 ways NOAA scientists are answering big questions about climate change

- April 20, 2021

- Download Cover Image

From warmer ocean temperatures to longer and more intense droughts and heat waves, climate change is affecting our entire planet. Scientists at NOAA have long worked to track, understand and predict how climate change is progressing and impacting ecosystems, communities and economies. This Earth Day, take a look at five ways scientists are studying this far-reaching global trend.

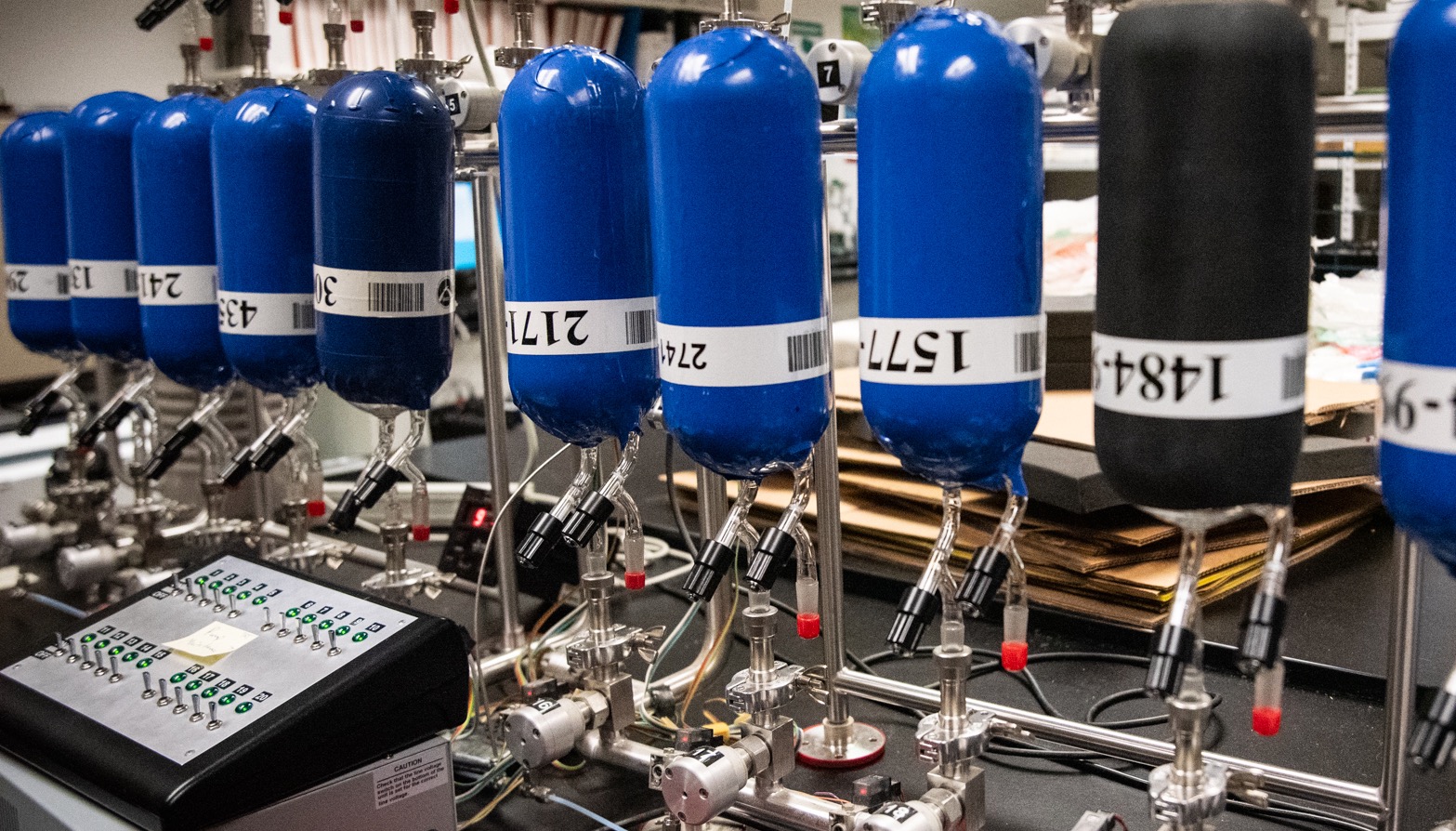

1. Tracking greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere

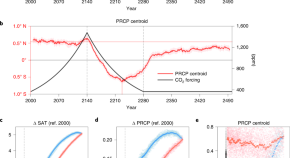

To understand climate change, scientists need an accurate, up-to-date record of how greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere have changed over time. Enter: NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratories’ Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network , which measures the three main long-term drivers of climate change: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, and nitrous oxide. Four remote atmospheric baseline observatories form the backbone of the monitoring system – the most well-known of which, located in Mauna Loa, Hawaii, is home to the longest record of direct measurements of CO2 in the atmosphere. This year, scientists used data from these observatories to confirm that average global CO2 levels had surged in 2020 to 412.5 parts per million – levels that are higher than at any time in the past 3.6 million years.

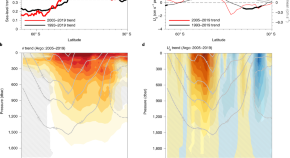

2. Understanding ocean warming

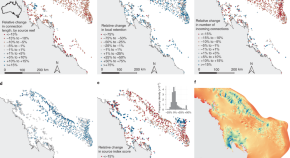

The ocean can absorb and store a lot of heat. In fact, more than 90 percent of the planet’s warming over the past 50 years has occurred in the ocean, making the buoys, floats and other ocean monitoring tools NOAA uses to keep tabs on ocean warming critical. Argo, for instance, is a network of about 4,000 autonomous floats that drift throughout the ocean, gathering critical data on salt content and temperature. Last year, data collected by Argo floats helped scientists determine that the area of ocean regions with long-term warming trends dwarfs that of regions with cooling trends. Deep Argo floats have also found that the coldest waters off of Antarctica are warming three times faster than they were in the 1990s. Tracking ocean warming helps scientists better predict sea level rise, gauge threats to coral reef ecosystems and important fisheries, and build knowledge on how a warmer ocean impacts our weather – including severe weather like hurricanes.

3. Exploring the link between climate change and hurricanes

Hurricanes draw their strength from warm ocean waters. So as the ocean continues to absorb heat, should we expect to see more intense hurricanes, tropical storms and typhoons?

Probably, according to recent research led by NOAA scientists . The research, which analyzed findings from over 90 peer-reviewed studies, found that warming of the surface ocean from human-caused climate change is likely fueling more powerful tropical cyclones. And as sea levels rise, the destructive power of tropical cyclones is amplified, as higher sea levels can result in more intense flooding. NOAA scientists have also concluded that climate change has been influencing the pattern of where tropical cyclones have been increasing or decreasing in occurrence. Researchers are still working to understand the link between climate and hurricanes – check out this page for the most up-to-date science.

4. Tracking warming in the Great Lakes

Like the ocean, freshwater is also impacted by Earth’s warming temperatures. In the Great Lakes, scientists who monitor winter ice cover say that, though ice cover tends to be variable from year to year, the data show a long-term trend of ice decline over the last several decades. Research has also shown that the Great Lakes’ deep waters aren’t immune to warming: As climate change has gradually delayed the onset of autumn in the Great Lakes region, the deep waters of Lake Michigan have started showing shorter winter seasons. Increases in the lakes’ water temperatures can have serious impacts, including disruptions in the food web that could affect fisheries and recreation, which are important parts of the regional economy.

5. Working towards climate resilience

From sunny day flooding creating hazards for coastal regions in Florida, to summer heat waves posing risks to communities without air conditioning in the Northeast, climate change creates a range of challenges and dangers for communities. NOAA is helping communities become more resilient to these changes. In Utqiaġvik, Alaska, for instance, NOAA Sea Grant and partners are working with the local community to better understand risks of flooding and shoreline erosion, helping them better prepare for storms. The NOAA Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments (RISA) program also funds research and engagement to help Americans prepare for climate change. For instance, the Northeast RISA team worked with New York City officials to map out where in the city extreme heat was having the most impact, so that the city could take action to protect at-risk residents. The U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit also makes it easy for people to learn more about climate-related risks and opportunities in their area, giving them the knowledge they need to make their communities more climate resilient.

To learn more NOAA’s work on climate change, visit climate.gov , and consider subscribing to the This Week on Climate.gov newsletter.

Those delicious smells may be impacting air quality

No sign of greenhouse gases increases slowing in 2023

First-of-its-kind experiment illuminates wildfires in unprecedented detail

Meet the women advancing NOAA’s exploration and stewardship of the ocean and Great Lakes

Popup call to action.

A prompt with more information on your call to action.

Researching Climate Change

Climate change research involves numerous disciplines of Earth system science as well as technology, engineering, and programming. Some major areas of climate change research include water, energy, ecosystems, air quality, solar physics, glaciology, human health, wildfires, and land use.

To have a complete picture of how the climate changes and how these changes affect the Earth, scientists make direct measurements of climate using weather instruments. They also look at proxy data that gives us clues about climate conditions from prehistoric times. And they use models of the Earth system to predict how the climate will change in the future.

Measurements of modern climate change

Because climate describes the weather conditions averaged over a long period of time (typically 30 years), much of the same information gathered about weather is used to research climate. Temperature is measured every day at thousands of locations around the world. This data is used to calculate average global temperatures . Changes in temperature patterns are a strong indicator of how much the climate is changing. Because we have thousands of temperature measurements, we know that record high temperatures are increasing across the globe, which is a sign that the climate is warming. Climatologists also look at changes in precipitation, the length and frequency of drought, as well as the number of days that rivers are at flood stage to understand how the climate is changing. Winds and other direct measures of climate contribute to climate change research as well.

This map shows the location of weather stations across the Earth. Continuous data from thousands of stations is important for climate change research.

Using proxy data to understand climate change in the past

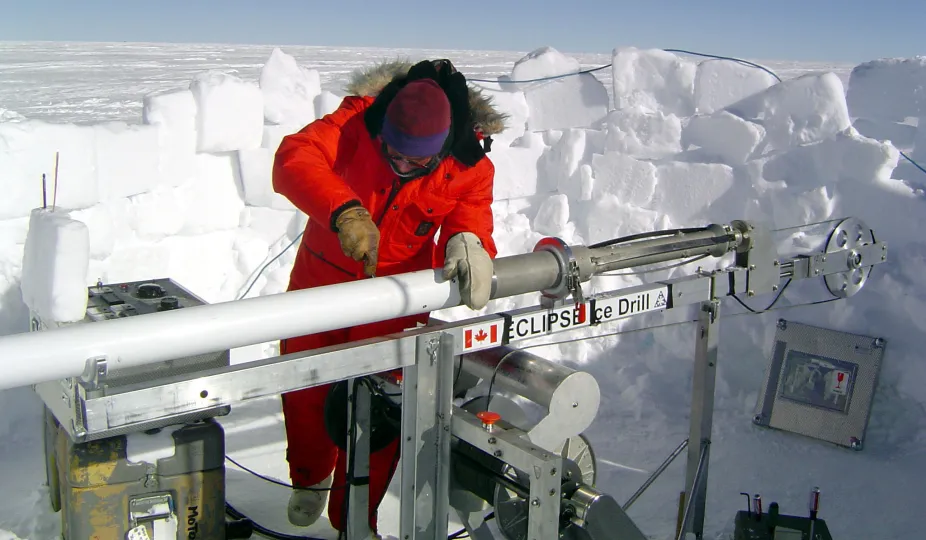

Throughout Earth's 4.6 billion years, the climate has changed drastically, including periods that were much colder and much warmer than the climate today. But how do we know about the climate from prehistoric times ? Researchers decipher clues within the Earth to help reconstruct past environments based on our understanding of environments today. Proxy data can take the form of fossils, sediment layers, tree rings , coral, and ice cores. These proxies contain evidence of past environments. For example, marine fossils and ocean seafloor sediment preserved in rock layers from around 80 million years ago (the Cretaceous Period) indicate that North America was mostly covered in water. The high sea levels were due to a much warmer climate when all of the polar ice sheets had melted. We also find fossil vegetation and pollen records indicating that forests covered the polar regions during this same time period. The existence of multiple types of proxy data from different locations, often from overlapping time periods, strengthens our understanding of past climates.

Ice core drilling in the Arctic provides proxy evidence of paleoclimate conditions.

National Snow and Ice Data Center

Using models to project future climate change

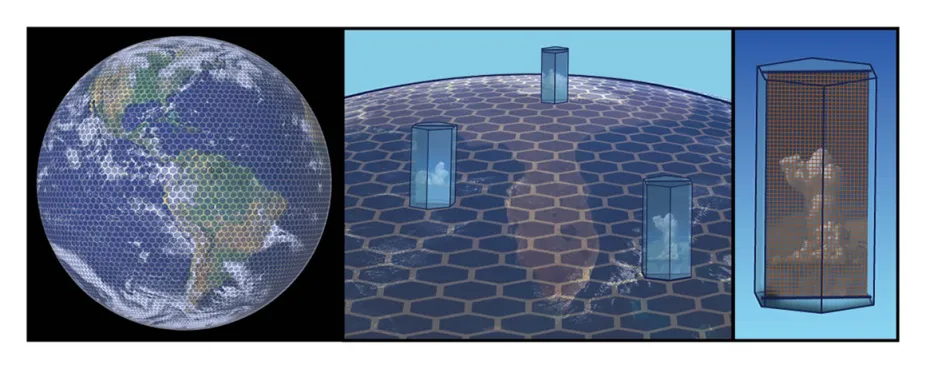

Scientists use models of the Earth to figure out how climate will likely change in the future. These models, which are simulations of Earth, include equations that describe everything from how the winds blow to how sea ice reflects sunlight and how forests take up carbon dioxide. In-depth knowledge of how each part of the Earth functions is needed to write the equations that represent each part within the model. Understanding climate change in both the present and the past helps to create computational models that can predict how the climate system might change in the future.

While scientists work hard to ensure that climate models are as accurate as possible, the models are unable to predict exactly how the climate will change in the future because some things are unknown, namely how much humans will change (or not change) behaviors that contribute to climate warming. Scientists run the models with different scenarios to account for a range of possibilities. For example, running the models to show how the climate will respond if we reduce fossil fuel emissions by different amounts can help us prepare for the many impacts that a changing climate has on the Earth.

Climate models keep track of how parameters change from place to place using a grid pattern on the Earth’s surface. The environmental conditions within each hexagon-shaped area are programmed into the model. More detailed models have smaller hexagons.

Studying the impacts of climate change

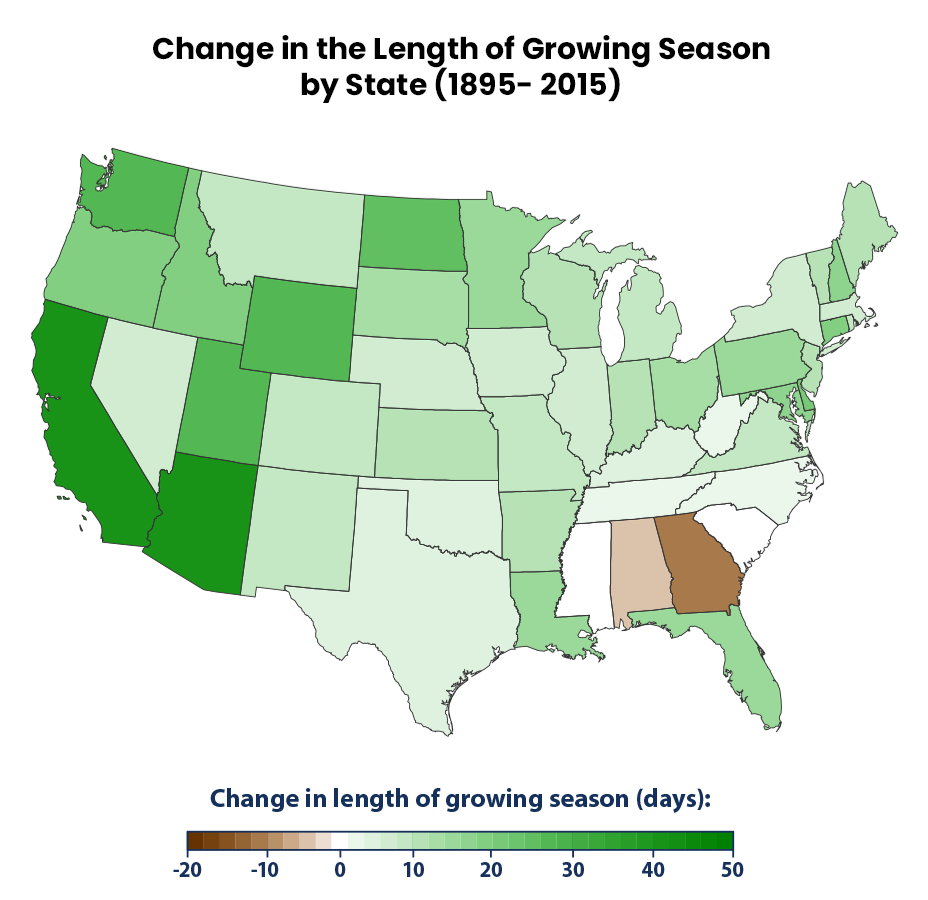

From monitoring changes in tropical coral reefs to changes in glacial ice, keeping track of how climate change is affecting the planet is important for adapting to the future. Scientists who monitor the environment report stronger and more frequent storms, changing weather patterns, a longer growing season in some locations, and changes in the distribution of plants and migratory animals. Monitoring how climate change is affecting our world can help identify new threats to human health as the ranges of insect-borne diseases change and as drought-prone regions expand.

Many different areas of research, from meteorology to oceanography, epidemiology to agriculture, and even fields such as sociology and economics, have a role to play in terms of researching both how the climate is changing and the impacts of climate change.

The average length of the growing season in the lower 48 states has increased by almost two weeks since the late 1800s, a result of the changing climate. Researchers study how this change in the growing season impacts humans and the Earth. Credit: EPA

© 2021 UCAR

- How Climate Works

- History of Climate Science Research

- Investigating Past Climates

- Climate Modeling

- Fast Computers and Complex Climate Models

- Visualizing Weather and Climate

- IPCC: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- From Dog Walking To Weather And Climate

- Satellite Signals from Space: Smart Science for Understanding Weather and Climate

- Mission, Facts and Figures

- Deans, Chairs and Staff

- Leadership Council

- Dean in the News

- Get Involved

- DEIB Mission

- Message from DEIB Associate Dean

- News and Media

- Reading Lists

- The Yale and Slavery Research Project

- Photo Gallery

- Winslow Medal

- Coat of Arms & Mace

- $50 Million Challenge

- For Pandemic Prevention and Global Health

- For Understanding the Health Impacts of Climate Change

- For Health Equity and Justice

- For Powering Health Solutions through Data Science

- For Future Leaders

- For Faculty Leaders

- For Transformational Efforts

- An abiding love for Yale turns into a lasting gift – in 15 minutes

- Endowed Professorship Created at Critical Time for Yale School of Public Health

- Brotherly encouragement spurs gift to support students

- Prestipino creates opportunities for YSPH students, now and later

- Alumna gives back to the school that “opened doors” in male-dominated field

- For Public Health, a Broad Mission and a Way to Amplify Impact

- Couple Endows Scholarship to Put Dreams in Reach for YSPH Students

- A Match Made at YSPH

- A HAPPY Meeting of Public Health and the Arts

- Generous Gift Bolsters Diversity & Inclusion

- Alumni Donations Aid Record Number of YSPH Students

- YSPH’s Rapid Response Fund Needs Donations – Rapidly

- Podiatric Medicine and Orthopedics as Public Health Prevention

- Investing in Future Public Health Leaders

- Support for Veterans and Midcareer Students

- Donor Eases Burden for Policy Students

- A Personal Inspiration for Support of Cancer Research

- Reducing the Burden of Student Debt

- Learning About Global Health Through Global Travel

- A Meeting in Dubai, and a Donation to the School

- Rapid Response Fund

- Planned Giving

- Testimonials

- Faculty, Postdoc Jobs

- For the Media

- Issues List

- PDF Issues for Download

- Editorial Style Guide

- Social Media

- Shared Humanity Podcast

- Health & Veritas Podcast

- Accreditation

- Faculty Directory by Name

- Career Achievement Awards

- Annual Research Awards

- Teaching Spotlights

- Biostatistics

- Chronic Disease Epidemiology

- Climate Change and Health Concentration

- Environmental Health Sciences

- Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases

- Global Health

- Health Policy and Management

- Maternal and Child Health Promotion Track

- Public Health Modeling Concentration

- Regulatory Affairs Track

- Social & Behavioral Sciences

- U.S. Health Justice Concentration

- Why Public Health at Yale

- Events and Contact

- What Does it Take to be a Successful YSPH Student?

- How to Apply and FAQs

- Incoming Student Gateway

- Traveling to Yale

- Meet Students and Alumni

- Past Internship Spotlights

- Student-run Organizations

- MS and PhD Student Leaders

- Staff Spotlights

- Life in New Haven

- Libraries at Yale

- The MPH Internship Experience

- Practicum Course Offerings

- Summer Funding and Fellowships

- Downs Fellowship Committee

- Stolwijk Fellowship

- Climate Change and Health

- Career Management Center

- What You Can Do with a Yale MPH

- MPH Career Outcomes

- MS Career Outcomes

- PhD Career Outcomes

- Employer Recruiting

- Tuition and Expenses

- External Funding and Scholarships

- External Fellowships for PhD Candidates

- Alumni Spotlights

- Bulldog Perks

- Stay Involved

- Board of Directors

- Emerging Majority Affairs Committee

- Award Nomination Form

- Board Nomination Form

- Alumni Engagement Plus

- Mentorship Program

- The Mentoring Process

- For Mentors

- For Students

- Recent Graduate Program

- Transcript and Verification Requests

- Applied Practice and Student Research

- Competencies and Career Paths

- Applied Practice and Internships

- Student Research

- Seminar and Events

- Competencies and Career paths

- Why the YSPH Executive MPH

- Message from the Program Director

- Two-year Hybrid MPH Schedule

- The Faculty

- Student Profiles

- Newsletter Articles

- Approved Electives

- Physicians Associates Program

- Joint Degrees with International Partners

- MS in Biostatistics Standard Pathway

- MS Implementation and Prevention Science Methods Pathway

- MS Data Sciences Pathway

- Internships and Student Research

- Competencies

- Degree Requirements - Quantitative Specialization

- Degree Requirements - Clinical Specialization

- Degree Requirements- PhD Biostatistics Standard Pathway

- Degree Requirements- PhD Biostatistics Implementation and Prevention Science Methods Pathway

- Meet PhD Students in Biostatistics

- Meet PhD Students in CDE

- Degree Requirements and Timeline

- Meet PhD Students in EHS

- Meet PhD Students in EMD

- Meet PhD Students in HPM

- Degree Requirements - PhD in Social and Behavioral Sciences

- Degree Requirements - PhD SBS Program Maternal and Child Health Promotion

- Meet PhD Students in SBS

- Differences between MPH and MS degrees

- Academic Calendar

- Translational Alcohol Research Program

- Molecular Virology/Epidemiology Training Program (MoVE-Kaz)

- For Public Health Practitioners and Workforce Development

- Course Description

- Instructors

- Registration

- Coursera Offerings

- Non-degree Students

- International Initiatives & Partnerships

- NIH-funded Summer Research Experience in Environmental Health (SREEH)

- Summer International Program in Environmental Health Sciences (SIPEHS)

- 2022 Student Awards

- APHA Annual Meeting & Expo

- National Public Health Week (NPHW)

- Leaders in Public Health

- YSPH Dean's Lectures

- The Role of Data in Public Health Equity & Innovation Conference

- Innovating for the Public Good

- Practice- and community-based research and initiatives

- Practice and community-based research and initiatives

- Activist in Residence Program

- Publications

- Health Care Systems and Policy

- Heart Disease and Stroke

- SalivaDirect™

- COVID Net- Emerging Infections Program

- Panels, Seminars and Workshops (Recordings)

- Public Health Modeling Unit Projects

- Rapid Response Fund Projects

- HIV-AIDS-TB

- The Lancet 2023 Series on Breastfeeding

- 'Omics

- News in Biostatistics

- Biostatistics Overview

- Seminars and Events

- Seminar Recordings

- Statistical Genetics/Genomics, Spatial Statistics and Modeling

- Causal Inference, Observational Studies and Implementation Science Methodology

- Health Informatics, Data Science and Reproducibility

- Clinical Trials and Outcomes

- Machine Learning and High Dimensional Data Analysis

- News in CDE

- Nutrition, Diabetes, Obesity

- Maternal and Child Health

- Outcomes Research

- Health Disparities

- Women's Health

- News in EHS

- EHS Seminar Recordings

- Climate change and energy impacts on health

- Developmental origins of health and disease

- Environmental justice and health disparities

- Enviromental related health outcomes

- Green chemistry solutions

- Novel approaches to assess environmental exposures and early markers of effect

- 1,4 Dioxane

- Reproducibility

- Tissue Imaging Mass Spectrometry

- Alcohol and Cancer

- Olive Oil and Health

- Lightning Talks

- News in EMD

- Antimicrobial Resistance

- Applied Public Health and Implementation Science

- Emerging Infections and Climate Change

- Global Health/Tropical Diseases

- HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Marginalized Population Health & Equity

- Pathogen Genomics, Diagnostics, and Molecular Epidemiology

- Vector-borne and Zoonotic Diseases

- Disease Areas

- EMD Research Day

- News in HPM

- Health Systems Reform

- Quality, Efficiency and Equity of Healthcare

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health

- Modeling: Policy, Operations and Disease

- Pharmaceuticals, Vaccines and Medical Devices

- Health and Wellbeing

- News in SBS

- Aging Health

- Community Engagement

- Health Equity

- Mental Health

- Reproductive Health

- Sexuality and Health

- Nutrition, Exercise

- Stigma Prevention

- Community Partners

- For Public Health Practitioners

- Reports and Publications

- Fellows Stipend Application

- Agency Application

- Past Fellows

- PHFP in the News

- Frequently Asked Questions

- International Activity

- Research Publications

- Grant Listings

- Modeling Analyses

- 3 Essential Questions Series

INFORMATION FOR

- Prospective Students

- Incoming Students

- myYSPH Members

3 Essential Questions: Climate Change and Health

- Climate Change

Kai Chen, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Health Sciences, studies the relationship between climate change, air pollution and human health. He applies multidisciplinary approaches in climate and air pollution sciences, exposure assessment and environmental epidemiology to better understand how climate change is affecting human health. Much of this work has been done in China, Europe and the United States.

Why is climate change regarded as the greatest public health challenge of the 21st century?

KC: This summer, we have witnessed deadly extreme weather events occurring across the United States, such as the record-breaking heat wave in the Pacific Northwest, the raging wildfires in the West, and the devastating hurricanes and flooding in the East. All of these extreme weather events are exacerbated by climate change. But the currently reported direct death toll during these events is only the tip of the iceberg. Extreme temperatures and weather events can adversely affect a comprehensive spectrum of diseases, leading to increased mortality and morbidity.

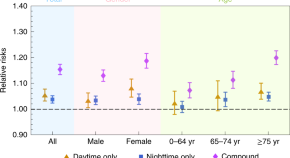

At Yale, our research at the Yale Center on Climate Change and Health (YCCCH) shows that heat can increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases such as heart attack and stroke, respiratory diseases, diabetes, unintentional injuries and mental disorders. Recent global burden-of-disease studies found that around 2 million to 5 million deaths per year can be attributable to extreme temperature globally.

Climate change can also indirectly impact our health through worsening water quality, air pollution, increased transmission of infectious diseases, and decreased crop yields and nutrients. For example, air pollution accounts for nearly seven million premature deaths per year. Our YCCCH’s recent research also shows that air pollution is linked to increased hospital admissions of cardiovascular, kidney and mental illness.

Why is the Paris Agreement goal to keep global warming well below 2° C so important to our health?

Recent global burden-of-disease studies found that around 2 million to 5 million deaths per year can be attributable to extreme temperature globally. Kai Chen

KC: Any increase in global warming will primarily adversely affect human health. Our research shows that heat-related morbidity and mortality are projected to increase at 1.5 °C of warming and increase further at 2 °C or 3 °C. Ground-level ozone, a potent air pollutant, will increase when global warming exceeds 2 °C, resulting in a higher ozone-related mortality burden. As the climate changes, the world’s population is also growing older. Population aging will substantially amplify the projected mortality burden of temperature and air pollution under a warming climate.

What is the legacy of COVID-19 in addressing climate change?

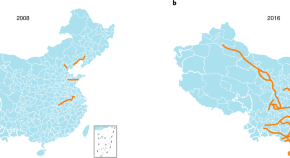

KC: One big legacy of the COVID-19 response is a leap forward to a sustainable and healthier world. During the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns have given us the opportunity to see clean and blue skies across the world. Our study finds that in China, the first nationwide lockdown in early 2020 sharply reduced the country’s often-severe air pollution and brought substantial human health benefits in non-COVID-19 deaths. This dramatic change has shown us a glimpse of what a healthier world with strong clean air policies could be. But air pollution reduction and its associated health benefits during COVID-19 lockdowns are temporary. Moving forward, a more sustainable and healthier society will require increased investment in clean and renewable energy, low-carbon infrastructure, active transportation and climate-friendly lifestyles.

At the Yale Center on Climate Change and Health, our Climate, Health and Environment Nexus Lab aims to apply multidisciplinary approaches to produce policy-relevant knowledge that can be used to advance climate change mitigation and adaptation in a manner that promotes health and protects vulnerable populations.

3 Essential Questions is a recurring feature that explores vital topics in public health. Read earlier versions of 3 Essential Questions on cancer and antibiotic resistance .

MEDIA CONTACT: Michael Greenwood at [email protected]

Featured in this article

- Kai Chen, PhD Assistant Professor of Epidemiology (Environmental Health); Director of Research, Climate Change and Health; Deputy Faculty Director, Climate Change and Health; Affiliated Faculty, Yale Institute for Global Health

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- 9 questions about climate change you were too embarrassed to ask

Basic answers to basic questions about global warming and the future climate.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: 9 questions about climate change you were too embarrassed to ask

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/55048475/North_America_from_low_orbiting_satellite_Suomi_NPP.0.jpg)

This explainer was updated by Umair Irfan in December 2018 and draws heavily from a card stack written by Brad Plumer in 2015. Brian Resnick contributed the section on the Paris climate accord in 2017.

There’s a vast and growing gap between the urgency to fight climate change and the policies needed to combat it.

In 2018, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that it is possible to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius this century, but the world may have as little as 12 years left to act. The US government’s National Climate Assessment , with input from NASA, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Pentagon, also reported that the consequences of climate change are already here, ranging from nuisance flooding to the spread of mosquito-borne viruses into what were once colder climates. Left unchecked, warming will cost the US economy hundreds of billions of dollars.

However, these facts have failed to register with the Trump administration, which is actively pushing policies that will increase the emissions of heat-trapping gases.

Ever since he took office, President Donald Trump has rejected or undermined President Barack Obama’s signature climate achievements: the Paris climate agreement; the Clean Power Plan , the main domestic policy for limiting greenhouse gas emissions; and fuel economy standards , which target transportation, the largest US source of greenhouse gases.

At the same time, the Trump administration has aggressively boosted fossil fuels: opening unprecedented swaths of public lands to mining and drilling , attempting to bail out foundering coal power plants , and promoting hydrocarbon exploitation at climate change conferences .

Trump has also appointed climate change skeptics to key positions. Quietly, officials at these and other science agencies have been removing the words “climate change” from government websites and press releases.

Yet the evidence for humanity’s role in changing the climate continues to mount, and its consequences are increasingly difficult to ignore. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations now top 408 parts per million, a threshold the planet hasn’t seen in millions of years . Greenhouse gas emissions reached a record high in 2018. Disasters worsened by climate change have taken hundreds of lives, destroyed thousands of homes, and cost billions of dollars.

The big questions now are how these ongoing changes in the climate will reverberate throughout the rest of the world, and what we should do about them. The answers bridge decades of research across geology, economics, and social science, which have been confounded by uncertainty and obscured by jargon. That’s why it can be a bit daunting to join the discussion for the first time, or to revisit the conversation after a hiatus.

To help, we’ve provided answers to some fundamental questions about climate change you may have been afraid to ask.

1) What is global warming?

In short: The world is getting hotter, and humans are responsible.

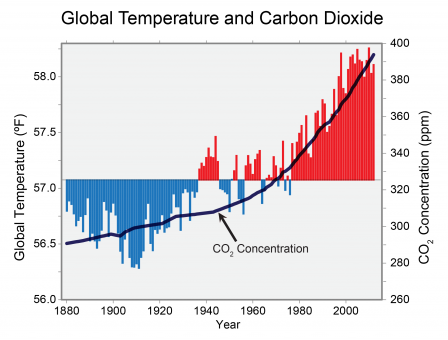

Yes, the planet’s temperature has changed before, but it’s the rise in average temperature of the Earth's climate system since the late 19th century, the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, that’s important here. Temperatures over land and ocean have gone up 0.8° to 1° Celsius (1.4° to 1.8° Fahrenheit), on average, in that span:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10346257/Screen_Shot_2018_03_05_at_10.29.11_AM.png)

Many people use the term “climate change” to describe this rise in temperatures and the associated effects on the Earth's climate. (The shift from the term “global warming” to “climate change” was also part of a deliberate messaging effort by a Republican pollster to undermine support for environmental regulations.)

Like detectives solving a murder, climate scientists have found humanity’s fingerprints all over the planet’s warming, with the overwhelming majority of the evidence pointing to the extra greenhouse gases humans have put into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide trap heat at the Earth’s surface, preventing that heat from escaping back out into space too quickly. When we burn coal, natural gas, or oil for energy, or when we cut down forests that usually soak up greenhouse gases, we add even more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, so the planet warms up.

Global warming also refers to what scientists think will happen in the future if humans keep adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

Though there is a steady stream of new studies on climate change, one of the most robust aggregations of the science remains the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s fifth assessment report from 2013. The IPCC is convened by the United Nations, and the report draws on more than 800 expert authors. It projects that temperatures could rise at least 2°C (3.6°F) by the end of the century under many plausible scenarios — and possibly 4°C or more. A more recent study by scientists in the United Kingdom found a narrower range of expected temperatures if atmospheric carbon dioxide doubled, rising between 2.2°C and 3.4°C.

Many experts consider 2°C of warming to be unacceptably high , increasing the risk of deadly heat waves, droughts, flooding, and extinctions. Rising temperatures will drive up global sea levels as the world’s glaciers and ice sheets melt. Further global warming could affect everything from our ability to grow food to the spread of disease.